Abstract

Objective: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other forms of dementia are a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by progressive cognitive decline. Differential diagnosis between AD and other dementias is crucial for choosing the optimal treatment strategy. Currently, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis remains the most accurate diagnostic method, but its invasiveness limits its use. In this regard, the search for reliable biomarkers in the blood is an urgent task. Methods: The study included 31 dementia patients (23 women and 8 men) diagnosed via interdisciplinary consultations and neuropsychological testing (MMSE ≤ 24). CSF and blood plasma samples were collected and analyzed using Luminex technology. Biomarker concentrations were measured, and statistical analyses (ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis, and Pearson correlation) were performed to compare groups and assess correlations. Results: Levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in CSF were significantly lower in patients with AD compared with non-AD dementia (p = 0.02 and p < 0.001, respectively). The Aβ42/40 ratio in CSF was higher in patients with non-AD dementia (p = 0.048). The concentration of Aβ42 in blood plasma was increased in patients with AD (p = 0.001). Positive correlations were found between Aβ42 in CSF and TDP-43 in plasma in non-AD dementia (r = 0.97, p < 0.001), as well as between neurogranin and TDP-43 in plasma in AD (r = 0.845, p < 0.001). Conclusions: The study demonstrates the potential of blood biomarkers, in particular Aβ42, for the differential diagnosis of AD and other forms of dementia. The discovered correlations between CSF and plasma biomarkers deepen the understanding of neurodegenerative processes and contribute to the development of noninvasive diagnostic methods.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other forms of dementia are a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by progressive cognitive decline, but differ in etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations [1].

While AD is associated with the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, other dementias, such as vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body dementia, are characterized by specific pathomorphological changes and damage to various areas of the brain, which causes a variety of clinical symptoms, including behavioral disorders and extrapyramidal symptoms and speech disorders that are less pronounced in the early stages of AD [2,3,4].

Modern treatment of Alzheimer’s disease includes the use of drugs such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine) and memantine, which improve cognitive function and slow down the deterioration of patients. Immunotherapy using monoclonal antibodies is aimed at removing amyloid plaques from the brain and slowing the progression of the disease, while promising methods include studying the effects on tau protein, neuroinflammation, and cellular and genetic therapies. In addition to medication, cognitive training, behavioral therapy, lifestyle support, and modern methods of care and social support for patients and their families play an important role [5,6,7,8].

Differential diagnosis between AD and other dementias is of fundamental importance for choosing the optimal treatment strategy and predicting the course of the disease [9].

In the modern diagnosis of AD, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is more accurate, since it allows you to directly assess the levels of markers that reflect pathological processes occurring in the brain. However, CSF sampling (lumbar puncture) is invasive and not always well tolerated by patients [10,11,12,13].

A blood test, in turn, is a more affordable and less invasive method. Unfortunately, the concentrations of specific AD markers in the blood are often lower than in CSF, which makes it difficult to accurately diagnose [14,15,16]. However, CSF is constantly exchanged and cleared via the blood, which suggests that blood may reflect pathological changes in the brain and thus is a good source of AD biomarkers [17].

Several candidate biomarkers have been identified in blood and blood cells, but their lack of sensitivity, specificity, and true relationship to brain mechanisms remains unclear. Currently, research is actively conducted to identify new, more sensitive and specific biomarkers of AD in the blood, which in the future can significantly simplify and expand the possibilities of early diagnosis of this disease [15,18,19,20,21].

The aim of this study was to compare the concentration of neurodegenerative biomarkers in CSF and blood in patients with AD and other types of dementia in order to find a quick and easy way to differentiate between types of dementia. For this purpose, a comprehensive assessment of neurodegenerative processes in patients with dementia was performed by analyzing specific biomarkers in CSF and blood plasma.

Using the scheme already described in the article by Zorkina and colleagues [22], in this study, the levels of markers of neurodegeneration in CSF were evaluated in order to differentiate AD from other types of dementia. Next, we evaluated the concentration of neurodegenerative biomarkers in the blood of participants in their different subgroups to identify differences between different forms of dementia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

The study included patients who were observed in the gerontology department of the N. A. Alekseev Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 1 from June 2022 to August 2022. The study involved 31 patients (23 women and 8 men) with dementia. All diagnoses were made based on the results of regular interdisciplinary consultations involving neurologists, neuropsychologists and psychiatrists. The diagnosis was determined in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Diagnosis F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease”—had 2 patients, F01 “Vascular dementia”—28, F06 “Other mental disorders caused by brain damage and dysfunction or somatic disease”—1.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration. Procedures involving human experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of Protocol No. 1 of 25 January 2022. Ethics Committee of the GBUZ «PKB No. 1 DZM».

All participants underwent standardized neurological examinations and neuropsychological testing. Cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination) [23]. Dementia was defined as an MMSE score ≤ 24. Then the patients underwent CSF and blood sampling procedures, which determined the concentration of biomarkers of neurodegeneration.

2.2. Taking CSF

CSF collection was performed by lumbar puncture with a sterile needle; the volume of CSF should be at least 1 mL. Within 1 h from the moment of sampling, the sample was centrifuged (1500 rpm) for 15 min, and then the supernatant was taken. The samples were stored at −80 °C.

2.3. Blood Plasma Collection

Blood parameters were measured in plasma. Blood samples for analysis were collected from the cubital vein in the fasting state, typically before 9 a.m. Plasma was isolated immediately following blood collection via centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and then stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.4. Multiplex Assay

Aβ40 (amyloid-β peptide with 40 amino acids), Aβ42 (amyloid-β peptide with 42 amino acids), Aβ42/40 ratio (comparison of Aβ42 to Aβ40), tTau (total tau), pTau181 (tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 181) were determined in CSF using multiplex analysis with a set of MILLIPLEX MAP Human Amyloid Beta and Tau Magnetic Bead Panel (manufactured by Merck KGaA in Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, the concentration was determined in pg/mL.

The concentration of blood plasma parameters was determined by multiplex analysis with the ProcartaPlex Human Neurodegeneration Panel 1 9-plex kit (manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific in Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration was determined in pg/mL. Plasma concentrations of the following parameters were determined: Aβ40, Aβ42, KLK6, NCAM-1 (Neural cell adhesion molecule 1), neurogranin, tTau, pTau181, TDP-43 (Transactive response DNA binding protein 43). In a multiplexed assay, each spectrally unique bead is labeled with antibodies specific for a single target protein, and bound proteins are identified with biotinylated antibodies and streptavidin–R-phycoerythrin (RPE). Samples were taken in two repetitions, and negative and positive controls were used.

The measurements were performed using a Luminex analyzer (LuminexTM 100/200TM, manufactured by Luminex Corporation in Austin, TX, USA).

2.5. Determination of AD Signs by CSF Marker Concentration

Signs of AD in CSF were determined according to the classification system A/T/N-Aβ, pTau, neurodegeneration (corresponds to tTau in CSF) [24]. The following variants are distinguished: normal (A-T–N–), without pathological changes characteristic of AD (A-T–N+, A-T+N–, A-T+N+), AD (A+T–N–, A+T–N+, A+T+N–, A+T+N+). The following values were used for the cut-off threshold: Aβ42 < 1013 pg/mL, pTau > 64 pg/mL, tTau > 3252 pg/mL. These values were selected according to the technology used to determine biomarkers [22,25]. According to the classification results of 31 patients, 24 patients had signs of AD (AD group), and 7 patients had no signs of AD (dementia group).

2.6. Statistical Processing

Analysis was performed using Jamovi (2.3.26 version) and RStudio (2023.06.1 Build 524 version) software. Upon receiving the data, its distribution was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. This assessment determined the appropriate criteria for statistical comparison: parametric or non-parametric. In the context of a normal distribution, the mean and standard deviation were utilized. In the case of an abnormal distribution, the median and interquartile range were calculated. Assuming a normal distribution, parametric analysis was conducted, using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests for post hoc analysis, and data were presented as Mean ± SE. Non-parametric analysis was performed in the case of non-normal distribution using the Kruskal–Wallis test and subsequent multiple comparison tests (Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner). The data were presented as Median (Q1, Q3). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted using the Jamovi and RStudio software for correlation assessment. A r < −0.7 or r > 0.7 and p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Thus, two groups of patients were evaluated in the experiment: patients with signs of AD according to CSF analysis (n = 24; 5 men and 19 women) and patients without signs of AD with a different type of dementia (n = 7; 3 men and 4 women). These groups did not differ in age and MMSE score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary table with the obtained data for the participants of the experiment.

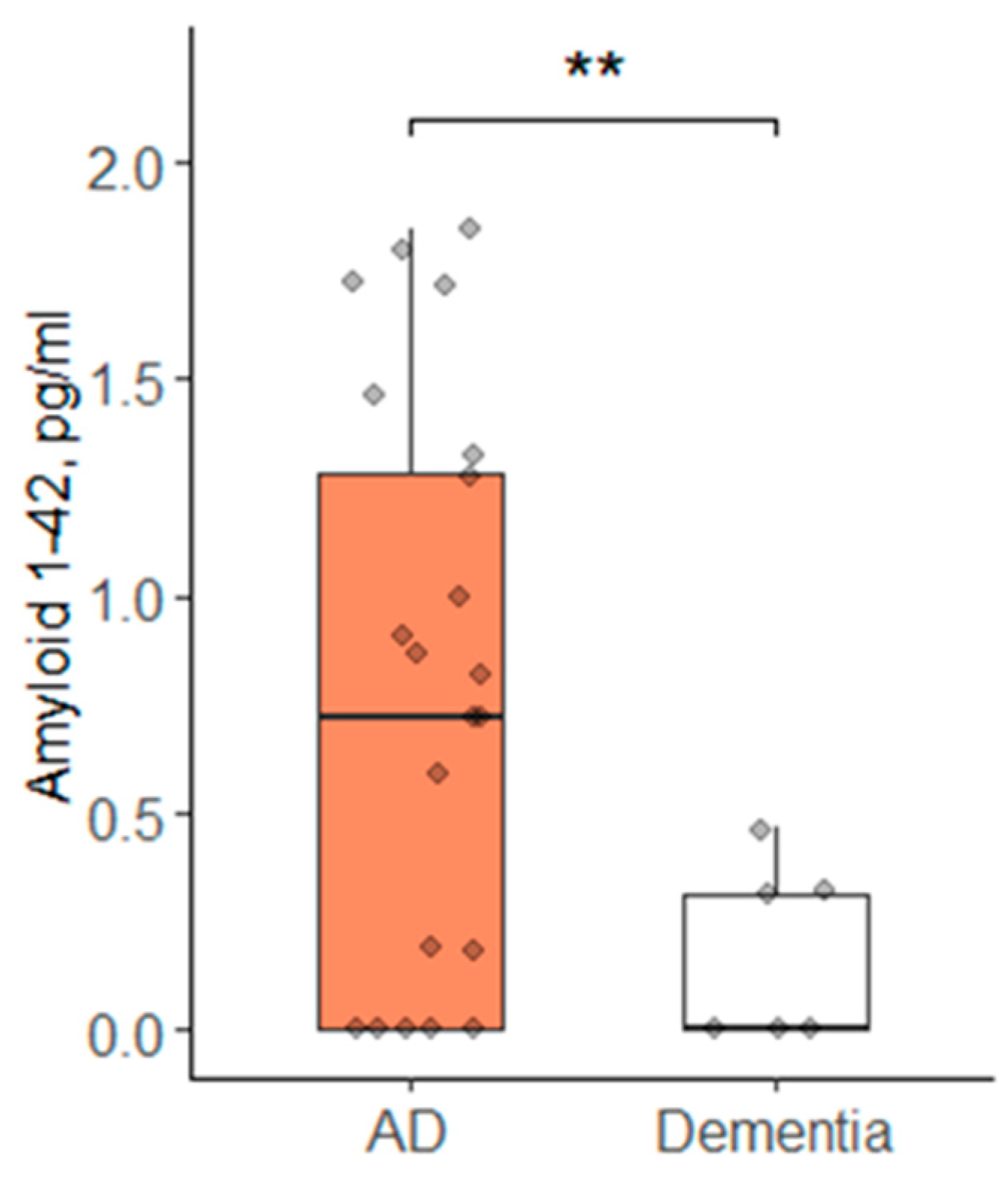

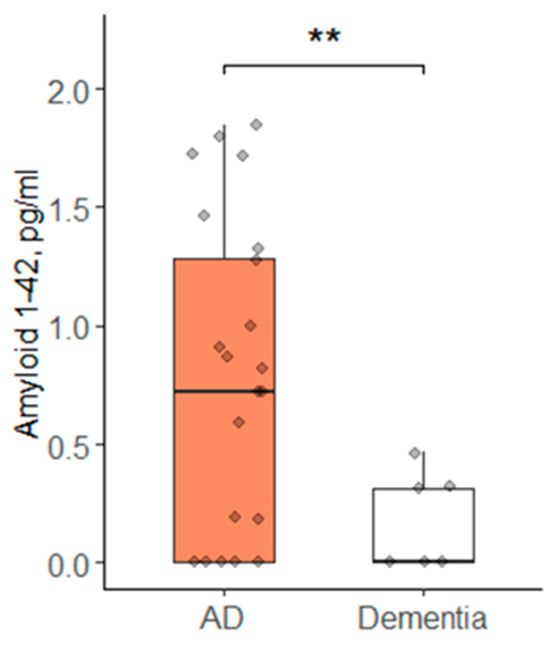

The experimental groups differed in the concentration of blood biomarkers only by the parameter Aβ42 (p = 0.001) according to the ANOVA test; its concentration in the AD group was higher than in dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aβ42 concentration in blood of patients with AD and other types of dementia; AD—group of patients with AD; Dementia—group of patients with other types of dementia; Data are expressed as Med (Q1; Q3) in boxplots. Black horizontal lines—medians; gray dots—single data points; **—p < 0.01.

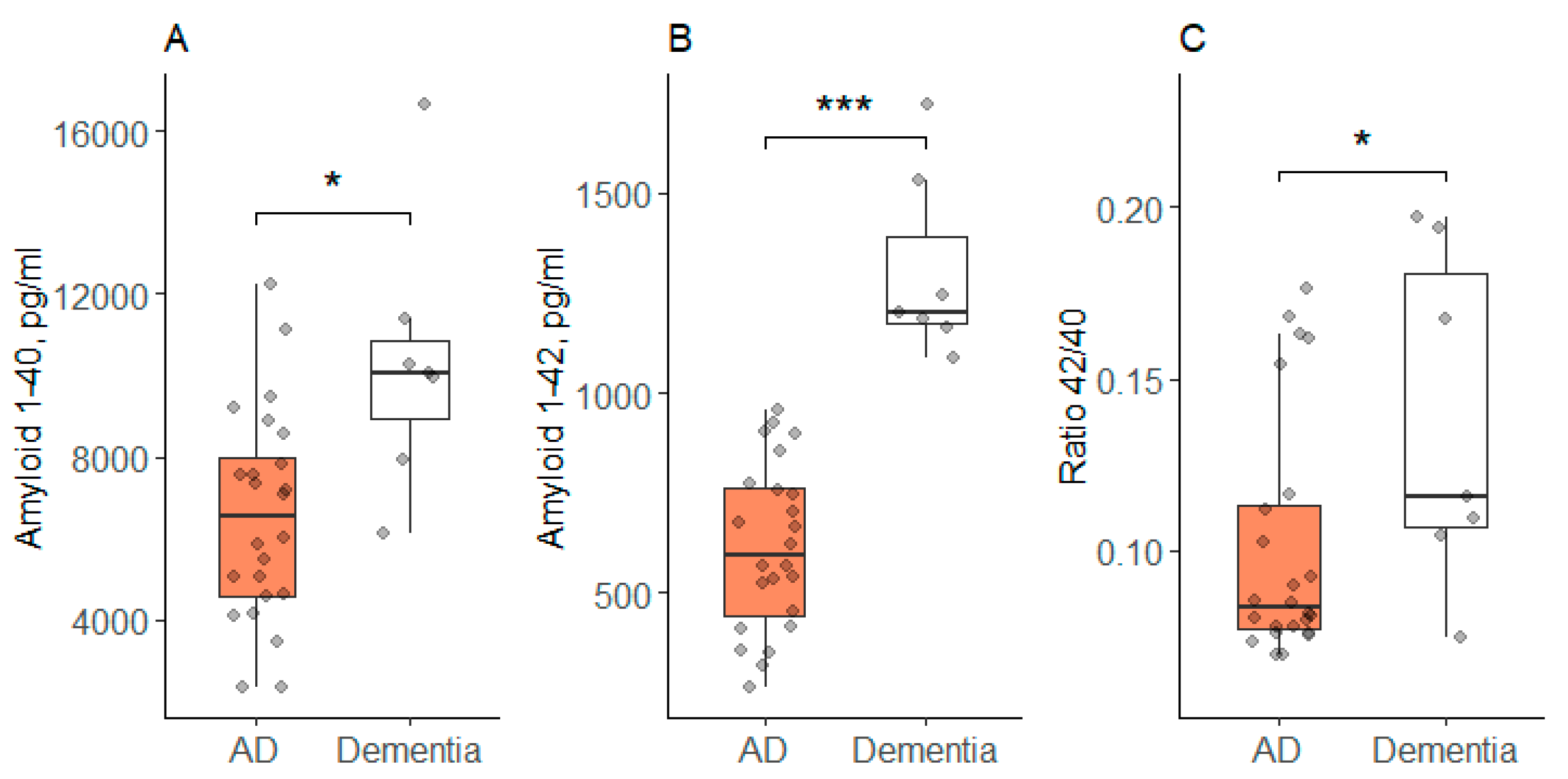

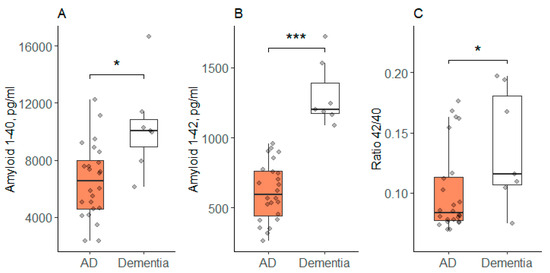

In addition, the ANOVA showed significant differences in the concentration of two CSF parameters: Aβ40 and Aβ42. The concentration of these indicators in the dementia group was significantly higher than in the AD group. The 42/40 CSF ratio differed between the groups at the significance level (p = 0.048) according to the Kruskal–Wallis test, and it was higher in the dementia group compared to the AD group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CSF concentration of neurodegenerative biomarkers in patients with AD and other types of dementia; (A) Aβ40 concentration in CSF; (B) Aβ42 concentration in CSF; (C) Ratio Aβ42/40 in CSF; AD—group of patients with AD; Dementia—group of patients with other types of dementia; Data are expressed as Med (Q1; Q3) in boxplots. Black horizontal lines—medians; gray dots—single data points; *—p < 0.05; ***—p < 0.001.

Next, we performed a correlation analysis between the concentrations of blood biomarkers and CSF, which showed that significant correlations were observed in the dementia group. CSF Aβ42 positively correlated with TDP-43 in blood plasma (r = 0.97; p < 0.001). The Aβ42/40 CSF ratio negatively correlated with KLK6 in blood plasma (r = −0.87; p = 0.01). In the AD group, no significant correlations were observed between blood and CSF parameters.

Additionally, we analyzed correlations between blood plasma parameters. The results are presented in Table 2. A strong positive relationship was shown between neurogranin and TDP-43 in the AD group, and a strong negative relationship was found between NCAM-1 and Aβ40 in the dementia group.

Table 2.

Correlation analysis of the concentration of biochemical parameters in blood plasma.

4. Discussion

This study aimed at a comprehensive assessment of neurodegenerative processes in patients with dementia by analyzing specific biomarkers in CSF and blood plasma. Using the already developed scheme described in the article by Zorkina and colleagues [22], the levels of CSF neurodegeneration markers were evaluated in order to differentiate AD from other types of dementia. Based on the CSF analysis results, the entire cohort of patients was divided into two subgroups: patients with AD and patients with other forms of dementia. Further, in both subgroups, the concentration of several neurodegenerative parameters of blood plasma was analyzed, which revealed potential differences between the groups [26,27,28].

We analyzed the level of neurodegenerative biomarkers in CSF in patients and showed that the subtypes of Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia differ significantly in some indicators. These differences are consistent with similar studies.

CSF Aβ40 levels were significantly lower in the AD group than in the dementia group. However, in other studies, the level of Aβ40 CSF in patients with AD and non-Alzheimer’s dementia often does not show a significant difference.

In one large study (n = 80 AD, n = 75 non-AD dementia, n = 30 controls), CSF Aβ40 levels were reduced in both AD patients (10,856 ± 4745 pg/mL) and non-Alzheimer’s dementia patients (10,519 ± 4491 pg/mL) compared to the control group (14,760 ± 7846 pg/mL), but the difference was statistically insignificant between the AD and non-AD dementia [29]. The authors conclude that the Aβ40 level alone does not allow us to reliably differentiate AD from other dementias, but adding the Aβ42/40 ratio to the biomarker panel increases the accuracy of differential diagnosis [29,30].

In another study (n = 22 AD, n = 11 non-AD dementia, n = 35 controls), the concentration of Aβ40 also did not differ between the AD and non-AD dementia groups, while Aβ42 and the Aβ42/ 40 ratio were significant markers for differentiating [30].

CSF Aβ42 levels significantly differed between AD and other dementias in our study. This also correlates with data from other studies. In Alzheimer’s disease, there is usually a decrease in CSF Aβ42 levels. This is due to the fact that Aβ42 tends to aggregate and form amyloid plaques in brain tissue, thereby reducing its concentration in CSF. In other dementias, CSF Aβ42 levels may be normal or even elevated, depending on the type of dementia and the presence or absence of amyloid pathology. Thus, Aβ42 can be one of the key markers used for differential diagnosis of AD from other types of dementia [31,32].

According to our study, the Aβ42/40 CSF ratio in the dementia group was higher than in the AD group. Studies by other scientists have also shown that the ratio of Aβ42/40 in CSF in patients with non-Alzheimer’s dementia is significantly higher than in patients with AD. In particular, in a large study involving patients with various forms of dementia, it was found that in patients with AD, the ratio of Aβ42/40 in CSF is statistically significantly lower than in patients with other types of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia [32]. This difference allows us to use this indicator for early differential diagnosis of AD and other dementias, since in AD the decrease in Aβ42 relative to Aβ40 is more pronounced than in other forms of dementia [31,32]. For example, in the study of O. Hansson et al. It was shown that in patients with mild cognitive impairment who subsequently developed AD, the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio was significantly lower compared to those who remained stable or developed other forms of dementia [31]. Similar data were obtained in later studies, where it is noted that the Aβ42/40 ratio, rather than the absolute values of Aβ42 or Aβ40, provides the greatest accuracy in distinguishing AD and other dementias [31,32].

Thus, our study showed that the concentration of Aβ40, Aβ42 and the ratio Aβ42/40 in CSF can be used to differentiate AD from other types of dementia. However, as mentioned earlier, CSF analysis is quite difficult to perform, so the main goal of our study was to study blood biomarkers that can detect AD. We found that patients with AD have higher blood levels of Aβ42 compared to other types of dementia. Blood Aβ42 is a promising non-invasive biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of AD. A low Aβ42/40 in blood plasma can predict the transition from MCI to dementia within two years.

The level of Aβ42 in the CSF and blood in AD shows the opposite dynamics compared to other dementias. In AD, Aβ42 actively accumulates as amyloid plaques in the brain tissue. This leads to a decrease in the soluble fraction of Aβ42, which can diffuse into CSF, and a decrease in the concentration of Aβ42 in CSF by 50% or more compared to the norm. In addition, there is a reduced transport of Aβ42 from the brain to CSF due to its aggregation [33,34,35,36,37].

In AD the blood–brain barrier is damaged, which increases the leakage of Aβ42 from the brain into the blood. This is confirmed by an inverse correlation: a low level of Aβ42 in blood plasma is associated with a high level of brain amyloidosis [38,39].

This may be due to the fact that amyloid pathology dominates in AD: Aβ42 aggregation in the brain and there is a decrease in CSF and a compensatory increase in blood in the early stages [40]. Aggregation of the peptide in the brain and poor clearance of it are the reasons for the opposing dynamics of Aβ42 (increasing in CSF and decreasing in blood) in AD. Less noticeable alterations are seen in other dementias because amyloid pathology is not the primary one [41].

The final stage of the study was a correlation analysis between CSF and plasma biomarker levels, which allowed us to assess the relationship between neurodegenerative processes occurring in the central nervous system and their reflection in peripheral blood [26,27,28]. If we look at the studies of other authors, we can find that most studies focus on individual biomarkers or their combinations, but not on their relationship to each other in different body fluids. TDP-43 is considered an additional biomarker of neurodegeneration, but existing reviews and studies do not provide data on a direct positive correlation between Aβ42 in CSF and TDP-43 in blood plasma. In our study, it was shown that in the dementia group, Aβ42 in CSF positively correlated with TDP-43 in blood plasma. Current evidence suggests that dementia is often accompanied by a mixed pathology—the simultaneous accumulation of several abnormal proteins, including amyloid, tau, alpha-synuclein, and TDP-43. At the same time, combined pathology is associated with a more severe and rapid course of the disease [32]. If a correlation is found between Aβ42 and TDP-43, it will allow us to more accurately identify the subtypes of dementia and make a more subtle differential diagnosis between Alzheimer’s disease, LATE (limbic encephalopathy with TDP-43) and other forms [42]. Thus, identifying the correlation between CSF Aβ42 and plasma TDP-43 can be an important tool for comprehensive assessment of dementia pathogenesis, predicting outcomes, and selecting optimal therapy.

Similarly, it is important to find that the Aβ42/40 CSF ratio was negatively correlated with KLK6 in blood plasma. There is little data on this phenomenon, only in a 2018 study of plasma KLK6 and CSF levels in Alzheimer’s patients and controls, it was noted that plasma KLK6 levels did not correlate with t-tau, p-tau, or Aβ42, but there was a weak negative correlation between plasma KLK6 and Aβ40 (r = −0.27, p = 0.02) [43]. Thus, to date, there are no data confirming a negative correlation between the ratio of Aβ42/40 in CSF and the level of KLK6 in blood plasma in patients with dementia, and our results showed such a relationship for the first time.

Our study revealed correlations of blood biomarkers in patients with AD. Thus, KLK6 in the blood correlates with tTau, NCAM-1, Tau181, TDP-43, and neurogranin. Correlations between KLK6 and the listed biomarkers were found only for CSF, but not for blood plasma [43]. In large studies of blood parameters, it was shown that the level of KLK6 in blood plasma in patients with AD can be increased compared to the control, especially in the late stages of the disease. However, in the same studies, it is noted that the level of KLK6 in plasma does not correlate with the classical biomarkers of AD in CSF tTau, pTau181 or Aβ42 [43]. The found correlations between KLK6 and other biomarkers in the blood of patients with AD suggest a multifaceted role of this protein in the pathogenesis of the disease. In particular, the correlation between KLK6 and tau proteins (tTau, pTau181) can potentially indicate the possible involvement of KLK6 in tau protein processing, and changes in KLK6 activity can affect the accumulation or modification of tau protein, contributing to neurodegeneration. In addition, the correlation between KLK6 and NCAM-1 indicates a possible effect of KLK6 on synaptic function and plasticity, where its changes can potentially lead to disruption of synaptic connections. The interaction of KLK6 with TDP-43, judging by the correlation between these proteins, may reflect the involvement of KLK6 in the processes of gene regulation and RNA processing. Finally, the correlation between KLK6 and neurogranin further highlights the association of KLK6 with synaptic dysfunction and extracellular matrix degradation, which together contribute to the development of AD. Thus, the found correlations suggest that KLK6 plays an important role in the complex of pathological processes underlying AD.

In addition, our study showed that in the AD group, NCAM-1 in blood plasma correlates with Aβ42 and neurogranin. Studies by other authors show that the level of circulating NCAM-1 in the blood and CSF differs in patients with AD compared to the control group [44]. However, its correlations with Aβ42 and neurogranin were not observed in other studies. NCAM-1 plays an important role in the development of the nervous system and synaptic plasticity. The presence of a correlation of NCAM-1 with Aβ42 and neurogranin in blood plasma may presumably indicate a violation of synaptic connections associated with amyloid pathology.

In addition, we showed that in the AD group, TDP-43 in the blood correlates with neurogranin. Available studies indicate that the level of TDP-43 in blood plasma is elevated in some patients with AD and may reflect the presence of TDP-43 pathology in the brain [45]. TDP-43 in the blood is associated with neurodegenerative changes and structural changes in the brain detected by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) [46]. However, no correlations between TDP-43 and neurogranin have been reported in available studies that analyzed plasma biomarkers in AD patients. The correlation between TDP-43 and neurogranin may indicate a link between TDP-43-associated pathology and synaptic dysfunction. Neurogranin release from damaged synapses may be associated with TDP-43-dependent processes affecting the structure or function of synapses.

We also found a correlation between HCAM-1 and Aβ40 in the blood of patients with dementia. Given the role of NCAM-1 in synaptic function and the role of amyloid in the development of AD, it can be assumed that the correlation between blood levels of NCAM-1 and Aβ40 may reflect the relationship between synaptic dysfunction and amyloid pathology in AD. Changes in NCAM-1 levels may be a response to amyloid stress in the brain.

Thus, our study revealed new correlations between biomarkers in blood plasma in patients with AD. Establishing new links between biomarkers in blood plasma, a more accessible and less invasive source of biomaterial, can help to create more effective methods for the diagnosis and treatment of this serious disease.

Our research has a limitation. When analyzing CSF indicators, a much higher number of participants with AD was found compared to other types of dementia. Thus, the study of blood parameters was carried out on samples of different sizes. Additionally, the overall small sample size is a limitation of our study. In the future, it is necessary to confirm the results obtained on comparable and larger samples of participants.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we evaluated the levels of markers of CSF neurodegeneration in order to differentiate AD from other types of dementia. There was a difference in the concentration of some CSF and blood parameters between patients with AD and other types of dementia. We found that in AD, there is a decrease in Aβ40 and Aβ42 in CSF compared to non-Alzheimer’s dementia, which is confirmed by earlier studies by other authors. We also showed that dementias of different types differ in the concentration of Aβ42 in plasma—AD is characterized by an increase in its concentration compared to non-Alzheimer’s dementias. We suggest that an estimate of plasma Aβ42 concentrations can potentially be used to differentiate AD from other types of dementia. Additionally, we found several significant correlations between plasma and CSF parameters, which allowed us to assess the relationship between neurodegenerative processes in the central nervous system and the periphery. Aβ42 in the blood can be considered a promising non-invasive biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of AD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., O.G., V.C., G.K. and A.M.; Data curation, I.M., V.U. and D.A.; Funding acquisition, G.K.; Investigation, O.G., V.C., G.K. and A.M.; Methodology, I.M. and K.P.; Project administration, A.M.; Resources, K.P., D.A., E.Z., A.A., K.K., O.G., V.C., G.K. and A.M.; Supervision, O.G. and V.C.; Writing—original draft, A.O., O.A. and A.T.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The manuscript was prepared as a part of V. Serbsky Federal Medical Research Centre of Psychiatry and Narcology state’s assignment No. CMGE-2025-0009 (Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the GBUZ «PKB No. 1 DZM», Protocol No. 1 of 25 January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| NCAM-1 | Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| TDP-43 | Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafian, H.; Zadeh, E.H.; Khan, R.H. Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Inhibition of Amyloid Beta and Tau Tangle Formation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badji, A.; Youwakim, J.; Cooper, A.; Westman, E.; Marseglia, A. Vascular Cognitive Impairment—Past, Present, and Future Challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 90, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.S. Pathophysiology of Dementia. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, 52, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangwaritorn, S.; Lee, C.; Metchikoff, E.; Razdan, V.; Ghafary, S.; Rivera, D.; Pinto, A.; Pemminati, S. A Review of Recent Advances in the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e58416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldmacher, D.S. Treatment of Alzheimer Disease. Contin. (Minneap Minn.) 2024, 30, 1823–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waite, L.M. New and Emerging Drug Therapies for Alzheimer Disease. Aust. Prescr. 2024, 47, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-K.; Fuh, J.-L. A 2025 Update on Treatment Strategies for the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2025, 88, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; Chang, K.-X.; Chen, Y.-F.; Yan, K.; Wang, C.-X.; Hua, Q. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Towards Accuracy and Accessibility. J. Biol. Methods 2024, 11, e99010010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milos, T.; Vuic, B.; Balic, N.; Farkas, V.; Nedic Erjavec, G.; Svob Strac, D.; Nikolac Perkovic, M.; Pivac, N. Cerebrospinal Fluid in the Differential Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Update of the Literature. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2024, 24, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridel, C.; Somers, C.; Sieben, A.; Rozemuller, A.; Niemantsverdriet, E.; Struyfs, H.; Vermeiren, Y.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; De Deyn, P.P.; Bjerke, M.; et al. Associating Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology with Its Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers. Brain 2022, 145, 4056–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, S.; Remnestål, J.; Yousef, J.; Olofsson, J.; Markaki, I.; Carvalho, S.; Corvol, J.-C.; Kultima, K.; Kilander, L.; Löwenmark, M.; et al. Multi-Cohort Profiling Reveals Elevated CSF Levels of Brain-Enriched Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrowder, D.A.; Miller, F.; Vaz, K.; Nwokocha, C.; Wilson-Clarke, C.; Anderson-Cross, M.; Brown, J.; Anderson-Jackson, L.; Williams, L.; Latore, L.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista, S.; Mapstone, M.; Caraci, F.; Emanuele, E.; López-Ortiz, S.; Martín-Hernández, J.; Triaca, V.; Imbimbo, C.; Gabelle, A.; Mielke, M.M.; et al. A Critical Appraisal of Blood-Based Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 96, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Hu, Y.; Cummings, J.; Mattke, S.; Iwatsubo, T.; Nakamura, A.; Vellas, B.; O’Bryant, S.; Shaw, L.M.; Cho, M.; et al. Blood-Based Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease: Current State and Future Use in a Transformed Global Healthcare Landscape. Neuron 2023, 111, 2781–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, O.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Dage, J. Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease in Clinical Practice and Trials. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humpel, C.; Hochstrasser, T. Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. World J. Psychiatry 2011, 1, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assfaw, A.D.; Schindler, S.E.; Morris, J.C. Advances in Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease (AD): A Review. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhauria, M.; Mondal, R.; Deb, S.; Shome, G.; Chowdhury, D.; Sarkar, S.; Benito-León, J. Blood-Based Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: Advancing Non-Invasive Diagnostics and Prognostics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B.; Zetterberg, H.; Ashton, N.J. Blood-Based Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease—Moving towards a New Era of Diagnostics. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024, 62, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantellatto Grigoli, M.; Pelegrini, L.N.C.; Whelan, R.; Cominetti, M.R. Present and Future of Blood-Based Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease: Beyond the Classics. Brain Res. 2024, 1830, 148812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorkina, Y.A.; Morozova, I.O.; Abramova, O.V.; Ochneva, A.G.; Gankina, O.A.; Andryushenko, A.V.; Kurmyshev, M.V.; Kostyuk, G.P.; Morozova, A.Y. Use of modern classification systems for complex diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease. Zh Nevrol. Psikhiatr Im. S S Korsakova 2024, 124, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenau, J.L.; Timmers, T.; Wesselman, L.M.P.; Verberk, I.M.W.; Verfaillie, S.C.J.; Slot, R.E.R.; van Harten, A.C.; Teunissen, C.E.; Barkhof, F.; van den Bosch, K.A.; et al. ATN Classification and Clinical Progression in Subjective Cognitive Decline: The SCIENCe Project. Neurology 2020, 95, e46–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.O.; Dias, N.S.; Burgos, I.C.B.; Costa, M.V.; Carvalho, A.T.; Teixeira, A.L.; Barbosa, I.G.; Santos, L.A.V.; Rosa, D.V.F.; Ribeiro, A.J.F.; et al. Millipore xMap® Luminex (HATMAG-68K): An Accurate and Cost-Effective Method for Evaluating Alzheimer’s Biomarkers in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 716686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, Y.-J.; Guo, J. Biofluid Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress, Problems, and Perspectives. Neurosci. Bull. 2022, 38, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulewicz, M.; Kulczyńska-Przybik, A.; Mroczko, P.; Kornhuber, J.; Lewczuk, P.; Mroczko, B. Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease in Clinical Practice: The Role of CSF Biomarkers during the Evolution of Diagnostic Criteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Salvadó, G.; Schindler, S.E.; He, Y.; Janelidze, S.; Collij, L.E.; Saef, B.; Henson, R.L.; Chen, C.D.; Gordon, B.A.; et al. Highly Accurate Blood Test for Alzheimer’s Disease Is Similar or Superior to Clinical Cerebrospinal Fluid Tests. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaets, S.; Le Bastard, N.; Martin, J.-J.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; De Deyn, P.P.; Engelborghs, S. Cerebrospinal Fluid Aβ1-40 Improves Differential Dementia Diagnosis in Patients with Intermediate P-tau181P Levels. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 36, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewczuk, P.; Esselmann, H.; Otto, M.; Maler, J.M.; Henkel, A.W.; Henkel, M.K.; Eikenberg, O.; Antz, C.; Krause, W.-R.; Reulbach, U.; et al. Neurochemical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Dementia by CSF Abeta42, Abeta42/Abeta40 Ratio and Total Tau. Neurobiol. Aging 2004, 25, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, O.; Zetterberg, H.; Buchhave, P.; Andreasson, U.; Londos, E.; Minthon, L.; Blennow, K. Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease Using the CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 Ratio in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007, 23, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Vanderstichele, H.; Lindberg, O.; van Westen, D.; Stomrud, E.; Minthon, L.; Blennow, K.; et al. CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 and Aβ42/Aβ38 Ratios: Better Diagnostic Markers of Alzheimer Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016, 3, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spies, P.E.; Verbeek, M.M.; van Groen, T.; Claassen, J.A.H.R. Reviewing Reasons for the Decreased CSF Abeta42 Concentration in Alzheimer Disease. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; Kim, S.J.; Hong, S.; Kim, Y. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease Utilizing Amyloid and Tau as Fluid Biomarkers. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.-A.; Lim, J.-H.; Sul, A.-R.; Lee, M.; Youn, Y.C.; Kim, H.-J. Cerebrospinal Fluid β-Amyloid1–42 Levels in the Differential Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, T.; Linker, G.; Mirza, N.; Putnam, K.T.; Friedman, D.L.; Kimmel, L.H.; Bergeson, J.; Manetti, G.J.; Zimmermann, M.; Tang, B.; et al. Decreased Beta-Amyloid1-42 and Increased Tau Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 2003, 289, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, N.; Hesse, C.; Davidsson, P.; Minthon, L.; Wallin, A.; Winblad, B.; Vanderstichele, H.; Vanmechelen, E.; Blennow, K. Cerebrospinal Fluid Beta-Amyloid(1–42) in Alzheimer Disease: Differences between Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease and Stability during the Course of Disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.L.; Klunk, W.E.; Mathis, C.A.; Snitz, B.E.; Chang, Y.; Tracy, R.P.; Kuller, L.H. Relationship of Amyloid-Β1–42 in Blood and Brain Amyloid: Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study. Brain Commun. 2019, 2, fcz038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Stomrud, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Zetterberg, H.; van Westen, D.; Jeromin, A.; Song, L.; Hanlon, D.; Tan Hehir, C.A.; Baker, D.; et al. Plasma β-Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.L.; Chang, Y.; Ives, D.G.; Snitz, B.E.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Carlson, M.C.; Rapp, S.R.; Williamson, J.D.; Tracy, R.P.; DeKosky, S.T.; et al. Blood Amyloid Levels and Risk of Dementia in the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS): A Longitudinal Analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Huang, L.-C.; Hsieh, S.-W.; Huang, L.-J. Dynamic Blood Concentrations of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpilyukova, Y.A.; Fedotova, E.Y.; Kuzmina, E.N.; Illarioshkin, S.N. New forms of dementia in neurodegenerative diseases: Molecular basis, phenomenology, and diagnostic capability. Russ. Neurol. J. 2022, 27, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.; Soosaipillai, A.; Sando, S.B.; Lauridsen, C.; Berge, G.; Møller, I.; Grøntvedt, G.R.; Bråthen, G.; Begcevic, I.; Moussaud, S.; et al. Assessment of Kallikrein 6 as a Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Gao, T.; Bai, Z.; Yuan, Z. Circulating APP, NCAM and Aβ Serve as Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. 2018, 1699, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, P.; McAuley, E.; Gibbons, L.; Davidson, Y.; Pickering-Brown, S.M.; Neary, D.; Snowden, J.S.; Allsop, D.; Mann, D.M.A. TDP-43 Protein in Plasma May Index TDP-43 Brain Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 116, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, C.E.; Zachariou, V.; Sudduth, T.L.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Jicha, G.A.; Nelson, P.T.; Wilcock, D.M.; Gold, B.T. Plasma TDP-43 Levels Are Associated with Neuroimaging Measures of Brain Structure in Limbic Regions. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2023, 15, e12437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Swiss Federation of Clinical Neuro-Societies. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.