Abstract

When a fire occurs in a tunnel during construction, the smoke cannot be discharged in time and continues to settle near the ground, which threatens the safety of personnel. It is essential to understand smoke layer distribution for safe evacuation. To fill the knowledge gap for the spatio-temporal distribution of the smoke layer, a series of fire experiments are carried out in 1/20 reduced-scale tunnel models. Multiple variables are considered, including longitudinal fire location, heat release rate, aspect ratio of the main tunnel, and the inclined shaft length. Two fire scenarios are defined according to the longitudinal fire location in the main tunnel: near the upstream closed end (scenario 1) and near the downstream closed end (scenario 2). The results show that the structural evolution of the smoke layer inside the main tunnel experiences roughly three stages: single-layer smoke flow stage, transition stage, and two-layer smoke flow stage. In different fire scenarios, the reasonable N value is 10, determined by comparing the smoke layer interface height (hs) predicted by the N-percentage method with the observed results. Moreover, we find that the FDS simulation method has significant deviation in predicting poor stratification situations. Furthermore, the spatio-temporal distributions of hs in the main tunnel are predicted based on N = 10. The coupled effects of heat release rate and the longitudinal fire location on the hs values are analyzed. The tar value (time of smoke arrival at the respiratory height) is determined, and its spatial variations are predicted. By comparing the tar values at position 2# (near the inclined shaft) in different fire scenarios, we can provide a reference for the evacuation of personnel.

1. Introduction

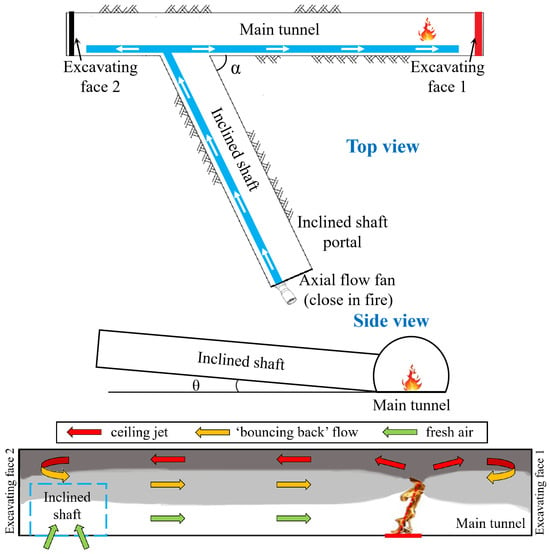

The rapid increase in tunnels under construction leads to frequent fire accidents during the construction period [1]. Table 1 lists the summary of the tunnel fire accidents under construction all around the world. Fire accidents cause large amounts of casualties. Fire safety and rescue in tunnels under construction is an increasing issue. It should be emphasized that the ventilation system stops when a fire event occurs, and the forced ventilation mode switches to natural ventilation mode. As illustrated in Figure 1, the smoke initially flows to two excavating faces (closed ends), then returns reversely and ultimately flows outside the tunnel. The two-layer smoke flow beneath the tunnel ceiling significantly reduces the smoke layer height [2]. It poses a threat to the lives of the workers inside. Hence, it is urgently necessary to conduct research on the spatio-temporal distribution of the smoke layer interface height in tunnel fires.

Table 1.

Statistics of tunnel fire accidents under construction [1,3].

Figure 1.

Tunnel fire during construction period and smoke flow pattern within main tunnel [4,5].

Unfortunately, few researchers have focused on this topic. Based on the temperature measurement in a 1/40 reduced-scale model tunnel, Yao et al. [6] study the smoke arrival time and the smoke propagation speed at three heights above the tunnel floor. Using FDS simulation, Yao et al. [7] explore the stratified structure of the smoke layer and clarify the improvement effect of drainage devices on the natural smoke exhaust rate. Fan et al. [8] simulate the chimney effect on smoke diffusion characteristics (including gas temperature, diffusion process, and backflow of the smoke) in an inclined laneway. Xu et al. [5] reveal the structure evolution of two-layer smoke flow and find the self-similarity trait of the vertical temperature profiles inside the main tunnel. However, the above studies do not investigate the spatio-temporal distribution of smoke layer height inside the tunnel.

As for the determination of the smoke layer interface height (hs), the previous researchers have proposed various methods. The laser tracer method is a relatively intuitive method that enhances the visibility of smoke flow by irradiating solid particles with a laser light sheet. With its assistance, the smoke layer is clearly visible, but it is limited to the local region.

Based on the temperature distribution in the vertical direction, the previous researchers propose several computing methods to determine the hs value in atrium and tunnel fires. These methods include the integral ratio method [9,10], the buoyancy frequency method [11,12], and the N-percentage rule method [13,14,15]. The integral ratio method is essentially a measure of the data uniformity. At the smoke layer interface height, the sum of the upper layer integral ratio and the lower layer integral ratio is deemed to be the smallest. Some researchers have also expressed different opinions on the effectiveness of this method. Gao et al. [11] pointed out that the results obtained by visual estimation are lower than those obtained by the integral ratio method. And it cannot calculate accurate results in the area both near and far from the fire source [16]. The buoyancy frequency method assumes that the density of the smoke layer has a sufficiently large gradient. The greatest density difference position is accordingly regarded as the smoke layer interface height. Hence, it is not suitable for poor smoke stratification scenarios and complex smoke layering [17].

By comparison, the N-percentage rule method is most widely used in multiple fire scenarios, including tunnels [18,19,20], atriums [13,21,22], and multi-rooms [14,15]. Based on the maximum temperature rise and assumed percentage (N), the gas temperature at the smoke layer interface height (Ti) and its position are identified in the following manner:

where Ta and Tmax are the ambient temperature and maximum temperature, K. The predicted hs value is found to be sensitive to the N value. The N values in the previous studies vary from 10, 15, 20, 30, to 37, etc. Hence, the appropriate N value suitable for the specific fire scenario should be synthetically examined.

Besides the above temperature-oriented methods, computer vision algorithms have also recently been proposed to identify fire and smoke. Weng et al. [23] establish a smoke layer interface detection method based on deep learning. They conduct an investigation into application in a 1/10 reduced-scale model tunnel under the longitudinal ventilation condition. Jiang et al. [24] propose a novel transfer learning framework to inverse fire location and real-time HRR in tunnel fires. It is pretrained on numerical simulation datasets and the limited measured temperature data. These methods perform well and have validated their reliability in reduced-scale or full-scale tunnel fire tests. However, the optimization of the model is significantly dependent on a huge amount of training data. For the tunnel fire under construction, it is difficult to obtain sufficient data to train the model. This limits their applications in this kind of tunnel to a large extent.

In this study, two L-shaped 1/20 reduced-scale model tunnels are constructed to simulate tunnel fire scenarios under construction sites. Multiple variables, including the longitudinal fire positions (dm), fire heat release rates (Qm), aspect ratios of the main tunnel (Hmain/Wmain), and inclined shaft lengths (Lshaft) are taken into consideration. The objectives of this research are summarized as follows: (1) Determine the smoke layer interface height by the combination of laser tracer, N-percentage, and FDS methods. (2) Obtain the reasonable N value suitable for this specific fire scenario. (3) Predict the spatio-temporal distribution of the smoke layer interface height in the main tunnel. (4) Determine the smoke arrival time at the respiratory height. This study can provide a reference for the assessment of safe personnel evacuation in the event of tunnel fires.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus

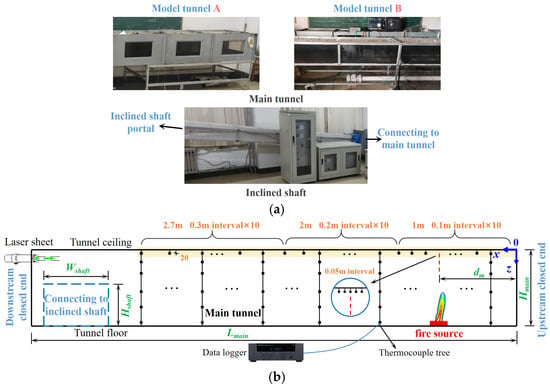

The geometric parameters of the prototype tunnel and the scaling correlations used are, respectively, presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The model tunnel A is built (see Figure 2) and its geometric parameters, including tunnel length L and cross-sectional area A, are listed in Table 4. The model tunnel consists of a main tunnel (with two closed ends) and an inclined shaft. The right closed end in the figure is defined as the upstream closed end, while the left closed end is defined as the downstream closed end. For illustration, x represents the distance from the upstream closed end, z represents the distance from the tunnel ceiling, and dm is the distance between the center of the fire source and the upstream closed end. The main tunnel is constructed with 11 mm thick fireproof gypsum board. One side wall is fitted with 8 mm thick heat-resistant glass for observation of smoke flow. The inclined shaft (inclined slope θ = 5°) is connected to the main tunnel at a 90° horizontal cross angle α, and is also made of 11 mm thick plasterboard. Model tunnel B, with the smaller cross-sectional area, is also built as a comparison, and its dimensions are also listed in Table 4.

Table 2.

The geometric parameters of the prototype tunnel.

Table 3.

Scaling correlations of the key parameters.

Figure 2.

Experimental apparatus for two tunnel models [4,5]. (a) Photos of the test benches. (b) Schematic of the devices and the measuring points.

Table 4.

Geometric dimensions of the two tunnel models.

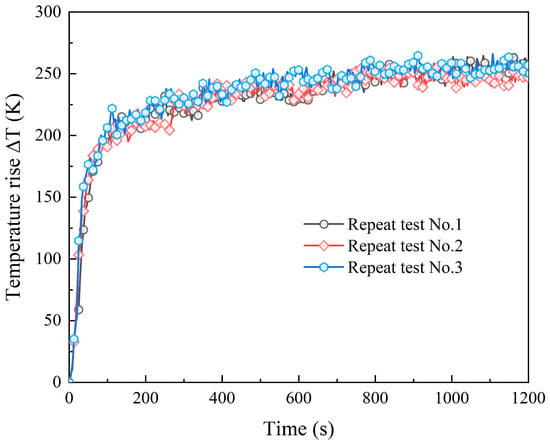

The fire source adopts a square porous burner with a side length of 0.1 m. To ensure a stable mass flow rate of propane (effective combustion heat ΔHc = 46.36 MJ/kg), a high-precision mass flowmeter (ALICAT, MC-20SLPM-D) is adopted. Various longitudinal fire source positions and fire heat release rates are considered in the tests. The small scale of fire is a significant distinction between construction tunnels and operational tunnels. The combustible components of the construction vehicles are the main fuels in tunnel construction sites, and their HRR is usually no more than 10 MW based on previous tests [25,26]. Therefore, the Qm value is set not to exceed 5.6 kW in the test. The detail parameters of the test cases are summarized in Table 5. Each test is repeated no less than three times for 20 min. Taking Case A3 as an example, the variation in temperature measured by three repeated experiments with time is plotted in Figure 3. The ceiling temperature at x = 0.35 m basically enters a quasi-steady state 50 s after ignition. The maximum instantaneous difference among the three measurements is 23.62 °C, with an error of 9.36%. Meanwhile, the difference between their average measured values is 6.62 °C, and the error is 2.65%. No occurrences of fire self-extinguishment are observed in all the test cases. The reason has been explained in our previous work [5] and is not repeated here.

Table 5.

Summary of the test cases.

Figure 3.

The results of three repeated measurements at x = 0.35 m within 20 min of Case A3 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW).

A series of thermocouples (K-type, diameter: 1 mm) marked in Figure 2 are used to measure the gas temperature, and their detailed positions are listed in Table 6. The measurement plan includes monitoring the ceiling gas temperature with thirty thermocouples 2 cm beneath the ceiling and measuring the vertical gas temperature with thirteen thermocouple trees. All the temperature data measured by the thermocouples are recorded every 4 s by the data acquisition instrument (Keysight, 34980A). The smoke observation positions should be as far away as possible from the bright flame area. In model tunnels A and B, they are, respectively, located at a#, b# or c#, d#, as listed in Table 6. To enhance the visualization of the smoke layer, a laser sheet (wavelength 532 nm, Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Tech Co., Ltd. (CN)) is set close to the observation positions. For model tunnel A, it is set at the downstream closed end of the main tunnel, while for model tunnel B, it is located at the upstream closed end of the main tunnel. The structure evolution of the smoke layer near four observation positions (a#, b#, c#, and d#) are recorded by a digital video camera (Sony, RX100, Tokyo, Japan). The video record can roughly cover an area of 0.5 × 0.5 m centered on the observation position.

Table 6.

Detailed arrangements of measurement points and smoke observation positions.

2.2. Numerical Simulation Set-Up

The Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) is widely used in fire science to study the smoke diffusion. In this study, FDS version 6.7.1 is used and the Large Eddy Simulation (LES) method is adopted. The structure, size, and fire source settings of the numerical simulations are consistent with those of experiments. The ceiling, sidewall, floor, and closed end of the main tunnel, as well as those of the inclined shaft, are assumed to be ‘CONCRETE’. The boundary of the extended region is set as ‘OPEN’. The fire source is modeled as a propane gas burner and its output is set to the heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA).

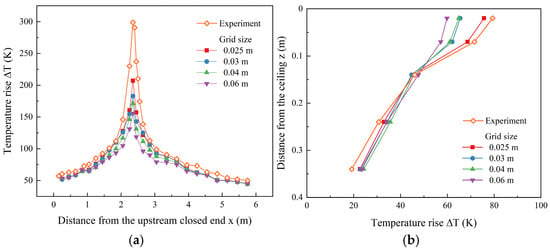

Grid size is a crucial parameter in simulation, which is related to the modeling accuracy and the computation time. Based on the D*/δx criterion [27,28], the grid size should range from 0.025 m to 0.06 m in this study. Taking Case A12 (dm = 2.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW) as an example, Figure 4 shows the longitudinal and vertical gas temperature distributions during the quasi-steady state simulated by FDS software. In comparison with the measured result, the ΔT values are underestimated when the grid size is greater than 0.04 m. The predicted values under the finer grid sizes (0.025 m to 0.03 m) tend to approach, and agree well with, the experimental data. Hence, the grid size of 0.025 m is small enough to meet the requirements of the grid independence analysis. The 0.025 m grid size is used in the simulation of this study.

Figure 4.

Gas temperature distributions simulated by FDS and measured experimentally for Case A12 (dm = 2.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW). (a) Variation in ceiling temperature with longitudinal distance. (b) Vertical temperature at x = 3.95 m.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Estimating Method for Smoke Layer Interface Height

3.1.1. Dynamic Evolution of the Smoke Layer

Due to the asymmetrical semi-enclosed structure, the smoke flow pattern in the main tunnel varies with the longitudinal fire source location. Here, two fire scenarios are considered. Fire scenario 1: the fire source is near the upstream closed end. Fire scenario 2: the fire source is near the downstream closed end. The fire source and the observation zone in these two fire scenarios are located at either end of the main tunnel. The smoke diffusion direction and the fresh air supply situation vary considerably. The dynamic evolution of smoke layer structure for these two scenarios will be further studied.

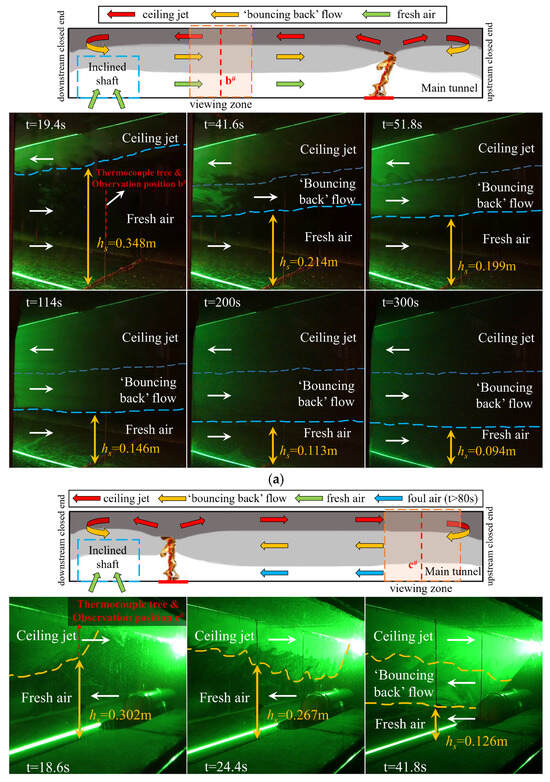

- Fire scenario 1

Taking test case A3 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW) as example, Figure 5a presents the dynamic evolution of smoke layer structure near the observation position b#. The structure of the smoke layer under the ceiling continues to develop, and its evolution is roughly summarized into the following three stages: the one-layer smoke flow (t < 19.4 s), fully developed bidirectional smoke layer (t > 114 s), and transitional stage (41.6 s < t < 51.8 s) in between. Unless otherwise specified, t in the paper is the time of the reduced-scale test. As time goes on, the smoke layer descends slowly but remains above a certain level (hs > 0.094 m at t = 300 s). In the vertical direction, there exists evident stratification involving the upper layer (ceiling jet), the middle layer (‘bouncing back’ flow), and the lower layer (fresh air).

Figure 5.

Dynamic variation in smoke flow pattern for fire scenarios 1 and 2. (a) Observation position b# for test case A3 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW) [4,5]. (b) Observation position c# for test case B3 (dm = 5.5 m, Qm = 5.03 kW).

- Fire scenario 2

Test case B3 (dm = 5.5 m, Qm = 5.03 kW) is chosen as the representative for fire scenario 2. The recorded smoke flow near the observation position c# is shown in Figure 5b. At t < 41.8 s, the smoke flow also goes through the same stages as those of fire scenario 1. However, there exists evident difference in the smoke flow structure at two observation positions. After t = 80 s, the original three-layer flow is destroyed, and the lower fresh air is replaced by the foul air layer. As time goes on to 300 s, the thickness of the foul air layer decreases to 0.027 m.

This is attributed to the large amount of air entrainment from two sides of the flame. For the downstream side, the fresh air is steadily replenished through the portal of the inclined shaft. Thus, three layers of flow are maintained in the form of ceiling jet, ‘bouncing back’ flow, and fresh air. Meanwhile, in the upstream of the fire, there is no fresh air supplement due to the closed end. Due to the obstruction of the fire source, the fresh air supply from the inclined shaft is limited as well. Along with the consumption of the fresh air, the ‘bouncing back’ smoke gradually settles to the floor and mixes with the remaining air. Thus, the lower fresh air is vitiated by the smoke and becomes the foul air. This difference in the smoke flow structure at two observation positions can also be reflected by the airflow velocity, as demonstrated in our previous work [4]. At the same distance from the fire source (1.25 m, Model 1, see Figure 5 in reference [4]), the airflow velocity at x = 4.9 m (upstream of the fire) in the lower part of the tunnel is 0.1–0.2 m/s. Meanwhile, the corresponding airflow velocity at x = 2.4 m (upstream of the fire) is close to 0. The decrease in airflow velocity clearly demonstrates the disappearance of the fresh air layer.

3.1.2. Determination of the Reasonable N Value

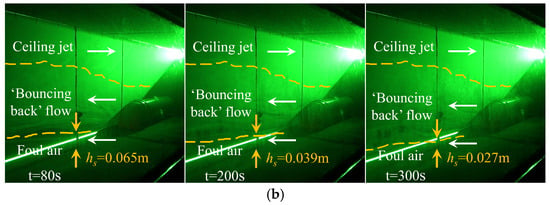

For the above two test cases, Figure 6 compares the hs values obtained by the laser tracer method, N-percentage method, and FDS simulation method. The N-percentage method has been discussed earlier. Here, the principle and process of obtaining hs through laser tracer and FDS methods are introduced in detail. The laser tracer method determines the interface by the observers watching the smoke video. The position for video recording and the settings of the laser sheet, camera, etc., have been elaborated in Section 2.1. The average observation results of three observers can well avoid random errors, which are shown in Figure 6 in the form of error lines. This study is more inclined to take the results obtained by laser tracer method as an accurate reference.

Figure 6.

Determination principle of the smoke layer interface height. (a) Fire scenario 1 at b# position for Case A3 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW). (b) Fire scenario 2 at c# position for Case B3 (dm = 5.5 m, Qm = 5.03 kW).

Within 30 s after ignition (see Figure 6), the predicted hs values are approximately at the same height, regardless of the N values. This is due to the small temperature gradient. At about 40 s, the hs obtained by the three methods drops abruptly as the ‘bouncing back’ flow reaches the viewing zone. With the increasing temperature gradient, the difference in hs between different N values increases accordingly. Overall, the predicted hs value increases as the N value increases, based on Equation (1). In comparison with fire scenario 1, the smoke layer interface height hs in fire scenario 2 decreases more dramatically. At t = 50 s, the hs value at b# under fire scenario 1 is 0.193 m, while that at c# under fire scenario 2 is only 0.112 m. The 41.97% difference between the two scenarios again confirms that the supply airflow from the inclined shaft has a significant impact on the smoke flow. When t > 50 s, the hs value simulated by FDS no longer decreases and remains near 0.13 m above the tunnel floor. Meanwhile, the hs values by visual observation and N-percentage methods still show the decreasing trends. At N = 10, the predicted hs curves of two fire scenarios are in best agreement with the visual observed values.

The speculation about the above differences is due to the calculation method of smoke layer height in FDS. FDS adopts the calculation methods of the smoke layer interface height proposed by Janssens and Tran [27,29], as shown in the following equation. They estimate layer height and average temperature based on the continuous vertical temperature profiles. The continuous function T(z) is introduced, defined as a temperature function of the height above the floor z. Where z = 0 represents the tunnel floor; z = H represents the tunnel ceiling; Tu is the upper layer temperature, K; Tl is the lower layer temperature, K. It should be noted that the Tl value in FDS is chosen as the temperature of the lowest mesh cell.

According to Equation (2), the rapid increase in Tu within 50 s after ignition leads to the rapid decrease in hs. The Tu value gradually stabilizes at 50 s, while Tl increases slightly, thereby causing the hs value to stabilize to be constant after t = 60–70 s. Meanwhile, the hs values by visual observation still decrease slowly. This leads to the evident difference between the predicted hs value and the visual observation results.

By comparison, this prediction deviation at c# under fire scenario 2 is larger than that of b# under fire scenario 1 (see Figure 6). This is attributed to the difference in the lower layer temperature distribution. For the latter, there is no evident temperature stratification in the lower fresh air layer. That is, the Tl value approximates the temperature of the lowest mesh cell. Meanwhile, the Tl value for the former has increased to a large extent, due to vitiation by the ‘bouncing back’ smoke. With the decreasing Tl, the predicted hs value from Equation (2) shows an increasing trend. This leads to the evident deviation of hs value by FDS from the visual observations. This demonstrates that the FDS method is not suitable for predicting the hs value for the scenario with thick smoke in the lower layer.

To sum up, for two fire scenarios, the applicability of the N-percentage method and the FDS method has been preliminary analyzed. In the following section, we will further discuss the rationality of N = 10.

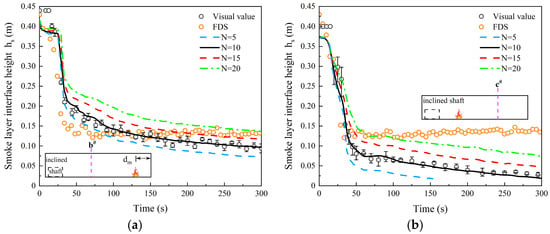

3.1.3. Verification of the Reasonable N Value

In Section 3.1.1, the flow characteristics and the height of smoke layer in two typical fire scenarios are analyzed in detail. The value of hs obtained by the laser tracer, N-percentage, and FDS simulation methods are compared. N = 10 is preliminarily identified as the appropriate value for the N-percentage method under this fire scenario. In this section, more experimental test cases are used to further verify this determined N value.

Figure 7 compares the hs values at three observation positions for multiple test cases (Case A2, Case A4, Case A7, and Case B3). These cases involve different longitudinal fire locations (dm = 0.45 m, 0.9 m, 1.25 m, and 5.5 m) and fire heat release rates (Qm = 2.8 kW, 4.2 kW, and 5.03 kW). It can be seen that the results of Figure 7a–c are similar to those of Case A3 (fire scenario 1), and the results of Figure 7d are similar to those of Case B3 (fire scenario 2). For four observation positions (a#, b#, c#, and d#) of these test cases, the hs curves of N = 10 match well with the visual values provided by the laser tracer method. N = 10 is sufficiently justified to be suitable for the fire scenarios in tunnels under construction.

Figure 7.

Comparison of smoke layer interface height obtained by three methods. (a) b# for Case A2 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 4.2 kW). (b) a# for Case A4 (dm = 0.9 m, Qm = 2.8 kW). (c) a# for Case A7 (dm = 1.25 m, Qm = 2.8 kW). (d) d# for Case B3 (dm = 5.5 m, Qm = 5.03 kW).

The error between the measured and predicted hs values is further evaluated using the Mean Relative Deviation (MRD) as follows [30]:

where Mvis and Mpre are the visual and predicted values of smoke layer interface height (hs), respectively. i is the number of visual values within 300 s. For N = 10, the MRD values for these cases are 7.15%, 7.67%, 9.18%, and 12.02%, respectively. The effectiveness of N-percentage method (N = 10) to determine the hs value is fully proven, despite the limited number of observation positions. This method is highly dependent on the vertical gas temperature profiles. Previously, our work [5] has revealed that the normalized temperature distributions for this kind of tunnel show a similar distribution pattern at any position within 1.82 ≤ │xm-dm│/Hef ≤ 10.68, independent of the values of Qm, dm, and hm. The smoke descent behaviors inside this region are deemed to be similar to those of a#, b#, c#, and d#. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that N = 10 is also suitable for the hs prediction in the above region.

Moreover, as expected, the hs values predicted by the FDS method stabilize to be constant after t = 60–70 s. And for the position upstream of the fire with poor smoke stratification, the results predicted by FDS may have a large deviation (see Figure 7d), and its use should be cautious. The FDS simulation method is more applicable to situations where there is good stratification (such as the downstream of the fire) at an early stage.

3.2. Application in Tunnel Fire Safety Assessment

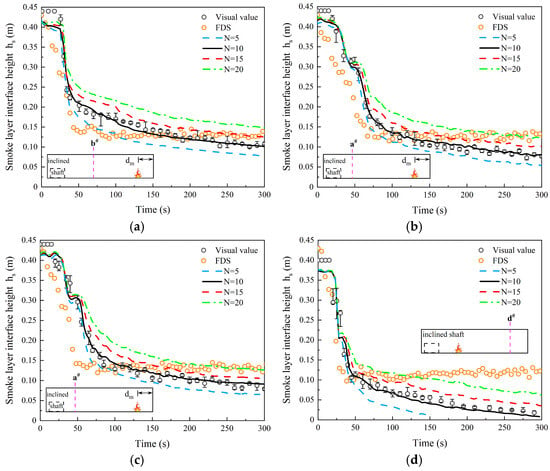

3.2.1. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of hs

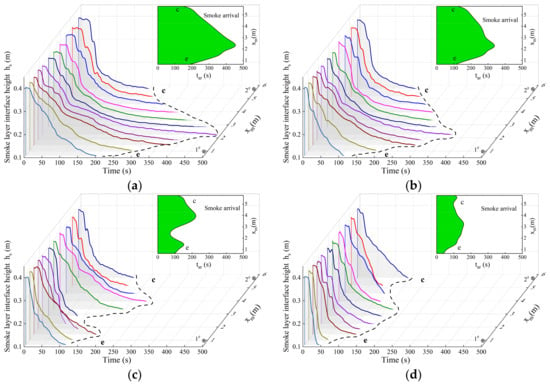

The transient smoke layer interface heights can be further predicted according to the temperature monitored by the N-percentage method (N = 10). Taking Case A1, Case A3, Case A12, and Case A18 as examples, Figure 8 indicates the spatio-temporal variation in the smoke layer interface height. Here, xm represents the distance between the thermocouple trees and the upstream closed end. At any position (0.65 m < xm < 5.75 m), the structural evolution of the smoke layer underneath the ceiling roughly experiences similar stages as to the observed results at observation positions a#, b#, c#, and d#.

Figure 8.

Spatio-temporal variation in smoke layer interface height in the main tunnel. (a) Case A1 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 2.8 kW). (b) Case A3 (dm = 0.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW). (c) Case A12 (dm = 2.45 m, Qm = 5.6 kW). (d) Case A18 (dm = 4.85 m, Qm = 5.6 kW).

As shown in Figure 8a, the time intervals of stage 1 and stage 2 are evidently prolonged with the increasing xm. And the smoke layer interface is much higher at the start of stage 3. Moreover, the smoke spread presents an accelerating trend as Qm increases. For the same position, both the first and second smoke arrival time have been advanced, as exhibited in Figure 8b. As mentioned above, the structure evolution of the smoke layer varies with the longitudinal fire source location. As the fire source moves to the downstream closed end (dm = 0.45 m → dm = 2.45 m → dm = 4.85 m), the smoke layer descends more rapidly, as illustrated in Figure 8b–d).

In addition, it can be seen from the results that the value of hs near the fire drops to 0.1 m much earlier. This is caused by the disruption of the original temperature profile by flame radiation. In the region of│xm-dm│/Hef < 1.82, the vertical temperature distributions vary considerably [5]. The predictive error of the N-percentage method (N = 10) in this region is estimated to increase accordingly. However, in actual situations, the near-fire area is generally not considered in safety assessment [31]. Hence, the effectiveness and the application of this predictive method are not affected.

3.2.2. Smoke Arrival Time

As time goes on, the smoke continues to descend until it approaches the tunnel floor. When the smoke layer interface descends to 0.1 m above the floor (corresponding to 2 m height in the prototype tunnel), the environmental conditions in the respiratory zone become unbearable and dangerous. For the evacuee trapped in fire, the smoke’s arrival at the respiratory height is a sign of potential danger. Here we define the time of smoke arrival at the respiratory height as tar. The curve c-e depicts tar spatial variation against the longitudinal position in the main tunnel, as indicated in Figure 8. The right side of the curve c-e indicates that the personnel’s respiratory region is full of smoke and the trapped people are in danger. The left side of the curve c-e represents an area where the smoke has not yet arrived and can be considered as a temporary ‘safe region’.

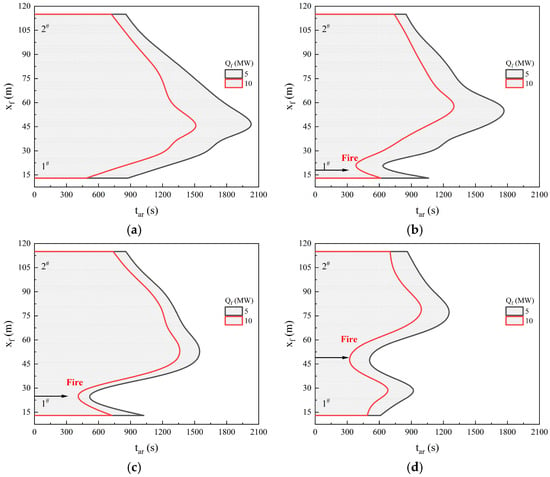

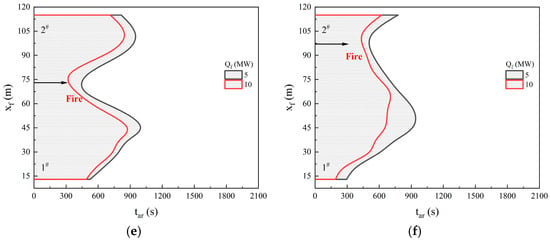

According to the Fr scaling, the tar spatial variations with the longitudinal position are further converted to the prototype tunnel and presented in Figure 9. The tar value presents an increasing trend as it moves away from the two closed ends, except near the fire source. Here, two typical locations 1# (near the upstream closed end) and 2# (near the inclined shaft) marked in Figure 8 are chosen as examples. As shown in Figure 9b, the tar values at 1# and 2# for Case A10 (dm = 2.45 m, Qm = 2.8 kW) in a full-scale tunnel are about 610 s and 861 s, respectively. With the increasing Qf, the tar values decrease significantly and the region full of smoke shows an obvious expansion trend. As exhibited in Figure 9d, the tar values at 1# and 2# are reduced by 122 s and 160 s, respectively. In addition, the longitudinal fire location evidently influences the tar values. As the fire source moves to the downstream closed end, the ‘safe region’ becomes smaller. For Qf = 10 MW, when df increases from 9 m to 49 m and then to 97 m, the tar value at 2# decreases from 721 s to 701 s and then to 622 s, as illustrated in Figure 9a–f.

Figure 9.

Determined tar value against the df and Qf (in prototype tunnel). (a) df = 9 m, Qf = 5/10 MW. (b) df = 18 m, Qf = 5/10 MW. (c) df = 25 m, Qf = 5/10 MW. (d) df = 49 m, Qf = 5/10 MW. (e) df = 73 m, Qf = 5/10 MW. (f) df = 97 m, Qf = 5/10 MW.

It should be emphasized that there are many fire safety assessment criteria (such as temperature, CO concentration, visibility, etc.) besides the smoke layer interface height. This study mainly aims to quickly predict the spatio-temporal distribution of smoke layer interface height by temperature measurement. Although it has its limitations in evaluating personnel safety, the conclusions of this study can also provide an effective reference for engineering.

3.3. Limitations and Future Work

Overall, the method for determining the smoke layer interface height based on the N-percentage rule proposed in this paper can provide a strong reference for fires that occur during tunnel construction. However, we must acknowledge that there are still some limitations in the study: without considering the change in the main tunnel length, the prediction of the smoke layer interface height near the fire source may be unreliable due to the influence of flame radiation. Future research should quantify the impact of flame radiation on the smoke layer and take into account more variables to ensure that the results have wider applicability.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the L-shaped 1/20 reduced-scale model tunnels and numerical models were established. Multiple variables such as the heat release rate of the fire source and its longitudinal location, the main tunnel aspect ratios, and the inclined shaft length were considered. Three methods including the laser tracing method, N-percentage rule method, and FDS numerical simulation method were employed to investigate the spatio-temporal distribution of the smoke layer interface height within the main tunnel. The main conclusions we have obtained are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- In the two fire scenarios, the structural evolution of the smoke layer inside the main tunnel roughly experiences three stages. For fire scenario 1, a clear flow of three layers is maintained inside the tunnel. Meanwhile, for fire scenario 2, after t > 80 s, the original smoke stratification upstream of the fire is destroyed, and the lower fresh air is replaced by the foul air layer.

- (2)

- For multiple typical test cases and observation positions, the reasonable N value is 10 through the comparison and verification of the visual values with the predicted values of the N-percentage method.

- (3)

- It is found that the FDS simulation method is suitable for situations with good stratification. However, it is not suitable for situations with poor stratification, such as the area between the fire and the closed end. It should be used with caution because its prediction may have significant deviations.

- (4)

- The spatio-temporal distributions of hs are further predicted based on N = 10. With the increase of Qm, the settlement velocity of the smoke is accelerated. Except near the fire source, the hs value decreases rapidly with distance from the fire source, and reaches 0.1 m above the tunnel floor earlier.

- (5)

- The heat release rate and the longitudinal fire location evidently influence the value of tar. When df = 49 m, as Qf increases, the tar at 1# and 2# are reduced by 122 s and 160 s, respectively. As the fire source moves to the downstream closed end, the ‘safe region’ becomes smaller. For Qf = 10 MW, when df increases from 9 m to 49 m and then to 97 m, the tar value at 2# decreases from 721 s to 701 s and then to 622 s.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X. and C.D.; methodology, L.X. and C.D.; formal analysis, M.Q. and S.Z.; data curation, M.Q., Y.Z. and L.L.; writing—original draft, L.X. and M.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.D.; supervision, C.D.; funding acquisition, L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (Grant numbers: ZR2025MS810 and ZR2021ME200).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yinghao Zhao was employed by the company Shandong Province Metallurgical Engineering Corporation Limited. Author Chao Ding was employed by the company Energy Technologies Area, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Carvel, R.; Marlair, G. A history of fire incidents in tunnels. In The Handbook of Tunnel Fire Safety; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.X.; Ge, F.L.; Ding, L.; Ji, J.; Zhou, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, F. Full-scale experimental and numerical study of smoke spread characteristics in a long-closed channel with one lateral opening. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnermark, A.; Hugosson, J.; Ingason, H. Fire Incidents During Construction Work of Tunnels–Modelscale Experiments; SP Report 2010; SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden: Borås, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.X.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.H.; Ding, C.; Zhao, S.Z.; Yu, W.; Li, L.Y.; Zhou, X.X. Experimental investigation on maximum ceiling temperature and longitudinal attenuation in a closed tunnel with an inclined shaft. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 208, 109484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Qiu, M.X.; Zhao, Y.H.; Ding, C.; Yu, W.; Zhao, S.Z.; Li, L.Y.; Liu, J. Experimental study on vertical temperature distribution of the two-layer smoke flow in tunnel during construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 136, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Z.; Li, Y.Z.; Lönnermark, A.; Ingason, H.; Cheng, X.D. Study of tunnel fires during construction using a model scale tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 89, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Z.; Wang, R.; Xia, Z.Y.; Ren, F.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhu, H.Q.; Cheng, X.D. Numerical study of the characteristics of smoke spread in tunnel fires during construction and method for improvement of smoke control. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.G.; Li, A.Y.; Mu, Y.; Guo, F.Y.; Ji, J. Smoke movement characteristics under stack effect in a mine laneway fire. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 110, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.P.; Fernando, A.; Luo, M.C. Determination of interface height from measured parameter profile in enclosure fire experiment. Fire Saf. J. 1998, 31, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; He, Q.; Shi, Q. Experimental study on thermal smoke layer thickness with various upstream blockage-fire distances in a longitudinal ventilated tunnel. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 170, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.H.; Ji, J.; Fan, C.G.; Li, L.J.; Sun, J.H. Determination of smoke layer interface height of medium scale tunnel fire scenarios. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 56, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Zhao, J.M.; Liu, Q.L.; Chen, H.G.; Liu, Y.H.; Geng, Z.Y.; He, L. Experimental investigation on smoke spread characteristics and smoke layer height in tunnels. Fire Mater. 2019, 43, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.K. Determination of the Smoke Layer Interface Height for Hot Smoke Tests in Big Halls. J. Fire Sci. 2009, 27, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.Y.; Harkleroad, M.; Quintiere, J.; Rinkinen, W. An Experimental Study of Upper Hot Layer Stratification in Full-Scale Multiroom Fire Scenarios. J. Heat Transf. 1982, 104, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.M.; Chen, C.J.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, M.H.; Lin, T.H. Determinations of the fire smoke layer height in a naturally ventilated room. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 58, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Mao, S.; Hu, L.; Wu, L. An improved algorithm for smoke layer identification in building fire condition. In Proceedings of the 2011 Eighth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2011; pp. 410–413. [Google Scholar]

- Tanno, A.; Oka, H.; Kamiya, K.; Oka, Y. Determination of smoke layer thickness using vertical temperature distribution in tunnel fires under natural ventilation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 119, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xu, Z.S.; Markert, F.; Zhao, J.M.; Xie, E.; Liu, Q.L.; Tao, H.W.; Marcial, S.T.S.; Wang, Z.H.; Fan, C.G. Study on the effect of tunnel dimensions on the smoke layer thickness in naturally ventilated short tunnel fires. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 112, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Zhou, X.D.; Xu, Q.K.; Yang, L.Z. The inclination effect on CO generation and smoke movement in an inclined tunnel fire. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2012, 29, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Z.; Li, Y.Z.; Ingason, H.; Liu, F. A theoretical and experimental study on the buoyancy-driven smoke flow in a tunnel with vertical shafts. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 141, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Li, Y.H.; Zheng, Z.J.; Tai, C.M.; Zhang, L.H. Experimental study on the effect of makeup air inlets height on the fire combustion and smoke diffusion. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 104951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, N.; Rauwoens, P.; Merci, B. Verification of the accuracy of CFD simulations in small-scale tunnel and atrium fire configurations. Fire Saf. J. 2011, 46, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.C.; Xiong, K.; Liu, F.; Xie, J. Improved temperature-based methods and deep learning-based method for identifying the smoke layer height in tunnel with longitudinal ventilation. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 252, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D. Inversion of tunnel fires using limited monitored temperature data based on transfer learning approach and full-scale scenario applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Ingason, H. Heat release rate measurements of burning mining vehicles in an underground mine. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 61, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Watanabe, N.; Hagimoto, Y.; Chigira, T.; Masano, R.; Miura, H.; Ochiai, S.; Satoh, H.; Tamura, Y.; Hayano, K.; et al. Burning behavior of sedan passenger cars. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.; Hostikka, S.; McDermott, R.; Floyd, J.; Weinschenk, C.; Overhold, K. Fire Dynamics Simulator User’s Guide. NIST Spec. Publ. 2013, 1019, 1–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, F.; Weng, M.C.; Zeng, Z. A numerical study on smoke movement in a metro tunnel with a non-axisymmetric cross-section. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 73, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M.; Tran, H.C. Data deduction of room tests for zone model validation. J. Fire Sci. 1992, 10, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, K.M.; Wang, Y.C.; Du, X.M. Simulation study on coupled heat and moisture transfer in grain drying process based on discrete element and finite element method. Dry. Technol. 2023, 41, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Chen, J.F.; Qiu, P.Y.; Zhong, M.H. Study on the smoke layer height in subway platform fire under natural ventilation. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.