Abstract

The accurate simulation of sub-GeV particle detectors is essential for interpreting experimental data and optimizing detector design. This work identifies and addresses several critical aspects in modeling such detectors, taking as a case study the High-Energy Particle Detector (HEPD-02), a space-borne instrument developed within the CSES-02 mission to measure electrons in the ∼3–100 MeV range, protons and light nuclei in the ∼30–200 MeV/n. The HEPD-02 instrument consists of a silicon tracker, plastic and LYSO scintillator calorimeters, and anticoincidence systems, making it a representative example of a complex low-energy particle detector operating in Low Earth Orbit. Key challenges arise from replicating intricate detector geometries derived from CAD models, selecting appropriate hadronic physics lists for low-energy interactions, and accurately describing the detector response—particularly quenching effects in scintillators and digitization in solid-state tracking planes. Particular attention is given to three critical aspects: the precise CAD-level geometry implementation, the impact of hadronic physics models on the detector response, and the parameterization of scintillation quenching. In this study, we present original solutions to these challenges and provide data–MC comparisons using data from HEPD-02 beam tests.

1. Introduction

The second China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite (CSES-02) [1,2] is a scientific satellite part of a multi-spacecraft program devoted to studying the electromagnetic, plasma, and particle environment in the low-orbit region around the Earth at about 500 km of altitude. The CSES missions program is a collaborative effort between the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and the Italian Space Agency (ASI), with the participation of several Chinese and Italian universities and research institutes. The CSES program’s most relevant objective is the observation of the perturbations involving the Van Allen belts and the Earth’s atmosphere that originated by solar [3,4,5,6] or terrestrial phenomena, producing changes in the electromagnetic fields and the charged trapped particle fluxes. CSES [7,8] aims to establish a possible statistical correlation between such transients and intense seismic phenomena [9,10].

In addition, the mission has demonstrated its capability to contribute to the continuous monitoring of high-energy transient phenomena in the gamma-ray domain, such as Gamma-Ray Bursts [11,12].

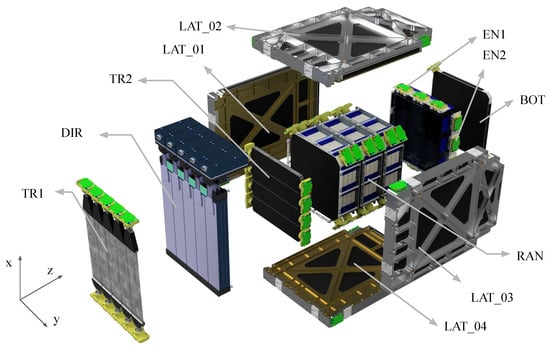

The first satellite, CSES-01, was launched at the beginning of 2018, while the second, CSES-02, is in operation as it was successfully launched in June 2025. The High-Energy Particle Detector (HEPD-02), built by the Italian Limadou collaboration, is one of the CSES-02 payloads, specifically designed to study the low-energy cosmic rays: mainly electrons in the range of 3–100 MeV and protons in the range of 30–200 MeV. HEPD-02 is an upgraded version of the predecessor HEPD-01 [13] onboard CSES-01, which is capable of performing event-based particle identification through a simultaneous measurement of the incoming particle direction and its total energy. This is achieved thanks to the information coming from its different subdetectors: plastic scintillator trigger planes (TR1 & TR2), a Direction Detector (DIR) consisting of three layers of silicon pixel tracker, a segmented calorimeter made of plastic scintillator named “range detector” (RAN), an inorganic calorimeter made of Lutetium Oxyortho Silicate (EN1 & EN2) or LYSO, and an anticoincidence detector made of plastic scintillator (LAT_01 - LAT_04, BOT). Figure 1 shows the detector assembly and its components.

Figure 1.

The HEPD-02 assembly onboard CSES-02 with its subdetectors: trigger planes (TR1 & TR2), silicon pixel direction detector (DIR), range detector (RAN) made of plastic scintillator, LYSO calorimeter (EN1 & EN2), Anticoincidence Detector (LAT_01 - LAT_04 & BOT).

HEPD-02 features the first space-borne pixel silicon tracker [14,15,16], representing an important advancement for particle spectrometry in space.

In this work, we present a detailed Geant4-based Monte Carlo (MC) simulation of the HEPD-02 detector, accurately replicating its geometry, response, and signal digitization to produce realistic data. We also include performance benchmarking and validation against expected detector behavior, establishing the simulation as a key tool for mission operations and data analysis.

2. Monte Carlo Simulation Setup and Geometry Modeling

Monte Carlo simulations reproduce the detector response under controlled initial conditions and provide a reference for validating the modeling of physical interactions within the system. MC techniques [17] are particularly useful for complex detector geometries such as that of HEPD-02. Radiation transport tools like Geant4 [18], FLUKA [19], and McStas [20], combined with accurate descriptions of geometry and physics models for radiation-matter interactions, allow one to sample the detector response. This is particularly important for unfolding procedures [21,22], which depend critically on a precise understanding of the experimental apparatus.

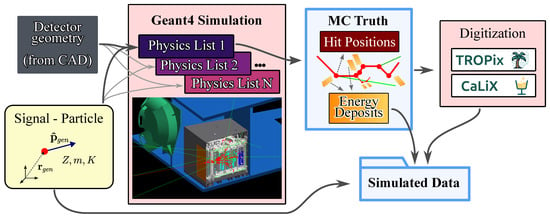

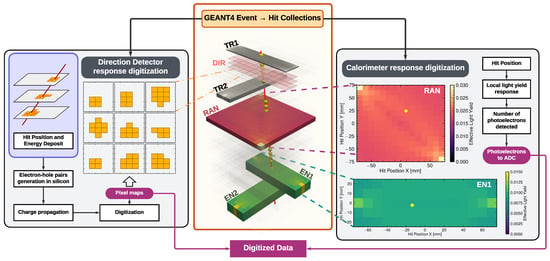

The overall Monte Carlo simulation workflow adopted for HEPD-02 is illustrated in Figure 2. The input to the simulation consists of the detector geometry, described in GDML format and imported directly from the detailed CAD model (see Section 2.1), and of the generated primary particle parameters, including position , direction , charge Z, mass m, and kinetic energy K. The Geant4-based simulation (central block in Figure 2) propagates the particle through the full detector model, accounting for the relevant physical interactions as defined by the selected physics list. The MC simulation of the HEPD-02 instrument has been developed using the Geant4 toolkit (version 10.6.1) [18]. The entire simulation pipeline is parallelized so that independent runs can be performed concurrently on the computing cluster, each using a different physics list configuration. The output of each simulation branch is a collection of Monte Carlo truth data, including the particle hit positions and the energy deposited in each sensitive volume at every simulation step.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the Monte Carlo simulation chain for HEPD-02. The detector geometry from CAD and the generated particle parameters are used as inputs to the Geant4 simulation, producing MC truth information (hit positions and energy deposits) that is subsequently processed by the TROPix and CaLiX digitization modules to generate simulated data.

These MC truth quantities are subsequently processed by two dedicated digitization packages: TROPix, which handles the tracker readout simulation, and CaLiX (Calorimeter Light eXtraction), which models the calorimeter optical and electronic response. The digitization stage converts the analog energy deposits into discrete signal units, producing data structures fully consistent with the experimental raw data format. Additional metadata, such as the deposited energies in individual detector volumes and the projectile information, are also attached to the simulated output, enabling a direct comparison between data and Monte Carlo at multiple levels of the reconstruction chain.

2.1. Precise CAD-Level Geometry of the Experiment

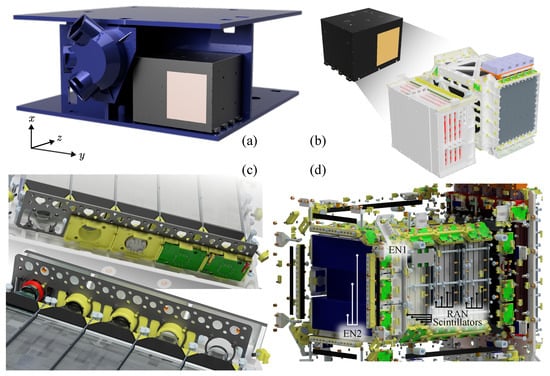

A high-fidelity simulation of the HEPD-02 detector requires an accurate implementation of its geometrical model. The detailed CAD model of the HEPD-02 payload was therefore adopted as the primary source for the detector description. The geometry was initially provided in STEP (STandard for the Exchange of Product model data) format [23], a standard for CAD data exchange ensuring interoperability between different design platforms. Since this format is not directly compatible with the Geant4 framework, it was converted into GDML (Geometry Description Markup Language) [24], an XML-based format suitable for physics simulations. For HEPD-02, the conversion from STEP to GDML was performed using the GUIMesh tool [25]. Since the mechanical model was available as a STEP file, we used GUIMesh/FreeCAD for the STEP-to-GDML conversion; however, CADMesh is a viable alternative when the geometry is provided as triangular meshes (e.g., STL/PLY/OBJ) [26]. To reproduce the in-flight configuration of the experiment, the most relevant structural components of the CSES-02 satellite were included in the model. Before conversion, the metallic structures—such as lateral panels and the star tracker—were simplified in Autodesk Fusion 360 [27] by removing small inserts, screws, and apertures. The final GDML files were produced with the FreeCAD GDML Workbench [28], and the geometrical consistency was verified using the overlap-checking procedure.

Figure 3 illustrates the full geometry implemented in the Geant4 simulation. Panel (a) shows the geometry as placed in the world volume, where the payload structure is rendered in black, the particle entrance window in a copper-like color, and the satellite body with the star tracker—both modeled in aluminum—are shown in blue. Panel (b) depicts the CAD representation of the HEPD-02 payload with and without the external mechanical structure, showing both the detector subsystem (right) and the electronics subsystems (left). Panel (c) shows some details of the TR1 subdetector, including the photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), optical pads, and mechanical supports. Panel (d) presents the complete detector assembly with all mechanical details, screws, PMTs, and passive structures.

Figure 3.

Overview of the HEPD-02 detector geometry implemented in the simulation. (a) Geometry placed in the world volume with the satellite body and star tracker. (b–d) Detailed CAD representation of the payload and subdetectors, including mechanical structures, PMTs, and electronic boards.

2.2. Impact of Physics Models on the Detector Response

For the HEPD-02 virtual model, well-established Physics Lists commonly used in high-energy physics experiments have been adopted [29]. The baseline Physics List is QGSP_BIC, chosen for its reliable treatment of hadronic interactions across the HEPD-02 energy range. In Geant4, QGSP_BIC combines the Binary Cascade (BIC) for protons and neutrons below 6 GeV, the Bertini cascade model [30] for pions, kaons, and hyperons in the same range, the Fritiof model (FTF) [31,32] from 3 to 25 GeV, and the Quark–Gluon String model (QGS) [33] above 12 GeV. After the initial interaction, the Precompound and pre-equilibrium models [34,35] handle the de-excitation of residual nuclei.

To improve the accuracy of electromagnetic interactions at MeV and sub-MeV energies, the standard electromagnetic physics module is replaced with G4EmStandard_option4, which provides refined treatments of multiple scattering, energy loss, and electron–photon interactions, at the cost of increased computational time [36]. Furthermore, to simulate LYSO radioactivity and calibration with radioactive sources, the G4RadioactiveDecay module is included [37,38], which also accounts for intrinsic background contributions.

The Geant4 application was instrumented to enable runtime selection of the physics list and fine-grained replacement of individual physics constructors via macro files. This flexibility supports systematic studies of model-dependent effects and the characterization of related uncertainties [39,40,41].

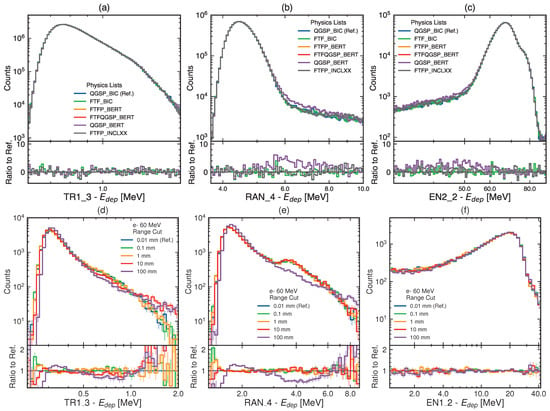

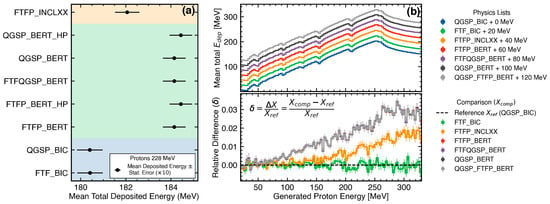

The relative performance of different physics lists is shown in Figure 4a–c, which reports energy-deposition distributions and ratios in three representative calorimeter units for 228 MeV protons. In this simulation, the beam is directed along the z-axis and focused on the center of the detector. The reference QGSP_BIC (blue) is compared against FTF_BIC (green), FTFP_BERT (orange), FTFQGSP_BERT (red), QGSP_BERT (purple), and FTFP_INCLXX (dark gray). At this energy, the ratio panels indicate overall agreement within statistical uncertainties.

Figure 4.

Distributions of MC truth energy deposits in different HEPD-02 calorimeter units under varying simulation parameters. Top panels (a–c): Proton simulations (228 MeV) comparing different physics lists. Bottom panels (d–f): Electron simulations (60 MeV) with varying range cuts for secondary production. Statistical uncertainties are shown as error bars.

Figure 5 summarizes the dependence on incident energy. Also in these simulation runs, the proton beam is directed along the z-axis and focused on the center of the detector. Panel (b) shows that differences among families increase across 50–300 MeV. The dominant contributors are the intra-nuclear cascade models (BIC, BERT, and INCLXX) which govern hadronic interactions in the sub-GeV regime; the HP suffix denotes high-precision neutron extensions below 20 MeV based on evaluated data libraries [42]. At the highest energies (∼300 MeV), the mean deposited energy differs by about 3% between _BERT and _BIC, and by about 2% between _INCLXX and _BIC. These differences are statistically significant at 228 MeV as well, where panel (a) indicates offsets of roughly 4 MeV for _BERT vs. _BIC and 1.5 MeV for _INCLXX vs. _BIC. Such trends are consistent with known modeling variations in inelastic interactions and secondary-particle cascades. Below ≈70 MeV, the relative differences among the different hadronic physics lists become compatible within the statistical errors due to the predominant electromagnetic component of the interaction. No significant differences are observed between the “Fritiof Precompound” (FTFP_) and the “Quark Gluon String Precompound” (QGSP_) models, as these are typically invoked only when the particle energy exceeds 3 GeV and 12 GeV, respectively, which is not the case in this simulation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different physics lists in Geant4 simulations for HEPD-02. Panel (a): Mean total deposited energy for 228 MeV protons across different physics lists with statistical uncertainties (multiplied by a factor 10 for visualization purposes). Panel (b): Mean total deposited energy versus incident proton energy (top) and relative difference with respect to the QGSP_BIC reference (bottom). In both panels, the background shading distinguishes physics-list families: blue for _BIC, green for _BERT, and orange for _INCLXX.

These mismatches will be further investigated to assess the impact of the simulation model on the systematic uncertainties associated with the analysis of flight data.

The simulation software enables adjustment of range cuts between different MC runs. This parameter sets a length-based threshold that determines the minimum energy required for secondary particle production from processes like ionization and other electromagnetic interactions. Secondary particles that lack sufficient kinetic energy to exceed this distance are not explicitly generated; instead, their energy is deposited locally along the track.

Lowering the range cut threshold provides a more detailed modeling of the topology of energy deposition in materials, enhancing the accuracy of the simulation. However, this comes at the cost of increased computational complexity, leading to a higher number of generated and stored hits. Therefore, an optimal trade-off must be established between accuracy in energy deposition modeling and data storage efficiency.

Within the detector, micrometer-scale accuracy in energy deposition is required only in specific sensitive detector volumes. To achieve this localized increase in spatial resolution, different G4Regions have been instantiated. A G4Region is an object that can be assigned to multiple simulation volumes, allowing the user to specify custom properties such as different range cuts or specialized physics models.

To ensure a proper representation of energy deposition within the DIR, which employs ALTAI silicon pixel sensors [16] with a thickness of 50 m, the range cut has been set to 1 m. In the first trigger plane (TR1), which is 2 mm thick, the range cut has been set to 10 m. In the second trigger plane (TR2) (4 mm thick) and in the Range Detector (RAN) (5 mm thick scintillating slabs of plastic scintillators), the range cut has been set to 40 m. For all remaining volumes belonging to passive materials, and also the electromagnetic calorimeter units EN1 and EN2, the range cut follows the default Geant4 value of 1 mm. Range cut values can be adjusted for fine-tuning analyses by the user thanks to dedicated UI commands.

A study of the energy deposition response (MC truth) is presented in the lower panels of Figure 4d–f. These plots show the energy deposited in three different subdetectors incident 60 MeV electrons with the beam directed along the z-axis and focused on the center of the detector. It can be observed that setting an excessively large range cut (100 mm) leads to nonphysical behavior in the simulation. In contrast, choosing a range cut that corresponds to a small fraction of the characteristic size of the subdetector ensures accurate modeling, as indicated by the ratio plots: the distributions obtained with the finest range cut are nearly compatible with unity. For the EN1 calorimeter unit, the ratio plots remain compatible with unity at larger range cuts because their thickness is about 3 cm. We observe that for the examples shown in Figure 4d–f, restricting the range cuts from 0.1 mm to 0.01 mm results in a computation time increase within a factor of 10.

2.3. Event Generation

A key innovation of the HEPD-02 Monte Carlo code is the implementation of a dedicated beam test mode that enables accurate reproduction of experimental beam conditions. The application allows users to specify the incident particle spectrum by setting the beam’s initial position , angular distribution (via polar angles with respect to the z-axis), and energy spectrum. To account for realistic beam profiles, position and angular dispersions are parameterized as and projected angles , , respectively.

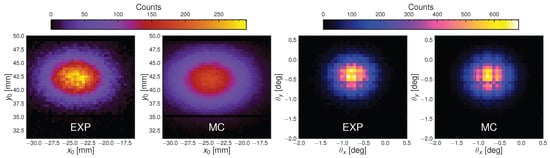

These parameters are tuned iteratively to match the distributions of reconstructed variables from the DIR, as shown in Figure 6. These plots show both experimental data and MC simulations for a run acquired during the beam-test campaign with 228 MeV protons. The simulated events are analyzed after the digitization and event-reconstruction procedure. This iterative tuning procedure is essential because particle interactions with detector materials modify the trajectory, making the input parameters only indicative of the final reconstructed distributions. Once tuned against experimental data (e.g., 228 MeV proton beam test), the MC code reliably reproduces beam conditions for quantitative data–MC validation.

Figure 6.

Reconstructed position and angular distributions from 228 MeV proton beam test compared with MC simulation after parameter tuning.

Beyond beam test applications, the code also supports cosmic ray studies via the standard G4GeneralParticleSource, including the intrinsic radioactivity of 176Lu in LYSO crystals when needed.

2.4. Output Data Structure and MC Truth Information

The simulation framework outputs ROOT files [43] containing both MC truth and digitized detector response. MC truth information includes the primary particle kinematics (PDG code [44], mass, charge, initial position, momentum, kinetic energy) and detailed records of energy deposits throughout the detector.

Particle trajectories through the detector are represented discretely via hit objects recorded at each propagation step. Each hit captures essential information for systematic studies: deposited energy, particle identity (PDG code), step length, position, and kinematic variables (momentum, kinetic energy). This granular recording of energy deposits enables subsequent reconstruction of detector response and traceability to physical processes. To facilitate background and systematic studies, the framework also records energy depositions in inert materials (passive detector elements, shielding, support structures). However, only hits in active detector volumes contribute to the final digitized signals—inert material hits serve purely for analysis purposes and are discarded during digitization.

3. Digitization and Subdetectors Response Modeling

Accurate digitization is essential to enable direct comparison between MC and experimental data. We describe the transduction chain from physical observables (energy deposits, ionization) to digitized signals (ADC counts, pixel maps).

A simplified scheme of the digitization procedure followed by the HEPD-02 virtual model is depicted in Figure 7. The procedure begins with the collection, for each event, of a series of hits representing the energies deposited at discrete points along particle tracks. Each hit is defined as , where and are the start and end positions of the step, and is the deposited energy.

Figure 7.

MC digitization chain: deposited energy from Geant4 (MC truth) is converted to detector signals via calorimeter light yield maps (CaLiX) and a parameterized charge diffusion model for the DIR (TROPix).

The first step of the digitization consists in the generation of the pixel clusters within the DIR. For this task, the TROPix software (version 1.0) [45] (Section 3.2) is used. The information about the fired pixels is then attached to each event.

The scintillating calorimeter digitization involves several physical transduction steps: energy deposition is converted into scintillation light, which depends on the ionization density distribution [46]. Photons propagate through the scintillator, undergoing reflections and absorptions before detection by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) with limited quantum efficiency. We use a parametric approach based on experimental response maps (Section 3.1) to capture these effects and reduce computational demands.

At each step of the particle track within the scintillator, the local energy loss per unit length is calculated as:

The local energy deposition can then be converted into an averaged number of photons emitted :

where LY is the nominal light yield, and Q is the quenching factor describing non-linearity at high ionization density, parametrized by . Within this general formulation, represents a set of parameters of the model adopted for the quenching mechanism. The non-linearity in Equation (2) becomes important at high-ionization densities.

Scintillation quenching, the reduction in light yield at high ionization density, is often parameterized empirically by the Birks model [46]. However, for sub-GeV particles interacting with modern scintillators, both saturation effects and exciton recombination mechanisms must be accounted for to achieve accurate modeling. The Birks–Onsager parameterization [47,48,49,50,51] incorporates these factors and provides an improved description across the full ionization density range:

where is the limiting minimum luminous efficiency (saturation), quantifies the contribution from exciton recombination at scintillator recombination centers, and sets the characteristic ionization density scale for the recombination process.

The generated scintillation photons at each step (Equation (2)) must be converted into detected photoelectrons. This is achieved using position-dependent response maps , where R represents the detection efficiency—the ratio of photoelectrons detected by the PMT to generated photons—as a function of hit position . These light yield maps are generated and applied within the CaLiX code section. Derivation of these maps is described in Section 3.1. The detected photoelectron contribution from each hit is:

Two examples of maps are displayed on the right-hand side of Figure 7. The average number of detected photoelectrons by a PMT coupled to the scintillator is given by the sum of all the terms expressed by Equation (4)

where is the number of hits within the scintillator of interest acquired during an event.

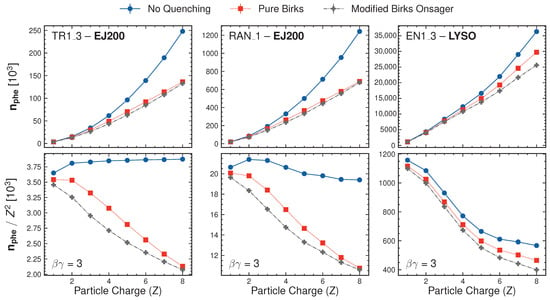

To provide a practical example, Figure 8 compares three quenching models (no quenching, pure Birks, and Birks–Onsager) by showing the photoelectron yield and charge-normalized response across nuclear charges for minimum-ionizing particles in three HEPD-02 subdetectors (TR1, RAN, and EN1). For protons (), the models agree within 5% in both plastic (EJ200) and LYSO scintillators. However, discrepancies grow with charge: in EJ200, differences reach approximately 10% at , while in LYSO the two Birks models agree within 10% up to . The charge-normalized yield (lower panels) isolates the quenching effect, clearly showing the systematic suppression introduced by the Birks–Onsager model at lower ionization densities compared to pure Birks.

Figure 8.

Photoelectron yield (top) and charge-normalized yield (bottom) versus nuclear charge Z for minimum-ionizing particles () in three HEPD-02 subdetectors. Comparison of three quenching models: no quenching (blue circles), pure Birks (red squares), and Birks–Onsager (grey crosses).

The real detected number of photoelectrons is then sampled from a Poisson distribution with the mean parameter equal to the expected number of detected photoelectrons from Equation (5). The number of photoelectrons is then mapped to the ADC domain through a one-dimensional sigmoid parameterization (each PMT has its own parameterization from experimental characterizations [52]) given by the following:

where a, k, are parameters estimated via Data–MC comparison. In the final digitized charge, expressed in ADC, additional electric noise, modeled as a zero-mean normal random distribution, is considered.

At the end of digitization, MC data are formatted identically to experimental data and can be fed directly into the reconstruction pipeline for production of reconstructed-level data products. The event reconstruction methodology is beyond the scope of this work and will be addressed in future publications. The key distinction between MC and experimental data is that MC files include a truth-level database with particle generation information and energy deposits, enabling validation of the MC predictions against real measurements.

3.1. Modeling the Optical Response of the Scintillating Counters

The initial step in achieving optimal digitization is to adjust the simulated detector response to best match the experimental data. This involves tuning the optical response of the individual counter. To do this, a standalone Geant4 MC simulation (described in [53]) was developed for each type of scintillation counter, taking into consideration the propagation and energy release of the incident particle in the material, as well as the production of scintillation photons. These photons are produced from a parameterization of the emission spectra of the scintillators (EJ-200, LYSO:Ce) and then propagated according to the refractive index, absorption length in the materials, and reflectivity of the wrapper. Based on the PMT quantum efficiency, photons reaching the photocathode surface may be converted into photoelectrons. For every primary event, the integrated number of photoelectrons generated is recorded at each end of the counter, and the charge is calculated by multiplying this number by the PMT gain. The result is then compared to experimental data obtained in the laboratory under cosmic ray muons. For every counter, bi-dimensional maps are produced showing the mean number of photoelectrons/charge, relative to the center of the counter, as recorded by each phototube. These maps are based on the energy deposit and the impact position of the incident particle, with bins arranged along the transverse and longitudinal axes. The bin size and total number of bins are chosen according to the geometrical dimensions of each individual counter. A detailed investigation was carried out to study the distribution of the mean number of photoelectrons recorded as a function of the deposited energy when the primary ion traverses the center of the counter. The complete digitization of the counter response is achieved through the combination of 2D maps (Figure 7) and the parameterized average number of photoelectrons as a function of the deposited energy.

3.2. Modeling of the Direction Detector Response

The modeling of the output of the HEPD-02 pixel tracker is handled using TROPix [45]. This tool is designed to model the response of silicon pixel detectors. Developed specifically for the DIR of the HEPD-02, TROPix integrates Geant4 for energy deposition simulations and employs a parametric approach for charge generation and diffusion.

The main steps of the simulation process include:

- Charge deposition: energy deposited by incident particles in the active silicon material is converted into primary charge carriers;

- Charge propagation: the movement and diffusion of the generated charges are modeled using a parametric approach;

- Digitization: active pixels are determined after applying noise contributions and threshold comparisons.

The simulation begins with the conversion of deposited energy into released charge within the silicon sensors. This process follows a Landau distribution, characterized by a location parameter and a scale parameter , where k = 3.6 eV represents the energy needed to create an electron–hole pair in silicon [54].

Charge transport is handled through parametric Gaussian smearing, which models the diffusion of primary charge carriers. The diffusion parameters are finely calibrated using data from experimental beam tests, ensuring an accurate representation of charge spread within the sensor.

Finally, the accumulated charge distribution is mapped onto the hit map, providing a spatial visualization of the active pixels in the silicon chip. The digitization process determines active pixels by comparing the collected charge to a threshold map, ensuring that only pixels exceeding the predefined threshold are recorded as hits.

4. Experimental Data and Monte Carlo Comparison

4.1. Calorimeter Response Validation

For validation of the HEPD-02 MC pipeline, we used a 62,000-event sample from a 228 MeV beam test at the APSS Proton Therapy facility in Trento [55]. Since both data and MC are produced in identical L2 data format, they are analyzed using the same reconstruction algorithms, ensuring a fair and unbiased comparison. To ensure the analysis of a pure proton sample without pile-up, only events with one reconstructed track in the DIR are considered.

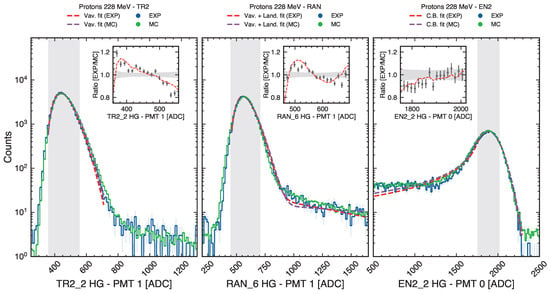

The first validation focuses on the calorimeter subsystem response, shown in Figure 9. The figure compares ADC signal distributions from three calorimeter elements: TR2 and RAN (plastic scintillators) and EN2 (LYSO), each read out by dedicated photomultiplier tubes. MC distributions are scaled to match the total number of events in the experimental data to allow direct shape comparison. Both data and MC error bars represent Poisson statistical uncertainties on the bin counts. The naming convention follows the pattern Subdetector_i HG - PMT j, where i indexes the scintillator element and j labels the PMT readout channel via the high-gain amplifier stage. The insets present the EXP/MC ratio, quantifying agreement by showing how well the MC prediction matches the measured distribution; gray bands in the insets indicate the statistical uncertainty band, derived from the combined errors of data and MC. All error bars represent statistical uncertainties only.

Figure 9.

ADC signal distributions from experimental data and MC simulation for 228 MeV vertical protons in three HEPD-02 calorimeter elements: TR2 and RAN (plastic scintillators) and EN2 (LYSO). The insets display EXP/MC ratios, evaluated for the bulk of the distributions (vertical shaded area in the main panels). Horizontal shaded bands in the insets represent statistical uncertainties. Fitting procedures and detailed comparisons are presented in Section 4.1 and Appendix B.

To compare the ability of the simulation to reproduce the MPVs and widths of the experimental distributions, physics-motivated functions were adopted.

Vavilov distributions have been used for the bulk of TR2 and RAN, and a Crystal Ball function for EN2 (capturing both the peak and low-energy tail). For TR2 and RAN, the fit is restricted to the well-populated peak region. The RAN scintillator produces a statistically significant high-energy tail which may be modeled by an additional Landau component.

The simulation reproduces the peak positions (Most Probable Value, MPV) with percent-level accuracy. For TR2, the data shows ADC compared to ADC. The RAN detector yields ADC versus ADC, while EN2 shows ADC compared to ADC. Regarding the signal widths, the simulation provides a consistent description for TR2 and EN2, whereas a larger width is observed in the Monte Carlo distribution for the RAN detector (see Table A2).

Small residual discrepancies in the MPV positions (e.g., the ∼0.7% offset observed in EN2) are likely due to systematic effects in the absolute energy calibration and the digitization chain (e.g., optical response and quenching modeling).

In the final physics analyses, these sources of systematic uncertainty, together with those related to the choice of hadronic physics list at the MC-truth level, will be quantified and propagated to the final results.

4.2. DIR Response Validation

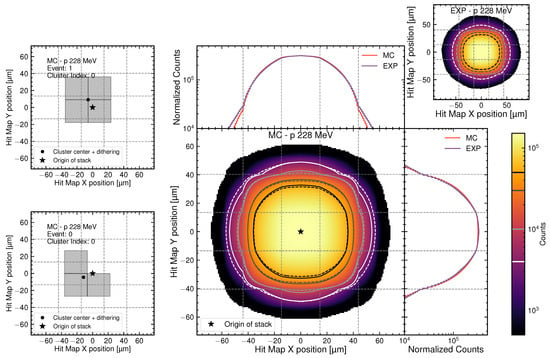

The second key step in the data–MC comparison is the validation of the digitization procedure for the DIR subsystem. After reconstruction, which is applied identically to both experimental and simulated data to produce L2 data products, pixel clusters can be analyzed. To assess the overall DIR modeling performance and its fidelity to experimental observations, a sophisticated stacked cluster analysis is performed, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Stacked hit-map analysis of pixel clusters in the HEPD-02 tracker from 228 MeV vertical proton beam. Left panels: illustration of cluster re-centering on barycenter with uniform dithering ( pixel units). Central panel: 2D distribution from MC simulation (solid contours) overlaid with experimental data contours (dashed). Both panels share the same axis limits; the dashed grid indicates the pixel pitch (29.24 µm in x and 26.88 µm in y). Top and right panels: 1D projections along X and Y axes comparing MC (red) and experimental (violet) data.

The reconstruction pipeline performs pixel clustering by grouping adjacent activated pixels, with each cluster representing a single particle impact. Quality selection retains only events containing exactly one reconstructed track composed of three pixel clusters (one per DIR layer). For each cluster, individual pixel coordinates are combined to compute the cluster barycenter: and , where pixel pitch is and [16].

To enable meaningful spatial comparison across many clusters, each cluster is re-centered at the origin by subtracting its barycenter coordinates from all constituent pixels. However, since the true hit position within each pixel is unknown and can lie anywhere within the pixel boundaries, a uniformly distributed random shift (dithering) of pixel units is applied to the cluster centroid before stacking. This procedure, illustrated in the left panels of Figure 10, properly accounts for sub-pixel uncertainties inherent to discrete detector readout. The centered and dithered clusters are then superimposed on a fine-grained spatial grid and used to build a two-dimensional histogram: bins of the fine grid that fall within pixels of the cluster are incremented by one, and this is repeated for all clusters in both MC and experimental datasets.

The resulting 2D hit maps are shown for MC simulation (central panel) and experimental data (top-right panel). To facilitate direct visual comparison, iso-density contour lines at matched levels (from the logarithmic color scale) are drawn on both maps: solid contours represent MC while dashed contours represent experimental data. The one-dimensional projections along the X and Y axes (top and right panels) show the marginal distributions obtained by integrating the 2D maps.

Importantly, these projections are normalized by dividing by the number of fine-grid bins corresponding to one pixel width, rendering the vertical axis independent of the underlying binning and allowing meaningful comparison of “effective pixel activation” between data and simulation.

The projections show good agreement (at the level of ∼10%) between MC and experimental data in the bulk region, while larger deviations are confined to the tails, which are dominated by less frequent cluster topologies and are more sensitive to the details of the digitization model [45].

Another potential source of systematic uncertainty arises if inter-chip or intra-chip misalignment in the TROPix readout array is present but not accounted for in the digitization model; such misalignment would distort reconstructed cluster morphology and bias spatial and cluster-size measurements. However, from individual events alone, it is impossible to distinguish between genuine cluster shapes arising from particle straggling versus artificial distortions induced by unknown detector misalignment. Therefore, chip alignment constants must be determined independently through dedicated metrological calibration procedures applied to flight data.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we showed the development and validation of a Monte Carlo model of the HEPD-02 detector aboard the CSES-02 satellite, addressing the critical aspects inherent to accurate simulation of sub-GeV particle interactions.

First, CAD-level geometry implementation with tessellation techniques ensures faithful representation of detector complexity, from scintillator layer stacking to silicon tracker pixel alignment. Second, systematic comparison of Geant4 hadronic physics lists reveals non-negligible differences in energy deposition across the sub-GeV spectrum, with BERT and BIC models differing by approximately 4 MeV at 228 MeV, with a relative difference slightly increasing toward higher energies. This systematic effect must be carefully evaluated for accurate detector response modeling. Third, implementation of the Birks–Onsager scintillation quenching model, whose validation against beam-test data was presented in previous works [50,51], properly accounts for both saturation and recombination mechanisms relevant to sub-GeV particle detection in plastic and inorganic scintillators. In Appendix C (Table A3), the main sources of systematic effects are listed.

Beam test comparisons demonstrate reasonable agreement between data and simulation across detector subsystems: calorimeter ADC distributions agree within a few percent in peak position, and pixel cluster morphologies match within 10% in spatial distribution. These results indicate that the current digitization procedures and physical models capture the main mechanisms governing detector response under controlled beam test conditions, though systematic uncertainties remain to be fully characterized.

With CSES-02 now in orbit, HEPD-02 is acquiring cosmic-ray data in the sub-GeV range. The detector model validated in this work will be used for the flight data analysis, where systematic uncertainties from hadronic physics lists, quenching, and digitization will be propagated to the final flux measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B., C.D.S., and R.I.; methodology, A.D.L., F.M.F., B.P., and Z.S.; software, A.D.L., F.M.F., R.N., B.P., and Z.S.; validation, A.D.L., F.M.F., R.I., F.N., B.P., and Z.S.; formal analysis, A.D.L., R.I., R.N., F.N., B.P., and Z.S.; investigation, R.B., R.I., R.N., F.N., and Z.S.; resources, R.B., C.D.S., R.I., and P.P.; data curation, A.D.L., F.M.F., R.N., and Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.L., R.N., B.P., and Z.S.; writing—review and editing, S.B. (Simona Bartocci), R.B., S.B. (Stefania Beolè), F.B., P.C., S.C., A.C., M.C., C.D.D., C.D.S., A.D.L., F.D., F.M.F., S.G.B., G.G., R.I., A.L., M.L., G.M., M.M. (Matteo Mergè), M.M. (Marco Mese), R.N., F.N., A.O., G.O., F.P. (Francesco Palma), F.P. (Federico Palmonari), B.P., S.P., F.P. (Francesco Perfetto), P.P., M.P., M.R., E.R., S.B.R., Z.S., U.S., V.S., E.S., A.S., R.S., P.U., V.V., S.Z., and P.Z.; visualization, R.N. and Z.S.; supervision, R.B., C.D.S., and R.I.; project administration, R.B., C.D.S., R.I., P.P., R.S., and S.Z.; funding acquisition, R.B., C.D.S., R.I., P.P., R.S., and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) in the framework of the “Accordo attuativo 2019-22-HH.0 Programma Limadou-2 attività di fase B2/C/D/E1” and the ASI-INFN agreement n. 2021-43-HH.0.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC | Analog-to-Digital Converter |

| ASI | Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (Italian Space Agency) |

| BOT | Bottom anticoincidence detector |

| CaLiX | Calorimeter Light eXtraction |

| CSES | China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite |

| DIR | Direction Detector (silicon pixel tracker) |

| EN1/EN2 | Energy calorimeter units made of LYSO crystals |

| GEANT4 | Geometry and Tracking 4 simulation toolkit |

| GDML | Geometry Description Markup Language |

| HEPD-01 | High-Energy Particle Detector on board CSES-01 |

| HEPD-02 | High-Energy Particle Detector on board CSES-02 |

| INFN | Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare |

| LAT | Lateral anticoincidence detectors |

| LYSO | Lutetium–Yttrium Orthosilicate (inorganic scintillator) |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PDG | Particle Data Group |

| PMT | Photomultiplier Tube |

| RAN | Range Detector (plastic scintillator calorimeter) |

| STEP | Standard for the Exchange of Product model data |

| TR1/TR2 | Trigger planes 1 and 2 |

| TROPix | Tool Reproducing the Output of the HEPD-02 Pixel detector |

Appendix A. Material Properties in the HEPD-02 Detector Geometry

In this appendix we report the properties of the materials used in the HEPD-02 MC model.

Table A1 shows how the properties of the materials are modeled within the Geant4 application. All the chemical compositions, material densities, and refractive indexes, when applicable, are taken from the manufacturer’s datasheet. Furthermore, for single-element materials, such as Aluminum or Silicon, the embedded material catalog from NIST is used. For the materials composed of multiple elements, the chemical composition is provided using the notation , where X represents the chemical element symbol and Y denotes its percentage by weight in the material. Radiation lengths, nuclear interaction lengths, and electron densities have been directly computed using the Geant4 toolkit. When applicable and required by optical simulations, the average refractive index of the material is reported.

Table A1.

Properties of the materials used in the HEPD-02 MC model.

Table A1.

Properties of the materials used in the HEPD-02 MC model.

| Material Name | Density (g/cm3) | Radiation Length (cm) | Nuclear Interaction Length (cm) | Electron Density (1017 cm−3) | Composition | Average Refractive Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum G4_Al (NIST) | 2.70 | 8.90 | 38.89 | 7.83 | Al | - |

| Aluminized Mylar | 1.40 | 28.11 | 56.98 | 4.33 | H3.0 C63.0 O32.0 Al2.0 | 1.64 |

| Kapton | 1.42 | 28.61 | 55.55 | 4.40 | H3.0 C69.0 N7.0 O21.0 | - |

| Copper G4_Cu (NIST) | 8.96 | 1.44 | 15.59 | 24.62 | Cu | - |

| Plastic Scintillator EJ-200 | 1.02 | 42.92 | 70.59 | 3.34 | H8.5 C91.5 | 1.58 |

| Acrylic Light guide | 1.19 | 34.07 | 62.71 | 3.86 | H8.0 C60.0 O32.0 | 1.56 |

| Silicon G4_Si (NIST) | 2.33 | 9.37 | 45.66 | 6.99 | Si | - |

| LYSO | 7.10 | 1.22 | 21.46 | 18.39 | Lu71.4 Y4.0 Si6.4 O18.1 Ce0.1 | 1.81 |

| Araldite | 1.05 | 40.01 | 69.15 | 3.45 | H9.5 C63.1 O10.5 N17.0 | - |

| Optical pads EJ-560 | 1.03 | 29.78 | 78.65 | 3.34 | C32.0 H8.0 O22.0 Si38.0 | 1.43 |

| BSGlass | 2.23 | 13.38 | 41.38 | 6.67 | Si27.0 B5.0 Na3.0 Al1.0 O64.0 | 1.47 |

| Poron-0.23 (compressed) | 0.23 | 175.29 | 287.64 | 0.83 | C20.0 O40.0 H20.0 N20.0 | - |

| Poron-0.16 | 0.16 | 251.97 | 413.48 | 0.58 | C20.0 O40.0 H20.0 N20.0 | - |

| Poron-0.2 (compressed) | 0.20 | 201.58 | 330.79 | 0.72 | C20.0 O40.0 H20.0 N20.0 | - |

| Poron-0.4 (compressed) | 0.40 | 100.79 | 165.39 | 1.44 | C20.0 O40.0 H20.0 N20.0 | - |

| Poron-0.46 (compressed) | 0.46 | 88.61 | 145.40 | 1.64 | C20.0 O40.0 H20.0 N20.0 | - |

| Carbon Fibre | 1.55 | 27.14 | 50.23 | 4.80 | C85.0 H3.0 N4.0 O8.0 | - |

| GT-2 Tape | 1.33 | 23.13 | 60.79 | 4.32 | Si37.8 O21.6 H8.2 C32.4 | - |

| 3m Duct Tape | 0.95 | 47.13 | 71.18 | 3.26 | H14.4 C85.6 | - |

| GT-1 Tape | 1.33 | 23.13 | 60.79 | 4.32 | Si37.9 O21.6 H8.2 C32.4 | - |

| PEEK | 1.32 | 31.48 | 58.45 | 4.14 | H4.2 C79.2 O16.6 | - |

Appendix B. Fitting Models for Calorimeter Signal Distributions

In this appendix, we provide a detailed description of the fitting models used to analyze the ADC signal showed in Figure 9. The distributions from both experimental data and Monte Carlo have been acquired using a 228 MeV proton beam at Trento Proton Therapy Center [55]. Different calorimeter components, at different detector depths, have been considered: TR2 (second trigger layer of plastic scintillator), the 6th layer of the RAN (the range detector composed of 12 layers of plastic scintillator), and EN2 (the second layer of the LYSO inorganic scintillator in the calorimeter). For the TR2 ADC distributions, a Vavilov function [56] has been used to fit the bulk of the distribution:

where A is a height normalization factor, MPV is the most probable value of the distribution, Scale is a scaling factor for the x-axis.: Vavilov distribution function implemented in ROOT. The parameter is defined as:

where is the mode of the Vavilov distribution for given parameters and k. For the RAN ADC distributions, to model the bulk of the distribution, the Vavilov function has been used. To account for the asymmetric tail on the right side of the distribution, a Landau function can be added. Finally, for the EN2 ADC distributions, a Crystal Ball function has been used to fit the bulk of the distribution:

where A is a height normalization factor, MPV is the most probable value of the distribution, is the standard deviation of the Gaussian core, and and n are parameters that define the tail of the distribution. The results of the fitting procedure for both experimental data and Monte Carlo simulations are summarized in Table A2. Systematic errors have been assessed by performing repeated fits with randomized fit ranges.

Table A2.

Summary of the best-fit parameters () obtained for the three subdetectors. For TR2, the energy-loss distributions are described by a single Vavilov function. For RAN, a Vavilov model is adopted to describe the bulk of the distribution. For EN2, the Crystal Ball function provides an effective description of the low-energy tail. MPV and scale parameters are expressed in ADC counts.

Table A2.

Summary of the best-fit parameters () obtained for the three subdetectors. For TR2, the energy-loss distributions are described by a single Vavilov function. For RAN, a Vavilov model is adopted to describe the bulk of the distribution. For EN2, the Crystal Ball function provides an effective description of the low-energy tail. MPV and scale parameters are expressed in ADC counts.

| Parameter | TR2 (EXP) | TR2 (MC) | RAN (EXP) | RAN (MC) | EN2 (EXP) | EN2 (MC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Vavilov | Vavilov | Vavilov (Bulk) | Vavilov (Bulk) | Crystal Ball | Crystal Ball |

| A | ||||||

| Scale/ | ||||||

| – | – | |||||

| (fixed) | (fixed) | (fixed) | (fixed) | – | – | |

| – | – | – | – | |||

| n | – | – | – | – | ||

Appendix C. Breakdown of the Sources of Systematic Uncertainties

In Table A3 we list the main sources of systematic effects that may affect different stages of the simulation/digitization pipeline, together with the observables that are primarily impacted and the corresponding evaluation/propagation strategy. When available, we also report quantitative estimates derived from dedicated benchmark studies.

Table A3.

Main sources of systematic effects in the Geant4-based simulation/digitization pipeline.

Table A3.

Main sources of systematic effects in the Geant4-based simulation/digitization pipeline.

| Source of Systematic Effect | Stage of the Simulation Chain | Main Impacted Observables | Mitigation Strategy | Quantification from Benchmark Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry: volume placements, material definitions, CAD-to-GDML conversion | Particle transport | Energy deposits, spurious/unphysical energy deposits due to overlaps | Geometry validation (overlap checks) | Not quantified in this work |

| Secondary production range cuts | Particle transport | Energy deposits. Unphysical spatial distribution of energy deposits/secondary production | Scan at different cuts. Adopt cuts smaller than characteristic solid dimensions | Results reported in Figure 4d–f. |

| Physics lists (hadronic models) | Physics modeling at MC-truth level (hadronic interactions) | Energy deposits. Possible differences in the hadronic cross sections adopted | Compare alternative hadronic physics lists on the same benchmark configuration | 228 MeV proton benchmark: MeV, i.e., ∼2–3% of total deposited energy. Results reported in Figure 4a–c and Figure 5. |

| Non-linearity in scintillating counters (light yield quenching) | Digitization (light yield modeling) | Reconstructed energies and variables related to PID | Comparison of different quenching parameterizations (e.g., Birks-Onsager) | Differences up to ∼10% for Z = 4 MIPs (∼1% for MIP protons); up to ∼40% if quenching is neglected for Z ≳ 6 (∼5% for MIP protons). Results are reported in Figure 8. |

| Position-dependent optical response | Digitization (evaluation of the collected photoelectrons) | Reconstructed energy | Use experimental optical maps/parameterizations | Treated in Ref. [53] |

| Parameterization of the photoelectron-to-ADC conversion | Electronics response in digitization | Reconstructed energy. Mismodeling of the electronics nonlinearities | Per-channel response-function fit. Propagate fit-parameter uncertainties in data analyses | Worst case channel systematic uncertainty <10% (conservative estimate, see text) |

References

- De Santis, C.; Ricciarini, S. The High Energy Particle Detector (HEPD-02) for the second China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite (CSES-02). PoS 2021, 395, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, V.; Osteria, G. The High Energy Particle Detector onboard CSES-02 satellite. PoS 2019, 358, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, M.; Laurenza, M.; Benella, S.; Berrilli, F.; Del Moro, D.; Giovannelli, L.; Parmentier, A.; Piersanti, M.; Albrecht, G.; Bartocci, S.; et al. The First Ground-Level Enhancement of Solar Cycle 25 as Seen by the High-Energy Particle Detector (HEPD-01) on Board the CSES-01 Satellite. Space Weather 2023, 21, e2022SW003191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Martucci, M.; Parmentier, A.; Piersanti, M.; Sotgiu, A. The High-Energy Particle Detector (HEPD-01) as a space weather monitoring instrument on board the CSES-01 satellite. PoS 2021, 395, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Sotgiu, A.; Parmentier, A.; Martucci, M.; Piersanti, M.; Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Burger, W.J.; Campana, D.; Carfora, L.; et al. The august 2018 geomagnetic storm observed by the high-energy particle detector on board the CSES-01 satellite. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Benella, S.; Beolè, S.; Burger, W.; Cipollone, P.; Contin, A.; Cristoforetti, M.; De Donato, C.; De Santis, C.; et al. Multispacecraft Observations of Protons and Helium Nuclei in Some Solar Energetic Particle Events toward the Maximum of Cycle 25. Astrophys. J. 2024, 974, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, S.; Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Piergiorgio, P.; Dai, J. The state-of-the-art of the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite mission. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, G.; Bartocci, S.; Basara, L.; Battiston, R.; Burger, W.J.; Carfora, L.; Castellini, G.; Cipollone, P.; Conti, L.; Contin, A.; et al. The HEPD particle detector of the CSES satellite mission for investigating seismo-associated perturbations of the Van Allen belts. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrin, S.Y.; Galper, A.; Grishantzeva, L.; Koldashov, S.; Maslennikov, L.; Murashov, A.; Picozza, P.; Sgrigna, V.; Voronov, S. High-energy charged particle bursts in the near-Earth space as earthquake precursors. In Annales Geophysicae; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2003; Volume 21, pp. 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgrigna, V.; Carota, L.; Conti, L.; Corsi, M.; Galper, A.; Koldashov, S.; Murashov, A.; Picozza, P.; Scrimaglio, R.; Stagni, L. Correlations between earthquakes and anomalous particle bursts from SAMPEX/PET satellite observations. J. Atmos.-Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2005, 67, 1448–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Martucci, M.; Neubüser, C.; Sotgiu, A.; Follega, F.; Ubertini, P.; Bazzano, A.; Rodi, J.; Ammendola, R.; Badoni, D.; et al. Gamma-Ray Burst Observations by the High-Energy Particle Detector on board the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite between 2019 and 2021. Astrophys. J. 2023, 960, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Beolè, S.; Burger, W.; Campana, D.; Cipollone, P.; Contin, A.; Cristoforetti, M.; De Donato, C.; De Santis, C.; et al. The Catalogue of Gamma-Ray Burst Observations by HEPD-01 in the 0.3–50 MeV Energy Range. Astrophys. J. 2024, 976, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picozza, P.; Battiston, R.; Ambrosi, G.; Bartocci, S.; Basara, L.; Burger, W.J.; Campana, D.; Carfora, L.; Casolino, M.; Castellini, G.; et al. Scientific goals and in-orbit performance of the high-energy particle detector on board the CSES. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 243, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciarini, S.; Beolé, S.; de Cilladi, L.; Gebbia, G.; Iuppa, R.; Ricci, E.; Zuccon, P. Enabling low-power MAPS-based space trackers: A sparsified readout based on smart clock gating for the High Energy Particle Detector HEPD-02. In Proceedings of the 37th International Cosmic Ray Conference—PoS (ICRC2021), Berlin, Germany, 12–23 July 2021; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, R.; Gebbia, G.; Iuppa, R.; Zuccon, P.; Ricci, E.; Nozzoli, F. The TDAQ system of the HEPD-02 on the CSES-02 mission. PoS 2023, 444, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barioglio, L.; Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Beolè, S.; Benotto, F.; Bufalino, S.; Cipollone, P.; Coli, S.; Contin, A.; Cristoforetti, M.; et al. The Monolithic Active Pixel Sensors Tracker System of the High Energy Particle Detector aboard the Second Chinese Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2025, 40, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.L.; Shultis, J.K. Monte Carlo methods for design and analysis of radiation detectors. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.a.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. GEANT4—A simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Sala, P.R.; Fasso, A.; Ranft, J. FLUKA: A Multi-Particle Transport Code (Program Version 2005); CERN: Genève, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefmann, K.; Nielsen, K. McStas, a general software package for neutron ray-tracing simulations. Neutron News 1999, 10, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostini, G. A multidimensional unfolding method based on Bayes’ theorem. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 1995, 362, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostini, G. Improved iterative Bayesian unfolding. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1010.0632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.J. Introduction to ISO 10303—the STEP standard for product data exchange. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2001, 1, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytracek, R.; McCormick, J.; Pokorski, W.; Santin, G. Geometry description markup language for physics simulation and analysis applications. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 53, 2892–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.; Gonçalves, P. GUIMesh: A tool to import STEP geometries into Geant4 via GDML. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2019, 239, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, C.M.; Cornelius, I.; Trapp, J.V.; Langton, C.M. Fast Tessellated Solid Navigation in GEANT4. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2012, 59, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Inc. Fusion 360 [Computer Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/products/fusion-360/overview (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Sloan, K.; Hindi, M.; Lei, Z. KeithSloan/GDML: GDML Workbench-June 2024, Version 1.9_Beta; FreeCAD GDML Workbench-AddonManager Installable; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Aso, T.; Bagli, E.; Bagulya, A.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. Recent developments in Geant4. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2016, 835, 186–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Kelsey, M. The geant4 bertini cascade. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2015, 804, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, B.; Gustafson, G.; Nilsson-Almqvist, B. A model for low-pT hadronic reactions with generalizations to hadron-nucleus and nucleus-nucleus collisions. Nucl. Phys. B 1987, 281, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson-Almqvist, B.; Stenlund, E. Interactions between hadrons and nuclei: The Lund Monte Carlo-FRITIOF version 1.6. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1987, 43, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidalov, A. The quark-gluon structure of the pomeron and the rise of inclusive spectra at high energies. Phys. Lett. B 1982, 116, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarba, J. Recent developments and validation of Geant4 hadronic physics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 396, 022060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improvements in the Geant4 hadronic physics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2011, 331, 032002. [CrossRef]

- Incerti, S.; Ivanchenko, V.; Novak, M. Recent progress of Geant4 electromagnetic physics for calorimeter simulation. J. Instrum. 2018, 13, C02054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauf, S.; Kuster, M.; Batič, M.; Bell, Z.W.; Hoffmann, D.H.; Lang, P.M.; Neff, S.; Pia, M.G.; Weidenspointner, G.; Zoglauer, A. Radioactive decays in Geant4. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 2966–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauf, S.; Kuster, M.; Batič, M.; Bell, Z.W.; Hoffmann, D.H.; Lang, P.M.; Neff, S.; Pia, M.G.; Weidenspointner, G.; Zoglauer, A. Validation of Geant4-based radioactive decay simulation. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 2984–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.T.C.; Hai, V.H.; Phuc, N.T.T. Impacts of Geant4 hadronic physics models on secondary particle productions in proton therapy simulations. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 229, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolst, D.; Cirrone, G.A.; Cuttone, G.; Folger, G.; Incerti, S.; Ivanchenko, V.; Koi, T.; Mancusi, D.; Pandola, L.; Romano, F.; et al. Validation of Geant4 fragmentation for heavy ion therapy. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2017, 869, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Folger, G.; Ivanchenko, A.; Ivanchenko, V.; Kossov, M.; Quesada, J.; Schälicke, A.; Uzhinsky, V.; Wenzel, H.; Wright, D.; et al. Validation of Geant4 hadronic generators versus thin target data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2011, 331, 032034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulliez, L.; Jouanne, C.; Dumonteil, E. Improvement of Geant4 Neutron-HP package: From methodology to evaluated nuclear data library. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2022, 1027, 166187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antcheva, I.; Ballintijn, M.; Bellenot, B.; Biskup, M.; Brun, R.; Buncic, N.; Canal, P.; Casadei, D.; Couet, O.; Fine, V.; et al. ROOT—A C++ framework for petabyte data storage, statistical analysis and visualization. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2011, 182, 1384–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, S.; Particle Data Group. Review of particle physics. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Beolè, S.; Benotto, F.; Cipollone, P.; Coli, S.; Contin, A.; Cristoforetti, M.; De Donato, C.; De Santis, C.; et al. TROPix: A parametric tool reproducing the output of the HEPD-02 pixel detector. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2025, 1080, 170756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J.B. The Theory and Practice of Scintillation Counting: International Series of Monographs in Electronics and Instrumentation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriani, O.; Berti, E.; Betti, P.; Bigongiari, G.; Bonechi, L.; Bongi, M.; Bottai, S.; Brogi, P.; Castellini, G.; Checchia, C.; et al. Light yield non-proportionality of inorganic crystals and its effect on cosmic-ray measurements. J. Instrum. 2022, 17, P08014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.A.; Moses, W.W.; Sheets, S.; Ahle, L.; Cherepy, N.J.; Sturm, B.; Dazeley, S.; Bizarri, G.; Choong, W.S. Nonproportionality of scintillator detectors: Theory and experiment. II. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2011, 58, 3392–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.; Hunter, S.; Sturm, B.; Cherepy, N.; Ahle, L.; Sheets, S.; Dazeley, S.; Moses, W.; Bizarri, G. Physics of scintillator nonproportionality. In Hard X-Ray, Gamma-Ray, and Neutron Detector Physics XIII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; Volume 8142, pp. 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lega, A.; Nicolaidis, R.; Nozzoli, F.; Dimiccoli, F.; Follega, F.; Ghezzer, L.; Iuppa, R.; Ricci, E.; Verroi, E.; Zuccon, P. New measurements of light yield quenching in EJ-200 and LYSO scintillators. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2025, 1079, 170612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiccoli, F.; Follega, F.M.; Ghezzer, L.E.; Iuppa, R.; Lega, A.; Nicolaidis, R.; Nozzoli, F.; Ricci, E.; Verroi, E.; Zuccon, P. A New Measurement of Light Yield Quenching in EJ-200 and LYSO Scintillators. Particles 2025, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, V.; CSES-Limadou Collaboration. Trigger and data acquisition system of the High Energy Particle Detector on board the CSES-02 satellite. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2023, 1046, 167741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, S.; Battiston, R.; Beolè, S.; Benotto, F.; Cipollone, P.; Coli, S.; Contin, A.; Cristoforetti, M.; De Donato, C.; De Santis, C.; et al. The Scintillation Counters of the High-Energy Particle Detector of the China Seismo-Electromagnetic (CSES-02) Satellite. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithrick, J.J.; Myers, I.T. Average Triton Energy Deposited in Silicon per Electron-Hole Pair Produced. Phys. Rev. B 1970, 1, 2945–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasino, F.; Rovituso, M.; Fabiano, S.; Piffer, S.; Manea, C.; Lorentini, S.; Lanzone, S.; Wang, Z.; Pasini, M.; Burger, W.J.; et al. Proton beam characterization in the experimental room of the Trento Proton Therapy facility. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2017, 869, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilov, P. Ionization losses of high-energy heavy particles. Sov. Phys. JETP 1957, 5, 749–751. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.