Abstract

The textile industry is one of the largest consumers of water worldwide and generates highly complex and pollutant-rich textile wastewater (TWW). Due to its high load of recalcitrant organic compounds, dyes, salts, and heavy metals, TWW represents a major environmental concern and a challenge for conventional treatment processes. Among advanced alternatives, electrooxidation (EO) and membrane technologies have shown great potential for the efficient removal of dyes, organic matter, and salts. This review provides a critical overview of the application of EO and membrane processes for TWW treatment, highlighting their mechanisms, advantages, limitations, and performance in real industrial scenarios. Special attention is given to the integration of EO and membrane processes as combined or hybrid systems, which have demonstrated synergistic effects in pollutant degradation, fouling reduction, and water recovery. Challenges such as energy consumption, durability of electrode and membrane materials, fouling, and concentrate management are also addressed. Finally, future perspectives are proposed, emphasizing the need to optimize hybrid configurations and ensure cost-effectiveness, scalability, and environmental sustainability, thereby contributing to the development of circular water management strategies in the textile sector.

1. Introduction

The contamination of water bodies by textile wastewater (TWW) represents one of the most significant global environmental challenges. The textile sector, despite being an important economic pillar, generates large volumes of effluents containing persistent and recalcitrant compounds originating from industrial processes. It is estimated that textile activities account for approximately 20% of global drinking water contamination [1,2]. Water use in textile manufacturing varies widely depending on processes, equipment, and chemicals, ranging from 50 to 240 L per kilogram of fabric [3,4]. In the European Union, per capita textile consumption required about 12 m3 of water in 2022, placing the sector among the top contributors to water degradation and land use [5].

Producing one ton of textiles can require 100–200 m3 of water, of which 80–90% is discharged as wastewater [6]. A medium-sized textile facility processing approximately 8000 kg of fabric per day requires around 1.6 million liters of water [7]. Although these figures were reported more than a decade ago, recent assessments indicate that water demand in textile manufacturing remains comparable or even higher, mainly due to the predominance of water-intensive coloration and finishing processes [6,8].

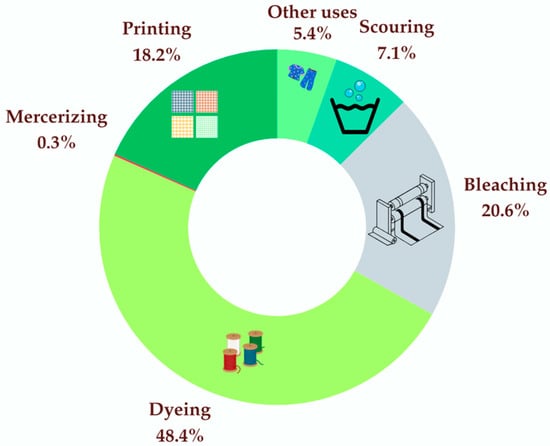

Wet processing stages account for approximately 72% of total water demand in textile production [9,10]. Figure 1 illustrates the average distribution of water consumption among these stages in a typical textile factory, including dyeing, bleaching, scouring, printing, mercerizing, and other minor operations. Dyeing consumes between 30 and 150 L per kilogram of fabric, depending on the dye type (e.g., reactive, vat, disperse) and substrate (e.g., cotton, polyester, or blends). The dye uptake is also enhanced by auxiliary chemicals [11,12]. Furthermore, textile dyeing and finishing activities contribute to approximately 17–20% of the global industrial water pollution, reinforcing the sector’s substantial environmental impact [8,13].

Figure 1.

Water consumption in various steps involving wet processing (adapted from Frazier et al. [14]). “Other uses” include sizing (1.3%), desizing (3.3%), and finishing (0.8%).

TWW is characterized by intense color, the presence of toxic aromatic compounds, wide pH variation, and high concentrations of dissolved salts and suspended solids. Its biodegradability is typically low to moderate, as reflected by reported biochemical oxygen demand/chemical oxygen demand (BOD/COD) ratios generally ranging from 0.2 to 0.4, depending on the textile process and chemical additives involved [9,12,15]. These values are significantly lower than those commonly observed in municipal wastewater, indicating the presence of recalcitrant organic compounds, such as synthetic dyes and auxiliary chemicals, which pose significant challenges for treatment and disposal [15,16].

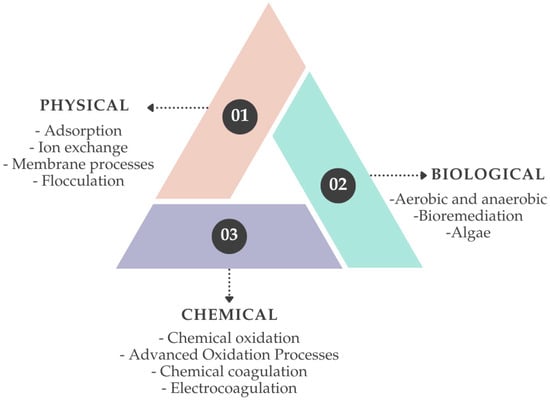

A wide range of treatment technologies has been investigated for TWW, including biological, chemical, and physical processes (Figure 2). Biological treatments are widely applied but typically require long hydraulic retention times, large operational areas, and often exhibit limited efficiency toward dyes and toxic compounds [17,18,19]. Chemical processes such as coagulation, electrocoagulation (EC), and Fenton-based processes are effective in removing color and organic matter. However, they are associated with sludge generation, chemical consumption, and secondary waste streams [20,21]. In particular, Fenton and Fenton-like processes are among the most extensively studied advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for printing and dyeing wastewater, owing to their strong oxidative capacity, although their application is constrained by iron sludge production and narrow optimal pH ranges [22,23].

Figure 2.

Commonly used treatment methods for textile wastewater.

Other AOPs, including ozonation, UV-based photochemical processes, photocatalysis, electrooxidation (EO), and, more recently, plasma-based processes, have received increasing attention for TWW treatment [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Plasma technologies generate a complex mixture of highly reactive species (e.g., •OH, O•, O3, H2O2) and have demonstrated strong potential for the degradation of dyes and refractory organic pollutants, although their high energy demand and reactor complexity currently limit large-scale application [30,31]. Despite their high oxidation efficiency, many AOPs may lead to the formation of undesirable organic and inorganic by-products, depending on operating conditions. For instance, ozonation may result in bromate and aldehyde formation [32], Fenton processes can generate residual iron salts and organic acids [22], and EO may form halogenated by-products such as trihalomethanes, haloacetic acids, chlorate, and perchlorate, sometimes exceeding World Health Organization (WHO) guideline values [33]. These issues highlight the need to carefully monitor and control the formation of by-products during wastewater treatment.

Among physical treatment technologies, adsorption, ion exchange, and membrane processes are widely applied [34,35,36]. These methods are relatively simple and require limited chemical inputs, but they often generate concentrated residual streams and show limited effectiveness when used as standalone treatments for complex TWW [37,38]. Pressure-driven membrane processes, particularly nanofiltration and reverse osmosis, are currently the most effective technologies for removing dissolved salts and reducing effluent conductivity, which is a critical prerequisite for water reuse in textile production [39,40]. However, salt accumulation in the retentate stream represents a major operational and environmental challenge, further emphasizing the importance of integrated treatment schemes.

To overcome the limitations of individual processes, the integration of multiple treatment technologies is increasingly pursued. Combined systems capitalize on the complementary strengths of different approaches, resulting in enhanced pollutant removal, reduced by-product formation, and improved overall performance [41,42]. In this context, the integration of AOPs with membrane processes has emerged as a particularly promising strategy [43,44]. EO is recognized as one of the most versatile AOPs, capable of effectively degrading recalcitrant organic pollutants and reducing effluent toxicity under suitable operating conditions [45,46,47]. Membrane technologies, in turn, provide efficient separation of dissolved salts and ionic species, addressing a critical limitation of EO when water reuse is targeted [48].

While several reviews have addressed AOPs, membrane technologies, or their integration, most focus on combinations involving ozonation, Fenton-based processes, or photocatalysis [49]. To date, no review has specifically focused on the integration of EO with membrane processes as a distinct treatment concept for TWW. This review fills a critical niche by providing a focused analysis of EO–membrane systems, emphasizing their mechanistic complementarity, quantitative performance improvements, implications for water reuse, and key challenges related to energy demand, fouling control, and concentrate management. By comparing standalone and integrated configurations, this work highlights the unique potential of EO–membrane systems for sustainable and circular water management in the textile industry.

2. Textile Wastewater Characteristics

TWW exhibits a highly variable composition depending on the type of fiber, dye class, and auxiliary products employed during textile processing. TWW contains both synthetic and natural dyes, chemicals such as oils, detergents, acids, and salts, as well as metals and heavy metals [8,50,51,52]. It typically shows high levels of COD and total dissolved solids (TDS), low biodegradability, intense coloration, and a wide pH range (2–12). Approximately 40% of textile dyes contain organically bound chlorine [53]. Dos Santos et al. [54] demonstrated that the impact of different fibers on effluent composition varies significantly. Polyamide-dyeing effluents primarily affect aluminum, manganese, and total chromium concentrations. Polyester effluents have a greater influence on color, turbidity, total iron, BOD, COD, phenols, mercury, oil and grease, and total phosphorus. In contrast, viscose effluents mainly interfere with pH, alkalinity, and dissolved solids due to the use of reactive dyes and high electrolyte concentrations.

Among organic compounds, auxiliary agents such as surfactants, dispersants, and complexing agents, together with dyes, are particularly persistent in TWW [55,56]. The presence of these compounds can alter electrochemical kinetics during EO, diverting applied current toward side reactions such as oxygen evolution rather than pollutant degradation [57]. In addition, the formation of complexes between dyes and metal cations, such as Ca2+, Mg2+, or Fe2+, can hinder the attack of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) on target pollutants, further limiting EO efficiency [58]. Synthetic dyes are generally chemically stable and resistant to conventional degradation pathways, often leading to the formation of persistent intermediates. These recalcitrant compounds contribute to color persistence, elevated BOD and COD levels, and potential toxicity in treated effluents, highlighting the need for advanced and integrated treatment strategies to achieve effective mineralization and safe water reuse [59,60].

Salinity, mainly derived from the use of NaCl or Na2SO4 as dyeing auxiliaries, is another defining feature of TWW [61,62]. While increased electrolyte conductivity can enhance current efficiency and overall EO performance [63], high salinity can adversely affect membrane-based processes by promoting scaling, fouling, and long-term performance deterioration [62,64]. In addition, heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, Cr, As, and Hg, commonly present in pigments and dyes, may further compromise both EO and membrane performance through electrode poisoning, membrane fouling, or the formation of stable metal–organic complexes [65,66]. Understanding these interactions is therefore essential for the rational design of EO–membrane treatment systems.

In summary, the complexity of TWW arises not only from its diverse composition but also from chemical interactions among its components. Table 1 illustrates this complexity by presenting representative TWW characteristics reported for industrial textile effluents worldwide [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. To contextualize these data, Table 2 summarizes selected regulatory discharge limits established by different authorities for textile effluents [80,81,82], which define increasingly stringent requirements for pollutant removal and water quality.

Table 1.

Characteristics of real textile effluents from different countries.

Table 2.

Main discharge limits into water bodies for textile wastewaters.

The combination of high color intensity, recalcitrant organic compounds, variable biodegradability, elevated salinity, and metal content significantly limits the effectiveness of conventional physical, chemical, and biological treatment processes when applied to TWW. These constraints provide a clear rationale for focusing on advanced oxidation and membrane-based technologies, which are better suited to address the specific challenges posed by textile effluents. Accordingly, the following sections examine EO, membrane processes, and their integration as targeted treatment strategies for TWW.

3. Textile Wastewater Treatment by Electrooxidation

In recent years, EO has gained increasing attention as an advanced treatment technology for textile effluents, particularly for the degradation of recalcitrant organic pollutants [45,47,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. The growing interest in EO is primarily attributed to its ability to generate highly reactive oxidizing species in situ, without the need for external chemical reagents, thereby minimizing secondary pollution and enhancing process sustainability [90].

The fundamental feature of EO is the water oxidation at the anode surface, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including adsorbed hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (Equation (1)), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Equation (2)), and ozone (O3) (Equation (3)) [88]. Hydroxyl radicals are among the most powerful oxidants (E0 = 2.8 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode) and play a key role in the non-selective degradation of a wide range of organic compounds [84]. Depending on the anode material, •OH can be weakly or strongly adsorbed. When weakly adsorbed, •OH radicals remain highly reactive, promoting the complete mineralization of organic pollutants to CO2, H2O, and inorganic ions [90,91].

H2O → •OH + H+ + e−,

2 •OH → H2O2,

3 H2O → O3 + 6 H+ + 6 e−.

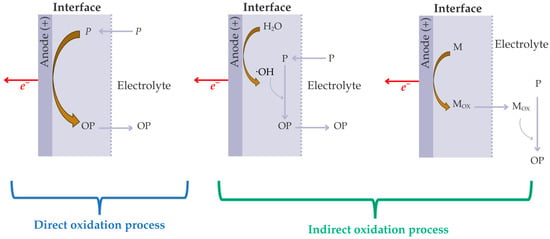

EO involves anodic oxidation reactions that proceed through two different but often concurrent pathways: direct anodic oxidation and indirect oxidation mediated by electrogenerated oxidants (Figure 3). In direct oxidation, organic pollutants are oxidized by direct electron transfer at the anode surface [84,88]. This mechanism is strongly dependent on the nature and activity of the electrode surface and is often limited by mass transfer and electrode fouling caused by the accumulation of polymeric or passivating intermediates [88]. Despite this limitation, direct oxidation plays a crucial role in initiating the formation of powerful oxidizing agents that drive indirect oxidation processes. Indirect oxidation occurs through the action of electrogenerated oxidants, which can react with pollutants either at the electrode surface or in the bulk solution (Figure 3) [84].

Figure 3.

Schematics of the direct and indirect mediated oxidation mechanisms in EO processes (adapted from Mitsudo et al. [92]). P: Pollutants; OP: Oxidized pollutants; M: Mediator species (chloride, sulfate, bicarbonate, phosphate, etc.); Mox: Electrogenerated oxidants from mediator species.

In addition to ROS, several other oxidizing species may be formed at the anode, depending on the electrolyte composition. In chloride-containing media, chloride ions can be anodically oxidized to chlorine gas (Equation (4)), which subsequently hydrolyzes to hypochlorous acid (Equation (5)) and dissociates to hypochlorite ions (Equation (6)) [93,94]. These active chlorine species act as secondary oxidants capable of degrading organic and inorganic contaminants throughout the solution. However, they may promote the formation of chlorinated organic by-products and inorganic halogenated species, which are potentially harmful [84,93,94]. Beyond chlorine-based oxidants, other strong oxidizing agents can also be generated electrochemically. Persulfate (S2O82−) can be produced via the anodic oxidation of bisulfate or sulfate ions (Equation (7)), while peroxodicarbonate (C2O62−) and peroxodiphosphate (P2O84−) may be formed from bicarbonate (Equation (8)) and phosphate ions (Equation (9)), respectively [88]. These species further contribute to pollutant degradation through homogeneous oxidation reactions in the bulk solution, enhancing overall treatment efficiency [95].

2Cl− (aq) → Cl2 (g) + e−,

Cl2 (aq) + H2O (l) → HOCl (aq) + H+ (aq) + Cl− (aq),

HOCl (aq) → OCl− (aq) + H+ (aq),

2 HSO4− (aq) → S2O82− (aq) + 2 H+ (aq) + 2 e−,

2 HCO3− (aq) → C2O62− (aq) + 2 H+ (aq) + 2 e−,

2 PO43− (aq) → P2O84− (aq) + 2 e−.

EO stands out for its versatility, ease of operation, and high efficiency, using the electron as a “clean reagent” [45,96]. The anode material plays a decisive role in EO performance, as it governs the nature of the oxidizing species formed, oxidation pathways, current efficiency, and long-term stability. Key electrochemical properties include oxygen evolution overpotential, electrical conductivity, chemical and electrochemical stability, and the strength of interaction with surface-bound hydroxyl radicals [57,88]. Electrodes with high oxygen evolution overpotential favor the accumulation of •OH radicals and non-selective oxidation, whereas electrodes with lower overpotential tend to promote indirect oxidation via active chlorine or other mediators [88].

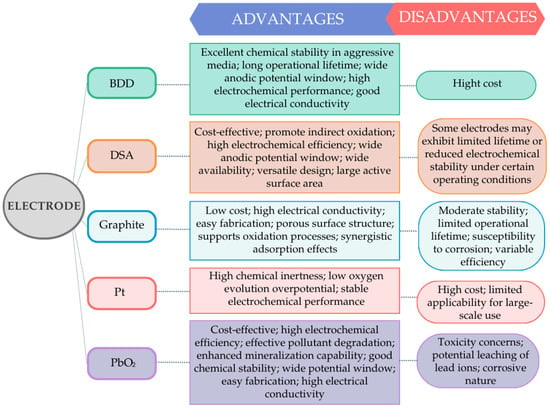

Most common EO anodes include noble metals (e.g., Pt), carbon-based electrodes, metal oxides such as PbO2 and SnO2, dimensionally stable anodes (DSA), and boron-doped diamond (BDD) [57,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. Figure 4 schematically summarizes the main advantages and limitations of the most commonly used anode materials in EO.

Figure 4.

Main advantages and disadvantages of different electrodes in electrooxidation treatment (adapted from Särkkä et al. [84] and Rodríguez-Narváez et al. [106]).

BDD stands out due to its weak interaction with surface-bound hydroxyl radicals, which enables their reaction with organic pollutants, resulting in high current efficiency and enhanced mineralization [87]. In addition, BDD exhibits a wide electrochemical potential window, high oxygen evolution overpotential, outstanding chemical and electrochemical stability, and low adsorption of intermediates, which collectively favor non-selective oxidation [57,88]. Several studies have reported complete COD and color removal from real TWW using EO with BDD anodes [45,87]. However, despite positioning BDD as a benchmark electrode material for EO, its high cost remains a major limitation for large-scale and industrial applications [45].

Metal oxide and mixed metal oxide (MMO) electrodes represent a more economically viable alternative [84,87]. DSAs consist of catalytically active metal oxides (e.g., RuO2, IrO2) coated onto a titanium substrate, providing excellent mechanical integrity, corrosion resistance, and long operational lifetimes under acidic and alkaline conditions [33,45,87]. DSAs exhibit high electrical conductivity but relatively low oxygen evolution overpotentials, which favor indirect oxidation pathways via active chlorine species in chloride-containing TWW [95]. In contrast, SnO2- and PbO2-based MMO electrodes, particularly when doped with elements such as Sb or F, exhibit higher oxygen evolution overpotentials, which enhance the formation and persistence of surface-bound hydroxyl radicals [45,57,104]. This behavior promotes non-selective oxidation and deeper mineralization of organic pollutants, albeit sometimes at the expense of electrode lifetime and stability [45].

The influence of MMO composition on oxidation pathways was demonstrated by Zayas et al. [107], who studied EO in chloride-containing media using DSA-type anodes (Ti/PtPb(1%)Oₓ and Ti/PtPd(10%)Oₓ). Their results showed that indirect oxidation via active chlorine species dominated, depending on the anode formulation. The Ti/PtPd(10%)Oₓ anode achieved up to 97% COD removal within 45 min over a wide pH range (4–8), whereas Ti/PtPb(1%)Oₓ reached only 25% removal after 65 min, underscoring the critical role of MMO composition, oxygen evolution overpotential, and electrochemical stability in determining EO efficiency.

Operational parameters also strongly influence EO performance. Martínez-Huitle et al. [54] investigated the treatment of real TWW using BDD anodes and demonstrated that COD and color removal strongly depended on the applied current density (20–60 mA cm−2), while the addition of Na2SO4 enhanced treatment efficiency by promoting the in situ generation of strong oxidants, thereby reducing treatment time and operational costs. In a different study, Basha et al. [108] treated Procion Blue dye bath and washing effluents using RuOₓ–TiOₓ-coated titanium anodes in batch and recirculation reactors. COD removal ranged from 53% to 94%, depending on reactor configuration, current density (up to 5 A m−2), flow rate (100 L h−1), and treatment time (6–8 h), highlighting the decisive influence of both electrode composition and operating conditions on EO performance.

Increasing the applied current density generally enhances pollutant degradation rates but also increases energy consumption and may promote undesired side reactions such as oxygen evolution [88]. pH affects oxidant speciation, electrode stability, and reaction kinetics, while the type and concentration of supporting electrolyte govern solution conductivity, oxidant formation pathways, and energy efficiency [57,88]. Energy consumption in EO is, therefore, highly dependent on anode material, current density, and electrolyte composition, with reported values for TWW typically ranging from a few to several tens of kWh kgCOD−1, depending on treatment targets and operating conditions [57,106,107,108,109]. Table 3 compiles selected EO studies treating real TWW, providing a comparative perspective on treatment efficiency and energy demand as a function of electrode material and operating conditions.

Table 3.

Summary of research results reported for real TWW treatment by electrooxidation.

EO can achieve near-complete color and COD removal, confirming its effectiveness as an advanced oxidation process for textile effluents [57,107,108,109]. Still, several challenges limit its large-scale implementation. Recent research has increasingly focused on the modification of conventional anodes through the development of doped metal oxides, nanostructured and composite coatings, and hybrid materials that combine high catalytic activity with enhanced corrosion resistance and stability [33,76]. These advances aim to optimize the trade-off between pollutant removal efficiency, energy consumption, long-term durability, and control of undesirable oxidation by-products. Nevertheless, a fundamental limitation of EO is its inability to remove dissolved inorganic salts, resulting in limited control of effluent salinity. Since high conductivity and salt content are critical barriers to the reuse of treated wastewater in textile production, EO alone is insufficient to meet reuse requirements. Consequently, despite significant technological progress, EO is most effective when integrated with complementary separation processes, particularly membrane technologies capable of salt removal, highlighting its role as a key component within combined and hybrid treatment schemes rather than as a stand-alone solution.

4. Textile Wastewater Treatment by Membrane Processes

Membrane-based processes are increasingly applied in TWW treatment due to their high separation efficiency and their potential to enable water reuse [110,111,112,113]. The operation of membrane technologies is based on semi-permeable and selective barriers that allow for the passage of certain components while retaining others [114]. In reverse osmosis (RO), for example, water passes through the membrane while most ions and salts are rejected, resulting in a permeate that is virtually free of ions and a concentrate with high salinity [110].

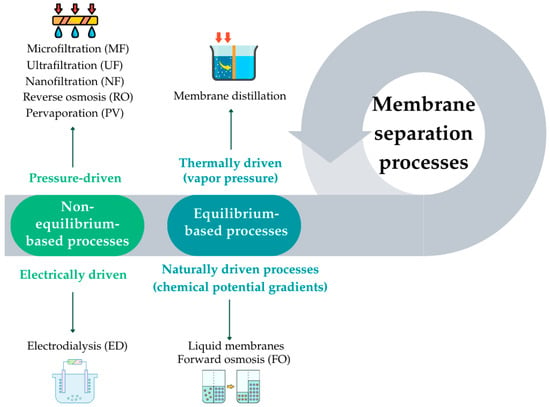

Membrane processes serve several purposes, including the removal of solids, reduction in organic load, and water desalination [115]. Depending on the membrane selected and the driving force involved, membrane separation processes can be classified based on their thermodynamic foundation as either non-equilibrium-based or equilibrium-based processes [116]. Non-equilibrium-based processes include: (a) pressure-driven processes, such as microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), and RO, in which separation is forced by an externally applied hydraulic pressure [113,117,118,119]; and (b) electrically driven processes, such as electrodialysis (ED), where ion transport occurs under an applied electric field [112]. Equilibrium-based processes, on the other hand, involve separation mechanisms that occur near thermodynamic equilibrium and are driven by natural gradients. These include membrane distillation (MD), a thermally driven process based on vapor pressure differences [120,121]. Other examples are liquid membranes and forward osmosis (FO), which operate without external pressure and instead rely on concentration or chemical potential gradients as the driving force. Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of some of these techniques, organized according to their driving forces and thermodynamic basis [116].

Figure 5.

Schematic overview of membrane separation processes classified according to the main driving forces (adapted from Wankat [116]).

The performance, selectivity, and durability of membrane processes are strongly influenced by the membrane material [122]. Polymeric membranes currently dominate commercial MF, UF, NF, and RO applications due to their relatively low production costs, ease of fabrication, and well-established manufacturing processes, as well as the ability to tailor surface properties to specific separation requirements [64,123]. Common polymeric materials include polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyethersulfone (PES), polysulfone (PSU), polypropylene (PP), and polyamide (PA), which provide adequate separation efficiency for a wide range of water and wastewater treatment applications [123,124]. However, despite these advantages, polymeric membranes present several operational limitations in demanding environments, such as their relatively narrow operating temperature window, limited resistance to strong oxidizing agents and organic solvents, and susceptibility to mechanical degradation under high-pressure conditions [124]. In contrast, ceramic membranes composed of inorganic oxides such as alumina (Al2O3), zirconia (ZrO2), or titania (TiO2) exhibit superior thermal, chemical, and mechanical stability compared to polymeric membranes, enabling operation under high temperatures, extreme pH conditions, and aggressive wastewater environments, which is particularly advantageous for TWW treatment [124,125,126].

Membrane processes are widely recognized as effective technologies for TWW treatment, offering high separation efficiency, operational flexibility, and the ability to produce high-quality permeate suitable for water reuse and resource recovery [64,114]. Nevertheless, due to the complex composition of raw TWW, characterized by high concentrations of suspended solids, colloidal matter, oils, surfactants, dyes, and inorganic salts, membrane systems cannot be effectively applied as stand-alone treatments [8,52]. Direct feeding of untreated TWW into membrane units typically results in severe fouling, scaling, and rapid deterioration of performance. Indeed, membrane fouling, caused by the deposition of particles, biomolecules, salts, and other substances on the membrane surface or within its pores, remains the main operational limitation, leading to reduced permeate flux, altered selectivity, and shortened membrane lifespan [64]. Therefore, appropriate primary treatment and pretreatment steps are required before membrane filtration.

Conventional primary treatments, such as screening, sedimentation, equalization, and pH adjustment, are commonly employed to remove coarse solids and mitigate fluctuations in flow and composition [114]. These steps are frequently followed by physicochemical pretreatments, including coagulation–flocculation, flotation, or adsorption, which effectively reduce suspended solids, colloids, and color [123]. Biological treatments, when applicable, can further decrease biodegradable organic load, although their effectiveness is often limited for dye-rich textile effluents with low biodegradability [110].

Even when adequate primary and pretreatment steps are implemented, membrane fouling remains unavoidable during long-term operation. Consequently, suitable operational and maintenance strategies are needed to sustain membrane performance. While disinfection is often required, some membrane materials, particularly RO membranes, are not compatible with chlorine-based disinfectants. In such cases, chemical cleaning procedures using detergents or acidic and basic solutions are commonly applied to restore membrane permeability without compromising its integrity [123].

Fouling propensity is also strongly influenced by membrane material properties, particularly surface hydrophobicity. Hydrophobic membranes promote the formation of liquid–vapor interfaces at pore entrances, a phenomenon that is fundamental for MD, where hydrophobicity is advantageous for vapor transport [64,123,127]. In contrast, in pressure-driven processes such as RO, membrane hydrophobicity can hinder water transport and enhance the deposition of organic matter and salts, thereby exacerbating fouling and reducing membrane lifespan [124].

From an economic and durability perspective, membrane processes differ substantially. Energy consumption and economic performance vary significantly among membrane processes and are closely linked to operating pressure, system configuration, and membrane durability. MF and UF are generally characterized by low specific energy consumption, typically below 0.5 kWh m−3, owing to their lower transmembrane pressures, which also translate into lower capital and operating costs and longer membrane lifetimes [114,128]. In contrast, NF and RO operate at higher pressures and therefore exhibit higher energy demands and operating costs, despite offering superior separation efficiency. These tighter membranes are also more sensitive to fouling and chemical degradation, which can reduce operational lifespan if insufficient pretreatment is applied [123,128]. MD systems represent a distinct case, as their energy consumption depends primarily on thermal efficiency and the availability of heat recovery or low-grade waste heat. While offering high salt rejection and tolerance to high-salinity feeds, MD still faces challenges related to membrane wetting, thermal efficiency, and membrane cost, which currently limit large-scale industrial implementation [121,127]. Table 4 summarizes selected membrane-based studies treating real TWW, providing a comparative overview on treatment efficiency, operating conditions, and reported operational cost where available.

Table 4.

Summary of research results reported for real TWW treatment by membrane processes.

MF and UF are commonly employed as pretreatment steps for tighter membranes such as NF and RO [139]. MF membranes, with typical pore sizes ranging from 0.1 to 3 μm, effectively retain suspended solids while allowing dissolved species to pass [49,128]. For example, the combination of MF followed by NF achieved 85% COD and 98% color removals, whereas MF followed by RO increased removals to 97.5% for COD and 99.3% for color [139]. Similar trends have been reported for UF-based configurations, where UF pretreatment reduced fouling and enhanced the performance of subsequent NF or RO steps [129,131,140].

Membrane selectivity plays a crucial role in determining treatment objectives, particularly in terms of removing dyes, organic matter, and dissolved salts. MF and UF primarily act as size-exclusion barriers, effectively removing suspended solids, colloids, and high-molecular-weight organic compounds, but exhibiting limited rejection of dissolved salts and low-molecular-weight dyes [128,140]. NF membranes offer intermediate selectivity, retaining multivalent ions, unfixed reactive dyes, and a significant fraction of dissolved organic matter, while allowing partial passage of monovalent salts [132]. RO membranes provide the highest selectivity, rejecting both mono- and multivalent ions as well as residual dyes, enabling the production of low-conductivity permeates suitable for internal reuse in textile processes [142]. MD membranes exhibit near-complete rejection of non-volatile solutes, including salts and dyes, independent of molecular size or charge, making them particularly attractive for high-salinity textile effluents [143]. In addition, its ability to operate at low temperatures and atmospheric pressure enables the use of low-grade waste heat from industrial processes, improving overall energy efficiency and facilitating integration into existing textile production lines, particularly in heat recovery applications [145,146].

While these high separation efficiencies enable the production of high-quality permeate, they inevitably lead to the generation of a concentrated residual stream (retentate) enriched in salts, dyes, and organic matter [147]. Proper management of this concentrate is essential to avoid secondary pollution and to ensure sustainable operation. Strategies for concentrate management include further treatment by advanced oxidation processes, such as EO, volume reduction through additional membrane concentration, controlled discharge under regulatory limits, or valorization approaches aimed at recovering salts, dyes, or energy [148].

End-of-life management of membranes and associated residues is another important sustainability consideration. Spent polymeric membranes are commonly disposed of by landfilling or incineration, although recycling and repurposing strategies, such as membrane reconditioning or conversion into filtration supports, are increasingly being explored [147]. Ceramic membranes, due to their inert nature and long operational lifetime, generate less solid waste and can often be regenerated through aggressive chemical or thermal treatments [124]. In addition, sludge generated during pretreatment steps (e.g., coagulation–flocculation) or membrane cleaning processes must be properly managed to avoid secondary environmental impacts. Sludge management typically includes conditioning, thickening, and dewatering to reduce volume and facilitate final disposal, further treatment, or beneficial reuse, as part of an integrated waste-handling strategy in wastewater treatment systems [149]. In industrial facilities, including TWW treatment, high sludge production associated with coagulation–flocculation and other physicochemical processes has been identified as a significant operational challenge, underscoring the need for proper sludge dewatering and disposal solutions [150].

When considered as standalone technologies for TWW treatment, EO and membrane processes exhibit fundamentally different roles and performance profiles. EO is primarily a destructive technology, capable of efficiently degrading recalcitrant organic compounds and achieving high color removal, often exceeding 80–90%, together with significant COD reduction, depending on the anode material and operating conditions [45,57,87]. However, EO does not remove dissolved inorganic salts and, in chloride-rich textile effluents, may lead to the formation of halogenated by-products, which limits its applicability for direct water reuse in textile processes [33,48,95].

In contrast, membrane technologies are separation-based processes that do not degrade pollutants but physically retain suspended solids, dyes, and dissolved salts with high efficiency. Pressure-driven membranes such as NF and RO are particularly effective in reducing conductivity and salinity, which is a critical requirement for internal water reuse in textile manufacturing [39,40,132,142]. Nevertheless, when applied alone to complex TWW, membrane processes are highly susceptible to fouling and scaling, especially in the presence of high organic loads, dyes, surfactants, and colloidal matter, resulting in flux decline, increased energy consumption, and reduced membrane lifetime [64,114,123].

The combined use of EO and membrane processes can address these complementary limitations. In integrated EO–membrane systems, EO can be applied as a pretreatment to oxidize dyes and recalcitrant organic compounds, reduce color, and lower fouling propensity, thereby improving membrane permeability and operational stability [43,44,57]. In addition, EO may be applied as a post-treatment to membrane concentrates, where higher pollutant loads and conductivity favor oxidant generation, enabling the degradation of retained organic contaminants and facilitating safer disposal or further valorization of the retentate. Conversely, membrane processes compensate for the intrinsic limitation of EO by efficiently removing dissolved salts, oxidation by-products, and residual organic matter, enabling the production of permeate suitable for reuse within textile operations [48,132,145].

Beyond laboratory-scale studies, membrane technologies are already widely implemented at an industrial scale in the textile sector, particularly MF and UF as pretreatment steps and NF/RO for water reuse. Several textile plants worldwide operate membrane-based systems to reduce water consumption and comply with discharge regulations, especially in regions facing water scarcity. Integrated UF–RO systems have been deployed in industrial textile parks to reclaim printing and dyeing wastewater and reduce freshwater consumption at capacities of up to 40,000 m3/d−1, producing high-quality permeate for reuse [151]. Similarly, industrial pilot application of UF–NF membranes in the textile district of Prato (Italy) demonstrates the feasibility of membrane-based reuse strategies under real operating conditions [152]. This industrial adoption highlights the technological maturity of membrane processes and provides a solid foundation for their integration with complementary treatment technologies.

5. Hybrid and Combined Systems Involving Electrooxidation and Membrane Processes for TWW Treatment

EO has progressed beyond laboratory-scale research, with several pilot-scale applications demonstrating its feasibility for real TWW. For example, a pilot-scale EO + NF system achieved nearly complete color removal and salt recovery, enabling reuse in fabric dyeing operations [153]. Combined pilot-scale schemes integrating EO with other unit processes have also shown high pollutant removal efficiencies for TWW [154]. These practical applications illustrate the technological maturity of EO and reinforce its suitability for integration with membrane processes in hybrid and combined treatment schemes.

It is important to differentiate combined processes from hybrid processes when discussing EO–membrane integration. Combined processes apply different treatment technologies sequentially in separate units, whereas hybrid processes integrate two or more technologies within a single, unified system. Consequently, all hybrid systems can be regarded as combined processes, but not all combined processes qualify as hybrid systems [155]. Hybrid and combined approaches have gained attention for TWW treatment, because they can overcome the limitations of individual methods and improve pollutant removal, minimizing toxic byproducts and enabling water reuse [46].

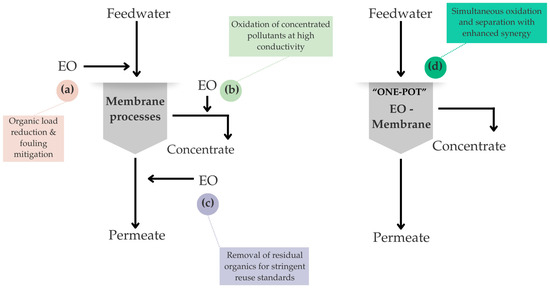

Hybrid and combined approaches that integrate EO or other AOPs with membrane technologies have shown enhanced performance for TWW treatment. Such methodologies improve the removal of organic compounds, color, COD, and solids. They reduce membrane fouling and enable water reuse due to oxidative degradation and selective membrane separation, often exhibiting synergistic effects [44,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166]. Figure 6 schematically summarizes the main strategies for integrating EO with membrane processes in TWW treatment. When EO is applied as a pre-treatment (Figure 6a), the partial oxidation of dyes and recalcitrant organic compounds reduces color and organic load, resulting in lower fouling propensity and improved membrane permeability. In contrast, the post-treatment of membrane concentrates by EO (Figure 6b) takes advantage of the higher conductivity and pollutant concentration of the retentate, which enhances oxidant generation and improves energy efficiency, while simultaneously mitigating the environmental impact associated with concentrate disposal [167]. Advanced permeate treatment (Figure 6c) may be considered when stringent water reuse standards are required. However, its applicability is often limited by low pollutant concentration and conductivity, leading to higher specific energy consumption [90,168]. Finally, single-stage or “one-pot” configurations (Figure 6d) highlight the synergistic interaction between electric fields and membrane separation, enabling effective fouling mitigation, enhanced permeation flux, and extended membrane lifespan, while the compact design minimizes the system footprint [167,169,170]. Overall, these configurations provide a conceptual framework to guide the selection of EO–membrane integration strategies according to wastewater characteristics and treatment objectives.

Figure 6.

Main strategies for EO–membrane integration: (a) EO as pre-treatment (feedwater pre-treatment); (b) EO as post-treatment of concentrate; (c) EO for advanced permeate treatment; (d) Hybrid/one-pot EO–membrane system (adapted from Pan et al. [168]).

Based on the integration strategies illustrated in Figure 6, EO–membrane systems applied to TWW treatment can be broadly classified into three main configurations: (i) membrane processes applied as post-treatment after EO (EO + membrane), (ii) membrane processes followed by EO for concentrate treatment (membrane + EO), and (iii) hybrid or single-stage EO–membrane systems. These integrated approaches also support strategies aimed at minimizing effluent discharge, such as Minimum and Zero Liquid Discharge (MLD/ZLD), emphasizing the importance of combining multiple treatment steps to achieve water reuse and sustainability goals [171]. It should be noted that achieving zero liquid discharge is not feasible through a single treatment process alone and necessarily requires the integration of multiple complementary technologies [172].

Table 5 summarizes the main studies reported in the literature for the three EO-membrane configurations applied to TWW treatment, including operational conditions, electrochemical and membrane setups, and key treatment performances.

Table 5.

Summary of research results reported for TWW treatment by EO–membrane configurations.

The three EO–membrane integration strategies presented in Table 5 differ markedly in terms of treatment objectives, operational complexity, and energy performance, and their suitability is strongly dependent on the TWW characteristics and the intended reuse or discharge goals. Rather than representing competing solutions, these configurations address distinct roles within integrated treatment schemes.

When EO is applied as a pretreatment before membrane filtration (EO + membrane), its primary function is the partial oxidation of dyes and recalcitrant organic compounds, resulting in reduced color, COD, and fouling propensity of the feed stream [153]. This configuration is particularly advantageous for TWW characterized by high organic load and intense coloration, where membrane operation is often limited by rapid flux decline and frequent cleaning. Different studies report improved permeate flux stability and reduced transmembrane pressure when NF or RO is preceded by EO [184]. However, because EO is applied to the entire wastewater volume, its competitiveness strongly depends on careful optimization of current density, electrode material, and treatment time. Excessive oxidation may increase energy demand and promote the formation of low-molecular-weight by-products that are poorly retained by membranes or contribute to secondary fouling. From an energy perspective, EO as a pre-treatment is most competitive when fouling mitigation and membrane protection outweigh the added electrochemical energy demand.

In contrast, configurations in which membrane processes are applied upstream and EO is used as a post-treatment step (membrane + EO) primarily target the treatment of concentrated streams. In this approach, membranes concentrate salts and organic pollutants, while EO is applied to the retentate, where higher conductivity and pollutant concentration enhance oxidant generation and current efficiency [184,185]. Treating a smaller volume with elevated conductivity generally results in lower specific energy consumption compared to EO applied to raw wastewater [186]. This configuration is therefore particularly suitable for saline TWW and for treatment schemes aiming at MLD/ZLD, where reducing effluent volume and enabling water reuse are key objectives [187]. Nevertheless, its feasibility requires careful management of oxidation by-products, electrode stability, and the handling of highly concentrated streams.

Hybrid EO–membrane systems represent the highest level of integration between oxidation and separation processes, with both occurring simultaneously within a single reactor. In these systems, strong synergistic interactions may arise between electric fields, in situ oxidant generation, and membrane operation. Reported benefits include enhanced fouling control, improved permeation flux, extended membrane lifespan, and reduced system footprint [181,183,188]. The application of an electric field can modify foulant–membrane interactions and promote the in situ degradation of deposited organic matter [188]. Despite these advantages, hybrid systems remain less technologically mature than sequential configurations. Their performance is highly sensitive to operational parameters, and scale-up is challenged by reactor design complexity and the need for precise process control [189]. As a result, they are currently most attractive for niche applications requiring process intensification or compact treatment units rather than immediate large-scale deployment.

Overall, no single EO–membrane configuration can be considered universally optimal. Sequential configurations are presently more mature and flexible, allowing EO and membrane processes to be strategically positioned within multi-step treatment trains according to wastewater composition and treatment objectives. EO pretreatment is most effective for highly colored and organic-rich effluents where fouling mitigation is critical, whereas membrane processes followed by EO are better suited for saline wastewaters and concentrate management in water reuse and MLD/ZLD schemes. Hybrid systems, while promising, require further development to overcome scale-up and operational challenges. A consolidated comparison of the main characteristics, advantages, limitations, and energy-related aspects of the three configurations is provided in Table 6, offering a framework for selecting the most appropriate EO–membrane integration strategy for specific TWW treatment scenarios.

Table 6.

Comparative overview of the main characteristics, advantages, limitations, and energy-related aspects of EO–membrane integration strategies.

6. Patents and Industrial Perspectives on EO–Membrane Technologies Applicable to TWW Treatment

In addition to scientific literature, patent documents provide an important perspective on the technological maturity and industrial relevance of wastewater treatment processes. Particularly for TWW, patents demonstrate that both electrochemical processes and membrane-based technologies have been independently developed and protected for industrial applications, while a smaller but growing number of patents address their integration within hybrid treatment schemes. Together, these patents reflect the progressive transition from standalone technologies toward more integrated solutions capable of addressing the complexity and variability of textile effluents. Table 7 summarizes representative examples of patents related to electrochemical processes, membrane technologies, and hybrid systems applicable to TWW treatment.

Table 7.

Summary of patents related to electrochemical, membrane, and hybrid processes applicable to TWW treatment.

Devices and methods based on EO have been proposed for degrading organic pollutants in wastewater streams, including recalcitrant compounds. For example, US20220033288A1 [190] describes an electrochemical purification device applicable to industrial wastewaters, highlighting compact electrolysis cells capable of oxidizing organic contaminants. Although not exclusively targeted at TWW, the technology’s ability to degrade difficult pollutants via electrochemical reactions demonstrates its applicability to textile effluents with persistent colorants and auxiliary chemicals.

Membrane technologies are among the most widely patented approaches for industrial wastewater treatment. These processes provide effective separation of suspended solids, high-molecular-weight compounds, and salts, serving as a polishing step after primary treatment. EP3898532B1 [191] explicitly targets wastewater treatment in the textile industry, proposing a treatment scheme that includes membrane filtration stages to improve effluent quality and enable reuse. This patent confirms that membrane processes are considered industrially viable and adaptable to the complex composition of TWW. Additional patents, such as BR112019020040B1 [192], describe advanced membrane filtration approaches for industrial effluents in general. While not limited to TWW, such inventions are directly applicable to textile wastewater due to similarities in pollutant profiles and operational challenges. These patents underline the established role of membranes as core technologies in industrial wastewater management and water reuse schemes.

A smaller but growing number of patents propose hybrid systems that combine electrochemical processes and membrane separation. These patents aim to exploit the complementary advantages of EO and membrane filtration, particularly for effluent polishing and reuse. A representative example is WO2012089102A1 [193], which discloses a recycling apparatus for printing and dyeing wastewater that integrates nano-catalytic electrolysis with submerged ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis membranes. This system is explicitly designed for industrial textile applications, demonstrating how hybrid electro-chemical–membrane configurations can enhance treatment performance and address water reuse demands. Another relevant example is WO2023170711A1 [194], which describes a wastewater treatment system that incorporates electrochemical processes with membrane separation. Although the patent is framed broadly for wastewater treatment, its fundamental principles, including membrane-assisted EO, are directly applicable to high-strength industrial effluents like TWW.

While standalone electrochemical and membrane technologies have achieved industrial maturity, hybrid inventions are increasingly emerging, reflecting the industry’s pursuit of integrated solutions that tackle a broader range of pollutants. From an industrial perspective, the trend towards hybrid systems indicates a recognition that combining oxidative degradation (via electrochemistry) and selective separation (via membranes) can offer improved performance for complex effluents such as those arising from textile processing.

7. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Perspectives of EO–Membrane Systems for TWW Treatment

The analysis conducted in this review demonstrates that the effectiveness of TWW treatment cannot be assessed solely based on organic pollutant removal. Although EO is highly effective in degrading recalcitrant organic compounds and reducing color, it does not address salinity, which represents a key constraint for water reuse. In this context, membrane technologies, particularly NF, RO, and MD, are currently the only viable options for efficiently removing dissolved salts, thereby enabling the reuse of treated effluents within textile production systems. The integration of EO and membrane processes, therefore, emerges not only as a strategy to enhance overall treatment efficiency but also as an enabling pathway for water reuse by simultaneously controlling organic load, color, fouling propensity, and salinity. At the same time, the reviewed studies highlight important limitations related to energy demand, retentate management, and scalability, which must be addressed to ensure industrial feasibility. These findings provide the basis for the following discussion of the main strengths, current limitations, and future research perspectives of EO–membrane systems.

7.1. Strengths and Major Findings

Combined and hybrid systems involving EO and membrane processes represent an innovative and promising approach for TWW treatment. EO applied alone typically achieves high color removals (often exceeding 80–90%) and moderate COD reduction, generally ranging from 50% to 80%, depending on electrode material and operating conditions. In contrast, membrane processes used as standalone units mainly act as physical separation and polishing steps, with limited capability to degrade dissolved organic matter and high susceptibility to fouling when treating raw TWW.

The integration of EO with membrane processes offers clear advantages over the standalone application of each technology for TWW treatment. Across the reported studies, EO–membrane systems consistently demonstrate enhanced removal of color, organic matter, suspended solids, and specific recalcitrant pollutants, while simultaneously improving water reuse potential. EO contributes to the degradation and transformation of complex organic compounds, thereby reducing fouling propensity and enhancing membrane performance, while membranes provide effective physical separation, salt rejection, and polishing of treated effluents [195]. In many cases, integrated systems achieve near-complete color removal, COD reductions exceeding 80–95%, and substantial fouling mitigation compared to standalone membrane filtration or EO treatment. These synergistic effects underline the added value of process integration rather than simple process succession.

Furthermore, EO–membrane systems exhibit high adaptability to variable TWW compositions, enabling tailored treatment strategies for different textile operations such as dyeing, washing, and finishing. “One-pot” hybrid configurations are particularly promising, as they integrate oxidation and separation within a single unit, offering improved fouling control, reduced operational complexity, and compact design, which are particularly attractive for space-limited or decentralized applications.

EO–membrane systems support advanced water management strategies, including MLD/ZLD, enabling high water recovery rates and reducing the environmental footprint of TWW disposal. Although most studies on EO–membrane processes have focused on pollutant removal efficiency, water reuse has emerged as a key technological goal and a strategic opportunity for water sustainability in the textile industry. Almost all wet-processing stages require large water volumes, and system-based analyses enable the identification of high-consumption stages and potential cross-reuse between processes. Studies have shown that low-contaminant streams, such as rinse waters, can be reused directly in subsequent operations, reducing both freshwater consumption and effluent generation [196]. Advanced EO–membrane systems are essential to ensure safe and efficient reuse, while also supporting strategies to minimize effluent discharge and promote sustainable water management.

7.2. Limitations and Current Challenges

Despite their demonstrated potential, EO–membrane systems still face several technical, economic, and operational challenges that currently limit their large-scale implementation in TWW treatment. One of the primary constraints is the relatively high installation and operational costs associated with advanced electrode materials, membrane modules, and, in particular, hybrid or highly integrated reactor configurations. These costs are often compounded by substantial energy demand, especially when EO is applied to large wastewater volumes or low-conductivity streams.

Energy efficiency remains a critical issue for both EO and membrane-based processes. In EO, inappropriate selection of current density, electrode material, or treatment time can significantly increase energy consumption, potentially offsetting the benefits of pollutant degradation and fouling mitigation. Similarly, pressure-driven membrane processes such as NF and RO are inherently energy-intensive, while thermally driven processes such as MD require efficient heat management and, ideally, heat recovery strategies to remain viable. As a result, optimizing the balance between treatment performance and energy demand remains a central challenge for integrated EO–membrane systems.

From an operational standpoint, membrane fouling and, in the case of MD, membrane wetting continue to limit long-term performance and system reliability. The deposition of organic matter, salts, and dye-metal complexes can reduce permeate flux, alter selectivity, and increase cleaning frequency, thereby shortening membrane lifespan. At the same time, the formation of oxidation by-products during EO, particularly in chloride-rich TWW, raises concerns regarding permeate quality, secondary fouling, and compatibility with downstream reuse applications, requiring careful control of operating conditions.

“One-pot” hybrid configurations, although promising due to their strong synergistic effects, introduce additional challenges related to system complexity and operational robustness. These configurations are often highly sensitive to operating parameters and may exhibit reduced stability under fluctuating wastewater compositions typical of industrial TWW. Furthermore, membrane durability under prolonged electrochemical exposure and electrode lifetime under realistic industrial conditions remain insufficiently understood and require further investigation [197,198].

Concentrate management also represents a persistent challenge, particularly for configurations involving NF, RO, or MD. The generated retentates are enriched in salts, organic compounds, and, in some cases, metals, and therefore require appropriate treatment, controlled discharge, or valorization strategies to avoid secondary environmental impacts.

Finally, the scalability and industrial adaptation of EO–membrane systems remain limited by the predominance of laboratory- and pilot-scale studies. Scaling up requires optimized reactor design, careful membrane selection, robust control of operational parameters, and system integration capable of accommodating fluctuations in wastewater composition. These challenges are further compounded by the heterogeneity of operational conditions and performance metrics reported in the literature, which complicates direct comparison between studies and hinders comprehensive techno-economic assessment. In particular, quantitative and consistently reported data on specific energy consumption, operational costs, and long-term system stability are still scarce, underscoring the need for more standardized evaluation frameworks and long-term industrial case studies.

7.3. Future Perspectives and Scale-Up Considerations

To enable the transition of EO–membrane systems from laboratory and pilot-scale studies to full industrial implementation, several technical, economic, and operational aspects must be systematically addressed. Process design should increasingly move toward modular and scalable configurations, such as stacked electrochemical cells coupled with standardized membrane modules. This approach would allow flexible capacity expansion, simplified maintenance, and easier adaptation to variable wastewater flows and compositions typical of textile operations.

Energy optimization remains a central requirement for large-scale feasibility. This includes the selection of high-efficiency and durable electrode materials, optimization of electrode spacing and current density, and preferential application of EO to high-conductivity streams, such as membrane concentrates, where electrochemical efficiency is inherently higher. The integration of renewable energy sources, energy recovery strategies, or intermittent operation modes aligned with renewable power availability may further improve economic and environmental performance.

Long-term pilot-scale demonstrations under real industrial conditions are essential to bridge the gap between laboratory performance and practical application. Such studies should evaluate system robustness under fluctuating TWW characteristics, fouling behavior, electrode and membrane lifespan, cleaning requirements, and operational stability. These experimental efforts must be complemented by comprehensive techno-economic analyses and life cycle assessments to identify key cost drivers, quantify environmental trade-offs, and support informed decision-making for industrial deployment.

Beyond individual unit operations, future research should increasingly focus on the integration of EO–membrane systems within complete treatment trains rather than as isolated processes. This systems-level perspective is particularly relevant for MLD/ZLD schemes, where EO–membrane technologies can be combined with biological treatment, other advanced oxidation processes, or resource recovery strategies. The valorization of membrane concentrates through the recovery and reuse of salts, dyes, or chemicals represents a promising pathway toward circular water management and improved economic viability [199,200,201].

Further progress toward industrial implementation will depend on targeted research addressing material performance, process optimization, and long-term sustainability. Priority areas include the development of low-cost and durable electrodes with controlled by-product formation, membranes with enhanced fouling resistance and selectivity, advanced modeling and control strategies for real-time optimization, and integrated water reuse schemes tailored to different textile operations (e.g., washing, dyeing, cooling). Together, these advances will be critical to translating the demonstrated potential of EO–membrane systems into reliable, scalable, and economically viable solutions for sustainable TWW management.

Author Contributions

M.E.: Investigation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. C.A.: Investigation. B.S.: Investigation. D.V.: Writing—Review & Editing. A.F.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, FCT, through Projects UID/00195/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00195/2025 (accessed on 6 January 2026)), and UID/PRR/195/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00195/2025 (accessed on 6 January 2026)); PhD grant PRT/BD/154710/2023 (M. Espinosa); and research contract CEECINST/00016/2021/CP2828/CT0006 awarded to A. Fernandes under the scope of the CEEC Institutional 2021 (https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECINST/00016/2021/CP2828/CT0006 (accessed on 6 January 2026)).

Data Availability Statement

As this is a review article, no new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful for the support granted by the Research Unit of Fiber Materials and Environmental Technologies (FibEnTech-UBI), through the Projects references UID/00195/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00195/2025 (accessed on 6 January 2026)) and UID/PRR/195/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00195/2025 (accessed on 6 January 2026)), funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP/MECI. The authors would like to thank European Alliance UNITA (101004082—UNITA—EAC-A02-2019/EAC-A02-2019-1 & 101124853—UNITA—ERASMUS-EDU-2023-EUR-UNIV) for its support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BDD | Boron-doped diamond |

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| DSA | Dimensionally stable anode |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| EC | Electrocoagulation |

| EC1 | 1European Commission |

| ED | Electrodialysis |

| EO | Electrooxidation |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FO | Forward osmosis |

| HC | Hydrodynamic cavitation |

| HFMBR | Hollow fiber membrane bioreactor |

| MD | Membrane distillation |

| MEO | Membrane electrooxidation |

| MER | Membrane electrochemical reactor |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MLD | Minimum liquid discharge |

| MMO | Mixed metal oxide |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PC | Peroxi-coagulation |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PSf | Polysulfone |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| Ref. | Reference |

| RO | Reverse osmosis |

| ROC | Reverse osmosis concentrate |

| TAN | Total ammonia nitrogen |

| TDS | Total dissolved solids |

| TKN | Total Kjeldahl nitrogen |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TSS | Total suspended solids |

| TWW | Textile wastewater |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| ZDHC | Zero discharge of hazardous chemicals |

| ZLD | Zero liquid discharge |

References

- EU Reporter, The Impact of Textile Production and Waste on the Environment (Infographics) 2020. Available online: https://www.eureporter.co/environment/2020/12/29/the-impact-of-textile-production-and-waste-on-the-environment/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Kifetew, M.; Alemayehu, E.; Fito, J.; Worku, Z.; Prabhu, S.V.; Lennartz, B. Adsorptive Removal of Reactive Yellow 145 Dye from Textile Industry Effluent Using Teff Straw Activated Carbon: Optimization Using Central Composite Design. Water 2023, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holme, I. Sir William Henry Perkin: A Review of His Life, Work and Legacy. Color. Technol. 2006, 122, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, M.; Nosenzo, G.; Capannelli, G.; Ciabatti, I.; Corrieri, D.; Ciardelli, G. Treatment and Reuse of Textile Effluents Based on New Ultrafiltration and Other Membrane Technologies. Desalination 2001, 138, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast Fashion: EU Laws for Sustainable Textile Consumption 2025. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20201208STO93327/fast-fashion-eu-laws-for-sustainable-textile-consumption (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chi, M.; Eygen, G.V.; Guan, K.; Matsuyama, H. Comprehensive Review of Nanofiltration Membranes for Efficient Resource Recovery from Textile Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R. Textile Dyeing Industry an Environmental Hazard. Nat. Sci. 2012, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanaw, A.; Birlie, B.; Teshome, B.; Jemberie, M. Textile Effluent Treatment Methods and Eco-Friendly Resolution of Textile Wastewater. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisschops, I.; Spanjers, H. Literature Review on Textile Wastewater Characterisation. Environ. Technol. 2003, 24, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terinte, N.; Manda, B.M.K.; Taylor, J.; Schuster, K.C.; Patel, M.K. Environmental Assessment of Coloured Fabrics and Opportunities for Value Creation: Spin-Dyeing versus Conventional Dyeing of Modal Fabrics. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammayappan, L.; Jose, S.; Arputha Raj, A. Sustainable Production Processes in Textile Dyeing. In Green Fashion; Muthu, S.S., Gardetti, M.A., Eds.; Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 185–216. ISBN 978-981-10-0109-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Textile Dye Wastewater Characteristics and Constituents of Synthetic Effluents: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, S.; Soni, V. Classification and Impact of Synthetic Textile Dyes on Aquatic Flora: A Review. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 45, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, C.; Grant, S.; Johnson, L.; McGee, K.; Powell, C. Water Efficiency Manual for Commercial, Industrial and Institutional Facilities. 2009. Available online: https://resources4business.info/assets/docs/WaterEfficiencyManual.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Verma, A.K.; Dash, R.R.; Bhunia, P. A Review on Chemical Coagulation/Flocculation Technologies for Removal of Colour from Textile Wastewaters. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 93, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkar, C.R.; Jadhav, A.J.; Pinjari, D.V.; Mahamuni, N.M.; Pandit, A.B. A Critical Review on Textile Wastewater Treatments: Possible Approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Z.; Zhao, Y.G. Advanced Treatment of Dyeing Wastewater for Reuse. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 39, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.; McMullan, G.; Marchant, R.; Nigam, P. Remediation of Dyes in Textile Effluent: A Critical Review on Current Treatment Technologies with a Proposed Alternative. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 77, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, R.; Purchase, D.; Saratale, G.D.; Saratale, R.G.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Bilal, M.; Chandra, R.; Bharagava, R.N. Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Persistent Coloring Pollutants of Textile Industry Wastewater and Treatment Approaches for Environmental Safety. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Williams, C.J.; Edyvean, R.G.J. Treatment of Tannery Wastewater by Chemical Coagulation. Desalination 2004, 164, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najari, S.; Delnavaz, M.; Bahrami, D. Application of Electrocoagulation Process for the Treatment of Reactive Blue 19 Synthetic Wastewater: Evaluation of Different Operation Conditions and Financial Analysis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 832, 140897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Sustainable Disposal of Fenton Sludge and Enhanced Organics Degradation Based on Dissimilatory Iron Reduction in the Hydrolytic Acidification Process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Li, S.; Yi, F.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Huang, Y. Enhancement of photo-Fenton catalytic activity with the assistance of oxalic acid on the kaolin−FeOOH system for the degradation of organic dyes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 18704–18714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, K.; Ozturkcan, S.A. Decolorization and Degradation of Reactive Dye in Aqueous Solution by Ozonation in a Semi-Batch Bubble Column Reactor. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.N.; Ghosh, P.C.; Vaidya, A.N.; Mudliar, S.N. Catalytic Ozone Pretreatment of Complex Textile Effluent Using Fe2+ and Zero Valent Iron Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 357, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.; Sayed, M.; Khan, J.A.; Shah, N.S.; Khan, H.M.; Dionysiou, D.D. Oxidative Removal of Brilliant Green by UV/S2O82−, UV/HSO5− and UV/H2O2 Processes in Aqueous Media: A Comparative Study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 357, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcanjo, G.S.; Mounteer, A.H.; Bellato, C.R.; Silva, L.M.M.D.; Brant Dias, S.H.; Silva, P.R.D. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis Using TiO2 Modified with Hydrotalcite and Iron Oxide under UV–Visible Irradiation for Color and Toxicity Reduction in Secondary Textile Mill Effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 211, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaili, F.; Hasheminejad, H.; Zarean Mousaabadi, K. Investigating Textile Wastewater Treatment by Electro-Fenton Method with Fe-MIL-88(A) Catalyst Composited with Graphene Oxide. Water Resour. Ind. 2025, 34, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Fernandes, A.; Marques, A.; Ciríaco, L.; Miguel, R.A.L.; Lopes, A.; Pacheco, M.J. Reuse of Wool Dyeing Wastewater after Electrochemical Treatment at a BDD Anode. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Rančev, S.; Velinov, N.; Vučić, M.R.; Antonijević, M.; Nikolić, G.; Bojić, A. Triclinic ZnMoO4 catalyst for atmospheric pressure non-thermal pulsating corona plasma degradation of reactive dye; role of the catalyst in plasma degradation process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 269, 118748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Kostić, M.; Rančev, S.; Radivojević, D.; Vučić, M.R.; Hurt, A.; Bojić, A. Co-doped ZnO catalyst for non-thermal atmospheric pressure pulsating corona plasma degradation of reactive dye. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Guo, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. In Situ Coupling of Electrochemical Oxidation and Membrane Filtration Processes for Simultaneous Decontamination and Membrane Fouling Mitigation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 290, 120918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; He, Z. Formation and Control of Oxidation Byproducts in Electrochemical Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, E.S.; Ali, H.; Abdel-Karim, A. Efficient and Reusable Polyethylene Oxide/Polyaniline Composite Membrane for Dye Adsorption and Filtration. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2020, 39, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, A.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Radwan, E.K.; Mohamed, I.M.; Azaam, M.; Kenawy, E.-R. High-Performance Mixed-Matrix Membranes Enabled by Organically/Inorganic Modified Montmorillonite for the Treatment of Hazardous Textile Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, A.; Ismail, S.H.; Bayoumy, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.; Mohamed, G.G. Antifouling PES/Cu@Fe3O4 Mixed Matrix Membranes: Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling and Wastewater Treatment Potentiality. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, Y.; Li, Y. Degradation of C.I. Reactive Blue 19 Using Combined Iron Scrap Process and Coagulation/Flocculation by a Novel Al(OH)3–Polyacrylamide Hybrid Polymer. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2012, 43, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.H.; Karimi, B.; Rajaei, M.S. The Effect of Aeration on Advanced Coagulation, Flotation and Advanced Oxidation Processes for Color Removal from Wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 223, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, N.B.; Kechaou, N.; Palmeri, J.; Deratani, A.; Sghaier, A. Comparison of Tertiary Treatment by Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis for Water Reuse in Denim Textile Industry. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 170, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colla, V.; Branca, T.A.; Rosito, F.; Lucca, C.; Vivas, B.P.; Delmiro, V.M. Sustainable Reverse Osmosis Application for Wastewater Treatment in the Steel Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 130, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; Al-Zghoul, T.M.; Darwish, M.M. A Comprehensive Review of Combined Processes for Olive Mill Wastewater Treatments. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, O.; Zielinska, M.; Zubrowska-Sudol, M. Enhancing Wastewater Treatment Efficiency: A Hybrid Technology Perspective with Energy-Saving Strategies. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 399, 130593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebron, Y.A.R.; Moreira, V.R.; Maia, A.; Couto, C.F.; Moravia, W.G.; Amaral, M.C.S. Integrated Photo-Fenton and Membrane-Based Techniques for Textile Effluent Reclamation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 272, 118932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, H.A.; Akbal, F. Enhancing Textile Wastewater Reuse: Integrating Fenton Oxidation with Membrane Filtration. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 379, 124873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Decontamination of Wastewaters Containing Synthetic Organic Dyes by Electrochemical Methods. An Updated Review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166–167, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Sousa, A.; Fernandes, A.; Pastorinho, R.; Pacheco, M.; Ciríaco, L.; Lopes, A. Understanding the Efficiency of Electrochemical Oxidation in Toxicity Removal. In Advances in Chemistry Research; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–66. ISBN 978-1-5361-6519-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, C.; Fernandes, A.; Lopes, A.; Nunes, M.J.; Baía, A.; Ciríaco, L.; Pacheco, M.J. Reuse of Textile Dyeing Wastewater Treated by Electrooxidation. Water 2022, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arévalo, C.M.; García-Suarez, L.; Camilleri-Rumbau, M.S.; Vogel, J.; Álvarez-Blanco, S.; Cuartas-Uribe, B.; Vincent-Vela, M.C. Treatment of Industrial Textile Wastewater by Means of Forward Osmosis Aiming to Recover Dyes and Clean Water. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, N.R.; Huang, R.; Du, E.; Peng, M.; Pan, Z.; Ding, H.; Shan, G.; Ling, L.; Xie, Z. A Review of the Textile Wastewater Treatment Technologies with Special Focus on Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), Membrane Separation and Integrated AOP-Membrane Processes. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 206, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Shahid-ul-Islam; Mohammad, F. Recent Advancements in Natural Dye Applications: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuza, L.; Sonnenberg, N.; Marx-Pienaar, N. Natural versus Synthetic Dyes: Consumers’ Understanding of Apparel Coloration and Their Willingness to Adopt Sustainable Alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 18, 200146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A Critical Review on the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater: Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Textile Dyes and Possible Remediation Approaches for Environmental Safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]