Abstract

The mercapturate pathway is a unique metabolic circuitry that detoxifies electrophiles upon adducts formation with glutathione. Since its discovery over a century ago, most of the knowledge on the mercapturate pathway has been provided from biomonitoring studies on environmental exposure to toxicants. However, the mercapturate pathway-related metabolites that is formed in humans—the mercapturomic profile—in health and disease is yet to be established. In this paper, we put forward the hypothesis that these metabolites are key pathophysiologic factors behind the onset and development of non-communicable chronic inflammatory diseases. This review goes from the evidence in the formation of endogenous metabolites undergoing the mercapturate pathway to the methodologies for their assessment and their association with cancer and respiratory, neurologic and cardiometabolic diseases.

1. Brief Overview of the Mercapturate Pathway

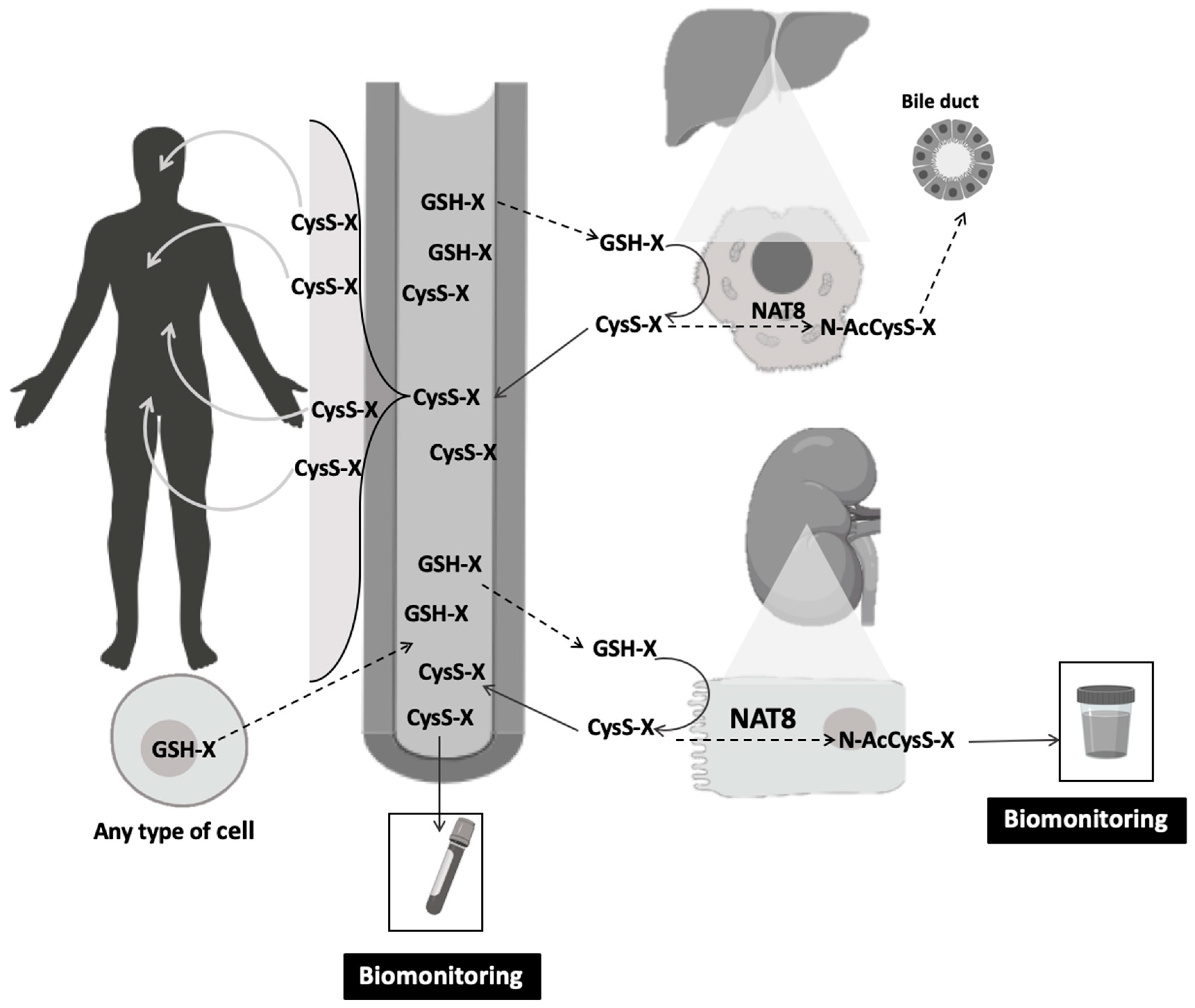

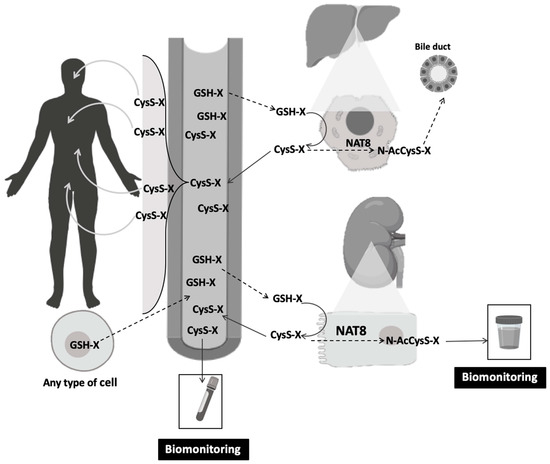

The mercapturate pathway is one of the key traits of renal proximal tubular cells, although it is also present in hepatocytes [1]. The main function of this pathway is to detoxify electrophilic species [2]. These electrophiles might arise either from the metabolism of endogenous substances or from exogenous compounds (or their biotransformation products) present in air, food or water [3,4,5,6,7]. Once generated in any cell and upon conjugation with glutathione (GSH) (Figure 1), an electrophile-GSH-S-conjugate is formed [8]. As cells are not able to metabolize these conjugates intracellularly, those conjugates are effluxed into the bloodstream to undergo the mercapturate pathway. Thus GSH-S-conjugates are the precursors that will generate mercapturates, through the three sequential steps that constitute this pathway. The first two steps are extracellular and generate cysteinyl-glycine-S-conjugates (CysGly-S-conjugates) and cysteine-S-conjugates (Cys-S-conjugates) by the membrane-bound-enzymes, gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT) and dipeptidase or aminopeptidase-M, respectively [9,10,11]. Despite their presence in tissues such as liver, small intestine, lung, brain, spleen and pancreas, the main local of expression of these enzymes is the kidney tubule [12]. The Cys-S-conjugates enter the renal tubular cells and hepatocytes via various transporters including organic anion transport polypeptides and cystine/cysteine transporters for the last reaction of the mercapturate pathway [12,13,14]. The last step of this pathway relies on the microsomal N-acetyl-transferase 8 (NAT-8) that is expressed almost exclusively in the kidney proximal tubular cells, with much lower presence at the liver [1]. An N-acetyl-cysteine-S-conjugate, also known as a mercapturate, is lately formed upon NAT8 activity and is majorly eliminated in urine.

Figure 1.

The mercapturomic profile of health and non-communicable chronic diseases. Any cell can generate GSH-S-conjugates that are excreted into the circulation and metabolized at the external apical membrane of kidney proximal tubular cells (major route) and hepatocytes (minor route). The Cys-S-conjugates that are formed might be subsequently detoxified by the N-acetyl-transferase NAT8, allowing the formation of mercapturates that are eliminated in urine. The Cys-S-conjugates can also be reabsorbed into the bloodstream and distributed into several organs. Blood and urine can be used for biomonitoring of mercapturate pathway-related metabolites. CysS-X: cysteine-S-conjugates; GSH-X: glutathione-S-conjugates; N-AcCysS-X: mercapturates; NAT8: N-acetyl-transferase 8.

2. The Mercapturomic Profile

The metabolites that are formed through this pathway include the precursors GSH-S-conjugates and their catabolic products, the CysGly-S-conjugates and Cys-S-conjugates, and finally their mercapturates. This mercapturate pathway-related metabolites is herein called the mercapturomic profile. As Cys-S-conjugates seem to have significantly higher half-life than their precursors [4,15], they are the plausible ones to be used for biomonitoring purposes in human biological fluids (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). In addition, the urinary mercapturates represent a prominent non-invasive approach to profile this pathway.

Table 1.

Mercapturomic profile of respiratory diseases.

Table 2.

Mercapturomic profile of cancer.

Table 3.

Mercapturomic profile of neurologic diseases.

Table 4.

Mercapturomic profile of cardiometabolic diseases.

Table 5.

Methodologies for mercapturomic profiling.

3. Biological Actions of Mercapturate Pathway-Related Metabolites

The effects of Cys-S-conjugates might have been underestimated, probably because the mercapturate pathway has been classically considered a detoxification route for xenobiotics. However, it is for instance known that the Cys-S-conjugate of cisplatin is more toxic to kidney tubular cells than cisplatin by itself [16]. Additionally, the Cys-S-conjugate of paracetamol is related to its nephrotoxicity, but not to its hepatotoxicity [17].

Cys-S-conjugates have been associated with hemodynamic properties [18], such as arteriolar vasoconstriction [19,20,21] and enhanced postcapillary venules permeability [22]. Cys-S-conjugates are involved in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [23] and might have pro-inflammatory [5], cytotoxic [16,17,24,25], genotoxic [25] and immunogenic [26] properties. Most of available studies have investigated the role of specific mercapturate pathway related metabolites in an experimental model or in a particular group of patients. Thus far, no work has given a comprehensive view of the mercapturomic profile, similarly to what it is performed for protein adducts [27]. In fact, Wang and Ballatori (1998) have brilliantly reviewed dozens of compounds that generate GSH-S-conjugates [28] such as leukotrienes [3], prostaglandins [29] and lipid peroxidation products [6,7].

The cysteinyl-leukotrienes (CysLTs) might be the best described example in the literature, concerning its association with non-communicable diseases. CysLTs are products of arachidonic acid metabolism and key mediators of inflammatory conditions [30,31,32] and stem from the catabolism of leukotriene C4 (LTC4), which is a GSH-S-conjugate. Extracellular LTC4 undergoes a two-step catabolic process originating the CysGly-S-conjugate (leukotriene D4, LTD4) and Cys-S-conjugate (leukotriene E4, LTE4) respectively, through the mercapturate pathway [31,32]. These compounds are generally termed CysLTs, although this denomination fully suits only LTE4, which has the longest half-life [15]. LTE4 mercapturate formation is mediated by NAT8 activity as described by the team of Veiga da Cunha (2010) [3]. CysTL are well known for their role in the pathophysiology of asthma and increasing evidence links these metabolites with non-communicable chronic inflammatory conditions [33,34], namely cardiovascular, neurologic and kidney disease [35] and cancer [36,37]. Altogether, non-communicable diseases represent the most common cause of death and multi-morbidity in the modern world [38]. Expanding investigations have shown that many of these diseases share pathophysiological mechanisms, with a similar profile of molecular changes, despite affecting diverse organs and systems differently. To fulfil this concept in a mercapturate pathway-related perspective, we herein review the available knowledge about the association between mercapturate pathway-related metabolites and the major non-communicable diseases. All included reports are clinical studies.

4. The Human Mercapturomic Profile in Health and Disease

4.1. Respiratory Diseases

CysLTs are important inflammatory mediators in the pathophysiology of respiratory disorders (Table 1) [39,40,41,42]. They are potent bronchoconstrictors and can cause acute and chronic structural defects in the airways [43,44,45]. Common treatment of asthma might include CysLTs receptor type 1 antagonists. There are also inhibitors available for 5-lypoxygenase, the enzyme involved in the synthesis of the precursor of CysLT from arachidonic acid. Three studies evaluated CysLTs in saliva, exhaled breath condensate and urine samples of patients with asthma (Table 1). Both chronic and acute asthma were associated with increased levels of LTE4 in all the biological matrixes analyzed [40,46,47]. Moreover, smoking habits did not affect LTE4 levels in exhaled breath condensate and the use of CysLTs receptor antagonists during asthma exacerbation did not affect LTE4 levels in urine [40]. Cys-S-conjugates which are disulfides were increased in children with difficult-to-treat asthma [34] and associated with asthma severity, including poorer control of symptomatology, greater medication use and a worse response to glucocorticoid therapy [48].

CysLTs have also been associated to silica-induced lung fibrogenesis [49]. In fact, increased LTE4 levels were observed in exhaled breath condensate of patients with pneumoconiosis derived from asbestos and silica exposure [39].

4.2. Cancer

Cys-S-conjugates have also been described in different types of cancer, namely in melanoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, breast, ovarian and thyroid cancer (Table 2).

Melanoma was linked to the melanin metabolite 5-S-Cys-DOPA (Cys-DOPA). In melanocytes, the amino acid L-DOPA is oxidized into a highly reactive dopaquinone that after binding to a sulfhydryl donor as glutathione is further oxidized to pheomelanin, a yellow to reddish form of melanin. Increases in serum Cys-DOPA have been associated with poor prognosis of malignant melanoma and shorter survival times [50,51,52,53,54]. Additionally, Cys-DOPA also increased in melanoma recurrence after chemotherapy or surgery [50,53,54].

Estrogen metabolism is strongly implicated in the development of hormonal cancers [55,56,57]. Estrogen metabolites, namely 2- and 4-hydroxyestrone and 2- and 4-hydroxyestradiol might generate electrophilic metabolites, and for mercapturate pathway-related metabolites their urinary levels were found to be decreased in patients with breast cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma relative to healthy subjects [58,59,60]. Additionally, the ratio of depurinating estrogen deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) adducts to estrogen metabolites and conjugates (including GSH-S-conjugates, Cys-S-conjugates and mercapturates) was higher in cases of thyroid and ovarian cancer in comparison with healthy individuals [56,57]. Changes in Cys-S-conjugates that are disulfides were also observed in leukemia, lymphoma and colorectal adenoma [61,62].

4.3. Neurologic Diseases

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by severe depletion of dopamine (DA) [63]. The role of dopamine related cysteinyl-S-conjugates in PD has been investigated in order to evaluate how the failure of anti-oxidative mechanisms, in the prevention of spontaneous dopamine oxidation, might contribute the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons (Table 3).

Dopamine can be oxidized following non-enzymatic and enzymatic pathways. Dopamine can spontaneously oxidize to dopamine-o-quinone, which forms conjugates GSH-S-conjugates. Dopamine can also be oxidized by monoamine oxidase to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, which is further metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase to 3,4-dihydrophenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and then into homovanillic acid upon catechol-O-methyltransferase activity [64,65].

In 1989, Fornstedt and colleagues [66] identified 5-Cys-S-conjugates of DOPA, DA and DOPAC in three brain regions (substantia nigra, putamen and caudate nucleus) of post-mortem brains from patients with and without depigmentation and neuronal loss within the substantia nigra. The levels of DOPA, DA and DOPAC were decreased in the depigmented group.

Additionally, while no differences were found for the Cys-S-conjugates, the authors observed an increase in the ratio of Cys-DA/DA and Cys-DOPAC/DOPAC in the substantia nigra and Cys-DOPA/DOPA in the putamen of the depigmented group [66]. Similar results were later obtained with patients with PD and parkinsonism (PD and multiple system atrophy parkinsonism). Importantly, patients were not on DOPA therapy. The levels of Cys-DA were not affected in patients with parkinsonism. Nevertheless, as DOPAC or homovanillic acid were decreased, both Cys-DA/DOPAC or Cys-DA/homovanillic acid ratios were increased in these patients [67,68]. The work of Goldstein and co-authors [67] also showed that Cys-DA and DOPAC have the same source: the cytoplasmic dopamine. Thus, the dopamine denervation associated with parkinsonism would be expected to produce equal proportional decreases in Cys-DA and DOPAC levels and consequently unchanged Cys-DA/DOPAC ratios. The authors were not able to explain the observed decrease in DOPAC without the decrease in Cys-DA [67]. Even though, the authors suggested that this might be due to decreased antioxidant capacity [69] and aldehyde dehydrogenase activity [70]. Interestingly, substantia nigra of PD patients has a 50% reduction of their GSH levels [71,72]. This decrease can be presumably due to the reaction of GSH with DA semiquinones or quinones [73]. At the same time, decreased antioxidant capacity might shift the balance from dopamine to dopamine quinone and finally to Cys-DA, which will explain the absence of decreased levels Cys-DA. In opposition, there is one study reporting increased levels of 5-S-Cys-conjugates of DOPA, DA and DOPAC at substantia nigra of patients with PD. However, all patients were under L-DOPA treatment, which could have influenced the results [74].

Catechol estrogens are also present in the brain and, like dopamine, can be bioactivated to catechol quinones able to form adducts with GSH and undergo the mercapturate pathway for elimination. Urinary estrogen-catechol Cys-S-conjugates were lower and estrogen-DNA adducts were higher in PD patients than in healthy controls [75]. The authors suggested that there is an unbalanced estrogen metabolism in PD and that the protective pathways might be unable to avoid the oxidation of catechol estrogens and further DNA adducts formation.

On the other hand, neuro-inflammation might also play a role in autism [76,77]. The levels of CysLTs have been investigated in autistic children, together with a sensitive indicator of bioactive products of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, the 8-isoprostane [78,79]. The authors proposed both CysLTs and 8-isoprostane as markers for early recognition of sensory dysfunction in autistic patients that might facilitate earlier interventions [78].

CysLTs increases at the central nervous system [80,81,82], might also be involved in edema formation in brain tumor patients [83].

4.4. Cardiometabolic Diseases

There are several works reporting the association of CysLTs in cardiometabolic diseases (Table 4) and different mechanisms might explain this association. For instance, in cardiometabolic diseases, the 5-lipoxygenase pathway that contributes to CysLTs formation is activated, the CysLTs receptors (mainly CysLT2R) are strongly expressed in cardiac, endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. CysLTs exert negative inotropic action on the myocardium and mediate coronary vasoconstriction [84]. Moreover, CysLTs may have pro-atherogenic effects; they may stimulate proliferation and migration of arterial smooth muscle cells and platelet activation [36].

Winking and collaborators (1998) measured urinary LTs in patients suffering from spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Urinary LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 levels were positively associated with hematoma volume and decreased after hematoma removal by surgery [85].

Regarding coronary artery diseases, urinary LTE4 levels were increased in patients admitted in the hospital with acute chest pain derived from acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina compared with controls [86]. Likewise, urinary LTE4 levels were higher in patients with chronic stable angina than controls before surgery [87]. In another study, urine and plasma levels of CysLTs increased during, and after, cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Interestingly, that increment was greater in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than in patients without this condition [88]. The authors hypothesize that these differences may be related to neutrophil activation and higher lung and airway production of CysLTs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

CysTL were also evaluated in individuals with atherosclerosis lesions in the carotid artery concomitantly with or without periodontal disease. This study was motivated by several reports that have been associating periodontal disease with the development of early atherosclerosis and increased risk of myocardial infarction [89,90,91]. The sum of LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 was increased in gingival crevicular fluid in subjects with higher dental plaque and also in subjects with atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid artery, regardless of periodontal status [92].

CysLTs might play a role in the development of the cardiovascular complications associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Urinary LTE4 levels were associated with obesity and hypoxia severity in patients diagnosed with OSA. Continuous positive air treatment decreased LTE4 by 22% only in OSA patients with normal body max index (BMI). Additionally, LTE4 levels were higher in non-obese OSA patients vs. matched controls [93]. In another study, Gautier-Veyret and co-authors (2018) found that urinary LTE4 levels were independently associated with age, history of cardiovascular events and severity of hypoxia in patients with OSA with and without previous cardiovascular events. As such, LTE4 levels were higher in OSA patients with no previous cardiovascular events than in controls with no previous cardiovascular events. Urinary LTE4 levels were also associated with intima-media thickness, suggesting the activation of CysLTs pathway as a driver of vascular remodeling in OSA [94].

CysLTs were also evaluated in patients with diabetes. Urinary LTE4 levels were higher in patients with type 1 diabetes than in controls [95] and decreased 32% after intensive insulin treatment [96]. These results suggest that hyperglycemia activates arachidonic acid metabolism and consequent CysLTs formation. Interestingly, glucose can also generate Cys-S-conjugates that are far more stable than glucose-GSH. In specific, higher urinary levels of glucose-Cys were detected in patients with diabetes [4].

Cys-S-conjugates that are disulfides were related with hypertension, diabetes and Framingham risk score in coronary heart disease patient [97,98] as well as impaired microvascular function and greater epicardial necrotic core [97]. Moreover, these conjugates and GSH-Cys-S-conjugates were independent predictors of endothelium-dependent vasodilation [97].

5. Methods in Mercapturates Profiling

Mercapturate pathway-related metabolites and their profile might be useful as biomarkers in characterizing human exposure to electrophilic endogenous substrates and its relation to health and disease. The methodological strategies herein reviewed for the determination of mercapturate pathway-related metabolites are presented in Table 5. These compounds have been measured in different human fluids and tissues requiring pre-treatment of samples. The studies herein reviewed quantify only one type or family of mercapturate pathway-related metabolites (dopamine, estrogens, cysteinyl-leukotrienes and cysteinyl-S-conjugates which are disulfides). Those metabolites were quantified by different methodologies including liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detector or fluorescence detector or mass spectrometry detector, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and radioimmunoassay (Table 5).

6. Trends and Limitations

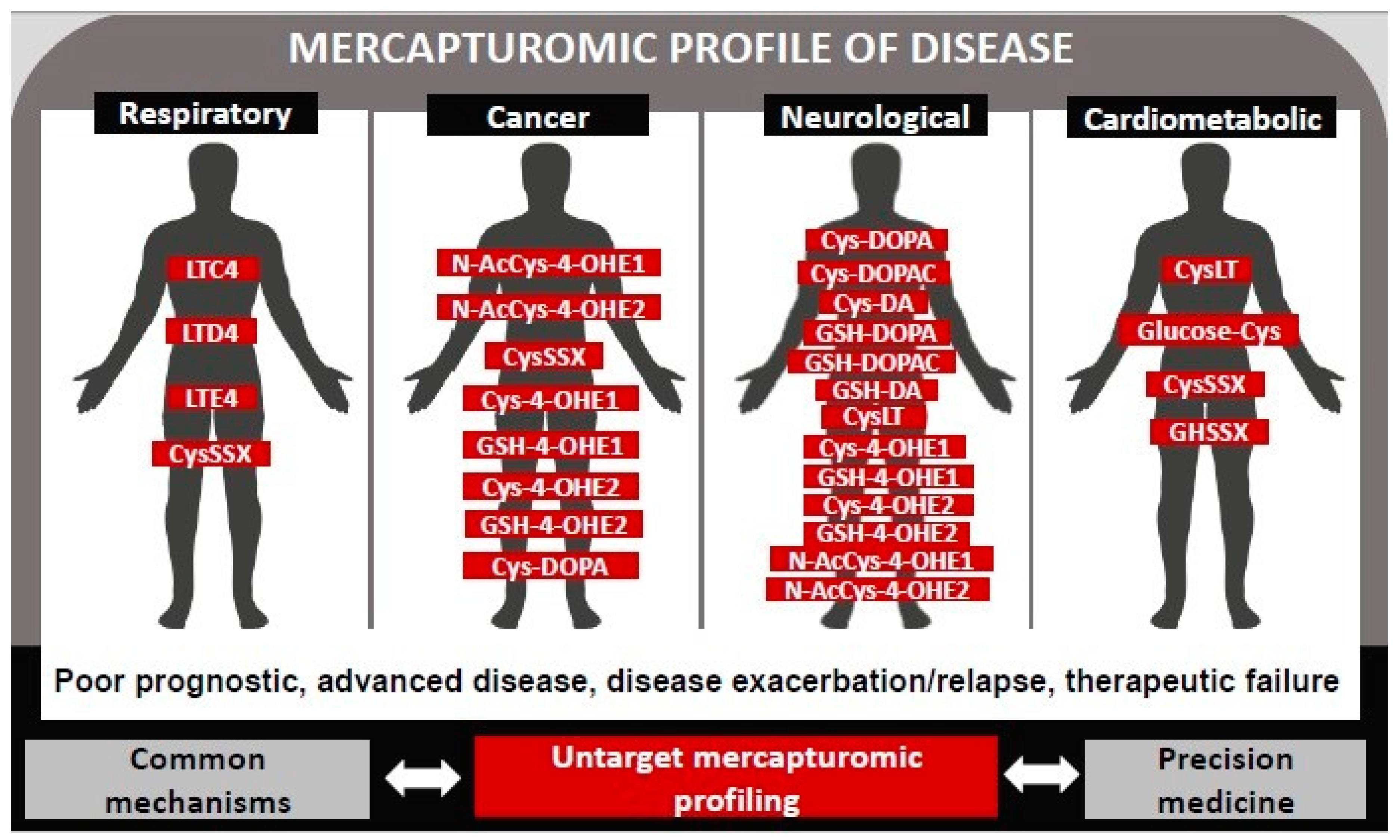

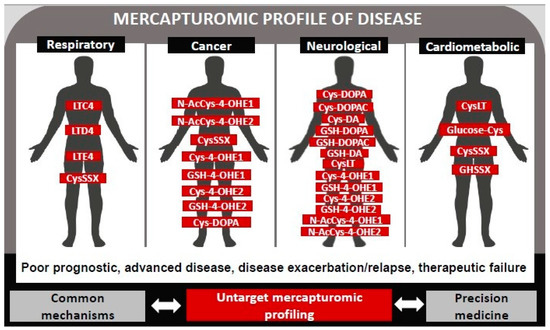

Herein we review the clinical studies that reported associations between, one of or a family of, mercapturate pathway-related metabolites with a particular disease. In fact, most of available evidence on the association of the mercapturomic profile with health and disease has been obtained by a targeted approach (Figure 2). Future work might focus on a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis of the totality of mercapturate-pathway related metabolites, in similarity to what has been done for protein addutomics [104].

Figure 2.

Mercapturomic profile of disease. This profile was defined by reviewing the mercapturate-pathway related metabolites that have already been associated with non-communicable diseases (prognostic, progression, therapeutic response) in clinical studies.

One of the main limitations to assess the global mercapturomic profile is the fact that the mercapturate pathway-related metabolites are often minor metabolites [105]. Despite the enormous technological advances in MS instrumentation, the identification of this minor adducts is still challenging. New approaches are needed for providing accuracy and sensitivity along with quantitative information. The future obstacles will involve not only sample pre-treatment procedures, but also optimization of MS and data analysis strategies.

On the other hand, in vivo models of disease will allow to investigate the origin and metabolism of these compounds as well as their distribution in the body. In fact, these compounds have been described to be found in several matrices, including tissues, urine, plasma, exhaled breath condensate, saliva, polymorphic blood mononuclear cells or gingival crevicular fluid that might require different pre-treatment procedures.

7. Innovative Potential

Many chronic diseases with an inflammatory component display significantly increased levels of electrophiles. The mercapturomic profile might represent a useful tool to globally characterize both environmental and internal electrophile exposomes and its relation to disease (Figure 2). This holistic omic-approach is expected to provide unique information that includes the identification of new therapeutic targets and commonalities related to mechanisms of different diseases that might facilitate therapeutics development and define preventive strategies. Additionally, this approach might constitute an effective tool to define the mercapturomic phenotypes of drug resistance and adverse reactions; disease progression, encouraging precision medicine standards. Finally, as many environmental compounds undergo this pathway it will also contribute to a better understanding of the contribution of environment to non-communicable diseases.

Author Contributions

S.A.P. projected the paper. C.G.-D., J.M., V.S., M.J.C., N.R.C., S.A.P. wrote the manuscript and prepared figures. A.M.M.A. and E.C.M. assisted with the writing and gave expert advice regarding the topic.

Funding

iNOVA4Health–UID/Multi/04462/2013, a program financially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia/Ministério da Educação e Ciência, through national funds and co-funded by FEDER under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement is acknowledged (Ref: 201601-02-021). Authors supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT–Portugal): for V.S.; PD/BD/105892/2014 for C.G.-D.; RNEM-LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022125022125 for J.M.; SFRH/BD/130911/2017 for M.J.C.; PD/BD/114257/2016 for N.R.C.; Programa Operacional Potencial Humano and the European Social Fund (IF/01091/2013) for A.M.M.A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests

References

- Chambers, J.C.; Zhang, W.; Lord, G.M.; van der Harst, P.; Lawlor, D.A.; Sehmi, J.S.; Gale, D.P.; Wass, M.N.; Ahmadi, K.R.; Bakker, S.J.L.; et al. Genetic loci influencing kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veiga-da-Cunha, M.; Tyteca, D.; Stroobant, V.; Courtoy, P.J.; Opperdoes, F.R.; Van Schaftingen, E. Molecular identification of NAT8 as the enzyme that acetylates cysteine S-conjugates to mercapturic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 18888–18898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwergold, B.S. α-Thiolamines such as cysteine and cysteamine act as effective transglycating agents due to formation of irreversible thiazolidine derivatives. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 66, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnay, J.L.; Tong, J.; Drangova, R.; Baines, A.D. Production of cysteinyl-dopamine during intravenous dopamine therapy. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntimbane, T.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Huot, C.; Legault, L.; Jacob, S.V.; Brunet, S.; Levy, E.; Guéraud, F.; Lands, L.C.; Comte, B. Oxidative stress and cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: A pilot study in children. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2008, 7, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroe, A.G.; Attanasio, R.; Scinicariello, F. Acrolein metabolites, diabetes and insulin resistance. Environ. Res. 2016, 148, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatori, N.; Krance, S.M.; Notenboom, S.; Shi, S.; Tieu, K.; Hammond, C.L. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol. Chem. 2009, 390, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughey, R.P.; Rankin, B.B.; Elce, J.S.; Curthoys, N.P. Specificity of a particulate rat renal peptidase and its localization along with other enzymes of mercapturic acid synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1978, 186, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, O.W. The role of glutathione turnover in the apparent renal secretion of cystine. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 2263–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Hanigan, M.H. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase, a glutathionase: Its expression and function in carcinogenesis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1998, 111, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commandeur, J.N.; Stijntjes, G.J.; Vermeulen, N.P. Enzymes and transport systems involved in the formation and disposition of glutathione S-conjugates. Role in bioactivation and detoxication mechanisms of xenobiotics. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995, 47, 271–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchman, C.A.; Rebbeor, J.F.; Ballatori, N. Efficient hepatic uptake and concentrative biliary excretion of a mercapturic acid. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 1998, 275, G612–G619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, N.; Redstone, G.G.J.; Dahabieh, M.S.; Nichol, J.N.; del Rincon, S.V.; Gu, Y.; Bohle, D.S.; Sun, Y.; Conklin, D.S.; Mann, K.K. The novel arsenical darinaparsin is transported by cystine importing systems. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 85, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaoka, Y.; Boyce, J.A. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors; emerging concepts. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2014, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, D.M.; Deng, M.; Zhang, L.; Lapus, M.G.; Hanigan, M.H. Metabolism of cisplatin to a nephrotoxin in proximal tubule cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.T.; Bruno, M.K.; Horton, R.A.; Hill, D.W.; Roberts, J.C.; Cohen, S.D. Contribution of acetaminophen-cysteine to acetaminophen nephrotoxicity II. Possible involvement of the γ-glutamyl cycle. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 202, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.A.; Austen, K.F. The biologically active leukotrienes. Biosynthesis, metabolism, receptors, functions, and pharmacology. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.; Pace-Asciak, C.R. Potent vasoconstriction of the isolated perfused rat kidney by leukotrienes C4 and D4. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1983, 61, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, K.F.; Brenner, B.M.; Ichikawa, I. Effects of leukotriene D4 on glomerular dynamics in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1987, 253, F239–F243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastri, S.; McNeill, J.R.; Wilson, T.W.; Poduri, R.; Kaul, C.; Gopalakrishnan, V. Cysteinyl leukotrienes mediate enhanced vasoconstriction to angiotensin II but not endothelin-1 in SHR. Am. J. Physiol. Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2001, 281, H342–H349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, W.; Kuo, C.G.; Qureshi, R.; Jakschik, B.A. Role of leukotrienes in vascular changes in the rat mesentery and skin in anaphylaxis. J. Immunol. 1988, 140, 2361–2368. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Jiang, J.; Jing, Z.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Deng, B. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Cell. Signal. 2018, 46, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, S.T.; Bruno, M.K.; Hennig, G.E.; Horton, R.A.; Roberts, J.C.; Cohen, S.D. Contribution of acetaminophen-cysteine to acetaminophen nephrotoxicity in CD-1 mice: I. Enhancement of acetaminophen nephrotoxicity by acetaminophen-cysteine. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 202, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvash, E.; Har-Tal, M.; Barak, S.; Meir, O.; Rubinstein, M. Leukotriene C4 is the major trigger of stress-induced oxidative DNA damage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salauze, L.; van der Velden, C.; Lagroye, I.; Veyret, B.; Geffard, M. Circulating antibodies to cysteinyl catecholamines in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease patients. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2005, 6, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, H.; Rappaport, S.M.; Törnqvist, M. Protein adductomics: Methodologies for untargeted screening of adducts to serum albumin and hemoglobin in human blood samples. High-Throughput 2019, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ballatori, N. Endogenous glutathione conjugates: Occurrence and biological functions. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998, 50, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christ-Hazelhof, E.; Nugteren, D.H.; Van Dorp, D.A. Conversions of prostaglandin endoperoxides by glutathione-S-transferases and serum albumins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 1976, 450, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.D. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: Advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeggström, J.Z.; Funk, C.D. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: Biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5866–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, A.; Haeggström, J.Z. The leukotrienes: Immune-modulating lipid mediators of disease. Adv. Immunol. 2012, 116, 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, V.; Thompson, M.D.; Sala, A.; Cole, D.E.; Folco, G.; Rovati, G.E. Cysteinyl-leukotrienes and their receptors in asthma and other inflammatory diseases: Critical update and emerging trends. Med. Res. Rev. 2007, 27, 469–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Dias, C.; Morello, J.; Correia, M.; Coelho, N.; Antunes, A.M.M.; Macedo, M.P.; Monteiro, E.C.; Soto, K.; Pereira, S.A. Mercapturate pathway in the tubulocentric perspective of diabetic kidney disease. Nephron 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, M.; Dvash, E. Leukotrienes and kidney diseases. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2018, 27, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelosa, P.; Colazzo, F.; Tremoli, E.; Sironi, L.; Castiglioni, L. Cysteinyl leukotrienes as potential pharmacological targets for cerebral diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3454212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, L.; Butler, C.T.; Murphy, A.; Moran, B.; Gallagher, W.M.; O’Sullivan, J.; Kennedy, B.N. Evaluation of cysteinyl leukotriene signaling as a therapeutic target for colorectal cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Pelclová, D.; Fenclova, Z.; Vlcková, Š.; Lebedová, J.; Syslova, K.; Pecha, O.; Belacek, J.; Navrátil, T.; Kuzma, M.; Kacer, P. Leukotrienes B4, C4, D4 and E4 in the exhaled breath condensate (EBC), blood and urine in patients with pneumoconiosis. Ind. Health 2012, 50, 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, D.; Doruk, S.; Koseoglu, H.I.; Sahin, S.; Celikel, S.; Erkorkmaz, U. Cysteinyl leukotrienes in exhaled breath condensate of smoking asthmatics. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennergren, G. Inflammatory mediators in blood and urine. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2000, 1, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaki, E.; Papatheodorou, G.; Ischaki, E.; Grammenou, V.; Papa, I.; Loukides, S. Leukotriene E4 in urine in patients with asthma and COPD-The effect of smoking habit. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, T.M.; Boyce, J.A. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptors, old and new; implications for asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, P. LC/MS/MS analysis of leukotriene B4 and other eicosanoids in exhaled breath condensate for assessing lung inflammation. J. Chromatogr. B 2009, 877, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, P. Leukotrienes, antileukotrienes and asthma. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.A.; Malice, M.P.; Tanaka, W.; Tozzi, C.A.; Reiss, T.F. Increase in urinary leukotriene LTE4levels in acute asthma: Correlation with airflow limitation. Thorax 2004, 59, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, E.; Taniguchi, M.; Higashi, N.; Mita, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tatsuno, S.; Fukutomi, Y.; Tanimoto, H.; Sekiya, K.; Oshikata, C. Increase in salivary cysteinyl-leukotriene concentration in patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. Allergol. Int. 2011, 60, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, S.T.; Brown, L.A.S.; Helms, M.N.; Qu, H.; Brown, S.D.; Brown, M.R.; Fitzpatrick, A.M. Cysteine oxidation impairs systemic glucocorticoid responsiveness in children with difficult-to-treat asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimbori, C.; Shiota, N.; Okunishi, H. Involvement of leukotrienes in the pathogenesis of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Exp. Lung Res. 2010, 36, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, I.; Meyer, J.C.; Seifert, B.; Dummer, R.; Flace, A.; Burg, G. Prognostic value of serum 5-S-cysteinyldopa for monitoring human metastatic melanoma during immunochemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 5073–5076. [Google Scholar]

- Banfalvi, T.; Gilde, K.; Boldizsar, M.; Fejös, Z.; Horvath, B.; Liszkay, G.; Beczassy, E.; Kremmer, T. Serum concentration of 5-S-cysteinyldopa in patients with melanoma. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 30, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Kageshita, T.; Furue, M.; Hatta, N.; Kiyohara, Y.; Nakayama, J.; Ono, T.; Saida, T.; Takata, M.; Tsuchida, T. Evaluation of 5-S-cysteinyldopa as a marker of melanoma progression: 10 years’ experience. Melanoma Res. 2002, 12, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Aoki, T.; Umezu, K.; Mori, M.; Hayashi, M.; Saito, H.; Kitamura, K.; Tsuchida, A.; Koyanagi, Y.; Yamagishi, T. Rectal malignant melanoma diagnosed by N-isopropyl-p-123I-iodoamphetamine single photon emission computed tomography and 5-S-cysteinyl dopa: Report of a case. Surg. Today 2003, 33, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, H.; Yamasaki, O.; Kaji, T.; Otsuka, M.; Asagoe, K.; Takata, M.; Iwatsuki, K. Usefulness of serum 5-S-cysteinyl-dopa as a biomarker for predicting prognosis and detecting relapse in patients with advanced stage malignant melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F.; Dunfield, L.; Phillips, K.P.; Krewski, D.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Risk factors for ovarian cancer: An overview with emphasis on hormonal factors. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part B Crit. Rev. 2008, 11, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Beseler, C.L.; Hall, J.B.; LeVan, T.; Cavalieri, E.L.; Rogan, E.G. Unbalanced estrogen metabolism in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Goldner, W.; Beseler, C.L.; Rogan, E.G.; Cavalieri, E.L. Unbalanced estrogen metabolism in thyroid cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 2642–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, N.W.; Yang, L.; Muti, P.; Meza, J.L.; Pruthi, S.; Ingle, J.N.; Rogan, E.G.; Cavalieri, E.L. The molecular etiology of breast cancer: Evidence from biomarkers of risk. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1949–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, N.W.; Yang, L.; Pruthi, S.; Ingle, J.N.; Sandhu, N.; Rogan, E.G.; Cavalieri, E.L. Urine biomarkers of risk in the molecular etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2009, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, N.W.; Yang, L.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Vose, J.; Beseler, C.; Rogan, E.G.; Cavalieri, E.L. Urinary biomarkers suggest that estrogen-DNA adducts may play a role in the aetiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biomarkers 2009, 14, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, C.R.; Puckett, A.B.; Jones, D.P.; Griffith, D.P.; Szeszycki, E.E.; Bergman, G.F.; Furr, C.E.; Tyre, C.; Carlson, J.L.; Galloway, J.R. Plasma antioxidant status after high-dose chemotherapy: A randomized trial of parenteral nutrition in bone marrow transplantation patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.H.; Fedirko, V.; Jones, D.P.; Terry, P.D.; Bostick, R.M. Antioxidant micronutrients and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in colorectal adenoma patients: Results from a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2010, 19, 1055–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish, S.J.; Shannak, K.; Hornykiewicz, O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic parkinsons disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Jinsmaa, Y.; Sullivan, P.; Holmes, C.; Kopin, I.J.; Sharabi, Y. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol (hydroxytyrosol) mitigates the increase in spontaneous oxidation of dopamine during monoamine oxidase inhibition in PC12 cells. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 2173–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, M.C.; Adler, C.H. COMT inhibition. Neurology 1998, 50, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornstedt, B.; Brun, A.; Rosengren, E.; Carlsson, A. The apparent autoxidation rate of catechols in dopamine-rich regions of human brains increases with the degree of depigmentation of substantia nigra. J. Neural Transm. Dis. Dement. Sect. 1989, 1, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Holmes, C.; Sullivan, P.; Jinsmaa, Y.; Kopin, I.J.; Sharabi, Y. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid ratios of cysteinyl-dopamine/3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in parkinsonian synucleinopathies. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 31, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.-C.; Kuo, J.-S.; Chia, L.-G.; Dryhurst, G. Elevated 5-S-cysteinyldopamine/homovanillic acid ratio and reduced homovanillic acid in cerebrospinal fluid: Possible markers for and potential insights into the pathoetiology of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 1996, 103, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, A.; Fornstedt, B. Catechol metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid as possible markers in the early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1991, 41, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Sullivan, P.; Holmes, C.; Miller, G.W.; Alter, S.; Strong, R.; Mash, D.C.; Kopin, I.J.; Sharabi, Y. Determinants of buildup of the toxic dopamine metabolite DOPAL in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riederer, P.; Sofic, E.; Rausch, W.-D.; Schmidt, B.; Reynolds, G.P.; Jellinger, K.; Youdim, M.B.H. Transition metals, ferritin, glutathione, and ascorbic acid in parkinsonian brains. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, P.; Dexter, D.T.; Sian, J.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Marsden, C.D. Oxidative stress as a cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease and incidental lewy body disease. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 32, S82–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.P.E.; Jenner, P.; Halliwell, B. Superoxide-dependent depletion of reduced glutathione by L-DOPA and dopamine. Relevance to parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 1995, 6, 1480–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.P.E.; Jenner, P.; Daniel, S.E.; Lees, A.J.; Marsden, D.C.; Halliwell, B. Conjugates of catecholamines with cysteine and GSH in Parkinson’s disease: Possible mechanisms of formation involving reactive oxygen species. J. Neurochem. 1998, 71, 2112–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, N.W.; Murman, D.; Beseler, C.L.; Zahid, M.; Rogan, E.G.; Cavalieri, E.L. Imbalanced estrogen metabolism in the brain: Possible relevance to the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. Biomarkers 2011, 16, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.A.; Vargas, D.L.; Zimmerman, A.W. Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2005, 17, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chauhan, A.; Sheikh, A.M.; Patil, S.; Chauhan, V.; Li, X.M.; Ji, L.; Brown, T.; Malik, M. Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 207, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, H.; Al-Ayadhi, L.; El-Ansary, A. Cysteinyl leukotriene correlated with 8-isoprostane levels as predictive biomarkers for sensory dysfunction in autism. Lipids Health Dis. 2016, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, M.; Kot-Wasik, A.; Kot, J.; Namieśnik, J. Isoprostanes-biomarkers of lipid peroxidation: Their utility in evaluating oxidative stress and analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 4631–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmet, T.; Seregi, A.; Hertting, G. Formation of sulphidopeptide-leukotrienes in brain tissue of spontaneously convulsing gerbils. Neuropharmacology 1987, 26, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwak, K.J.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Levine, L. Leukotriene production in gerbil brain after ischemic insult, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and concussive injury. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 62, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, M.; Kiwak, K.; Hekimian, K.; Levine, L. Synthesis of compounds with properties of leukotrienes C4 and D4 in gerbil brains after ischemia and reperfusion. Science 2006, 224, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winking, M.; Lausberg, G.; Simmet, T. Malignancy-dependent formation of cysteinyl-leukotrienes in human brain tumor tissues and its detection in urine. In Neurosurgical Standards, Cerebral Aneurysms, Malignant Gliomas; Piscol, K., Klinger, M., Brock, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1992; Volume 20, pp. 334–335. [Google Scholar]

- Bittl, J.A.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Lewis, R.A.; Mehrotra, M.M.; Corey, E.J.; Austen, K.F. Mechanism of the negative inotropic action of leukotrienes C4 and D4 on isolated rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 1985, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winking, M.; Deinsberger, W.; Joedicke, A.; Boeker, D.K. Cysteinyl-leukotriene levels in intracerebral hemorrhage: An edema-promoting factor? Cerebrovasc. Dis. 1998, 8, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carry, M.; Korley, V.; Willerson, J.T.; Weigelt, L.; Ford-Hutchinson, A.W.; Tagari, P. Increased urinary leukotriene excretion in patients with cardiac ischemia: In vivo evidence for 5-lipoxygenase activation. Circulation 1992, 85, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.P.; Sampson, A.P.; Piper, P.J.; Chester, A.H.; Ohri, S.K.; Yacoub, M.H. Enhanced excretion of urinary leukotriene E4 in coronary artery disease and after coronary artery bypass surgery. Coron. Artery Dis. 1993, 4, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prost, N.; El-Karak, C.; Avila, M.; Ichinose, F.; Melo, M.F.V. Changes in cysteinyl leukotrienes during and after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söder, P.Ö.; Söder, B.; Nowak, J.; Jogestrand, T. Early carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with periodontal diseases. Stroke 2005, 36, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.J.; Becher, H.; Ziegler, C.M.; Lichy, C.; Buggle, F.; Kaiser, C.; Lutz, R.; Bültmann, S.; Preusch, M.; Dörfer, C.E. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004, 35, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, G.R.; Ohlsson, O.; Pettersson, T.; Renvert, S. Chronic periodontitis, a significant relationship with acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2003, 24, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, M.; Airila-Månsson, S.; Jogestrand, T.; Söder, B.; Söder, P.-Ö. Increased leukotriene concentrations in gingival crevicular fluid from subjects with periodontal disease and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2007, 193, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke-Labesque, F.; Bä, M.; Lefebvre, B.; Tamisier, R.; Baguet, J.-P.; Arnol, N.; Lé, P.; Pé, J.-L.; Grenoble, F.; Stockholm, S. Increased urinary leukotriene E4 excretion in obstructive sleep apnea: Effects of obesity and hypoxia. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier-Veyret, E.; Bäck, M.; Arnaud, C.; Belaïdi, E.; Tamisier, R.; Lévy, P.; Arnol, N.; Perrin, M.; Pépin, J.-L.; Stanke-Labesque, F. Cysteinyl-leukotriene pathway as a new therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis related to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, G.; Boizel, R.; Bessard, J.; Cracowski, J.L.; Bessard, G.; Halimi, S.; Stanke-Labesque, F. Urinary leukotriene E4 excretion is increased in type 1 diabetic patients: A quantification by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005, 78, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boizel, R.; Bruttmann, G.; Benhamou, P.Y.; Halimi, S.; Stanke-Labesque, F. Regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation by glycaemic control: Evidence for reversible activation of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway in type 1, but not in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2068–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.S.; Eshtehardi, P.; McDaniel, M.C.; Fike, L.V.; Jones, D.P.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Samady, H. The role of plasma aminothiols in the prediction of coronary microvascular dysfunction and plaque vulnerability. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, S.; Abramson, J.L.; Jones, D.P.; Rhodes, S.D.; Weintraub, W.S.; Hooper, W.C.; Vaccarino, V.; Harrison, D.G.; Quyyumi, A.A. The relationship between plasma levels of oxidized and reduced thiols and early atherosclerosis in healthy adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafnsson, A.; Bäck, M. Urinary leukotriene E4 is associated with renal function but not with endothelial function in type 2 diabetes. Dis. Mark. 2013, 35, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Improved HPLC determination of 5-S-cysteinyldopa in serum. Clin. Chem. 1994, 40, 495–496. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.P.; Carlson, J.L.; Mody, V.C.; Cai, J.; Lynn, M.J.; Sternberg, P. Redox state of glutathione in human plasma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, S.; Abramson, J.L.; Jones, D.P.; Rhodes, S.D.; Weintraub, W.S.; Hooper, W.C.; Vaccarino, V.; Alexander, R.W.; Harrison, D.G.; Quyyumi, A.A. Endothelial function and aminothiol biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy adults. Hypertension 2008, 52, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Ghasemzadeh, N.; Eapen, D.J.; Sher, S.; Arshad, S.; Ko, Y.; Veledar, E.; Samady, H.; Zafari, A.M.; Sperling, L. Novel biomarker of oxidative stress is associated with risk of death in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2016, 133, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, P.I.; B’Hymer, C. Mercapturic acids: Recent advances in their determination by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and their use in toxicant metabolism studies and in occupational and environmental exposure studies. Biomarkers 2016, 21, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.; Charneira, C.; Morello, J.; Rodrigues, J.; Pereira, S.A.; Antunes, A.M.M. Mass Spectrometry-Based Methodologies for Targeted and Untargeted Identification of Protein Covalent Adducts (Adductomics): Current status and challenges. High-Throughput 2019, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).