Abstract

The generation of atmospheric pressure nonequilibrium plasma using electrical discharges is an active area of research due to its significance in a wide spectrum of applications including medicine, combustion, and manufacturing. In our attempt to create a helium plasma jet in a pin-plane discharge with a constant current source, we observed self-pulsating behavior. We present the results of the electrical, optical, and spectroscopic measurements carried out to characterize the discharge. The duration of the discharge is a few tens of nanoseconds, and the repetition rate is in the few tens of kHz. The effect of the gap distance and gas flow is discussed. The effective capacitance formed by the space charge in the discharge region plays an important role in determining the pulsing frequency. The results of voltage swing, current pulse, and light emission are also discussed. Such self-pulsating discharges can be used to produce helium plasmas under ambient conditions in applications such as plasma medicine.

1. Introduction

The generation of atmospheric pressure nonequilibrium plasma using electrical discharges is an active area of research due to its significance in a wide spectrum of applications including medicine, combustion, and manufacturing [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In a gas discharge, the electrons gain energy from the source and the inelastic electron impact processes lead to growth in electron–ion densities, which is accompanied by an increase in the population of the excited species [8]. Most non-thermal plasma applications are based on enhanced gas-phase chemistry by the radicals produced by the discharge under ambient conditions. Therefore, the efficient production of the relevant excited species becomes important. The characteristics of electrical discharges depend on many factors, such as the electrode geometry, power sources (voltage, frequency, etc.), and the gas composition, pressure, and flow [9]. At low gas pressures, direct current (DC) glows and radio frequency (RF) are commonly used in semiconductor processing, such as sputtering, etching, and deposition [7]. At or near atmospheric pressure, generating glow like volume plasma becomes challenging due to instabilities leading to arc formation [1,2].

Over the past few decades, there have been many reports of non-thermal plasma generation near atmospheric pressure under ambient conditions. At atmospheric pressure, the dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) and repetitive nano-second pulsed discharges have found diverse applications, including the treatment of plastics and textiles, and in the environment and biotechnologies [6,7]. In a DBD, the charging of the dielectric quenches the micro-discharge before it turns into an arc. Similarly, for pulsed discharges, the pulse width is generally short enough to prevent the transition to an arc. A popular method is a pin-plane geometry, which is suitable for numerous applications such as plasma medicine [5]. These types of discharges can be driven with DC voltages or repetitive nano-second pulses. The pin electrode, due to its field enhancement at the tip, leads to an electrical breakdown at a lower applied voltage compared to plane–plane geometries. Needles are suitable for pin electrodes as they allow a convenient mechanism for controlled gas flow. The other successful method of generating DC glow discharges in atmospheric air is using micro-hollow cathodes. Stark and Schoenbach have shown that the micro-hollow cathode acts as a constant current source for the air glow [10]. The disadvantage of the micro-hollow cathode is the small plasma volume [10].

Most DC discharges investigated use a high voltage DC with a ballast resistor to limit the current [11,12,13,14,15,16]. These discharges, in most cases, reach a glow or arc-like discharge depending on the discharge parameters. Using the electrostatic model of the COMSOL Multiphysics software, Iqbal et al. computed the electric field for a pin-plane geometry similar to the system used in this study [11]. They found the electric field enhancement near the tip to be 10 times the average field and drops to 25 percent of the applied field near the plane electrode [11]. They investigated the formation of streamers under non-linear applied fields. Similar results were reported by Yamazawa and Yamashita for point-plane gap configurations using finite element methods [12].

Wu et al. investigated a pulsed air plasma device driven by a DC power supply with a large ballast resistance [13]. They observe a pulsing current waveform in the several-tens-of-kHz range. Xu et al. also reported on the characteristics of DC self-pulse touchable plasma jets in air and helium [14]. They also observe self-pulsing behavior in the kHz range similar to the results presented by Wu et al. [13]. However, these papers do not elaborate on the physics behind the discharge extinction. Wu et al. have reported the characteristics of a DC-high-voltage-driven needle-plane discharge with a ballast resistance in the range of 1–100 MΩ. They describe five different modes of discharge for different gap distances: steamer corona, single filament, transient glow, DC glow, and spark. For large ballast resistance, they mainly observe the streamer corona, single filament, and spark modes, whereas, for lower resistance values, they observe the DC glow discharge [15].

The current voltage (I–V) characteristics of DC electrical discharges have been studied primarily by varying the applied voltage in series with a ballast resistor. Depending on the pressure and gas composition, the DC discharge shows a distinct region, including normal and abnormal glows, negative differential resistance regions, and arc discharge [1,16]. In the glow phase, the current density is proportional to the square of the gas pressure, and, as the pressure increases, the current density increases, reaching the threshold for the glow to arc transition [2]. Our motivation for using a current source to drive the discharge was to control the current and maintain the current density below the instability threshold. We were interested in creating a non-thermal plasma using electrical discharge with a current source as opposed to the conventional method of voltage source with a ballast resistance. The rationale for investigating this type of power source was to set the current limit in the discharge with the constant current source and let the discharge voltage adjust accordingly. With a voltage source, a high ballast resistor essentially serves as a current source which limits the discharge current. However, this requires very high voltage and large ballast resistors. To our surprise, we found that the discharge was self-pulsating instead of a steady DC discharge. In this article, we report on the results of the electrical and optical characterization of the self-pulsating discharge driven by a constant current source. As we have noted above, self-pulsing has been observed in high-voltage DC discharges under certain conditions. Our investigation provides an additional explanation for the self-pulsing in DC discharges. This type of self-pulsating discharge could be used for many non-thermal-plasma-enabled technologies, such as plasma medicine, which depends on radical chemistry [5,17]. An advantage of the proposed configuration is that it would be a simple and compact source, as opposed to high-voltage nanosecond discharges, which tend to be expensive and bulky.

2. Experimental Setup

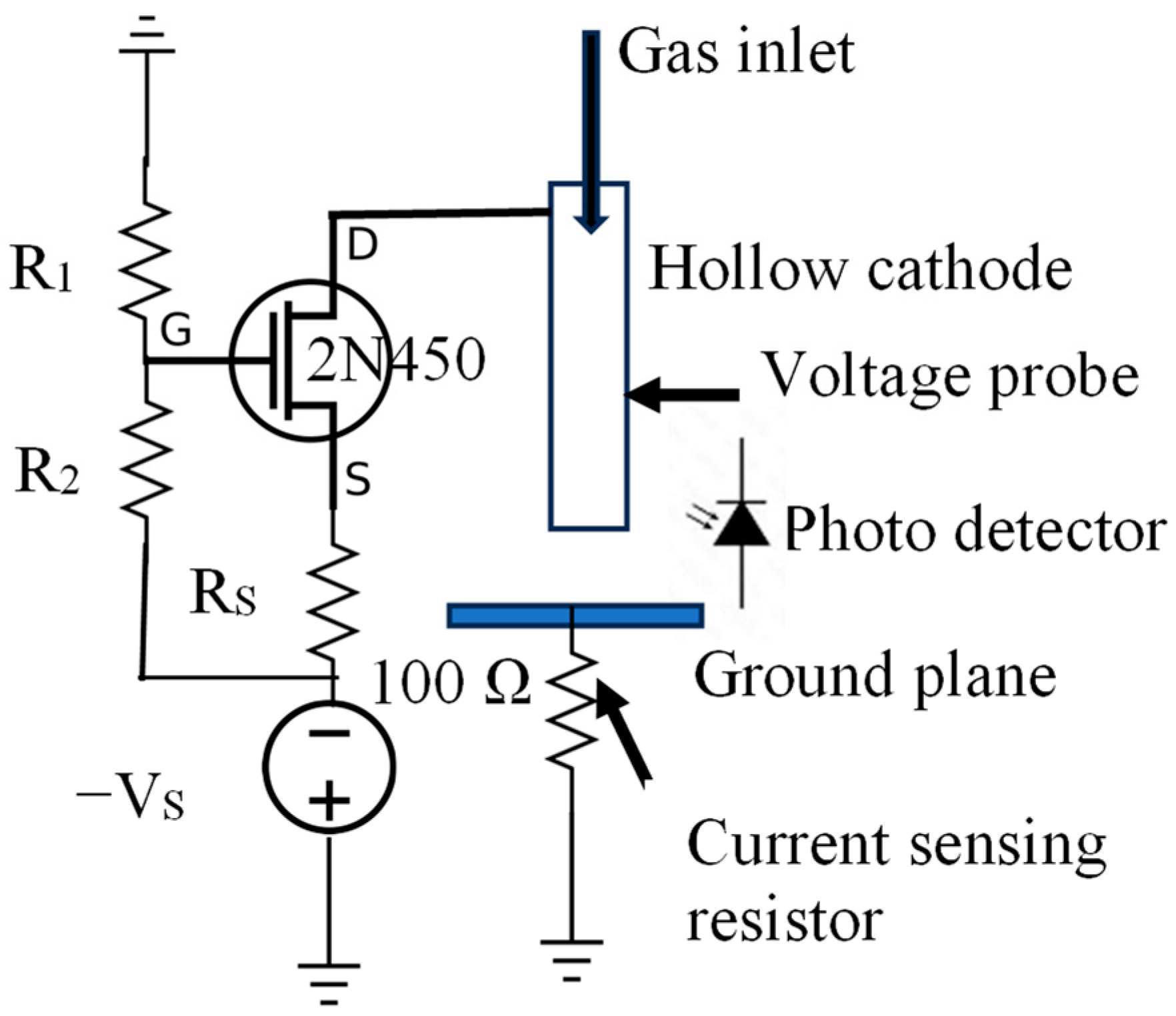

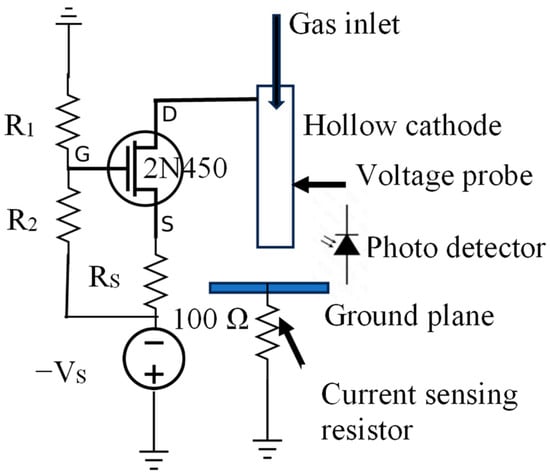

The experimental setup of the current-source-driven pin-plane discharge is shown in Figure 1. The pin electrode is a 22 regular wall (RW) needle, which is 5 cm in length, with an inner and outer diameter of 0.41 mm and 1.0 mm, respectively, and is mounted horizontally. The ground plane is a square copper plate of 10 cm side mounted on an optical translator, which allows us to obtain a gap distance resolution of 0.5 mm. The helium flow is controlled using a variable area flow meter with a resolution of 0.2 L/min. All waveforms are acquired using a TDS2014 (Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) 100 MHz oscilloscope. A P6015A (Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) high-voltage probe with an input capacitance of 3 pF is used for measuring the discharge voltage. The probe was connected to the drain terminal of the MOSFET (metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistor), and a 15 cm 16-gauge copper wire connects the MOS drain to the pin cathode. A Si photo detector DET36A2 (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA) is used for recording the intensity of the emission from the discharge. The detector has an area of 13 mm2, a spectral range of 350–1100 nm, and a rise time of 14 ns. The detector is connected to oscilloscope with a 50 Ω coaxial cable (0.5 m) terminated with a 50 Ω resistance. The current is calculated from the voltage drop across a 100 Ω resistance in series with the ground plane. The discharge emission spectrum is recorded using HE 2000+ (Ocean Insights, Orlando, FL, USA) spectrometer. The emitted light is collected by an optical fiber about 3 cm from the discharge and perpendicular to it.

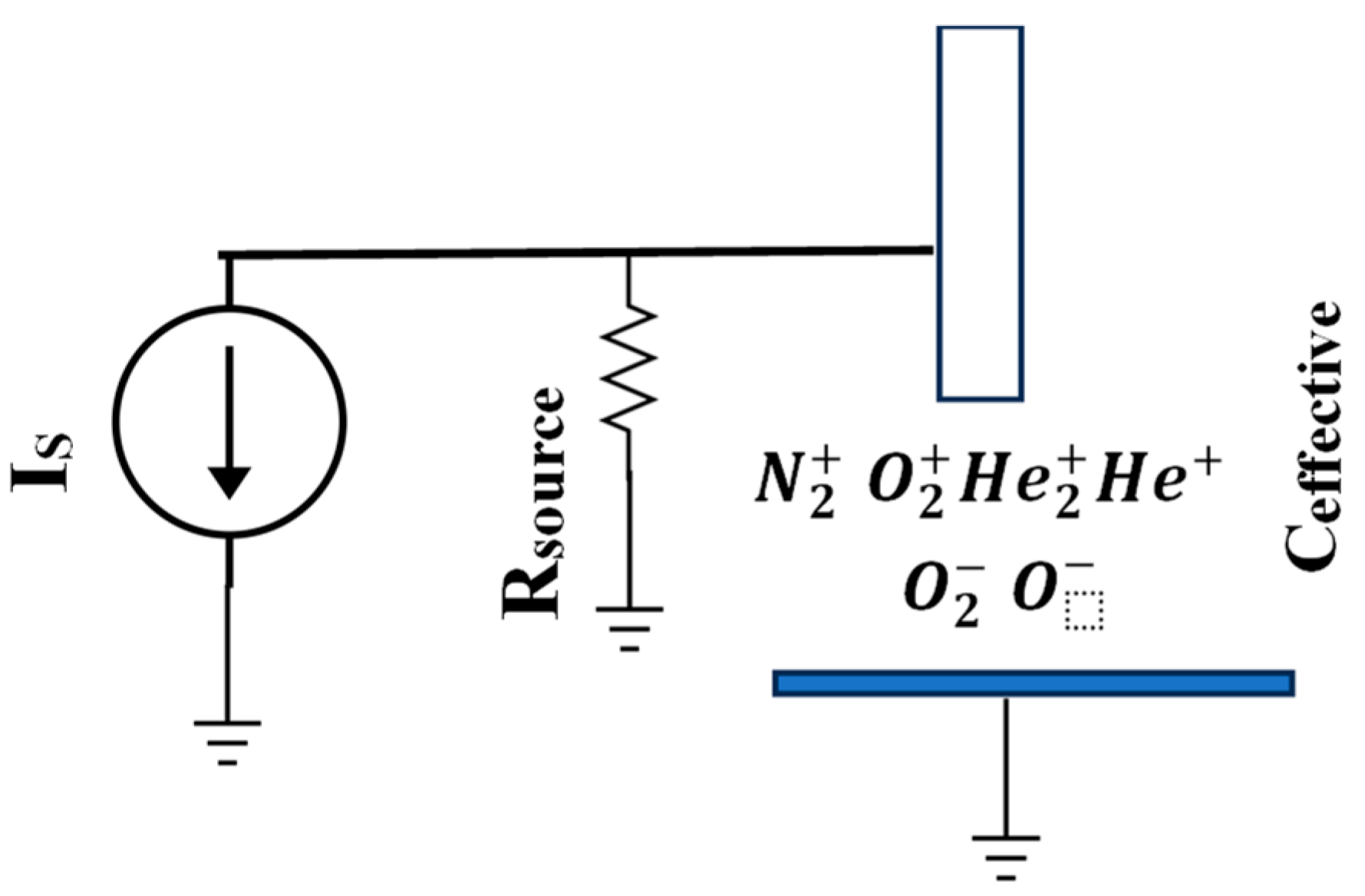

Figure 1.

Schematic of current-source-driven pin-plane discharge.

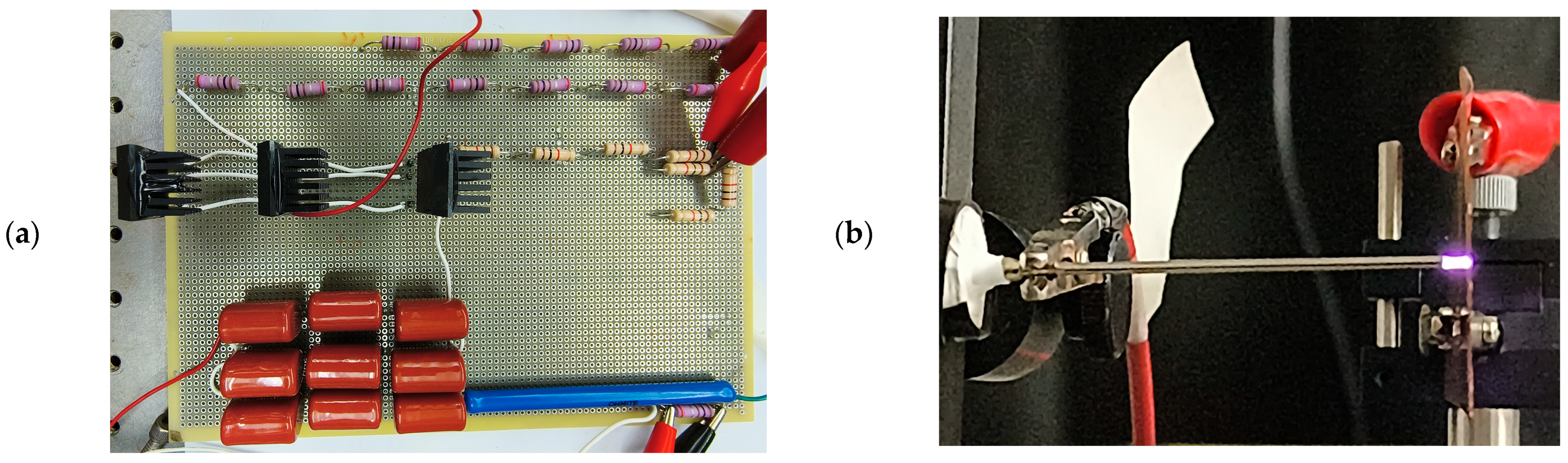

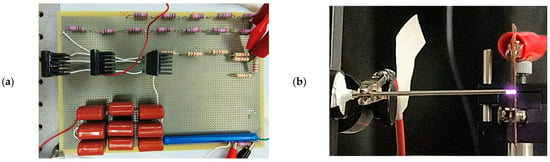

The circuit for generating a MOS current source is the commonly used architecture with a fixed value of gate-to-source voltage (VGS), and the drain terminal of the MOS produces a current which shows weak dependence on the drain voltage. The voltage and current limitation of current source is due to the availability of high-power and high voltage MOSFETs. The n-channel MOS are available commercially, which can operate at drain-to-source voltage (VDS) of 2 kV. Since the p-channel MOS transistors VDS are limited to below 1 kV, they are not suitable for initiating electrical breakdown near atmospheric pressure. Figure 1 shows the schematic of the current source implemented with nMOS transistors and a −2 kV DC power supply. Due to the limitation of commercial availability of electronic components, we are limited to negative voltages, and currents of few mA. The current source circuit was built using a printed circuit board to minimize stray inductance and capacitance. Figure 2 shows the physical circuit with three MOSFETs in parallel with heat sinks and the pin-plane electrode with the helium discharge on.

Figure 2.

(a) Image of the circuit board of the constant current source. The three MOSFETs are connected in parallel and mounted with heat sinks. (b) The pin-plane electrode system showing the helium discharge under ambient conditions.

The drain current (ID) for a given gate-to-source voltage (VGS) in a MOS operating in the saturation region is given by

where and are the device parameters of the nMOS transistor, 2N450. The values were obtained from the manufacturer’s data sheet as 0.44 A/V2 and 6 V, respectively [18]. A loop equation around the voltage drop across RS, R2, and VGS gives the second equation needed to determine the current ID:

Solving Equations (1) and (2) simultaneously, with values of R1 = 1 MΩ, R2 = 3.5 kΩ, and RS = 0.35 kΩ, and three transistors connected in parallel, gives a drain current ID = 3.5 mA. From the device characteristics provided in the data sheet, the drain-to-source incremental resistance of the device, ro, was determined to be 500 kΩ for the calculated drain current. Assuming the MOS operates in the saturation mode, the incremental output resistance (resistance looking into the drain terminal) of the current source is estimated to be 13 MΩ [19].

The capacitance of the pin-plane electrode geometry for air dielectric shown in Figure 1 is given by [13,14]

where is the free space permittivity, lp and rp the length and radius of the pin electrode, respectively, and d is the gap distance. For the discharge geometry used in this report, lp = 5 cm, rp = 0.5 mm, and d = 2 mm, and, from Equation (3), the calculated value of Cgap = 1.2 pF.

3. Results and Discussion

As a test case, the pin-plane discharge was first tested with a DC voltage of −2 kV in series with a ballast resistance of 250 kΩ. For a gap distance of 2 mm and helium flow of 3 L/min, we obtained a steady discharge with a gap voltage of −210 V and current of 7 mA. This circuit showed no self-pulsing, and no further characterization was performed, whereas, for the current source circuit configuration of Figure 1, the discharge was self-pulsing, and the rest of the results and discussion pertain to this configuration.

This section discusses the results of the electrical and optical measurements of the current-source-driven pin-plane electrode. This is followed by the modeling and simulation of the discharge to obtain a qualitative understanding of the charge distribution in the plasma. Finally, the emission spectroscopic results are presented to validate the plasma chemical processes.

3.1. Experimental Characterization

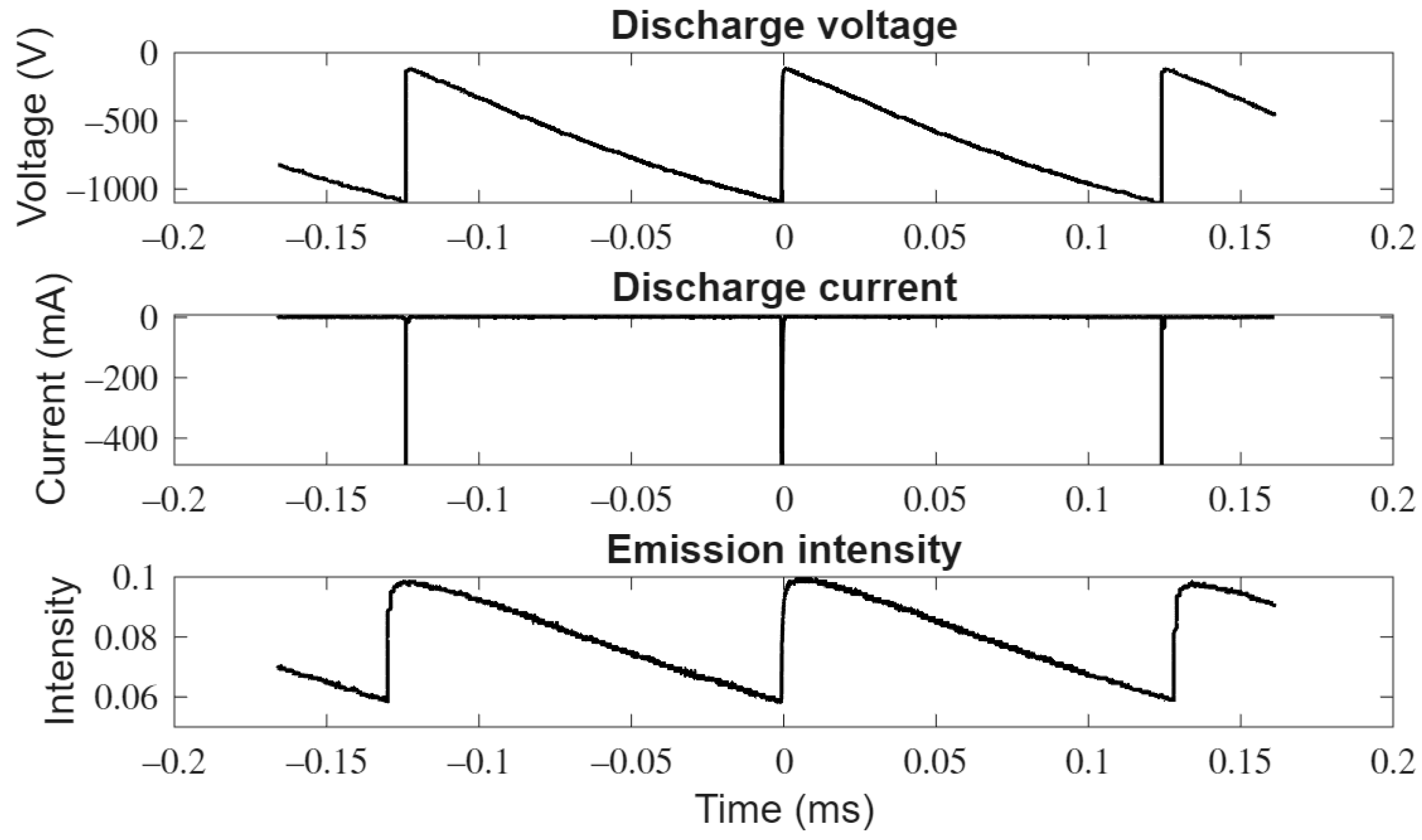

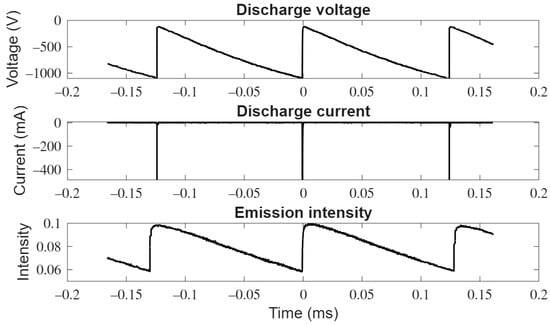

The electrical and optical characteristics of the discharge were measured for varying gap distances and helium flow. Figure 3 shows the steady-state oscilloscope traces of the discharge voltage, the current, and the emission intensity for a gap distance of 2 mm and a flow of 3 L/min. These traces are typical of all measurements for the varying gap distance and flow used in our experiments. The applied voltage to the needle electrode is negative and the plane electrode is at a ground potential. The electrical discharge self-pulsates at a 7.7 kHz repetition rate. There is a sharp drop in the magnitude of the discharge voltage when the breakdown occurs. This coincides with a narrow current pulse. The magnitude of the voltage under the conditions examined when the breakdown occurs is about 1 kV and the minimum magnitude is around 180 V. Since the emitted light persists at the end of the cycle, it indicates that there are excited species present in the gap at the start of the new cycle. The remnant charge and excited species in the discharge channel from the previous pulses will have an impact on the breakdown characteristics. As this device is self-pulsating, it is difficult to capture the first few cycles. It is very likely the first breakdown would occur at a voltage higher than the 1 kV at the steady state. Following the extinction of the discharge, the voltage almost rises linearly as a result of charging by the current source of the effective discharge capacitance. The emission intensity jumps abruptly when the discharge current is present and decreases linearly once the discharge current goes to zero, but the emitted light does not go to zero by the end of the cycle.

Figure 3.

Oscilloscope trace of discharge voltage at the cathode, the discharge current, and the emission intensity. The gap distance was 2 mm, and the helium flow was 3 L/min.

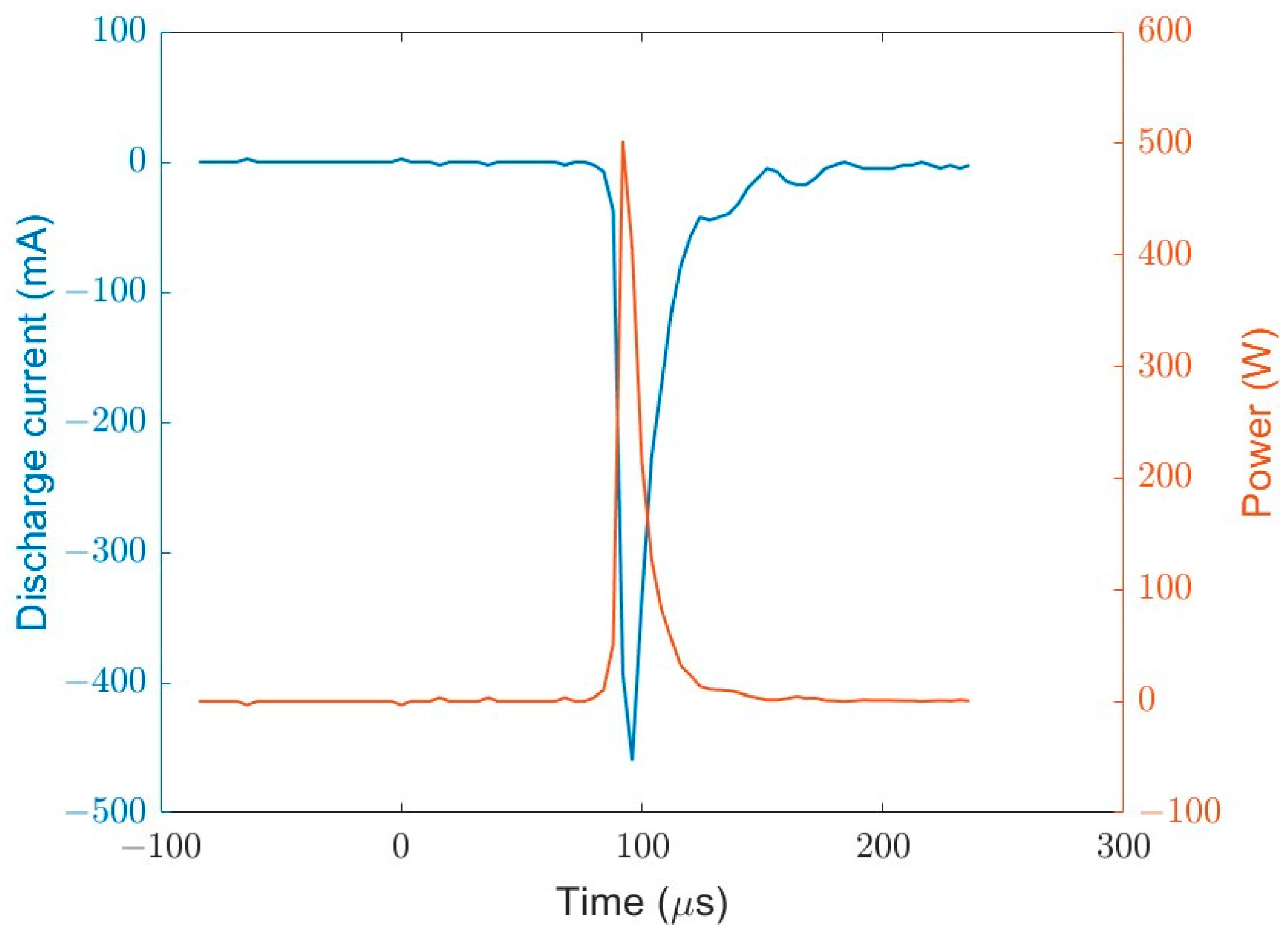

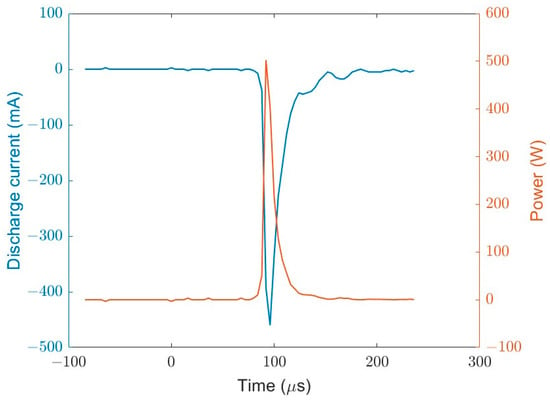

Figure 4 shows the expanded view of the current pulse and the instantaneous power which was obtained from the product of the discharge voltage and current. The full width at half max of the current pulse is about 60 ns which is similar to the plasma lifetime reported by Vidmar [20]. The shape of the instantaneous power is like the current as the voltage across the gap changes at a much slower rate compared to the current as shown in Figure 3. However, the full width at half max of power is slightly lower than the current as the discharge voltage drop coincides with the current pulse. The energy per pulse was obtained by integrating the power shown in Figure 4 over one cycle, and, for the conditions shown in Figure 3, it was 0.22 mJ per pulse.

Figure 4.

The steady state discharge current pulse and the instantaneous power. The gap distance was 2 mm, and the helium flow was 3 L/min.

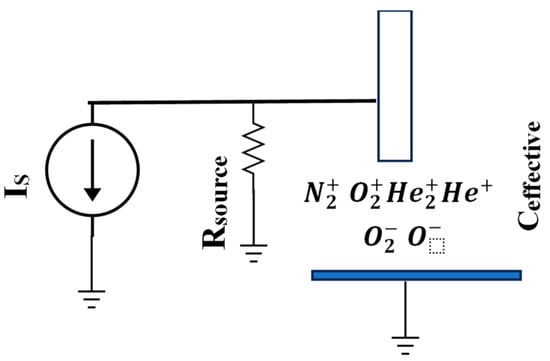

From the circuit equations shown earlier, the current source can be modeled as shown in Figure 5 with a constant current source (IS = 3.5 mA) and a source resistance (Rsource = 13 MΩ) in parallel. The effective capacitance due to the electrodes, wiring, the probe, and that arising from various physical phenomena such as space charge is shown in parallel to the current source. We can estimate this effective capacitance from the rate of change of the voltage due to charging by a constant current source given by the following equation:

Figure 5.

Lumped model of the current source and discharge. The positive and negative charged particles shown contribute to the effective capacitance of the discharge.

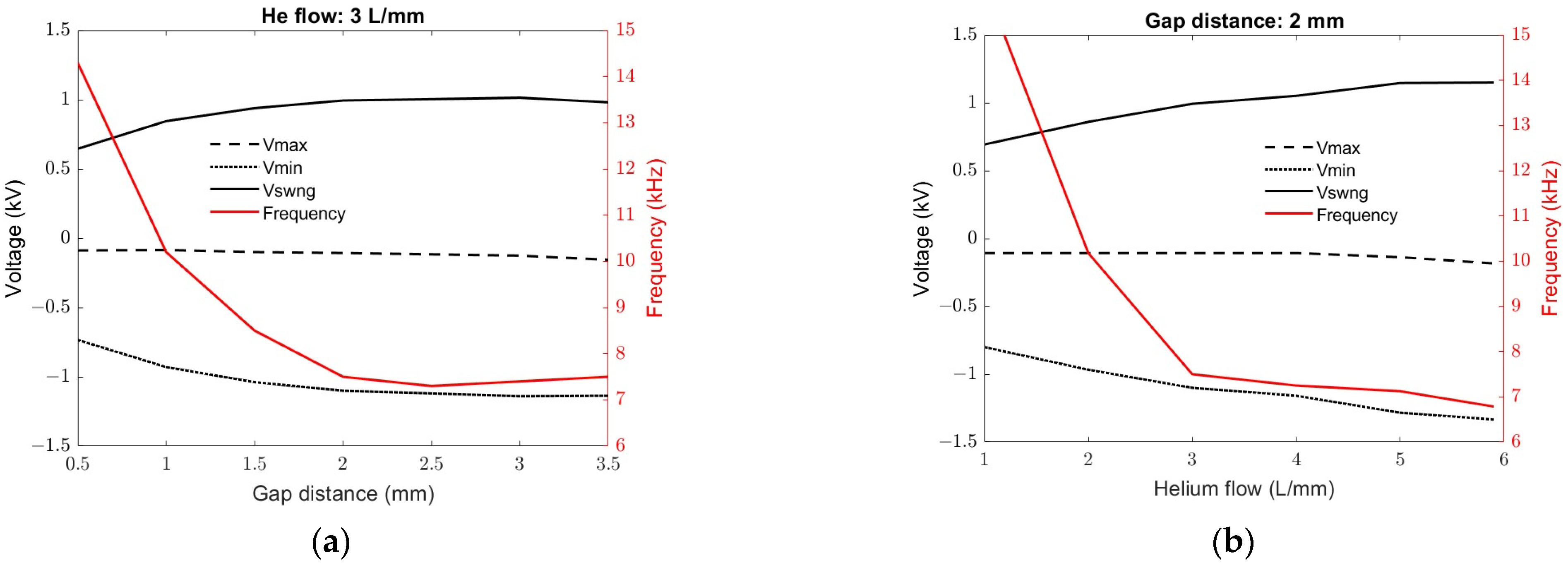

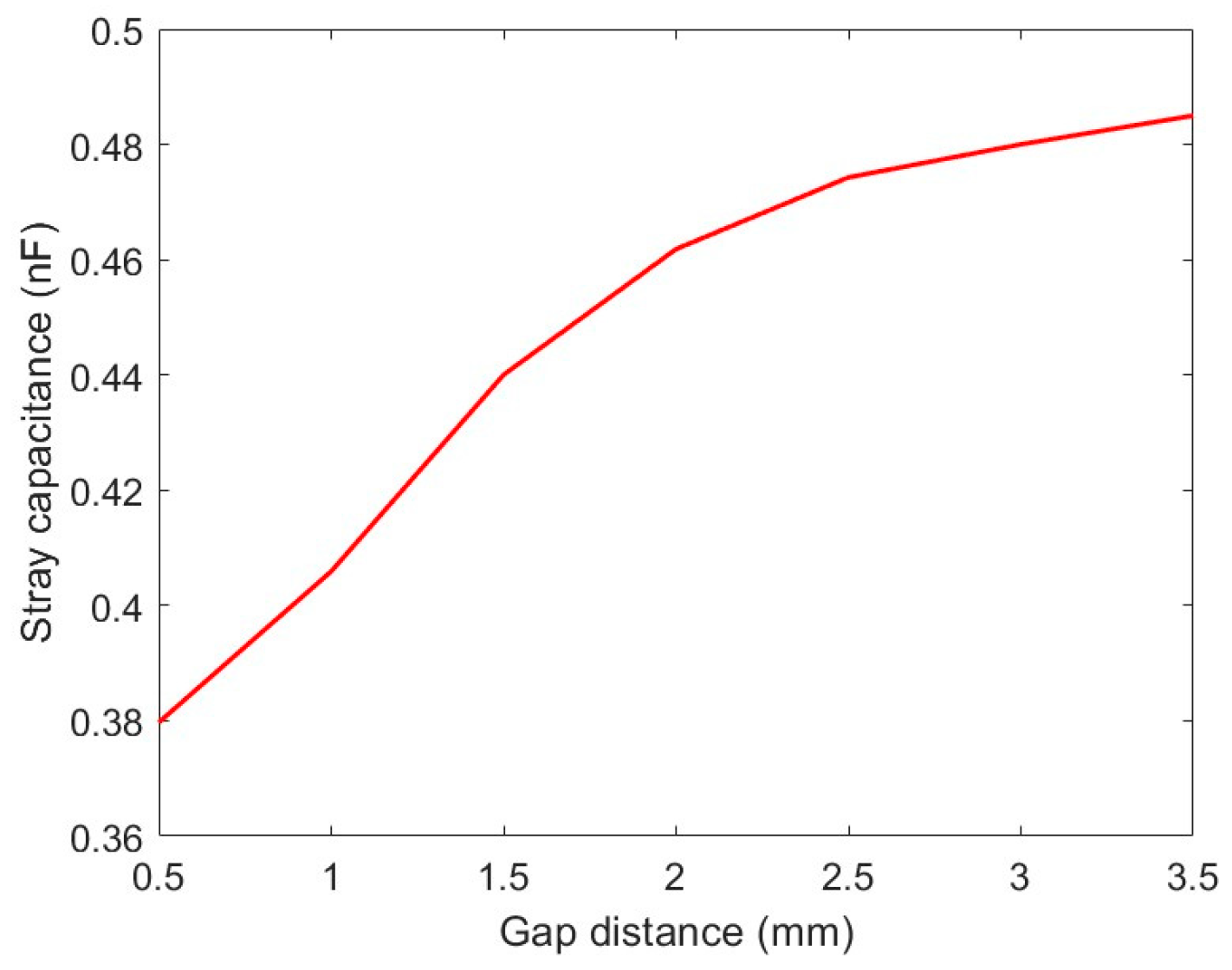

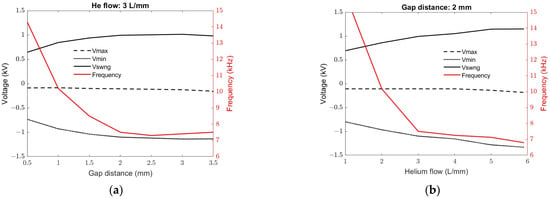

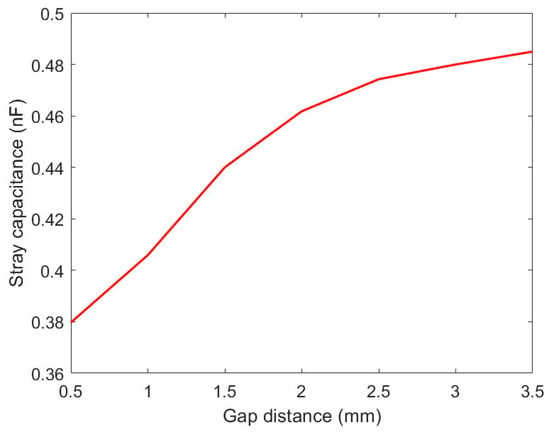

Figure 6a,b show the maximum, the minimum, and the swing of the discharge voltage along with the self-pulsing repetition frequency for a range of gap distances and helium flow, respectively. Xu et al. also reported a similar dependence of the frequency on the gap distance for the needle-plane discharge driven by a high-voltage DC power supply [14]. In our case, it can be attributed to the charging time to reach the voltage needed to initiate the breakdown, which increases as the gap distance increases, as shown in Figure 6a. The value of can be obtained from the data points shown in the figure. For example, a gap distance of 2 mm and flow rate of 3 L/min leads to = 7.4 MV/s. For a current source IS = 3.5 mA, we can estimate the stray capacitance, and Figure 7 shows the value as a function of the gap distance. These values are orders of magnitude higher than the capacitance calculated for pin-plane electrodes in air free of the charge using Equation (3), and the probe capacitance. The large value of the effective capacitance as compared to the air dielectric is due to the presence of the space charge as depicted in Figure 5. The space charge behaves like a polarized dielectric and effectively increases the capacitance. The presence of the space charge is discussed later in this section.

Figure 6.

(a) The maximum, minimum, and swing of the discharge voltage and the pulsing frequency for different gap distances. The He flow was 3 L/min. and the gap distance was varied in increments of 0.5 mm. (b) The maximum, minimum, and swing of the discharge voltage and the pulsing frequency for different He flow rate. The gap distance was 2 mm and the flow was varied in increments of 1 L/min.

Figure 7.

Stray capacitance as a function of gap distance calculated from the discharge voltage and frequency shown in Figure 6.

The energy stored in a capacitor C charged to a voltage V is given by . As the effective capacitor, Ceffective, discharges during the breakdown, the energy delivered to the discharge can be estimated from the Vmax and Vmin values shown in Figure 6. For the discharge condition of Figure 3, the energy delivered by the effective capacitance is 0.28 mJ. This is in good agreement with the energy per pulse of 0.22 mJ found experimentally.

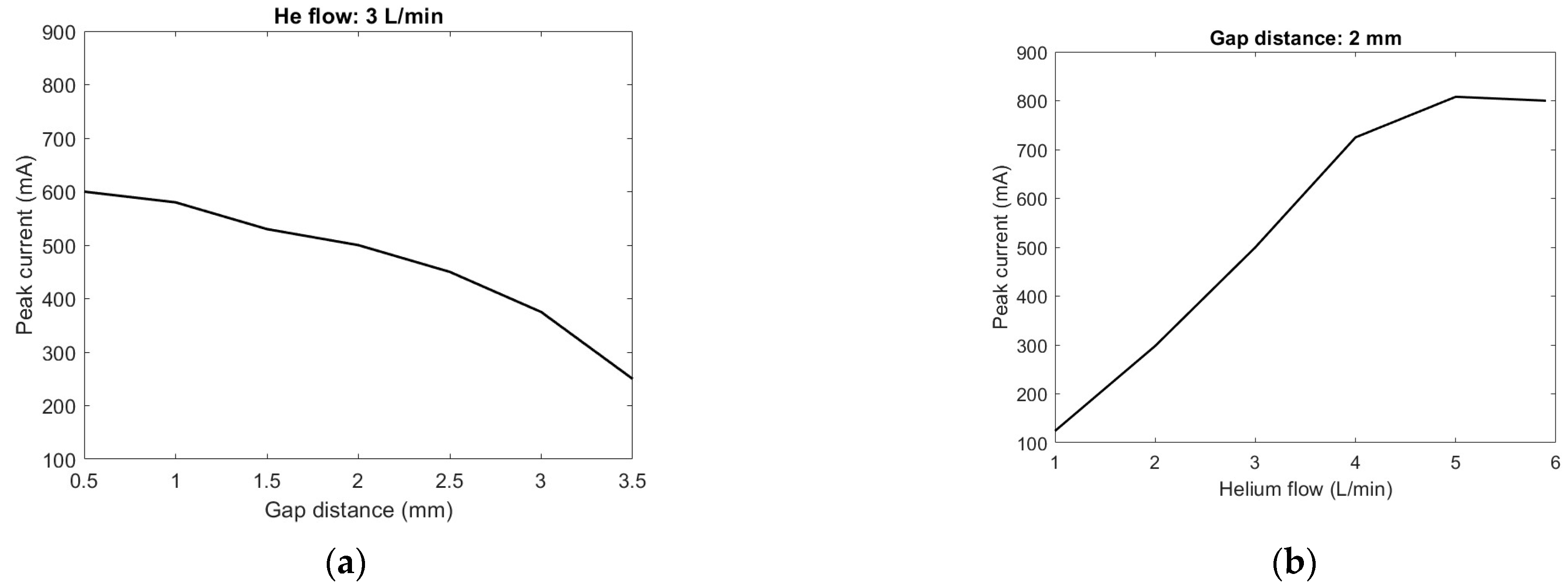

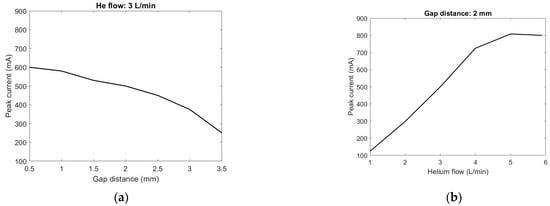

The peak current in the discharge phase varies depending on the discharge conditions. Figure 8 shows the peak discharge current for a varying gap distance and helium flow. With our experimental setup, the helium flow for proper operation is between 1 to 6 L/min, and the maximum gap distance is 3.5 mm, beyond which we do not see a breakdown in helium. The peak current decreases as the gap distance increases due to the decrease in the electric field caused by the increase in the gap distance. However, the gap distance change also impacts helium mixing with the ambient air. The helium exiting the needle impinges on the plane electrode, which causes the mixing of helium with the ambient air. With an increase in the proportion of air in helium, it would require a larger amount of energy to sustain the discharge due to the loss of electrons from the attachment to oxygen. For short gap distances, we would expect more turbulent mixing, which is similar to the increase in He flow for a fixed distance. The peak current, therefore, is the highest for short distances and high flow rates.

Figure 8.

Peak current magnitude as a function of gap distance and helium flow: (a) flow = 3 L/min; and (b) gap distance = 2 mm.

3.2. Modeling

There are several reports of the modeling of atmospheric pressure helium plasma jets exiting into ambient air [21,22,23]. Boeuf et al. have suggested the hydrodynamics of the helium jet is important for the propagation of the plasma jet [23]. Right at the needle exit, the composition is pure helium for radial positions less than the tube radius, and, further away from the exit, there is gradual gas mixing with air at the radial boundary. Our discharge setup is similar, and we can model the breakdown at the exit and along the axis as a pure helium discharge to obtain an approximate qualitative picture of the space charge distribution. However, near the plate, the composition is very well-mixed as the jet impinges on the electrode. The varying degrees of mixing due to the flow results in changes in the electrical characteristics shown in Figure 6b.

The discharge starts as an avalanche, and, as a critical density is reached, it turns into a streamer discharge. The avalanche phase is long compared to the streamer phase, as it starts from a low remnant charge, which must build up to densities of approximately 1013 cm−3, before the space charge dominates the local electric field. Once the streamer discharge bridges the gap, it forms a conducting channel, resulting in a large gap current. To obtain a qualitative understanding of the space charge distribution, numerical simulations of streamer propagation in pure helium at atmospheric pressure were performed. The first-order two-dimensional fluid model of the streamer consistently solves the continuity equations for electrons and positive ions, along with Poisson’s equation for the local electric field. The simulation bypasses the avalanche phase and assumes a dense neutral plasma at the tip of the pin electrode from which a streamer develops and propagates towards the plane electrode. A background remnant plasma of 106 cm−3 is assumed at the start of the simulations. Details of the fluid model and numerical method can be found in [4,9].

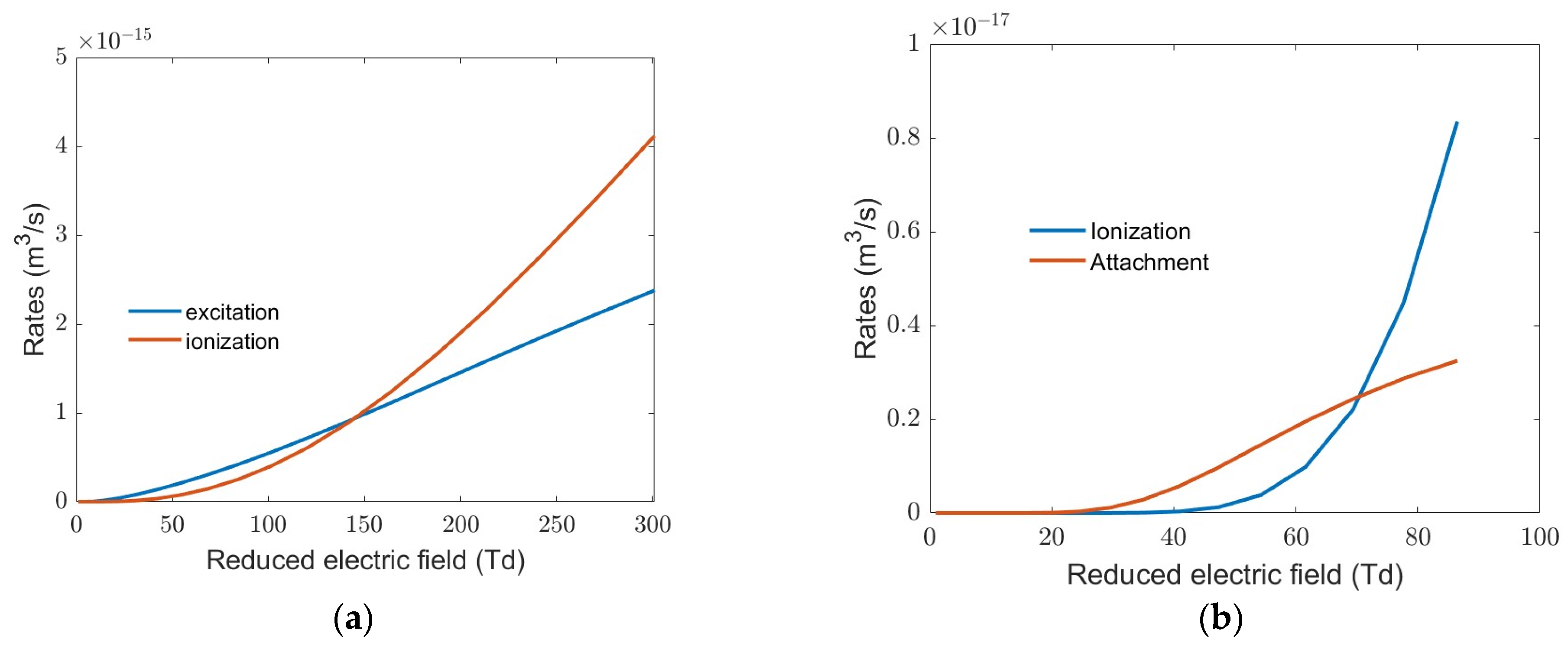

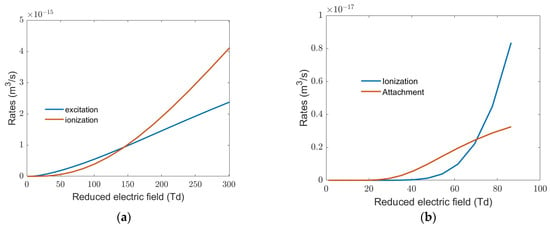

For a negative voltage applied to the pin, the streamer front propagates to the plane electrode, which is also the direction of the electron drift. The transport and rate coefficients for the streamer simulation are obtained from the solution of the Boltzmann equation using the BOLSIG+ [24,25]. Above 20 Td, the inelastic power loss is much higher than the elastic power loss. For pure helium, the two main inelastic rates which comprise excitation and ionization are shown in Figure 9a, and the rates are very similar up to 150 Td, which is the range of the reduced electric field we expect in our experiments. Therefore, we would expect a significant number of excited helium atoms in the discharge, which is evident from the emission spectra discussed later. When helium is mixed with air, electron attachment plays an important role in the development of the streamer. For the discharge presented here, the gas mixing is dependent on the spatial position and varies from pure helium to very diluted helium further from the needle [21,22,23,24]. To obtain a qualitative understanding of the importance of attachment, for example, for helium and air in equal proportion at low reduced electric fields, the attachment rate exceeds the ionization, as shown in Figure 9b. In a pin-plane geometry, the electric field is low near the plane electrode, and we would expect the attachment to exceed ionization in this region, with negative ions near the plane electrode. In the bulk of the plasma, the positive ions are generated by electron impact and Penning ionization by the helium metastable atoms. This double-layer space charge polarization is shown in the model for effective capacitance in Figure 5 [26].

Figure 9.

(a) Excitation and ionization rates in pure helium discharge. (b) Low field ionization and attachment rates for gas composition of He, N2, and O2 in ratio of 0.5, 0.4, and 0.1, respectively.

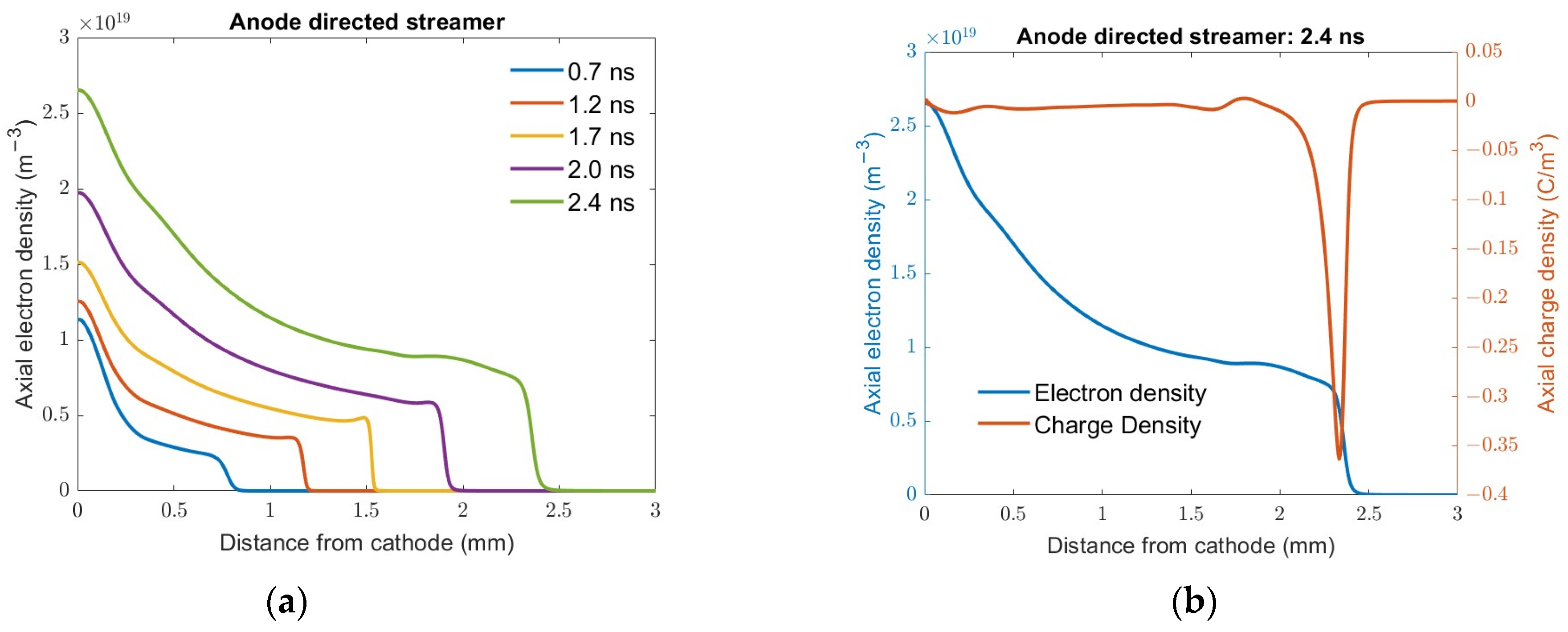

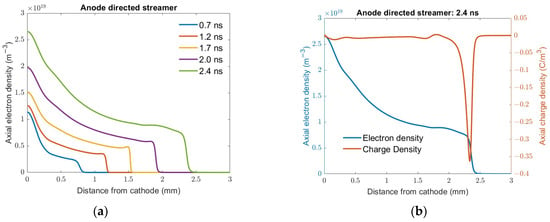

The streamer simulation was carried out for a 3 mm gap for an applied voltage of −2 kV. Figure 10a shows the evolution of the electron density as the ionization front propagates towards the plane anode. In the bulk of the plasma, the density is nearly equal to the electron density as the ionization produces both an electron and a positive helium ion. However, the streamer front shows the net charge due to the drift of the electrons in the field-enhanced region. Figure 10b shows the net charge density along with the electron density at 2.4 ns. The net charge density is the difference between the positive ion density and the electron density. The net charge density peaks at the streamer front, and it consists of electrons, since this is an anode-directed streamer. This space charge creates a high field enhancement at the streamer front, which is responsible for the propagation of the ionization front. Behind the streamer front, the plasma is nearly neutral, with some excess positive helium ions to maintain the charge conservation. The plasma densities reach values of the order of 1014/cm3. The streamer bridges the gap in a few nanoseconds once formed after the avalanche phase. Our model and simulations are only valid until the streamer reaches the anode. Once the gap is bridged, a conducting channel is formed and the current increases, and, subsequently, the voltage across the electrodes drops to the minimum value. At such low electric fields, the attachment exceeds ionization, and the discharge cannot be sustained.

Figure 10.

(a) The axial electron density at different times as the streamer propagates towards the plane electrode for atmospheric pressure helium and an applied voltage of −2 kV. (b) The net charge density at 2.4 ns.

As shown in Figure 9a, the electron impact rates to produce excited helium atoms are high and comparable to the ionization rate. The excited states relax to the metastable states. This is an efficient process, considering the threshold energy required to excite to the metastable states are 20.55 eV for the 21S0 and 19.77 for the 23S1 [27]. As the surrounding air diffuses into the helium channel, the He metastable atoms and electrons in the streamer react with the oxygen and nitrogen molecules. Vidmar looked at the plasma lifetime (1/e decrease) of the helium air mixture to sustain the plasma in air [20]. The plasma lifetime depends on the percentage of air present in helium. The electron loss is primarily due to the electron attachment to oxygen and the recombination. For electron densities less than 1012 cm−3, and high concentration of oxygen, three-body attachment to oxygen dominates the deionization process shown below [20,28]:

For lower concentration of oxygen, two-body dissociative attachment and the recombination process are the dominant loss process [27]:

For electron densities in the range of 1013 cm−3, Vidmar reports lifetimes of 60 ns in air to about 200 ns in helium with 100-ppm air [20]. These lifetime values support our measurements of the current pulse width of about 60 ns.

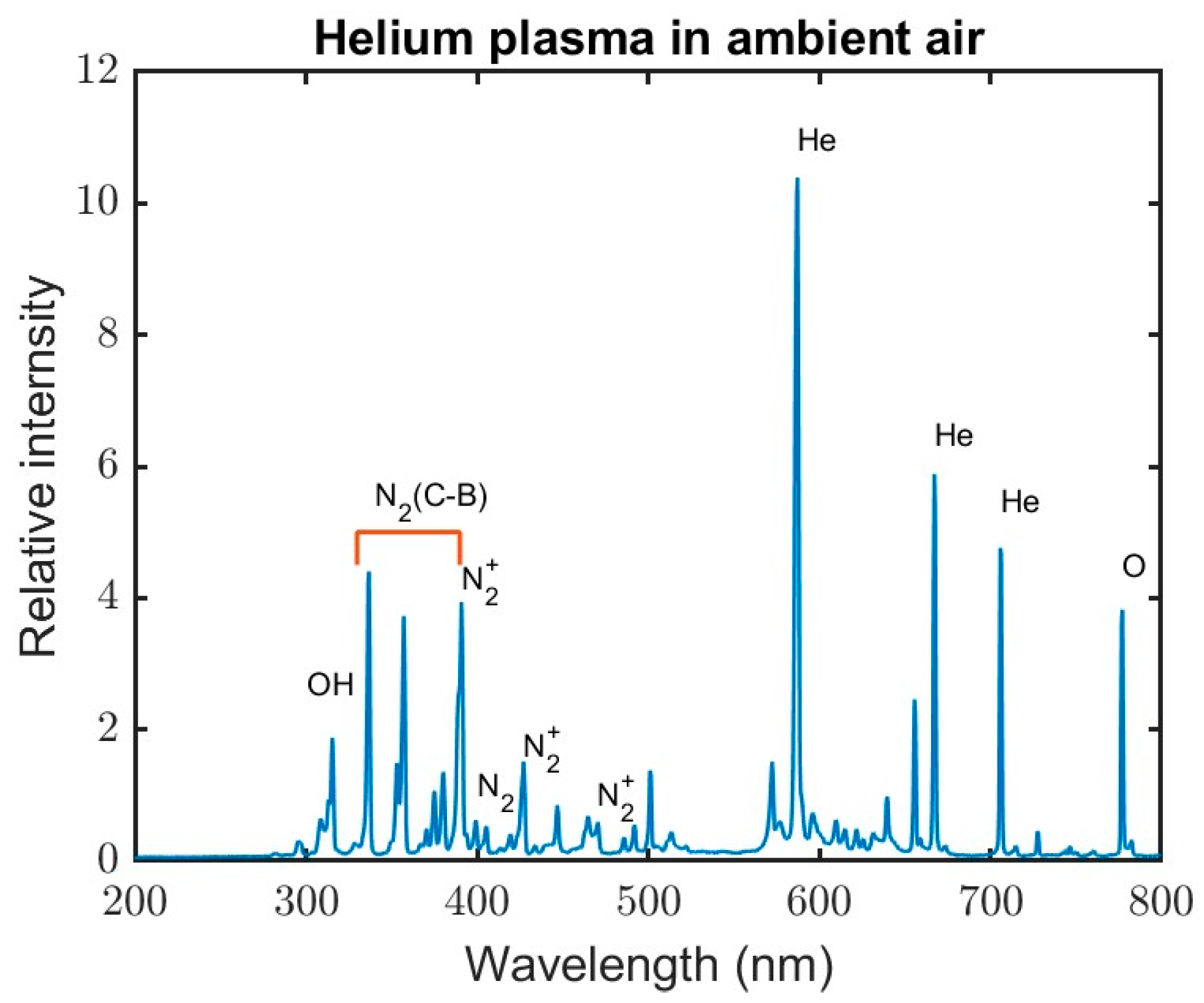

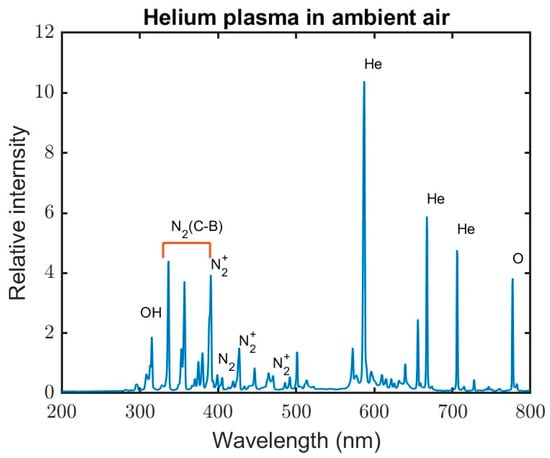

3.3. Emission Spectroscopy

Since the discharge size is, at most, 3.5 mm and the tip of the optical fiber is about 3 cm from the discharge, the light collected is the gross light emitted and is not spatially resolved. The integration time of the spectrometer being used is limited to a range of 1 ms to 65 s. Therefore, it was not possible for us to carry out any meaningful time-resolved spectroscopy. The data was acquired with an integration time of 1 s. The time-integrated optical emission spectra of a helium jet injected into air is shown in Figure 11. This is, in general, what is observed for all the experimental conditions investigated. When the discharge is “on”, the He electronic states are populated, and, as they relax to the metastable states with a lifetime in the order of a few hundred nano-seconds, the He emission lines dominate the spectrum [29,30]. This duration corresponds to the abrupt jump in the light intensity shown in Figure 3. The triplet He(I) 587.6 nm, He(I) 706.5 nm, and the singlet He(I) 667.8 nm are the major spectral lines [29,30]. Once the discharge current turns off, there is no further electron impact excitation of the helium atoms. During the current off period (afterglow), the helium metastable atoms interact with the ambient air and ionize, dissociate, and excite the N2, O2, and H2O molecules. As shown in Figure 3, the emission of light in the afterglow is due to these excited species. The 777 nm spectral line is produced by the transition of an oxygen atom from an excited state to a lower energy state, specifically the 3p5P to 3s5S transition [31]. The (0,0) band (391.4 nm) and the (0,1) band (427.8 nm) in the first negative band system ( in the spectrum is from the following reactions [17]:

Figure 11.

The time-integrated spectra of the emission from the plasma. The gap distance was 2 mm and the helium flow rate was 3 L/min.

Our proposed mechanism above is based indirectly on the wave shape of the total emission as recorded by the photodiode. However, measurements with optical bandpass filters could provide further conclusive evidence of the time evolution of specific transitions in the emission spectra. Such measurements would be useful for a particular application where the time dependence of plasma chemical reactions is important.

An important species for biological application is the OH radical. The pathway for the formation of the OH radical is via the oxygen atoms produced through the Penning ionization by helium metastable atoms [31,32,33,34]. The OH emission is at 305–332 nm, which is shown in Figure 11:

Towards the end of the cycle after hundreds of microseconds, the negative ions of oxygen lose electrons by the associative–detachment reactions shown below and return to the neutral state [35]:

These emission spectra are similar to what has been reported in helium plasma jets produced by nanosecond repetitive pulses for biological applications. Therefore, this simple current-source-generated pulsed plasma could find applications in plasma medicine [3,36].

4. Conclusions

When a pin-plane electrode system in helium is driven by a MOSFET constant-current source, we observe a self-pulsating discharge. The current pulse lasts for about 60 nanoseconds. The pulsing frequency is in the low tens of kHz and is determined by the charging time of the effective discharge capacitance by the current source. The effective capacitance is primarily due to the space charge created by ionization and electron attachment, and the double layer formed behaves like polarized dielectric media and is orders of magnitude higher than the physical capacitance of the pin-plane electrodes in air. The calculated values of the energy transferred from the effective capacitance to the discharge agrees with the measured energy per pulse. The emission from the discharge persists even after the extinction of the discharge due to the excitation of air molecules by metastable helium atoms. Spectroscopic measurements show strong He lines and the emission from ionized and excited nitrogen and oxygen molecules by the metastable helium atoms.

Such a plasma source could find applications in plasma medicine where helium is used as a carrier gas. The limitation of the current source makes it difficult to investigate other interesting parameters such as voltage polarity, larger currents, and other gases, which could validate some of the conclusions that have been drawn.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.D.; methodology, M.P., S.H. and S.K.D.; Software, S.K.D.; Validation, M.P., S.H. and D.W.; Formal analysis, M.P. and S.K.D.; Resources, S.K.D.; Data curation, M.P., S.H. and D.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.K.D.; Writing—review and editing, S.K.D.; Supervision, S.K.D.; Project administration, S.K.D.; Funding acquisition, S.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the US Office of Naval Research (Grant Number: W911NF-23-1-0173) and the National Science Foundation (Award Number: 2337461).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kunhardt, E.E. Generation of large-volume, atmospheric-pressure, nonequilibrium plasma. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2000, 28, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunhardt, E.E. Electrical Breakdown of gases: The prebreakdown stage. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 1980, 8, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltmann, K.D.; von Woedtke, T. Plasma medicine—Current state of research and medical application. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2017, 59, 014031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, S.; Dhali, S.K. Streamer Discharge Modeling for Plasma-Assisted Combustion. Plasma 2025, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M. Low-Temperature Plasmas for Medicine? IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2009, 37, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Dielectric-Barrier Discharges: Their History, Discharge Physics and Industrial Applications. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2003, 23, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltmann, K.D.; Kolb, J.F.; Holub, M.; Uhrlandt, D.; Simek, M.; Ostrikov, K.; Hamaguchi, S.; Cvelbar, U.; Cernak, M.; Locke, B.; et al. Future trends in plasma science and technology. Plasma Process Polym. 2018, 16, 1890001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhali, S.K. Generation of excited species in a streamer discharge. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 015247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhali, S.K.; Reyes, S. The Effect of Electrode Geometry on Excited Species Production in Atmospheric Pressure Air–Hydrogen Streamer Discharge. Plasma 2025, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, R.H.; Schoenbach, K.H. Direct current glow discharges in atmospheric air. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 74, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Wozniak, D.; Rahman, M.Z.; Banerjee, A.; Verboncoeur, J.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, C. Influence of discharge polarity on streamer breakdown criterion of ambient air in a non-uniform electric field. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2023, 56, 035204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazawa, K.; Yamashita, H. Calculation of the electric field distribution under the point-plane gap configurations using the FEM. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1997 Annual Report Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–22 October 1997; Volume 2, pp. 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Pan, Y. A touchable pulsed air plasma plume driven by DC power supply. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Nie, L.; Lu, X. Discharge characteristics of DC self-pulse touchable plasma jets. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 1st China International Youth Conference on Electrical Engineering (CIYCEE), Wuhan, China, 1–4 November 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cheng, W.; Huang, G.; Wu FLiu, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X. Positive streamer corona, single filament, transient glow, dc glow, spark, and their transitions in atmospheric air. Phys. Plasma 2018, 25, 123507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn-Jones, F. The Development of Theories of the Electrical Breakdown of Gases. In Electrical Breakdown and Discharges in Gases; NATO Advanced Science Institutes Series; Kunhardt, E.E., Luessen, L.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; Volume 89a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Reuter, S.; Laroussi, M.; Liu, D. Nonequilibrium Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jets: Fundamentals, Diagnostics, and Medical Applications; CRC Press, Taylor and Fransis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2N450. Available online: https://www.digikey.com/en/products/detail/ixys/IXTF02N450/3737625 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Razavi, B. Design of Analog Integrated Circuits, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vidmar, R.J. On the use of atmospheric pressure plasm as electromagnetic reflectors and absorbers. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 1990, 18, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, Y.; Graves, D.B. Neutral gas flow and ring-shaped emission profile in non-thermal RF-excited plasma needle discharge at atmospheric pressure. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2009, 18, 025022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, Y.; Graves, D.B.; Jarrige, J.; Laroussi, M. Finite element analysis of ring-shaped emission profile in plasma bullet. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 041501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeuf, J.-P.; Yang, L.L.; Pitchford, L.C. Dynamics of a guided streamer (‘plasma bullet’) in helium jet in air at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. I 2013, 46, 015201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelaar, G.J.M.; Pitchford, L.C. Solving the Boltzmann equation to obtain electron transport coefficients for fluid models. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2005, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps Database. Available online: www.lxcat.net (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Stren, F.; Weaver, C. Dispersion of dielectric permittivity due to space-charge polarization. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1970, 3, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, K.; Waskonig, J.; Sadeghi, N.; Gans, T.; O’Connel, D. The role of helium metastable states in radio-frequency driven helium-oxygen atmospheric pressure plasma jets: Measurements and numerical simulation. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 055005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T.; Tagashira, H.; Okada, I.; Sakai, Y. Three-body attachment in oxygen. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1978, 11, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobilliong, J.; Suyanto, H.; Marpaung, A.M.; Kurniawan, K.H. Spectral and Dynamic Characteristics of Helium Plasma Emission and its Effect on a Laser-Ablated Target Emission in a Double-Pulse Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) Experiment. Appl. Spectrosc. 2015, 69, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassen, W.; Notermans, R.P.M.J.W.; Rengelink, R.J.; van der Beck, R.F.H.J. Ultracold metastable helium: Ramsey fringes and atom interferometry. In Exploring the World with the Laser; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Stambulchik, E.; Kroupp, E.; Maron, Y.; Malka, V. On the Stark effect of the O I 777-nm triplet in plasma and laser fields. Atoms 2020, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, A.V. Absorption studies of helium metastable atoms and molecules. Phys. Rev. 1955, 99, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Hatano, Y. Measurements of the rate constants of the Penning ionization of nitrogen by helium metastable states as studied by pulse radiolysis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1976, 40, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.L.; Dalgarno, A.; Kingston, A.E. Penning ionization by metastable helium atoms. J. Phys. 1967, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Albritton, D.L.; Burt, J.A.; Schiff, H.I. Associative-detachment of O- and O2− by O2(1Δg). Can. J. Chem. 1969, 47, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mericam-Bourdet, N.; Laroussi, M.; Begum, A.; Karakas, E. Experimental investigations of plasma bullets. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 055207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.