Abstract

The free vibration of stiffened plates analyzed using classical plate–beam theoretical theory (PBM) simplified the vibrations of stiffeners parallel to the plane of the stiffened plate as the first-order torsional vibration of the stiffener cross-section. This simplification introduces errors in both the natural frequencies and mode shapes of the structure for stiffened plates with relatively tall stiffeners. To mitigate the issue previously described, this paper proposes an enhanced plate–beam theoretical model (EPBM). The EBPM decouples stiffener deformation into two components: (1) bending deformation along the transverse direction of the stiffened plate, governed by Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, and (2) transverse deformation of the stiffeners, modeled using thin plate theory. Virtual torsional springs are introduced at the stiffener–plate and stiffener–stiffener interfaces via penalty function method to enforce rotational continuity. These constraints are transformed into energy functionals and integrated into the system’s total energy. Displacement trial functions constructed from Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are solved using the Ritz method. Numerical validation demonstrates that the EBPM significantly improves accuracy over the BPM: errors in free-vibration frequency decrease from 2.42% to 0.63% for the first mode and from 9.79% to 1.34% for the second mode. For constrained vibration, the second-mode error is reduced from 4.22% to 0.03%. This approach provides an effective theoretical framework for the vibration analysis of structures with high stiffeners.

1. Introduction

Stiffened plates offer higher structural stiffness and load-bearing capacity than flat plates of equivalent cross-sectional area, leading to their extensive use in automotive [1,2], marine [3,4], bridge [5,6], and aerospace engineering [7,8,9]. As primary components transmitting static and dynamic loads, the load-bearing capacity and dynamic performance of stiffened plates require thorough investigation, holding significant engineering and theoretical relevance. Wind tunnels commonly employ single-sided stiffened plates as pressure-bearing structures. During operation, the airflow-contacting surface experiences unsteady aerodynamic pressure, which can induce flow-induced vibrations. In theoretical studies of free vibration for stiffened plates, most research decomposes the panel into a base plate and stiffeners. Separate dynamic differential equations are established for each component based on beam–plate theory. The interactions between the base plate and stiffeners are then modeled through interfacial continuity conditions and force equilibrium, leading to the governing equations for the stiffened plate system [5,6,10,11,12]. These governing equations are typically nonlinear high-order differential equations, making analytical solutions difficult to obtain. Consequently, numerical or semi-analytical methods are predominantly employed.

In recent years, scholars have proposed various solution approaches, including the energy method [13,14,15,16,17], finite element method (FEM) [18,19,20], mesh free method [21,22], and isogeometric analysis (IGA) [23,24]. The energy method, one of the most widely adopted analytical techniques, constructs the energy functional of stiffened plates based on principles such as Hamilton’s principle or the Lagrange multiplier method [25,26]. This method facilitates the treatment of boundary and continuity conditions. By employing appropriate mechanical models and energy functionals, it enables the solution of natural vibration problems for complex structures with high accuracy and computational efficiency. Specific applications include: El Yaakoubi-Mesbah et al. [27] partitioned the stiffened plate, introduced artificial springs to ensure segment continuity and diverse boundary conditions, and computed steady-state and transient vibration characteristics via the Rayleigh–Ritz method. Zhang et al. [28] derived analytical solutions for the vibration response of orthogonally stiffened plates using the double finite sine integral transform technique. Gu et al. [29] established a theoretical model for the vibration characteristics of composite stiffened plates based on energy principles and a modified Fourier series method. Liu et al. [30] modeled the stiffened plate as a primary (plate)/secondary (stiffeners) coupled structure. Considering the kinematic compatibility conditions at the plate–beam interface based on First-order Shear Deformation Theory (FSDT), they proposed a unified method for vibration analysis under moving loads along arbitrary paths. Xue et al. [31], based on classical plate and beam theories, separately modeled the strain and kinetic energy of the base plate and stiffeners, investigating the free and forced vibration of exponentially graded functionally graded material (FGM) periodic stiffened plates considering in-plane deformations. Yuan and Jiang [32] developed a theoretical model for multi-panel stiffened structures using a modified variational principle combined with a multi-segment partitioning technique. Stiffeners were treated as discrete elements, and their energy contributions were incorporated into the system’s energy functional via displacement compatibility conditions. Mao et al. [33] established a semi-analytical model based on an extended Chebyshev spectral approach for free vibration analysis of rotating plates containing cracks.

The energy method provides an efficient framework for the transverse vibration analysis of stiffened plates. Existing studies can be categorized into two main types: for general stiffened plates, thin plate theory-based beam–plate models are commonly used; for thick plates or problems involving geometric nonlinearity, higher order plate/shell theories are employed to improve the modeling accuracy of the base plate. However, the description of the stiffener’s own deformation in these methods almost exclusively relies on classical beam theory, whose energy functional accounts only for beam bending and first-order sectional torsion. When applied to wind tunnel stiffened plates with prominent stiffener height and complex cross-sectional deformation, this simplification fails to accurately characterize the complex in-plane and transverse coupled deformation of the stiffener itself, representing a major limitation in current modeling. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a novel approach that can provide a more refined and independent description of high stiffener deformation within an energy variational framework. This inherent limitation becomes pronounced in wind tunnel stiffened plates, where the ratio of the stiffener height to the base plate thickness significantly exceeds that in conventional structures (e.g., rocket casings or ship hulls). Neglecting stiffener transverse vibration in the BPM introduces substantial errors in natural frequencies and mode shapes. Existing research indicates that for typical wind tunnel stiffened panels, the transverse deformation of stiffeners begins to affect the first-order modal response when the height-to-thickness ratio exceeds three, and its influence on the second-order mode becomes non-negligible when the ratio exceeds eight. More critically, as the height-to-thickness ratio increases further, the resulting error in predicted modal frequencies due to neglecting transverse deformation grows substantially.

To accurately capture the transverse vibration characteristics of high-stiffener structures, this study enhances existing beam–plate theoretical modeling by proposing an improved framework that incorporates stiffener transverse deformation, thereby reducing frequency prediction errors.

The proposed enhanced beam–plate model (EBPM) decouples stiffener deformation into two independent components: (1) bending deformation along the base plate’s transverse direction, governed solely by the local plate deflection, and (2) in-plane transverse deformation of the stiffeners, dependent exclusively on their own transverse displacement. Virtual torsion springs are introduced at stiffener–base plate and stiffener–stiffener interfaces via a penalty function method to enforce rotational continuity. These constraints are transformed into energy terms integrated into the system functional. Displacement trial functions constructed from Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are solved using the Ritz method for free vibration analysis. Validation against finite element benchmarks on a representative wind tunnel stiffened plate demonstrates the model’s improved accuracy.

2. Theoretical Formulation

The transverse vibrations of stiffened plates in BPM are decomposed into the deformation of the base plate and the deformation of the stiffeners. The BPM simplifies the stiffeners as beams whose deformations comprise both bending and cross-sectional torsion. The strain energy V and kinetic energy T of the stiffened plate can be expressed as

where , , and denote the strain energy of transverse deformation of the base plate, the bending strain energy of the stiffener, and the torsional strain energy of the stiffener cross-section, respectively. , , and denote the corresponding kinetic energy components. The stiffeners are simplified as beams, for which the deformation displacement functions of beam bending and beam torsion are dependent on the deformation displacement function of the base plate with the relationship given by

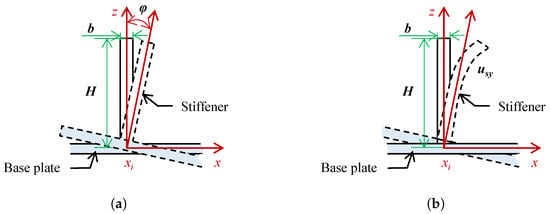

where and represent the bending deflection and cross-sectional twist angle of the stiffener with the neutral axis along the y-direction, respectively, while denotes the transverse deformation displacement function of the base plate. The deformation of the stiffener represented by the cross-sectional twist angle in Equation (2) is illustrated in Figure 1a. It is assumed that the cross-section of the stiffener remains unchanged during torsion (i.e., no relative displacement occurs between points on the cross-section), and the section undergoes rigid rotation about the junction between the stiffener and the base plate.

Figure 1.

Compares the deformation of stiffener panel structures modeled by BPM and EBPM. (a) Simplification of stiffener transverse deformation as beam torsion and its relation via base plate twist in BPM. (b) Schematic of the EBPM approach employing plate/shell theory to model stiffener transverse deformation.

In the EBPM, the stiffener is treated as a plate/shell structure. According to plate/shell theory, its deformation can be decoupled into two primary components: (1) in-plane deformation, primarily consisting of the dominant in-plane bending (corresponding to beam bending in the BPM), along with in-plane stretching/compression, and (2) out-of-plane deformation, mainly comprising out-of-plane bending and twisting. Since the dimensional scale in the thickness direction of the stiffener is much smaller than its length and height, out-of-plane stretching is negligible. The BPM simplifies the stiffener to a beam, approximating out-of-plane twisting only through rigid beam torsion while completely neglecting out-of-plane bending (as illustrated in Figure 1a). However, for stiffened plates with high height-to-thickness ratios, the transverse deformation of the stiffener exhibits significant complexity (as illustrated in Figure 1b), where the out-of-plane bending component becomes crucial. By incorporating plate/shell theory, the EBPM is able to fully describe this previously neglected out-of-plane bending deformation, which constitutes the core physical mechanism for its improved accuracy. The detailed derivation and numerical implementation of the EBPM are presented in the following sections.

2.1. The Enhanced Beam–Plate Theoretical Model (EBPM)

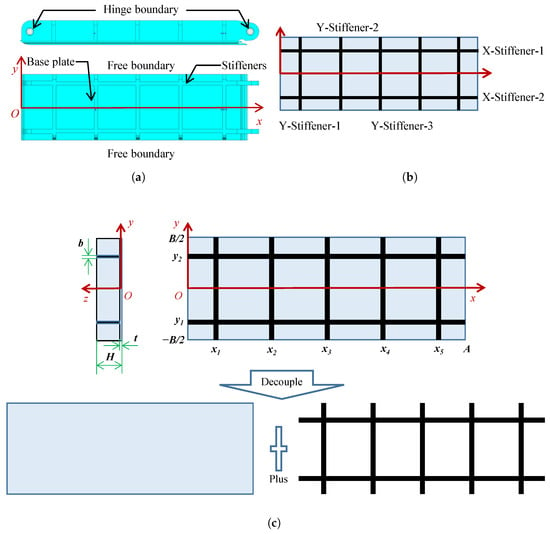

Stiffened plates are widely used in wind tunnels, characterized by a relatively high ratio of stiffener height to base plate thickness. Figure 2a illustrates the typical structure and boundary condition of the wind tunnel stiffened plate. The structure comprises a rectangular base plate with both longitudinal and transverse stiffeners. The base plate is hinged along the x-direction boundaries and free along the y-direction boundaries.

Figure 2.

Structure, boundary condition, stiffener numbering, and modeling of the wind tunnel stiffened plate. (a) Typical structure and boundary condition of the wind tunnel stiffened plate. (b) Stiffener locations with numbering. (c) Theoretical model of rectangular stiffened plate.

In contrast to the BPM approach, which utilizes beam theory to formulate the governing equations for torsional deformation of the stiffener cross-section, the EBPM approach employs plate/shell theory to establish the governing equations for the transverse deformation of the stiffener. Figure 2c presents the theoretical modeling for the wind tunnel stiffened plate vibration: a rectangular base plate of dimensions (Length × Width × Thickness) with multiple eccentrically bonded longitudinal and transverse stiffeners on one side. For analysis, the stiffener at position in the x-direction is selected, as illustrated in Figure 3a, with cross-sectional height H and width b.

Figure 3.

Introducing virtual torsion springs at junctions to enforce rotational continuity via the penalty function method. (a) Virtual torsion springs at base plate–stiffener junctions. (b) Virtual torsion springs at stiffener–stiffener junctions.

In this study, both the base plate and the stiffeners are modeled using the classical thin plate theory based on the Kirchhoff–Love hypothesis. This theory is applicable to components whose thickness is significantly smaller than their other in-plane dimensions and whose deformation satisfies the small-deflection condition (i.e., for linear vibration analysis). For stiffened plates where the stiffener height is large but its web still satisfies the ‘thin’ characteristic (large height-to-thickness ratio but small absolute thickness), this model effectively captures its transverse bending deformation. For analyzing relatively thicker stiffened plates (where the thickness-to-planform dimension ratio is substantial) or vibration scenarios involving large deflections and significant shear effects, the use of thick/moderately thick plate theory (e.g., Mindlin plate theory) is recommended. However, such scenarios are beyond the scope of the present linear free vibration analysis. Under the thin plate assumptions, the strain energy of the stiffener is expressed as

where , , t, , , , and denote the strain energy density, bending rigidity, thickness, cross-sectional area, the x-direction displacement functions, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio of the nth stiffener in the x-direction, respectively.

For harmonic vibration, the kinetic energy of the stiffener is given by

where denotes the material density of the stiffener. Analogous to the x-direction stiffeners, for the mth stiffener in the y-direction with cross-sectional dimensions , the strain energy and kinetic energy are, respectively, given by

The total transverse strain energy and kinetic energy of all stiffeners are given by the summation of corresponding energies from stiffeners in both x- and y-directions, yielding

2.2. Penalty Energy Formulation at Structural Junctions

Deformation governing equations for both the base plate and the stiffeners are established using plate/shell theory. Their displacement functions (base plate–stiffener and stiffener–stiffener) are mutually independent, thus requiring specific measures to establish interconnections between these equations. At stiffener–base plate junctions, rotational continuity is assumed such that the rotation of the stiffener transverse to the base plate equals the rotation of the base plate transverse to the stiffener. This constraint is transformed into an energy functional via the penalty function method [30,34,35], which introduces virtual torsion springs at junctions (Figure 3) to enforce rotational compatibility through spring potential energy. The potential energy of the torsion springs at the junction between the base plate and the nth stiffener in the x-direction is expressed as

where and denote the rotational constraint spring stiffness and potential energy at the junction between the base plate and the nth stiffener in the x-direction, respectively, with and representing the deflection functions of the base plate and the nth x-direction stiffener.

Analogous to the x-direction formulation, the potential energy of the rotational constraint spring at the y-direction mth stiffener–base plate junction is given by

where and represent the rotational constraint spring stiffness and potential energy at the junction between the base plate and the mth y-direction stiffener, respectively, with denoting the deflection functions of the base plate and the mth y-direction stiffener.

The total potential energy of torsion springs at all stiffener-base plate junctions is given by the following summation:

Analogous to the stiffener–base plate junctions, the penalty function method similarly introduces virtual torsion springs at stiffener–stiffener junctions, as illustrated in Figure 3b. These springs enforce rotational compatibility at intersections between longitudinal and transverse stiffeners. The potential energy of the rotational constraint spring at the junction between the nth x-direction stiffener and the mth y-direction stiffener is given by

where and denote the rotational constraint spring stiffness and potential energy at the junction between the nth x-direction stiffener and mth y-direction stiffener, respectively.

The total potential energy of torsion springs at all stiffener–stiffener junctions is given by the following summation:

The total potential energy of torsion springs implementing rotational constraints via the penalty function method is given by

2.3. Computational Implementation

2.3.1. Ritz Method

From the derivation process of the EBPM, it is evident that the torsional strain energy and torsional kinetic energy of the stiffener in Equation (1) are replaced by the transverse deformation strain energy and kinetic energy in Equation (6). Simultaneously, the strain energy of the introduced virtual spring from Equation (12) is added to the system potential energy. Thus, the total potential energy V and kinetic energy T of the stiffened plate based on the EBPM can be expressed as follows:

The free vibration frequencies of the stiffened plate are determined by the energy method. According to the principle of energy conservation, the maximum strain energy (at the extreme displacement position) equals the maximum kinetic energy (at the equilibrium position), expressed as follows:

where and denote the maximum strain energy and maximum kinetic energy of the stiffened plate, respectively.

For the stiffened plate, the mode shape function is assumed as follows:

where represents the displacement function and denotes the natural frequency.

The Ritz method constructs the displacement function as follows:

where represents the kinematically admissible function satisfying boundary conditions, and denotes a set of linearly independent undetermined coefficients. The coefficients are optimized to minimize the energy functional , which yields the following:

Equation (17) constitutes an m-dimensional homogeneous linear system with respect to the coefficient vector . For non-trivial solutions of the displacement function to exist, the determinant of the coefficient matrix must vanish. This yields the characteristic equation containing the frequency parameter :

Solving Equation (18) provides the natural frequencies and back-substitution determines both and the mode shape function w.

2.3.2. Chebyshev Polynomial Trial Functions

In the Ritz method for characterizing deformation displacement fields of plate and beam structures, explicit satisfaction of essential boundary conditions is not required for single- or multi-panel models. High-accuracy numerical solutions can be obtained by constructing displacement trial functions with linearly independent and complete basis functions, significantly streamlining the solution process. This study employs Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind as basis functions [36,37,38], defined by the recurrence relation:

where .

As Chebyshev polynomials constitute an orthogonal function sequence defined on , coordinate transformation is required to preserve orthogonality within the physical plate domain. The coordinate mapping is given by

where denotes the in-plane dimension along the x-direction of the plate.

The displacement trial function for the base plate is constructed as

where denotes the undetermined coefficients, and represent the boundary functions along the x- and y-directions of the base plate, respectively, and and are the i-th and j-th order Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind.

The displacement trial function for the r-th stiffener is constructed as

where denotes the undetermined coefficients, and represent the boundary functions of the stiffener along x- and y-directions, respectively, and and are the ith-order and jth-order Chebyshev polynomials.

The wind tunnel stiffened plate has simply-supported (S) boundaries in the x-direction and free (F) boundaries in the y-direction during operational conditions. To enforce displacement boundary conditions in the trial functions, the boundary function for free edges was set to a constant value of one, while the function for simply-supported edges along the x- and y-directions were and , respectively.

By substituting the base plate’s and stiffeners’s displacement trial functions from Equations (21) and (22) into the stiffened plate energy functional defined in Equation (17), it follows that

where K and M denote the stiffness matrix and mass matrix of the model, respectively. The characteristic frequency equation takes the form

Solving this characteristic equation yields the system’s natural frequencies . Substituting these frequency solutions into Equation (24) determines the undetermined coefficient vectors and , thereby reconstructing the corresponding mode shape functions to obtain vibration modes at each natural frequency of the model.

3. Analysis and Verification

A specific wind tunnel stiffened plate was analyzed. A structural finite element analysis (FEA) was first conducted. Modal testing was then carried out to validate the accuracy of the FEA results. Using the FEA results as a reference, the solution accuracy of the enhanced beam–plate model was verified. The overall dimensions of the stiffened plate are 1000 mm × 300 mm. Stiffener coordinates in the x-direction are at 114.0, 307.0, 500.0, 693.0, and 886.0 mm, and in the y-direction at 100.0 and −100.0 mm. Both stiffeners and the base plate are fabricated from aluminum alloy 7075 with material properties: density = 2.81 × kg/, Young’s modulus E = 72.0 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio = 0.33. Geometric dimensions: flap plate thickness t = 3 mm, stiffener thickness b = 5 mm, total stiffener height H = 40 mm.

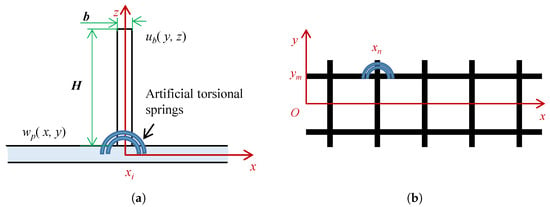

3.1. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

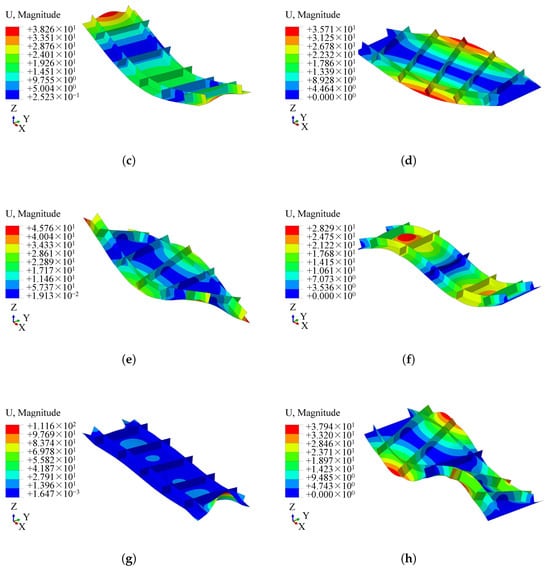

The finite element model of the stiffened plate was established using four-node reduced-integration shell elements (S4Rs), with a global mesh size of 5 mm totaling 17,949 elements. Both free-vibration (boundary condition: FFFF, i.e., all edges free) and constrained-vibration analyses (boundary condition: SSFF, i.e., x-direction edges simply-supported, y-direction edges free) were performed. Figure 4 presents the free-vibration modal results. The first four natural frequencies are 41.53 Hz, 183.87 Hz, 207.16 Hz, and 428.40 Hz, respectively. Figure 4 also presents the constrained-vibration mode results of the wind tunnel stiffened plate. The first four natural frequencies are 95.50 Hz, 108.94 Hz, 322.99 Hz, and 372.42 Hz, respectively.

Figure 4.

First 4 free-vibration modes of the wind tunnel stiffened plate with boundary condition FFFF and SSFF: (a) Mode 1 (FFFF). (b) Mode 1 (SSFF). (c) Mode 2 (FFFF). (d) Mode 2 (SSFF). (e) Mode 3 (FFFF). (f) Mode 3 (SSFF). (g) Mode 4 (FFFF). (h) Mode 4 (SSFF).

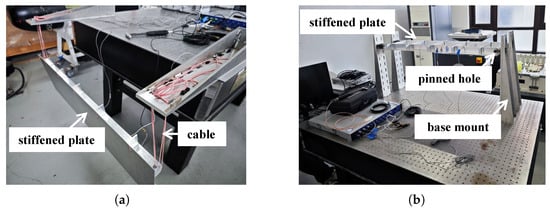

3.2. Verification of FEA Results Through Modal Testing

Free-vibration modal testing was conducted using a suspension setup with the SIMO (Single-Input Multi-Output) approach, where impact hammer excitation was applied at mobile points while accelerometers remained fixed at reference locations, as shown in Figure 5a. This widely adopted technique ensures high measurement accuracy. Five accelerometers were mounted on the structure surface as fixed reference points to record vibration response signals. A total of 311 impact points were strategically distributed to cover all critical regions: 171 points on the panel surface and 140 points along the stiffeners, guaranteeing comprehensive spatial sampling. Four pinned holes were machined on the stiffened plate adjacent to the base plate, with two holes positioned at each end along the x-direction. The test specimen was connected to clevis brackets via these pinned holes. The clevis brackets were then fastened with bolts to a height-adjustable base mount, which was rigidly fixed to the test rig. The vertically adjustable mounting positions of the clevis brackets are illustrated in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

Modal test setup of the stiffened plate specimen. (a) Free-vibration test. (b) Constrained-vibration test.

As presented in Table 1, the errors between the finite element analysis (FEA) and the model test for all modal frequencies are within 5%, except for the fourth free-vibration mode. This close agreement validates that the established finite element model possesses sufficient accuracy and reliability. More critically, the high-confidence FEA results established in Table 1 provide a reliable quantitative benchmark for the subsequent systematic comparison of computational accuracy between the conventional beam–plate model (BPM) and the proposed extended beam–plate model (EBPM). The larger error observed for the fourth mode (specifically, 5.76%) is primarily attributed to insufficient excitation of that local mode during testing. This discrepancy does not undermine the overall confidence in the finite element model nor its effectiveness as a benchmark.

Table 1.

Comparison of modal test and simulation results.

To quantitatively assess the consistency of mode shapes between the theoretical models and the finite element model, the Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC) is employed in this study. The MAC evaluates the spatial correlation between two mode shape vectors, and , and is defined as follows:

where the superscript T denotes the transpose. A MAC value closer to 1 indicates a higher degree of consistency between the two mode shapes. For the computation, to ensure the mode shape vectors from FEA are comparable to those from the mode test at identical degrees of freedom, the nodal displacement vectors from the FEM model were appropriately selected and interpolated to match the DOF distribution of the test. Subsequently, MAC values were calculated for the first four mode pairs. The MAC matrix exhibits dominant diagonal elements, with all diagonal values exceeding 0.99 and all off-diagonal values remaining below 0.10. This indicates strong correlation between the test and FEA mode shapes, as well as good independence among different modal orders.

3.3. Accuracy Assessment of EBPM Using FEA as Benchmark

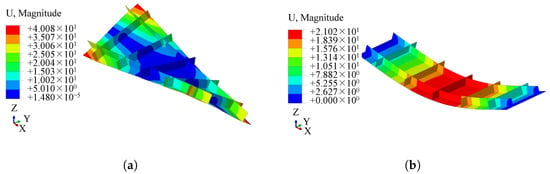

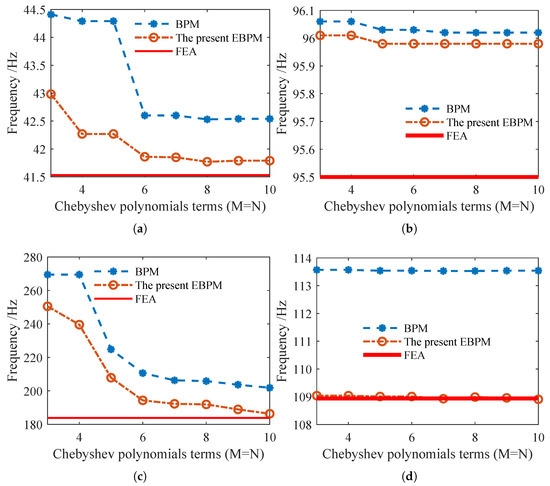

The value of the virtual spring stiffness coefficient in the penalty function is selected based on convergence studies for similar problems in the literature [39,40,41]. These studies indicate that the free-vibration results become insensitive to the specific value of the virtual spring stiffness coefficient once it exceeds a certain threshold (typically > N/m). Therefore, to enforce interface displacement compatibility, a value of 1 × N/m is used in this work, which lies within the verified stable range. The order of the displacement trial functions influences the approximation accuracy of the mode shape functions, thereby affecting the precision of the numerical solutions. To more accurately evaluate the solution accuracy of the EBPM, displacement trial functions were constructed using Chebyshev polynomials of orders 3 to 10. Natural frequencies of the wind tunnel stiffened plate were computed and compared against FEA results to evaluate the accuracy of BPM and EBPM.

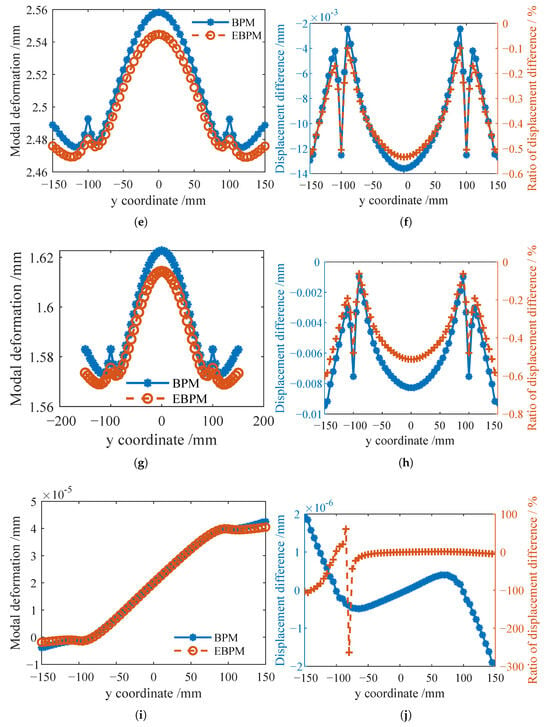

Figure 6 shows the convergence of numerical solutions obtained by the BPM and EBPM for free-vibration frequencies under the boundary conditions of FFFF and SSFF. The solid red line represents the corresponding FEA reference value. As the order of the displacement trial functions increases, the errors between both the BPM and EBPM numerical solutions and the FEA reference value decrease. For the same order of displacement trial functions, the EBPM yields smaller errors compared to the FEA reference, demonstrating its superior accuracy. Numerical validation demonstrates that the EBPM significantly improves accuracy over the BPM: errors in free-vibration frequency decrease from 2.42% to 0.63% for the first mode and from 9.79% to 1.34% for the second mode. For constrained vibration, the second-mode error is reduced from 4.22% to 0.03%.

Figure 6.

Convergence of numerical solutions obtained by the BPM and EBPM with boundary conditions FFFF and SSFF. (a) First-mode frequency (FFFF). (b) First-mode frequency (SSFF). (c) Second-mode frequency (FFFF). (d) Second-mode frequency (SSFF).

In summary, The curves exhibit asymptotic convergence toward FEA values (red lines) with increasing polynomial order, consistent with free-vibration trends. The present EBPM achieves superior accuracy.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Differences in the Deformation of Stiffeners

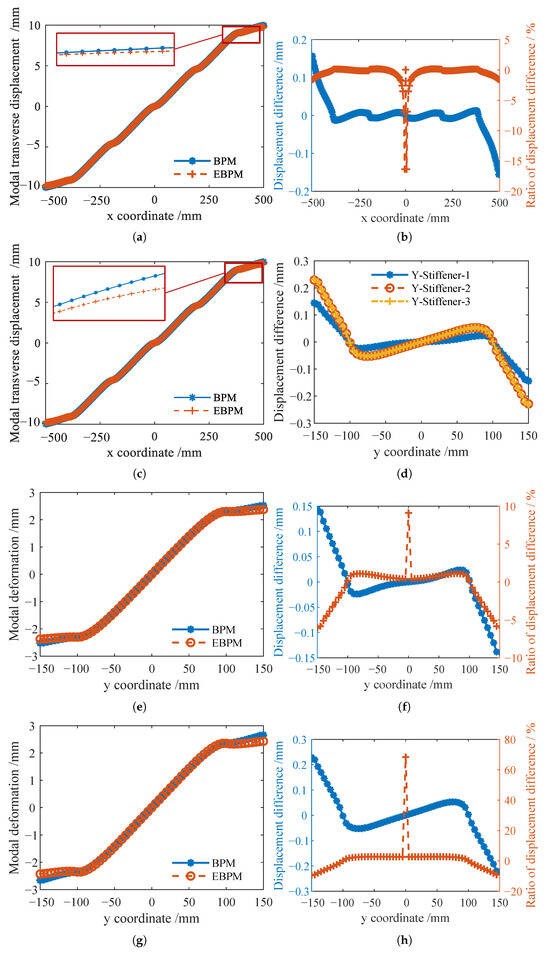

Stiffeners at the locations shown in Figure 2b were selected for analysis. Two stiffeners along the x-direction were chosen to comparatively analyze the influence of symmetric arrangement on their deformation. Three stiffeners on one side along the y-direction were selected to examine the effect of stiffener location on deformation. Using the displacement at the top point of the stiffener cross-section as the deformation value, the differences in deformation displacements calculated by the EBPM and BPM were compared and analyzed. To quantitatively compare the differences in transverse modal deformation displacements of the stiffeners solved by the EBPM and BPM, the displacement difference and its ratio to the local deformation displacement are defined as

where and represent the transverse modal deformation displacements at the identical top location of the stiffener cross-section, solved using the EBPM and BPM approaches, respectively.

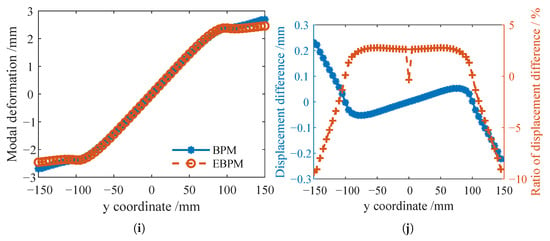

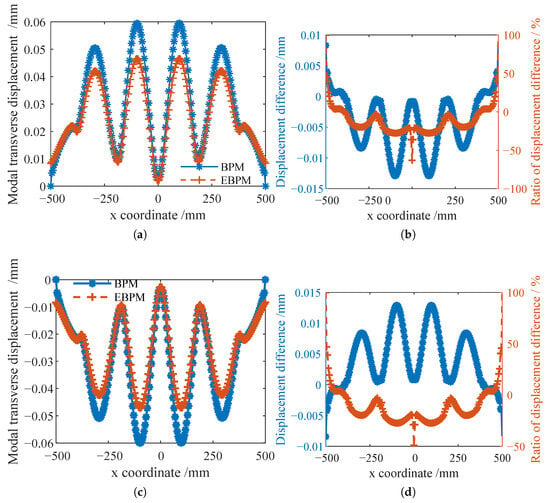

Figure 7 shows the modal transverse deformation displacements of the stiffeners and the ratio of the displacement difference to the local deformation calculated by the EBPM and BPM under the boundary condition FFFF. Figure 7a,c,e,g,i show the modal transverse deformation displacements of the stiffeners. It can be observed that the deformation is consistent for the symmetrically arranged stiffeners along the x-direction, and the absolute value of the displacement difference of the y-direction stiffeners increases for all three stiffeners near the boundary regions. Figure 7d shows these differences. Figure 7b presents the modal deformation displacement difference and its ratio to the local deformation for the transverse modal deformation of X-Stiffener-1. The absolute value of the displacement difference increases near the boundary regions. At the junction between the x-direction stiffener and the y-direction stiffener located at , the displacement difference ratio exhibits a sudden change due to the zero local deformation displacement. Excluding these singular values, it can be observed that both the displacement difference and its ratio to the local deformation displacement for the x-direction stiffener remain very small, with the ratio approximately 0.2%. Figure 7f,h,j show the modal deformation displacement difference and its ratio to the local deformation for the transverse modal deformation of the y-direction stiffeners. The displacement difference ratio for the first stiffener is approximately 1.08%, while those for the other two stiffeners are about 2.79%.

Figure 7.

Comparison of displacement difference and its ratio to local deformation for transverse modal deformation of stiffeners solved by EBPM and BPM (Boundary condition: FFFF, Mode 1). (a) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of X-Stiffener-1. (b) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation for X-Stiffener-1. (c) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of X-Stiffener-2. (d) Modal transverse displacement difference of Y-Stiffeners solved by BPM and EBPM. (e) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-1. (f) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-1. (g) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-2. (h) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-2. (i) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-3. (j) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-3.

Figure 8 shows the modal transverse deformation displacements of the stiffeners and the ratio of the displacement difference to the local deformation calculated by the EBPM and BPM under the boundary condition SSFF. The global first-order mode shape of the stiffened plate exhibits overall bending, where the transverse deformation of the stiffeners is not the dominant mode. Consequently, the displacement differences between the EBPM and BPM solutions were very small.

Figure 8.

Comparison of displacement difference and its ratio to local deformation for transverse modal deformation of stiffeners solved by EBPM and BPM (Boundary condition: SSFF, Mode 1). (a) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of X-Stiffener-1. (b) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation for X-Stiffener-1. (c) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of X-Stiffener-2. (d) Modal transverse displacement difference of Y-Stiffeners solved by BPM and EBPM. (e) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-1. (f) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-1. (g) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-2. (h) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-2. (i) Modal transverse displacement curves at the top of Y-Stiffener-3. (j) The ratio of displacement difference to local deformation of Y-Stiffener-3.

In summary, for the overall bending mode shapes, the discrepancy between the modal displacements solved by the EBPM and BPM is relatively small. In contrast, for the overall torsional mode shapes, the difference in modal displacements obtained by the two methods is more significant. Compared to the junctions between stiffeners, larger discrepancies are observed near the boundaries and at the midpoints of the stiffeners.

4.2. Influence of Height-to-Thickness Ratio on Frequency Solution Errors

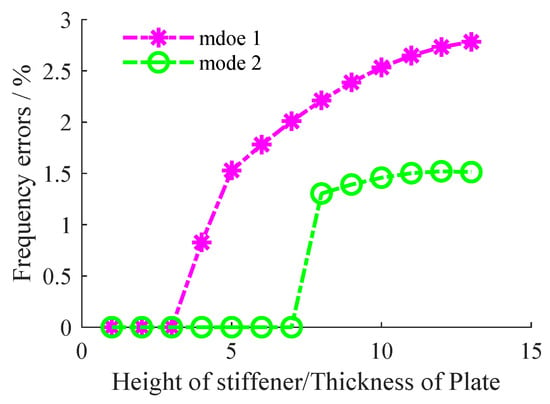

The EBPM is primarily employed for stiffened plates with large ratios of stiffener’s height-to-plate’s thickness. Under free-vibration conditions, natural frequencies of the wind tunnel stiffened plates were computed using both BPM and the present EBPM. A quantitative analysis was conducted to evaluate solution errors across varying height-to-thickness ratios. Figure 9 shows the error curves of the structural frequencies calculated by BPM and EBPM, with the frequencies solved by EBPM as the reference. For the first-order frequency, when the height-to-thickness ratio exceeds three, the transverse deformation of the stiffener begins to affect the frequency. As the height-to-thickness ratio increases, the error in the first-order frequency also increases, but the rate of increase slows down. At a height-to-thickness ratio of 13, the error in the first-order frequency is 2.80%. For the second-order frequency, when the height-to-thickness ratio exceeds eight, the transverse deformation of the stiffener starts to influence the frequency. The error in the second-order frequency rapidly stabilizes, reaching 1.52% at a height-to-thickness ratio of 12.

Figure 9.

Frequency solution errors of BPM relative to EBPM versus height-to-thickness ratio.

The engineering significance of the convergence plots and stiffener displacement comparisons presented in this study lies in quantifying the level of accuracy improvement offered by the EBPM over the conventional BPM. In practical engineering, such as in aircraft panel design, a frequency error exceeding 5% could lead to misjudgment of critical flutter speeds. The data in the figures demonstrate that the EBPM reduces the frequency error for key modes from over 5% with the BPM to within 2%. This improvement directly enhances design reliability. Furthermore, the complex transverse deformation patterns of the stiffener revealed by the EBPM, which are missed by the BPM, provide direct guidance for understanding the structure’s true response under aerodynamic loads and for optimizing vibration suppression strategies.

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- Key Advantages and Applicability: The extended beam–plate model (EBPM) proposed in this study significantly improves the analysis accuracy for free vibration of tall stiffened plates compared to the conventional BPM by incorporating a plate-theory-based description of stiffener transverse deformation. The distinct advantage of the EBPM is most evident for structures with a large stiffener height-to-thickness ratio (h/t): when h/t > 3, the transverse deformation begins to exert a non-negligible influence on the first-order mode; when h/t > 8, its effect on the second and higher-order modes becomes significant. Under these conditions, the BPM, which neglects transverse deformation, introduces substantial errors, whereas the EBPM maintains high accuracy.

- 2.

- Limitations: The enhanced accuracy of the EBPM stems from a more refined mechanical modeling of the stiffener, which inevitably introduces additional displacement degrees of freedom, resulting in a computational cost slightly higher than that of the BPM. Therefore, for stiffened plates with a small h/t where engineering accuracy requirements are met, the simpler BPM can be prioritized. For critical structures with large height-to-thickness ratios, the EBPM is recommended to obtain more reliable results.

- 3.

- Application Prospects and Extensions: The EBPM provides an efficient and accurate theoretical tool for the dynamic analysis of structures with large height-to-thickness ratios, such as those in wind tunnels. The theoretical framework established in this work can be directly extended to more complex engineering problems, for instance: (i) forced vibration response analysis under harmonic or random excitation and (ii) preliminary fluid–structure interaction (flutter) analysis considering aerodynamic loads. These extensions hold clear engineering value for the vibration control design and aeroelastic safety assessment of wind tunnel test sections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.; methodology, Z.C.; software, B.M.; validation, B.M., W.C. and Y.M.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, X.G.; resources, X.N.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, X.N.; visualization, X.G.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, X.G.; funding acquisition, X.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Project on Technology of China (Grant No. 2022G02000220007).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study are available from the authors and can be shared upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, F.; Chen, S.; Shi, J.; Tian, H.; Zhao, Y. Evaluation and Optimization of a Hybrid Manufacturing Process Combining Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing with Milling for the Fabrication of Stiffened Panels. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugré, A.; Vadean, A.; Chaussée, J. Challenges of using topology optimization for the design of pressurized stiffened panels. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2016, 53, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, A.; Avi, E.; Romanoff, J. Correction of local deformations in free vibration analysis of ship deck structures by equivalent single layer elements. Ships Offshore Struct. 2019, 14, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, L.; Guo, K. Flexural wave band gaps and vibration attenuation characteristics in periodic bi-directionally orthogonal stiffened plates. Ocean Eng. 2019, 178, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.R.; Barik, M. A numerical investigation on the dynamic response of stiffened plated structures under moving loads. Structures 2020, 28, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Wang, R.; Xin, H. A New Approach for the Free Vibration of Steel Bridge Deck with Stiffeners. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2012, 15, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.; Karimi, M.; Maxit, L. Semi-analytical formulation to predict the vibroacoustic response of a fluid-loaded plate with ABH stiffeners. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205, 112539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tian, W. Bandgap formation and low-frequency structural vibration suppression for stiffened plate-type metastructure with general boundary conditions. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Lin, R.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Q. Experimental Study of the Vibration of Blades Induced by Flow and Sound in a Plane Cascade under Low Wind Speed. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 37, 04024035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ri, Y.H.; Rim, U.R.; Mun, J.S. A study for the bending vibration analysis of the intermittently welded stiffened plate. Mar. Struct. 2024, 98, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, L.; Dong, C. Strongly nonlinear free vibration of four edges simply supported stiffened plates with geometric imperfections. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 3469–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedani, S.J.; Khedmati, M.R.; Azkat, S. Vibration analysis of stiffened plates using finite element method. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2012, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, E.; Abajo, D. Buckling and modal analysis of rotationally restrained orthotropic plates. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2015, 78, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Bai, J.; Li, X. Analytical study on the flexural wave band gaps of arbitrary periodic stiffened plates by using beam-plate coupling theory. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 208, 112802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qiao, P. Explicit Analytical Solution for Free Vibration of Restrained Orthotropic Plates. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2025, 38, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Xing, Y. Semi-Analytical Solutions for Free Vibration and Flutter of Stiffened Plates. AIAA J. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Kapania, R.K. Free Vibration Analysis of Integrally Stiffened Plates with Plate-Strip Stiffeners. AIAA J. 2016, 54, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damnjanović, E.; Marjanović, M.; Nefovska-Danilović, M. Free vibration analysis of stiffened and cracked laminated composite plate assemblies using shear-deformable dynamic stiffness elements. Compos. Struct. 2017, 180, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhbatolfoghahai, A.; Navazi, H.M.; Haddadpour, H. High-frequency random vibrations of a stiffened plate with a cutout using energy finite element and experimental methods. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2020, 234, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Chen, X. Predicting dynamic response of stiffened-plate composite structures in a wide-frequency domain based on Composite B-spline Wavelet Elements Method (CBWEM). Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 144, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Shen, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Peng, L.X. Bending and free vibration analyses of circular stiffened plates using the FSDT mesh-free method. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Xiang, J.; He, X.; Shen, Y.; Chen, W.; Peng, L.X. Buckling analysis of skew and circular stiffened plates using the Galerkin meshless method. Acta Mech. 2022, 233, 1789–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Shahabian, F.; Hassani, B. Free vibration analysis of free-form stiffened shells based on isogeometric method. Eng. Comput. 2025, 41, 1903–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ren, N. Free vibration analysis of stiffened rectangular plate with cutouts using Nitsche based IGA method. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 181, 109975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhao, T.; Yang, Z. Theoretical modelling and design of metamaterial stiffened plate for vibration suppression and supersonic flutter. Compos. Struct. 2022, 282, 115010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Liang, N.; Peng, L.X. Meshless simulation and experimental study on forced vibration of rectangular stiffened plate. J. Sound Vib. 2022, 518, 116602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yaakoubi-Mesbah, C.; Mittelstedt, C. Closed-form analytical solution for local buckling of omega-stringer-stiffened composite panels under compression. Compos. Struct. 2025, 353, 118716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Pan, J.; Lin, T.R. Vibration of rectangular plates stiffened by orthogonal beams. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 513, 116424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Sun, J.; Lin, Y.; Fang, Y. Free and Forced Vibration Characteristics of a Composite Stiffened Plate Based on Energy Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Niu, J.; Jia, R. Dynamic analysis of arbitrarily restrained stiffened plate under moving loads. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 200, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Niu, M.Q.; Deng, L.F.; Chen, L.Q. Free and forced vibrations of a periodically stiffened plate with functionally graded material. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2022, 92, 3229–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.Q.; Jiang, W.K. Vibration analysis of stiffened multi-plate structure based on a modified variational principle. J. Vib. Control 2017, 23, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jin, G.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Y. An extended Chebyshev spectral method for vibration analysis of rotating cracked plates. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 229, 112558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamijani, A.Y.; Kapania, R.K. Vibration Analysis of Curvilinearly-Stiffened Functionally Graded Plate Using Element Free Galerkin Method. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2012, 19, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, V.; Milazzo, A. A Rayleigh-Ritz approach for postbuckling analysis of variable angle tow composite stiffened panels. Comput. Struct. 2018, 196, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamijani, A.Y.; Kapania, R.K. Chebyshev-Ritz Approach to Buckling and Vibration of Curvilinearly Stiffened Plate. AIAA J. 2012, 50, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.R.; Tamijani, A.Y. Flutter Analysis of Laminated Curvilinear-Stiffened Plates. AIAA J. 2017, 55, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Sun, J.; Ma, X.; Sun, J.; An, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, T. Free Vibration Analysis of Thin Rectangular Plates with Mixed Point Support Conditions Using the Rayleigh Ritz Method. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2025, 38, 04025067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Chen, W.H.; Li, D.K.; Ma, B.; Nie, X.T. Theoretical Analysis and Solution of Transverse Free Vibration of Fish Bone Active Camber Morphing Airfoil. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, A.E.; Weaver, P.M.; Cooper, J.E.; Woods, B.K. Parametric structural modelling of fish bone active camber morphing aerofoils. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 2008–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.H.; Wu, Z.; Weaver, P.M. Buckling analysis of stiffened variable angle tow panels. Compos. Struct. 2014, 111, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.