Abstract

Peatlands are natural reservoirs of organobromine compounds. Important advances have been made in unraveling the mechanisms involved in bromine (Br) retention in the peat but, to our knowledge, the temporal and spatial variation of the peat organic matter (OM) bromination has not been fully researched. Here, we present the study of 12 short cores (c. 30 cm, c. 150–200 years of peat accumulation) sampled from a small (c. 1 ha) area of an oceanic blanket peatland from northwestern Spain. We combine Br concentrations, spectroscopic analysis (FTIR–ATR), and structural equation statistical modelling (SEM). Our results show that Br is significantly correlated to proxies of peat aerobic decomposition, with concentrations increasing with depth in all cores (×2–10 times). Strong spatial heterogeneity was observed, with some cores showing much higher Br maximum concentrations and larger increases with depth. SEM modelling indicated that various OM functionalities contribute to Br accumulation and that their effects change with depth/age, with aromatics becoming dominant after 20–90 years. Thus, changes in organic matter molecular composition, linked to early peat diagenesis, and the geochemical conditions governing it exerted a strong control on Br accumulation in the studied peatland. Bromine wet deposition was not found to be a limiting factor.

1. Introduction

Bromine (Br) accumulation in soil and sediment is a complex process influenced by a variety of sources and the diagenetic transformations that occur within these environments. Historically, inorganic bromide (Brinorg) was often considered unreactive and used as a conservative tracer in hydrological studies. However, recent research has demonstrated that Br undergoes significant biogeochemical cycling, involving rapid bromination, and accumulation or degradation of organobromine compounds (OM-Br) with organic matter (OM) [1].

Bromine enters terrestrial and aquatic environments mainly through wet and dry atmospheric deposition, including various natural sources (seawater and sea salt aerosols, volcanic emissions, etc.), anthropogenic sources (biomass burning, fossil fuel combustion sources, etc.), and from the degradation of OM-Br compounds [2,3,4,5,6]. Because of its atmospheric cycle and predominantly marine source, Br is a ubiquitous element of great interest in paleoenvironmental studies, with which to trace and reconstruct moisture sources [7,8,9]. Today, although knowledge about the mechanisms of accumulation and degradation of OM-Br in environmental archives is better understood, the role of diagenetic, climatic, and geochemical factors is not yet fully understood or documented. This information is crucial in determining whether this tracer is conservative in the archives and what the limitations of its use in reconstructing past environments may be.

Organic matter decomposition plays a key role in the incorporation of Br into OM during decay. The amount of organically bound Br increases during the decomposition and humification of plant material, indicating that the degradation and bromination of organic matter are concurrent processes in soils [6,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Enzymatic bromination is proposed as the main pathway for the natural formation of halogenated organic compounds, with haloperoxidases and halogenases as key enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of inorganic bromide by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to reactive intermediates that brominate organic substrates [3]. Abiotic bromination also exists, including the oxidation of soil OM by ferric iron (Fe3+) and photooxidation reactions [4,16]. Fresh plant material is generally more susceptible to bromination than decayed litter and soil humus due to a labile pool of mainly aliphatic compounds that break down during the early stages of soil OM formation. Then, when the OM is humified, aromatic OM-Br compounds tend to be more stable [4].

In peat environments, Br has been found to be strongly associated with OM, where up to 91–95% of total Br exists in an organically bound form, covalently bonded to carbon [12]. Soil studies have shown that the degree of soil OM bromination, expressed as the Br/C molar ratio, increases with the age of the OM over millennia, suggesting that metal–bromine–OM compounds become enriched through time, likely due to the more intensive degradation of non-stabilized OM fractions [17]. In mineral soils, Br accumulation was also found to be strongly linked to the amount of OM stabilized as aluminum–OM associations and, to a lesser extent, soil acidity and iron–OM associations. These organo–metal complexes decrease OM degradability, leading to the preservation of brominated OM. Consistently, investigations on Br speciation using K-edge HERFD-XAS in surface samples of a highly decomposed Andean peatland showed that Br was mainly found associated with OM as aromatic Br compounds (>80%), with a minor percentage (<15%) of inorganic Br [18]. Aliphatic Br was not detected in the samples. Similar in-depth speciation of Br indicated no change in speciation during OM aging, suggesting that Br accumulates in wetlands as aromatic OM-Br preserved during OM humification, consistent with XAS data obtained in the humus fraction of a forest soil in New Jersey (USA) [4]. By contrast, a study of a Chilean bog has proposed that halogens are not conservative in bogs as the accumulation and speciation of Br is affected by diagenetic processes, varying with depth and environmental conditions [12].

Most previous studies were performed on either single, long, peat cores or a few cores (2–3) from different bogs (e.g., [13,14,15,19,20,21,22,23,24]) or by collecting several superficial samples in different wetland environments (e.g., [6,18]). These approaches provide insights into long-term OM bromination and environmental drivers, but they do not allow for an investigation on the timing and spatial variability of the bromination process. In this investigation, we analyzed 12 short cores (c. 30 cm depth) from the same peatland, combining Br concentrations, peat molecular composition (FTIR–ATR), and structural equation modelling (SEM). Our aims are (i) to determine the spatial and vertical (i.e., time) variations in Br concentration, (ii) to establish the role of early peat OM transformations on Br accumulation, (iii) to estimate the contribution of peat OM compounds (i.e., aliphatics, aromatics, carbohydrates), through statistical modelling, to Br retention, and (iv) to determine the timing and spatial variability of peat OM bromination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location, Sampling and Sample Preparation

The peat cores studied in the present research were collected in the Chao de Lamoso bog (CHL) and were originally investigated for Pb and Hg accumulation. Details of the sampling processing and storage are described in detail elsewhere [25]. The CHL bog (Figure 1), a blanket bog situated at 1039 m a.s.l. and about 20 km south of the Atlantic Ocean, is located in an area with an average annual precipitation of 1800 mm and an average annual temperature of 8 °C. The dominant lithology of the area is represented by quartzites, which underlie the peatland cover (peat thickness varies between 3 and 4 m). Surface vegetation is composed of grasses (Agrostis curtisii, A. hesperica, Festuca rubra, Deschampsia flexuosa, Molinia caerulea), sedges (Carex binervis, C. durieui, C. panicea), heathers (Calluna vulgaris, Erica cinerea, E. mackayana), and rush (Juncus bulbosus). Sphagnum mosses are present in low abundance. Heathers are more abundant in the eastern, drier area of the cored area.

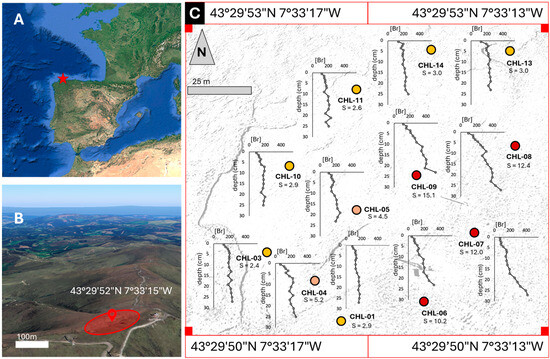

Figure 1.

(A) Location of the Chao de Lamoso bog (red star). (B) Location of the studied area (c. 1 ha) in the bog. (C) Br concentrations (μg g−1) in the CHL short cores. S: slope of the depth/concentration relationship. A strong pattern of increasing slope from the west to the east is apparent (color, from yellow to red, of the circles). The background gray image corresponds to the actual bog area where the cores were collected (images taken from Google Earth; image from year 2024).

Briefly, 14 short cores (~30 cm in thickness) were collected, the same day, in 1998 at the summit of the blanket bog complex, covering an approximate surface area of 1 ha. The cores were wrapped in plastic film, covered with aluminum foil, taken to the laboratory the same day of sampling, and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until processing. The cores were sectioned into 1 cm thick slices in the upper 5 cm and 2 cm thick slices below that depth. The external part of each core (c. 1 cm) was trimmed to avoid potential contamination from the corer, and each slice was divided into two halves. One half was oven dried at 35 °C, finely milled, and stored in cool and dark conditions. Of the 14 cores originally sampled, 12 were available for this study.

2.2. Peat Bromine Content Analysis

Bromine was determined using the XRF facility of the RIADT (Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, USC). Calibration was performed using standard reference materials (NIST 1568b Rice Flour; 1648A, Urban Particulate Matter; NIST 1649A, Urban Dust; BCR 611 and 612, Low content and High content Br) [26,27,28,29], which covered a range of certified concentrations from 1.4 ± 0.4 to 1190 ± 10 µg g−1, with a detection limit of 1 µg g−1 and a replicability within 5%.

2.3. Vibrational Spectroscopy Analysis

Dried and finely milled peat samples were analyzed by Fourier Transform Infrared–attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy (FTIR–ATR) using an Agilent Technologies Cary 630 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), hosted at the EcoPast research group laboratories of the USC. Spectra were recorded in the mid infrared region (MIR, 4000–400 cm−1), averaging 100 scans per sample. Resolution was set to 4 cm−1, and a background was obtained before analyzing every sample. Spectra were baseline corrected and normalized using Orange Data Mining software (version 3.38.0) [30].

MIR indices, i.e., the ratios between peak absorbances of relevant functional groups, were also calculated. The selected indices reflect the degree of peat decomposition (accumulation on aliphatic and aromatic components versus labile polysaccharide compounds, AL/PS and AR/PS), the degree of crystallinity of the molecular structure of the cellulose (CCr), the transformations of the lignin (guaiacyl versus syringyl moieties, G/S), the length versus the degree of ramification of the aliphatic moieties (length/ramification, LT/RM), and the oxidation of the peat OM and production of carboxylic acids (CBX). It has been suggested that they can provide an enhanced understanding of the molecular composition of the peat organic matter [31]. The bands included in the ratios, their assignation and meaning, as well as the references can be found in Table A1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Apart from the correlation analysis (i.e., Pearson “r” coefficient for normal distributed data) used to determine the degree of covariation between MIR indices, Br, and the FTIR–AR spectral signal, in this research, we also applied structural equation modelling (SEM) using SmartPLS software (version 4.1.1.5) [32]. PLS-SEM has the advantage of using several proxies for each predictor variable, avoiding multi-collinearity, and enabling the calculation of direct effects (of predictors on the response variable, i.e., Br) and indirect effects (i.e., interactions between predictors), so the predictors are defined to maximize the explanation of the response variable [33]. The sum of direct and indirect effects determines the total effect of each predictor and provides a synthetic evaluation of the importance of the weight of each predictor on the response variable. We opted for this approach, compared to other modelling approaches (such as CB-SEM), because PLS-SEM is less demanding regarding the number of samples, it is very efficient with non-normal distributions, and more adequate for explanatory and predictive purposes. As a first step to define the SEM model, we calculated the correlation between Br and absorbances for each wavenumber (i.e., correlation spectrum with “r” Pearson coefficients; see Section 3.3 below). Mid-infrared regions of the spectrum showing moderate-to-large positive and negative correlations to Br were selected for the model. To check the validity of the model, the SmartPLS bootstrapping function was used so path coefficients and total effects of the MIR regions were only retained when found to be significant (p < 0.05). We have already successfully used this approach to determine the factors affecting long-term Br accumulation in a peat sequence from Brazil [34].

3. Results

3.1. Bromine Concentrations: Vertical and Spatial Distribution

The average Br concentration for all peat cores and depths (n = 192) was 192 ± 80 μg g−1, with values ranging from 45 to 520 μg g−1 (Figure 1). Concentrations increased with depth and the slope of the depth/Br concentration relationship varied between 2.3 and 15.1 (Figure 1), which indicates average increases of 68 to 453 μg g−1. The maximum/minimum concentration ratio also showed large variations, ranging between 1.8 and 7.2. Figure 1 also shows that Br depth records have a strong spatial pattern: lower depth-increases were found in the western side of the bog and higher depth-increases in the eastern side.

3.2. Peat Molecular Composition: FTIR–ATR

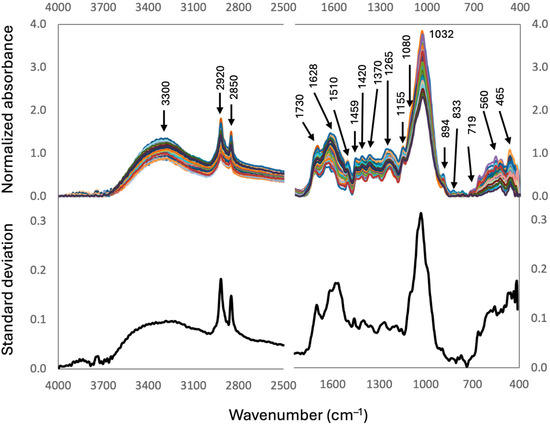

The mid-infrared (MIR) spectra of the peat samples and the standard deviation spectrum are shown in Figure 2 with the most relevant bands. All spectra showed essentially the same bands, with high-to-moderate absorbances in the O-H stretching region (3500–3200 cm−1), for the characteristic aliphatic C-H peaks at 2920 and 2850 cm−1, the carbonyl-aromatic region (1800–1600 cm−1), and the C-O stretching region (1100–900 cm−1). Lower absorbances were also found in the 1510–1200 cm−1 region, where aromatic, conjugated C=N, O-H, amino, and phenolic groups from lignin, N-compounds, and aliphatic compounds absorb (see Table A2 for the assignation of bonds and compounds responsible for the MIR absorbance bands/peaks). The largest variability between samples (i.e., standard deviation) were observed in the 1100–960 cm−1 region, followed by the two aliphatic peaks and the 1800–1500 cm−1 region (Figure 2). Moderate-to-low variability occurred in the 1500–1100 cm−1 region.

Figure 2.

Upper panel, MIR Spectra of the peat samples of the CHL cores analyzed in this study (n = 192), with an indication of the wavenumbers of the main absorbances. Assignation of the absorbances can be found in Table A2. Lower panel, standard deviation spectrum showing the regions which show the largest variability between samples. Colors are intended to enhance spectra visualization.

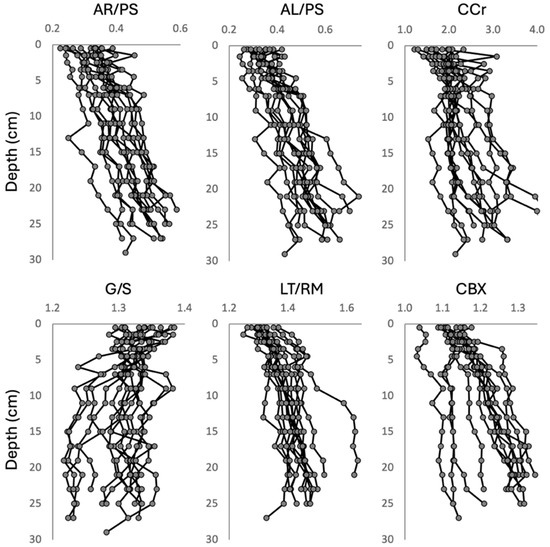

The depth records of the MIR indices can be found in Figure A1. Almost all indices showed an increase in values with depth, with an exception made for the guaiacyl/syringyl (G/S) index, which showed a tendency to decrease with depth. Collectively, they all showed substantial spatial variability that increased with the peat depth. The aromatics/polysaccharides (AR/PS), aliphatics/polysaccharides (AL/PS), and carboxylic (CBX) indices were highly correlated between them (Table 1), and the length/ramification of the aliphatic chains (LT/RM) were moderately correlated to these indices. The correlation of G/S to the other indices was marginal.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients for the linear relationship between MIR indices and Br and between the MIR indices. Codes of MIR indices are described above and bands included in the calculation can be found in Table A1. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; n = 192.

3.3. Peat Molecular Composition and Br Concentrations

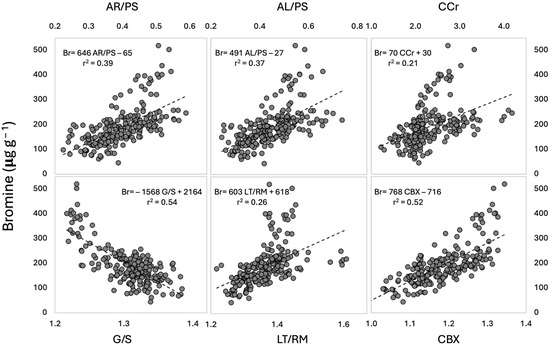

Bromine concentrations in the peat were significantly (p < 0.01) correlated to the MIR indices (Table 1), with CBX and G/S showing the highest correlation coefficients. AR/PS, AL/PS, and LT/RM were moderately correlated, and CCr was marginally correlated. It is evident from the scatterplots (Figure 3) that the data population contained two groups, with samples having Br concentrations above ~250 μg g−1 departing from the trendline of the other samples. This departure was less apparent for the G/S and the CBX indices. These samples belong to the cores located to the east of the bog (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Relation between MIR indices and Br concentrations (n = 192). The values of the Pearson correlation coefficients can be found in Table 1.

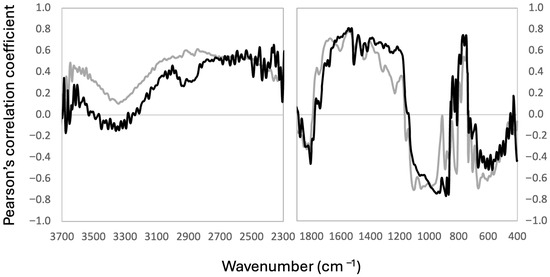

To explore in more detail which regions of the MIR spectrum (i.e., bond vibrations) could be related to the Br spatial and vertical variation, we produced correlation spectra for the cores of the western (n = 97) and eastern (n = 95) side (Figure 4). In both cases, highly negative (r < −0.5, p < 0.01) correlations were shown in the 1100–850 cm−1 and 700–500 cm−1 spectral regions, and high positive correlations in the 1800–1200 cm−1 and the 800–750 cm−1 regions. Despite this general pattern, differences were observed in the correlation spectra of the cores of the western and eastern sides. Correlation coefficients for the 1800–1670 cm−1 region were lower, while correlation coefficients for the 1390–1200 and 800–750 cm−1 regions were higher for the cores from the eastern side than for those of the western side (Figure 4). The largest negative correlation coefficients were shifted for both groups of samples: the Br of the cores from the western side showed the largest negative coefficients in the 1100–980 cm−1 region, with the eastern cores shifting to the 950–868 cm−1 region. Marginal positive correlations mostly occurred in the aliphatic region between 3050 and 2800 cm−1, except for the peaks at 2920 and 2850 cm−1, which showed a moderate correlation (r = 0.6, p < 0.01) for the western cores but were much lower for the eastern cores (Figure 4). The only spectral region for which the Br concentrations showed high, positive, correlation coefficients independent on core location was that between 1640 and 1400 cm−1.

Figure 4.

Correlation spectra for Br concentrations. Each value corresponds to the Pearson coefficient of the correlation between the normalized absorbance of each wavenumber and Br concentration in the peat samples. The gray line is the correlation for samples of the western cores (low overall Br concentrations, n = 97) and the black line is the correlation for samples of the eastern cores (high overall Br concentrations, n = 95).

The correlation spectra can thus be divided into seven main OM functional group (OM-FG) regions: aliphatics (3035–2800 cm−1), carbonyl (1800–1670 cm−1), aromatic (1640–1400 cm−1), alkyl+aromatics (1390–1200 cm−1), carbohydrates-1 (1100–930 cm−1), aromatic C-H (800–750 cm−1), and carbohydrates-2 (700–500 cm−1). These regions are specifically related to the C-H bond vibrations associated with aliphatic groups (3050–2800 cm−1) as well as the C-H of aromatic rings (800–750 cm−1), carbonyl/carboxylic (1800–1670 cm−1), aromatic skeleton (1640–1400 cm−1), alkyl+aromatics (1390–1200 cm−1), and carbohydrates (1100–930 and 700–500 cm−1).

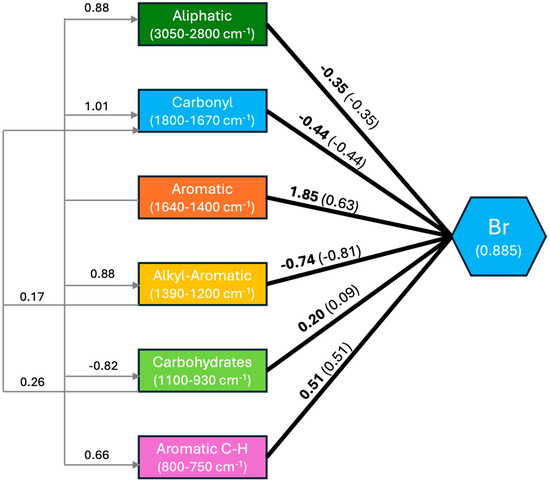

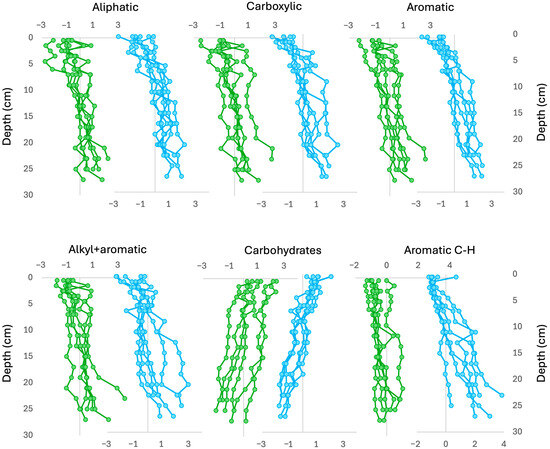

3.4. Modelling Br in Peat Using the Spectral Signal

Based on these findings, we built a structural equation model (SEM) which included Br concentrations as response variables and the regions of the MIR spectra, described above, as predictors. In an initial SEM model, the carbohydrate-2 region failed to pass the bootstrapping test, i.e., the path coefficient was not significant, and this region was not retained in the final model. The final SEM model is presented in Figure A2 and the depth distribution of the model scores for the OM-FG regions can be found in Figure A3. Almost all OM-FG regions showed an increase with depth, except for the carbohydrates, which showed a decrease. Aromatic C-H showed little depth variation in the western cores but quite large variations in the eastern cores. The depth trends of the OM-FG regions showed lower variability for the cores of the eastern side of the bog compared to those of the western side.

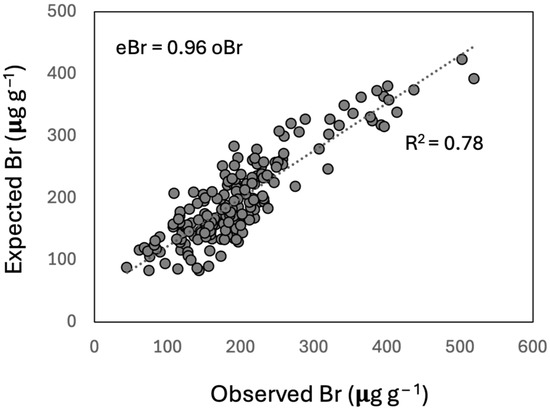

The model explained a large percentage (78%; SRMR 0.1, NFI 0.93) of the Br concentration variance. The correlation between the observed and expected values was very high (R2 = 0.90, n = 95, p < 0.01; Figure 5) for the eastern cores and lower for the western cores (R2 = 0.52; n = 97, p < 0.01). The path coefficients (Figure A2) indicate that the OM-FG region with the largest effect on Br accumulation was that of aromatics (1640–1400 cm−1), followed by aromatic C-H (800–750 cm−1). Carbohydrates absorbances (1100–930 cm−1) had a low positive effect. Conversely, the alkyl+aromatics (1390–1200 cm−1) had a large negative effect, and the carbonyl (1800–1670 cm−1) and aliphatics (3050–2800 cm−1) had moderate negative effects.

Figure 5.

Relationship between the expected Br (eBr) concentrations, obtained with the SEM model based on the peat OM molecular composition and the observed Br (oBr) concentrations (n = 192). The coefficients (i.e., direct effects, indirect effects, and interactions) of the model are summarized in Figure A2.

The MIR regions showed significant interactions between them (Figure A2). Large positive interactions were found between the aromatics and aliphatics, aromatic C-H, carbonyl, and alkyl+aromatics. Aromatics showed a large negative interaction with carbohydrates. Low to marginal, positive interactions were observed for alkyl+aromatics and carbohydrates with carbonyl. The largest total positive effects corresponded to the aromatics and aromatic C-H (Figure A2). The largest negative total effect corresponded to the alkyl+aromatics, showing the aliphatic and the carbonyl moderate, negative total effects on the Br concentration. The total effect of carbohydrates was close to zero.

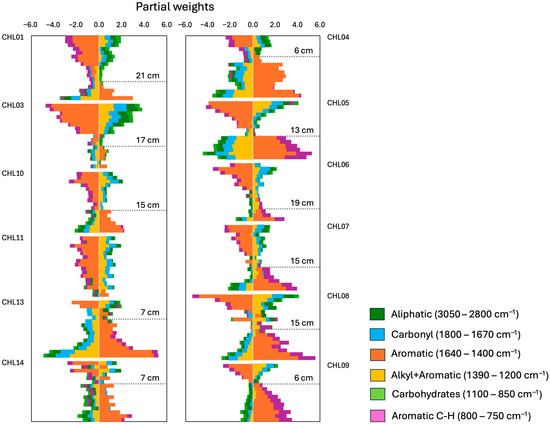

Low Br concentrations at the surface of the cores were associated with the low positive contributions (i.e., weights) of alkyl+aromatics, carbonyl and, to a lower extent, aliphatics; while lower contents of aromatics and aromatic C-H contributed to lower Br concentrations (Figure 6). With depth, the increasing Br concentrations were related to dominance of the aromatics contribution, and, in the cores from the eastern side of the bog, with a secondary contribution from aromatic C-H. This increase was accompanied by decreases in the other OM-FG regions.

Figure 6.

Partial weights of the OM-FG regions on the Br concentration, obtained with the SEM model, in the studied peat cores (left panel, western cores; right panel, eastern cores). Estimation of the partial weight of each OM-FG region is obtained by multiplying the path coefficient by the score value of each OM-FGr for every sample of each core.

The depth at which the contribution of the aromatics became consistently dominant varied between the cores. In most cores, the aromatics started to dominate Br concentrations at 13–19 cm but, in some, this occurred at shallower or even a greater depth (Figure 6). In one core (CHL-11), the aromatic contribution was not dominant at any depth. Using the estimated ages for the peat cores published in previous investigations [25,35], we fitted the trend for the aromatics region (Table A3). For almost all cores, the models suggested that it took from 20 to 90 years for the aromatic compounds to dominate the Br accumulation in the peat. The average for all cores was 50 ± 30 years, with no significant differences (p > 0.05) between the western and eastern sides of the bog.

4. Discussion

4.1. Depth and Spatial Changes of Peat Molecular Composition

The MIR spectra of the samples from the studied CHL cores are characterized by the occurrence of various functional groups that are associated with the peat organic components, including polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, lignin and other aromatics, and organic acids, among others [36,37,38]. On the one hand, these components are primarily related to the plant material constituting the peatland vegetation; on the other hand, they are also connected to peat OM transformations related to the influence of environmental factors (i.e., climate, seasonality, and hydrological conditions) and time. For example, the large variability shown by the 1100–960 cm−1 spectral region, related to polysaccharides content, is mainly due to differences between the upper and bottom peat layers of the cores, i.e., a substantial decrease of polysaccharide compounds with increasing depth/age. This pattern reflects the long-term peat decomposition process through which labile peat OM compounds are depleted [21,37,39]. The high variability shown by the aliphatic groups can be associated with the formation of humic substances taking place during the peat OM degradation [40,41]. Also, the moderate variability observed in the 1500–1100 cm−1 region suggests differences in the occurrence of lignin and specific organic acids, compounds that are less susceptible to the overall transformation processes. This is consistent with previous studies indicating the resistance to degradation of aromatic compounds, because their complex structure makes it difficult for enzymes to recognize and break them down efficiently, unlike the more regular and linear structures of polysaccharides [31,42].

The calculated MIR ratios helped to simplify the interpretation of the complex FTIR data, by reflecting the relative abundance of specific functional groups [31,43]. In the CHL cores, the high correlation between AR/PS, AL/PS, usually interpreted as reflecting peat decomposition, and CBX indicates that the accumulation of aromatic and aliphatic compounds and the peat OM oxidation are concurrent processes. In fact, these MIR indices are linked to the humification process (i.e., depletion of linear polysaccharide structures and increase in aromatic compounds by increased polymerization) [21,37]. Their moderate correlation with the LT/RM index additionally points to transformations of the chains of aliphatic linear compounds (i.e., alkanes and alkenes). However, LT/RM is also potentially linked to the sources of the peat OM (i.e., vegetation) and its degree of decomposition [21]. The marginal, negative correlation to G/S suggests that only part of the change in lignin moieties (i.e., guaiacyl vs. syringyl) could be related to the overall peat degradation. In previous studies, G/S was also found to be largely uncorrelated, or only marginally correlated, to the other MIR indices [44]. Drier, oxidizing conditions were found to result in an increase in the abundance of syringyl moieties during peat decomposition [45], resulting in lower G/S index values. Thus, most of the variation in lignin composition seems to depend more on bog vegetation changes and shorter-term decomposition (mediated by variations in bog surface wetness), rather than changes due to long-term decomposition [15,44,46].

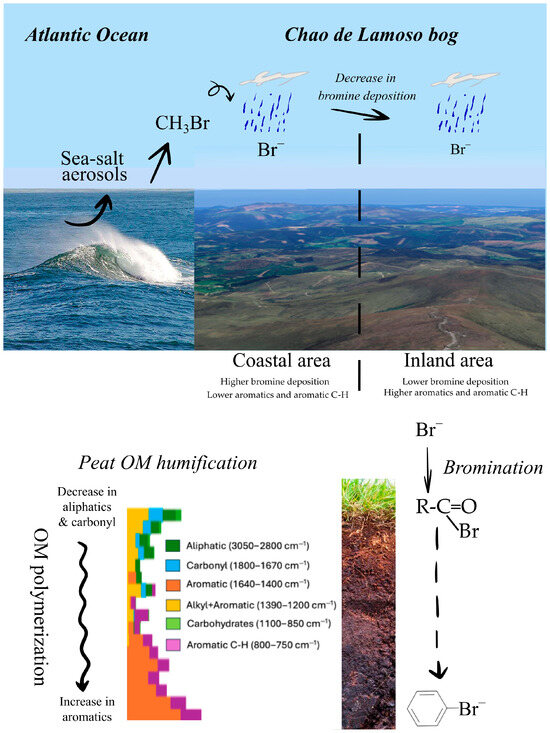

4.2. Bromine Concentrations and Peat Decomposition

The bromine concentration in the peat cores varied by an order of magnitude, from a few tens to hundreds of micrograms per gram, and showed moderate-to-large increases with depth. The highest concentrations are comparable to those obtained in previous peat studies in oceanic areas (e.g., [6,13,24]), including the studied area [14], and are about one order of magnitude higher than those found in continental bogs (e.g., [20]). This finding seems to support the accepted interpretation that Br concentrations in rainwater decrease with increasing distance to the ocean (Figure 7). Despite this, comparable high Br concentrations were found in Brazilian mires located at hundreds of kilometers from the coast [34], and previous investigations on Br in rainwater found that Br was enriched at elevated inland locations [6,47,48,49].

Figure 7.

Conceptual model synthesizing the main sources and mechanism involved in bromine accumulation in the studied peat cores.

Bromine was highly correlated to MIR indices that are proxies for peat decomposition and lignin transformation (Figure 3). This result agrees with many previous investigations on peat OM bromination [10,11,12,14,34], with the finding that all Br in peat and pore waters is in the form of OM-Br compounds [6,13,50]. Biester et al. [12] suggested that the atmospherically deposited Br is retained in the peat OM humic compounds due to biotic and abiotic mechanisms, while Zaccone et al. [15] found that a large proportion (40%) of the Br in the peat core they analyzed was incorporated into humic acid molecules.

Our data also suggests that transformations affecting to esters and carboxylic compounds (CBX index) and lignin moieties (G/S index) have a greater overall correlation to the Br concentration. Both MIR indices are related to aerobic peat decomposition, and thus the Br incorporation in peat is coupled to oxidative process. In the long peat cores from the studied area, spanning several thousands of years, Br (and I) was also found to be enriched in peat layers formed in periods of drier climatic conditions with a greater degree of peat decomposition, while lower concentrations were found in peat layers corresponding to wetter periods with a lower degree of peat decomposition [14]. The formation of organo–halogenated compounds is mediated by oxygen-dependent enzymatic processes [51,52,53] and abiotic mechanisms also requiring oxidizing conditions [4,16,54], and they are enriched during OM decomposition [3,4,55,56].

Bromination is a rapid process occurring in the upper layers of peat and mineral soils [3,4,17], and OM-Br compounds seem to be highly resistant to decomposition, accumulating through time [13,17]. As indicated by Biester et al. [21], Br concentrations in surface soils and sediments are controlled by two main mechanisms. The first involves the inputs of Br anion, directly (as in salt marshes) or indirectly by atmospheric wet deposition. The second mechanism pertains to the bromination process and its kinetics. The authors proposed that the limiting factor for OM bromination is the OM substrate in salt marshes and Br atmospheric deposition in continental wetlands. Leri and Myneni [3] also suggested that bromide availability is often the limiting factor for OM bromination in continental areas. While these are correct assumptions, calculations of Br retention in peat indicate that only a small proportion of the total deposited bromide is actually retained. Shotyk [19] found that more than 90% of the Br supplied in rainwater in two peatlands from Scottland was not retained in the peat, while Biester et al. [12] estimated retention values as low as 7.5% in peat cores from Patagonia, and Martínez Cortizas et al. [17] estimated 6–16% total retention in acid, organic rich colluvial soils. Using the bulk density and age data from the previous investigation on the same cores [25], we estimated that the Br retention in the upper peat sample of each core (representing c. 10 years of peat accumulation) varies between 2% and 8%. Thus, at least in oceanic areas and in elevated continental settings, bromide availability is not likely to be a limiting factor. Geochemical conditions controlling bromination kinetics (products/yields), as suggested by Moreno et al. [6], and availability of OM compounds amenable to bromination are likely the most limiting factors.

4.3. Peat OM Compounds Involved in Br Retention in Peat

The spectra of correlation between the MIR signal and Br showed high positive values for absorbances related to ester (C=O), carboxylic (COOH), carboxylates (COO-), aromatic (C=C), alkyl (CH2 and CH3) and aromatic C-H absorbances, and negative values for polysaccharides (C-O) absorbances. These results indicate that various peat OM functionalities are involved in Br retention in the CHL cores, with the aromatic region showing the largest positive correlations. The observed decrease in the carbonyl/carboxyl signal (1740–1700 cm−1) and the increase in the aromatic region may be a consequence of the formation of carboxylated OM-Br compounds. Similar observations were made for metals binding in mosses. Elevated metal contents were found to be linked to the higher abundance of acidic functional groups [57], and for Hg, peak absorbances of hydroxyl (-OH) and carboxyl (COO-) groups were the ones that changed most significantly with increasing Hg concentration [58]. Significant shifts in the MIR spectrum have also been observed in humic acids, with increasing Hg concentration, resulting in a decrease in intensity of the carboxyl (-COOH) absorbance in parallel to an increase in the carboxylate (-COO-) absorbance [59].

These findings are also consistent with our SEM model, which shows that aromatics and aromatic C-H structures had a positive total effect, alkyl+aromatics and aliphatics a negative effect, and carbohydrates no direct effect on the Br content (Figure 7). The depth distribution of the weights of the predictor OM-FG regions implies that surface samples are characterized by low positive contributions of alkyl+aromatics, carbonyl and aliphatics, while in depth the contribution of the aromatics and aromatic C-H dominate. Previous investigations have already demonstrated that Br is mostly incorporated into aliphatic and aromatic compounds and that Br in soil humic substances is dominated by aromatic OM-Br speciation [3,4,13], as also found for brominated marine OM [54]. For Cl, Myneni [55] found that OM-Cl compounds increased with the degree of humification of the OM, with phenolic-Cl compounds increasing in parallel to a decrease in aliphatic-Cl. Our results are consistent with these findings and point to a change in the molecular composition of the brominated organic compounds, with aromatics predominating in the peat sections with a higher degree of decomposition. The negligible total effect of the carbohydrates suggests that they play no active role in Br accumulation, despite their abundance being highly dependent on peat decomposition.

4.4. Spatial Variations in Br Distribution in the CHL Peatland

Many investigations have dealt with single cores from one bog [8,9,14,15,20,22,24], 2–3 peat sequences from different bogs (e.g., [12,13,19,23]), or surface samples from one or more bogs (e.g., [6]). These investigations have provided insights into long-term peat OM bromination and the environmental factors affecting it, but they do not allow us to determine the extent of spatial variation in peat OM bromination in the same peatland. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies on Br in peat that assessed both within bog vertical and spatial variability.

We have found substantial within bog differences in Br accumulation in a relatively small (c. 1 ha) patch of a blanket peatland (Figure 1) and, although the main mechanisms are the same, the SEM model better constrains the Br content in the eastern side of the bog than that of the western side of the bog. In spite of this, no clear spatial pattern in the timing of dominance of Br-aromatics was found.

Our results thus show that peat decomposition processes and the abundance of aromatic compounds largely control Br accumulation in the studied peat cores. These results may bear implications for the use of Br in paleo research, both for its use as an indicator of past rainfall and storminess [7,8,9] and as an element to normalize Hg concentrations in paleo pollution studies (e.g., [20]). Peat layers with increased Br content may not reflect higher past Br atmospheric deposition and, consequently, increased rainfall (i.e., wetter conditions) since total Br retention (the balance between total Br deposition and accumulation in peat) is low and bromination occurs mainly under oxidizing, i.e., drier, conditions at the surface of the bog. Future research, with similar modelling approaches, in long cores from oceanic and continental areas, with consistent age models, may help to shed light on Br reliability as a rainfall indicator at long time scales. Also, our results indicate that there is a delay between Br deposition and retention of 50 years on average, which may not be relevant for long-term millennial reconstructions but will be crucial for centennial and decadal reconstructions. As for it use in mercury cycle studies using peat, although both elements strongly bind to organic compounds after deposition, their incorporation and accumulation mechanisms are quite different: Br is deposited as bromide ions through wet deposition and mainly retained in aromatic compounds, while Hg is incorporated into vegetation as elemental Hg, transformed into ionic mercury (Hg+2) and retained in different OM compounds inside the plant [60,61,62]. Previous research has also shown that changes in environmental factors affected differently the Br and Hg accumulation in peat at millennial scales (e.g., [34]).

5. Conclusions

In the Chao de Lamoso bog, maximum Br concentrations in the peat were similar to those obtained in previous peat studies in oceanic areas. Our results also suggest that only a small proportion of the deposited bromide is retained as OM-Br compounds, coupled to peat decomposition (i.e., OM oxidation), and to the presence of carboxylic and lignin moieties, in particular.

SEM modelling indicates that aromatic compounds had the largest positive effect on Br concentration in the peat, but aliphatics, carbonyl, and alkyl+aromatics had negative effects, and no significant effect was found for polysaccharides. In the surface/younger peat layers, low Br concentrations were linked to alkyl+aromatics, carbonyl, and aliphatics, while in deeper/older layers the aromatics dominated Br retention—possibly through the formation of carboxylated OM-Br compounds. The predominance of aromatic-Br forms occurred after 20 to 90 years of peat accumulation.

A strong pattern of intra-site and intra-core variability was found. Peat bromination was spatially heterogeneous, even in such a small area (c. 1 ha) of a peatland. Heterogeneity was presumably related to variable abundances of aromatic compounds that seem to be linked to both vegetation and hydrological conditions. The spatial results are consistent with the importance of the geochemical environment in promoting bromine kinetics and retention.

Our results also have implications for other current research lines in which the bromine content in peat is used as a proxy for environmental changes (e.g., reconstruction of the timing of wet phases and storminess in oceanic areas). First, in agreement with the previous studies, we show that bromide availability was not a limiting factor for Br accumulation in the CHL bog; therefore, using bromine to reconstruct climatic conditions related to sea/ocean winds and rainfall may not be accurate in all cases. Second, the large spatial heterogeneity in peat bromination, raises concerns on interpreting the Br data from single core studies. From a cost–savings perspective, it may seem logical to analyze a single core per peatland; however, the resulting generalizations must be taken with caution. Future studies must ensure that intra-site variability is not larger than inter-site variability. We thus recommend sampling several cores to cover potential variations in vegetation and bog hydrological conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soilsystems9040120/s1, Data file, in Excel format, cotaining Br concentrations and normalised absorbances of selecet wavenumbers for all analysed samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.C., G.S., M.T., O.L.-C. and S.G.; methodology, A.M.C. and O.L.-C.; investigation, A.M.C., G.S., M.T., O.L.-C. and S.G.; resources, A.M.C. and O.L.-C.; data curation, A.M.C. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.C., G.S., M.T., O.L.-C. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, A.M.C., G.S., M.T., O.L.-C. and S.G.; visualization, A.M.C. and O.L.-C.; project administration, A.M.C. and O.L.-C.; funding acquisition, A.M.C. and O.L.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Grupos de Referencia Competitiva (ED431C 2025/18, Xunta de Galicia) and the European Union (ERC Consolidator Grant, PollutedPast, 101087832). The views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. O.L.-C. is funded by Ramón y Cajal 2020 (RYC2020-030531-I, Miniserio de Ciencia e Innovación).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available as Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

MIR indices, indicating the bands included in the calculation and the meaning of each of the indices. Note that the AR/PS and AL/PS indices have been reversed so the increase in value corresponds to an increase in the peat decomposition. For further reference, see the References listed.

Table A1.

MIR indices, indicating the bands included in the calculation and the meaning of each of the indices. Note that the AR/PS and AL/PS indices have been reversed so the increase in value corresponds to an increase in the peat decomposition. For further reference, see the References listed.

| MIR Ratio | Absorbances (cm−1) | Meaning | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AL/PS | 2920/1030 | Aliphatics/Polysaccharides: degree of peat decomposition | [59] |

| AR/PS | 1600/1030 | Aromatics/Polysaccharides: degree of peat decomposition | [21,63,64] |

| CCr | 1370/2920 | Crystallinity index: degree of crystallinity of the molecular structure of cellulose | [42] |

| G/S | 1265/1311 | Guaiacyl/Syringyl moieties: degree of evolution of lignin | [65,66] |

| LT/RM | (2920 + 2850)/(2960 + 2870) | Length/ramification of the aliphatic compounds | [67,68] |

| CBX | 1705/1730 | Carboxyl/carbonyl: production of carboxylic acids due to peat OM oxidation | Inferred from [36,39,44] |

Table A2.

Main absorption bands of the MIR spectra of the CHL cores. For further reference, see the References listed.

Table A2.

Main absorption bands of the MIR spectra of the CHL cores. For further reference, see the References listed.

| Band (cm−1) | Bond/Compound Assignment | References |

|---|---|---|

| 3300 | O-H groups in cellulose, alcohols, phenols, and water | [36,37] |

| 2920 | C-H asymmetric stretching of lipids, fats, waxes | [37] |

| 2850 | C-H asymmetric stretching of lipids, fats, waxes | [37] |

| 1730 | C=O stretching of carbonyl functions, as aldehydes, ketones and carboxyl groups | [36] |

| 1628 | C=C stretching in aromatic compounds and COO− groups | [36] |

| 1510 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations, conjugated C=N systems and amino functionalities, lignin or phenolic backbone | [36] |

| 1459 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations (of amide II), conjugated C=N systems and amino functionalities, lignin or phenolic backbone | [69] |

| 1420 | O-H deformation of phenolic and aliphatic groups | [36] |

| 1370 | O-H deformation of phenolic and aliphatic groups | [36] |

| 1265 | C-O stretching of ethers and/or carboxyl groups, indicative of lignin backbone | [36,37] |

| 1155 | C-O stretching in polysaccharides, and aromatic C-H deformation in syringyl lignin units | [70] |

| 1080 | C-O stretching of polysaccharides structures, cellulose | [36] |

| 1032 | C-O stretching of polysaccharides structures, cellulose | [36] |

| 894 | O-H deformation in carbohydrates | [21] |

| 833 | C-H out of plane of aromatics, lignin | [37,41] |

| 719 | CH2 wagging of aliphatic groups | [37,44] |

Table A3.

Fitting of the weights of the aromatic OM-FGr versus time: “a” stands for the constant, b1 and b2 are the regression coefficients for linear and polynomial fitting, respectively, “r” is the Pearson correlation coefficient and, “years” indicates the time it takes for the aromatics to totally control the Br accumulation in each core. Statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

Table A3.

Fitting of the weights of the aromatic OM-FGr versus time: “a” stands for the constant, b1 and b2 are the regression coefficients for linear and polynomial fitting, respectively, “r” is the Pearson correlation coefficient and, “years” indicates the time it takes for the aromatics to totally control the Br accumulation in each core. Statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

| a | b1 | b2 | r | Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHL-01 | −2.517 | 0.027 | 0.978 ** | 93 | |

| CHL-03 | −4.500 | −0.004 | 0.092 | 0.987 ** | 75 |

| CHL-10 | −1.834 | 0.030 | 0.962 ** | 61 | |

| CHL-11 | −1.854 | 0.014 | 0.762 ** | 132 | |

| CHL-13 | −0.646 | 0.036 | 0.912 ** | 18 | |

| CHL-14 | −0.745 | 0.023 | 0.760 ** | 32 | |

| CHL-04 | −0.664 | 0.035 | 0.847 ** | 19 | |

| CHL-05 | −4.707 | −0.0003 | 0.102 | 0.984 ** | 58 |

| CHL-06 | −2.154 | 0.030 | 0.917 ** | 72 | |

| CHL-07 | −2.010 | 0.029 | 0.952 ** | 69 | |

| CHL-08 | −2.658 | 0.044 | 0.920 ** | 60 | |

| CHL-09 | −1.898 | −0.0005 | 0.086 | 0.983 ** | 24 |

Figure A1.

Depth records of the MIR indices calculated based on ratios between bands of the spectra of the peat samples of the CHL cores. For the codes on the MIR indices, see Table A1.

Figure A2.

Structural equations model: effect of peat molecular composition on Br concentration. Path coefficients in bold, total effects on Br concentration are between parentheses; numbers to the left correspond to the coefficients of the interactions between the OM-FG regions.

Figure A3.

Depth records of the scores of the OM-FG regions for each core. Western cores in green and eastern cores in blue.

References

- Albers, C.N.; Rosembom, A.E. Bromide reactivity in topsoil: Implications for use as a “conservative” tracer in assessing quantity and quality of water. Vadose Zone J. 2023, 22, e20260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, R.; Keene, W.; Pszenny, A.; Arimoto, R.; Ayers, G.; Baboukas, E. Inorganic Bromine in the marine boundary layer: A critical review. Atmos. Chem. 2003, 3, 1301–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, A.C.; Myneni, S.C.B. Natural organobromine in terrestrial ecosystems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, A.; Ravel, B. Abiotic bromination of soil organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13350–13359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, S.R.; Rizzo, A.; Daga, R.; Williams, N.; Villa, S. Bromine as indicator of source of lacustrine sedimentary organic matter in paleolimnological studies. Quat. Res. 2019, 92, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Moreno, J.; Fatela, F.; Guise, L.; Vieira, C.; Leira, M. Bromine biogeodynamics in the NE Atlantic: A perspective from natural wtlands of western Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Fatela, F.; Leorri, E.; Araújo, M.F.; Moreno, F.; De la Rosa, J.; Freitas, M.C.; Valente, T.; Corbett, D.R. Bromine enrichment in marsh sediments as a marker of environmental changes driven by Grand Solar Minima and anthropogenic activity (Caminha, NW Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 506–507, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orme, L.; Davies, S.J.; Duller, G.A.T. Reconstructed centennial variability of Late Holocene storminess from Cors Fochno, Wales, UK. J. Quat. Sci. 2015, 30, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, H.; Bradwell, T.; Bullard, J.; Davies, S.J.; Golledge, N.; McCulloch, R.D. 8000 years of North Atlantic storminess reconstructed from a Scottish peat record: Implications for Holocene atmospheric circulation patterns in Western Europe. J. Quat. Sci. 2017, 32, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y. Occurrence of bromine in plants and soils. Talanta 1968, 15, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelm, O.; Johansson, M.; Öberg, G. Organically bound halogens in coniferous forest soil. Chemosphere 1995, 30, 2353–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biester, H.; Keppler, F.; Putschew, A.; Martínez Cortizas, A.; Petri, M. Halogenes, organohalogens and the role of organic matter decomposition on halogen enrichment in two peat bogs from Tierra del Fuego (Chile). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1984–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biester, H.; Martínez Cortizas, A.; Keppler, F. Occurrence and fate of halogens in mires. Dev. Earth Surf. Process. 2006, 9, 449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Biester, H.; Mighall, T.; Bindler, R. Climate-driven enrichment of pollutants in peatlands. Biogeosciences 2007, 4, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Cocozza, C.; Shotyk, W.; Miano, T.M. Humic acids role in Br accumulation along two ombrotrophic peat bog profiles. Geoderma 2008, 146, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, F.; Elden, R.; Niedan, V.; Pracht, J.; Schöler, H.F. Halocarbons produced by natural oxidation processes during degradation of organic matter. Nature 2000, 403, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Vázquez, C.F.; Kaal, J.; Biester, H.; Casais, M.C.; Rodríguez, T.T.; Lado, L.R. Bromine accumulation in acidic black colluvial soils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 174, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédron, S.; Sarret, G.; Tolu, J.; Ledru, M.-P.; Campillo, S. Pre-hispanic wetland irrigation and metallurgy in the South Andean Altiplano (Intersalar Region, Bolivia, XIVth and XVth century CE). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2024, 338, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotyk, W. Atmospheric deposition and mass balance of major and trace elements in two oceanic peat bog profiles, northern Scotland and the Shetlands Islands. Chem. Geol. 1997, 138, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos-Barraclough, F.; Martinez-Cortizas, A.; García-Rodeja, E.; Shotyk, W. A 14500 years record of the accumulation of atmospheric mercury in peat: Volcanic signals, anthropogenic influences and a correlation to bromine accumulation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 202, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biester, H.; Knorr, K.-H.; Schellekens, J.; Basler, A.; Hermanns, Y.-M. Comparison of different methods to determine the degree of peat decomposition in peat bogs. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2691–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Rein, G.; D’Orazio, V.; Hadden, R.M.; Belcher, C.M.; Miano, T.M. Smouldering fire signatures in peat and their implications for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 137, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, T.; Blodau, C.; Biester, H.; Knorr, K.H. Peat decomposition records in three pristine ombrotrophic bogs in southern Patagonia. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylander, M.E.; Söderlinh, J.; Schenk, F.; Gyllencreutz, R.; Rydberg, J.; Bindler, R.; Martínez Cortizas, A.; Skelton, A. It’s in your glass: A history of sea level and storminess from the Laphroaig bog, Islay (southwestern Scotland). Boreas 2020, 49, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Peiteado Varela, E.; Bindler, R. Reconstructing historical Pb and Hg pollution in NW Spain using multiple cores from the Chao de Lamoso bog (Xistral Mountains). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 82, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST 1568b; Rice Flour. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaitherburg, MD, USA, 2021.

- NIST 1648a; Urban Particulate Matter. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaitherburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- NIST 1649a; Urban Dust. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaitherburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- Quevauvillier, P.; Andersen, K.; Merry, J.; Van de Jagt, H. Certified Reference Materials Catalogue of the JCR; GROUND WATER (Br, Low Level); GROUND WATER (Br, High Level). 1998. Available online: https://crm.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Demšar, J.; Curk, T.; Erjavec, A.; Gorup, C.; Hocevar, T.; Milutinovic, M.; Možina, M.; Polajnar, M.; Toplak, M.; Staric, A. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 2349–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Francos Golán, A.; Traoré, M.; López-Costas, O. A Two-Part Harmony: Changes in Peat Molecular Composition in Two Cores from an Ombrotrophic Peatland (Tremoal do Pedrido, Xistral Mountains, NW Spain). Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Garson, D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Publishing associates: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016; pp. 1–262. Available online: http://www.statisticalassociates.com (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Horák-Terra, I.; Perez-Rodriguez, M.; Bindler, R.; Cooke, C.A.; Kylander, M. Structural equation modeling of long-term controls on mercury and bromine accumulation in Pinheiro mire (Minas Gerais, Brazil). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olid, C.; García-Orellana, J.; Masqué, P.; Martínez-Cortizas, A.; Sanchez-Cabeza, J.A.; Bindler, R. Improving the 210Pb-chronology of Pb deposition in peat cores from Chao de Lamoso (NW Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 443, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.J.; Campbell, C.D.; Fraser, A.R.; Puri, G. FTIR spectroscopy of peat in and bordering Scots pine woodland: Relationship with chemical and biological properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocozza, C.; D’Orazio, V.; Miano, T.M.; Shotyk, W. Characterization of solid and aqueous phases of a peat bog profile using molecular fluorescence spectroscopy, ESR and FT-IR, and comparison with physical properties. Org. Geochem. 2003, 34, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, R.R.E.; Chapman, S.J.; Robertson, A.H.J.; Potts, J.M.; Laggoun-Défarge, F.; Gogo, S.; Comont, L.; Disnar, J.R.; Francez, A.J. FT-IR spectroscopy can be used as a screening tool for organic matter quality in regenerating cutover peatlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhry, P.; Vitt, D.H. Fossil carbon/nitrogen ratios as a measure of peat decomposition. Ecology 1996, 77, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Sanei, H.; Outridge, P.M.; Miano, T.M. Studying the humification degree and evolution of peat down a Holocene bog profile (Inuvik, NW Canada): A petrological and chemical perspective. Org. Geochem. 2011, 42, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silamikele, I.; Nikodemus, O.; Kalnina, L.; Purnalis, O.; Sire, J. Properties of Peat in Ombrotrophic Bogs Depending on the Humification Process; Klavins, M., Ed.; Mires and Peat; University of Latvia Press: Riga, Latvia, 2012; pp. 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pipes, G.T.; Yavitt, J.B. Biochemical components of Sphagnum and persistence in peat soil. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 102, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, F.; Colom, X.; Sunol, J.J.; Saurina, J. Structural FTIR analysis and thermal characterisation of lyocell and viscose-type fibres. Eur. Polym. J. 2004, 40, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Cortizas, A.; Sjöström, J.K.; Ryberg, E.E.; Kylander, M.E.; Kaal, J.; López-Costas, O.; Álvarez Fernández, N.; Bindler, R. 9000 years of changes in peat organic matter composition in Store Mosse (Sweden) traced using FTIR-ATR. Boreas 2021, 50, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, J.; Bindler, R.; Martínez-Cortizas, A.; McClymont, E.L.; Abbott, G.D.; Biester, H.; Pontevedra-Pombal, X.; Buurman, P. Preferential degradation of polyphenols from Sphagnum–4-Isopropenylphenol as a proxy for past hydrological conditions in Sphagnum-dominated peat. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 150, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J. Current understanding of the correlation of lignin structure with biomass recalcitrance. Front. Chem. 2016, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duce, R.A.; Winshester, J.W.; Van Nahl, T.W. Iodine, bromine, and chlorine in the Hawaiian marine atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 1965, 70, 1775–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, S. Trace constituents in cloud water, rainwater, and aerosol samples collected near the west coast of India during the southwest monsoon. Atmos. Environ. 1980, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modanová, J.; Ljunström, E. Sea-salt aerosol chemistry in coastal areas: A model study. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, G.A.; Kempton, R.J. Bromine in soils and peats. Plant Soil 1982, 65, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, G.W. The diversity of naturally produced organohalogens. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, G.W. Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds—A Comprehensive Update; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 1–613. [Google Scholar]

- Keppler, F.; Biester, H. Peatlands: A major source of naturally produced organic chlorine. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, A.; Mayer, L.M.; Thornton, K.R.; Ravel, B. Bromination of marine particulate organic matter through oxidative mechanisms. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 142, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, S.C. Formation of stable chlorinated hydrocarbons in weathering plant material. Science 2002, 295, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pée, K.H.; Unversucht, S. Biological dehalogenation and halogenation reactions. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Seoane, R.; Antelo, J.; Fiol, S.; Fernández, J.A.; Aboal, J.R. Unravelling the metal uptake process in mosses: Comparison of aquatic and terrestrial species as air pollution biomonitors. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, P.; Zheng, G. Cellular and subcellular distribution and factors influencing the accumulation of atmospheric Hg in illandsia usneoides leaves. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkhi, M.C.; Taleb, F.; Gossart, P.; Semmoud, A.; Addou, A. Fourier transform infrared study of mercury interaction with carboxyl groups in humic acids. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2008, 108, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, M.; Roux, G.L.; Marusczak, N.; Heimburger, L.E.; Claustres, A.; Fu, X.; Sun, R.; Sonke, J.E. Atmospheric mercury transfer to peat bogs dominated by gaseous elemental mercury dry deposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2405–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, K.M.; Kane, E.S.; Potvin, L.; Lilleskov, E.A.; Kolka, R.K.; Mitchell, C.P. Gaseous mercury fluxes in peatlands and the potential influence of climate change. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 154, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Obrist, D.; Dastoor, A.; Jiskra, M.; Ryjkov, A. Vegetation uptake of mercury and impacts on global cycling. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tfaily, M.M.; Cooper, W.T.; Kostra, J.E.; Chanton, P.R.; Schadt, C.W.; Hanson, P.J.; Iversen, C.M.; Chanton, J.P. Organic matter transformation in the peat column at Marcell Experimental Forest: Humification and vertical stratification. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosciences 2014, 119, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, R.R.E.; Chapman, S.J.; Campbell, C.D. Substrate utilisation profiles of microbial communities in peat are depth dependent and correlate with whole soil FTIR profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2958–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.L.; O’Connor, R.T. Relation of certain infrared bands to cellulose crystallinity and crystal lattice type. Part II. A new infrared ratio for estimation of crystallinity in celluloses I and II. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1964, 8, 1325–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.M.; Singurel, G.; Popescu, M.C.; Vasile, C.; Argyropoulos, D.S.; Willför, S. Vibrational spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction methods to establish the differences between hardwood and softwood. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Langenfeld-Heyser, R.; Finkeldey, R.; Polle, A. FTIR spectroscopy, chemical and histochemical characterisation of wood and lignin of five tropical timber wood species of the family of Dipterocarpaceae. Wood Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrajt, G.; Muñoz Carro, G.M.; Dartois, E.; d’Hendecourt, L.; Deboffle, D.; Borg, J. FTIR analysis of the organics in IDPs: Comparison with the IR spectra of the diffuse interstellar medium. Astron. Astrophys. 2005, 433, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Cao, J.; Zhang, K.; Jiao, K.; Ding, H.; Hu, W. Artificial bacterial degradation and hydrous pyrolysis of suberin: Implications for hydrocarbon generation of suberine. Org. Geochem. 2012, 47, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).