Abstract

The dead fine fuel moisture content (DFFMC) directly affects forest fire occurrence and spread. Accurate DFFMC prediction is key to estimating forest fire risk and behavior. The well-fitting machine learning (ML)-based meteorological factor regression models are a focus of DFFMC prediction modeling. Nevertheless, this method’s reliance on a considerable amount of training data and limited extrapolation hinders its potential for extensive implementation in practice. To improve the prediction accuracy of the model in the context of limited training data volumes and interspecies and spatial extrapolated predictions, this study proposed a novel DFFMC prediction method based on a knowledge-embedded neural network (KENN). By integrating the partial differential equation (PDE) of the meteorological response of forest fuel moisture content into a multilayer perceptron (MLP), the KENN utilizes prior physical knowledge and posterior observational data to determine the relationship between meteorology and moisture content. Data from Mongolian oak, white birch, and larch were collected to evaluate model performance. Compared with three representative ML algorithms for DFFMC prediction—random forest (RF), long short-term memory networks (LSTM), and MLP—the KENN can efficiently reduce training data volume requirements and improve extrapolation prediction accuracy within the investigated fire season, thereby enhancing the usability of ML-based DFFMC prediction methods.

1. Introduction

Forest fires are foundational events of forest ecosystems, as they alter the forest environments’ composition, structure, and ecological functions [1]. Although fires positively impact forest ecological sustainability, uncontrolled wildfires seriously disrupt forest ecosystem balance and stability, pose significant threats to human life and property, and contribute to climate change through substantial greenhouse gas emissions [2,3]. Forest fuel, which includes litter, duff, and live vegetation, is the material basis for wildfires [4]. Among different kinds of forest fuels, dead fine fuels have the highest surface-area-to-volume ratio, facilitate the advancement of the fire front. Thus, their moisture content directly influences both the potential for fire initiation and the speed at which the fire spreads [5]. As a result, the DFFMC becomes a key parameter for assessing forest fire levels, also making enhancing the accuracy of DFFMC prediction a research focus of investigations in wildfire prevention [6].

Meteorological factors are the direct drivers of DFFMC variations, and identifying the relationship between meteorological variables and moisture content fluctuations is one of the keys to establishing a DFFMC prediction model [7]. Various methods have been proposed to predict DFFMC based on meteorological factors. Among these methods, the meteorological factor regression method is used to construct statistical models to establish the correlation between the meteorological variables and the DFFMC. This method is convenient to model, simple to apply, and widely used in forest fire prevention and control [8]. In the past decade, ML has begun to be applied to meteorological factor regression methods, and its effectiveness has been proven by conducting comparative analysis of the accuracy of moisture content prediction via various ML methods and traditional regression modeling methods [9,10].

While ML-based DFFMC prediction models have shown encouraging predictive accuracy, current data-driven models can only identify statistical relationships between variables and cannot recognize the variables’ causal links. As a result, these models required a substantial volume of training data and demonstrated limited generalizability [11,12]. Meteorological data from forestlands is required as input for DFFMC prediction models. However, in practice, gathering large amounts of forest environmental data can be prohibitively costly due to data transmission in forested areas [13,14]. This difficulty in data acquisition limits the construction of large datasets for ML model training, making it important to improve ML-based DFFMC prediction models’ predictive performance under small training data volume conditions. Furthermore, the moisture content of different kinds of fuels changes in a different pattern under complex forest meteorological conditions. Traditional ML methods cannot generalize as well under unseen data distributions, making it challenging for them to extrapolate effectively across different sampling areas of the same species or between different species [15,16]. Consequently, enhancing ML-based DFFMC prediction models’ extrapolative prediction accuracy is also important for real-world applications.

Recently, combining conventional ML techniques with field knowledge for modelling has become an emerging interdisciplinary research focus [17]. Compared with conventional ML techniques, ML that is combined with field knowledge has shown better performance in generalization and small-data modelling conditions in many studies [18,19]. The ideology of knowledge-ML modeling has also expanded into the agriculture and forestry fields. For example, a physics-based mass-transfer model was woven into a neural network to simulate mass transfer more precisely within plant cells [20]. In another application, a neural network was combined with the inverse scattering integral equation to enhance the detection accuracy of vegetation insect infestations [21]. Furthermore, a more accurate method for estimating plant root density distribution has also been created by embedding the knowledge of plant root water uptake with a basic neural network [22].

When viewed at a microscopic level, the effect of meteorological conditions on fuels can be observed through the slow water vapor adsorption and desorption process, which is driven by the ambient meteorological change. Such dynamic process essentially reflects the DFFMC’s response to time-related meteorological factors and can be abstracted into PDEs with time-space varying parameters and further fusion with ML techniques [23]. Therefore, it is feasible to combine the PDEs that describe the meteorological-DFFMC relationship into the data science architecture to improve the prediction accuracy.

To enhance the accuracy of ML-based DFFMC prediction methods when working with small datasets and to improve extrapolation performance, this study proposes a KENN that incorporates the PDE describing the fuel’s water vapor exchange into an MLP, effectively utilizing both empirical data and prior knowledge to predict DFFMC. To evaluate the effectiveness of our approach, KENN is compared against representative ML-based prediction methods in the field of DFFMC prediction, including RF, LSTM, and MLP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study region is situated in Northeast China, which is recognized as one of the nation’s most significant forest resource bases. Data utilized in this research were collected from two areas: the Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm and the Urban Forestry Demonstration Base. The locations of these sites are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area (Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm and Urban Forestry Demonstration Base).

The Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm of Northeast Forestry University is situated in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province (45°14′–45°29′ N, 127°29′–127°44′ E). A low mountainous and hilly topography characterizes the area’s geomorphology, and the terrain is high in the north and low in the south, with an average elevation of approximately 300 m. In the Köppen and Geiger climate classification system, the area has a temperate continental climate, with rain and heat occurring simultaneously, warm and humid summers, and cold and dry winters. The area experiences an average annual precipitation of 723 mm and evaporation of 1093 mm, with an average annual air temperature of 2.8 °C, a relative humidity of 70%, and a cumulative temperature (≥10 °C) ranging from 2000 to 2500 °C. The vegetation of the forest farm belongs to the Changbai Mountain flora. The original zonal top community is the Korean pine broad-leaved forest. After being destroyed by humans, the original vegetation underwent secondary succession, forming a coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest, leading to the mosaic distribution of natural secondary and manufactured forests.

The Urban Forestry Demonstration Base in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province (45°43′1″–45°43′38″ N, 126°37′49″–126°37′50″ E), is characterized by flat topography. The area experiences a mean annual precipitation of 534 mm, a mean annual air temperature of 3.5 °C, and a mean annual relative humidity of 67%. The base encompasses more than 50 hm2 of diverse planted forest types, with a vegetation coverage exceeding 89% and a forest structure with the typical characteristics of those found in Northeast China.

2.2. Data Collection

Among the main tree species in the Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm, Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb.) and white birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.) are highly flammable due to their dry site conditions, light and loose litter. Larch (Larix gmelinii (Rupr.) Kuzen.) accumulates a thick layer of fallen leaves during autumn and winter. This substantial accumulation of litter contributes to a high surface fuel load. Thus, these three forest types are representative of high-flammability risk forest types in the region. In addition, Mongolian oak, white birch, and larch are representative species of broad-leaved and deciduous coniferous forests in Northeast China. Models based on these three species have strong representativeness and applicability to similar forest environments beyond the study area [24]. Therefore, the surface fine dead fuels of these three tree species were selected as the research subjects.

During the autumn fire prevention period in 2019, meteorological data monitoring equipment with temperature, humidity, air pressure, and wind speed detection functions was deployed in the three aforementioned forest types within the experimental area. To guarantee the representativeness and coverage of the data collection, five collection apparatuses were evenly distributed across each forest type, forming a total of fifteen data collection sites. Meteorological data were collected at hourly intervals from October 1 to 31, covering the entire autumn peak fire season of the study area.

At each monitoring site, three sampling points were established near the device. Simultaneously with meteorological data acquisition, destructive sampling was conducted hourly to collect fine dead fuels from each sampling point. At each sampling point, 100 ± 5 g of a fuel mixture (consisting of fallen leaves and branches < 6 mm in diameter) was collected into Ziplock bags and transported to the laboratory for wet weight (MH) determination. The collected fuels were subsequently oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h to determine the dry weight (MD). To prevent the influence of dew or condensation on the wet weight measurements, surface moisture was removed before weighing the samples. The fuel moisture content (M) was then calculated via Equation (1) [25,26]. The average moisture content of three samples at each site was used for further analysis.

For the Urban Forestry Demonstration Base, during the 2024 autumn fire prevention period, one data collection site was established for each of three tree species: Q. mongolica, B. platyphylla, and L. gmelinii, to record hourly measurements of fuel moisture content and meteorological variables. These sites were designed and operated following procedures closely modeled on those used at the Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm, enabling direct comparison between the two locations.

2.3. KENN for DFFMC Prediction

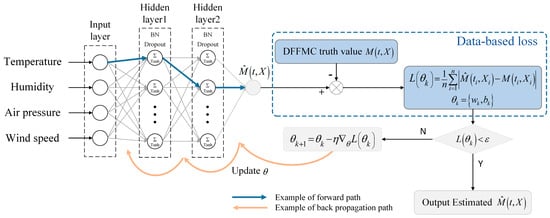

2.3.1. Multilayer Perceptron

An MLP is a general-purpose network that serves as the fundamental structure of numerous neural network variants. It can accurately fit nonlinear models and is widely used for natural environment variable prediction tasks. Therefore, an MLP was chosen as the foundational architecture for the KENN developed in this study. Figure 2 illustrates the specific MLP structure employed. The network’s input layer receives the collected temperature, humidity, air pressure, and wind speed data and transmits them to the hidden layer. The tanh activation function in each fully connected layer enables the network to learn nonlinear relationships between variables, capturing the complex relationships between meteorological factors and moisture content. Additionally, batch normalization and dropout mechanisms were incorporated after the fully connected layers to mitigate the risk of overfitting in the network. Finally, the network uses a fully connected layer with one node in the role of output layer to generate the predicted DFFMC.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the prediction model based on the MLP. Where M(ti,Xi) is the DFFMC under meteorological data X at time t, n is the number of meteorological-DFFMC groups included in the dataset, θk is the network parameter (including weights w and bias b) of iteration k, L(θk) is the loss function, ε is the target value for the training error, and is the predicted DFFMC.

The MLP affects the output results by adjusting nodes’ weights and biases. The weights determine the influence of each input feature on the output, and the biases adjust the nodes’ activation thresholds. Equation (2) illustrates how a single node in the first hidden layer computes its output.

where y is the value of the node output, xi is the meteorological variable input to the network, wi is the weight of the corresponding single variable in the node, and b is the bias of the node. The weight and bias are initialized using Xavier initialization. The network can learn the mapping relationships between meteorological variables and moisture content by adjusting these two parameters. The network loss function L(θk) quantifies the discrepancy between the network output value and the actual observed data. This discrepancy is obtained by calculating the average absolute error between predicted moisture content and the DFFMC ground truth M:

During network training, the gradient of the loss function with respect to the weights and biases is calculated. By updating these parameters in the opposite direction of the gradient, the network iteratively reduces the discrepancy between the predicted and actual moisture content, driving the output toward the true value.

2.3.2. Knowledge of Meteorological Driving Changes in DFFMC

Vapor pressure gradients directly influence the fuel moisture content by driving vapor exchange between dead fuel and ambient air [27]. Fuel vapor exchange involves two processes: surface water exchange and internal diffusion. For dead fine fuel, which has a small diameter, its fuel surface moisture content adjusts instantaneously to maintain equilibrium with the surroundings. This equilibrium point, where there is a zero vapor pressure gradient between the fuel and the air, defines the equilibrium moisture content (EMC). From the above diffusion theory, the following differential equation approximates the adsorption and desorption processes of dead fine fuel [28]:

where M is the moisture content of the fuel (%), E is the EMC (%), and τ is the time lag of the fuel (h), which governs the rate at which the moisture content approaches the EMC.

The EMC can be expressed as a function of temperature and humidity, connecting measurable environmental variables and vapor exchange processes. On the basis of Gibbs free energy theory, Nelson proposed a semi-physical model for analyzing the relationships between meteorological factors and EMC [29]:

where R = 8.314 J mol−1 is the universal gas constant; T is the air temperature (K); H is the relative humidity (%); Mwater = 18.015 g mol−1 is the molecular mass of H2O; and α and β are model parameters determined via regression analysis of experimental equilibrium moisture content data. By substituting Equation (5) into Equation (4), an expression is derived to represent the moisture adsorption and desorption characteristics of dead fine fuel under varying temperature and humidity conditions:

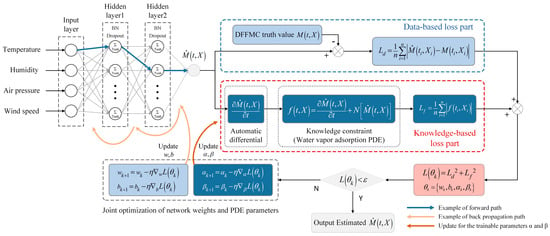

2.3.3. Knowledge-Embedded Neural Network

Building upon conventional neural networks, which only learn relationships between variables from input and output data, the KENN incorporates prior knowledge in the form of PDE as soft constraints, enhancing their ability to extract information from data. The designed KENN iteratively optimizes the network parameters θ under the constraints of both predicted and true value discrepancies and physical knowledge. The loss function L(θk) of the KENN consists of two parts: the data error term Ld(θk) and the knowledge error term Lf(θk). The data error term allows the network to fit the data to the greatest extent possible, and it is calculated similarly to the loss function of the MLP. The knowledge error term encodes information about how meteorological factors affect moisture content to the network, quantifies the deviation in the network output and the embedded domain knowledge, and serves as the fundamental source of soft constraints.

The response of the DFFMC to environmental factors can be expressed as:

where m(t,X) is the implicit solution of Equation (4) and N[m(t,X)] represents various nonlinear operations performed on m(t,X). The structure of the multilayer network can be regarded as a universal function approximator with powerful function expression ability. The output DFFMC result can be used to approximate m(t,X). As a result, the knowledge constraint of the network is set as shown in Equation (8):

where operator N is the non-linear mapping function that operates on the predicted DFFMC . According to Equation (6), the specific form of the knowledge constraint term of the network is as follows:

The knowledge error term Lf of the network is obtained by calculating the mean absolute error of the knowledge constraint term f(t,X):

To balance the data error term and the knowledge error term, the loss function is set as:

The squaring operation of the two error terms in the loss function enhances the contribution of the error term with a larger value to the loss function, thereby prioritizing the reduction of larger errors during training. Furthermore, the continuous and differentiable nature of the loss function guarantees the smoothness of the optimization process, facilitating efficient convergence of the optimization algorithm. In summary, the KENN-based DFFMC prediction model proposed in this study is illustrated in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Schematic of the prediction model based on the KENN.

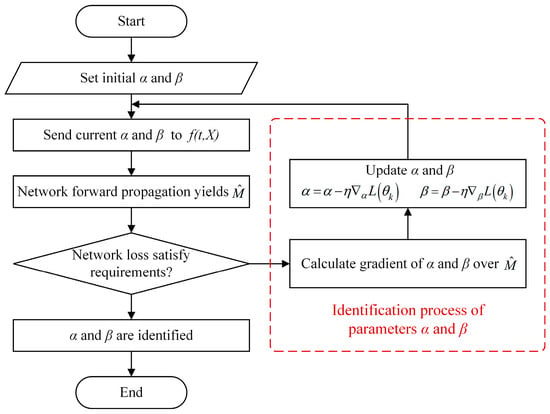

The undetermined parameters α and β are calculated via regression in the traditional equilibrium moisture content model. However, in the knowledge constraint term, these two parameters are part of the differential equation, making it challenging to obtain their values via simple regression calculations. In this study, the KENN uses an updating method similar to that of neural network weights and bias parameters. It uses automatic differentiation to obtain the gradient of the loss function with respect to these two unknown parameters and iteratively updates them via gradient descent to approximate their true values and identify the undetermined parameters in the knowledge constraint term. The identification process of parameters α and β is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the identification process of the undetermined parameters of the knowledge loss terms.

2.3.4. Model Implementation and Training Details

Both the MLP and KENN models share the same network architecture to allow a fair comparison. The network consists of two fully connected hidden layers, each containing 64 neurons. The tanh activation function is applied to all hidden layers to capture nonlinear relationships between meteorological variables and fuel moisture content. Batch normalization is employed after each hidden layer to stabilize training, followed by dropout with a dropout rate of 0.2 to reduce the risk of overfitting. The output layer is a fully connected layer with a single neuron, producing the predicted DFFMC value. For the knowledge-embedded component, the time-lag parameter τ in the fuel moisture response equation was initialized to 1 h based on the definition of dead fine fuel and was kept constant during training. The parameters α and β were treated as learnable variables, and they were jointly optimized together with the network weights and biases.

Although α and β are optimized together with the network during training, their ranges are constrained based on existing studies by bounding α within the interval [0, 1] and β within [−1, 0], ensuring that their values remain physically admissible throughout the optimized process [30,31,32,33,34]. These constraints prevent the embedded EMC formulation from degenerating into an unconstrained nonlinear transformation and preserve the thermodynamic interpretability of the knowledge constraint. Moreover, it should be noted that α and β enter the optimization process exclusively through the knowledge loss term, rather than directly influencing the data-fitting term. As a result, reductions in the total loss must simultaneously improve agreement with the observed DFFMC data and maintain consistency with domain knowledge, rather than inducing over-smoothing or compromising physical realism beyond the calibration range.

Model training was performed using the Adam optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 1 × 10−3 and was adaptively reduced by using plateau-based learning rate scheduler. The batch size was set to 32. Early stopping was applied with a patience of 20 epochs to prevent overfitting and unnecessary training.

2.4. Model for Comparison

To evaluate the effectiveness of the constructed KENN, representative ML-based algorithms in DFFMC prediction field were selected for comparison. The RF algorithm is a classic algorithm widely used for predicting forest fuel moisture content and has demonstrated high accuracy in numerous studies [9,10,35]. Hence, RF was selected for comparison. In addition, LSTM networks are the latest mainstream network algorithms in DFFMC prediction. In previous studies, LSTM networks have also demonstrated superior moisture content prediction accuracy compared with other ML methods [36,37]. Therefore, LSTM was selected as another algorithm for comparison. Furthermore, the MLP mentioned above was also included to provide a clearer comparison of the effect of embedding knowledge constraints on network prediction performance.

2.4.1. Random Forest

RF is an ensemble learning algorithm that discerns both linear and nonlinear relationships by training multiple decision tree estimators and integrating the outcomes of estimators. RF uses the guided resampling method to extract multiple samples from the original sample. Each decision tree is modeled on different guided samples, and then the final prediction result is obtained through voting or other methods.

2.4.2. Long Short-Term Memory Network

The LSTM network represents a variant of the RNN structure. Meteorological-DFFMC content data exhibit typical time series characteristics. In contrast to the conventional RNN, the gating mechanism of the LSTM network considers different distance information in the time series, allowing it to capture the temporal dependency and sequence relationships inherent in data effectively and facilitating the efficient mining of associations between the current and preceding input factors. In this study, the LSTM was implemented in a lightweight configuration to maintain a parameter count comparable to the MLP and KENN, thereby enabling a controlled comparison. Crucially, this design also lower the risk of overfitting associated with employing excessive trainable parameters, especially in the small-data and challenging extrapolation scenarios targeted in this work. Given the pronounced 24 h diurnal periodicity observed in forest litter moisture content, the look-back window was set to 24 h to ensure the input sequence fully encompasses one complete cycle of environmental fluctuations.

2.5. Model Evaluation

2.5.1. Test Items

First, to evaluate the performance of the conventional DFFMC prediction task with sufficient training data and without extrapolation, four ML methods, as mentioned earlier, were employed to model and predict data from all fifteen monitoring sites across three tree species.

Second, to evaluate the model’s performance under small data volume modeling, data from each monitoring site were sampled at equal intervals to one-half, one-third, one-quarter, one-fifth, and one-tenth of the full dataset size. This resulted in sub-datasets with varying sparsity levels, which were used to train the models. After model establishment, DFFMC predictions were made on the complete full-capacity dataset to evaluate the predictive performance of models built with small amounts of data.

Third, model extrapolation experiments can be divided into intraspecies extrapolation and interspecies extrapolation for evaluation. For intraspecies extrapolation, data from all fifteen monitoring sites were modeled separately, resulting in five models for each of the three species. The data from each monitoring site were input into the models of the other four monitoring points within the same tree species to facilitate intraspecies extrapolation prediction. When interspecies extrapolation is carried out, three monitoring sites are selected for each species. Data from each of these nine sites were used to predict DFFMC values via models trained on data from the remaining six sites of the other two species.

All three of the aforementioned tests were based on data collected at the Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm, while a fourth test, designed to further assess the generalization capability of the proposed method, utilized data from the Urban Forestry Demonstration Base. As the latter dataset included only one monitoring site for each tree species, intraspecies extrapolation was not performed.

Additionally, to separate genuine physical benefit from extra-parameter flexibility, we conducted an ablation experiment comparing three models: MLP, KENN, and KENN-fixed. In KENN-fixed, the parameters α and β are fixed to values obtained from the widely used Catchpole’s method [34], rather than being optimized during training. These models were tested across all the scenarios mentioned above.

To reduce the impact of randomness in machine learning, improve the reliability of the evaluation results, and better reflect model performance, all models underwent ten independent repetitions of training and prediction in each test, and the results were then averaged. For all tests, the rolling window strategy was adopted rather than random sampling. Specifically, the training data always temporally preceded the test data, and no future observations were used for model training, ensuring forward extrapolation. In the small data volume modeling test, sparse datasets were first constructed by uniformly subsampling the original hourly time series at fixed temporal intervals, thereby preserving chronological order while increasing the temporal separation between consecutive samples. After this temporal subsampling, the training and test sets were generated using the rolling window scheme, with the test period always occurring after the training period. This procedure avoids placing neighboring observations from the original hourly sequence into different training and test partitions and substantially mitigates the risk of temporal leakage caused by autocorrelation.

2.5.2. Evaluation Metrics

The mean absolute error (MAE) calculates the average of the absolute values of the prediction errors of each sample, directly reflecting the degree of deviation between the predicted DFFMC value and the true value, and intuitively reflects the overall performance of the model. Additionally, extreme deviations in the predicted DFFMC could seriously affect fire management strategies, and significant prediction errors should be avoided. Therefore, to complement the MAE and address the potential impact of large errors, the root mean square error (RMSE), which is more sensitive to high error values, is introduced as an evaluation indicator to measure model performance. The methods used to calculate the MAE and RMSE are shown in Equations (12) and (13):

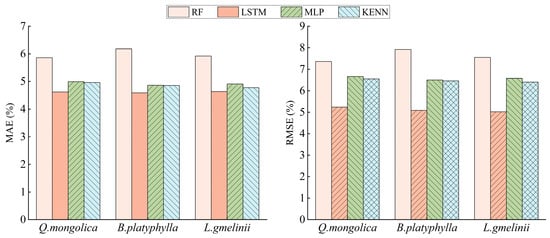

3. Results

When using full-volume data training for each ML model for the conventional DFFMC prediction task, the prediction performance of each model for different tree species is as illustrated in Figure 5. The prediction error of RF is significantly greater than that of the other methods, and its MAE and RMSE exhibit notable discrepancies from those of the other three models. The MAEs of the LSTM prediction are comparable to those of the MLP and KENN, but the RMSE is lower than those of the aforementioned two methods. The predictive performances of the MLP and KENN are comparable, with the MAEs and RMSEs of the KENN model for each tree species exhibiting lower values than those of the MLP model. This suggests that incorporating field knowledge can enhance the model’s predictive capacity.

Figure 5.

Comparison of errors for each ML method in the conventional DFFMC prediction task, the performance metric value for each tree species was calculated based on the average results of its five sampling points.

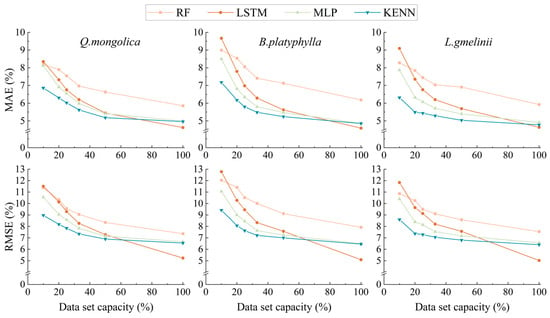

Figure 6 shows the DFFMC prediction performance of the four ML methods when different data volume levels are used for modeling. As the volume of data utilized for model training decreases, the MAE and RMSE of each model tend to increase. The results demonstrate that the RF has the poorest prediction accuracy across almost all the capacity training datasets. The LSTM model exhibits optimal prediction accuracy when trained on full-volume data. However, the prediction accuracy of LSTM significantly deteriorates when the dataset capacity is reduced. When trained on one-tenth of the original data, the LSTM’s error even exceeds that of the RF under the same training data conditions. Except for the case of the full dataset volume, compared with the other ML methods, the KENN method has superior DFFMC prediction accuracy. When one-tenth of the complete dataset was used for training, taking the model established by the MLP as the baseline, the MAEs of the KENN in predicting the moisture contents of Q. mongolica, B. platyphylla, and L. gmelinii decreased by 15.51%, 15.54%, and 19.71%, respectively. The RMSE decreased by 14.97%, 14.81%, and 17.18%, respectively. This result indicates that embedding field knowledge into a neural network effectively enhances its ability to extract information from limited data.

Figure 6.

Prediction error of each ML method when trained with different data volumes.

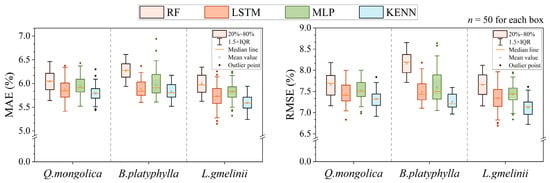

For the intraspecies extrapolation test, the DFFMC prediction errors of each ML method are shown in Figure 7. Judging from the average MAE and RMSE, the prediction errors of the models under each tree species are in the order RF > MLP > LSTM > KENN. This reflects the accuracy advantage of the KENN in terms of extrapolation between monitoring sites of the same tree species. From the perspective of error distribution, the KENN model shows more concentrated MAE and RMSE distributions, suggesting greater stability in its intraspecies extrapolated predictions.

Figure 7.

Errors in the extrapolation prediction between different monitoring sites of the same tree species via each method.

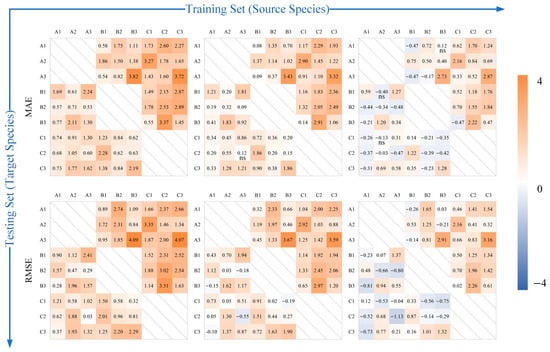

For the interspecies extrapolation test, the percentage improvement in the prediction performance of the KENN compared with that of the other models is shown in Figure 8. Compared with RF and LSTM, the KENN demonstrated superior prediction accuracy in nearly all extrapolation combinations. The results demonstrated that KENN has better interspecies extrapolation prediction accuracy than these two methods. Furthermore, KENN exhibited enhanced accuracy in moisture content prediction in more than half of the combinations compared with the MLP, proving that embedding of knowledge can enhance a network’s interspecies extrapolation prediction ability.

Figure 8.

Percentage error reduction of the KENN compared to the other three methods when interspecies extrapolation is performed. Models are trained on data from sites along the horizontal axis and tested on data from sites along the vertical axis. The tree species represented are A (Q. mongolica), B (B. platyphylla), and C (L. gmelinii), each with data from three different sites. The number within each block represents the percentage improvement of the KENN over the corresponding ML method under the same testing conditions. Statistical significance was assessed per cell using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test on MAE across repeated runs (one-sided). Cells with corrected p ≥ 0.05 are marked as ‘ns’, whereas cells without the ‘ns’ label satisfy p < 0.05.

For the data collected at the Urban Forestry Demonstration Base, the performance evaluation metrics of each model for the conventional, small-data volume (half of the full dataset), and interspecies extrapolation prediction tasks are shown in Table 1. The results are generally consistent with those obtained from the aforementioned Maoershan Experimental Forest Farm dataset.

Table 1.

The evaluation metrics of each model on the Urban Forestry Demonstration Base dataset under conventional, small data volume, and interspecies extrapolation prediction tasks.

For the ablation experiment, the DFFMC prediction errors of MLP, KENN, and KENN-fixed are shown in Table 2. The results show that KENN-fixed consistently outperforms MLP and is close to KENN across all test items, demonstrating that the integration of domain knowledge through the PDE constraint enhances the model’s predictive accuracy, even when the parameters α and β are fixed. This also confirms that the improved accuracy of KENN is not solely due to the extra-parameter flexibility, but rather from the benefit of domain knowledge. Moreover, KENN achieves the best performance in all cases. This suggests that the additional flexibility in adjusting α and β allows the model to better adapt to species-specific fuel moisture characteristics, further enhancing prediction accuracy.

Table 2.

The evaluation metrics of DFFMC prediction errors of MLP, KENN, and KENN-fixed.

4. Discussion

When full-volume data are employed for modeling and performing conventional DFFMC predictions without extrapolation, the RF exhibits the weakest ability to extract data features relative to the other three network-based methods, resulting in the largest prediction error. LSTM takes into account the data’s time series characteristics. Compared with the MLP and KENN, which are also network-based methods, the LSTM excels at identifying and learning the evolving patterns within the DFFMC sequence, achieving superior prediction accuracy. The predictive efficacy of the KENN for the moisture content of diverse tree species is surpassed only by that of the LSTM, demonstrating the viability of the KENN for DFFMC prediction. Apart from the loss function, the MLP and KENN share consistent architectures, including the number of layers and nodes. With sufficient training data for non-extrapolation prediction, these two methods achieve comparable prediction accuracies for moisture content. Furthermore, based on the MLP, the KENN incorporates the relationship between DFFMC and meteorological factors into the network as a knowledge constraint term, thus enabling the network to simultaneously utilize both observed data and prior knowledge to express the relationship between meteorology and moisture content, enhancing the prediction accuracy while maintaining the same network architectural parameters.

When modeling with small-volume data, the KENN demonstrated superior DFFMC prediction accuracy compared with other methods. This accuracy advantage of the KENN is positively correlated with the sparsity of the dataset, confirming that KENN requires less training data than other ML methods for accurate modeling. The primary distinction between the KENN and conventional neural networks lies in the incorporation of field knowledge into the loss function. In the loss function designed for this study, two undetermined parameters are introduced when the EMC calculation method based on Gibbs free energy theory is employed. These two parameters are updated concurrently with the network’s weights and biases, effectively embedding knowledge of both the modeling dataset and the underlying physics of fuel water vapor adsorption and desorption processes, Forming a semi-physical model similar to the direct estimation method [34], thereby reducing the demand for data volume during modeling.

For intraspecies extrapolation predictions, the KENN demonstrated the most precise predictive accuracy in the test of all tree species, proving that incorporating field knowledge can enhance the network’s extrapolation performance in predictions within the same tree species. Under soft constraints on field knowledge, the KENN not only minimizes the discrepancy between the predicted DFFMC values and actual DFFMC values but also improves the model’s physical consistency, enabling it to leverage the implicit physical meaning within the data while approximating the dataset. By incorporating prior meteorological knowledge into the data-driven neural network, the KENN avoids overfitting by considering actual physical meaning, leading to superior accuracy in intraspecies extrapolation DFFMC prediction. Furthermore, KENN’s constraints on embedded knowledge limit the range of possible weight and bias updates, focusing the network’s predictions within a narrower error range. This increased reliability aligns with the observation that KENN intraspecies extrapolation errors are the most concentrated.

For interspecies extrapolation predictions, the accuracy of the KENN is higher than that of RF and LSTM in the overwhelming majority of cases. As a network-based ML method, the KENN is superior to the RF in identifying the mapping relationship between meteorology and moisture content derived from data, enabling it to achieve more accurate predictions. Different tree species have varied meteorological-DFFMC response characteristics, making the time series change pattern of the modeled data, as learned by the LSTM, differ from that of the test data, resulting in the LSTM’s reduced interspecies extrapolation prediction accuracy. The results showed that the KENN outperformed the MLP in the majority of the tests, suggesting that incorporating field knowledge can improve the network’s interspecies extrapolation prediction performance. The slight deterioration in the performance of the KENN to MLP observed in some tests may be attributed to the simultaneous updating of two adjustable parameters in the knowledge constraint term during network training. These two undetermined parameters physically represent the response characteristics of the water vapor adsorption capacity of different fuels to meteorological conditions. The continuous updating of these parameters during modeling with data from a specific fuel allows the model to capture the unique water vapor adsorption characteristics of the fuel. The update direction of the parameters is consistent with the characteristics of the modeled fuel, but the characteristics of different fuels exhibit varying degrees of similarity, which results in discrepancies in the direction and extent of performance changes observed after the network incorporates field knowledge. The embedded PDE in KENN represents meteorological driving mechanisms, rather than explicitly modeling species-specific physiological or structural traits. Consequently, while the PDE-based constraint enforces moisture change across species more reliably, residual extrapolation errors may arise when fuel-specific response patterns differ substantially. Nevertheless, the consistently lower average error and tighter error distributions observed for KENN indicate that incorporating domain knowledge enhances robustness to interspecies variability.

This study focuses on data from the autumn peak fire season in the study area (October 2019). During this month, the vegetation withered naturally, producing a large amount of litter, leading to a significant accumulation of dead fine fuels. Coupled with the dry air and scarce precipitation characteristic of a temperate continental climate, these conditions resulted in an exceptionally high wildfire danger for the month. While this one-month data set is highly representative of the period with the highest wildfire risk, it lacks data on the interaction patterns of meteorology and DFFMC in different seasons. Future research would benefit from incorporating long-term, multi-season datasets to assess the model’s ability to withstand seasonal or inter-annual climatic variability. Moreover, forest fuel behavior varies across ecosystems, the two neighboring forests used in this study are relatively limited, in future research datasets could include more diverse climate zones to improve the model’s applicability and robustness in different regions.

Based on existing research, temperature and relative humidity are found to be the dominant variables, and their combined influence is effective in capturing the primary dynamics of moisture variation. Thus, KENN uses the PDE in Equation (6) as domain knowledge, and it has achieved promising results. However, some factors are not incorporated into the current model, such as rainfall interception, solar radiation, wind speed, precipitation, and litter compaction, which also affect moisture content and drying rates. Considering that these additional variables may enhance the model’s performance, future work could integrate these factors to extend the model’s applicability across more complex weather and fuel conditions. Within this simplified modeling framework, the time-lag parameter τ in the drying equation is treated as a constant. Physically, τ represents the characteristic response time of DFFMC to environmental forcing and varies with wind speed, fuel geometry, and wetting history. By keeping τ fixed, part of the process heterogeneity associated with drying-rate variability is implicitly absorbed into the learned parameters α and β, which inevitably reduces the strict physical interpretability of the embedded constraint. Under windy (>3 m s−1) or rainy (>5 mm h−1) conditions, fixing τ may leads to a systematic but secondary increase in RMSE relative to calm and dry conditions. This indicates a systematic yet moderate limitation of the constant-τ assumption under rapidly varying moisture regimes. Nevertheless, the knowledge component of KENN is not intended to represent a fully mechanistic drying model, but rather to provide a soft physical prior that facilitates knowledge consistency. The results indicate that, despite this approximation, the embedded constraint improves model stability and extrapolation performance compared with purely data-driven approaches. Allowing τ to vary dynamically, such as a condition-dependent or learnable parameter, represents a meaningful direction for future work to further enhance physical interpretability and extrapolation robustness.

It should be noted that the proposed KENN provides point predictions of DFFMC and does not quantify predictive uncertainty. Fuel moisture dynamics are uncertain due to the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the environment and the fuel itself. In this study, model performance is characterized by average prediction accuracy but does not give uncertainty bounds for individual predictions. In future study, uncertainty quantification can be conducted to quantify the error band, making KENN more reliable in wildfire management and decision-making.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed a modeling method for predicting forest DFFMC based on a KENN. By integrating the PDE of the meteorological response of forest fuel moisture content into the network’s loss function, we embed physical knowledge about the relationship between fuel moisture fluctuations and meteorological conditions into the network. This approach allows the network to be constrained by both modeling data and domain knowledge, utilizing prior physical knowledge and posterior observational data to determine the relationship between meteorology and moisture content, achieving more efficient mapping from meteorological factors to the DFFMC. Compared with the network before embedding field knowledge (MLP), the KENN method can reduce the amount of data required for modeling and improve the extrapolation prediction accuracy of the model, proving the effectiveness of embedding knowledge to improve the DFFMC prediction performance of the network. Furthermore, compared with typical ML methods, the KENN demonstrates superior DFFMC prediction accuracy in modeling with limited data and extrapolation prediction, thus offering novel insights for precise ML-based prediction of forest DFFMC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H. and J.H.; methodology, Z.H. and J.H.; software, C.M., Q.L. and C.L.; validation, Z.H., C.M., Q.L., C.L. and Y.L.; formal analysis, Z.H. and J.H.; investigation, Z.H.; resources, J.H. and J.Z.; data curation, Z.H., C.M. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and J.Z.; visualization, C.M. and Q.L.; supervision, J.H. and J.Z.; project administration, J.H. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Central Financial Forestry Science and Technology Promotion Demonstration Project, grant number HEI [2023]TG25.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFFMC | Dead Fine Fuel Moisture Content |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| KENN | Knowledge-Embedded Neural Network |

| PED | Partial Differential Equation |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| RF | Random Forest |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Networks |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

References

- McLauchlan, K.K.; Higuera, P.E.; Miesel, J.; Rogers, B.M.; Schweitzer, J.; Shuman, J.K.; Tepley, A.J.; Varner, J.M.; Veblen, T.T.; Adalsteinsson, S.A.; et al. Fire as a Fundamental Ecological Process: Research Advances and Frontiers. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 2047–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, J.M.; Whiteside, M. California Wildfires: Role of Undisclosed Atmospheric Manipulation and Geoengineering. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2018, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, J.K.; Balch, J.K.; Barnes, R.T.; Higuera, P.E.; Roos, C.I.; Schwilk, D.W.; Stavros, E.N.; Banerjee, T.; Bela, M.M.; Bendix, J.; et al. Reimagine Fire Science for the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Nexus 2022, 1, pgac115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.C.; Bowman, D.M.; Bond, W.J.; Pyne, S.J.; Alexander, M.E. Fire on Earth: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, S.J.; Andrews, P.L.; Laven, R.D. Introduction to Wildland Fire; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Q.; Hu, T. Advances in Research on Prediction Model of Moisture Content of Surface Dead Fuel in Forests. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 2021, 57, 142–152. Available online: http://www.linyekexue.net/CN/10.11707/j.1001-7488.20210415 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Matthews, S. Dead Fuel Moisture Research: 1991–2012. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2014, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H. Meteorological Elements Regression Method Is Used to Predict Pangu Forest Farm Extrapolation Accuracy Analysis of Fuel Moisture Content. J. Central. South Univ. Technol. 2016, 36, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Hu, T.; Ren, J.; Liu, Q.; Sun, L. A Comparison of Five Models in Predicting Surface Dead Fine Fuel Moisture Content of Typical Forests in Northeast China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1122087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Won, M.; Yoon, S.; Jang, K. Estimation of 10-Hour Fuel Moisture Content Using Meteorological Data: A Model Inter-Comparison Study. Forests 2020, 11, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Kwok, J.T.; Ni, L.M. Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, N.; Huber, M.F. A Survey on the Explainability of Supervised Machine Learning. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2021, 70, 245–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, J.; Dai, G.; Li, X.-Y.; Gu, M.; Ma, H.; Mo, L.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Long-Term Large-Scale Sensing in the Forest: Recent Advances and Future Directions of Greenorbs. Front. Comput. Sci. China 2010, 4, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.E.; Ortiz, F.M.; Costa, L.H.M.; Foubert, B.; Amadou, I.; Mitton, N. A Study of the LoRa Signal Propagation in Forest, Urban, and Suburban Environments. Ann. Telecommun. 2020, 75, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, Q.; Yi, J.; Liu, J. Predictive Model of Spatial Scale of Forest Fire Driving Factors: A Case Study of Yunnan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Dou, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, S. Effects of Extrapolation between Self-Built Models on Forecast Model Accuracy of Moisture Contents. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2018, 46, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Cola, V.S.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific Machine Learning through Physics–Informed Neural Networks: Where We Are and What’s next. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-Informed Machine Learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, A.; Karpatne, A.; Watkins, W.D.; Read, J.S.; Kumar, V. Physics-Guided Neural Networks (Pgnn): An Application in Lake Temperature Modeling. In Knowledge Guided Machine Learning; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Batuwatta-Gamage, C.P.; Rathnayaka, C.; Karunasena, H.C.; Jeong, H.; Karim, A.; Gu, Y.T. A Novel Physics-Informed Neural Networks Approach (PINN-MT) to Solve Mass Transfer in Plant Cells during Drying. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 230, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, H.; Xia, B.; Wu, Y.; Shi, J. Tree Internal Defects Detection Method Based on ResNet Improved Subspace Optimization Algorithm. NDT E Int. 2024, 147, 103183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzoglou, K.; Papadimitriou, C.; Bontozoglou, V.; Ampountolas, K. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Parameter Learning of Wildfire Spreading. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 434, 117545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Appling, A.; Gentine, P. Differentiable Modeling to Unify Machine Learning and Physical Models and Advance Geosciences. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, W.; He, H.; Bu, R.; Hu, Y. The Spatial Distribution of Constructive Species of Northeast Forest under the Climate Changing. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2006, 12, 4257–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4442-20; Standard Test Methods for Direct Moisture Content Measurement of Wood and Wood-Based Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S. Effect of Drying Temperature on Fuel Moisture Content Measurements. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2010, 19, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, N. A Review of Fine Fuel Moisture Modelling. Int. J. Wildland Fire 1991, 1, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, G.M.; Nelson, R.M. An Analysis of the Drying Process in Forest Fuel Material; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.M., Jr. A Method for Describing Equilibrium Moisture Content of Forest Fuels. Can. J. For. Res. 1984, 14, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Yu, H.; Jin, S. Predicting Hourly Litter Moisture Content of Larch Stands in Daxinganling Region, China Using Three Vapour-Exchange Methods. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2015, 24, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P. Study on the Diurnal Dynamic Changes and Prediction Models of the Moisture Contents of Two Litters. Forests 2020, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Lu, J.; Zhang, J. Risk Assessment Using Transfer Learning for Grassland Fires. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 269, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijepcevic, A.; Anderson, W.R.; Matthews, S. Testing Existing Models for Predicting Hourly Variation in Fine Fuel Moisture in Eucalypt Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 306, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, E.A.; Catchpole, W.R.; Viney, N.R.; McCaw, W.L.; Marsden-Smedley, J.B. Estimating Fuel Response Time and Predicting Fuel Moisture Content from Field Data. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2001, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinda, M.M.; Li, F.; Liu, Q.; Sun, L.; Hu, T. Prediction Model of Moisture Content of Dead Fine Fuel in Forest Plantations on Maoer Mountain, Northeast China. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 2023–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; He, B. A Physics-Guided Deep Learning Model for 10-h Dead Fuel Moisture Content Estimation. Forests 2021, 12, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Zhang, J.; Xing, J.; Liu, J.; Li, M. Measuring Moisture Content of Dead Fine Fuels Based on the Fusion of Spectrum Meteorological Data. J. For. Res. 2022, 34, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.