1. Introduction

Automating document processing in accountancy (for tax, expense reporting, and auditing) requires extracting semantic data from receipts and invoices. While some tasks need most of the information present on the receipt, i.e., including line items, others only require a subset, namely the supplier’s name, date, tax, and total amount.

Historically, receipt information extraction systems employed template-matching methodologies. This technique relied on the inherent spatial structure of the documents, proving effective only for sources with highly consistent and predictable layouts. Consequently, these methods demonstrated limited generalizability, necessitating the explicit definition of layout parameters for each unseen document source. A substantial advancement occurred with the integration of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which enabled the development of models capable of robustly generalizing across diverse document topologies. More recently, the field has transitioned to multi-modal transformer architectures. These contemporary models integrate a combination of textual, visual, and layout features as input, yielding a significant improvement in overall document-understanding capabilities and establishing the current state of the art in receipt analysis.

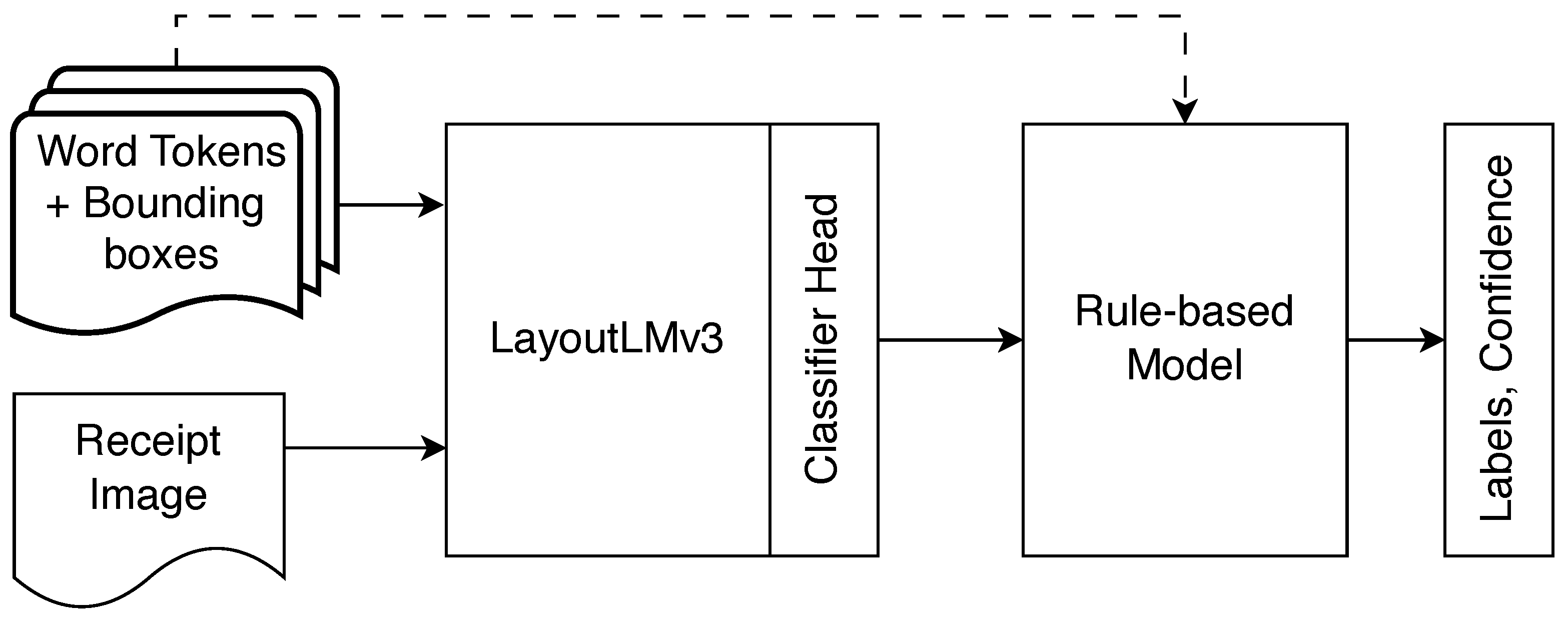

In this work, we are interested in developing a model that extracts all useful information, including line items from thermally printed receipts. The overall architecture and pipeline of the model is illustrated in

Figure 1. The information extraction model consists of the joint use of a pre-trained open-source neural multi-modal transformer (LayoutLMv3 [

1]) and a rule-based model developed as part of this work. The rule-based model is used to improve upon the output from the previous stage (LayoutLM). Potentially, it can also be used as a standalone receipt information extraction system. Following hyperparameter tuning and training of the classifier head, the LayoutLM model on its own achieved an overall F1 score of

on the real-world-receipt test set and an F1 score of

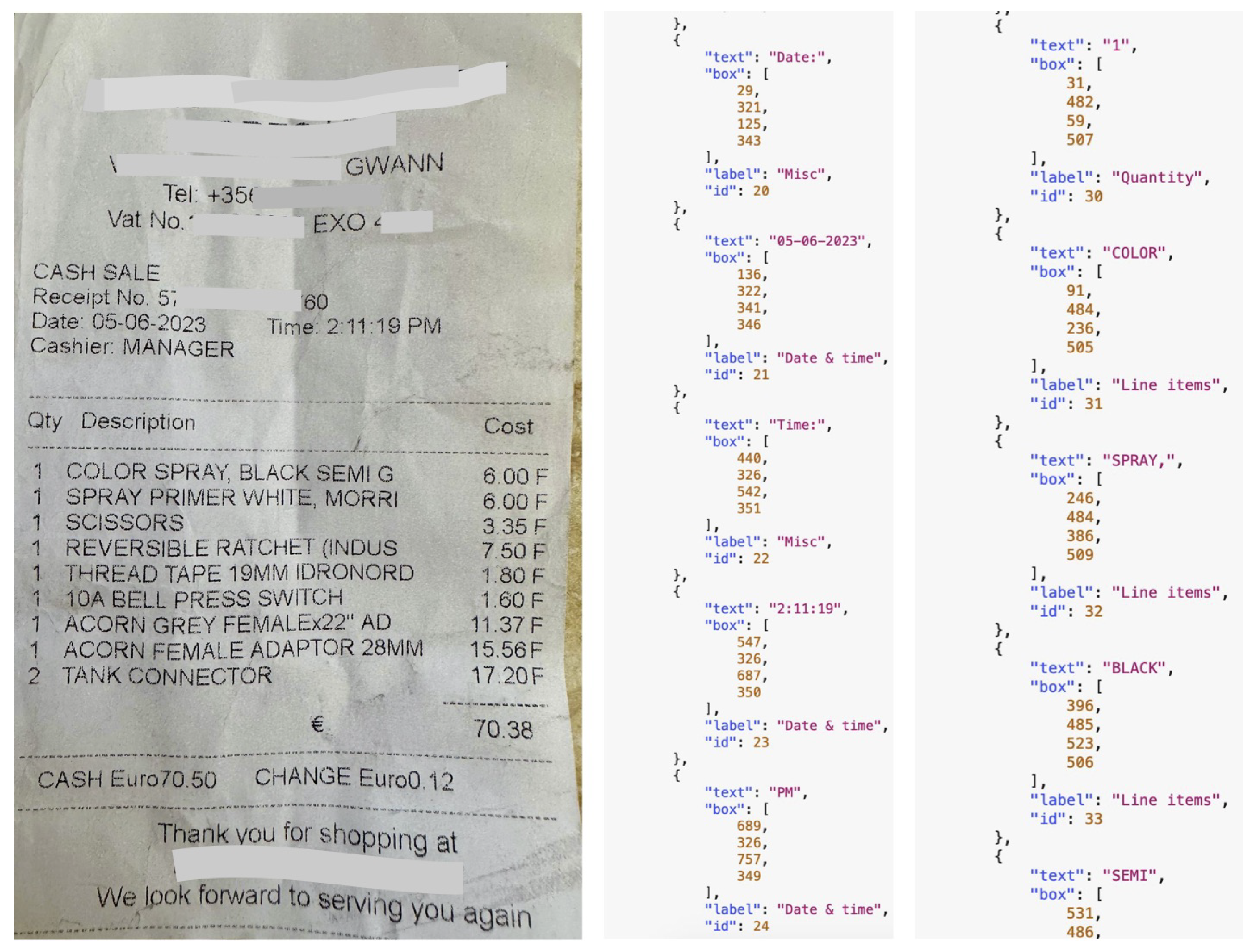

with the addition of the rule-based model. In addition, following a quantitative and qualitative study of a number of options, the DocTR Optical Character Recognition (OCR) model was selected to scan and obtain the bounding boxes and word tokens, and an ablation study of the various combinations of classification models and data was carried out.

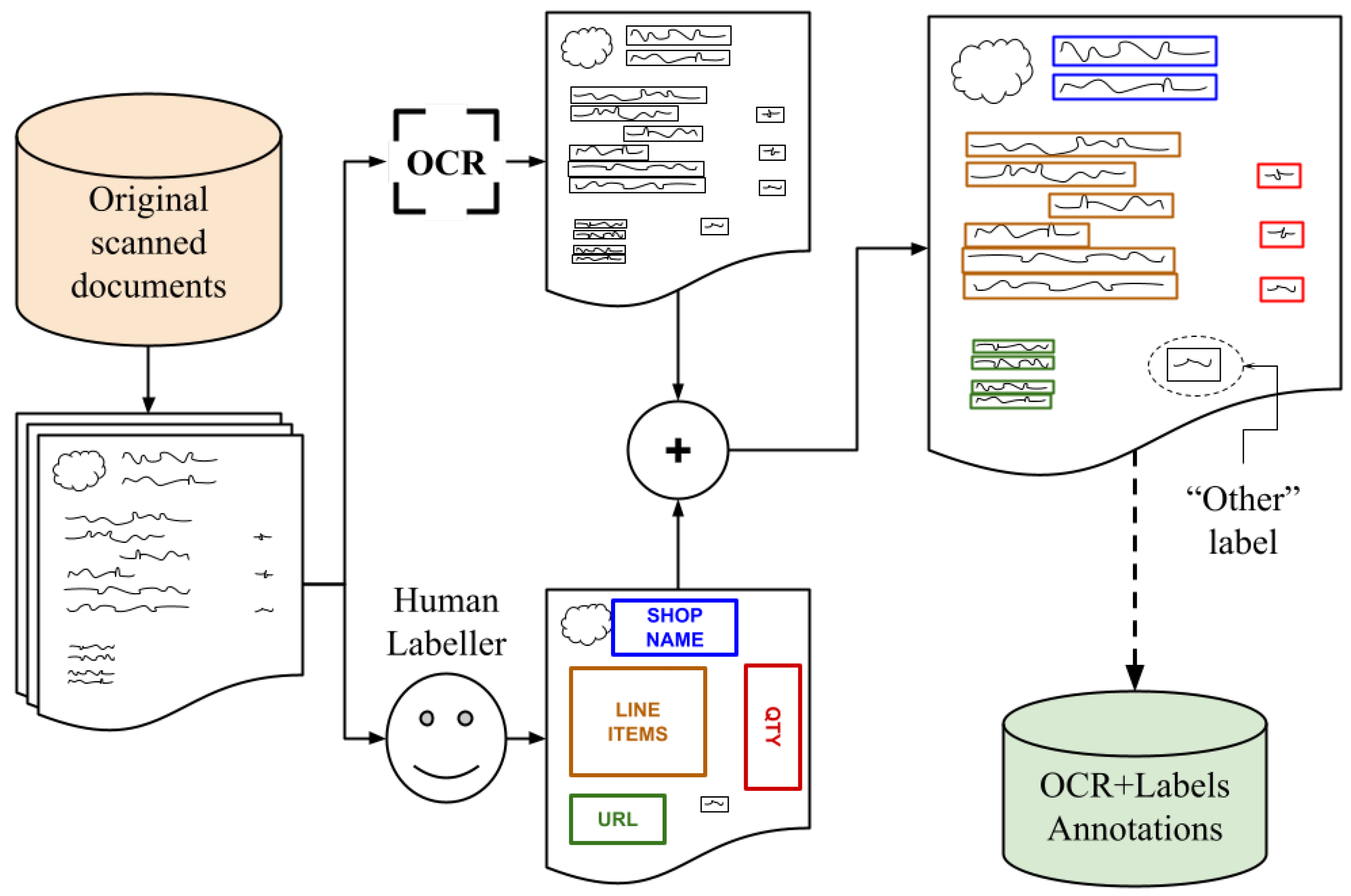

The following is a summary of our contributions; (a) A comprehensively annotated dataset comprising real-world and synthetic receipts was specifically developed for this study. This was necessary since benchmark datasets SROIE (Scanned Receipts Optical Character Recognition and Information Extraction [

2,

3]) and CORD (Consolidated Receipt Dataset [

4]) are either not fully labelled or some items are redacted. (b) The open-source LayoutLMv3 transformer-based multi-modal model was augmented with a classifier model head, which was tuned for classifying textual data into 12 predefined labels pertaining to receipt information (e.g., date, price, name of shop). (c) A manually defined rule-based model was developed and integrated with the multi-modal transformer (LayoutLMv3) model to further improve upon and ‘error correct’ the tokens classified by the LayoutLM model.

This section introduces the receipt information extraction task and outlines the scope and contributions of this work. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Related work is reviewed in

Section 2.

Section 3 and

Section 4 describe the development of the dataset and the selection of the OCR model.

Section 5 and

Section 6 describe the multi-modal transformer and rule-based models. The results are tabulated and discussed in

Section 7, and

Section 8 concludes this paper.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review related work that tackled receipt information extraction tasks. Receipt information extraction tasks require both textual and spatial analyses of documents represented as images. One way to extract information is to manually hard-code rules, an approach taken by the authors of [

5], who used a combination of techniques, such as regular expression matching and spatial search algorithms, in order to extract semantic information from receipts, and the authors of [

6] made use of regular expressions in order to establish a baseline for receipt semantic extraction.

The methods described in [

5] are designed to extract the transaction date and price or total. The system utilizes natural language processing and statistical techniques. More specifically, keywords associated with categories (e.g., “price,” “total,” “amount”) are identified. A spatial search (nearest-neighbor search) is then conducted for text bounding boxes nearest to the keyword to find the associated value. For price parsing, the system selects the keyword–price pair that is the furthest down the page, as this usually represents the total price for a given receipt image. The system correctly identifies the price

of the time when tested on a private test dataset composed of 50 unique receipt images. The results for “transaction date” extraction are not given.

The methods in [

6] define functions based on regular expressions and logic to extract eight categories (date, address, price, tax rate, currency, product name, product price, and product amount) of information from thermally printed receipts. In addition, vendor name is extracted by simply taking the text at the top of the receipt. If it is not the Swedish word for receipt or the text’s length is less than two, then the next one is taken instead. The system is tested on a test set of 90 receipts (the large majority of them being Swedish and not publicly available due to privacy regulations) and achieves an overall F1 score of

(micro-average) and

(macro-average). Some categories achieve high scores (date =

and currency =

), whilst the rules for extracting line item data achieve an overall F1 score of

.

On the other hand, early commercial solutions relied on template methods, where the text and spatial rules are coded for specific documents and, therefore, do not generalize across documents with different layouts and styles. Therefore, learning from data via machine learning models is considered to mitigate the generalization problem. Palm et al. [

7] made use of recurrent neural networks, specifically long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to develop CloudScan, an invoice information extraction system. This system makes use of positional data alongside textual data tokenized as N-grams. The system was trained and tested on 326,471 samples obtained directly from customer feedback and extracts key information only (i.e., total, tax, date, name of shop). The LSTM model achieved an F1 score of 89.1% (88.7% bag-of-words (BoW) baseline model) on seen forms and 84.0% (78.8% BoW) on unseen forms.

Most datasets used for the receipt information extraction task are not publicly available, mainly due to the difficulty in obtaining consent from various data owners. Nevertheless, the Scanned Receipts Optical Character Recognition and Information Extraction (SROIE) dataset [

2,

3] was published for benchmarking purposes. The dataset contains approximately 1000 scanned and labelled receipts split into approximately 600 training/validation and 400 testing examples. However, the labelled entities for this dataset are limited to company name, date, address, and total. The Optical Character Recognition (OCR) results are provided with each image, along with the bounding boxes. A second benchmarking dataset is the Consolidated Receipt Dataset (CORD) [

4], which contains over 11,000 Indonesian receipts collected from shops and restaurants with entity bounding boxes and labels consisting of five superclasses and forty-two subclass labels. This dataset was created to evaluate post-OCR parsing, but it has also been used to evaluate the extraction of semantic information from documents; it also includes some line items. However, only 1000 of the receipts are publicly available, and sensitive information, such as shop names, addresses, and telephone numbers, are redacted. Nonetheless, these two benchmarking datasets stimulated research in receipt information extraction, which followed advances in transformer networks.

The attention mechanisms within large language transformer models, such as the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model [

8], resulted in significant strides in accuracy and semantic extraction from texts. In addition, the pre-training step improved the performance of models characterized by a large number of parameters. When masking is used to implement the pre-training step, the model is trained to predict the next word and next sentence or whether two sentences can appear next to each other in a text document. Although applying BERT directly to the receipt information extraction task results in poor outcomes [

6], various BERT-inspired models have managed to improve the state of the art. One such model is LayoutLM, as proposed by [

9]. The authors observed that existing BERT-based models did not properly take advantage of a document’s rich visual information. This led to the implementation of a 2D positional embedding for each token and an image embedding for the token, along with the standard input representation of text embeddings and position embeddings. The layout features are used alongside the textual features during the pre-training task, while all three features (layout/textual/visual) are used in the downstream task. The pre-training objectives follow a principle similar to that of the masked language model (MLM) used to train BERT. In particular, LayoutLM used a Masked Visual-Language Model (MVLM), where a percentage of text tokens is randomly masked out, and the model is tasked with predicting these tokens based on other text tokens and visual and layout information present in the input. The LayoutLM large model (343 M parameters) achieved an F1 score of 95.2% on the SROIE dataset and 94.6% in the case of the smaller model (113 M parameters).

LayoutLMv2 [

10] introduced an Image–Text-Matching (ITM) objective, in which the model is tasked with predicting whether pairs of cross-modal text and visual and layout information match each other, thus encouraging better semantic relationships to be learned. The F1 scores for the model are 96.25% for the small model (100 M parameters) and 97.81% for the large model (400 M parameters). Another notable pre-training objective is the Word-Patch Alignment (WPA) objective, introduced in LayoutLMv3 [

1], where the model is tasked with predicting whether the corresponding visual patch of a particular text token has been masked. LayoutLMv3 achieved F1 scores of 96.56% (133 M parameters) and 97.46% (368 parameters) on the CORD dataset. In comparison, LayoutLMv2 achieved 94.95% (200 M parameters) and 96.01% (426 M parameters) on the same CORD dataset.

Along with general improvements in the architectures of the encoder networks of these document-understanding models, pre-training objectives were key to increasing accuracy across the board. The LAMBERT model [

11] characterised in 125 M parameters and pre-trained on a dataset of size 75 M achieved 96.93% on SROIE (98.17% on the leaderboard) and 94.41% on the CORD dataset. In comparison, the LayoutLM models are pre-trained on a smaller dataset of 11M examples. On the other hand, GraphDoc [

12] is a multi-modal graph attention-based model, where a graph structure is injected into the attention mechanism to form a graph attention layer such that each input node only attends to its neighbourhoods. Pre-training is carried out on a masked sentence modelling task using a very small dataset (320 k), and the model achieved an F1 score of 98.45% on SROIE and 94.41% on the CORD datasets.

More recently, more datasets have been made publicly available [

13,

14], additional model iterations have been proposed [

15,

16,

17], and general purpose multi-modal large language models have been benchmarked on receipt information extraction tasks [

13,

18].

AMuRD [

13] is a multilingual (English and Arabic) receipt dataset (47,720 examples in total) that has been human-annotated with key information and line items, and in addition, it includes labels pertaining to categories of product description. RealKIE [

14] consists of five novel datasets for key information extraction in enterprise documents and includes 370 labelled Federal Communication Commission (FCC) invoices that contain cost information from television advertisements.

DocGraphLM, proposed in [

15], combines LayoutLMv3 with graph semantics. This is achieved with a joint encoder architecture and a link prediction approach to reconstruct document graphs. The model achieved an F1 score of

on the CORD dataset. DocExtractNet [

16] integrates image enhancement, a precision-hinting strategy, and a cross-modal fusion module to improve the performance of the pre-trained LayoutLMv3 model in information extraction tasks. The resulting model achieved an F1 score of

on the CORD dataset, up from

on the baseline LayoutLMv3. In [

17], the authors combine multi-modal alignment and sequence modelling by integrating CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) and a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) to achieve a lightweight and computationally efficient model. The framework achieves

on the CORD dataset with a model size of 18 M and is four times faster (when edge-deployed) than LayoutLMv3 (model size of 410 MB and F1 =

on CORD).

General-purpose multi-modal large language models have been studied in [

13], where the authors finetuned a 7 B parameter LLaMA V1 in the information extraction task and achieved an F1 score of

on the AMuRD dataset. In [

18], eight multi-modal large language models from the GPT-5 (

https://platform.openai.com/docs/models, accessed on 21 October 2025), Gemini 2.5 (

https://deepmind.google/technologies/gemini/, accessed on 21 October 2025), and Gemma 3 (

https://ai.google.dev/gemma, accessed on 21 October 2025) families are benchmarked on the information extraction task using zero-shot prompting. Gemini 2.5 Pro achieved the highest accuracy score:

on the SROIE dataset (scanned receipts) and

on the Donut [

19] synthetic dataset (clean invoices).

In summary, general-purpose LLMs underperform when compared to specialized document analysis models, and so far, most recent research is on further specializing transformer-based document analysis models for receipt information extraction tasks and, to a lesser extent, developing models that are less demanding on computing resources.

4. Optical Character Recognition Models

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is a fundamental technology in computer vision and document analysis that aims to automatically detect and recognize textual information from images or videos. Traditionally, OCR systems were designed for scanned documents with clean, printed, and horizontally aligned text [

20]. Classical engines such as Tesseract and its modern Python interface, PyTesseract [

20], became widely adopted for document digitization and layout understanding, providing robust rule-based and LSTM-based recognition for machine-printed text.

However, with the proliferation of scene text in natural environments (such as street signs, advertisements, and product packaging), modern OCR has evolved to handle a wide variety of complex scenarios characterized by uneven illumination, background clutter, distortions, and diverse font styles [

21]. Deep learning frameworks, such as EasyOCR [

22] and DocTR [

23], have emerged as general-purpose OCR toolkits, leveraging convolutional neural networks and transformer-based architectures to detect and recognize text across multiple languages and irregular layouts.

In recent years, scene text detection and recognition have attracted significant research attention due to their importance in applications such as autonomous driving, assistive reading systems, and visual question-answering [

24,

25]. A major challenge in this domain is the arbitrary shapes of text regions, which often appear in curved, rotated, or irregular layouts rather than the traditional horizontal orientation. Conventional bounding-box-based detectors struggle to localize such complex shapes precisely, motivating the development of new representations and architectures tailored to irregular text [

26].

To address these challenges, numerous deep learning-based methods have been proposed for arbitrary-shaped text detection and end-to-end recognition. Early approaches extended axis-aligned detectors by adopting rotated or quadrilateral bounding boxes [

27,

28], but these methods often failed to capture curved text boundaries. More recent innovations introduced segmentation-based and contour-based frameworks, which model text regions at the pixel or instance level. For instance, Text Growing on Leaf proposed a flexible region-growing mechanism to progressively expand text regions, effectively adapting to arbitrary geometries [

29]. Zoom Text Detector employed a coarse-to-fine strategy that dynamically refines text boundaries with high precision [

30]. Meanwhile, Concentric Mask-Based Arbitrary-Shaped Text Detection introduced a novel mask representation to describe complex text contours efficiently [

31].

End-to-end frameworks, such as text-spotting transformers [

32], SwinTextSpotter [

33], and related transformer-based architectures, have further unified text detection and recognition within a single trainable pipeline. These methods leverage self-attention mechanisms and multi-scale feature fusion to jointly localize and decode text, offering robustness against scale variation and irregular shapes. The integration of transformer backbones and hierarchical vision architectures, such as the Swin Transformer [

34], has significantly advanced the performance of arbitrary-shaped text-spotting benchmarks.

Despite these advances, several open challenges remain. While lightweight OCR libraries, such as PyTesseract, DocTR, and EasyOCR, offer accessibility and broad language coverage, they generally underperform compared to state-of-the-art research models on complex scene text benchmarks. Persistent issues include robustness under extreme distortions, the efficient processing of high-resolution images, and generalization to unseen text styles and languages [

35]. Ongoing research continues to explore more adaptive representations, efficient transformer-based models, and multi-modal learning paradigms that integrate textual, visual, and contextual cues for holistic text understanding in the wild [

35,

36].

Given that thermal receipt OCR, which is considered in this paper, is a structured, semi-regular text recognition problem, it can potentially be well tackled by DocTR, which can handle mild distortions and noise. On the other hand, arbitrary-shaped text models would be more suitable for complex scenarios involving curved text, e.g., logos, urban street scenery, etc., and would have higher associated computational costs.

4.1. EasyOCR, PyTessaract, and DocTR Models

EasyOCR, developed on the PyTorch deep learning framework, leverages the power of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for spatial feature extraction and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for modelling text sequences. EasyOCR supports the use of graphics processing units (GPUs) out of the box, and this feature makes it well-suited for OCR tasks, where computation speed is required. In addition, it supports more than 80 languages, although accuracy varies across languages.

PyTesseract is a Python binding to Google’s Tesseract OCR engine [

20]. Tesseract employs a composite approach, which combines traditional rule-based methods with modern long short-term memory (LSTM) networks for character recognition. The architecture is modular, thus enabling various configurations and extensions, although customization is often seen as a feature more relevant to those looking to adapt PyTesseract to specific needs, such as improving the accuracy of specific fonts. One notable drawback is that it is not equipped with GPU capabilities outside of the box. However, it does not require high computational costs when compared to deep learning and transformer-based methods.

DocTR [

23] is a transformer-based OCR that exhibits significant performance improvements compared to other state-of-the-art OCR technologies. DocTR employs geometric unwarping and illumination transformers, which relax the need for image pre-processing; this is key to the real-world effectiveness of receipt labelling systems (which will most likely deal with many low-quality images).

4.2. Comparison of OCR Models

There are limited studies comparing OCR models in terms of an accuracy metric in the academic literature. The studies in [

37,

38] compare OCR models on medical records that take the form of well-organized medium–high quality forms. In [

38], various image pre-processing techniques are applied to scanned medical documents (images), and the OCR engines are compared with or without pre-processing techniques on the basis of average accuracy based on the Levenshtein distance function. Tessaract ranks first in accuracy, and it is closely followed by DocTR and EasyOCR in the presented order. A more useful study for our case is reported in [

39], where DocTR and EasyOCR are compared on the CORD and SROIE receipt datasets. The character error rate (CER) for DocTR is three to five times smaller than that of EasyOCR. In addition, DocTR’s CER is less than double that of the Azure (

https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/products/ai-services/ai-vision, accessed on 27 June 2023), Textract (

https://aws.amazon.com/textract/, accessed on 27 June 2023), and Google OCR (

https://cloud.google.com/use-cases/ocr, accessed on 27 June 2023) commercial systems. Unfortunately, Pytessaract is not included in the study. We, therefore, carried out a study on a sample from our receipt dataset to compare EasyOCR, Pytessaract, and DocTR directly. As evident in

Table 1, we found that DocTR’s performance is superior to that of both Pytesseract and EasyOCR. Therefore, on the basis of accuracy, we chose DocTR as the OCR engine in our receipt labelling pipeline. Moreover, DocTR uses pre-trained detection and recognition models. By default, we use

db_resnet50 (

https://huggingface.co/smartmind/doctr-db_resnet50, accessed on 27 June 2023) and

crnn_vgg16_bn (

https://huggingface.co/Felix92/doctr-dummy-torch-crnn-vgg16-bn, accessed on 27 June 2023).

6. Rule-Based Model

A rule-based model was implemented to operate either as a standalone inference model or to further improve and error-correct the multi-modal transformer’s classifications. When the model is used in conjunction with LayoutLM, the rule-based model has the capability of considering the transformer’s outputs before applying any rules. The rule-based model is made up of a series of regex-based pattern-matching rules, tabular-data feature extraction rules, rules based on database searches, and comparison-based error-correcting rules. The following sub-sections describe these features.

6.1. Pattern-Matching Rules

Pattern-matching rules form the core of the rule-based model’s ability to identify and classify useful information in printed receipts. These rules rely on regular expressions and logic to match specific text patterns and classify them into twelve predefined categories. The rules are flexible and adaptable, capable of handling various text formats and common OCR errors (such as the interpretation of “.” as “,” or “O” as “0” and vice-versa). The pattern-matching rules can also run standalone and do not consider pre-classified tokens. We describe the implemented pattern-matching rules below:

TOTAL: This identifies sequences of words in a line in a document that contains the total amount due, often found at the end or second half of receipts. The rule looks for keywords like TOTAL, AMOUNT DUE, or their variations, followed by a numeric value, which is typically the total amount. If such a pattern is detected, and no other works like SUBTOTAL, VAT, or NET are present in the line (e.g., so as not to match with VAT TOTAL or NET TOTAL), the rule labels the line as Total.

Example matches are TOTAL: $123.45; AMOUNT DUE: €678.90; and TOTAL $234.56.

DATE_TIME: This identifies dates and times in various formats within a document. It recognises month names in both the English and Maltese languages, including abbreviations (as well as common typos), and it supports a wide range of date and time formats, including the following: DD-MM-YYYY or D-M-YY, Month DD, YYYY, and HH:MM:SS AM.

When a match is found, the sequence of words in a line corresponding to the match is labelled as Date & time.

Example matches are 23-08-2024, 23 August 2024, and 12:45 PM.

VAT_INCLUDED: This identifies lines that mention VAT or tax amounts. It searches for patterns that indicate VAT rates or amounts, such as VAT TOTAL, TAX @, or RATE, followed by a percentage and an amount. When a match is found, the sequence of words in a line corresponding to the match is labelled as VAT included.

Example Matches are VAT @ 18%: $12.34 and TAX TOTAL: €5.67.

VAT_INFO: This identifies VAT numbers and related information in a document. It recognises patterns that include VAT registration numbers or other tax identification numbers, which are often preceded by keywords like VAT NO, VAT REGISTRATION, or EXO. Common OCR errors are accounted for as well, e.g., EX0 instead of EXO, MI instead of MT in the VAT number, etc. When a match is found, the sequence of words in a line corresponding to the match is labelled as VAT info.

Example matches are VAT NO: MT1234-5678, VAT REGISTRATION: 1234-5678, and EXO NO: 9876

TELEPHONE: This identifies telephone numbers within a document. It searches for keywords like TEL, PHONE, or MOBILE, followed by a numeric pattern that corresponds to a phone number. The rule also handles the specification of Malta’s country code in either one of two formats: +356 or 00356. Furthermore, the rule is capable of recognising multiple phone numbers listed in sequence. When a match is found, the sequence of words in a line corresponding to the match is labelled as Telephone.

Example matches are TEL: +356 8123 4567, PHONE NO: 00356-8123-4567, and MOBILE: 3999 9999/+356 8111 1111

6.2. Rules for the Classification of Named Entities

Names of shops and addresses consist mainly of proper names corresponding to entities. Therefore, a database approach was considered for labelling these categories. The general idea is to build a database (one for each class) that is then queried with the text to be classified. In the case where the query returns a match, the text is labelled as either (‘Name of shop’) or (‘Address’). The two databases were initiated from data available in the real-world-receipt training set. In addition, we experimented with location data obtained from publicly available post office data, on-the-fly queries to Google APIs, and web scraping, but these would incur either an additional fiscal or search cost. Bringing a human into the loop will also add entries to the database. One limitation of the database approach is the rate at which its size and search time grows.

6.3. Line-Item Extraction and Classification

Spatial and pattern-matching techniques were employed to extract line-item information from a receipt. This process involves identifying regions containing tabular data based on text alignment and spacing patterns, which typically represent the region of a receipt that includes line-item details.

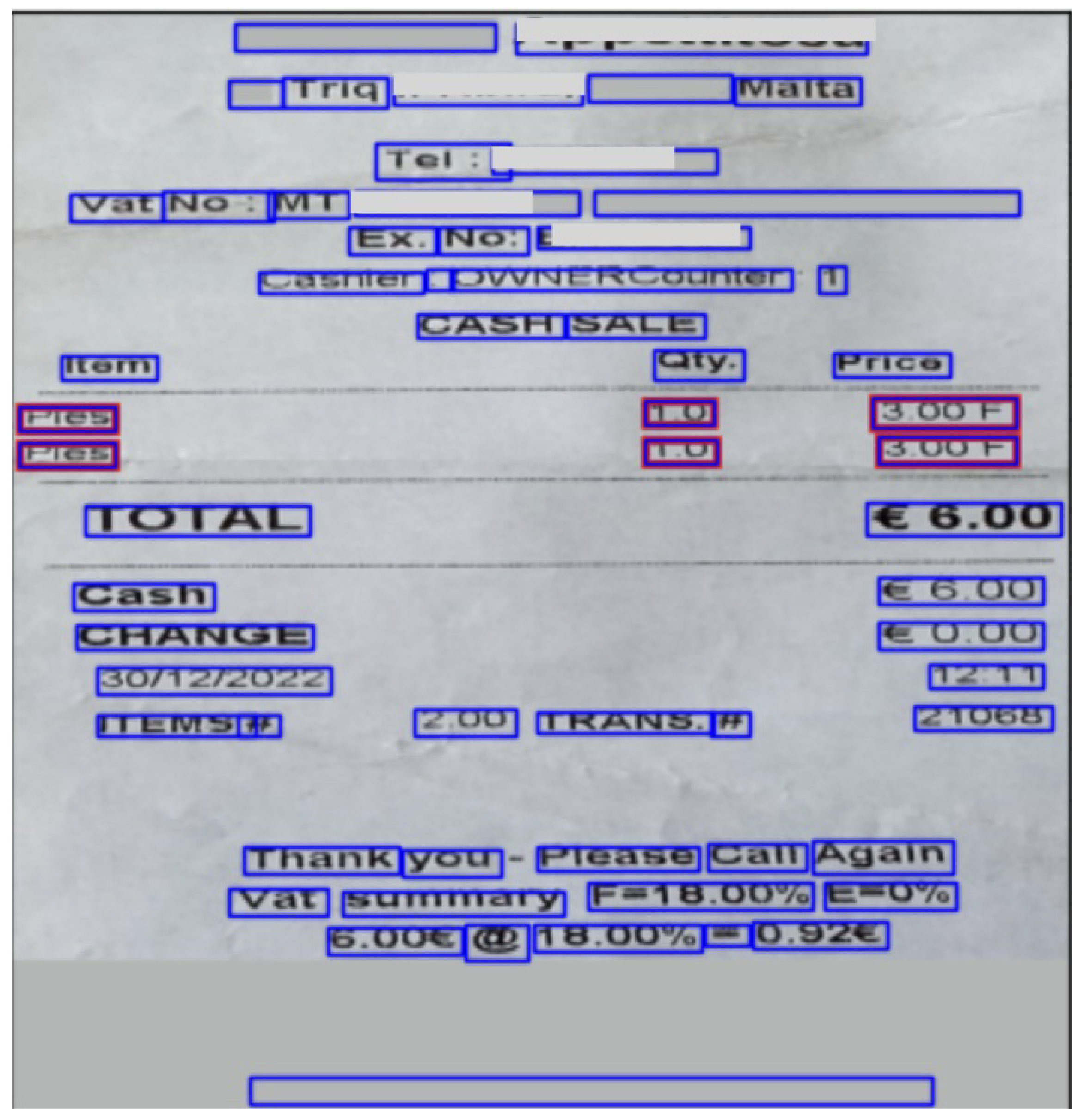

The system recognizes tabular data by analyzing the horizontal spacing between words and grouping them into columns. This allows the identification of line-item sections, as illustrated in

Figure 5, where each column typically represents specific information, such as item descriptions, quantities, prices, and total amounts.

Sometimes, there may be other non-line-item data presented in a tabular manner, such as VAT information. Therefore, a simple rule-based analysis is carried out to exclude lines containing certain keywords so that the identified region is restricted to the line items. Furthermore, on occasion, the line items span over two lines, with the line-item description on the first line and the price, quantity, and amount printed on the second. Therefore, the line-item segment of the receipt alternates between tabular and non-tabular data. This scenario is also handled to ensure the proper identification of the line-item regions.

Once the columns are identified, they are classified according to their content. Text-only columns are classified as item descriptions, whereas columns containing numerical data are classified as quantities, unit prices, or amounts. Thus, the classification process followed predefined rules that evaluated the structure and format of the data within each column.

6.4. Contextual Sequence Relabelling Rules

These rules work by evaluating the context of each word token in relation to its neighbouring word tokens on the same line, and they are applicable to classes where the content may consist of a number of word tokens. For example, a line of text pertaining to an address of a shop might be “52, Guzeppi Caruana str., Santa Lucia”, in which case we expect all six word tokens to be labelled as (‘Address’). However, some word tokens may have been mislabelled; therefore, these rules adjust the labels to maintain consistency across the sequence. For example, suppose that one of the words was misclassified by the classifier model as being part of the name of the shop (which is possible given that these two types of fields are typically close to each other), and we see the following sequence of pairs of labels and confidences: [(‘Address’, 0.95), (‘Name of shop’, 0.41), (‘Address’, 0.87), …]. We know that the name of the shop typically precedes the address, and we also see that we have a “name of shop” label with a low confidence score (i.e., <0.5) padded on either side by address labels having a high confidence score from the classifier. Therefore, it is reasonable to write an error-corrective rule that flips the “name of shop” label to an address label. A similar process is used to look for consistency among the (‘Name of shop’) and (‘Line Item’) classes, since these also exhibit the structure of a sequence of word tokens.

6.5. Joint Rule-Based LayoutLM Model

The LayoutLMv3 classifier model is executed in conjunction with the rule-based model according to the following pipeline:

Extract receipt image and execute OCR to obtain text and bounding boxes.

Predict labels for each bounding box and text from the LayoutLMv3 multi-modal classifier.

Execute the line-item processor:

- (a)

Detect tabular layouts, organize bounding boxes and text into columns, and add labels on the basis of heuristic criteria.

- (b)

Iterate over each bounding box and the corresponding LayoutLM label confidence:

If the label confidence is greater than the replace threshold (set to 0.6 in our experiments, slightly above the average scores obtained for rule-based line-item extraction), then skip to the next bounding box.

Else, if the existing label matches the new one, update the confidence to 1.0.

Otherwise, replace the label with the rule-derived one, and set label confidence to 0.5.

Execute the regex-based rules.

Since these rules are based on manually written regex expressions, matches are considered as correct, and hence, the result overwrites LayoutLM’s decision.

Execute the contextual sequence relabelling rules.

Return the labelled bounding boxes and text.

7. Results and Discussion

In total, seven different models were evaluated and compared for the receipt-labelling task. All models were evaluated using the same hold-out test set, which consisted of 147 real-world samples. The models are categorized and outlined below:

Rule-Based Model: The

RULE model is based on the work presented in

Section 6.

Layout Language Models: Three

LyLM models, based on the work in

Section 5, were considered: (a)

LyLM-RW: classifier trained on the dataset of real-world thermally printed receipts; (b)

LyLM-SA: classifier trained on a dataset of synthetically generated receipts; (c)

LyLM-MX: classifier trained on a dataset consisting of a mixture of real-world and synthetically generated receipts.

Joint Models: The joint model first runs one of the classifier LyLM models, yielding a labelled receipt, and then, we use the RULE model to further improve classifications. This gives rise to three additional models: LyLM-RW + RULE, LyLM-SA + RULE, and LyLM-MX + RULE.

Our baseline

LyLM-MX model achieved an overall F1 score of

. In comparison, the 133M parameter LayoutLMv3 base model in [

1] achieved an F1 score of

on the CORD dataset (11,000 Indonesian receipts and five superclasses). The difference can be attributed to our much smaller dataset and larger number of classes.

From the F1 scores reported in

Table 2, it is apparent that the overall best-performing model is the one using the LayoutLM model, for which its classifier is trained on a mixture of real-world and synthetic data, and it is jointly used with the rule-based model:

LyLM-MX + RULE. The rule-based model improves the baseline

LyLM-MX by almost 3%. We note that, similarly, the larger 368 parameter LayoutLMv3 model in [

1] achieved an F1 score of 0.975 on the CORD dataset, a

increase over the smaller model. The

LyLM-MX + RULE is, however, much less demanding on computational resources.

It is clear that the addition of synthetic data had only a very small positive effect on the overall performance of the joint LayoutLM-rule-based models (LyLM-RW + RULE and LyLM-MX + RULE). On the other hand, the addition of the rule-based model improves the LyLM-SA model, trained solely on the synthetic dataset, by approximately 10%.

Table 3 lists the per-label F1 scores for all models. It is apparent that training solely on synthetic data is not sufficient for labelling real-world receipts. It follows that the synthetic dataset requires either more variations in formats or added noise. On the other hand, when compared to

LyLM-RW, the

LyLM-MX model improves on certain classes (e.g., name of shop, address) that also fare relatively well in

LyLM-SA. In addition,

LyLM-MX, when compared to

LyLM-RW, marginally degrades on other classes (e.g, telephone, VAT info) that do not perform well in

LyLM-SA. These results seem to indicate that an update to the synthetic dataset can help improve performance on some other classes. Moreover, the addition of the rule-based model to the

LyLM models improves mostly on “telephone” and “vat info” classes, followed by “Date and Time”. For some classes, like “total”, the same joint model fares marginally worse when compared to the respective

LyLM model.

When the rule-based model is used on its own, the average F1 score is

. Overall, this is, by far, the worst model. However, this model is far more efficient in the use of memory and CPU time computational resources (see the end of this section below), and further improvements to this model can be very useful, especially for cases where only a subset of information is required. The development process of the rule-based model demonstrated the difficulty of extracting line items from thermally printed receipts, where information is formatted in various spatial layouts, presumably owing to the limited width of the paper. The per-label results for the rule-based model in

Table 3 are a testament to this issue. The

LyLM models were surprisingly effective at extracting individual row and column items.

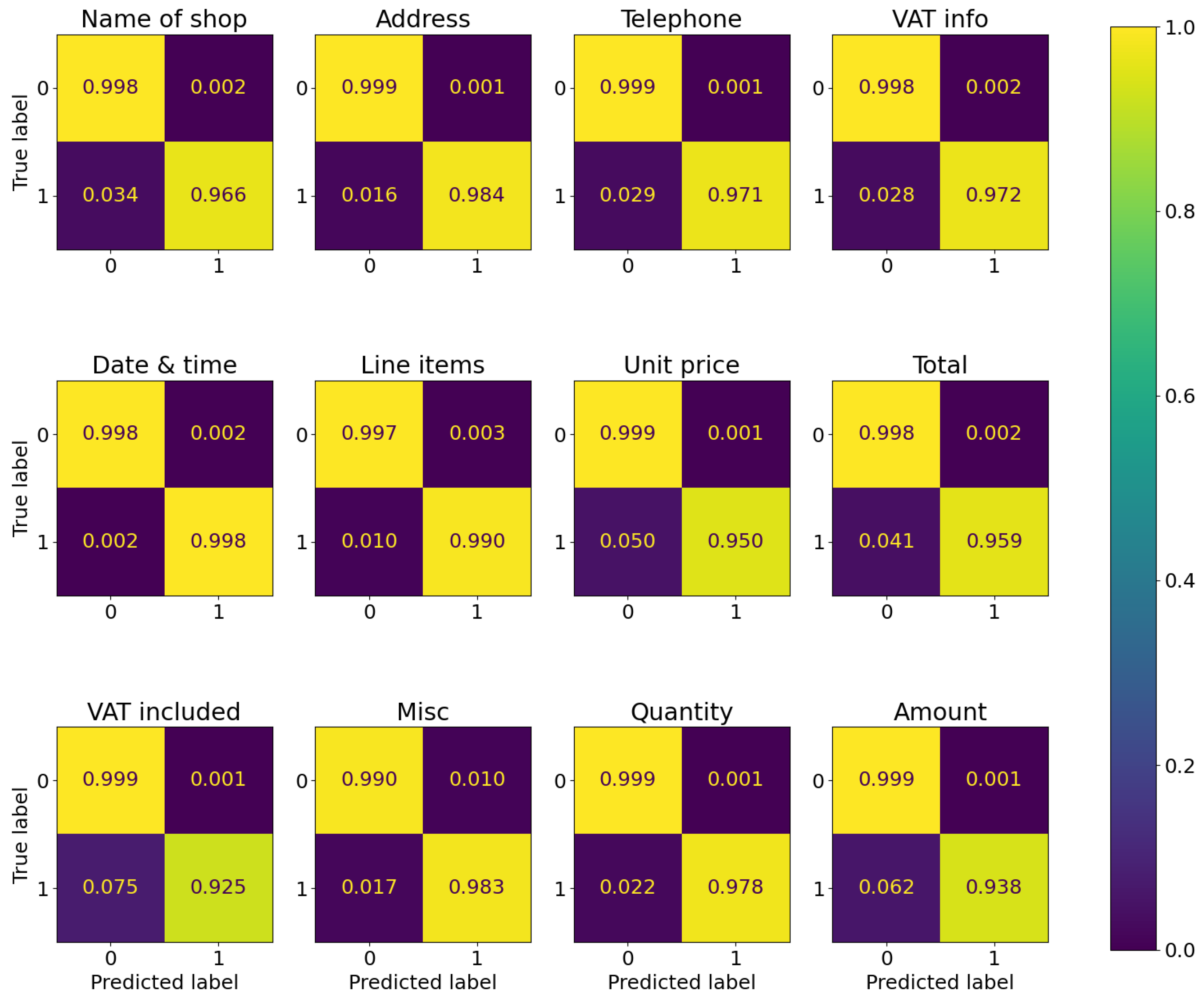

Figure 6 depicts the confusion matrices for all classes for the

LyLM-MX+RULE model. The true positive rate (TPR) (0.95 and 0.938) for line-item columns “unit price” and “amount” are lower than for the other classes, barring “VAT included”, which scores the lowest (0.925) TPR. An error analysis revealed that this could be due to the currency symbol being included in the line-item rows along with numerical “unit price” and “amount” values. Other classes that need improvement in the rule-based model are “total” (

), VAT included (

), and "name of shop" (

).

We now carry out a limited comparison (due to the use of different datasets) with related work discussed in

Section 2). In [

6], a rule-based model was developed and tested on 90 Swedish receipts. The F1 scores for this model are VENDOR =

(ours

), ADDRESS =

(ours

), DATE =

(ours

), TAX RATE =

(ours

), PRICE =

(ours

), and PRODUCTS =

(ours

, calculated as a weighted average across all four line-item fields). Our model performed significantly better in extracting PRODUCT data and marginally better in ADDRESS and DATE; however, it was marginally worse in extracting PRICE (total), significantly worse in the case of VENDOR name, and overly worse in TAX. Interestingly, our tax extraction rule improved the output of the

LyLM-RW and

LyLM-MX models but failed when the rule-based model is used on its own. With the addition of database-updating strategies, as discussed in

Section 6, the scores for “address” and “name of shop” should increase. However, these classes can also benefit from pattern recognition rules (as in [

6]) or, perhaps, from a lightweight named-entity-recognition model.

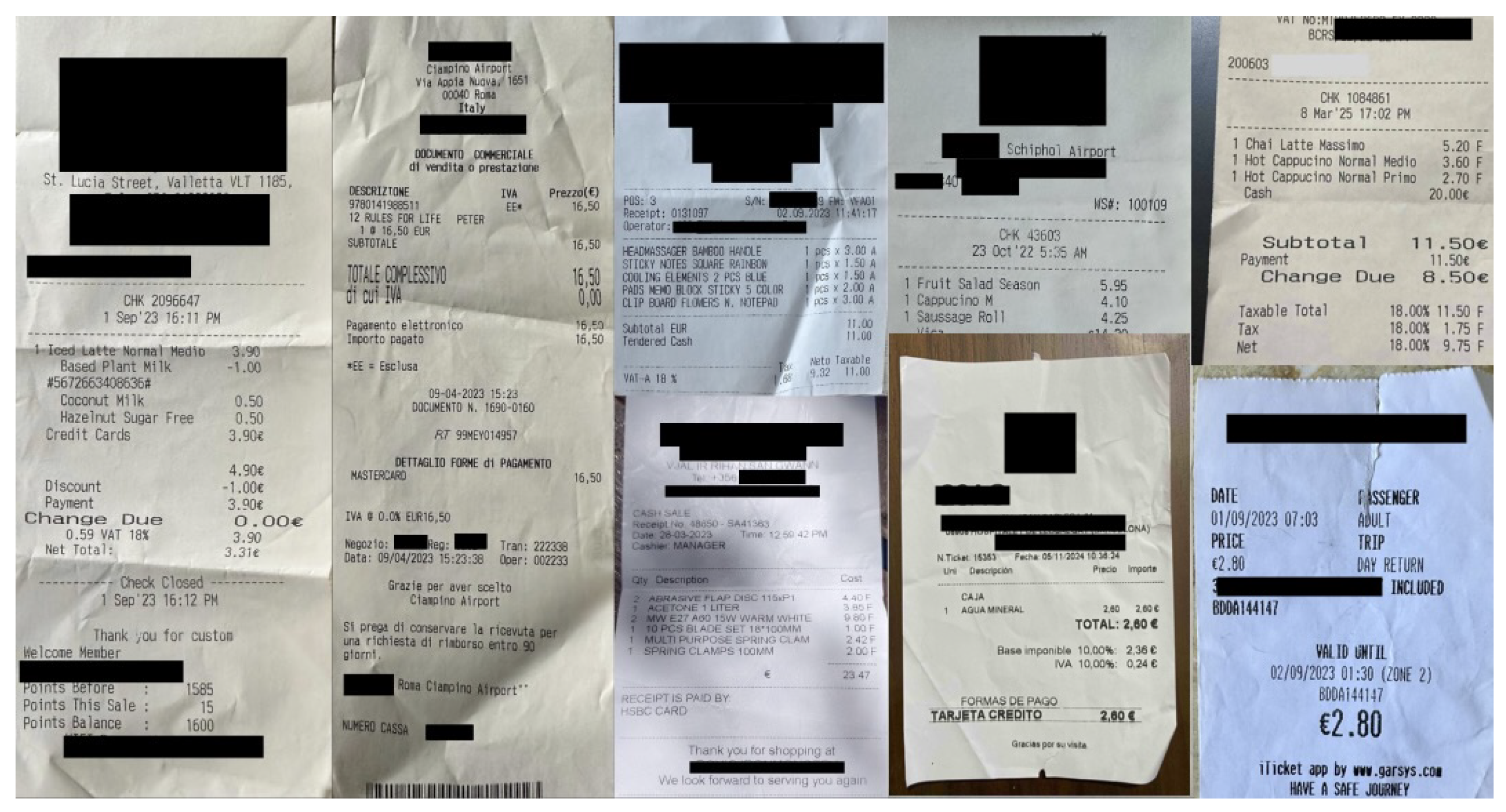

The receipts that make up the training dataset were predominately (

) in the English language. We, therefore, carried out a small-scale study on a limited number of receipts, 26 in total, which were roughly uniformly split across four European languages (Polish, Spanish, Italian, and German). As shown in

Table 4, the average scores obtained (

LyLM-MX + RULE model) are lower than those for the English language. Most notably, detecting VAT information is difficult across the board, possibly due to language and regional differences. Although present in most receipts, the model failed to detect text pertaining to the “VAT included” or “telephone” categories in Polish receipts. This is probably due to the way the receipt is structured. Detecting “total” in the examples of Italian receipts seems to be difficult, whilst scores for receipts in German are low on "name of shop”, “address”, and “telephone”. Polish receipts have the smallest macro-average score, and some Italian receipts have a combined “Quantity-Unit Price”, for example, “

”, which our model fails to resolve, but they are correctly labelled in Polish receipts where there is a space in between the quantity and the “×” symbol. It is clear that examples in target languages need to be added in the training dataset.

Finally, we measured the CPU computational time and memory requirements for all methods. The measurements were carried out on an Apple M3-processor-based machine. All methods based on the LayoutLMv3 model took ≈480 ms for inferencing. As expected, the addition of the rule-based model did not substantially increase computational times. Once loaded, the transformer model occupies ≈480.61 MB. This is close to the theoretical value of 480 MB, assuming 125.9 M parameters and float32 numbers. The memory requirement increases by ≈400 MB to a total of ≈900 MB due to activations, the image, and some other overheads. The rule-based model, excluding the Address and Name of Shop database searches, takes ≈1.1 ms and increases to ≈4.3 ms when included. The latter is of particular concern since the database’s size can keep growing, and other rule-based or model-based approaches should be considered, as outlined above. The memory size occupied by the rule-based model is <0.3 MB. These results are interesting from the point of deployment. As it stands and with an improvement in extracting the Total and the Name of Shop field, the rule-based model can be used when the minimal subset of information is needed, i.e., supplier’s name, date, and total amount. In this case, an improved rule-based model offers a computational advantage over the neural network transformer model.

8. Conclusions and Limitations

From the results reported in

Section 7, we conclude that joint models (neural network plus rule-based) shows promise in matching the performances of larger neural network models in receipt information extraction tasks. The addition of the rule-based model improved the neural network by almost

to a final F1 score of

. The neural network model (

LyLM-RW), on its own, achieved a score of

, averaged over all 12 classes, with relatively few real-world samples.

Despite the promising results, the study carried out on receipts in other languages showed that there are language and jurisdictional/regulatory limitations. Nonetheless, owing to the relatively small real-world sample size required to achieve respectable accuracy from the LyLM models, we believe that the effort required to support new languages and regions is reasonable, since it depends on collecting data and retraining the model’s classification head. Furthermore, it is envisioned that the model will eventually be used in a product where end-users have the option to manually correct annotated receipts, which can then be stored and used to periodically fine-tune the LyLM model. Therefore, LyLM can progressively learn receipts in new languages and regions.

However, additional manual effort is required to add language and regional support to the rule-based model, since rules operating on some classes, for example, telephone number or tax information, would have to be hand-crafted depending on the various formats used in a language or geographical region. Future work must also include further development on the tabular-data feature extraction pipeline of the rule-based model (which is language-agnostic) and on the “total” and “VAT amount” fields. With improvements to the rule-based model’s rules and to the way it is combined with the neural network classifier model, it may be possible to use a lower-complexity neural network, thus reducing demand on the computing resources.