Abstract

Background/Objectives: Compartmentalized glucose metabolism in the brain contributes to neuro-metabolic stability and shapes hypothalamic control of glucose homeostasis. Glucose transporter-2 (GLUT2) is a plasma membrane glucose sensor that exerts sex-specific control of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and glycogen metabolism. Aging causes counterregulatory dysfunction. Methods: The current research used Western blot and HPLC–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry to investigate whether aging affects the GLUT2-dependent hypothalamic astrocyte metabolic sensor, glycogen enzyme protein expression, and glycogen mass according to sex. Results: The data document GLUT2-dependent upregulated glucokinase (GCK) protein in glucose-deprived old male and female astrocyte cultures, unlike GLUT2 inhibition of this protein in young astrocytes. Glucoprivation of old male and female astrocytes caused GLUT2-independent downregulation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) protein, indicating loss of GLUT2 stimulation of this protein with age. This metabolic stress also caused GLUT2-dependent suppression of phospho-AMPK profiles in each sex, differing from GLUT2-mediated glucoprivic enhancement of activated AMPK in young male astrocytes and phospho-AMPK insensitivity to glucoprivation in young female cultures. GS and GP isoform proteins were refractory to glucoprivation of old male cultures, contrary to downregulation of these proteins in young glucose-deprived male astrocytes. Aging elicited a shift from GLUT2 inhibition to stimulation of male astrocyte glycogen accumulation and caused gain of GLUT2 control of female astrocyte glycogen. Conclusions: The outcomes document sex-specific, aging-related alterations in GLUT2 control of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and ATP monitoring and glycogen mass and metabolism. These results warrant future initiatives to assess how these adjustments in hypothalamic astrocyte function may affect neural operations that are shaped by astrocyte–neuron metabolic partnership.

1. Introduction

The brain operates at the apex of glucose consumption in the body owing to the high energy requirements of vital nerve cell functions, such as transmembrane electrolyte gradient preservation and synaptic discharge. Reductions in systemic glucose concentrations, exemplified by clinical hypoglycemia, pose a risk for neurological dysfunction or damage or demise of vulnerable nerve cell populations. The brain incorporates a dedicated nerve cell network that maintains tight control of body-wide glucose homeostasis [1,2,3]. This neural circuitry encompasses several interconnected structures located in multiple major brain regions, including the hypothalamus; these loci operate as an integrated system to regulate appropriate counteractive autonomic, neuroendocrine, and behavioral motor responses to diminished systemic glucose availability [4,5,6].

Astrocytes are an important structural and functional component of the brain’s cytoarchitecture. Cytoplasmic extensions of these neuroglia encircle brain capillaries, where they come into contact with capillary endothelial cells to create the semi-permeable blood–brain barrier [7,8,9]. Here, astrocytes control the brain’s uptake of glucose and other critical ions and molecules. Astrocytes actively contribute to neuro-metabolic homeostasis [10]. Inside the astrocyte interior, glucose is either diverted to the glycogen reserve or catabolized via glycolysis to generate the oxidizable monocarboxylate L-lactate [11]. Cell type-specific monocarboxylate transporters transfer lactate from astrocytes to neurons to fuel nerve cell mitochondrial energy production [12]. Hypothalamic astrocyte–neuron metabolic coupling influences glucose counterregulatory outflow [13,14].

Glucoregulatory circuit function is shaped by input from chemo-sensors that monitor the cellular supply of glucose or the energy currency ATP. Astrocyte plasma membrane glucose uptake is monitored by glucose transporter-2 (GLUT-2), a major facilitator transporter superfamily SLC2 gene-encoded protein [15,16,17]. GLUT2 is different from other GLUT family proteins as it exhibits low affinity for glucose, e.g., Km = 17 mM, which implies that glucose transport is unreservedly proportionate over a scale of relevant physiological concentrations [18]. This glucose transporter is a critical source of astrocyte input to the glucoregulatory network, as neuroglucopenia-stimulated counterregulatory hormone release is reliant upon GLUT2 function in this distinctive brain cell compartment [19]. Intracellular astrocyte glucose levels are tracked at the rate-limiting initial step of the glycolytic pathway by the unique hexokinase glucokinase/hexokinase IV (GCK), which facilitates phosphate transfer from ATP to glucose to yield glucose-6-phosphate [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Glucokinase regulatory protein (GKRP) governs cytoplasmic GCK glucose binding [27]. In response to diminished cytoplasmic glucose levels, GKRP forms complexes with glucose-free GCKs, which translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to sequester inactive GCKs. GKRP expression is a plausible indicator of brain cell metabolic sensitivity, as GKRP-expressing hindbrain A2 noradrenergic neurons exhibit neurotransmitter biosynthetic enzyme, GCK, and KATP channel sulfonylurea receptor-1 subunit transcriptional reactivity to hypoglycemia, yet these gene profiles are hypoglycemia-insensitive in A2 nerve cells lacking GKRP expression [28].

Cellular ATP content is monitored by the highly sensitive, evolutionary ATP gauge 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is stimulated by phosphorylation at threonine-172 upon reductions in the intracellular AMP/ATP ratio [29,30,31,32,33,34]. AMPK renders the cellular energy balance more positive by initiating operations that facilitate energy production, i.e., lipid oxidation and glucose uptake, while inhibiting activities that utilize energy, such as macromolecule production. AMPK is a heterotrimeric complex of catalytic (alpha) and regulatory (beta, gamma) subunits. AMPK catalytic subunits alpha-1 (PRKAA1/AMPKα1) and alpha-2 (PRKAA2/AMPKα2) are stimulated to an equivalent magnitude when intracellular AMP levels increase [35]. There is ample evidence that GCK and AMPK operate in the hypothalamus to supply vital sensory cues to neural circuitries that control bodily energy and glucose homeostasis [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

VMN astrocyte glycogen metabolism is a crucial metabolic variable that affects counterregulatory endocrine outflow [45]. Astrocyte glycogen is dynamically remodeled during metabolic homeostasis by the passage of glucose through the glycogen shunt and provides needed lactate equivalents when neurological activity is elevated or during hypoglycemia [10]. Glycogen metabolism is governed by antagonistic glycogen synthase (GS) and glycogen phosphorylase (GP) actions, which catalyze glycogen accumulation or disassembly. GP is converted from non-active to active conformation by phosphorylation at Ser-14 and/or allosteric activation by AMP. GP muscle-type (GPmm) and GP brain-type (GPbb) enzyme variants are expressed in the brain [46]. Our studies document the co-presence of these GP isoforms in hypothalamic astrocytes [47]. GPmm and GPbb exhibit significant differences in activation by the above effectors, as phosphorylation causes complete or partial activation of GPmm vs. GPbb, yet AMP more potently activates GPbb relative to GPmm and is required for maximal GPbb Km and function [46]. Reports that GPbb and GPmm, respectively, achieve glucoprivic or noradrenergic stimulation of astrocyte glycogen glycogenolysis [48] support the notion that these variant enzymes may confer physiological stimulus-specific regulation of glycogen mobilization in the brain.

Aging has wide-ranging effects on somatic and homeostatic functions in the body, including neural regulation of metabolism. The elderly face the prospect of a heightened risk of insulin-induced hypoglycemia (IIH)-associated brain injury as counteractive hormone outflow and neurogenic awareness are impaired with age [49,50,51,52,53,54]. There is a pressing need to ascertain the mechanism(s) that elicits aging-related counterregulatory dysfunction. Age-related impairment of astrocyte–nerve metabolic coupling is acknowledged [55], but insight into if and how aging may affect hypothalamic astrocyte glucose handling and glycogen amassment and mobilization in each sex remains limited. Recent studies using young adult rat primary hypothalamic astrocyte cultures show that GLUT2 enacts sex-specific control of hypothalamic astrocyte GCK and total/activated AMPK protein profiles and glycogen amassment [56]. The current research addressed the hypothesis that aging may cause sex-dimorphic adjustments in GLUT2-dependent metabolic sensor function and glycogen metabolism in old rats of one or both sexes during glucose sufficiency and/or deficiency.

2. Materials and Materials

2.1. Primary Astrocyte Cell Cultures

High-purity astrocyte cultures were derived from hypothalamic tissue collected from young adult (2–3 months of age) or old (11–12 months of age) male and female Sprague Dawley albino rats (Rattus norvegicus), as described [57]. Protocols for animal handling and use followed the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, and ARRIVE guidelines and were implemented under approval by the ULM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee [21KPB-01]. Briefly, tissue encompassing the entire hypothalamus was removed from each brain using the following boundaries: the optic chiasm rostral border (anterior); the mammillary bodies’ rostral margin (posterior); the lateral extent of the tuber cinereum (lateral); and the top of the third ventricle (dorsal) [56]. A single-cell suspension was prepared from each tissue block by pipet dissociation in the presence of trypsin. For each astrocyte collection, suspended cells from three hypothalami dissected from animals of the same sex and age were combined in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) high-glucose media (prod. no. 12800-017; ThermoFisherScientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10.0% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and 1.0% penicillin–streptomycin (prod. no. 15140-122; ThermoFisherSci.). Three independent astrocyte collections were carried out for young and old rats of each sex to perform triplicate stand-alone experiments; thus n = 9 old male, n = 9 old female, n = 9 young male, and n = 9 young female rats were used in the current studies. Dissociated cells were incubated (37 °C; 5.0% CO2) in poly-D-lysine (prod. no. A-003-E; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA)-coated T75 culture flasks containing plating media for fourteen days before elimination of microglia and oligodendrocytes [57]. Purified astrocytes were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated culture dishes, with a 1 × 106 cells/100 mm2 cell density, prior to experimentation. Astrocyte culture homogeneity exceeding 95% was verified by analysis of the astrocyte marker protein glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) by immunofluorescence staining and immunoblotting [57] [Supplementary Figure S1].

2.2. Experimental Design

After reaching 70% confluency, astrocyte cultures were incubated for 18 h in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 5.0% charcoal-stripped FBS (prod. no. 12676029; ThermoFisherSci.). Old astrocytes of each sex were exposed (72 h) to high-glucose DMEM media containing Accell™ rat GLUT2 siRNA (prod. no. A-099803-14-0010, 5.0 nM; Horizon Discovery Ltd., Lafayette, CO, USA) or Accell™ control non-targeting pool (scramble; SCR) siRNA (prod. no. D-001910-10-20, 5.0 nM; Horizon Disc.) in siRNA buffer (prod. no. B-002000-UB-100; Horizon Disc.) [56]. This siRNA gene knockdown treatment causes an approximate 50% reduction in target gene product expression [56]. SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated old rat astrocytes were then incubated (8 h) in media containing (5.5 mM; G5.5) or lacking (0 mM; G0) glucose, as described [57]. Cells were then detached and suspended in lysis buffer (2.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10.0% glycerol, 60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8%). Young rat astrocyte control cultures were pretreated with SCR siRNA before incubation with media containing 5.5 mM glucose.

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

Astrocyte cell pellets were centrifuged, sonicated, and heat-denatured before dilution with Laemmli buffer. Sample lysate protein concentrations were analyzed by NanoDrop spectrophotometry (prod. no. ND-ONE-W, ThermoFisherSci.). Sample aliquots of comparable protein content were separated in Bio-Rad Stain Free 10% acrylamide gels (prod. no. 161–0183; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Stain-free imaging technology for total protein quantification was used as a loading control. After UV gel activation, proteins were transblotted to 0.45 μm PVDF-Plus membranes (prod. no. 1212639; Data Support Co., Panorama City, CA, USA) for automated Freedom RockerTM Blotbot® (Next Advance, Inc., Troy, NY, USA) washing and antibody incubation processing. Target proteins were analyzed using triplicate independent astrocyte cultures. Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4, containing 2% bovine serum albumin (prod. no. 9048-46-8; VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) and 0.2% Tween-20 (prod. no. 9005- 64-5; VWR), before incubation with primary antisera against GLUT2 (prod. no. PA5-97263, ThermoFisherSci.; RRID: AB_2809065; 1:1000), AMPKα1/2 (AMPK) (prod. no. 2532S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; RRID: AB-330331; 1:2000), phosphoAMPKα1/2-Thr 172 (pAMPK; prod. no. 2535S; 1:1600; Cell Signal. Technol.; RRID: AB_331250; 1:2000), GCK (prod. no. bs-1796R; Bioss Antibodies, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA; RRID: AB_11095614; 1:1500), GKRP (prod. no. NBP2-03396, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA; 1:1500), GPbb (prod. no. NBP1-32799, Novus Biol.; RRID: AB-2253353; 1:2000), GPmm (prod. no. NBP2-16689; Novus Biol. 1:2000), or GS (prod. no. 3893S; Cell Signal. Technol.; RRID: AB_2279563; 1:2000) [56]. Membranes were next treated with goat anti-rabbit (product number NEF812001EA, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA; 1:4000) or anti-mouse (prod. no. NEF822001EA, PerkinElmer; 1:4000) peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies, then exposed to SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescent substrate (prod. no. 34096; ThermoFishSci.). Target protein optical densities (O.D.) quantified through Western blotting were normalized to total in-lane protein using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System and Image Lab™ 6.0.0 software. An appropriate, intrinsically non-fluorescent trihalo compound in Bio-Rad stain-free gel was photo-activated upon UV exposure, thereby rendering all in-gel proteins fluorescent for the summation of these O.D. measures. The software sums all protein measures in a single lane and relates that to the target protein O.D. in that lane to generate a normalized O.D. value. Precision Plus protein molecular-weight dual-color standards (prod. no. 161-0374; Bio-Rad) were utilized as reference markers in every Western blot analysis.

2.4. Astrocyte LC-MS Glycogen Analysis

Astrocyte glycogen concentrations were measured as reported [58]. D-(+)-Glucose-1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP) was resolved using a Shodex Asahipak NH2P-40 3E column with acetonitrile/10 mM ammonium acetate (75:25 v/v; 0.2 mL/min) as the mobile phase. D-(+)-glucose-PMP ion chromatograms were extracted from the total ion current (TIC) at m/z 510.2 to acquire area-under-the curve data.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

For each sex, mean normalized target protein O.D. data were compared between young vs. old control SCR siRNA/G5.5 treatment groups by a t test. Protein O.D. measures for old male or female rat astrocyte treatment groups were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance and a Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Astrocyte glycogen concentrations were analyzed among young or old astrocyte treatment groups by three-way analysis of variance and a Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Mean differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical differences between paired treatment groups are denoted by the following symbols: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results

Brain glucose metabolism involves multiple cell compartments. Astrocytes engage in uptake, storage, and catabolism of glucose and transfer the oxidizable glycolytic product L-lactate to fuel nerve cell energy production. Hypothalamic astrocyte–neuron metabolic coupling shapes neural control of systemic glucose counterregulation. Aging is associated with counterregulatory dysfunction. Current research used old rat hypothalamic primary astrocyte cultures to address the premise that aging cause sex-dimorphic adjustments in GLUT2-dependent glucose handling and glycogen metabolism in these neuroglia.

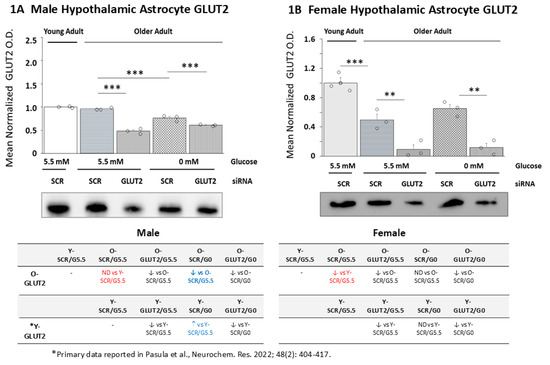

Figure 1 illustrates the effects of GLUT2 gene knockdown on GLUT2 protein expression in old male (Figure 1A) and female (Figure 1B) hypothalamic primary astrocyte cultures. The data in Figure 1A show that mean normalized GLUT2 O.D. values for young (solid white bar) vs. old male (horizontal-striped, white bar) SCR siRNA/G5.5 control astrocyte cultures were equivalent [p = 0.103]. Old female astrocytes (gray horizontal-striped bar) exhibited diminished GLUT2 protein relative to young cell cultures (solid gray bar) (Figure 1B; p < 0.05). Each figure also depicts the effects of GLUT2 gene knockdown [GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5; white (male) and gray (female) horizontal-striped bars], glucose deprivation [SCR siRNA/G0; white (male) and female (gray) cross-hatched bars]; or combinatory GLUT2 siRNA/glucoprivation treatment [GLUT2 siRNA/G0; white (male) and female (gray) vertical-striped bars] on GLUT2 protein in old male and female astrocyte cultures. The results indicate that GLUT2 siRNA administration significantly downregulated GLUT2 protein expression in glucose-supplied or glucose-deprived astrocytes of each sex. Glucose deprivation inhibited GLUT2 expression in old male rat astrocytes (SCR siRNA/G0 vs. SCR siRNA/G5.5) but did not affect this protein profile in old female rat cultures. Images of uncropped Western blots presented in this and subsequent figures are shown in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3. The tables located below Figure 1A (male, at lower left) and Figure 1B (female, at lower right) compare, for each sex, the effects of GLUT2 siRNA or glucoprivation alone or in combination on GLUT2 protein expression in old (rows 1 and 2) vs. young (rows 3 and 4) astrocyte cultures. The outcomes reveal that male astrocytes exhibit a switch in direction of GLUT2 protein response to glucose withdrawal (illustrated in blue font) because of aging.

Figure 1.

Effects of glucose transporter-2 (GLUT2) gene knockdown on old male and female hypothalamic primary astrocyte GLUT2 protein expression. Old male and female rat astrocyte cultures were pretreated with scramble (SCR) or GLUT2 siRNA prior to incubation in 5.5 (G5.5) or 0 (G0) mM glucose-containing media. Young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Astrocyte lysates were analyzed across treatment groups by Western blot for GLUT2 protein content in three independent experiments. Target protein optical density (O.D.) measures acquired in a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System were normalized to total in-lane protein (loading control) using stain-free technology and Bio-Rad Image Lab™ 6.0.0 software. Data depict mean normalized GLUT2 protein O.D. values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) astrocyte treatment groups. In each figure, the solid bar on the left depicts mean GLUT2 O.D. for young adult astrocyte SCR siRNA/G5.5 cultures, whereas old male or female astrocyte treatment groups are illustrated as follows: SCR siRNA/G5.5 (horizontal-striped bars); GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5. (diagonal-striped bars); SCR siRNA/G0 (crosshatched bars); GLUT2 siRNA/G0 (vertical-striped bars). For each sex, mean normalized GLUT O.D. data were compared between young and old SCR siRNA/G5.5 groups by t test and old astrocyte treatment groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test, using GraphPad Prism, Vol. 8 software. Statistical differences between treatment group pairs are indicated by the following symbols: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables below (A,B) summarize the results shown in graphic format; results from prior studies involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment on young adult male or female astrocyte GLUT2 protein expression are presented for comparison [56]. The red font denotes a sex difference in the age effect on the SCR siRNA/G5.5 control group’s GLUT2 protein expression. The blue font indicates an age-related change in the treatment effect on the GLUT protein profiles.

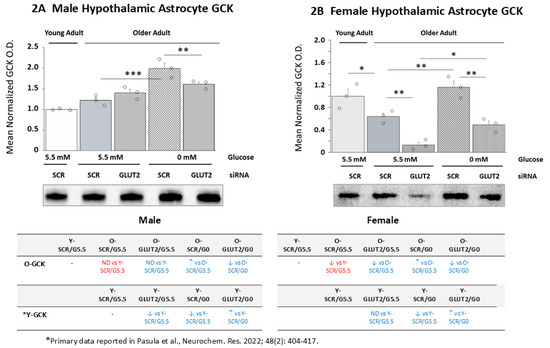

The data in Figure 2 show the effects of GLUT2 siRNA treatment alone or prior to glucose withdrawal on old male (Figure 2A) and female (Figure 2B) hypothalamic primary astrocyte GCK protein expression. The comparison of basal GCK protein profiles between young and old SCR siRNA/G5.5 cultures shows that this protein profile is comparable in young and old male astrocytes [p = 0.065] but that expression was significantly lower in older female than younger female cultures [p < 0.05]. Data show that GLUT2 gene knockdown did not affect old male astrocyte GCK protein expression (Figure 2A) but decreased this protein profile in old female rats (Figure 2B). Incubation in media lacking glucose caused upregulated GCK protein levels in old astrocyte cultures from each sex; this stimulatory response was averted by GLUT2 gene knockdown pretreatment. The table on the lower left indicates that in the males, aging affected GCK protein responses to GLUT2 siRNA, glucoprivation alone, and combinatory GLUT2 siRNA/glucose withdrawal. The table on the lower right shows that astrocyte cultures from old female rats exhibited similar differences in GCK protein expression under those conditions compared to young female animals.

Figure 2.

GLUT2 siRNA effects on glucokinase (GCK) protein expression in old glucose-supplied or glucose-deprived male vs. female hypothalamic primary astrocytes. Old SCR or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated male and female rat astrocyte cultures were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. The data show mean normalized GCK protein O.D. ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) astrocyte treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 3 summarize the treatment effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte culture GCK protein expression; the results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment’s effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The red font denotes a sex difference in the age effect on the SCR siRNA/G5.5 control group’s GCK protein expression. The blue font indicates an age-related change in the treatment effect on the GCK protein profiles.

The effects of GLUT2 gene silencing on GKRP levels in glucose-supplied or glucose-deprived old male (Figure 3A) and female (Figure 3B) astrocytes are presented in Figure 3. The data indicate that baseline GKRP profiles were significantly different between young vs. old animals of each sex [male: p < 0.001; female: p < 0.05]. GLUT2 gene knockdown did not affect basal GKRP levels in old male rats but caused significant reductions in this protein in old female rat cultures. Glucose deprivation caused opposite changes in GKRP levels in old male (upregulated) vs. female (downregulated) astrocyte cultures. GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment did not affect glucoprivation-associated GKRP expression profiles in old male or female astrocytes. The outcomes illustrated in the tables on the lower left (male) and lower right (female) indicate that aged astrocytes of each sex show differences in GLUT2’s regulatory effects on basal and glucoprivic GKRP expression patterns compared to young adult rat cultures. Moreover, old male astrocyte cultures exhibit a gain in GKRP responsiveness to glucose withdrawal.

Figure 3.

Glucokinase regulatory protein (GKRP) protein expression in old male or female hypothalamic primary astrocytes: the effects of GLUT2 gene silencing. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated male and female rat astrocyte cultures were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are presented here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) astrocyte treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 3 summarize the treatments’ effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte GKRP expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The blue font indicates an age-related change in the treatment effect on GKRP profiles.

Figure 4 depicts the effects of GLUT2 gene silencing on old male (Figure 4A) or female (Figure 4B) rat hypothalamic primary astrocyte AMPK protein expression. Young and old SCR siRNA/G5.5-treated astrocytes had equivalent AMPK protein content [p = 0.158], whereas aged female astrocyte cultures had a lower baseline AMPK protein compared to young control cultures [p < 0.05]. GLUT2 siRNA caused significant downregulation of this protein profile in old male (Figure 4A) and female astrocytes. GLUT2 siRNA significantly reduced baseline AMPK protein content in old male and female astrocytes. Incubation in glucose-free media resulted in downregulated AMPK profiles in old male but not female astrocyte cultures. GLUT2 gene knockdown did not affect AMPK expression in glucose-deprived old astrocyte cultures derived from either sex. The tables on the bottom left (male) and bottom right (female) indicate that in each sex, aging causes a loss of GLUT2 control of AMPK protein expression during glucoprivation; moreover, old male rat cultures exhibit a directionally opposite shift in AMPK protein response to glucose deprivation, i.e., from up (young astrocyte) to down (old astrocyte) regulation.

Figure 4.

GLUT2 gene silencing effects on 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) protein expression in old male or female hypothalamic primary astrocytes. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes of each sex were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are depicted here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 4 summarize treatment effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte AMPK protein expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The red font denotes a sex difference in the age effect on the SCR siRNA/G5.5 control group’s AMPK protein expression. The blue font indicates an age-related change in the treatment effect on AMPK protein profiles.

The data in Figure 5 illustrate GLUT2 gene silencing effects on pAMPK protein expression patterns in glucose-supplied vs. glucose-deprived old male (Figure 5A) and female (Figure 5B) hypothalamic primary astrocyte cultures. In each sex, basal pAMPK protein content was significantly decreased in old vs. young astrocyte cultures [male: p < 0.05; female: p < 0.05]. Old male rat astrocyte cultures exhibited no change in pAMPK content after exposure to GLUT2 siRNA, yet female cultures showed downregulated pAMPK expression. Glucose withdrawal caused significant downregulation of pAMPK protein expression in old astrocytes of each sex; this inhibitory response was reversed by GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment in male and female cultures. The table on the bottom left shows that aging in the males shifts the direction of astrocyte pAMPK protein reactivity to glucoprivation from stimulatory to inhibitory and that this negative response is prevented by GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment. The table on the bottom right indicates that GLUT2 regulation of baseline pAMPK protein differs between young (inhibitory) and old (stimulatory) female astrocyte cultures. Aging also causes a gain in female astrocyte pAMPK reactivity to glucoprivation.

Figure 5.

GLUT2 gene silencing effects on phosphorylated AMPK (pAMPK) protein expression in old male or female hypothalamic primary astrocytes. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes of each sex were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are depicted here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 5 summarize the treatments’ effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte pAMPK protein expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The blue font denotes an age-related change in the treatment effect on pAMPK protein profiles.

The effects of GLUT2 gene knockdown on old male (Figure 6A) and female (Figure 6B) primary astrocyte GS protein expression are shown in Figure 6. The data indicate that in each sex baseline GS protein levels were significantly lower in old vs. young SCR siRNA/G5.5 control cultures [male: p < 0.01; female: p < 0.05]. In old male (Figure 6A) and female (Figure 6B) glucose-supplied astrocyte cultures, GLUT2 siRNA increased GS protein expression. Glucoprivation did not affect old male astrocyte GS content but increased this protein profile in old female cultures. GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment had divergent effects on old glucose-deprived male (increased) vs. female (decreased) astrocytes. The table on the bottom left reveals age-related changes in GLUT2 and glucoprivic regulation of basal GS protein expression in old male astrocytes.

Figure 6.

GLUT2 gene silencing effects on glycogen synthase (GS) protein profiles in old male or female hypothalamic primary astrocytes. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes of each sex were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are depicted here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 6 summarize treatments’ effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte GS protein expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The blue font denotes an age-related change in the treatment effect on GS protein profiles.

Figure 7 depicts the effects of GLUT2 gene knockdown on GPbb protein expression patterns in old male (Figure 7A) and female (Figure 7B) primary hypothalamic astrocyte cultures. The data indicate that baseline astrocyte GPbb protein levels were significantly decreased (male; p < 0.001) or increased (female; p < 0.01) because of aging. GLUT2 gene silencing had sex-specific effects on astrocyte GPbb protein expression, i.e., causing up or downregulation in males vs. females, respectively. GLUT2 siRNA treatment in the presence of glucose elevated GPbb protein in old male but not female cultures. Glucoprivation had no impact on this protein profile in old astrocytes of ether sex; nonetheless, GLUT2 gene knockdown caused a reduction in glucoprivic patterns of GPbb protein expression in old male and female astrocytes. The tables on the bottom left (male) and bottom right (female) illustrate age-associated, sex-dependent adjustments in astrocyte GPbb profiles.

Figure 7.

Glycogen phosphorylase brain-type (GPbb) protein expression in old SCR or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated glucose-supplied or glucose-deprived hypothalamic astrocytes. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes of each sex were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are presented here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables on the bottom of Figure 7 summarize the treatments’ effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte GPbb protein expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The red font indicates a sex difference in the age effect on the SCR siRNA/G5.5 control group GPbb protein expression. The blue font denotes an age-related change in the treatment effect on GPbb protein profiles.

The effects of GLUT2 gene silencing on glucoprivic patterns of old male (Figure 8A) and female (Figure 8B) hypothalamic astrocyte GPmm protein expression are depicted in Figure 8. Old male and female cultures exhibited lower (male; p < 0.001) or higher (female; p < 0.001) GPmm protein content compared to young SCR siRNA/G5.5 control astrocytes. GLUT2 siRNA elevated (male) or reduced (female) GPmm protein expression in glucose-supplied astrocytes. Glucose starvation did not affect this protein profile in old astrocytes of either sex; glucoprivic patterns of GPmm protein expression in old female cultures were downregulated by prior exposure to GLUT2 siRNA. The tables on the bottom left and right show that old male astrocytes exhibit changes in GLUT2 and glucoprivic regulation of GPmm protein expression, whereas aging did not alter female astrocyte GPmm protein responses to those stimuli.

Figure 8.

GLUT2 gene knockdown effects on old male or female rat hypothalamic astrocyte glycogen phosphorylase muscle-type (GPmm) protein expression. Old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes of each sex were incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose; young adult male or female SCR siRNA/G5.5 astrocyte cultures served as controls. Normalized target protein measures are presented here as group mean values ± S.E.M. for male (A) and female (B) treatment groups. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment groups are denoted as follows: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The tables at the bottom of Figure 8 summarize the treatments’ effects on old male (at left) or female (at right) astrocyte GPmm protein expression; results from earlier work involving SCR siRNA/G5.5, GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5, SCR siRNA/G0, or GLUT2 siRNA/G0 treatment effects on young adult astrocyte protein profiles are shown for comparison [56]. The red font indicates a sex difference in the age effect on the SCR siRNA/G5.5 control group’s GPmm protein expression. The blue font denotes an age-related change in the treatment effect on GPmm protein profiles.

Figure 9 depicts the outcomes of the LC-ESI-MS analysis of young (Figure 9A; male treatment groups: bars 1–4 on the right, female treatment groups: bars 5–8 on the left) vs. old (Figure 9B; male treatment groups: bars 1–4 on the left, female treatment groups: bars 5–8 on the right) rat astrocyte glycogen concentrations. The data in Figure 9A show that GLUT2 gene silencing upregulated glycogen accumulation in glucose-deprived young male astrocytes (GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5 vs. SCR siRNA G5.5), whereas young female astrocytes were resistant to this treatment. Glucoprivation had the opposite effects on young male (increased) vs. female (decreased) astrocyte glycogen content; GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment elevated glycogen levels in glucose-deprived cultures of either sex.

Figure 9.

GLUT2 gene knockdown effects on young vs. old hypothalamic astrocyte glycogen concentrations. Data in (A,B) depict mean glycogen concentrations for corresponding groups of young or old SCR- or GLUT2 siRNA-pretreated astrocytes incubated in the presence (G5.5) or absence (G0) of glucose. In each figure, bars 1–4 on the left and bars 5–8 on the right depict data for male and female astrocytes organized into the following treatment groups: SCR siRNA/G5.5 [gray (male) or white (female) solid bars], GLUT2 siRNA/G5.5 [gray (male) or white (female) horizontal-striped bars], SCR siRNA/G0 [gray (male) or white (female) diagonal-striped bars], GLUT2 siRNA/G0 [gray (male) or white (female) crosshatched bars]. Astrocyte glycogen content was measured by LC-ESI-MS, expressed relative to cell protein, and analyzed for all treatment groups of each age by three-way ANOVA and the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Statistical differences between treatment group pairs are denoted by the following symbols: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The data in Figure 9B show that glucose-supplied old astrocytes of each sex exhibited downregulated glycogen concentrations in response to GLUT2 gene silencing. Incubation in glucose-free media caused augmentation (male) or diminution (female) of old astrocyte glycogen levels. These divergent sex-specific responses were each reversed by GLUT2 siRNA pretreatment. The outcomes disclose an aging-related shift in the GLUT2 regulation of glycogen accumulation in male hypothalamic astrocytes, i.e., inhibitory (young) to stimulatory (old), and a gain in the GLUT2 control of glycogen levels in glucose-supplied old female cultures.

4. Discussion

Glucogenic energy metabolism in the brain is compartmentalized by cell type, with astrocytes executing critical functions of glucose uptake, storage, and catabolism [10]. Astrocyte–neuron metabolic association impacts hypothalamic control of glucose counterregulation [14]. Aging results in counterregulatory dysfunction [49,50,51,52,53,54], but the effects of this natural process on hypothalamic astrocyte glucose handling are unclear. The membrane glucose transporter/sensor GLUT2 exerts sex-dependent control of astrocyte metabolic sensing and glycogen metabolism in young adult rats [56]. The current research identifies distinctive sex-monomorphic vs. sex-dimorphic changes in baseline and glucoprivic patterns of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and ATP sensor marker protein and glycogen metabolic enzyme protein expression profiles and denotes if and how GLUT2 regulation of these proteins may change with age in each sex. The study outcomes imply that aging may affect critical hypothalamic astrocyte metabolic sensory cues and glycogen energy reserve volume and mobilization, according to sex, which may, in turn, influence astrocyte operations that are critical to neuro-metabolic stability.

Age-associated reductions in female astrocyte culture GLUT2 protein expression presumably correlate with decreased glucose uptake by that specific transporter. Current studies do not shed light on whether concurrent compensatory adjustments in the expression of other GLUT family proteins occur, thus stabilizing net glucose internalization in this sex. An intriguing prospect is that age-associated reductions in GLUT2 protein expression may reflect, in part, a shift toward greater reliance on non-glucogenic vs. glucogenic metabolic substrates for energy production in this sex. This notion is supported by current evidence that baseline expression of the initial and rate-limiting glycolytic pathway enzyme GCK is coincidently downregulated in old female astrocytes. Interestingly, old male astrocytes exhibit decreased GLUT2 protein expression during glucoprivation, which represents an age-associated reversal of response direction. Recent studies document the capability of hypothalamic astrocytes to generate endogenous glucose in vivo via dephosphorylation of glucose-6-phosphate [59]. Regarding the in vitro model used here, it remains to be determined if the paradoxical increase in GLUT2 protein expression observed in glucose-deprived young male astrocytes [56] reflects, in part, increased cellular endogenous glucose production and release in the absence of glucose media. Old male and female astrocytes both exhibit upregulated GCK protein expression during glucoprivation. The prospect of elevated intracellular glucose monitoring and heightened glycolysis in the absence of media glucose implies that these cells may react to this metabolic challenge through increased conversion of non-glucogenic substrates to glucose for partitioning to energy metabolic pathways. Interestingly, the present data show that GLUT2 function is critical for glucoprivic upregulation of GCK profiles in each sex; this stimulatory effect is opposite to GLUT2-mediated inhibition of this protein in glucose-deprived young astrocytes. Old astrocyte GKRP profiles are, respectively, increased (male) or decreased (female) during glucoprivation by GLUT2-independent mechanisms. These responses represent an age-related gain in GKRP response to glucose deficiency (males) alongside loss of GLUT2 control of this protein (both sexes) under those conditions. GKRP forms complexes with glucose-free GCK to isolate non-functional enzymes inside the nucleus. The evidence presented here for up- or downregulated expression of this protein in glucose-deprived old male or female astrocytes, respectively, may be indicative of divergent changes in proportional GCK occupancy by glucose. The lack of GLUT2 control of glucoprivic patterns of GKRP expression in old astrocytes implies that control of GCK molecules available for glucose binding may be governed by intracellular rather than plasma membrane glucose content.

The current results document age-associated adjustments in basal AMPK protein expression in old female but not male hypothalamic astrocytes, yet reveal coincident down-regulation of pAMPK profiles in each sex. The prospect that the mean baseline pAMPK/AMPK expression ratio may be lowered by age in males points to potential enhancement of net cellular energy stability. This presumption will require analytical verification that quantifiable ATP levels are increased in old vs. young astrocyte SCR siRNA/G5.5 treatment groups. Old glucose-deprived male astrocytes exhibit parallel downregulation of AMPK and pAMPK protein profiles, which suggests that the net enzyme activity state may be unaffected by this metabolic stress. On the other hand, glucoprivation did not alter old female astrocyte AMPK expression but decreased pAMPK protein content, implying that cellular energy balance may be relatively more positive compared to old female SCR siRNA/G5.5 controls. The current results also document aging-related loss of GLUT2 control of glucoprivic patterns of AMPK protein expression in each sex, as well as a stimulatory to inhibitory shift in the GLUT2 regulation of pAMPK expression in male astrocytes.

The data illustrate age-associated, downregulated baseline expression of multiple target proteins, including GS, in female hypothalamic astrocytes, yet they show elevated basal GPbb and GPmm protein expression in these cells. On the other hand, each glycogen metabolic enzyme protein profile was relatively lower in old vs. young male astrocyte cultures. Glucoprivation enhanced GS expression in old female but not male astrocytes, representing a loss of response in the latter sex. GLUT2 evidently exerts divergent control of this protein profile in glucose-deprived male (inhibitory) and female (stimulatory) astrocytes regardless of age. Inverse adjustments in baseline GPbb protein expression in old male or female astrocytes vs. young SCR siRNA/G5.5 controls correlate with GLUT2 inhibition or stimulation, respectively; GLUT2 control of basal GPbb levels is thus altered with age. Glucose starvation did not alter GPbb protein expression in old male or female rat astrocytes, indicating a shift from GPbb inhibition in young male cultures. Aging evidently alters GLUT2 control of baseline (both sexes) and glucoprivic-associated (female only) GPbb protein levels. Old astrocytes likewise exhibit GLUT2 suppression (male) or augmentation (female) of basal astrocyte GPmm protein expression and a lack of GPmm protein reactivity to glucose withdrawal. The regulatory effects of GLUT2 or glucoprivation alone or in combination on old male astrocyte GPmm profiles are subject to aging-associated changes.

Aging has a unique and substantial impact on the GLUT2 regulation of hypothalamic astrocyte glycogen concentrations in each sex but does not affect the divergent effects of glucoprivation on glycogen accumulation in the two sexes. In young male astrocytes, this glucose transporter/sensor opposes glycogen expansion irrespective of the presence or absence of glucose, yet old male glucose-supplied or glucose-deprived cultures exhibit GLUT2 augmentation of glycogen mass. These data depict a reversal of direction of control due to aging, implicating GLUT2 as a primary driver of glycogen expansion in glucoprivic male astrocytes while limiting accumulation in young cultures. Thus, this sensor may exert a negative (young) or positive (old) influence on the ratio of glycogen synthesis vs. disassembly in male astrocytes, respectively, thereby curbing or promoting glucose storage. Basal glycogen amassment in old female astrocytes is likewise upregulated by GLUT2, in contrast to a lack of this regulatory control in young female glia. Under glucose sufficiency, old male and female astrocytes may release glucosyl units from the glycogen reserve for glycolytic processing to yield lactate in response to GLUT2.

Glucoprivic amplification of old male astrocyte glycogen content occurs despite GS, GPbb, and GPmm protein insensitivity to this metabolic challenge. This discordance implies that glucose deficiency may exert differential control of total glycogen metabolic enzyme protein production vs. enzyme activity of one or more of those proteins. The current work does reveal if either enzyme is impacted by this metabolic stress. GS is active in the non-phosphorylated state owing to glucose 6-phosphate’s allosteric effects, yet GP enzyme isoforms are activated via phosphorylation or AMP allosteric action; it is unclear if glucoprivation controls these post-transcriptional modifications in either sex. There is an urgent need to distinguish between the effects of GLUT2 or glucoprivic control alone or in combination with the GS, GPmm, and GPbb activation states relative to total protein expression, as these results could yield insights into how these distinctive stimuli may regulate glycogen turnover separate from mass during glucose sufficiency vs. deficiency. It is unclear if astrocyte glycogen is a common substrate for GPbb- vs. GPmm-mediated breakdown, or if it is spatially organized into distinct segments from which glucosyl units are liberated primarily by one GP variant. Further studies are needed to determine if GLUT2 causes comparable or dissimilar changes in GPbb compared to GPmm enzyme activity and to examine how specific activity adjustments for individual GP isoforms may influence total glycogen mass. It is important to remember that efforts to resolve this critical issue are currently thwarted by the non-availability of antibody-based analytical tools for quantification of GP variant phosphorylation.

A point that merits consideration is that the current in vitro metabolic fuel deficiency paradigm is not an exact replication of pathophysiological exogenous insulin-induced reductions in brain tissue glucose levels in vivo that may result from iatrogenic hypoglycemia. Another drawback of the experimental approach used here is the lack of inclusion of step-wise reductions in glucose media. Future research should establish whether old male and female GLUT2 exhibits the ability to detect and act upon small, physiological-like decreases or increases in glucose availability and, additionally, implement that sensory information to impose graded regulatory effects on the expression of the target proteins evaluated here, including those that are resistant to GLUT2 control in the absence of glucose. Recent in vivo studies show that hypothalamic GLUT2 regulates hypoglycemic patterns of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and glycogen metabolic enzyme protein expression and systemic counterregulatory hormone secretion [60]. These findings bolster the need to expand the present efforts by characterizing potential aging effects on in vivo hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and glycogen handling and consequential impacts on astrocyte–nerve cell metabolic coupling in each sex.

Another drawback of the present project involves the use of whole hypothalamic tissue as a source of astrocytes for the primary culture, as averaged measures of glial cell function across this broad region may likely mask the unique responses of local astrocyte populations to adjustments in glucose. In vivo studies allow for the acquisition of brain cell samples at very high neuroanatomical resolution for molecular analyses, a practice that is growing in recognition for diverse structural functions. Accordingly, there is a pressing need for the development of methods for the generation of astrocyte primary cultures from tissue comprising distinct hypothalamic structures of unique significance for neural regulation of glucostasis, i.e., ventromedial, dorsomedial, and arcuate nuclei and the lateral hypothalamic area [1].

A fundamental unanswered question involves the molecular mechanisms by which the GLUT2 membrane may regulate hypothalamic astrocyte glycolytic pathway volume, glycogen turnover and mass, and cellular energy status. The current work raises the issue of how aging may affect those processes. Recent studies have identified sex-specific GLUT2 control of distinctive hypothalamic astrocyte PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway protein expression and/or phosphorylation, and, moreover, they have characterized pathway components affected by glucose shortage and revealed whether these responses involve GLUT2-dependent and/or GLUT2-independent mechanisms [61]. This work importantly implicates glucose status as an important determinant of direction, i.e., positive vs. negative GLUT2 control of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway activity in each sex, and GLUT2 as a driver of distinctive pathway protein reactions to glucoprivation in females but not males. There is a valid necessity to determine if this signal transduction cascade executes documented GLUT control of astrocyte glucose and glycogen metabolism in young animals and, if so, how pathway operation may be affected by age in each sex. An additional consideration is whether GLUT2-controlled PI3K/Akt/mTOR regulatory actions may involve cross-talk mitogen-activated pathway kinase (MAPK) signaling. Our studies disclose that GLUT2 inhibits ERK1/2, p38, and SAPK/JNK MAPK activity in young adult male hypothalamic astrocytes but imposes distinctive stimulatory or inhibitory effects on these individual signaling pathways in female cultures [62]. The results also documented a stimulatory role for GLUT2 in p38 MAPK activation in glucose-starved female astrocytes but indicate that this sensor can act to suppress or trigger SAPK/JNK phosphorylation/activation in glucose-deprived male vs. female glial cells, respectively [63].

Aging is associated with counterregulatory endocrine dysfunction and neurogenic unawareness of hypoglycemia, which exacerbates the risk of neurological impairment or injury [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Insight into how this pathophysiological mal-adaptation occurs is needed to appropriately focus efforts to develop pharmacotherapeutic approaches to mitigate such damage. Studies in young adults show that hypothalamic astrocyte–nerve cell metabolic coupling shapes neural control of counterregulation. The current evidence here for sex-dimorphic age-related changes in hypothalamic astrocyte glucose handling and glycogen amassment and mobilization should be extended by in vivo experimentation to determine, for each sex, if and how these critical astrocyte functions may be affected by age in a whole animal model and to characterize resultant impacts on counterregulation.

In summary, these studies used a hypothalamic primary astrocyte cell culture model in conjunction with Western blot and LC-MS techniques to address the notion that aging may cause sex-dependent changes in GLUT2-controlled metabolic monitoring and glycogen metabolic operations in this glial cell type. Research outcomes show GLUT2-dependent GCK augmentation in glucose-deprived astrocytes of each sex, unlike GLUT2 downregulation of this protein in young astrocytes. Glucose starvation of old male astrocytes caused GLUT2-independent suppression of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), reflective of a loss of GLUT2 upregulation of this protein with age. Glucoprivation caused GLUT2-mediated inhibition of phospho-AMPK profiles in each sex, differing from GLUT2-mediated glucoprivic augmentation of this protein in young male astrocytes and phospho-AMPK insensitivity to glucose starvation in young female cultures. GS and GP isoform proteins were resilient to glucoprivation in old male cultures, contrary to the downregulation of these proteins in young glucose-deprived male astrocytes. Aging elicited a shift from GLUT2 inhibition to stimulation of male astrocyte glycogen accumulation and caused increased GLUT2 control of female astrocyte glycogen. The outcomes document sex-specific, aging-related alterations in GLUT2 control of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and ATP monitoring and glycogen mass and metabolism. The results warrant future initiatives to assess how these adjustments in hypothalamic astrocyte function may affect neural operations that are shaped by astrocyte–neuron metabolic partnership.

5. Conclusions

The present outcomes emphasize the need to focus on potential aging effects on the functionality of astrocyte populations throughout the brain, including neural structures that rely on glycogen mobilization to support critical neurological operations such as memory and learning. There is also a lack of insight into the onset, in males vs. females, of adjustments in astrocyte glucose handling and glycogen metabolism in discrete loci in the hypothalamus and elsewhere and into the molecular mechanisms that elicit such changes. Further research is needed to investigate the prospect that the magnitude of alterations in astrocyte-dependent neuro-metabolic stability may be incremental overall or a segment of the lifespan and may correlate, at a certain point, with impairments in the neural regulation of somatic and autonomic functions, including the maintenance of glucose homeostasis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/neuroglia6040041/s1. Figure S1: Immunofluoresence Staining of Cultured Astrocytes for Astrocyte-Specific Marker Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP); Figure S2: Full-length, uncropped representative Western blots, corresponding to cropped images of immunodetectable young and old male rat hypothalamic primary astrocyte culture target proteins shown in Figure 1A, Figure 2A, Figure 3A, Figure 4A, Figure 5A, Figure 6A, Figure 7A and Figure 8A; Figure S3: Full-length, uncropped representative Western blots, corresponding to cropped images of immunodetectable young and old female rat hypothalamic primary astrocyte culture target proteins shown in Figure 1B, Figure 2B, Figure 3B, Figure 4B, Figure 5B, Figure 6B, Figure 7B, and Figure 8B.

Author Contributions

R.S.: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, validation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization; M.B.P.: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, validation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization; K.P.B.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK-109382.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experimentation was carried out in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, as stated in the submitted manuscript. Study protocols and methods were approved by the ULM Institutional Committee on Animal Care and Use, approval number 24NOV-KPB-01 (approved on 19 November 2021). The sex of the animals used is included, along with a discussion of sex-dependent impacts on the study outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

| AMPK | 5′-AMP-activated protein kinaseα1/2 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| GCK | glucokinase |

| GKRP | glucokinase regulatory protein |

| GLUT2 | glucose transporter-2 |

| GPbb | glycogen phosphorylase-brain type |

| GPmm | glycogen phosphorylase-muscle type |

| GS | glycogen synthase |

| IIH | insulin-induced hypoglycemia |

| LC-ESI-MS | uHPLC-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry |

| pAMPK | phosphoAMPKα1/2 |

References

- Watts, A.G.; Donovan, C.M. Sweet talk in the brain: Glucosensing, neural networks, and hypoglycemic counterregulation. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2010, 31, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, M.; Burdakov, D. Multiple hypothalamic circuits sense and regulate glucose levels. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, R47–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, E.; Song, D.; Kim, M.S. Emerging role of the brain in the homeostatic regulation of energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruud, J.; Steculorum, S.; Brüning, J. Neuronal control of peripheral insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, M.S. Homeostatic regulation of glucose metabolism by the central nervous system. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, Z.; Faber, C.L.; Schwartz, M.W. Central nervous system control of glucose homeostasis: A therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes? Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 62, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.; Dolman, D.E.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslow, L.; Alvarez, J.I. Glial-endothelial crosstalk regulates blood–brain barrier function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 26, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Pivoriūnas, A. Astroglia support, regulate and reinforce brain barriers. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 179, 10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobart, J.L.; Anderson, C.M. Multifunctional role of astrocytes as gatekeepers of neuronal energy supply. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laming, P.R.; Kimelberg, H.; Robinson, S.; Salm, A.; Hawrylak, N.; Müller, C.; Roots, B.; Ng, K. Neuronal-glial interactions and behaviour. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 295–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broer, S.; Rahman, B.; Pellegri, G.; Pellerin, L.; Martin, J.L.; Verleysdonk, S.; Hamprecht, B.; Magistretti, P.J. Comparison of lactate transport in astroglial cells and monocarboxylate transporter (MCT 1) expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes. Expression of two different monocarboxylate transporters in astroglial cells and neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30096–30102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.A.; Borg, W.P.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Brines, M.L.; Shulman, G.I.; Sherwin, R.S. Chronic hypoglycemia and diabetes impair counterregulation induced by localized 2-deoxy-glucose perfusion of the ventromedial hypothalamus in rats. Diabetes 1999, 48, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.C.; Napit, P.R.; Pasula, M.B.; Bheemanapally, K.; Briski, K.P. G-protein-coupled lactate receptor regulation of ventrolateral ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMNvl) glucoregulatory neurotransmitter and 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) expression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2023, 324, R20–R34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, I.S.; Trayhurn, P. Glucose transporters (GLUT and SGLT): Expanded families of sugar transport proteins. Brit. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorens, B.; Mueckler, M. Glucose transporters in the 21st century. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 298, E141–E145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, G.D. Structure, function, and regulation of mammalian glucose transporters of the SLC2 family. Pflügers Archiv Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1155–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueckler, M.; Thorens, B. The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, N.; Dallaporta, M.; Foretz, M.; Emery, M.; Tarussio, D.; Bady, I.; Binnert, C.; Beermann, F.; Thorens, B. Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose transporter type 2 (GLUT2) and astrocyte-dependent glucose sensors. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3543–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschinsky, F.M. Banting Lecture 1995. A lesson in metabolic regulation inspired by the glucokinase glucose sensor paradigm. Diabetes 1996, 45, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuit, F.C.; Huygens, P.; Heimberg, H.; Pipeleers, D.G. Glucose sensing in pancreatic beta-cells: A model for the study of other glucose-regulated cells in gut, pancreas, and hypothalamus. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénicaud, L.; Leloup, C.; Lorsignol, A.; Alquier, T.; Guillod, E. Brain glucose sensing mechanism and glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2002, 5, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez Fernández, E. Molecular aspects of a hypothalamic glucose sensor system and their implications in the control of food intake. An. R. Acad. Nac. Med. 2003, 120, 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, S. A fresh view of glycolysis and glucokinase regulation: History and current status. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 12189–12194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, I.; Hussain, S.S.; Bloom, S.R.; Gardiner, J.V. Insights into the role of neuronal glucokinase. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 311, E42–E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matschinsky, F.M.; Wilson, D.F. The central role of glucokinase in glucose homeostasis; a perspective 50 years after demonstrating the presence of the enzyme in islets of Langerhans. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternisha, S.M.; Miller, B.G. Molecular and cellular regulation of human glucokinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 663, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Alshamrani, A.A.; Briski, K.P. Hindbrain lactate regulation of hypoglycemia-associated patterns of catecholamine and metabolic-sensory biomarker gene expression in A2 noradrenergic neurons innervating the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus in male versus female rat. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2022, 22, 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Carling, D. The AMP-activated protein kinase--fuel gauge of the mammalian cell? Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 246, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Hardie, D.G. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.B.; Alquier, T.; Carling, D.; Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase: Ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, H.G. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: Conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Schaffer, B.E.; Brunet, A. AMPK: An Energy-Sensing Pathway with Multiple Inputs and Outputs. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.; Salt, I.; Scott, J.; Hardie, D.G.; Carling, D. The alpha1 and alpha2 isoforms of the AMP-activated protein kinase have similar activities in rat liver but exhibit differences in substrate specificity in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1996, 397, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leloup, C.; Orosco, M.; Serradas, P.; Nicolaïdis, S.; Pénicaud, L. Specific inhibition of GLUT2 in arcuate nucleus by antisense oligonucleotides suppresses nervous control of insulin secretion. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998, 57, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.M.; Namkoong, C.; Jang, P.G. Hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase mediates counter-regulatory responses to hypoglycaemia in rats. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 2170–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Kahn, B.B. AMPK integrates nutrient and hormonal signals to regulate food intake and energy balance through effects in the hypothalamus and peripheral tissues. J. Physiol. 2006, 574, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrimmon, R.J.; Shaw, M.; Fan, X. Key role for AMP-activated protein kinase in the ventromedial hypothalamus in regulating counterregulatory hormone responses to acute hypoglycemia. Diabetes 2008, 57, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, G.D.; Ropelle, E.R.; Rocha, G.Z. The role of neuronal AMPK as a mediator of nutritional regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Metabolism 2013, 62, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, M.K.; Kinyua, A.W.; Yang, D.J.; Kim, K.W. Hypothalamic AMPK as a regulator of energy homeostasis. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 2754078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.; Nogueiras, R.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Diéguez, C. Hypothalamic AMPK: A canonical regulator of whole-body energy balance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Ratnasabapathy, R.; Izzi-Engbeaya, C.; Nguyen-Tu, M.S.; Richardson, E.; Hussain, S.; DeBacker, I.; Holton, C.; Norton, M.; Carrat, G.; et al. Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus glucokinase regulates insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2246–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cheng, K.K. Hypothalamic AMPK as a Mediator of Hormonal Regulation of Energy Balance. Intl. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Briski, K.P. Glycogen phosphorylase isoform regulation of ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus gluco-regulatory neuron 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase and transmitter marker protein expression. ASN Neuro 2021, 13, 17590914211035020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, O.W.; Fontes, J.D.; Carlson, G.M. The regulation of glycogenolysis in the brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 7099–7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamyani, A.R.; Napit, P.R.; Bheemanapally, K.; Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Sylvester, P.W.; Briski, K.P. Glycogen phosphorylase isoform regulation of glucose and energy sensor expression in male versus female hypothalamic astrocyte primary cultures. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 553, 111698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.S.; Pedersen, S.; Walls, A.B.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; Bak, L.K. Isoform-selective regulation of glycogen phosphorylase by energy deprivation and phosphorylation in astrocytes. Glia 2014, 63, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggeo, M.; Moghetti, P.; Querena, M.; Girotto, S.; Bonora, E.; Crepaldi, G. Effect of aging on growth hormone, ACTH and cortisol response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia in type I diabetes. Acta diabetol. Lat. 1985, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, J.C.; Cryer, P.E.; Clutter, W.E. Attenuated glucose recovery from hypoglycemia in the elderly. Diabetes 1992, 41, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Alonso, F.J.; Galecki, A.; Herman, W.H.; Smith, M.J.; Jacques, J.A.; Halter, J.B. Hypoglycemia counterregulation in elderly humans: Relationship to glucose levels. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1994, 267, E497–E506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, T.T.; Egan, J.M. Diabetes and altered glucose metabolism with aging. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 42, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyani, R.R.; Golden, S.H.; Cefalu, W.T. Diabetes and aging: Unique considerations and goals of care. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, C.W.; Egan, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-related changes in glucose metabolism, hyperglycemia, and cardiovascular risk. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 886–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, C.F.; Ledo, A.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J. Neurovascular-neuroenergetic coupling axis in the brain: Master regulation by nitric oxide and consequences in aging and neurodegeneration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 108, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasula, M.B.; Napit, P.R.; Alhamyani, A.R.; Roy, S.C.; Sylvester, P.W.; Bheemanapally, K.; Briski, K.P. Sex dimorphic glucose transporter-2 regulation of hypothalamic astrocyte glucose and energy sensor expression and glycogen metabolism. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 48, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Bheemanapally, K.; Sylvester, P.W.; Briski, K.P. Sex-specific estrogen regulation of hypothalamic astrocyte estrogen receptor expression and glycogen metabolism in rats. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2020, 504, 110703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheemanapally, K.; Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Briski, K.P. Combinatory high-resolution microdissection/ultra performance liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometry approach for small tissue volume analysis of rat brain glycogen. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 178, 112884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briski, K.P.; Katakam, S.; Sapkota, S.; Pasula, M.B.; Shrestha, R.A.; Yadav, R.K. Astrocyte glucose-6-phosphatase-beta regulates ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus counterregulatory neurotransmission and systemic hormone profiles. Neuropeptides 2025, 111, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.C.; Sapkota, S.; Pasula, M.B.; Briski, K.P. In vivo Glucose transporter-2 regulation of dorsomedial versus ventrolateral VMN astrocyte metabolic sensor and glycogen metabolic enzyme gene expression. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 3367–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasula, M.B.; Sapkota, S.; Sylvester, P.W.; Briski, K.P. Sex dimorphic glucose transporter-2 regulation of hypothalamic primary astrocyte phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2024, 593, 112341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasula, M.B.; Roy, S.C.; Bheemanapally, K.; Sylvester, P.W.; Briski, K.P. Glucose transporter-2 regulation of male versus female hypothalamic astrocyte MAPK expression and activation: Impact of glucose. Neuroglia 2023, 4, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasula, M.B.; Sylvester, P.W.; Briski, K.P. GLUT2 Regulation of p38 MAPK isoform protein expression and p38 phosphorylation in male versus female rat hypothalamic primary astrocyte cultures. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 16, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).