Abstract

Oligodendrocytes (OLs) constitute the main glial population in the central nervous system and are indispensable for the stability and performance of neural networks. Although best known for generating and maintaining myelin to speed impulse conduction, their influence extends further. By modulating myelin in response to activity, supplying metabolic substrates, and engaging in neuroimmune communication, OLs help preserve the structural integrity and plasticity of neuronal circuits. Growing evidence now positions defective OLs as central players in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Experimental work suggests that OL injury can act as an early trigger, fostering amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition and Tau hyperphosphorylation. Conversely, toxic Aβ aggregates and pathological Tau proteins damage OLs, causing myelin breakdown and progressive neurodegeneration that fuels a self-perpetuating cycle. Here, we synthesize current knowledge of OL physiology and its multifaceted contributions to AD pathogenesis, with particular attention to the bidirectional interplay between OL dysfunction and the disease’s core features—Aβ and tau. On this basis, we outline prospective therapeutic avenues to protect or restore oligodendrocyte function in AD.

1. Introduction

Oligodendrocytes (OLs) are the predominant type of glial cell in the central nervous system (CNS), accounting for an estimated 45–75% of all glial cells [1]. Although they are best known for forming and maintaining myelin sheaths that speed up nerve conduction, OLs also provide neurons with essential metabolic support, modulate immune responses, and continue to turn over and integrate into existing circuits in the adult brain [2]. In neurodegenerative diseases, impaired OL function has moved to center stage [3], and its impact on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is particularly pronounced.

AD, the most common neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by senile plaques rich in amyloid-β (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau. These lesions steadily erode neurons and cognition [4]. AD arises from intertwined genetic, environmental, biochemical, and neuroinflammatory factors. While research has long focused on neurons and Aβ/tau deposits, recent studies show that the oligodendrocyte–neuron unit must remain intact to maintain neural network stability [5]. OLs may release Aβ, yet, more importantly, their failure can strip myelin, thereby instigating both Aβ build-up and Tau pathology. Clarifying the role of OLs could therefore open new therapeutic avenues.

In this review, we begin by charting the basic biology of oligodendrocytes: where they come from, how they mature, how well they regenerate, and how they shift with age. Next, we survey their varied physiological roles and then pull together the growing evidence that these cells help drive AD pathogenesis. Finally, we weigh the therapeutic potential of targeting oligodendrocytes and flag the open questions that remain. The goal is to knit the current knowledge into a clear map that can guide new AD treatments.

2. Oligodendrocytes

2.1. The Origin of Oligodendrocytes

Oligodendrocyte (OL) development unfolds through a tightly regulated sequence that relies on defined precursor cells, recruits progenitors from several anatomical loci, and adheres to strict temporal windows. The current consensus holds that oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) account for most new OLs in the adult central nervous system (CNS), although neural stem and progenitor cells can also contribute. OLs arise from both dorsal and ventral territories. Mid-to-late embryogenesis sees the first OL precursors in the ventral ventricular zone (VZ) of the brain and spinal cord, followed by a second wave from the dorsal VZ [6]. From these restricted origins, the cells disperse throughout the CNS before differentiating and wrapping axons. After birth, the forebrain subventricular zone (SVZ) becomes a major source of newly generated OPCs and OLs [7,8]. In the developing human cortex, the outer SVZ adds another layer of generation [9], highlighting species-specific intricacy in OL origins.

2.1.1. Prenatal Oligodendrogenesis

Forebrain OPCs are generated in successive waves that originate from distinct anatomical sites. In humans, the process begins early in gestation—around week 10—and persists into the mid-to-late stages, remaining detectable at least until week 24 [10]. A classical scheme recognizes three sequential waves of oligodendrocyte production. The first appears embryonically, around E12.5, from the medial ganglionic eminence and the anterior entopeduncular area of the ventral forebrain. A second wave then follows from the lateral ganglionic eminence, and a third, postnatal wave is supplied by the SVZ [11,12]. As development progresses, ventrally generated OPCs are gradually supplanted by dorsally derived progenitors. These dorsal cells migrate widely through the cortex and ultimately form the main population of myelinating oligodendrocytes in the adult. The exact contribution and functional significance of this dorsal source remain contentious: some studies argue that human cortical oligodendrocytes arise chiefly from dorsal radial glia [13,14], whereas others report that dorsal precursors differentiate poorly into OLs, implying the involvement of additional generative mechanisms [15].

In the spinal cord, OPC generation similarly exhibits wavelike production and spatial specificity. Early studies suggested that their differentiation was restricted to the ventral ventricular zone (VZ), followed by dorsal migration [16]. Subsequent research confirmed that the dorsal spinal cord also possesses an independent capacity to generate OPCs [17,18]. It is now widely accepted that spinal cord OPCs are also produced in three waves. The majority of OPCs depend on Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling and emerge from the ventral region at E12.5. A second wave, independent of Shh but reliant on signaling pathways involving DBX1, ASCL1, and FGF, originates from the dorsal region around E15.5. The third wave occurs postnatally [19]. Although ventrally derived OPCs predominate and are widely distributed throughout the spinal cord. In contrast, dorsally derived OPCs are confined to the dorsolateral white matter. Studies have shown that in the absence of ventral OPCs, dorsal OPCs retain a robust potential to proliferate, migrate, and effectively myelinate ventral axons [20,21].

2.1.2. Postnatal Oligodendrogenesis

Postnatally, oligodendrogenesis in the CNS constitutes a lifelong, dynamically regulated process. This process not only supplies the cellular source for myelination during brain development but also contributes to myelin maintenance and plasticity in adulthood.

In the postnatal brain, the forebrain SVZ serves as a persistent source of new OPCs [7]. Notably, in humans and other species, the OSVZ serves as a specialized germinal zone, providing an additional source of OPCs for the cerebral cortex via a distinct type of gliogenic intermediate progenitor cell that exhibits mitotic somal translocation [9]. These newly generated OPCs are widely and uniformly distributed throughout both white matter (WM) and gray matter (GM). However, the eventual density of mature oligodendrocytes derived from them shows significant regional heterogeneity, with the highest levels in the WM [22].

The generation of oligodendrocytes after birth follows a dynamic, non-linear trajectory. Rodents exhibit a peak in proliferation within the initial postnatal months. In humans, a critical period for rapid oligodendrocyte expansion and myelination occurs during the first 5–10 years of childhood; subsequently, the rate of generation slows with age, shifting its primary function towards homeostatic maintenance [23,24]. The OPC population is markedly heterogeneous. In terms of proliferative capacity, OPCs can be divided into mitotically active and relatively quiescent subsets. The active subset, which originates early postnatally primarily from the SVZ, persists lifelong. It functions as a “production reservoir” for new oligodendrocytes and exhibits a considerable migratory range [25,26]. In contrast, the quiescent subset is distributed widely throughout the brain parenchyma. Regional differences in OPC behavior are also evident: those in GM differentiate earlier and more rapidly, whereas OPCs in WM maintain higher density and a higher proliferation rate into adulthood, supporting continuous myelination [24,27]. This functional divergence is paralleled by morphological distinctions, with WM OPCs typically elongated and GM OPCs more often radial [28].

Numerous signaling molecules and growth factors precisely regulate oligodendrogenesis in the adult CNS. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling through its receptor PDGFRα is a key mitogenic driver for OPCs. Furthermore, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), neurotrophin-3, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) indirectly modulate this process via pathways such as the PDGF or MAPK signaling cascades [29]. At the molecular level, factors such as the DNA-binding protein inhibitor ID2 promote proliferation when localized to the nucleus and translocate to the cytoplasm upon the initiation of differentiation [30]. In the adult CNS, the primary function of newly generated oligodendrocytes shifts from forming large amounts of new myelin to integrating into existing myelin structures. They participate in the daily remodeling of myelin and replace oligodendrocytes lost to natural turnover, thereby maintaining the structural integrity and functional stability of the myelin sheath [31].

2.2. Oligodendrocyte Differentiation

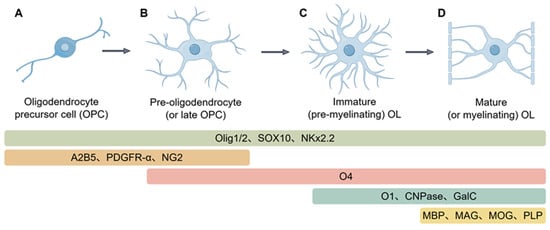

Oligodendrocyte differentiation is a multistep process in which OPCs, under tightly controlled spatiotemporal and molecular cues, change both shape and function to become myelin-forming cells. Neurons and other glia supply a varied set of signaling molecules, transcription factors, and cytokines that keep this progression on track. During CNS myelination, OPCs first activate, divide, and migrate toward target axons. Upon arrival, they exit the cell cycle, initiate a differentiation program, and slowly mature into oligodendrocytes competent to assemble myelin sheaths. The lineage is usually parsed into four sequential stages—OPCs, pre-oligodendrocytes, immature oligodendrocytes, and mature oligodendrocytes—separated by differences in migratory capacity, morphological complexity, and shifting molecular marker profiles, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Lineage progression and molecular markers during oligodendrocyte differentiation. (A), Precursor cells exhibit a bipolar or multipolar shape and are highly migratory. Specific surface antigens, such as PDGFRα, NG2, and A2B5, characterize their identity. Furthermore, key transcriptional regulators such as OLIG2, SOX10, and NKx2.2 are already active at this early stage. (B), At this phase, cells cease proliferation and start developing multiple, branched cellular extensions. The surface sulfatide antigen O4 emerges as a defining marker, while expression levels of PDGFRα, NG2, and NKx2.2 are progressively downregulated; (C), Cells at this stage elaborate an expansive membrane network to establish contact with target axons. They initiate the synthesis of essential myelin proteins—Myelin Basic Protein (MBP), Proteolipid Protein (PLP), Myelin-Associated Glycoprotein (MAG), and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG). This stage also sees the production of the lipids galactocerebroside (GalC) and O1, along with the enzyme 2′,3′-Cyclic-nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase), before the compaction of myelin sheaths. (D), Fully differentiated oligodendrocytes exhibit a complex, highly branched morphology and form multiple internodal myelin segments that tightly enwrap axons. These mature cells maintain robust expression of the major myelin structural proteins MBP, PLP, MAG, and MOG, thereby enabling efficient saltatory nerve conduction. (Images created with Figdraw2.0).

OPCs are progenitor cells distinguished by robust proliferation and migration. Their hallmark is the receptor PDGFRα, which captures PDGF—a principal mitogen and survival signal—to drive division and keep differentiation at bay [32]. These cells also selectively carry the ganglioside A2B5 [33] and the proteoglycan NG2 [34]. A2B5 is not exclusive to OPCs; O-2A progenitors and other precursors also express it [35,36]. NG2′s extracellular domain provides docking sites for integrins and growth factors, such as PDGF-A and FGF, modulating both proliferation and motility [37]. Although shapes differ across brain regions, OPCs are usually stellate, with a small round soma that emits long, highly branched radial processes.

As OPCs commit to differentiation, their cell bodies enlarge and extend numerous short processes, marking their transition into pre-myelinating oligodendrocytes (Pre-OLs). This stage is characterized by the onset of sulfatide expression (as recognized by the O4 antibody) [38] and GPR17 protein [38], concurrent with the progressive loss of A2B5 and NG2 markers. Further maturation leads to the expression of the O1 surface marker [10], galactocerebroside (GalC) [39], and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) [40], defining the immature oligodendrocyte stage. At this point, cells express only the larger CNPase isoform, become postmitotic, and irreversibly commit to the oligodendrocyte lineage [41].

Once oligodendrocytes reach terminal maturity, they send out membranous processes that tightly wrap axons to form compact myelin. This final step is marked by vigorous production of major myelin proteins—myelin basic protein (MBP) [42], proteolipid protein (PLP) [43], myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) [44], and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) [45]. In the mouse CNS, MBP and MAG appear between postnatal days 5 and 7, whereas MOG follows about one to two days later [46]. Mature oligodendrocytes additionally express markers such as MRF/Gm98 [47], zinc finger protein 488 [48], and FABP5 [49].

A core network of transcription factors precisely regulates the entire differentiation process. Olig2, Sox10, and Nkx2.2 are continuously expressed throughout all differentiation stages and serve as key OL lineage markers [50]. Among these, Olig2 is essential for OPC specification and generation—its inactivation leads to oligodendrocyte depletion [51], while its overexpression promotes OPC production [52]. In contrast, Olig1 plays a secondary role, with its deletion causing only mild delays in differentiation [53]. Sox10 serves as the primary determinant for oligodendrocyte terminal differentiation, interacting with proteins such as MYRF to collectively promote complete cellular differentiation and myelin gene expression [54,55]. These factors constitute a sophisticated regulatory network: Olig2 directly induces Sox10 expression [56], while a positive feedback loop between Sox10 and Olig2 maintains their mutual expression [57]. Although Olig2 and Nkx2.2 initially mutually inhibit each other during early development, calcineurin-mediated NFATC2 activation can relieve Olig2-mediated suppression of Sox10/Nkx2.2 while simultaneously mitigating Nkx2.2′s inhibition of Olig2. This enables co-expression of all three factors and ultimately initiates the differentiation program [58].

2.3. Oligodendrocyte Regeneration

Within the adult central nervous system, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) maintain myelin homeostasis and react to injury. Their turnover is usually slow, yet demyelinating lesions rapidly recruit local OPCs, launching a three-stage regenerative program—activation, recruitment, and differentiation—that culminates in new myelin-forming cells [59].

When injury signals arrive, quiescent OPCs switch to an active regenerative mode. Key transcription factors—Olig2, Nkx2.2, MyT1, and Sox2—are promptly upregulated, jointly driving the ensuing repair program [60,61,62]. The cells then expand through asymmetric division, renewing the progenitor pool while yielding differentiated progeny [63]. After expansion, OPCs migrate toward demyelinated areas under tight control: semaphorin 3A restrains recruitment, whereas excess semaphorin 3F promotes it [64].

Their microenvironment profoundly influences OPC regenerative behavior. Growth factors are central regulators: FGF plays a critical role in inhibiting differentiation and promoting recruitment [65]; whereas insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) promotes cell cycle progression [66] and protects OPCs from TNFα-induced damage [67]. Cell–cell interactions are equally crucial. Under physiological conditions, axons suppress OPC differentiation via the Notch signaling pathway; injury-induced disruption of axon-myelin integrity lifts this suppression, creating conditions conducive to differentiation [68]. Furthermore, activated microglia and astrocytes serve as major sources of cytokines that induce rapid OPC proliferation in response to injury [69].

OPCs represent the primary cell type responsible for oligodendrocyte regeneration in the adult brain [70]. Additionally, neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs) in the subventricular zone (SVZ) have also been demonstrated to retain the potential to generate oligodendrocytes following injury [71]. These NSPCs can proliferate and differentiate at an accelerated rate and enhance OPC mobilization and regeneration by secreting factors such as IL-1β and CCL2 [72]. Following telencephalic injury, disruption of Notch signaling can induce quiescent NSPCs to participate in regeneration [73]. SVZ-derived Olig2+ cells can differentiate into highly migratory OPCs that travel along vascular scaffolds to reach the lesion site.

It is noteworthy that OPCs from different regions of the CNS exhibit distinct regenerative capacities. Oligodendrocytes derived from brain and spinal cord OPCs exhibit distinct morphological characteristics [74]. In vitro, cortical and spinal cord-derived OPCs generate myelin sheaths of different lengths, and OPCs from white matter differentiate faster than those from gray matter [75]. The molecular basis for this heterogeneity may involve differences in metabolic pathways; for instance, spinal cord OPCs demonstrate higher levels of cell-autonomous cholesterol biosynthesis, whereas brain oligodendrocytes rely more heavily on extracellular cholesterol uptake [76].

2.4. Oligodendrocyte Senescence

Oligodendrocytes, as post-mitotic long-lived cells, generally maintain high stability in the adult central nervous system [31]. However, with advancing age, both oligodendrocytes and their precursor cells progressively accumulate senescence-associated characteristics, accompanied by concurrent functional decline.

Senescent oligodendrocytes manifest alterations at both molecular and functional levels. In OPCs, senescence is characterized by increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, upregulation of senescence-related genes such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (cdkn2a/p16), and elevated DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and reduced ATP levels [77,78]. Mature oligodendrocytes accumulate DNA damage and exhibit diminished myelination capacity during aging. Transcriptomic analyses further reveal significant downregulation of oligodendrocyte-specific genes (including MBP and LINGO-1) in the aging brain [79]. At the same time, expression profiles of key receptors (such as Gpr17, NMDA, and kainate glutamate receptors) and ion channels (including voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels) undergo substantial modifications [80,81]. These senescent cells also exhibit regional and functional heterogeneity, including variations in calcium signaling and electrical activity [82,83].

Cellular senescence can emerge after extensive replication or be triggered prematurely by stress [84,85,86]. Oligodendrocytes, whose metabolism runs at high speed, are particularly prone to oxidative injury, and this vulnerability drives an age-related accumulation of oxidative DNA damage [87] while engaging canonical senescence routes such as p53/p16 [88]. In disorders like AD, Aβ itself can push OPCs into a senescent state, as evidenced by elevated p21/CDKN1A and p16/CDKN2A proteins, along with increased SA-β-gal activity, highlighting the role of stress-induced senescence in neurodegeneration [89].

As oligodendrocytes age, their regenerative potential wanes and central nervous system homeostasis falters. Older OPCs not only vary more from one region to another but also adopt an inflammatory profile, paralleling their diminished capacity to remyelinate [90,91]. Senescent cells further fuel persistent inflammation and oxidative stress, intensifying neurodegenerative damage [92]. In Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ-driven senescence of OPCs erodes the metabolic and structural support that oligodendrocytes typically provide to neurons, injuring the cells while amplifying neuroinflammation and accelerating cognitive decline [89].

2.5. Oligodendrocyte Functions

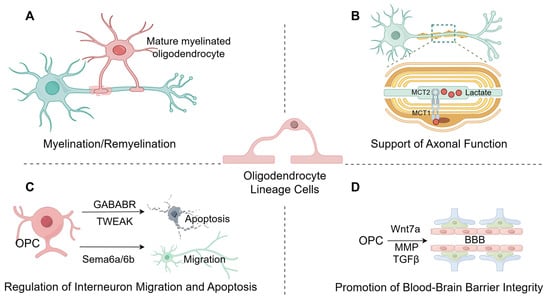

Oligodendrocytes represent a highly specialized glial population in the central nervous system, whose core functions extend well beyond the traditional view of a passive insulating role. Through the formation and maintenance of myelin sheaths, they not only ensure rapid and efficient nerve impulse propagation but also provide vital homeostatic and metabolic support to axons, thereby preserving axonal integrity and conferring protection against injury [93]. Furthermore, via myelin plasticity and lifelong cellular turnover, oligodendrocytes underpin adaptive myelination and the remodeling of neuronal circuits, processes considered fundamental to lifelong learning and memory [94]. Recent research has further elucidated the role of oligodendrocytes as active regulators of neural circuitry: they receive synaptic input from neurons and release neurotrophic factors and neuromodulatory substances, thereby fine-tuning neuronal activity, local microcircuit function, and synaptic plasticity [95]. These principal functions of oligodendrocytes are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The primary function of oligodendrocytes. (A), Myelination and Maintenance: The primary function of oligodendrocytes is to form the myelin sheath, maintain its structural stability, and participate in myelin regeneration. (B), Metabolic Support: Oligodendrocytes provide metabolic support to axons by transferring glycolytic products, such as lactate, to them via monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCT1, MCT2) residing in the myelin sheath and myelinated axons. (C), Neuronal Regulation: Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) participate in neuronal processes by modulating apoptosis via GABAB receptors and TWEAK, and by mediating neuronal migration and positioning through signaling molecules SEMA6A/6B. (D), Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity: Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) contribute to the maintenance of blood–brain barrier integrity via molecular pathways involving Wnt7a, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and TGF-β. (Images created with Figdraw2.0).

2.5.1. Myelination

The myelin sheath is a multilamellar membrane formed by oligodendrocytes that wrap around axons. Its dry mass consists of about 70% lipids and 30% proteins, which assemble into tightly compacted, concentric phospholipid bilayers to provide electrical insulation [96]. A high cholesterol content is critical for myelination. While oligodendrocytes synthesize most of this essential lipid themselves, they are supplemented by astrocytes [97]. Functionally, myelin accelerates action potential propagation through saltatory conduction. It does this by insulating axon segments (internodes) and leaving periodic gaps known as the Nodes of Ranvier. This insulation enables voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels to cluster at the nodes, allowing electrical signals to jump rapidly between them. The proper formation and maintenance of these nodes are therefore essential for channel clustering. Beyond insulation, oligodendrocytes contribute to excitability homeostasis in white matter by expressing potassium channels, such as Kir4.1 [98]. These channels help clear extracellular potassium ions following action potential repolarization. In the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model, impaired Kir4.1 channels in OPCs impede myelin repair in the spinal cord; meanwhile, the small molecule 2-D08 activates Kir4.1 channels, enhances FYN tyrosine kinase phosphorylation to promote OPC differentiation, thereby reducing demyelination and promoting neural recovery [99].

2.5.2. Axonal Support

Oligodendrocytes supply axons with metabolic fuel. Once myelination is complete, the cells rely mainly on aerobic glycolysis, producing lactate or pyruvate that is exported via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) on their membranes and delivered to the axon, a process required to keep the axon intact and functional [100,101]. Neuronal activity tunes this coupling. Axonal glutamate activates NMDA receptors on oligodendrocytes, increasing GLUT1 surface expression and accelerating glucose uptake. Imported glucose is converted to lactate and shuttled to the axon, creating an activity-dependent energy-delivery system [102,103].

2.5.3. Regulation of Interneuron Migration and Apoptosis

OPCs share a developmental origin with specific interneurons and play an instructive role in their distribution. During embryogenesis (around E12.5), the first wave of OPCs guides the proper positioning of interneurons into the cerebral cortex via Sema6a/6b-mediated contact repulsion from blood vessels [104]. Postnatally, OPCs continue to regulate interneuron development. While the majority of the first OPC wave undergoes programmed cell death within the first two postnatal weeks, the survivors preferentially form synaptic connections with interneurons of shared origin [105]. Subsequently, a newly generated third OPC wave, upon activation via their GABAB receptors, releases TWEAK to induce apoptosis in specific interneuron subsets, thereby precisely regulating interneuron density and circuit pruning [106].

2.5.4. Promotion of Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity

Oligodendrocytes and their precursors contribute to the composition and maintenance of the neurovascular unit. During embryogenesis, the first wave of Nkx2.1+ OPCs migrates along and adheres to blood vessels; this physical interaction is essential for normal cerebrovascular development, as conditional ablation of these OPCs significantly reduces vascular density and branching in the embryonic brain [107,108]. OPCs further support vascular function by secreting various factors. They release Wnt7a ligands that promote angiogenesis by activating β-catenin signaling in endothelial cells [109]. Furthermore, elevated Wif1 production by perivascular OPCs impairs BBB integrity by disrupting astrocytic end-feet and endothelial tight junctions, thereby increasing vascular permeability, and triggering CNS inflammation [110]. In vitro, OPC-secreted TGF-β enhances the expression of tight junction proteins in endothelial cells, thereby increasing Blood–Brain Barrier integrity [111]. Additionally, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) secreted by OPCs regulate angiogenesis [112].

2.5.5. Intercellular Communication via Gap Junctions

In addition to the functions described above, oligodendrocytes engage in complex intercellular communication via gap junctions [113]. Gap junctions are specialized channels that permit the direct exchange of ions, metabolites, and signaling molecules between adjacent cells. Their key functions include facilitating the rapid spatial buffering of potassium ions released during neuronal activity—which prevents extracellular accumulation and supports efficient axonal conduction—and acting as conduits for the transfer of energy substrates, such as glucose and lactate, among glial cells, thereby providing metabolic support to axons [113]. In the adult central nervous system, the most characteristic and functionally critical gap junctions are the heterotypic channels formed between connexin 47 (Cx47) on oligodendrocytes and connexin 43 (Cx43) on astrocytes. These oligodendrocyte–astrocyte (O/A) channels are essential for maintaining CNS homeostasis; dysfunction in either connexin protein can lead to myelin damage and may induce neuroinflammation or other neurological disorders [114,115,116]. In contrast, direct oligodendrocyte–oligodendrocyte (O/O) coupling via gap junctions is relatively uncommon in the mature brain. Currently, Cx47 and Cx32 are primarily reported to mediate O/O coupling. Notably, loss-of-function mutations in Cx47 cause Pelizaeus–Merzbacher-like disease, a severe hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. This pathological phenotype can be recapitulated in mice deficient in both Cx47 and Cx32, which also exhibit accompanying immune deficiencies [117]. To date, there is no conclusive evidence for the existence of direct oligodendrocyte-neuron (O/N) gap junctions. Communication between these cell types is primarily mediated by other mechanisms, including metabolic coupling and synaptic-like contacts [98]. There is a growing consensus that the functional integrity of oligodendroglial gap junctions is a contributing factor in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. Abnormal expression of Cx47 and Cx32 has been observed in the 5xFAD mouse model of AD [118,119]. In summary, the role of oligodendroglial gap junctions in myelin dysfunction and neuroinflammation supports their potential link to the pathogenesis of AD, although this field remains underexplored.

3. Oligodendrocytes and AD

AD is a neurodegenerative condition linked to aging, marked clinically by steadily worsening memory, cognitive decline, and shifts in personality and behavior. Its neuropathology centres on two lesions: extracellular senile plaques composed of Aβ deposits and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau [120]. AD arises through multiple pathways, yet most studies have focused on the amyloid cascade and tau hypotheses. The two mechanisms are not separate: rising Aβ can activate kinases that drive tau hyperphosphorylation, thereby promoting paired helical filament assembly and tangle formation [121]. Once formed, tangles impair synapses, exert direct neurotoxicity, and contribute to neuronal dysfunction. Moreover, the extent of Tau hyperphosphorylation parallels the severity of AD pathology [122].

For decades, AD research has centred almost exclusively on neurons. Yet a growing body of work shows that oligodendrocytes—and the myelin they preserve—exert a multifaceted influence on disease progression. These cells shape Aβ generation and clearance, maintain myelin homeostasis, provide metabolic support to neurons, and help regulate inflammatory responses. The sections that follow examine how oligodendrocytes engage with the two hallmark pathologies, Aβ and tau.

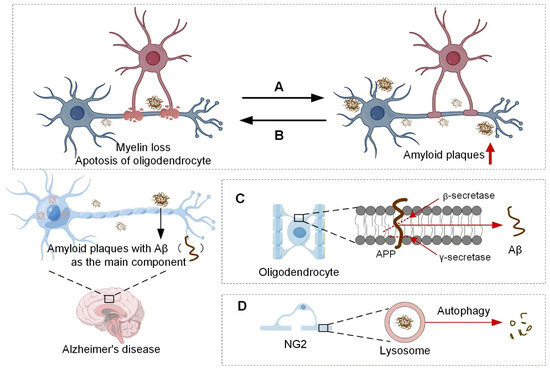

3.1. Oligodendrocytes and Aβ Plaques

Aβ peptide is widely regarded as a key instigator in the pathology of AD. Although neurons have long been considered the leading producers of Aβ, a growing body of research now identifies oligodendrocytes as another significant cellular source. Transcriptomic studies of human AD brain samples [123,124] and AD mouse models [125] show that oligodendrocytes are enriched with mRNA transcripts for the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the enzymes that process it. The ability of oligodendrocytes to generate Aβ has also been confirmed in vitro [126]. More recently, in vivo studies have provided the first direct evidence that oligodendrocytes are an essential source of Aβ in the early stages of AD. The soluble Aβ they release can induce significant impairments in neural circuit function [127]. In AD mouse models, selectively inhibiting Aβ production within oligodendrocytes, or knocking out the β-secretase BACE1 specifically in these cells, leads to a marked improvement in pathology and a restoration of neuronal function. These findings offer direct proof that Aβ derived from oligodendrocytes plays a critical role in disease development [128,129]. On the other hand, cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage, including OPCs, can also clear Aβ peptides via autophagy [130], underscoring their dual role in regulating Aβ levels.

The pathological progression of Aβ is also directly influenced by oligodendrocyte health. Research confirms that myelin breakdown, a consequence of oligodendrocyte dysfunction, acts as an upstream risk factor for Aβ deposition in neurons. In AD models with impaired myelination, phagocytic microglia become preoccupied with clearing abundant myelin debris, thereby diminishing their ability to engulf and clear Aβ plaques, worsening plaque accumulation [131]. Single-cell sequencing has further uncovered a distinct disease-associated oligodendrocyte (DOL) subpopulation. In AD mice, inhibiting the Erk1/2 signaling pathway specifically within these DOLs has been shown to repair myelin damage, alleviate Aβ pathology, and improve cognitive performance [132], suggesting a promising therapeutic strategy targeting oligodendrocytes.

Concurrently, Aβ accumulation exerts potent toxic effects on oligodendrocytes and myelin. Spatial transcriptomic analyses reveal significant disruption of oligodendrocyte and myelin-related gene networks surrounding amyloid plaques [125]. In both sporadic and familial AD patients, focal oligodendrocyte loss shows close association with core Aβ plaques [133]. Excessive Aβ induces oligodendrocyte dysfunction and death through multiple mechanisms, including: (1) enhancement of TNF-α-mediated apoptosis via the neutral sphingomyelinase/ceramide pathway [134]; (2) activation of caspase-3 leading to death of both OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes [135,136]; and (3) direct impairment of OPC capacity for myelin maintenance and regeneration, resulting in white matter degeneration and cumulative axonal damage [137]. These insults collectively contribute to demyelination and cognitive-behavioral deficits.

In summary, oligodendrocytes and Aβ form a complex bidirectional interaction network (Figure 3): oligodendrocytes serve as both a source and a clearance mechanism for Aβ; their functional integrity provides a barrier against Aβ deposition, while they themselves are vulnerable targets of Aβ toxicity. Elucidating this interaction network is crucial for deepening our understanding of AD etiology and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Figure 3.

Oligodendrocytes and Aβ amyloid plaques. (A), Genetically or pharmacologically induced myelin damage leads to increased Aβ deposition. (B), The presence of excessive pathological Aβ exerts neurotoxic effects, resulting in myelin damage. (C), Oligodendrocytes can also produce small amounts of Aβ. (D), Oligodendrocyte precursor cells, known as NG2 cells, have been shown to accumulate around plaques in AD model mice and clear Aβ amyloid peptides through autophagic pathways. The upward-pointing red arrow represents upregulation. (Images created with Figdraw2.0).

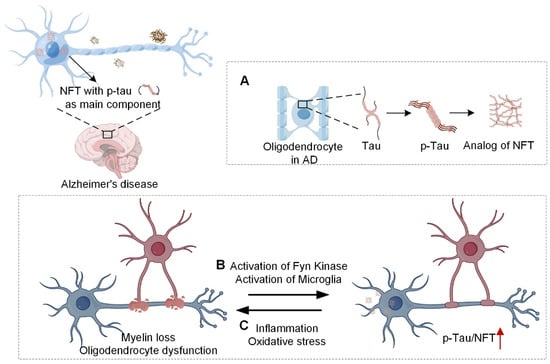

3.2. Oligodendrocytes and Tau Neurofibrillary Tangles

Neurofibrillary tangles, composed of intracellular aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, represent another core pathological hallmark of AD. Although tau pathology primarily occurs within neurons, its relationship with glial cells, particularly oligodendrocytes, is garnering increasing attention [138].

Mature oligodendrocytes constitutively express tau, a protein that stabilizes microtubules and shuttles myelin components within the cell [139]. In AD, glia can accumulate fibrillar tau-positive cytoplasmic tangles that mirror neuronal neurofibrillary tangles [140]. Overexpression and aberrant phosphorylation of tau inside oligodendrocytes are directly toxic, eroding their function and culminating in cell death [141]. Clinicopathological studies show that myelin density decreases as tau-tangle load increases in AD brains [142,143]. One proposed mechanism casts myelin damage itself as an upstream driver of tau pathology: experimentally injuring myelin activates tau-directed kinases, provoking hyperphosphorylation and possibly seeding pathological tau spread [144]. Fyn kinase is pivotal here; it binds microtubule-associated tau and is activated during remyelination, and its inhibition abolishes NFT formation in tauopathy mice, firmly coupling myelin injury to tau aggregation [145]. Myelin alterations can also exacerbate tau pathology indirectly by igniting neuroinflammation. When microglia engulf myelin debris, they adopt a disease-associated profile, accumulate lipid droplets, and drift into senescence [146,147]. These impaired microglia display heightened inflammasome activity, which actively fosters fibrillary tau pathology [148].

Conversely, the inflammatory and oxidative stress environment induced by NFTs may directly cause oligodendrocyte dysfunction [149]. In PS19 mice expressing human mutant tau (P301S), age-related myelin loss is significantly accelerated [150]. Notably, in the 3xTg-AD mouse model, reductions in oligodendrocyte markers and loss of OPC self-renewal capacity precede significant axonal loss, suggesting that oligodendrocyte degeneration may be an early event in tau pathology [135,151]. Furthermore, genetic background and sex significantly modulate Tau-mediated myelin injury. The apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (ApoE4) exacerbates myelin loss in tau transgenic mice, whereas neuron-specific knockout of ApoE4 concurrently alleviates both tau pathology and myelin damage [152]. Recent research further reveals that in an ApoE4 background, a TLR7-dependent interferon response mediates testis-determining factor-associated, sex-specific myelin loss in P301S-tau mice, and targeting TLR7 effectively mitigates demyelination [153].

Oligodendrocytes and tau pathology are locked in a complex, two-way relationship, outlined in Figure 4. Myelin breakdown—possibly triggered by Fyn kinase and inflammatory signaling—can set off and amplify tau pathology. Conversely, misfolded tau and its toxic effects erode oligodendrocyte health and hasten further myelin loss. Clarifying these mutual interactions should provide a fresh theoretical framework for therapies that protect oligodendrocytes and curb tau-driven damage.

Figure 4.

Oligodendrocytes and tau protein neurofibrillary tangles. (A), Mature oligodendrocytes can express tau protein, and fibrillar tangles similar to NFTs may occur within oligodendrocytes in the brains of AD patients; (B), Myelin loss may mediate tau phosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation through the activation of Fyn kinase or microglia; (C), Inflammation and oxidative stress induced by neurofibrillary tangles result in oligodendrocyte dysfunction and myelin loss. The upward-pointing red arrow represents upregulation. (Images created with Figdraw2.0).

4. Potential Applications of Oligodendrocytes in AD Therapeutics

For decades, the Aβ and tau aggregation hypotheses have steered AD research and trial design [154]. Despite massive investment, therapies that blunt Aβ production, boost its clearance, block tau phosphorylation, or break tau aggregates have consistently failed to deliver meaningful clinical benefit in Phase III studies [155,156,157,158]. Lecanemab, an anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody recently granted FDA approval for mild AD, still leaves room for debate over both the magnitude of clinical effect and its long-term safety profile [159]. These setbacks underscore the urgency of looking beyond the canonical Aβ/tau axis and identifying fresh therapeutic targets. Accumulating data now show that oligodendrocytes lose functional competence in the AD brain, and this dysfunction is tightly linked to the disease’s hallmark processes [160]. Consequently, multi-targeted strategies that preserve or restore the oligodendrocyte lineage are gaining traction as a promising new avenue for drug development.

4.1. Antiaging Strategies

Aging is the strongest known risk factor for AD, and oligodendrocytes—particularly oligodendrocyte precursor cells—appear especially susceptible to age-related injury [161]. Transmembrane protein 106B, a regulator of lysosomal and oligodendrocyte function, becomes more abundant in the aging human brain, with the rise most pronounced in individuals carrying the rs1990622-A allele of TMEM106B, a variant associated with elevated AD risk [162]. Targeting aging mechanisms within the oligodendrocyte lineage could therefore offer a route to delay or prevent disease onset. In mouse models of AD, senescent OPCs accumulate around amyloid-β plaques, and their selective elimination reduces AD-related pathology, suggesting a direct therapeutic window [89,163].

Furthermore, rejuvenation strategies represent another extensively investigated therapeutic approach for AD. Studies indicate that the functional decline of aged OPCs is not entirely irreversible; placing them in a youthful microenvironment can significantly restore their function, suggesting that the microenvironment is a critical determinant of cellular aging [164]. Consistent with this, subsequent research confirmed that young cerebrospinal fluid can restore oligodendrocyte function and improve memory in aged mice, mediated by specific signaling molecules such as Fgf17 [165]. Therefore, enhancing the expression of endogenous antiaging genes, such as KLOTHO, has been shown not only to promote OPC maturation and myelination but also to directly attenuate both Aβ and tau pathology, thereby improving cognitive function [166,167,168,169]. Collectively, these findings indicate that rejuvenating OPCs by remodeling the aged microenvironment is a significant direction for AD treatment, providing a solid rationale and a feasible starting point for developing AD therapies targeting oligodendrocyte senescence.

4.2. Strategies for Promoting Differentiation and Proliferation

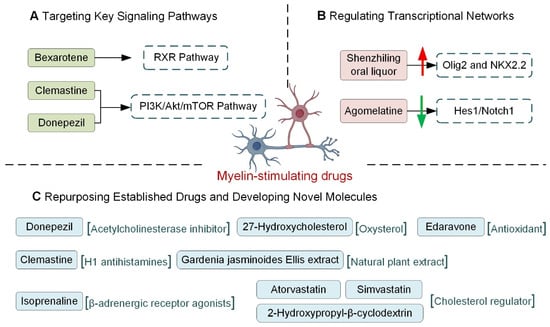

Driving oligodendrocyte precursor cells to divide and mature has become a central tactic for repairing myelin damage in AD. The main directions of this strategy are outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The application of myelin-stimulating drugs in AD. (A), Targeting Key Signaling Pathways: RXR Pathway: Bexarotene, an RXR agonist, promotes OPC maturation and enhances Aβ clearance. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway: Donepezil promotes OPC differentiation, while Clemastine inhibits OPC senescence and promotes differentiation via mTOR downregulation. (B), Regulating Transcriptional Networks: Pro-differentiation Factors: Shenzhiling oral liquor upregulates the expression of key transcription factors Olig2 and NKX2.2, inhibitory Factors: Agomelatine inhibits the Hes1/Notch1 signaling pathway. (C), Repurposing Established Drugs and Developing Novel Molecules: Donepezil, beyond its primary AChEI action, promotes OPC differentiation and myelin repair; Edaravone promotes OPC proliferation; Clemastine increases OPC/OL density. Novel Molecules: Isoprenaline and 27-Hydroxycholesterol promote oligodendrocyte differentiation and maturation; Gardenia jasminoides Ellis extract suppresses neuroinflammation to aid OPC differentiation; Cholesterol modulators (Atorvastatin, Simvastatin, 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin) improve myelination in APOE4 contexts. The upward-pointing red arrow represents upregulation, and the downward-pointing green arrow indicates downregulation. (Images created with Figdraw2.0).

4.2.1. Targeting Key Signaling Pathways

Several signaling cascades reliably drive OPC differentiation, and a subset is now attracting clinical attention. Among them, the RXR axis stands out: once engaged, it raises ABCA1 and ApoE levels, accelerating OPC maturation and myelin formation. At the same time, it helps clear existing Aβ, curbs further peptide production, and dampens inflammation, outcomes that together improve cognition in AD models [170,171,172]. Bexarotene, an FDA-approved RXR agonist initially developed for oncology, has been shown to promote OPC maturation and restore memory performance in AD animals [173]. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR module offers a second lever. Donepezil, widely prescribed as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, also nudges OPCs toward a myelinating phenotype by engaging this route [174]. Likewise, the over-the-counter antihistamine clemastine reinforces myelin and lowers Aβ burden by reducing phosphorylated mTOR, thereby blocking OPC senescence and favoring autophagy and differentiation [175,176].

4.2.2. Regulating Transcriptional Networks

A suite of transcription factors forms the core network regulating oligodendrocyte differentiation, with several key factors demonstrating close links to AD pathology. Among the pro-differentiation factors, Olig2 and NKX2.2 are particularly prominent. Studies show that Olig2 and transcription factor 4 (TCF4) are highly enriched in AD-associated accessible chromatin regions in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice [177]. Pharmacological studies confirm that Shenzhiling oral liquor promotes Aβ42-induced oligodendrocyte differentiation and maturation by specifically upregulating Olig2 and NKX2.2 expression [178]. Beyond Olig2 and NKX2.2, other pro-differentiation factors, such as SOX2, have been identified as key regulators within AD-related gene networks [179]. Notably, increased activity of Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT) has been linked to the amelioration of AD pathology following soluble epoxide hydrolase deletion [180]. Conversely, transcription factors that inhibit differentiation also show dynamic changes in AD. Post-mortem brain analyses from AD patients reveal that the expression of the inhibitory factor Hes1 increases with disease progression, while Hes5 is upregulated in mid-stages but declines in late stages [181]. This supports their potential as therapeutic targets; for instance, the drug agomelatine improves cognitive deficits in mouse models by inhibiting the Hes1/Notch1 signaling pathway [182]. In summary, the transcriptional network governing oligodendrocyte differentiation is significantly implicated in AD pathology. However, current evidence remains largely correlative. Establishing a definitive causal relationship—whether these factors directly influence AD progression by regulating oligodendrocytes—requires further validation through more precise functional experiments.

4.2.3. Epigenetic Regulation via miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) function as precise post-transcriptional regulators of oligodendrocyte development and are emerging as potential therapeutic targets for AD. Research has identified specific miRNAs that critically influence OL differentiation and maturation. A group of miRNAs—including miR-219, miR-138, miR-338, miR-202-3p, the miR-17-92 cluster, miR-23a-5p, miR-146a, miR-204, and miR-203—acts as positive regulators, promoting differentiation. In contrast, others, such as miR-466b-5p, miR-145-5p, miR-124, miR-24, and miR-142-3p, act as negative regulators that inhibit this process [183].

Accumulating data now associate oligodendrocyte-related miRNAs with the central pathological events of AD. miR-138 and miR-146a, for instance, modulate amyloid-β build-up and thereby influence disease trajectory [184,185,186]. In ageing APP/PS1 transgenic mice, elevated miR-138 represses ADAM10, boosts Aβ generation, and produces synaptic and memory dysfunction; conversely, blocking miR-138 alleviates these deficits [186]. Meanwhile, miR-34a thickens myelin by engaging the TAN1/PI3K/AKT/CREB axis, an effect linked to neuroprotection in AD models [184]. These divergent outcomes highlight the cell-type specificity of miRNA activity, a factor that must be weighed when designing therapeutics. Outstanding issues include contradictory findings for specific miRNAs across cell types and disease phases, as well as the need for more rigorous pre-clinical and clinical validation of their specificity and efficacy as drug targets.

4.2.4. Repurposing Established Drugs and Developing Novel Molecules

Several drugs that have been on pharmacy shelves for years now appear to help oligodendrocytes in AD. Donepezil, licensed initially to boost brain acetylcholine, also lifts myelin-basic-protein and GSTπ output in lesion models and can apparently convert non-OPCs into new oligodendrocytes—an unexpected back-door route to remyelination [174,187]. Edaravone, an antioxidant stroke medication, drives OPC division and reduces white-matter damage in the corpus callosum in AD mice starved of blood flow [188]. Clemastine, a first-generation antihistamine, produces a similar picture: more OPCs, more mature oligodendrocytes, and thicker myelin sheaths in transgenic brain tissue [176]. The pipeline is filling up with brand-new candidates as well. Isoprenaline, classically a β-agonist, has been found to trigger OPC differentiation and is now being discussed for AD [189]. The oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol accelerates late-stage OL maturation and, in early mouse work, chips away at memory deficits [190]. An ethanol extract of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis tempers microglial activation, sets OPC differentiation in motion, and limits white-matter injury in AD animals [191]. Even lipid-handling drugs are joining the party: simvastatin and atorvastatin, as well as the cyclodextrin 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, cut cholesterol buildup inside oligodendrocytes, improve myelin thickness, and restore some cognitive readouts in ApoE4-carrying mice [192]. Taken together, the data argue that reinforcing the oligodendrocyte lineage—whether with familiar drugs or newly designed molecules—deserves a front-row seat in future AD therapeutic strategies.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This review systematically traces the entire life course of oligodendrocytes—from birth through maturation to senescence—and rigorously examines how these cells drive AD pathogenesis, while weighing the promise and limits of OL-directed therapies.

We first described how oligodendrocytes are generated: they arise from several early embryonic sources, and after birth, the brain continues to add new ones from the subventricular zone. OPCs then divide, move to target areas, and form myelin, all under tight control by transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic marks. With age, this control weakens—both OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes shift toward a senescent state and lose function, which likely explains why they break down so readily in AD.

Beyond their traditional perception as passive insulators, we have established oligodendrocytes as multifunctional contributors to neural homeostasis. Their physiological responsibilities encompass myelination and myelin maintenance, metabolic support for axons through nutrient coupling, guidance of interneuron development, preservation of blood–brain barrier integrity, and mediation of intercellular communication via gap junctions for ion buffering and metabolic coupling. A growing body of evidence further indicates a role for oligodendrocytes in circadian rhythm and sleep regulation [192]. Previous studies have demonstrated that oligodendrocytes can modulate the sleep–wake balance by regulating genes involved in OPC proliferation and differentiation [193]. In contrast, sleep deprivation has been shown to reduce myelin thickness [194]. In addition, circadian clock genes regulate lipid metabolism by coordinating lipid synthesis, storage, and degradation; disruption of circadian pathways leads to lipid peroxidation and neuroinflammation, both of which are closely associated with AD [195]. Recent reports further reveal a positive correlation between sleep deprivation and the aggregation of Aβ/tau in the brains of AD patients [196,197]. Collectively, these findings underscore the crucial role of oligodendrocytes in regulating the sleep cycle and suggest that dysfunction in this process may exacerbate AD pathogenesis.

Oligodendrocytes in the AD brain undergo a fundamental shift from static supporters to dynamic, dysregulated participants in the disease. Functionally, they transition from a primary focus on myelination and maintenance to adopting a “disease-associated state,” characterized by active engagement in immune regulation and stress responses while concurrently suffering impairment in their crucial myelin-supportive functions. At the pathophysiological level, this shift manifests as cellular senescence, in which oligodendrocytes and their precursor cells, under chronic stress from Aβ and phosphorylated tau, acquire a senescent phenotype. This transforms them from “passive victims” of AD pathology into active drivers of disease progression by compromising myelin integrity and promoting neuroinflammation. Morphologically, these functional and molecular disturbances culminate in focal loss of oligodendrocytes, widespread myelin destruction, and, in some instances, the formation of intracellular tau aggregates. Consequently, the alterations in oligodendrocytes in AD represent not an isolated change in a single characteristic but a cascading dysfunction spanning molecular expression, cellular function, and tissue structure. This redefinition elevates them from a mere concomitant phenomenon of the disease to a central therapeutic target.

A primary focus of this review has been the intricate bidirectional interactions between oligodendrocytes and the core AD pathological proteins, Aβ and tau. Evidence indicates that oligodendrocytes not only represent potential sources of Aβ but, more significantly, that myelin damage resulting from their dysfunction acts as an upstream driver for both Aβ deposition and tau pathology. Conversely, Aβ toxicity and abnormal tau aggregation directly impair oligodendrocytes, leading to cellular death and myelin loss, thereby establishing a self-perpetuating pathological cycle that accelerates disease progression.

Single-cell transcriptomic studies have established that oligodendrocyte lineage cells are active contributors to the AD pathological cascade and have defined their disease-associated molecular states. These studies reveal that oligodendrocytes are significant cellular sources of Aβ, expressing a full complement of amyloidogenic machinery (e.g., APP, BACE1) [128]. Furthermore, specific disease-associated oligodendrocyte subpopulations, such as Mbp+Cd74+ and Serpina3n+C4b+ reactive oligodendrocytes, have been identified in both AD mouse models and human post-mortem brains. Notably, common AD risk variants have been linked to altered gene expression (e.g., CR1) within these oligodendrocyte subpopulations [132,193,194]. The impact of oligodendrocyte dysfunction extends beyond the oligodendrocytes themselves. Single-cell atlases show that myelin damage can push microglia—which are tasked with clearing both myelin debris and Aβ plaques—into a distinct “mixed activation” transcriptional state. This state is associated with phagocytic overload and impaired clearance capacity, thereby indirectly promoting Aβ accumulation [131]. Intriguingly, single-nucleus transcriptomic analyses have also shed light on sex-specific mechanisms, identifying the Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) as a regulator of sex-biased interferon responses to myelin. Pharmacological inhibition of TLR7 was shown to alleviate tau-induced motor deficits and demyelination in male mice [153]. In summary, single-cell data not only reposition oligodendrocytes as active drivers of pathology but also pinpoint specific dysfunctional cellular states, offering novel targets to disrupt the self-perpetuating cycle of degeneration. This refined understanding of oligodendrocyte dysfunction directly informs and motivates the development of novel therapeutic strategies to rescue or protect this crucial cell lineage.

Repeated clinical setbacks of therapies aimed at Aβ and tau have redirected attention to oligodendrocytes as central players in AD pathogenesis. Emerging strategies that engage this lineage fall into three broad streams. The first counters senescence: senescent OPCs clustering around Aβ plaques are cleared, molecules such as Fgf17 or young cerebrospinal fluid are used to rejuvenate the aged milieu, and endogenous longevity genes like KLOTHO are upregulated. Together, these measures enhance remyelination, lower Aβ and tau burdens, and support cognitive recovery. The second stream tackles maturation arrest by driving OPC proliferation and differentiation. Repurposed drugs—including donepezil and clemastine—modulate RXR or PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling; transcription factors that promote differentiation (Olig2, NKX2.2) or repress it (Hes1) are pharmacologically tuned; and epigenetic tools such as miR-219 and miR-138 provide post-transcriptional refinement, although their cell-specific actions still need clarification. The third stream centres on new chemical entities. Isoprenaline, 27-hydroxycholesterol, and Gardenia jasminoides extract have each accelerated OPC differentiation and reduced neuroinflammation in pre-clinical models, while manipulating cholesterol metabolism with statins or cyclodextrins has improved myelination and cognition, especially in ApoE4 carriers.

It is worth noting that oligodendrocytes play an indispensable role in a variety of neurological disorders. In multiple sclerosis (MS), the proliferation, differentiation, and remyelination capacity of OPCs are severely impaired, leading to repair failure; simultaneously, this lineage exhibits aberrant immunomodulatory properties, such as antigen presentation and release of inflammatory factors, indicating that its dysfunction is central to disease progression [195]. In multiple system atrophy (MSA), the pathological hallmark is the formation of intracellular inclusions composed of aggregated α-synuclein within oligodendrocytes, which directly compromise their myelinating and myelin-maintaining functions and trigger neuroinflammation, resulting in widespread loss of neuronal support and axonal integrity [196]. Furthermore, in Parkinson’s disease (PD), genome-wide association studies implicate oligodendrocytes as a significant genetic risk cell type; their transcriptomic alterations emerge early in the disease, suggesting a key role in maintaining substantia nigra microenvironment homeostasis and influencing the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons [197]. In summary, oligodendrocytes assume distinct “pathological roles” across different neurological diseases. Compared to their involvement in AD—primarily interacting with Aβ/tau pathology, dysregulated cholesterol metabolism, and disrupted sleep rhythms—their role in MS is more focused on immune-mediated demyelination and failed regeneration; in MSA, it manifests as unique intracellular protein aggregation pathology; and in PD, it is closely linked to genetic risk and local microenvironment alterations. Nevertheless, the common core across these disorders is that any dysfunction leading to the loss of oligodendrocytes’ support functions—such as myelin maintenance, metabolic support, and immune regulation-ultimately converges on exacerbated neuronal damage and neurodegenerative progression.

Collectively, these data position oligodendrocyte-directed interventions as a credible therapeutic direction for AD. The next wave of studies should first pin down causality—leveraging conditional knockout lines and live imaging—to clarify whether oligodendrocyte failure instigates or merely follows Aβ and tau pathology. This distinction will dictate when and how to intervene. A second priority is to map the whole circuitry of influence around these cells: spatial transcriptomics paired with single-cell metabolomics can expose how oligodendrocytes and their milieu, particularly the microglia encircling amyloid plaques, exchange signals that could be therapeutically intercepted. Third, oligodendrocyte molecular signatures unique to AD—such as ApoE-driven cholesterol imbalance and disease-restricted epigenetic tags—should be catalogued so that treatments can be matched to genotype or clinical subtype. Finally, the field must close the translation gap by advancing promising pre-clinical candidates (senolytics, RXR agonists) into early-phase trials while concomitantly developing peripheral biomarkers that report on myelin health and oligodendrocyte activity, supplying objective tools for early diagnosis, patient stratification, and on-treatment monitoring. Acknowledging oligodendrocytes as central therapeutic targets signals a decisive pivot in AD research; meeting the remaining hurdles could turn this insight into treatments that genuinely change the disease’s trajectory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G., X.Y. and H.Z.; Visualization, S.G.; Writing—original draft, X.Y. and S.G.; Writing—review & editing, S.G. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants: 82271472; the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission: KJQN202500456; the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing: CSTB2022NSCQ-LZX0033; CQMU Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine: W0158; the STI2030-Major Projects: 2021ZD0202400.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is notapplicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Zhang Laboratory members for helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| APP | Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CNPase | 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| DOL | Disease-Associated Oligodendrocyte |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| GalC | Galactocerebroside |

| GM | Gray Matter |

| MAG | Myelin-Associated Glycoprotein |

| MBP | Myelin Basic Protein |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MOG | Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein |

| NFT | Neurofibrillary Tangle |

| OL | Oligodendrocyte |

| OPC | Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cell |

| OSVZ | Outer Subventricular Zone |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PHF | Paired Helical Filament |

| PLP | Proteolipid Protein |

| RXR | Retinoid X Receptor |

| Shh | Sonic Hedgehog |

| SVZ | Subventricular Zone |

| VZ | Ventricular Zone |

| WM | White Matter |

References

- Von Bartheld, C.S.; Bahney, J.; Herculano-Houzel, S. The search for true numbers of neurons and glial cells in the human brain: A review of 150 years of cell counting. J. Comp. Neurol. 2016, 524, 3865–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M.S.; Zdunek, S.; Bergmann, O.; Bernard, S.; Salehpour, M.; Alkass, K.; Perl, S.; Tisdale, J.; Possnert, G.; Brundin, L.; et al. Dynamics of oligodendrocyte generation and myelination in the human brain. Cell 2014, 159, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Czopka, T. Myelination-independent functions of oligodendrocyte precursor cells in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemels, M.T. Neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2016, 539, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, P.; Zong, X. Myelin dysfunction in aging and brain disorders: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallstedt, A.; Klos, J.M.; Ericson, J. Multiple dorsoventral origins of oligodendrocyte generation in the spinal cord and hindbrain. Neuron 2005, 45, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, K.; Fischer, B.; Hurtado-Chong, A.; Draganova, K.; Cantu, C.; Zemke, M.; Sommer, L.; Butt, A.; Raineteau, O. Persistent Wnt/beta-catenin signaling determines dorsalization of the postnatal subventricular zone and neural stem cell specification into oligodendrocytes and glutamatergic neurons. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.D.; Kessaris, N.; Pringle, N. Oligodendrocyte wars. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Bhaduri, A.; Velmeshev, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Rottkamp, C.A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A.; Rowitch, D.H.; Kriegstein, A.R. Origins and Proliferative States of Human Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells. Cell 2020, 182, 594–608.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovcevski, I.; Filipovic, R.; Mo, Z.; Rakic, S.; Zecevic, N. Oligodendrocyte development and the onset of myelination in the human fetal brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2009, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessaris, N.; Fogarty, M.; Iannarelli, P.; Grist, M.; Wegner, M.; Richardson, W.D. Competing waves of oligodendrocytes in the forebrain and postnatal elimination of an embryonic lineage. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Q.; Gao, M.Y.; Gao, R.; Zhao, K.H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Oligodendrocyte lineage cells: Advances in development, disease, and heterogeneity. J. Neurochem. 2023, 164, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bruggen, D.; Pohl, F.; Langseth, C.M.; Kukanja, P.; Lee, H.; Albiach, A.M.; Kabbe, M.; Meijer, M.; Linnarsson, S.; Hilscher, M.M. Developmental landscape of human forebrain at a single-cell level identifies early waves of oligodendrogenesis. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1421–1436.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Xu, R.; Padmashri, R.; Dunaevsky, A.; Liu, Y.; Dreyfus, C.F.; Jiang, P. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cerebral Organoids Reveal Human Oligodendrogenesis with Dorsal and Ventral Origins. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruse, M.; Ishizaki, Y.; Ikenaka, K.; Tanaka, A.; Hitosh, S. Origin of oligodendrocytes in mammalian forebrains: A revised perspective. J. Physiol. Sci. 2017, 67, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warf, B.C.; Fok-Seang, J.; Miller, R.H. Evidence for the ventral origin of oligodendrocyte precursors in the rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 1991, 11, 2477–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, C.R.; Dyer, K.L.; Marchionni, M.; Miller, R.H. Local control of oligodendrocyte development in isolated dorsal mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 59, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Qi, Y.; Hu, X.; Tan, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q. Generation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells from mouse dorsal spinal cord independent of Nkx6 regulation and Shh signaling. Neuron 2005, 45, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowitch, D.H.; Kriegstein, A.R. Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial-cell specification. Nature 2010, 468, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Yu, Q.; Ou, B.; Huang, H.; Yi, M.; Xie, B.; Yang, A.; Qiu, M.; Xu, X. Genetic Evidence that Dorsal Spinal Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells are Capable of Myelinating Ventral Axons Effectively in Mice. Neurosci. Bull. 2020, 36, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.B.; Clarke, L.E.; Burzomato, V.; Kessaris, N.; Anderson, P.N.; Attwell, D.; Richardson, W.D. Dorsally and ventrally derived oligodendrocytes have similar electrical properties but myelinate preferred tracts. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6809–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio-Gomes, B.; Guimaraes, D.M.; Szczupak, D.; Lent, R. The Absolute Number of Oligodendrocytes in the Adult Mouse Brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2018, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimou, L.; Simon, C.; Kirchhoff, F.; Takebayashi, H.; Gotz, M. Progeny of Olig2-expressing progenitors in the gray and white matter of the adult mouse cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 10434–10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.G.; Kang, S.H.; Fukaya, M.; Bergles, D.E. Oligodendrocyte progenitors balance growth with self-repulsion to achieve homeostasis in the adult brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassarro, V.A.; Flagelli, A.; Sannia, M.; Calza, L. Nuclear receptors and differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Vitam. Horm. 2021, 116, 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Menn, B.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Yaschine, C.; Gonzalez-Perez, O.; Rowitch, D.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 7907–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilscher, M.M.; Langseth, C.M.; Kukanja, P.; Yokota, C.; Nilsson, M.; Castelo-Branco, G. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the lineage progression of fine oligodendrocyte subtypes. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.M.; Reynolds, R.; Fawcett, J.W. The oligodendrocyte precursor cell in health and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2001, 24, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Ranjan, S.; Das, S.; Kumari, J.; Singh, S. Role of growth factors and their interplay during oligodendroglial differentiation and maturation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 84, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sdrulla, A.; Johnson, J.E.; Yokota, Y.; Barres, B.A. A role for the helix-loop-helix protein Id2 in the control of oligodendrocyte development. Neuron 2001, 29, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.B.; Jackiewicz, M.; McKenzie, I.A.; Kougioumtzidou, E.; Grist, M.; Richardson, W.D. Remarkable Stability of Myelinating Oligodendrocytes in Mice. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, A.; Shimizu, T.; Sherafat, A.; Richardson, W.D. Life-long oligodendrocyte development and plasticity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 116, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lewis, R.; Miller, R.H. Interactions between oligodendrocyte precursors control the onset of CNS myelination. Dev. Biol. 2011, 350, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.H.; Fukaya, M.; Yang, J.K.; Rothstein, J.D.; Bergles, D.E. NG2+ CNS glial progenitors remain committed to the oligodendrocyte lineage in postnatal life and following neurodegeneration. Neuron 2010, 68, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, M.; Arhin, A.; Gass, D.; Mayer-Pröschel, M. The cortical ancestry of oligodendrocytes: Common principles and novel features. Dev. Neurosci. 2003, 25, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, M.C.; Abney, E.R.; Miller, R.H. Two glial cell lineages diverge prenatally in rat optic nerve. Dev. Biol. 1984, 106, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, J.; Karram, K.; Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells: Properties, progeny and origin. Brain Res. Rev. 2010, 63, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boda, E.; Vigano, F.; Rosa, P.; Fumagalli, M.; Labat-Gest, V.; Tempia, F.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Dimou, L.; Buffo, A. The GPR17 receptor in NG2 expressing cells: Focus on in vivo cell maturation and participation in acute trauma and chronic damage. Glia 2011, 59, 1958–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.P.; Collarini, E.J.; Pringle, N.P.; Richardson, W.D. Embryonic expression of myelin genes: Evidence for a focal source of oligodendrocyte precursors in the ventricular zone of the neural tube. Neuron 1994, 12, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P.E.; Sandillon, F.; Edwards, A.; Matthieu, J.M.; Privat, A. Immunocytochemical localization by electron microscopy of 2′3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase in developing oligodendrocytes of normal and mutant brain. J. Neurosci. 1988, 8, 3057–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.C.; Dorn, H.H.; Kufta, C.V.; Friedman, E.; Dubois-Dalcq, M.E. Pre-oligodendrocytes from adult human CNS. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 1538–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, C.; Lassmann, H.; Waehneldt, T.V.; Matthieu, J.M.; Linington, C. Differential ultrastructural localization of myelin basic protein, myelin/oligodendroglial glycoprotein, and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase in the CNS of adult rats. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, S.; Martinez, S.; Allinquant, B.; Peyron, F.; Puelles, L.; Zalc, B. Oligodendrocytes originate in a restricted zone of the embryonic ventral neural tube defined by DM-20 mRNA expression. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, B.D. Myelin-associated glycoprotein. Location and potential functions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990, 605, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolding, N.J.; Frith, S.; Linington, C.; Morgan, B.P.; Campbell, A.K.; Compston, D.A. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) is a surface marker of oligodendrocyte maturation. J. Neuroimmunol. 1989, 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Dalcq, M.; Behar, T.; Hudson, L.; Lazzarini, R.A. Emergence of three myelin proteins in oligodendrocytes cultured without neurons. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenning, M.; Jackson, S.; Hay, C.M.; Faux, C.; Kilpatrick, T.J.; Willingham, M.; Emery, B. Myelin gene regulatory factor is required for maintenance of myelin and mature oligodendrocyte identity in the adult CNS. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12528–12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Z.; Dulin, J.; Wu, H.; Hurlock, E.; Lee, S.E.; Jansson, K.; Lu, Q.R. An oligodendrocyte-specific zinc-finger transcription regulator cooperates with Olig2 to promote oligodendrocyte differentiation. Development 2006, 133, 3389–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, K.; Ebrahimi, M.; Kagawa, Y.; Islam, A.; Tuerxun, T.; Yasumoto, Y.; Hara, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Miyazaki, H.; Tokuda, N.; et al. Differential expression and regulatory roles of FABP5 and FABP7 in oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 354, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitew, S.; Hay, C.M.; Peckham, H.; Xiao, J.; Koenning, M.; Emery, B. Mechanisms regulating the development of oligodendrocytes and central nervous system myelin. Neuroscience 2014, 276, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Anderson, D.J. The bHLH transcription factors OLIG2 and OLIG1 couple neuronal and glial subtype specification. Cell 2002, 109, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maire, C.L.; Wegener, A.; Kerninon, C. Gain-of-function of Olig transcription factors enhances oligodendrogenesis and myelination. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paes de Faria, J.; Kessaris, N.; Andrew, P.; Richardson, W.D.; Li, H. New Olig1 null mice confirm a non-essential role for Olig1 in oligodendrocyte development. BMC Neurosci. 2014, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornig, J.; Frob, F.; Vogl, M.R.; Hermans-Borgmeyer, I.; Tamm, E.R.; Wegner, M. The transcription factors Sox10 and Myrf define an essential regulatory network module in differentiating oligodendrocytes. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, X.; Cai, J.; Liu, B.; Peng, X.; Wegner, M.; Qiu, M. Induction of oligodendrocyte differentiation by Olig2 and Sox10: Evidence for reciprocal interactions and dosage-dependent mechanisms. Dev. Biol. 2007, 302, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küspert, M.; Hammer, A.; Bösl, M.R.; Wegner, M. Olig2 regulates Sox10 expression in oligodendrocyte precursors through an evolutionary conserved distal enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weider, M.; Wegener, A.; Schmitt, C.; Kuspert, M.; Hillgartner, S.; Bosl, M.R.; Hermans-Borgmeyer, I.; Nait-Oumesmar, B.; Wegner, M. Elevated in vivo levels of a single transcription factor directly convert satellite glia into oligodendrocyte-like cells. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weider, M.; Starost, L.J.; Groll, K.; Kuspert, M.; Sock, E.; Wedel, M.; Frob, F.; Schmitt, C.; Baroti, T.; Hartwig, A.C.; et al. Nfat/calcineurin signaling promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination by transcription factor network tuning. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.J.; Goldman, S.A. Glia Disease and Repair-Remyelination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Sandoval, J.; Swiss, V.A.; Li, J.; Dupree, J.; Franklin, R.J.; Casaccia-Bonnefil, P. Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Hadzic, T.; Nishiyama, A. Transient upregulation of Nkx2.2 expression in oligodendrocyte lineage cells during remyelination. Glia 2004, 46, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancy, S.P.; Zhao, C.; Franklin, R.J. Increased expression of Nkx2.2 and Olig2 identifies reactive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells responding to demyelination in the adult CNS. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2004, 27, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boda, E.; Di Maria, S.; Rosa, P.; Taylor, V.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Buffo, A. Early phenotypic asymmetry of sister oligodendrocyte progenitor cells after mitosis and its modulation by aging and extrinsic factors. Glia 2015, 63, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaton, G.; Aigrot, M.S.; Williams, A.; Moyon, S.; Tepavcevic, V.; Moutkine, I.; Gras, J.; Matho, K.S.; Schmitt, A.; Soellner, H.; et al. Class 3 semaphorins influence oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment and remyelination in adult central nervous system. Brain 2011, 134, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, R.C.; Le, T.Q.; Frost, E.E.; Borke, R.C.; Vana, A.C. Absence of fibroblast growth factor 2 promotes oligodendroglial repopulation of demyelinated white matter. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 8574–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.L.; Xuan, S.; Dragatsis, I.; Efstratiadis, A.; Goldman, J.E. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling through type 1 IGF receptor plays an important role in remyelination. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 7710–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Fan, L.W.; Rhodes, P.G.; Cai, Z. IGF-1 protects oligodendrocyte progenitors against TNFalpha-induced damage by activation of PI3K/Akt and interruption of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Glia 2007, 55, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sdrulla, A.D.; diSibio, G.; Bush, G.; Nofziger, D.; Hicks, C.; Weinmaster, G.; Barres, B.A. Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron 1998, 21, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glezer, I.; Lapointe, A.; Rivest, S. Innate immunity triggers oligodendrocyte progenitor reactivity and confines damages to brain injuries. Faseb J. 2006, 20, 750–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, M.; Rivers, L.E.; Fancy, S.P.; Zhao, C.; Tripathi, R.; Jamen, F.; Young, K.; Goncharevich, A.; Pohl, H.; Rizzi, M.; et al. CNS-resident glial progenitor/stem cells produce Schwann cells as well as oligodendrocytes during repair of CNS demyelination. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]