Abstract

The development of urban green infrastructures (UGI) is considered among the main nature-based solutions for climate mitigation in cities; however, the role of soils in the carbon (C) balance of UGI ecosystems remains largely overlooked. Urban green spaces are typically dominated by constructed Technosols, created by adding organic materials on top of former natural or agricultural subsoils. The combined effects of land-use history and current UGI management result in a high spatial variation of soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and soil CO2 emissions. Our study aimed to explore this variation for the case of Wageningen University campus. Developed on a former agricultural land, the campus area includes green spaces dominated by trees, shrubs, lawns, and herbs, with well-documented management practices for each vegetation type. Across the campus area (~32 ha), a random stratified topsoil sampling (n = 90) was conducted to map the spatial variation of topsoil (0–10 cm) SOC stocks. At the key sites (n = 8), representing different vegetation types and time of development (old, intermediate, and recent), SOC profile distribution was analyzed including SOC fractionation in surface and subsequent horizons, as well as the dynamics in soil CO2 emissions, temperature, and moisture. Topsoil SOC contents on campus ranged from 1.1 to 5.5% (95% confidence interval). On average, SOC stocks under trees and shrubs were 10–15% higher than those under lawns and herbs. The highest CO2 emissions were observed from soil under lawns and coincided with a high proportion of labile SOC fraction. Temporal dynamics in soil CO2 emissions were mainly driven by soil temperature, with the strongest relation (R2 = 0.71–0.88) observed for lawns. Extrapolating this relationship to the calendar year and across the campus area using high-resolution remote sensing data on surface temperatures resulted in a map of the CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio, used as a spatial proxy for C turnover. Areas dominated by recent and intermediate lawns emerged as hotspots of rapid C turnover, highlighting important differences in the role of various UGI types in the C balance of urban green spaces.

1. Introduction

The recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlights the vulnerability of urban areas to climate change [1]. In this regard, city municipalities are motivated to work on climate mitigation strategies, including carbon (C) sequestration. The development of urban-green infrastructures (UGI) is considered an efficient nature-based solution for C sequestration [2,3]. The reported C sequestration potential of UGI ranges from 1 to 20 t C ha−1 year−1 depending on the UGI type (e.g., trees, shrubs or lawns), climatic conditions, and assessment method [4,5]. Many of these assessments are based on aboveground biomass and often overlook the contribution of urban soils to the C balance, which increases the uncertainty of the results and likely overestimates the expected C sequestration [6]. For example, a high net primary production of urban trees and shrubs is considered to determine tree-dominated UGI as C sinks [7,8]. However, high CO2 emissions from soils of urban green spaces can change some of the UGI from C sinks to C sources [9,10]. A comprehensive estimate of whether a UGI area functions as a C sink or a C source requires either long-term comparative assessments of C-stock dynamics in urban soils and plant biomass [11,12] or net ecosystem exchange monitoring by eddy-covariance in short-term [13]. Although these methods are considered standard for natural or agricultural areas, they are rarely applicable in urban environments due to the heterogeneity of urban green spaces, the high costs of equipment installation and maintenance in densely populated areas, and the limited accessibility of private and public green spaces for regular instrumental measurements [14]. In this regard, a comparative assessment of soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and soil CO2 emissions offers an alternative approach to approximating soil C-balance dynamics while accounting for the high spatial heterogeneity of urban areas [15]. Therefore, an improved insight into driving variables explaining spatial variability in SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions is important to assess the role of urban soils in the UGI C balance.

Urban soils vary from just affected by humans to fully human-made (i.e., constructed Technosols), and the genesis and land-use history of urban soils influence their SOC stocks considerably. Seminatural soils of urban forests and parks are usually not significantly different in SOC stocks from natural soils at similar lithological and climatic conditions [16]. However, C stocks in constructed Technosols range widely depending on the materials used for construction (e.g., peat, compost, or dredged sediments) and age–time passed after construction [17,18,19]. Land-use history has a stronger impact on subsoils properties of urban green spaces, whereas topsoil SOC stocks are more affected by management and maintenance of UGI [20,21]. The UGI type and corresponding management practices, such as mowing, pruning, and the addition of compost or other organic amendments, influence both the quantity and quality of SOC, including the ratio between stable and labile fractions [22,23,24]. Labile fraction is commonly represented by particulate organic matter (POM). POM is formed through the fragmentation and decomposition of the source material and largely consists of free organic matter particles that still retain identifiable characteristics of the source material. These particles may include above- and belowground plant litter, dead insects, and fungi [25]. During subsequent stages of decomposition, organic matter particles become smaller and eventually become water-soluble, after which they may become adsorbed onto mineral surfaces. This sorbed SOC fraction is referred to as mineral-associated organic matter (MaOM). MaOM is less susceptible to decomposition and is therefore considered to be more stable [26,27]. Soils under lawns usually contain a higher proportion of POM fractions compared to soils in tree-dominated areas [24,28,29].

Soil CO2 emissions in urban areas are even more variable than SOC stocks, especially at short distances. Local variability of CO2 emissions can be influenced by heterogeneous microclimatic conditions, anthropogenic disturbances, or UGI maintenance. For example, higher emissions from lawns compared to adjacent plots under trees and shrubs can be explained by a higher soil temperature, moisture, and proportion of POM fractions [29,30]. Pollution, over-compaction, or salinization are the anthropogenic factors hampering microbial activity and therefore decreasing soil CO2 emissions along the gradient from the disturbance source [31,32]. In contrast, maintenance of UGI, including irrigation and fertilization, stimulate microbial activity and root growth, resulting in higher soil CO2 emissions from intensively managed lawns compared to unmanaged lawns and herbs [33,34,35]. Temporal dynamics following the seasonal trends in soil temperature and moisture or responding to extreme events such as droughts or rainstorms makes exploring spatial patterns in soil CO2 emission even more challenging.

The ratio between microbial (heterotrophic) soil CO2 emission and SOC content/stock is traditionally used to characterize the spatio-temporal variability in C turnover and the degradability of soil organic matter in natural and anthropogenic biomes [36,37,38]. In urban areas, mapping half-life time was used to indicate locations where SOC stocks were the most vulnerable to urban heat island effect at the city scale or within park boundaries [39]. However, field partitioning of soil respiration into autotrophic and heterotrophic components, e.g., by trenching or root exclusion [40,41,42], is time- and labor-consuming which limits the number of monitoring locations. Moreover, these methods can result in disturbance of soil surface, which is usually not feasible in public urban green spaces. As an alternative, the ratio between total CO2 emissions and topsoil SOC stocks can be used as a proxy indicator of C turnover in soils of urban green spaces [43].

Analysis of factors driving the spatial variation of SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions of UGI is necessary to support decisions regarding the planning and management of urban green spaces. This analysis requires precise information UGI management and a thorough soil and vegetation survey, which is hardly feasible to obtain at a city scale. University campuses are unique research polygons, where such information is usually available and well documented; therefore, they are representative to observe diversity in vegetation and various management regimes [44,45,46]. This research aimed to study spatial variation of SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions at the Wageningen University campus. We hypothesized that UGI type would affect variation in topsoil SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions. We expect that the spatial patterns in SOC stocks, soil CO2 emissions and SOC decomposition will be informative to support decisions for ‘carbon-friendly’ UGI planning and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

Wageningen (51.9° N; 5.6° E) is located in the central part of the Netherlands. With an area of 32 km2 [47] and 40,000-resident population [48], Wageningen is representative for small and middle-size urban areas in northwestern Europe. The Wageningen area is quite diverse in relief, landscapes, and soils. Wageningen University and Research (WUR) campus occupies an area of 50 ha in the northern part of the town. The area belongs to the cover sand landscape formed by eolian sand deposits during the Weichsel ice age. Microrelief with ridges and flats, as well as the high ground water table (<1 m depth), have resulted in heterogeneous soils, including Podzols at the ridges and Gleysols in depressions. After long-term agricultural use, native soils have altered into sandy Anthrosols which dominated the area in 2000, when the university campus development started (Figure S1). Topsoil C contents of Anthrosols were approximately 4%, and the pH was close to neutral [49], which can be considered a baseline.

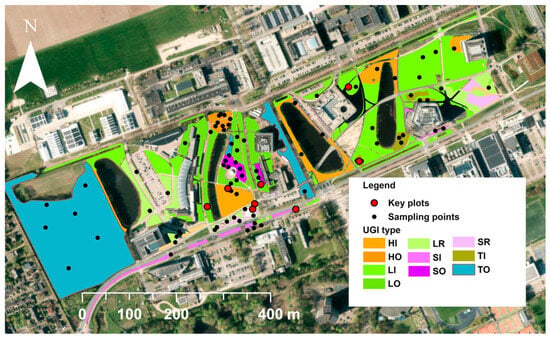

Campus development between 2000 and 2020 coincided with the creation of blue–green infrastructure, including trees, shrubs, lawns, and herbaceous meadows. The research area (~32 ha) contained patches of all these UGI types, which differed in their time of establishment: old (created before 2000), intermediate (created between 2000 and 2020), and recent (created after 2020). The combination of vegetation type and establishment period resulted in 10 distinct UGI types on campus, as no trees or herbaceous vegetation were planted after 2020. Each UGI type has a specific and well-documented management. For example, lawns are maintained at 7 cm grass height and are more frequently mowed than the herbaceous meadows, which are mowed 1–2 times per year (mowing clips are partly removed from both herbs and lawns). Old trees are unmanaged and leaves under old trees are not removed, whereas younger trees are annually pruned. Shrubs are manually pruned each spring to remove dead plant material. We are not aware of regular irrigation of any of the UGI types (irrigation was not mentioned in the available maintenance schemes), but during the dry summer period, lawns and herbs are likely occasionally irrigated. This UGI typology was used to develop a sampling and monitoring design for the field research (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

UGI types sampling locations and monitoring key plots on top of the aerial photograph (2023). HI—intermediate herbs, HO—old herbs, LI—intermediate lawns, LO—old lawns, LR—recent lawns, SI—intermediate shrubs, SO—old shrubs, SR—recent shrubs, TI—intermediate trees, TO—old trees.

2.2. Research Approach

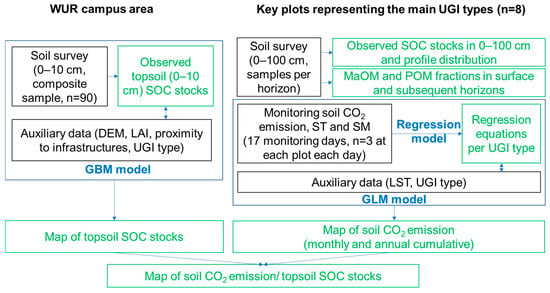

This study aimed to analyze the spatial variation in SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions of the campus area and to explore driving factors of this variation. The following research steps were taken: (1) for the campus area, a random stratified topsoil sampling (n = 90) was done to explore spatial variation of topsoil (0–10 cm) SOC stocks; (2) at the key plots (n = 8) representing different UGI types, SOC profile distribution was analyzed; SOC in the surface and subsequent horizons was size-fractionated to particulate organic matter (POM, >50 µm) and mineral-associated organic matter (MaOM, <50 µm); soil CO2 emissions, temperature, and moisture were observed during September 2022–January 2023 and April 2023–May 2023; (3) topsoil SOC stocks were mapped by the Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) model; (4) soil CO2 emissions were mapped by the General Linear Model (GLM); (5) spatial patterns in annual soil C-CO2 emissions/topsoil SOC stocks ratio were analyzed to characterize C turnover. The overall research workflow is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research workflow scheme: data collection (black), data analysis, and modelling (blue) and research outcomes (green).

2.3. Soil Survey and SOC Stocks’ Spatial Variation on Campus

A soil survey was carried out on campus in autumn of 2022. A total of 90 sampling locations were selected based on the random stratified sampling design with 9 random samples from each of 10 UGI types. At each location, a composite topsoil (0–10 cm) sample was taken with an Eijkelkamp auger and a bulk density sample was taken with a 100 cm3 metal ring. The bulk density rings were closed and stored at <4 °C for no longer than a week before drying at 105 °C. Rock fraction was calculated by sieving at 2 mm and weighing the fraction > 2 mm. The composite samples were air dried and SOC contents were analyzed by loss-on-ignition (LOI) method [50]. In the processed samples, SOC stocks were estimated following Formula (1)

where

SOC st—SOC stocks (kg C m−2);

SOC—SOC content (%);

BD—bulk density (g cm−3);

D—depth of horizon (cm);

RF—rock fraction (%).

2.4. SOC Analysis and Monitoring Soil CO2 Emissions at the Key Plots

From the sampled 90 locations on campus, eight key plots were selected for a more detailed investigation of factors and processes influencing SOC dynamics, including SOC profile distribution, SOC fractionation, and monitoring dynamics in soil CO2 emissions. The key plots included old, intermediate, and recent lawns and shrubs, as well as intermediate trees and herbs.

At each key plot, a soil profile was augured to 100 cm depth, and the soil color, texture, and structure were described on site. Composite soil samples were taken per horizon (subsamples from different depths within the same horizon were mixed) for further analysis of SOC contents by the LOI method. At each location, the organically rich top horizon A (0–10 cm) and subsequent mineral (B or C) horizons were analyzed for POM and MaOM contents by size fractionation. The POM and MaOM fractions can be quantified through either size or density separation [51]. We used size separation as a less time-consuming and more environmentally friendly approach (toxic chemicals are not used). The collected soil samples were dried at 40 °C and sieved at 2 mm. A subsample of 10 g was taken, and 40 mL of 5.00 g/L NaHMP was added to disperse the samples by shaking at 180 rpm for 17 h. After shaking, the soil samples were wet-sieved to distinguish fractions ≤ 50 µm (MaOM) and >50 µm (POM). The results were expressed as the proportion of each fraction relative to total SOC content and interpreted to explore the potential resistance of SOC to biodegradation. A higher proportion of POM may stimulate microbial activity due to a higher availability of easily decomposable organic matter and therefore increase soil CO2 emissions, especially under warm and humid conditions that are favorable for soil microorganisms.

Soil CO2 emissions (including both autotrophic and heterotrophic components) were monitored during September 2022–January 2023 and April–May 2023 at an approximate 10-day interval. At each of the eight key plots, three spatial replicates were measured to account for short-distance variability. An infrared gas analyzer (EGM-5, PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) was used to measure CO2 fluxes, while soil temperature and moisture were recorded using HH2 and ML3 ThetaProbe sensors (Delta-T Devices, Burwell, UK) to characterize abiotic conditions. All measurements were conducted under rainless conditions between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. to better represent average daily CO2 efflux, following previous studies and methodological recommendations [10,52]. To calculate the total soil CO2 emissions for the calendar month, the daily values obtained during the month were averaged and multiplied by the number of days.

2.5. Data Analysis and Mapping

SOC stocks for the entire campus area have been predicted by digital soil mapping [53]: a statistical model (GBM) (caret package in R 4.3.1) with a set of predictors: UGI type and age, Leaf Area Index (LAI), elevation, slope, and proximity to roads and buildings. The choice of this approach was based on hypothesized non-linear relationships between SOC stocks and independent variables [54]. Elevation and slope were derived from a 0.5 m resolution Digital Terrain Model (AHN4, [55]). The EO-Browser [56] was used to retrieve LAI data based on 10 m resolution Sentinel-2 satellite image for 14 June 2023, which was the day with the lowest cloudiness for the research period. Building and road shapefiles were obtained from the Open Street Map service and proximity was estimated by Euclidian distance tool. In the modelling, the LAI, elevation, slope, and Euclidian distances to buildings and roads were continuous variables, and UGI type (or vegetation and age) were categorical (dummy) variables. We have tested different tuning parameters for the GBM model where the optimal set (with the lowest RMSE) of parameters were as follows: number of trees: 300, shrinkage: 0.01, minimum observation in node: 5, interaction depth: 7. Model uncertainty was assessed by 10-fold cross-validation (RMSEcv). Mapping (prediction) was performed in R using terra package; all raster predictors were resampled to the resolution (2.6 m) and extent of the UGI type raster.

Analysis of spatial variation in soil CO2 emissions on campus was constrained by a limited number of observation points (n = 8), which is a typical problem for long-term monitoring studies. To overcome this problem, we (1) analyzed the effect of UGI type (location) and observation period (measurement date) on soil CO2 emissions by a repeated-measures ANOVA; (2) tested the effect of dynamics in abiotic factors (soil temperature, soil moisture, and their combination) on soil CO2 emissions during the season by multiple linear and non-linear (exponential and quadratic) regression models separately for each location and for the whole area (when data from each location was merged in a single dataset); (3) approximated relationship between CO2 emissions, UGI type, and relevant abiotic factors by general linear model (GLM), in which abiotic factors were included as continuous predictors and UGI type (or vegetation and age) as categorical (dummy) variables. Analysis was performed in R using the caret package.

To obtain a continuous map of soil temperature across the campus area, remote sensing data validated by on-ground measurements were used. Brightness temperature (BT) data were obtained from Landsat 8 and 9 imagery for the period from June 2022 to May 2023. Land surface temperature (LST) was retrieved from BT using the Statistical Mono-Window (SMW) algorithm [57], which accounts for atmospheric water vapor content (cm) at the time of satellite overpass through the use of empirical coefficients and incorporates predefined surface emissivity values. Surface emissivity was derived from Sentinel-2–based land cover classification, allowing the final LST product to be generated at a spatial resolution of 10 m.

Emissivity for eight land cover classes (water, urban low albedo, high albedo, urban color, bare soil, trees, shrubs, and lawns) was prescribed for Sentinel-2 median composite over the summer season of 2023: emissivity values were taken from ASTER spectral library [58], as in [59], and were re-calculated from ASTER spectral bands 13 (10.25–10.95 μm) and 14 (10.95–11.65 μm) to be suitable for Landsat-8/9 thermal infra-red band 10 (10.6–11.19 µm) using regression coefficients from [60]. Water vapor coefficients for SMW were retrieved using a specially developed algorithm available on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud computing platform [61]. In total, 24 scenes were selected to characterize dynamics in soil temperature during the research periods. The modelled LST was validated by field data at the observation points, and the resulting regression equation was used to calibrate the model. The resulting soil temperature layers, together with the UGI layer, were used as auxiliary data to map soil CO2 emissions on campus for the day of each scene based on the best fitted GLM model. In result, the maps of monthly averaged soil CO2 emissions were developed and aggregated to the map of total annual soil C-CO2 emissions. Finally, the map of annual soil C-CO2 emissions was overlaid with the map of SOC stocks in 0–10 cm layer to map the spatial variability in soil C emissions/stocks ratio as a proxy of soil C turnover. Statistical analysis was performed in R Studio 4.3.1 software. ArcGIS Pro 3.0 and QGIS 3.32.3 were used for spatial modelling and mapping.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Variability in Topsoil SOC Stocks on Campus

Field-based topsoil SOC contents on campus ranged from 1.0 to 9.2% with a 95% confidence interval from 2.7 to 3.4%. Bulk density ranged from 0.4 to 1.5 g cm−3 with an average 1.1 ± 0.2 (mean ± standard deviation). Maximal rock fraction reached 14%; however, the 95% confidence interval ranged from 2.5 to 3.6%, and in some locations, rock fraction was not observed in topsoil. Topsoil SOC stocks on campus were normally distributed (p > 0.2, K-S test) with a 3.1 kg m−2 mean, a 3.0 kg m−2 median, and a 95% confidence interval from 2.8 to 3.3 kg m−2.

The GBM model has shown, the partial importance of all the predictors considered, where slope and elevation had the highest relative influence (23.8 and 21.6%), LAI—18.9%, and distances to roads and buildings—11.1 and 11.8%, respectively. Among the categorical variables, the age factor had the highest importance—6.8%. The model RMSEcv was 0.9 kg m−2, mostly underestimating high stocks (>4 kg m−2). Soils under trees had higher SOC stocks compared to herbs, whereas the difference with the other UGI types was not significant due to high spatial variation within UGI types. SOC stocks under recently developed UGI (mainly, lawns, and shrubs) were higher compared to intermediate and old UGI (Figure S2). SOC stocks were negatively related to elevation (higher stocks in local depressions) and positively related with distance to buildings (lower stocks near the buildings compared to the remote areas). The SOC stocks predicted by the GBM model were in good agreement with the observed values (R2 = 0.68, RMSE = 0.58).

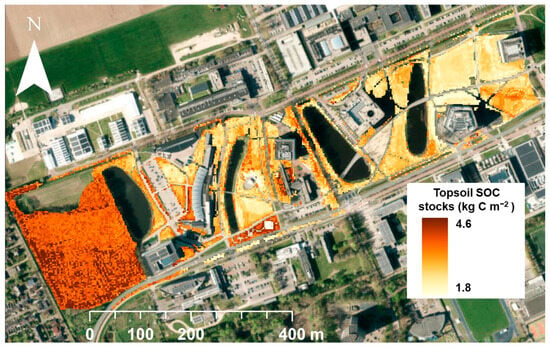

Based on the resulting map, the highest SOC stocks were localized in the western part of the campus, where elevation is 1.5–2.0 m lower compared to the eastern part, and old trees were the dominating UGI type. Several spots with high SOC stocks were also observed in the central part of the campus part where lawns and shrubs were recently planted. The lowest SOC stocks were observed at the eastern part dominated by intermediate lawns and exposed to a higher anthropogenic disturbance (based on proximity to the main educational buildings) than the other parts. Patches with higher SOC stocks in the eastern part of campus coincided with recent lawns and shrubs or local depression in relief near artificial ponds belonging to the intermediate trees UGI type (Figure 3). The predicted topsoil SOC stocks on campus varied between 1.8 and 4.6 kg C m−2 with an average 3.1 ± 0.3 kg C m−2 (mean and standard deviation). The total topsoil SOC stocks for the unsealed area of the campus (~26 ha) was 388.5 ± 107.8 ton C (mean ± standard deviation).

Figure 3.

Topsoil SOC stocks of the Wageningen University campus area.

3.2. SOC Profile Distribution and Fractionation at the Key Plots

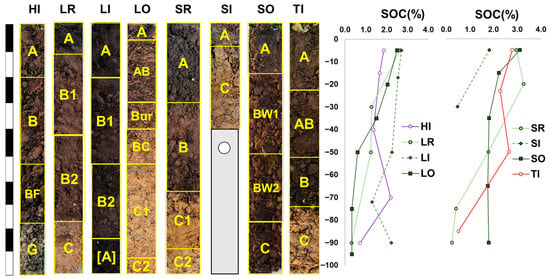

High variability of SOC stocks observed for topsoil became even more evident when the soil profiles excavated at the key plots were compared. Soil profile depth reached 100 cm at all locations except for intermediate shrubs (SI), where a concrete slab was observed at 40 cm depth (Figure 4). This plot was near the bus lane, and the slab was likely a part of the road basement. The depth of A horizon ranged from 7 cm (old lawns, LO) to 30 cm (recent shrubs, SR). Topsoil of recent shrubs (SR) and lawns (LR) was thicker compared to the old ones (LO). The depth and density of fine roots, assessed visually during field description of soil profiles, were considerably higher under lawns compared to the other UGI types. Soil texture was mainly sand and loamy sand throughout all the profiles, excluding loamy Bw horizons in the profile under the old shrubs (SO). This profile appeared to be the most similar to a natural Cambisol (brown forest soil), whereas the other profiles evidenced anthropogenic genesis via abrupt boundaries between the horizons and inclusions of artefacts (e.g., bricks, glass, and concrete fragments) (Figure 4). Most artefacts were observed under lawns, whereas profiles under old shrubs (SO), intermediate trees (TI) and shrubs (SI) were less anthropogenically altered. A buried [A] horizon described at 90–100 cm depth under intermediate lawns (LI) indicates former agricultural use. The presence of a gley horizon in the subsoil under intermediate herbs (HI) indicates seasonal water logging (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Soil profiles and profile distributions of SOC content at the key plots (HI—intermediate herbs, LI—intermediate lawns, LO—old lawns, LR—recent lawns, SI—intermediate shrubs, SO—old shrubs, SR—recent shrubs, TI—intermediate trees), yellow rectangles and letters on soil profile pictures show soil horizons, measuring tape unit (black or white) on the left part is 10 cm, Y axis on the right part refer to soil depth. The circle and the gray shading illustrate the concrete layer and pipeline underlying the C horizon in SI.

The described soil profile characteristics were reflected in the vertical SOC distribution. The least-disturbed soil under old shrubs had a typical accumulative profile with a gradual decrease of SOC contents from top to bottom. The SOC content of the buried A- horizon (LI) was similar to topsoil values and almost double of the overlaying B horizon (Figure 4). The highest SOC stocks of the full 0–100 cm profiles, calculated based on SOC contents, observed bulk densities of A-horizons and literature-based bulk densities of 1.1 g cm−3 for subsoil horizons [31], were obtained for intermediate lawns and trees and old shrubs ranging from 16 to 20 kg m−2, whereas SOC stocks under old and recent lawns were less than 10 kg m−2. Subsoils (layers below 30 cm) contributed from 35 to 75% of the total SOC stocks.

SOC size-fractionation analysis showed that the <50 µm (MaOM) C-fraction dominated at all locations, but the ratio of the <50 µm (MaOM) and >50 µm (POM) C-fractions differed between the sites and depths. On average, the POM C-fraction in surface A-horizon (0–10 cm) was 30%, which was twice as large as in the subsequent mineral horizon (C for SI and B for all the other locations). The largest POM C-fraction in topsoil SOC was observed under intermediate lawns and herbs; topsoil SOC under recent shrubs and intermediate trees had the largest MaOM C-fractions. The ratio between MaOM and POM C-fractions under trees did not differ between topsoil and subsoil, whereas under lawns, the ratio in subsoil was two to three times higher than in the topsoil (Table 1).

Table 1.

SOC concentration (mg C g−1 soil) in the MaOM (≤50 µm) and POM (>50 µm) C-fractions.

3.3. Spatio-Temporal Variation in Soil CO2 Emissions at the Key Plots

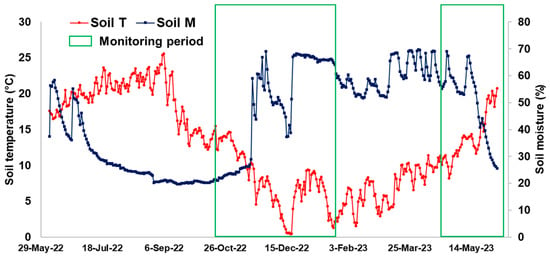

Soil CO2 emissions, temperature, and moisture at the key plots were monitored during two periods: October 2022–January 2023 and April 2023–May 2023. During these observation periods, soil temperature ranged from 0 to 26.2 °C, and soil moisture ranged from 10 to 58%. The ranges of soil temperature and moisture conditions were similar to those observed for the period June 2022–June 2023 at the nearby Veenkampen meteorological station, which is considered as a reference for the campus area. Therefore, the selected observation period was representative for the annual variation in soil temperature and moisture (Figure 5) and was relevant for estimating annual soil C-CO2 emissions from different UGI types.

Figure 5.

Annual dynamics of soil temperature and moisture at the Veenkampen meteorological station and periods of soil respiration monitoring on campus.

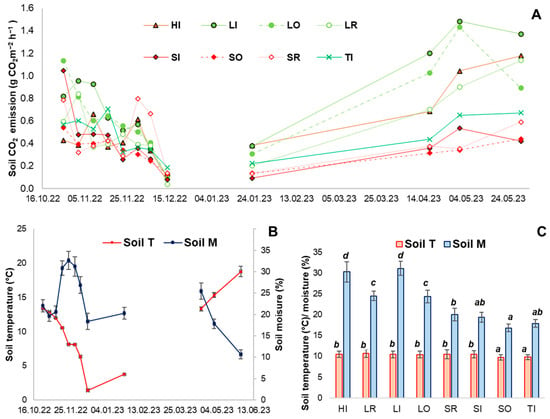

According to the repeated-measures ANOVA, the combined effects of UGI type and observation date explained 68%, 69%, and 98% of the total spatio-temporal variation in soil CO2 emissions, soil moisture, and soil temperature, respectively. Soil temperature was mainly driven by seasonal dynamics, whereas 26% of variation in soil moisture was explained by UGI type. Lawns and herbs were on average warmer and significantly wetter compared to shrubs and trees. Both factors and their combination (UGI type × observation date) had a significant effect on variation in soil CO2 emissions (p < 0.05). Over the course of the season, soil CO2 emissions across all plots showed a gradual decline from October toward winter, followed by an increase from April to the end of May. This pattern is characteristic of temperate climates and mirrors the seasonal variation in soil temperature. Among the UGI types, the highest average soil CO2 emission was observed in intermediate and old lawns, coinciding with the highest density of root biomass and proportion of the POM fraction in topsoil SOC in these UGI types. Average CO2 emissions from soils under shrubs and trees were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than those from lawns and herbs (Figure 6). This pattern was also consistent with the topsoil POM fraction, which was, on average, 30–60% lower under trees and shrubs compared to lawns and herbs.

Figure 6.

(A): Seasonal dynamics in average soil CO2 emission (mean for each plot per observation date); (B): seasonal dynamics in soil temperature and moisture (mean and standard error for all plots per observation date); (C): average (mean and standard error for the observation period per plot) soil temperature and moisture. HI—intermediate herbs, LI—intermediate lawns, LO—old lawns, LR—recent lawns, SI—intermediate shrubs, SO—old shrubs, SR—recent shrubs, TI—intermediate trees). Letters on bar plots C show homogeneous groups based on ANOVA post-hoc LSD test.

Seasonal variation in soil CO2 emissions was strongly driven by soil temperature. When results from all plots were analyzed jointly, the exponential model was significant (p < 0.05) but explained only 32% of total variance. Modelled relationships between soil CO2 emissions and soil temperature for each plot separately explained from 30% (SI, R2 = 0.3) to 80% (LI, R2 = 0.8) of total variance. The effect of soil moisture as well the combined effect of soil moisture and soil temperature, on soil CO2 emissions were not significant at any of the sites (based on both linear and quadratic models). Therefore, soil moisture was not included in the further spatial modelling.

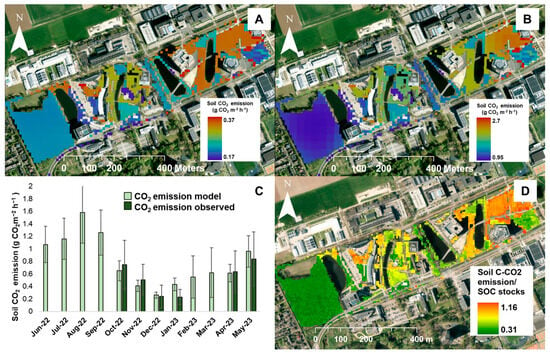

3.4. Spatio-Temporal Variation in Soil CO2 Emissions Extrapolated to the Campus Area

The relationships between soil CO2 emissions, UGI type and soil temperature were approximated by GLM model, where the natural logarithm of CO2 emission was a dependent variable, soil temperature was a continuous predictor, and UGI type was a categorical predictor. The resulting model was significant and explained 58% of the total variance (R2 = 0.58, p < 0.05). This model was used to extrapolate the point measurements of soil CO2 emissions in space (for the whole campus area) and time (for a calendar year period—from June 2022 to May 2023). Due to the lack of a spatially explicit soil temperature dataset for the campus area, soil temperature was approximated using remote-sensing–derived LST validated by on-site measurements. The resulting LST patterns were consistent with observational data, with minimum temperatures in the western forested area and maximum temperatures in lawn and herbaceous areas in the central and eastern sections. While most pronounced in summer, these spatial patterns were detectable throughout the year. The seasonal dynamics in LST was also similar to the field observations; however, the absolute values of Landsat-8/9 LST overestimated the real soil temperature. The validation by field measurements showed a significant correlation (R2 = 0.75; p < 0.05), but an error was substantial (ME = 1.7 °C; RMSE = 5.8 °C). To reduce the error, the estimated temperatures were adjusted based on the regression model of relationship between observed temperatures and temperatures derived from LST at the same location. The following equation was obtained: STadj = 5.03 + 0.49 × LST, where STadj—the adjusted estimate of soil temperature (°C) and LST—land surface temperatures based on remote sensing. The final GLM model used STadj and UGI type layers as covariates to map soil CO2 emissions on campus.

At first, soil CO2 emission maps were developed for each of 24 days, for which LST scenes were available. Then, average monthly soil CO2 emission maps were created based on the maps for each calendar month. Finally, the map of total annual soil CO2 emission was created based on the monthly maps (Figure 7). The lowest monthly soil CO2 emission was 0.26 ± 0.05 g CO2 m−2h−1 (mean ± standard deviation), obtained for December 2022. The highest values were obtained for August and September 2022, when soil CO2 emission reached 1.58 ± 0.49 and 1.26 ± 0.36 g CO2 m−2h−1 (mean ± standard deviation), correspondingly. Lawns located close to educational buildings and main road at the eastern part of the campus were the hotspots on the CO2 emission maps. The forested area was the largest zone with low soil CO2 emissions in summertime, whereas in winter, the lowest CO2 emissions were obtained for parcels of old and intermediate shrubs in the central part of the campus (Figure 7A,B). Comparison between the modelled and observed monthly average soil CO2 emissions at the key plots showed high significant correlation (R2 = 0.88, p < 0.05). The model slightly overestimated average soil CO2 emissions during the cold period (December–January) and underestimated it in autumn and spring (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Modelled spatial variation in monthly average soil C-CO2 emissions in August 2022 (A) and December 2022 (B); seasonal dynamics in modelled and observed monthly average soil C-CO2 emissions (mean and standard deviation for all plots per month) (C); and spatial patterns in soil C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio (D).

Annual soil C-CO2 emissions per UGI type ranged from 1.3–1.4 kg C m−2 for old and intermediate shrubs to 2.2–2.4 kg C m−2 for old and intermediate lawns. Total C-CO2 emission from the campus area was 49.3 ± 19.5 ton C (mean ± standard deviation), which was approximately one-sixth of the SOC stocks in 0–10 cm in the area. The ratio of annual soil C-CO2 emission and SOC stocks in 0–10 cm ranged from 0.31 to 1.16. The lowest ratio was shown for the forested area in the western part and tree parcels in the central part of the campus area—here, annual soil C-CO2 emissions were about one-third of SOC stocks in 0–10 cm. The areas with the highest soil C emission/stocks ratio were obtained for the central and eastern parts and mainly coincided with recent and intermediate lawns located close to buildings and roads. Annual soil C-CO2 emission here were comparable or even higher to SOC stocks in the 0–10 cm layer (Figure 7D).

4. Discussion

4.1. SOC Stocks on Campus in Comparison to Other Urban Studies

C-smart (low-C) solutions are implemented in planning green infrastructures at the city or district scale, as it was described for Tehran (Iran) [62], Tbilisi (Georgia) [63], and Berlin (Germany) [64]. Soil information in these studies is limited to average SOC stocks per soil group or administrative district and is considered as baseline values.

Diversity of UGI types at the university campus makes it possible to compare the estimated SOC stocks to the results obtained for similar green spaces in other urban areas and to explore the impact of UGI management and maintenance on SOC stocks in and CO2 emission from urban soils. Average topsoil SOC stocks at the campus area (3.1 ± 0.3 kg m−2) were close to 3.3 and 3.8 kg m−2, obtained, correspondingly, in Paris (France) and in New York (USA) [65], slightly higher than 2.4 kg m−2 reported for Moscow (Russia) [39,66] but lower than 5.5 kg m−2 in Berlin (Germany) [64]. Global reviews show a wider range in urban SOC stocks depending on the climatic conditions, land-use history, and management, but a global average 3.0 ± 1.0 kg m−2 (mean ± standard error), ref. [67] is very close to the obtained results. It may be concluded that the area of Wageningen University campus, with its long history of greening and landscaping, diversity of UGI types, and managements, is representative to study soils of public urban green spaces and factors driving C cycling in these soils, for example, in the format of an Urban Living Lab [68].

4.2. The Effect of UGI Typology on SOC Stocks and CO2 Emissions

On campus, UGI typology was one of the main factors explaining spatial variation in SOC stocks and CO2 emissions with the most substantial differences between trees and lawns. Comparative analysis of C stocks and fluxes in woodlands and lawns becomes an emergent topic in urban environmental studies aiming to determine a balance between woody and grassy components of urban vegetation and enhance ecosystem services of green infrastructures [69,70,71]. In recent research of urban soils in Den Haag (The Netherlands) [72], SOC stocks under trees and shrubs were also significantly higher than under lawns and herbs, which confirms our findings. This is the only available research of urban SOC stocks in the Netherlands; however, similar patterns were found for many cities in temperate climate such as Helsinki (Finland) [73], Baltimore (USA) [69], and Rostov-on-Don (Russia) [19]. This pattern is explained by a different ratio between C inputs from aboveground biomass and C effluxes from soil microbial respiration, as well as by different proportion of the POM and MaOM fractions of SOC [74].

Under tree canopies, a litter layer provides a substantial source of organic substrates with different decomposition rates: faster for leaves and slower for needles and branches [7,75]. In lawns, biomass is harvested by regular mowing, and grass clips are usually removed [76,77]. Partly, organic matter is returned to the lawn ecosystem by composting; however, compost is exposed to fast biodegradation due to a high POM fraction and does not increase soil C stocks in the long term [78,79]. This difference in C inputs is reflected in the ratio between labile and more stable fractions of soil organic matter. On campus, POM C-fraction in soils of lawns was, on average, 25% higher compared to trees and shrubs, resulting in higher soil CO2 emissions from lawns. Similar patterns were observed in the studies in Chengdu (China) by [80], where the fraction of labile soil organic matter under lawns was two times higher than under plantations of deciduous trees of the same age.

The amount of fast-cycling labile carbon (POM) largely determines soil respiration rates [81,82], especially in favorable abiotic conditions. A high content of labile organic matter, combined with elevated surface temperatures, favorable soil moisture, and readily available nutrients, is characteristic of soils under managed lawns [24,83]. These conditions stimulate microbial activity and contribute to soil CO2 emissions [30,84]. The shading effect of tree canopies reduces the soil surface temperature under trees of 2 °C or more and results in a consequent decrease of soil respiration of 30–50% [4,85]. As a consequence, soils in lawn areas generally release more CO2 than soils beneath trees and shrubs. Across the campus, average soil CO2 emissions from lawns exceeded those from tree-dominated areas by approximately 20–30%. The highest difference was shown during the spring–summer period. For example, soil CO2 emissions from the intermediate lawns in May–August was two to three times higher as compared to the intermediate trees, whereas in December, soil CO2 emissions at both sites were about the same. Similar or even higher soil respiration under lawns in comparison to nearby trees and shrubs were shown in Angers (France) [27], West Lafayette (USA) [86], and Moscow (Russia) [10]. In all these studies, soil temperature was reported among the main drivers behind spatio-temporal variation in soil CO2 emissions.

4.3. The Effect of UGI Age on SOC Stocks and CO2 Emissions

Although UGI typology and management were the main factors explaining variation in soil CO2 emissions and topsoil SOC stocks, land-use history and UGI age (time passed after UGI construction) can be comparably important, especially when subsoil horizons are taken into consideration. For example, ref. [87] Pataki et al. (2006) showed that SOC stocks in urban lawns decreased during the first years after construction but subsequently increased afterwards and became a sustainable C sink only 50–80 years after creation. A similar approach followed by simulations with the CENTURY model showed that turfgrass lawns can be C sinks but only from 40 to 80 years after establishment [12,27]. In the long term, SOC stocks in urban soils shall be analyzed in the context of their stage of anthropedogenesis—a man-driven pedogenic evolution [88,89]. In a natural, non-anthropogenic setting, soil evolution starts from low-C parent material followed by a gradual increase of SOC stocks by the humification of C inputs from biomass, while the pattern observed for urban soils can be almost opposite. High-SOC stocks artificially created by adding C-rich materials can be depleted rapidly due to microbial decomposition intensified by fertilization, irrigation, and urban heat island effects [18,39]. For example, topsoil SOC stocks in Technosols constructed from peat in Moscow (Russia) reduced by half during the first year after construction, and a considerable amount of CO2 was released [79,90]. Similarly, Technosols’ C stocks in Lorraine (France) decreased almost 40% during the first three years and stabilized at values similar to natural soils [91].

The effect of UGI age on SOC stocks and CO2 emissions can be confirmed by our research outcomes. The highest SOC stocks were observed under the old trees where soil was undisturbed and organic amendments were not added for at least several decades. However, for lawns, where soils were mostly artificially constructed from C-rich materials, topsoil SOC stocks in old patches (constructed before 2000) were lower than in the recent ones. In intermediate (created between 2000 and 2020) lawns and shrubs, POM fraction and correspondingly CO2 emissions were higher compared to the old sites (created before 2000). This pattern can be further illustrated by the MaOM/POM C-ratio in A-horizons in comparison to B or C horizons. Under lawns, the topsoil MaOM/POM C-ratio was three times lower than in the deeper horizons, whereas under trees, the difference between horizons was insignificant.

4.4. Spatial Patterns in Soil C-CO2 Emissions/SOC Stocks Ratio

The effect of UGI types and age on soil C balance became the most visible when the spatial patterns in soil CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio were analyzed and mapped. Lawns were the hotspots on the map, with soil C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio equal or above one with the highest values observed for a large lawn patch created after year 2000 in the eastern part of campus. For trees, the C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio was within the range of 0.3–0.5, with the lowest values obtained for the old forest area in the western part of campus. The C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio was spatially correlated with surface temperature, which increased following the gradient from old forest in the eastern part to open lawn spaces in the western part. A similar spatial dependency but at a city scale was shown for the SOC decomposition rate (ratio between microbial respiration and SOC contents), increasing along a rural–urban gradient in Nanchang (China) [92] and Moscow (Russia) [39]. At the city scale, the spatial pattern in the SOC decomposition rate was explained by mesoclimatic conditions, and the highest values coincided with urban heat island in the city centers. On campus, a similar effect can be expected from micro-climatic conditions. A substantial part of the WUR campus area (to the east from the pond and between the main educational buildings) is dominated by spacious lawn areas where tree patches are minimal. These areas, where a high proportion of POM fraction in SOC coincided the highest soil temperatures, showed the highest C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio. This ratio cannot be considered a direct equivalent of the SOC decomposition rate, which is estimated based on the microbial (basal) respiration measured in standardized laboratory conditions [37,38,93]. In our research, soil CO2 emissions were estimated in situ and included both root and microbial components. Considering that contribution of microbial component to total soil respiration is approximately 50–60% for grasses and 70–80% for woodlands [40,94], we likely overestimate SOC decomposition. However, high values of the C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio can indicate the risk zones where CO2 emission cannot be compensated by C accumulation in topsoil and additional measures to increase C sequestration should be implemented.

4.5. Uncertainties of the Outcomes and Potential Implementation for Decision-Making

The statistical models used for digital mapping of SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions explained 25 and 58% of the total variance correspondingly. These determination coefficients are reasonable compared to other urban soil studies [95,96,97], but the results are still quite uncertain. With a limited dataset of in situ soil CO2 emission measurements (17 daily measurements within a calendar year), the extrapolation of annual CO2 emissions relied on several assumptions, which contributed to uncertainty. For example, the lack of observations during the driest period (July and August) may lead to an underestimation of total effluxes and could particularly overlook the effect of soil moisture. Although soil moisture did not show a significant effect on soil CO2 emissions based on available observations, it is difficult to confirm this assumption without considering the extreme values in the soil moisture distribution. Additional uncertainty was propagated from the experimental and auxiliary data. For example, LST retrieval from thermal infrared images (MODIS, ASTER, Landsat) is always a trade-off between resulting spatial resolution and data accuracy. The highest uncertainty in LST retrieval lies in the prescription of emissivity, which is especially relevant for the urban environment [98]. In our research, we applied a Sentinel-2 classification-based emissivity within the SMW algorithm, with values taken from the ASTER spectral library [58] and adapted to Landsat acquisitions. It helped to increase the resolution to 10 m, but at the same time, it could be the main reason for the overestimations in LST. Indeed, an error of 0.01 in emissivity is propagated into an error of 0.5 °C in LST [59]. In heterogeneous urban environment, a classification-based emissivity algorithm shall be validated against in situ LST for the accurate modelling of soil temperature and respiration. We partly managed to reduce the uncertainty by calibrating the modelled LST based on the in situ soil temperature measurements, but the density of monitoring points and frequency of observations did not perfectly match with the spatial and temporal resolution of the images.

Although the absolute values may be uncertain, the spatial patterns in SOC stocks, soil CO2 emissions, and C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio are relevant and highlight that domination of open lawns can have negative consequences for C balance. It does not mean that the total area of lawns on campus shall be minimized, since they provide multiple environmental, recreational, and aesthetic services that cannot be compensated by other UGI types [5,99,100]. The obtained information can support decision-making in sustainable and ‘C-smart’ management and maintenance of urban green infrastructures. For example, field observations of C stocks and fluxes in several backyard green spaces in Chicago (USA) showed the effects of pruning, moving, irrigation, and fertilization on C balance [101]. The study highlighted that woody areas were C sinks, whereas lawns were C sources, especially when the hidden C costs of gasoline for mowing machines or energy consumption for irrigation were considered. At the same time, introducing trees and shrub patches and making green corridors can be a promising solution which will create additional shading and support biodiversity [102,103]. More specific recommendation, e.g., on the intensity of mowing, fertilization, or composting, shall be supported by a more detailed survey, which was not the aim of our research. However, such a survey could be implemented using the concept of a university campus as an Urban Living Lab [68]. Considering that European Commission regards Living Labs an efficient tool for analyzing and improving soil health, and that the Soil Deal for Europe calls for the establishment of at least 100 living labs by 2030 [104,105], Living Labs focused on urban soil functions could make a valuable contribution.

5. Conclusions

Urban green infrastructure plays a critical role as a nature-based climate mitigation solution; nonetheless, a comprehensive and unbiased evaluation of its carbon sequestration potential requires explicit consideration of urban soil contributions to SOC storage and CO2 emissions. For the case of Wageningen University campus, representing a wide diversity of UGI types, we explored the main factors driving spatial variation of SOC stocks and soil CO2 emissions. Considering topsoil SOC stocks, ratios between mineral associated (MaOM) and particulate organic matter (POM) fractions, and the C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratio, soils under trees were shown as the most efficient in C accumulation, whereas lawns were potential C sources. High POM C-fraction content likely originated from organic amendments and materials added for soil construction. Moreover, lawn maintenance caused high soil CO2 emissions, which were intensified by favorable microclimatic conditions. As a result, SOC stocks under old lawns were lower compared to the recent ones, which was the opposite trend compared to what can be expected under natural conditions.

Extrapolating point observations of soil CO2 emissions based on general linear regression model with UGI type and soil temperature (adapted from remote-sensing LST and adjusted by field observations) highlighted that open lawns in the eastern part of campus were hotspots with respect to C-CO2 emissions/SOC stocks ratios, which were considerably higher than for any other UGI type. These zones shall be given special attention in the context of C balance. The redesign of open lawns by introducing trees and shrub patches may be recommended. Our findings can be further developed to study the long-term effects of UGI maintenance and soil management on C balance in the format of an Urban Living Lab. This format will allow for the collection of high-resolution and high-frequency data on C stocks and fluxes in urban green infrastructures to support the C-smart management of urban soils as a nature-based solution for climate mitigation and sustainable urban development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soilsystems10020024/s1, Figure S1: Historical (1752) map of the ‘Bovendijkgraafse polders’ with the current campus area (green boundaries) shown as agricultural lands (A). Soil map of Wageningen (1951) where the current campus area (green boundaries) is dominated by ‘wet cover sands’ (B); Figure S2: Modelled SOC stocks (mean and 95% confidence interval) in topsoil of different UGI types (A), age groups (B) and their combinations (C) (H—herbs, L—lawns, S—shrubs, T—trees, O—old, I—intermediate, R—recent).

Author Contributions

V.V., M.R.H. and R.v.V.; methodology, V.V., R.v.V., Y.D. and M.R.H.; validation, Y.D. and M.V.K.; formal analysis, V.V., R.v.V. and Y.D.; investigation, V.V., R.v.V. and Y.D.; resources, V.V. and M.R.H.; data curation, V.V., Y.D. and M.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V.; writing—review and editing, M.R.H., R.v.V. and Y.D.; visualization, V.V. and M.V.K.; supervision, V.V. and M.R.H.; project administration, V.V., M.R.H. and M.V.K.; funding acquisition, Y.D. and M.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Experimental research was carried out as part of the MSc thesis project supported by SGL and SOC groups of Wageningen University. Remote sensing analysis and modelling was supported by Russian Science Foundation project # 19-77-300-12. Processing and interpretation of the results was supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System (Project 202414-2-000).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ariluoma, M.; Ottelin, J.; Hautamäki, R.; Tuhkanen, E.M.; Mänttäri, M. Carbon Sequestration and Storage Potential of Urban Green in Residential Yards: A Case Study from Helsinki. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuzere, M.; Orru, K.; Heidrich, O.; Olazabal, E.; Geneletti, D.; Orru, H.; Bhave, A.G.; Mittal, N.; Feliu, E.; Faehnle, M. Mitigating and Adapting to Climate Change: Multi-Functional and Multi-Scale Assessment of Green Urban Infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jia, X.; Zha, T.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; He, G.; Yu, H.; Chen, G. Soil respiration in a mixed urban forest in China in relation to soil temperature and water content. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2013, 54, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Wang, W.; He, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B. Quantifying tree and soil carbon stocks in a temperate urban forest in northeast China. Forests 2016, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, E.; Goldstein, B.; Aubry, C.; Gabrielle, B.; Horvath, A. Best practices for consistent and reliable life cycle assessments of urban agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E. Carbon storage and sequestration by urban trees in the USA. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; van der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.J.; Kronenberg, J.; de Groot, R. Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchepeleva, A.S.; Vasenev, V.I.; Mazirov, I.M.; Vasenev, I.I.; Prokhorov, I.S.; Gosse, D.D. Changes of soil organic carbon stocks and CO2 emissions at the early stages of urban turf grasses development. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 20, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenev, V.I.; Varentsov, M.I.; Sarzhanov, D.A.; Makhinya, K.I.; Gosse, D.D.; Petrov, D.G.; Dolgikh, A.V. Influence of Meso- and Microclimatic Conditions on the CO2 Emission from Soils of the Urban Green Infrastructure of the Moscow Metropolis. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaranayake, W.; Qian, Y.L.; Parton, W.J.; Ojima, D.S.; Follett, R.F. Estimation of soil organic carbon changes in turfgrass systems using the CENTURY model. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.L.; Bandaranayake, W.; Parton, W.J.; Mecham, B.; Harivandi, M.A.; Mosier, A.R. Long-Term Effects of Clipping and Nitrogen Management in Turfgrass on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics: The CENTURY Model Simulation. J. Environ. Qual. 2003, 32, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B.; Schume, H. Tall tower eddy covariance measurements of CO2 fluxes in Vienna, Austria. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 274, 118941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, S.M.; Hutyra, L.R.; Rao, P.; Finzi, A.C. Inconsistent definitions of “urban” result in different conclusions about the size of urban carbon and nitrogen stocks. Ecol. Appl. 2012, 22, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakarami, L.; Pourmanafi, S.; Soffianian, A.R.; Lotfi, A. Modeling Spatial Distribution of Carbon Sequestration, CO2 Absorption, and O2 Production in an Urban Area: Integrating Ground-Based Data, Remote Sensing Technique, and GWR Model. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, S.; Ananyeva, N.; Ivashchenko, K.; Vasenev, V.; Kudeyarov, V. Soil CO2 emission, microbial biomass, and microbial respiration of woody and grassy areas in Moscow (Russia). J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 3217–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D.; Pizzol, R.; Calza, P.; Malandrino, M.; Gaggero, E.; Padoan, E.; Ajmone-Marsan, F. Constructed technosols: A strategy toward a circular economy. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchenko, K.; Lepore, E.; Vasenev, V.; Ananyeva, N.; Demina, S.; Khabibullina, F.; Vaseneva, I.; Selezneva, A.; Dolgikh, A.; Sushko, S.; et al. Assessing soil-like materials for ecosystem services provided by constructed technosols. Land 2021, 10, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbov, S.N.; Vasenev, V.I.; Minaeva, E.N.; Tagiverdiev, S.S.; Skripnikov, P.N.; Bezuglova, O.S. Short-Term Dynamics of CO2 Emission and Carbon Content in Urban Soil Constructions in the Steppe Zone. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Ryu, Y. Land use and land cover changes explain spatial and temporal variations of the soil organic carbon stocks in a constructed urban park. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, R.; Zhao, D. Effects of land use and cover change on terrestrial carbon stocks in urbanized areas: A study from Changzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirkle, G.; Lal, R.; Augustin, B. Modeling carbon sequestration in home lawns. HortScience 2011, 46, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Yeo, D.; Wilson, B.; Ow, L.F. Application of char products improves urban soil quality. Soil Use Manag. 2012, 28, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selhorst, A.; Lal, R. Net carbon sequestration potential and emissions in home lawn turfgrasses of the United States. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Boot, C.M.; Denef, K.; Paul, E. The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouédraogo, R.A.; Chartin, C.; Kambiré, F.C.; van Wesemael, B.; Delvaux, B.; Milogo, H.; Bielders, C.L. Short and long-term impact of urban gardening on soil organic carbon fractions in Lixisols (Burkina Faso). Geoderma 2020, 362, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Lavallee, J.M. Soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: A synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration. Adv. Agron. 2022, 172, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharova, O.; Matyshak, G.; Udovenko, M.; Semenyuk, O.; Epstein, H.; Bobrik, A. Temporal dynamics, drivers, and components of soil respiration in urban forest ecosystems. Catena 2020, 185, 104299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbov, S.N.; Bezuglova, O.S.; Skripnikov, P.N.; Tishchenko, S. Soluble Organic Matter in Soils of the Rostov Agglomeration. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künnemann, T.; Cannavo, P.; Guérin, V.; Guénon, R. Soil CO2, CH4 and N2O fluxes in open lawns, treed lawns and urban woodlands in Angers, France. Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenev, V.I.; Smagin, A.V.; Ananyeva, N.D.; Ivashchenko, K.V.; Gavrilenko, E.G.; Prokofeva, T.V.; Paltseva, A.; Stoorvogel, J.J.; Gosse, D.D.; Valentini, R. Urban soil’s functions: Monitoring, assessment, and management. In Adaptive Soil Management: From Theory to Practices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Serrani, D.; Ajmone-Marsan, F.; Corti, G.; Cocco, S.; Cardelli, V.; Adamo, P. Heavy metal load and effects on biochemical properties in urban soils of a medium-sized city, Ancona, Italy. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 3425–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.P.; McCulley, R.L.; Burke, I.C. Carbon fluxes, nitrogen cycling, and soil microbial communities in adjacent urban, native and agricultural ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S.J.; Dougherty, B.J.; Smith, A.J.; Navaud, D.; Wylie, L.J.; Arndt, S.K. Soil-atmosphere exchange of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide in urban garden systems: Impact of irrigation, fertiliser and mulch. Urban Ecosyst. 2010, 13, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Segovia, E.; Choong, A.M.F.; Lim, B.K.Y.; Vargas, R. Carbon dioxide dynamics in a residential lawn of a tropical city. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Sensitivity of soil organic carbon stocks and fractions to different land-use changes across Europe. Geoderma 2013, 192, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Meyer, H.; Welp, G.; Amelung, W. Soil respiration and its temperature sensitivity (Q10): Rapid acquisition using mid-infrared spectroscopy. Geoderma 2018, 323, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagin, A.V.; Sadovnikova, N.B.; Vasenev, V.I.; Smagina, M.V. Biodegradation of some organic materials in soils and soil constructions: Experiments, modeling and prevention. Materials 2018, 11, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenev, V.; Varentsov, M.; Konstantinov, P.; Romzaykina, O.; Kanareykina, I.; Dvornikov, Y.; Manukyan, V. Projecting urban heat island effect on the spatial-temporal variation of microbial respiration in urban soils of Moscow megalopolis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y. Sources of CO2 efflux from soil and review of partitioning methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapronov, D.V.; Kuzyakov, Y.V. Separation of root and microbial respiration: Comparison of three methods. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2007, 40, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.-Y.; Lau, S.Y.L.; Midot, F.; Jee, M.S.; Lo, M.L.; Sangok, F.E.; Melling, L. Root exclusion methods for partitioning of soil respiration: Review and methodological considerations. Pedosphere 2023, 33, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzhanov, D.A.; Vasenev, V.I.; Vasenev, I.I.; Sotnikova, Y.L.; Ryzhkov, O.V.; Morin, T. Carbon stocks and CO2 emissions of urban and natural soils in Central Chernozemic region of Russia. Catena 2017, 158, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakumov, E.V.; Pavlova, T.A.; Dinkelaker, N.V.; Lemyakina, A.E. Sanitary evaluation of soil cover of the saint petersburg state university campus. Hyg. Sanit. 2019, 98, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, I.A.; Meshalkina, J.L.; Rappoport, A.V.; Shabarova, T.V. Spatial heterogeneity of some soil properties of the botanical garden of Lomonosov Moscow State University. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Soils of Urban, Industrial, Traffic, Mining and Military Areas; Springer Geography: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova, O.Y.; Matyshak, G.V.; Udovenko, M.M.; Bobrik, A.A.; Semenyuk, O.V. Seasonal and annual variations in soil respiration of the artificial landscapes (Moscow Botanical Garden). In Proceedings of the International Congress on Soils of Urban, Industrial, Traffic, Mining and Military Areas; Springer Geography: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statistieken woonplaats Wageningen. Available online: https://allecijfers.nl/woonplaats/wageningen/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- CBS. Inwoners per Gemeente; CBS: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Willem van Groenigen, J.; Velthof, G.L.; Bolt, F.J.V.D.; Vos, A.; Kuikman, P.J. Seasonal variation in N2O emissions from urine patches: Effects of urine concentration, soil compaction and dung. Plant Soil 2005, 273, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, D.W. A critical review of the conventional SOC to SOM conversion factor. Geoderma 2010, 156, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Paustian, K. Aggregate-associated soil organic matter as an ecosystem property and a measurement tool. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, A4–A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xue, W.; Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. Diurnal and seasonal variations in soil respiration of four plantation forests in an urban park. Forests 2019, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Digital soil mapping: A brief history and some lessons. Geoderma 2016, 264, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, F.; Schillaci, C. Comparison between geostatistical and machine learning models as predictors of topsoil organic carbon with a focus on local uncertainty estimation. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 101, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri Nederland. Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland, Versie 4; Esri Nederland: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Modified Copernicus Sentinel Data 2023. Available online: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/copernicus-data-space-ecosystem/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Duguay-Tetzlaff, A.; Bento, V.; Göttsche, F.; Stöckli, R.; Martins, J.; Trigo, I.; Olesen, F.; Bojanowski, J.; da Camara, C.; Kunz, H. Meteosat Land Surface Temperature Climate Data Record: Achievable Accuracy and Potential Uncertainties. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13139–13156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldridge, A.M.; Hook, S.J.; Grove, C.I.; Rivera, G. The ASTER spectral library version 2.0. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A.; Oltra-Carrió, R.; Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Julien, Y.; Sòria, G.; Franch, B.; Mattar, C. Emissivity mapping over urban areas using a classification-based approach: Application to the Dual-use European Security IR Experiment (DESIREX). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 18, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, N.K.; Hulley, G.C.; Hook, S.J.; Laraby, K.; Cook, M.; Schott, J.R. An Operational Land Surface Temperature Product for Landsat Thermal Data: Methodology and Validation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 5717–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermida, S.L.; Soares, P.; Mantas, V.; Göttsche, F.M.; Trigo, I.F. Google Earth Engine open-source code for land surface temperature estimation from the Landsat series. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbankhani, Z.; Zarrabi, M.M.; Ghorbankhani, M. The significance and benefits of green infrastructure using I-Tree canopy software with a sustainable approach Environment Development and Sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 14893–14913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaidze, L.; Salukvadze, J. Green in the City: Estimating the Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban and Peri-Urban Forests of Tbilisi Municipality, Georgia. Forests 2023, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Haase, D.; Thestorf, K.; Makki, M. Carbon Pools of Berlin, Germany: Organic Carbon in Soils and Aboveground in Trees. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambou, A.; Shaw, R.K.; Huot, H.; Vidal-Beaudet, L.; Hunault, G.; Cannavo, P.; Nold, F.; Schwartz, C. Estimation of soil organic carbon stocks of two cities, New York City and Paris. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasenev, V.I.; Prokof’eva, T.V.; Makarov, O.A. The development of approaches to assess the soil organic carbon pools in megapolises and small settlements. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Biogeochemical C and N cycles in urban soils. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasenev, V.; van Velthuijsen, R.; Hoosbeek, M.R.; Leuchner, M. Can University Campuses Be Urban Living Labs? Case Study of Soil and Tree Functions at Wageningen University Green Area. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 76, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyat, R.V.; Yesilonis, I.D.; Golubiewski, N.E. A comparison of soil organic carbon stocks between residential turf grass and native soil. Urban Ecosyst. 2009, 12, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicese, F.P.; Colangelo, G.; Comolli, R.; Azzini, L.; Lucchetti, S.; Marziliano, P.A.; Sanesi, G. Estimating CO2 balance through the Life Cycle Assessment prism: A case—Study in an urban park. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126869. [Google Scholar]

- Flude, C.; Ficht, A.; Sandoval, F.; Lyons, E. Development of an Urban Turfgrass and Tree Carbon Calculator for Northern Temperate Climates. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortleve, A.J.; Mogollón, J.M.; Heimovaara, T.J.; Gebert, J. Topsoil Carbon Stocks in Urban Greenspaces of The Hague, the Netherlands. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 26, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvinen, E.; Backman, L.; Järvi, L.; Kulmala, L. Soil respiration across a variety of tree-covered urban green spaces in Helsinki, Finland. Soil 2024, 10, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S.J.; Ossola, A.; Threlfall, C.G.; Hahs, A.K.; Williams, N.S.G. Soil Carbon and Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio Change under Tree Canopy, Tall Grass, and Turf Grass Areas of Urban Green Space. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Kotze, D.J.; Setälä, H.M. Evergreen trees stimulate carbon accumulation in urban soils via high root production and slow litter decomposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S.B.; Contosta, A.R. Lawn mowing frequency and its effects on biogenic and anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 182, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contosta, A.R.; Lerman, S.B.; Xiao, J.; Varner, R.K. Biogeochemical and socioeconomic drivers of above- and below-ground carbon stocks in urban residential yards of a small city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, L. Carbon storage and fluxes in existing and newly created urban soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 104, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coull, M.; Butler, B.; Hough, R.; Beesley, L. A geochemical and agronomic evaluation of technosols made from construction and demolition fines mixed with green waste compost. Agronomy 2021, 11, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Huang, R.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Lan, T.; Li, Q.; Deng, O.; Tao, Q.; Zeng, M. Temperature induces soil organic carbon mineralization in urban park green spaces, Chengdu, southwestern China: Effects of planting years and vegetation types. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, G.; Bünemann, E.K.; Oguejiofor, C.U.; Meier, J.; Gort, G.; Comans, R.; Mäder, P.; Brussaard, L.; de Goede, R. Sensitivity of labile carbon fractions to tillage and organic matter management and their potential as comprehensive soil quality indicators across pedoclimatic conditions in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 99, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, F.; He, T.; Wang, S. Responses of labile soil organic carbon and enzyme activity in mineral soils to forest conversion in the subtropics. Ann. For. Sci. 2013, 70, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Crane, J.; Hornberger, G.; Carrico, A. The effects of household management practices on the global warming potential of urban lawns. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decina, S.M.; Hutyra, L.R.; Gately, C.K.; Getson, J.M.; Reinmann, A.B.; Short Gianotti, A.G.; Templer, P.H. Soil respiration contributes substantially to urban carbon fluxes in the greater Boston area. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Luo, Y. Substrate regulation of soil respiration in a tallgrass prairie: Results of a clipping and shading experiment. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2003, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Q.D.; Trappe, J.M.; Braun, R.C.; Patton, A.J. Greenhouse gas fluxes from turfgrass systems: Species, growth rate, clipping management, and environmental effects. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataki, D.E.; Alig, R.J.; Fung, A.S.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Kennedy, C.A.; Mcpherson, E.G.; Nowak, D.J.; Pouyat, R.V.; Romero Lankao, P. Urban ecosystems and the North American carbon cycle. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séré, G.; Schwartz, C.; Ouvrard, S.; Renat, J.C.; Watteau, F.; Villemin, G.; Morel, J.L. Early pedogenic evolution of constructed Technosols. J. Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialle, A.; Giampieri, M. Mapping urbanization as an anthropedogenetic process: A section through the times of urban soils. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brianskaia, I.P.; Vasenev, V.I.; Brykova, R.A.; Markelova, V.N.; Ushakova, N.V.; Gosse, D.D.; Gavrilenko, E.V.; Blagodatskaya, E.V. Analysis of Volume and Properties of Imported Soils for Prediction of Carbon Stocks in Soil Constructions in the Moscow Metropolis. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, F.; Dagois, R.; Derrien, D.; Fiorelli, J.L.; Watteau, F.; Morel, J.L.; Schwartz, C.; Simonnot, M.O.; Séré, G. Storage of carbon in constructed technosols: In situ monitoring over a decade. Geoderma 2019, 337, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.Z.; Chen, F.S.; Hu, X.F.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.M. Urbanization aggravates imbalances in the active C, N and P pools of terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 21, e00831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Sanaullah, M.; Heitkamp, F.; Zelenev, V.; Kumar, A.; Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial decomposition of soil organic matter is mediated by quality and quantity of crop residues: Mechanisms and thresholds. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 53, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenev, V.I.; Castaldi, S.; Vizirskaya, M.M.; Ananyeva, N.D.; Shchepeleva, A.S.; Mazirov, I.M.; Ivashchenko, K.V.; Valentini, R.; Vasenev, I.I. Urban soil respiration and its autotrophic and heterotrophic components compared to adjacent forest and cropland within the moscow megapolis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Landscape Architecture to Support City Sustainable Development; Springer Geography: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Odebiri, O.; Mutanga, O.; Odindi, J.; Naicker, R. Modelling soil organic carbon stock distribution across different land-uses in South Africa: A remote sensing and deep learning approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 188, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.; Suleymanov, R.; Kulagin, A.; Yurkevich, M. Mercury Prediction in Urban Soils by Remote Sensing and Relief Data Using Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.; Malucelli, F.; Scalenghe, R. Multitemporal mapping of peri-urban carbon stocks and soil sealing from satellite data. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, T.C.; Lee, X.; Ermida, S.; Zhan, W. On the land emissivity assumption and Landsat-derived surface urban heat islands: A global analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A. Lawns in cities: From a globalised urban green space phenomenon to sustainable nature-based solutions. Land 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; States, S.L. Urban green spaces and sustainability: Exploring the ecosystem services and disservices of grassy lawns versus floral meadows. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.K.; McPherson, E.G. Carbon storage and flux in urban residential greenspace. J. Environ. Manag. 1995, 45, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ignatieva, M.; Larsson, A.; Zhang, S.; Ni, N. Public perceptions and preferences regarding lawns and their alternatives in China: A case study of Xi’an. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Deng, W.; Ignatieva, M.; Bi, L.; Du, A.; Yang, L. Synergy of urban green space planning and ecosystem services provision: A longitudinal exploration of China’s development. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 127997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, J.; Veerman, C.P. Developing Management Practices in: “Living Labs” That Result in Healthy Soils for the Future, Contributing to Sustainable Development. Land 2022, 11, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dro, C.; Kapfinger, K.; Rakic, R. European Missions: Delivering on Europe’s Strategic Priorities; R&I Paper Series; Policy Brief EU-DG Science and Innovation; Directorate General for Research and Innovation (DG RTD) of the European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]