Role of Pedoagroclimate Settings in Enhancing Sorghum Production in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| No | Data | Type, Scale | Extracted Info | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | National Village Boundary Map | Polygon, 1:10,000 |

| https://tanahair.indonesia.go.id/portal-web/unduh (accessed on 20 February 2025) |

| 2. | Soil map | Polygon, 1: 50,000 |

| https://sdlahan.brmp.pertanian.go.id/informasi-publik/inasoil (accessed on 20 February 2025) |

| 3. | Land cover/use map | Polygon, 1:2,500,000 |

| https://onemap.big.go.id/peta (accessed on 22 February 2025) |

| 4. | National Digital Elevation Model (DEMNAS) | Raster; resolution, 8 m |

| https://tanahair.indonesia.go.id/portal-web/unduh (accessed on 20 February 2025) |

| 5. | Agroclimatic Zone Map | Various scales based on an island |

| [31,32,33,34,35] |

| 6. | Agriculture Climate Resource Map | Polygon, 1:1,000,000 |

| [36] |

3. Results

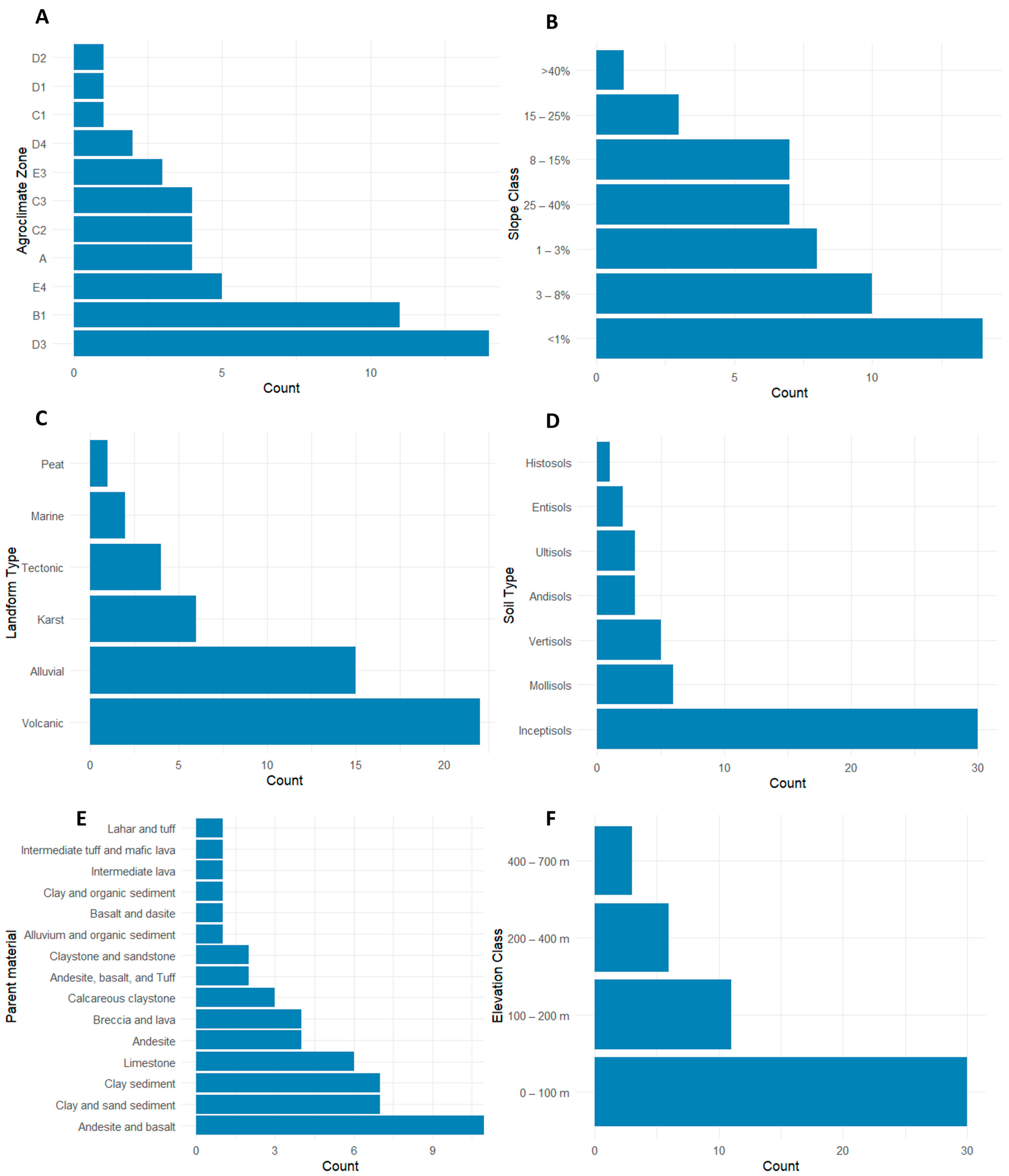

3.1. Pedoagroclimatic Setting

3.2. Cultivated Sorghum Varieties and Yields

3.3. Farmer Cultivation Practices

3.4. Yield Gap and Controlling Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Agroclimate and Planting Season

4.2. Yield Gap and Crop Management

4.3. Soil Management

4.4. Practical and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mundia, C.W.; Secchi, S.; Akamani, K.; Wang, G. A Regional Comparison of Factors Affecting Global Sorghum Production: The Case of North America, Asia and Africa’s Sahel. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althwab, S.; Carr, T.P.; Weller, C.L.; Dweikat, I.M.; Schlegel, V. Advances in Grain Sorghum and Its Co-Products as a Human Health Promoting Dietary System. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Islam, N.; Rahman, M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Khan, A.R. Sorghum: A Prospective Crop for Climatic Vulnerability, Food and Nutritional Security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, J.; Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. Concentration of Pro-Health Compound of Sorghum Grain-Based Foods. Foods 2022, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulamarva, A.G.; Sosle, V.R.; Raghavan, G.S.V. Nutritional and Rheological Properties of Sorghum. Int. J. Food Prop. 2009, 12, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Santhakumar, A.B.; Chinkwo, K.A.; Wu, G.; Johnson, S.K.; Blanchard, C.L. Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Sorghum Grains. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 84, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Warner, R.D.; Fang, Z. Sorghum Grain: From Genotype, Nutrition, and Phenolic Profile to Its Health Benefits and Food Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 2025–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2021; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134332-6. [Google Scholar]

- Suarni. Potensi Sorgum Sebagai Bahan Pangan Fungsional. Iptek Tanam. Pangan 2012, 7, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Istrati, D.I.; Constantin, O.E.; Vizireanu, C.; Dinică, R.; Furdui, B. Sorghum as Source of Functional Compounds and Their Importance in Human Nutrition. Ann. Univ. Dunarea Jos Galati Fascicle VI—Food Technol. 2019, 43, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.; Herald, T.; Cox, S.; Noronha, L.; Perumal, R.; Lee, H.-S.; Smolensky, D. Anticancer Activity of a Novel High Phenolic Sorghum Bran in Human Colon Cancer Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 2890536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontieri, P.; Troisi, J.; Calcagnile, M.; Bean, S.R.; Tilley, M.; Aramouni, F.; Boffa, A.; Pepe, G.; Campiglia, P.; Del Giudice, F.; et al. Chemical Composition, Fatty Acid and Mineral Content of Food-Grade White, Red and Black Sorghum Varieties Grown in the Mediterranean Environment. Foods 2022, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, C.; Suguna, M.; Visarada, K.B.R.S.; Deepika, C.; Ratnavathi, C.V.; Tonapi, V.A. Identification of Sorghum Genotypes Suitable for Specific End Uses: Semolina Recovery and Popping. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 93, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Gafur, N.A.; Sayuti, M.; Rachman, A.B.; Sahara, L.O.; Syahruddin; Tanaka, U. Evaluating Ratooning Sorghum Potential for Goat Feeding in Gorontalo, Indonesia. Millet Res. 2021, 36, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- BPS. Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia, 2010–2035; Badan Pusat Statistik: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bazié, D.; Dibala, C.I.; Kondombo, C.P.; Diao, M.; Konaté, K.; Sama, H.; Kayodé, A.P.P.; Dicko, M.H. Physicochemical and Nutritional Potential of Fifteen Sorghum Cultivars from Burkina Faso. Agriculture 2023, 13, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolozsvári, I.; Kun, Á.; Jancsó, M.; Palágyi, A.; Bozán, C.; Gyuricza, C. Agronomic Performance of Grain Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Cultivars under Intensive Fish Farm Effluent Irrigation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovignan, T.K.; Basha, Y.; Windpassinger, S.; Augustine, S.M.; Snowdon, R.; Vukasovic, S. Precision Phenotyping of Agro-Physiological Responses and Water Use of Sorghum under Different Drought Scenarios. Agronomy 2023, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuistion, K.C.; Selle, P.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Goodband, R.D. Sorghum as a Feed Grain for Animal Production. In Sorghum and Millets; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 355–391. ISBN 978-0-12-811527-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pujiharti, Y.; Paturohman, E.; Ikhwani. Prospect of Sorghum Development as Corn Substitution in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 978, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S.; Vinutha, K.S.; Kumar, G.S.A.; Chiranjeevi, T.; Uma, A.; Lal, P.; Prakasham, R.S.; Singh, H.P.; Rao, R.S.; Chopra, S.; et al. Sorghum: A Multipurpose Bioenergy Crop. In Agronomy Monographs; Ciampitti, I.A., Vara Prasad, P.V., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2019; pp. 399–424. ISBN 978-0-89118-628-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stamenković, O.S.; Siliveru, K.; Veljković, V.B.; Banković-Ilić, I.B.; Tasić, M.B.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Đalović, I.G.; Mitrović, P.M.; Sikora, V.Š.; Prasad, P.V.V. Production of Biofuels from Sorghum. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xie, G.; Li, S.; Ge, L.; He, T. The Productive Potentials of Sweet Sorghum Ethanol in China. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 2360–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiloso, E.I.; Setiawan, A.A.R.; Prasetia, H.; Muryanto; Wiloso, A.R.; Subyakto; Sudiana, I.M.; Lestari, R.; Nugroho, S.; Hermawan, D.; et al. Production of Sorghum Pellets for Electricity Generation in Indonesia: A Life Cycle Assessment. Biofuel Res. J. 2020, 7, 1178–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarti, C.; Arif, A.B.; Budiyanto, A.; Richana, N. Sorghum Development for Staple Food and Industrial Raw Materials in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 443, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, S.; Triastono, J.; Sahara, D.; Pustika, A.B.; Kristamtini; Purwaningsih, H.; Arianti, F.D.; Praptana, R.H.; Romdon, A.S.; Sutardi; et al. Economic Value, Farmers Perception, and Strategic Development of Sorghum in Central Java and Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, S.; Surdianto, Y.; Erythrina, E.; Bhermana, A.; Liana, T.; Syafruddin, S.; Anshori, A.; Nugroho, W.A.; Hidayanto, M.; Widiastuti, D.P.; et al. Strategic, Economic, and Potency Assessment of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) Development in the Tidal Swamplands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, S.W.; Lestari, F.; Adiwibowo, A.; Fisher, M.R. Prediction of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Distribution Ranges Provides Insights on Potential Sorghum Cultivation across Tropical Ecoregions of Indonesia. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System, Version 3.40.3. Available online: https://www.qgis.org (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Marsoedi, D.S.; Widagdo; Dai, J.; Suharta, N.; Darul, S.W.P.; Hardjowigeno, S.; Hof, J.; Jordens, E.R. Guidelines for Landform Classification; Techincal Report, Second LREP; Center for Soil and Agroclimate Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oldeman, L.R. An Agroclimatic Map of Java; Contributions from The Central Research Institute for Agriculture Bogor 17; Center Research Institute for Agriculture: Bogor, Indonesia, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Oldeman, L.R.; Las, I.; Darwis, S.N. An Agroclimatic Map of Sumatera Scale of 1:3.000.000; Contributions from The Central Research Institute for Agriculture Bogor 52; Central Research Institute for Agriculture: Bogor, Indonesia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Oldeman, L.R.; Las, I. Muladi Agro-Climatic Maps of Maluku and Irian Jaya, Bali, Nusa Tenggara Barat and Nusa Tenggara Timur; Contributions from The Central Research Institute for Agriculture Bogor; Center Research Institute for Agriculture: Bogor, Indonesia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Oldeman, L.R.; Darmijati, S. An Agroclimatic Map of Sulawesi, Scale 1:2.500.000; Contributions from The Central Research Institute for Agriculture Bogor 33; Center Research Institute for Agriculture: Bogor, Indonesia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Oldeman, L.R.; Las, I. Muladi Agroclimatic Map of Kalimantan, Scale 1:3.000.000; Contributions from The Central Research Institute for Agriculture Bogor; Center Research Institute for Agriculture: Bogor, Indonesia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Balai Penelitian Agroklimat dan Hidrologi. Atlas Sumberdaya Iklim Pertanian Indoensia Skala 1:1000000; Balai Penelitian Agroklimat dan Hidrologi: Bogor, Indonesia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaeman, Y.; Aryati, V.; Suprihatin, A.; Santari, P.T.; Haryati, Y.; Susilawati, S.; Siagian, D.R.; Karolinoerita, V.; Cahyaningrum, H.; Pramono, J.; et al. Yield Gap Variation in Rice Cultivation in Indonesia. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariningsih, E.; Saliem, H.P.; Nurhasanah, A.; Gunawan, E.; Agustian, A. Saptana Challenges and Alternative Solutions in Developing Sorghum to Support Food Diversification in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1153, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Méndez, J.; Soto-Rocha, J.M.; Hernández-Pérez, M.; Gómez-Tejero, J. Technology for the Production of Sorghum for Grain in the Vertisols of Campeche, Mexico. Agric. Sci. 2021, 12, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, H.; Molla, E.; Feyisa, T. Identification of Yield-Limiting Nutrients for Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Yield, Nutrient Uptake and Use Efficiency on Vertisols of Raya Kobo District, Northeastern Ethiopia. Int. J. Agron. 2023, 2023, 5394806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patroti, P.; Madhusudhana, R.; Sundaram, S.; Prasad, G.S.; Raigond, B.; Das, I.; Satyavathi, C.T. Development of High Yielding and Stress Resilient Post-Rainy Season Sorghum Cultivars Using a Multi-Parent Crossing Approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, C.; Audilakshmi, S.; Ratnavathi, C.; Patil, J. Grain Quality Improvement of Rainy Season Sorghums. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2012, 4, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarik, M.K.; Hussain, K.; Abbas, G.; Altaf, M.T.; Baloch, F.S.; Ahmad, S. Productivity of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolar L.) at Diverse Irrigation Regimes and Sowing Dates in Semi-Arid and Arid Environment. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2022, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ardhani Pithaloka, S.; Kamal, M.; Futas Hidayat, K. Pengaruh Kerapatan Tanaman Terhadap Pertumbuhan Dan Hasil Beberapa Varietas Sorgum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). J. Agrotek Trop. 2015, 3, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairunnisa, L.R.R.; Irmansyah, T. Respon Pertumbuhan Dan Produksi Tanaman Sorgum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Terhadap Pemberian Mulsa Dan Berbagai Metode Olah Tanah. J. Online Agroekoteknol. 2015, 3, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kugedera, A.T.; Kokerai, L.K.; Nyamadzawo, G.; Mandumbu, R. Evaluating Effects of Selected Water Conservation Techniques and Manure on Sorghum Yields and Rainwater Use Efficiency in Dry Region of Zimbabwe. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabasa, H.Z.; Nciizah, A.D.; Muchaonyerwa, P. Short-Term Tillage Management Effects on Grain Sorghum Growth, Yield and Selected Properties of Sandy Soil in a Sub-Tropical Climate, South Africa. Sci. Afr. 2025, 27, e02556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthe, L.S.; Irmansyah, T.; Hanum, C. Respon Pertumbuhan Dan Produksi Tiga Varietas Sorgum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Dengan Perbedaan Sistem Pengolahan Tanah. J. Online Agroekoteknol. 2013, 1, 95840. [Google Scholar]

- Musafiri, C.M.; Kiboi, M.; Macharia, J.; Ng’etich, O.K.; Okoti, M.; Mulianga, B.; Kosgei, D.K.; Ngetich, F.K. Does the Adoption of Minimum Tillage Improve Sorghum Yield among Smallholders in Kenya? A Counterfactual Analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 223, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, D.H.; Irmansyah, T.; Purba, E. Pengaruh Waktu Penyiangan Terhadap Pertumbuhan Dan Produksi Beberapa Varietas Sorgum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). J. Online Agroekoteknol. 2013, 2, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Arvan, R.Y.; Aqil, M. Deskripsi Varietas Unggul Jagung, Sorgum Dan Gandum; Balai Penelitian Tanaman Serealia: Maros, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistyawati, S. Mengenal Genotipe Sorgum Lokal Jawa Timur; CV. Literasi Nusantara Abadi: Malang, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BPSI Tanaman Serealia. Deskripsi Varietas Ungul Baru Jagung Dan Sorgum; Badan Standarisasi Instrumen Pertanian: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukkun, L.; Lalel, H.J.D.; Kleden, Y.L. The Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Several Accessions of Sorghum Cultivated on Drylands in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talanca, A.H.; Andayani, N.N. Development of Sorghum Variety in Indonesia. In Sorghum: Innovation Technology and Development; Sumarno, Damardjati, D.S., Syam, M., Hermanto, Eds.; IAARD Press: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leiser, W.L.; Rattunde, H.F.W.; Piepho, H.; Weltzien, E.; Diallo, A.; Melchinger, A.E.; Parzies, H.K.; Haussmann, B.I.G. Selection Strategy for Sorghum Targeting Phosphorus-limited Environments in West Africa: Analysis of Multi-environment Experiments. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagesh Kumar, M.V.; Ramya, V.; Govindaraj, M.; Sameer Kumar, C.V.; Maheshwaramma, S.; Gokenpally, S.; Prabhakar, M.; Krishna, H.; Sridhar, M.; Venkata Ramana, M.; et al. Harnessing Sorghum Landraces to Breed High-Yielding, Grain Mold-Tolerant Cultivars with High Protein for Drought-Prone Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 659874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, L.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y. Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community. Plants 2025, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Awal, R.; Fares, A.; Veettil, A.V.; Elhassan, A.; Rahman, A. Optimized Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization Enhance Sorghum Yield and Resilience in Drought-Prone Regions. Plants 2025, 14, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiku, F.N.M.; Nyamadzawo, G.; Nyamangara, J.; Mandumdu, R. Effect of Countour Rainwater-harvesting and Integrated Nutrient Management on Sorghum Grain Yield in Semi-arid Farming Environments of Zimbabwe. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B–Soil Plant Sci. 2022, 72, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Enhancing Salt Stress Tolerance and Yield Parameters of Proso Millet Through Exogenous Proline and Glycine Betaine Supplementation. Bangladesh Agron. J. 2023, 26, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.V.N.; Ramya, V.; Maheshwaramma, S.; Ganapathy, K.N.; Govindaraj, M.; Kavitha, K.; Vanisree, K. Exploiting Indian Landraces to Develop Biofortified Grain Sorghum with High Protein and Minerals. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1228422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oria, M.P.; Hamaker, B.R.; Axtell, J.D.; Huang, C.-P. A Highly Digestible Sorghum Mutant Cultivar Exhibits a Unique Folded Structure of Endosperm Protein Bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 5065–5070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Appiah-Nkansah, N.B.; Li, J.; Rooney, W.; Wang, D. A Review of Sweet Sorghum as a Viable Renewable Bioenergy Crop and Its Techno-Economic Analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, A.K.; Yones, H.A.; Karim, N.; Taha, E.M.; Chen, W. Potential Processing Technologies for Developing Sorghum-Based Food Products: An Update and Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Sodhi, N.S.; Dhillon, B.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lin, J.-H. Physicochemical and Structural Characteristics of Sorghum Starch as Affected by Acid-ethanol Hydrolysis. Food Meas. 2021, 15, 2377–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Queiroz, G.C.M.; De Medeiros, J.F.; Da Silva, R.R.; Da Silva Morais, F.M.; De Sousa, L.V.; De Souza, M.V.P.; Da Nóbrega Santos, E.; Ferreira, F.N.; Da Silva, J.M.C.; Clemente, M.I.B.; et al. Growth, Solute Accumulation, and Ion Distribution in Sweet Sorghum under Salt and Drought Stresses in a Brazilian Potiguar Semiarid Area. Agriculture 2023, 13, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, Y.; Cano, F.J.; Pan, L.; Koller, F.; Piñeiro, J.; Jordan, D.; Ghannoum, O. Anatomical Drivers of Stomatal Conductance in Sorghum Lines with Different Leaf Widths Grown under Different Temperatures. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 2142–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Id | Location | Soil Type | Variety | Yield (Mg ha−1) | Coverage (ha) | Planting Season | Main Pest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Mekarjaya Village, Kertajati District, Majalengka Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Bioguma 2 | 4.2 | 5 | Dry season (April) | Rats, Birds |

| 6 | Jelat Village, Baregreg District, Ciamis Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Bioguma 2 | 3.0 | 5 | Wet season (November) | Birds |

| 10 | Jenggala Village, Cidolog District, Ciamis Regency, WJ | Ultisols | Bioguma 2 | 5.0–6.0 | 5 | Wet season (October) | Birds |

| 11 | Cimanggu Village, Langkaplancar District, Pangandaran Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Bioguma 2, Bioguma 3 | 4.0 | 50 | Wet season (November) | Grasshoppers, Birds |

| 12 | Cimerak Village, Cimerak District, Pangandaran Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Numbu, Kawali | 4.0 | 2.5 | Wet Season (December) | Grasshoppers, Birds |

| 16 | Raji Village, Demak District, Demak Regency, CJ | Vertisols | UPCA-S1 | 7.5 | 10 | Dry season (April/June) | Birds |

| 17 | Mojopuro Village, Wuryantoro District, Wonogiri Regency, CJ | Inceptisols | Suri 3 Agritan | 4.0–5.0 | 37 | Dry season (Mei/Juni) | Birds |

| 36 | Sekaroh Village, Jerowaru District, Lombok Timur Regency, WN | Mollisols | Bioguma 1, Soper 9 Agritan, Suri 3 Agritan | 3.0–4.0 | 100 | Wet season (April) | Birds |

| 44 | Jatibaru Village, Asakota District, Bima Regency, WN | Inceptisols | Bioguma 1, Bioguma 2, Bioguma 3, Soper 9 Agritan, Suri 3 Agritan | 3.0–4.0 | 100 | Wet season (November) | Birds |

| 45 | Wareng Village, Wonosari District, Gunung Kidul Regency, YS | Inceptisols | Kawali, Plonco, Hitam Wareng, | 2.5–3.9 | 51 | Dry Season (March) | Birds, Long-Tailed Monkeys, Rats |

| 46 | Bandungrejo Village, Karanganyar District, Demak Regency, CJ | Vertisols | UPCA-S1 | 6.0–7.0 | 5 | Dry season (April/June) | Birds |

| 47 | Rejosari Village, Mijen District, Demak Regency, CJ | Vertisols | UPCA-S1 | 6.0–7.0 | 10 | Dry season (April/June) | Birds, Caterpillars |

| 48 | Wanasaraya Village, Kalimanggis District, Kuningan Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Bioguma 2 | 3.0 | <1 | Wet season (November) | Birds |

| 49 | Margaharja Village, Sukadana District, Ciamis Regency, WJ | Inceptisols | Bioguma 2 | 8.0 | 1 | Dry season (March) | Birds |

| 50 | Banjaranyar Village, Banjaranyar District, Ciamis Regency, WJ | Ultisols | Bioguma 3 | 5.2 | 5 | Wet season (September) | Birds |

| No. | Parameter | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Village | Banjaranyar | Raji | Sambangan | Pamongkong |

| 2. | District | Banjaranyar | Demak | Babat | Jerowaru |

| 3. | Regency | Ciamis | Demak | Lamongan | Lombok Timur |

| 4. | Province | West Java | Central Java | East Java | West Nusa Tenggara |

| 5. | Agroclimate zone | B1 | C2 | D3 | E3 |

| Dry month | <2 | 2 | 5 to 6 | 5 to 6 | |

| Wet month | 7 to 9 | 5 to 6 | 3 to 4 | <3 | |

| Annual rainfall (mm) | >2000 | 1500–2000 | 1000–1500 | <1000 | |

| 6. | Elevation (m asl a) | 200 | 3 | 11 | 14 |

| 7. | Soil type | Inceptisols | Vertisols | Inceptisols | Mollisols |

| 8. | Parent material | Volcanic material | Clay sediment | Claystone | Limestone |

| 9 | Agroecosystem | Dryland | Paddy fields | Paddy fields | Rainfed paddy fields |

| 10. | Crop pattern | Maize–sorghum–fallow | Rice–rice–sorghum, shallot–shallot–sorghum | Rice–rice–sorghum | Rice–sorghum–fallow |

| 11. | Variety | Bioguma 3 | UPCA-S1 | KD 4 | Bioguma 1 |

| 12. | Planting system | Monoculture | Monoculture | Monoculture | Monoculture |

| 13. | Sowing date | September | April/June | April | April |

| 14. | Planting distance | 25 cm × 75 cm | 40 cm × 40 cm or 20 cm × 60 cm | 30 cm × 30 cm × 75 cm | 30 cm × 70 cm |

| 15. | Fertilizer Application (kg ha−1) | At 7 dap b: urea = 50 | At 10 to14 dap: urea = 100 to 250 | At 15 dap: Gandasil D (foliar) | At 14 dap: urea = 50, NPK = 150 |

| At 30 dap: urea = 50 | At 30 to 40 dap: urea = 100 to 250 | At 25 dap: urea = 15, NPK d = 15 | At 25 dap: urea = 15, NPK = 15 | ||

| At 59 dap: urea = 40, NPK = 40 | At 59 dap: urea = 40, NPK = 40 | ||||

| 16. | Harvest month | December | July/September | August | August |

| 17. | Harvest age (dap) | 115 | 95–100 | 90–100 | 125 |

| 18. | Yield (Mg ha−1) | 4.5 to 5.5 | 6.0 to 7.5 | 6.0 to 7.0 | 4.0 to 5.0 |

| 19. | Selling price (per kg dry grain) | IDR. 4000 (USD 0.25) c | IDR 3000–5000 (USD 0.2 to USD 0.3) | IDR 5000 (USD 0.3) | IDR. 4000 (USD 0.25) |

| Soil Type | Agroclimate Zone | Yield (Mg ha−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Average | ||

| Inceptisols | A | 4.0–4.0 | 4.0 |

| B1 | 3.0–8.0 | 5.0 | |

| C2 | 3.0–4.2 | 3.6 | |

| C3 | 3.2–4.5 | 3.9 | |

| D3 | 3.5–6.5 | 5.0 | |

| Mollisols | E3 | 3.5–4.5 | 4.0 |

| Ultisols | A | n.a. * | 5.2 |

| B1 | n.a. | 5.5 | |

| Vertisols | C2 | n.a. | 7.5 |

| D2 | n.a. | 6.5 | |

| D3 | n.a. | 6.5 | |

| Model | Predictor | R2 | Adj-R2 | F-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soil Type | 0.39 | 0.25 | 2.732 | 0.086 |

| 2 | Soil Type + Slope | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.386 | 0.036 * |

| 3 | Soil Type + PM | 0.77 | 0.48 | 2.665 | 0.105 |

| 4 | Soil Type + Landform | 0.91 | 0.87 | 11.500 | 0.003 * |

| 5 | Soil Type + Slope + PM | 0.98 | 0.89 | 10.820 | 0.037 * |

| 6 | Soil Type + Slope + ACZ | 0.85 | 0.22 | 1.341 | 0.456 |

| 7 | Soil Type + Slope + ACZ + Elev | 0.93 | 0.42 | 1.810 | 0.412 |

| Predictor | Coefficient | Standard Error | t Value | Pr(>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 4.50 | 0.58 | 7.73 | 0.000 * |

| Soil Type: | ||||

| 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.518 |

| 1.85 | 0.58 | 3.18 | 0.019 * |

| 2.33 | 0.67 | 3.47 | 0.013 * |

| Landform: | ||||

| −1.00 | 0.82 | −1.22 | 0.269 |

| 2.00 | 0.82 | 2.43 | 0.051 * |

| −0.90 | 0.71 | −1.26 | 0.256 |

| −1.00 | 0.71 | −1.40 | 0.210 |

| −1.50 | 0.82 | −1.82 | 0.118 |

| −0.30 | 0.82 | −0.37 | 0.728 |

| 3.50 | 0.82 | 4.25 | 0.005 * |

| Id | Soil Type | Landform Type | Slope (%) | Agroclimate Subzone | Variety | Yield (Mg ha−1) | Yield Gap | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Farmer | Delta (Mg ha−1) | % | ||||||

| 4 | Inceptisols | VP | 3–8 | C2 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 55 |

| 6 | Inceptisols | OVH | 15–25 | B1 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 68 |

| 11 | Inceptisols | OVH | >40 | B1 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 57 |

| 12 | Inceptisols | KP | 1–3 | A | Nambu | 5.00 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 20 |

| 17 | Inceptisols | AP | 1–3 | C3 | Suri 3 Agritan | 6.00 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 25 |

| 22 | Inceptisols | CL | 1–3 | D3 | KD 4 | 4.00 | 6.5 | −2.5 | |

| 44 | Inceptisols | ACL | 3–8 | D3 | Bioguma 1 | 9.26 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 62 |

| 45 | Inceptisols | KP | 3–8 | C3 | Kawali | 2.96 | 3.2 | −0.2 | |

| 48 | Inceptisols | OVP | 1–3 | C2 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 68 |

| 49 | Inceptisols | VR | 25–40 | B1 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 8.0 | 1.4 | 15 |

| 35 | Mollisols | KP | 3–8 | E3 | Bioguma 1 | 9.26 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 51 |

| 36 | Mollisols | KP | 1–3 | E3 | Suri 3 Agritan | 6.00 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 42 |

| 10 | Ultisols | OVH | 25–40 | B1 | Bioguma 2 | 9.39 | 5.5 | 3.9 | 41 |

| 50 | Ultisols | OVH | 25–40 | A | Bioguma 3 | 8.33 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 38 |

| 16 | Vertisols | AP | 1–3 | C2 | UPCA-S1 | 4.00 | 7.5 | −3.5 | |

| 46 | Vertisols | AP | <1 | D2 | UPCA-S1 | 4.00 | 6.5 | −2.5 | |

| 47 | Vertisols | AP | <1 | D3 | UPCA-S1 | 4.00 | 6.5 | −2.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sulaeman, Y.; Sutrisna, N.; Pramono, J.; Fauziah, L.; Suriadi, A.; Wulanningtyas, H.S.; Maftu’ah, E.; Lestari, E.G.; Mulyani, A. Role of Pedoagroclimate Settings in Enhancing Sorghum Production in Indonesia. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10020023

Sulaeman Y, Sutrisna N, Pramono J, Fauziah L, Suriadi A, Wulanningtyas HS, Maftu’ah E, Lestari EG, Mulyani A. Role of Pedoagroclimate Settings in Enhancing Sorghum Production in Indonesia. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulaeman, Yiyi, Nana Sutrisna, Joko Pramono, Lilia Fauziah, Ahmad Suriadi, Heppy Suci Wulanningtyas, Eni Maftu’ah, Endang Gati Lestari, and Anny Mulyani. 2026. "Role of Pedoagroclimate Settings in Enhancing Sorghum Production in Indonesia" Soil Systems 10, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10020023

APA StyleSulaeman, Y., Sutrisna, N., Pramono, J., Fauziah, L., Suriadi, A., Wulanningtyas, H. S., Maftu’ah, E., Lestari, E. G., & Mulyani, A. (2026). Role of Pedoagroclimate Settings in Enhancing Sorghum Production in Indonesia. Soil Systems, 10(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10020023