Abstract

Climate change increases not only the vulnerability of cultural resources, but also the cultural values that are deeply embedded in cultural resources and landscapes. As such, heritage managers are faced with imminent preservation challenges that necessitate the consideration of place meanings during adaptation planning. This study explores how stakeholders perceive the vulnerability of the tangible aspects of cultural heritage, and how climate change impacts and adaptation strategies may alter the meanings and values that are held within those resources. We conducted semi-structured interviews with individuals with known connections to the historic buildings located within cultural landscapes on the barrier islands of Cape Lookout National Seashore in the United States (US). Our findings revealed that community members hold deep place connections, and that their cultural resource values are heavily tied to the concepts of place attachment (place identity and place dependence). Interviews revealed a general acceptance of the inevitability of climate impacts and a transition of heritage meanings from tangible resources to intangible values. Our findings suggest that in the context of climate change, it is important to consider place meanings alongside physical considerations for the planning and management of vulnerable cultural resources, affirming the need to involve community members and their intangible values into the adaptive planning for cultural resources.

1. Introduction

The concepts of landscapes, space, and place are highly convoluted, yet exceedingly important in regard to how people connect to their environments. People engage with landscapes in a variety of ways, creating connections between people and places or what is often termed “a sense of place” [1,2]. In addition to being socially constructed, “they are politicized, culturally relative, and historically specific” [3], (p. 22). Humans’ untidy and often contradictory encounters with landscapes are an integral part of forming cultural meanings, forever entangling people and their places. In other words, landscapes are culture, landscapes form culture, and culture is embedded in landscapes [2]. Yet, changes to cultural landscapes and the tangible resources within them can alter the intangible values associated with these places, and climate change poses unique threats to cultural landscapes, cultural resources, and associated meanings [4,5].

According to Poulter et al. [6], coastal areas are facing the most imminent and some of the most devastating effects of climate change resulting from impending sea level rise and increased storm intensity and frequency. In fact, it is estimated that more than $20 billion (USD) worth of coastal assets (i.e., infrastructure and cultural resources) located in coastal units of the United States (US) National Park Service (NPS) are at risk from climate change by 2100 [7]. Without prompt and decisive action, many of these resources—and the meanings associated with them—are in profound danger of suffering irreparable damage. However, a recent systematic literature review revealed that research specific to managing cultural resources under changing climate conditions is nascent [8].

As cultural resources—particularly in coastal environments—are vulnerable to climate change impacts (e.g., storm-related flooding and erosion, sea level rise [7,9]), researchers have specifically called for studies to document the relationships between place meanings and climate change impacts and adaptation [10,11]. A small but growing body of research is answering this call by examining the influences of place meanings on climate change beliefs [12] and nature-based recreation and tourism demand [13], as well as studying the influence of climate change impacts on place meanings and community well-being [14], and the extent to which locals and visitors are willing to support or contribute to adaptation planning efforts [15,16]. Yet, there is a gap in the literature that is related to the ways in which climate change impacts cultural resources, as well as the ways that any changes that occur from adaptation strategies to avoid or lesson climate change impacts, will alter people’s connections to those resources [17].

The purpose of this research is to explore how stakeholders perceive the vulnerability of the tangible aspects of their cultural heritage and how climate change and adaptation strategies may alter their connections within that place. We examine these place connections at Cape Lookout National Seashore, an NPS site located on the coast of North Carolina that includes two designated historic districts. Using a thematic analysis of in-depth interviews with a set of former residents and the descendants of former residents, as well as prior lessees and other individuals with known ties to the districts, this study documents the complexity of place meanings in dynamic environments, highlighting the inevitability of losses to climate change impacts and the transference of cultural heritage to intangible values when the loss—climate change-related or otherwise—of tangible resources occurs. Furthermore, the study provides heritage managers with a better understanding of the consequences of any attempts to enhance the persistence of tangible resources that are located within cultural landscapes.

2. Literature Review

Concepts regarding place meanings, place attachment, and sense of place have been garnering scientific attention in multiple fields for several decades [18]. As increasing environmental problems “threaten the existence of and our connections to places important to us” [19] (p. 1), our awareness of the need to examine bonds between places and people intensifies. When socially constructed environments and landscapes are subjected to change from outside forces (e.g., climate change), the meanings and cultural values that are ascribed to those places by their communities also become vulnerable to these forces [20]. In this section, we first review the literature on place connections generally, and then on place connections impacts from climate change to cultural heritage specifically.

2.1. Place Connections

Within the fields of conservation and natural resource management, the phrase “sense of place” has been used interchangeably with the construct “place attachment”; however, the literature on sense of place has evolved, and is now being even more broadly referred to as “place meanings” to represent a fuller range of functional and emotional connections [21]. Within this evolution of sense of place and place meanings, three separate constructs are found consistently—specifically, place dependence, place identity, and place attachment—where place dependence and place identity combine to create place attachment [22].

Place attachment involves the relationships that humans develop with the landscapes, or places that they inhabit, and is a prevalent construct in park and protected area planning research. “Places include the physical setting, human activities, and human social and psychological processes rooted in the setting” [23] (p. 561). As such, sense of place is not inherent to the physical setting; instead, it is lodged in human interpretations of that place [22]. Place attachment relies on symbolic meanings, and we become attached to the meanings that we attribute to cultural resources and landscapes [22]. Place dependence refers to the functional meanings associated with a place [24] or values based on activity-related desires [25]. Place identity is a deeper, more emotional level of meaning that is related to what a place symbolizes for a person, and is often formed from very personal meanings [26]. Impacts to place identity are more likely to affect place attachment than impacts to place dependence due to the depth of emotion that is involved in place identity [24].

Place meanings can occur at the individual or group level, corresponding to personal identity and community cultural values, respectively [19]. Cultural groups bestow meanings upon natural environments, creating landscapes through their social interactions [27]. Place attachment has been described as the “steady accretion of sentiment” [1], (p. 33) through which people develop emotional ties to a place that are strengthened through multiple experiences. The emotional aspect of place attachment often strengthens as the focus of conflicts over resources emerge due to the instinctual nature and depth of emotional meanings [28].

Much study of place meanings has taken place within environmental and community psychology, exploring our relationships to place and bringing our place-related attitudes, behaviors, and relationships to the forefront of understanding our lived experience [1,26,29,30,31]. The relatively unexplored context of cultural resource management and well-documented connections between place meanings and cultural landscapes [27] necessitates an exploration of place-based meanings through an approach that draws on the experiences and opinions of community stakeholders [17]. As places are integral to the formation of both individual and group identity [30], it follows that research, planning, and management would benefit from an analysis of place values and attachment when making decisions about our protected areas [31]. Researchers recommended that managers recognize that place attachment to recreation sites, such as those managed by the NPS, may “warrant special consideration for these places during planning processes” [24] (p. 28). Investigations of place connections can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a community’s dynamics and their relationships with the land that they inhabit or to which they feel connected. Exploring community-level place connections sheds light on shared identity and has been found to be useful in planning for cultural landscapes [31].

Place connections scholarship has clearly advanced in natural resource management (for a review, see Farnum, Hall, and Kruger [32]); however, very little attention has been paid in the literature to cultural resources. Additionally, most place-based research has focused more on recreation, natural resources, and visitors’ attachments to their recreation sites. Focusing research on natural resources and visitors when studying place attachment has the tendency to simplify an extremely complex reality in which community members may have much more intricate and convoluted attachments than visitors [21,30]. Assessment is further convoluted when the place includes cultural landscapes.

2.2. Place Connections, Cultural Heritage, and Climate Change

Where cultural resources exist, meanings and connections exist within the associated communities. Overlooking place meanings that are connected to cultural resources in planning and management can have detrimental effects on communities, including the loss of identity [17,33]. It is quite a monumental task to attempt to distill a wide range of cultural, heritage, and place values into a format that is capable of informing management and policy, because any identities that are related to or attachments to place occur over time within a web of complex psychological and social factors [34]. Furthermore, if ecosystems and landscapes are caches for social meanings, it is essential to understand the relationships that stakeholders have with a resource and how deeply their identity is tied to the place in order to predict and address their responses to changing environmental conditions and management decisions [17,24].

To prepare for the physical and sociocultural impacts of climate change, the more effective management of change can be achieved through an understanding of the social construction of meanings attached to places that will be affected by the change, as altered meanings can affect cultural groups that have incorporated a place into their identity [17]. In particular, the sociocultural impacts of environmental change are seen in the new definitions and meanings that are formed when a group negotiates the new conditions of a valued resource [27]. Consequently, the imminent threats to our cultural resources from climate change—such as inundation, deterioration, and destruction [35]—necessitate an examination of what happens to cultural meanings when cultural resources are impacted, as well as how specific adaptation strategies—such as elevating or moving tangible cultural resources or altering the landscape to reduce sensitivity to impacts [35]—affect cultural meanings [17].

While impacts to place meanings resulting directly from climate change-related impacts have been studied previously, research on this subject remains limited [17,36], even two decades after researchers first identified the need to examine this interaction [10]. Additionally, evaluations of how climate change adaptation strategies are made in response to climate change can impact individuals’ place meanings has yet to be examined, which is particularly important given that the intention of climate change adaptation is technically to ‘save’ or ‘sustain’ a resource and its associated heritage, but it is possible that unintended consequences might include negative impacts to the cultural meanings held by community members [17]. Place connections are by no means fixed or permanent; rather, cultural meanings are constantly in flux. Similar to any relationship, individual and community place connections are always under construction—being torn apart, built back up, strengthened, weakened, and reimagined. Although some researchers have asked “what happens to sense of place when places change?” [29] (p. 630), in this study, we ask more specifically, “how are place connections and cultural heritage affected when cultural resources are impacted by climate change, or are altered through climate change adaptation strategies?”

3. Methods

In this study, we selected to explore community stakeholder connections to the cultural resources and landscapes of Cape Lookout National Seashore, a 56-mile stretch of barrier islands that has been managed by the National Park Service (NPS) since 1966. Cape Lookout National Seashore was selected as a study site given its constantly shifting landscape, which exemplifies the dynamic nature of barrier islands wherein the islands naturally move and roll over with tides and storms shifting the sand, and because nearly all of the park’s infrastructure and cultural resources are considered “highly vulnerable” to sea level rise and storm-related flooding and erosion [37]. The NPS currently provides managers with guidance to direct efforts at those cultural resources that are “both significant and most at risk” [38]. However, managers are grappling with how to apply this broad policy in the adaptation planning efforts of cultural resources [39]. Moreover, this study was stimulated by managers who expressed a desire to understand how stakeholders perceive the interplay between climate change impacts (sea level rise and storm-related flooding and erosion), as well as adaptation strategies to enhance the resilience of cultural resources, and their connections to cultural landscapes and the associated tangible resources that represent aspects of their heritage. In the case of Cape Lookout National Seashore, stakeholders were defined as previous residents or lessees, and their descendants of buildings within two historic districts (Portsmouth Village and Cape Lookout Village).

Study Site Overview

The first known use of the barrier islands at Cape Lookout National Seashore was for fishing encampments built by pre-Columbian peoples. Subsequently, it was continuously inhabited by maritime communities that were involved in shipping, whaling, commercial fishing, port activities, and federal maritime operations when the lifesaving stations, and later Coast Guard stations, were created [40]. The early settlers of the area made a living fishing, farming, whaling, and boat building, which eventually transitioned toward fishing and hunting camps and vacation properties. The two remaining settlements, Portsmouth Village and Cape Lookout Village, are designated historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and 2000, respectively (two areas within Cape Lookout Village, the Cape Lookout Light Station and the Coast Guard Station Complex, were listed prior to the full village designation in 1972 and 1988, respectively).

Portsmouth Village is located at the northernmost point of the park, only a few miles from Ocracoke across the water. Portsmouth Village residents were historically associated with the shipping and lightering industries; Portsmouth used to be the largest town on the Outer Banks, but the shipping industry eventually dwindled. The Life-Saving Station was established in 1894, which helped sustain the village, but the harsh and difficult way of life in the early 20th century resulted in fewer and fewer permanent residents remaining within Portsmouth Village [40]. Yet, descendants and their friends and family formed the Friends of Portsmouth Island, which was an official NPS partner organization, in 1989 under the sponsorship of the Carteret County Historical Society. At the southernmost tip of the park lies Cape Lookout Village. Unlike Portsmouth Village, Cape Lookout Village was never a fully established settlement. Occupation of the area began with the construction of a lighthouse and keeper’s residence in the early 1800s, and a Life-Saving Station in the late 1880s, which was located about two miles south of the lighthouse. By the mid-1900s, most of the residents of Cape Lookout Village were affiliated with the Coast Guard station (workers and their families, who often only visited at certain times of the year). Also in the mid-1900s, several former federal maritime buildings were sold, and new buildings were being constructed as private vacation homes. Some of the structures in both historic districts have already been moved from their original locations at various points in the past.

The histories of these villages tell stories of a resilient community, and illustrate our relationships to the land and sea. The communities who inhabited these islands were faced with an isolated existence and the need to survive in a harsh environment. Residents were challenged with the harsh conditions of the outer banks, but responded by adapting to and finding a way to work with these conditions. Ultimately, climatic and environmental conditions, which threaten the persistence of the physical remains today, dictated the fate of these vulnerable barrier island settlements [40], as few year-round residents remained in 1966 when the NPS acquired the land. The last residents left Portsmouth village in 1971, at which time the NPS gained ownership of the land and buildings within Portsmouth Village. Property owners were offered lifetime leases on their houses in Portsmouth Village, while occupants in Cape Lookout Village who could prove ownership of their property at the time of acquisition were offered the option of taking a 25-year lease or a life estate. All of these leases have since expired, which has created ongoing tensions between the park managers and community members [40], particularly as the NPS has faced a backlog of deferred maintenance (As of 30 September 2015, there was $11.927 billion in deferred maintenance (transportation and other built assets, including historic buildings) across the National Park System. At Cape Lookout National Seashore, this figure was estimated to be $16,665,731 (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/upload/FY-2015-DM-by-State-and-Park.pdf)) has resulted in the deterioration of many residential buildings and plans to enable new third-party leases for buildings in Cape Lookout Village have yet to be implemented. However, the NPS has partnered with the Friends of Portsmouth Island to assist with the maintenance and interpretive content provided in a few former residential buildings in Portsmouth Village.

4. Sampling

Participants for this study were identified using strategic and chain-referral sampling [41] to contact community members. Our sampling strategy did not aim to generate a representative sample, but rather to gain in-depth information about important community connections to CALO’s cultural resources. Our initial sampling began by gathering a list of individuals from park managers and the director of an NPS partner organization (Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center) with known connections to the buildings within the two historic districts. Specifically, the individuals on this list were community members who were former residents and lessees or decedents, as well as community members who had previously expressed interest in the decision-making process for cultural resources at CALO. From this list, we used chain-referral sampling to expand our sample by requesting referrals from both those who participated in the study and those who declined participation. We concluded sampling when we exhausted our sampling list of potential informants for whom we had contact information.

Individuals identified from either sampling strategy were contacted via telephone and/or email (depending on the availability of contact information) and interviewed in-person between November 2015 and August 2016. Participation was voluntary in nature, and no direct incentives were provided for participation.

5. Data Generation and Analysis

Data for this study were generated using an in-depth, semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide was designed with open-ended questions to evoke detailed qualitative responses and included the potential for follow-up questions (i.e., probing) to extract more detail or clarify previous answers. Questions aimed to elicit place meanings, resource impacts and threats, and changes to place meanings without specifically using the term “climate change”. Given the contentious nature of the term climate change, particularly in North Carolina [42], we decided to not specifically include any references to the term in our interview guide. However, specific probing questions about climate change were included if participants’ narratives lacked detail (i.e., specific climate change threats and examples of specific climate adaptation strategies). Additionally, we framed our initial questions to elicit general place meanings at the park unit scale (i.e., Cape Lookout National Seashore generally) and further elicited specific connections to the historic districts and resources within those districts using probing questions.

The qualitative data generated from this research were analyzed through thematic analysis and coding [43]. Field notes of impressions regarding novel and reoccurring insights were made at the conclusion of each interview to help us identify repeating and unique patterns in participants’ narratives. In preparation for analysis, all of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and two researchers performed a first reading of the data to facilitate a basic understanding of participants’ statements, note what meanings were being conveyed, and discern the contextual tone of each interview. After the initial reading, the coding process was initiated. The first phase of open coding helped to identify themes, critical terms, and pivotal events. The second phase, axial coding, was applied as a strategy to organize and group the initial concepts and categories, identify interactions among codes and themes, and to frame causes and consequences. Lastly, selective coding was utilized to identify major themes and narrow our analysis of the data by explicitly looking for relationships to place meaning constructs (place attachment, individual place identity, and community place identity). The themes were used to guide this step of the coding process while we searched through the data for illustrative cases and places where data demonstrated concurrence or contradictions. QSR N*Vivo software v. 10 was used to aid data organization throughout the coding process.

6. Findings and Interpretations

6.1. Participant Attributes

A total of 36 names were collected as potential participants for the study, with 12 provided by the NPS, 15 provided by the director of the partner organization, and nine new names provided by other participants. The chain referral approach increased the breadth of our sample beyond just those who were residents or descendants of former residents, as we followed all of the suggested leads for people with ‘strong connections’ to one or more of the districts. Of these 36 total individuals, we were able to locate current contact information for 22 individuals. We conducted a total of 18 interviews. Although we feel we reached thematic saturation [42] with these interviews (i.e., similar patterns of responses emerged), in actuality, our interviewing ended when the evolving list of contacts ended, as some contacts did not respond to messages, did not wish to participate for reasons such as not feeling qualified, or were unable to schedule an interview during the sampling period.

Within our sample, 13 participants were male and five were female. Only three participants were under the age of 50, while the rest of the participants were between the ages of 50–85. Participants were connected to Cape Lookout National Seashore in a variety of ways, including: being born on the island (1), being descendants of former residents (6), having previously owned homes in one of the villages (3), growing up in the area and frequently visiting one or both districts (13), vacationing within the districts (3), and volunteering and/or working for the NPS within the districts (2).

6.2. Place Meanings Are Intangible Cultural Resource Values

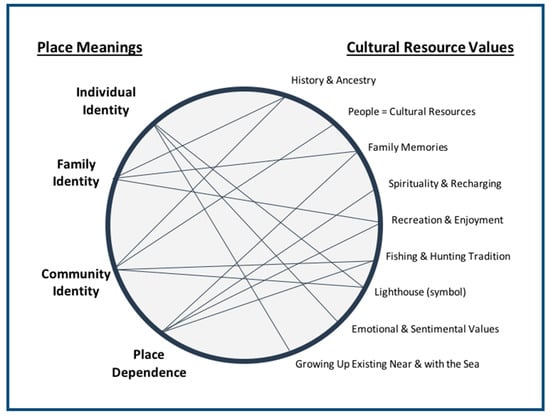

Cape Lookout National Seashore (hereafter, “CALO,” which is the official NPS abbreviation of the park unit) and its cultural resources hold profound and various meanings for the participants of this study. Specifically, we found that the place meanings of community members are informed by place identity (individual, family, and community) and place dependence, and as such there was substantial place attachment. These components of place meanings correspond to the intangible cultural resource values (Figure 1) that were vividly illustrated in participants’ narrative responses and represent the ways in which community members are attached to CALO, and create a sense of place regarding their cultural heritage. Deep sentimental values and feelings of pride associated with CALO give community members the sense that CALO is home, and the Cape Lookout Lighthouse structure was regarded as a tangible symbol that was representative of their intangible cultural values and contributed heavily to community and individual identities through fond memories of tradition and a powerful sense of heritage. Strong emotional attachments became apparent as participants described CALO as an escape or sacred retreat. These intangible values help form and continuously contribute to the special meanings that community members associated with CALO. We briefly describe the participants’ place meanings in the subsections below.

Figure 1.

Place meanings and corresponding cultural resource values identified by study participants.

6.3. Cape Lookout and Place Identity

The place meanings described by study participants are informed by their place identity, which is comprised of individual identity, family identity, and community identity. The values that make up these three identity types are contained in the dimensions of CALO as home, with the Lighthouse being a symbol of this home, and CALO as heritage, which includes concepts of deep roots, family memories, and Banks tradition. Elements of participants’ place identities were strongly linked to intangible cultural resource values rather than tangible cultural resources, as one participant explained, “my connection is one that is primal … it’s almost like a genetic fabric of my being”.

Individual Identity. A sense of individual identity was strong across the majority of participants’ narratives. All but two participants, who explained that CALO lost meaning to them either when they moved off the island or when the NPS gained ownership of the buildings, expressed emotional connections to CALO and the historic districts, and described CALO as home. For some participants, CALO literally was once their home or vacation residence. Other participants who never lived there or did not own property there still considered themselves to be “at home” whenever they visited CALO. Similarly, nearly all of the participants commented on the differences in meanings for people who were born and raised in the “Down East” area (the mainland adjacent to CALO) and grew up “in the light” of the lighthouse to those who moved to the area (“dingbatters”) and those who just visited to use CALO for recreation such as sport fishing. These participants felt that CALO was an innate part of themselves and expressed that their lives and personal identities were inextricably linked to CALO as their “true” home, regardless of their past and current residence status, and they carried these connections with them. Most of the participants’ narratives revealed many deep emotional connections and sentimental values associated with the memories that were made at CALO, so much so that some participants described how leaving the island after visiting is quite painful, and that returning is a great relief.

Family Identity. Participants’ connections to CALO also heavily inform their family identities, which in this case include both ancestral identity and direct experiences of family activities and memories. Many participants described having ancestors who worked for the Life-Saving Service and the Coast Guard, as well as ancestors who were commercial fishermen in the area. Participants identified with these ancestors and their immediate family members, who truly embodied a seafaring/maritime existence. Participants also placed great importance on their family memories that were associated with CALO, describing the countless weekends and summers at CALO with their families. Participants described this family time as truly “quality time” and a major aspect of their family identities.

A subtheme that emerged from interviews regarding family and ancestry was the concept of roots in place and how those ancestral and familial roots informed identity and kept community members feeling connected to their cultural heritage. Living life, growing up, and spending family time on and near “The Banks”—the local name for the islands that constitute CALO—held extraordinary meaning for community members. Not surprisingly, participants also expressed a strong desire to pass on family stories and traditions to future generations so that they could continue to enjoy and feel connected to their special place.

Community Identity. Participants’ place meanings also revealed a strong sense of community identity, which included “meanings associated with local character and culture” [16] (p. 387). Participants were very proud of CALO’s rich and unique history and the history of the area and its people. Community heritage and identity was heavily associated with a connection to the ocean environment and the harsh but beautiful seafaring lifestyles lived in tight-knit communities. Preserving the community’s way of life through its physical remains was a common sentiment. In addition to pride in community heritage and history, participants revealed a strong sense of friendship and community cohesiveness that resulted from the connections to other families who spent their time at CALO and lived in the area.

Cape Lookout Lighthouse: The Symbol of Home. The conceptions of individual, family, and community identity in relation to CALO described above are also deeply tied to the image of the Cape Lookout Lighthouse. The Lighthouse has become symbolic of the place meanings that are associated with CALO, and is considered a “cultural icon”. It is a sentinel of personal and ancestral connections to place, with participants also describing it as being symbolic of the idea of CALO as home. Furthermore, it is seen as a source of reverence as it is a symbol of a strong and resilient community. “I learned at an early age it’s revered … it’s revered by the locals. It’s their lighthouse. … it represents a building of stability. We’ve been through the storms, we’ve weathered every kind of situation you can weather, and since 1859 that has stood like a rock. So people revere it.”

6.4. Cape Lookout and Place Dependence

Participants’ descriptions of their place connections also exemplified the concept of place dependence. Elements of place dependence are evident through responses in which participants describe CALO as an escape and as sustenance. These elements of place dependence were more tied to tangible cultural resources, unlike elements of place identity that were more strongly associated with intangible cultural resources.

Escape: Sacred Retreat, Recharging, and Recreation. CALO conceptualized as escape encompassed meanings that included the place being considered a “sacred retreat” and a place that held strong spiritual value. For example, one participant explained, “You know, it’s almost like sacred ground … we literally treat the place like it’s sacred”. CALO was commonly described is a place where one can spiritually and mentally recharge by removing themselves from modern daily life and feel. Participants expressed the belief that this particular place positively impacts their mental health and overall well-being by expressing such sentiments as, “I actually go there to regain my sanity.” Participants also depend on the island and surrounding waters as the place they prefer to recreate or vacation and where they enjoy themselves and enjoy existing the most.

Livelihood and Sustenance. Community members also conveyed that CALO is a critical source of livelihood and sustenance. Participants also noted the historical importance of CALO’s land and its surrounding waters as the sole means of subsistence and livelihood for past residents. As far back as the whaling and lightering industries, CALO residents made their livings from what the land and sea had to provide, and the experience of surviving on the sparse provisions obtained from fishing and hunting is highly valued by CALO community members. Commercial fishing has been a fundamental activity of CALO residents and the residents of the surrounding communities since the very early settlements on the island, and persists as an important source of income for a large portion of the areas surrounding CALO. Additionally, several participants themselves, as well as many of the residents of the surrounding areas, still make a living from guiding fishing and/or hunting trips as well as from private sightseeing tour services. In addition to commercial and recreational fishing, many community members participate in fishing, clamming, oystering, and hunting as a subsistence or supplemental source of food. Overall, both currently and historically, fishing and hunting traditions are fundamental values of CALO culture.

6.5. Perceptions of Vulnerability and Change: Timing Is Everything

Interviews revealed two equally threatening, overarching issues: (1) climate impacts and (2) deferred maintenance/neglect, including the exacerbation of maintenance issues by weather and storms. However, another threat, the aging community, was also discussed as a source of what is making the districts and their cultural heritage vulnerable to losses. For example, one participant explained, “After my generation is gone, there’s not gonna be any connections there. Not personal connections. And that’s not gonna be long.”

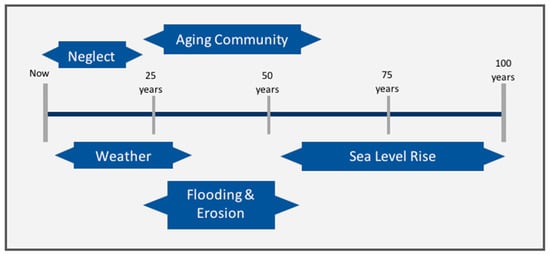

Despite the rural, conservative nature of eastern North Carolina and general public opinion polls on climate change beliefs (e.g., McCright and Dunlap [44]), all of the participants accepted that CALO was threatened by the impending climate change impacts and sea level rise. Many participants even offered anecdotes illustrating how climate change has impacted them personally or the area in general. Yet, many participants also voiced that, although climate impacts may be the most destructive threats to CALO, they believed that most of the climate change impacts would be unlikely to occur in their lifetime. Participants generally judged sea level rise to be an impact that would occur within the next 50–100 years. It is important to note that while participants viewed these climate impacts as unavoidable and quite catastrophic, they deemed them to be a problem that can’t be fixed, generally explaining that “Mother Nature” will have her way with the buildings in the districts and we are powerless to stop it. Other climate-related impacts included short-term weather patterns and associated flooding and erosion.

In general, participants identified “neglect” (i.e., the term that community members used to describe the deferred maintenance and deteriorating condition of many of the historic buildings) and “weather” (i.e., hurricanes and nor’easters) as being the most immediate threats to CALO’s cultural resources, which were perceived as both having “taken a toll” already on the cultural resources and being the most salient threats throughout the next 25 years. These threats were perceived as being somewhat manageable through the proper maintenance and care of the structures; neglect was perceived as the most fixable problem. Participants thought improving maintenance would help immensely to curb weather impacts (i.e., reduce the sensitivity of the buildings, which is an adaptation strategy acknowledged by the NPS [35]). One participant described the difficulty of striking a balance between maintenance and natural forces, stating, “I think neglect is the biggest deal… It’s a battle of corrosions… salt and sun and all sorts of stuff”.

To conceptualize threats to the historic structures within a temporal context, we developed a timeline to illustrate the perceived vulnerabilities (Figure 2). As previously mentioned, deferred maintenance (i.e., “neglect” in the voice of our participants) was the most pressing, current threat. In the next 25–50 years, participants expect that community members with connections to CALO will have all passed away, leaving only children and grandchildren with less direct connections to carry their cultural meanings into the future. Flooding and erosion were also perceived as being unavoidable threats, but participants did not expect to see these impacts for at least 25 years or more. Lastly, participants perceived that the structures would be vulnerable to impacts from sea level rise between 50–100 years from now.

Figure 2.

Timeline of threats to cultural resources identified by study participants.

6.6. Adaptation and Impacts to Place Meanings

Speaking strictly of the historic buildings, our analysis suggests that community members’ place meanings would be most directly impacted by the loss of the Cape Lookout Lighthouse. However, the Portsmouth church and other community buildings were mentioned as tangible resources important to their heritage. Some participants expressed how the meanings that were associated with personal homes were lost during the land acquisition, while others expressed similar pain associated with the loss of private residences when their leases expired. As though they had already mourned the loss of their homes and their personal connections to those buildings, some participants described the sense of loss in the past tense, and many noted that climate impacts would not affect their connections to CALO, the community, or their heritage. Nevertheless, most of the participants avowed they would feel a sense of connection to CALO with or without specific structures, because their place meanings are based on the intangible values of the place. In fact, many participants’ place meanings were so strong that they trusted that their place connections would persist, because they hold the values within themselves and within the community. “People. People that not only lived and worked those islands and the past history, but also the people that created what’s now Cape Lookout National Seashore… That’s the true resource we have.”

When prompted to discuss the potential adaptive strategies, the actions identified fit into three basic categories: (1) landscape or structural changes, (2) maintenance and restoration, and (3) interpretation. In terms of structural and landscape changes, some participants voiced support for beach nourishment, which was perceived as one of the least culturally invasive actions that could be taken to slow the effects of erosion. Conversely, there was no support for more permanent landscape changes such as groins or jetties, with participants explaining the “temporary” nature of such fixes and the inability of such structures to respond to the changing environment of barrier islands (e.g., “A dynamic inlet needs a dynamic solution”).

A few participants reluctantly showed some support for elevating or moving buildings as preferable to total loss of the structures, explaining, “I mean, it’s raise it, move it, or lose it. Those are your only options”. Others felt that science should inform these decisions, stating, “Analyze what impact the projected sea level rise is going to have on these buildings that they have out there and maybe put that in their plan if they need to be moved or elevated.” Others expressed ambiguity or had a difficult time grappling with the value of these actions. For example, one participant explained, “I’m not sure what the value is in trying to raise a house ‘cause… you gain saving everything above that level, but you lose how its people used to live.” However, most of the participants did not support these drastic actions due to the detrimental effect on the integrity and character of the historic districts, explaining, “I just can’t imagine it there. It would lose its soul.” Despite a general lack of support for moving and elevating buildings, some of the participants were more supportive of either moving or raising structures and not receptive to the other. Again, the preference for moving structures corresponded to the perception that the authenticity and integrity of the architecture were the more important attributes to consider, while those participants who advocated raising structures over moving them supported these beliefs by explaining the importance of keeping the structures in their original context.

Overall, whether they supported structural and landscape adaptations or not, participants frequently acknowledged that these engineered solutions are likely to have unintended consequences (“something else is gonna change down the road”), which could potentially be even less desirable than just leaving the buildings as they are, and would definitely impact the “feeling” of the place and connections to “how people used to live”. As such, most participants largely did not want to see drastic measures such as moving and raising structures, because it would impact the cultural meanings and still be only temporary (“Be knowledgeable of the fact that it can only last so long”), with natural forces reclaiming the structures inevitably. Some informants felt that there really was no way to address the problems of climate change vulnerability other than letting “nature take its course”.

Increased restoration and maintenance was, on the whole, the most popular strategy discussed by participants, which was considered preferable to expensive, drastic measures. They considered strengthening the buildings against current and future impacts to be the most worthy use of time and money. Most of the participants wanted to see resources spent on improving the resilience of structures against shorter-term threats such as weather and storms, explaining, “Shore up the buildings, make sure they’re sound and that strong winds aren’t going to blow them down.” Similarly, concern about the loss of cultural integrity from neglect was much more salient in the minds of participants than losses that might be sustained from natural causes or climate impacts. They felt that losing structures to neglect was a much more egregious offense to their culture and place meanings than losing structures to “Mother Nature”. Although they would be sad about losses from inevitable climate impacts, they did not think it would be wise to spend too much time worrying about an inescapable future, explaining, “You can put money in [something], but it’s just gonna go away in the next 15 years anyway.” Maintenance, on the other hand, was perceived by participants as an action that would keep cultural heritage intact for as long as possible, and some participants even expressed a willingness to partner with the NPS to get the work done, explaining:

“I hope the Park Service will take another house and begin working on fixing that up. And again, if done one house at a time, if we can do a house and they can do a house, with the idea that, maybe not necessarily open up for exhibition, but at least restore it enough that it’ll be preserved, then I think that’ll work.”

Similarly, community members envisioned the third-party leasing of structures as a means to overcome the budgetary shortfall, explaining, “The Park Service doesn’t have a reliable source of funding. Sometimes they get a lot of money, sometimes they get no money… So, they don’t really have a way of keeping up stuff, or don’t appear to have a way of keeping up buildings.” Specifically referenced was a previous but unimplemented plan for Cape Lookout Village: “I think a lot of those people were doing a good job and helping the park save a little bit of money and it was a good working relationship with them.” Regardless, participants most enthusiastically expressed the importance of involving the public in planning. They argued that getting people interested, connected to, and invested in preservation is essential for successful adaptation planning and the continuation of place connections among younger and future generations, explaining, “There needs to be more community involvement… Once it becomes sterile, then you’re just riding people over to look. People need a connection. And that’s true of everything.” As such, local knowledge was highly valued by participants, and they expressed that community cohesiveness was an important part of their culture.

Support for increased interpretation was essentially unanimous. Participants advocated for more public displays to represent CALO culture and its community’s way of life. Some of the participants also argued for the inclusion of signage for more of the non-extant structures to explain what used to be there, who used it, and why it is gone. One participant even recommended that digital displays of remnant buildings could enhance preservation of cultural heritage, stating “Maybe if they can if they can preserve just… even the foundations and… maybe what we’ll have is a more digital display… just some sort of electronic version of being able to experience that, as opposed to a physical version of it because that may be all you have.” Many participants also articulated a desire for increased documentation, research, oral histories, and other forms of off-site cultural preservation. Importantly, most of the participants expressed hope that CALO’s cultural heritage would be documented as thoroughly as possible so that future generations would at least have the opportunity to learn about CALO and its community.

In summary, interpretation and documentation strategies were largely considered more favorable than costly structural or landscape adaptations, since participants generally accepted that the physical structures, and possibly the island itself, would be partially, if not completely, lost eventually. “You’re living on the Atlantic Ocean. It’s probably the most powerful force on the planet. So, there are certain things that you might be able to do, and certain things that you’re just helpless to prevent.” Participants also conveyed the critical nature of understanding the potential ramifications of any adaptive measures, cautioning against half-measures that may end up being more wasteful than helpful, as well as unintended impacts to nearby resources and place meanings. Ultimately, participants were hopeful that maintenance and restoration—and partnerships with community members or third-party leases—would provide enough time for future generations to develop their own connections to CALO and its culture. “I just hope and pray that we can somehow maintain those buildings so our, your children, and my grandchildren can actually see those places and walk up and touch those things and touch history.”

7. Limitations

Although the majority of our interviews revealed similar themes (i.e., thematic saturation), we uncovered a few unique perspectives that could be considered negative cases, particularly from individuals who expressed that their place connections were lost when they either moved off the islands or when the NPS gained ownership of their former home. The profiles of these informants suggest that we may not find other similar, and contrary, perspectives (e.g., we were only able to reach one former resident of Portsmouth Village). Additionally, the chain-referral sampling method could have potentially left out important participants if they were not identified by anyone else. However, we explicitly used different locators (i.e., key contacts of different networks; see Penrod, Preston, Cain and Starks [45]) to expand our sample, as well as seeking additional interviews and contacts at a biannual community event within one of the historic districts. Moreover, our goal was not to generalize but rather gain in-depth insights into place meanings and impacts to place connections from climate change threats and adaptation strategies to lessen those threats. Although specific insights are limited to CALO, it is likely that the overarching themes are transferable to other NPS units and other cultural resource sites with historic districts that have strong community associations.

8. Discussion and Implications

Our study builds upon existing studies of place meanings, confirming key constructs, providing unique insights specific to cultural resources, and contributing new information related to impacts from climate change and associated managerial responses. Beyond the basic definition of place attachment as a bond between people and places, the data from this study corroborates the conception of place meanings as a function of both place identity and place dependence. Additionally, the results from the study demonstrate that connections to cultural resources are predominantly based on intangible values, which was a finding not yet uncovered in the literature. Specifically, participants’ strongest connections were to the intangible heritage values held within them, and they were willing to accept the inevitability of climate change impacts to the tangible resources. That said, we also uncovered that previously severed ties to physical resources may have transformed place meanings to reside in the intangible connections to cultural heritage, which provides evidence to the cultural impacts that occur in forced migration situations [17]. Regardless, the timing of both climate and non-climate related impacts, is an important consideration, as participants expressed a sense of urgency to better maintain the buildings in the short-term so as to enable the transference of place meanings to younger generations and maintain cultural heritage. Integrating these voices into climate adaptation planning—or any other planning effort—is critical, particularly to avoid unforeseen impacts particularly to place identity [17,33].

8.1. Place Meanings: Identity and Dependence

Consistent with existing research [16,20,30], place meanings described by the participants of this study encompass values that correspond to individual identity, family identity, and community identity. This research supports previous assertions that individual identity, informed by personal experiences and significant memories, is an important component of place identity [16,19]. Additionally, the data support the inclusion of family identity in place identity, which mirrors the findings of previous studies [16,30]. Community identity in the context of place attachment has been explored as a process by which a community or cultural group ascribes collective meanings to places through shared histories, practice of local cultural traditions within a place, and shared values [16,27,46]. Data from this study corroborate these interpretations of community identity, as participants identify very strongly with the CALO community, and consider the place to be a venue where “they may practice, and thus preserve, their culture” [19] (p. 2).

Although most of the investigations of place dependence have occurred in a recreation and tourism context where exposure to a place is limited or intermittent, place dependence is also applicable to the community members who are connected to a particular place or cultural site [4]. Participants in this study exhibited signs of place dependence in terms of sustenance, escape, and some of the unique elements of the place itself. Consistent with findings from prior place meanings research that documented sustenance as a form of place attachment [29], CALO community members in the past and today have come to depend on CALO as a source of sustenance, which is mainly related to fishing and hunting traditions. Just as those authors documented that people attached to a place regarded the place as a tonic [29], CALO community members depended on CALO as an escape where they could relax, recharge, and feel spiritually fulfilled.

Another exhibited aspect of place dependence was related to the unique elements of CALO that were alleged by participants to be spectacular, unrivaled, and impossible to find elsewhere. These distinctive qualities are highly valued by community members and verify previous research that argues place dependence occurs when a place’s functional meanings cannot be replaced by or transferred to a different setting [24,25,47]. However, in the case of CALO, these unique elements hover somewhere between tangible and intangible values; they are essentially intangible qualities that happen to be inextricable from the physical landscape. This finding suggests that place dependence may not only include functional meanings of a place, but also values which, while inextricable from the physical landscape, are more related to feeling than to function.

8.2. Place Connections to Intangible Cultural Resources

Study results indicate that place meanings are derived more from intangible cultural resource values than from tangible cultural resources. In accordance with an early sense of place, research studies have claimed that people become attached not to places themselves but rather to the meanings and values that they attribute to resources and landscapes [22]. In a similar vein, our findings suggest that CALO community members’ place connections are bound to intangible cultural values and symbolic meanings. Overall, participants indicated that the physical elements of place are neither as integral to their connections nor as important to their identities as are memories, heritage, and culture. Unlike intangible meanings associated with place identity, the cultural values corresponding to participants’ place dependence were largely tangible because they stem from, rely on, and are embedded in the physical setting and cultural landscape. This research reveals that CALO community members are not reliant on the physical setting (e.g., the landscape and specific structures) for meanings that inform their identities. Instead, their place identities are informed by their place meanings, which consist of the intangible cultural values.

In places imbued with culture and associated with a strongly connected community, climate change impacts may “also change the cultures and communities, often in ways that people find undesirable and perceive as loss” [17] (p. 112). However, the participants in this study did not perceive climate change impacts as an avoidable loss. They accept the reality of climate change, and they also acknowledge that Mother Nature will have her way with the island eventually. It was the opinion of most of the participants that no matter when climate impacts happen, place connections, cultural meanings, and the identities that were associated with CALO will remain intact, since the cultural resources are predominantly held within the community members themselves in their memories and stories. This is not to say that individuals would not be deeply saddened by the loss of the physical structures and landscape features, but participants explained that their connections are so strong, and their place meanings are such an intrinsic aspect of their identities, that they would remain intact in the face of any environmental impacts and some adaptive changes. Yet for some, the true point of loss was at the point of forced migration (i.e., when the NPS acquired the land and/or when leases expired), which may have enabled the acceptance of continued loss from climate change impacts. Regardless, preservation of the resources—specifically, maintaining physical structures and enhancing interpretation and documentation in the near-term—are needed to ensure that younger and future generations form the place connections that are necessary to sustain CALO’s cultural heritage.

8.3. The Temporal Aspect of Climate Adaptation Planning

Since cultural landscapes are socially constructed [2,29,48], and climate change impacts will inevitably change these landscapes [5,12], the managers of cultural resources and cultural landscapes must plan for the social impacts that these changes will have on communities. Planning for climate impacts requires an examination of place-based meanings related to change, and we must try to discern “what that [change] means for a group as well as for the individuals who are part of the group” [20] (p. 350). When change happens to a place, the ramifications are quite complex, because the social structures and meanings that are associated with these places are also complex [4,17,49]. Such was the case in this study of CALO community members, whose deep emotional ties to the area make adapting cultural resources a highly convoluted task.

Participants expressed great sadness and a certain sense of loss associated with impacts to existing cultural resources at CALO, particularly from the ongoing deterioration of buildings related to the backlog of deferred maintenance. However, our informants expressed that their feelings and connections would always remain intact, no matter what happens to the physical place. Participants were much more interested in addressing the current and short-term threats to cultural resources, and the findings from this study introduced a distinct temporal component to evaluating and implementing the adaptive strategies for climate impacts. Applying a temporal timeline, such as the one developed in this study, is one strategy for integrating cultural perceptions into adaptation planning [17] that can also help inform management decisions about when to allocate monetary assets and implement adaptive strategies in accordance with community members’ threat perceptions.

Participants identified three basic timeframes for threats and impacts: immediate threats (e.g., neglect, weather, and storms), mid-range threats (e.g., flooding, erosion, and a fading community), and long-range threats (i.e., climate impacts such as sea level rise). Participants were adamant that immediate threats should be addressed as a first priority in management plans, remarking that long-range threats such as sea level rise were not only far in the future, but also inevitable and unstoppable. Since participants viewed climate impacts as occurring only in a future that they likely would not be around to see, they focused more on how regular maintenance and increased interpretation and outreach could at least preserve their cultural heritage throughout their lifetimes and the lives of their children and grandchildren. None of the participants in this study denied the inevitability of climate impacts, and all agreed that climate change planning is important. However, in the minds of the participants, it is more important to plan for more imminent threats—and to seek partnerships and private funding when federal funding is insufficient—since nature will take its course eventually, despite any human interventions or adaptations. The question that remains for future research is: at what point in the future are climate impacts too near-term to continue investing in vulnerable resources?

8.4. Altered Place Connections Transforms Place Meanings

Many of the participants who were interviewed had already experienced loss from the land acquisition and subsequent loss of their homes, expressing that even after that immensely painful loss, their connections remained intact. In other words, some community members rationalized that climate change impacts would not affect their place connections, as there was nothing that nature could take from them that hadn’t already been taken. This finding is distinct from previous research that discovered some community members became “detached” from a place due to increases in government regulations [29] (p. 638), and more similar to research that suggests that changes in the legal designation of a place can have ramifications for people’s emotional attachments to that place [49]. Moreover, it further evidences the impact of limited control in changes to locations (i.e., forced migration) on psychological and emotional well-being [17]. In the case of CALO, a change in designation occurred twice: first, the acquisition of CALO by the state and subsequently the NPS caused feelings of anger, bitterness, and resentment among many community members; second, when the leases on personal homes ran out, former homeowners were quite devastated, and they described experiencing a great sense of personal loss, as well as detrimental impacts to their place connections and meanings. Yet for most of the participants, the loss transformed their place meanings from the tangible resources to intangible values that enable ongoing connections to CALO and their cultural heritage.

Disregarding place meanings in planning and management can have detrimental effects on associated communities, including a loss of identity [5,32]; these authors further advocate for evaluating the ways in which place meanings may be affected by the adaptive strategies that were implemented in response to climate change. Our findings provide additional support for this advice, as we found that participants’ place connections were likely to be impacted more by avoidable threats, adaptive strategies, and the loss of personal property than by unavoidable future impacts from climate change. Put simply, participants perceived impacts from climate change and natural forces to be less offensive to their identities and culture than the impacts and loss caused by perceived neglect (i.e., deferred maintenance), changing the feeling of the historic districts and the integrity of the buildings themselves (i.e., elevating or moving), or the tangible losses experienced when the land and buildings were acquired and when leases expired. Devine-Wright [36] argued that place meanings are particularly relevant for comprehending direct impacts to a resource or place, impacts created by interventions that are meant to preserve that resource, and how those impacts will affect stakeholders. Our study findings similarly indicate that examinations of community members’ place meanings are advantageous for evaluating direct and indirect impacts to place connections. Specifically, this study expands on previous research by shedding light on how place connections will be affected by direct climate impacts to cultural resources, as well as by indirect impacts resulting from adaptive measures taken to preserve those cultural resources. More research is needed to explore other contexts—particularly where historic buildings were not lost to local communities from condemnation—to better understand how climate change impacts and adaptation strategies can alter place meanings and connections to cultural resources.

9. Conclusions

The findings of this study enhance the current body of knowledge regarding place-based meanings and perceptions of landscape change by introducing evaluations of place meanings as they relate to the impacts of climate change and managerial responses on cultural resources and place connections. Although most of the research on climate change adaptation focuses on the tangible or material aspects of climate impacts [11], it is equally important to attend to the cultural dimensions of climate adaptation [5,17]. However, research in this area is significantly less developed, with assessments of climate impacts to place meanings associated with cultural resources being nearly absent from existing literature. This study addressed this knowledge gap by gaining in-depth insights into the intangible aspects of climate change adaptation planning. These insights yielded theoretically new information suggesting that community members’ place meanings are intangible cultural resource values, and that place connections are tied more strongly to intangible cultural values than to tangible cultural resources. Thus, it follows that intangible cultural resource values are a vital, indispensable component of any climate adaptation planning processes that aim to minimize impacts to community members’ place connections and cultural heritage [17].

The strong place meanings and culturally situated management preferences that were defined by participants reiterated the need to integrate the perspectives of community members into planning, especially for contentious issues such as adaptation and prioritization, where impacts of potential management decisions “can be better understood by identifying and examining place meanings” [30] (p. 639). Using community place connections and cultural resource values to inform planning can help managers craft holistic, value-based management strategies that minimize impacts to a community’s place meanings. Participants’ suggestions for adaptation strategies reveal opportunities for managers to increase community engagement and involvement in planning processes, as well as in day-to-day management efforts through collaborative partnerships. Consistent with prior assertions that understanding communities’ connections to places has the potential to diminish conflict between managers and communities [48], our findings suggest that using a collaborative and inclusive approach to planning and management will ease tensions and build trust between the community and resource managers [17]. Explicitly incorporating community values and heritage into planning can enhance the preservation of tangible and intangible connections to cultural resources, as well as sustain place meanings in the context of landscape change.

Author Contributions

E.S. designed the study. M.H. conducted the interviews and coded the transcribed text. E.S. reviewed data quality. M.H. and E.S. wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded under Cooperative Agreement P13AC00443 between the United States Department of Interior, National Park Service and NC State University, Task Agreement Number P14AC01737: Informing Plans for Managing Resources of Cape Lookout National Seashore under Projected Climate Change, Sea Level Rise, and Associated Impacts. Figure 1 and Figure 2 appear in a report developed for the funders and authored by M. Henderson and E. Seekamp, entitled Informing Plans for Managing Resources of Cape Lookout National Seashore under Projected Climate Change, Sea Level Rise, and Associated Impacts: Community Member Interviews Report.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the time and thoughtful perspectives provided by the study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results. However, all data collection protocols were reviewed and approved by both the NC State University Internal Review Board (Human Subjects Committee) and that National Park Service and U.S. Government Office of Management and Budget (OMB Control Number 1024-0224).

References

- Tuan, Y. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, B. Time and Landscape. Curr. Anthropol. 2002, 43, S103–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M. Towards an Anthropological Theory of Space and Place. Semiotica 2009, 200, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentelman, C.K. Place Attachment and Community Attachment: A Primer Grounded in the Lived Experience of a Community Sociologist. Soc. Nat. Res. 2009, 2, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Chapin, F.S.; Ellemor, H. This Must Be the Place: Underrepresentation of Identity and Meaning in Climate Change Decision-Making. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2011, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, B.; Feldman, R.L.; Brinson, M.M.; Horton, B.P.; Orbach, M.K.; Pearsall, S.H.; Reyes, E.; Riggs, S.R.; Whitehead, J.C. Sea-level Rise Research and Dialogue in North Carolina: Creating Windows for Policy Change. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, K.M.; Young, R.S.; Beavers, R.L.; Hoffman, C.H.; Diethorn, B.T.; Norton, S. Adapting to Climate Change in Coastal Parks: Estimating the Exposure of Park Assets to 1m of Sea-level Rise; NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/961; National Park Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2015; pp. 1–193.

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. Are Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by Climate Change? A Systematic Literature Review. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, M.; Beavers, R. Protecting Cultural Resources in Coastal U.S. National Parks from Climate Change. George Wright Forum 2008, 25, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, E. Sharing the Globe: The Role of Attachment to Place. Glob. Environ. Chang. 1991, 1, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresque-Baxter, J.A.; Armitage, D. Place Identity and Climate Change Adaptation: A Synthesis and Framework for Understanding. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Price, J.; Leviston, Z. My Country or My Planet? Exploring the Influence of Multiple Place Attachments and Ideological Beliefs Upon Climate Change Attitudes and Opinions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 30, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Seekamp, E.; McCreary, A.; Davenport, M.; Kanazawa, M.; Holmberg, K.; Wilson, B.; Nieber, J. Shifting Demand for Winter Outdoor Recreation Along the North Shore of Lake Superior Under Variable Rates of Climate Change: A Finite-mixture Modeling Approach. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 123, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Harper, S.L.; Ford, J.D.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Edge, V.L. “From This Place and of This Place: “Climate Change, Sense of Place, and Health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccreary, A.; Fatoric, S.; Seekamp, E.; Smith, J.; Kanazawa, M.A.; Davenport, M. The Influences of Place Meanings and Risk Perceptions on Visitors’ Willingness to Pay for Climate Change Adaptation Planning in a Nature-Based Tourism Destination. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2018, 36, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Anderson, D.H.; Moore, R.L. Social Capital, Place Meanings, and Perceived Resilience to Climate Change. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural Dimensions of Climate Impacts and Adaptations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, D.; Jenkins, P.; Laska, S.; Davis, T. Place Attachment and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana. Organ. Environ. 2007, 20, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.A.; Baker, M.L.; Leahy, J.E.; Anderson, D.H. Exploring Multiple Place Meanings at an Illinois State Park. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2010, 28, 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners Attitudes toward Their Properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a Social Psychology of Place: Predicting Behavior from Place-Based Cognitions, Attitude, and Identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring Place Attachment: Some Preliminary Results, NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research. October 1989. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/value/docs/nrpa89.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2017).

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to Recreation Settings: The Case of Rail-trail Users. Leisure Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greider, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The Social Construction of Nature and the Environment. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E. Environmental Psychology: Mapping Landscape Meanings for Ecosystem Management. In Integrating Social Sciences and Ecosystem Management: Human Dimensions in Assessment, Policy and Management; Cordell, H.K., Bergstrom, J.C., Eds.; Sagamore Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H. Getting from Sense of Place to Place-Based Management: An Interpretive Investigation of Place Meanings and Perceptions of Landscape Change. Soc. Nat. Res. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding Common Ground: The Importance of Place Attachment to Community Participation and Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnum, J.; Hall, T.; Kruger, L.E. Sense of Place in Natural Resource Recreation and Tourism: An Evaluation and Assessment of Research Findings; PNW-GTR-660; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2005.

- Khakzad, S.; Pieters, M.; Van Balen, K. Coastal Cultural Heritage: A Resource to Be Included in Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I. Attachment and Identity as Related to a Place and Its Perceived Plimate. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockman, M.; Morgan, M.; Ziaja, S.; Hambrecht, G.; Meadow, A. Cultural Resources Climate Change Strategy; National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P. Think Global, Act Local? The Relevance of Place Attachments and Place Identities in a Climate Changed World. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, K.M.; Tormey, B.; Thompson, H.; Young, R.; Norton, S.; McNamee, J.; Scavo, R. Cape Lookout National Seashore Coastal Hazards and Climate Change Asset Vulnerability Assessment; Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, Western Carolina University: Cullowhee, NC, USA, 2017; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service. Policy Memorandum 14-02, Climate Change and Stewardship of Cultural Resources; National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. Evaluating a Decision Analytic Approach to Climate Change Adaptation of Cultural Resources along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity-Blake, B.J.; Sabella, J.C. Ethnohistorical Description of Four Communities Associated with Cape Lookout National Seashore; UNCW: Wilmington, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.S.; Longo, S.B.; Shriver, T.E. Politics, the State, and Sea Level Rise: The Treadmill of Production and Structural Selectivity in North Carolina’s Coastal Resource Commission. Sociol. Q. 2018, 59, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. Cool Dudes: The Denial of Climate Change among Conservative White Males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, J.; Preston, D.B.; Cain, R.E.; Starks, M.T. A Discussion of Chain Referral as a Method of Sampling Hard-to-Reach Populations. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2003, 14, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaylov, N.; Perkins, D.D. Community Place Attachment and Its Role in Social Capital Development in Response to Environmental Disruption. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Research; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Budruk, M.; Stanis, S.A.W.; Schneider, I.E.; Anderson, D.H. Differentiating Place Attachment Dimensions Among Proximate and Distant Visitors to Two Water-Based Recreation Areas. Soc. Nat. Res. 2011, 24, 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The Relationship between Place Attachment and Landscape Values: Toward Mapping Place Attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Devine-Wright, P.; Prange, J. Close to the Edge, down by the River? Joining up Managed Retreat and Place Attachment in a Climate Changed World. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2009, 41, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]