Abstract

As an emerging development field, in recent years, emergency industrial parks in China have faced increasingly complex and high-risk challenges. This article proposes the establishment of a scientific safety risk assessment and grading model to help improve the safety management level of emergency industrial parks, in response to the problems of the multi-source heterogeneity of fire risks in emergency industrial parks and the difficulty of comprehensive assessment using traditional methods. This approach combines enterprise type classification with multi-level assessment for the first time, effectively identifying high-risk links such as fires and explosions and playing an effective role in preventing accidents such as fires in the park. Enterprises within the park are categorized into seven distinct groups based on their characteristics and associated safety risks: medical and healthcare, new energy storage, composite materials and new materials, intelligent manufacturing, mechanical manufacturing, consulting and technical services, and construction and installation. The following models are constructed: (1) a risk assessment model based on AHP-FCE, which can assess the safety risk levels of individual enterprises and the industrial park at a macro level; (2) a risk grading model based on the risk matrix method, which can inspect and control specific risk sources at a micro level. The integration of these two methods establishes a comprehensive model for safety risk assessment and grading in emergency industrial parks, significantly improving both the accuracy and the systematic nature of risk management processes.

1. Introduction

The safety and emergency industry is a crucial component of new industrialization and stands as one of the strategic emerging industries that facilitate the synergistic interaction between high-quality development and elevated safety standards [1]. Since the State Council approved the country’s first national emergency safety industrial park, emergency industrial parks have grown nationwide. National emergency industrial parks are legally established development zones and industrial parks, as well as industrial areas that are strategically aligned with national planning. Their distinctive characteristics have resulted in exemplary industrial agglomeration and clustering. Typical emergency industrial parks in China include the Xuzhou Safety Science and Technology Industrial Park, Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (Nanhai) Intelligent Safety Industrial Park, Jiangmen Safety and Emergency Industrial Park, and Hefei Hi-Tech Zone Safety Industrial Park.

Unlike existing chemical industrial parks, emergency industrial parks not only have machinery manufacturing enterprises but also medical, new energy, and other enterprises. The diversity of enterprises leads to complex causes of accidents such as fires, which include lithium battery explosions and biological agent leaks. For emerging emergency industrial parks with complex accident triggers, traditional methods such as HAZOP rely too much on static data and are difficult to adapt to the dynamic risk evolution of emergency industrial parks [2]. They cannot handle the chain reaction caused by multiple types of enterprises in the park.

Due to the varying industrial focuses and risk profiles of different emergency industrial parks, customized management for each type of park is crucial. Insufficient risk identification and control within these parks can lead to severe accidents. In recent years, incidents have continuously occurred within these parks, such as the “2.28” explosion at Zhao County Industrial Park in Hebei Province [3], the “8.26” explosion at Tuochuang Industrial Park in Wuhan City [4], and the “2.11” explosion at Yeosu National Industrial Park in South Jeolla Province, Republic of Korea [5]. These incidents have resulted in significant property damage and even casualties. Investigations into the causes of these accidents reveal that a lack of effective risk assessment is one of the primary reasons for the failure to manage risks in a timely manner. Therefore, developing a reasonable safety risk assessment method is essential in reducing accidents and allocating resources effectively.

Scholars, both globally and domestically, have extensively studied risk assessment and grading methods for industrial parks. Shi [6] developed a dynamic grading model for major hazardous sources in chemical parks, focusing on accident-triggered domino effects. Shen [7] identified common safety risks in science and technology parks through on-site assessments and created a Bayesian network model for quantitative risk evaluation. Kadri et al. [8] studied overpressure domino effects in industrial plants, quantified the risks, and introduced a human vulnerability model. Ikwan [9] proposed a risk analysis method combining a risk matrix and FTA analysis, successfully assessing chemical storage tank leakage risks in an industrial park. Yin [10] developed the PSR model, integrating entropy and hierarchical analysis to classify lightning safety risks in Guangdong’s chemical parks, producing risk classification maps. Wang Yong et al. [11] used the QRA method to calculate personal and social risk values for a chemical park, finding both within acceptable limits. Zhang et al. [12] created a risk classification model for environmental emergencies in industrial parks, applying it to 12 parks in Jiangsu Province, revealing that 80% were high-risk. Cao [13] used the professional software CASST-QRA V2.1 developed by the Chinese Academy of Work Safety Sciences to analyze the risks of chemical industrial parks, combining hazardous source distribution, meteorological conditions, and environmental features to quantify individual and societal risks, providing scientific support for safety management. Kong et al. [14] established an indicator system to evaluate safety organization resilience in chemical parks, using a cloud–matter–element model to assess safety management levels. Yuan et al. [15] developed a disaster resilience evaluation system for chemical parks, integrating fuzzy matter–element and coupling coordination models to assess the overall and subsystem resilience. Wang et al. [16] designed a safety risk assessment system for chemical parks, using the AHP for indicator weighting and the fuzzy method to evaluate risks across the layout, production, infrastructure, emergency response, and safety management. Tao et al. [17]. created a safety risk assessment system for small and medium-sized industrial parks, incorporating an AHP–fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model to evaluate risks across 16 indicators and 53 factors.

In conclusion, existing research on safety risk assessment for industrial parks and the application of AHP-FCE has shown significant progress. However, practical applications still face challenges. Firstly, most studies focus on industrial parks as assessment objects, often targeting specific accident types or major risk sources, while models tailored to emergency industrial parks and specific enterprises within them are scarce. Secondly, the AHP-FCE method can identify high-risk enterprises but lacks a scientifically reliable quantitative approach to assess specific risk levels, limiting the assessment depth and effectiveness. This prevents safety managers from implementing reasonable risk management for emergency industrial parks. The AHP-FCE method combined with the risk matrix method is suitable for scenarios with limited data, reliance on expert judgment, and the need for rapid decision-making. In contrast, methods like Bayesian networks and machine learning are better for complex scenarios with abundant data and high-precision prediction needs. Therefore, the AHP-FCE and risk matrix method is chosen to assess the safety risks in emergency industrial parks. Compared to previous studies, this model integrates macro-level safety risk assessment with micro-level specific risk level evaluation, effectively identifying high-risk enterprises and potential accident risks (e.g., fires, explosions, poisoning). It enables the formulation of targeted recommendations, helping park management to mitigate risks and allocate resources effectively. This model provides a scientific basis for preventive measures, reducing the probability of safety accidents in emergency industrial parks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Basis and Method of Safety Risk Assessment Model in Parks

2.1.1. Classification of Typical Enterprises in the Park

In recent years, the rapid development of China’s emergency industry has given rise to numerous emergency industrial parks, each distinguished by its unique focus and specialization. These parks encompass critical domains such as mine safety, hazardous materials management, and emergency rescue, among others. The specialization of the enterprises within these parks not only fosters technological innovation and industry advancement but also significantly bolsters the national emergency response system. However, as the industry scales up and diversifies, the risks inherent within these parks have grown increasingly complex and severe. Consequently, the effective prevention and control of various risks remain pressing challenges for safety managers in emergency industrial parks. Given the substantial differences in the developmental priorities and specializations of enterprises, the uniform application of weighted assessment metrics across all types of enterprises is neither practical nor rational. To ensure the accuracy of the assessment, it is crucial to develop tailored weightings according to the specific type of enterprise. Therefore, over 10 existing emergency industrial parks were surveyed, and the enterprises within the parks were classified into seven major types based on their professional focus and characteristics, as presented in Table 1. This classification aimed to establish a corresponding weight allocation strategy that aligned with the distinct risk profiles and operational environments of each enterprise type in the safety assessment process. To verify the universality of this classification method, it was applied to categorize the enterprises within the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park. The results show that this method can accurately classify all the enterprises in the park based on their characteristics.

Table 1.

Categories of enterprises in the emergency industrial park.

2.1.2. Risk Assessment Model Based on AHP-FCE

(1) Selection and Feasibility Analysis of Evaluation Methods

In the field of safety assessment, selecting an appropriate method is crucial in accurately evaluating risks and formulating effective safety management measures, especially for emergency industrial parks. Currently, some commonly used safety assessment methods include qualitative and quantitative analysis methods, such as hazard and operability study (HAZOP), fault tree analysis (FTA), the Dow Chemical Company’s Fire and Explosion Index Evaluation Method (F&EI), and quantitative risk assessment (QRA). However, each of these methods has its limitations: qualitative methods such as HAZOP and what-if analysis, while capable of systematically identifying potential risks, often yield results that are descriptive and qualitative, making it difficult to quantify the specific degree of risk. Moreover, the evaluation process is time-consuming, relies heavily on the subjective judgment of experts, and is prone to overlooking risk factors. On the other hand, quantitative methods such as fault tree analysis and QRA, while capable of providing quantified risk data, are complex to operate, require large amounts of data, and demand a high level of expertise from evaluators. They are also susceptible to logical errors due to human factors, making it difficult to comprehensively identify hidden dangers.

In contrast, the analytic hierarchy process–fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (AHP-FCE) method combines the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative analysis, effectively overcoming the limitations of the aforementioned methods. The AHP method constructs a hierarchical structure, breaking down complex problems into multiple levels, and conducts weight allocation and consistency checks layer by layer, ensuring the scientific and rational nature of the evaluation. Meanwhile, the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method transforms qualitative indicators into quantitative data through membership functions, avoiding the subjectivity and uncertainty inherent in traditional qualitative methods. In practical applications, the AHP-FCE method establishes a multi-level, multi-indicator evaluation system; determines weights using the AHP method; and quantifies qualitative indicators through fuzzy comprehensive evaluation, achieving a comprehensive assessment of the safety status of chemical industrial parks. For example, in the safety assessment of a certain chemical industrial park, the AHP-FCE method derived an overall safety evaluation score of 0.85 [18], which falls into the “good” category, intuitively reflecting the park’s safety status and providing specific improvement recommendations. This method not only quantifies risks but also visually displays the weights and impact levels of various risk factors through fuzzy matrices, offering scientific risk control references for managers. Therefore, the AHP-FCE method demonstrates high feasibility and effectiveness in practical applications, providing a scientific basis for the safety management of chemical industrial parks.

(2) Construction of the Assessment Indicator System

The safety checklist method is a widely used assessment tool [19] designed to systematically evaluate the safety management and risk control practices of an organization at a macro level. In this paper, based on the specific characteristics of emergency industrial parks and following a field investigation, the assessment framework is structured according to the principles of “scientific, systematic, and feasible”. The emergency industrial park is divided into five assessment units: safety management and risk control, offline office buildings, office areas, production areas, storage areas, and R&D centers. This framework includes 11 primary indicators, 27 secondary indicators, and 77 tertiary indicators, as detailed in Appendix A. The assessment encompasses the enterprise’s safety management, emergency plans, facility and equipment operations, and safety operational procedures. The first-level indicators are employed to evaluate the overall level of comprehensive safety management at the macro level, such as the establishment and implementation of safety systems. The second-level indicators focus on more specific safety processes and risk mitigation measures, while the third-level indicators delve deeper into production and daily operations, covering aspects such as equipment maintenance, safety protocols, personnel training, and emergency drills. The assessment units and first-level indicators are presented in Table 2. The safety checklist method offers an initial, comprehensive screening of individual enterprises, highlighting weaknesses in areas such as safety management, risk control, and production processes. The assessment results of each enterprise reflect its safety level. This method provides a basis for macro-level safety risk assessment and offers the necessary foundation for safety risk grading and control analysis.

Table 2.

Construction of risk assessment indicators for enterprises in emergency industrial parks.

(3) AHP-FCE Risk Assessment Model

After constructing the safety checklist indicators, an appropriate method for the calculation of the weights of each indicator needs to be selected. In this study, the weights of the indicators were analyzed in detail using the hierarchical analysis method (AHP) [20], and the results of the weights based on expert (five or more professors in the field of safety assessment) ratings were obtained. The weight results require consistency analysis to reduce bias. The hierarchical analysis method effectively handles the relative importance between factors by constructing a multi-level decision-making structure, ensuring the scientific and rational nature of the assessment, and the steps for determining its weights are as follows.

a. Establishing the hierarchical structure. The aim level represents the enterprise’s safety risk level, with the first, second, and third indicator levels below.

b. Determining the judgment matrix. Experts are invited to score the first-, second-, and third-level indicators; compare the indicators according to the degree of importance; assign values using a 1–9 scale; and finally construct the judgment matrix.

c. Weights are calculated and consistency tests are performed to reduce errors. The judgment matrix consistency ratio, i.e., the CR value, meets the consistency requirement when CR < 0.1 and vice versa. The specific calculation method is as follows.

The sum product method of the AHP is used to solve the judgment matrix, as shown in Equation (1).

In the formula, represents the judgment value size of the relative importance of factor Bi to factor Bj for the overall evaluation objective A, which is determined by the relative importance of factor Bi to factor Bj. Meanwhile, n denotes the order (dimension) of the matrix.

According to Equation (2), vector normalization is performed.

The maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix is calculated using Equations (3) and (4).

where A represents the A–B judgment matrix, and W represents the weights.

The consistency indicator CI is calculated using Equation (5):

where λmax represents the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix.

The higher the consistency degree of the judgment matrix, the smaller the CI value. When CI = 0, the judgment matrix is completely consistent. However, inconsistency in the judgment matrix arises not only from the subjective inconsistencies in the decision-making process but also from the use of the 1–9 scale for pairwise comparisons, which may introduce further deviations from consistency. Simply setting an acceptable inconsistency standard based on the CI value is clearly inappropriate.

To obtain a consistency check threshold that is applicable to judgment matrices of different orders, the influence of matrix order must be eliminated.

In the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), the consistency ratio is introduced to address this issue. The average random consistency index RI is used as a correction factor to eliminate inconsistencies caused by the influence of the matrix order. The specific values are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Values for the average consistency indicator (RI).

The judgment matrix consistency ratio CR is calculated from Equation (6) to determine the level of test matrix consistency.

Under normal circumstances, when CR < 0.1, which means that the relative deviation of CI from n does not exceed one-tenth of the average random consistency index RI, the consistency of the judgment matrix is generally considered acceptable; this standard is primarily based on empirical data and statistical analysis. Through multiple Monte Carlo simulations, it has been observed that, when the consistency ratio (CR) is less than 0.1, the consistency of the judgment matrix typically meets the requirements for practical applications [21]. On the other hand, when CR > 0.1, it indicates that the judgment matrix deviates too much from consistency, and necessary adjustments must be made to the judgment matrix to ensure satisfactory consistency.

Prior to conducting expert evaluations, we developed a comprehensive on-site inspection checklist through field research and a literature review. Based on this foundation, we formulated an expert assessment scoring questionnaire. We invited over five industry experts to participate in multiple rounds of scoring iterations until we achieved stable evaluation results. The final validated scoring matrix was further confirmed through normalization verification using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), ultimately yielding a definitive scoring weight table. This table meticulously documents the weight values of three-tier indicators and specific scoring values for each evaluation item, with detailed information presented in Appendix B.

However, the weights of the evaluation indicators remain subject to subjective factors inherent in the expert scoring process, and the evaluation results inevitably involve a degree of ambiguity. To improve the reliability of the conclusions of the safety risk assessment of the emergency industrial park, the qualitative results of the hierarchical analysis method must be combined with other quantitative evaluation methods. For this reason, this study adopts a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE) model based on membership theory as a quantitative evaluation method [22], which effectively transforms qualitative results into quantitative ones, achieving precise quantitative analysis. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation typically involves the following steps.

a. Determine the set of evaluation factors U = {u1, u2, …, un}, where ui (i = 1, 2, …, N) are the evaluation factors, and N is the number of individual factors at the same level. This set constitutes the framework of the evaluation.

b. Determine the set of evaluation rating criteria V = {v1, v2, …, vM}, where vj (j = 1, 2, …, M) is the evaluation rating scale and M is the number of elements, i.e., the number of grades or the number of rubric slots. This set specifies the selection range of the evaluation results for a certain evaluation factor.

c. Determine the affiliation matrix.

Suppose that, for the ith evaluation factor ui, a single-factor evaluation is performed to obtain a fuzzy vector concerning vj.

Here, rij represents the degree to which factor u corresponds to v, where 0 < rij < 1. When a comprehensive evaluation is conducted for M elements, the result is an N times M matrix, known as the membership matrix R. Clearly, each row in this matrix represents the evaluation outcome for each single factor, and the entire matrix encapsulates all information obtained by evaluating the set of evaluation factors U according to the standard set V. This study uses expert scoring to determine the membership of qualitative indicators and applies membership functions to calculate the membership of quantitative indicators, thereby generating a rating set.

d. Conduct Multi-level Comprehensive Evaluation

Based on the principle of the maximum membership degree, we determine the evaluation grade to which the object belongs and provide an evaluation conclusion.

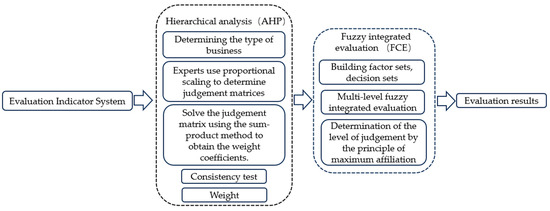

The AHP-FCE risk assessment model is constructed by integrating the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE) method. The technical roadmap of this model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Technical route of assessment model.

2.1.3. Application Method of the Risk Assessment Model

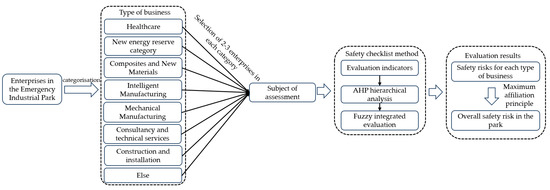

The AHP-FCE risk assessment model is applied to assess the safety risks in emergency industrial parks. The specific application steps are as follows.

(1) From the seven categories of enterprises in the emergency response industrial park (including medical and healthcare, new energy reserves, composites and new materials, intelligent manufacturing, machinery manufacturing, consulting and technical services, and construction and installation), one to three enterprises in each category will be randomly selected as assessment targets.

(2) For each enterprise type, the hierarchical analysis method is used to determine the weights of the evaluation indicators, ensuring the scientific rationality of the weight assignment.

(3) The weight-coupled fuzzy comprehensive evaluation is used to derive the comprehensive evaluation results, and we the principle of maximum affiliation for processing, seeking to derive the level of safety risk of each enterprise. Finally, again, we use the principle of the maximum membership degree to obtain the overall safety risk of the park. The risk assessment flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk assessment flowchart.

In the actual assessment process, certain enterprises are not involved in all of the assessment units set in this model. The missing assessment units will not be considered, and the remaining assessment units involved will be normalized according to their original weights. The adjusted weight values will be reset; such adjustments are designed to ensure the accuracy and reasonableness of the assessment results. Taking the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park as an example, the details are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Allocation of weights of assessment units for various types of enterprises in the emergency industrial park.

2.2. Research Basis and Application Results of Safety Risk Classification Model in Parks

Once the risk assessment model has identified high-risk enterprises, the risk matrix method is subsequently employed to classify the risk sources within each enterprise. This approach aims to determine the specific level of risk associated with each enterprise’s production process. Through risk identification and quantitative analysis, this methodology allows for a detailed assessment of both the probability of risk occurrence and its potential consequences. Based on this assessment, the severity of the risk is determined, and targeted control and corrective measures are proposed.

2.2.1. Risk Grading Model Based on the Risk Matrix Method

The fundamental principle of the risk matrix method is to determine the risk magnitude by multiplying the probability of an accident’s occurrence by the severity of its consequences [23]. The mathematical model of this is shown in the following equation:

where R is the risk; L is the frequency of accidents; and S is the severity of the consequences of accidents.

The accident frequency is categorized into five levels, with the specific values outlined in Table 5. The severity of the consequences is assessed based on factors such as casualties, equipment damage, and the impact on production and is also divided into five levels [24], as detailed in Table 6. The accidents considered in this context include hazardous events, such as fires, explosions, poisonings, and other potential risks that may occur in high-risk enterprises.

Table 5.

Values of accident frequency (L).

Table 6.

Values for the severity of the consequences of an accident (S).

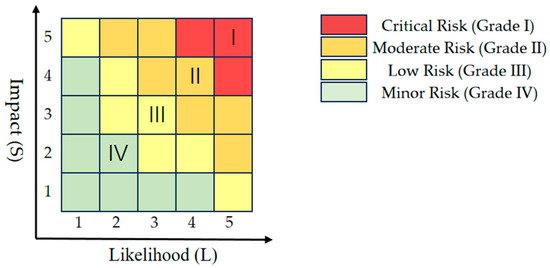

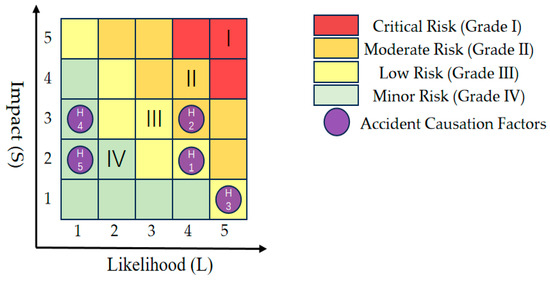

The risk matrix method categorizes risk levels into four grades, from high to low, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Risk classification matrix.

R = L × S = 17~25: critical risk (grade I), which requires elimination.

R = L × S = 10~16: moderate risk (grade II), which requires special control measures.

R = L × S = 5~9: low risk (grade III), which requires monitoring.

R = L × S = 1~4: minor risk (grade IV), which is acceptable or tolerable.

2.2.2. Application Method of the Risk Grading Model

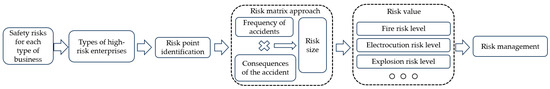

The risk matrix method is employed to classify the risks present in high-risk enterprises. Building upon the identification of high-risk enterprises through the risk assessment model, a detailed risk grading analysis is performed. The specific application process is outlined as follows.

a. A comprehensive on-site investigation was conducted for each selected enterprise to identify potential risks.

b. Based on the identified risks, the probability and consequences of the accident-causing factors were quantitatively assessed using the risk matrix method, assigning different scores to different types of risks and their severity, multiplying the frequency of accidents (L) with the severity of the consequences (S) to obtain the specific risk value (R), and grading the risk level from class I to class IV to assess the severity of each risk.

c. Based on the assessment results, risks categorized as high (class I and class II) in the risk matrix method are prioritized, with corresponding corrective measures proposed. These measures may include strengthening safety training, improving equipment, and optimizing emergency plans. For risks classified as low, long-term monitoring and preventive measures are implemented to ensure that they do not escalate into significant safety risks. The risk classification process is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Risk grading flowchart.

3. Results

3.1. Model Establishment

This paper presents a safety risk assessment and grading model for emergency industrial parks, integrating the AHP-FCE risk assessment model with the risk matrix method. The model enables the assessment of risk levels at both the park-wide level and for individual enterprises, while also identifying the potential risk levels of high-risk enterprises. Initially, the AHP-FCE model is employed to assess the overall risk level of the industrial park, determining whether the safety risk levels of each enterprise and the park as a whole are within acceptable limits and identifying high-risk enterprises. The model then incorporates the risk grading framework based on the risk matrix method to analyze the types of potential risks within high-risk enterprises, identify specific risk points, and assess the severity of these risks. Finally, corrective measures are proposed based on the results of the risk classification. The safety risk assessment and grading model is illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 4. This model not only provides an effective assessment of the overall safety management status of the emergency industrial park but also highlights the key risks of specific enterprise types, ensuring that high-risk points within the park are identified and controlled promptly, thereby enhancing the overall safety management level.

3.2. Case Study

This study combines the AHP-FCE method with the risk matrix approach to establish a safety risk assessment method for emergency industrial parks. Through model analysis, it was found that the safety risk level of an intelligent manufacturing enterprise in the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park was average (the worst among the evaluated enterprises). Therefore, this section presents the case analysis process of the intelligent manufacturing enterprise within the park to demonstrate the feasibility and reliability of the proposed model.

3.2.1. Calculation of Indicator Weights

To determine the relative importance of factors at each level of the evaluation hierarchy, five experts in the field of safety assessment were invited to conduct pairwise comparisons. The results of these comparisons were used to construct the AHP judgment matrix and distribute weights accordingly. To quantify the judgment matrix, the 1–9 scale method was adopted. Through expert consultation, the relative importance of factors in levels B, C, D, and E was evaluated, leading to the construction of the A–B, Bi–C, Ci–D, and Di–E judgment matrices. (Bi–C, Ci–D, and Di–E matrices omitted) The results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

A–B judgment matrix.

We take the process of calculating the weights of layer B indicators relative to layer A as an example, and we describe in detail the process of determining the weights, which mainly includes the following four steps.

a. Following Equations (1) and (2) presented above, calculate the arithmetic mean of all elements in each row of the judgment matrix:

The respective weight values were calculated using the aforementioned computational method and are presented in matrix form:

b. Normalize to obtain the weights of the factors in layer B relative to layer A. The results are presented in matrix form as follows:

c. Calculate the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix.

The eigenvectors of A are determined by Equations (3) and (4), and the maximum eigenvector is calculated = 5.357.

d. Consistency testing.

Based on Equations (5) and (6) presented earlier, calculate the consistency index of the judgment matrix and test its consistency:

Since the dimension n = 5, then, as obtained from the reference table, RI = 1.12.

The consistency ratio (CR) of each judgment matrix is less than 0.1, indicating that all matrices pass the consistency text.

Following the steps outlined above, the weights for levels B–C, C–D, and D–E were calculated sequentially, and consistency tests were conducted. The results are summarized in Table 8. The detailed consistency testing processes for levels C–D and D–E are omitted.

Table 8.

Indicator weights and consistency test results.

The weights of the evaluation indices of the enterprise in the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Weights of evaluation indicators for the enterprise in the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park.

3.2.2. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

a. Access to qualitative indicator rubrics

Experts were invited to assess the safety level of an enterprise in the Beijing Emergency Industrial Park once more, and a set of qualitative indicators was obtained, the results of which are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation matrix of the enterprise.

For instance, a group of five professors specializing in safety assessment were invited to evaluate the level of “E1” of the enterprise’s “production safety responsibility system”. One expert suggested that the degree of relevance was “poor”, and this opinion was divided by the total number of experts to obtain “poor”. Conversely, three experts considered the degree of relevance to be “average”, and one expert considered it to be “excellent”. The degree of affiliation was indicated as “0.2” for three experts and as “in” for one expert, with the latter also indicating an “excellent” degree of affiliation. The degree of affiliation of “excellent” was 0.6, 0.2, respectively. The fuzzy evaluation matrix of E1 is thus summarized as [0.2 0.6 0.2].

b. Level 1 integrated evaluation

The fuzzy operation results of each indicator in layer D are calculated according to the formula , where is the weight of each factor (El–E77) in the lower level of layer D relative to layer D, as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Layer D evaluation results.

c. Level 2 integrated evaluation

Di can be regarded as a single-factor judgment of layer C, and the fuzzy operation results of each index of layer C can be calculated according to formula , where is the weight of each factor of layer C (Dl–D27) relative to layer C. The comprehensive judgment of layer C is shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Layer C evaluation results.

d. Level 3 integrated evaluation

The calculation of the evaluation results for layer B is the same as for layer C. The calculation results of layer B are shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

Layer B evaluation results.

e. Level 4 integrated evaluation

The calculation of the evaluation results for layer A is the same as for layer B. The calculation results of layer A are shown in Table 14.

Table 14.

Layer A evaluation results.

f. Conclusions of the evaluation

The findings of this study indicate that 21.08% of the evaluated enterprises are likely to have a “poor” safety risk level, 39.68% are likely to have an “average” safety risk level, and 39.23% are likely to have an “excellent” safety risk level. According to the principle of maximum affiliation, among the three levels of affiliation, the value of 39.68% is the largest, indicating that the safety risk level of the evaluated enterprise is “average”. The level of risk present needs to be further assessed in conjunction with the safety risk assessment grading model.

3.2.3. Safety Risk Assessment Grading Model

Through research on the risk factors existing in the enterprise, it was found that there may be fire, electric shock, vehicle injury, and other risk factors in the enterprise at present. We take fire as an example of a risk factor to classify its risk, which may lead to the occurrence of fires, as shown in Table 15.

Table 15.

Results of a survey on the fire risk of the enterprise within the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park.

Using the risk matrix method, the fire risk of the enterprise is evaluated and quantified. The fire risk is divided into two dimensions: the probability of occurrence and the severity of the consequences. The probability of occurrence is set as the L value, and the severity of the consequences is set as the S value. The classification criteria for the probability of occurrence are shown in Table 5, and the classification criteria for the severity of the consequences are shown in Table 6. A value assignment is set between each level, and the specific results are presented in Table 16.

Table 16.

The fire risk assessment data for the enterprise.

The risk matrix diagram is drawn with the probability of accident occurrence on the horizontal axis and the severity of the accident’s consequences on the vertical axis. Based on the assessment data in Table 16, specific values for each risk coordinate are plotted. This serves as the basis for constructing the risk matrix diagram. By examining the location of risk points in the matrix, the importance level of each risk point can be visually observed, based on the quantitative assessment of both the occurrence probability and consequence severity. The specific diagram is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Risk matrix.

From Figure 5, it can be seen that, in order to reduce the fire risk in the company, specific control is urgently needed for issues such as improper electrical wiring and poor connections (H2), while particular attention should be given to problems like electrical overheating, aging, or overload (H1) and improper smoking or smoking in non-smoking areas (H3). The specific countermeasures can be rectified and improved based on the detailed items in the safety checklist. The ultimate goal is to raise the company’s safety risk level to the “excellent” grade.

It can be concluded from the entire evaluation process that, compared to other evaluation methods, the AHP-FCE and risk matrix method offers significant advantages. Firstly, this approach comprehensively considers multiple evaluation factors and processes fuzzy and uncertain information, resulting in more comprehensive and precise assessment outcomes. Secondly, through scientific weight allocation, it ensures the rational distribution of priorities among different risk factors. Additionally, it possesses the capability for the in-depth analysis of complex, multifaceted factors and the handling of fuzzy information, making its quantitative treatment of risks more reasonable. Therefore, this method is suitable for complex risk assessment tasks, and it can provide more accurate and reliable evaluation results.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The safety risks in emergency industrial parks vary depending on the type of enterprise, requiring a tailored assessment approach. This paper presents an in-depth study on the safety risk assessment and grading model for emergency industrial parks.

(1) Based on the characteristics of the enterprises within the emergency industrial park, the enterprises are categorized into seven main types, and the evaluation units are divided into five categories. This classification method covers the main types of enterprises and risk areas in the park and improves the comprehensiveness and precision of risk assessment grading.

(2) The method developed in this paper combines the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) with the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method to propose an evaluation system for the safety management of emergency industrial parks. This approach combines traditional quantitative techniques (e.g., QRA, FTA), which focus on numerical descriptions of risks, with qualitative frameworks (e.g., HAZOP), which produce descriptive results and are strong enough to address the challenges of emergency industrial park security management.

(3) The model combines macro assessment and micro grading to not only derive an overall security assessment score (e.g., the case study enterprise has an “average” risk level of 39.68%), but also pinpoint specific vulnerabilities through hierarchical fuzzy assessment matrices and risk coordinate visualization (Figure 5). For example, we identify critical fire risks such as improper wiring (H2, R = 12) and equipment overload (H1, R = 12). R = 8, reflecting the diagnostic accuracy of the method, which is often overlooked by traditional single-dimensional assessments.

(4) A case analysis of an intelligent manufacturing enterprise in the Beijing Fangshan District Emergency Industrial Park confirms the model’s effectiveness in identifying risks and proposing mitigation strategies, such as improving electrical wiring. The results indicate that the model is reliable in enhancing safety within emergency industrial parks.

(5) By combining the structural rigor of the analytic hierarchy process with the fuzziness of fuzzy evaluation, this model surpasses the limitations of independent quantitative/qualitative analysis and systematically solves the safety management defects at the macro level and the operational risks at the micro level. Risk heat maps and multi-layer score tables (Appendix B) provide actionable insights through visualized risk prioritization, a feature that is missing in traditional AHP implementations and often rests on weight calculations. This dual function—overall scoring combined with refined risk positioning—establishes a paradigm shift in emergency industrial park security management, enabling targeted resource allocation that aligns with regulatory compliance needs and operational risk reduction priorities.

(6) The AHP-FCE and risk matrix method have certain limitations, such as the potential inability to fully consider various risk factors in risk assessments, leading to biased results, and the complexity of the calculation process, which may cause difficulties in information integration. Future research could explore the integration of AHP-FCE and the risk matrix method with other approaches to optimize the assessment process and enhance the comprehensive evaluation capabilities. Additionally, developing dynamic evaluation models to monitor real-time risk changes could further improve the timeliness and adaptability of the assessments.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.C.; Software, A.P.; Validation, A.P. and Q.M.; Formal analysis, Z.C., A.P. and L.T.; Investigation, L.T.; Resources, A.P.; Data curation, Z.C. and L.T.; Writing—original draft, Z.C.; Writing—review & editing, Z.C. and Q.M.; Project administration, Q.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Construction of Risk Assessment Indicators for Enterprises within Emergency Industrial Parks.

Table A1.

Construction of Risk Assessment Indicators for Enterprises within Emergency Industrial Parks.

| Assessment Module—B | First-Level Indicator—C | Second-Level Indicator—D | Third-Level Indicator—E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety management and risk control | Regulations and governing documents | Mechanisms for management of production safety | Work safety accountability |

| Work safety assessment mechanism | |||

| Targeted management of production safety | |||

| Contractor management system | |||

| Safety training and education | Training plans | ||

| Training records | |||

| Education and training hours | |||

| Assessment of the effectiveness of safety education and training | |||

| Inputs to production safety | Safety cost management system | ||

| Plan for the use of production safety costs. | |||

| Extraction of production safety costs | |||

| Risk management and emergency response | Routine check-ups of hidden dangers | Safety risk and risk identification mechanism | |

| Frequency and coverage of safety inspections | |||

| Identification and rectification of hidden dangers | |||

| Major accident risk situation | |||

| Emergency preparedness and response | Emergency planning | ||

| Emergency exercise plan | |||

| Emergency exercise implementation | |||

| Emergency supplies and equipment | |||

| Emergency communications and information dissemination | |||

| Offline office space | Fire safety | Fire-fighting equipment and facilities | Completeness of the building’s fire protection system |

| Configuration and integrity of the enterprise’s firefighting equipment | |||

| Fire escape accessibility | |||

| Availability of emergency supplies | |||

| Electrical safety | Electrical equipment facilities | Maintenance of electrical equipment | |

| Electrical wiring regulation and safety | |||

| Electrical safety management system | Safety management system | ||

| Production area | Base building and environment | Building layout risks | Production area |

| Potential for expansion of the accident | |||

| Risk of meteorological conditions at the site | Extreme temperatures | ||

| Humidity changes | |||

| Inundation | |||

| Geological risks at the site | Geological conditions | ||

| Earthquake risk | |||

| Whole production process | Production equipment risks | Equipment structural integrity | |

| Equipment life expectancy | |||

| Maintenance of equipment | |||

| Production process risks | Potential for fire and explosion accidents | ||

| Potential for electrocution | |||

| Probability of fall-from-height accidents | |||

| Potential for poisoning accidents | |||

| Potential for object strike accidents | |||

| Possibility of mechanical accidents | |||

| Risks in the storage and transport of production materials | Type of material produced | ||

| Reasonableness of mode of transport | |||

| Pipeline status | |||

| Maintenance of equipment and facilities | Maintenance of equipment and facilities | ||

| Fire protection system | Monitoring and early warning systems | ||

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | |||

| Configuration of other fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Operation and maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Hazardous waste treatment | Solid, liquid, and gas waste treatment | ||

| Storage areas | Warehouse building design and environment | Building design | Reasonableness of mode of transport |

| Potential for expansion of the accident | |||

| Warehouse facility safety | Fire protection system | Monitoring and early warning systems | |

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | |||

| Configuration of other fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Operation and maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Maintenance of facilities | Maintenance of facilities | ||

| Warehouse cargo safety | Storage safety | Material type | |

| Material storage method | |||

| Storage of flammable, explosive, and toxic hazardous chemicals | |||

| Significant sources of danger | |||

| Transport safety | Inbound and outbound process standardization and safety | ||

| Cargo safety monitoring measures | |||

| R&D center area | R&D center facility safety | R&D center fire-fighting facilities | Monitoring and early warning systems |

| Configuration of fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | |||

| Operation of the fire-fighting system | |||

| R&D center electrical wiring and equipment | Safety of electrical equipment itself | ||

| Electrical wiring laying normality and safety | |||

| Whole process of experimental testing | Safety of laboratory equipment | Completeness of safety devices for experimental equipment | |

| Age of laboratory equipment | |||

| Maintenance of laboratory equipment | |||

| Experimental process risks | Operating temperatures | ||

| Operating pressure | |||

| Hazardous waste treatment | Solid, liquid, and gas waste treatment |

Appendix B

| Assessment Module—B | Evaluation Weight | First-Level Indicator—C | Evaluation Weight | Second-Level Indicator—D | Evaluation Weight | Third-Level Indicator—E | Evaluation Weight | Third-Level Index Evaluation Items | Evaluation Score |

| Safety management and risk control | 0.1 | Regulations and governing documents | 0.667 | Mechanisms for management of production safety | 0.548 | Work safety accountability | 0.532 | System improvement | 100 |

| Imperfect system | 60 | ||||||||

| Unestablished system | 0 | ||||||||

| Work safety assessment mechanism | 0.257 | System improvement | 100 | ||||||

| Imperfect system | 60 | ||||||||

| Unestablished system | 0 | ||||||||

| Targeted management of production safety | 0.128 | Clear goal | 100 | ||||||

| Unclear goal | 60 | ||||||||

| Failure to establish goals | 0 | ||||||||

| Contractor management system | 0.083 | System improvement | 100 | ||||||

| Imperfect system | 60 | ||||||||

| Unestablished system | 0 | ||||||||

| Safety training and education | 0.241 | Training plans | 0.087 | Present | 100 | ||||

| Not present | 0 | ||||||||

| Training records | 0.142 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Education and training hours | 0.296 | Achieved | 100 | ||||||

| Not achieved | 0 | ||||||||

| Assessment of the effectiveness of safety education and training | 0.473 | Outstanding | 100 | ||||||

| Pass | 60 | ||||||||

| Fail | 0 | ||||||||

| Inputs to production safety | 0.211 | Safety cost management system | 0.539 | Integrity | 100 | ||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Plan for the use of production safety costs | 0.297 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Extraction of production safety costs | 0.164 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Risk management and emergency response | 0.333 | Routine check-ups of hidden dangers | 0.889 | Safety risk and risk identification mechanism | 0.413 | System improvement | 100 | ||

| Imperfect system | 60 | ||||||||

| Unestablished system | 0 | ||||||||

| Frequency and coverage of safety inspections | 0.200 | Compliant | 100 | ||||||

| Non-compliant | 0 | ||||||||

| Identification and rectification of hidden dangers | 0.258 | Complete rectification | 100 | ||||||

| Partial rectification | 50 | ||||||||

| Not rectified | 0 | ||||||||

| Major accident risk situation | 0.129 | Non-existence | 100 | ||||||

| Critical risk: remediation ongoing | 50 | ||||||||

| Critical risk: unaddressed | 0 | ||||||||

| Emergency preparedness and response | 0.111 | Emergency planning | 0.389 | Integrity | 100 | ||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Emergency exercise plan | 0.160 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Emergency exercise implementation | 0.264 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Emergency supplies and equipment | 0.117 | Compliant with regulations | 100 | ||||||

| Non-compliance | 0 | ||||||||

| Emergency communications and information dissemination | 0.070 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Offline office space | 0.100 | Fire safety | 0.667 | Fire-fighting equipment and facilities | 1.000 | Completeness of the building’s fire protection system | 0.396 | Integrity | 100 |

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Configuration and integrity of the enterprise’s firefighting equipment | 0.239 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Fire escape accessibility | 0.194 | Smooth | 100 | ||||||

| Obstructed | 0 | ||||||||

| Availability of emergency supplies | 0.171 | Integrity | 100 | ||||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Electrical safety | 0.333 | Electrical equipment facilities | 0.750 | Maintenance of electrical equipment | 0.167 | Scheduled maintenance | 100 | ||

| Unscheduled maintenance | 0 | ||||||||

| Electrical wiring regulation and safety | 0.833 | Compliant with regulations | 100 | ||||||

| Non-compliance | 0 | ||||||||

| Electrical safety management system | 0.250 | Safety management system | 1.000 | Integrity | 100 | ||||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Production area | 0.4 | Base building and environment | 0.250 | Building layout risks | 0.557 | Production area | 0.750 | Compliant with regulations | 100 |

| Non-compliance | 0 | ||||||||

| Potential for expansion of the accident | 0.250 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Risk of meteorological conditions at the site | 0.320 | Extreme temperatures | 0.525 | Low sensitivity | 100 | ||||

| High sensitivity | 80 | ||||||||

| Humidity changes | 0.334 | Low sensitivity | 100 | ||||||

| High sensitivity | 80 | ||||||||

| Inundation | 0.142 | Not likely to happen | 100 | ||||||

| Likely to occur | 80 | ||||||||

| Geological risks at the site | 0.123 | Geological conditions | 0.889 | Not likely to happen | 100 | ||||

| Likely to occur | 80 | ||||||||

| Earthquake risk | 0.111 | Not likely to happen | 100 | ||||||

| Likely to occur | 80 | ||||||||

| Whole production process | 0.750 | Production equipment risks | 0.069 | Equipment structural integrity | 0.623 | Integrity | 100 | ||

| Incomplete | 0 | ||||||||

| Equipment life expectancy | 0.137 | Compliant with regulations | 100 | ||||||

| Non-compliance | 0 | ||||||||

| Maintenance of equipment | 0.239 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Production process risks | 0.257 | Potential for fire and explosion accidents | 0.381 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Potential for electrocution | 0.138 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Probability of fall-from-height accidents | 0.070 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Potential for poisoning accidents | 0.256 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Potential for object strike accidents | 0.046 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Possibility of mechanical accidents | 0.108 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Risks in the storage and transport of production materials | 0.170 | Type of material produced | 0.126 | Property stability | 100 | ||||

| Qualitative instability | 80 | ||||||||

| Reasonableness of mode of transport | 0.416 | Rational | 100 | ||||||

| Unreasonable | 0 | ||||||||

| Pipeline status | 0.458 | Compliant/not involved | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Maintenance of equipment and facilities | 0.059 | Maintenance of equipment and facilities | 1.000 | On schedule | 100 | ||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Fire protection system | 0.330 | Monitoring and early warning systems | 0.450 | Yes | 100 | ||||

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | 0.211 | Yes | 100 | ||||||

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| Configuration of other fire-fighting facilities | 0.074 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Operation and maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | 0.265 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Hazardous waste treatment | 0.116 | Solid, liquid, and gas waste treatment | 1.000 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||

| Inconformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Storage areas | 0.2 | Warehouse building design and environment | 0.096 | Building design | 1.000 | Reasonableness of mode of transport | 0.750 | Meets the requirements | 100 |

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Potential for expansion of the accident | 0.250 | Little possibility | 100 | ||||||

| High possibility | 80 | ||||||||

| Warehouse facility safety | 0.284 | Fire protection system | 0.750 | Monitoring and early warning systems | 0.462 | Yes | 100 | ||

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | 0.291 | Yes | 100 | ||||||

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| Configuration of other fire-fighting facilities | 0.071 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Operation and maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | 0.177 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Maintenance of facilities | 0.250 | Maintenance of facilities | 1.000 | On schedule | 100 | ||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Warehouse cargo safety | 0.619 | Storage safety | 0.500 | Material type | 0.151 | Stabilized | 100 | ||

| Instability | 0 | ||||||||

| Material storage method | 0.090 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Storage of flammable, explosive, and toxic hazardous chemicals | 0.311 | Meet the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Significant sources of danger | 0.448 | Not constituted | 100 | ||||||

| Constituted | 80 | ||||||||

| Transport safety | 0.500 | Inbound and outbound process standardization and safety | 0.889 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Cargo safety monitoring measures | 0.111 | System improvement | 100 | ||||||

| Imperfect system | 0 | ||||||||

| R&D center area | 0.2 | R&D center facility safety | 0.167 | R&D centerfire-fighting facilities | 0.833 | Monitoring and early warning systems | 0.421 | Yes | 100 |

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| Configuration of fire-fighting facilities | 0.219 | System improvement | 100 | ||||||

| Imperfect system | 0 | ||||||||

| Maintenance of fire-fighting facilities | 0.128 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Operation of the fire-fighting system | 0.232 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| R&D centerelectrical wiring and equipment | 0.167 | Safety of electrical equipment itself | 0.500 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Electrical wiring laying normality and safety | 0.500 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Whole process of experimental testing | 0.833 | Safety of laboratory equipment | 0.159 | Completeness of safety devices for experimental equipment | 0.731 | System improvement | 100 | ||

| Imperfect system | 0 | ||||||||

| Age of laboratory equipment | 0.119 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||||

| Non-conformity | 0 | ||||||||

| Maintenance of laboratory equipment | 0.149 | On schedule | 100 | ||||||

| Behind schedule | 0 | ||||||||

| Experimental process risks | 0.589 | Operating temperatures | 0.500 | −50 °c~100 °c | 100 | ||||

| 100~2000 °c; ≤−50 °c | 90 | ||||||||

| >2000 °c | 80 | ||||||||

| Operating pressure | 0.500 | ≤0.1 mpa | 100 | ||||||

| 0.1~10 mpa | 90 | ||||||||

| 10 mpa~100 mpa | 80 | ||||||||

| >100 mpa | 70 | ||||||||

| Hazardous waste treatment | 0.252 | Solid, liquid, and gas waste treatment | 1.000 | Meets the requirements | 100 | ||||

| Non-conformity | 0 |

References

- Peng, Z.; Lan, Y. Balance of Supply and Demand of Safety and Emergency Products and Services: Intelligent and Coordinated Development of Industry and Culture. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 37, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Li, L.; Li, N. Research on Fire Risk Assessment Methods for Chemical Industrial Parks. In Proceedings of the Academic Work Committee of the China Fire Protection Association on Fire Technology (2024)—Fire Risk Assessment Techniques; Shenyang Fire Research Institute of Emergency Management Department: Shenyang, China; Key Laboratory of Fire Prevention and Control Technology in Liaoning Province: Shenyang, China; National Engineering Research Center for Fire Protection and Emergency Rescue: Shenyang, China, 2024; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Guo, F.; Ge, Z.; Qiao, G. Hebei Keer Chemical “2-28” major explosion accident traceability. Labor Prot. 2012, 11, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Empty tank operation to change the real tank of high temperature curing detonation of combustion stairs blocked cargo elevator stops helplessly jumping casualties tragic—Wuhan City, Hubei Province, Topchoice Industrial Park “8.26” aerosol cans explode and burn the analysis of larger accidents. Jilin Labor Prot. 2020, 3, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. Chinese counterparts analyze South Korea’s “2-11” explosion accident. China Pet. Chem. Ind. Monit. 2022, 3, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F. Research on Accident Risk Analysis of Major Hazardous Sources and Emergency Rescue Systems in Chemical Parks; Central South University: Changsha, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B. Quantitative Research on Fire Safety Risk of a High-Tech Industrial Park Based on Bayesian Network; Shanghai University of Applied Sciences: Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kadri, F.; Châtelet, E.; Chen, G. Method for quantitative assessment of domino effect caused by overpressure. In Proceedings of the European Safety and Reliability Conference, Boulogne-Billancourt, France, 16–20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ikwan, F.; Sanders, D.; Hassan, M. Safety evaluation of leak in a storage tank using fault tree analysis and risk matrix analysis. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 73, 104597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wan, J.; Cai, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, F. Quantitative Evaluation of Lightning Safety Risk in Chemical Industry Zone Based on PSR Model. Guangdong Chem. 2023, 50, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Application of Regional Quantitative Safety Risk Assessment of Chemical Industry Park. Ind. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 44, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, L.; Bi, J. Research on the risk assessment system of environmental emergencies in industrial parks of Jiangsu Province. Environ. Pollut. Prev. 2020, 42, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y. Application of Quantitative Risk Assessment Software in the Safety Risk Assessment Process of Chemical Industrial Parks. Anhui Chem. Ind. 2024, 50, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Chen, S.; Su, M.; Wang, R.; Duo, Y. Study on index system construction and evaluation model of safety organization resilience in chemical industry parks. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 19 (Suppl. S2), 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Yang, J.; Luo, X.; Su, X. Evaluation method of safety resilience of chemical industry park based on fuzzy matter element. J. Saf. Environ. 2023, 23, 2624–2629. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, N. Research on safety risk assessment of chemical industrial park based on AHP-Fuzzy. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2023, 52, 226–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lu, Y. Research on comprehensive security risk assessment of small and medium-sized industrial parks based on hierarchical analysis-fuzzy comprehensive security assessment model. Ind. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 49, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.B. Application of Analytic Hierarchy Process-Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method in Safety Assessment of Chemical Industrial Parks. Contemp. Chem. Res. 2016, 12, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q. Application of safety check form method in safety evaluation and its improvement. Petrochem. Saf. Technol. 2003, 19, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, W.; Miao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Gao, J. Quantitative Evaluation Method and Practice of Emergency Response Capability for Accident and Disaster in High-rise Public Buildings. J. Saf. Environ. 2023, 23, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.; Liu, K. Consistency Check of Analytic Hierarchy Process is Not a Necessary Condition for Ranking. J. Hebei Univ. Archit. Technol. 2002, 19, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Research on the Application of AHP-Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method in Job Evaluation and Performance Assessment; North China Electric Power University: Baoding, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H. A risk evaluation model of submarine collective escaping capsules based on the expert weight and risk matrix. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2013, 8, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Duan, Y. Application of Risk Matrix in Classification of Dangerous and Hazardous Factors. China Saf. Sci. J. 2010, 20, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).