Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most significant anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG), accounting for approximately 81% of total emissions, with methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases contributing the remainder. Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations, driven primarily by fossil fuel combustion, industrial processes, and transportation, have surpassed the Earth’s natural sequestration capacity, intensifying climate change impacts. Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) offers a portfolio of solutions to mitigate these emissions, encompassing pre-combustion, post-combustion, oxy-fuel combustion, and direct air capture (DAC) technologies. This review synthesizes advancements in CO2 capture materials including liquid absorbents (amines, amino acids, ionic liquids, hydroxides/carbonates), solid adsorbents (metal–organic frameworks, zeolites, carbon-based materials, metal oxides), hybrid sorbents, and emerging hydrogel-based systems and their integration with utilization and storage routes. Special emphasis is given to CO2 mineralization using mine tailings, steel slag, fly ash, and bauxite residue, as well as biological mineralization employing carbonic anhydrase (CA) immobilized in hydrogels. The techno-economic performance of these pathways is compared, highlighting that while high-capacity sorbents offer scalability, hydrogels and biomineralization excel in low-temperature regeneration and integration with waste valorization. Challenges remain in cost reduction, material stability under industrial flue gas conditions, and integration with renewable energy systems. The review concludes that hybrid, cross-technology CCUS configurations combining complementary capture, utilization, and storage strategies will be essential to meeting 2030 and 2050 climate targets.

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are the primary driver of climate change, with CO2 contributing approximately 80% of total emissions, followed by CH4 (11%), N2O (6%), and fluorinated gases (3%) based on US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [1]. These gases trap heat in the atmosphere, intensifying global warming, ozone depletion, and ecological imbalance. Fossil fuel combustion, industrial activities, and transportation are the dominant CO2 sources [2,3], with coal, oil, and natural gas accounting for ~93% of fossil-based emissions in 2022. Temporary reductions in emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the scale of the impact of human activity on atmospheric CO2 but did not alter long-term upward trends. By 2024, global average surface temperatures reached 1.55 °C above pre-industrial levels for the first time [4].

Mitigating these impacts requires large-scale deployment of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) technologies [5,6]. CCUS encompasses capture from point sources (pre-combustion, post-combustion, oxy-fuel combustion) [7,8,9,10] and from ambient air via Direct Air Capture (DAC) [11,12]. Captured CO2 can be utilized in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) [13], converted to fuels, chemicals, or polymers [14,15], or permanently stored through geological injection [16,17,18,19] and mineralization [20,21].

Recent material science advances have expanded the CCUS toolbox to include mature absorbents such as amines [22,23,24], environmentally benign amino acids [25,26], high-surface-area adsorbents like metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [27,28,29], zeolites [30,31], carbon-based materials [32,33], and thermally stable metal oxides [34,35,36]. Hybrid sorbents such as MOF-amine slurries [37,38] and graphene-MOF composites [39,40] combine complementary strengths.

A notable emerging class are hydrogel-based sorbents, including carbonic anhydrase (CA)-immobilized systems, which enable low-temperature regeneration and integration with biomineralization pathways [41,42,43,44,45]. Hydrogels provide tunable porosity, high water content, and compatibility with 3D printing [46,47], making them promising for niche applications such as DAC or low-temperature point source capture powered by waste heat or solar thermal energy.

This review presents a comprehensive assessment of CCUS technologies, materials, and integration strategies, with a focus on emerging hydrogel–enzyme systems and mineralization of industrial residues, supported by comparative techno-economic and life-cycle perspectives.

2. Carbon Capture Technologies

CO2 capture technologies can be broadly categorized into two main types: (1) Point Source Capture (PSC) and (2) Direct Air Capture (DAC).

2.1. Point Source Capture (PSC)

There are three primary methods for capturing CO2 at the source of emissions commonly referred to as point source capture namely pre-combustion capture, post-combustion capture, and oxy-fuel combustion. These technologies are designed to reduce CO2 emissions from power plants, industrial processes, and other emission sources [48], with each approach addressing the carbon emission challenge in a distinct way.

Pre-combustion capture commonly applied in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) power plants involves capturing CO2 before fossil fuel combustion [49,50]. In this process, the fuel is first converted into synthesis gas (syngas) composed of hydrogen and CO2, typically through gasification. The CO2 is then separated from the hydrogen before combustion. The hydrogen can be used as a clean fuel, while the captured CO2 is directed toward storage or utilization [10].

Post-combustion capture involves removing CO2 after the combustion of fossil fuels (such as coal, natural gas, or oil) in a power plant or industrial facility. In conventional combustion, fuels are burned in air, producing flue gas containing CO2, nitrogen (N2), water vapor (H2O), and other gases [51]. Post-combustion capture systems separate CO2 from this flue gas stream using methods such as chemical absorption most commonly with amine-based solvents that selectively absorb CO2 or solid sorbent-based systems that capture CO2 via physisorption or chemisorption [52]. Once captured, CO2 can be transported and stored underground, converted into chemical products, or incorporated into construction materials, thereby preventing its release into the atmosphere and reducing its contribution to climate change.

Oxy-fuel combustion involves burning fossil fuels in a mixture of pure oxygen and recycled flue gases rather than regular air [53,54]. Under oxygen-enriched conditions, combustion produces a flue gas composed primarily of water vapor and CO2, simplifying the separation and capture of CO2 [55]. The exclusion of nitrogen normally present in air reduces flue gas volume and increases CO2 concentration, thereby improving capture efficiency. This technology is considered a promising option for CCS, particularly in industrial applications where a reliable supply of high-purity oxygen is available.

Each of these carbon capture approaches has specific advantages and limitations. Current research focuses on improving their performance and reducing costs to enhance their role in mitigating CO2 emissions from various sources.

2.2. Direct Air Capture (DAC)

While point source capture technologies are increasingly implemented across industrial sectors to capture CO2 at emission sites, there remains a critical need to address surplus atmospheric CO2 in both the short and long term. Unlike PSC methods, DAC technology can extract CO2 directly from ambient air at any location [11].

However, this innovative approach faces significant challenges, particularly the difficulty of capturing the trace concentrations of CO2 present in the atmosphere [12]. Recent advances in materials development for CO2 adsorption indicate that porous materials particularly carbon-based sorbents and metal oxides offer promising, cost-effective solutions. Carbon-based materials are attractive due to their low-cost precursors, simple synthesis methods, and tunable textural properties, while metal oxides are abundant, affordable, and exhibit low toxicity [56].

3. Carbon Capture Materials

In broad terms, materials capable of capturing CO2 can be categorized into three types: (1) absorbents, (2) adsorbents, and (3) hybrid sorbents.

3.1. Absorbents

CO2 molecules can be dissolved in various media, typically liquids and, in some cases, solids. The principal carbon-capturing absorbents include amines, hydroxides, ionic liquids, amino acids, and carbonates [57,58,59,60]. Among these, amine-based absorbents are the most widely utilized in current capture technologies.

Aqueous amine systems, such as monoethanolamine (MEA), represent the most mature form of CO2 capture and have been in industrial use for over 90 years. Historically, these systems were applied in the purification of natural gas and hydrogen, as well as in the production of beverage-grade CO2, before being adopted for flue gas treatment.

The mechanism of CO2 absorption using amines involves chemisorption, in which covalent bonds form between the nitrogen atom in the amine and the carbon atom of the CO2 molecule [60,61]. In large-scale industrial processes, flue gas containing CO2 is introduced into an absorber column at relatively low temperatures, where the CO2 is captured by a counter-flowing aqueous amine solvent. The CO2-rich solvent is then transferred to a stripping column, where it is heated to release the absorbed CO2 and regenerate the solvent for reuse.

Despite the technological maturity of the process, amine-based absorption has several limitations. The strong chemical bonding between CO2 and the amine requires high energy input for regeneration due to the high heat of reaction. Additionally, the large heat capacity of the solvent results in significant energy consumption, thereby increasing operational costs. Furthermore, the corrosive nature of the solvent accelerates equipment degradation. Collectively, these factors elevate the overall cost of the process, particularly the operational expenditure [62,63].

Amino acids and their salts have emerged as promising absorbents for CO2 capture due to their low volatility, biodegradability, and resistance to oxidative degradation, offering advantages over conventional amines in terms of environmental impact and solvent stability. They absorb CO2 via a mechanism like amines, where the amino group reacts with CO2 to form carbamates or bicarbonates, but the presence of the carboxylate group in amino acids enhances buffering capacity and mitigates solvent degradation. Commonly studied systems include sodium glycinate, potassium glycinate, and taurine, which exhibit high CO2 loading capacities (often exceeding 0.8–1.0 mol CO2/mol amino acid in aqueous solutions) and good regeneration characteristics. Compared to MEA, amino acid salts generally show lower vapor pressure, reducing solvent loss and emissions, and improved tolerance to oxygen and flue gas impurities. Furthermore, their tunable structure allows optimization for faster absorption of kinetics or lower regeneration energy. However, challenges remain in terms of higher solution viscosity at high loadings and potential precipitation issues, which require process adjustments such as blending with other absorbents or using biphasic solvent systems. These properties position amino acids and their salts as viable candidates for both post-combustion and pre-combustion CO2 capture applications, particularly where solvent stability and environmental compatibility are priorities [64].

3.2. Adsorbents

CO2 molecules can adhere to the surface of a solid adsorbent or, in some cases, a liquid adsorbent through the process of adsorption [62]. In contrast to absorption, where the absorbate (e.g., CO2) dissolves throughout the entire volume of the absorbent, adsorption is a surface phenomenon in which the adsorbate forms a layer or film on the surface of the adsorbent.

In its simplest form, adsorption of CO2 by a porous solid occurs via physisorption, where CO2 molecules attach to the extensive surface area of the adsorbent through weak Van der Waals intermolecular forces. However, studies have shown that many solid sorbents exhibit a combination of physisorption and chemisorption during CO2 capture. This has led to the broader and more inclusive use of the term “solid sorbents”. Although the term “solid adsorbents” is still widely used, both terms are often applied interchangeably in current literature and research.

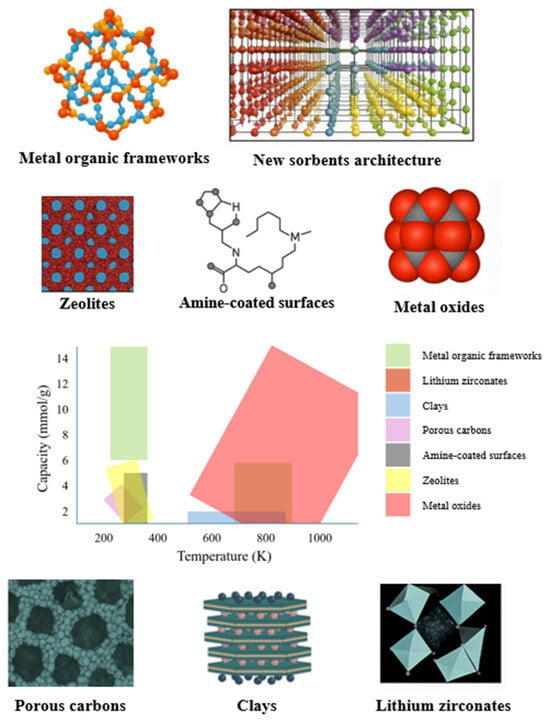

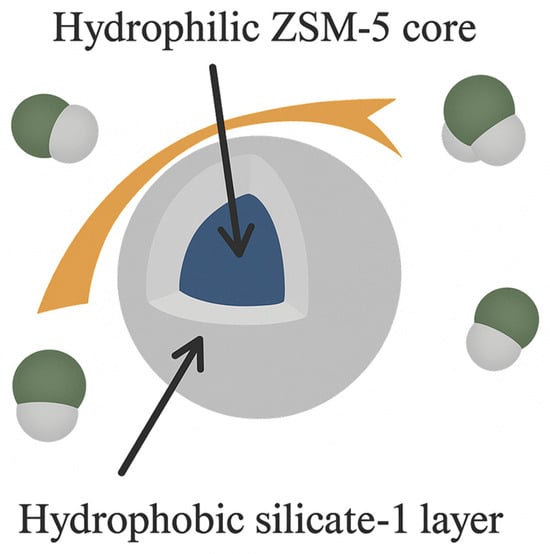

As shown in Figure 1, the CO2 capture performance of various sorbents varies with temperature, highlighting the influence of material type and operational conditions on adsorption efficiency. Solid sorbents are typically characterized by their high surface area and hierarchical porous structures, which generally include (i) micropores (<2 nm), (ii) mesopores (2–50 nm), and (iii) macropores (>50 nm).

For pristine porous carbons under ambient conditions (T ≈ 0–25 °C and p ≤ 1 bar), adsorption primarily occurs via a volume-filling process in micropores smaller than 0.8 nm. This is attributed to the molecular size of CO2 (0.33 nm) [65]. Under these conditions, larger pores (>0.8 nm) contribute minimally to adsorption. At elevated pressures approaching saturation (35 bar at 0 °C or 64 bar at 25 °C) adsorption capacity increases significantly due to the activation of supermicropores (0.8–2 nm), which enable a coverage adsorption mechanism [66].

When the bulk structure of a solid sorbent inherently contains or is modified to include functional groups or active sites with a high affinity for CO2, chemisorption can also play a significant role in the capture process. Distinguishing the individual contributions of physisorption and chemisorption to the total CO2 uptake is challenging, although such values have been reported for specific materials [52].

The main classes of solid adsorbents include MOFs, metal oxides, zeolites, carbon-based materials, silica, and alumina [65,67] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CO2 capture performance of different sorbents at varying temperatures (adapted from [68]).

3.2.1. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

MOFs are a category of crystalline, porous materials that have attracted significant attention as potential adsorbents for CO2 capture. These materials consist of metal-containing clusters linked by organic connectors, creating a framework with tunable void spaces that can effectively trap CO2 molecules. MOFs exhibit exceptional properties for gas capture, including surface areas of up to 7000 m2/g the highest reported for any material to date [69]. Their structural tunability, variable pore sizes, and chemical diversity further enhance their potential for selective CO2 capture [70].

Despite these advantages, MOFs face several challenges, including low selectivity for CO2 over other gases such as H2O and N2, reduced stability in humid and harsh conditions, and high production costs. Consequently, significant research efforts have been directed toward improving their performance and economic viability. These strategies include (i) pore and structure engineering, where fine-tuning pore size and geometry by selecting specific metal clusters and organic linkers, introducing hierarchical porosity, incorporating specific heteroatoms, and designing coordinatively unsaturated metal sites with tailored functional groups to improve selectivity [71]. (ii) Surface modification is coating or functionalizing MOFs with hydrophobic agents to enhance water resistance and improve stability in humid environments [63,72,73]. (iii) Cost reduction and scalability for developing low-cost, scalable production processes to make MOFs an economically viable option for industrial applications [74]. (iv) Computational designing, simulations and artificial intelligence to design, screen, and discover new MOFs with enhanced CO2 capture properties [29,63].

Modifications can be implemented at various stages of synthesis, including pre-synthetic, in situ, and post-synthetic stages [73]. Post-synthetic modification (PSM) methods include ligand exchange, metal exchange, pore character alteration, surface texturing and functionalization, and covalent or dative modifications to improve MOF properties after synthesis [75].

The final stage in MOF synthesis is activation, during which guest molecules (e.g., solvents or residual chemicals) are removed from the framework without compromising its structural integrity or porosity. This step is crucial, as it can greatly impact adsorption performance. Mondloch et al. [76] identified five main activation strategies includes conventional heating under vacuum [77], solvent exchange [78], supercritical CO2 processing [79], freeze-drying [80,81], and chemical treatment [82], with some studies combining these methods [83,84].

Other PSM approaches involve chemical reactions between introduced reactants (liquid or gaseous) and the internal MOF components, such as organic linkers or metal nodes. Plasma treatment has also been employed for pore etching, surface texturing, doping, and functionalization [63,72]. Less commonly, solid–solid reactions have been used to achieve PSM objectives [85].

While MOFs hold strong potential for CO2 capture, industrial-scale commercialization is still limited. A notable example is Svante, a Canada-based company that has developed proprietary MOF formulations to extract CO2 from industrial flue gas streams, achieving purities above 95% suitable for geological storage or utilization. Svante operates a range of pilot and commercial projects with capacities from 35 tonnes/year to 10,000 tonnes/year, targeting emissions from cement kilns, natural gas-fired boilers, and DAC systems [86].

3.2.2. Zeolites

Zeolites are aluminosilicate-based materials that occur naturally and can also be synthesized commercially. They are systematically classified using a standardized three-letter framework type code system, such as ABW (double crankshaft chains of tetrahedra, forming one-dimensional channels), IFO (interconnected cages and channels with medium pore openings), and JOZ (three-dimensional network with 8-ring channels). As of 2023, the International Zeolite Association has identified and coded 246 different zeolite structures [87].

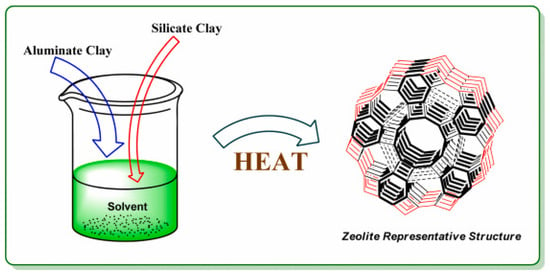

Laboratory synthesis often involves combining alumite clay and silicate clay in specific ratios at controlled temperatures to produce the desired zeolite framework (Figure 2). Their microporous and crystalline structures make zeolites highly effective adsorbents for gas separation and purification (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The use of alumite clay and silicate clay in specific ratio at a certain temperature to synthesize zeolites (adapted with permission from Ref. [30]. 2021, Monalisa Mukherjee and Vivek Mishra).

Figure 3.

Different adsorbents and their CO2 capacity (adapted with permission from Ref. [30]. 2021, Monalisa Mukherjee and Vivek Mishra).

Zeolites with pore diameters in the range of 0.3–1.0 nm exhibit significant CO2 capture capacity through the molecular sieving effect, given that the kinetic diameter of a CO2 molecule is approximately 0.33 nm [65]. Additionally, due to their high quadrupole moment, CO2 molecules are strongly attracted to the electric field generated by the structural cations within the zeolite framework [88,89]. Studies have shown that CO2 adsorption capacity in zeolites increases with larger surface area and pore volume which enhance molecular sieving and with higher sodium content, which strengthens the electric field.

However, CO2 adsorption performance decreases with rising flue gas temperature and lower CO2 partial pressure, prompting extensive research into methods for improving the adsorption properties of zeolites. One approach is amine impregnation, which increases the basicity of the zeolite at low loading levels and enhances CO2 affinity. Excessive amine loading, however, can block pores and reduce performance. Another strategy is cation exchange, in which alkali and alkaline earth metals (e.g., Li, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Ba, and Cs) are introduced to improve adsorption characteristics.

Recent literature [30] reports multiple approaches to re-engineering zeolites, including (i) synthesizing zeolites from sustainable precursors and processes; (ii) fabricating complex hierarchical zeolite geometries via 3D printing; (iii) modifying zeolites by fusing alkali metals into their frameworks; (iv) producing natural polymer–zeolite composite materials; and (v) developing hybrid composites that combine zeolites with other sorbents.

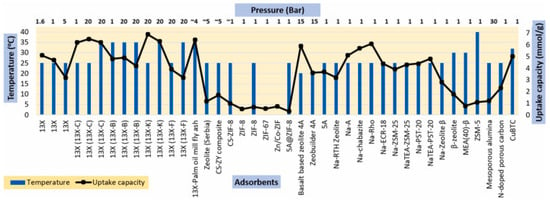

Like many solid sorbents, zeolites face challenges in selectively capturing CO2 over other flue gas constituents such as N2, O2, CH4, and, in particular, water vapor. A proven solution is coating hydrophilic zeolites with a porous hydrophobic shell, which repels H2O molecules while allowing CO2 molecules to penetrate and be adsorbed by the hydrophilic core (Figure 4). Examples include zeolite 5A coated with a hydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) [89] and aluminosilicate ZSM-5 coated with its hydrophobic siliceous form, silicalite-1 [31].

Figure 4.

Core-shell structure with hydrophilic ZSM-5 core and hydrophobic silicate-1 shell (adapted from [90]).

3.2.3. Carbon-Based Materials

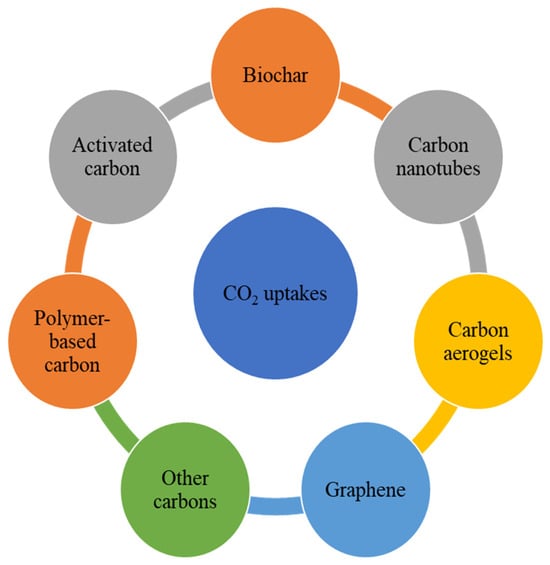

Carbon-based materials are generally more stable than MOFs and zeolites in humid, corrosive, and high-temperature flue gas environments, making them an attractive choice for industrial CO2 adsorption [65,91,92]. These materials also offer tunable textural properties, high specific surface area and pore volume, and low regeneration energy requirements. The main types of carbon-based sorbents include activated carbon, biochar, graphene, carbon nanotubes, polymer-based carbons, carbon aerogels, and carbons derived from various precursors (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Carbon materials for CO2 capture.

Adsorption processes in carbon-based materials are primarily governed by van der Waals forces (between CO2 molecules and pore surfaces) and/or electrostatic or Coulomb interactions (between CO2 molecules and impurities or dopants) [93,94]. These interactions are relatively weak and tend to dissociate at elevated temperatures. This thermal sensitivity can be advantageous for CO2 desorption, as it results in low regeneration energy requirements. However, it also limits adsorption efficiency because CO2 uptake decreases with increasing flue gas temperatures.

Recent research has focused on enhancing the CO2 capture capacity and selectivity of carbon-based sorbents by optimizing surface area, pore structure, and surface chemistry. Improvements in textural properties have been achieved through the careful selection of precursors, modification of synthesis conditions, and the application of physical or chemical activation methods, as well as various post-treatment processes [95]. Studies have shown that micropore volume has a greater impact on CO2 adsorption than total specific surface area.

Enhancement of surface chemistry [32] has been accomplished through several strategies, including (i) heteroatom doping with elements such as nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, which introduces negatively charged sites on the carbon surface to strengthen Coulombic attraction with acidic CO2 molecules [96,97,98]. (ii) Incorporation of amine functional groups, enabling acid–base interactions with CO2 [99]. (iii) Impregnation of carbon surfaces with metal oxides, which can further improve CO2 adsorption capacity [33].

3.2.4. Metal Oxides

The adsorption of CO2 on metal oxides occurs primarily through chemisorption, in which acidic CO2 molecules form strong bonds with the basic sites of the metal oxides. Due to their high thermal stability, metal oxides are suitable for CO2 capture from high-temperature flue gases (up to ~750 °C).

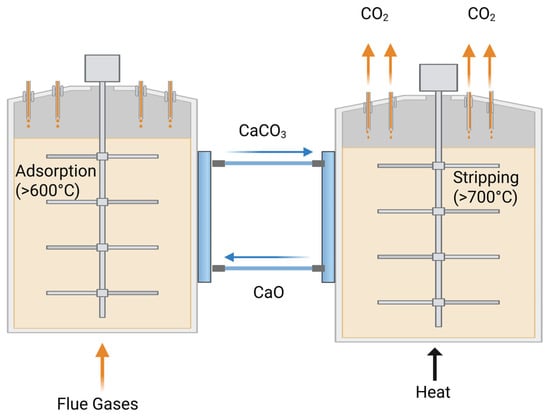

The most widely studied and applied metal oxides for carbon capture are magnesium oxide (MgO) and calcium oxide (CaO), owing to their low cost, natural abundance, and scalability [100,101,102]. Pure MgO exhibits a relatively low CO2 adsorption capacity (up to ~2 wt%) and adsorbs/desorbs CO2 at lower temperatures (200 °C for adsorption and ~375 °C for desorption) compared to pure CaO, which can achieve up to 78 wt% capacity but requires higher adsorption (>600 °C) and desorption (>700 °C) temperatures.

MgO is more stable over multiple adsorption–regeneration cycles, whereas CaO suffers from a rapid decline in adsorption capacity during repeated carbonation (CaO + CO2 → CaCO3) and calcination (CaCO3 → CaO + CO2) cycles. This cyclic process, known as calcium looping (Figure 6), represents the reversible transformation between CaO and CaCO3 during high-temperature adsorption and regeneration.

Figure 6.

Calcium looping process for CO2 capture using CaO/CaCO3 at high temperatures during adsorption and stripping cycles.

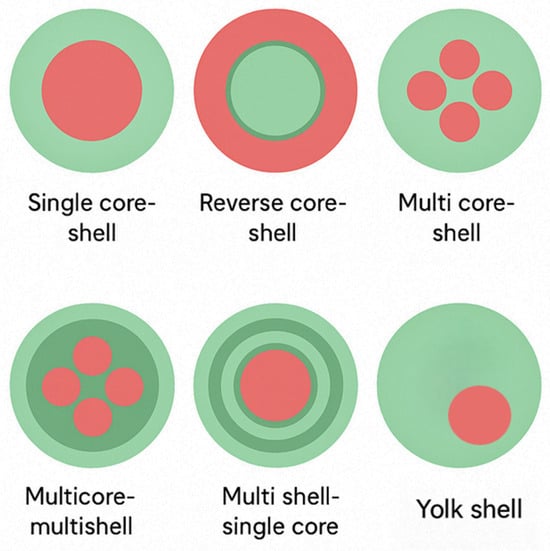

The loss of capacity in CaO is mainly attributed to two phenomena: (i) sintering effect at high temperature that closes some of the available pores and (ii) formation of a layer of CaCO3 that inhibits the penetration of CO2 to the core of particles [102]. Recent research has focused on improving the CO2 adsorption properties of CaO and MgO through several strategies: (i) Forming binary CaO-MgO metal oxides, where MgO inhibits the sintering of CaO, thereby improving its structural stability [103]. (ii) Modifying CaO and MgO with other metal oxides such as La2O3 and Al2O3, which act as stabilizers at high temperatures to reduce sintering or enhance chemisorption performance. (iii) Producing nanopowders and/or mesoporous particles with increased surface area, larger pore volume, and more active sites to boost CO2 uptake [36,104]. (iv) Engineering faceted metal oxides dominated by the crystallographic plane, which offers a higher density of low-coordination sites favorable for CO2 adsorption [100]. (v) Incorporating CaO and MgO into core–shell nanoparticle (CSN) architectures, either as the core or the shell, to optimize structure–property relationships for enhanced CO2 sorption [35]. As illustrated in Figure 7, various CSN designs are being explored to maximize adsorption efficiency.

Figure 7.

Types of core-shell nanoparticle architectures.

Other metal oxides have also been investigated for CO2 capture. For example, Li2O exhibits good reactivity but is expensive and unstable, which restricts its use to specialized applications such as controlling CO2 concentrations in spacecraft and submarines. Al2O3, on the other hand, has a very low CO2 sorption capacity (<5%) and is therefore often modified with other metal oxides such as CaO, MgO, or Na2O to improve its adsorption performance [35,105].

3.3. Hybrid Sorbents

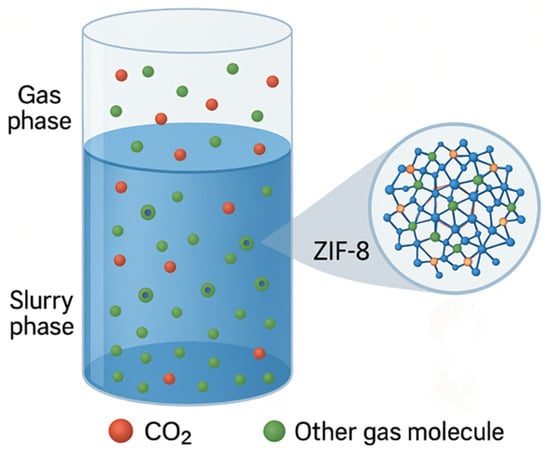

3.3.1. Absorbent-Adsorbent

This class of hybrid sorbents consists of slurries in which solid adsorbent particles are suspended in a liquid absorbent. For example, slurries of MOF particles in an amine-based solution can provide a hybrid solid-adsorption/liquid-absorption capture process, as illustrated in Figure 8 [106]. In such systems, MOFs are selected or engineered to have pores small enough to prevent saturation by the liquid absorbent molecules, yet large enough to allow CO2 molecules to diffuse in and be adsorbed.

Figure 8.

Hybrid absorption-adsorption process (adapted from [107]).

3.3.2. Adsorbent-Adsorbent

These composite materials combine multiple classes of solid sorbents to integrate the advantages of each and enhance overall carbon capture performance. One example is the combination of graphene oxide (GO) with zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), a subgroup of zeolite-like MOFs [107]. By varying the concentration of GO, researchers were able to control the growth, size, and shape of ZIF-8 nanocrystals. At a GO content of 20 wt%, the resulting hybrid composite (ZG-20) exhibited an exceptionally high CO2 uptake of 72 wt%, attributed to the synergistic benefits of the zeolitic MOF and graphene oxide.

3.3.3. Hydrogel-Based Material

Among various CO2 capture technologies, amine scrubbing remains the most established method, particularly for separating CO2 from natural gas and hydrogen, and has been in use since its introduction in the 1930s [108]. Despite its industrial applicability, amine scrubbing has several limitations, including high energy requirements for solvent regeneration, relatively low absorption capacity, and equipment corrosion during long-term operation [23,109]. In addition, the technique demonstrates reduced performance at low CO2 concentrations and presents challenges related to solvent recyclability.

To address these issues, recent research has focused on incorporating amine solutions such as MEA and diethanolamine (DEA) into hydrogel matrices [110,111]. Hydrogels are three-dimensional polymer networks that are highly porous and hydrophilic, capable of absorbing and retaining substantial amounts of fluid. These crosslinked structures can be engineered to respond to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature, and light. Due to their resemblance to the natural extracellular matrix (ECM), hydrogels have been widely investigated in regenerative medicine and are now gaining significant attention for their potential in CO2 capture technologies [112,113]. Their tunable physicochemical properties, high liquid retention capacity, and functional surface chemistry make them attractive candidates for gas sorption applications.

Hydrogel synthesis has advanced through methods such as chemical and physical cross-linking, nanoparticle incorporation, double-network formation, and reinforcement with natural or synthetic polymers. The chemical composition and polymer matrix selected significantly influence the sorption characteristics.

In a study by Choi et al. [43], macroporous hydrogel particles were developed using hyperbranched poly(amidoamine)s (HPAMAM) via an oil-in-water-in-oil (O/W/O) suspension polymerization method. These hydrogels demonstrated a CO2 uptake capacity of 104 mg·g−1 and exhibited rapid absorption in packed-column experiments. Their high capture efficiency was attributed to the incorporation of amine groups within the hydrogel matrix, which enhanced CO2 binding affinity, resulting in performance comparable to that of advanced solid adsorbents. The simplicity and scalability of this synthesis process support its potential for industrial application [43].

White et al. [41] developed cross-linked poly (N-2-hydroxyethylacrylamide) (PHEAA) hydrogels loaded with DEA, which achieved CO2 uptake values of 7.82 wt% for pure CO2 and 2.90 wt% for direct air capture (DAC). The study also demonstrated that modifying the solvent system such as replacing water with ethylene glycol increased uptake to 5.59 wt%. These hydrogels exhibited thermal stability and maintained amine retention over multiple cycles, supporting their feasibility for continuous operation [41].

Guo et al. [42] introduced sustainable carbon capture hydrogels (SCCH) with a CO2 uptake capacity of 3.6 mmol·g−1 under ambient conditions (400 ppm CO2). Comprising konjac glucomannan and hydroxypropyl cellulose with embedded polyethylenimine, these hydrogels featured a hierarchically porous structure that enhanced CO2 diffusion and binding. Under humid conditions (40–70% relative humidity), water adsorption promoted hydronium carbamate formation, increasing uptake to approximately 4.5 mmol·g−1 across CO2 concentrations ranging from 10,000 to 150,000 ppm. The thermoresponsive nature of hydroxypropyl cellulose enabled effective CO2 release within 50 min at 60 °C, allowing regeneration via solar or low-power heating. Furthermore, the hydrogel matrix prevented polyethylenimine aggregation and degradation, ensuring stable sorption performance over repeated cycles [42,114].

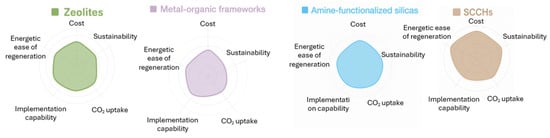

As shown in Figure 9, these developments align with the core requirements for practical CO2 capture materials high uptake capacity, operational stability, and scalability making hydrogel-based amine systems a promising avenue for next-generation carbon capture technologies. Table 1 shows the Comparative Performance of CO2 Capture Materials.

Figure 9.

Key properties of materials for effective carbon capture.

Table 1.

Comparative Performance of CO2 Capture Materials.

4. CO2 Utilization and Storage Pathways

Carbon dioxide capture must be complemented by effective utilization and/or storage routes to achieve meaningful climate mitigation. Broadly, CO2 utilization and storage pathways can be classified into (i) direct utilization, where CO2 is used without permanent storage; (ii) chemical and biological conversion, where CO2 is transformed into value-added products; and (iii) permanent storage, where CO2 is immobilized in geological or mineral forms.

Direct utilization includes applications such as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), enhanced geothermal systems, food and beverage carbonation, and use in greenhouses to promote plant growth [118]. While these markets are relatively small (<0.5% of global CO2 emissions), they can provide early revenue streams to support capture infrastructure. Chemical utilization/Chemical conversion transforms CO2 into fuels, chemicals, and materials. Synthetic fuels (methanol, methane, syngas) via catalytic hydrogenation [15]. Polycarbonates via reaction with epoxides to produce plastics and resins [119]. Mineral carbonation to produce stable carbonates for construction [20]. Electrochemical reduction to form CO, formic acid, or hydrocarbons using renewable electricity [120]. The techno-economics of methanol synthesis from CO2 and renewable hydrogen show production costs of $610–640 t−1 methanol at renewable H2 costs of $2.0 kg−1, with break-even economics requiring hydrogen prices below $0.77–0.95 kg−1 to match conventional methanol market prices of $380 t−1 [121].

In biological utilization, biological pathways use microalgae, cyanobacteria, or engineered microbes to convert CO2 into biomass, biofuels, or specialty chemicals [122]. Algae cultivation can achieve high areal productivity (>20 g m−2 day−1) but faces scalability challenges related to land, water, and nutrient inputs. Geological storage involves injecting CO2 into deep saline aquifers, depleted oil and gas reservoirs, or unmineable coal seams [123]. This approach offers gigaton-scale capacity with demonstrated permanence. Monitoring, verification, and long-term liability remain critical considerations. Injection costs typically range from $10–20 tCO2−1 depending on site location and depth (details in Section 4).

Mineralization/biomineralization converts CO2 into solid carbonates via reaction with alkaline minerals or industrial wastes (e.g., steel slag, mine tailings). Biomineralization uses biological catalysts such as carbonic anhydrase (CA) to accelerate carbonate formation under mild conditions. This approach can be integrated into construction materials, providing both CO2 storage and material performance benefits (details in Section 5).

4.1. Geological Storage of CO2

Geological storage is the most mature and large-scale option for permanent CO2 sequestration, with a global technical capacity estimated in the hundreds to thousands of gigatonnes (GtCO2) [16,17,123]. In this approach, CO2 is injected into suitable deep geological formations, where it is securely trapped through a combination of structural, residual, solubility, and mineral mechanisms. The primary storage types include (i) deep saline aquifers, which offer the largest global potential of approximately 1000–10,000 GtCO2 [16,18] and are exemplified by the Sleipner Project in Norway, which has been storing around 1 MtCO2 annually since 1996 [19]; (ii) depleted oil and gas reservoirs, which have proven caprock integrity and are often coupled with enhanced oil recovery (EOR) for added economic benefit, as demonstrated by the Weyburn-Midale project in Canada that has stored over 30 MtCO2 since 2000 [124,125,126,127,128]; and (iii) unmineable coal seams, where CO2 adsorption displaces methane in enhanced coal bed methane recovery (ECBM) operations, such as the RECOPOL pilot project in Poland [129]. Despite its promise, geological storage entails key risks, including leakage through faults, fractures, or legacy wells, induced seismicity from injection-related pressure changes [130,131,132], and brine migration into potable aquifers. These risks can be mitigated through comprehensive site characterization and geomechanical modeling, rigorous well integrity testing using corrosion-resistant casing and cement, careful pressure management via controlled injection rates or brine extraction, and the deployment of redundant injection infrastructure to ensure operational resilience. Long-term containment also requires continuous monitoring to detect anomalies early and maintain public confidence, employing subsurface techniques such as 4D seismic imaging to track plume migration, downhole pressure, temperature, and geochemical sensors; near-surface methods such as soil gas surveys and atmospheric sampling; and remote sensing tools like satellite-based InSAR to detect surface deformation [133]. The regulatory landscape plays a critical role in ensuring operational safety, environmental protection, and public trust: in the United States, EPA Underground Injection Control (UIC) Class VI regulations mandate multi-casing well designs, corrosion-resistant cement, and post-closure monitoring for 50 years; in Canada, both provincial and federal frameworks are informed by the North American Carbon Storage Atlas [126,127]; and internationally, instruments such as the EU CCS Directive (2009/31/EC) [134] and ISO 27914:2017 [135] set global best practices for site selection, monitoring, and closure. Deploying CCS at scale will require substantial infrastructure and material resources according to the NETL-NZA model, a 2.0 Gtpa CCS system would require 13.7 Mt of monoethanolamine (MEA), 632.1 kt of triethylene glycol (TEG), 24–32 Mt of steel, and 1.1 Mt of cement. This, in turn, would demand approximately 30.78 Mt of iron over 25 years (equivalent to ~3.3% of the U.S. annual production) along with alloying elements such as chromium, nickel, and molybdenum [135,136,137], as well as around 737 kt of lime and 275 kt of silica for cement production [138,139]. Case studies illustrate both the scale and potential of geological storage: in Alberta, Canada, more than $1 billion has been invested in CCUS projects, resulting in the storage of over 7 MtCO2 since 2015, with the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin estimated to hold more than 100 GtCO2 of storage capacity [6,127,140,141,142]; in the United States, strategic planning projects an upper-bound CCS capacity of approximately 2.0 GtCO2 per annum by 2050 [130].

4.2. Biomineralization of CO2

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is a metalloenzyme that plays a crucial role in the hydration of CO2, catalyzing its conversion into carbonate ions. In bacterial systems, CA typically contains zinc as a cofactor at its active site, which facilitates the binding and transformation of CO2 [108]. However, other metal cofactors, such as cadmium and iron, have also been reported in CAs from specific organisms [143,144].

The incorporation of bacteria expressing CA into cementitious materials has shown potential for enhancing CO2 diffusion under carbonation-curing conditions, during which CO2 is converted into carbonate minerals, contributing to its sequestration [131]. This biomineralization process not only promotes carbon capture but can also improve the mechanical performance of the cement matrix. For example, Li et al. [145] reported that incorporating CA from Bacillus mucilaginous into cement led to the complete closure of cracks up to 0.3 mm and significantly reduced the water permeability coefficient of the composite.

Despite these promising results, limited research has been conducted on the influence of bacterial CA on CO2 sequestration efficiency, microstructural changes, and the mechanical properties of cementitious materials.

To date, CAs are known to exist in eight genetically distinct families: α, β, γ, δ, ζ, η, θ, and ι [146]. The α-CAs are the most widely distributed and were the first to be discovered, identified in human blood in the 1930s [147]. These enzymes exhibit diverse oligomeric states, including monomeric, dimeric, and tetrameric structures [148,149]. In addition to humans, α-CAs are present in bacteria, fungi, plants, and algae, where they regulate key physiological functions such as respiration, pH homeostasis, CO2 transport, photosynthesis, and sexual development [150].

The β-CAs, the second most extensively studied group, occur in bacteria, archaea, fungi, some higher plants, and invertebrates. Their quaternary structures may be dimers, tetramers, hexamers, or octamers [151,152,153]. Several fungal species, including Candida spp., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sordaria macrospora, and Aspergillus fumigatus, possess β-CAs, which have been linked to pathogenic mechanisms [150,154]. In bacteria, β-CAs contribute to pH regulation via bicarbonate (HCO3−) transport and may also play roles in virulence [155].

The γ-CAs have a distinctive left-handed parallel β-helix domain and are present in bacteria, archaea, and certain photosynthetic organisms. They typically exist as trimers [156]. In cyanobacteria and archaea, γ-CAs are involved in carbon fixation and ion transport.

The δ and ζ families, though less common, are essential in marine diatoms for carbon-concentrating mechanisms [157,158]. The η-class has so far been identified only in Plasmodium species [159], while the θ and ι classes are found in marine diatoms, algae, and bacteria. θ-CAs, which also contain Zn at the active site, have been associated with promoting photosynthetic activity and growth in diatoms [160]. The ι-class remains poorly characterized, but existing studies indicate that these enzymes can form dimers and, in some cases, incorporate manganese instead of zinc as the active-site metal [161].

4.2.1. Catalytic Role of Carbonic Anhydrase

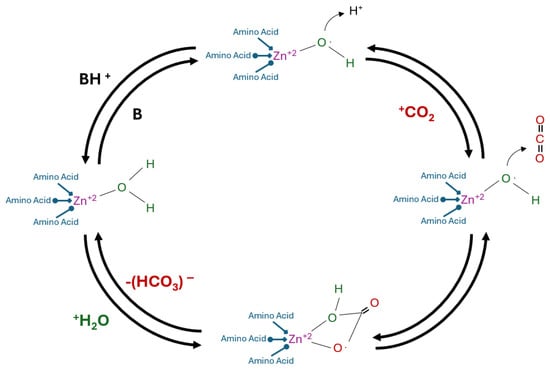

In natural systems, the reversible hydration of CO2 occurs spontaneously but at a relatively slow rate. Carbonic anhydrase (CA) catalyzes this reaction, significantly accelerating the conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate ions. The resulting bicarbonate can subsequently react with metal ions to form metal bicarbonates, as represented by the following reaction pathway:

CO2 (g) + H2O (l) ↔ H2CO3 (aq) ↔ HCO3− (aq) + H+ ↔ CO32− (aq) + 2H+ → CaCO3 (s)

In comparison to the non-catalyzed reaction, which has a catalytic turnover rate of approximately 0.15 s−1, CA can accelerate the process by several orders of magnitude. Reported catalytic efficiency values (kₐₜ/Kₘ) for CA reach up to 108 s−1, representing an enhancement of up to one billion-fold [162]. In α-CAs, for example, the active site contains a metal–water complex that, upon ionization, forms a metal-bound hydroxide with strong nucleophilic character [143,144,145]. This hydroxide ion attracts the incoming CO2 molecule, which reacts to form a metal-coordinated bicarbonate ion. The bicarbonate is then displaced by a water molecule and released into the surrounding solution [163,164].

The rate-limiting step in this catalytic cycle is the regeneration of the metal–hydroxide complex via proton transfer from the newly bound water molecule. This proton transfer is facilitated either by amino acid residues within the enzyme or by buffer molecules in the surrounding solution, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Catalytic Acceleration of CO2 Hydration.

4.2.2. Immobilization of CA Enzymes

The limited stability and reusability of free carbonic anhydrase (CA) have hindered its broader application in industrial processes. To address these limitations, several strategies have been developed, including the isolation of CA from thermophilic organisms, protein engineering to enhance thermal tolerance, and enzyme immobilization [165]. Among these, immobilization has emerged as the most widely used and effective approach for improving the enzyme’s stability, operational lifespan, and reusability. Immobilized CA also enables continuous enzymatic operation and reduces the total enzyme requirement, which is particularly advantageous compared to processes utilizing free CA [166,167].

Various solid supports have been employed for CA immobilization, including polyamide [168], chitosan [169], and alkyl Sepharose [170,171,172]. Among the available techniques, multipoint covalent immobilization where multiple functional groups on the enzyme interact with reactive groups on the support is considered particularly robust and stable [173].

A highly efficient biocatalytic membrane, referred to as CA-m-PVDF, was developed by immobilizing CA onto a polydopamine (PDA)/polyethylenimine (PEI)-modified polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane via glutaraldehyde cross-linking [174]. The optimal configuration of the CA-m-PVDF membrane achieved an enzymatic activity of 498 U m−2 and an activity recovery of 31.5%, using m(5 h)-PVDF as the support, 0.67% (v/v) glutaraldehyde as the cross-linking agent, a CA concentration of 600 μg mL−1, pH 8.0, temperature of 25 °C, and a 24-h reaction period. In a bench-scale gas–liquid membrane contactor (GLMC) setup, using water as the absorbent at a liquid velocity of 0.25 m s−1, the biocatalytic membrane demonstrated a CO2 absorption flux of 2.5 × 10−3 mol m−2 s−1, representing an approximately 165% increase compared to the non-biocatalytic m-PVDF membrane. Long-term stability testing confirmed sustained enzymatic activity for CO2 hydration over a 40-day period. These findings highlight the potential of polymer-supported enzyme immobilization in developing high-performance biocatalytic membranes for CO2 capture in GLMC systems. CA was attached to the surface of a PVDF membrane at a concentration of 210 mg L−1 within a hollow fiber membrane contactor. When operated at a high liquid flow velocity of 0.25 m s−1, the system achieved a total mass transfer coefficient of 6.12 × 10−5 m s−1. This velocity was significantly greater than that used in the current study (0.002 m s−1), and the resulting enhancement in CO2 absorption rate was attributed to the substantial increase in mass transfer efficiency at elevated flow rates [175,176,177].

A novel membrane contactor system was also developed, featuring a hybrid enzymatic CO2 absorption process that utilized flat-sheet membranes embedded with immobilized human carbonic anhydrase II (hCA II) [178]. The contribution of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) was more pronounced at lower enzyme loadings on the membrane surface specifically at 12.0 mg L−1 where CO2 hydration was significantly improved. Reusability was demonstrated through ten consecutive absorption cycles, during which both the biocatalytic membranes and MNPs retained functional activity. The contactor also exhibited operational stability over extended periods.

To gain deeper insight into system performance, a multiscale mathematical model was developed to simulate conditions involving membrane pores filled with gas or partially with liquid. The model predicted that enzymatic activity within wetted regions of the membrane facilitated by CA immobilized in the pores could effectively overcome the associated mass transfer resistance. Additionally, the model indicated that further enhancement in CO2 uptake could be achieved through enzymatic activity in the liquid phase via MNPs. A mass transfer coefficient of 4.40 × 10−5 m s−1 was attained in the wetted regions of the membrane.

4.2.3. Hydrogels as CA Support

Achieving CO2 reduction under ambient conditions is essential for the development of environmentally sustainable technologies. Carbonic anhydrase (CA), a zinc-containing metalloenzyme, catalyzes the hydration of CO2 rapidly and efficiently in aqueous environments under mild and eco-friendly conditions. Owing to their high-water content and hydrophilicity, hydrogels serve as excellent matrices for CA encapsulation.

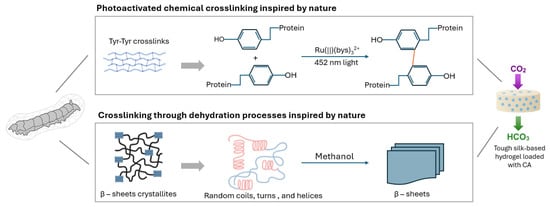

Kim et al. [179] developed a silk fibroin-based hydrogel incorporating CA, termed dc-ngCA-silk, using a bioinspired dual-crosslinking approach. As shown in Figure 11, the hydrogel was synthesized via photo-induced dityrosine chemical crosslinking, followed by dehydration-induced β-sheet physical crosslinking. The resulting material exhibited high mechanical strength, with compressive moduli of approximately 1.3 MPa and 11 MPa at 20% and 40% strain, respectively. This robust structure enabled the efficient sequestration of CO2 as calcium carbonate. Furthermore, the encapsulated CA retained approximately 60% of its enzymatic activity, confirming the functional stability of the biocatalyst within the hydrogel matrix [179].

Figure 11.

Development of a tough and stable silk hydrogel encapsulating CA for efficient CO2 sequestration (adapted from [179]).

Immobilizing carbonic anhydrase (CA) in hydrogel matrices has gained significant attention as a strategy to improve enzyme stability, reusability, and efficiency for CO2 capture applications. Polymeric hydrogels provide an ideal environment for enzyme encapsulation due to their high-water content, porosity, and tunable mechanical properties.

Among these, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate/poly(ethylene oxide) (PEG-DA/PEO) interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels (IPNHs) have been fabricated into both one-dimensional filaments and two-dimensional grids [180]. The one-dimensional filaments demonstrated strong mechanical performance, with an average tensile strength of 6.5 MPa and a break elongation of 80%. The two-dimensional grid-like networks were rolled into spiral configurations, making them suitable for use in structured packing systems. These interpenetrating nanohybrid structures provided a stable platform for CA immobilization.

Although higher enzyme loadings resulted in reduced activity recovery, heavily loaded samples still retained over 87% of their enzymatic activity after 150 days of repeated use. CO2 capture efficiency increased proportionally with enzyme concentration, and extended operation under continuous solvent recycling conditions (lasting 1032 h) maintained 52% of the original CO2 capture capacity and preserved 34% of the enzyme’s functional contribution. In addition to gas separation, these materials show promise for 3D printing, biosensing, and biocatalysis applications.

Other hydrogel systems have also demonstrated potential for CA immobilization. Zhang et al. [181] synthesized poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide)/hydrotalcite (PAA-AAm/HT) nanocomposite hydrogels via intercalation polymerization, using sodium methyl allyl sulfonate as the intercalation agent. The immobilized CA retained 85.2–90.9% of the activity of free enzyme, depending on the hydrotalcite variant. Notably, enzyme activity remained stable at 4 °C for one month, with no apparent degradation, attributed to the formation of a water-rich microenvironment within the hydrogel network. However, this material was effective only for removing trace amounts of CO2 and was not suitable for higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

Ren et al. [182] reported the preparation of composite hydrogels by embedding CA within MOFs (CA@ZIF-8) and subsequently incorporating them into poly(vinyl alcohol)–chitosan (PVA/CS) hydrogel matrices. The resulting PVA/CS/CA@ZIF-8 composites exhibited high CA immobilization efficiency (>70%) and superior resistance to high temperatures, denaturants, and acidic conditions. These membranes outperformed both free CA and CA@ZIF-8 in CO2 sequestration, producing 20-fold and 1.63-fold more calcium carbonate, respectively. Furthermore, they retained 50% of their original enzymatic activity after 11 reuse cycles, whereas CA@ZIF-8 alone lost activity entirely.

4.2.4. CO2 Contained-3D Printed Hydrogels

3D printing technology is a specialized subclass of additive manufacturing that involves the layer-by-layer fusion and deposition of materials to create three-dimensional (3D) objects from digital designs [183]. This approach enables precise control over the architecture and composition of materials, such as hydrogels, potentially reducing production costs and allowing for the fabrication of customized, high-efficiency carbon capture materials [184].

The process begins with the computer-aided design (CAD) of a 3D model, which is then converted into a stereolithography (STL) file and subsequently sliced into printable layers using specialized software. These layer files are fed into the 3D printing system to produce the final object. The object is formed by sequentially building each two-dimensional layer on top of the preceding one.

A wide range of precursor materials can be used in 3D printing, including metals, polymers, and hydrogels. The selection of an appropriate starting material is critical, as it determines the overall performance, quality, and functionality of the printed part.

Hydrogels are particularly promising for 3D printing due to their tunable physicochemical properties, high porosity, and excellent water retention capacity. These attributes have led to their widespread application in biomedical engineering, regenerative medicine, electronic devices, and, more recently, CO2 capture [185]. Their high porosity and water content maximize the contact area between the hydrogel and CO2, enhancing absorption efficiency. Furthermore, hydrogels can be tailored and functionalized with amine groups or other CO2-absorbing compounds, enabling chemical binding with CO2 molecules and thereby improving capture performance [186,187].

4.2.5. Techno-Economic Outlook for CA-Immobilized Hydrogel

Hydrogel-based sorbents incorporating carbonic anhydrase (CA) achieve high CO2 capture efficiencies (≥90% removal) in clean, simulated gas streams. Industrial flue gases, however, present a more complex challenge. These streams typically contain SOₓ (SO2 and SO3), NOₓ (NO and NO2), water vapor, particulates, and oxygen—introducing multiple degradation pathways that threaten commercial viability.

Thermal stress poses the primary concern. Absorber conditions (40 °C in alkaline media) cause gradual enzyme activity loss and leaching from the chitosan matrix [44]. This emphasizes the need for more durable immobilization strategies. Additionally, reactive oxygen species generated within hydrogel networks can alter enzyme activity and induce structural changes in the polymer matrix [188,189]. Temperature effects compound these issues. Flue gas streams operate at 40–75 °C, influencing both sorbent performance and structural integrity [96]. Repeated thermal cycling creates physical stress in porous matrices, potentially compromising long-term stability. Meanwhile, particulate fouling reduces CO2 mass transfer rates [190].

Despite immobilization efforts, carbonic anhydrase activity inevitably declines. Solvent exposure, thermal stress, and repeated washing cycles all contribute to gradual enzyme deactivation [44].

Mitigation strategies to address these issues include upstream SOₓ/NOₓ scrubbing, embedding pH-buffering agents in the hydrogel matrix, selecting acid-resistant crosslinking chemistries, using engineered CA variants with enhanced thermal and oxidative stability. These measures are critical to extend functional lifetimes and reduce replacement frequency, directly impacting operating costs. From a techno-economic perspective, CA-hydrogel systems remain at an early technology readiness level (TRL) (3–5). In a pilot-scale amine-based CO2 capture system using 30 wt% MEA, the regeneration energy was measured at 3.92 GJ per ton of CO2 removed under optimized condition [191]. Process modeling suggests that with Enzyme cost reductions, operational stability of ≥6–12 months, Regeneration energies below ~2 GJ tCO2−1, the levelized cost of capture could fall into the $40–90 tCO2−1 range [192]. This aligns with current policy-relevant incentives such as the U.S. 45Q credit ($50–100 tCO2−1).

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) indicates that systems powered by renewable electricity and using recyclable hydrogel matrices could achieve net CO2 abatement efficiencies > 85% [193]. However, if powered by fossil-based energy without upstream CCS, net abatement may drop below 50%, undermining competitiveness.

In comparative techno-economic context, hydrogels offer low-temperature regeneration (<60 °C) and biocatalytic acceleration via CA, making them attractive for Direct Air Capture (DAC) or low-temperature point-source capture where waste heat or solar thermal can be used. Against amine-grafted silicas or MOFs, hydrogels have lower volumetric capacities but potentially lower regeneration penalties and integration potential with biomineralization and waste valorization processes. This positions CA-hydrogel systems as complementary rather than replacement technologies, best suited for niche applications where their tunability, mild operating conditions, and hybrid capture–utilization integration provide an advantage.

In summary, CA-immobilized hydrogel CCUS systems hold significant promise, but targeted material and process innovations are required to withstand realistic flue gas environments and achieve the durability and cost targets necessary to meet or outperform the current $50–100 tCO2−1 policy benchmarks. Table 2 compares key performance indicators of hydrogels with those of other advanced sorbents and biomineralization systems. This highlights that while volumetric capacity is lower than for MOFs or high-surface-area carbons, hydrogels offer low-temperature regeneration and unique integration potential with biological mineralization pathways, supporting their role as complementary rather than replacement technologies.

Table 2.

Comparative Techno-Economic Performance of Selected CO2 Capture Materials.

5. Carbon Mineralization Potential of Industrials Wastes

Concrete is the most widely used construction material globally, with annual production exceeding 10 billion tonnes [194,195]. This growing demand is driven by rapid population growth and the corresponding need for infrastructure development. However, the continuous extraction of raw materials required for concrete production has led to the depletion of natural resources and a subsequent increase in material costs [196]. As a result, the construction industry faces the urgent challenge of adopting more sustainable practices.

Global trends are increasingly focused on the recovery and reuse of materials from waste streams, as well as the integration of waste-derived materials as alternative raw inputs in construction. The uncontrolled disposal of large volumes of untreated waste significantly contributes to environmental degradation such as polluting land, air, and water and poses serious threats to biodiversity [197]. At the same time, climate change remains a pressing global concern, requiring immediate action in emissions-intensive sectors such as construction.

Mining and industrial wastes such as mafic and ultramafic tailings, fly ash, iron and steel slag, bauxite residue, and concrete debris have shown considerable potential for carbon capture due to their high silicate content. These materials can serve as partial replacements for cement in concrete production, offering both environmental and economic benefits. Recent advances have led to the development of concrete formulations that incorporate recycled construction waste and captured industrial CO2 emissions, presenting a promising strategy to reduce the environmental impact of mining and construction. Moreover, these waste-derived materials are being explored for use in 3D printing of concrete structures.

However, widespread adoption remains limited, primarily due to a lack of comprehensive understanding of the physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of these alternative materials. Addressing these knowledge gaps will be essential to enable their effective and large-scale integration into sustainable construction practices.

5.1. Mafic and Ultramafic Tailings

Mafic and ultramafic deposits are important sources of economically valuable metals, including nickel, cobalt, and copper, and are estimated to account for approximately 7% of the global annual metal production value [198]. In light of increasingly stringent environmental regulations and growing market incentives to reduce carbon emissions, these lower-grade deposits are attracting renewed interest. Their potential to produce carbon-neutral products and generate revenue through carbon credit systems further enhances their economic viability.

Mafic tailings are generated from the processing of mafic rocks, which commonly contain minerals such as pyroxenes, amphiboles, and plagioclase feldspars [199]. Although they may contain some metal sulfides, their concentrations are generally lower than those in ultramafic tailings. Mafic rocks typically have higher silica content and lower magnesium and iron levels compared to ultramafic rocks, resulting in a reduced CO2 carbonation potential. Nevertheless, these tailings often contain secondary phases such as iron oxides (FeO), which can react with CO2 to form stable iron carbonates like siderite (FeCO3), thereby contributing to carbon sequestration [200].

Ultramafic rocks generally contain high concentrations of MgO, sometimes up to 50% along with significant amounts of iron and comparatively low silica content relative to mafic rocks. Magnesium silicates are often preferred for mineral carbonation due to their high abundance, while calcium oxide is usually present at lower levels (around 10%). The silicate minerals in ultramafic rocks occur in structural forms such as nesosilicates, phyllosilicates, and inosilicates. Olivine, a common nesosilicate, exists along a compositional range between forsterite (magnesium-rich) and fayalite (iron-rich). Other minerals such as pyroxene and clinopyroxene are also common in ultramafic rocks and have demonstrated strong potential for CO2 sequestration via mineral carbonation [201].

These tailings may additionally contain valuable accessory minerals such as chromite (FeCr2O4), nickel-bearing phases, and metal sulfides including pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8). Ultramafic rocks frequently undergo serpentinization, a hydrothermal alteration process that converts primary silicate minerals—such as olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4) and pyroxene ((Ca,Mg,Fe)Si2O6) into secondary phases including serpentine ((Mg,Fe,Ni)3Si2O5(OH)4) and brucite (Mg(OH)2). This transformation occurs under suitable pressure–temperature conditions in the presence of water. The extent of serpentinization directly influences the mineralogical distribution of magnesium, iron, and nickel within the deposit and plays a critical role in determining its CO2 carbonation potential.

5.2. Serpentine Minerals

Serpentine minerals occur in three polymorphic forms: chrysotile, lizardite, and antigorite. Among these, chrysotile has a fibrous structure and is classified as an asbestos-type mineral. When airborne, chrysotile fibers pose serious health risks and have been linked to respiratory diseases such as asbestosis, mesothelioma, and lung cancer [202]. Due to these hazards, the handling and processing of serpentine-rich tailings require strict safety protocols and trained personnel. Before being used in bioprocessing or carbon storage applications, asbestos-containing materials should be treated with strong acids to remove hazardous components.

Serpentines, brucite, olivine, and other ultramafic minerals containing divalent metals are generally regarded as gangue and are discarded into tailings storage areas, where they may undergo natural mineral carbonation [203,204]. The extent of serpentinization is a critical factor in evaluating the carbonation potential of ultramafic deposits, as it determines the brucite content. Brucite is highly reactive and plays a key role in the rapid mineralization of CO2 [205].

5.3. Fly Ash

Fly ash is recognized as a promising reactive feedstock for CO2 mineral carbonation due to its favorable chemical and mineralogical composition. Globally, approximately 750 million tonnes of coal fly ash are generated each year [206], with the highest producers being China (395 Mt/year), the United States (118 Mt/year), India (105 Mt/year), Europe (52.6 Mt/year), and Africa (31.1 Mt/year). Fly ash is a byproduct of coal or other fossil fuel combustion in thermal power plants. It consists of fine particulate matter and is considered one of the most chemically and physically complex industrial waste materials.

Chemically, fly ash can be represented within the SiO2-Al2O3-MeO system, where MeO refers to oxides of alkali metals (Na2O, K2O), alkaline-earth metals (CaO, MgO), and transition metals (MnO, ZnO) [207]. The primary components are silica (SiO2), alumina (Al2O3), and iron oxides (Fe2O3), with notable amounts of calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), potassium (K), and trace elements such as arsenic (As), boron (B), mercury (Hg), cobalt (Co), selenium (Se), strontium (Sr), and chromium (Cr) also present [208]. The pH of fly ash varies widely from 1.2 to 12.5, but most samples are alkaline. This variability is influenced largely by the Ca/S molar ratio and other minor alkali or alkaline earth constituents.

Fly ash is classified into two main categories based on oxide content, (i) Class F fly ash contains more than 70 wt% combined SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, with less than 10% CaO. It is typically derived from higher-rank coals (e.g., bituminous or anthracite). Calcium is mainly present as Ca(OH)2, CaSO4, or within amorphous aluminosilicate glass. (ii) Class C fly ash contains 50–70 wt% combined SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, along with a higher CaO content (12–25%). It is usually produced from lower-rank coals (e.g., subbituminous or lignite) and has elevated alkali and sulfate (SO42−) levels. Its higher CaO content imparts self-cementing properties, allowing it to harden in the presence of water without additional cementitious materials [209].

The alkaline nature of fly ash is particularly because of its CaO content which makes it well-suited for CO2 sequestration via mineral carbonation, forming stable carbonate phases that permanently prevent CO2 re-release into the atmosphere.

Several studies have explored both direct and indirect carbonation of fly ash under various process conditions. For example, Revathy et al. [210] evaluated CO2 capture using Class F fly ash through aqueous mineral carbonation under flue gas conditions. Under optimal conditions of temperature 61.6 °C, pressure 48.7 bar, liquid-to-solid ratio 13.35, and reaction time 50 min, CO2 concentration was reduced by approximately 23%. The maximum CO2 sequestration achieved was 50.72 g CO2/kg for aqueous carbonation and 20.03 g CO2/kg for gas–solid carbonation.

Key process parameters varied in importance depending on the carbonation route: temperature and pressure were critical for gas–solid carbonation, while temperature and liquid-to-solid ratio had the greatest influence in aqueous carbonation. Mineralogical analysis of the fly ash revealed major crystalline phases such as mullite (Al2O3·SiO2), magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (Fe2O3), and quartz (SiO2), along with minor phases including lime (CaO), calcite (CaCO3), and portlandite (Ca(OH)2) [211]. The theoretical CO2 sequestration capacity of Class F fly ash was estimated at 74 g CO2 per kg of ash, underscoring its strong potential as a carbon capture material.

5.4. Iron & Steel Slag

According to the World Steel Association, more than 400 million tonnes of iron and steel slags are produced globally each year [212]. Among these, basic oxygen furnace (BOF) slag is more widely used in construction applications, particularly as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) in cement mortars compared to electric arc furnace (EAF) slag, which has relatively limited utilization. Despite this, EAF slag shows strong potential as a raw material for partial clinker substitution or as an aggregate in concrete, provided it undergoes proper stabilization [213].

Chemically, EAF slag is rich in calcium oxide (CaO), typically ranging from 45.0–50.0%, and contains significant amounts of silicon dioxide (SiO2, 15.0–30.0%), aluminum oxide (Al2O3, 3.0–20.0%), and magnesium oxide (MgO, 5.0–15.0%). Trace constituents such as manganese oxide (MnO), additional Al2O3, and sulfur trioxide (SO3) occur in concentrations between 0.2% and 5.0% [214]. However, the broader application of EAF slag has been hindered by concerns over heavy metal leaching and volume instability, primarily due to reactive phases such as free lime (CaO). These reactive components, however, have a high affinity for CO2 and can undergo mineral carbonation.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that near-total carbonation of EAF slag slurry can be achieved under controlled conditions. In one experiment, a slurry made with deionized water was exposed to 99.9% CO2 at a pressure of 1.03 kg/cm2 in a rotating packed bed reactor. Using a liquid-to-solid ratio of 25 mL/g and a temperature of 55 °C, the process achieved a peak carbonation efficiency of 86.3%, equivalent to a CO2 sequestration potential of 0.38 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of EAF slag [215].

The carbonated slag was subsequently evaluated for performance as an SCM. It was blended in varying proportions with Portland cement and tested for compressive strength and autoclave expansion. Specimens were cast in cubic molds, set for 24 h, and cured in saturated lime water at room temperature for 3, 7, 28, and 56 days. Results showed that both fresh and carbonated EAF slag met American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) standards for compressive strength [216]. Notably, carbonated slag exhibited higher early-age strength compared to uncarbonated slag, an improvement attributed to its increased surface area, which provided additional nucleation sites for hydration products, thereby enhancing strength development. These findings support the use of carbonated EAF slag as an effective SCM with superior mechanical performance.

In a commercial context, CarbiCrete, a Montreal-based company, has developed a proprietary technology that replaces cement in concrete mixtures with steel slag. The slag-based mixture, combined with aggregate and water, is processed using conventional concrete block production equipment. Instead of traditional curing, the blocks are placed in an absorption chamber where CO2 is injected. During this curing phase, CO2 is permanently mineralized as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which fills the pore structure and contributes to material strength within 24 h.

Comparative testing has shown that CarbiCrete concrete masonry units (CMUs) exhibit mechanical and durability properties equivalent to or superior to conventional cement-based CMUs. CarbiCrete CMUs have demonstrated up to 30% higher compressive strength and improved freeze–thaw durability, while maintaining comparable water absorption characteristics. From an environmental perspective, conventional CMUs emit approximately 2 kg of CO2 per unit, whereas CarbiCrete CMUs sequester 1 kg of CO2 per unit, resulting in net-zero emissions (CarbiCrete).

5.5. Red Mud/Bauxite Residue

The chemical and physical characteristics of red mud are largely determined by the type of bauxite used and the specific processing techniques applied during alumina production. Bauxite primarily contains alumina in the form of monohydrate (Al2O3·H2O) and trihydrate (Al(OH)3), with their proportions varying depending on the deposit. Common impurities include oxides of iron, silica, and titanium, along with trace amounts of elements such as zinc, phosphorus, nickel, and vanadium. In most alumina refining processes, hydrated lime is added, which reacts to form compounds such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and calcium oxalate (CaC2O2) that ultimately accumulate in the red mud.

The typical chemical composition of red mud includes iron oxide (Fe2O3, 30–60%), alumina (Al2O3, 10–20%), silica (SiO2, 3–50%), sodium oxide (Na2O, 2–10%), calcium oxide (CaO, 2–8%), and titanium dioxide (TiO2, up to 10% in trace amounts). Although caustic solutions are generally recovered and recycled in modern refineries, recovery efficiency is not complete, and older facilities may have poor caustic recovery. As a result, raw red mud often retains significant residual alkalis, primarily sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and sodium aluminate (NaAl(OH)4) which contribute to its high alkalinity, with typical pH values around 12.6.

Jones et al. [217] investigated the carbonation potential of raw red mud from alumina refineries and a neutralized derivative known as Bauxsol™. Their study aimed to assess the CO2 sequestration capacity of these materials. Carbonation experiments showed that, after 30 and 60 min of treating raw red mud, a slight reduction in bicarbonate alkalinity occurred as slurry pH increased. For Bauxsol™, carbonation over 20 min resulted in an 11% reduction in bicarbonate alkalinity. However, after 30 min, bicarbonate alkalinity increased by 26%, returning to levels observed in untreated Bauxsol™, while pH remained stable. Based on experimental data, the estimated annual CO2 sequestration capacity of red mud and its derivatives is approximately 15 million tonnes. These results highlight the potential of red mud as a carbon capture medium and emphasize the need for further research to optimize and scale this process for industrial application.

5.6. Concrete-Cement Industry

The concrete industry is one of the largest industrial sources of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, accounting for approximately 7% of global annual emissions. A significant portion of these emissions comes from the thermal decomposition of limestone (CaCO3) during clinker production, which releases CO2 while providing the calcium needed for cement hydration reactions. This calcination process is highly energy- and carbon-intensive, typically carried out at temperatures above 1000 °C.

To reduce the environmental impact of cement production, alternative CO2 capture and utilization strategies have been developed. Noguchi and colleagues at the University of Tokyo proposed a low-temperature carbonation process that captures and incorporates CO2 at around 70 °C [218] significantly lower than the temperature required for traditional limestone calcination. Moreover, the process uses CO2 sourced from industrial exhaust, enabling emission recycling. The resulting carbonated concrete blocks had a compressive strength of 8.6 MPa, lower than the typical 20–40 MPa range for Portland cement-based concrete. However, such material may still be suitable for low-load applications and could be further optimized for broader use.

Industrial by-products have also been explored as pozzolanic materials to partially replace Portland cement. For example, Critical Minerals (CR Minerals), in collaboration with Rio Tinto, has begun producing pozzolans from waste generated at the US Borax facility in Boron, California [219]. Pozzolans are siliceous or siliceous–aluminous materials with little or no intrinsic cementitious activity. When finely ground and mixed with calcium hydroxide in the presence of water, they undergo pozzolanic reactions to form calcium silicate hydrates with binding properties. Their use in cement reduces clinker demand and, consequently, CO2 emissions.

CarbonCure Technologies, based in Nova Scotia, has developed a commercial technology that reduces cement usage in concrete by mineralizing injected CO2. In this process, liquid CO2 is injected into a concrete mixture containing cement and water. Upon release, the rapid pressure drop converts the CO2 into solid and gaseous phases, which react with Ca2+ ions in the cement to form stable calcium carbonate (CaCO3). This mineralized product increases concrete strength while permanently sequestering CO2. The resulting concrete performs as well as or better than conventional concrete, with up to 30% higher compressive strength and improved freeze–thaw resistance. On average, each cubic meter of CarbonCure concrete prevents approximately 11.3 kg of CO2 emissions (CarbonCure).

While mineralization and biomineralization via industrial residues offers permanent storage and potential co-benefits (e.g., improved material strength, waste valorization), it competes with other CCUS options (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative Assessment of Major CO2 Utilization and Storage Pathways.

6. Future Prospects

CCUS technologies are expected to play a central role in achieving net-zero targets by 2050, but their future success will depend on overcoming cost, durability, scalability, and integration challenges. Multiple converging trends are shaping the next generation of CCUS:

Hybrid, Cross-Technology Integration Coupling DAC with accelerated mineralization [20,21] enables removal of diffuse atmospheric CO2 while providing permanent storage. Pairing point-source capture with CO2-cured building materials reduces industrial emissions and produces low-carbon construction products. Advanced Materials Engineering Continued development of moisture-tolerant MOFs [71], high-selectivity zeolites [90], and hydrogel-enzyme composites [195] will aim for high capture capacity, low regeneration energy (<2 GJ tCO2−1), and operational stability in real flue gas conditions. Bio-Inspired Catalysis and Enzyme Stabilization Immobilized carbonic anhydrase (CA) in hydrogels [184,187] offers mild-condition CO2 hydration compatible with biomineralization. Protein engineering [193] and acid-resistant hydrogel chemistries can extend enzyme lifetimes in SOₓ/NOₓ-rich industrial environments. Waste Valorization and Circular Economy utilizing mine tailings [210], fly ash [215], steel slag [221], and red mud [222] for mineralization achieves permanent storage and material substitution benefits. Techno-Economic Viability of current CA-hydrogel capture costs ($80–250 tCO2−1) could fall to $40–90 tCO2−1 with enzyme cost reductions, operational stability ≥ 12 months, and renewable-powered regeneration aligning with policy incentives such as the U.S. 45Q tax credit. Renewable-powered CCUS with recyclable sorbents could achieve > 85% net abatement [198], while fossil-powered systems without upstream CCS may see net benefits fall below 50%.

In conclusion, no single CCUS pathway will meet global decarbonization needs in isolation. The most promising route forward is a diversified portfolio integrating complementary strengths: DAC for diffuse emissions, mineralization for permanence, utilization for economic value, and bio-catalytic hydrogels for niche, low-temperature capture. Such integrative strategies co-located with renewable energy hubs and supported by robust policy frameworks will be critical to meeting 2030 interim goals and achieving net-zero by 2050.

Author Contributions