Effect of Dielectric Thickness on Filamentary Mode Nanosecond-Pulse Dielectric Barrier Discharge at Low Pressure

Abstract

1. Introduction

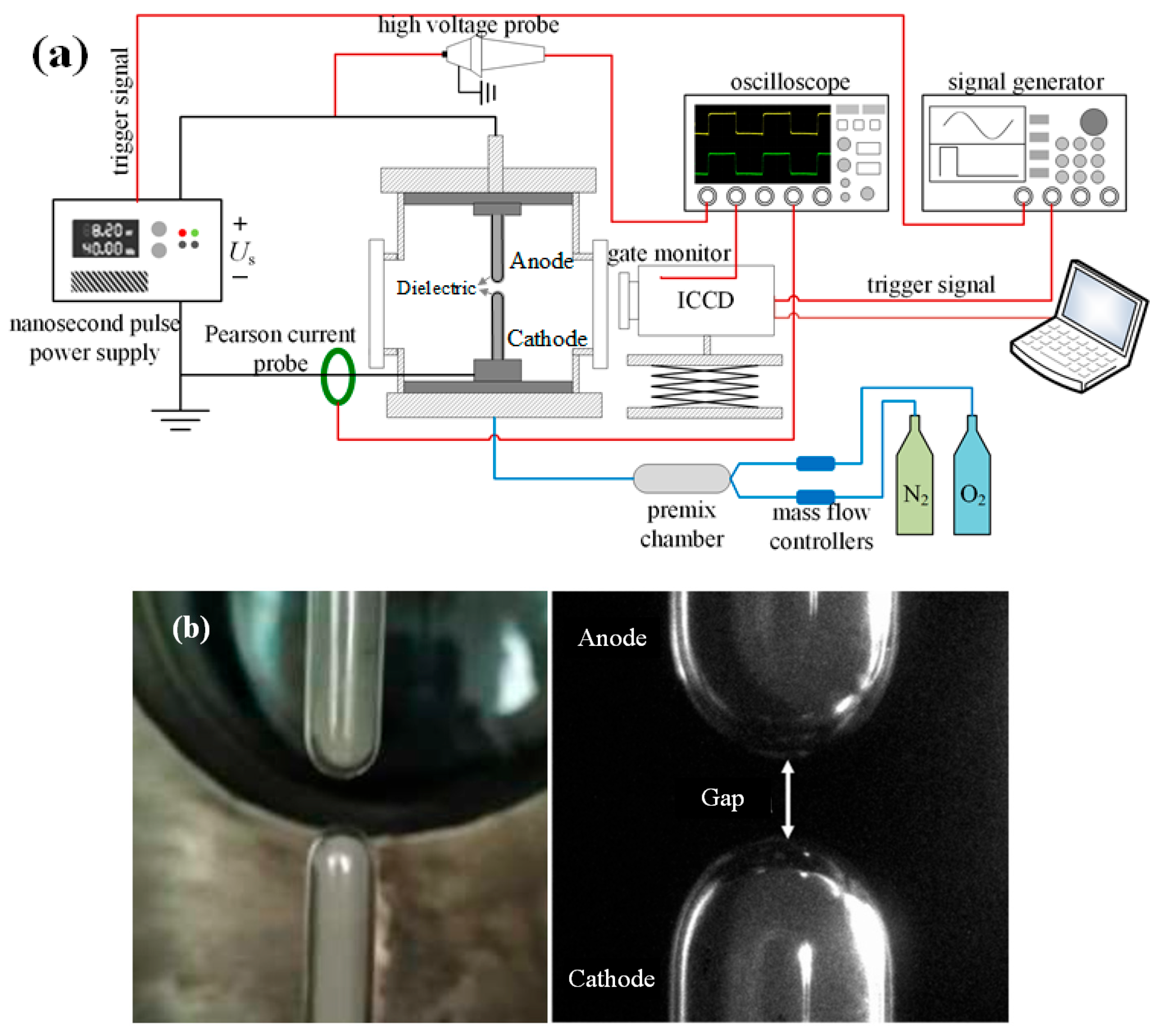

2. Experimental Setup and Simulation Model

3. Results and Discussion

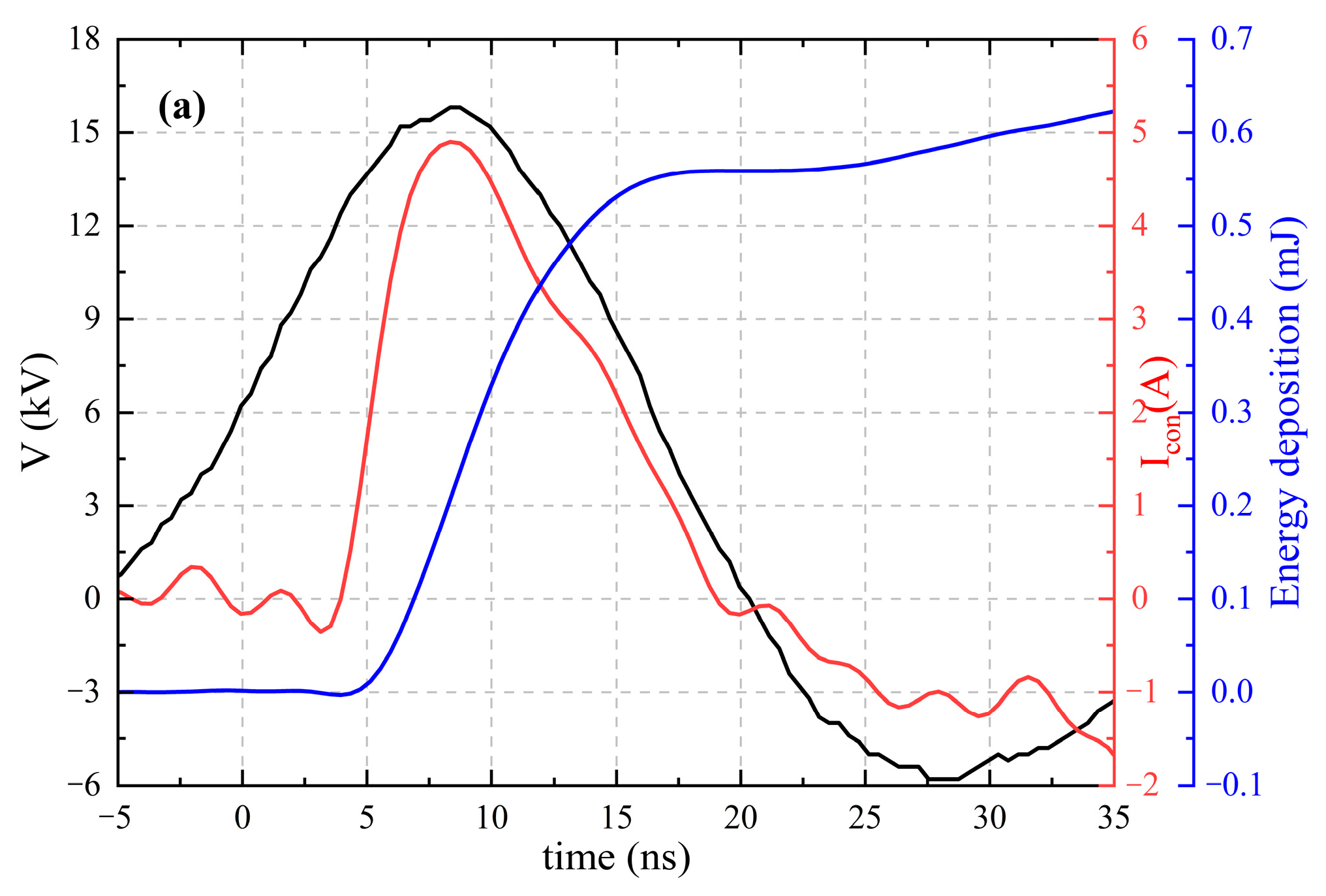

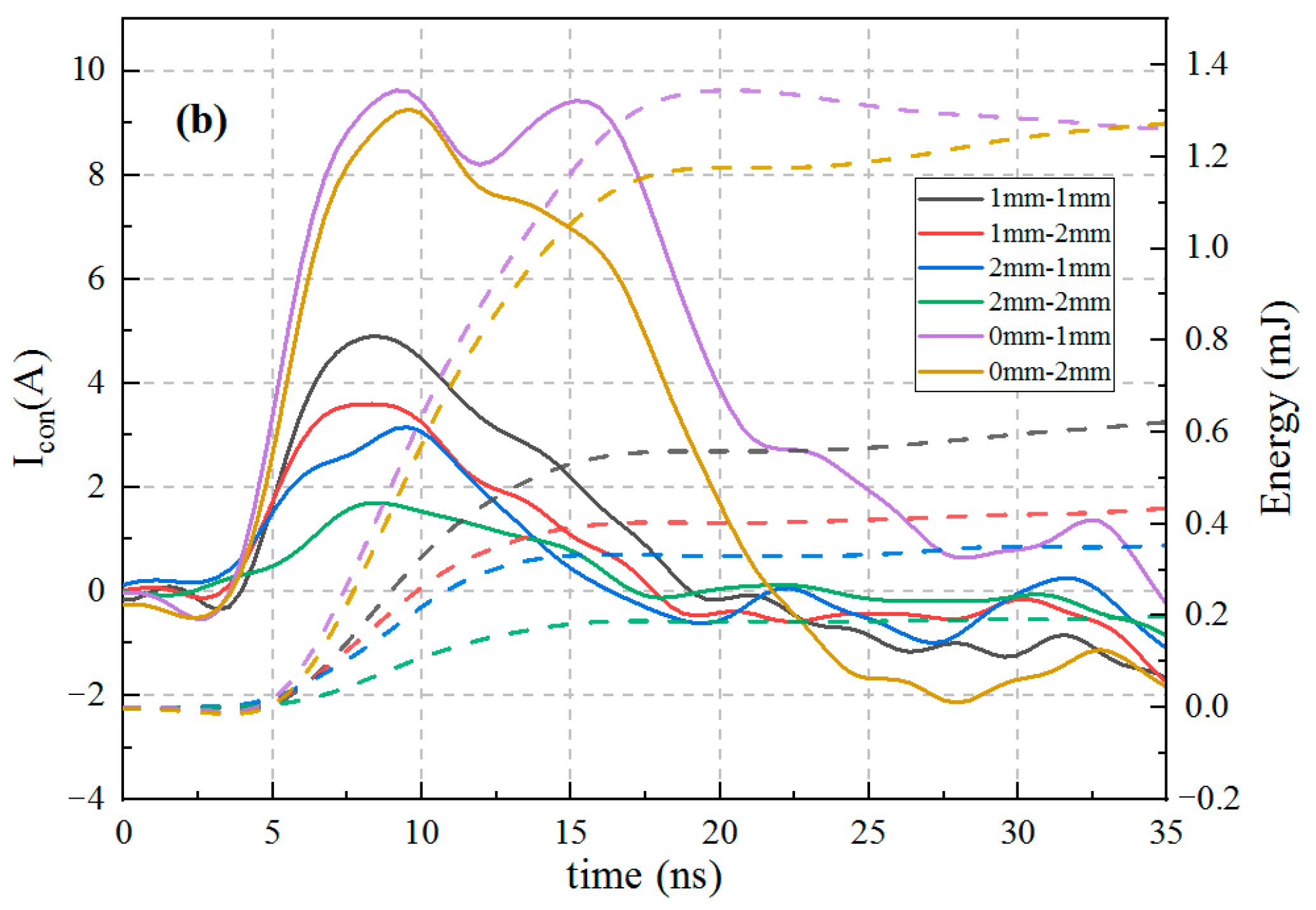

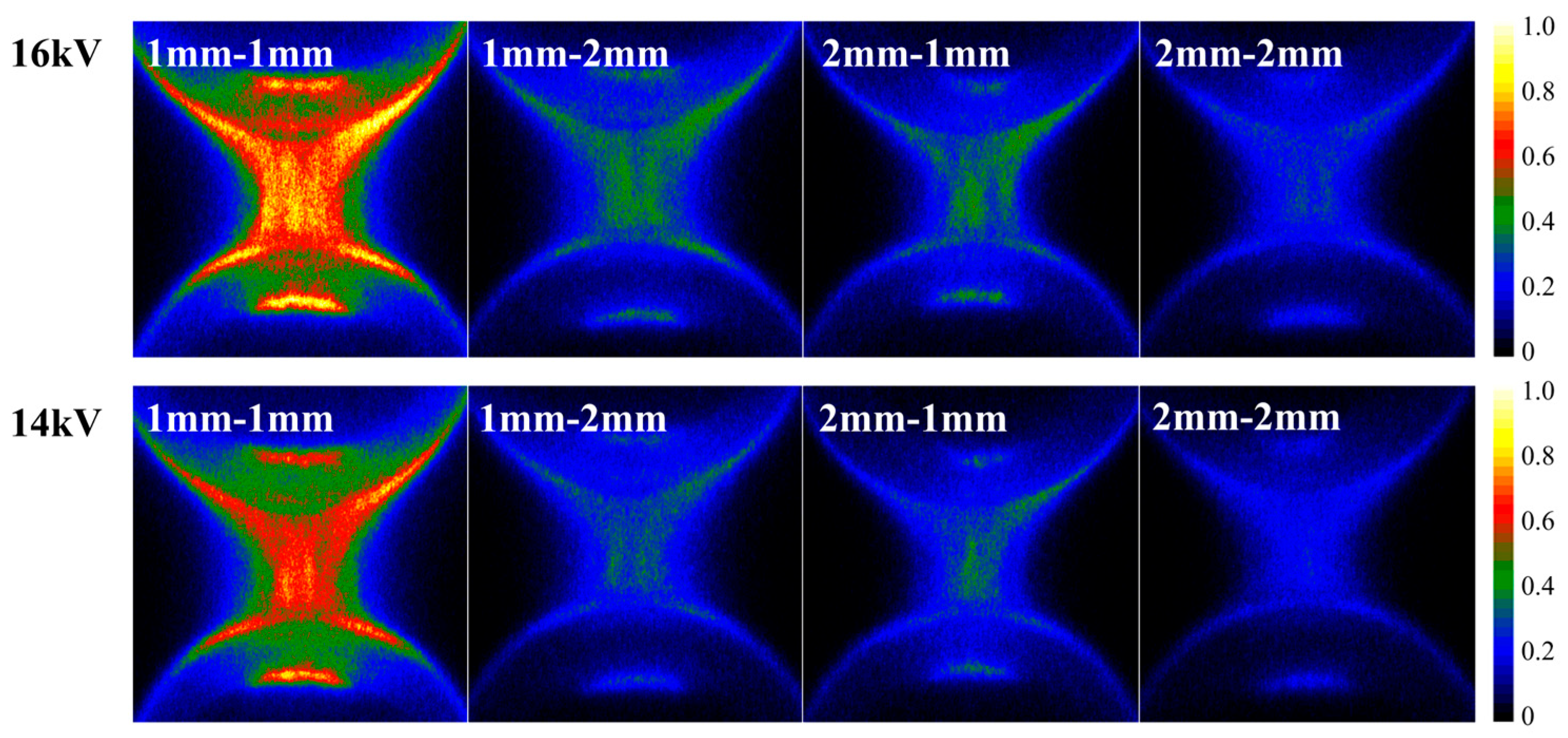

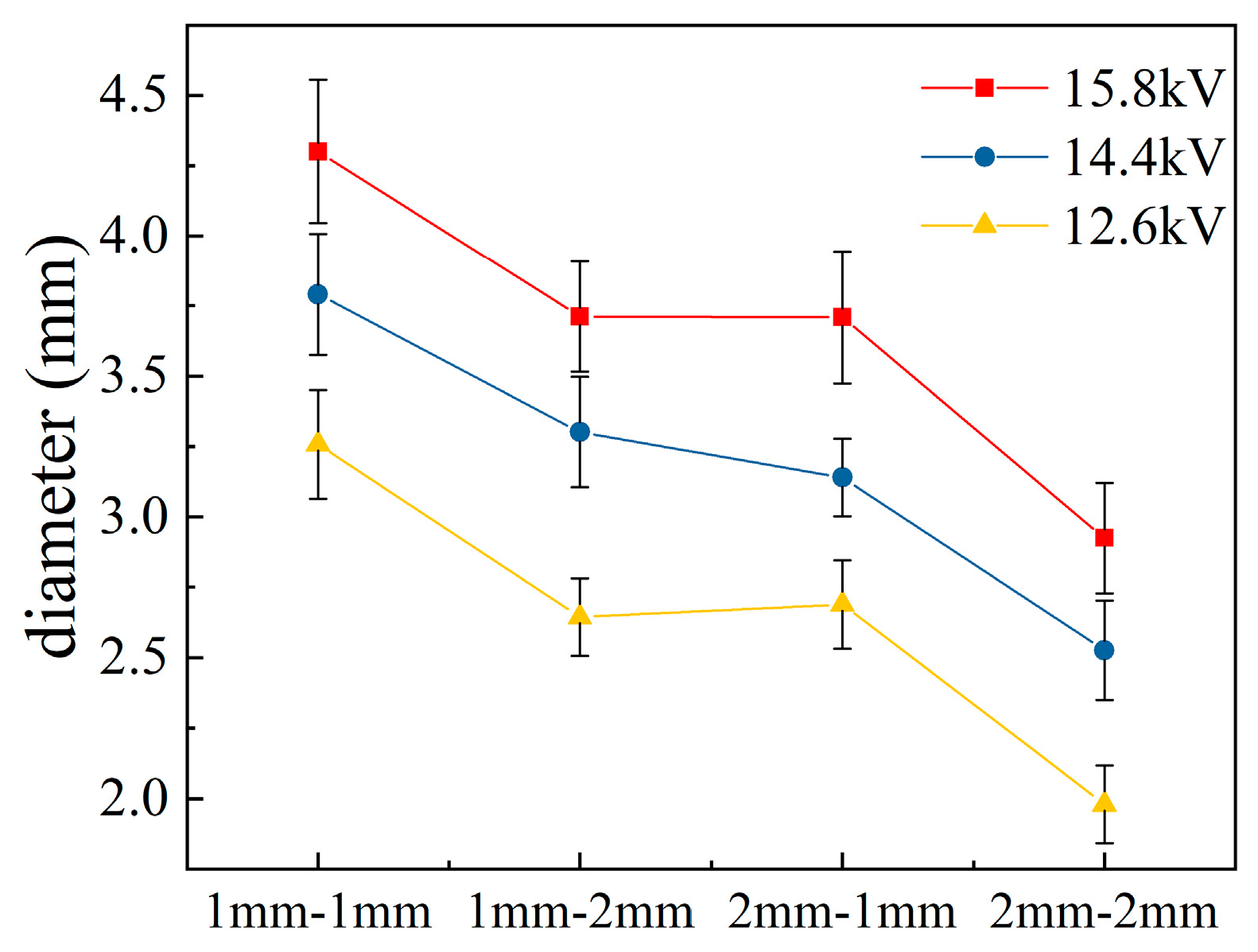

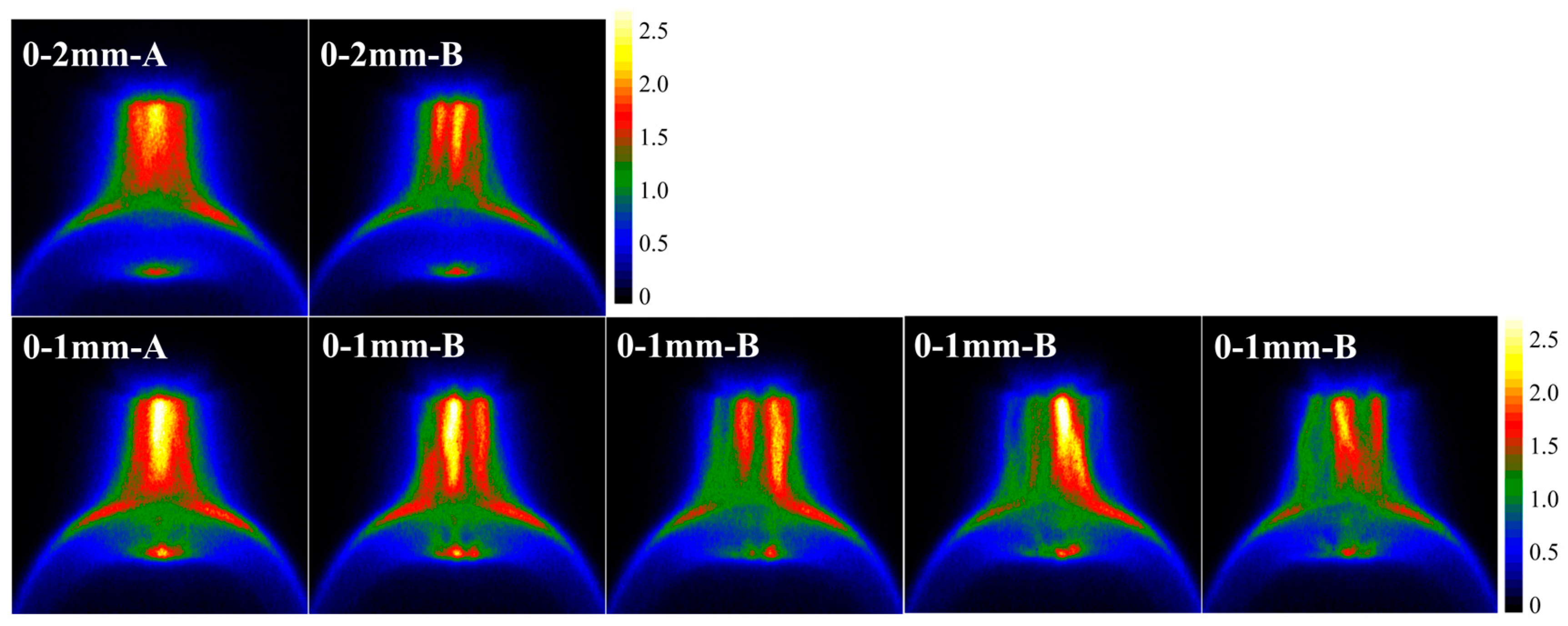

3.1. Experimental Results of DBD with Different Dielectric Thicknesses

3.2. Simulation Results of DBD with Different Dielectric Thicknesses

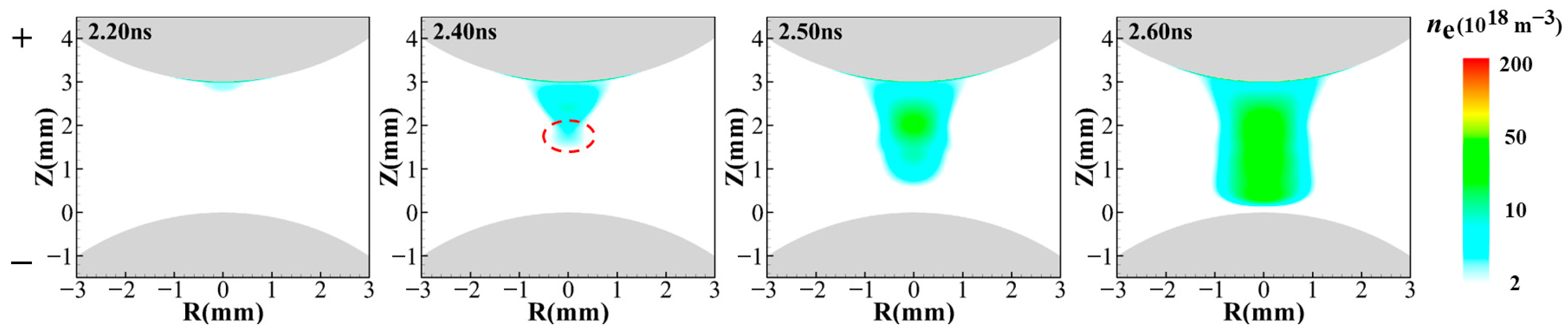

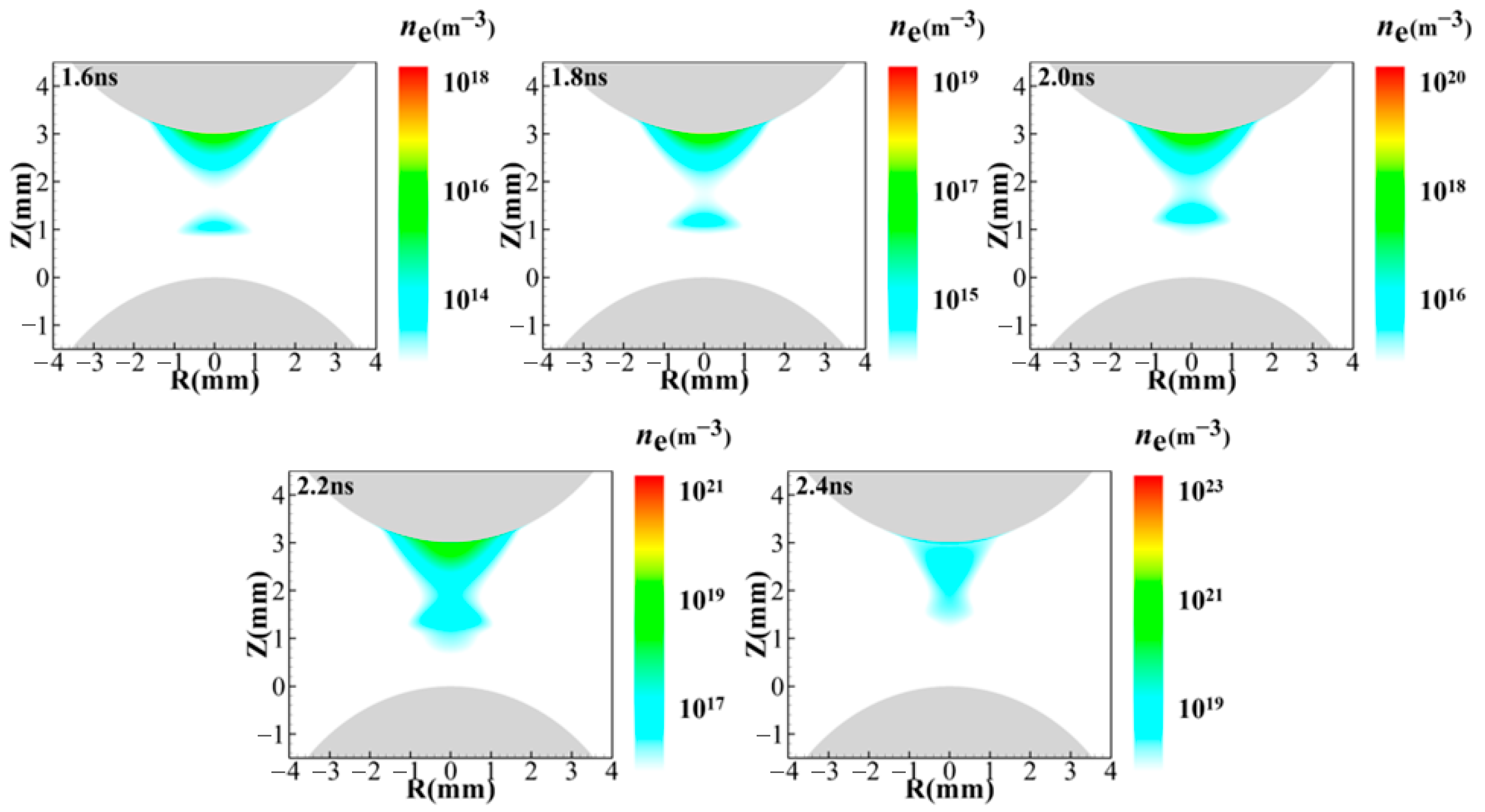

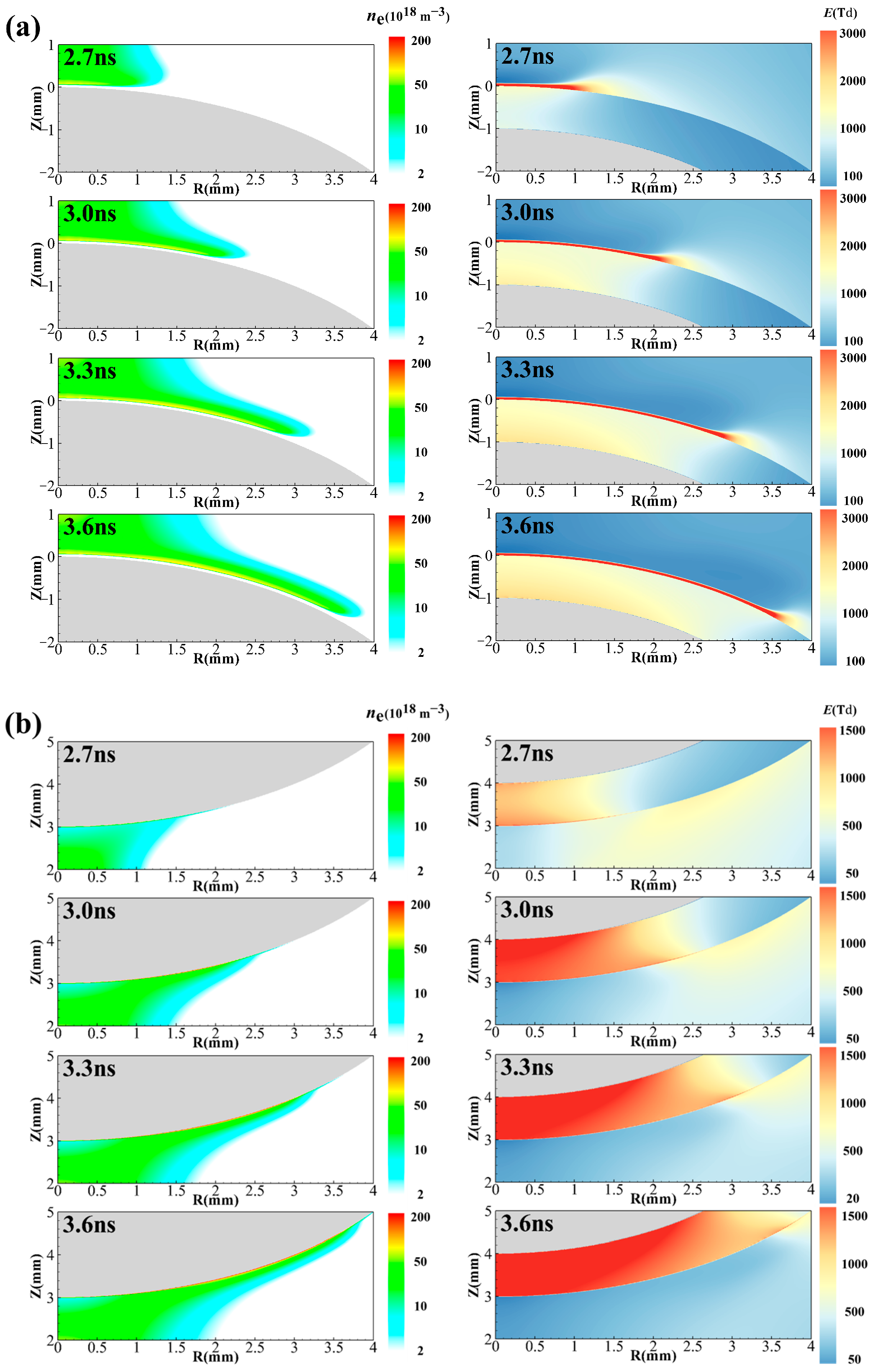

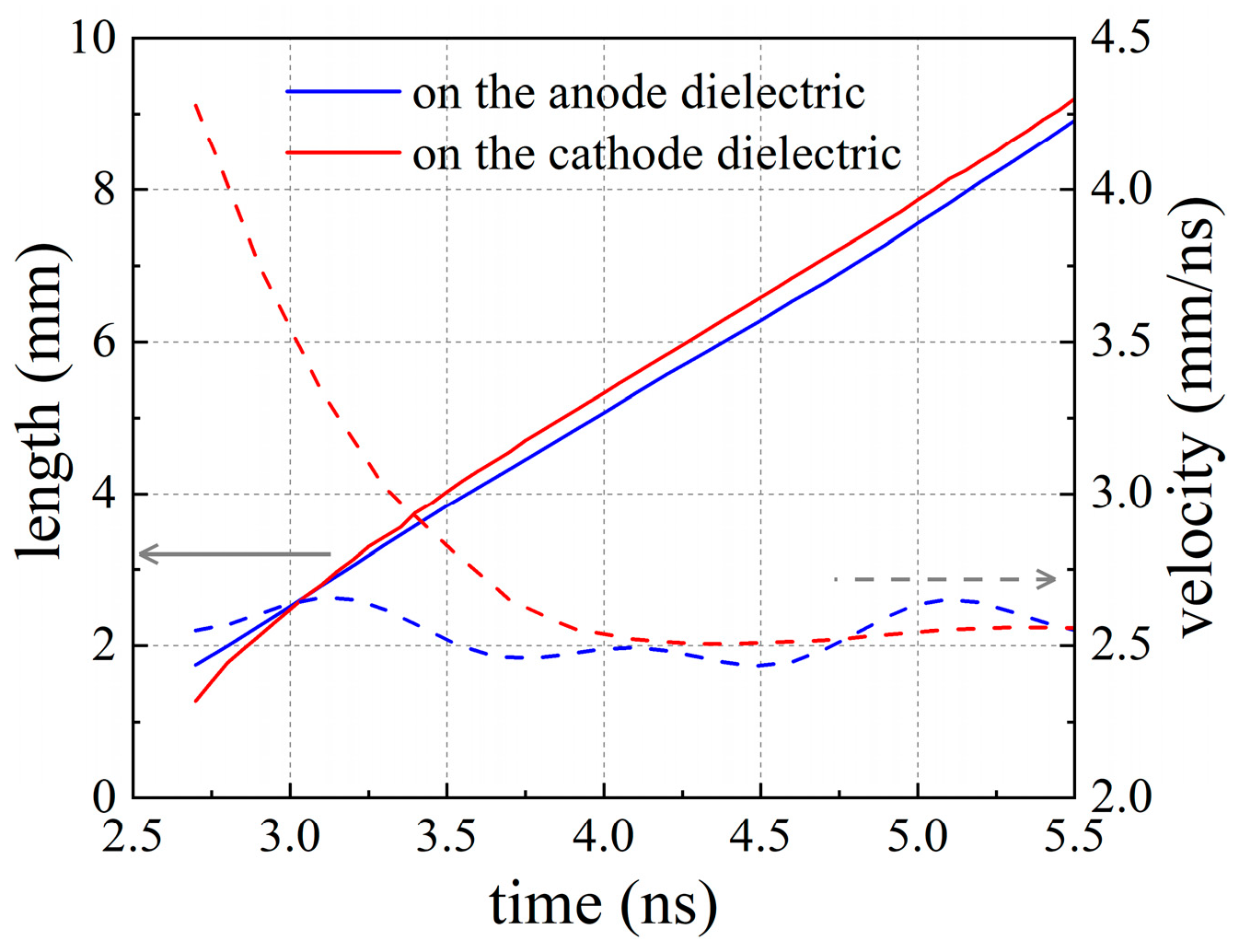

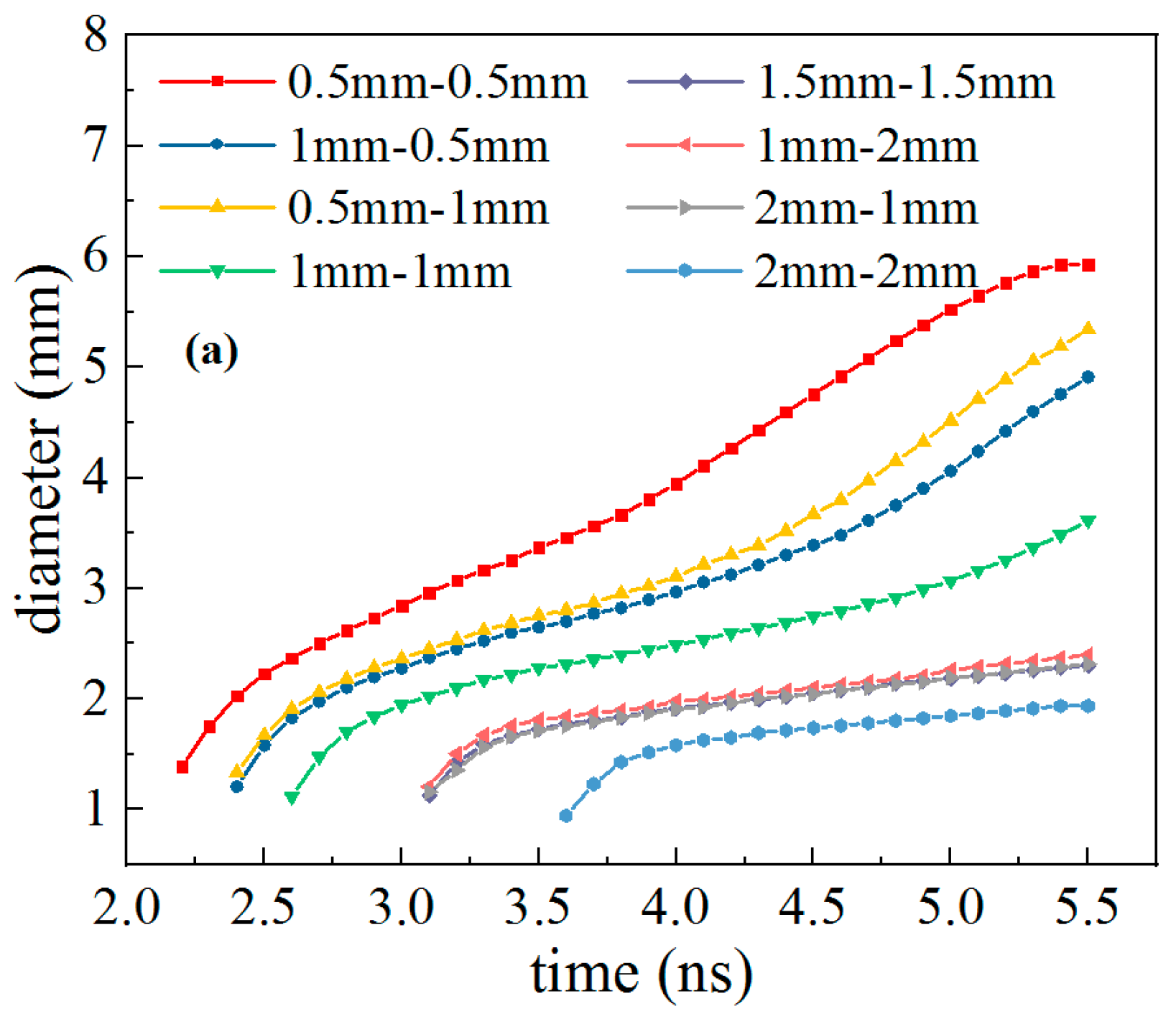

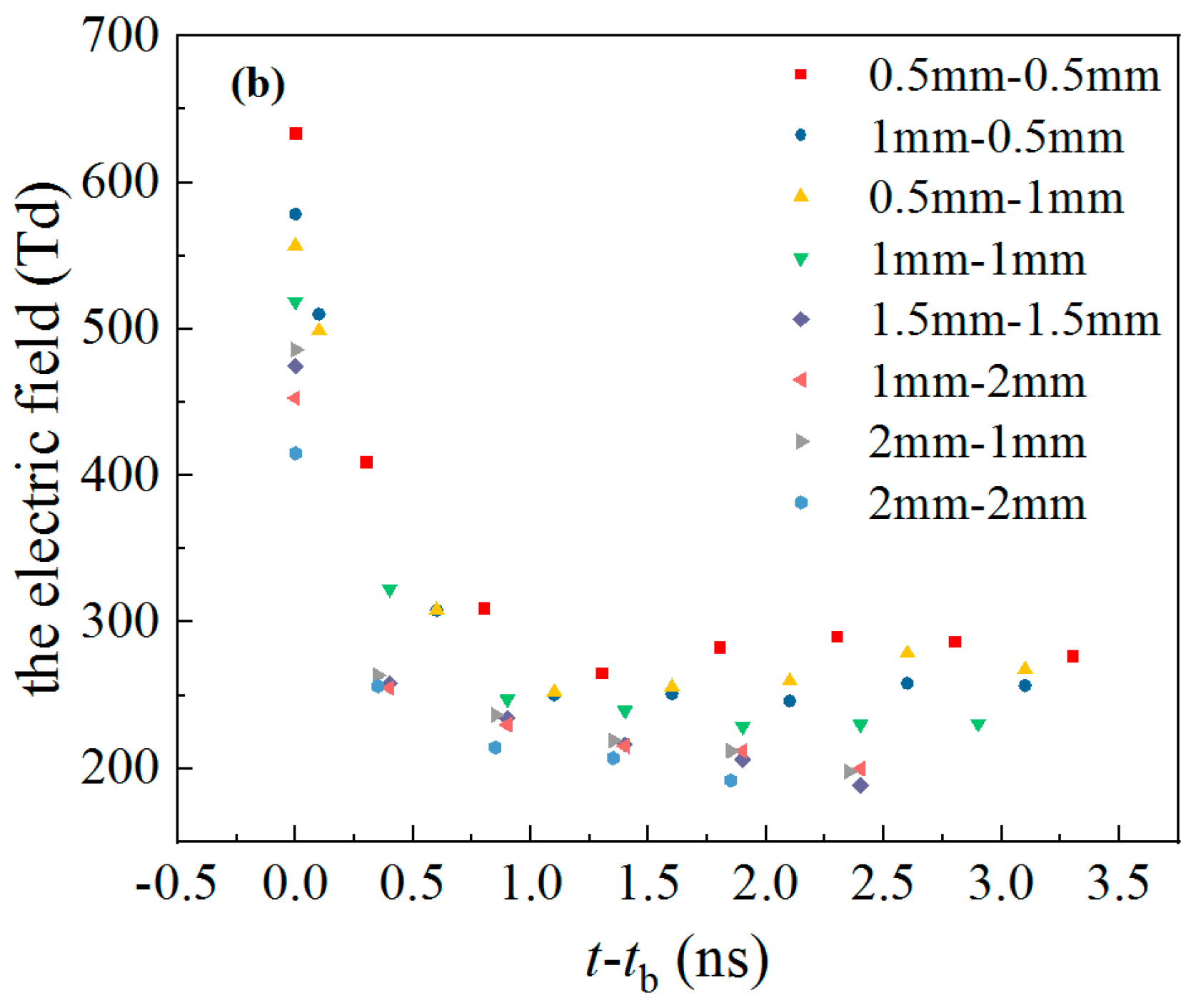

3.2.1. Discharge Propagation

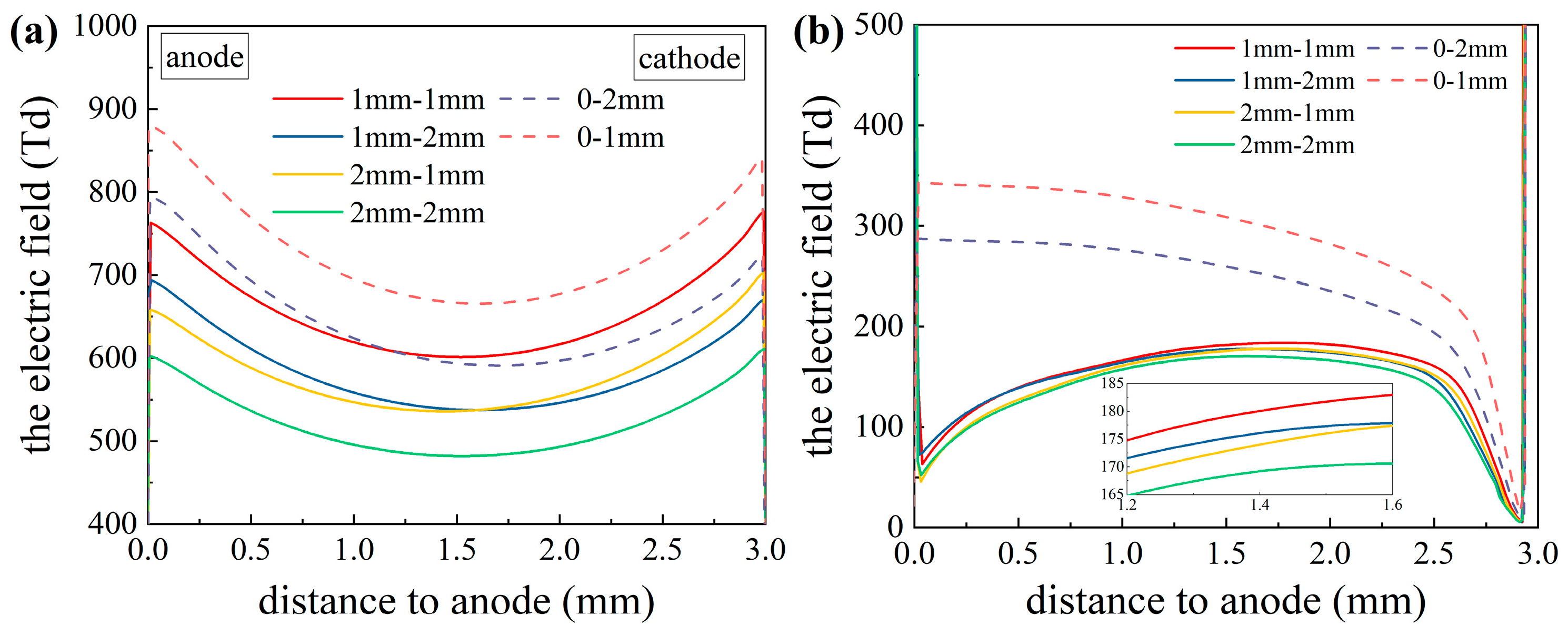

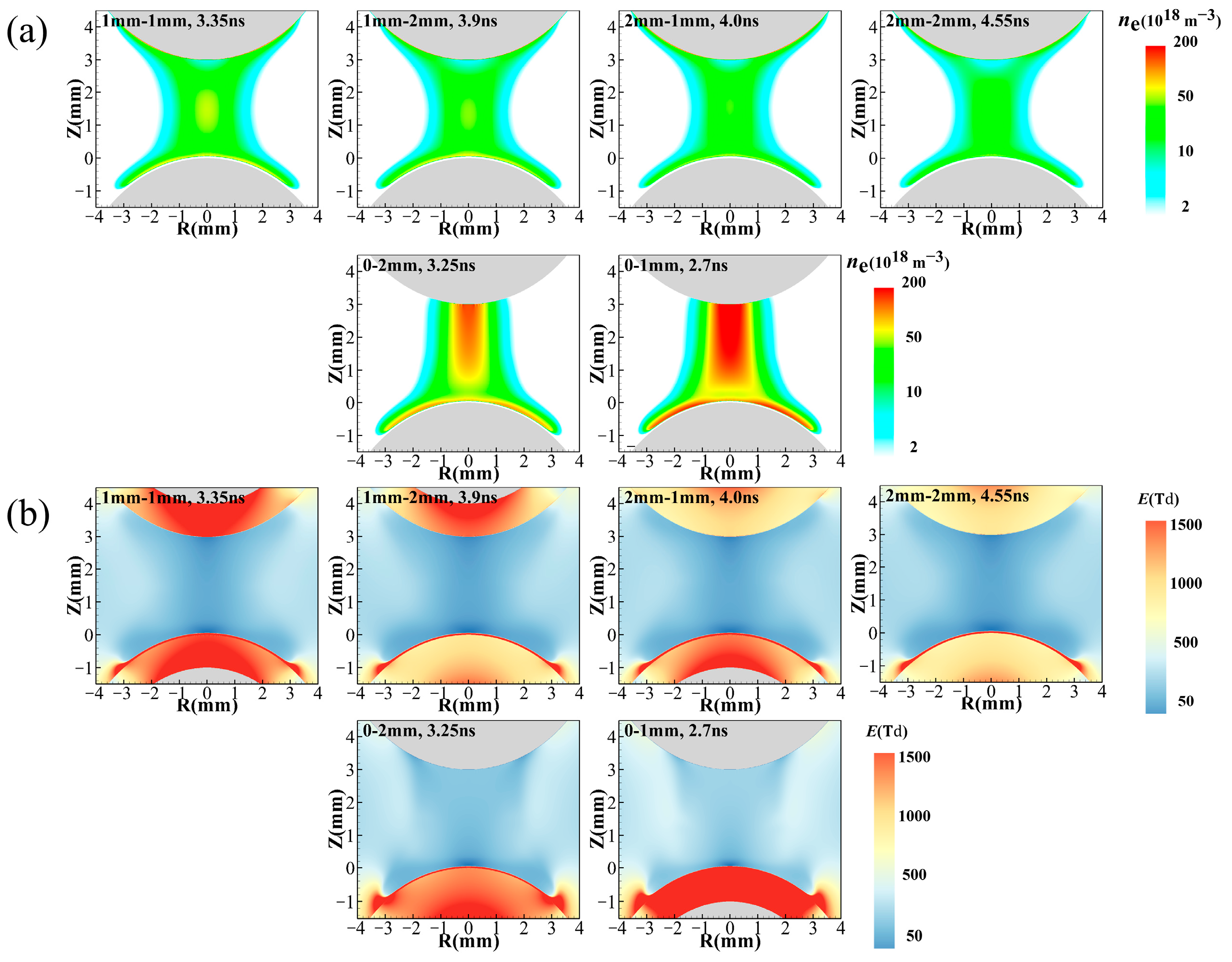

3.2.2. Comparison of DBDs with Different Dielectric Thicknesses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laroussi, M. Low Temperature Plasma-Based Sterilization: Overview and State-of-the-Art. Plasma Process. Polym. 2005, 2, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machala, Z.; Graves, D.B. Frugal Biotech Applications of Low-Temperature Plasma. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitha Gracy, T.K.; Gupta, V.; Mahendran, R. Influence of low-pressure nonthermal dielectric barrier discharge plasma on chlorpyrifos reduction in tomatoes. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanino, T.; Matsui, M.; Uehara, K.; Ohshima, T. Inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores on the surface of small spheres using low-pressure dielectric barrier discharge. Food Control 2020, 109, 106890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akishev, Y.; Grushin, M.; Napartovich, A.; Trushkin, N. Novel AC and DC non-thermal plasma sources for cold surface treatment of polymer films and fabrics at atmospheric pressure. Plasmas Polym. 2002, 7, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, R.E., 2nd; Singh, R.; Hatcher, H.C.; Kock, N.D.; Torti, S.V.; Davalos, R.V. Treatment of breast cancer through the application of irreversible electroporation using a novel minimally invasive single needle electrode. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 123, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.C.; Jaroszeski, M.J.; Coppola, D.; McCray, A.N.; Hickey, J.; Heller, R. Optimization of cutaneous electrically mediated plasmid DNA delivery using novel electrode. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Jia, L.; Wang, W.-C.; Yang, D.-Z. Processes of Raising Voltage and Reducing Voltage in Needle-Plate Dielectric Barrier Discharge. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2013, 41, 2527–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xia, D.; Luo, B.; Chen, W.; Bian, K.; Xiang, N. Simulation of positive streamer propagation in an air gap with a GFRP composite barrier. High Volt. 2021, 6, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tang, M.; Zhou, D.; Kang, P.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C. Hysteresis characteristics of the initiating and extinguishing boundaries in a nanosecond pulsed DBD. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Chu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, X.; Jia, P.; Dong, L. Surface discharge induced interactions of filaments in argon dielectric barrier discharge at atmospheric pressure. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, P.; Brandenburg, R. Atmospheric pressure discharge filaments and microplasmas: Physics, chemistry and diagnostics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 464001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jidenko, N.; Petit, M.; Borra, J.P. Electrical characterization of microdischarges produced by dielectric barrier discharge in dry air at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 39, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Lu, X.; Kolobov, V.; Arslanbekov, R. Power consideration in the pulsed dielectric barrier discharge at atmospheric pressure. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 3028–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewraj, N.; Carman, R.J.; Merbahi, N.; Marchal, F.; Leyssenne, E. Spatiotemporal Distribution of a Monofilamentary Dielectric Barrier Discharge in Pure Nitrogen. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2011, 39, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewraj, N.; Merbahi, N.; Gardou, J.P.; Akerreta, P.R.; Marchal, F. Electric and spectroscopic analysis of a pure nitrogen mono-filamentary dielectric barrier discharge (MF-DBD) at 760 Torr. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 145201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, K.V.; Wagner, H.E.; Brandenburg, R.; Michel, P. Spatio-temporally resolved spectroscopic diagnostics of the barrier discharge in air at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2001, 34, 3164–3176. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, R.; Wagner, H.E.; Morozov, A.M.; Kozlov, K.V. Axial and radial development of microdischarges of barrier discharges in N2/O2 mixtures at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurgelenas, Y.V.; Wagner, H.E. A computational model of a barrier discharge in air at atmospheric pressure: The role of residual surface charges in microdischarge formation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 39, 4031–4043. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorghiou, L.; Panousis, E.; Loiseau, J.F.; Spyrou, N.; Held, B. Two-dimensional modelling of a nitrogen dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) at atmospheric pressure: Filament dynamics with the dielectric barrier on the cathode. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 105201. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.M.; Hoder, T.; Brandenburg, R.; Loffhagen, D. Analysis of microdischarges in asymmetric dielectric barrier discharges in argon. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 355203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeva, N.Y.; Kushner, M.J. Ion energy and angular distributions onto polymer surfaces delivered by dielectric barrier discharge filaments in air: I. Flat surfaces. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2011, 20, 035017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, A.P.; Stankov, M.N.; Loffhagen, D.; Becker, M.M. Automated Fluid Model Generation and Numerical Analysis of Dielectric Barrier Discharges Using Comsol. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2021, 49, 3710–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlitz, M.; Höft, H.; Hoder, T.; Reuter, S.; Weltmann, K.D.; Brandenburg, R. On the spatio-temporal development of pulsed barrier discharges: Influence of duty cycle variation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2012, 45, 245201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlitz, M.; Höft, H.; Hoder, T.; Weltmann, K.D.; Brandenburg, R. Comparison of sinusoidal and pulsed-operated dielectric barrier discharges in an O2/N2 mixture at atmospheric pressure. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2013, 22, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Zhang, C.; Yu, Y.; Niu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Yan, P.; Zhou, Y. Discharge characteristic of nanosecond-pulse DBD in atmospheric air using magnetic compression pulsed power generator. Vacuum 2012, 86, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.-Z.; Nie, D.-X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.-C. A homogeneous dielectric barrier discharge plasma excited by a bipolar nanosecond pulse in nitrogen and air. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2012, 21, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Neiger, M. Excitation of dielectric barrier discharges by unipolar submicrosecond square pulses. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2001, 34, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höft, H.; Becker, M.M.; Kettlitz, M. Correlation of axial and radial breakdown dynamics in dielectric barrier discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 03LT01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höft, H.; Becker, M.M.; Loffhagen, D.; Kettlitz, M. On the influence of high voltage slope steepness on breakdown and development of pulsed dielectric barrier discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 064002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Collective phenomena in volume and surface barrier discharges. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 257, 012015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibalov, V.I.; Drimal, J.; Wronski, M.; Samoilovich, V.G. Barrier Discharge The Transferred Charge and Ozone Synthesis. Contrib. Plasma Phys. 1991, 31, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A.; Dufour, T.; Bogaerts, A.; Reniers, F. How do the barrier thickness and dielectric material influence the filamentary mode and CO2 conversion in a flowing DBD? Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 045016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiners, A.; Leck, M.; Abel, B. Efficiency enhancement of a dielectric barrier plasma discharge by dielectric barrier optimization. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2010, 81, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shcherbanev, S.; Baron, B.; Starikovskaia, S. Nanosecond surface dielectric barrier discharge in atmospheric pressure air: I. measurements and 2D modeling of morphology, propagation and hydrodynamic perturbations. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2017, 26, 125004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Starikovskaia, S. Fast gas heating of nanosecond pulsed surface dielectric barrier discharge: Spatial distribution and fractional contribution from kinetics. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 124007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G. Upstream Nonoscillatory Advection Schemes. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2008, 136, 4709–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwer, J.G.; Sommeijer, B.P.; Hundsdorfer, W. RKC time-stepping for advection-diffusion-reaction problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2004, 201, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon, A.; Pasko, V.P.; Liu, N.Y.; Célestin, S.; Ségur, P.; Marode, E. Efficient models for photoionization produced by non-thermal gas discharges in air based on radiative transfer and the Helmholtz equations. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2007, 16, 656–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, O.; Gartner, K. Solving unsymmetric sparse systems of linear equations with PARDISO. In Computational Science—ICCS 2002 Proceedings Part II; Sloot, P., Tan, C.J.K., Dongarra, J.J., Hoekstra, A.G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2330, pp. 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld, P. CGS, A Fast Lanczos-Type Solver For Nonsymmetric Linear-Systems. Siam J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1989, 10, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ventzek, P.L.G.; Sommerer, T.J.; Hoekstra, R.J.; Kushner, M.J. 2-Dimensional Hybrid Model of Inductively-Coupled Plasma Sources for Etching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1993, 63, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Barbieri, L.; Gondola, M.; Malgesini, R. An asymptotic preserving scheme for the streamer simulation. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 242, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Hao, J.; Ma, X.; Lu, P.; Tardiveau, P. Simulation of ionization-wave discharges: A direct comparison between the fluid model and E-FISH measurements. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2021, 30, 075025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, A.V.; Pitchford, L.C. Anisotropic Scattering of Electrons by N2 and Its Effect on Electron-Transport. Phys. Rev. A 1985, 31, 2932–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, S.A.; Phelps, A.V. Excitation of b 1∑+g State of O2 by Low-Energy Electrons. J. Chem. Phys. 1978, 69, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, N.A. Fast gas heating in a nitrogen-oxygen discharge plasma: I. Kinetic mechanism. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 285201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheshnyi, S.; Nudnova, M.; Starikovskii, A. Development of a cathode-directed streamer discharge in air at different pressures: Experiment and comparison with direct numerical simulation. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 71, 016407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossyi, I.A.; Kostinsky, A.Y.; Matveyev, A.A.; Silakov, V.P. Kinetic scheme of the non-equilibrium discharge in nitrogen-oxygen mixtures. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1992, 1, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitelli, M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Gordiets, B.F.; Osipov, A.I. Plasma Kinetics in Atmospheric Gases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.-H. Modeling study on the effects of pulse rise rate in atmospheric pulsed discharges. Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 023509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouaghi, A.; Mekhaldi, A.; Gouri, R.; Zouzou, N. Analysis of nanosecond pulsed and square AC dielectric barrier discharges in planar configuration: Application to electrostatic precipitation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, A.P.; Loffhagen, D.; Becker, M.M. Streamer–surface interaction in an atmospheric pressure dielectric barrier discharge in argon. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2022, 31, 04LT02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dijcks, S.; Guo, Y.H.; van der Leegte, M.; Sun, A.B.; Ebert, U.; Nijdam, S.; Teunissen, J. Quantitative modeling of streamer discharge branching in air. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 085007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal | Dielectric | Open Boundary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Anode: φ = U(t), cathode: φ = 0 | ∂φ/∂t = 0 | / |

| Flow towards boundary | ∂Γe/∂n = 0, ∂Γi/∂n = 0 | Charge accumulation | ∂Γe/∂n = 0, ∂Γi/∂n = 0 |

| Flow away from the boundary | Γe = −γΓi *, Γi = 0 | Γe = −γΓi *, Γi = 0 | ∂Γe/∂n = 0, ∂Γi/∂n = 0 |

| No. | Reaction | Rate Constant * | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | e + N2 + e + e | f(σ,ε) | [45] |

| R2 | e + O2 + e + e | f(σ,ε) | [46] |

| R3 | e + N2 e + N2(A3Σu) | f(σ,ε) | [45] |

| R4 | e + N2 e + N2(B3Πg) | f(σ,ε) | [45] |

| R5 | e + N2 e + N2(C3Πu) | f(σ,ε) | [45] |

| R6 | e + O2 e + O + O | f(σ,ε) | [46,47] |

| R7 | e + O2 e + O + O(1D) | f(σ,ε) | [46,47] |

| R8 | N2+ + N2 + M + M | 5 × 10−29 | [47,48] |

| R9 | N4+ + O2 O2+ + N2 + N2 | 2.5 × 10−10 | [47,48] |

| R10 | + O2 O2+ + N2 | 6 × 10−11 | [47,48] |

| R11 | O2+ + N2 + N2 N2 + N2 | 9 × 10−31 | [48] |

| R12 | N2 + N2 + N2 + N2 | 4.3 × 10−10 | [48] |

| R13 | N2 + O2 + N2 | 1 × 10−9 | [48] |

| R14 | + O2 + M + M | 2.4 × 10−30 | [47,48] |

| R15 | e + O2 + O2 + O2 | 2 × 10−29 × (300/Te) | [48] |

| R16 | e + O2 O− + O | f(σ,ε) | [46] |

| R17 | O− + O O2 + e | 5 × 10−10 | [49] |

| R18 | + O O2 + O + e | 1.5 × 10−10 | [50] |

| R19 | e + N2 + N2(C3Πu) | 2 × 10−6 × (300/Te)0.5 | [47] |

| R20 | e + N + N+ 2.25 eV | 2.8 × 10−7 × (300/Te)0.5 | [49] |

| R21 | e + O + O + O2 | 1.4 × 10−6 × (300/Te)0.5 | [47,48] |

| R22 | e + O + O + 5.0 eV | 2 × 10−7 × (300/Te) | [47,48] |

| R23 | + O2 + O2 + O2 | 1 × 10−7 | [48] |

| R24 | + M O2 + O2 + O2 + M | 2 × 10−25 × (300/Tgas)3.2 | [48] |

| R25 | + + M O2 + O2 + M | 2 × 10−25 × (300/Tgas)3.2 | [48] |

| R26 | O− + O + N + N | 1 × 10−7 | [49] |

| R27 | N2(C3Πu) + N2 N2(B3Πg,v) + N2 | 1 × 10−11 | [47] |

| R28 | N2(C3Πu) + O2 N2 + O + O(1D) | 3 × 10−10 | [47] |

| R29 | N2(C3Πu) N2 + hv | 2.38 × 107 | [48] |

| R30 | N2(B3Πg) + O2 N2 + O + O | 3 × 10−10 | [47] |

| R31 | N2(B3Πg) + N2 N2(A3Σu)+ N2(v) | 1 × 10−11 | [47] |

| R32 | N2(A3Σu) + O2 N2 + O + O | 2.5 × 10−12 × (Tgas/300)0.5 | [47] |

| R33 | O(1D) + O2 O + O2 | 3.3 × 10−11 × exp(67/Tgas) | [47] |

| R34 | O(1D) + N2 O + N2 | 1.8 × 10−11 × exp(107/Tgas) | [47] |

| R35 | O + O2 + O2 O3 + O2 | 6.9 × 10−34 × (300/Tgas)1.25 | [49] |

| R36 | O + O2 + N2 O3 + N2 | 6.9 × 10−34 × (300/Tgas)2 | [49] |

| R37 | O + O3 O2 + O2 | 2 × 10−11 × exp(−2300/Tgas) | [49] |

| R38 | + O3 + O + N2 | 1 × 10−10 | [49] |

| R39 | e + O3 + O | 1 × 10−9 | [49] |

| No. | Anode Dielectric Thickness (Da) | Cathode Dielectric Thickness (Dc) | Anode Diameter | Cathode Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 mm | 1 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

| 2 | 1 mm | 2 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

| 3 | 2 mm | 1 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

| 4 | 2 mm | 2 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

| 5 | 0 (metal) | 1 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

| 6 | 0 (metal) | 2 mm | 10 mm | 10 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, A.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Effect of Dielectric Thickness on Filamentary Mode Nanosecond-Pulse Dielectric Barrier Discharge at Low Pressure. Plasma 2026, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010004

Sun A, Guo Y, Li Y, Zhu Y. Effect of Dielectric Thickness on Filamentary Mode Nanosecond-Pulse Dielectric Barrier Discharge at Low Pressure. Plasma. 2026; 9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Anbang, Yulin Guo, Yanru Li, and Yifei Zhu. 2026. "Effect of Dielectric Thickness on Filamentary Mode Nanosecond-Pulse Dielectric Barrier Discharge at Low Pressure" Plasma 9, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010004

APA StyleSun, A., Guo, Y., Li, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2026). Effect of Dielectric Thickness on Filamentary Mode Nanosecond-Pulse Dielectric Barrier Discharge at Low Pressure. Plasma, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010004