Abstract

In this study, a new experimental method is proposed to evaluate the interaction between psychological state and behavioral changes under fire conditions. The ISO 5660-1 and the OFM (Open Field Maze) were employed to measure combustion characteristics and behavioral responses, respectively. Additional structure components were designed to establish appropriate inhalation environments with controlled temperature and uniform gas concentration within the OFM. A numerical simulation was then conducted to optimize these structural components for each inhalation method. The results confirmed that the proposed structures effectively provided proper thermal conditions and consistent gas concentrations inside the OFM. Therefore, the proposed experimental method improves the practicality and reliability of inhalation toxicology experiments. However, further research is required to enhance gas dispersion and to reduce excessive thermal effects under different inhalation conditions.

1. Introduction

Fire is one of the most representative disasters that causes not only severe physical damage but also significant psychological effects on human life. Long-term inhalation of toxic gases generated during fires, such as COx, NOx, SOx, and soot, can lead to pulmonary inflammation and even tumor formation [1,2]. Therefore, research on inhalation toxicology is crucial, not only for improving human health but also for enhancing the accuracy of fire-driven evacuation models.

Toxic gases released during a fire can alter evacuees’ behavior, as exposure to smoke and toxic substances leads to psychological instability and anxiety [3,4,5]. In general, many panicked evacuees tend to follow familiar routes during evacuation, even when these routes lead toward smoke-filled or fire-affected areas [6,7,8].

Accordingly, various studies have been conducted to incorporate psychological states into evacuation simulations. Helbing et al. [9,10,11] proposed the social force model, which converts psychological characteristics into forces that drive pedestrian movement. However, this model does not account for direct interactions between fire and evacuees. To address this limitation, Bae et al. [12,13,14,15] developed a new behavioral model that considers behavioral changes under fire conditions by introducing additional forces, such as radiation and smoke forces, representing the psychological pressure induced by fire.

Despite these advancements, the accuracy and reliability of such models remain limited due to the lack of experimental validation. Most existing studies on inhalation toxicology have focused on physiological responses to toxic substances, such as inflammation or DNA damage, rather than behavioral or psychological effects [16,17]. Furthermore, conventional acute inhalation test methods (e.g., OECD TG 403 and TG 436) [18] primarily analyze physiological responses to refined toxic materials. Similarly, the Korean Standard KS F 2271 [19] evaluates the gas toxicity of building finishing materials based on the LD50 of test animals. However, these methods cannot assess the psychological impact of toxic gases on behavioral changes because they focus only on quantifying the toxicology of each toxic material.

Therefore, there is a need for an integrated experimental approach that simultaneously evaluates the toxicological and behavioral effects of fire-generated gases. To meet this need, the present study proposes a new experimental method that combines inhalation toxicology with behavioral analysis. Furthermore, numerical simulations were performed to optimize the control conditions and structural design of each experimental setup, ensuring that both physiological and behavioral data can be reliably obtained under controlled fire conditions.

2. A New Experimental Method

In this study, a new experimental method is proposed to evaluate both the toxicological effects of combustion gases and the behavioral influence of psychological changes under fire conditions. To achieve this, appropriate experimental equipment must be selected to measure both the toxicological and behavioral responses during the inhalation of combustion gases.

First, the concentration of combustion gases is a key factor for quantifying toxicological effects. Therefore, ISO 5660-1 [20] was adopted to quantify combustion gas concentration, as it is a widely used method for measuring combustion characteristics such as heat release rate, gas concentration, and soot density.

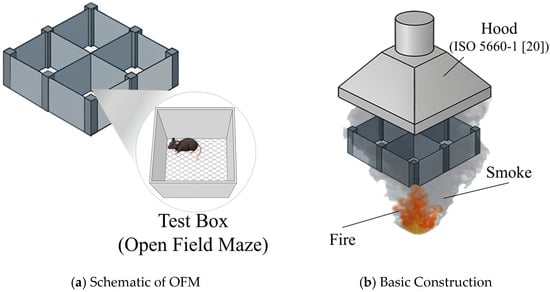

Next, the OFM [21] (Figure 1a) was employed to assess the influence of psychological changes on behavioral characteristics during exposure to combustion gas [16,17]. The OFM is one of the most widely applied experimental methods for analyzing the correlation between psychological anxiety and behavioral responses.

Figure 1.

Schematics of the suggested experimental equipment.

Subsequently, a new experimental setup was designed by combining these two systems, the ISO 5660-1 and the OFM, to enable simultaneous evaluation of combustion gas toxicity and behavioral changes. However, several design considerations were necessary to minimize the interference between the two devices and to establish realistic inhalation conditions for the combustion gases.

As shown in Figure 1b,c, the OFM can be positioned between the fire source and the hood of the ISO 5660-1 to minimize the time lag between combustion and measurement and to maintain stable visibility for video observation. In this configuration, the gas concentration inhaled by the test animals can be measured in real time. However, this setup does not fully represent the actual conditions of smoke inhalation in a fire scenario.

Alternatively, as shown in Figure 1d, the OFM can be placed beside the fire source to simulate the development of a smoke layer, thereby providing a more realistic inhalation environment. In this case, however, the real-time measurement of gas concentration becomes difficult, and visual observation of the OFM may be obstructed by soot and water vapor generated during combustion.

Therefore, the structural effects on gas concentration and the imaging system must be analyzed to optimize the proposed method. In this study, a series of numerical simulations was conducted to investigate these structural influences and to determine the optimal configuration for evaluating inhalation toxicology under controlled fire conditions.

3. Numerical Details

3.1. Computational Domain

In this study, numerical simulations were performed using Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS, version 6.8) to optimize the newly proposed experimental method. FDS is a widely used computational tool for analyzing smoke movement and gas concentrations under fire conditions. Therefore, it is particularly suitable for evaluating soot density around the OFM and the gas distribution within it.

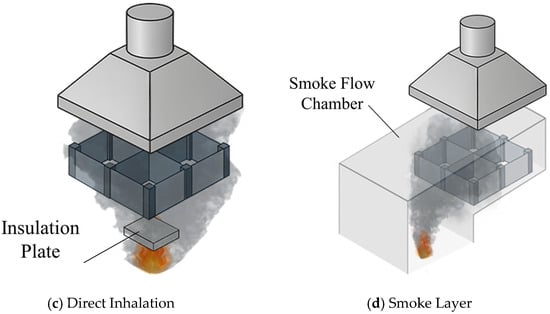

To analyze the structural influence of each test configuration, identical computational domains were constructed for all cases, even though the experimental structures varied depending on the inhalation method. As shown in Figure 2, the computational domain was set to 2.0 m (L) × 1.0 m (W) × 1.6 m (H) to simulate both structural cases identically. Within this domain, a square hood (1.0 m side length) representing the ISO 5660-1 system was positioned at the top right corner. The OFM, consisting of four test boxes (each 0.4 m × 0.4 m × 0.4 m), was placed 0.2 m below the hood. The fire source was located at the bottom of the domain, and its horizontal position was adjusted according to the simulation case, as defined by the inhalation method.

Figure 2.

Computational domains for each inhalation method.

Additional components, such as insulating plates and smoke flow channels, were incorporated to establish uniform inhalation conditions in the OFM for each case. For the direct inhalation case, an insulating plate (0.4 m × 0.4 m × 0.04 m) was installed 0.3 m below the OFM to reduce gas temperature and equalize gas distribution. For the smoke-layer case, a smoke flow channel (1.6 m × 1.0 m × 0.6 m) was applied, as illustrated in Figure 2, to promote the development of a smoke layer around the OFM.

3.2. Simulation Conditions

Table 1 lists the boundary conditions for each simulation case. The heat release rate (HRR) of the fire source was uniformly assumed to be 20 kW for all cases, and the outlet flow rate at the hood was set to 0.41 m3/s. All structures, including the hood, OFM, plate, and channel, were modeled as adiabatic materials to isolate structural effects on the proposed method.

Table 1.

Boundary conditions for each case.

Simulation cases were classified according to both the inhalation method and the presence of structural installations. Specifically, two inhalation methods, direct inhalation and smoke-layer inhalation, were analyzed, with and without additional structures such as an insulating plate and a smoke flow channel. This classification allowed for the evaluation of structural influences on gas concentration variations and thermal distributions.

3.3. Grid Independent Test

The accuracy of simulation results in FDS depends heavily on the grid resolution because Large Eddy Simulation (LES) is used as the turbulence model [22]. Therefore, a grid independence test was performed to minimize grid-size dependency in the simulation results.

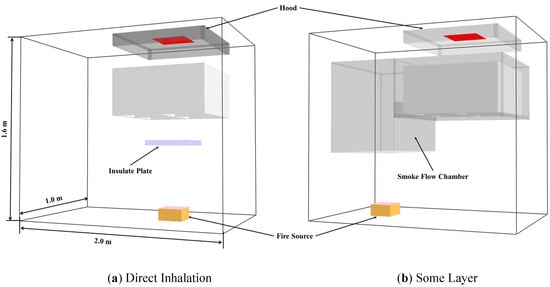

In this test, the vertical temperature distribution at the center of the fire source was compared using grid sizes of 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 cm.

Figure 3 shows the vertical temperature distribution for each grid size. As shown in Figure 3, the temperature profiles converged as the grid size decreased, with negligible differences observed between grid sizes of 1.25 cm and 1.5 cm. Table 2 lists the conditions and results of the grid independence test. As expected, the total CPU time increased sharply as the grid size decreased due to the larger number of computational cells. Based on these findings, a grid size of 1.5 cm was selected as the optimal balance between computational accuracy and efficiency for all subsequent simulations.

Figure 3.

Vertical temperature distributions for each grid size.

Table 2.

Conditions and Results of Grid Independent Test.

4. Results and Discussion

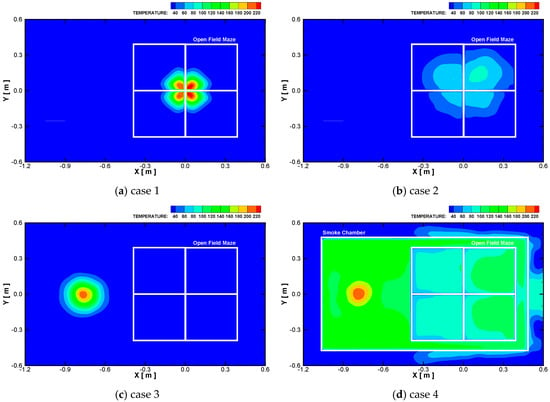

The temperature distribution inside the OFM is an important factor in the proposed experimental method because excessive thermal conditions can cause injury to the test animals. Therefore, in this study, the temperature distributions inside the OFM were obtained by time-averaging during the steady-state phase of the fire source, from 30 to 80 s.

Figure 4 presents the temperature contours at a height of z = 1.2 m for each case. As shown in Figure 4a, a steep temperature gradient was observed inside the OFM when the direct inhalation method was applied without any additional structure. The maximum temperature at the center of the OFM was approximately 230 °C, while the minimum temperature near the edge was about 20 °C.

Figure 4.

Temperature contour at z equals 1.2 m plane.

To mitigate this temperature difference, an adiabatic plate was introduced. Figure 4b shows that applying the plate significantly reduced the temperature gradient inside the OFM, as it disrupted the fire plume and promoted more uniform mixing of the combustion gases. As a result, the maximum temperature decreased from 229.98 °C to 84.32 °C, while the minimum temperature increased from 21.08 °C to 34.34 °C.

In contrast, Figure 4c shows that in the smoke-layer method without any structural modification, the temperature distribution inside the OFM was minimally affected by the fire source. To better simulate realistic smoke-layer development, a smoke flow chamber was added, as shown in Figure 4d. With this structure, the influence of the fire plume became evident, increasing the maximum temperature from 20.55 °C to 110.46 °C.

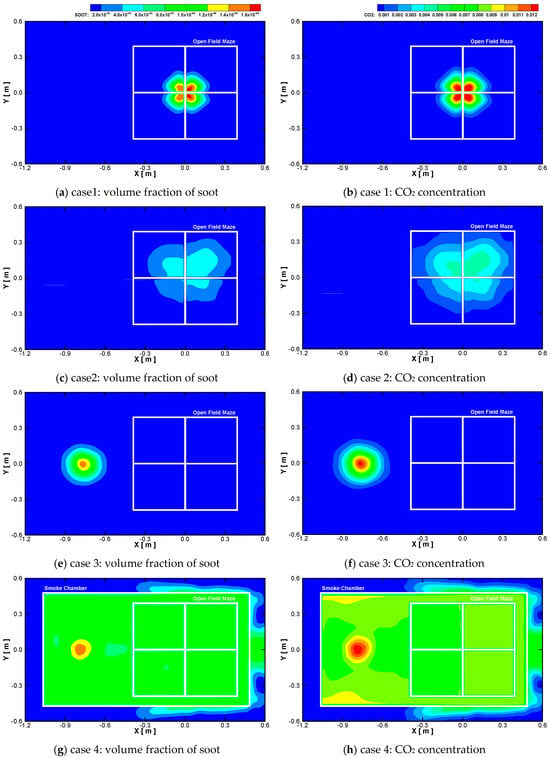

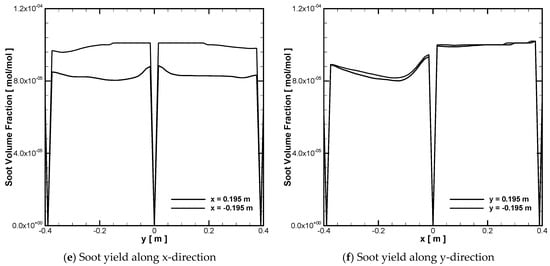

Figure 5 illustrates the distributions of soot and CO2 for each case. The gas concentration patterns closely followed the temperature distributions inside the OFM. In general, combustion gases diffused radially from the fire plume center, following the convective flow of the hot gases. In the absence of heat sinks or barriers, the thermal field and flow field exhibited similar spatial patterns.

Figure 5.

Distributions of the combustion gases, soot, and CO2.

Based on these results, the two cases with structural modifications, Case 2 (adiabatic plate) and Case 4 (smoke flow chamber), were selected for detailed analysis of smoke conditions. The temperature and gas concentrations inside the OFM were again obtained as time-averaged values during the steady-state condition of the fire source.

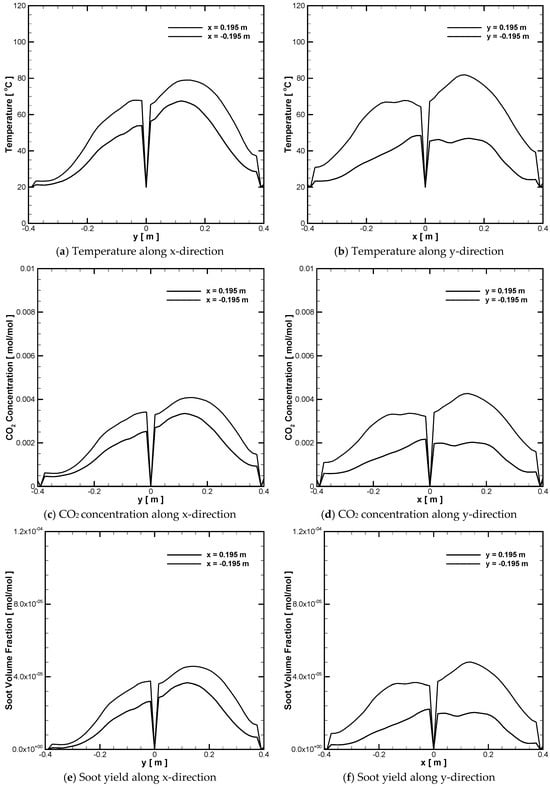

Figure 6 shows the temperature distributions and gas concentrations along the centerlines of the OFM in Case 2. Significant variations were observed among the four test boxes, particularly in the CO2 concentration and soot yield profiles. These differences likely resulted from the size and position of the adiabatic plate, which affected local gas flow patterns.

Figure 6.

Temperature distributions and gas concentrations along the centerlines for case 2.

Nevertheless, the application of the adiabatic plate substantially improved the thermal conditions within the OFM, reducing the maximum temperature by approximately 145 °C compared to the unmodified case. Further adjustments to the plate geometry and placement are recommended to achieve even more uniform smoke and gas distributions.

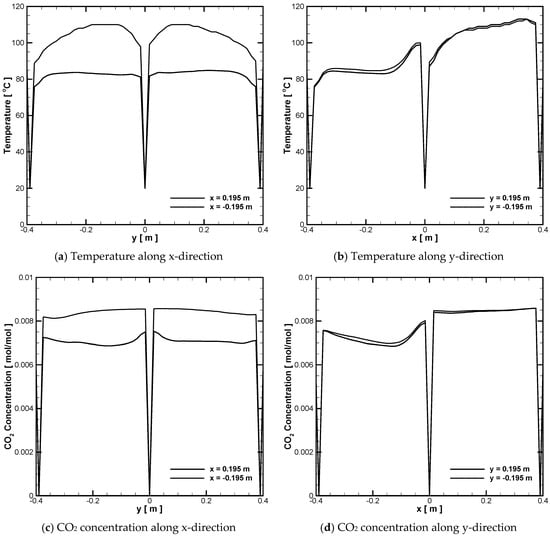

Figure 7 presents the temperature and gas concentration profiles for Case 4. The smoke flow chamber significantly decreased the differences in temperature and gas concentration among the test boxes, indicating a more homogeneous smoke environment. However, minor variations along the x-direction were observed due to density discontinuities at the corners of the chamber.

Figure 7.

Temperature distributions and gas concentrations along the centerlines for case 4.

These discrepancies could be mitigated by modifying the chamber geometry, such as adjusting its height or inlet position. However, it should be noted that the overall thermal level in this case was higher than in Case 2, by approximately 30 °C on average. Therefore, additional cooling or flow control mechanisms are required to reduce excessive heat while maintaining uniform smoke conditions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a new experimental method was proposed to evaluate both the toxicological effects of combustion gases and the behavioral influences of psychological changes under fire conditions. The ISO 5660-1 and the OFM were combined to measure combustion characteristics and to analyze the relationship between psychological anxiety and behavioral responses, respectively. Numerical simulations were also performed to optimize additional structures that provide appropriate thermal and gas concentration conditions within the OFM.

The key findings of this study are summarized as follows:

- The direct inhalation method enabled simultaneous analysis of combustion gas concentrations and their behavioral effects. The inclusion of an adiabatic plate effectively reduced plume temperature and promoted uniform gas dispersion inside the OFM, resulting in more stable thermal conditions across the test boxes. However, noticeable variations in temperature, soot density, and CO2 concentration remained among the boxes. Additional optimization of the plate geometry and position is therefore required to achieve uniform combustion gas distributions.

- The smoke-layer inhalation method provided a more realistic representation of smoke behavior during fire exposure, as it reproduced the natural movement of combustion gases within a confined space. The smoke flow chamber generated a consistent smoke layer and distributed gases more uniformly across the OFM. Nevertheless, the thermal level in this configuration was relatively high, approximately 30 °C greater than that of the direct inhalation method, indicating that further improvements are needed to reduce heat accumulation within the OFM.

- The proposed experimental method improves the practicality and reliability of inhalation toxicology by integrating toxicological and behavioral assessments under controlled fire conditions. However, additional studies are required to enhance gas dispersion uniformity and to further reduce thermal intensity for each inhalation method.

Author Contributions

Software, S.B.; Formal analysis, S.Y.J. and H.I.; Data curation, H.I.; Writing—original draft, S.Y.J.; Writing—review & editing, S.B. and Y.S.; Supervision, Y.S.; Funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the research fund from Chosun University (K207896003), This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Climate, Energy, Environment (MCEE) of the Republic of Korea. (No. RS-2025-07852969).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rehberg, S.; Maybauer, M.O.; Enkhbaatar, P.; Maybauer, D.M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Traber, D.L. Pathophysiology, management and treatment of smoke inhalation injury. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2009, 3, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Magun, B.E.; Wood, L.J. Lung inflammation caused by inhaled toxicants: A review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 11, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuligowski, E.D.; Kuligowski, E.D. Modeling Human Behavior During Building Fires; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy, R.F.; Proulx, G. Human behavior in the world trade center evacuation. In Proceedings of the International Association for Fire Safety Science, Fifth International Symposium, Melbourne, Australia, 3–7 March 1997; pp. 713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Fany, R.; Proulx, G.; Hershfield, V. A study of human behavior during the World Trade Center evacuation. NFPA J. 1995, 89, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y. Why do people make risky decisions during a fire evacuation? Study on the effect of smoke level, individual risk preference, and neighbor behavior. Saf. Sci. 2021, 140, 105245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Seike, M.; Fujiwara, A.; Chikaraishi, M. Negative emotion degree in smoke filled tunnel evacuation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 153, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, N.W.; Codling, E.A. Human exit route choice in virtual crowd evacuations. Anim. Behav. 2013, 86, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Farkas, I.; Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 2000, 407, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbing, D. A fluid dynamic model for the movement of pedestrians. arXiv 1998, arXiv:cond-mat/9805213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.; Ryou, H.S. A mathematical modeling of the evacuee’s psychological stress from the fire. Saf. Sci. 2014; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.; Ryou, H.S. Development of a smoke effect model for representing the psychological pressure from the smoke. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Choi, J.H.; Ryou, H.S. A modified fire effect model on evacuation by considering the psychological anxiety caused by the fire. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 2, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, C.; Hong, W.H.; Ryou, H.S. Development of new evacuation model (BR-radiation model) through an experiment. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, J.H.; Ha, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, I.; Bae, S. An exploratory study of the relationships between diesel engine exhaust particle inhalation, pulmonary inflammation and anxious behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Bae, S.; Yu, D.; Yang, H.S.; Yang, M.J.; Lee, J.H.; Ha, J.H. Dietary intervention with quercetin attenuates diesel exhaust particle-instilled pulmonary inflammation and behavioral abnormalities in mice. J. Med. Food 2023, 26, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Environment Directorate Joint Meeting of the Chemicals Committee and the Working Party on Chemicals, Pesticides and Biotechnology; Guidance Notes for Analysis and Evaluation of Repeat-Dose Toxicity Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Stand. KS F. 2271; Fire Retardant Testing Method of Interior Finishes and Structures. Anon: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006.

- ISO 5660-1; Reaction to Fire Tests—Heat Release, Smoke Production and Mass Loss Rate—Part I: Heat Release. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Nordquist, R.; Meijer, E.; van der Staay, F.J.; Arndt, S.S. Pigs as Model Species to Investigate Effects of Early Life Events on Later Behavioral and Neurological Functions, Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; p. 1003. [Google Scholar]

- McGrattan, K.; Klein, B.; Hostikka, S.; Floyd, J. Fire dynamics simulator (version 5), user’s guide. NIST Spec. Publ. 2010, 1019, 1–186. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.