Abstract

During the summer fire season in the Greater Khingan Mountains, weak synoptic winds allow local mountain–valley breeze systems to predominantly influence fire spread. However, their dynamic effects remain insufficiently quantified, limiting fire forecasting accuracy. This study analyzes a decade of summer meteorological data and a high-resolution WRF-Fire simulation of a 2023 wildfire to investigate wind patterns and their impact on fire behavior. Results reveal pronounced diurnal and spatial wind variability, with low directional persistence and concentrated nighttime distributions. Under low-wind conditions, mountain–valley breezes shift from upslope during the day to downslope flows at night. Simulations and observations indicate higher nighttime wind speeds on slopes and higher daytime speeds in valleys, reflecting the combined effects of thermal circulation and gravitational acceleration. The WRF-Fire model effectively reproduced the wildfire’s macro-scale spread pattern, showing strong agreement with satellite-derived burn scars in mountainous regions. Fire progression was influenced by five distinct phases, with nocturnal mountain winds and topographic channeling accelerating spread. These highlight the role of terrain-driven mountain–valley breezes in fire propagation and provide insights to improve fire forecasting and management strategies in mountainous regions. Firefighting strategies must account for the diurnal cycle of wind, particularly the contrast between strong nighttime winds at higher altitudes and stable valley conditions.

1. Introduction

Wildfires not only result in direct casualties but also severely impact human health and ecosystem stability by degrading the atmosphere, water quality, and climate system [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. With global climate change, the frequency of extreme fire weather events and the intensity of wildfire activity have risen markedly [9,10], leading to longer fire durations and more extensive affected areas [11,12]. In this context, accurately predicting fire behavior is crucial for developing effective suppression strategies, optimizing resource allocation, and ensuring firefighter safety [13,14].

Wildfire behavior is driven by the complex interactions between fuel properties, topography, and meteorological conditions [15]. Topography influences fire dynamics across multiple spatial and temporal scales [16,17,18]. On a climatic scale, elevation, slope, and aspect affect the distribution of fuel types by shaping local hydrothermal conditions [16,17]. On synoptic and diurnal scales, terrain features interact with atmospheric boundary layer processes, generating localized wind, temperature, and moisture patterns that directly influence fire spread [18]. Among these factors, wind is the most variable [16,19,20], and sudden shifts in wind speed or direction can significantly increase risks to firefighting operations, potentially leading to casualties [5,6,7,8]. However, the nonlinear interactions between atmospheric motion and rugged terrain create high spatiotemporal variability in meteorological variables, making accurate quantification challenging. Although understanding these interactions is a central issue in mountain meteorology, most studies have primarily focused on atmospheric mechanisms, with limited research systematically linking them to fire behavior [21].

The mountain–valley breeze is a classic local thermal circulation in mountainous terrain, driven by diurnal reversal of the horizontal pressure gradient caused by thermal differences between the air over mountain slopes and the adjacent valley atmosphere [16,22,23,24,25,26,27]. During the day, the slopes heat more rapidly than the valley air, creating an unstable stratification that causes warm air to flow upslope as the valley wind. At night, the slopes cool rapidly due to longwave radiation, and the denser, cooled air descends, forming the mountain wind [25,26,27,28]. While the basic mechanisms of valley winds are well-established, their interaction with fire spread—particularly in forested regions like the Greater Khingan Mountains—has not been systematically studied. Unlike the well-documented foehn-driven fires [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], wildfire dynamics under the influence of diurnal mountain–valley breezes remain poorly understood. Under strong synoptic winds, the large-scale circulation dominates, making local breezes less significant; however, under weak background winds, the effect of the mountain–valley breeze on fire behavior becomes pronounced. This study focuses on fire spread under weak synoptic forcing, using the 2023 wildfire in the Greater Khingan Mountains as a case study. This region, with its mid-low elevation hills, high fuel loads, and mixed coniferous–broadleaf forests [40], provides a representative example of forested areas globally with complex topography. Previous research has mainly examined climatic fire drivers [41,42,43,44,45], but few studies have used high-resolution, coupled atmosphere–fire models to explore the role of diurnal wind systems in individual fires.

Addressing this gap, this study combines climatological analysis with high-resolution fire spread simulations to explore the influence of valley wind circulation on wildfire spread under weak synoptic conditions. The main contributions of this study are threefold. First, leveraging a decade of meteorological observations, we systematically characterize the climatological features of local mountain–valley breeze circulation under weak wind conditions, thereby providing essential climatic context and a solid analytical basis for subsequent case simulations. Second, using the coupled WRF-Fire model, we perform a high-resolution simulation of a representative 2023 wildfire event occurring under weak wind conditions, revealing dynamic interactions between fire behavior and local circulation that are challenging to capture through observations alone. Third, through quantitative analysis, we elucidate the process-oriented dynamic response of fire spread to the diurnally alternating wind system under weak winds, with particular emphasis on the critical role of nocturnal mountain winds in driving fireline advancement, thus addressing prior gaps in understanding this mechanism. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the case study, data sources, and methods; Section 3 presents the climatological and simulation results; Section 4 discusses the theoretical implications, fire management relevance, limitations, and future directions; and Section 5 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Case and Area

2.1.1. Study Area

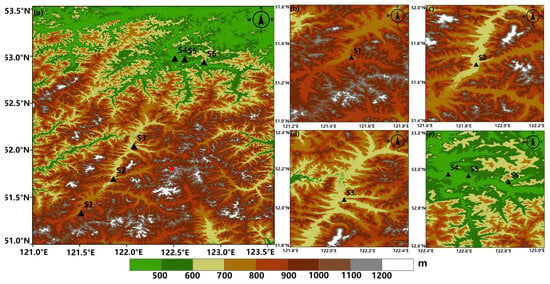

The Greater Khingan Mountains is the country’s largest continuous cold-temperate pristine forest and serves as a critical hotspot for wildfire activity. The study area is situated in the northwestern region of the Greater Khingan Mountains, Inner Mongolia, China. Elevations within the area range from 200 m to 1500 m, and the terrain is characterized by a complex landscape of valleys and slopes that exert significant influence on local microclimates and wind patterns.

2.1.2. Wildfire Case Description

From 6 August to 12 August 2023, 15 wildfire incidents were identified in the northern forest area, displaying a pattern of concentrated multi-point ignitions. This study focuses on a specific wildfire that occurred at Abei Forest Farm in the Greater Khingan Mountains at 07:00 UTC on 6 August 2023 (local time UTC + 8; all times hereafter are UTC). The ignition point was located on a mountainside at an elevation of approximately 1200 m above sea level, with higher terrain extending to the south and lower terrain to the north (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Topographic map of the study area. (a) Distribution of the ignition point (red dot) and surrounding meteorological stations (S1–S6, black triangles) over the terrain; (b) Topography and location map of meteorological station S1; (c) Topography and location map of meteorological station S2; (d) Topography and location map of meteorological station S3; (e) Topography and location map of meteorological station S4–S6.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Data for Wind Characteristic Analysis

This study utilized meteorological data collected from automatic weather stations and radiation stations, including daily precipitation, hourly wind speed and direction, and daily global solar radiation. The dataset spans the summer months (June–August) from 2015 to 2024. The automatic weather stations provide continuous, high-precision monitoring of key meteorological variables. Wind speed is measured within a range of 0–60 m/s, with a resolution of 0.1 m/s and a maximum permissible error of ±(0.5 + 0.03 V) m/s, where V represents the measured wind speed. Wind direction is recorded within 0–360°, offering a resolution of 3° and an accuracy of ±5°. Precipitation is measured for intensities ranging from 0 to 4 mm/min, with a resolution of 0.1 mm. The maximum permissible error is ±0.4 mm for accumulated precipitation ≤10 mm and ±4% of the reading for values exceeding 10 mm. Additionally, the pyranometer at the radiation station measures global solar radiation within a spectral range of 300–3000 nm, featuring a 95% response time of 5 s. All instrument specifications adhere to the technical standards outlined in the manufacturers’ manuals and operational observation protocols. While automatic weather station data offer high precision and strong timeliness, these be subject to missing or erroneous measurements. To address this, quality control procedures were applied, following the methodology of Dou et al. [46]. The quality control steps included an Extreme Value Check to remove observations outside historical extremes; an Internal Consistency Check to eliminate inconsistent records, such as cases where wind speed was zero but wind direction was not recorded as calm; and a Missing Data Check to exclude stations with missing data exceeding 15%, or any specific day with more than 6 h of missing data.

2.2.2. Data for Fire Spread Simulation

Fuel Data

Vegetation types near the fire ignition point were determined based on the GLC_FCS30-1985_2020 [47] land cover data. The primary vegetation types identified in the vicinity of the fire were evergreen needleleaf forest, deciduous needleleaf forest, and deciduous broadleaf forest. These types were then cross-referenced and mapped to the 13 fuel categories defined by Anderson [48].

Topographic Data

For the first three model nesting domains, terrain data with resolutions of 5′, 2′, and 30″ from the standard WRF model dataset were used. For the fourth (innermost) nesting domain, topographic data from ASTER GDEM [49] were employed, with a raster resolution of approximately 30 m.

Meteorological Background Field Data

The initial and boundary conditions for the model simulation were obtained from the Final (FNL) operational global analysis data from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). This dataset has a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° and is available four times per day.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Wind Characteristic Analysis

Wind Persistence

The wind persistence index is a key parameter for analyzing wind field variation patterns. It is defined as the ratio of the vector average wind speed to the scalar average wind speed at each time point [27]. Let Pj represent the wind persistence at time j for a given station. For day i (out of M total days), the measured wind speed at time j is denoted as Sij, the wind direction as Dij, and the wind vector components as Uij and Vij. The calculation method for wind persistence is as follows:

A higher wind persistence index value indicates greater consistency in the wind direction. A persistence value of 1 indicates that the wind direction remains the same every day over the specified period, while values less than 1 indicate variability in direction. A persistence value of 0 occurs when winds are equally likely to come from all directions, or when the duration of wind from one direction is equal to that from the opposite direction.

Identification of Valley Wind Days

Valley winds are mesoscale circulations driven by local thermal differences, typically occurring over sloping surfaces such as mountain slopes and valley. These circulations are most pronounced under weak synoptic-scale weather conditions, with clear or partly cloudy skies and no precipitation [50]. To systematically identify days with typical valley wind characteristics, referring to relevant research methods [51,52], this study adopts the absence of precipitation, clear or partly cloudy conditions, and low wind speeds as screening criteria, specified as follows:

- Daily precipitation < 0.1 mm;

- Daily total solar radiation > 65% of the theoretical maximum direct radiation;

- Daily mean wind speed below the threshold for low-wind days.

The theoretical maximum daily direct radiation, H, is calculated as follows:

where ϕ is the station latitude and d is the day of the year.

Meteorological wind speed observation data typically adhere to, or can be approximated by, a Weibull distribution [53]. Utilizing the properties of this distribution, the threshold for defining low-wind days was established for each weather station and each summer month (June–August). First, the monthly average wind speed is calculated. Then, a subset S is formed containing all daily mean wind speeds lower than this monthly average. The low-wind threshold is defined as the mean of this subset minus 0.5 times its standard deviation:

Here, represents the average wind speed for month M, N is the total number of days in the month, is the daily mean wind speed on day i, and and represent the mean and standard deviation of the subset S, respectively. The wildfire case simulated in this study occurred on a day that met all the above criteria for a typical valley wind day. Based on this identification, synoptic circulation pattern analysis was also performed to confirm the occurrence of a valley wind day.

2.3.2. Wildfire Spread Characteristic Analysis

Wildfire Spread Simulation Method

Real-time observation of wildfire spread characteristics is challenging, making numerical simulation an essential tool. In this study, fire spread is simulated using the WRF-Fire model, which integrates two-way feedback between combustion and the meteorological environment [54].

The WRF-Fire model resolves atmospheric motions across scales ranging from tens of meters to hundreds of kilometers. However, the physical processes of combustion operate on scales much smaller than those resolved by the atmospheric model. As a result, WRF-Fire does not explicitly simulate the detailed physics and chemistry of combustion, but instead parameterizes fire spread using the widely applied Rothermel model [55].

The coupling process follows the framework outlined in [56,57,58]. At each time step, the WRF atmospheric module provides simulated near-surface meteorological variables—including wind fields, temperature, and humidity—to the fire module. Using these inputs, the fire module calculates the rate of fire spread, fireline intensity, and sensible and latent heat fluxes generated during fuel combustion, based on the Rothermel model. The calculated heat fluxes are then fed back into the atmospheric module as thermal forcing, which dynamically modifies local wind fields and atmospheric circulation, enabling bidirectional fire—atmosphere feedback.

Compared to other fire spread models, WRF-Fire offers unique multi-scale simulation capabilities, integrating processes across synoptic scales to fireline micro-scales. These capabilities facilitate the simulation of large-scale, long-duration wildfire behavior. The model employs a tightly coupled design between the fire and atmospheric modules, ensuring high computational efficiency and enabling real-time operational forecasting. As an open-source tool, WRF-Fire also provides transparency, extensibility, and robust community support, making it ideal for validation, development, and practical applications [59]. Several studies have demonstrated its reliability in reconstructing historical wildfire events [60,61,62,63].

This study utilized WRF version 4.3, with four levels of two-way grid nesting. The atmospheric domain resolutions were set at 27 km, 9 km, 3 km, and 1 km, respectively, with the fire model interacting within the fourth domain at a grid spacing of approximately 30 m. The entire simulation domain was composed of four nested layers, with the outermost domain spanning roughly 66° × 27° and the innermost domain covering about 1.5° × 1°. The simulation ran for 36 h on a single computing node equipped with 32 CPU cores, maintaining typical memory usage levels for WRF-Fire simulations of this scope. The total computational time was approximately 15 h, aligning well with operational forecasting requirements. The physical parameterizations employed included the WSM3 scheme for microphysics, RRTM for longwave radiation, Dudhia for shortwave radiation, Monin-Obukhov for the surface layer, and Noah-MP for land-surface processes. The YSU scheme was applied for planetary boundary layer parameterization in the first three domains, but deactivated in the fourth domain. Similarly, the Kain-Fritsch scheme was used for cumulus parameterization in the first two domains and disabled in the third and fourth domains.

Validation Method for Wildfire Spread

To validate the simulated fire spread, the burned area was derived by comparing pre- and post-fire Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. This derived burned area served as the reference ground truth for validation.

Pre- and post-fire Sentinel-2 images devoid of cloud cover were selected and subjected to radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction. Using Equation (14) [64], the pre-fire (NBRpre) and post-fire (NBRpost) indices were computed. The Near-Infrared (NIR) band is highly sensitive to vegetation, and its reflectance decreases after burning, while the Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) band helps distinguish between charred soil and residual vegetation. The difference between NBRpre and NBRpost was then calculated to generate the differenced Normalized Burn Ratio (∆NBR) image, which highlights fire-induced changes according to Equation (15). Higher ∆NBR values indicate more severe burn severity. Based on the ∆NBR image analysis, areas with ∆NBR > 0.1 were initially classified as “burned” and “unburned” to create a binary mask. This preliminary mask underwent post-processing to reduce noise. Finally, the refined raster mask was converted into a polygon vector file, serving as the ground truth burned area reference for subsequent comparison with simulated fire perimeters.

NBR = (NIR − SWIR)/(NIR + SWIR)

∆NBR = NBRpre − NBRpost

3. Results

3.1. Diurnal Wind Characteristics

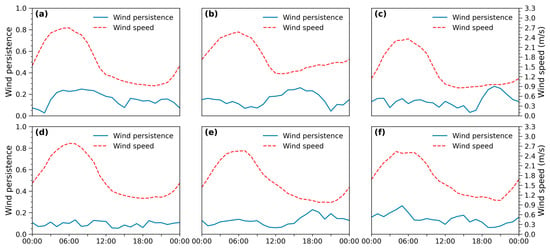

Analysis of the summer wind field characteristics reveals generally low prevailing wind speeds in the valleys of the study region, with daily average wind speeds ranging between 0.8 and 3 m/s. A distinct diurnal variation in wind speed was observed across all meteorological stations. Specifically, wind speeds were higher during the daytime (00:00–11:00 UTC) and lower at night (12:00–23:00 UTC). The average daytime wind speed was consistently 1.0 to 1.5 m/s higher than the nighttime speed. Wind persistence index analysis further indicates that values were generally low across all stations (below 0.4), reflecting significant variability in wind direction within the study area (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diurnal variations in average wind speed and wind persistence index at each meteorological station ((a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3, (d) S4, (e) S5, (f) S6).

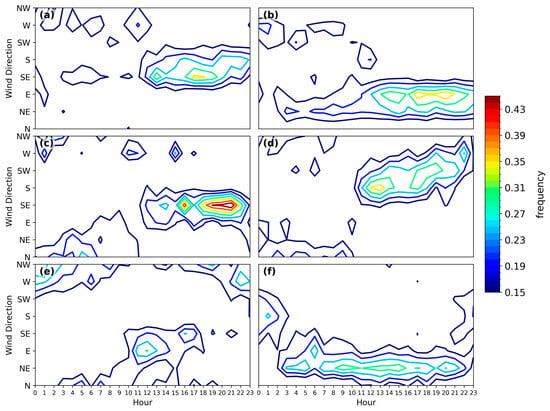

Further examination of the diurnal variation in wind direction frequency during summer valley-wind days (Figure 3) revealed that stations S1 to S5 exhibited relatively concentrated wind direction distributions at night, with more dispersed patterns during the day. These stations displayed opposing or nearly opposing wind direction between day and night, whereas station S6 showed consistent wind directions across both periods.

Figure 3.

Diurnal variation in wind direction frequency during valley-wind days at each meteorological station ((a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3, (d) S4, (e) S5, (f) S6).

At station S1, the prevailing daytime winds during valley wind days were westerly to northwesterly, while nighttime winds were southeasterly, reflecting a marked opposition. This reversed wind pattern is attributed to the mountain–valley breeze mechanism, with daytime up-valley winds (northwesterly) and nighttime down-valley winds (southeasterly), consistent with the station’s position at the outlet of a southeast-northwest oriented valley. Similarly, at station S2, daytime winds predominant from northeast and west, while nighttime winds shifted to the east, further illustrating the influence of mountain–valley breezes. Located at the confluence of a northeast-southwest oriented valley and an east–west oriented valley, S2 experiences daytime up-valley winds from the northeast and west, with nighttime down-valley winds primarily from the east, influenced by the steepest mountain gradient to the east.

At station S3, prevailing winds were northwesterly during the day and southeasterly at night, reflecting a typical mountain–valley breeze circulation pattern, similar to station S1. Station S4, located in an east–west oriented valley with low surrounding relief, showed northerly and northeasterly winds during the day, shifting to southerly and southwesterly winds at night. The station’s local circulation is influenced by topography to the south and southeast, resulting in daytime up-valley winds from the north and nighttime down-valley winds from the south.

Station S5, situated in the same east–west valley as S4, exhibited westerly winds during the day and easterly winds at night. This pattern is dominated by a north–south oriented mountain range to the south, resulting in daytime up-valley westerlies and nighttime down-valley easterlies. Station S6, located at the outlet of a northeast-southwest oriented valley and bordered by hilly terrain, exhibited prevailing northeasterly winds throughout the day and night. Unlike the other stations, the characteristic mountain–valley breeze pattern was not distinctly evident at S6.

In summary, analysis of all six meteorological stations in the study area indicates that summer wind speeds were generally low, with daytime winds typically stronger than nighttime winds. Wind field exhibited low persistence and high directional variability, with nighttime winds more concentrated than those observed during the day. Stations S1 to S5 were influenced by mountain–valley breeze circulations, whereas such patterns were not prominent at station S6.

3.2. Forest Fire Spread Characteristics

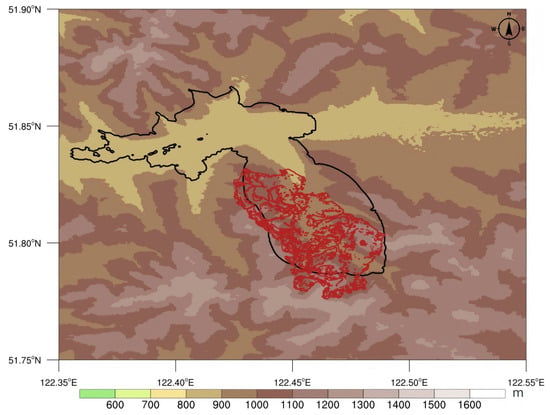

3.2.1. Validation of Spread Extent

Figure 4 presents a spatial comparison between the satellite-derived burned area and the fire perimeter simulated by the WRF-Fire model. The results show a high degree of agreement in mountainous regions. In regions where terrain is dominant (i.e., elevations above 800 m), the Sorensen similarity coefficient—a quantitative evaluation method used by Andrea T. et al. [65]—yielded a value of 0.82, indicating a strong spatial agreement between the simulated fire perimeter and the satellite-derived burned area. However, in valley regions the simulated burned area is generally larger than the satellite-derived result. This discrepancy likely arises from the inclusion of human fire suppression efforts—such as firebreaks and direct firefighting actions—in the satellite-derived data, which were not accounted for in the model simulation. Despite this overestimation in valley regions, the overall comparative analysis demonstrates that the WRF-Fire model successfully captured the primary spatial patterns and dynamic characteristics of the wildfire. Thus, the simulated fire spread behavior, particularly from the initial ignition to when the fire was primarily confined to mountainous terrain (08:00 UTC on 6 August to 12:00 UTC on 7 August), forms the basis for an in-depth analysis of the wildfire’s progression.

Figure 4.

Comparison between the satellite-derived burned area (red) and the model-simulated burned area (black).

3.2.2. Temporal Evolution of Fire Spread

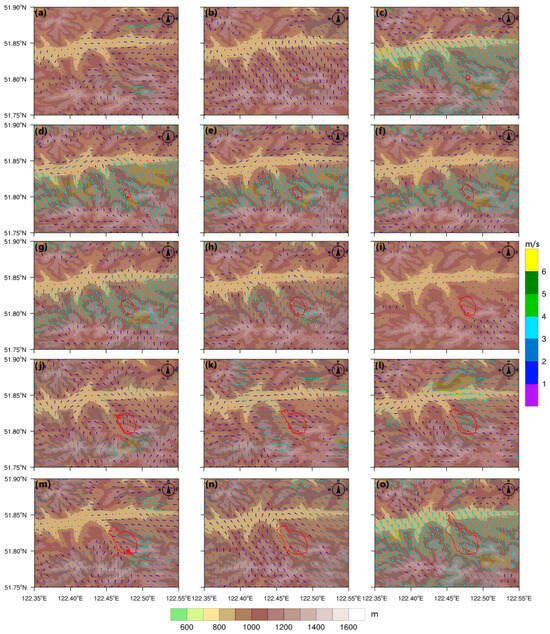

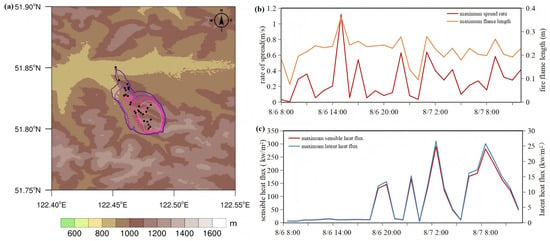

Phase 1 (08:00–10:00 UTC, 6 August): Initial Ignition and Development. This phase marks the onset of the fire, characterized by low wind speeds (1–3 m/s) in the vicinity of the fire. At ignition (Figure 5a), which occurred in the afternoon, the slopes heated more quickly than the valleys, causing air to rise along the slopes. This drew cooler air from the valley bottom upwards, generating upslope valley winds and drawing cooler air from the valley bottom upwards. This created upslope valley winds. In the large, north–south oriented valley V, simulated upslope winds of 1–2 m/s were observed on both sides of the valley. Initially westerly winds averaging 2–3 m/s dominated the fire area. However, by the evening (Figure 5b), winds shifted to southerly, with speeds ranging from 1 to 3 m/s. As the thermal contrast between the valley and the slopes diminished, the valley wind signature became less distinct. During this phase, the fire spread initially westwards, followed by a northward progression. The fire front reached the northern side with a maximum spread rate of 0.3 m/s, a maximum flame height of 0.2 m, and a peak heat flux of 11 kW/m2. Sensible and latent heat fluxes reached 10 kW/m2 and 1 kW/m2, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Two-hourly simulated evolution of the wind field (arrows: direction; color indicate speed), fire perimeter (red line), and underlying topography (shading) in and around the fire area. (a) 08:00 UTC, 6 August; (b) 10:00 UTC, 6 August; (c) 12:00 UTC, 6 August; (d) 14:00 UTC, 6 August; (e) 16:00 UTC, 6 August; (f) 18:00 UTC, 6 August; (g) 20:00 UTC, 6 August; (h) 22:00 UTC, 6 August; (i) 00:00 UTC, 7 August; (j) 02:00 UTC, 7 August; (k) 04:00 UTC, 7 August; (l) 06:00 UTC, 7 August; (m) 08:00 UTC, 7 August; (n) 10:00 UTC, 7 August; (o) 12:00 UTC, 7 August.

Figure 6.

(a) Hourly fire front locations (black dots) during the five spread phases and the final fire perimeters at the end of each phase (lines), overlaid on terrain elevation (shading). The red dot indicates the ignition point. (b) Time series of the maximum spread rate and maximum flame height. (c) Time series of the maximum released sensible heat flux and latent heat flux.

Phase 2 (10:00 UTC, 6 August–22:00 UTC, 6 August): Rapid Spread Period. In this phase, wind speeds increased appreciably (3–5 m/s, southerly), driven by the establishment of nocturnal mountain wind circulation, amplified by topographic dynamic effects. The prevailing southerly winds were obstructed by Ridge A, oriented east–west. Some airflow ascended over the ridge, while other portions diverged around the saddles (A1, A2) on the ridge’s flanks, creating zones of accelerated wind speed downstream of these features (Figure 5c–h). The combined effects of downslope mountain winds, gravitational acceleration, and flow diversion propelled the fire northwards rapidly. During this period, the fire front remained on the northern side, with a maximum spread rate of 1.1 m/s, a maximum flame height of 0.4 m, and a peak heat flux of 159.3 kW/m2. Sensible and latent heat fluxes peaked at 145.9 kW/m2 and 13.4 kW/m2, respectively (Figure 6).

Phase 3 (22:00 UTC, 6 August–03:00 UTC, 7 August): Deceleration Period. Wind speeds decreased to 1–2 m/s (southerly) during this phase, due to weakening synoptic flow and a shift in the thermal circulation. After sunrise, increasing solar radiation caused the transition from mountain wind to valley wind, leading to a negative feedback effect on the southerly background flow. Pronounced valley winds emerged in Valley V by 02:00 UTC on 7 August (Figure 5i–j). Fire spread continued northwestward but at a reduced maximum rate of 0.6 m/s, with the fire front shifting to the northwestern sector. The maximum flame height was 0.3 m, and the peak heat flux was 146.8 kW/m2. Sensible and latent heat fluxes of 134.4 kW/m2 and 12.3 kW/m2, respectively (Figure 6).

Phase 4 (03:00–09:00 UTC, 7 August): Western Expansion Period. During this phase, wind direction shifted to westerly, with speeds slightly increasing to 1–4 m/s (Figure 5k–m). The burned area expanded predominantly to the west. The fire front was located in the northwest, with a maximum spread rate of 0.6 m/s and a maximum flame height of 0.3 m. Tmakhe released heat flux peaked during this stage, reaching a maximum value of 246 kW/m2. Sensible and latent heat fluxes reached 225.3 kW/m2 and 20.7 kW/m2, respectively (Figure 6).

Phase 5 (09:00–12:00 UTC, 7 August): Sustained Spread Period. In this phase, the wind field shifted back to southerly, with a noticeable increase in speed by 12:00 UTC (Figure 5n–o). The burned area expanded mainly to the north. The maximum spread rate was 0.3 m/s, with the primary fire front located in the northwest. The maximum flame height was 0.2 m, and the peak heat flux was 179.3 kW/m2, with sensible and latent heat fluxes of 164.2 kW/m2 and 15.1 kW/m2, respectively (Figure 6).

The WRF-Fire model successfully captured the primary spatial pattern and dynamic characteristics of the wildfire event. The simulation results indicate that the fire spread process occurred in distinct phases, each strongly influenced by the wind field, which was primarily shaped by synoptic-scale background winds modified by local topographic forces. Throughout the fire’s progression, synoptic winds remained relatively weak, while local terrain influenced the direction and speed of the near-surface flow, through mechanisms such as upslope dynamic lifting and flow diversion—effects most pronounced during the rapid spread phase. Additionally, lee-side accelerated winds generated by topographic dynamic effects were particularly evident in this phase. Throughout the event, thermally driven valley wind circulations were also observed. For the fire located on the mountain slope, nocturnal mountain wind had a stronger influence than daytime valley winds.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research on mountainous wind systems. The observed diurnal pattern of valley winds during the day and mountain winds at night aligns with the classic model of thermally driven circulation in complex terrain [27]. However, a more detailed comparison reveals several advancements and distinctions. First, regarding the mountain–valley wind system, most classical studies in regions such as the Alps and Himalayas have focused on the genesis, spatial structure, and general diurnal patterns of circulation [50,51,52]. This study not only confirms similar patterns in the mid- to high-latitude forested region of the Greater Khingan Range but also quantifies key characteristics such as low wind direction persistence and more concentrated nighttime wind directions. These findings provide direct evidence for understanding the instability of the local wind field and its potential impact on nighttime fire behavior. Second, with respect to the inverse relationship between mountain and valley wind speeds and its effect on fire behavior, this study offers a concrete case. As Sharples [21] noted, extrapolating fire weather conditions from lowlands to high-elevation areas can lead to inaccurate fire behavior predictions, a point our results support. Lastly, this research, which integrates high-resolution wind field simulations with the dynamic progression of a real fire’s frontline, clarifies how the interaction between local mountain–valley winds and the background synoptic flow influences fire behavior across different spread phases. It confirms that, under weak synoptic forcing, terrain-driven wind fields significantly affect fire dynamics [59,66].

From both theoretical and management perspectives, this research highlights that, under weak synoptic forcing, diurnal local winds can become the dominant factor controlling fire spread. This insight has practical implications for fire management: suppression strategies should account for the diurnal wind cycle, particularly the contrast between strong high-elevation nighttime winds and stable valley-bottom conditions; fire risk assessment systems should incorporate localized wind patterns specific to complex terrain and treat data from valley stations with caution; and resource pre-positioning and allocation could be optimized by accurately identifying fire spread phases.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. First, the accuracy of fire behavior simulations depends on the near-surface meteorological fields generated by WRF, and uncertainties in initial and boundary conditions propagate into the fire module, especially in complex topography. Second, the semi-empirical fire spread parameterization scheme used in the model simplifies highly complex physical processes, potentially introducing systematic biases under certain conditions. Spatial heterogeneity in fuel parameters and the use of static datasets also introduce uncertainties in mass loss rates and heat flux calculations. Most importantly, as a single-case study, the physical mechanisms identified here are primarily relevant to fire events influenced by local mountain–valley breezes under weak synoptic conditions; broader applicability requires validation through additional case studies. Furthermore, validation relies on the final burned area extracted from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. Although the spatial resolution aligns with the simulation scale, the temporal discrepancy between satellite overpasses and actual fire progression means that validation reflects cumulative fire effects rather than instantaneous fireline positions—an inherent limitation of post-fire optical remote sensing validation.

Based on this discussion, future research could take several directions. First, applying this methodology to a broader range of wildfire cases under varying weather and fuel conditions would help assess the robustness of the identified mechanisms. Second, integrating advanced observation technologies, such as stereographic remote sensing, could provide a more accurate characterization of three-dimensional wind field structures. Developing dynamic, high-resolution fuel monitoring and modeling methods would significantly enhance the realism of model inputs. Additionally, the potential temporal relationship between fireline spread rates and heat release peaks observed in this study presents an intriguing scientific question. Future work could combine more detailed combustion physics models with high-temporal-resolution observations to better understand the coupling mechanism between fire spread and energy release. Ultimately, these efforts could provide a scientific foundation for developing customized fire spread prediction and decision-support systems for mountainous forested regions.

5. Conclusions

This study integrates statistical analysis of summer observational data from meteorological stations in the northwestern Greater Khingan Mountains over the past decade with a WRF-Fire model simulation of a wildfire event in the summer of 2023. The key conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Observational data from meteorological stations revealed that the wind persistence index was generally below 0.4, indicating high variability in wind direction and low stability in the region. Nighttime wind directions were more concentrated compared to daytime. Both observations and simulation results consistently showed distinct valley wind systems during summer valley-wind days. Specifically, upslope valley winds prevailed during the day, while downslope mountain winds dominated at night. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for the topographic context and the diurnal cycle of valley wind circulations in wildfire suppression strategies especially under weak synoptic conditions.

- (2)

- Analysis of meteorological data indicated generally low wind speeds in the valleys during summer, with a clear diurnal pattern—daytime winds were stronger than nighttime winds. Numerical model simulations of the wildfire event revealed that wind speeds in mountainous areas were typically higher than in valleys. Moreover, slope wind speeds exhibited an opposite diurnal pattern compared to those in the valleys, being higher at night. This difference is primarily driven by the combined effects of thermally induced mountain–valley breezes and gravitational acceleration. During the day, slope heating induces updrafts, dissipating horizontal momentum and reducing wind speeds. At night, radiative cooling leads to downslope drainage of colder, denser air, forming gravity-driven mountain winds that enhance wind speed. Conversely, valley winds during the day transport air from the valley floor to the slopes, creating convergence zones with higher wind speeds, whereas cold-air pooling at night results in temperature inversions that suppress mixing, reducing wind speeds. These findings suggest that firefighting strategies should differentiate between day and night conditions, taking into account the terrain at the fire front. Meteorological stations, often situated at lower elevations, may not represent wind conditions at higher-elevation fire lines accurately.

- (3)

- High-resolution simulations using the WRF-Fire model, validated against satellite-derived burned area data, demonstrated the model’s capability to accurately reproduce the macro-scale spatial pattern and dynamic evolution of the wildfire. The simulated fire perimeter showed agreement with satellite observations in mountainous regions. This study further leveraged these simulation results to analyze spatiotemporal wind field characteristics and dynamic fire behavior parameters—insights that are difficult to obtain directly through observations—providing a reliable basis for understanding the mechanisms driving the spread of the wildfire.

- (4)

- Analysis of the fire’s progression revealed that its behavior was strongly influenced by both wind and topography. The wildfire event was divided into five distinct phases, each characterized by specific spread rates, fireline locations, and energy release patterns closely linked to local wind field dynamics. During Phase 2 (Rapid Spread), a combination of nocturnal mountain winds and southerly background winds, enhanced by topographic lifting and flow diversion, created a strong wind corridor that accelerated the fire’s northward spread. In contrast, during Phase 3 (Deceleration), weakened synoptic background winds and the transition from mountain to valley winds led to reduced wind speeds and a corresponding decrease in the spread rate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and L.Z.; Methodology, Y.W. and L.Z.; Software, Y.W.; Validation, X.Y. (Xiaodan Yang); Formal analysis, Y.W. and J.S.; Resources, X.Y. (Xiaoyu Yuan); Data curation, Z.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, X.Y. (Xiaodan Yang), X.Y. (Xiaoyu Yuan), Z.W. and J.S.; Supervision, L.Z.; Funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Plan, grant numbers No. 2022YFC3003004 and No. 2023YFC3006800.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The WRF-Fire model simulation datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their large size, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The input boundary and initial conditions were obtained from publicly available reanalysis datasets (e.g., FNL).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, J.; Yue, C.; Wang, J.; Hantson, S.; Wang, X.; He, B.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Zhao, H.; Luyssaert, S. Forest Fire Size Amplifies Postfire Land Surface Warming. Nature 2024, 633, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation Fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Guan, D.; Zhu, S.; Kinnon, M.M.; Geng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Lei, T.; Shao, S.; Gong, P.; et al. Economic Footprint of California Wildfires in 2018. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.-T.; Lu, C.-H.; Alessandrini, S.; Kumar, R.; Lin, C.-A. The Impacts of Transported Wildfire Smoke Aerosols on Surface Air Quality in New York State: A Multi-Year Study Using Machine Learning. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 259, 118513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.W.; Bartlette, R.A.; Bradshaw, L.S.; Cohen, J.D.; Andrews, P.L.; Putnam, T.; Mangan, R.J. Fire Behavior Associated with the 1994 South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain, Colorado; Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-9; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1998; Volume 9, 82p. [CrossRef]

- Cheney, P.; Gould, J.; McCaw, L. The Dead-Man Zone—A Neglected Area of Firefighter Safety. Aust. For. 2001, 64, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.W.; Bartlette, R.A.; Bradshaw, L.S.; Cohen, J.D.; Andrews, P.L.; Putnam, T.; Mangan, R.J.; Brown, H. The South Canyon Fire Revisited: Lessons in Fire Behavior. Available online: https://www.frames.gov/catalog/3643 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Survey Report of “3·30” Forest Fire Event in Xichang City. Available online: https://www.scsqw.cn/whzh/slzc1/content_49723 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.M.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Pean, C.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; Matthews, J.B.R.; Berger, S.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Castellanos-Acuna, D.; Coogan, S.C.P.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Flannigan, M.D. Observed Increases in Extreme Fire Weather Driven by Atmospheric Humidity and Temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, R.C.; Jandt, R.; Miller, E.A.; Rogers, B.M.; Veraverbeke, S. Overwintering Fires in Boreal Forests. Nature 2021, 593, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello, K. Prepare for Larger, Longer Wildfires. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2017.22821#citeas (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Cochrane, M.A.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Manage Fire Regimes, Not Fires. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Giljohann, K.; Liu, Z.; Pausas, J.; Rogers, B. Novel Wildfire Regimes under Climate Change and Human Activity: Patterns, Driving Mechanisms and Ecological Impacts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2025, 380, 20230446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Wildland Surface Fire Spread Modelling, 1990–2007. 1: Physical and Quasi-Physical Models. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, C.D. Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-19-513271-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, R.G. Mountain Weather and Climate, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan, M.H.; Fox, D.G. San Antonio mountain experiment (SAMEX). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1981, 63, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, B.E. Atmospheric Interactions with Wildland Fire Behaviour—II. Plume and Vortex Dynamics. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, R.C. Mann Gulch Fire: A Race That Couldn’t Be Won; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1993; 10p. [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.J. An overview of mountain meteorological effects relevant to fire behaviour and bushfire risk. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, F. Local Winds. In Compendium of Meteorology: Prepared Under the Direction of the Committee on the Compendium of Meteorology; Byers, H.R., Landsberg, H.E., Wexler, H., Haurwitz, B., Spilhaus, A.F., Willett, H.C., Houghton, H.G., Malone, T.F., Eds.; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 1951; pp. 655–672. ISBN 978-1-940033-70-9. [Google Scholar]

- Banta, R.M.; Cotton, W.R. An Analysis of the Structure of Local Wind Systems in a Broad Mountain Basin. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1981, 20, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, J. Thermally Forced Flows: Theory. In Atmospheric Processes over Complex Terrain; Banta, R.M., Berri, G., Blumen, W., Carruthers, D.J., Dalu, G.A., Durran, D.R., Egger, J., Garratt, J.R., Hanna, S.R., Hunt, J.C.R., et al., Eds.; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vergeiner, I.; Dreiseitl, E. Valley Winds and Slope Winds—Observations and Elementary Thoughts. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 1987, 36, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, C.D. Observations of Thermally Developed Wind Systems in Mountainous Terrain. In Atmospheric Processes over Complex Terrain; Banta, R.M., Berri, G., Blumen, W., Carruthers, D.J., Dalu, G.A., Durran, D.R., Egger, J., Garratt, J.R., Hanna, S.R., Hunt, J.C.R., et al., Eds.; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman, C.D.; Bian, X.; Sutherland, J.L. Wintertime Surface Wind Patterns in the Colorado River Valley. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1999, 38, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardi, D.; Whiteman, C.D. Diurnal Mountain Wind Systems. In Mountain Weather Research and Forecasting: Recent Progress and Current Challenges; Chow, F.K., De Wekker, S.F.J., Snyder, B.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 35–119. ISBN 978-94-007-4098-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, J.; Kuwagata, T. Enhancement of Forest Fires over Northeastern Japan Due to Atypical Strong Dry Wind. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1992, 31, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marxer, P.; Conedera, M.; Ambrosetti, P.; Della Bruna, G.; Spinedi, F. The 1997 Forest Fire Season in Switzerland. Int. For. Fire News 1998, 18, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.A. Development and Mechanisms of the Nocturnal Jet. Meteorol. Appl. 2000, 7, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H. Forest Fire Situation in Republic of Korea. Int. For. Fire News 2002, 26, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Westerling, A.L.; Cayan, D.R.; Brown, T.J.; Hall, B.L.; Riddle, L.G. Climate, Santa Ana Winds and Autumn Wildfires in Southern California. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2004, 85, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E. Impact of Antecedent Climate on Fire Regimes in Coastal California. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2004, 13, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Safford, H.; Fotheringham, C.J.; Franklin, J.; Moritz, M. The 2007 Southern California Wildfires: Lessons in Complexity. J. For. 2009, 107, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.J.; Mills, G.A.; McRae, R.H.D.; Weber, R.O. Foehn-like Winds and Elevated Fire Danger Conditions in Southeastern Australia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1067–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, C.J.; Farnsworth, A. Fire Weather and Smoke Management. In Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 239–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauslar, N.J.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Marsh, P.T. The 2017 North Bay and Southern California Fires: A Case Study. Fire 2018, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, C.F.; Ovens, D. The Northern California Wildfires of 8–9 October 2017: The Role of a Major Downslope Wind Event. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, T.; Wang, X. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Primary Forest Growth in the Northern Daxing’an Mountains Based on Tree-Ring and NDVI Data. Forests 2024, 15, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.J.; Zhang, Z.X. The driving factors and their interactions of fire occurrence in Greater Khingan Mountains, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2674–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, D.; Feng, Z.; Li, X.; Li, X. Spatiotemporal patterns and risk zoning of wildfire occurrences in Northeast China from 2001 to 2019. Forests 2023, 14, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Yang, J.; Zu, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, J. Quantifying influences and relative importance of fire weather, topography, and vegetation on fire size and fire severity in a Chinese boreal forest landscape. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 356, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhou, G. Drivers of lightning-and human-caused fire regimes in the Great Xing’an Mountains. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 329, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Hu, H.; Tigabu, M.; Wang, G.; Zeng, A.; Guo, F. Geographically weighted negative Binomial regression model predicts wildfire occurrence in the Great Xing’an Mountains better than negative Binomial Model. Forests 2019, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Qu, Y.; Tao, S.; Hu, B. The Application of Quality Control Procedures for Real time Data from Automatic Weather Stations. Meteorol. Mon. 2008, 34, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global Land-Cover Product with Fine Classification System at 30 m Using Time-Series Landsat Imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.E. Aids to Determining Fuel Models for Estimating Fire Behavior; Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-122; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1982; Volume 122, 22p. [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, T.; Hato, M.; Kaku, M.; Iwasaki, A. Characteristics of ASTER GDEM Version 2. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2011; pp. 3657–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, L.; Laiti, L.; Serafin, S.; Zardi, D. The thermally driven diurnal wind system of the Adige Valley in the Italian Alps: Thermally Driven Wind System of Adige Valley. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 143, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.; Schmidli, J.; Hervo, M.; Haefele, A. Diurnal Valley Winds in a Deep Alpine Valley: Observations. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, H.; Weidinger, J. Spatio-temporal analysis of valley wind systems in the complex mountain topography of the Rolwaling Himal, Nepal. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, P.K.; Ahmed, S.; Warudkar, V. Comparative analysis of Weibull parameters for wind data measured from met-mast and remote sensing techniques. J. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, J.L.; Schroeder, W. The High Park Fire: Coupled Weather-Wildland Fire Model Simulation of a Windstorm-Driven Wildfire in Colorado’s Front Range. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, R.C. A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1972; 40p.

- Patton, E.G.; Coen, J.L. WRF-Fire: A coupled atmosphere–fire module for WRF. In Proceedings of the 5th WRF/14th MM5 Users’ Workshop, Boulder, CO, USA, 22–25 June 2004; National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR): Boulder, CO, USA, 2004; pp. 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, J.; Beezley, J.D.; Kochanski, A.K. Coupled atmosphere–wildland fire modeling with WRF 3.3 and SFIRE 2011. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011, 4, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, J.L.; Cameron, M.; Michalakes, J.; Edward, G.P.; Philip, J.R.; Kara, M.Y. WRF-Fire: Coupled Weather-Wildland Fire Modeling with the Weather Research and Forecasting Model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshaii, A.; Johnson, E.A. A review of a new generation of wildfire–atmosphere modeling. Can. J. For. Res. 2019, 49, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Krueger, S.K.; Jenkins, M.A.; Zulauf, M.A.; Charney, J.J. The Importance of Fire–Atmosphere Coupling and Boundary-Layer Turbulence to Wildfire Spread. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrinkova, N.; Jordanov, G.; Mandel, J. WRF-Fire Applied in Bulgaria. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Numerical Methods and Applications, Borovets, Bulgaria, 20–24 August 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, G.; Beezley, J.D.; Dobrinkova, N.; Kochanski, A.K.; Mandel, J.; Sousedík, B. Simulation of the 2009 Harmanli Fire (Bulgaria). In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Large-Scale Scientific Computing, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 6–10 June 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanski, A.K.; Jenkins, M.A.; Krueger, S.K.; Mandel, J.; Beezley, J.D. Real Time Simulation of 2007 Santa Ana Fires. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, C.H.; Benson, N.C. Measuring and Remote Sensing of Burn Severity: The CBI and NBR. In Proceedings of the Joint Fire Science Conference and Workshop, Boise, ID, USA, 15–17 June 1999; Neuenschwander, L.F., Ryan, K.C., Eds.; University of Idaho and International Association of Wildland Fire: Boise, ID, USA, 1999; Volume II, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trucchia, A.; D’Andrea, M.; Baghino, F.; Fiorucci, P.; Ferraris, L.; Negro, D.; Gollini, A.; Severino, M. PROPAGATOR: An operational cellular-automata based wildfire simulator. Fire 2020, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsaei, K.; Juliano, T.W.; Roberts, M.; Ebrahimian, H.; Kosovic, B.; Lareau, N.P.; Taciroglu, E. Coupled fire-atmosphere simulation of the 2018 Camp Fire using WRF-Fire. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.