Abstract

In this study, a structured and methodological evaluation approach for eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methods in medical image classification is proposed and implemented using LIME and SHAP explanations for chest X-ray interpretations. The evaluation framework integrates two critical perspectives: predictive model-centered and human-centered evaluations. Predictive model-centered evaluations examine the explanations’ ability to reflect changes in input and output data and the internal model structure. Human-centered evaluations, conducted with 97 medical experts, assess trust, confidence, and agreements with AI’s indicative and contra-indicative reasoning as well as their changes before and after provision of explainability. Key findings of our study include explanation of sensitivity of LIME and SHAP to model changes, their effectiveness in identifying critical features, and SHAP’s significant impact on diagnosis changes. Our results show that both LIME and SHAP negatively affected contra-indicative agreement. Case-based analysis revealed AI explanations reinforce trust and agreement when participant’s initial diagnoses are correct. In these cases, SHAP effectively facilitated correct diagnostic changes. This study establishes a benchmark for future research in XAI for medical image analysis, providing a robust foundation for evaluating and comparing different XAI methods.

1. Introduction

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has gained significant attention in recent years due to its success in complex learning tasks [1]. Since AI systems are often considered black boxes, the rationale behind AI-generated outcomes cannot always be comprehended by end users of AI [2]. Therefore, the utility of these opaque systems in real-life applications is limited [3]. This limitation is particularly critical in high-stakes domains such as healthcare, where understanding and trust in AI systems are crucial [4]. Specifically, in medical imaging, where AI has demonstrated potential in diagnosing conditions from radiological scans, XAI provides a visual proof of the decision-making mechanism of the predictive model [5,6]. By providing transparency and interpretability, XAI allows clinicians to better understand and validate AI predictions, leading to increased trust and confidence in these systems [7]. This, in turn, facilitates the integration of AI into clinical workflows, ultimately improving patient outcomes [8,9].

The biggest gap in the XAI literature currently is the evaluation of explanations. Since it is hard to identify a good, effective, or successful explanation because of the domain-dependent and multifaceted nature of explanations as well as diversity of stakeholders, the evaluation phase of XAI has always been disregarded. In most of the XAI papers, evaluation has not (sufficiently) been taken into account and only providing anecdotal evidence by visual explanations is the common practise [10,11]. However, for both AI developers and the other end-users of XAI such as medical experts in the healthcare, evaluation is a necessity.

On the one hand, the success or usefulness of explanations provided by XAI methods in healthcare often depends more significantly on the assessment of medical experts than in other fields. Given the critical nature of medical decisions, the proper explanations of black-boxes play a crucial role in gaining trust and acceptance among healthcare professionals. Thus, measuring the usefulness and understandability of explanations, alignment with the domain knowledge, and user satisfaction and trust are some of the metrics that should be included into the human-centered evaluation aspect for XAI in healthcare [10,12,13,14].

On the other hand, to ensure reliability of the explanation with respect to the predictive model, a proper evaluation must be conducted. Evaluating XAI methods with respect to the faithfulness of the explanation to the predictive model is a crucial aspect. It ensures that the internal decision-making processes can be verified and the rationale of the predictive model can be explained. Sanity checks are suitable candidates for this purpose [15]. Key techniques employed in predictive model-centered evaluation are mostly based on two perspectives, i.e, data-based and model-structure based. Data-based approaches are centered around input data by observing changes in the explanation when the input data is altered, and on output data by evaluating whether the explanations reflect the full range of output values, thereby assessing their sensitivity to variations in the output [10].

Clearly, it is imperative to develop comprehensive evaluation methodologies able to assess to what extent the explanation reflects the decision-making mechanism of the predictive model and accurately capture the perspectives and needs of medical experts, ensuring the effective integration of XAI into clinical decision-making processes. Within this direction, the primary objective of this paper is to design and develop an evaluation framework for XAI for medical imaging classification. This framework is designed to bridge the gap between predictive model-centered and human-centered evaluations, ensuring that XAI explanations are both technically sound and practically useful for medical experts. By thoroughly assessing the effectiveness of these explanations in reflecting the internal decision-making processes of predictive models and enhancing their interpretability and trustworthiness among healthcare professionals, this framework aims to facilitate the integration of XAI into clinical decision-making processes.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a comprehensive evaluation framework for XAI for medical image classification, which uniquely integrates both human-centered and predictive model-centered evaluation criteria, ensuring a thorough assessment from multiple required perspectives in medical image analysis research. The framework’s design encompasses coverage perspectives that scale across different dimensions of evaluation, which makes it robust and versatile for various XAI methods.

- We design a predictive model-centered evaluation method to cover both the input and output data and the inner structures of the predictive model. By addressing the capability of explanations to reflect changes in input data, model structures, and output data, this evaluation method ensures a complete and comprehensive assessment of the explanations provided by XAI methods in selecting the top 10 features identified by SHAP to be able to apply sanity checks or comparisons between the XAI methods.

- We introduce a practical and standardized approach for handling SHAP explanations by selecting the top 10 features for comparison with other XAI methods. This approach addresses a previously vague aspect of SHAP values in the literature, and provides a clearer path for future reproducible research in XAI.

- We conduct a statistically sound user study involving a cohort of 97 medical experts for human-centered XAI evaluation. This evaluation was constructed around four critical perspectives, i.e., trust, confidence, agreement, and diagnosis change. By encompassing both subjective and objective measures, this study serves as a benchmark for future research on XAI in medical image analysis.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of previous research on XAI in medical imaging, highlighting gaps and opportunities for the evaluation of XAI. Section 3 provides background information on the employed XAI methods, namely LIME and SHAP, and the evaluation metrics from the existing literature, establishing the foundation for our study. Next, Section 4 details the design and implementation methodology of the proposed evaluation framework, for both predictive model-centered and human-centered evaluations. This will be followed by Section 5, where findings from applying the framework to chest X-ray interpretations are presented and analyzed. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion of the key results and their implications in Section 7 and outlines potential directions for future research in Section 8.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review the existing literature on XAI evaluation, with a focus on its application in the domain of medical imaging, specifically chest X-ray scan analysis. The taxonomies, methodologies, and metrics associated with XAI evaluation methods for medical image explanations are examined, and the gaps and opportunities for future research are highlighted.

2.1. XAI Evaluation for Medical Image Analysis

Jin et al. [16] applied XAI techniques to medical images and followed an evaluation framework comprising a quantitative and a qualitative approach. For quantitative evaluation, they employed a model parameter randomization check, referred to as “Faithfulness” in their paper, while for qualitative assessment, they conducted a user study with six medical experts to assess the “Plausibility” of explanations with respect to prior knowledge in the field. In another study, Muddamsetty et al. [17] were applied state-of-the-art XAI methods to Retinal OCD images, where only a user-oriented approach was used for evaluation. An eye tracker system was employed to identify relevant areas while medical experts diagnosed, and these areas were compared with explanations using Kullback–Leibler Divergence. Rahimiaghdam et al. [18] implemented a comprehensive evaluation for the explanation of the segmentation in chest X-ray scan diagnosis. The main evaluation approach was based on the overlapping score between the LIME explanations and the ground truth. Not only was the overlapping score with multi-label consideration and the minimized discrepancy considered as a metric, but also informativeness, localization, coverage, multi-target capturing, and proportionality of the explanations. Lin et al. [19] applied an ensemble XAI approach to chest X-ray scans and proposed an evaluation method covering both qualitative and quantitative aspects. This included incremental deletion, named as ‘critical area absence,’ followed by assessing ‘localization effectiveness’ through comparison with ground truth generated by radiologists. Additionally, they conducted a user study for qualitative evaluation to identify trust over explanations. Similarly, in another study [20], a user study involving three radiologists was reported, in which understandability, satisfaction, level of abstraction, completeness, and accuracy of the explanations were assessed.

Additionally, we focused specifically on chest X-ray scan analysis. One of those studies [21] provide an overview of XAI methods on chest X-ray scans until 2021. We reviewed each study provided by this review paper and identified their corresponding XAI evaluation approaches. To cover the papers from 2021 to the present, we reviewed additional explainable AI papers on chest X-ray scan analysis focusing on their XAI evaluation methodologies. Out of 51 papers reviewed, 34 did not include any evaluation of the explanations. Papers that included at least one evaluation approach are summarized in Table 1. These papers were categorized based on different aspects of XAI evaluation as proposed in our study. Six papers incorporated a user study which is mostly conducted with one or a few radiologists while four papers applied ground truth area comparison without conducting a user study. Most of the evaluation applied in the literature focused on either human-centered or predictive model-centered evaluation. Only four papers applied at least one evaluation method from both human-centered and predictive model-centered evaluations. The least applied methods are model structure-based evaluation and user trust metric. The most applied XAI evaluation approach is the agreement using localization.

Table 1.

Summary of papers incorporating at least one XAI evaluation approach, categorized by applied methods and evaluation types (predictive model-centered and human-centered). “#” denotes the number of participants involved in the user study and “X” indicates that the corresponding evaluation type was applied in the referenced paper.

2.2. XAI Evaluation Frameworks

Jin et al. [37] proposed a guideline for XAI evaluation in the medical image classification. Different evaluation perspectives were suggested to be examined and they were grouped under three categories as clinical usability (understandability, and clinical relevance), evaluation (truthfulness, and informative plausibility), and operation (computational efficiency). The first category is based on the agreement of medical experts on the explanations. The second category is based on the predictive model-centered evaluation via the data-based tests, and the last one is the computational efficiency which checks if the explanation is within the tolerable waiting time. In another proposed XAI evaluation framework [12], evaluation measures and design goals were classified with respect to different types of end-users, e.g., AI experts, data experts, and AI novices (end-users who use the AI system but have no background in AI). Usefulness, user trust and reliance, privacy awareness, and computational measures were some of the suggested metrics to assess in the XAI evaluation. Lopes et al. [13] have reviewed the XAI evaluation approaches and grouped them into human-centered and computer-centered approaches. For the human-centered evaluation, they identified trust, usefulness and satisfaction, understandability, and performance as metrics and a different variety of approaches to test these metrics were presented. The computer-centered evaluation was composed of interpretability, which was mostly based on the complexity size of the explanation and fidelity, which checks the completeness and soundness of the explanation with respect to the predictive model. The paper points out the imbalance between human-centered and computer-centered XAI evaluations, noting the particularly low presence of human-centered evaluations in the existing literature. Gilpin et al. [14] proposed an XAI evaluation framework and divided XAI evaluation into three aspects, i.e., processing, representation, and explanation. The processing is based on the faithfulness of the explanation to the predictive model, representation is based on the presentation concerns such as complexity of the explanation, and finally the explanation covers the human evaluations. Finally, Nauta et al. [10] provided a comprehensive overview of XAI evaluation with suggested characteristics (Co-12) of XAI serving as evaluation metrics. XAI evaluation was examined under three categories, i.e., content, presentation, and the user-centered evaluation. When healthcare papers are the focus within the paper, the most applied XAI characteristics were identified as Correctness, Completeness, Continuity, Contrastivity, Compactness, and Coherence. The first four characteristics are based on predictive model-centered evaluation and the last two are based on human-centered evaluation. However, studies examined in the survey paper applying both predictive model-centered and human-centered evaluations do not exist in the healthcare domain.

After reviewing the existing literature on XAI methods applied to chest X-ray scans and proposed XAI evaluation frameworks, it becomes evident that current evaluation approaches are often incomplete and one-sided. Many studies lack rigorous evaluation, relying on anecdotal evidence or using limited quantitative analyses that overlook the relationship between the predictive model and the XAI method. While some evaluations solely focus on human-centered criteria, others emphasize model-based fidelity without considering the human interpretability dimension. As a result, the existing frameworks do not provide a unified, reproducible strategy that connects these two perspectives within the healthcare domain.

Our proposed evaluation framework, XIMED, directly addresses this gap by comprehensively integrating both predictive model-centered and human-centered evaluation within a single unified design. The novelty of XIMED lies not only in combining these perspectives but in establishing a standardized and reproducible framework that implements their integration. Specifically, it incorporates essential predictive model-centered criteria (input–output relationships and model structure–based evaluation), which constitute the minimum yet complete foundation required to assess explanations against the predictive model. These components ensure that all three elements of the model— input, structure, and output—are systematically examined through representative tests. In parallel, XIMED integrates human-centered criteria (trust calibration and agreement alignment) that capture how clinicians perceive and align with AI explanations by combining self-reported indicators of trust with performance-based measures of diagnostic alignment.

Unlike prior frameworks that remain largely conceptual or domain-agnostic, XIMED is a compact, scalable, and ready-to-use framework that can be directly applied to any deep learning model for 2D medical imaging tasks. Its standardized evaluation pipeline enables consistent benchmarking across studies while maintaining domain specificity for healthcare applications, thereby establishing a robust and practical baseline for evaluation of XAI methods in medical imaging.

3. Background

3.1. XAI Methods

Various methods have emerged in the quest to make complex deep learning models more interpretable. Adadi and Berrada [38] examined XAI methods based on the scope of the explainability (global/local) and based on the predictive model to be explained (model-specific/model-agnostic). From the scope-based perspective to the XAI methods, global explanations provide general behaviour of the predictive model for its decisions. It is important for the population-based decisions or identifying trends. On the other hand, local explainability covers the behavior of the predictive model over a single instance or a sub-group of instances. These kinds of explanations are important because the explanations require specific focus, i.e., for the explanation of a diagnosis made by the predictive model. Additionally, model-based taxonomy examines XAI methods considering its interaction with the predictive models. Model-specific XAI methods provide explanation for a specific group of predictive models such as deep neural networks.

We use LIME and SHAP in this study since both have made substantial contributions to explainable AI by offering insights into model predictions, thereby increasing transparency and trustworthiness in XAI and specifically in the healthcare domain [39,40,41]. These techniques aim to enlighten the decision-making processes of sophisticated models, either by approximating the decision function of the complex predictive model through a surrogate model or by employing other optimization strategies to provide a global interpretation of feature contributions to the overall prediction. Both methods are model-agnostic, so they can be applied to any predictive model after completion of the training and validation phases (i.e., post hoc). This characteristic enables their application across various models and makes them valuable tools for interpreting complex deep learning algorithms.

3.1.1. LIME—Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations

LIME is an XAI technique designed to explain the predictions of any classifier in an interpretable and faithful manner by approximating the predictive model locally with a linear interpretable model [42]. It involves perturbing the input data and observing the resulting changes in the black-box model’s predictions. A new interpretable model is then trained on this perturbed dataset, with the weights determined by the proximity of the perturbed instances to the instance of interest. The general formula representing LIME is given by Equation (1), where is the local surrogate explanation model for instance x, f is the predictive model to explain, G is the class of interpretable models, is a measure of fidelity, defines the locality around x, and is the complexity of the model g.

3.1.2. SHAP—SHapley Additive exPlanations

SHAP utilizes Shapley values from cooperative game theory to allocate the prediction output of a model to its input features [43]. It provides a consistent and locally accurate measure of feature importance. SHAP values illuminate the prediction of an instance by determining each feature’s contribution to the deviation between the actual prediction and the average prediction across the dataset. Mathematically, the SHAP value for a feature j is expressed as

where N represents the set of all features, S is a subset of features excluding j, f denotes the model function, and is the SHAP value for feature j.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

3.2.1. Basic Error Metrics

Basic error metrics are standard measurements in the quantitative evaluation of the similarity between images. These metrics are commonly used in image processing via pixel-wise comparisons to quantify the difference or error between a reference image and a test image. Furthermore, being easy to use, these metrics provide a straightforward and quantifiable measure of image fidelity [44].

Both Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) are widely applied basic error metrics that assess the pixel-wise discrepancies between two images. These basic metrics are essential tools in contexts, in which precise alignment or similarity of visual content is examined, such as in the evaluation of explanations generated by AI models in visual tasks. MSE calculates the square of the error, thus emphasizing larger or global discrepancies, although its weakness lies in its sensitivity to localized errors [45]. In contrast, MAE provides a linear evaluation, making it more robust against outliers. Therefore, by applying both MSE and MAE as similarity metrics, both global and local perspectives are covered.

3.2.2. Perceptual Quality Metrics

Perceptual quality metrics are designed to quantitatively evaluate the visual quality of an image as perceived by the human eye. Unlike basic error metrics that compute straightforward differences, perceptual quality metrics assess how image quality is affected by various processing techniques, particularly in terms of structural and visual integrity [46]. These metrics are crucial in applications, in which subjective quality of images is significant, such as in multimedia, telecommunications, and medical imaging. In what follows, we elaborate on three perceptual quality metrics that we used in this paper.

Universal Quality Index (UQI) quantifies the degree of distortion in an image [47]. It is a mathematically represented image quality assessment metric that reflects the human visual system. Unlike traditional metrics such as MSE, which primarily focus on pixel-wise differences, UQI is designed to account for perceptual phenomena that are important to human vision. It is designed to improve on traditional methods like MSE, which may not align well with perceived visual quality. UQI specifically addresses three key components that align with the human visual system, i.e., luminance, contrast, and structural information. Luminance measures the average brightness of the images, acknowledging that the human eye is sensitive to changes in light intensity. Contrast evaluates the dynamic range of pixel intensities, capturing how the human eye perceives differences between varying levels of brightness in an image. Structural information considers patterns and textures within the image, reflecting the human eye’s ability to interpret complex shapes and structural patterns.

The formula is given by

where , are the average of , respectively; , are the variance of ; and is the covariance of x and y.

Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) is a method for measuring the similarity between two images considering the human visual system and it is derived from UQI [48].

Similar to UQI, SSIM specifically addresses three aspects of the human visual system, i.e., luminance, contrast, and structural information. Different from UQI, and are used to avoid instability when the averages or variances are close to zero.

The SSIM metric is defined as

Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) quantitatively measures the amount of information fidelity or how much visual information from the reference image is preserved in the test image [49]. Unlike SSIM and UQI, which focus on structural similarity and error visibility, VIF is based on the premise of modeling the human visual system’s extraction of visual information. The VIF metric considers natural image statistics and the inherent inefficiencies in human visual processing to provide a more thorough understanding of perceived image quality.

The VIF metric is defined as

where is the variance of compared images in the i-th subband, and is the noise variance in the i-th subband. The sums are taken over all subbands of the image.

In this context, subbands refer to the components of the image that have been decomposed into different frequency bands using techniques such as wavelet transform. It allows for detailed analysis at various resolutions and frequency ranges.

3.2.3. Statistical Quality Metrics

Statistical quality metrics or mathematical metrics [45] quantify the accuracy and reliability of image processing techniques from a numerical analysis perspective. Unlike perceptual metrics that focus on human visual perception, statistical metrics are grounded in statistical theories and are crucial for tasks that require accurate and strong quantitative evaluation. These metrics mostly based on the pixel by pixel comparisons without focusing on the meaning of these pixels. The purpose of measuring similarity using statistical quality metrics is to provide objective measures of image quality and similarity in a statistical perspective. Such metrics are particularly valuable in fields, in which precise and reproducible results are essential [50]. For our study, three state-of-the-art statistical quality metrics are used as follows:

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) is defined as the ratio between the maximum possible power of a signal and the power of distorting noise that affects the fidelity of its representation [51]. It is most commonly expressed in terms of the logarithmic decibel scale.

where is the maximum possible pixel value of the image. PSNR translates MSE into a log scale to provide a more intuitive understanding of quality relative to the maximum signal power. In addition, it is easy to implement and understand from a mathematical and computational power point of view.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) measures the linear relationship between corresponding pixel values in the context of image quality assessment [52]. This metric is particularly useful for comparing images where proportional local alignment and similarity are crucial [53], such as in satellite imaging, medical imaging, or any application involving temporal changes observed through images.

where and are pixel values from images x and y, respectively; and and are the mean pixel values of images.

Dice Coefficient measures similarity of two sets. It is used to measure the spatial overlap between two images within the image quality assessment perspective [54]. This makes the Dice Coefficient a proper candidate of segmentation accuracy evaluation metric between the binary predicted mask and the ground truth, providing a clear indication of how accurately the algorithm has identified the relevant regions. Since it is specifically designed for binary data, it provides mask-oriented evaluations.

The Dice Coefficient is defined as

where X and Y are the sets of binary attributes of two images or segmentation maps; represents the common number of elements; and and are the sizes of compared sets.

We have selected the widely accepted and applied aforementioned evaluation metrics [55,56,57] to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the changes applied to the predictive models and their explanations.

4. Methodology

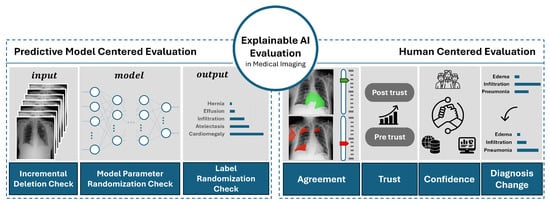

In this paper, we propose and implement a comprehensive evaluation framework for evaluation of XAI in medical imaging. This framework, illustrated in Figure 1, is designed to provide a holistic evaluation methodology by integrating both human-centered and predictive model-centered evaluations. The necessity for such an inclusive framework arises from the increasing demand to ensure that XAI not only aligns with the technical requirements of performance of predictive models but also meets the interpretability and usability requirements of medical professionals.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed XAI evaluation framework for medical imaging. The figure provides a conceptual representation of the methodological components and their relationships.

The evaluation framework consists of two major components, i.e., human-centered evaluation and predictive model-centered evaluation. The integration of both human-centered and predictive model-centered evaluations is essential for a thorough evaluation of XAI in medical imaging. The medical domain presents unique challenges, where consequences of AI-driven decisions are significant. A framework that only considers the technical accuracy of the model without addressing the interpretability and usability for human experts would be insufficient. On the other hand, a framework focusing solely on human factors without ensuring the technical fidelity of the explanations could lead to misinterpretations and erroneous decisions.

The Human-Centered Evaluation focuses on interpretability, trust, and usability of the XAI outputs from the perspective of medical professionals. In the medical field, the end-users of AI systems are often medical doctors and other healthcare providers who rely on the explanations generated by XAI to make informed decisions. Therefore, it is crucial that these explanations are not only accurate but also understandable and actionable by them. This component of the framework assesses metrics such as trust, agreement, and confidence among medical experts, ensuring that the explanations provided by the XAI align with their domain knowledge and clinical expectations.

The Predictive Model-Centered Evaluation examines the fidelity of the XAI outputs to the underlying predictive models. This component is crucial to verify that the explanations accurately reflect the decision-making processes of the models. It is divided into three stages, i.e., evaluation based on input data, predictive model’s output, and predictive model’s internal structure (architecture). Each stage employs various metrics and methods to properly test the correctness, completeness, and contrastivity of the explanations [10]. This part of the framework is mandatory to ensure that the XAI methods are faithful to the predictive model and provide meaningful insights into their functioning.

By including both perspectives with all minimum required components, our proposed framework provides a balanced and comprehensive approach to evaluating XAI.

4.1. Predictive Model-Centered Evaluation

The first part of the evaluation focuses on assessing the faithfulness of XAI results to the explained predictive model. This evaluation employs three key methods, i.e., (i) Model Parameter Randomization Check (MPRC), (ii) Incremental Deletion Check (IDC), and (iii) Label Randomization Check (LRC) [10]. The Model Parameter Randomization Check evaluates how well the explanations reflect the inner structures of the predictive model. The Incremental Deletion Check assesses the XAI results by understanding how explanations react to changes in the input data. Lastly, the Label Randomization Check examines the ability of the explanations to represent the diversity of output data for the predictive model.

4.1.1. Model Parameter Randomization Check (MPRC)

To evaluate the XAI model with respect to the predictive model’s inner decision-making structure, we use the Independent Randomization technique. This is in line with the approach of using saliency maps in [15]. The approach is based on the systematic randomization of model parameters on a per-layer basis which provides the evaluation of the contribution of each layer to the model’s performance and its effect on the explanation independently. We use DenseNet121 as our predictive model. Within the DenseNet121 architecture, nine critical layers are selected for randomization. Our selection spans the first convolutional layer, which initializes the hierarchical feature extraction, through to the primary convolutional layers within each dense block. Additionally, for the first and the last dense blocks, the last convolutional layers were selected to be randomized. The process concludes with the dense layer, the terminal dense layer (Softmax classifier), to check its influence on the decision-making process. By observing changes in the explanations generated after randomizing each layer, whether the XAI method is truly reflective of the model’s underlying mechanisms can be determined.

It is important to note that after each layer randomization, the model was not re-trained. Instead, the randomized weights were directly used for explanation generation, following the sanity-check paradigm of Adebayo et al. [15]. This ensures that the analysis isolates the sensitivity of explanations to structural perturbations within the same trained model rather than performance recovery through retraining.

To evaluate differences between the original predictive model and the model with a selected randomized layer, we select different image quality metrics such as basic error metrics (i.e., MSE and MAE), perceptual quality metrics (i.e., SSIM, UQI, and VIF), and statistical metrics (i.e., PSNR, PCC, and Dice Coefficient). Each metric is chosen to provide a multifaceted understanding of the explanations generated by the XAI model. All of these image quality metrics are examined and applied in medical image processing studies such as [58,59].

Algorithm 1 represents the procedure of MPRC, where S represents the randomly selected samples for cross-validation, L stands for the identified layers to randomize, and M holds metrics to compare these randomized layers explanations and the original layer explanations. Our XAI methods used, i.e., LIME and SHAP, are stored in X. m represents the predictive model, which, as mentioned previously, is DenseNet121 in this study. represents the original explanations generated by the original model () and similarly, represents the randomized explanation generated by randomized model () with the corresponding layer l. All results are stored in R, which is returned by the procedure at the end.

| Algorithm 1 Model Parameter Randomization Check for XAI Methods |

|

4.1.2. Incremental Deletion Check (IDC)

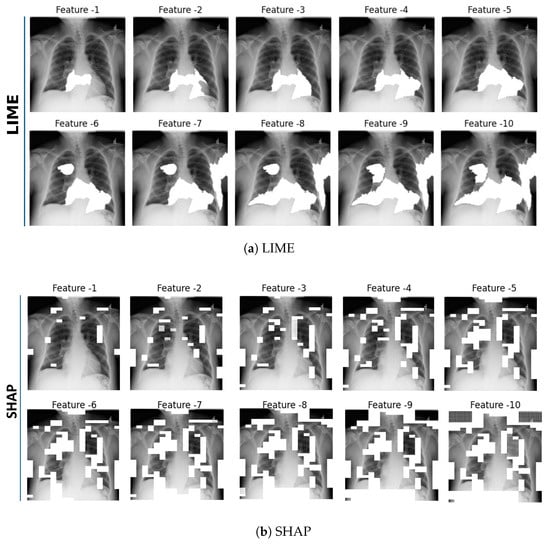

This approach aims to evaluate the correctness of explanations generated by XAI methods from the perspective of input data manipulation. Initially, explanations for a given predictive model are generated using both LIME and SHAP for each X-ray scan sample. Through these explanations, the top 10 most influential features as super-pixels for LIME or the grid regions for SHAP are identified.

Subsequently, these features are incrementally masked with the average pixel value of the current X-ray scan sample. This approach simulates the gradual reduction in feature-specific information available to the predictive model. Each masking operation produces a new version of the input image (see Figure 2a for LIME and Figure 2b for SHAP), which is then fed back to the predictive model. After masking of each feature, the predictive probabilities are recalculated to monitor the changes in the model’s output.

Figure 2.

Incremental Deletion Check—Top 10 features identified by the XAI methods. Subfigure (a) presents features determined by LIME and subfigure (b) by SHAP, with each image sequentially highlighting the key features. For better visualization, white masking was used to highlight the top features, while the mean pixel value color was used for Incremental Deletion.

As discussed in Section 3, although both LIME and SHAP operate as local explainers, their explanation generation mechanisms differ substantially. LIME aggregates importance over super-pixel regions, whereas SHAP assigns attribution scores to individual pixels. Therefore, the spatial overlap between their highlighted regions is not expected to be one-to-one. This difference does not indicate inconsistency but rather arises from the complementary mechanisms through which they capture local evidence. Furthermore, in our previous user study with 97 medical experts [60], LIME showed closer indicative-agreement with experts’ diagnostic reasoning, whereas SHAP achieved slightly lower but comparable performance on contra-indicative agreement. These results suggest that LIME explanations more closely reflect the supportive diagnostic cues used by clinicians, while SHAP captures overlapping but less emphasized contra-indicative cues. Hence, both methods provide valid yet complementary insights into the model’s decision-making behavior.

The method for identifying the top 10 features differs between LIME and SHAP, reflecting the distinct nature of their explanations. For LIME, top features are determined by the weights assigned in the linear surrogate model, which locally approximates the behavior of the underlying predictive model. Mathematically, this is represented by sorting the absolute values of the coefficients in the linear model. Features corresponding to the highest absolute coefficients are considered as the most influential features, identifying them as critical super-pixel groups in the explanation [42].

In contrast to LIME, identifying the top 10 features in SHAP is not as straightforward. This is because SHAP does not provide the ranking of the features. Instead, each feature is evaluated individually based on its SHAP values [43]. Thus, selecting the top 10 features directly from SHAP values does not typically align with a grouped feature approach. In our methodology employed to identify and visualize the top features using SHAP values, we begin by defining evenly spaced percentiles that capture a comprehensive distribution of SHAP values. Specifically, for n features, percentiles are calculated as follows:

Subsequently, the visualization of these features is conducted by generating binary masks for the base image, with each mask M constructed such that

where V represents the matrix of SHAP values for the image and denotes pixel coordinates. The mask is then overlaid on the base image using a mask color C, calculated as the average pixel value of the base image, to vanish areas under the mask. The procedure is shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Identify Top Features from SHAP Values |

|

4.1.3. Label Randomization Check (LRC)

The purpose of LRC is to evaluate the target discriminativeness of the explanations provided by XAI methods. By examining whether the explanations change in response to the randomization of labels, the reliability and meaningfulness of the explanations can be inferred. This method is based on the methodology introduced by [15], which serves as a crucial sanity check for evaluating the discriminative power and reliability of explainable AI (XAI) methods. This technique grounded disrupting the natural correlation between input data and output labels by randomizing the labels of the dataset. Once the labels are randomized, the predictive model is re-trained on this altered dataset, forcing the model to learn these randomized labels.

After the model has been re-trained on the randomized labels, explanations are generated as a reflection of the re-trained model. The core idea here is to compare these explanations with those generated from the original, correctly labeled data. The expectation is that the explanations should show significant differences, thereby reflecting the model’s dependency on the specific input–output mappings.

If the explanations remain the same or show minimal change with respect to the label randomization, this would indicate that the XAI method is not effectively capturing the discriminative features of the model. Conversely, significant changes in the explanations would suggest that the XAI method is appropriately sensitive to the input–output relationships.

4.2. Human-Centered Evaluation

To assess usability of AI and to construct trustworthiness, it is essential to incorporate the medical experts’ perspective through human-centered evaluation. As human-centered evaluation is a crucial part of XAI evaluation, we designed a user study to understand how medical experts perceive AI and its reasoning capabilities when provided with XAI explanations.

4.2.1. User Study Design

To compare the effect of different XAI methods on the perspectives of medical experts, we conducted a randomized controlled trial involving participants from three distinct groups, i.e., (i) group receiving LIME explanations, (ii) group receiving SHAP explanations, and (iii) a control group receiving no explanations. Before beginning the data collection, a power analysis was performed to determine the minimum sample size required for each group to achieve adequate statistical power. Using an alpha level () of to control for Type-I errors, the power analysis indicated that at least 30 participants per group would be needed to achieve 80% statistical power. This analysis ensured that our study could reliably detect significant effects of the XAI interventions on the diagnostic decisions of the participants.

This user study was conducted with ethical approval, and informed consent was collected from all participants prior to their involvement. Participants were randomly assigned to experimental groups afterwards (LIME, SHAP, or Control). The study was completed online with an average duration of approximately 14 min per participant. Demographically, the 97 participants encompassed diverse expertise levels, including medical students, general practitioners, specialty trainees, and specialists to ensure a wide-ranging representation of medical expertise. Detailed demographic distributions and extensive analyses, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, the participant recruitment process, and explicit measurements of dependent variables such as trust, confidence, and agreement, are comprehensively described in our previous work [60].

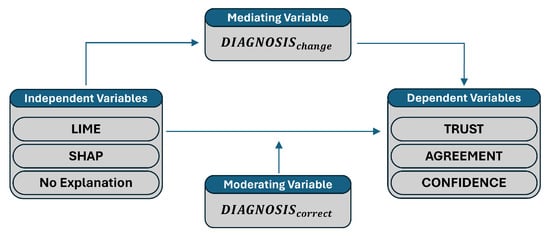

Variables of the study were selected in such a way to explore the impact of different XAI methods on medical experts’ diagnostic decision-making. The independent variables are groups (i.e., LIME group, SHAP group, and No XAI group), which we aim to compare with each other. The dependent variables (i.e., trust, agreement, and confidence) are meant to assess the impact of the XAI methods on the participants perception of various aspects of XAI. The moderating variable (i.e., ) is included to investigate how the correctness of the initial diagnosis is affected by the independent variables and what the influence is of this effect on the dependent variables. Finally, the mediating variable (i.e., ) is used to explore potential mechanisms, through which the independent variables influence the dependent variables. Figure 3 is an overview of the user study variables representing the relationships among the independent, mediating, moderating, and dependent variables. Therefore, the presence of an explanation may lead to a change in diagnosis, which affects the participants’ trust, agreement, and confidence. Moreover, the correctness of the initial diagnosis can influence the extent to which the explanations affect trust, agreement, and confidence.

Figure 3.

An overview of variables relationships in the user study.

Each variable used in the study is defined as follows:

- Independent variables:

- –

- : Participants provided with LIME explanations.

- –

- : Participants provided with SHAP explanations.

- –

- : Participants not exposed to any XAI explanations (i.e., control group).

- Dependent variables:

- –

- : Trust in AI before the experiment begins.

- –

- : Trust in AI after seeing the explanations.

- –

- : Agreement on indicative regions as identified by the AI.

- –

- : Agreement on contra-indicative regions as identified by the AI.

- –

- : Confidence on the diagnosis after seeing explanations.

- Mediating variable:

- –

- : Indicates if there was a change in diagnosis after AI explanation (it is a binary variable: changed, not changed).

- Moderating variables:

- –

- : Indicates if the initial diagnosis matches the ground truth (it is a binary variable: correct, not correct).

The user study in each group starts with the introduction containing the purpose of the study and the expectations from the participants. Basically, the participants are asked to diagnose an X-ray scan sample on 14 chest disorders. In order to avoid possible dropouts, it was carefully indicated to the participants that the purpose of the study was not to test their knowledge. The first question was about participants’ initial trust levels (). Therefore, we aimed to gather a baseline for trust in the AI in general and its ability in terms of correct diagnostics. Since this question was answered at the beginning of the study, it reflects an unbiased trust measure from medical professionals. After answering the trust question, participants were asked to diagnose the provided chest X-ray scan sample (). At this point, with respect to their diagnosis, the generated explanation related to this disorder was provided. Consequently, the participants were asked whether the provided explanation matched their reasoning. The purpose of this question was to measure participants’ indicative () and contra-indicative() agreement with the provided explanations (in this context, the term indicative refers to explanation regions that support the predictive model’s diagnosis (i.e., evidence for the condition), whereas contra-indicative refers to regions that contradict the prediction (i.e., evidence against the condition). This mapping establishes a natural bridge between clinical interpretation and AI explanations, as both rely on identifying supportive and unsupportive evidence when forming diagnostic conclusions.). Afterward, the AI’s judgment was provided to the participants who had already seen its explanation in the previous question and they were asked to diagnose the sample again (). The purpose of this step was to check whether AI’s reasoning affected their decision. Similarly, the trust question () was asked to measure the change in trust. As a support of these measurements, the participants were asked whether their confidence in diagnosis has been affected after seeing AI’s reasoning ().

For each X-ray scan, participants were given the option to diagnose based on a set of possible diseases or to select “None/Not possible to diagnose” if they believed that a diagnosis could not be determined or the listed conditions were not applicable. If this option was selected, participants were directed to a new X-ray scan, ensuring that every participant engaged with a diagnosable case, thereby preserving the study’s integrity. Up to three attempts with different X-ray samples (question groups 1–3) were allowed to accommodate varying levels of diagnostic clarity. Each X-ray sample in each group was carefully selected based on similar levels of diagnostic difficulty, which were determined by their predictive accuracy and ground truths, which were generated by radiologists [61]. This process was designed to minimize variability in diagnostic difficulty across the samples.

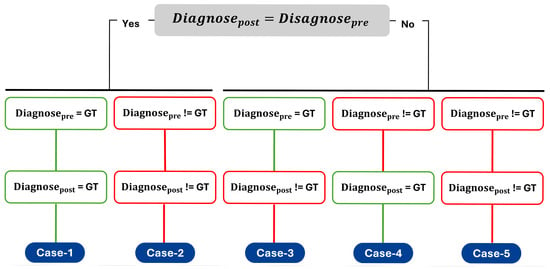

The design of the user study was based on evaluation of trust, agreement, and the confidence changes with respect to the provided explanations. However, these self-reported measures can be subjective and it should be complemented by the objective performance metrics [62]. Therefore, diagnostic correctness () and diagnosis change () before and after seeing explanations were included as different cases to categorize and analyse the diagnostic decisions of medical experts. Here, refers to the correctness of the diagnosis made by the participant for a given sample and not the correctness of the predictive model’s output. To isolate the effect of explanations on human decision-making, only samples that were correctly classified by the predictive model were used in the experiments. The diagnostic behaviour of medical experts was structured around five distinct cases, which were defined based on whether the initial diagnosis () and the final diagnosis () matched the ground truth () and whether the diagnosis remained the same or changed after viewing the AI explanations. Figure 4 illustrates this categorization process.

Figure 4.

Possible cases representing participants’ diagnostic decisions before (Diagnosepre) and after (Diagnosepost) viewing model explanations. Green boxes indicate correct diagnoses with respect to the ground truth (GT), while red boxes indicate incorrect diagnoses.

4.2.2. Hypotheses Analysis

In our previous paper, we analysed the hypothesis focusing on the effects of XAI methods on agreement () with AI’s diagnostic reasoning and changes in trust () in their diagnoses towards AI with the effect of providing its reasoning. Additionally, the relationship between participants’ agreement () and trust () was one of the major hypotheses to test within this user study. These hypotheses with the same groups of participants are examined in our previous paper [60].

In this paper, we provide a deeper and more comprehensive analysis of different aspects including how participants’ confidence in their own diagnoses is influenced when AI is accompanied by its reasoning behind the decision (). Additionally, the relationship between participants’ confidence and trust based on the explanations was examined through Hypothesis-2 (). Moreover, the mediating role of diagnosis changes (, ) and the moderating effect of diagnostic correctness (, ) were investigated. The specific hypotheses tested in this study are therefore as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

The XAI methods significantly affect the confidence level of participants in their diagnosis after receiving AI’s reasoning ().

Hypothesis 2.

The confidence level of participants in their diagnosis after AI’s reasoning () significantly affects the change in trust () towards the AI.

Hypothesis 3.

“” mediates the effect of XAI methods on the change in trust () towards AI’s diagnostic ability.

Hypothesis 4.

“” mediates the effect of XAI methods on the agreement () towards AI’s diagnostic ability.

Hypothesis 5.

moderates the effect of XAI methods on the change in trust () towards AI’s diagnostic ability.

Hypothesis 6.

moderates the effect of XAI methods on the change in agreement () towards AI’s diagnostic ability.

5. Experimental Results

We used the publicly available Chest X-Ray dataset from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [61] for the experiments. This dataset includes 112,120 frontal-view X-ray images from 30,805 unique patients, making it one of the largest available chest X-ray datasets. Each image is labeled as belonging to one or more of 14 classes, which include 13 disease classes and a “No Finding” class for images without any of the listed pathologies. The diseases covered range from common to rare chest conditions, such as Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Effusion, Infiltration, Mass, Nodule, Pneumonia, Pneumothorax, Consolidation, Edema, Emphysema, Fibrosis, Pleural Thickening, and Hernia. For our predictive analysis, we employed DenseNet121, a convolutional neural network renowned for its efficiency and accuracy in image classification tasks, particularly in medical imaging [63]. Using TensorFlow’s implementation of DenseNet121, we leveraged a pre-trained model on the NIH Chest X-Ray dataset to boost its predictive performance. The model’s performance was evaluated using accuracy and Area Under the Curve (AUC) metrics for each label, achieving a mean AUC of 0.80121 and a mean accuracy of 0.70983. These results indicate that the model achieved an acceptable level of predictive performance, making it a suitable candidate for explanation through XAI methods.

For SHAP, we used the Kernel SHAP implementation. Both LIME and SHAP function as surrogate models to approximate the predictions of the original complex black-box model. To ensure a robust analysis and to facilitate a fair comparison between LIME and SHAP, we set the number of samples parameter to 1000 for both methods. This aligns the experimental conditions for each method and provides a solid foundation for comparing their effectiveness in making the model’s decisions interpretable.

5.1. Predictive Model-Centered Evaluation Results

5.1.1. MPRC Results

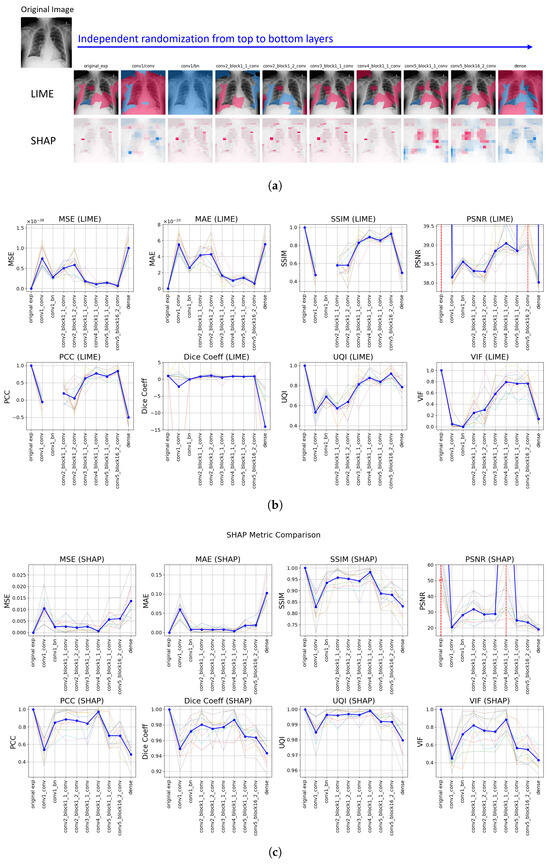

After MPRC was applied to all specified layers of DenseNet (see Section 4), visual representation of explanations showed that, after almost all of the randomized layers, explanation was affected by this change in the inner structure of the predictive model and different explanations were generated for both LIME and SHAP. In Figure 5a, LIME explanations provided significantly different explanations for the first convolutional layer and the last (dense) layer were randomized, which is expected since the early and the late layers in a convolutional neural network capture essential features and class-discriminative information, respectively. Therefore, after the first convolutional layer randomization, the explanation was completely different than the original explanation. Moreover, randomizing the dense layer caused both LIME and SHAP to produce explanations that were almost the inverse of the original explanations. Since the model’s predictions are heavily contingent on this layer’s weights, any perturbation significantly alters the decision boundary. Therefore, these outcomes underscore that both LIME and SHAP are indeed reflective of the internal structure of the model they explain and demonstrate robustness to modifications within it.

Figure 5.

Model Parameter Randomization Check Results: (a) Visual representation of explanations generated by LIME (top) and SHAP (bottom) across layers from top to bottom; pink denotes supportive (positive) and blue denotes non-supportive (negative) explanations. (b,c) Comparative analysis of distance metrics for LIME and SHAP, respectively. Faint background lines represent individual sample results, to show variability across runs, while the solid blue line indicates the mean trend. Red dashed vertical lines mark layers where infinite values occurred.

The recorded changes for the randomization of convolutional layers within dense blocks are not as significant as the changes observed in other layers. In the same figure (see Figure 5), similar changes were observed for most of the metrics for SHAP, specifically in the first and the last layer randomization. However, SHAP starts to generate significantly different explanations after the convolutional layer of the 4th dense block is randomized. For LIME, through the last layers, the changes are not as significant as SHAP but in the latest layer, the highest change was recorded. Therefore, SHAP is more sensitive through the changes on last layers while LIME is more sensitive for the changes on the latest layer. This difference may be caused by the distinct mechanisms of the two XAI methods. LIME’s linear approximation may not capture the complexities introduced by changes in the deeper layers as effectively as SHAP, which computes Shapley values and provides a more granular attribution across all input features. There is a remarkably uniform explanation for LIME in the batch normalization layer’s randomization, which indicates lack of differentiation in feature importance and leading uniformity in the explanation.

In addition to providing visual changes on explanations, different image quality metrics were calculated between the original explanations and randomized explanations with respect to the layers. Figure 5b and Figure 5c represent the LIME and SHAP results, respectively, for the comparative analysis of applied distance metrics (in other words, image quality metrics for MPRC). The first value in all of the plots is the baseline value, which indicates the explanation is the same. For MSE and MAE, this value is 0, so the higher values indicate the more different explanations than the original explanation. It can be seen that it is 1 for SSIM, SCC, Dice Coefficient, UQI, and VIF. Finally, it is ∞ for PSNR. Each line chart visualizes the results of 10 samples and the ticker line represents the average for all of them as a final result of the evaluation. For both methods, significant fluctuations can be observed in the metrics across successive randomizations, indicating how each explanation method reacts to modifications within the model’s structure.

For LIME (see Figure 5b), the basic error metrics (MSE and MAE) demonstrated large variations, suggesting sensitivity to changes in model parameters. SHAP’s results (see Figure 5c) illustrated less fluctuation in basic error metrics compared to LIME, which may indicate a lower robustness of SHAP explanations against internal model changes. The perceptual quality metrics (SSIM, UQI, and VIF) showed variability in different layer randomization; specifically, SSIM fluctuated more in the initial layers for LIME, whereas it was more variable in the last layers for SHAP. This indicates that the perceptual distinction is higher in the initial layers for LIME but the last four layers’ randomization provided higher perceptual distinction for SHAP. Additionally, SHAP shows sharper fluctuations for the first or the last few layers than the randomization of intermediate layers. For LIME, a variety of fluctuations for the intermediate layers was recorded, especially when UQI results are considered. Given that the first and the last layers are more influential in the decisions of the predictive model, SHAP’s outputs are closer to the expected outcomes. Since a uniform explanation was generated by LIME on batch normalization randomization, SSIM and SCC failed to compute the results (yielding values due to division by zero). Finally, for the statistical metrics (i.e., PSNR, SCC, and Dice Coefficient), SHAP’s PSNR values showed less degradation compared to LIME when key layers were randomized, suggesting that SHAP explanations are more resilient to noise induced by changes in model architecture. LIME produced the same explanation as the original explanation on the 9th layer’s randomization; however, for SHAP, this was recorded for the 7th layer. After those layers, the similarity drastically decreased for both methods. While both methods showed decreases in SCC following layer alterations, SHAP’s explanations tended to retain higher correlation levels, indicating a stronger preservation of rank-order relationships. The Dice Coefficient for SHAP remained closer to initial levels than LIME’s across randomization, reflecting the difference in explanation changes on binary masks. Despite the interpretation of differences in metrics, both LIME and SHAP exhibited fluctuations across all metrics, which highlights that both methods are sensitive to modifications in the predictive model’s structure and thus reflect the inner decision-making mechanism of the predictive model in their explanations.

5.1.2. IDC Results

The methodology described in Section 4 was applied to conduct the input-based evaluation of the explanations generated by LIME and SHAP. Initially, the changes in the predicted top feature were monitored after each sequential feature deletion. Features were deleted one by one until the top 10 features had been removed, and the impact on the predictive model’s accuracy with the predicted label was examined. In the experiments, 10 different data samples and their corresponding explanations for XAI methods were used to reduce the probability of randomness.

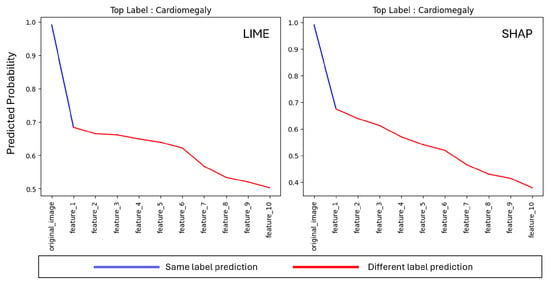

Figure 6 illustrates average label changes by providing different colors on the predicted probability line in charts. Feature-1 is the top feature identified by the XAI method as the most important feature for the predictive model’s prediction and it goes through Feature-10 by reducing its importance. As it can be seen, immediately after the most important feature is deleted, the prediction of the model becomes different (i.e., top label’s probability becomes lower than the other labels) for both LIME and SHAP. This demonstrates that both LIME and SHAP are effective in detecting top features that are crucial to the predictive model’s decision-making behavior.

Figure 6.

Incremental Deletion average label prediction change for top 10 features on LIME and SHAP.

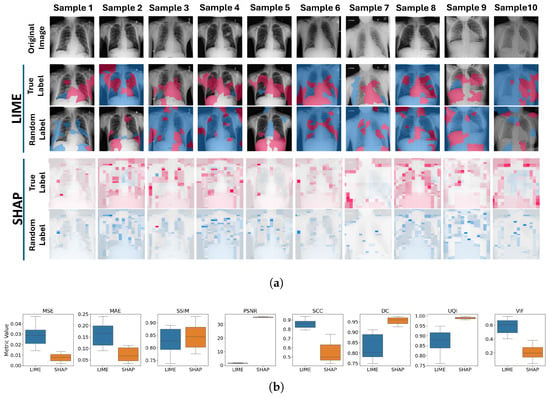

To monitor the changes on the predictive accuracy of the model with respect to IDC, top 5 predicted labels (i.e., Cardiomegaly, Effusion, Infiltration, Nodule, and Pneumothorax) and their corresponding accuracy change are illustrated in Figure 7. The results represent the changes on 10 different data samples to enhance the robustness of the results. All selected samples share Cardiomegaly as the ground truth label to ensure comparability across cases and to isolate model behavior under the same clinical condition. Average accuracy change is represented by the bold dark blue line in charts and all data sample results can still be seen in the charts in faded lines.

Figure 7.

Impact of Incremental Feature Deletion on top 5 label accuracy, as ranked by feature importance according to XAI methods. Each line chart displays transparent lines showing results from individual runs and a bold dark blue line representing the computed mean, indicating the typical response of the algorithm across all samples.

For both XAI methods, a significant initial decrease in predictive probability is observed when the most important feature, designated as Feature-1, was removed. This effect is most pronounced in the condition of Cardiomegaly, underscoring its importance as the top predicted label and highlighting the dependency of the predictive model on this key feature. As further features are incrementally removed, a consistent decline in prediction accuracy continued, validating the effectiveness of both LIME and SHAP in identifying critical features essential for accurate model predictions. On the other hand, there was a significant increase on the predictive accuracy after the most important feature drop for third (Infiltration), forth (Nodule), and the fifth (Pneumothorax) predicted labels. This supports the changes on the first two top labels (i.e., Cardiomegaly and Effusion) since the prediction of the model changes after removing the top feature. Therefore, results highlight the specificity and discriminative power of the identified features by both LIME and SHAP.

This experiment was designed as a controlled analysis rather than a random-sample evaluation, which allows a focused visualization of model behavior under a consistent diagnostic condition (Cardiomegaly). Therefore, the visualization reflects both per-sample variability and aggregate trends, while more importantly emphasizing the model’s response to the ground-truth class.

5.1.3. LRC Results

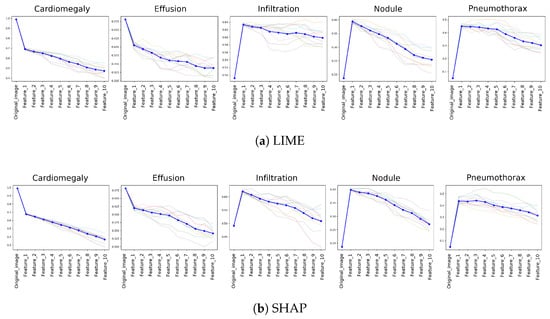

The methodology described in Section 4 was implemented using 10 different data samples. Figure 8a is the visual representation of five samples and their corresponding explanations generated by LIME and SHAP. The top row shows the original images, followed by the explanations with true labels, and the explanations with randomized labels for LIME and SHAP, respectively.

Figure 8.

Label Randomization Check Results. (a) Visual representation of the explanations before and after LRC between the original explanations and those generated with randomized labels for LIME (top) and SHAP (bottom) across ten data samples. Pink color represents the supportive (positive) and blue color represents the non-supportive (negative) explanations. (b) LRC results via box plots showing the distribution of LIME and SHAP results across eight different metrics.

For LIME, significant differences can be observed between the explanations generated with true and randomized labels. The areas highlighted in the explanations changed notably, indicating that LIME is sensitive to label randomization and effectively reflects the model’s reliance on specific input–output mappings. This demonstrates LIME’s ability to capture discriminative features in the model. While LIME identifies certain regions as supportive in the original explanations, these regions can become unsupportive or show reduced support in the randomized label explanations. However, LIME did not always show a direct reversal of support; rather, it reflected a change in the importance and nature of the regions.

For SHAP, the differences are also apparent, and the changes are more structured compared to LIME. In SHAP, the strongest supportive regions identified in the original explanations were often marked as the strongest unsupportive regions after label randomization. This indicates a more pronounced shift, suggesting that SHAP is highly sensitive to the underlying model’s changes and reflects the inversions in the model’s learned patterns due to label randomization.

Figure 8b illustrates the comparative analysis of the LRC over eight different image quality metrics for both LIME and SHAP. For MSE and MAE, higher values are observed for LIME compared to SHAP. This indicates that, from the perspective of basic error metrics (straightforward pixel-wise comparison), LIME is more responsive to changes in model behavior due to randomized labels.

When perceptual quality metrics were examined, SHAP provided higher results for both SSIM and UQI. This suggests that the perceptual structures of the explanations are better preserved after label randomization, so that SHAP explanations are less sensitive to label changes. VIF results show that the LIME provided higher similarity in the fine details and the high-frequency information between the before and after LRC explanations. Given the nature of VIF (see Section 3.2), which focuses on granular details in images, these results are as expected because SHAP explanations show more granular areas after label randomization. LIME, on the other hand, provides more solid areas with changes occurring in larger regions, which results in higher VIF results.

With respect to statistical quality metrics, PSNR results are much higher in SHAP, which indicates the difference between the true label and random label explanations is less pronounced compared to LIME. Therefore, LIME shows a greater reaction on the LRC than SHAP. Similarly, for the DC, SHAP shows higher values, which indicates more similar explanations before and after LRC. Since the DC evaluates binary explanations and most of the random label explanations generated by SHAP are the opposite signed version of the original (true label) explanations, similarity is much higher for SHAP. Finally, PCC indicates higher linear relationship in between true-label and random label explanations for LIME. This is likely due to the presence of solid regions in the explanations.

As a result of this test, both LIME and SHAP showed sensitivity to changes in model behaviour through the altered target of the data. For almost all metrics, LIME demonstrated higher response to the label changes.

A detailed statistical overview of the predictive model-centered tests for robustness is provided in Appendix A.

5.2. Human-Centered Evaluation

Within the human-centered evaluation part of the proposed XAI evaluation framework, a user study is conducted with 97 medical experts. In our previous paper [60], the demographic distribution of the 97 medical expert participants, pre-study analysis, and user study scenario design criteria were provided in detail. Additionally, in our previous user study analysis, we examined the direct group-level effects of XAI methods on medical experts’ agreement and trust through four statistical hypotheses, denoted here as – to distinguish them from the hypotheses introduced in this work:

- : XAI methods significantly affect the level of indicative agreement () between medical experts and the AI’s diagnostic reasoning.

- : XAI methods significantly affect the level of contra-indicative agreement ().

- : XAI methods significantly influence the change in trust () towards the AI’s diagnostic capabilities.

- : The level of agreement between medical experts and the AI’s diagnostic reasoning significantly affects the change in trust ().

Results of these hypothesis tests showed that both LIME and SHAP explanations positively influenced and compared to the control group, while no significant differences were observed for . Also, had a strong correlation with for both LIME and SHAP (LIME has higher), and in the control group, it is less than the others, indicating that providing an explanation has a positive effect on agreement and trust levels. However, for the effect of the XAI explanations on , it was not possible to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that trust levels are not only dependent on providing explanations.

Moreover, to examine the effect of participants’ trust, a question group-based analysis was conducted within the trust analysis. The analysis did not find any significant differences in based on the different question groups.

Although trust and agreement have been analyzed from different perspectives, including across different question groups, these self-reported measures can be subjective and may not fully capture the complete impact of XAI. Therefore, in the present study, we extend this analysis by incorporating moderating () and mediating () variables as objective performance measures to complement the self-reported metrics and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of XAI.

5.2.1. Confidence Analysis ()

The measure reflects how participants’ confidence in their diagnosis changed after being exposed to AI explanations. With respect to the , the existence and variety of the effect of different XAI methods on the was questioned. To test the hypothesis, ANOVA and Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test were applied for the comparative analysis in between groups. The purpose was to check whether different XAI methods have different influence on the or if having and not having explanations makes any difference with respect to participants’ confidence on the diagnosis.

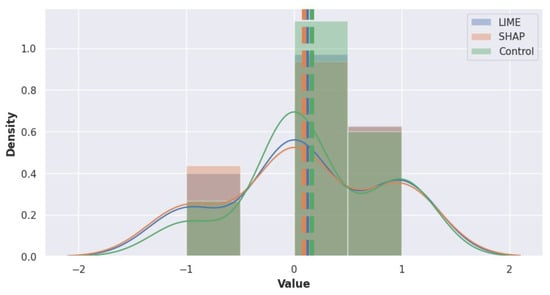

Figure 9 represents the participants’ responses and the group distribution of the . Most of the participants in the three groups indicated that their confidence in their diagnosis was not affected. Since the third group did not receive any explanations, it is hard to say if there is a correlation between having explanations and diagnostic confidence. The bottom plot illustrates the distribution over the three groups. As it can be seen from the distributions, the three groups have quite similar distributions. For the analysis, results were turned into categorical, which is −1: “I am less confident about my first diagnosis”, 0: “My confidence in my first diagnosis is not affected”, and 1: “I am more confident about my first diagnosis”. Therefore, calculated group means values were as follows: LIME = 0.114, SHAP = 0.094, and Control = 0.167. These means suggest slight differences in post-confidence scores across the groups. However, to determine if these differences are statistically significant, we conducted a one-way ANOVA, which resulted in and p-value = 0.916. Given the high p-value, which is greater than the alpha level of 0.05, we failed to reject the null hypothesis (H0). This result indicates that there are no statistically significant differences in post-confidence scores between the groups. Therefore, we conclude that the post-confidence distributions are similar across the three groups. To further explore the potential differences between the groups, we conducted Tukey’s HSD test. The Tukey HSD results show that none of the comparisons between the groups are statistically significant. The adjusted p-values are all above 0.05, and the confidence intervals for the mean differences include zero, further indicating no significant differences.

Figure 9.

Distribution of values within LIME, SHAP, and control groups. The levels are categorized as −1: “I am less confident about my first diagnosis”, 0: “My confidence in my first diagnosis is not affected”, and 1: “I am more confident about my first diagnosis”.

5.2.2. Confidence–Trust Relationship Analysis ()

To examine the relationship between participants’ confidence in their diagnoses after receiving AI explanations and the change in their trust towards the AI, Hypothesis-5 () was formulated. claims that the post-diagnosis confidence levels () significantly impact the change in trust () towards the AI. Therefore, if participants’ confidence has increased over their diagnosis after seeing AI judgment and its reasoning, their level of trust should also increase.

The correlation analysis was applied to all groups via Pearson correlation analysis and regression modeling was utilized to determine the nature and strength of this relationship within each group. No strong correlation between and was found for the three groups as the Pearson correlation was found to be LIME = 0.38, SHAP = −0.24, and Control = 0.43. The strongest correlation was recorded in the Control group and remarkably, in SHAP, a negative correlation was measured. Since results are not quite clear in the correlation analysis to interpret the relationship between and , we performed a regression analysis to test (see Equation (12)). Additionally, regression analysis was applied between the other variables () and to obtain a better insight into this relationship.

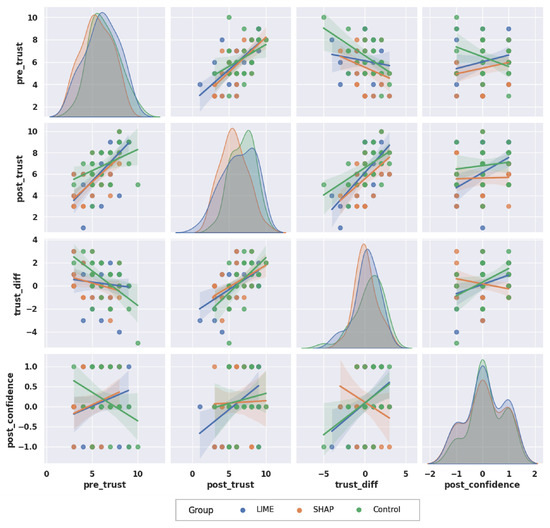

Figure 10 is the pair plot that visualizes the relationships between four variables, i.e., , , , and . Each cell in the matrix represents a scatter plot with a regression line for the respective pair of variables. The diagonal cells show the distribution of each variable across the three groups. The distribution of scores is approximately normal across all groups with slight variations in the mean levels. The distributions are also normal, with LIME and SHAP showing slight higher levels compared to the Control group. The distributions show that most participants have a positive change in trust, especially in the LIME and Control groups. Finally, distributions highlight that most participants reported no change or increase in confidence after receiving the AI explanations. However, more participants in SHAP group reported a decrease in confidence.

Figure 10.

Distribution and correlation of TRUST and CONFIDENCE scores across groups. The distributions for pre_trust, post_trust, trust_diff and post_confidence show how each group responded in terms of trust changes and confidence after explanations. Regression lines indicate the relationships between these variables across the groups.

When scatter plots and regression analysis are examined in Figure 10, a positive correlation between and can be observed across all groups. This indicates the initial trust levels generally influence post-explanation trust levels. The regression lines for the three groups are similar, so the initial trust levels are a consistent predictor of post-trust regardless of the type of explanation provided. With respect to the and relationship, the Control group shows a weak negative correlation while LIME and SHAP groups have weak positive correlations. This indicates that higher might slightly reduce the for the participants who did not receive any AI explanations, but increase it for LIME and SHAP groups. Remarkably, for the relationship between and , the SHAP group has a distinct negative correlation, while the LIME and Control groups show strong positive correlations. This indicates that, for the SHAP group, an increase in trust difference tends to decrease post-confidence levels. By itself, this information seems vague; however, when the case-based analysis was applied (see Section 5.2.5), a remarkable number of participants provided the wrong diagnosis at first and after seeing the AI judgement and its reasoning, they changed their opinion on the diagnosis through to the correct one (Case-4). Therefore, this indicates that participants were not confident about their initial diagnosis and therefore they felt less confident afterward.

5.2.3. Diagnosis Change Analysis (, )

To examine and , we analyzed the mediating role of in the relationship between the independent variable () and the outcomes ( through the direct and indirect way. The performed hypothesis test was based on the methodology proposed by [64]. It is a mediation analysis for multi-categorical independent variables and contains three main steps as the traditional mediation analysis. First, the mediator model was established to examine relationship between the independent variable () and the mediator (). In this established first relationship, the difference from a mediation analysis is multi-categorical values of the independent variables. Since the effect of different categories was to be examined and compared, group was taken as a baseline and the effects of the other two groups were calculated via Equation (13). Then, the outcome model examines the effect of both the independent variable () and mediator () on the dependent variable (either or ) and Equation (14) is the representation of the regression model to examine this relationship over different values of the independent variable. The overall effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is calculated as , where is the total effect of related independent variable value. Similar to , mediator models for other outcomes as and are structured with the same approach.

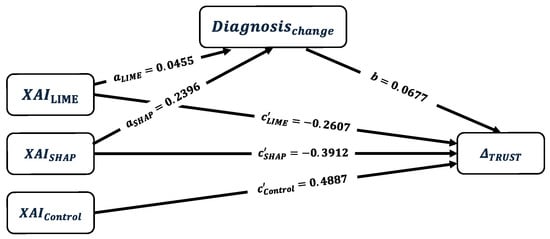

Figure 11 is the path diagram for for the mediation analysis. Calculated coefficients for the mediator model are shown on the corresponding paths (i.e., ). The coefficient to provide the relationship between mediator and the dependent variable (i.e., b) is provided as the estimations of the outcome model with direct effects of the mediating analysis (i.e., ).

Figure 11.

Path diagram of the multi-categorical mediation analysis for the effect of XAI methods (LIME, SHAP, and Control) on through diagnosis change as a mediator with their corresponding estimated coefficients , and . Control group is the baseline group.