Development of Biodegradable Bioplastic from Banana Pseudostem Cellulose

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Equipment

2.3. Sample Selection

2.4. Cellulose Quantification

2.5. Cellulose Extraction

2.6. Bioplastic Synthesis

2.7. Characterization

2.7.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.7.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetric (DSC)

2.7.4. Tensile Strength Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cellulose Content

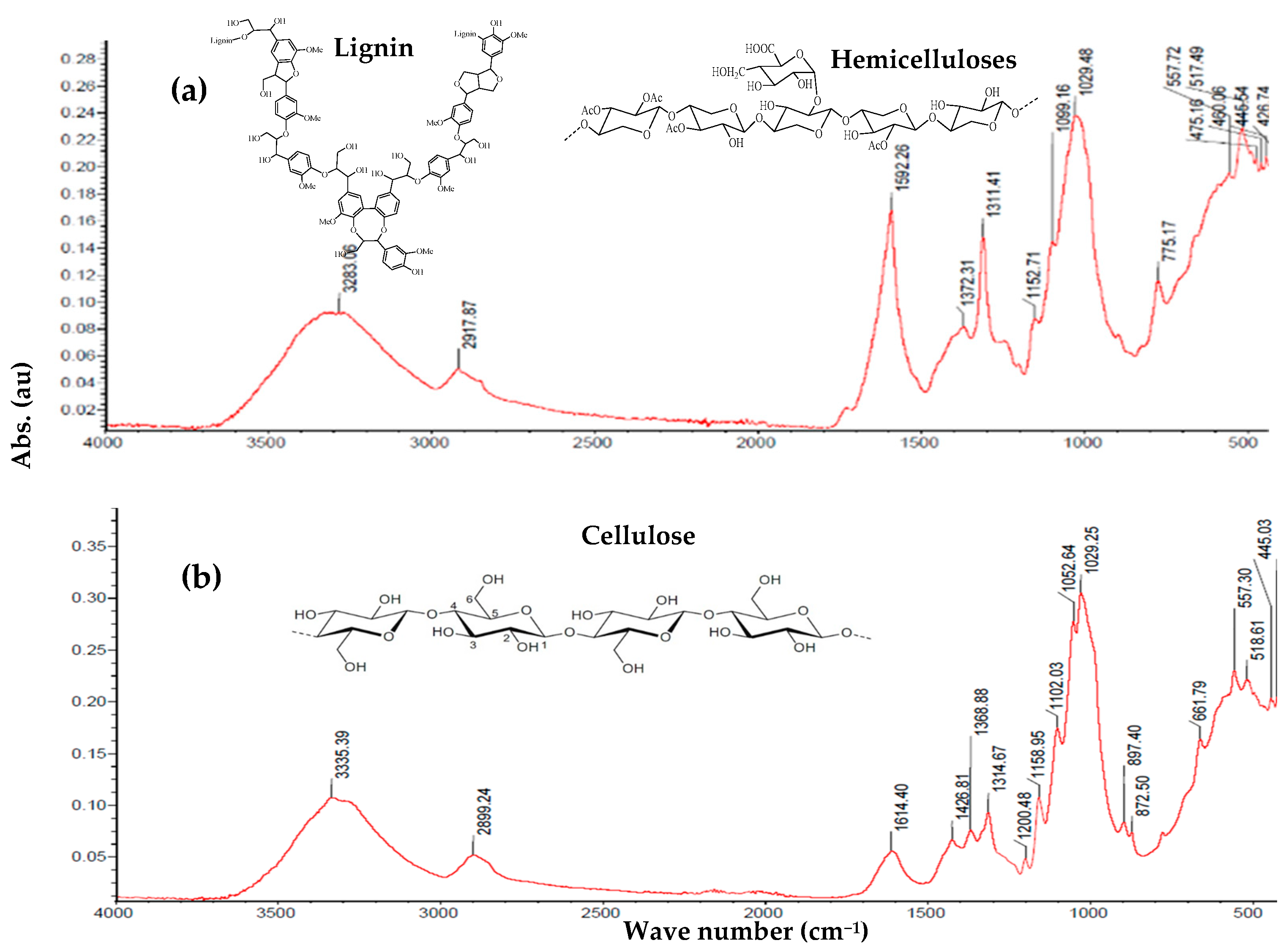

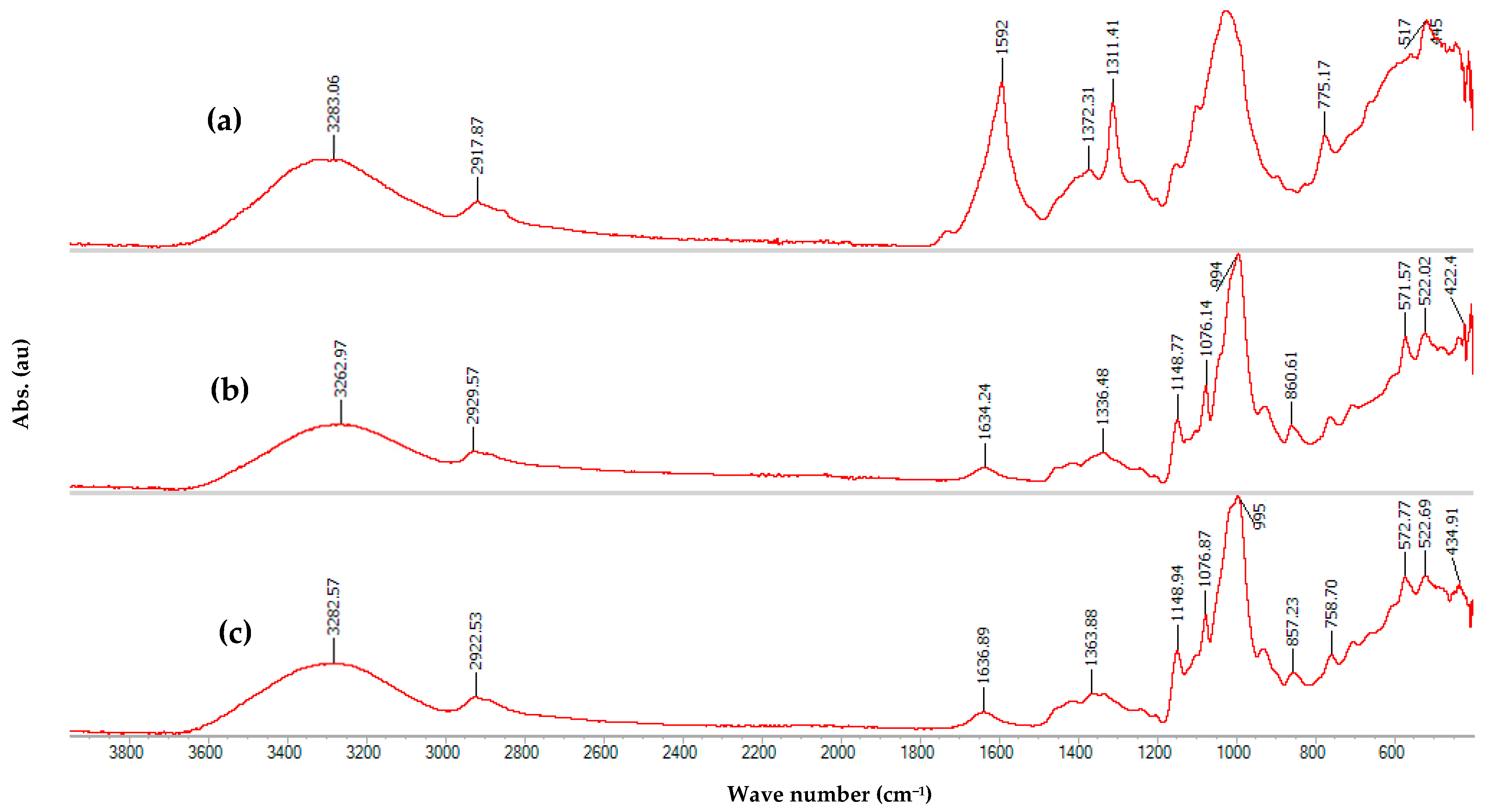

3.2. FTIR

| Absorption Band (cm−1) | Lignin | Cellulose | Hemicellulose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3700–3100 | O-H group stretching vibration | ||

| 3000–2750 | Symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of C-H bonds in CH, CH2, and CH3 groups | ||

| 1770–1700 | C=O stretching vibration in carbonyl and carboxyl groups | No bands | C=O stretching vibrations in acetyl fragments |

| 1605–1490 | Skeletal stretching vibrations of aromatic rings; C=O stretching vibration | No bands | Asymmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate anions |

| 1380–1370 | No bands | Bending vibrations of C-H and O-H | Bending vibrations of C-H in CH3 groups of acyl fragments |

| 1335–1200 | Skeletal vibrations of rings in syringyl and guaiacyl units; asymmetric stretching vibrations between Ar-O-C; stretching vibrations of phenolic C-O. | Bending vibrations of C-H; axial deformation vibrations in C-H of CH2 groups; in-plane bending vibrations of O-H groups. | |

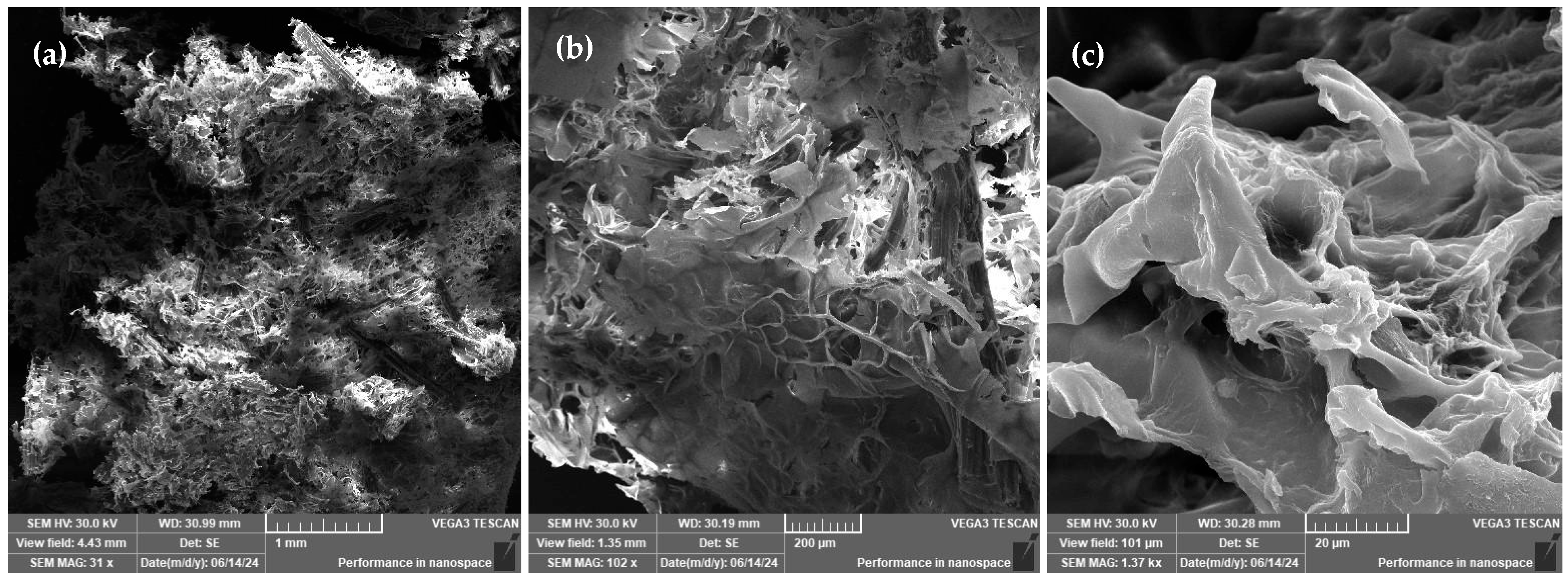

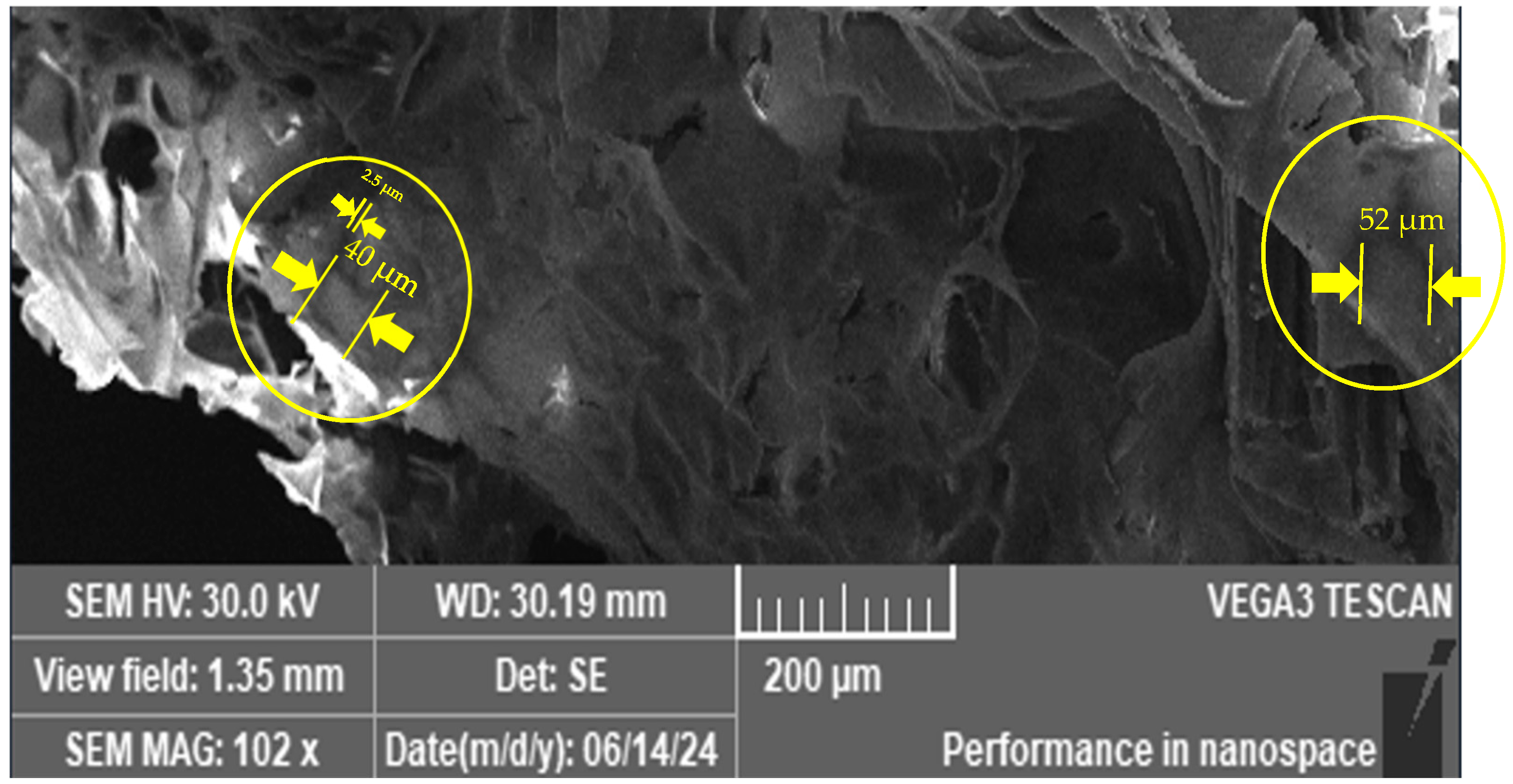

3.3. SEM

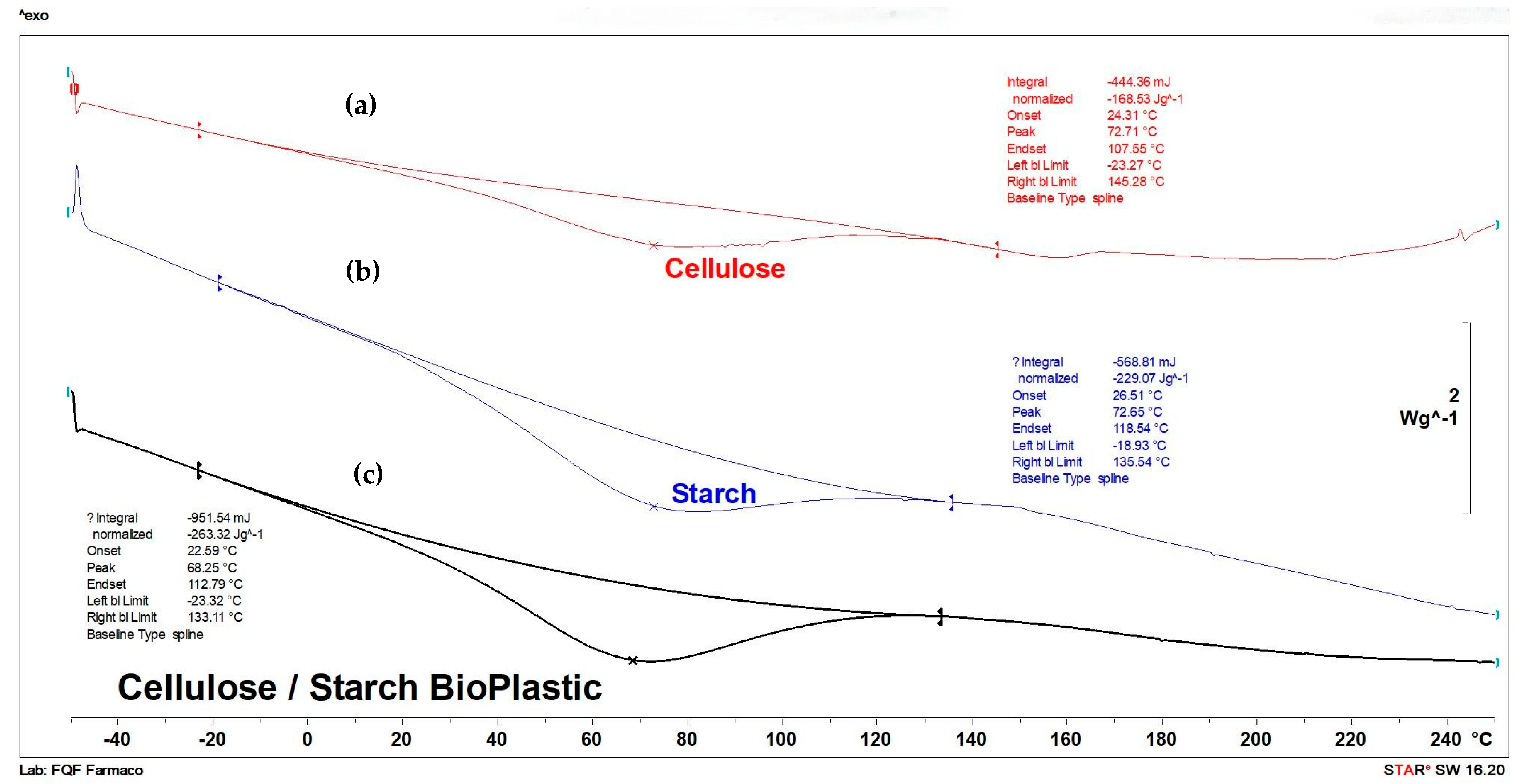

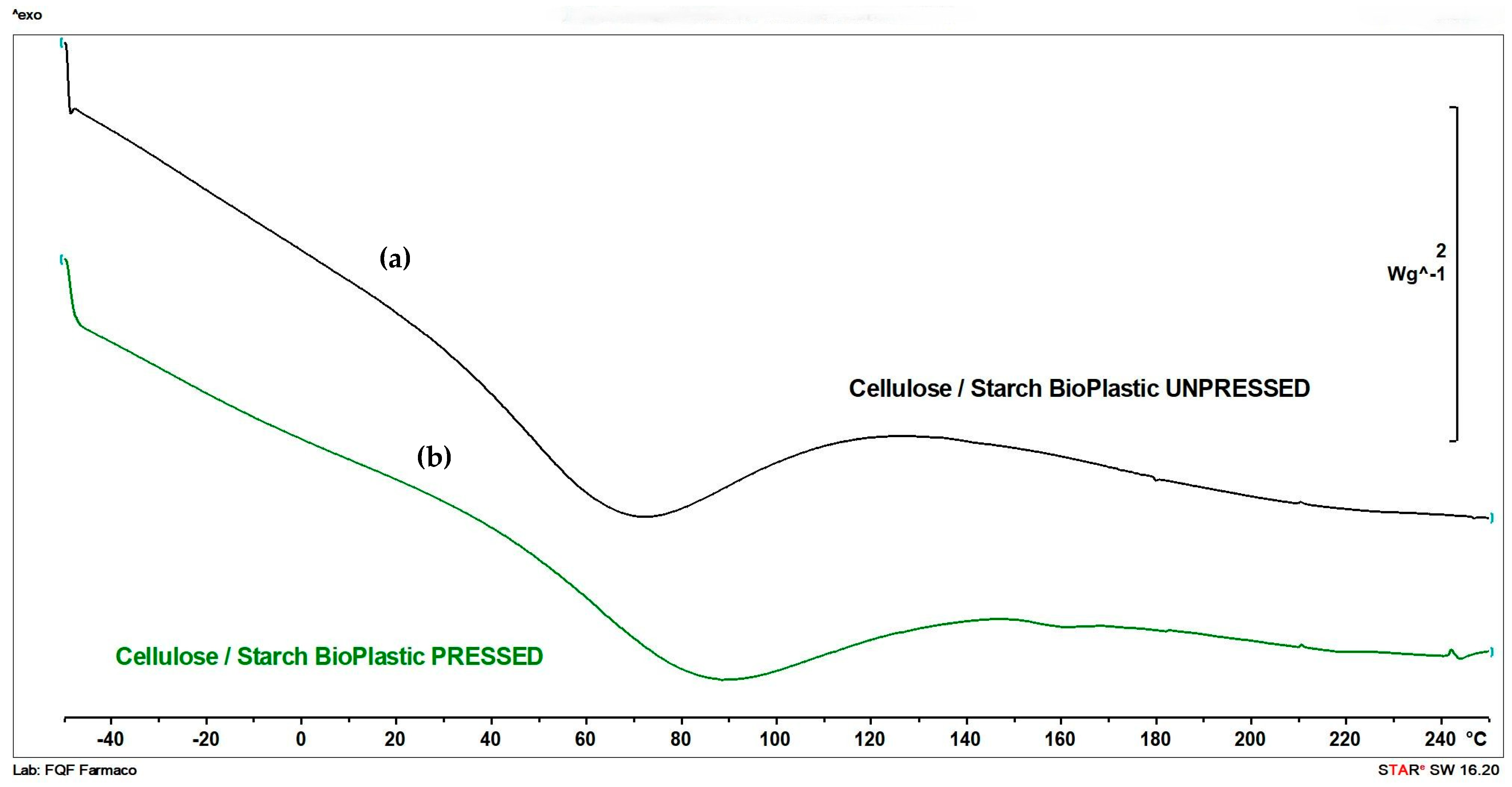

3.4. DSC

3.5. Tensile Strength Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babaremu, K.O.; Okoya, S.A.; Hughes, E.; Tajani, B.; Teidi, D.; Akpan, A.; Idwe, J. Sustainable plastic waste management in a circular economy. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhao, Z.M.; Dong, T.; Anderson, A.; et al. Sustainable bioplastics derived from renewable natural resources for food packaging. Matter 2023, 6, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Gómez, C.; Rodríguez, Q.M.; Vallejo, S.; Murillo, J.P.; Lopretti, M.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Biorefinery of biomass of agro-industrial banana waste to obtain high-value biopolymers. Molecules 2020, 25, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Chakraborty, P.; Janghu, P.; Umesh, M.; Sarojini, S.; Pasrija, R.; Kaur, K.; Lakkaboyana, S.K.; Sagumar, V.; Nandhagopal, M.; et al. Potential of banana based cellulose materials for advanced applications: A review on propierties and technical challenges. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 6, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, G.M.; Modi, R.B.; Prakasha, R. Banana Pseudostem: An Innovative and Sustainable Packaging Material: A Review. J. Package Technol. Res. 2024, 8, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.H.; Joshi, P.V. Banana Nanocellulose Fiber/PVOH Composite Film as Soluble Packinging Material: Preparation and Characterization. J. Package Technol. Res. 2020, 4, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, R.V.; Das, A.; Mahawar, P.A.; Gadekar, P.T. Starch Based Bio-Plastics: The Future of Sustainable Packaging. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2018, 8, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.; Sapuan, S.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Yasim-Anuar, T.A.T.; Kadier, A.; Kalil, M.S.; Atikah, M.; Ibrahim, R.; Asrofi, M.; Abral, H.; et al. Nanocellulose/Starch Biopolymer Nanocomposites: Processing, Manufacturing, and Applications. In Advanced Processing, Properties and Applications of Starch and Other Bio-Based Polymers, 1st ed.; Al-Oqla, F.M., Sapuan, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Zainudin, E.S. Development and characterization of sugar palm nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced sugar palm starch bionanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 202, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abera, W.G.; Kasirajan, R.; Majamo, S.L. Synthesis and characterization of bioplastic film from banana (Musa cavendish species) peel starch blending with banana pseudo-stem cellulosic fiber. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 20419–20440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachcha, I.H.; Paddar, K.; Minar, M.M.; Rahman, L.; Kamrul Hassan, S.M.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Billah, M.T.; Yasmin, S. Development of eco-friendly biofilms by utilizing microcrystalline cellulose extract from banana pseudo-stem. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC International. AOAC International. AOAC Offial Method 962.09. Animal Feed. Fiber (Crude) in Animal Feed and Pet Food. Ceramic Fiber Filter Method. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; Latimer, G., Jr., George, W., Wend, T., Nancy, J., Eds.; Aoac International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D638-22; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Zhang, C.-W.; Li, F.-Y.; Li, J.-F.; Li, Y.-L.; Xu, J.; Xie, Q.; Chen, S.; Guo, A.-F. Novel treatments for compatibility of plant fiber and starch by forming new hydrogen bonds. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostryukov, S.G.; Matyakubov, H.B.; Masterova, Y.Y.; Kozlov, A.S.; Pryanichmikova, M.K.; Pynenkov, A.A.; Khluchina, N.A. Determination of Lignin, Cellulose, and Hemicellulose in Plant Materials by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 78, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gao, J.; Qi, L.; Gao, Q.; Fan, L. Preparation and Properties of Starch-Cellulose Composite Aerogel. Polymers 2023, 15, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasri-Nasrabadi, B.; Behzad, T.; Bagheri, R. Preparation and Characterization of Cellulose Nanofiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Starch Composite. Fibers Polym. 2014, 15, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Christie, G. Measurement of starch thermal transition using differential scanning calorimetry. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 46, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, F.; Dantras, E.; Dandurand, J.; Lacabanne, C. Influence of hydrogen bonds of glass transition and dielectric relaxations of cellulose. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 045403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, H.; Hatakeyama, T. Interaction between water and hydrophilic polymers. Thermochim. Acta 1998, 308, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Hatakeyama, H. Thermal Properties of Cellulose and its Derivatives. In Thermal Propierties of Green Polymers and Biocomposites, 1st ed.; Springer: Utrecht, Netherlands, 2005; pp. 39–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R.C. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press (PhP): London, UK, 2009; p. 888. [Google Scholar]

- Keshk, S.M.A.S.; Al-Sehemi, A.G. New Composite Based on Starch and Mercerized Cellulose. Am. J. Poly. Sci. 2013, 3, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narrazzi, N.M.; Abdullah, N.; Norrahim, M.N.F.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Ahmad, S.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rayung, M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Kuzmin, M. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetric (DSC) of PLA/Cellulose Composite. In Polylactic Acid-Based Nanocellulose and Cellulose Composite, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Paulauskiene, T.; Sirtaute, E.; Tadzijevas, A.; Uebe, J. Mechanical Properties of Cellulose Aerogel Composites with and without Crude Oil Filling. Gels 2024, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, J. Uniaxial tension and tensile creep behavior of EPS. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2008, 15 (Suppl. 1), 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variety | Cellulose Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Williams | 26.99 ± 0.23 |

| Cavendish | 26.66 ± 0.32 |

| Dátil | 25.78 ± 0.18 |

| FHIA-25 | 21.13 ± 0.57 |

| Moroca | 17.07 ± 0.48 |

| Sample | Onset [°C] | Endothermic Transition [°C] | Normalized Enthalpy [ΔH/g] (at Endothermic Transition) | Endset [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | 24.31 | 72.71 | 168.53 | 107.55 |

| Starch | 26.51 | 72.65 | 229.07 | 118.54 |

| Cellulose/starch bioplastic unpressed | 23.77 | 68.91 | 287.31 | 116.45 |

| Cellulose/starch bioplastic pressed | 40.23 | 84.88 | 261.01 | 136.39 |

| Analysis | Units | Sample Pressed Material | Sample Unpressed Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | g | 5.38 | 4.42 |

| Thickness | mm | 1.87 | 8.92 |

| Humidity | % | 10.12 | 11.58 |

| Density | kg/m3 | 638.70 | 110.00 |

| Tension | N | 38.83 | 25.33 |

| Tensile strength | MPa | 0.69 | 0.094 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Servellón, D.A.; Pérez, F.R.; Posada-Granados, E.; López, M.E.; Núñez, M.J. Development of Biodegradable Bioplastic from Banana Pseudostem Cellulose. J 2025, 8, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040046

Servellón DA, Pérez FR, Posada-Granados E, López ME, Núñez MJ. Development of Biodegradable Bioplastic from Banana Pseudostem Cellulose. J. 2025; 8(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleServellón, David A., Fabrizzio R. Pérez, Enrique Posada-Granados, Marlon Enrique López, and Marvin J. Núñez. 2025. "Development of Biodegradable Bioplastic from Banana Pseudostem Cellulose" J 8, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040046

APA StyleServellón, D. A., Pérez, F. R., Posada-Granados, E., López, M. E., & Núñez, M. J. (2025). Development of Biodegradable Bioplastic from Banana Pseudostem Cellulose. J, 8(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040046