Abstract

Electricity is widely regarded as the most adaptable form of energy and a major secondary energy source. However, electricity is not economically storable; therefore, the power system requires a continuous balance of electricity production and consumption to be stable. The accurate and reliable assessment of electrical energy consumption enables planning prospective power-producing systems to satisfy the expanding demand for electrical energy. Since Saudi Arabia is one of the top electricity consumers worldwide, this paper proposed an electricity consumption prediction model in Saudia Arabia. In this work, the authors obtained a never-before-seen dataset of Saudi Arabia’s electricity consumption for a span of ten years. The dataset was acquired solely by the authors from the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC), and it has further research potential that far exceeds this work. The research closely examined the performance of ensemble models and the K* model as novel models to predict the monthly electricity consumption for eighteen service offices from the Saudi Electrical Company dataset, providing experiments on a new electricity consumption dataset. The global blend parameters for the K* algorithm were tuned to achieve the best performance for predicting electricity consumption. The K* model achieved a high accuracy, and the results of the correlation coefficient (CC), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean squared percentage error (RMSPE), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean squared error (RMSE) were 0.9373, 0.1569, 0.5636, 0.016, and 0.0488, respectively. The obtained results showed that the bagging ensemble model outperformed the standalone K* model. It used the original full dataset with K* as the base classifier, which produced a 0.9383 CC, 0.1511 MAPE, 0.5333 RMSPE, 0.0158 MAE, and 0.0484 RMSE. The outcomes of this work were compared with a previous study on the same dataset using an artificial neural network (ANN), and the comparison showed that the K* model used in this study performed better than the ANN model when compared with the standalone models and the bagging ensemble.

1. Introduction

Electricity is considered a significant secondary energy source and the most adaptable type of energy. The power system must maintain a constant balance between electricity generation and consumption [1]. Forecasting and prediction goals for electricity usage vary depending on the time frame. Relative time scales include long-, medium-, and short-term. This study and the majority of today’s studies consider mid-term electricity consumption, which is the monthly forecasting time frame. This is because the monthly time frame is crucial to many government and commercial decision-making processes [2,3].

Accurate electricity consumption prediction is essential for the efficient operation of today’s electric power systems [4]. Many research studies have shown the importance of accurate electricity prediction. Planning for future electricity generation systems to meet the rising demand for electrical energy is made possible through the accurate and reliable estimation of electrical energy consumption [5,6].

Saudi Arabia consumes three times the electricity of the world’s average; for instance, its consumption is eight times greater than Japan’s. If present consumption rates continue at their current levels, by 2038, Saudi Arabia may be forced to import oil to meet the energy needs of its growing population [7,8]. Therefore, accurate electricity consumption prediction is vital for developing an efficient energy development strategy in Saudi Arabia.

This research investigated the effects of using machine learning approaches in predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia. A real dataset provided by the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC) was used in this study with different machine learning models for mid-term electricity consumption. Additionally, this research studied the effects of using bagging ensemble on predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

The paper’s remaining sections are organized as follows: A literature review related to predicting electricity consumption is presented in Section 2. The materials and methods are described in Section 3. The main results are presented in Section 4, followed by the discussion in Section 5. Section 6 presents the authors’ conclusions.

2. Related Work

Numerous studies in the literature have used machine learning approaches to estimate electricity consumption. This section focuses on published studies on electricity consumption prediction and covers international-based research before focusing on Saudi-based research.

A summarization of the past literature regarding electricity consumption prediction can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review summary for electricity consumption prediction.

Within the literature, many studies have attempted to predict electricity consumption using machine learning techniques. These techniques include a self-adaptive grey fractional weighted model [9], Holt–Winters smoothing [10], ANNs [3,11,12,13], a self-adaptive screening and vector error correction model [3], support vector regression [12], a least-squares support vector machine [14], linear regression [15,16], recurrent neural networks using long short-term memory [17], an abductory induction mechanism [18], and the auto regressive integrated moving average [19].

From the literature, it can be seen that publications regarding predicting electricity consumption are scarce when compared to publications in other areas. One of the main reasons for this is the lack of specific datasets that represent accurate consumption. In Saudi Arabia, the investigated experiments obtained their datasets from local institutions that have physical or soft copies of the electricity consumption for said institutes [15,17], general statistics that are shared publicly [13], or the Saudi Consolidated Electric Company of the Eastern Province [15,17,18]. The majority of past studies attempted electricity consumption forecasting in the eastern region alone [15,17,18]. However, the specific cities included were unclear, and the region was treated as a unit. Qassim City was also investigated in [17], but the investigation was based on data from the College of Computer Science at Qassim University and not the actual city. Therefore, this research deployed a new dataset collected from the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC) for investigating how machine learning techniques perform in forecasting electricity consumption. Furthermore, the dataset utilized in this research includes the electricity consumption of all areas covered by the SEC in Saudi Arabia divided by service offices, 18 of which were included in this study (i.e., the service offices that cover the same area as tier 1 monitoring stations).

The literature implies the need to attempt electricity consumption forecasting with methods that have not been investigated before, such as instance-based machine learning methods, where there is room for investigation. Hence, this work studied the performance of the K* algorithm in predicting Saudi Arabia’s electricity consumption.

Since ensemble techniques have been shown to provide good performance, the bagging ensemble method is also investigated in this work as a potential tool for predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

Additionally, pre-processing the SEC dataset using min–max normalization had not yet been used in studies that were conducted on electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia. However, it was used in research conducted outside of Saudi Arabia [3,12]. Using min–max normalization is highly recommended for datasets with various ranges within their input features, such as electricity consumption datasets. Furthermore, despite the fact that the dataset is heavily affected by temporal characteristics such as time, no previous study mapped the time features to represent their cyclical attributes. Hence, this study investigated prediction through normalizing the input features using min–max, transforming the temporal attributes using Fourier transformation, and mapping the inputs to their sine and cosine counterparts.

In terms of how far the models predict electricity consumption, past papers predicted the consumption daily [17], monthly [3,11,12,15,17,18], semi-monthly [10], and yearly [9,13,14,15].

In terms of evaluation metrics, they varied across the literature. However, the most essential and common metric was MAPE, with almost all the past experiments utilizing it to evaluate their model. This work used CC, MAPE, RMSPE, MAE, and MAPE to evaluate the proposed machine learning models.

Provided the analysis of relevant work on predicting electricity consumption in the literature review, it is clear that predicting electricity consumption using ANN was widely used due to how well the ANN performs with large datasets. Moreover, the literature implies the need to attempt electricity consumption forecasting with methods that have not been investigated before, such as utilizing instance-based machine learning methods, where there is room for investigation. Hence, this work investigates the performance of the K* algorithm in predicting solar radiation in Saudi Arabia.

Additionally, in the literature, ensemble techniques were attempted for predicting electricity consumption in one study, although ensembles have been proven to provide good results. Therefore, this work investigates the effects of ensemble methods (i.e., bagging) on predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

From the literature, in Saudi Arabia, the experiments that investigated obtained their datasets from the local institutions that have physical or soft copies of the electricity consumption for said institutes [15,17], general statistics that are shared publicly [13], or from the Saudi Consolidated Electric Company of the Eastern Province [15,17,18]. Most of the past literature attempted electricity consumption forecasting in the eastern region alone. However, the specific cities included were unclear and the region was treated as a unit.

This work deploys a new dataset provided by the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC) for investigating the effects of machine learning techniques on predicting electricity consumption. Also, this dataset was the result of personal obtention and was not used before in any research. Furthermore, the dataset used in this work contains the electricity consumption of all areas covered by the SEC in Saudi Arabia divided by service offices, 18 of which are included in this study (i.e., the service offices that cover the same area of the tier 1 monitoring stations).

Therefore, this research closely examined the performance of ensemble models and the K* model as novel models to predict the monthly electricity consumption for eighteen service offices from the Saudi Electrical Company dataset, providing experiments on a new electricity consumption dataset.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the description of the used dataset, the methodology, and the applied machine learning techniques.

The dataset for electricity consumption was collected from the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC). The collected dataset covers the monthly electricity consumption for eighteen locations. The dataset contains the electricity consumption in Saudia Arabia from January 2010 to September 2020 and it has six attributes and includes 2298 instances. A summary of the electricity consumption dataset is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dataset description.

The methodology of this study can be summarized as follows: First, in the pre-processing phase, the values for the input features, as well as the target value, were normalized within a 0–1 range based on Equation (1).

The reason for the normalization was due to the different ranges throughout the dataset features. Then, since the nature of this study is heavily based on temporal qualities, the month feature was split into sine and cosine facets. In other words, as the month attribute is considered a cyclic attribute where month 1 (January) is closer to month 12 (December) in temporal characteristics, it was converted into 2 dimensions using the sine and cosine facets of each month based on Equations (2) and (3). Thus, they adequately represent the actual temporal similarities between months.

In this research, the dataset followed a 70–30 split so that 70% of the dataset is used in the training phase, and 30% is reserved for testing the model.

After splitting the dataset into their separate training and testing datasets, the K* method was optimized through tuning the parameters. A 10-fold cross-validation technique was used in the training phase to ensure the model was not overfitted to the test set. The K* model only had one parameter to tune: the global blend parameter.

Moreover, the bagging ensemble method was applied to the dataset. It was optimized similarly to what was performed with the standalone K* model by means of tuning their parameters.

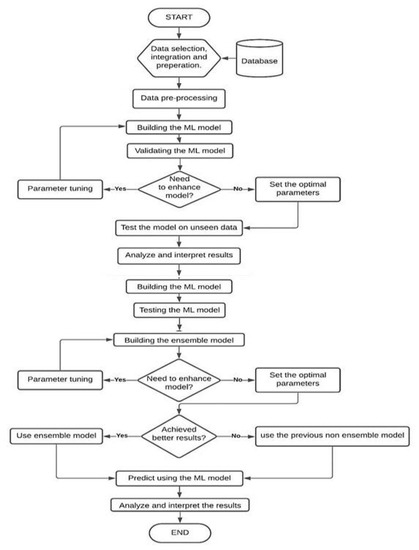

Following the parameter tuning, the models were applied to the test data to evaluate their capabilities based on various evaluation metrics, namely correlation coefficient (CC), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared percentage error (RMPSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). Equations (4)–(8) show their mathematical representations and Figure 1 shows the framework for the proposed methodology.

where and are a random pair of variables.

Figure 1.

The machine learning framework.

3.1. Technical Description of the K* Model

Kstar, often referred to as K*, is a type of instance-based machine learning algorithm where a test’s target class is decided according to the training examples that are comparable to it, as defined through some similarity measure. Generally, instance-based learners use a repository of pre-classified instances to categorize the target. The basic premise of instance-based learning is that instances that share similar characteristics will be classified similarly. The defining factor on the similarity is where many instance-based learners contrast. Furthermore, there are two main components of instance-based learners. The first component is the function that defines and measures the similarity between two examples (i.e., to what extent two examples are alike), which is referred to as the distant function. The second component is the function that determines a target instance’s classification or regression value based on the pre-defined similarities between it and the other instances, which is referred to as the classification function [25,26].

The K* algorithm uses an entropy-based distance function, which sets it apart from other instance-based learners. The entropic measure employed by the K* algorithm is based on the chance of randomly selecting among all conceivable transformations to turn one instance into another. It is particularly helpful to use entropy as a metric for calculating the distance between instances. The proximity between instances determines the complexity of a transition from one instance to another. This can be accomplished in two steps. To begin, let us assume we have two instances: A and B. The first step is to create a finite number of transformations to transform one instance into another. The second step consists of using the classification function to go through a series of finite sets of pre-defined transformations until instance A is finally mutated into instance B.

Let T be a set of pre-determined transformations and t be a value in the set T. Let I be the set of instances, and P is the collection of the prefix codes obtained by T* and terminated by σ. The value t will be then mapped into t: I→I. Furthermore, σ is used to map instances to themselves in T (σ (a) = a). T* and P components specify a transformation on I in a unique way.

t(a) = tn (tn−1(...t1(a)...)) where t = t1,...tn

T defines the probability function P as it satisfies the following:

And thus, it satisfies:

The probability value of all paths starting from instance A to B is determined according to the probability function :

The following properties of P* are easily demonstrated:

Thus, K* can be defined as:

Calculating the distance between two instances with numerous attributes is simple. The union of the transformations for the separate attributes is the set of transformations on the combined attributes. The transformation sequences may then be represented through transforming the first attribute, then the second, and so on until all the features have been altered. Consequently, the overall string’s probability is the product of the individual strings’ probabilities, and the distance function is the sum of the individual features’ distances [25].

3.2. Bagging Ensemble

In 1996, the bagging technique was formally invented by Leo Breiman [27]. Bagging is an ensemble learning technique that uses a sequence of homogenous machine learning techniques to improve performance and decrease the error rate. The main objective of the bagging technique is to build a more accurate and trustworthy model through voting or averaging many base learners. Each base classifier is trained independently using a part of the training dataset [28].

4. Experimental Results

This section presents the experimental settings and results of the proposed models for predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

The experiments in this study were conducted using the WEKA program, which stands for Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis. WEKA was created at the University of Waikato in New Zealand and is an open-source program that includes machine learning algorithms for classification, regression, analyzing, pre-processing, and visualizing data [29].

4.1. Results of Using Optimized K* Model

During the early stages and the preliminary experiments, many powerful regression models, such as support vector machine, linear regression, artificial neural networks, and random tree, were tested against the K* model to corroborate the model’s performance. These experiments further proved the potential the K* model had in tackling the problems presented in this study. The experiments show that the K* model had the best results in electricity consumption prediction, as shown in Table 3

Table 3.

Preliminary results of K* against popular machine learning models.

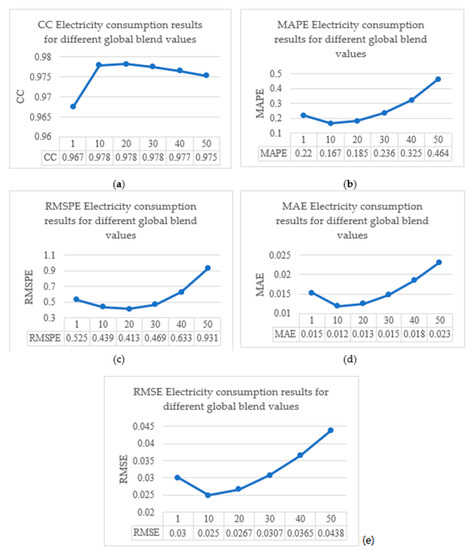

After that, the effects of tuning the hyperparameters on the electricity consumption dataset for the K* algorithm were inspected. Global blend parameter tuning was implemented via an increment of ten until the results started to worsen. The results started to decline when the global blend value increased, and the best result was when the value was at 10. Table 4 shows the experimental results of the CC, MAPE, RMSPE, RMSE, and MAE for different global blend values.

Table 4.

Performance of the K* algorithm with different global blend values on the electricity consumption dataset.

Results from tuning the global blend on the K* model for the electricity consumption dataset show that the optimal values for all metrics were obtained through setting the parameter to 10.

Moreover, Figure 2 illustrates the effects of the global blend of the K* model on the CC, MAPE, RMSE, RMSPE, and MAE for electricity consumption prediction.

Figure 2.

Illustrating the effects of the global blend of the K* model: (a) global blends and their CC values on the electricity consumption dataset; (b) global blends and their MAPE values on the electricity consumption dataset; (c) global blends and their RMSPE values on the electricity consumption dataset; (d) global blends and their MAE values on the electricity consumption dataset; (e) global blends and their RMSE values on the electricity consumption dataset.

Figure 2 shows that the values continue to enhance for CC, MAPE, RMSPE, MAE, and RMSE as the global blend increases until it reaches around 10 marks, where the results stop improving beyond that point.

The optimized value of the global blend parameter on the electricity consumption dataset is 10, which is used to build the optimized K* model.

Table 5 shows the results of applying the K* model with the optimal value on both the training and testing datasets, where values for CC, MAPE, RMSPE, MAE, and RMSE are presented.

Table 5.

The results of electricity consumption prediction using the K* algorithm.

4.2. Results of Using Bagging Technique

The bagging ensemble was applied to the dataset of electricity consumption in order to improve the results. WEKA’s bagging method was used to carry out the experiment. The classifier that was selected to be used for the prediction was the only parameter that was altered during the experiment. The parameter was modified to use the optimized K* model as the selected classifier. Table 6 shows the testing outcomes of applying the bagging model to the dataset of electricity consumption.

Table 6.

Electricity consumption prediction using the K* algorithm with bagging ensemble.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the obtained results and presents a comparison between the performance of electricity consumption prediction in this work with the electricity consumption prediction in similar work in the literature.

Although the bagging ensemble using the K* model did improve on the results obtained by the standalone model, these improvements were not major. The bagging K* model improved on the CC, MAPE, RMSPE, MAE, and RMSE by 0.11%, 3.7%, 5.38%, 1.25%, and 0.82%, respectively. Both initial results from the standalone model and the best results gained from the bagging ensemble can effectively predict the next month’s electricity consumption.

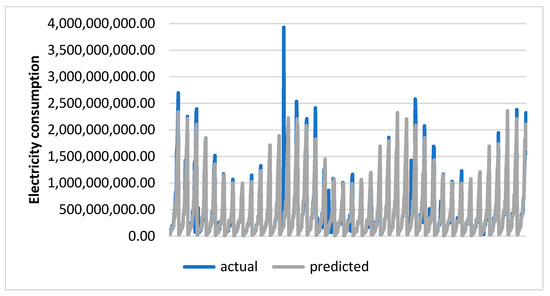

Figure 3 shows the actual consumption values vs. the predicted consumption values in Kilowatts by the proposed model.

Figure 3.

Actual vs. predicted monthly mean Kilowatt values using the proposed model.

Since the same dataset used in this study was also used in [30], the work conducted in this study using the K* algorithm is compared with the work of electricity consumption prediction using the ANN in [30]. Thus, this section shows the comparison between the performance of electricity consumption prediction in this work with the electricity consumption prediction in [30].

Table 7 provides the results of the standalone ANN in [30] and standalone K* models in this study after they were performed on the training dataset and testing dataset.

Table 7.

Performance of the optimized ANN and K* for predicting electricity consumption.

From Table 7, the results in [30] showed that the CC for the ANN reduced by 8% when the models were evaluated using the testing dataset. Also, MAE was increased by 204% from the training model. As for MAPE, RMSE, and RMSPE, all increased by 72.4%, 224%, and 41%, respectively.

As for the performance of the K* model, after evaluating the model on the testing dataset, it was found that the value for CC was decreased by 4.1% compared to the results on the training dataset. Moreover, for MAE, there was a 35.5% increase compared with the results on the training dataset. RMSE also increased by 95.2%. MAPE showed a decrease of 5.9%, and RMSPE increased by 28.2%.

When comparing the two models in terms of how well they generalize to new data, it is evident that the K* algorithm surpasses the ANN. This can be seen in the difference of the values for CC, RMSPE, RMSE, and MAE. Moreover, K* had the best MAPE when performed on unseen data.

When comparing the results of the ANN with the K* model regarding how differently they perform on the training and testing sets, it can be seen that the results vary. For example, the CC value of the ANN on the training set was the best overall; however, it was also the worst overall after performing it on the unseen data, whereas the K* model’s CC exhibited the best performance on the testing set. The CC difference between the ANN and K* on the training set was 0.37%, whereas the difference between K* and the ANN on the testing set was 3.73% in favor of the K* model. As for the MAPE, K* outperformed the ANN in both situations with a 38.1% and 64.5% difference in the training and testing sets, respectively. Similarly, K* also outperformed the ANN through having a better RMSPE of 20.8% for the training dataset and 17.1% for the test set. When comparing the MAE of the training set of both models, it can be seen that their values are almost identical. However, K* performs 54.6% better on the unseen data. Similarly, the values of the RMSE for the training set of both models are almost identical, with a 10% difference in favor of the ANN. Nonetheless, K* produces a better RMSE when performed on the unseen data in the test set with a 34.3% improvement when compared with the ANN.

Regarding the bagging ensemble and comparing with the work in [30] using the ANN technique on the same electricity consumption dataset used in this research, it is clear that the bagging ensemble with the optimized K* model outperforms its ANN counterpart in all metrics except for the RMSPE. Moreover, although the RMSPE that was produced using the ANN as the base classifier was better, the difference is a low value of 0.07. Therefore, the optimal parameter with the bagging ensemble is to use the optimized K* algorithm as the chosen classifier.

In conclusion, using the bagging ensemble with the optimized K* algorithhm produced the best results.

To compare and summarize the key work performed in this study and the work that has been carried out in [30] on electricity consumption prediction, the results are arranged in a tabular manner. The best results of all the ANN and K* models in every experiment performed on the electricity consumption dataset are shown in Table 8, along with the type of experiments and any other key notes to take into consideration.

Table 8.

Best experimental results on electricity consumption prediction.

As evident from Table 8, the K* model performed better than the ANN model when compared with the standalone models and the bagging ensemble.

Furthermore, a comparison between the work completed in this study and past electricity consumption studies is shown below in Table 9.

Table 9.

Proposed electricity consumption prediction model vs. past models.

From Table 9, it is evident that among the literature on predicting electricity consumption, the models are highly diverse. Every model is different in all aspects, methodology, the span of the data, the cities included, the splitting technique, the included features, and even the goal of the model itself (daily, yearly, monthly). Furthermore, the evaluation metrics amongst each paper differed. However, generally, it is apparent that the proposed electricity consumption model performs adequately in forecasting electricity consumption for eighteen locations throughout the Kingdom.

Although the findings of this study are encouraging, several limitations should be considered before drawing conclusions. The study covers only 18 locations in Saudia Arabia and the models were built for monthly consumption prediction; they could also be built on different data intervals such as daily and hourly. In addition, feature selection techniques were not investigated in this study. For future work, the authors plan to experiment with different feature selection techniques to improve the performance of the models. Also, since fuzzy logic has already proven itself in predicting electricity consumption [31], it will be investigated in predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

6. Conclusions

Electricity consumption prediction is essential for electric power networks to run efficiently. An accurate and reliable estimation of electricity consumption is necessary to plan for future electricity production systems to meet the rising demand for electrical energy. Since Saudi Arabia is one of the top electricity consumers worldwide, this research proposed a prediction model for electricity consumption in Saudia Arabia.

The proposed models were developed using a new dataset provided by the Saudi Electrical Company for investigating the effects of machine learning techniques on predicting electricity consumption. Also, this dataset was the result of personal obtention and was not used before in any research. Furthermore, the dataset used in this work contains the electricity consumption of all areas covered by the SEC in Saudi Arabia divided by service offices, 18 of which are included in this study.

This study used standalone K* and bagging ensemble models to predict electricity consumption for different regions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The results show that the bagging ensemble using a K* model outperformed the results obtained using the standalone model and achieved 0.9383 CC, 0.1511 MAPE, 0.5333 RMSPE, 0.0158 MAE, and 0.0484 RMSE. The experimental results achieved in this work were compared with the results of a previous study with the same dataset, and results show that the K* model performed better than the ANN model in the previous study when compared with the standalone models and the bagging ensemble. Furthermore, a comparison between the work performed in this study and past electricity consumption studies shows that the proposed electricity consumption model adequately forecasts electricity consumption for eighteen locations throughout Saudia Arabia.

For future work, feature selection techniques as well as more machine learning models can be investigated. In addition, since fuzzy logic has already proven itself in predicting electricity consumption, it will be investigated in predicting electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, methodology, and proofreading, D.A.M.; implementation, analyses, and original draft preparation, M.A.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this work is available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Saudi Electrical Company (SEC) for providing the electricity consumption data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weron, R. Electricity price forecasting: A review of the state-of-the-art with a look into the future. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 1030–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lin, C.-J. Load Forecasting Using Support Vector Machines: A Study on EUNITE Competition 2001. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C.; Zhang, X. A monthly electricity consumption forecasting method based on vector error correction model and self-adaptive screening method. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 95, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, K.B.; Mourshed, M. Forecasting methods in energy planning models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 88, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-G.; Jung, J.-Y.; Sim, M.K. A Two-Step Approach to Solar Power Generation Prediction Based on Weather Data Using Machine Learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumsack, S.; Fernandez, A. Ready or not, here comes the smart grid! Energy 2012, 37, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Khan, S.A. Transition towards sustainable energy production—A review of the progress for solar energy in Saudi Arabia. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2018, 36, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaraashi, M. Short-term prediction of solar energy in Saudi Arabia using automated-design fuzzy logic systems. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dang, Y.; Ding, S. Using a self-adaptive grey fractional weighted model to forecast Jiangsu’s electricity consumption in China. Energy 2020, 190, 116417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, X.; Gong, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhong, X. Holt–Winters smoothing enhanced by fruit fly optimization algorithm to forecast monthly electricity consumption. Energy 2020, 193, 116779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengying, H.; Jiandong, D.; Zequan, H.; Peng, W.; Shuai, F.; Peijia, H.; Chaoyuan, F. Monthly Electricity Forecast Based on Electricity Consumption Characteristics Analysis and Multiple Effect Factors. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th International Conference on Advanced Power System Automation and Protection (APAP), Xi’an, China, 21–24 October 2019; pp. 1814–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğcu, G.; Demirel, O.F.; Zaim, S. Forecasting Electricity Consumption with Neural Networks and Support Vector Regression. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Chiroma, H.; Imran, M.; Khan, A.; Bangash, J.I.; Asim, M.; Hamza, M.F.; Aljuaid, H. Forecasting electricity consumption based on machine learning to improve performance: A case study for the organization of petroleum exporting countries (OPEC). Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 86, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaytez, F.; Taplamacioglu, M.C.; Cam, E.; Hardalac, F. Forecasting electricity consumption: A comparison of regression analysis, neural networks and least squares support vector machines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2015, 67, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Alshibani, A.; Alshamrani, O.; Hassanain, M. A regression-based model for estimating the energy consumption of school facilities in Saudi Arabia. Energy Build. 2021, 237, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garni, A.Z.; Zubair, S.M.; Nizami, J.S. A regression model for electric-energy-consumption forecasting in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Energy 1994, 19, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanbar, M.; Alfarraj, A.; Alghieth, M. Energy Consumption Prediction Using Deep Learning Technique case study of computer college. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, R.; Al-Garni, A.; Al-Nassar, Y. Modelling and forecasting monthly electric energy consumption in eastern Saudi Arabia using abductive networks. Energy 1997, 22, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, R.; Al-Garni, A. Forecasting monthly electric energy consumption in eastern Saudi Arabia using univariate time-series analysis. Energy 1997, 22, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikayilov, J.I.; Darandary, A.; Alyamani, R.; Hasanov, F.J.; Alatawi, H. Regional heterogeneous drivers of electricity demand in Saudi Arabia: Modeling regional residential electricity demand. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhraijah, M.; Alowaifeer, M.; Alsaleh, M.; Alfaris, A.; Molzahn, D.K. The Effects of Social Distancing on Electricity Demand Considering Temperature Dependency. Energies 2021, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, F.R.; Csala, D. A Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with Exogenous Factors (SARIMAX) Forecasting Model-Based Time Series Approach. Inventions 2022, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.S.E.; Ahmed, F.; Durani, F.; Bojnec, Š.; Ghareeb, M.M. Predicting Electricity Consumption in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Energies 2023, 16, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhaini, S.H.; Sultana, N. Forecasting Long-Term Electricity Consumption in Saudi Arabia Based on Statistical and Machine Learning Algorithms to Enhance Electric Power Supply Management. Energies 2023, 16, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, J.G.; Trigg, L.E. K*: An Instance-based Learner Using an Entropic Distance Measure. In Machine Learning Proceedings 1995, Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Machine Learning, Tahoe City, CA, USA, 9–12 July 1995; Elsevier: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1995; pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Aljazzar, H.; Leue, S. K⁎: A heuristic search algorithm for finding the k shortest paths. Artif. Intell. 2011, 175, 2129–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.; Kohavi, R. Empirical comparison of voting classification algorithms: Bagging, boosting, and variants. Mach. Learn. 1999, 36, 105–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weka 3: Machine Learning Software in Java. 2019. Available online: https://www.cs.waikato.ac.nz/ml/weka/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Al Metrik, M.A.; Musleh, D.A. Machine Learning Empowered Electricity Consumption Prediction. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 1427–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissey, S.; Jacques, S.; Le Bunetel, J.-C. The Fuzzy Logic Method to Efficiently Optimize Electricity Consumption in Individual Housing. Energies 2017, 10, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).