Abstract

Accurate prediction of soil texture is essential for effective soil management, precision agriculture, and hydrological modeling. This study proposes a novel, data-driven approach for estimating soil texture without the need for laboratory-based analysis. High-frequency in situ soil moisture measurements from EnviroSCAN (Sentek Technologies, Stepney, Australia) sensors and satellite-derived vegetation indices (NDVI) from Sentinel-2 were collected across 25 sites in Hungary. Temporal soil moisture dynamics were encoded using a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network, designed to capture soil-specific hydrological response behavior from time-series data. The resulting latent embeddings were subsequently used within an ordinal regression framework to predict ordered soil texture classes, explicitly enforcing physical consistency between classes. Model performance was evaluated using leave-one-soil-out cross-validation, achieving an overall classification accuracy of 0.54 and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.50, indicating predominantly adjacent-class errors. The proposed approach demonstrates that soil texture can be inferred from dynamic environmental responses alone, offering a transferable alternative to fraction-based regression models and supporting scalable sensor calibration and digital soil mapping in data-scarce regions.

1. Introduction

Soil texture, defined by the relative proportions of sand, silt, and clay, is a fundamental physical property that governs key soil functions, including water retention, nutrient availability, root penetration, and overall plant productivity [1]. It plays a crucial role in hydrological modeling, irrigation planning, and sustainable agricultural management [2]. Traditionally, soil texture is determined through laboratory-based methods, which are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and costly [3]. Moreover, these methods are not always feasible for large-scale or real-time monitoring, especially in data-scarce or resource-limited regions.

Recent advances in in situ soil data analysis and remote sensing technologies have enabled the development of alternative approaches for non-invasive and scalable estimation of soil properties [4,5]. Soil moisture (SM) dynamics are closely linked to soil texture, as finer-textured soils (e.g., clayey) typically exhibit greater water-holding capacity compared to coarser-textured soils (e.g., sandy) [6]. In addition, vegetation indices such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), derived from satellite platforms like Sentinel-2, can serve as indirect indicators of soil conditions by capturing vegetation responses influenced by moisture and texture [7].

Statistical modeling has become a central pillar of modern soil science, particularly for extracting soil information from indirect and heterogeneous data sources such as satellite observations and in situ sensors. Because many soil properties, including texture, cannot be directly observed at scale, statistical and machine-learning methods play a critical role in linking observable environmental signals to latent soil characteristics through inference rather than direct measurement. Digital Soil Mapping frameworks explicitly rely on statistical learning to integrate soil observations, remote sensing covariates, and environmental predictors in order to produce spatially and temporally consistent soil information [8].

A growing number of studies have demonstrated the potential of machine learning (ML) to support digital soil mapping, particularly in contexts where traditional laboratory analyses are costly or spatially sparse. Ließ et al. (2012) used ML for predicting soil texture in the Ecuadorian Andes and showed that ML models are perform in terms of accuracy and uncertainty reduction [9]. Their study emphasized a critical point that remains highly relevant today: soil texture can be partially inferred from environmental and terrain variables, even when laboratory data are limited.

Complementing this, Chagas et al. (2016) [10] demonstrated that ML outperforms traditional linear regression models for predicting soil surface texture using Landsat TM spectral bands, vegetation indices, and spectral ratios in a semiarid region. Importantly, their study confirmed that remote sensing covariates such as NDVI, clay indices, and shortwave infrared bands carry meaningful information about soil granulometry, further supporting the use of multisource environmental data for soil texture prediction.

This study proposes a hybrid, dynamics-driven machine learning framework for non-invasive soil texture classification. High-frequency soil moisture time series are first encoded using a Long Short-Term Memory neural network, enabling the extraction of soil-specific latent representations that capture temporal wetting–drying behavior and subsurface moisture dynamics. These learned embeddings are then used within an ordinal regression framework, explicitly enforcing the natural ordering of USDA soil texture classes from coarse- to fine-textured soils.

The objectives of this study are threefold:

- (1)

- to develop a dynamic, laboratory-independent soil texture classification model based solely on soil moisture and environmental response patterns,

- (2)

- to encode soil hydrological behavior using LSTM-based temporal representation learning, and

- (3)

- to predict ordered soil texture classes using ordinal regression, ensuring physical consistency and reducing unrealistic misclassification errors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

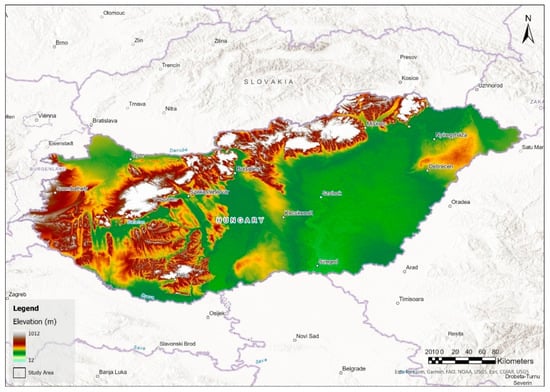

Hungary is located in Central Europe, within the Carpathian Basin, between 45°48′ and 48°35′ N latitude and 16°05′ and 22°58′ E longitude. The country’s topography varies from lowlands to mountainous regions, with its highest peak reaching 1014 m, while the lowest point is at 78 m above sea level. The entire territory falls within the Danube River basin, which significantly influences its hydrological and geomorphological characteristics [11].

The landscape of Hungary is primarily characterized by low elevation and minimal vertical dissection (Figure 1). Approximately 82.4% of the country lies below 200 m, predominantly forming the Great Hungarian Plain (Alföld). In contrast, only 0.5% of the land area exceeds 500 m in elevation, with medium-height mountains (200–500 m) covering 2.1% of the terrain. Additionally, hills and foothills constitute 15.5% of the country’s relief, contributing to the diverse topographical and ecological conditions across the region [12].

Figure 1.

Location and DEM-based topography of the study area (Hungary).

Hungary lies within the northern temperate climatic zone, yet its weather patterns are shaped by the interaction of three major climate influences: oceanic, continental, and Mediterranean systems. The country experiences four distinct seasons, marked by significant temporal variability in temperature and precipitation. Typically, summer is the warmest season and receives the most precipitation, whereas winter is the coldest and driest. However, precipitation patterns are highly variable, both in space and time. Notably, 2010 was the wettest recorded year, featuring an average of 9 days with intense rainfall events exceeding 20 mm [13].

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Sampling Design and Experimental Scheme

Before the actual measurement started on the sampling areas, a critical challenge was addressed of calibrating operational soil moisture sensors without compromising the physical integrity of the monitoring site, this study employed a multi-phased experimental design. The primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy of “off-site” calibration, where reference samples are collected from the immediate vicinity rather than the sensor location itself, against standard laboratory protocols. The experimental framework was executed across three distinct pedological settings in North-eastern Hungary, selected to represent the fundamental soil texture classes: sandy (Görömböly), loam (Tiszavásvari), and clay (University of Miskolc campus).

The calibration procedure was stratified into two methodological phases: First, the field calibration was conducted over a four-month period representing the critical spring vegetation window (March to June 2020). This temporal resolution allowed for the observation of natural soil moisture depletion, ranging from near-saturation in early spring to drier summer conditions. During nine discrete measurement campaigns, a portable EnviroScan sensor array was deployed into permanently installed PVC access tubes. To maintain the “undisturbed” status of the sensor’s sphere of influence, gravimetric reference samples were systematically collected at a radial distance of 1 to 2 m from the access tube. This design was intended to simulate operational constraints where destructive sampling near the probe is prohibited.

Second, the complementary calibration was introduced to address the limited range of naturally occurring soil moisture values observed during the field calibration. To extend the calibration curve toward saturation, artificially induced wetting events were utilized. For the sandy site, owing to its high hydraulic conductivity, this was achieved in situ via the rapid application of 60 L of water, followed by destructive sampling immediately adjacent to the probe. Conversely, due to the slower infiltration rates of the loam and clay textures, these soils were subjected to laboratory calibration. This involved the excavation of bulk soil, air-drying to establish a baseline dry mass, and subsequent stepwise re-wetting and homogenization in controlled containers to achieve a full spectrum of volumetric water contents [14].

The vertical discretization of soil moisture measurements was standardized to align with the sensor architecture and the effective rooting depth of typical spring crops. The EnviroScan capacitance probe system was configured with sensors centered at 10 cm intervals. Accordingly, both the electronic sensor readings and the physical soil sampling were stratified into three depth horizons: 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–30 cm below ground level.

Installation of the access tubes followed a precision protocol designed to minimize air gaps, which are known to introduce significant dielectric error. A tripod rig was utilized to drive the PVC tubes while simultaneously augering soil from within the tube, ensuring a tight interference fit between the tube wall and the undisturbed soil profile. This installation extended to a total depth of 60 cm, sealed with a compression plug to prevent atmospheric coupling.

For the statistical derivation of calibration equations, the study implemented a selective depth analysis. While data was acquired for all three horizons to characterize the vertical moisture profile and identify potential surface boundary effects (0–10 cm) or lower boundary inconsistencies (20–30 cm), the regression analysis primarily utilized the dataset from the 10–20 cm depth. This layer was deemed most representative of the bulk soil matrix, being sufficiently insulated from immediate surface evaporation fluctuations while remaining within the active plow layer. In the laboratory phase, the depth variable was adapted to the container geometry; a uniform 20 cm soil profile was constructed, with the sensor positioned centrally to maximize the volume of influence within the homogenized soil medium [14].

2.2.2. Land-Use of the Sampling Areas

Most of the sampling areas are conducted on agricultural fields. These includes outskirt areas of settlements such as Tiszavasvari, Somodor, Mezokovesd (sample area being called “Matyo”), Tiszaszentimre (sample area being called “Urban”), Tepe and Kunszentmarton. With the exception of Somodor (located in Transdanubia), all these agricultural areas are located on the Great Plains of Hungary. The last remaining sample area, Magyaregregy have a sampling area of forest patches, along a side river inside the Mecsek Mountains, Transdanubia, Hungary where the sensors are located [15].

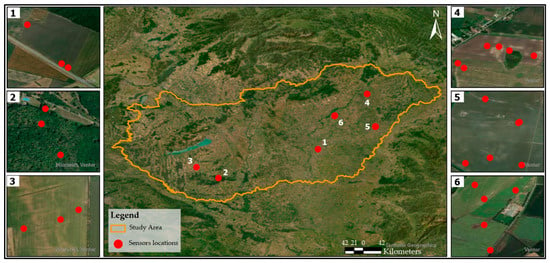

2.2.3. Soil Texture

Soil particle size was measured for soil samples collected from 25 distinct field sites across Hungary, covering a range of geographic and geological conditions. The geographical distribution of these sites is presented in Figure 2, illustrating the spatial variability of soil samples across the study region.

Figure 2.

Sensor’s locations in the study areas.

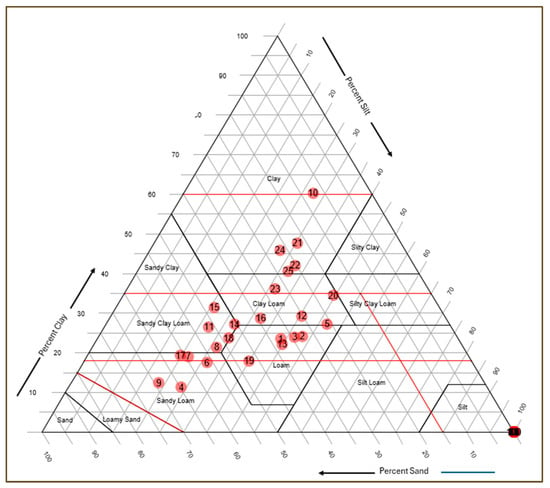

Soil samples were analyzed using standard laboratory procedures to determine the proportions of sand, silt, and clay fractions. These values were subsequently used to classify the soils according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) soil texture classification system, which is widely used for its precision in categorizing soil types based on particle size distribution [16].

The soil particle size and the soil texture classes of our dataset is provided in Table 1, showing how soil texture of this study is classified within the USDA framework.

Table 1.

Soil particle size and soil texture (USDA System).

Figure 3 shows the USDA soil texture triangle with the distribution of 25 analyzed samples. The samples span a wide range of textural classes, including sandy loam, loam, clay loam, sandy clay loam, and clay. Most samples cluster within the loam to clay loam classes, while a few occupy sandy loam and sandy clay loam categories. This distribution reflects the heterogeneity of soil particle size composition across the study sites.

Figure 3.

Soil Texture Distribution of Soil Samples Plotted on the USDA Soil Texture Triangle. The red lines indicate reference thresholds of constant clay, sand, or silt content, used to highlight key transitions in soil texture space and to support the interpretation of texture gradients and class boundaries.

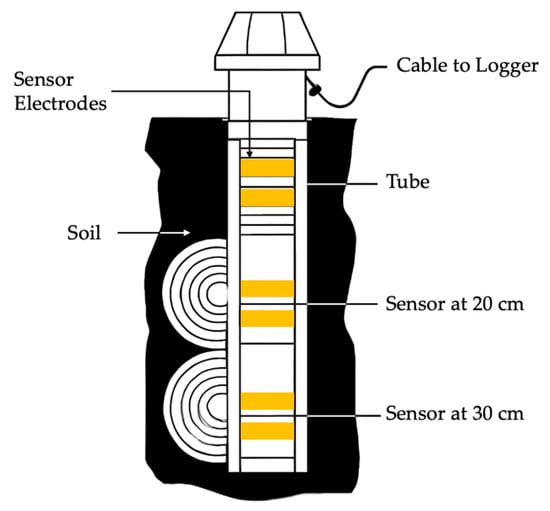

2.2.4. Sentek EnviroScan Sensor

The Sentek EnviroScan sensor consists of multiple capacitance-based sensors installed at 10 cm intervals (Figure 4) along an extruded plastic framework [17,18]. The probe had sensors at six depths, namely 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 100 cm. Each sensor comprises two brass rings forming a capacitor, connected to an LC oscillator, where frequency variations correspond to changes in soil capacitance [18]. The sensor generates an oscillating capacitance field, extending beyond the PVC access pipe into the surrounding soil, allowing measurement of soil moisture content based on frequency shifts. A data logger records output counts, which are scaled between air (dry) and water (saturated) reference readings to determine soil moisture [19,20].

Figure 4.

Sentek EnviroSCAN Sensor for Profiling Water Content Along an Access Tube.

Capacitance probes are valued for their robustness, accuracy, and fast response times [21]. However, their performance is highly dependent on good contact between the access tube and the surrounding soil, as poor contact reduces sensitivity [22,23,24].

At each site of twenty-five distinct field sites across Hungary, one Sentek EnviroScan sensor access pipe was installed.

2.2.5. Remote Sensing Data

Vegetation cover exhibits a negative relationship with soil moisture, as plant canopies intercept precipitation, reducing direct soil infiltration, while transpiration and root water uptake further deplete soil water reserves [25]. Given this interaction, vegetation dynamics play a crucial role in soil moisture variability, making the assessment of vegetation conditions essential for understanding soil water distribution. On the other hand, better water supply results in better plant condition, reflecting the differences in the water supplying capacity of the soils.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index serves as a key indicator for analyzing vegetation conditions and their impact on soil moisture [26]. It is computed using the formula:

where NIR represents the reflectance in the near-infrared band (Sentinel-2 Band 8) and R represents the reflectance in the red band (Sentinel-2 Band 4).

2.2.6. Data Description

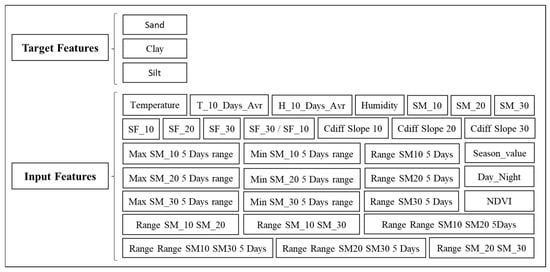

Figure 5 presents the set of input variables used in the machine learning framework together with the target feature, soil texture.

Figure 5.

Input Features and Target Variable for Soil Texture Prediction.

Target Variables

The target variables in this study are the soil particle size classes, as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). It is essential to distinguish between soil particle size and soil texture. While soil texture refers to the relative proportion of sand, silt, and clay particles and determines many physical behaviors of the soil (e.g., water retention, aeration, tillage suitability), particle size classes refer strictly to the classification of mineral particles based on their diameters, independent of their relative abundance or combined behavior [16].

According to USDA classification [16] mineral particles are grouped into three major particle size classes:

Sand: Particles with diameters between 0.05 mm and 2.00 mm. Sand particles are large and result in soils with high permeability, rapid drainage, and low water- and nutrient-holding capacities. Sandy soils are generally well-aerated but are more prone to erosion and leaching [27].

Silt: Particles ranging from 0.002 mm to 0.05 mm. Silt imparts a smooth, floury texture to soil and contributes to improved water-holding capacity and fertility. Silty soils retain moisture better than sandy soils and provide moderate permeability, although they are susceptible to surface crusting and compaction [16].

Clay: Particles less than 0.002 mm in diameter. Clay has the highest surface area and strong electrochemical activity. Soils dominated by clay are highly retentive of water and nutrients but have low infiltration rates and are often subject to swelling, shrinking, and structural limitations [16,27].

Input Features

The input features of the model are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Input features used in the model.

CDiff Slope: The CDiff Slope represents the rate of change in the soil moisture, calculated using the central difference method. This metric quantifies how the slope varies between consecutive depth measurements, providing insights into gradients in soil properties, moisture dynamics, or other related environmental factors at this depth.

Mathematically, CDiff Slope is computed as:

where

- SL: Slope,

- SL_i+1 is the next SL value,

- SL_i−1 is the previous SL value,

- Denominator 2 ensures a centered approximation of the slope.

A higher CDiff Slope indicates steeper changes in SL values, suggesting rapid variations in soil conditions, while a lower slope suggests a more stable and uniform SL distribution.

2.2.7. Model Performance Evaluation

In machine learning, model evaluation is a crucial step to ensure the predictive reliability and generalizability of the model. In this study, model performance was evaluated using a soil-level validation strategy, ensuring that predictions reflect true generalization to unseen soils rather than temporal autocorrelation within the same site.

To this end, Leave-One-Soil-Out cross-validation was employed as the primary evaluation protocol. In each fold, all temporal observations associated with one soil profile were excluded from training and used exclusively for testing, while the model was trained on the remaining soils. This strategy provides a stringent and realistic assessment of model transferability across different soil types and site conditions.

Because the final prediction task is ordinal classification of soil texture classes, standard regression metrics are not appropriate. Instead, evaluation focused on classification and ordinal-consistency metrics that reflect both predictive accuracy and the ordered structure of the target variable. The following performance indicators were used:

Overall Accuracy: the proportion of correctly predicted soil texture classes [29].

Confusion Matrix: used to analyze class-specific performance and error distribution.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): a key metric for ordinal models, measuring the average absolute distance between predicted and true class labels. Lower MAE values indicate that prediction errors are predominantly between adjacent texture classes rather than physically implausible jumps.

The MAE is defined as:

where and represent the predicted and observed ordinal texture class labels, respectively.

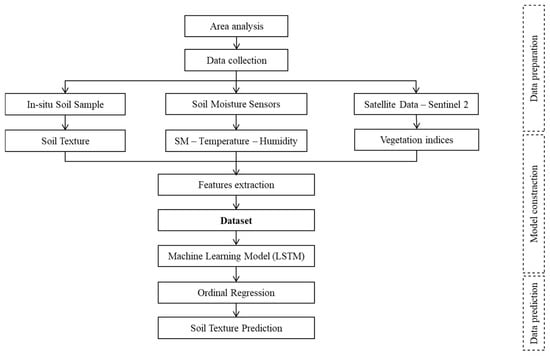

2.3. Methods

The methodological framework of this study, illustrated in Figure 6, is organized into three main phases: data preparation, model construction, and data prediction. In the data preparation phase, high-frequency in situ soil moisture measurements and satellite-derived vegetation indices were collected, preprocessed, and temporally harmonized to construct soil-specific time series. In the model construction phase, temporal soil moisture dynamics were encoded using a Long Short-Term Memory neural network trained as an autoencoder to extract latent representations capturing soil hydrological response behavior. These learned embeddings were then used as inputs to an ordinal regression model designed to predict ordered soil texture classes while enforcing physical consistency between classes. Model performance was evaluated using a leave-one-soil-out cross-validation strategy to ensure robust generalization to unseen soils.

Figure 6.

Soil texture prediction workflow.

2.3.1. Retrieval of SF from the Measured Soil Moisture

In soil moisture monitoring using Sentek’s EnviroSCAN, the Scaled Frequency serves as a normalized indicator of soil moisture content derived from sensor response characteristics. However, in cases where only the Volumetric Soil Water Content is available, it is necessary to retrieve the corresponding SF values through an inverse application of the default calibration equation.

The EnviroSCAN soil moisture sensors use a standard default calibration equation to derive the Scaled Frequency from the Volumetric Soil Water Content. The default calibration equation provided by Sentek for sands, loams, and clay loams follows the form:

where

- SF = Scaled Frequency

- SM = Volumetric Soil Water Content (mm)

- A = 0.19570, B = 0.40400, C = 0.02852 (default calibration coefficients [30])

Given that SF is typically obtained from sensor field measurements, the inverse approach applies when SF values must be retrieved solely from available SM data.

2.3.2. Dataset and Leakage Control

After quality control and sequence-length filtering, 24 soil sites were retained for modeling. For each retained site, high-frequency measurements were resampled to a uniform 2 h timestep (Δt = 2 h) and segmented into fixed-length sequences S24, 24 steps is equal to 48 h, to form the inputs for representation learning and subsequent ordinal prediction.

Soil moisture was modeled jointly at 10, 20, and 30 cm, allowing the LSTM autoencoder to encode both temporal dynamics and vertical redistribution processes. Missing values were handled conservatively: short gaps on the resampled grid were filled using time-based interpolation, while sequences exceeding a predefined gap tolerance were excluded to avoid introducing artificial dynamics. Missingness was quantified per site as the fraction of missing 2 h timestamps relative to the expected time grid.

Satellite-derived NDVI was extracted at each site and temporally matched to the in situ 2 h axis using cloud-masked acquisitions. NDVI values were aligned to soil-moisture windows using the nearest valid acquisition within a defined tolerance, and interpolation was applied only when two cloud-free observations bracketed the target date.

To prevent information leakage, all inputs were constructed using causal windowing: each S24 sequence uses only observations within its 48 h window. Exogenous variables were aligned without using future timestamps, by selecting the most recent valid value at or before the window endpoint. Generalization was assessed using LOSO validation, ensuring complete site-level separation between training and testing.

2.3.3. Remote Sensing Image Selection and Processing

Sentinel 2 Data: Spatial and Temporal Characteristics

In this study, Sentinel-2 satellite imagery was chosen for its high spatial, spectral, and temporal resolution, making it an ideal tool for assessing vegetation dynamics, and environmental conditions. Managed by the European Space Agency (ESA) under the Copernicus Program, Sentinel-2 provides multispectral imagery with spectral bands optimized for vegetation monitoring, soil moisture estimation, and land cover classification.

A key strength of Sentinel-2 is its multi-scale spatial resolution, with 10 m resolution in the Visible (Red, Green, Blue) and Near-Infrared (NIR) bands, allowing for detailed analysis of vegetation and soil moisture. Its 5-day revisit time, enabled by the dual satellite system, ensures frequent acquisitions, facilitating the monitoring of seasonal changes in vegetation health, soil moisture, and land surface dynamics. This temporal resolution is critical for tracking soil-vegetation-atmosphere interactions and detecting short-term variations in environmental processes.

Preprocessing of Sentinel-2 Data

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the remote sensing analysis, Sentinel-2 images undergo multiple preprocessing steps to correct for atmospheric, radiometric, and geometric distortions. These corrections improve the comparability of images over time, reducing errors caused by sensor inconsistencies or atmospheric interference [31].

2.3.4. Predictive Modeling

The predictive modeling framework adopted in this study follows a LSTM deep learning and ordinal classification approach designed to infer soil texture classes from dynamic environmental responses rather than static soil fractions.

The input dataset consists of high-frequency in situ soil moisture time series measured at multiple depths, complemented by satellite-derived vegetation indices and auxiliary environmental variables. All-time series were quality-controlled, temporally aligned, and normalized to ensure consistency across sites. Each soil site was treated as an independent entity characterized by its temporal hydrological response.

To capture the nonlinear and time-dependent soil–water–vegetation interactions, a Long Short-Term Memory autoencoder was employed. The autoencoder was trained in an unsupervised manner to compress multivariate soil moisture dynamics into a low-dimensional latent space. These latent embeddings summarize soil-specific response behavior, including infiltration, drainage, and moisture persistence, without requiring prior knowledge of soil texture labels.

The learned latent embeddings were subsequently used as inputs to an ordinal regression model to predict soil texture classes. Unlike conventional multiclass classification, ordinal regression explicitly accounts for the natural ordering of soil texture categories (sandy, loam, clay), enforcing physical consistency in predictions. This formulation penalizes distant misclassifications more strongly than adjacent ones, aligning model behavior with soil physical principles.

Model performance was assessed using leave-one-soil-out cross-validation to ensure generalization across independent soil sites. Evaluation metrics included classification accuracy and the Mean Absolute Error, which quantifies the average distance between predicted and true texture classes along the ordinal scale

All modeling steps were implemented in Python 3.11.5, using deep learning libraries for LSTM training and scikit-learn–compatible implementations for ordinal regression and evaluation.

2.3.5. LSTM–Ordinal Model Application

Long Short-Term Memory is a recurrent neural network architecture that introduces memory cells and gated mechanisms to regulate information flow over time, enabling the model to retain or discard past information and learn long-range temporal dependencies more effectively than standard neural networks [32].

The proposed model integrates unsupervised temporal feature learning with physically constrained ordinal prediction, enabling soil texture inference directly from environmental response dynamics.

The LSTM autoencoder serves as a representation-learning component, compressing raw high-dimensional time series into compact latent embeddings that summarize temporal dynamics [33]. These embeddings are subsequently mapped to ordered soil texture classes using ordinal regression, ensuring that predictions respect the inherent continuum of soil texture rather than treating classes as independent categories.

This architecture offers several advantages over fraction-based regression and tree-based classifiers: it reduces reliance on handcrafted features, it is well suited for small, soil-level datasets, it enforces physically meaningful class ordering, and it produces predominantly adjacent-class errors, which are more acceptable from a pedological perspective.

The proposed framework is a two-stage hybrid model that separates temporal representation learning from texture-class prediction. In the first stage, a sequence-to-sequence LSTM autoencoder ingests multivariate, multi-depth soil-moisture dynamics (10, 20, and 30 cm) resampled every 2 h and segmented into fixed windows (S24 = 48 h). The encoder consists of stacked LSTM layers that progressively transform the input sequence into a compact latent state vector (32-dimensional embedding, emb0–emb31), designed to summarize each soil’s characteristic wetting–drying behavior without using texture labels. A decoder LSTM then reconstructs the original sequence from this latent vector, and training minimizes reconstruction loss (MSE) with Adam, mini-batches, and early stopping to control overfitting; importantly, normalization and any temporal alignment are learned within training folds only under LOSO to avoid leakage. In the second stage, the learned embeddings (one embedding per sequence, aggregated per soil as required) are passed to an ordinal regression head that predicts ordered texture classes through learned thresholds on a continuous latent score, which explicitly enforces the natural texture ordering and encourages errors to remain adjacent class rather than physically implausible jumps.

3. Results

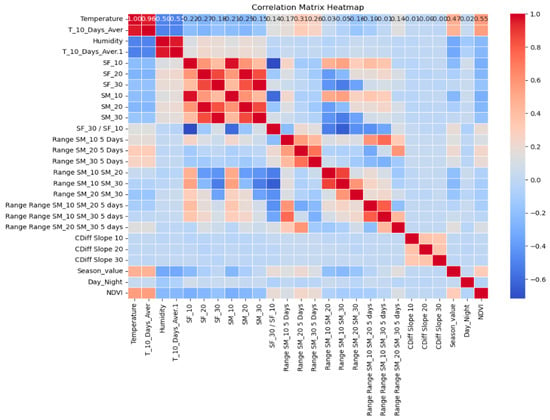

3.1. Variable Influence

The Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to evaluate the linear relationships among the predictor variables, with values ranging between −1 and 1. The correlation matrix, visualized in Figure 7, highlights the degree of association between different environmental and geospatial factors. The heatmap reveals strong positive correlations among temperature-related variables, such as Temperature and T_10_Days_Aver, with a correlation coefficient close to 0.96, indicating a strong linear dependence. Similarly, soil moisture measurements at different depths (SM_10, SM_20, and SM_30) exhibit high correlations, suggesting consistent moisture distribution patterns across layers.

Figure 7.

Correlation coefficient heatmap of the variables.

Conversely, certain variables demonstrate negative correlations, such as soil moisture variability and sand content, reinforcing the expected inverse relationship between sand fraction and water retention capacity. Additionally, NDVI exhibits a moderate positive correlation (0.55) with soil moisture, indicating a potential relationship between vegetation cover and soil water availability. The heatmap also highlights the interdependence between multiple predictor variables, emphasizing the need for multi-variable analysis to accurately capture soil property variations. The observed correlation structure confirms that soil composition and environmental conditions are influenced by complex interactions among multiple factors, validating the selection of predictor variables for robust modeling.

3.2. Soil Texture Prediction Using LSTM-Derived Temporal Embeddings: Performance and Interpretability Analysis

3.2.1. Model Performance Analysis

Soil texture prediction performance was evaluated using the proposed LSTM–ordinal regression framework, which infers ordered soil texture classes (Sandy, Loam, Clay) directly from dynamic environmental responses. In contrast to fraction-based regression approaches, this framework does not predict sand, silt, or clay percentages, but rather assigns soils to physically ordered texture classes.

Model performance was assessed using a LOSO cross-validation strategy to evaluate generalization to unseen soil sites. Class-wise precision, recall, and F1-scores, along with overall accuracy, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

LOSO performance of the LSTM–Ordinal model using S24 embeddings.

The model achieved an overall LOSO accuracy of 0.54, indicating a moderate but meaningful capacity to generalize soil texture predictions across independent soil profiles and a mean absolute error of 0.5. Given the limited number of soil sites and the exclusive reliance on dynamic soil–environment interactions, this result demonstrates that soil texture information is encoded within temporal moisture response patterns.

The results show that loamy soil was predicted most reliably, with a recall of 0.75 and an F1-score of 0.64. This performance reflects the intermediate hydraulic behavior of loamy soils, which exhibit more stable and characteristic moisture dynamics than coarse or fine extremes. Sandy soils achieved moderate precision (0.60) but lower recall (0.43), likely due to their rapid drainage and higher temporal variability, which can obscure consistent hydrological signatures. Clay soils presented the greatest prediction uncertainty, with a recall of 0.20, consistent with their complex shrink–swell behavior, strong hysteresis, and nonlinear moisture retention processes.

Importantly, error analysis revealed that misclassifications were predominantly limited to adjacent texture classes, a desirable outcome in soil classification. This behavior is enforced by the ordinal regression formulation, which explicitly respects the natural ordering of soil texture classes and penalizes distant errors more strongly than neighboring ones. From a pedological perspective, confusion between adjacent classes is substantially less critical than distant misclassification.

Overall, these results confirm that the proposed LSTM–ordinal framework provides a physically consistent and transferable solution for soil texture classification, enabling texture inference from dynamic environmental responses alone. While performance is constrained by dataset size and soil heterogeneity, the dominance of adjacent-class errors and balanced class-wise behavior highlight the practical relevance of the approach for sensor-based soil characterization and digital soil mapping applications.

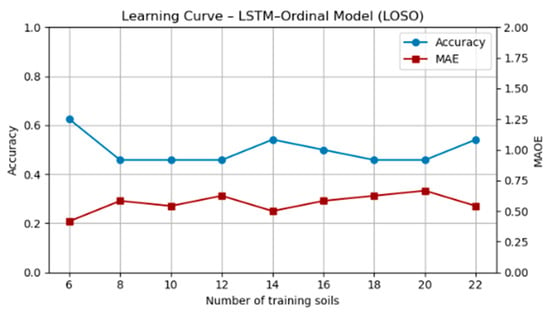

3.2.2. Model Learning Curve Analysis

The learning curve of the LSTM–ordinal model under leave-one-soil-out validation (Figure 8) indicates stable generalization performance across increasing numbers of training soils. Classification accuracy converges around 0.50–0.55, while the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) remains consistently low (<0.5), indicating that most misclassifications occur between adjacent texture classes. This behavior reflects both data-limited performance and strong physical consistency, confirming the suitability of the ordinal formulation for small soil datasets.

Figure 8.

Learning curve of the LSTM–ordinal soil texture model under LOSO validation.

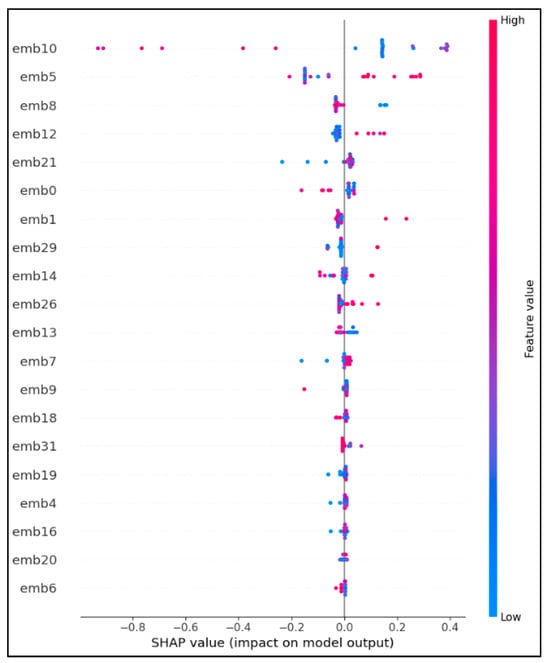

3.2.3. SHAP Plot for LSTM-Derived Embeddings

Figure 9 presents the SHAP summary plot illustrating the relative contribution of the LSTM-derived latent embeddings (emb0–emb31) to the ordinal soil texture prediction. Each point represents the impact of a given embedding value on the predicted soil texture index, with color indicating the magnitude of the embedding activation (low to high). Positive SHAP values shift predictions toward finer textures (clay), while negative values favor coarser textures (sandy), consistent with the ordinal encoding adopted in this study.

Figure 9.

SHAP summary plot of LSTM latent embeddings for ordinal soil texture prediction.

The results indicate that a limited subset of latent dimensions dominates the prediction, notably emb10, emb5, emb8, and emb12, while the remaining embeddings contribute marginally. This concentration of importance suggests that the LSTM autoencoder successfully compressed the high-dimensional soil moisture time series into a compact set of functionally meaningful temporal descriptors, rather than distributing information uniformly across the latent space.

Among these, emb10 emerges as the most influential latent dimension, exhibiting the largest absolute SHAP values and a clear directional effect. High values of emb10 are associated with positive SHAP contributions, shifting predictions toward finer-textured classes, whereas low values consistently push predictions toward coarser textures. From a soil physics perspective, this behavior is consistent with short-term soil moisture persistence and reduced drainage rates, which are characteristic of finer-textured soils with higher water-holding capacity. Conversely, negative contributions likely reflect rapid wetting–drying cycles, typically observed in sandy soils with high permeability and low retention.

Similarly, emb5 and emb8 show strong but complementary effects, with patterns suggesting sensitivity to intermediate temporal dynamics, such as delayed drainage or moderate moisture variability. These behaviors are consistent with loamy soils, which occupy a transitional hydraulic regime between coarse and fine textures. The broader spread of SHAP values for these embeddings indicates that they capture variability across soil classes rather than class-specific extremes.

Lower-ranked embeddings (e.g., emb26, emb13, emb7) exhibit near-zero SHAP contributions, indicating limited influence on the final prediction. This suggests that these latent dimensions encode secondary or redundant temporal patterns that are not critical for texture discrimination under the studied conditions. Importantly, this behavior reflects effective representation learning rather than model overfitting, as irrelevant latent features are naturally down-weighted by the ordinal regressor.

It is important to emphasize that individual embeddings do not correspond to explicit physical variables such as infiltration rate or evapotranspiration. Instead, they represent composite temporal signatures arising from the interaction of soil hydraulic properties, atmospheric demand, and vegetation influence.

Overall, this analysis demonstrates that the proposed LSTM–ordinal framework does not rely on static soil fractions but instead infers soil texture through dynamic soil–water response patterns. The dominance of a small number of latent dimensions further enhances model interpretability and robustness, reinforcing the suitability of this approach for soil texture inference in data-scarce and sensor-based monitoring contexts.

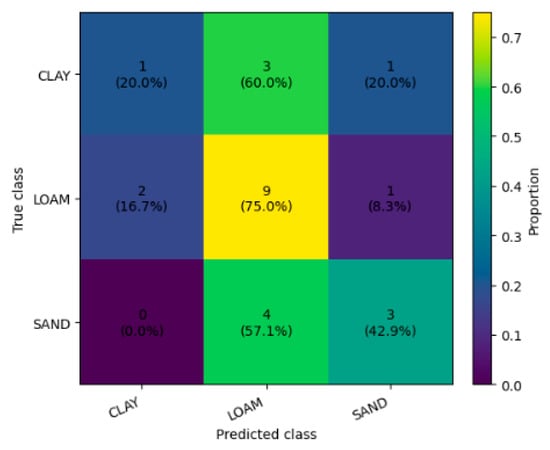

3.2.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis

Figure 10 summarizes the leave-one-soil-out confusion matrix for the LSTM–ordinal texture classifier, reporting row-normalized proportions together with absolute counts. Overall, the model shows a clear tendency to concentrate predictions toward the intermediate Loamy class, which is consistent with both the class distribution and the transitional hydraulic behavior of loamy soils.

Figure 10.

Confusion Matrix of Soil Texture Class Predictions.

For Loam, the model achieves the strongest class recognition, correctly classifying 9 out of 12 soils (75.0%), with limited confusion toward Clay (16.7%) and Sandy (8.3%). This result indicates that the learned temporal embeddings capture moisture dynamics typical of intermediate textures, where infiltration and drainage processes are neither extremely fast as in sands nor strongly buffered as in clays.

Performance is weaker for Clay. Only 1 out of 5 Clay soils (20.0%) is correctly classified, while most Clay samples are misclassified as Loam (60.0%), and one case shifts to Sandy (20.0%). This reflects the challenge of distinguishing clay-rich hydraulic signatures under limited soil-level sample size and potentially overlapping environmental forcing that can make clay responses appear “loam-like” over the chosen temporal window.

For Sandy soil, 3 out of 7 soils (42.9%) are correctly classified, whereas 4 soils (57.1%) are predicted as Loam. Importantly, no Sandy soil is misclassified as Clay (0.0%), suggesting that the ordinal formulation and the latent embeddings jointly reduce physically implausible long-range errors. Overall, most mistakes occur between adjacent texture classes, which is desirable from a pedological perspective because texture transitions are continuous and boundary classes often share similar short-term moisture patterns.

The matrix indicates that the proposed LSTM–ordinal framework provides physically consistent predictions but remains limited by (i) the small number of soils per class (especially Clay), and (ii) potential class overlap in hydrological response under similar climate/management conditions. Increasing the number of clay and sandy sites, extending the temporal window to capture slower clay processes, and adding complementary forcing variables such as rainfall and ET0 are expected to improve separability of the extreme classes while preserving the ordinal-consistent error structure.

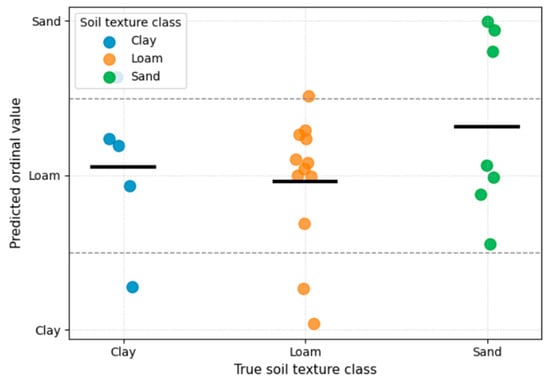

3.2.5. Evaluation of Model Predictions: True vs. Predicted Soil Composition

The scatter plot (Figure 11) illustrates the relationship between observed and predicted soil texture classes produced by the LSTM–ordinal model under leave-one-soil-out validation. Each point represents an individual soil site, with the vertical position indicating the continuous ordinal prediction and the horizontal position denoting the true texture class. Horizontal black bars indicate the median predicted ordinal value for each class.

Figure 11.

True vs. Predicted Soil Texture Classes Using the LSTM–Ordinal Model.

For clay soils, predictions are concentrated around the clay–loam boundary, with most values remaining close to the true class and only limited upward shifts toward loam. This pattern reflects the model’s tendency to avoid physically implausible long-range misclassifications, instead producing predominantly adjacent-class errors.

Loam soils show the tightest clustering around the central ordinal value, indicating high model confidence and stability for intermediate textures. The narrow dispersion and median alignment close to the true class confirm that loam soils are the most consistently recognized by the model, likely due to their balanced moisture dynamics and intermediate hydraulic behavior.

For sandy soils, predictions are generally shifted upward relative to clay and loam, with most values concentrated near the sandy–loam boundary. Some downward deviations toward loam are observed, reflecting overlap in short-term moisture response between sandy loams and coarser loams. Importantly, no extreme misclassifications toward clay are present.

Overall, the plot demonstrates that the LSTM–ordinal framework preserves the ordered structure of soil texture classes, with errors constrained to adjacent categories. This behavior is physically meaningful, as soil texture transitions are continuous rather than discrete. The absence of long-range errors confirms the model’s physical consistency and supports its suitability for non-invasive soil texture inference based solely on dynamic environmental response patterns.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that soil texture information can be inferred from dynamic soil–environment interactions, without direct reliance on laboratory-derived particle-size fractions. By combining high-frequency soil moisture observations, satellite-derived vegetation indices, and deep temporal representation learning, the proposed LSTM–ordinal framework provides a physically consistent and non-invasive alternative for soil texture classification.

The achieved overall accuracy of 0.54 under LOSO validation reflects a moderate but meaningful predictive capability, particularly given the stringent validation protocol and the limited number of soil sites. Unlike conventional cross-validation schemes that mix observations from the same soil profile, LOSO evaluation enforces true spatial generalization [34], ensuring that predictions are based on transferable soil parameters behavior rather than site-specific temporal patterns.

The results indicate that loamy soils are predicted most reliably, followed by sandy soils, while clay soils present the greatest challenge. This hierarchy is consistent with soil physical behavior. Loamy soils occupy an intermediate hydraulic regime, exhibiting balanced infiltration, drainage, and moisture persistence, which leads to more stable and distinctive temporal signatures [35]. In contrast, sandy soils are characterized by rapid wetting–drying cycles and high permeability, resulting in greater temporal variability [36], while clay soils exhibit nonlinear moisture retention and shrink–swell behavior that complicate pattern extraction.

The SHAP analysis revealed that a small subset of latent embeddings dominates the prediction, indicating effective dimensionality reduction by the LSTM autoencoder. Rather than distributing information evenly across all latent dimensions, the network concentrates soil-relevant dynamics into a few informative components.

Despite its promising results, this study has several limitations that warrant careful consideration. First, the dataset comprises 25 soil sites, which constrains the statistical power of deep learning models and limits representation of rare or extreme soil conditions. Although the use of unsupervised representation learning and LOSO validation mitigates overfitting, larger and more diverse datasets would likely improve class separability, particularly for clay-rich soils. Second, the temporal window length (S24) captures short- to medium-term hydrological dynamics but may not fully represent long-term seasonal processes, such as cumulative wetting history, deep percolation, or structural changes. Extending the framework to multi-scale temporal windows could further enhance representation of slow soil processes. Third, the current model focuses exclusively on hydrological and vegetation-driven signals. While this is a deliberate design choice to ensure non-invasiveness, incorporating auxiliary information such as terrain attributes, soil organic matter proxies, or climate normals may improve discrimination between structurally similar textures. Finally, while SHAP analysis improves interpretability [37], latent embedding remains abstract representations, and direct physical attribution should be made cautiously. Future work could explore hybrid approaches combining learned embeddings with physically interpretable hydrological indicators.

Despite these limitations, the proposed framework represents a significant step toward dynamic, sensor-based soil texture mapping. Its ability to infer texture from environmental response patterns alone opens new possibilities for sensor calibration, digital soil mapping, and precision agriculture in regions where laboratory soil surveys are limited.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a novel, non-invasive framework for soil texture classification based exclusively on dynamic soil–environment interactions, integrating high-frequency in situ soil moisture observations, satellite-derived vegetation indices, and advanced machine learning techniques. By combining unsupervised temporal representation learning through a Long Short-Term Memory autoencoder with physically constrained ordinal regression, the proposed approach infers soil texture classes without relying on laboratory-derived particle-size fractions.

Results obtained under a leave-one-soil-out validation strategy demonstrate that soil texture information is encoded within temporal soil moisture response patterns. The model achieved moderate but meaningful overall accuracy (0.54) and a low Mean Absolute Error, indicating that most misclassifications occur between adjacent texture classes. This behavior reflects both the continuous nature of soil texture transitions and the physical consistency enforced by the ordinal formulation. Loamy soils were identified most reliably, while sandy and clay soils exhibited greater uncertainty due to their contrasting hydrological extremes.

Interpretation of LSTM-derived latent embeddings using SHAP analysis revealed that a limited number of temporal features dominate the prediction process. These embeddings capture emergent soil hydraulic behaviors such as moisture persistence, drainage dynamics, and vertical redistribution, demonstrating that machine learning can extract physically meaningful information from high-dimensional environmental time series, even in data-limited settings.

The study is subject to limitations related to dataset size, soil class imbalance, and the inherent abstraction of latent representations. Future work will focus on expanding the number of soil profiles across broader climatic and pedological gradients, exploring multi-scale temporal windows, and integrating the framework into operational decision support systems for precision agriculture and climate-resilient land management.

Overall, this research demonstrates that soil texture can be inferred from environmental response dynamics alone, providing a transferable and physically consistent pathway toward non-invasive soil characterization and next-generation digital soil monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and E.D.; methodology, M.R. and E.D.; software, M.R. and T.D.; validation, M.R., T.D. and E.D.; formal analysis, M.R. and T.D.; investigation, M.R. and T.D.; resources, E.D.; data curation, M.R. and T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and E.D.; visualization, M.R. and T.D.; supervision, E.D.; funding acquisition, E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The creation of this scientific communication was supported by the University of Miskolc with funding granted to the author Endre Dobos within the framework of the institution’s Scientific Excellence Support Program. (Project identifier: ME-TKTP-2025).

Data Availability Statement

The Earth Observation datasets used in this study, including Copernicus data, are publicly available through the Copernicus Open Access Hub. The in situ sensor data used for calibration and validation are proprietary and were obtained under restricted access agreements; therefore, they are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hillel, D. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J. Using Soil Survey Data for Quantitative Land Evaluation. In Advances in Soil Science: Volume 9; Stewart, B.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 177–213. ISBN 978-1-4612-3532-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G.W.; Bauder, J.W. Particle-Size Analysis. In Methods of Soil Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 383–411. ISBN 9780891188643. [Google Scholar]

- Adamchuk, V.I.; Hummel, J.W.; Morgan, M.T.; Upadhyaya, S.K. On-the-Go Soil Sensors for Precision Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2004, 44, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Digital Soil Mapping: A Brief History and Some Lessons. Geoderma 2016, 264, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, K.E.; Rawls, W.J. Soil Water Characteristic Estimates by Texture and Organic Matter for Hydrologic Solutions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, G.; Zhang, X. Analysis of NDVI and Scaled Difference Vegetation Index Retrievals of Vegetation Fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 101, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcbratney, A.; Mendonça Santos, M.; Minasny, B. On Digital Soil Mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ließ, M.; Glaser, B.; Huwe, B. Uncertainty in the Spatial Prediction of Soil Texture: Comparison of Regression Tree and Random Forest Models. Geoderma 2012, 170, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C.d.S.; de Carvalho Junior, W.; Bhering, S.B.; Calderano Filho, B. Spatial Prediction of Soil Surface Texture in a Semiarid Region Using Random Forest and Multiple Linear Regressions. Catena 2016, 139, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, K.; Gercsák, G.; Kovács, Z.; Nemerkényi, Z.; Kincses, A.; Tóth, G.; Agárdi, N.; Koczó, F.; Mezei, G.; McIntosh, R.W. National Atlas of Hungary: Society; Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geographical Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2021; ISBN 9789639545588. [Google Scholar]

- Gábris, G.; Pécsi, M.; Schweitzer, F.; Telbisz, T. Relief. In National Atlas of Hungary—Natural Environment; MTA CSFK Geographical Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoni, J.; Szalai, S.; Szentimrey, T.; Lakatos, M.; Bihari, Z.; Nagy, A.; Németh, Á.; Kovács, T.; Mihic, D.; Dacic, M.; et al. Climate of the Carpathian Region in the Period 1961–2010: Climatologies and Trends of 10 Variables. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 1322–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibirige, D.; Dobos, E. Off-Site Calibration Approach of EnviroScan Capacitance Probe to Assist Operational Field Applications. Water 2021, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, I.; Nel, A. Sesiidae Wing Impression in Miocene (Badenian) Dacitic Tuff from Hungary (Magyaregregy, Mecsek Mountains). Lepidopterol. Hung. 2025, 22, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nrcs, U. Soil Survey Manual Soil Science Division Staff Agriculture Handbook No. 18; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paltineanu, I.C.; Starr, J.L. Real-Time Soil Water Dynamics Using Multisensor Capacitance Probes: Laboratory Calibration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1997, 61, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, I.; Yule, I.; Bretherton, M.; Singh, R.; Hedley, C. Field Performance Assessment and Calibration of Multi-Depth AquaCheck Capacitance-Based Soil Moisture Probes under Permanent Pasture for Hill Country Soils. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, G.; Rallo, G.; de Almeida, C.D.G.C.; de Almeida, B.G. Development and Validation of a New Calibration Model for Diviner 2000® Probe Based on Soil Physical Attributes. Water 2020, 12, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Qian, H.; Cao, W.; Ni, J. Design and Test of a Soil Profile Moisture Sensor Based on Sensitive Soil Layers. Sensors 2018, 18, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, J.H.; Topp, G.C. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 4: Physical Methods; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleners, T.J.; Soppe, R.W.O.; Ayars, J.E.; Skaggs, T.H. Calibration of Capacitance Probe Sensors in a Saline Silty Clay Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosny, G.; Chanzy, A.; Pardé, M.; Gaudu, J.-C.; Frangi, J.-P.; Laurent, J.-P. Numerical Modeling of a Capacitance Probe Response. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, M. Sensitivity of Capacitance Probes to Soil Cracks Courses ENG4111 and ENG4112 Research Project. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Jia, F.; Mo, B. Spatial Variations of Shallow and Deep Soil Moisture in the Semi-Arid Loess Plateau, China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3199–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hall, F.G.; Sellers, P.J.; Marshak, A.L. The Interpretation of Spectral Vegetation Indexes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.; Brady, N. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0133254488. [Google Scholar]

- Sentek. Probe Configuration Utility User Guide; Sentek Technologies: Stepney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kubat, M.; Holte, R.C.; Matwin, S. Machine Learning for the Detection of Oil Spills in Satellite Radar Images. Mach. Learn. 1998, 30, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabro, J.; Leib, B.; Jabro, A. Estimating Soil Water Content Using Site-Specific Calibration of Capacitance Measurements from Sentek EnviroSCAN Systems. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2005, 21, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUHET Sentinel-2 User Handbook. Available online: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/685211/Sentinel-2_User_Handbook (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, P.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Anand, G.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G.M. LSTM-Based Encoder-Decoder for Multi-Sensor Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.00148. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, A.; Subramaniam, A. Iterative Spatial Leave-One-out Cross-Validation and Gap-Filling Based Data Augmentation for Supervised Learning Applications in Marine Remote Sensing. GISci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durner, W.; Flühler, H. Soil Hydraulic Properties. In Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780470848944. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, S.; Funakawa, S.; Shinjo, H.; Kosaki, T. Short-Term Dynamics of Soil Organic Matter and Microbial Biomass after Simulated Rainfall on Tropical Sandy Soil. In Management of Tropical Sandy Soils for Sustainable Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, A.S.; Tanzola, J.; Asiain, L.; Ferracutti, G.R.; Castro, S.M.; Bjerg, E.A.; Ganuza, M.L. Machine Learning Model Interpretability Using SHAP Values: Application to Igneous Rock Classification Task. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.