Abstract

The discovery of the mortal remains of the apostle Peter in the Vatican caves, in the 1940s, has aroused several doubts among scholars. In any case, there is consensus on this not being Peter’s first burial site on the Vatican Hill. The recent studies on Maria Valtorta’s mystical writings have shown that they contain a lot of data open to check through disparate scientific disciplines. Every time this check has been done, unexpected results have been found, as if her writings contain data not ascribable to her skills and awareness. Maria Valtorta describes also Peter’s first burial site, which, she writes, was not on the Vatican Hill. The analysis of these particular texts, checked against the archeology of Rome in the I century and its catacombs, has allowed us to locate Peter’s first burial site in a hypogeum discovered in 1864 but not yet fully explored, near the beginning of Via Nomentana, in Rome. A mathematical estimate of the probability that Maria Valtorta, by chance, invented the data that lead to this particular site shows that it is very small and reinforces the conclusion, already reached with archeology, that casualness is very doubtful. The full exploration of this hypogeum would assess the reliability of this alleged Peter’s first burial site.

1. Introduction

Recently, a rigorous and scientific analysis of the large literary work written by Maria Valtorta (1897–1961)—an Italian mystic—, on Jesus’ life, has strikingly evidenced the presence of large amount of data concerning facts and events occurred 2000 years ago in the Holy Land, which are well beyond her knowledge and skills [1,2,3]. According to Maria Valtorta, her writings were consequence of mystical visions: she wrote what she saw and heard. In the following, we will refer to what she wrote about her alleged mystical visions as mystical writings (MWs). In her MWs, it is possible to find mentions to localities, roads, river Jordan, lakes, creeks, mountains and hills, sceneries, and monuments of Palestine at Jesus’ times [4,5,6], a geographical area that Maria Valtorta never visited. This large amount of data, however, is practically known only to generations of archeologists, historians, Bible and Talmud scholars, and experts of epigraphy, topography, and geography, whose research has taken them decades of studies and efforts. Therefore, for this reason, it is surprising to find them, with so many details, in her MWs. Moreover, Maria Valtorta writes, during the II World War, sitting on her bed, with her shoulders supported by pillows, bedridden because paraplegic—paralyzed at the waist and legs—, in her house in Viareggio (Tuscany). She had only a Bible and the Catechism of Pius X. But, so far, every time some of the data she reports have been cheeked [1,2,3], they have appeared to be correct, sometimes anticipating what scholars would later have found, e.g., archeologists, as in the following example.

To show with an example how surprising are the data reported in her main literary work concerning Jesus’ life [7], the city of Jezreel is described—[7], vol. 7, 479.4 (The first number (479) gives the chapter, the second number (4) gives its subdivision. These divisions have been introduced by the Editor Emilio Pisani, Centro Editoriale Valtortiano (CEV))—to be of rectangular plan, with four towers at the four corners: «Some towers are at the four corners of Jezreel, but I do not know which purpose they serve. They were already old when I saw them. They look like four gruff giants sited as jailors to the town which is built on an elevation overlooking the plain now slowly disappearing in the early shadows of a cloudy evening». She knew the Bible. In the second Book of Kings (9,17), however, only a single tower of Jezreel is mentioned, not four. The historical age is the IX century BC; therefore, as Maria Valtorta observes, they were already ancient 2000 years ago, period to which her MWs about Jesus’ life refer to [7]. However, neither the Bible nor other possible sources of her times ever mention the presence of four towers, but just one. Moreover, these Jezreel’s archeological remains had not been yet found in the 1940’s. Only in 1987, by chance, a bulldozer discovered some archeological ruins in the southern ridge of the Jezreel Valley, Lower Galilee, and, since 1989, a decade of archeological work in that site started [8,9,10].

The excavations uncovered a casemate wall and four projecting towers, at the corners of a rectangle, surrounding the town-fortress, as Figure 1 shows, built with a combination of well-cut ashlars, boulders and smaller stones, and an upper level of mud-brick. At the times of the Northern Reign of Israel (IX century BC), the site, being elevated 100 m from the valley and surrounded by walls for the entire perimeter () [8,9,10], was of strategic military importance. Maria Valtorta precisely describes the four towers of this site about 40 years before the ruins were ever found [7].

Figure 1.

Aerial photograph of Tel Jezreel, evidencing the rectangular shape of the site, which originally had four towers at the four corners. The zoom in the right-bottom inset shows the ruins of one of the four towers (The photographs shown in Figure 1 have been published in D. Ussishkin. 2011 On Biblical Jerusalem, Megiddo, Jezreel and Lachish, Divinity School of Chung Chi College, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Lung‒kwong Lo ed., Hong Kong), https://www.academia.edu/3175337/On_Biblical_Jerusalem_Megiddo_Jezreel_and_Lachish, last access 10 November 2019).

We cannot offer any rational explanation for this knowledge. What we wish to point out is the objective fact: the comparison between her MWs and what the archeologists have later found is very precise. Moreover, these striking coincidences apply also to many other observations she reports on the Holy Land of 2000 years ago [1,2,3], an interesting and surprising characteristic of her MWs that would deserve careful studies to be further clarified.

This peculiar characteristic of her MWs is important for setting the principal argument of the present paper, namely the localization of St. Peter’s first burial site (In the following, we refer to St. Peter as Peter, for brevity, in the running text, excluding quotations from Maria Valtorta’s writings, as she always refers to him as St. Peter, or when referring to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome), because her writings concern also the first years of the early Church, the apostles and the first martyrs. In her notebooks, in fact, we can read detailed descriptions of catacombs and martyrs, including Peter’s first burial site [11], which she does not set in the caves under St. Peter’s Basilica, in Vatican City. In the following, we will refer to what she writes, about the Peter’s first burial site, as “Valtorta’s hypothesis”. However, it is necessary to underline that—as she writes—all information regarding Peter’s tomb was the result of her mystical visions, because she was not an expert of archaeology and Roman catacombs or history. Mystical visions are beyond the field of investigation of science. Nevertheless, the information conveyed by her alleged mystical visions on historical facts, places and things of real world can be subjected to a verification, through suitable scientific analyses. Under this hypothesis, what Maria Valtorta writes, about Peter’s tomb, can be checked. This is just the aim of the present work.

Let us recall that the works done in the Vatican caves to build the tomb of Pius XI, who died in 1939, conducted to archeological excavations under the floor of St. Peter’s Basilica, which, from 1940 to 1949, uncovered a Roman pagan necropolis with the alleged remains of Peter’s tomb [12]. However, as we will detail below, this was a very controversial finding.

It is curious that Maria Valtorta—who just in those years hoped to have her MWs acknowledged by the Catholic Church as heavenly inspired—was writing that Peter was not buried in the Vatican [11], opposing Church hierarchy’s expectations, who attributed to finding Peter’s tomb and remains the proof of his presence in Rome, therefore ensuring the primacy of the Roman Church. Because Maria Valtorta gives some detailed information regarding Peter’s first burial site, which—she writes—was not in the Vatican, our main scope is to verify what she writes by considering and contrasting archeological and historical data against the detailed descriptions contained in her MWs.

After this Introduction, in Section 2, we summarize the several steps which lead to the discovery of Peter’s alleged tomb and remains, and why they have given rise to much controversy, today unsettled yet. In Section 3, we analyze the correspondence of Maria Valtorta with some prelates on Peter’s tomb at the time of the excavations under St. Peter’s Basilica. In Section 4, we summarize the fundamental data found in her MWs on Peter’s first burial site. Starting from these data, in Section 5, we determine where should be Peter’s first burial site with reference to the maps of Rome in the I century AD. To check the Valtorta’s hypothesis, in Section 6 we discuss the obtained results, grounding them on archeological sources of the XIX and beginning of XX centuries, and also to actual archeological knowledge concerning the catacombs located near the alleged site, and to the structure of Christian burials in Imperial Rome of the I century AD. In Section 7, to check the likelihood of this site, we perform robust Monte Carlo simulations based on data given in her MWs. Finally, in Section 8, we draw some general conclusions.

2. The Controversial Discovery of St. Peter’s Tomb and Remains

Since the time of Emperor Constantine the Roman Church venerates Peter’s burial site in the Vatican. Just beneath the altar in St. Peter’s Basilica, the archeologists found a little monument of the II century, which recalled Peter. In the 1960s, the remains found in the Vatican caves, beneath St. Peter’s Basilica, have been attributed to Peter [12,13].

The monument is a small aedicule, the “trophy” (The word “trophy” originally was a memorial monument of a victory, as Christians considered their death under persecutions) mentioned in a letter of a Roman priest, named Gaius, at the time of Pope Zephyrinus (199–217), who, arguing with someone who claimed to have the tomb of St Philip in Hierapolis, Asia Minor, answers: «I can show the trophies of the Apostles; in fact, if you go to the Vatican hill, or to Via Ostiensis, you will find the trophies of those who founded this Church» (Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia Ecclesiae, 2.25, 5–7).

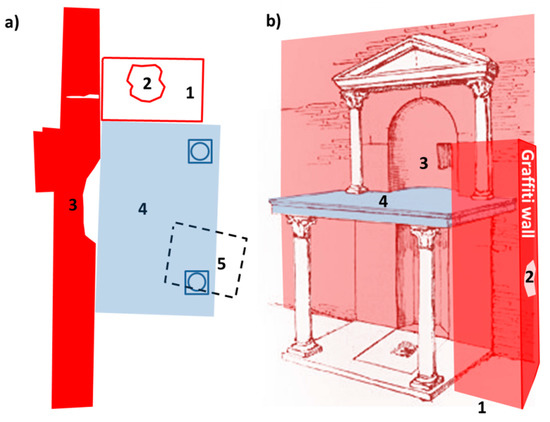

The modest monument was inside a funerary enclosure, called “field P” by the archeologists [12,13]. Field P was full of burial tombs, situated in the bare ground with little or no protection, brought to light during two excavation campaigns in the years 1939–1949 and 1955–1957. The monument was a small aedicule set against the wall of the enclosure, which was covered by red plaster (Red Wall), where two decorative niches, one above the other, extended from the floor, were carved, as to indicate a site particularly important. In Figure 2a, we show a horizontal plan of the site [13], pp. 171; 178 and in Figure 2b a vertical sketch of the aedicule. The niches, given by the curved line in the red wall close to point 3 in Figure 2a (see also Figure 2b), had two little circular columns at the sides, shown as circles inscribed in squares, which held up a slab of travertine (blue rectangle). Some of the tombs in the bare ground are under the little columns. Therefore, some of them can be dated earlier than the Red Wall. Moreover, the niches were included in the Red Wall when it was being built, likely to make a small chapel. It would have been simpler to build it beside the Red Wall instead of indenting it into the wall, therefore indicating, with this effort, the desire of denoting a particular place, considered more sacred than others.

Figure 2.

(a) Plan of the Peter’s Tomb in the Vatican: 1. Prop “wall g”; 2. Cavity inside the “wall g”; 3. Red wall; 4. II century aedicula (Trophy of Gaius); 5. A sepulcher under the floor. (b) Vertical sketch of the Trophy of Gaius (Figure published on BAS Library (Biblical Archaeology Society Online Archive): Finegan, J. The Death and Burial of St. Peter, Biblical Archaeology Review 2, 1976, www.basilibrary.org/biblical-archeology/2/4/2, last access 2 September 2020), with highlighted colors to better show correspondences with panel (a).

The discovery was important because the niches had remained at the center of the Constantinian Basilica of the IV century, and later in the actual Basilica, dedicated to St. Peter, without anyone recalling it was a monument of the II century. Nevertheless, this is one of the most controversial discoveries of the XX century. Let us summarize the main events, happened in the decades just after the end of the excavations, for grasping the reasons of the controversy.

All these findings concern the tomb, not Peter’s remains. The four archeologists of the excavation campaign—namely A. Ferrua, B. M. Apollonj Ghetti, E. Josi, and E. Kirschbaum—concluded they had found the site of Peter’s burial, or at least one of the sites of his burial, because they had not found human remains [12]. In fact, what was beneath the niche had been destroyed in an unknown epoch, and at the site indicated by the Trophy of Gaius, nothing had been left. Therefore, according to the four archeologists, who personally conducted the excavations campaign, the most important question remained unanswered.

A sudden and unexpected fact occurred in the 1960s. After several years investigating Christian graffiti in the area of Peter’s tomb, the epigraphist M. Guarducci, who had not participated in the excavations campaign, announced she had identified Peter’s bones. The modality of the discovery, however, raised many doubts among the experts. A workman who had participated in the excavations campaign would have indicated her a group of bones found during the campaign, but forgotten inside a box in the excavations’ warehouse for more than 10 years, until 1953.

Moreover, among three groups of human skeletons, the anthropologist V. Correnti recognized those belonging to a man aged between 60 and 70 years, 165 cm tall. These human remains could be compatible with Peter’s remains [14,15]. Of course, the following question arises: why the four archeologists of the original campaign did not realize to have found Peter’s remains, a discovery that would have made them famous worldwide?

Besides the anthropological examination that had established sex, probable age and height compatible with skeleton’s remains, and also compatible with Peter’s alleged age and height at his death, all arguments of Guarducci were centered on the site from where the bones had been taken. The site is an irregular cavity in a wall added in a second time to the right of the niche, the so-called “wall g”, shown as point 2 in Figure 2a. This, however, brings the greatest difficulty to the identification. To clarify the problem here raised, let us understand why “wall g” was there. It was built in a year difficult to establish after the aedicule of the II century but before the Constantinian Basilica, which was erected after the year 318. It is a prop wall, necessary after the occurrence of a large crack formed in the “red wall”, which enclosed the cemeterial “field P”. The crack, at about 50 cm to the right of the right column of the aedicule, is sketched in Figure 2a with an irregular white line in the red wall [13], p. 178. This prop wall was added at right angle, exactly in correspondence to the crack in the red wall (Figure 2a). The graffiti studied by Guarducci were all on the extreme side of the “wall g”, not towards the niche (Figure 2a). This is the northern side, oriented precisely to the North [13], p. 178. On the same northern side of the “wall g”, a small irregular cavity was found (point 2 in Figure 2a). The four archeologists had found it empty, but a workman, contacted by Guarducci, would have claimed to have personally taken away some bones before their arrival, after an order by Monsignor L. Kaas, responsible of the “Fabbrica di San Pietro” (Basilica building) during the excavations campaign. These were the bones that Guarducci identified as Peter’s. The story produced a scathing debate between Guarducci and Ferrua [16,17,18,19,20], who did not agree with her conclusions.

After so many years, with all protagonists of the debate now dead, it is clear that the argument is not settled yet. In fact, even if the bones were taken from the cavity in the “wall g”, there is no proof that they belong to Peter. But also another question arises: why the alleged Peter’s bones would have been in this site?

According to Guarducci, the bones were taken away from the original tomb, under the lower niche in the red wall (point 3 in Figure 2), by Christians to save them from persecutions. As already noticed, being a cemeterial area (field P), there were many tombs close to the red wall [13], p. 171, but all displaced from the niche, as shown for one of them in Figure 2a, point 5. Later, during the construction of the Constantinian Basilica, the bones would have been put back in the cavity in “wall g” (point 2 in Figure 2a), before the aedicule and “wall g” were enclosed in the large Constantinian monument on the (alleged) Peter’s tomb. This monument was something like a large box covered by marble, which contained all the aedicule complex but with an opening in front of the niche, while the other structures were demolished. However, during the time elapsed since their removal from the burial site, in the naked ground, and their recollection in “wall g” (point 2 in Figure 2a), it is not known where they had been kept.

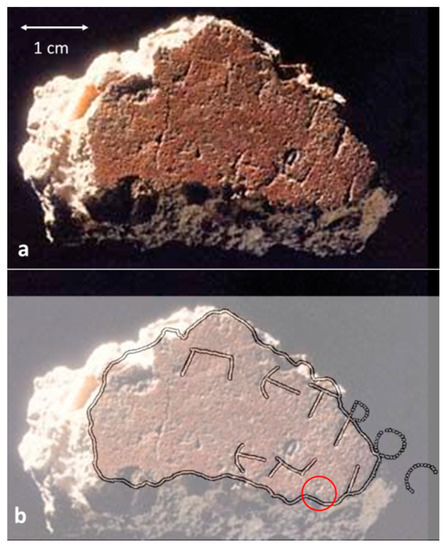

To soften all perplexity, and to prove her discovery, Guarducci declared she had found the proof that they were Peter’s bones in a little fragment of red plaster, found to the right of the niche in the red wall, below the head of “wall g” (Figure 2a), with engraved few letters [13], pp. 172–173. Figure 3 shows a photograph (a) of the little fragment with few letters that supposedly prove the presence of Peter’s remains in the archeological site, and her reconstruction (b) of the full text [21,22], [14], pp. 53–65. She saw the Greek expression “Petr[os] eni”, i.e., “Peter is here”, a kind of proof of his burial, an indirect proof that one of the three skeletons discovered and studied by Correnti, was attributable to Peter. Many epigraphists, however, did not agree with her. In particular, Ferrua proposed “Petr[os] en i[rene]”, i.e., “Peter in peace”, according to the space between some letters, evidenced by the red circle in Figure 3, an acclamation to Peter with the most typical irenical formula of current use since the III century in epigraphic Christian practice [16,18,20].

Figure 3.

(a) Small fragment of plaster with the graffiti proving the presence of the Peter’s relics in the archeological site; (b) interpretation of the graffiti given by M. Guarducci. The red circle highlights a space between some letters or another possible partially visible incision, elements not considered in the interpretation proposed by M. Guarducci, as discussed in the main text.

Given the positioning of the bones, and the fact that for more than ten years nobody had given them any importance, Guarducci’s arguments—they were Peter’s bones—needed a convincing proof. The “authenticity” of the graffiti “Petros eni”, therefore, became of fundamental importance because “wall g” in no ways had been the center of veneration in the Constantinian Basilica.

But Guarducci’s epigraphic proof was very weak so that it was challenged very soon by Ferrua [16,17,18,19,20]. In fact, it would have been really strange that in the IV century, to support the presence of the Chief of the Apostles, there was only a poor graffiti on a small area of the plaster, not a more important epigraph on marble ordered by Constantine himself for the importance of the relics there buried. And, in effect, also the dating of the piece of plaster, today assigned to the first half of the III century [13], p. 172, provoked many disputes.

For the above reasons, the debate continued and involved many famous scholars of different disciplines—history, archeology, epigraphy, classic, and Christian studies—, such as A. Coppo, O. Cullmann, E. Kirschbaum, T. Klauser, H.I. Marrou, A. De Marco, D. W. O’Connor, J. Ruysschaert, J. M. C. Toynbee, and A. von Gerkan [23,24,25]. At the end, Guarducci herself confessed, in her studies, that the piece of plaster was not of the I century but of a later time, more likely of the Constantinian time because the few surviving letters matched also the style of the IV century [14].

This last result exposed her to more criticism because the pilgrim, who would have carved “Peter is here” in the III or even in the IV century, would have done it after several centuries since Peter’s death, and, therefore, the graffiti would have had poor historical value. Consequently, in spite of the solemn radio announcement by Pius XII, 23 December 1950, at the end of the Holy Year (Jubilee), that Peter’s tomb was beneath the Basilica, the debate among scholars continued. The Pope’s announcement was very important for the Catholic Church because in those years many evangelical historians doubted that Peter had ever been in Rome [26,27,28,29,30].

Today, almost no historians, if we exclude very few of protestant area, challenge the presence and death of Peter in Rome [31,32,33]; therefore, certain apologetic urgency of post II-World-War years to establish, with no doubts, that Peter had been in Rome, for supporting the primate of the Roman Church, is no longer felt. It is not a case, therefore, that about twenty years after the Pope’s announcement, at the conclusion of the Year of Faith, called for the XIX anniversary of Peter’s and Paul’s martyrdom, in the hearing held on 26 June 1968, Paul VI wanted to reassert personally the results of the research: «New investigations, most patient and accurate, were subsequently carried out with the results we, comforted by the judgment of qualified, prudent and competent people, believe are positive. The relics of Saint Peter have been identified in a way we believe convincing, and we praise those who have engaged in attentive research and spent long and great effort on it. Research, investigation, discussions, and argument will not thereby end». It has to be noticed the prudential tone of the Pope, given the increasing perplexity among experts. And it is also not a case that Paul VI ordered to write on the reliquary containing nine relics of the bones found in the Vatican caves the following Latin sentence: “B[eati]. Petri ap[ostoli]. esse putantur”, that is “are believed as the bones of the blessed apostle Peter”.

Moreover, the Vatican Hill was very close to the Circus of the Emperor Nero, i.e., the site of the first organized state-sponsored martyrdom of Christians. Therefore, it is difficult to imagine them venerating Peter’s relics kept so close to the Circus. In fact, the plan of the Circus of Nero intersects the plan of the first St. Peter’s Basilica. Therefore, it is reasonable also to suppose that the Trophy of Gaius, found beneath the altar of the actual Basilica, might be a monument to remember the site of Peter’s execution, not his burial. Moreover, after Constantine’s Edict, when the Emperor asked Christians where Peter’s relics were, so that he could build the Basilica, —under the hypothesis that in the IV century Christians still knew the site—, it should have been very dangerous to reveal the real burial site because of alternating emperors favorable to Christians and emperors against them with ferocious persecutions. For example, the emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363), a successor of Constantine, tried to restore the pagan cult in Rome and persecuted Christians.

In any case, it is clear today that, even admitting that Peter’s remains are those found in St. Peter’s Basilica, he was not immediately buried on the Vatican Hill. For example, for J. Carcopino, a scholar contemporary of Guarducci and Ferrua, the loculus in the “wall g” should have been built at the time of Gregory the Great (VI–VII centuries) to collect Peter’s relics, after barbarian sacks [34]. For P. Testini and other scholars, as E. Kirschbaum, the loculus should have contained the skulls of Peter and Paul, after their transfer from Via Appia [35,36,37]. As already mentioned, also for Guarducci Peter’s body was first moved to some other site, before being conserved forever in the loculus of “wall g” [19], p. 277, note 24.

In conclusion, the certainty that the bones found in the Vatican belong to Peter is not ensured. Very likely, the bones, that the archeologists of the excavations campaign considered of no importance, were put in the hollow of “wall g” just during the construction of the Constantinian Basilica, or later. Moreover, the finding of medieval coins in the same hollow [12], [19], p. 276 means that the site was violated in successive epochs, so that there is no guarantee that the bones are 2000 years old. Furthermore, C14 and DNA tests have never been done to assess bones’ historical period and appurtenance to any of the Hebrew haplogroups. In any case, it is not aim of this paper to further discuss this topic, nor to analyze critically previous studies on Peter’s tomb. What we have summarized in this section has the purpose of introducing the reader to the debate on the Peter’s relics developed in the sixties. Indeed, detailed data, about the more accredited hypotheses about Peter’s tomb and remains, can be found either on Christian archeology’s textbooks, such as Reference [12], pp. 164–185, or dedicated works [38,39,40]. Now, after having contextualized the topic in the complex historical background in which it took place, even under the hypothesis that the relics discovered under St. Peter’s Basilica do belong to Peter, where was he first buried?

Let us study what Maria Valtorta writes about. To understand all the possible implications of the Valtorta’s hypothesis, we need to also contextualize her writings in the historical background in which they were produced. Therefore, in the next section, we start our investigation from her correspondence concerning Peter’s tomb that she had in the 1940s, with some prelates, just at the end of the 1939–1949 excavation’s campaign.

3. Maria Valtorta’s Correspondence with Roman Prelates on Peter’s Tomb

Maria Valtorta’s information on Peter’s tomb (The search of Peter’s tomb beneath the altar of St. Peter’s Basilica, and Maria Valtorta’s writings on Peter’s three burial sites, have been proposed in literary form by Antonio Socci with a very readable novel, I giorni della tempesta [The days of tempest], published in 2012 by Rizzoli (Milan). In it, there are ample excerpts of the material reported in Reference [11], before Reference [11] was published) was requested by Father C. M. Berti, professor of Teologia Sacramentaria [Sacramentarian Theology] at Collegio Sant’Alessio in Rome, who, on 11 July 1948, wrote her (All translations from Italian are done by the Authors, including Maria Valtorta’s writings on St. Peter’s tomb [11], not yet available in English): «that priest of [Vatican] Secretariat has prayed me to ask You… where St. Peter’s body is. They have made many excavations, in St. Peter in Rome, but till now they have found nothing… Of course, this is not pleasant. I am expecting an answer. It is sure that also the Work (“Opera”) would benefit a lot…» [11], p. 10. The “Opera” was her main literary work on Jesus’ life, today published in 10 volumes [7]. This letter is important because it clarifies that in 1948, with the excavations’ campaign almost finished, there was yet no clue that beneath St. Peter’s Basilica there were the apostle’s relics, as we have summarized in Section 2.

At the beginning, Maria Valtorta was so much annoyed by Father Berti’s request that, on 14 July 1948, she wrote him: «leave those poor bones in peace!» [11], p. 11. But few weeks later, her MWs contain many details and descriptions just regarding Peter’s tomb. From her correspondence with Father Berti, therefore, it emerges an initial great interest of some Vatican circles to Maria Valtorta’s MWs because, as we have recalled, at the end of the 1940s Peter’s relics had not been found. Let us read what father Berti, just a month later, wrote her—underling the fact that in almost 10 years of excavations nothing had been found—: «In the Vatican Basilica, they have found nothing… Ancient texts make reference to the Cemetery Ostrianum which, really, would be close to Via Nomentana, although nobody has determined till now its exact position. … It is also certain that all the area contained in the triangle that You have drawn is cemeterial. For example, under Villa Torlonia, there was a Jewish cemetery…. And the archeologists admit that in those first beginnings of the Roman Church… the bodies of martyrs were buried also in non-Christian cemeteries. Conclusion: It is acceptable that maybe St. Peter’s body is not in the Vatican or within the walls of ancient Rome…. It is acceptable that also the Cemetery Ostrianum is mentioned. But, because of the great disappointment caused by the excavations, and because the Cemetery Ostrianum is not located with precision, and it is very difficult to locate it as it is in a huge cemeterial area, it would be necessary, for proceeding with the excavations… that You could tell us with the greatest precision the exact point… where to excavate. The Holy Father and everybody in the Vatican are very sad because of the negative results of the excavations in St. Peter…» [11], pp. 23–25. From this letter, we deduce the great interest, at the end of 1948 summer, to some preliminary indications that Maria Valtorta had already given to Father Berti, an issue we will discuss in the next section.

Another important letter dates about a year later (1949). This time A. Carinci, an archbishop member of the Roman Curia—in those years a prefect of the Congregation of Rites—, writes her: «…to the point of your writings, You were telling me You know where St. Peter’s body rests. Because right now a report is being written on the excavations conducted in the Vatican Caves beneath the central altar, I would ask You to communicate to the Holy Father what You know: very willingly I would present to the Holy Father Your writing, which would cast some light on this important issue for all Christianity» [11], p. 42. The first of October of the same year (1949) Maria Valtorta answers by writing that: «On 5 February, with much insistence and mentioning, among many others, the names of Excellencies and Monsignori and other important Priests, …, Father Berti persuaded me to give him a “quinterno” (Five sheets of paper folded in two) where I wrote the successive transfers of the relics of the first Pope-Martyr; he also made me write a letter to the Holy father, whose trace he wrote for me, which I still have. Letter and quinterno were supposed to be handed to the Holy Father… On 7 February, I mailed the letter, which was delivered the 9 or 10 of February together with the quinterno, and 5 days later the Work [Opera] was stopped… I ask: the letter and the quinterno were really handed to the Holy father, and without changes done by someone? If yes, I cannot say more than what I have already said…» [11], pp. 42–44.

The Work (Opera), to which she refers, is her main literary work [7], which at the time had not been yet published. Its diffusion and publication was preventively stopped by someone belonging to the Roman Curia. Its publication would have required the ecclesiastic permission of the Catholic Church, called “imprimatur”. Maria Valtorta would never have allowed the publication of her Work without the imprimatur of the Catholic Church, as she explicitly stated many times in her writings. Nevertheless, few years later, since 1956, her main work was published without imprimatur, with a title different from the current one (The first title was “The Poem of the Man–God”). In those years, Maria Valtorta had already become fully estranged from active life, living the final years of her existence in a sort of lethargic state, without any social interaction with other people. The imprimatur of the Catholic Church was never granted. Rather, the Sant’Uffizio (Holy Office), the authority of the Roman Curia appointed to promote and defend the doctrine of the Catholic Church, in 1959, officially included her MWs in the Index of prohibited books, i.e., books that Catholics were not supposed to read (The Index of prohibited books was abolished in 1966 by Paul VI).

We have briefly recalled these facts and Maria Valtorta’s correspondence with some Vatican prelates just to show that her writings about Peter’s burial site were not at all conditioned by her willing to publish the Work with the ecclesiastic imprimatur. She did not indicate, because she did not really know, the exact site of Peter’s tomb. Nevertheless, she did not indicate Peter’s burial site in the Vatican caves just to ingratiate herself with the Roman Curia and thus get her MWs accepted as divine inspired. All these vicissitudes do show, in fact, just the opposite situation: her moral integrity and her willing not to compromise on what she had written because received, as she claims, in mystical visions.

In the next section, we examine the writings to which Father Berti refers to, in particular, the descriptions of Peter’s first burial site, according to the Maria Valtorta’s hypothesis.

4. Peter’s First Burial Site According to Maria Valtorta

According to the Maria Valtorta’s hypothesis, in agreement with most historical sources, the Vatican Hill (Now, it does not appear as a “hill” because the hill was leveled by Emperor Constantine to build the Basilica) should be the site of Peter’s martyrdom not the site of his first (or unique) tomb. As discussed in Section 2, there is a consensus among scholars that the Vatican is certainly not the site of his first burial. In this section, we summarize what Maria Valtorta writes about this point (These excerpts from Reference [11] fulfill two purposes: (a) read directly what she writes about Peter’s burial without interpretations; (b) provide the English translation for a worldwide audience until the CEV full English version of Reference [11], now underway (private communication of the Editor Emilio Pisani), will be available).

On 25 July 1948, she writes: «Are they sure that he [St. Peter] is buried in the Vatican? Among pagans, in a filthy site, and at the mercy of pagans?» [11], p. 13. On 27 August 1948: «And at fallen night the Christians removed the body from there and took it to the first Christian Cemetery which was the Ostrianum, where Peter had evangelized, in the first catacomb excavated in Rome to gather Christians, teach them, baptize them and officiate the other sacraments» [11], p. 13. On 1 August 1948, it is added: «Remember that there was the Ostrianum for the martyrs» [11], p. 13 and on 7 August 1948: «St. Peter evangelized at the Ostrianum and there he had his chair» [11], p. 13. In other words, according to Maria Valtorta’s MWs, Peter’s first burial site should be in the area of the Cemetery Ostrianum.

According to the experts of Christian archeology, the oldest nuclei of Roman catacombs date to the end of the II century. At the beginnings, in Rome, the Christian cemeteries were certainly underground but, originally, they were family tombs, protected by the Roman law which respected any tomb as a religious site. Therefore, before the year 67, when the Reign of Nero ended—Nero’s persecutions caused Peter’s death—the systematic use of the underground in shaping the elaborated catacombs we know today was not yet developed [41,42,43,44]. In spite of this, the Cemetery Ostrianum is remembered by some ancient sources as Peter’s first chair. At the end of the XIX century, G. B. De Rossi located the Ostrianum as the Coemeterium Maius, along Via Nomentana [45]. According to De Rossi, who based his research on documents of the V–VI centuries (The oldest sources are Acta Liberii et Damasi of the year 501 and Passio Sisinni of the V century inserted into Gesta Marcelli), the designation maius was justified not because it was the largest cemetery—it was not—but because it was the most important as Peter baptized there: «ubi Petrus apostolus baptizavit».

O. Marucchi confuted De Rossi and localized Peter’s chair in the Cemetery of Priscilla, along via Salaria [46]. Up to today, the problem is not yet solved [47]. In favor of Via Nomentana, it is possible to cite Passio Papiae et Mauri, in which it is said that the two martyrs were buried at nymphas sancti Petri, ubi baptizavit (near the spring where Peter baptized). The martyrs Papia and Maurus are buried just in Coemeterium Maius, which is along Via Nomentana. In addition, the Mirabilia urbis Romae, in listing the Roman cemeteries, mentions the cimiterium fontis sancti Petri (the cemetery of St. Peter’s spring) after the cemetery of St. Agnes, along Via Nomentana, before that of Priscilla, which is along Via Salaria, although the archeological exploration of Coemeterium Maius, in the 1960s, seems to indicate that it developed in extension only during the III century [48]. Some scholars think that a large cemeterial area developed on both sides of the beginning of Via Nomentana, and not only for burying Christians [49]. Therefore, it is not easy to locate the original nucleus of the Ostrianum in the I century, and this is confirmed by Father Berti’s words reported in Section 3.

In conclusion, an ancient tradition localizes Peter’s chair in a cemetery North-East of ancient Rome. Some think it was along Via Nomentana, others think it was along Via Salaria. In the I century, catacombs were not very deep and extended, as they were later, especially since the III century. According to sources of the V century, the cemetery Ostrianum, site of Peter’s chair, had certainly access to an underground spring, necessary for baptizing people. But it was not very extended in the I century, because both pagan and Christian cemeteries in Rome, at their beginning, had often only a family use with a hypogeum or a semi-hypogeum, that is an underground space excavated in family grounds, outside the city walls, because burials were prohibited within the city [41,42,43,44]. Only later the cemeteries extended with a network of underground tunnels: «the starting point, for extending a cemetery, was almost always a family tomb, around which the network expanded, because the [Christian] owner wished to offer burial to the poor of the neighborhood. Their development was proportional to the increasing number of Christians. This is the origin of the main Christian cemeteries of the I and II centuries» [50], pp. 40–41.

Maria Valtorta explicitly mention the Ostrianum. She writes that Peter was buried and moved three times for avoiding that his body were desecrated [11]. The first burial site, which is the one we wish to investigate in this paper, should therefore be in the cemeterial area of the Ostrianum, but, as we have just recalled, in the I century the Ostrianum was not so much extended; therefore, we should expect that Peter’s first burial should not belong to any of the large Roman catacombs.

Let us read now the main information that Maria Valtorta writes on the first burial site, the target of our investigation.

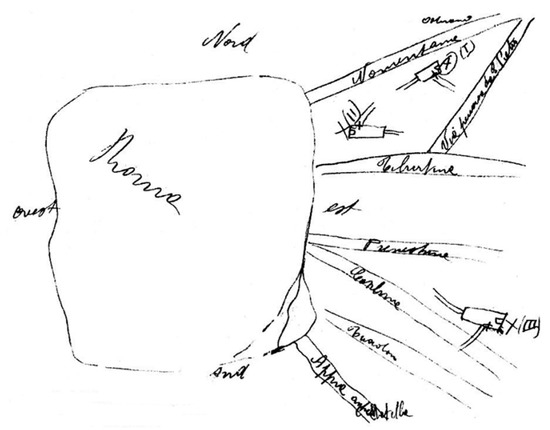

On 26 August 1948, she writes that Peter walks along a secondary road that joins two consular roads: «I see two men moving from South-East to North-East along a rural road that joins two consular roads, with the typical Roman paving of square stones. Other roads are further away and make a wheel like an open fan with ancient Via Appia (see sketch)». She refers to the sketch reported in Figure 4 (On 21 September 1948, in a letter to Father Berti, she confesses that: «I have always been criticized for the poor clarity of my topographic scketches attached to the Work, and rightly, because I know nothing about topography and cartography» ([11], p. 28). Nevertheless, as we will see, she denotes correct distances and orientations in her writings, as we have found by testing her topographic data on Peter’s walk along the rural road beween Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana).

Figure 4.

Sketch of the map drawn by Maria Valtorta on 26 August 1948 about three different Peter’s burial sites, referred to the Roman walls [11], p. 14. On the map, she indicates the four Cardinal points and, from North to South: Ostriano, Nomentana, path traveled by Peter, Tiburtina, Prenestina, Casilina, Tuscolana, Appia Antica-Metella.

After the sketch, the description continues: «I recognize to be East of Rome because the last road I see, in the South direction, Via Appia, has the sepulcher of Caecilia Metella. Therefore, it is Via Appia. The two men go, instead, along the rural road, like a shortcut, stony, with some tufts of grass, traced by human steps among desert and uncultivated fields. The city is few hundred meters far-away, but the small [rural] road gets further and further away as it leads North to the other consular road. The two are a young man (30–35 years) … The other is an old man (75–80 years), … My inner admonisher [her guardian angel] tells me: “Venerate the Apostle Peter”. … St. Peter stops and looks at me when he is at about two thirds of the [rural] road. He lets his companion proceed. But he, St. Peter, goes down the uncultivated field which is to the left of who proceeds North, walks diagonally about 100, 150 m. He stops. He stares at me as if he wanted to attract my attention. Then he hits three times the ground with his stick, among weeds. He passes the stick to the left, he waves to greet me and, cutting again diagonally the field, goes back to the rural road and reaches the companion, who has stopped, waiting for him, near the consular road at North. He joins him, they walk some few tens of meters on it, and when they are far from the city, I would say about a kilometer, more or less, they go down in other uncultivated fields North of the [consular] road. I would say that the ground goes downward because I see them disappearing little by little as if they were walking down a slope. They go always to the North-East direction, but at an angle with the consular road. They disappear completely behind a clump of small trees. …The site where they have disappeared is at least at one and a half kilometer from the Gate where the consular road starts, if I calculate correctly» [11], pp. 13–16.

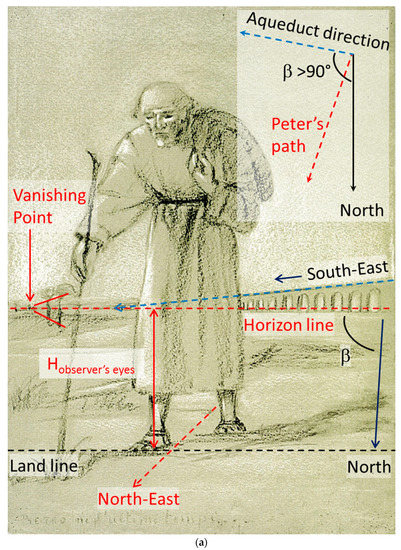

On 29 August 1948, Maria Valtorta identifies the consular roads: «…my inner admonisher tells me the name of the two consular roads connected by the small [rural] road. The most southern one is Via Tiburtina and near it there are arches of an aqueduct. The most northern one, on which St. Peter walked before going down in the [uncultivated] field and then disappearing is Via Nomentana» [11], p. 17. The artist L. Ferri, under Maria Valtorta’s guidance, draws Peter walking towards North-East, along the rural road, very likely at the beginning of the walk, because there is visible an aqueduct behind him, as shown in Figure 5a [11], p. 12 (All drawings done by L. Ferri, under Maria Valtorta’s guidance, are published in Valtorta and Ferri, CEV, Isola del Liri (Fr), Italy, 2006). Notice that the aqueduct seems to be directed almost orthogonally to the Peter’s walking towards the North-East direction, as its arches become less high moving away from Peter’s left side. We have clarified this point in a plan view of the scene represented by Ferri, in the upper-right insert of Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

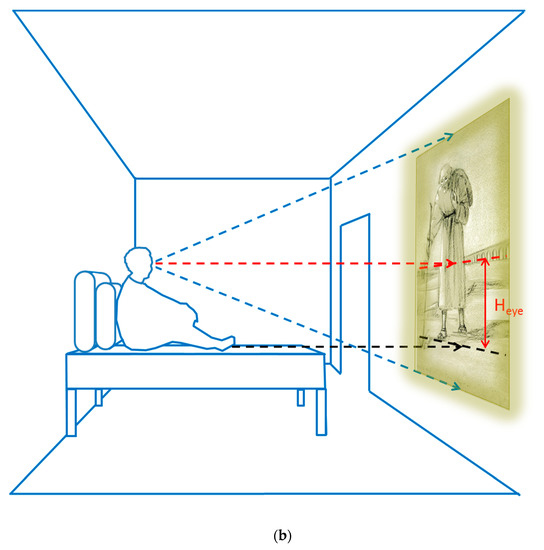

(a) (Upper panel): Peter’s portrait drawn by L. Ferri, under Maria Valtorta’s guidance, in which Peter is walking on the rural road, between the two Roman consular roads (Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana). He moves North-East, with an aqueduct visible behind him, directed almost orthogonally to his walking path [11], p. 12. (b) (Lower panel): Sketch of Maria Valtorta’s bedroom, while she is “seeing” Peter going from the via Tiburtina to via Nomentana, along the rural road, as it can be evinced by the perspective analysis of the L. Ferri’s drawing.

An analysis of the perspective of the drawing allows us to individuate only one vanishing point; therefore, it is not sufficient for calculating Peter’s distance from the aqueduct (two vanishing points are needed). With respect to the direction North-South of the observer of the scene, the aqueduct forms an angle larger than 90°—β in Figure 5a—because its ending part—see the dashed blue line—does not coincide with the vanishing point. Therefore, the aqueduct depicted behind Peter is directed towards South-East, forming a slightly obtuse angle () with the North-South direction. Finally, let us note that the height of the eyes of the observer of the scene—given by the height of the horizon line with respect to the land line—is quite low, at the level of Peter’s knees. This finding implies that Ferri has drawn, and/or Maria Valtorta has described the scene, as seen from below—like looking at an elevated screen—, likely because she was bedridden, as it is sketched in Figure 5b. Indeed, we must always consider that, according to what she writes, all information about Peter’s tomb (Valtorta’s hypothesis), which are under a critical analysis in this work, should be the result of alleged mystical visions. This finding emerges also by the perspective analysis of the L. Ferri’s drawing as sketched in Figure 5b, where Maria Valtorta, bedridden in her small bedroom is depicted while “seeing” Peter walking, as she were in front of a big screen: the height of the eyes of the observer of the scene, , is at the level of Peter’s knees.

On 21 September, she explains that the above description regards Peter’s first burial site: «I have not had indication on where St. Peter is now buried, but where the body of the First Pope was taken in the night following His Martyrdom … If God will want, He will complete the information. By now He has condescended to let us know where, after the martyrdom, the body of St. Peter was taken and the area where he was laid» [11], pp. 26–27.

On 19 September, she clarifies that it is part of the Cemetery Ostrianum: «St. Peter dressed with pontifical robes (but without miter) as he was laid down, but with the pastoral in his hands and with the beauty of the Blessed, appears to me in the same site where he hit the ground. Then I see the entrance to Ostrianum. It is done as a horseshoe with the entrance to North-West. It is at the end of a basin or valley, and it seems one of the terraces present in olive groves in hills. It is semi-hidden by a tangle of brambles and other small wild trees. The entrance goes down the ground very soon. I have not entered. In this natural amphitheater are scattered piles of debris, stones, sand, emerging or disappearing under…tangles of brambles. Only a path is kept clean, all curved to keep it hidden to people who look from Via Nomentana. The entrance to Ostrianum, then, is all covered with bushes falling from a terrace. The small trees I saw on 26–8, and behind which St. Peter disappeared, are at the beginning of the horseshoe, acting as a curtain» [11], p. 22.

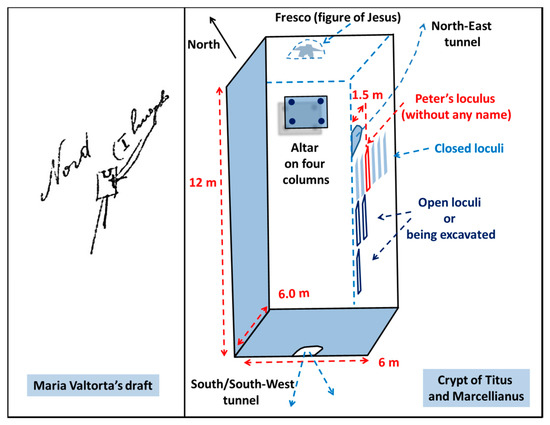

On 18 September 1948, she writes that Peter’s body is hidden in a catacomb which has no reference to him, in a crypt dedicated to two other martyrs: «My inner admonisher tells me: “This is the catacomb crypt of the martyrs Titus and Marcellianus, the first [martyrs] laid down here. He rested here with them”» [11], p. 18.

On 3 October 1948, she writes that Jesus had told her that this was done for the «necessity to confound traces and hide the relics» [11], p. 29. The alleged Jesus, later, explains to her: «as centuries have passed the name of Marcellianus changed into Marcellinus, for a mistake of whom who engraved the II tomb stone of Marcellianus (who was with St. Peter in the rural road… my [Maria Valtorta’s] note: I know because Jesus shows him to me again» [11], p. 29.

In summary, Maria Valtorta describes Peter walking along a secondary rural road that connects two consular roads, Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana. The rural road starts few hundred meters from the city walls, close to an aqueduct, directed almost perpendicularly to the rural road, as drawn in Figure 5. Walking North-East, at of the line-of-sight between the two consular roads, the Apostle proceeds to the left diagonally for about 100–150 m and hits the ground with a stick to indicate the site of his first burial. Arrived at Via Nomentana, at about 1 km from the Gate from which Via Nomentana starts, after walking few tens of meters, he leaves the consular road, but always walking North-East near Via Nomentana. The ground is descendant. At least at 1.5 km from the Gate from which Via Nomentana starts, Peter disappears because walking downhill, directed to the entrance of Ostrianum.

Peter’s first burial site is described with many details. It is in the crypt of the martyrs Titus and Marcellianus. We know nothing, however, about two martyrs of the I century with these names buried together [51,52]. Therefore, it is not possible to locate immediately the burial site. We can suppose that it is either a crypt not yet discovered, or a literary invention of Maria Valtorta. However, if it was a real site, being a cemetery of the I century, and one of the first ones in Rome, very likely at the beginning it was a family cemetery, of modest extension, developed around an initial family hypogeum. Peter’s body is described hidden in this crypt, without any direct reference to him, for fear that his relics might be profaned.

In conclusion, in Maria Valtorta’s MWs, before the end of August 1948, we find a series of data on distances which can be studied and checked with reference to the maps of the Rome of the I century, established by archeologists, after long-lasting excavation campaigns, and by experts of Christian archeology. In this way it is possible to assess whether the Valtorta’s hypothesis is just a literary text originated from her narrative fantasy, or corresponds to a real archaeological site. The results of this analysis are presented in the next section.

5. Peter’s Walk Checked against the Map of Rome of the I Century

To perform an accurate analysis on the distances and topological information given by Maria Valtorta, recalled in Section 4, we must refer to the map of imperial Rome shown in Figure 6. We have been able to draw Figure 6, thanks to the painstaking and accurate work done by R. Lanciani [53], who a century ago drew 46 large maps, with scale (), of the city of Rome, with indicated all main archeological sites [54]. These maps are available online (https://rometheimperialfora19952010.wordpress.com/2014/08/18/roma-archeologia-e-restauro-architettura-roma-carta-archeologica-rodolfo-lanciani-la-forma-urbis-romae-roma-milano-1893-1901-46-grandi-tavole-in-scala-11000-in-pdf-2014-2008/, last access: 21 June 2020).

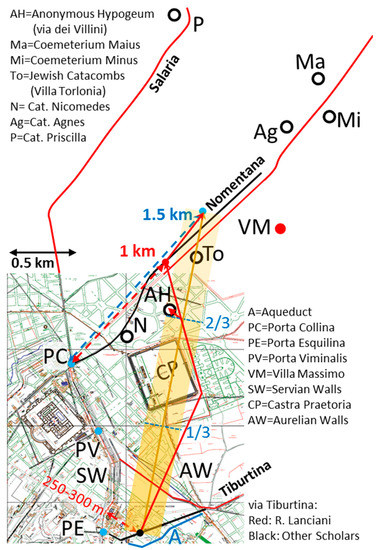

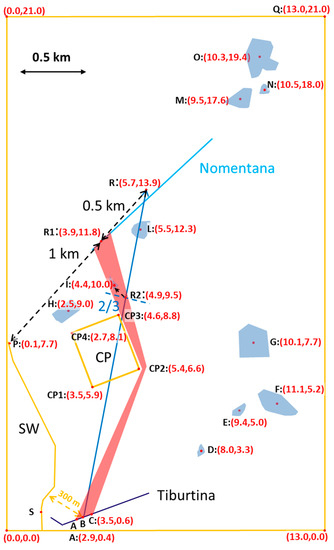

Figure 6.

Map of Rome drawn by Lanciani [54], with the main archaeological sites. The red line ending with an arrow represents the rural road described by Maria Valtorta, which connects Via Tiburtina to Via Nomentana. The black circles indicate the main catacombs near the two consular roads. In black, the path of the ancient Via Nomentana, different from the current one (in red). The red and blue dashed lines represent the distances indicated by Maria Valtorta: 1.0 km when Peter reaches the consular road; 1.5 km when he disappears from view for the downhill path a little further North of the consular road. It is also shown the aqueduct (blue lines) which flows south of Via Tiburtina, exiting from Porta Esquilina. The dark yellow band indicates the line-of-sight distance between the begin and the end of Peter’s path. At 2/3 of this band, a small red arrow indicates the detour path (100–150 m) leading to the point where Peter hits his stick to the ground, Peter’s first burial site according to Maria Valtorta’s MWs.

The historical period of the archaeological ruins shown in these maps is indicated by the color: black corresponds to the imperial age, green to the urban development that was underway at the beginning of the XX century. Because some changes to the City Plan were made during the construction of new roads at the beginning of the XX century, sometimes these maps are not accurate in comparing the position of the archaeological remains with the current city layout. Nevertheless, as we are only interested to distances that are always greater than few tens of meters, the local approximations sometimes found in these maps in locating the archaeological sites can be neglected.

Being in the I century, the walls of Rome to which we must refer, to be correctly oriented by Maria Valtorta’s indications, are those built by Servius Tullius, the Servian Walls. The Aurelian Walls were built in the III century. In Figure 6, we have shown only the area between Via Tiburtuna and Via Nomentana.

The path of the ancient Via Nomentana (Nomentana Antiqua, I century) is drawn in black to distinguish it from the modern path, shown in red. For the path of the ancient Via Tiburtina exiting from the Servian Walls of the I century, different hypotheses have been formulated [55]. According to some scholars the consular road originally started at Porta Viminalis. For example, Lanciani proposed that Via Tiburtina was first directed South-East, in the region of the city between the Servian and the Aurelian Walls, and then turned to North-East, outwards of the Aurelian Walls, therefore forming a wide curve (red color in Figure 6), and, in this way, he traced the road in his maps [54]. However, today, almost all scholars agree on the conclusion that most likely in the I century Via Tiburtina started at Porta Esquilina, with a fairly straight path, headed towards the future Porta Tiburtina (black color in Figure 6) [55]. On this point, Maria Valtorta writes: «I saw the Tiburtina almost straight (North-East direction) in the immediate vicinity of the city» [11], pp. 25–26. Let us note that Via Tiburtina exiting from Porta Viminalis is directed towards South-East. Consequently, in our analyses, we will refer only to the path of Via Tiburtina starting at Porta Esquilina which, after about 100 m from the city walls is directed just towards North-East (see Figure 6).

The catacombs shown in Figure 6, close to the two consular roads, are those indicated in Reference [41]. In Figure 6, we have highlighted with a red arrow a possible path that, from Via Tiburtina, near the aqueduct closest to the Servian Walls, would have led to Via Nomentana. The starting point of the path described by Valtorta was located at about m from the Servian Walls, because she writes that the city was few hundred meters far away. From the reconstruction shown in Figure 6, we deduce that, if the rural road starts at few hundred meters from the Servian Walls, near Porta Esquilina, there is an aqueduct—Aqua Iulia—a little further South of Via Tiburtina, indicated with A in Figure 6, and highlighted with the blue color in Lanciani’s map, with the first part just directed towards South-East—as drawn by Ferri under Maria Valtorta’s guidance (see Figure 5a). Thus, imagining to observe the scene of Peter walking along the rural road towards North-East, by looking at the scene from North towards South, we would see the first part of the Aqua Iulia disappearing at the horizon, on the right side of Peter’s shoulders, just as drawn by Ferri (Figure 5a).

The terrain of Rome is made of tuffaceous hills deeply eroded by water. The construction of modern buildings has almost filled the deep ditches in-between the hills, and modified the natural shape of the sites to such a degree that it is difficult today to imagine the appearance of the area in ancient times. Nevertheless, the altitude of the area, deduced from old Town Plans, such as, for example, that of 1883 [56], does provide some elements less affected by XX century urbanization. Walking from South-East towards North-East, the downward slope increases after crossing Via Nomentana and continuing parallel to it heading towards St. Agnes’ catacombs. This topographic element agrees with what Maria Valtorta describes: Peter and the disciple disappear after crossing Via Nomentana while walking down-hill to the North-East direction at a distance of about 1.5 km from the consular road’s Gate (Porta Collina) [11], p. 16.

The crossing point of the rural road and Via Nomentana is set on Via Nomentana Antiqua, at 1.0 km from Porta Collina, as described by Maria Valtorta. Indeed, the path that the consular road had in the I century (black line) is different from the modern path (red line); in the I century Via Nomentana exits from the Servian Walls at Porta Collina. Later, in the III century, this Gate was replaced by two new Gates built in the Aurelian Walls, East of the Servian Walls: Porta Salaria, which is still where it was built, and Porta Nomentana, also called Porta di Santa Agnese (St. Agnes’ Gate) in the Middle Age. This latter Gate was later replaced, under Pius IV (1559–1565), with Porta Pia, which is located a little North—leaving Rome—of the ancient Porta Nomentana, today bricked up [57]. In fact, the beginning of the actual Via Nomentana, near the Aurelian Walls, is not perfectly lined up with the road of Imperial times [58], p. 104. Just outside the Servian Walls it had a small deviation (black line in Figure 6), which took it to almost touch Castra Praetoria, already built in the I century. For this reason Porta Nomentana, now bricked up, is further South-East of the actual starting of Via Nomentana. The enclosure of Castra Praetoria was about rectangular with sides , indicated with black continuous line in Figure 6.

Notice that in her sketch of the consular roads leaving Rome in the East direction (Figure 4) Maria Valtorta does not show the details of the starting of the consular roads (e.g., the initial curve of Via Nomentana Antiqua). Neither she mentioned Castra Praetoria nor drew it, but she just traces straight parallel double lines to indicate the general direction, also for the rural road connecting Via Tiburtina to Via Nomenatana. She describes exclusively the starting and ending parts of the rural road between the two consular roads. Nothing is described in between the path, except the point where Peter hits the stick to the ground, at about 2/3 of the line-of-sight. Therefore, we could also infer that in Figure 4 Maria Valtorta has simply drawn a straight line—to indicate the rural road—between the two consular roads and set, at 2/3 of its length, Peter’s first burial site, evidently not in scale with respect to the consular roads and the whole map. With no further topographic details available to her, she summarized in the sketch, coherently, only what she had described.

The red and blue dashed lines in Figure 6 represent the distances indicated by Maria Valtorta: 1.0 km when Peter reaches the consular road; 1.5 km when he disappears from view for the downhill path a little further North of the consular road. The dark yellow band indicates the whole distance between the begin and the end of Peter’s path, until he disappears to the view beyond Via Nomentana. At 2/3 of this band, a dashed blue line intersects Peter’s path (red segments), started from Via Tiburtina and ended in Via Nomentana, at 1 km from the city. A small red arrow in Figure 6 indicates the detour path (), which ends just on the area of the so-called Anonymous Hypogeum.

As we have already noticed, she never mentions Castra Praetoria, a “missing datum” in her writings. Most likely Maria Valtorta had looked at (see Section 8) one of the common maps of the ancient Rome showing the city surrounded by the Aurelian Walls, visible also in Figure 6, which in the III century included Castra Praetoria. Thus, very likely, Maria Valtorta was unaware of the existence of the Castra Praetoria as a separate huge building in the I century. Therefore, the two distances reported in her description—about 1 km from the city and about 1.5 km from the consular road’s Gate—are coherent if Peter’s path is broken in two segments not aligned, the first from Via Tiburtina to the South-East corner of Castra Praetoria, the second from Castra Preatoria to Via Nomentana, reached at 1 km from Porta Collina.

To determine with the least possible error Peter’s first burial site, in Figure 7, again on the maps of Lanciani [54], enlarged in the area of interest, we estimate, as follows, a possible area where this site should be located. According to the reconstruction of Section 4, we make the rural road start in Via Tiburtina exiting from Porta Esquilina, close to an aqueduct (point 9 in Figure 7), a few hundred meters from the city. The piece-wise linear path indicated (dashed red line) is the path with minimum distance that allows to bypass Castra Praetoria. The starting point is at about m from the Servian Walls. After the South-East corner of Castra Pretoria the path goes straight to Via Nomentana, reaching a point 1 km from the city. Finally, after having crossed Via Nomentana, the path is almost parallel to the consular road, and at 1.5 km from Porta Collina, Peter disappears downhill. At about 2/3 of the line-of-sight distance between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana, Peter walks left diagonally for m.

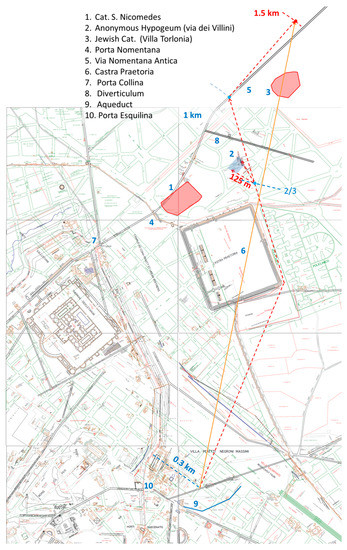

Figure 7.

Map of Rome drawn by Lanciani [54] showing the main archeological remains between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana. The red–dotted lines sketch Peter’s path. The path of the ancient Via Nomentana is in black. The areas in red represent the catacombs. The region highlighted in blue is where Peter’s first burial site should be, according to the topographic elements provided by Maria Valtorta.

We have drawn this path in Figure 7 by considering a range of path orientation given by from North, counterclockwise. These possible uncertainties in distance and orientation determine the blue area of Figure 7 as Peter’s first burial site.

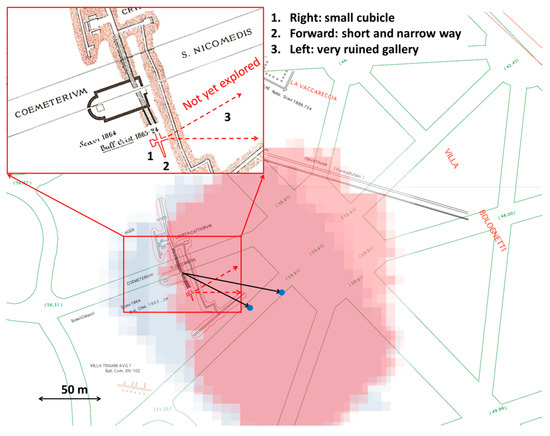

The question now is: What have the archeologists found in the area where the alleged Peter hit the stick on the ground? It is worth noting that the blue area falls on the so-called Anonymous Hypogeum of Via dei Villini (point 2 in Figure 7), a map that is explicitly reported by Lanciani in his Forma Urbis Romae [54]. The line-of-sight between the center of the blue region and the entrance of the hypogeum is about only 20 m. In the next section, we discuss the obtained results, grounding them on the archeological knowledge concerning the catacombs discovered in the area where Peter’s first alleged burial site has been located.

6. Analysis of the Data According to Archeology

At the beginning of the XX century, the Anonymous Hypogeum was considered as the Catacomb of St. Nicomedes, which today is set closer to Porta Nomentana (see point 1 in Figure 7). It is characterized by a very long tunnel: «…the tunnel is maybe the most magnificent and monumental in all Roman catacombs…. It is 50 m long, 2 m wide, and it is all faced with masonry with very high arches of very ancient construction. It is at a depth of 16 m from the country ground above» [57], p. 78. In the Anonymous Hypogeum, the tunnels extended on two superposed levels for a total length of 160 m. Its entrance is located in Via dei Villini 32, today the headquarters of the Figlie del Sacro Cuore di Gesù (“Daughters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus”). At the ground level, originally, there was a small basilica, already completely destroyed when the hypogeum was discovered (1864), for which the plan in the XIX century was reproduced by arrays of cypresses [58], p. 77.

The Passio SS Nerei et Achillei mentioned a catacomb dedicated to this important saint of the I century (Nicomedes), just at the beginning of Via Nomentana. Because of the magnificent tunnel and little basilica on the ground, G. B. De Rossi in 1865 identified it as St. Nicomedes’ catacomb [59], [47], p. 241, and so is termed on the maps drawn by Lanciani at the beginning of the XX century [54]. However, this identification lasted only till the years 1920’s because during the construction of the building of the State Railways, now the headquarters of the Ministry of Infrastructures and Transports, more than 30 tunnels were there discovered, much closer to Porta Pia, from where today Via Nomentana starts (point 1 in Figure 7), in the area of the ancient Villa Patrizi. E. Josi recognized in these tunnels the remains of St. Nicomedes’ Catacombs [60,61]. Now they are inaccessible because of the many buildings [41], pp. 138–139, built in the area of Villa Patrizi, torn down after 1870.

After Josi’s identification of St. Nicomedes’ Catacombs, the important Hypogeum of Via Dei Villini became unexpectedly, “Anonymous”, and as such is known today. Why such hypogeum was without any indication of the martyr to whom it was dedicated?

O. Marucchi proposed the hypogeum could belong originally to the gens Catia [58], p. 77. However, this attribution did not explain the presence of the little basilica at its entrance, already completely destroyed when the hypogeum was discovered, but in which perimeter was still traced with cypresses at the end of XIX century. In fact, the presence of the basilica implies that the site was very important to the first Christians. On this point, De Rossi writes: «It is true that no historical inscription has been found to confirm this opinion [i.e., they were St Nicomedes’ Catacombs] of the Commission of Sacred Theology and scholars of Christian antiquities; but identity of the site, the traces of the oratory, the grand proportions of the stairway, the number of Christian tombs at the ground and underground are sufficient to persuade the value of the topographic argument, in spite of absence of direct epigraphic testimony destroyed by the barbarian invaders» [59], p. 50. If «the basilica built in line before the very deep and wide staircase is a distinctive character of the burial ground and of the site, which properly belongs to the name of the saint» [59], p. 50, and the saint is not St. Nicomedes, as his catacomb was found near Porta Pia, there is an unanswered question: to which important saint were the basilica and the hypogeum below dedicated.

In turn, a new question arises: is there a possible connection between the Anonymous Hypogeum and the alleged Peter’s first burial site? The answer to this question could be affirmative also for another point discussed in the following paragraphs.

Indeed, there is another important discovery to be mentioned. Under Villa Patrizi, De Rossi actually found not one but two hypogea, the largest of which is the Anonymous Hypogeum in Via dei Villini. The most significant characteristics of the second hypogeum are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the second hypogeum discovered by De Rossi in the ancient Villa Patrizi’s area.

Thus, De Rossi explains that the entrances of the two hypogea are very close each other (Table 1). In the Forma Urbis Romae [54], no map of this second hypogeum is shown. In fact, Lanciani drew only its stairways, always starting from the foundation of the vestibule of the basilica where there are the stairways of the Anonymous Hypogeum. This is confirmed by the handwriting reported in the map by Lanciani [54], who wrote, close to the stairways of the second hypogeum: “scavi 1864” (“excavations 1864”)—that is the year when De Rossi explored the two hypogea—with below the reference to the publication “Bull. Crist. 1865—24”. At page 24 of Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana of 1865, vol. 3, we find just a short writing entitled “Un secondo ipogeo cristiano nella Villa Patrizi” (“A second Christian hypogeum in Villa Patrizi” [62]). It is the first published news on the second hypogeum.

Finally, it is interesting also to notice that the archeologist Marucchi, in 1905, relates this unexplored second hypogeum to Peter’s ministry: «In the same Villa Patrizi, there is another hidden stairway which descends to another hypogeum discovered in 1865; in it, they found a piece of a rough inscription regarding a soldier of the cohortes praetoria. … Because the barracks of praetorians [Castra Praetoria] are very close we can very likely suppose that in this site there were other tombs of Christian soldiers. It should be noted that Nicomedes, the eponym of the site, had been himself in relation with the soldiers Nereus and Achilleus, maybe praetorians … and it is also very likely that St. Peter had some relation with these soldiers, as he is attributed the baptism of St. Nereus and St. Achilleus» [57], pp. 346–347. Therefore, this second hypogeum was related also to some Roman soldiers. In any case: (i) it was a Christian cemetery because epigraphic Christian symbols were there found (chi-rho and dove) and there was a basilica at its entrance; (ii) it has been only partially explored; (iii) the reconstruction of Peter’s first burial site, according to Maria Valtorta’s MWs, leads just on the area where in 1864 this hypogeum was discovered. All these points support the conclusion that what Maria Valtorta described about Peter’s first burial site, could not be merely the result of her literary imagination. Maria Valtorta’s hypothesis seems to refer to a well precise site, practically coincident with the second hypogeum, never fully explored. To be confident about this conclusion we need to evaluate the probability that the coincidence may be due only to chance, a check done in the next section.

7. Has Maria Valtorta Invented Peter’s Walk? A Probability Analysis

We have the urgency of dispelling a pressing doubt: has Maria Valtorta invented everything? Was hers just a well done literary work—urgently asked by the Vatican—that only by chance leads on the Anonymous Hypogeum’s area, where is also a second hypogeum not fully explored?

To answer this question, in this section we calculate the likelihood of her hypothesis according to probability theory.

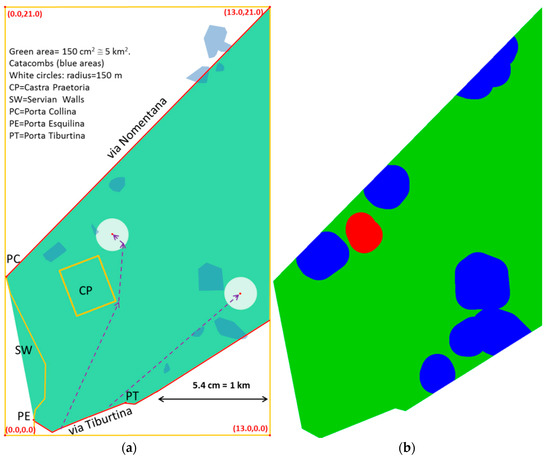

We want to assess the probability that Maria Valtorta, by chance, invented a path that takes Peter: (a) to any catacomb of the area; (b) just near the Anonymous Hypogeum. We use two well-known methods to calculate these probabilities. The first is based on classical geometric probability theory, the second on Monte Carlo simulations of the path according to the data explicitly mentioned by Maria Valtorta on Peter’ walk (for both methods, see, e.g., Reference [64,65]).

7.1. Geometric Probability

The method of geometric probability calculates probabilities as ratios of areas by assuming uniform probabilities of the coordinates of points belonging to the area. In other words, the probability of “falling” in a square of unit area is constant throught the area to which the coordinates belong and given by:

where is the total area.

Figure 8 shows all data necessary for calculating geometric probabilities. It is a map of the region (green area) between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana. The 10 catacombs of the area (or part of them) are marked in dark blue. The arial extension of their maps, taken from Reference [66], has been scaled according to the map of Rome shown in Figure 8a. The clearer green circles represent a circular area of radius , approximately centered on the catacombs. We assume to be arrived at a catacomb if at least a part of its area falls inside the circle, regardless the catacomb extension, and consider as a parameter, so that we can assess how much the probability changes according to . The scale in Figure 8 is , the green area size is (about ). Figure 8a (left panel) shows, just for illustration and not explicitly considered in the following calculations, two possible paths assuming m.

Figure 8.

((a), left panel) Map of the (green) region between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana, with the extensions of the catacombs [66], represented in blue, necessary to calculate the geometric probability of intersecting a circle of radius (white) with a catacomb area (blue). Notice that the paths indicated are not taken into account by the geometric probability calculations, but have been drawn just for the purpose of illustration. ((b), right panel) Example of the convolution product, Equation (2), obtainable with m. The result for the Anonymous Hypogeum is shown in red; the results for the other 9 catacombs are shown in blue.

For calculating the probability of finding, by chance, a path that leads (of unknown starting point) near one of the catacombs (blue area) between via Tiburtina and via Nomentana (green area), we have also considered the catacombs that fall just outside the (green) region between the two consular roads. Indeed, a catacomb just beyond the consular road could be within a circle of radius , of which the center is near the two consular roads. This is the case, for example, of the catacombs to the North-East of Coemeterium Maius and Minus, as well as St. Agnes’ catacombs, which extend underground further North Via Nomentana.

If a circle of radius and center at the coordinates has to intersect the area associated with any of the catacombs , with it is sufficient to impose that its center falls in the area determined by the convolution product—indicated with ⊗—of the area of the circle with the area of the catacomb considered:

Therefore, defined: (a) any path that ends in a point of the green area , i.e., defined a point ; (b) defined a circle of radius centred in , the geometric probability that the end point belongs to the area of a catacomb , is given by:

The limits of (3) are the following. If , the convolution approaches , therefore, the probability tends to the ratio between the fraction of that falls in the green area , divided by . If (very large), the intersection of the area given by the convolution product with is the whole area, and . Figure 8b (right panel) shows, as an example, the result for m. The result concerning the Anonymous Hypogeum is shown in red, and the results for the other 9 catacombs found between, or near, the two consular roads is shown in blue.

Finally, the total geometric probability of ending a path within m from the center of a catacomb is given by:

Besides the theoretical approach with the convolution product, as described above, the geometric probability can also be calculated according to another classic approach, very useful when no theoretical approach is possible, or not considered because too difficult. It consists in generating a large number of random couples of coordinates of the centers of circles of radius , with two independent uniform distributions in a rectangle including the green area, and then calculate the ratio between the number of occurrences, , that a circle, with center in one couple (a point) of coordinates , has a no-null intersection with the total catacomb area , and the total number of occurrences that it falls in the green area . The ratio:

is an estimate of (4).

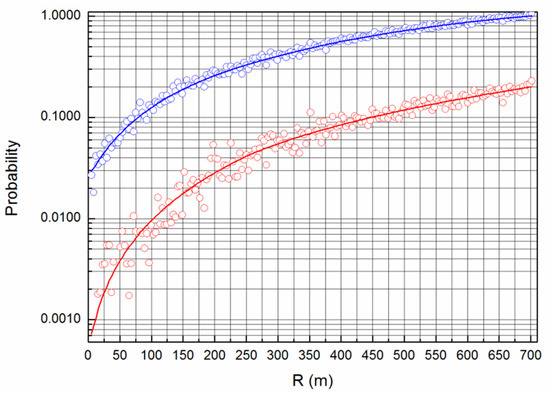

The results given by the convolution calculation, Equation (4), and the results given by the random number method simulations, Equation (5), are shown in Figure 9, as a function of . The continuous lines show the theoretical results (4), the circles show the simulation results (5). The blue color refers to the probability obtained by considering the total catacomb area; the red color to the Anonymous Hypogeum. In other words, given an unknown path within the green area, from these graphs we can read the probability that it ends, for example, at a distance m (This particular value is chosen for comparison with the result reported in Section 7.2) from the Anonymous Hypogeum is approximately (%, red curve and circles). The probability that it ends at a distance m from any catacomb is ().

Figure 9.

Continuous curves: probability defined by Equation (4), as a function of the radius R of the circle, both for all the catacombs present in the green region of Figure 8 or adjacent to it (blue curve), and for the single Anonymous Hypogeum (red curve). The circles represent the results of the simulations, Equation (5).

The latter value, , is already negligible. It means that approximately 8 out of 100 paths can end just on any catacomb of the region. The probability, however, becomes significantly smaller, more than one decade, if we consider only the Anonymous Hypogeum. In this case, about 1 out of 200 paths can end in the Anonymous Hypogeum, and casualness is very doubtful.

The results just discussed assume an unknown path that can take Peter to the Anonymous Hypogeum. In fact, he could have started the walk anywhere along the perimeter of the green area, not specifically from Via Tiburtina. Maria Valtorta, however, gives us some quantitative data and few descriptions of the surrounding area from which we can obtain a specific path, as we show in the next subsection, where we use her data to simulate a bunch of very similar paths which from Via Tiburtina arrive at Via Nomentana, including Peter’s detour. We can also estimate, according to Information Theory [67,68], the probability of these particular paths.

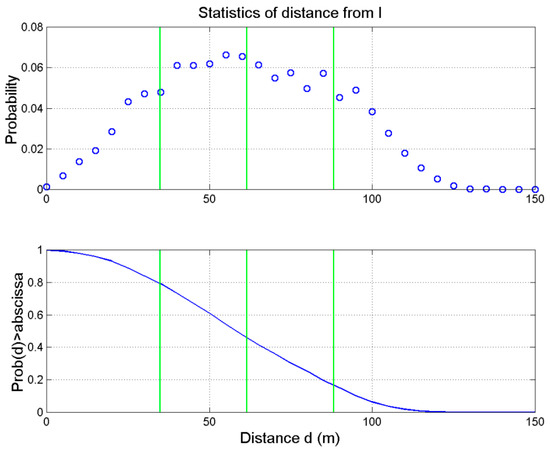

7.2. Monte Carlo Simulations of Peter’s Walk and Its Probability

The so–called “Monte Carlo” simulation is a useful and insightful approach when no theories are available, or they cannot be considered because too difficult to express with mathematical formulae [65]. Compared to the methods of Section 7.1, now it is possible to introduce several constraints, such as those explicitly mentioned by Maria Valtorta on Peter’s walk. In the following, Section 7.2.1, we perform Monte Carlo simulations for obtaining Peter’s path and “stick point” coordinates (i.e., his first burial site); in Section 7.2.2, we estimate the probability of the paths.

7.2.1. Monte Carlo Simulations

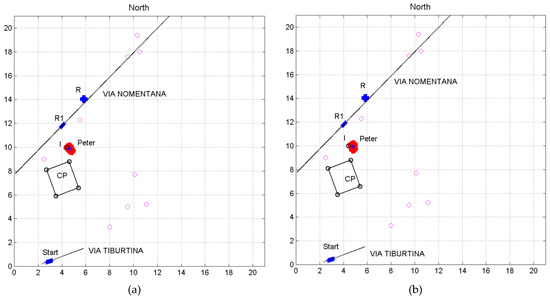

Figure 10 shows the coordinates of the locations useful for the Monte Carlo simulation. Let us assume that the rural road starts on Via Tiburtina exiting from Porta Esquilina (Figure 7). Peter’s path reported by Maria Valtorta can be described with at least the following steps:

Figure 10.

Map of the catacomb area between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana with all coordinates of the locations necessary for the Monte Carlo simulation; scale: . Via Tiburtina beginning at Porta Esquilina is traced with the black line joining and . Via Nomentana is traced with a blue line; the point is approximately km from Porta Collina, point ; the point is approximately km from Porta Collina. Peter’s walk starts at some point of Via Tiburtina, between and . The point marks the breaking point of Peter’s straight walk. The blue short dashed arrow, set approximately at 2/3 of the total path between Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana, locates Peter’s detour point . “I” stands for the Anonymous Hypogeum. The dark blue area show catacombs’ areas with their barycenter’s coordinates.

- (1)