Abstract

Quantitative analyses in drug-delivery research are frequently distributed across multiple tools, which increases manual handling and the risk of transcription errors. NanoEDW 1.0 is an open source Python application that integrates calibration-curve generation, encapsulation-efficiency (EE%) calculation, and release kinetics modeling in a single, streamlined workflow. This study aims to validate the performance of NanoEDW 1.0 by benchmarking it against spreadsheet/OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 analyses on experimental datasets from polymeric nanocarrier systems commonly used in drug encapsulation. The software performs linear regression to convert absorbance into concentration, computes EE% from raw experimental values, and fits drug-release profiles to classical models (including zero/first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, and Modified Gompertz) using non-linear least squares with standard goodness-of-fit metrics (R2, RMSE). Results show close agreement with reference workflows for calibration parameters and EE%, as well as statistically comparable release-model fits, while reducing manual steps and analysis time. In conclusion, the validation confirms that NanoEDW 1.0 can streamline routine analyses and enhance reproducibility and accessibility in nanopharmaceutical research; source code and example datasets are provided to foster adoption.

1. Introduction

The continual evolution of computational tools has reshaped scientific research, enhancing precision, efficiency, and accessibility across various disciplines [1,2]. In pharmaceutical and nanotechnology applications—where workflows demand high accuracy and reproducibility—computational strategies streamline data analysis and interpretation [3]. A central challenge in drug delivery system development is accurately determining drug concentration, EE%, and drug release kinetics, as these parameters directly influence the efficacy and safety of nanocarriers in controlled-release formulations [4].

In quantitative nanopharmaceutical workflows [5], calibration curves provide traceable conversion from absorbance to concentration [6], underpinning accurate mass balance and dosing. Encapsulation efficiency quantifies the fraction of drug associated with the carrier, directly impacting payload, yield, and effective dose [7,8,9]. Release kinetics modeling (e.g., zero-/first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, Gompertz) summarizes in vitro release behavior with interpretable parameters that facilitate mechanistic interpretation and comparison across formulations [10,11,12].

Traditional analytical approaches often involve manual spreadsheet calculations or expensive proprietary software, both of which can increase error rates and limit accessibility [13]. Nanoparticles, a key focus in nanotechnology-driven drug delivery, offer controlled-release advantages but typically require extensive data processing for calibration curves, EE determination, and kinetic modeling [14,15,16]. Although spreadsheet-based methods are ubiquitous, they lack automation features, remain labor-intensive, and can introduce inconsistencies in large-scale studies [17,18].

Open source programming, particularly in Python, provides an attractive alternative by enabling flexible, transparent, and scalable computational workflows [19,20,21]. Python’s mature ecosystem of numerical libraries and data visualization tools supports robust, reproducible software development—capabilities increasingly critical in pharmaceutical and nanotechnology research [22]. In response to these needs, NanoEDW 1.0 was developed to integrate calibration curve generation, EE calculations, and drug release kinetics modeling into a single, user-friendly application.

In this study, we describe the design of NanoEDW 1.0 and evaluate its performance against established methodologies, including spreadsheet-based approaches and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025. By consolidating all key steps of nanocarrier evaluation into a unified platform, the software reduces manual input errors, accelerates workflows, and maintains high analytical accuracy. This integrated solution aligns with the broader adoption of data-driven methodologies and underscores the importance of accessible computational tools in drug delivery and nanotechnology research. It is important to note that while robust data analysis tools like OriginLab® exist, the analytical workflow for nanosystems remains fragmented. Researchers must often perform calibration in spreadsheets, manually transfer parameters to calculate EE%, and then export data again to a third-party software for kinetic fitting.

Existing software used in quantitative drug-delivery analysis falls into two categories. First, general curve-fitting suites such as OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 and GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 provide robust non-linear regression and model comparison, yet require users to assemble calibration curves and compute encapsulation efficiency (EE%) in separate steps, without a domain-aware, end-to-end pipeline or automated data hand-off between tasks. Second, dissolution-focused utilities (e.g., DDSolver, KinetDS) emphasize release-profile modeling and similarity factors (f1/f2) but do not natively integrate calibration-curve building or EE% calculation within the same workflow [17,19,23]. NanoEDW 1.0 differs by offering an open source, Python-based GUI that unifies calibration curve → EE% → release kinetics modeling in a single, transparent, and license-free environment—streamlining routine analyses, minimizing transcription errors, and improving reproducibility for researchers and students.

The core contribution of this work is not, therefore, the creation of new statistical models, but rather the development and validation of an integrated and open source software pipeline. NanoEDW 1.0 directly addresses the efficiency, accessibility, and reproducibility of research by automating the data hand-off between modules, mitigating the risk of human transcription error, and providing a single, free solution for the community.

2. Materials and Methods

NanoEDW 1.0 was developed using Python, combining a Tkinter-based graphical user interface (GUI) with core functionalities implemented via NumPy 2.1.1, SciPy 1.14.1, and Matplotlib 3.9.2 [24,25,26,27]. This structure allows for a modular design, wherein each analytical step—calibration curve generation, EE% calculation, and release kinetics modeling—can function independently or in an integrated workflow. The software’s validation features include automated error detection and data integrity checks to minimize user-dependent inconsistencies [1,2].

2.1. Software Architecture and Design

NanoEDW 1.0 consists of three main modules that can be run independently or in sequence: (i) Calibration Curve (Module 1), (ii) Encapsulation Efficiency—EE% (Module 2), and (iii) Release Kinetics Modeling (Module 3). This modular design supports end-to-end analyses while allowing each step to be used on its own.

Calibration Curve (Module 1):

In Module 1, the user inputs absorbance and concentration data obtained from UV-Vis spectrophotometry or another analytical technique [3,4]. NanoEDW 1.0 applies a least-squares linear regression:

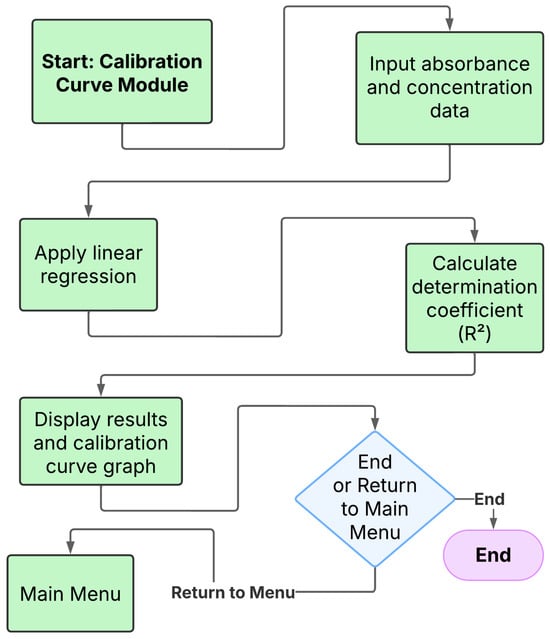

where is absorbance, x is concentration, a and b represent slope and intercept, respectively [4,28,29]. The coefficient of determination (R2) is automatically calculated to assess the goodness of fit (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the calibration curve module in NanoEDW 1.0: enter absorbance–concentration pairs, run linear regression, report R2, and display the calibration plot/results; then, return to the main menu or exit.

Encapsulation Efficiency (Module 2)

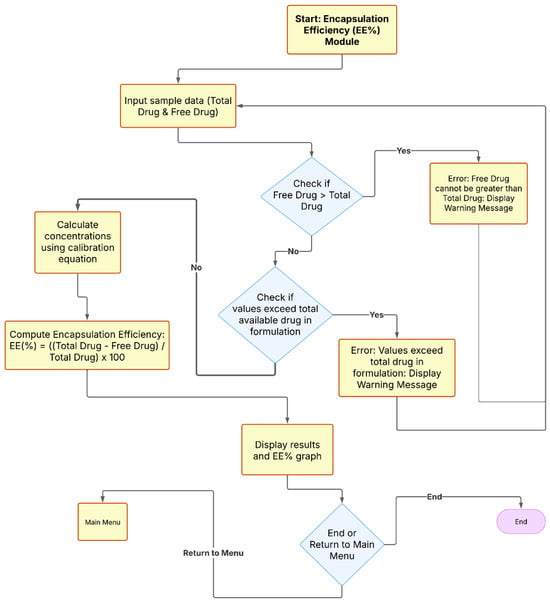

Module 2 uses calibration parameters (slope a and intercept b) from Module 1 to calculate the EE%. The user inputs absorbance values corresponding to total and free drug concentrations. NanoEDW 1.0 then computes EE% using Equation (2) [28,30,31]:

The system checks for inconsistencies, such as free drug exceeding total drug, and generates a warning if necessary. The workflow follows a structured decision-making process to ensure data consistency and minimize errors during input and calculations, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the EE% Module in NanoEDW 1.0: retrieves calibration parameters (a, b) from Module 1 to convert absorbance to total/free drug, validates inputs, computes EE% via Equation (2), displays results/plots, and issues warnings for inconsistent data.

Drug Release Kinetics Modeling (Module 3)

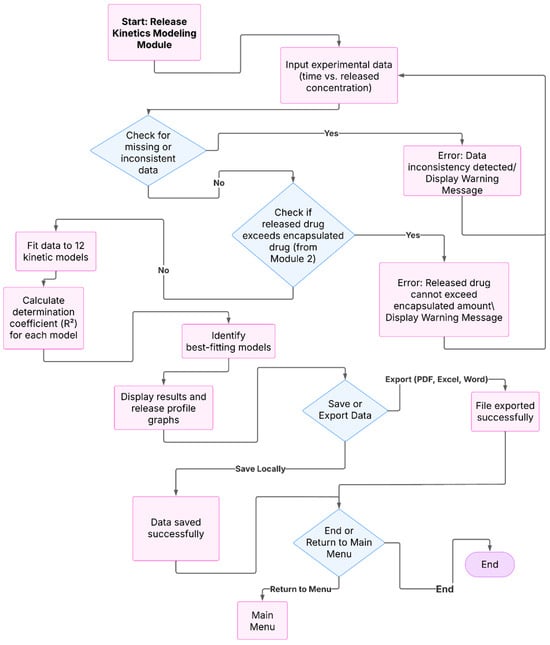

In Module 3, NanoEDW 1.0 evaluates drug release profiles by fitting the experimental data to one or more of 12 kinetic models, namely zero-order [32,33], first-order [33], Higuchi [34], Korsmeyer–Peppas [35,36], Peppas–Sahlin [37,38], Weibull [38], Hopfenberg [39], Hixson–Crowell [40], Probit [41], Logistic [32], Gompertz [42], and modified Gompertz [8]. Each model offers a specific mathematical framework for describing how a drug is released over time, be it through diffusion, erosion, or other combined mechanisms. The software retrieves the encapsulation data from Module 2, ensuring that the cumulative amount released does not surpass the total encapsulated drug. Non-linear regression (via SciPy 1.14.1) is used to compute the best-fit parameters for each model, along with the coefficient of determination (R2), enabling direct comparison of release behaviors and identification of the most suitable kinetic model for a given formulation. The workflow of this module is detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the release kinetics module in NanoEDW 1.0: import time–release data, automatic validation (including check against Module 2 encapsulated amount), fitting to 12 classical models with R2, display of best-fit profiles, and export of results (PDF/Excel/Word).

To facilitate adoption, NanoEDW 1.0 was developed as a cross-platform, running on Windows, macOS, and Linux using Python 3.9–3.12 with Tk (version 8.6 or newer) and standard scientific libraries (e.g., NumPy 2.1.1, Matplotlib 3.9.2). We provide a pre-built Windows installer, while macOS and Linux users can install from source via pip or conda using the supplied requirements file. Mobile operating systems (Android/iOS) are not supported in this release.

2.2. User Interface and Data Visualization

A Tkinter-based GUI facilitates data entry, parameter selection, and real-time visualization [21,43]. Plots generated include calibration curves, EE% charts, and release profiles, with options to export results in various formats (PDF, Excel, Word). Additional tools, such as real-time residual plots, provide immediate feedback regarding fit quality [19,22]. A demonstration of the NanoEDW 1.0 interface and workflow is provided in the Supplementary Material (Video S1), where users can observe a step-by-step example of how each module operates in practice.

2.3. Experimental Validation

NanoEDW 1.0 was validated with experimental data from a Ph.D. research project focusing on the encapsulation of a novel anticancer compound (QPhNO2) into PLGA nanoparticles [44]. Absorbance measurements were performed at various time points, with manual calculations cross-checked in spreadsheet software and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 (64-bit; OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) for comparison. Each measurement was conducted in triplicate to assess reproducibility [8,13]. Validation criteria included determining R2 values in calibration curves, comparing EE% across methods, and evaluating the closeness of fit for drug release models.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were executed within the Python environment, calculating average (μ) (Equation (3)), standard deviation (σ) (Equation (4)), and standard error (SE) (Equation (5)) [45,46]. In these equations, n represents the number of samples in the dataset, and xi corresponds to the i-th measurement or observation:

Goodness-of-fit (R2) and residual plots were used to evaluate calibration curves and kinetic models [14]. Data from replicate measurements were analyzed to ensure reproducibility and assess the reliability of NanoEDW 1.0 in quantifying EE and modeling drug release.

Calibration used OLS with intercept (y = ax + b), unweighted; R2 was computed as 1− (SSres/SStot) about the sample mean. EE% was computed by mass balance using the same calibration parameters. Release kinetics fits used non-linear least squares (Levenberg–Marquardt) with identical initial guesses, parameter bounds, tolerances, and iteration limits across tools. Values are computed at full precision and reported to uniform significant figures.

However, recognizing the limitations of R2 as a sole metric, the selection of the most appropriate release kinetics model (Section 3.3) was also evaluated using information criteria. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were calculated for each of the 12 kinetic models. These criteria penalize models with a higher number of parameters, aiding in the selection of the most parsimonious model that best describes the data.

Furthermore, to quantify the uncertainty of the estimated parameters, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the calibration curve parameters (slope and intercept) and for the kinetic parameters of the best-fit models.

3. Results

This section presents the aim (software validation), then the main capabilities (Modules 1–3: calibration → EE% → release), the comparative benefits versus existing tools, and finally the precision relative to spreadsheet/Origin workflows under harmonized settings.

3.1. Calibration Curve Validation

We first outline the calibration function and its role in the end-to-end workflow with automated data hand-off. Accurate calibration curves are fundamental in quantifying drug concentrations and underpin subsequent analyses of EE% and release kinetics in nanopharmaceutical research [8,9,31]. To assess the performance of NanoEDW 1.0 in generating calibration curves, we compared its linear regression outputs—slope (a), intercept (b), and coefficient of determination (R2) [6,47,48]—against those from spreadsheet-based calculations and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025.

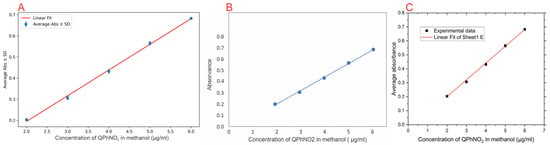

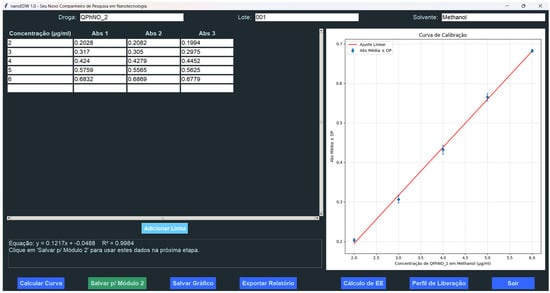

Figure 4 illustrates that NanoEDW 1.0 consistently produced calibration curves comparable to both the spreadsheet and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 results, with R2 values ranging from approximately 0.998 to 0.999. These high coefficients of determination confirm the reliability and accuracy of the software’s regression algorithm. Table 1 (caption below) summarizes the regression parameters for each method, demonstrating minimal variation across all three platforms.

Figure 4.

Comparison of calibration-curve outputs from three platforms: (A) NanoEDW 1.0 showing the best-fit linear regression with mean absorbance ± SD; (B) manual linear fit in spreadsheet software, where the blue dots represent the experimental absorbance–concentration data points and the dotted line denotes the fitted linear regression; (C) OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 linear regression output.

Table 1.

Calibration curve parameters (slope, intercept, and R2) across the three computational approaches. Under harmonized algorithms and settings (Methods), NanoEDW 1.0 reproduces the reference outputs; any residual third/fourth-decimal differences reflect solver tolerance and reporting precision.

NanoEDW 1.0 consistently produced comparable calibration curves, with R2 values ranging from approximately 0.998 to 0.999. Table 1 summarizes the regression parameters, confirming the numerical equivalence. For example, the parameters calculated by NanoEDW 1.0 were slope (a) = 0.1221 (95% CI: [0.1121, 0.1321]) and intercept (b) = −0.0496 (95% CI: [−0.0921, −0.0072]), validating the algorithm’s accuracy.

An added strength of NanoEDW 1.0 is its integrated user interface, which significantly streamlines data input and regression analysis. Figure 5 (caption below) displays the calibration curve module’s GUI, highlighting how raw absorbance values are entered into structured fields, automatically converted into concentration data, and then analyzed through least-squares linear regression. This design minimizes manual steps and enhances reproducibility, especially when large datasets are involved. Moreover, the software flags inconsistencies—such as out-of-range absorbance readings—before calculations proceed, thereby reducing the likelihood of human error.

Figure 5.

GUI of NanoEDW 1.0’s calibration curve module. Users can export results and then proceed to the EE% and release kinetics modules for further analysis.

By automatically saving calibration parameters (slope and intercept), NanoEDW 1.0 automatically transfers these values to the EE% and release kinetics modules. This direct integration eliminates transcription errors and expedites the analytical workflow. Overall, the calibration curve validation confirms that NanoEDW 1.0 not only matches established methods in accuracy but also provides a more efficient and user-friendly solution for researchers studying drug delivery systems.

3.2. Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) Validation

We then present EE% computation with automatic transfer of calibration parameters from Module 1. EE% plays a critical role in nanoparticle-based drug-delivery systems, as it directly influences drug release profiles, therapeutic efficacy, and formulation stability [31,49]. Accurate determination of EE% ensures optimal nanoparticle loading, minimizing both waste and production costs [7,50]. Although various methods—ranging from UV-Vis spectrophotometry and HPLC to computational tools—are routinely employed, the inherent need for manual data manipulation can introduce errors and affect reproducibility [51].

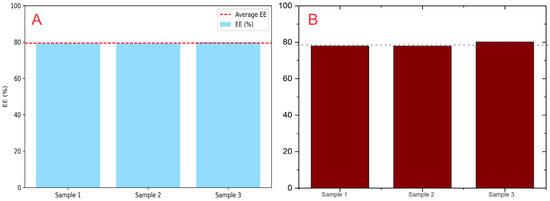

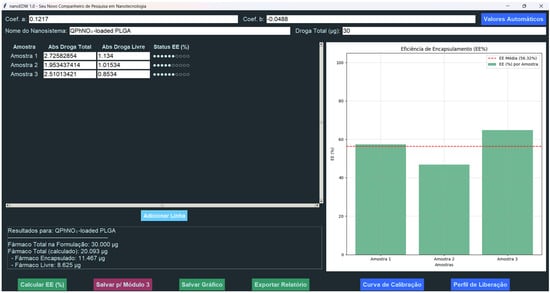

To evaluate NanoEDW 1.0’s EE% calculation module, we investigated QPhNO2-loaded PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) nanoparticles and compared results from NanoEDW 1.0 with those obtained using OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 and spreadsheet-based analyses. As shown in Figure 6, the EE% determined by NanoEDW 1.0 (79.39% ± 0.44) closely matched that from OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 (79.39% ± 0.45) and spreadsheets (79.38% ± 0.46). These findings confirm the high accuracy of NanoEDW 1.0, demonstrating its capacity to replicate results produced by widely used computational tools, while offering a more automated and efficient workflow.

Figure 6.

EE% comparison: NanoEDW 1.0 (A) auto-integrates calibration and absorbance data, whereas OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 (B) requires manual preprocessing. In subfigure B, the darker red bars represent the EE% values obtained using OriginLab® OriginPro 2025; the color is used solely for visual distinction. Results are consistent across tools.

A key benefit of NanoEDW 1.0 lies in its specialized design, which seamlessly merges Module 1’s calibration data (slope a and intercept b) with raw absorbance measurements. This automated approach removes the need for separate data formatting steps, markedly reducing human error and boosting reproducibility. Users can input absorbance values, instantly compute EE%, visualize results, and export comprehensive reports—all in a single click. Figure 7 showcases the module’s graphical interface, underscoring how the streamlined data entry and output facilitate more efficient laboratory workflows.

Figure 7.

GUI of the EE% Module in NanoEDW 1.0. This module automatically computes EE% from absorbance data, incorporating calibration curve coefficients from Module 1 and displaying results in bar-chart form. Users can then save, export, or proceed to additional analyses.

By contrast, OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 and spreadsheets require multiple steps—such as data import, regression calculations, and complex equation inputs—which increases both the time and the likelihood of errors, particularly for large datasets or inexperienced users. NanoEDW 1.0’s integrated architecture makes it an integrated tool for laboratories in pharmaceutical sciences, nanotechnology, and biomedical research. Moreover, its accessible design offers significant educational value: researchers and students can rapidly learn the software, focusing on experimental insights rather than computational minutiae.

Finally, the automated processing and real-time visualization of EE% align with contemporary trends in computational drug development, which emphasize automation and reproducibility to mitigate experimental variability [4,52,53]. Consequently, NanoEDW 1.0 represents an important advance in EE% analysis, delivering both accuracy and ease of use. These validation results confirm that NanoEDW 1.0 effectively automates EE% determination for QPhNO2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles, reducing manual effort while maintaining high analytical precision, thus providing a more accessible and efficient alternative to traditional data processing tools.

3.3. Validation in Release Kinetics Profile Tests

Finally, we compare release-model fits against spreadsheet/Origin under harmonized settings and predefined metrics. Accurate drug release modeling is also paramount in pharmaceutical research, especially for controlled-release platforms such as polymeric nanoparticles [12,38,54]. In NanoEDW 1.0, Module 3 automates the fitting of release profiles to multiple kinetic models by integrating data from the Calibration Curve (Module 1) and EE% (Module 2). Rather than relying on separate steps and multiple software platforms (e.g., spreadsheets or OriginLab® OriginPro 2025), NanoEDW 1.0 consolidates the workflow: users simply import raw absorbance data, choose a kinetic model, and generate release curves in a single operation.

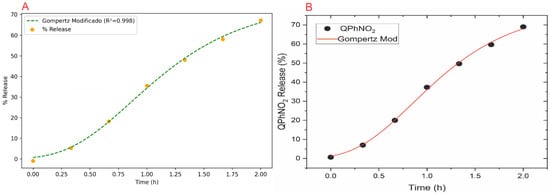

The validation of the release kinetics module is presented in detail in Table 2. This analysis directly compares the fitted model parameters and their associated errors (±), as well as the R2 values, between NanoEDW 1.0 and OriginLab. As shown, the R2 values from both software packages were nearly identical for most models, such as Higuchi (0.998 vs. 0.999), Probit (0.995 vs. 0.998), and Logistic (0.999 vs. 0.999).

Table 2.

Comparison of release kinetics parameters and coefficients of determination (R2) between NanoEDW 1.0 and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 for QPhNO2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles in pH 1.2 medium. Under harmonized algorithms and settings (Methods), NanoEDW 1.0 reproduces the reference outputs; any residual third/fourth-decimal differences reflect solver tolerance and reporting precision.

More importantly than R2 similarity, the table directly addresses parameter uncertainty. It demonstrates that the model fitting parameters themselves (e.g., ‘k’, ‘n’, ‘a’, ‘b’) are statistically comparable within their reported error margins. For instance, for the Modified Gompertz model—which yielded identical R2 values (0.998) on both platforms—NanoEDW 1.0 calculated the ‘k’ parameter as 1.715 ± 0.038. This value is statistically indistinguishable from the 1.666 ± 0.121 calculated by OriginLab, given their error margins.

This robust numerical equivalency in the model parameters and their associated errors successfully validates the non-linear regression algorithms implemented in NanoEDW 1.0, confirming its accuracy against the industry standard.

Figure 8 further illustrates the release profile fits achieved by NanoEDW 1.0 and OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 for the Modified Gompertz model, which yielded R2 values of 0.998 in both software packages. This close agreement demonstrates the robustness of NanoEDW 1.0’s non-linear regression routines, as well as the consistency between the two platforms.

Figure 8.

Modified Gompertz fits for QPhNO2 release: (A) NanoEDW 1.0—experimental %release with best-fit curve (R2 = 0.998); (B) OriginLab® OriginPro 2025—experimental data with fitted Gompertz model. Both show comparable fits.

A principal advantage of NanoEDW 1.0 lies in its automatic data hand-off of EE% results and calibration parameters to the curve-fitting process, eliminating the need for separate calculations. This integration not only speeds up data analysis but also minimizes the risk of human error—particularly critical when handling large datasets. Moreover, NanoEDW 1.0’s user-friendly interface and built-in model selection make it accessible to researchers regardless of computational background.

In addition to technical precision, the software’s automation and immediate visual feedback enhance laboratory workflows, allowing users to export comprehensive reports (PDF, Excel, Word) with minimal effort. This contrasts with the more labor-intensive procedures in traditional spreadsheet analysis or specialized software like OriginLab® OriginPro 2025, where non-standard models require manual coding.

The validation of NanoEDW 1.0’s three modules—calibration curve, EE%, and release kinetics—revealed strong agreement with results from both OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 and spreadsheet-based methods. In calibration curve tests, the software’s linear regression yielded R2 values consistently above 0.998, mirroring the accuracy of established tools and demonstrating robust data consistency. In the encapsulation module, NanoEDW 1.0 maintained accuracy comparable to standard software while minimizing user interventions, thus reducing the potential for data-entry errors. Finally, the release kinetics module reliably fits drug release profiles to multiple mathematical models, again matching or exceeding the performance of alternative software packages in terms of R2 and parameter estimates.

As demonstrated throughout this section, NanoEDW 1.0 delivers a streamlined, integrated workflow that automates critical tasks: from calibration to EE calculation and final release kinetics modeling. Beyond its technical precision, NanoEDW 1.0’s intuitive graphical interface provides both experienced researchers and students a GUI with built-in model selection, context-sensitive help, and a one-click export environment that supports reproducibility, reduces overhead, and fosters improved data interpretation in drug delivery research.

3.4. Future Perspectives

The successful development and validation of NanoEDW 1.0 marks a significant advance in computational tools for drug release research, particularly by integrating calibration curve analysis, EE% calculations, and release kinetics modeling into one automated workflow. Despite these achievements, several avenues remain for enhancing the software’s functionality and addressing identified limitations:

Expansion of Mathematical Models: NanoEDW 1.0 currently supports 12 kinetic models, covering a broad range of controlled-release mechanisms. Future versions could incorporate additional or more specialized models, such as enzyme-mediated or pH-dependent release equations, thereby extending the software’s applicability to a wider array of drug delivery systems, including stimulus-responsive nanocarriers [55,56].

Integration of Advanced Machine Learning Techniques: Machine learning algorithms have demonstrated the potential to predict drug release profiles by leveraging both experimental and structural parameters. Incorporating AI-based features could allow NanoEDW 1.0 to suggest the most appropriate kinetic model for a given dataset, improving selection accuracy and reducing user-dependent bias [57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Enhanced GUI and User Experience: Although NanoEDW 1.0 offers a user-friendly environment, additional interactive capabilities—such as drag-and-drop data import, real-time parameter tuning, and customizable visualizations—could further improve the user experience. These features would be particularly beneficial for comparative analyses across multiple formulations.

Enhanced Statistical Analysis: Recognizing the importance of moving beyond R2 metrics, future versions of NanoEDW 1.0 will focus on incorporating more advanced statistical analyses. This will include the automated calculation of model selection criteria, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), to allow for more robust comparisons between kinetic models. Furthermore, we plan to implement the generation of residual diagnostics and the calculation of confidence intervals for all model parameters as a standard output, enhancing the statistical rigor and interpretability of the results.

Cloud-Based and Multi-Platform Support: As of now, NanoEDW 1.0 operates exclusively as a local application. Implementing a web-based or cloud-integrated variant could foster collaborative research by enabling multiple users to access and analyze data remotely. A web-based/cloud variant could enable collaborative use; desktop builds already support Windows, macOS, and Linux.

Automated Experimental Data Importation: Linking NanoEDW 1.0 directly to laboratory equipment (e.g., UV-Vis spectrophotometers and HPLC systems) would enable real-time data acquisition, reducing manual input errors and further streamlining the analytical workflow.

Educational Implementation and Training Modules: Thanks to an intuitive user interface/user experience (UI/UX; Interface do Usuário/Experiência do Usuário)—characterized by a guided three-step workflow (Calibration → EE% → Release), consistent terminology, sensible defaults, and context-sensitive help—NanoEDW 1.0 shows strong potential as a teaching tool for pharmacokinetics and nanomedicine. Live plots, inline unit/range validation, and one-click report export further support classroom use. Future releases will add step-by-step tutorials and case studies to facilitate self-guided learning.

4. Discussion

The validation studies confirm that NanoEDW 1.0 delivers calibration-curve performance on par with established platforms while markedly simplifying the workflow. In our calibration curve module, the coefficients of determination (R2 ≈ 0.998–0.999) closely mirror those reported for OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 and manual spreadsheet methods [9,24], demonstrating that the least-squares fitting implemented via SciPy 1.14.1 accurately reproduces industry-standard regression quality. This finding supports our hypothesis that an integrated, open source pipeline can replace proprietary software without loss of precision.

Encapsulation-efficiency (EE) measurements for QPhNO2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (79.4 ± 0.4%) agree with values obtained by traditional HPLC-UV and UV–Vis approaches [7,8]. Crucially, NanoEDW 1.0 automates the propagation of calibration parameters into EE calculations, obviating manual equation entry and intermediate file transfers. This end-to-end automation not only reduces the risk of transcription errors—an issue well documented in spreadsheet-based analyses [64]—but also accelerates batch processing, which is increasingly important for high-throughput formulation screening.

In drug-release modeling, NanoEDW 1.0’s non-linear regression routines successfully fit twelve classical kinetic models with R2 consistently above 0.95. These fits are comparable to those obtained in OriginLab® OriginPro 2025 for the Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, and Gompertz models, validating the choice of SciPy’s 1.14.1 optimization algorithms. The immediate visualization of residuals and goodness-of-fit metrics within the graphical interface further enhances model selection, offering a clear advantage over command-line or spreadsheet workflows that require iterative manual fitting.

Together, these results have important implications. First, by democratizing access to advanced nanocarrier analytics, NanoEDW 1.0 can lower technological barriers for resource-limited laboratories that cannot afford expensive licenses. Second, its modular architecture means that new kinetic or mechanistic models—such as pH-responsive release or enzyme-mediated degradation—can be added with minimal code refactoring. Finally, the rapid transition from raw data to fully annotated results supports just-in-time decision making during formulation development, thereby speeding the translation of nanosystems from bench to application.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. Currently, NanoEDW 1.0 exists only as a standalone desktop application; future cloud-based deployment would enable collaborative data sharing and remote access. The current GUI, implemented in Tkinter, could be enhanced with drag-and-drop import, real-time parameter sliders, and customizable report templates. Moreover, although twelve kinetic models cover many standard scenarios, emerging mechanisms—such as multi-phase or stimuli-triggered release—are not yet supported.

Going forward, we envision several avenues for expansion: mechanistic model integration, machine learning augmentation, instrument connectivity, web and cross-platform deployment, and educational modules.

Compared with current analysis tools, NanoEDW 1.0 offers an integrated, domain-aware workflow that links calibration-curve construction, encapsulation-efficiency calculation, and release kinetics modeling with automated data hand-off, thereby reducing manual transcription and error propagation. In validation against spreadsheet and commercial curve-fitting suites, NanoEDW reproduced calibration parameters and EE% and delivered kinetic fits that were statistically comparable, while shortening analysis time and standardizing outputs.

Unlike general-purpose packages that require users to stitch together separate steps—or dissolution-focused utilities that limit functionality to release profiling and similarity metrics—NanoEDW concentrates the full pipeline in a single open source, Python-based GUI with immediate visualization and one-click export of publication-ready reports (PDF, Excel, Word). The interface lowers the barrier for non-programmers; the breadth of included models (e.g., zero/first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Weibull, Gompertz, and variants) supports mechanistic interpretation; and the license-free distribution enhances accessibility and reproducibility for both research and teaching settings. Although we conducted exploratory tests on other delivery systems, the rigorous validation protocol was applied exclusively to nanosystems. We therefore limit our formal claims to polymeric nanocarriers and consider applications beyond this domain as preliminary.

5. Conclusions

NanoEDW 1.0 integrates calibration-curve generation, EE% calculation, and release kinetics modeling in a single, license-free GUI. Under harmonized settings, the software reproduces spreadsheet/Origin outputs while reducing manual handling. The present validation focuses on nanosystems; broader applications are preliminary. Code, datasets, and system requirements are provided for reproducibility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/j8040047/s1, Video S1: Demonstration of the NanoEDW 1.0 software. This video shows a practical example of how the program works and how each module operates in the analysis workflow.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—E.D.M.; Data curation—E.D.M.; Formal analysis—E.D.M., H.d.S.e.S.; Investigation—E.D.M., H.d.S.e.S.; Methodology—E.D.M.; Resources—E.D.M.; Software—E.D.M.; Supervision—H.d.S.e.S., M.P.d.C.; Validation—E.D.M., M.S.R.; Visualization—E.D.M., H.d.S.e.S., M.P.d.C.; Writing—original draft preparation—E.D.M., H.d.S.e.S., M.P.d.C.; Writing—review and editing—H.d.S.e.S., M.P.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate and reproduce the results are contained in the main manuscript. Minimal working datasets and source code are provided via the Data/Code Availability statement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the developers of NumPy 2.1.1, SciPy 1.14.1, and Matplotlib 3.9.2 for their open-source contributions, which form the backbone of NanoEDW 1.0.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajput, A.; Shevalkar, G.; Pardeshi, K.; Pingale, P. Computational Nanoscience and Technology. OpenNano 2023, 12, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela Neto, O.P. Intelligent Computational Nanotechnology: The Role of Computational Intelligence in the Development of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2014, 11, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judy, E.; Lopus, M.; Kishore, N. Mechanistic Insights into Encapsulation and Release of Drugs in Colloidal Niosomal Systems: Biophysical Aspects. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 35110–35126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwini, T.; Narayan, R.; Shenoy, P.A.; Nayak, U.Y. Computational Modeling for the Design and Development of Nano Based Drug Delivery Systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Fierro, I.; Guerrante, R.; Mendes, F.; de M. Alencar, M.S. Trends in Nanopharmaceutical Patents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7016–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, R. Misuse of Beer-Lambert Law and Other Calibration Curves. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, N.V.N.; Prasanna, P.M.; Sakarkar, S.N.; Prabha, K.S.; Ramaiah, P.S.; Srawan, G.Y. Microencapsulation Techniques, Factors Influencing Encapsulation Efficiency. J. Microencapsul. 2010, 27, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.-S.; Chong, S.; Rompas, J. (Eds.) Chemotherapeutic Engineering: Collected Papers of Si-Shen Feng—A Tribute to Shu Chien on His 82nd Birthday; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, S.S. The Drug Encapsulation Efficiency, in Vitro Drug Release, Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel-Loaded Poly(Lactide)-Tocopheryl Polyethylene Glycol Succinate Nanoparticles. In Chemotherapeutic Engineering: Collected Papers of Si-Shen Feng—A Tribute to Shu Chien on His 82nd Birthday; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paarakh, M.P.; Jose, P.A.; Setty, C.M.; Peterchristoper, G.V. Release Kinetics—Concepts and Applications. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- AlMajed, Z.; Salkho, N.M.; Sulieman, H.; Husseini, G.A. Modeling of the In Vitro Release Kinetics of Sonosensitive Targeted Liposomes. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, H. Application of Mathematical Models in Drug Release Kinetics of Carbidopa and Levodopa ER Tablets. J. Dev. Drugs 2017, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.D.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano Based Drug Delivery Systems: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Biswas, A.; Shukla, A.; Maiti, P. Targeted Therapy in Chronic Diseases Using Nanomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Vehicles. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnera, M.; Vicario-De-la-torre, M.; Andrés-Guerrero, V.; Bravo-Osuna, I.; Molina-Martínez, I.T.; Herrero-Vanrell, R. Validation of a Rapid and Easy-to-Apply Method to Simultaneously Quantify Co-Loaded Dexamethasone and Melatonin PLGA Microspheres by HPLC-UV: Encapsulation Efficiency and In Vitro Release. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branquinho, R.T.; Mosqueira, V.C.F.; Kano, E.K.; De Souza, J.; Dorim, D.D.R.; Saúde-Guimarães, D.A.; De Lana, M. HPLC-DAD and UV-Spectrophotometry for the Determination of Lychnopholide in Nanocapsule Dosage Form: Validation and Application to Release Kinetic Study. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2014, 52, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Gao, Y.; Bou-Chacra, N.; Löbenberg, R. Evaluation of the DDSolver Software Applications. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 204925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, C.P.; Lübbesmeyer, M.; Jin, E.H.; McDonald, M.A.; Koscher, B.A.; Guimond, N.; Di Rocco, L.; Kayser, H.; Leweke, S.; Niedenführ, S.; et al. Open-Source Chromatographic Data Analysis for Reaction Optimization and Screening. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendyk, A.; Jachowicz, R.; Fijorek, K.; Dorozyński, P.; Kulinowski, P.; Polak, S. KinetDS: An Open Source Software for Dissolution Test Data Analysis. Dissolut Technol. 2012, 19, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachimi, C.; Belaqziz, S.; Khabba, S.; Chehbouni, A. Data Science Toolkit: An All-in-One Python Library to Help Researchers and Practitioners in Implementing Data Science-Related Algorithms with Less Effort. Softw. Impacts 2022, 12, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.B.; Gupta, R. Contemporary Computational Applications and Tools in Drug Discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Zou, A.; Li, W.; Yao, C.; Xie, S. DDSolver: An Add-in Program for Modeling and Comparison of Drug Dissolution Profiles. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Walt, S.; Colbert, S.C.; Varoquaux, G. The NumPy Array: A Structure for Efficient Numerical Computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2011, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elan Maulani, I.; Azis, I.; Cahya, M.N.; Komarudin, K.; Sagita, A. bahar Implementation of Object-Oriented Programming with Pyqt: Development of Calculation Application. Devotion J. Res. Community Serv. 2024, 5, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoyarkar, A.; Solanki, A.; Balbudhe, A. Application Development Using Kivy Framework. IJARCCE 2019, 8, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappold, B. Best Practices for Routine Operation of Clinical Mass Spectrometry Assays. In Mass Spectrometry for the Clinical Laboratory; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnichenko, I.I.; Shilov, Y.E. Analysis of Biological Samples in a Contemporary Laboratory Practice (Review). Drug Dev. Regist. 2019, 8, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V. Encapsulation Nanotechnologies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781118344552. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, M. Handbook of Encapsulation and Controlled Release; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Polli, J.E.; Rekhi, G.S.; Augsburger, L.L.; Shah, V.P. Methods to Compare Dissolution Profiles and a Rationale for Wide Dissolution Specifications for Metoprolol Tartrate Tablets. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Sousa Lobo, J.M. Modeling and Comparison of Dissolution Profiles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 13, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, T.; Ueda, M.; Kakemi, M.; Kameda, H. Rate of Release of Medicaments from Ointment Bases Containing Drugs in Suspension. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1975, 23, 3288–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.Y.; Bala, S.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; di Cagno, M.P. Interpreting Non-Linear Drug Diffusion Data: Utilizing Korsmeyer-Peppas Model to Study Drug Release from Liposomes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 138, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A. Analysis of Fickian and Non-Fickian Drug Release from Polymers. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1985, 60, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peppas, N.A.; Sahlin, J.J. A Simple Equation for the Description of Solute Release. III. Coupling of Diffusion and Relaxation. Int. J. Pharm. 1989, 57, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenbucher, F. Letters to the Editor: Linearization of Dissolution Rate Curves by the Weibull Distribution. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1972, 24, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopfenberg, H.B. Controlled Release from Erodible Slabs, Cylinders, and Spheres. In Controlled Release Polymeric Formulations; American Chemical Society (ACS): Washington, DC, USA, 1976; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hixson, A.W.; Crowell, J.H. Dependence of Reaction Velocity upon Surface and Agitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1931, 23, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.P.; Tsong, Y.; Sathe, P.; Liu, J.P. In Vitro Dissolution Profile Comparison- Statistics and Analysis of the Similarity Factor, F2. Pharm. Res. 1998, 15, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabón, C.V.; Frutos, P.; Lastres, J.L.; Frutos, G. Matrix Tablets Containing HPMC and Polyamide 12: Comparison of Dissolution Data Using the Gompertz Function. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1994, 20, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TKInter. Tkinter. Python Standard GUI Library. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/tkinter.html (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Montenegro, E.D.; Nunes, J.M.; Ramos, I.F.S.; Almeida, R.G.; da Silva Júnior, E.N.; Rizzo, M.S.; da Silva-Filho, E.C.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Silva, H.S.; Costa, M.P. Characterization of the Interaction of a Novel Anticancer Molecule with PMMA, PCL, and PLGA Polymers via Computational Chemistry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, V.; Neter, J.; Wasserman, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1975, 138, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, P.B. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis. J. Appl. Stat. 2013, 40, 2775–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.L.; Markus, C.; Lim, C.Y.; Tan, R.Z.; Sethi, S.K.; Loh, T.P. Calibration Practices in Clinical Mass Spectrometry: Review and Recommendations. Ann. Lab. Med. 2023, 43, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, C. Evaluation of Calibration Equations by Using Regression Analysis: An Example of Chemical Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadi, S.; Ashrafi, H.; Azadi, A. Mathematical Modeling of Drug Release from Swellable Polymeric Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 7, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.N.; Hubber, I.; Siqueira, M.; Barbosa, G.M.; De Lima Moreira, D.; Holandino, C.; Pinto, J.C.; Nele, M. Preparation and Cytotoxicity of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Nanoparticles for Drug Encapsulation. In Proceedings of the Macromolecular Symposia, Varanasi, India, 19–21 March 2012; Volume 319. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.L.; Mitchell, K.; Rowe, P.; Armstrong, D.J.; Elliott, P.N.C.; Rostron, C.; Hogan, J.E. Mathematical Modelling of Drug Release from Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose Matrices: Effect of Temperature. Int. J. Pharm. 1991, 71, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti Mittu, A.C.; Chauhan, P. Analytical Method Development and Validation: A Concise Review. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2015, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Ruth, H.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Software News and Updates AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Mejía, S.P.; Orozco, J. Recent Advances in Polymeric Nanoparticle-Encapsulated Drugs against Intracellular Infections. Molecules 2020, 25, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, K.H.; Dighe, P.A.; Kharat, A.R.; Patil, S.V. Mathematical Models of Drug Dissolution: A Review. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm. 2014, 3, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, B. Mathematical Models Describing Polymer Dissolution: Consequences for Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 48, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcikowski, M.; Siedlecki, P.; Ballester, P.J. Building Machine-Learning Scoring Functions for Structure-Based Prediction of Intermolecular Binding Affinity. In Docking Screens for Drug Discovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Raheem, A.K.; Dhannoon, B.N. Automating Drug Discovery Using Machine Learning. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2023, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronobis, W.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K.R. Many-Body Descriptors for Predicting Molecular Properties with Machine Learning: Analysis of Pairwise and Three-Body Interactions in Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 2991–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfan, A.; Al Rahwanji, M.J.; Hanano, A.; Al-Obaidi, H. A Comprehensive Study on Nanoparticle Drug Delivery to the Brain: Application of Machine Learning Techniques. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Srivastava, D.; Sahu, M.; Tiwari, S.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Artificial Intelligence to Deep Learning: Machine Intelligence Approach for Drug Discovery. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1315–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahshoori, I.; Golriz, M.; Nobre, M.A.L.; Mahdavi, S.; Eshaghi Malekshah, R.; Javdani-Mallak, A.; Namayandeh Jorabchi, M.; Ali Khonakdar, H.; Wang, Q.; Mohammadi, A.H.; et al. Simulation-Based Approaches for Drug Delivery Systems: Navigating Advancements, Opportunities, and Challenges. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 395, 123888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, A.I.; Negut, I. Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Drug Discovery in the Context of Revolutionizing Drug Delivery. Life 2024, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, G.; Thorne, S. A Pilot Study Exploring Spreadsheet Risk in Scientific Research. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1703.09785. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).