Abstract

The rapid growth of electric vehicles (EVs) has introduced new fire safety challenges for the built environment, particularly within reinforced concrete structures. Fires involving lithium-ion batteries are substantially different from conventional hydrocarbon-fuelled fires due to their rapid heat escalation, extended burning duration, and potential for re-ignition caused by thermal runaway. This study assesses the adequacy of existing fire design standards in addressing these emerging hazards, emphasising the spalling behaviour of concrete under EV induced fire exposure. The study found that concrete structures are highly vulnerable to spalling when exposed to EV fires, as the typical temperatures initiating concrete spalling are significantly lower than the extreme temperatures and re-ignition produced during an EV battery fire. Moreover, the evidence suggests that EV fires can sustain peak temperatures exceeding 1000 °C in a short period, which exceeds the assumptions underlying standard fire curves, such as ISO 834. A comparative assessment of the National Construction Code (NCC 2022) and standards (i.e., AS 1530.4, EN 1992-1-2) reveals that current design methodologies and fire-resistance ratings underestimate the severity and duration of EV fire conditions. This study also proposes code-aligned improvements and a performance-based evaluation framework that integrates empirical EV fire curves. The findings highlight a pressing need to re-examine fire design provisions and update thermal exposure assumptions to ensure that reinforced concrete infrastructure remains structurally safe and reliable as EV adoption increases.

1. Introduction

The global electric vehicle (EV) fleet is experiencing exponential growth. For instance, sales of EVs in 2024 are expected to reach 17 million, representing a nearly 25% increase from the previous year [1]. This accounts for nearly 17% of vehicles on the road [2]. To accommodate the accelerating growth, supporting facilities such as charging infrastructure must be developed, particularly within parking areas, including basement garages and multi-storey car parks. This creates new demands on the parking structure beyond vehicle parking. The structure needs to sustain the electrical loads, charger equipment, altered vehicle distribution, possibly higher vehicle weights, and, most importantly, the fire or thermal issues associated with it [3]. The fire hazard originates from the high-energy lithium-ion battery packs used in most EVs, which contain flammable electrolytes and are susceptible to a self-propagating failure known as thermal runaway [4]. During such events, an overheated or damaged cell triggers neighbouring cells, releasing intense heat and toxic gases that can lead to large-scale fires that are difficult to extinguish [5].

The primary triggers of EV fires include mechanical damage, internal short circuits, overheating, improper charging, and environmental exposure such as moisture or flooding. A study conducted in the USA by Hasan et al. [6] shows that EVs account for only 2% of vehicular fires. Although the overall frequency remains relatively low compared to conventional vehicles, their severity, duration, and re-ignition potential make them disproportionately hazardous. Reported incidents worldwide have shown that EV fires can reach extremely high temperatures (1200 °C), sustain combustion for extended periods, and often require large quantities of water for suppression. These characteristics not only pose risks to occupants and firefighters but also threaten the structural performance of parking facilities [7]. The majority of electric-vehicle parking and charging stations are integrated within reinforced-concrete structures such as parking ramps, basement garages, and multi-storey car parks. Therefore, their fire performance and the structural integrity of the concrete structure under thermal exposure should be ensured for fire safety. Concrete, while inherently non-combustible, is highly vulnerable to deterioration under extreme fire conditions due to explosive spalling, which exposes and weakens the embedded steel reinforcement [8]. Most current building design standards are derived from traditional hydrocarbon fire curves (e.g., ISO 834 [9]). However, battery fires involve rapid temperature increases, prolonged burning, localised flames, and re-ignition behaviour not explicitly represented in standard fire curves. It remains questionable whether current fire design provisions for reinforced concrete structures adequately represent the thermal exposure, spalling risk, and structural demands imposed by lithium-ion battery-induced EV fires in parking and charging facilities [3]. The current landscape of impacts of EV battery fire on concrete structures remains limited but rapidly expanding. The primary focus of existing studies in this domain is the fire characteristics of EV battery fire scenarios, including the Heat Release Rate (HRR), duration, re-ignition behaviour analysis, and suppression challenges [8,9,10,11]. However, experimental and numerical studies emphasise that lithium-ion battery fires cause prolonged thermal exposure, which has a critical impact on concrete performance [12,13]. Hence, studies assessing the impacts of Li-ion battery fires on concrete structures need to be expanded to include concrete spalling due to EV fires and degradation of material properties, particularly under confined environments such as carparks and tunnels. Since the majority of the existing studies on concrete fire performance are conducted based on hydrocarbon fire scenarios, extensive studies are required to determine the actual concrete damage depth, the severity of spalling, and residual concrete strength after an EV fire [14].

Consequently, this study aims to assess the influence of lithium-ion EV fire dynamics, such as thermal-runaway duration, re-ignition potential, and toxic gas generation, on the structural performance of concrete structures, such as parking facilities. Then, the evaluation will assess the adequacy of existing fire standards for protecting concrete buildings against EV-induced fires and propose necessary improvements. To achieve this, the study initially focuses on EV fire characteristics and reviews current fire design standards. Then, it examines concrete behaviour and spalling mechanisms, explores retrofitting and mitigation strategies, and establishes recommendations to improve the fire safety of concrete structures. The findings from this paper can support structural engineers, fire engineers, and code developers in understanding and addressing the emerging implications of EV fires for reinforced concrete infrastructure. Collectively, this study provides a technical basis for reassessing fire design assumptions from the codes and standards, proposing performance-based fire engineering applications, and guiding future revisions to fire design provisions for concrete structures as EV adoption increases.

2. EV Fire Characteristics and Statistical Overview

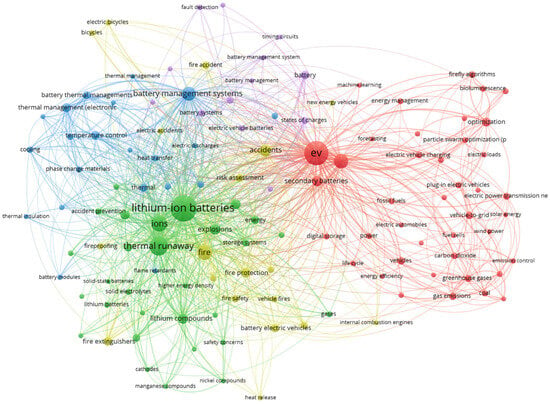

EVs can be mainly categorised under four main categories: battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Among these types, BEVs and HEVs are the most common and widely used EVs, while the use of PHEVs is considerably increasing [10,11]. In order to understand the current status of EV-related fires, a bibliometric analysis was conducted. The Scopus database was chosen for the analysis due to its broader journal coverage. Multiple databases were not used to avoid duplicate articles. Initially, the analysis focused on EV-related fires; the search was then narrowed to identify studies on the impact of EV fires on structural elements. Here, the standards, guidelines and codes used in designing the structures against EV-related fires were also identified. Table 1 gives the search strings used in the bibliometric analysis. A keyword co-occurrence map (Figure 1) was developed using VOSviewer software (v. 1.6.18) [12]. A minimum of 15 keyword occurrences was considered, which met a threshold of 123 keywords. This was developed to gain a broader overview of the research focus, including major trends. According to the network, it is evident that major research related to EV fire is focused on lithium-ion batteries and their thermal runaway.

Table 1.

Search strings for bibliometric analysis.

Figure 1.

Visualisation map of keyword co-occurrence.

EV fires exhibit different characteristics depending on the type of EV. PHEVs generally pose the highest fire hazard due to the combined effects of liquid-fuel combustion and battery thermal runaway [13,14,15]. BEVs exhibit lower peak heat release rates but generate long-duration, re-ignitable fires with high toxicity [16]. HEVs behave similarly to internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, while FCEVs pose unique hazards associated with hydrogen jet flames [5,17]. Table 2 summarises the fire hazards associated with the EVs with their heat release rates (HRR), peak HRR (PHRR) and total HRR (THRR). Considering the popularity of BEVs, HEVs and PHEVs in the market, the study is focused on the battery-induced fires. There are several battery types used in EVs. Lithium-ion (Li-ion), nickel–metal hydride (NiMH), lithium iron phosphate (LFP), and sodium-ion (Na-ion) batteries are the currently used types in the market [18,19,20]. There are other emerging types, such as solid-state batteries, which have safe and better performance but are not yet mass commercialised and lithium sulphur (Li-S) batteries, which are at the research stage [21,22]. NiMH and Na-ion batteries are very stable and low in risk of fire, but they are only suitable for hybrids due to their low energy densities [18,20]. Na-ion batteries are also fire safe, but can only be used in short-range EVs [19]. Among all the batteries, Li-ion remains the industry standard due to its high gravimetric energy density (180–260 Wh/kg) and volumetric density (650–750 Wh/L), which gives the ability of fast charging and higher energy capacity, making it suitable for long-range BEVs [23]. However, it also exhibits the highest fire-risk potential because of its flammable liquid electrolytes and susceptibility to thermal runaway [24,25]. Considering their high market demands, this study focuses on the fire hazards from EVs with Li-ion batteries.

Li-ion battery-induced EV fires are primarily driven by thermal runaway. Thermal runaway is a chain reaction where internal heat generation in a battery exceeds its ability to dissipate heat, resulting in uncontrollable temperature rises [7]. This could potentially result in the initiation of a fire ignition, explosion, or the release of toxic gases [26]. The peak temperature of these EV fires can range between 700 °C and 1050 °C, with significant thermal flux [4,27]. The gases released are highly flammable, toxic, and oxygen-depleting, and carry a significant risk of re-ignition even after they appear to be extinguished [28]. This persistent hazard arises from the delayed decomposition of residual lithium salts, which can continue to generate heat, as well as the release of flammable gases trapped within damaged cells. Even after the initial flames are suppressed, these reactive materials may reignite if not adequately cooled or isolated [3]. As a result, fire suppression efforts must be prolonged and are typically followed by intensive cooling and continuous thermal monitoring to prevent recurrence and ensure complete containment of the hazard [29].

Table 2.

Characteristics of different EV fires.

Table 2.

Characteristics of different EV fires.

| EV Type | HRR | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ICE (petrol/diesel) [30] | PHRR of 3.5–8 MW for passenger cars; higher with fuel spills; THRR of 4–10 GJ | Fast growth once interior involved; dominated by interior combustible materials and fuel; no thermal runaway |

| BEV [4,5] | PHRR 4.2–6.3 MW often similar to or slightly lower than ICE; THRR of 6–9 GJ | HRR comparable to ICE; but long burning, possible re-ignition and high toxicity; jet flame during thermal runaway |

| PHEV [14] | Comparable or slightly lower than similar ICE cars; similar THRR to ICE | Two fuel sources: liquid fuel and high-energy battery; local jet flames from battery and pool fire from fuel |

| HEV [5,17] | Similar to ICE cars | Fire dominated by fuel and cabin; battery adds extra heat and electrical hazards |

| FCEV (hydrogen) [4,31] | PHRR around 6 MW, but a higher THRR of about 11 GJ due to intense local jet fire in the hydrogen vents | Flame is often invisible, with high flame speed, dominated by a hydrogen jet and combustible vehicle materials |

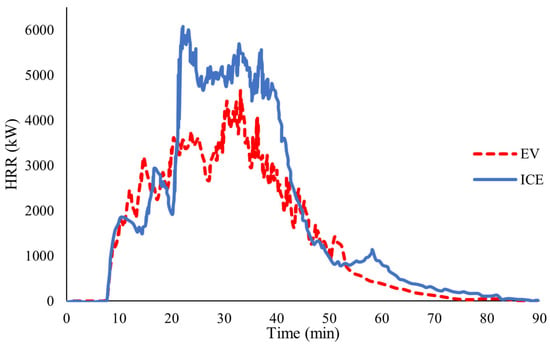

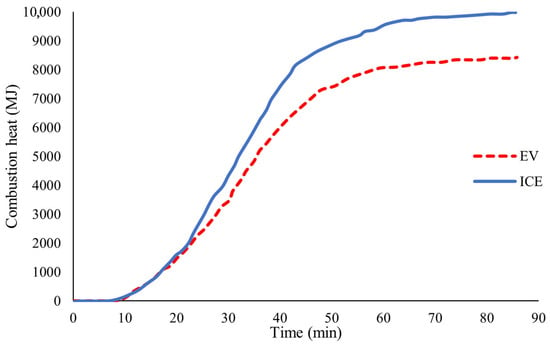

A total of 511 confirmed EV battery fire incidents have been reported worldwide [32]. The majority of these events were attributed to thermal runaway, a failure mechanism that triggers rapid temperature escalation and the potential for a battery explosion. Of the recorded cases, 117 occurred in underground or enclosed parking facilities, 173 in outdoor parking areas, and 155 while vehicles were in motion [32]. These statistics clearly demonstrate that the rapid expansion of the global EV market has been accompanied by heightened fire-safety risks, particularly within confined built environments such as basement car parks, residential garages, and public transport hubs. Lecocq et al. [33] have studied the fire in the EVs with ICEVs to compare their HRR (Figure 2) and effective heat of combustion (Figure 3). The comparison reveals lower HRR in EVs. Although EVs exhibit lower fire incidence than ICEs, including within enclosed or concrete parking structures, the potential consequences of an EV fire are significantly more severe. Thermal runaway can lead to prolonged burning, re-ignition, highly toxic smoke production, and intense localised heating, all of which pose challenges for structural performance, smoke control, and firefighting operations. Therefore, even with lower ignition probability, underground car parks and similar structures must be designed to accommodate the unique severity profile of EV fires [4,5,34]. Hence, it is crucial to investigate the impact of EV fires on the structural elements of related infrastructures.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the heat release rates for EVs and ICEVs reproduced from Lecocq et al. [33].

Figure 3.

Comparison of the effective heat of combustion released for EVs and ICEVs reproduced from Lecocq et al. [33].

EV fires can originate from several interconnected factors, as summarised in Table 3. The most common trigger is mechanical damage or collision, where a high-speed impact or underbody strike can puncture or deform the battery pack, leading to internal short circuits or cell failures. Such incidents are particularly critical in parking ramps or garages, where vehicles may be lifted, towed, or struck by debris, causing undetected battery damage [34]. Internal short circuits or manufacturing defects also pose risks even when vehicles are stationary, as poor assembly, insulation breakdown, or cell degradation can initiate failure without external influence [35]. Additionally, overheating caused by inadequate cooling, prolonged charging, or poor ventilation can increase battery temperature and accelerate the onset of thermal runaway [36]. This is particularly concerning in underground or multi-storey car parks, which often have limited airflow and poor heat dissipation capabilities. Charging faults, including the use of improper chargers, damaged cables, or overvoltage events, can further exacerbate these conditions and potentially initiate a fire [16]. Finally, environmental exposure, such as flooding or moisture ingress, may bridge electrical terminals and induce short circuits, a growing concern for basement-level parking structures prone to water accumulation [37]. Collectively, these triggers underscore that even low-frequency EV fire events can have significant consequences in enclosed concrete facilities, highlighting the need for targeted design strategies, enhanced ventilation, and robust fire suppression planning.

Table 3.

Main mechanisms to initiate EV fires.

Moreover, Table 4 presents several documented examples of EV fires that have occurred in multi-storey and basement carparks [38]. In these incidents, the affected areas typically included adjacent parking bays, surrounding structural concrete elements (such as slabs, beams, and columns), vehicle enclosures, and service installations. Many of these events resulted in severe localised heating, concrete surface spalling, reinforcement exposure, smoke damage, and partial structural deterioration, demonstrating the significant impact EV battery fires can impose on confined carpark environments.

Table 4.

Concrete spalling due to EV battery fire [38].

Apart from car parks, road tunnels are also critical in vehicle fires due to their enclosed geometry, limited heat dissipation, and controlled ventilation [39,40,41]. Dessi et al. [40] investigated large battery EV fires in a road tunnel using the Fire Dynamic Simulator (FDS) and identified that these fires produce prolonged high-temperature conditions and sustained ceiling-layer heating. This has resulted in significant thermal loading of the tunnel lining over an extended period. The study also highlighted that the extended decay period due to these battery fires results in an increase in the cumulative heat flux relative to conventional ICE vehicles. Another study by Li et al. [41] studied the thermal behaviour of tunnel lining insulation materials under EV fire conditions. The results highlighted that when passive fire protection systems are not specifically designed for prolonged high-temperature conditions, the tunnel linings are exposed to elevated temperatures for a longer duration than typically assumed in conventional tunnel fire designs. Full-scale fire tests conducted on electric bus fires have displayed that they can reach peak heat release rates comparable to diesel buses but exhibit a longer energy release duration, leading to greater potential for damage to tunnel infrastructure [39]. Also, it has been identified that, when compared with ICE vehicle fires in tunnels, isolated passenger EV fires do not impose significant risks [42]. However, uncertainties have been identified regarding heavy electric vehicles and multiple simultaneous battery fires, particularly in tunnels and underground carparks [42].

Since the identified risks are predominantly associated with parking and charging facilities, which are primarily constructed of reinforced concrete, it is essential to investigate how concrete behaves at elevated temperatures typical of EV incidents. Lithium-ion battery fires are not primarily characterised by extreme peak heat release rates, which are often comparable to conventional vehicle fires, but by prolonged burning durations, localised jet-like flames, repeated re-ignition, and sustained heat release due to thermal runaway. These characteristics result in non-uniform and extended thermal exposure that differs fundamentally from conventional design fire assumptions. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the suitability of existing concrete structures, particularly older constructions designed to traditional standards, and to assess whether current fire design provisions adequately capture the thermal and mechanical demands imposed by EV-related fires. This study aims to address these gaps by assessing the fire performance of concrete under EV induced thermal exposure and identifying potential improvements to contemporary design and retrofitting practices.

3. Concrete Spalling in EV Fires

Concrete is regarded as a fire-resistant material due to its inherent low thermal conductivity and non-combustibility [43]. However, when exposed to severe fire conditions such as elevated temperatures of more than 300 °C, the performance of concrete degrades significantly [44]. This is mainly due to the physical and chemical changes subjected to concrete when exposed to elevated temperatures [45]. These changes include dehydration of the C-S-H gel [46], loss of moisture [47], and the development of a thermal stress gradient, which results in cracking [47,48], loss of stiffness, and spalling [47,48]. The spalling action due to thermal stress gradient development reflects a critical safety risk due to the reduction of concrete cover and reinforcement exposure, subsequently accelerating the structural failure of concrete elements.

Spalling in concrete has numerous consequences for structural performance. Initially, spalling affects the reduction of the concrete cover to reinforcement, which subsequently results in exposing the reinforced steel [49]. This leads to a loss of bond strength and accelerated corrosion. Moreover, partial or total collapse of structural elements such as columns and slabs is observed due to severe spalling under sustained fire loads [50]. Fire tests conducted by previous studies report that once spalling is initiated in concrete elements at temperatures above 200 °C [8,51,52,53], the residual compressive strength drops by 20% to 40% [54,55,56].

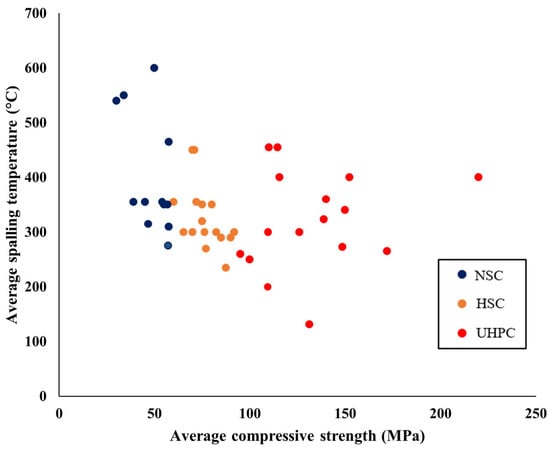

Recent studies indicate that spalling temperatures vary with concrete grade. For normal strength concrete (NSC), where concrete compressive strength is less than 60 MPa, the typical spalling temperature has been identified in the range of 240 to 355 °C [8,51,52,53]. Gradual delamination has been observed in NSCs with low pore pressure, which is a result of high permeability in these cells. The high-strength concretes (HSC) of grades 60 to 80 MPa have recorded the spalling temperature in the range of 150 to 355 °C [53,57,58], while for ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) with concrete grade more than 100 MPa, it has been reported as 256–455 °C [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. HSC has an early onset owing to its dense matrix and trapped vapour. UHPCs display severe explosive spalling due to the dense structure and trapped vapour. However, polypropylene fibre incorporated HSCs have exhibited a reduced level of explosive spalling due to the fibre melting action at around 160 °C. This melting of the fibre increases permeability, helping relieve the pressure trapped. Table 5 presents the different concrete types along with their respective spalling temperatures. Moreover, Figure 4 depicts the average spalling temperatures for average concrete compressive strength values.

Table 5.

Concrete types, along with spalling temperatures.

Figure 4.

Average spalling temperature variation with average concrete compressive strength [8,35,47,48,49,53,54,55,56,57,58,60].

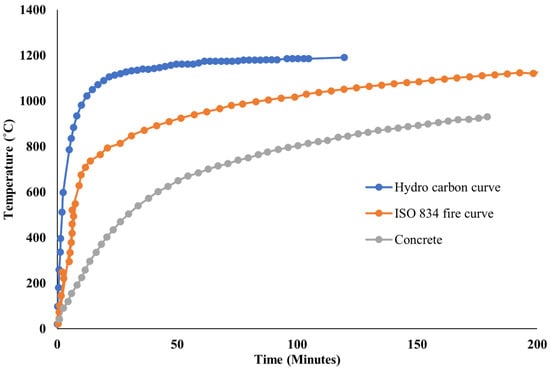

ISO 834 [9], the standard fire curve, represents typical building fires where the temperature rises to approximately 1000 °C within a duration of 2 h [72]. This resembles a moderate heating rate. However, since EV battery fires are uniquely characterised due to their high temperature rise [5,17], thermal runaway [4], and potential for re-ignition, the ISO 834 fire curve cannot be successfully adopted to resemble EV fire scenarios. Hence, the hydrocarbon fire curve where the temperature exceeds 1100 °C within a shorter duration of time, as of 5–10 min [16,45], can be reasonably used to assume the EV fire behaviour. The behaviour of concrete [73] under ISO 834 [9] and hydrocarbon fire curves is presented in Figure 5. Because concrete has low thermal conductivity, its structural elements, such as beams and slabs, exhibit relatively good fire resistance [74]. Hence, the structural strength is retained for a relatively longer duration under heat exposure. Although concrete retains structural strength during initial heat exposure up to about 200 °C, with the temperature rise above 200 °C to 400 °C, most of the concrete types have shown a strength reduction leading to spalling [75]. Concrete columns and walls generally resist fire for extended periods because of their mass and low heat transfer rate [76], though slender members are more prone to instability or buckling once the reinforcement is heated [77]. Under the ISO 834 [9] standard fire curve, temperatures at the reinforcement level typically approach 400 °C to 500 °C after 60 to 120 min, depending on the concrete cover thickness and density [78]. Moreover, exposure to a hydrocarbon fire results in faster heat transfer and accelerated reinforcement deterioration, leading to a more rapid loss of structural integrity [79].

Figure 5.

Different fire curves and behaviour of concrete under fire [9,16,45].

When EV fires are considered, they generate rapid, localised jet flames with temperatures up to 1200 °C within a shorter period [17]. Further, depending on the number of cells in the battery, the jet flash will repeat, rapidly reaching a peak temperature and causing re-ignition. This EV fire nature has the potential to exceed the thermal thresholds (i.e., 240–455 °C) that prevent concrete spalling. Consequently, it can cause concrete spalling and lead to the failure of concrete structures. Due to the high heat flux and jet flash produced during EV fires, even the HSC and UHSC may fail to withstand without adequate protective layers or composite reinforcement.

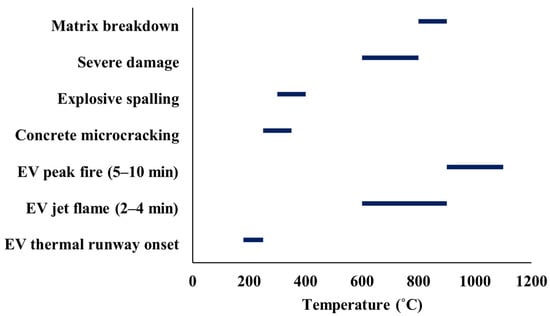

Generally, EV battery fires progress rapidly, initiating from thermal runway onset temperatures ranging from 180 °C to 250 °C [80]. Followed by this, intense jet-flame ejections occur within 3 to 4 min, reaching elevated temperature ranges of 600 °C to 900 °C. Subsequently, these EV fires stabilise at peak temperature ranges of 900 °C to 1200 °C [14,81]. However, in terms of concrete spalling threshold temperatures, these EV fire-related temperature values far exceed the identified thresholds. The initial moisture-driven deterioration, concrete microcracking initiates at 150 °C to 350 °C as a result of free and bound water vaporisation, leading to internal pore-pressure development [82]. With further increase of temperature, at around 300 °C to 400 °C, explosive spalling of concrete elements is more likely due to the exceedance of concrete’s tensile capacity by the developed pore-pressure [8,35,51,52,53,57,58,59,60,61,62,64]. When the temperature rise due to EV fires exceeds these threshold values within a shorter period of time of 1 to 3 min, the concrete elements are likely to be subject to rapid heating. As a result, highly unstable thermomechanical behaviour in concrete elements can be predicted due to reduced time for moisture migration and pressure relief within the element. Moreover, with the EV fire reaching a temperature range of 600 °C to 900 °C, the decomposition of C–S–H bonds and aggregate breakdown, leading to critical structural weakening of the element, can be predicted. This could further result in progressive spalling action. Figure 6 demonstrates that EV battery fires, in addition to exceeding the standard fire design curves, directly overlap and even surpass the critical threshold temperatures associated with concrete spalling.

Figure 6.

Temperature variation of EV battery fire and concrete spalling thresholds.

The effects of concrete spalling from EV fires are significant in enclosed environments, such as basement car parks. Due to their enclosed nature and limited heat dissipation, road tunnels also have a similar impact from EV battery fires [16,29]. This is mainly because concrete spalling in tunnel linings is affected by temperature, heating rate, and exposure period [16]. According to the tunnel fire related studies, it is evident that when exposed to sustained temperatures, concrete exhibits progressive deterioration [29,40]. The combined action of high temperature and rapid heating can also trigger explosive spalling. According to the numerical studies and full-scale test studies conducted on EV fires in tunnels, when compared with conventional vehicle fires, EV battery-driven fires result in prolonged thermal exposure leading to concrete spalling and increased damage depth in tunnel linings [29,40]. EV fires in tunnels demonstrate the potential to sustain high ceiling-layer temperatures for extended periods, particularly under longitudinal ventilation. This results in persistent thermal loading of the concrete lining. Due to the prolonged heating, it results in increasing the thermal gradients, pore pressure build-up, and restrained thermal expansion in tunnel linings. As a result, spalling severity and damage depth are increased. Moreover, progressive cracking, spalling propagation, and the damage depth have been observed to increase in thermo-mechanical analyses of tunnel linings subjected to extended fire exposure.

As both integrity and the fire resistance of concrete structural elements are affected by concrete spalling, critical and direct implications towards building safety are associated with concrete spalling. In car parks and tunnels where fire duration and thermal exposure are prolonged due to the confined nature of the environment, spalling can be a governing reason for structural failure, which has severe implications compared to surface-level damage in building safety. Risk of partial collapse, hazards due to debris falling, and post-fire instability scenarios exist with the elevated spalling severity levels. As a result, occupant evacuation, firefighter safety, and structural repairability concerns arise to ensure the building’s safety.

Therefore, a concrete structure is severely affected by spalling at elevated temperatures; despite its inherent fire-resistant properties, it has building safety-related concerns. Consequently, it is vital to evaluate its performance under EV fire scenarios. Although the hydrocarbon fire curve resembles reasonable behaviour (rapid temperature rises) for EV fire scenarios, a well-defined fire curve is needed that captures the distinct characteristics of EV fires (i.e., jet flash, re-ignition, etc.). Hence, experimental and numerical studies need to be expanded in this area to inform updates to existing fire design standards. This will subsequently enable them to be used in retrofitting existing buildings and adopted for new designs against EV fire.

4. Assessment of Current Australian Fire Design Provisions for EV Fire Exposure

NCC [83] is Australia’s primary document that sets minimum standards for building design and construction, covering safety, health, and sustainability, and includes key requirements for fire safety. The specific standards that guide and regulate fire safety designs, as outlined in the NCC, include AS 1530 [84] (methods for fire tests on building materials), AS 1670 [85] (fire detection and alarm systems), AS 1851 [86] (maintenance of fire protection systems), AS 2118 [87] (automatic fire sprinkler systems) and AS 2419 [88] (fire hydrant installations). Apart from these, several international standards such as ISO 834 [9], ASTM E119 [89], and EN 1992-1-2 [90] also guide fire safety design and performance requirements.

Although most standards account for the general effects of elevated temperatures on materials, they do not explicitly address battery-related fire dynamics, including re-ignition potential, toxic gas production, and heat accumulation in confined spaces. As a result, the fire resistance ratings prescribed for concrete slabs, beams, and columns may not ensure structural integrity when exposed to EV-induced thermal loads, especially in underground or multi-storey car parks, where heat dissipation is limited. Moreover, existing verification methods, such as the Fire Safety Verification Method (FSVM) introduced in the NCC (2022) [83], are yet to incorporate empirical or simulation data representing EV fire scenarios.

The inclusion of AS 1530.4 [84] highlights that most fire resistance tests and design provisions in the NCC [83] rely on a standardised furnace exposure derived from ISO 834 [9], which gradually allows the fire to burn and the building material to respond over time, predictably releasing heat thermally. In contrast, EV battery fires exhibit fundamentally different thermal characteristics, as shown in Table 6. These deviations suggest that fire ratings derived from AS 1530.4 [84], ISO 834 [9] or EN 1992-1-2 [90] tests are underestimating the severity of EV fire induced thermal loads on reinforced-concrete structures, especially in confined parking environments. This raises critical concerns about the reliability of existing fire design provisions, particularly for reinforced concrete elements, which were previously identified as prone to explosive spalling and reinforcement exposure under extreme heating conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison of EV fire characteristics and standard design fire curves.

In order to strengthen the fire resilience of structures against EV fire exposure, several improvements can be proposed to address the limitations identified in current codes and standards. Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 outline recommended enhancements to passive protection, active suppression, and maintenance practices, aligned with the NCC 2022 [83] and relevant Australian Standards. These measures focus on increasing FRLs, improving spalling resistance, expanding water-supply capacity, and introducing advanced detection and ventilation systems specifically tailored for EV environments.

Table 7.

Recommendations for passive protection.

Table 8.

Recommendations for an active fire system.

Table 9.

Recommendations for operational and maintenance measures.

In addition to these standard driven upgrades, a performance-based evaluation is essential to fully capture the unique thermal behaviour of EV fires. This approach can replace the standard ISO 834 [9] time vs. temperature curve with empirical EV fire curves obtained from full-scale testing and employs computational fluid dynamics (CFD) or finite-element analysis following EN 1991-1-2 [86] to model localised heat flux and temperature distribution. The resulting concrete surface temperatures and spalling depths can then be compared with AS 3600 [88] fire-limit criteria, while the NCC [83] FSVM should be reviewed for its ability to represent extended EV fire durations. Collectively, these improvements provide a pathway to evolve existing prescriptive standards into a performance-based, evidence-driven framework that better safeguards reinforced concrete parking structures from EV induced fire hazards.

5. Summary and Recommendations

The growing demand for electric vehicles has introduced a new class of fire risk to the built environment, particularly in underground and multi-storey parking facilities constructed predominantly from reinforced concrete. Statistical data and experimental studies indicate that, although the overall frequency of EV fires remains relatively low, their severity, duration, and re-ignition potential far exceed those of conventional hydrocarbon-fuelled vehicles. EV battery fires, driven by the thermal runaway of lithium-ion cells, can generate temperatures above 1200 °C, creating high heat flux and toxic off-gases in confined spaces.

Although concrete is traditionally regarded as a non-combustible material, exposure to intense heat, even for prolonged periods, makes it highly vulnerable to spalling. When different types of concrete are considered, it has been established by previous studies that normal-strength concretes generally experience moderate surface scaling at around 240 °C to 355 °C [8,47,48,49], dense high-strength concrete at 150 °C to 355 °C [49,53,54], and ultra-high-performance concretes tend to spall explosively at 256 °C to 455 °C [49,53,54] because their low permeability traps steam pressure [8,52,61]. Under the ISO 834 [9] standard fire curve, which typically reflects the building fire scenarios, the temperature rise is gradual, allowing partial moisture relief. However, under a hydrocarbon fire curve, which can be reasonably assumed to resemble the EV battery fire scenarios, the temperatures can exceed 1000 °C within a shorter period. Hence, the extremely rapid heating, localised jet flames, and sustained high heat flux of EV fires intensify pore pressure and thermal gradients, causing early and severe spalling in concrete structural elements. Therefore, concrete buildings designed for ordinary building fires may not withstand EV induced fire exposure. This rising issue of buildings related to EV battery fire emphasises the requirement for new fire models to reflect EV battery fire scenarios. Hence, in order to bridge this identified knowledge gap, the existing fire design standards need to be updated accordingly using experimental and numerical results.

The review of current fire design provisions, including NCC 2022 [83], AS 1530 [84], AS 2118 [87], and related international standards such as ISO 834 [9] and EN 1992-1-2 [90], reveals that existing methodologies are primarily calibrated for conventional cellulosic and hydrocarbon fire scenarios. These design curves typically assume 1 to 2 h of exposure durations and uniform heating patterns, which inadequately represent the non-linear, localised, and prolonged heating produced during EV fires.

In concrete structures, these misalignments between EV fires and code-implied fire scenarios will significantly impact fire-resistance design. Conventional fire-resistance ratings and verification methods may systematically underestimate the peak and cumulative thermal and structural demands, as well as the thermal degradation, imposed by EV-induced fire events, especially in enclosed or poorly ventilated parking facilities. As a result, compliance with existing design standards and codes does not inherently imply acceptable structural performance and robustness when exposed to EV fires.

To bridge this gap, code-based improvements are recommended through enhanced passive protection, high capacity suppression systems, and rigorous maintenance practices aligned with NCC 2022 [83] and associated Australian Standards. However, reliance solely on prescriptive compliance is insufficient. Therefore, a fundamental reassessment of fire design provisions is required, where EV fires can be included as a distinct design scenario rather than a marginal variation of hydrocarbon and cellulosic fires.

Moreover, future fire design frameworks should transition toward a performance-based evaluation framework utilising critical review of code assumptions, incorporation of measured EV fire curves, performance-based fire engineering analysis, CFD-based thermal characterisation, thermo-mechanical structural modelling, and extended-duration and robustness assessment. These methods will provide a more accurate representation of real-world thermal exposure with specific thermal conditions and thermo-mechanical modelling. In this case, NCC [83] FSVM should be further expanded to incorporate EV-specific fire scenarios, prolonged exposure durations, and non-uniform thermal boundary conditions. These extensions will provide a more realistic representation of EV fires and support evidence-based assessment of structural reliability under EV fires.

In summary, while existing codes provide a foundation for structural fire safety, they do not yet reflect the emerging challenges posed by EV induced fires. Integrating empirical fire data, advanced simulation tools, and performance-based fire engineering into design and retrofitting practices is essential to ensure the durability, safety, and resilience of concrete structures in the evolving era of electric mobility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.; methodology, S.B., T.M. and S.N.; validation, S.N., J.S. and P.R.; formal analysis, S.N., S.B. and T.M.; investigation, S.B., S.N. and T.M.; resources, P.R., S.N. and J.S.; data curation, S.N., P.R. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N., S.B. and T.M.; writing—review and editing, S.N., P.R. and J.S.; visualization, S.B. and T.M.; supervision, S.N. and P.R.; project administration, S.N.; funding acquisition, P.R. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for financial support from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (DP210100020), (IH240100006) and Vetali Engineers Pty Ltd. for conducting this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Federation University and Swinburne University of Technology for their support in terms of technical, financial, and other research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ritchie, H. Tracking Global Data on Electric Vehicles. Our World in Data. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/electric-car-sales (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Rücker, F.; Figgener, J.; Schoeneberger, I.; Sauer, D.U. Battery Electric Vehicles in Commercial Fleets: Use profiles, battery aging, and open-access data. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnikowski, D.; Mieloszyk, M. Experimental Investigations on the Repeatability of the Fire-Resistance Testing of Electric Vehicle Post-Crash Safety Procedures. Sensors 2025, 25, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kwon, M.; Yoon Choi, J.; Choi, S. Full-scale fire testing of battery electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2023, 332, 120497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kwon, M.; Choi, J.; Choi, S. Full-Scale Fire Testing to Assess the Risk of Battery Electric Vehicle Fires in Underground Car Parks. Fire Technol. 2025, 61, 4133–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. EV Car Fires vs Gas: Data Shows 61x Lower Risk in Electric Vehicles. 2025. Available online: https://fsri.org/research-update/ev-fires-vs-gas-powered-vehicle-fires-air-contamination-risks-explored-new-article (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Peng, S.; Shen, Y.; Xia, G.; Maddipatla, S.; Kong, L.; Diao, W.; Pecht, M.G. Thermal Runaway and Mitigation Strategies. In The Safety Challenges and Strategies of Using Lithium-Ion Batteries; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fares, H.; Noumowé, A.; Rémond, S. Self-consolidating concrete subjected to high temperature: Mechanical and physicochemical properties. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 834-1:2025; Fire-resistance Tests—Elements of Building Construction—Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Alanazi, F. Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriabisha, R.; Kumar, J.A.; Jayaprabakar, J.; Deivayanai, V.C.; Saravanan, A. A comprehensive exploration of electric vehicles: Classification, charging methods, obstacles, and approaches to optimization. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, N.J.V.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer, Version 1.6.18; Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS), Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010.

- Hynynen, J.; Willstrand, O.; Blomqvist, P.; Andersson, P. Analysis of combustion gases from large-scale electric vehicle fire tests. Fire Saf. J. 2023, 139, 103829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cong, B.; Liu, J.; Qiu, M.; Han, X. Characteristics and Hazards of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle Fires Caused by Lithium-Ion Battery Packs With Thermal Runaway. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 878035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, E.; Flecknoe-Brown, K.W.; Wijesekere, T.; Husted, B.P.; Andres, B. Fire extinguishment tests of electric vehicles in an open sided enclosure. Fire Saf. J. 2023, 141, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsz, A.; Lewandowski, M. Analysis of Fire Hazards Associated with the Operation of Electric Vehicles in Enclosed Structures. Energies 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Bisschop, R.; Niu, H.; Huang, X. A Review of Battery Fires in Electric Vehicles. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 1361–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M. Connecting battery technologies for electric vehicles from battery materials to management. iScience 2022, 25, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Benson, S.M.; Chueh, W.C. Critically assessing sodium-ion technology roadmaps and scenarios for techno-economic competitiveness against lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evro, S.; Ajumobi, A.; Mayon, D.; Tomomewo, O.S. Navigating battery choices: A comparative study of lithium iron phosphate and nickel manganese cobalt battery technologies. Future Batter. 2024, 4, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidi, A.; Khawaja, M.K.; Ismail, S.M. Solid-state batteries, their future in the energy storage and electric vehicles market. Sci. Talks 2024, 11, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Guo, W.; Li, W.; Hua, L.; Zhao, F. Lithium-sulfur batteries for next-generation automotive power batteries carbon emission assessment and sustainability study in China. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 114199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralls, A.M.; Leong, K.; Clayton, J.; Fuelling, P.; Mercer, C.; Navarro, V.; Menezes, P.L. The Role of Lithium-Ion Batteries in the Growing Trend of Electric Vehicles. Materials 2023, 16, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.; Venkateswarlu, B.; Prabakaran, R.; Salman, M.; Joo, S.W.; Choi, G.S.; Kim, S.C. Thermal runaway and mitigation strategies for electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries using battery cooling approach: A review of the current status and challenges. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, M.; Özcan, M.; Eker, Y.R. A review on the lithium-ion battery problems used in electric vehicles. Next Sustain. 2024, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukya, M.; Hanni, J.R.; Kumar, R.; Mathur, A. A computational study of the high-discharge thermoelectric performance of cylindrical battery packs for electric vehicles. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wei, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S. Analysis of the fire evolution process of an electric vehicle in a confined garage. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 167, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Xie, W.; Yin, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, S.; Yang, S.; Lu, Z. Comparative analysis of full-scale battery electric vehicle fire evolution under open and semi-enclosed conditions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 202, 107679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, P.; Fößleitner, P.; Fruhwirt, D.; Galler, R.; Wenighofer, R.; Heindl, S.F.; Krausbar, S.; Heger, O. Fire tests with lithium-ion battery electric vehicles in road tunnels. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 134, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miechówka, B.; Węgrzyński, W. Systematic Literature Review on Passenger Car Fire Experiments for Car Park Safety Design. Fire Technol. 2025, 61, 2651–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seike, M.; Kawabata, N.; Hasegawa, M.; Tanaka, H. Heat release rate and thermal fume behavior estimation of fuel cell vehicles in tunnel fires. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 26597–26608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Vehicle Council, Australia, Are Electric Vehicle Fires Common? Available online: https://electricvehiclecouncil.com.au/docs/are-electric-vehicle-fires-common/#:~:text=Electric%20vehicle%20battery%20fires%20are,(as%20of%20June%202024) (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Lecocq, A.; Bertana, M.; Truchot, B.; Marlair, G. Comparison of the fire consequences of an electric vehicle and an internal combustion engine vehicle. In 2 International Conference on Fires In Vehicles-FIVE 2012; SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden: Chicago, IL, USA; Boras, Sweden, 2012; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Tohir, M.Z.; Martín-Gómez, C. Electric vehicle fire risk assessment framework using Fault Tree Analysis. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 3, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Choi, D.; Jeong, Y.; Moon, M.; Kwon, H.; Han, K.; Kim, H.; Im, H.; Park, Y.; Shin, D.; et al. Assessing fire dynamics and suppression techniques in electric vehicles at different states of charge: Implications for maritime safety. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Hu, W.; Meng, D.; Mi, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Full-scale experimental study of the characteristics of electric vehicle fires process and response measures. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Saltwater Flooding Is a Serious Fire Threat for EVs and Other Devices with Lithium-Ion Batteries; University of South Carolina: Columbia, SC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- State Government of New South Wales. Electric Vehicles (EV) and EV Charging Equipment Inthe Built Environment. Fire and Rescue NSW. 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.fire.nsw.gov.au/gallery/resources/SARET/Fire%2520Safety%2520Position%2520Paper%2520-%2520Electric%2520vehicles%2520(EV)%2520and%2520EV%2520charging%2520equipment%2520in%2520the%2520built%2520environment%2520v1.0.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjfz-aBx9qRAxWwlK8BHfY5M4MQFnoECBsQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2M-UkFjo_kLC0CQ8eTxxyj (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Raza, H.; Li, S. The impact of battery electric bus fire on road tunnel. In Expanding Underground—Knowledge and Passion to Make aPositive Impact on the World, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 3280–3288. [Google Scholar]

- Dessì, R.; Fruhwirt, D.; Papurello, D. A Study on Large Electric Vehicle Fires in a Tunnel: Use of a Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS). Processes 2025, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, Y. Comparative Study on Fire Resistance of Different Thermal Insulation Materials for Electric Vehicle Tunnel Fire. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Technical Research Organisation. Electric Vehicle Fires in Tunnels—Do We Need to be Concerned? Available online: https://www.ntro.org.au/news-and-insights/electric-vehicle-fires-in-tunnels---do-we-need-to-be-concerned (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Wu, Y. Temperature and stress of RC T-beam under different heating curves. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 46, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar Tanash, A.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Muthusamy, K.; Al Biajawi, M.I. Effect of elevated temperature on mechanical properties of normal strength concrete: An overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 107, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkit, U.; Das Adhikary, S. Effect of micro-structural changes on concrete properties at elevated temperature: Current knowledge and outlook. Struct. Concr. 2021, 23, 1995–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantawy, M. Effect of High Temperatures on the Microstructure of Cement Paste. J. Mater. Sci. Chem. Eng. 2017, 05, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Rico, J.; Tamayo, P.; Ballester, F.; Setién, J.; Polanco, J.A. Effect of elevated temperature on the mechanical properties and microstructure of heavy-weight magnetite concrete with steel fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 103, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Aryanpour, M.; Porhonar, F. Microstructural study of concrete performance after exposure to elevated temperatures via considering C–S–H nanostructure changes. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2022, 41, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Monte, F.; Felicetti, R.; Rossino, C. Fire spalling sensitivity of high-performanceconcrete in heated slabs under biaxial compressive loading. Mater. Struct. 2019, 52, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Huang, S.-S.; Onaizi, A.M.; Murali, G.; Abdelgader, H.S. Fire spalling behavior of high-strength concrete: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumowe, A.N.; Clastres, P.; Debicki, G.; Costaz, J.L. Transient heating effect on high strength concrete. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1996, 166, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.; Lawson, J.; Davis, F. Effects of elevated temperature exposure on heating characteristics, spalling, and residual properties of high performance concrete. Mater. Struct. 2001, 34, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanema, M.; Pliya, P.; Noumowé, A.; Gallias, J.-L. Spalling, Thermal, and Hydrous Behavior of Ordinary and High-Strength Concrete Subjected to Elevated Temperature. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Yang, J. Residual Mechanical Properties and Explosive Spalling Behavior of Ultra-High-Strength Concrete Exposed to High Temperature. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. New Ser. 2017, 24, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sanaul, C. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Mechanical Properties of High Strength Concrete. In Proceedings of the 23rd Australasian Conference on the Mechanics of Structures and Materials (ACMSM23), Byron Bay, Australia, 9–12 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kanagaraj, B.; Raj, R.S.; Anand, N.; Lubloy, E. Fire performance of concrete: A comparative study between cement concrete and geopolymer concrete & its application—A state of art-review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101212. [Google Scholar]

- Debicki, G.; Haniche, R.; Delhomme, F. An experimental method for assessing the spalling sensitivity of concrete mixture submitted to high temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingsch, E. Explosive Spalling of Concrete in Fire. 2014. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/server/api/core/bitstreams/463e1db4-54d8-4247-b48d-5aec1056fcef/content&ved=2ahUKEwjm1MquydqRAxUsdfUHHZPAJkQQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1ekpgWF1oKTAZgGJk1loj_ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Akturk, B.; Yüzer, N.; Kabay, N. Usability of Raw Rice Husk Instead of Polypropylene Fibers in High-Strength Concrete under High Temperature. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04015072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wu, C.; Su, Y.; Li, Z. Development of ultra-high performance concrete with high fire resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 179, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Deng, C.; Luo, Y. Mechanical properties and microstructure of UHPC with recycled glasses after exposure to elevated temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 62, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suescum-Morales, D.; Ríos, J.D.; Martínez-De La Concha, A.; Cifuentes, H.; Jiménez, J.R.; Fernández, J.M. Effect of moderate temperatures on compressive strength of ultra-high-performance concrete: A microstructural analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.K.; Koh, K.T.; Park, S.H.; Ryu, G. Microstructural investigation of calcium aluminate cement-based ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) exposed to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 102, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.; Cifuentes, H.; Leiva, C.; Ariza, M.P.; Ortiz, M. Effect of polypropylene fibers on the fracture behavior of heated ultra-high performance concrete. Int. J. Fract. 2020, 223, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Canbaz, M. The effect of high temperature on reactive powder concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 70, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xi, H. Explosive Spalling Mechanism and Modeling of Concrete Lining Exposed to Fire. Materials 2022, 15, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L. High-Strength Concrete at High Temperature—An Overview. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposiumon Utilization of High Strength/High Performance Concrete, Leipzig, Germany, 16–20 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bastami, M.; Chaboki-Khiabani, A.; Baghbadrani, M.; Kordi, M. Performance of high strength concretes at elevated temperatures. Sci. Iran. 2011, 18, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husem, M. The effects of high temperature on compressive and flexural strengths of ordinary and high-performance concrete. Fire Saf. J. 2006, 41, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Nadjai, A.; Glackin, P.; Silcock, G.; Abu-Tair, A. Structural Performance of High Strength Concrete Columns in Fire. Fire Saf. Sci. 2003, 7, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.-F.; Yang, W.-W.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.-F.; Bian, S.-H.; Zhao, L.-H. Explosive spalling and residual mechanical properties of fiber-toughened high-performance concrete subjected to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, P.; Torres, B.; Payá-Zaforteza, I.; Calderón, P.; Sales, S. Evaluation of new regenerated fiber Bragg grating high-temperature sensors in an ISO 834 fire test. Fire Saf. J. 2015, 71, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Youm, K.; Reda Taha, M. Extracting Concrete Thermal Characteristics from Temperature Time History of RC Column Exposed to Standard Fire. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 242806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehfuß, J.; Robert, F.; Spille, J.; Razafinjato, R. Evaluation of Eurocode 2 approaches for thermal conductivity of concrete in case of fire. Civ. Eng. Des. 2020, 2, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, A.; Yehia, S.; Lublóy, É.; Elchalakani, D.M. Performance of Different Concrete Types Exposed to Elevated Temperatures: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshal, I.; Bakar, B.H.; Tayeh, B. Behaviour of Reinforced Concrete Walls Under Fire: A Review. Fire Technol. 2022, 58, 2589–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, K. Fire Resistance-effective Parameters Relationships of slender rectangular and circular RC Columns. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 125, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigha, F.; Sadeeq, J.A.; Abejide, O.S. Effects of Temperature Levels and Concrete Cover Thickness on Residual Strength Characteristics of Fire Exposed Reinforced Concrete Beams. Niger. J. Technol. 2015, 34, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V. Performance of reinforced concrete slabs under hydrocarbon fire exposure. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkov, A.W.; Planteu, R.; Krohn, P.; Rasch, B.; Brunnsteiner, B.; Thaler, A.; Hacker, V. Thermal runaway of large automotive Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40172–40186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wang, G.; Ping, P.; Wen, J. A coupled conjugate heat transfer and CFD model for the thermal runaway evolution and jet fire of 18650 lithium-ion battery under thermal abuse. eTransportation 2022, 12, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, G.; Kim, G.; Yoon, M.; Hwang, E.; Nam, J.; Guncunski, N. Effect of moisture migration and water vapor pressure build-up with the heating rate on concrete spalling type. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 116, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Building Codes Board. National Construction Code (NCC); Australian Building Codes Board: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- AS 1530; Methods for Fire Tests on Building Materials, Components and Structures. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022.

- AS 1670; Fire Detection, Warning, Control and Intercom Systems Standards Australia. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2018.

- AS 1851:2012; Routine Service of Fire Protection Systems and Equipment Standards Australia. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2012.

- AS 2118; Automatic Fire Sprinkler Systems. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016.

- AS 2419; Fire hydrant Installations. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2015.

- ASTM E119-22; Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- EN 1992-1-2; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-2: General Rules—Structural Fire Design. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Choi, A.Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, T.-H.; Kim, H.-S. Comparative Analysis of Real Fires for Electric Vehicles and Gasoline Vehicles. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2021, 21, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AS 3600:2018; Concrete Structures. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2018.

- AS/NZS 1668; The Use of Ventilation and Air Conditioning in Buildings–Fire and Smoke Control in Multi-Compartment Buildings. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia; Standards New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- AS 2441; Installation of Hose Reels. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2009.

- NFPA 855; Standard for the Installation of Stationary Energy Storage Systems. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA): Quincy, MA, USA, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.