Abstract

This study explores a learning knowledge representation, using an iteratively reevaluated lattice of equivalence-classified properties. The proposed methodology is based on the evaluation feedback between the maximal and minimal elements of the compatibility lattice. The simplified example shows how the expert evaluations of conventional and advanced Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) computational tools contribute to generating novel solutions for manufacturing industries. The knowledge base is initialized with heuristically established equivalence classes and pairwise compatibility relations between classified properties. The learning process begins with a heuristically determined, initially evaluated subset of maximal elements (complete combinations), followed by the implementation of a theoretically established iterative learning algorithm, driven by evaluation feedback. Utilizing the normalized real-valued assessments of the complete combinations, the knowledge base undergoes reevaluation, leading to uncertain assessments of the binary compatibility relations. This evolving knowledge base then facilitates the algorithmic generation of new, tendentiously more effective complete combinations. Findings indicate that through these iterative learning steps, the uncertainty due to ‘lack of knowledge’ significantly decreases, while the uncertainty associated with accumulated knowledge increases. The overall summarized uncertainty initially reaches a minimum before gradually rising again. Further analysis of the knowledge base after several learning iterations reveals the contribution of individual binary relations to the valuation of newly proposed combinations, as well as contains lessons for the optional refinement of the initial compatibility lattice.

1. Introduction

Amidst a multitude of new Artificial Intelligence (AI) and specifically Machine Learning (ML) methods and tools, as well as their combinations with traditional computational tools [1,2], identifying and matching workable solutions to various specific manufacturing tasks is challenging. According to our knowledge, there is no systemic overview for structuring different types of conventional and AI/ML applications along various levels and tasks of problem solving. This paper suggests and illustrates a method for the systematization of possible methodologies, also including capabilities to experts’ assessment-based development of new methodological combinations.

This scientific analysis provides an overview of various engineering tasks and tools, focusing on AI/ML methods and on the most current AI applications in manufacturing. A systemic perspective is added to the overview by structuring AI/ML applications in manufacturing along multiple dimensions, represented by equivalence classes of features, determining the tasks to be solved, the levels of application, the phases of problem solving, the objectives, as well as the various types of conventional and AI/ML-based methodologies. The resulting classification allows us to describe the interconnectedness of conventional and AI applications in manufacturing.

The development of a systemic analysis of AI applications in manufacturing requires a comprehensive understanding of both AI technologies and industrial manufacturing problems. This understanding aims to serve as guidance for manufacturers who want to evolve from the early-stage, conventional, and isolated AI application to systematic, integrated AI leverage. Moreover, this analysis allows AI solution providers to gain expertise at the intersection of AI, conventional problem-solving methodologies, and manufacturing in the context of sustainability-driven complexity issues.

1.1. Engineering and Management of Developing Sustainable Manufacturing

Definitions of manufacturing commonly include a description of required assets, the processing of materials, and resulting goods or products [3,4].

Industrial manufacturing can be characterized by utility-scale production assets, allowing large volumes of product while consuming high amounts of energy, physical resources, and financial expenditures. Compared to smaller-scale manufacturing, high degrees of automation are implemented, and fewer human resources are required per unit of product.

Important to note, ‘manufacturing’ is not a synonym of ‘production’. While production includes value-adding processes, manufacturing additionally encompasses organizational and managerial functions like design, process planning, and control.

Pursuing ever-greater competitive edge, process control and optimization are at the core of industrial manufacturing. Process control and optimization balance output, quality, and consumed resources including time and labor while maintaining safety and compliance. Process optimization aims to eliminate unnecessary steps, to schedule maintenance, and to automate system as much as possible [5].

Yet even a perfectly optimized manufacturing process is part of a larger environmental context. IT and data security issues, supply chain disruptions, or dynamic regulatory conditions, i.e., sustainability requirements, are examples impacting the manufacturing process. Nowadays, society is compelled to develop a sustainable circular economy against exhausting raw materials and accumulating waste. These large process systems are affected by demographic and climate change, as well as by fast shocks caused by extreme weather and unexpected ecological and socio-economic situations. Planning and operation of these large-scale complex processes require the appropriate integration of diversified elements of field- and task-specific digitized data and models.

The typical set of conventional computational problem-solving methods in manufacturing, considered in this work, includes the following methods and tools: (Dynamic) simulation [6]; Model-based Predictor-Corrector (MPC) [7,8]; Stochastic Process Control (SPC) [9,10]; Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) [11]; Mixed Integer Non-Linear Programming (MINLP) [12,13,14]; Finite Element Analysis (FEA) [15,16]; Data Mining and Analytics [17,18]; Computer-aided Design (CAD) [19,20]; Computer-Aided Manufacturing (CAM) [20,21]; Real-time Monitoring and Control Systems [22,23]; Simulation-based Optimization [24,25]; and Expert Systems [26,27].

A more detailed explanation of conventional computational problem-solving methods can be found in Supplementary Material S1.

1.2. Evolving Methods and Tools of Artificial Intelligence

Recently Artificial Intelligence (AI) and especially Machine Learning (ML) ‘came into vogue,’ as a methodological support for the analysis of Big Data generated by the Internet of Things (IoT) (e.g., intelligent data analytics for time series and images, etc.). It is worth remembering that AI had started with two challenges (e.g., [28,29]). The foundations of knowledge representation and search prepared Expert Systems and Machine Learning, on the one hand. The (practically first-order) predicate calculus initiated the development of AI programming languages (LISP and Prolog), on the other.

Engineering applications of AI were implemented throughout manufacturing industries, complementing the traditional computational methods of model-based design and control. However, the more complex systems fell behind the computer model-based problem solving at that time. Recently, these applications met the opportunities of affordable sensors, the Internet of Things, Big Data, intelligent data analytics, etc., and progressed rapidly. Simultaneously, this fast development caused forgetting of the non-linear dynamic balance-based methods of engineering design, planning, control, and operation, as well as losing the clear overview of causal relations and balances behind complex process systems. Nowadays, inspired also by the sustainability of natural systems (e.g., [30]), the planning and operation of complex circular processes emphasizes the combined applications of AI with other engineering methodologies.

AI and ML are often synonymously used by people outside the technology industry, but there is a difference. AI generally refers to a program or system capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence.

ML is a subset of AI that focuses on algorithms that can learn from data and improve their performance as they are used over time. In other words, if you give an ML program enough information about a certain feature of an object or subject, it will be able to identify the object or subject more accurately than when it started [31]. ML algorithms are most used in manufacturing because they help machines make decisions based on data rather than programming them with every possible scenario they may encounter [32].

A typical set of AI/ML-based computational problem-solving methods in manufacturing, considered in this work, includes the following methods and tools: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [33,34,35]; Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [36,37]; Random Forests [38,39]; k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) [40,41,42,43]; Fuzzy Logic and Reasoning [44,45,46,47,48,49]; Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [50,51,52]; and Evolutionary Learning Strategies [53,54].

A more detailed explanation of each AI/ML-based computational problem-solving method can be found in Supplementary Material S1.

1.3. AI Applications for Sustainable Manufacturing

AI technology offers solutions not only for process optimization in manufacturing industries. Plastino and Purdy [55] identify three clusters of AI applications to increase profits independent of specific industries. The first cluster is intelligent automation, upscaling the idea of local monitoring to a wider dimension encompassing the whole supply chain. Instead of limiting the sensor-based monitoring to individual machines or production sites, intelligent automation leverages AI’s advantages from procurement to customer service. Spot-market priced sourcing, interdependent productions, competitor and market intelligence, production flexibility, and countless more factors can be leveraged in sophisticated algorithms, exceeding human capabilities by far. The second cluster contains AI applications augmenting labor and capital. AI is increasingly capable of taking over time-consuming tasks with low value added, e.g., data research tasks, skimming unstructured data, pre-selection of documents. Thus, workers can allocate more of their labor time to high-value work. Another example of AI-based profit optimization is predictive maintenance. AI can expand condition monitoring to scales unreachable for humans and even simulate systemic forces to flag potential problems. Thirdly, a cluster of AI applications is around increasing effectiveness in innovation. AI helps to identify promising avenues of innovation and reduces resources spent on unqualifying ideas. AI can drastically reduce the investments in trial-and-error phases of innovation and select promising ideas from the innovation funnel [55].

The recently fastened development of AI- and ML-based methods and tools for engineering and managerial problem solving (accompanied by some vulgarization) caused terminological mismatching, as well as misunderstandings [56], that can potentially lead to low perceived trustworthiness of AI [57]. This situation also motivates the clear, systemic analysis of the underlying methods and applications.

1.4. Methods for Discovery of Methodological Combinations

Considering the need outlined in the previous Sections, various published methods can be found in the literature; among them are Bayesian Optimization [58], Active Learning [59], Reinforcement Learning for Method Selection [60,61], Knowledge-Graph Reasoning [62] and Genetic Algorithms [63].

A Bayesian network is a probabilistic approach that represents a set of variables and their conditional dependencies, using a directed acyclic graph. On this basis, Bayesian Optimization focuses on finding the global optimum, efficiently, while Bayesian updating revises beliefs as new evidence is available [64]. Bayesian Optimization might be applied efficiently for identifying and combining hyperparameters for better task–tool matching [58]. Also, Hidden Markov Models, Markov Random Fields, or Decision Graphs [65] can be mentioned among the probabilistic methods.

Active Learning is a subset of Machine Learning methods in which a learning algorithm can query users (i.e., experts) interactively to label data with the desired outputs [66]. It can be helpful tackling the challenge of hard-to-acquire and costly expert evaluation, as the algorithm proactively selects those subsets of examples to be labeled next from the pool of unlabeled data that are deemed to help the most if their labels are known.

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are population-based metaheuristics, inspired by biological evolution that evolves candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation to solve optimization, search or time-sensitive task allocation problems [67,68]. GA’s memory is limited to the population of some complete combinations, and learning is controlled by the evolving schemes.

According to the above overview, an actual challenge is that complex systems of sustainable manufacturing require sophisticated methodologies along with a clear systemic analysis of the underlying complex tasks and of appropriate combinations of conventional and AI-based computational applications for the solution of these tasks. The literature, based on real-life use cases, provides exemplary assessments of utilizable methods and tools. However, a methodology is needed to learn from these solutions, as well as to suggest possible new combinations from the accumulated knowledge base.

1.5. Objective

The main objectives of this work are the following:

- To introduce and to test a methodology for the systemic categorization and evaluation of conventional and AI/ML applications in manufacturing;

- To provide an overview of the existing methodological combinations;

- To contribute to the algorithmic generation-based suggestion of new solutions from a continuously evolving knowledge base of the existing methods.

The specific aims are the following:

- To classify the properties, characterizing (a) the engineering and management tasks, as well as (b) the applied conventional and AI/ML-based methods and tools used for developing sustainable manufacturing;

- To assess the usefulness of computer-supported problem solving in manufacturing, based on published case studies and experts’ knowledge;

- To create an algorithm resulting in a learning knowledge base for the development of usable, advantageously AI-involved, optionally combined computational methods and tools for supporting the development of new, effective, and sustainable (e.g., circular) solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

Considering the above objectives and specific aims, in the development and application of a new method for the discovery of methodological combinations, the following features must be taken into consideration:

- The constructive equivalence classification of underlying properties of the tasks and the applicable methodologies or methodological combinations;

- Commutative and associative character of (compatibility) relations between the properties within the combinations (in graph representation, it is described by non-directed edges);

- Rather a possibilistic than probabilistic kind of associated uncertainty;

- Consistent representation of lack of knowledge;

- Expressing of some essential properties of evaluation distributions, coming from expert’ suggested heuristic values;

- Algorithmic generation of aggregation and optionally the consent of evaluations from multiple experts.

Accordingly, the applied methodology is based on the iterative reevaluation of the lattice of the compatible properties, classified into equivalence classes. Lattice is an abstract structure studied in the mathematical subdisciplines of order theory and abstract algebra [69]. The special compatibility lattice of the discrete properties was introduced by Blickle [70]. This lattice belongs to a family of optionally fuzzy valuated relational algebras [71]. An example was published in [72], where the methodology was applied for supporting polymer composite experimentation.

2.1. Minimal and Maximal Combinations in a Property Lattice

The formal description of the lattice, as relational algebra [71], is given by the quintuple

where S is the set of combinations in the structure; and are special elements; while and are the connectives, composing and decomposing the combinations, according to the definitions of

and

respectively. All the combinations are given as a subset from the power set of the minimal (generating) binary relations , while the set S also contains the maximal combinations , as follows:

The minimal and maximal combinations are defined by the following expressions:

The ν order of elements determines the number of the minimal (generating) elements in the given elements.

Specially, the compatibility lattice [70] is built from properties T, classified into equivalence classes

while the generating minimal elements are compatible pairs of properties

belonging to two different equivalence classes, and the maximal combinations are property sets containing one and only one property from each equivalence class.

2.2. Evaluation of the Property Lattice

The lattice structure (Equation (1)) can be extended to an evaluated structure [71,73], as follows:

where the former quintuple (Equation (1)) is extended with the m and M normalized evaluations of the worst and best solutions containing the given subset, as well as with the minimum (min) and maximum (max) operators (Equation (9)). According to Equation (10), the set of combination can be interpreted as a subset in the power set of minimal (binary) combinations, while the set of maximal complete combination is a subset of set S. In the resulting Reevaluable Possibility Space (RPS), , according to Equation (11), means the normalized evaluation of the maximal combinations, while m() and M() are for the lower and upper bounds of the uncertain evaluations of the less-order (in the marginal case: minimal binary) elements in sense of Equations (12) and (13).

In the learning phase of RPS, we determine the uncertain evaluation of the minimal relations by the intervals [m, M], with the knowledge of the evaluation of the maximal combinations. In the discovery phase, considering these uncertainly evaluated binary relations, we can generate proposed solutions in the form of new maximal combinations. The change in lower and upper bounds of the disjunctive and conjunctive operators can be calculated by Equations (14) and (15), as well as Equations (16) and (17), respectively.

The RPS is also prepared for discrete (Yes/No, 0/1) evaluations of maximal elements (complete combinations). In this special case, the less-order (finally binary) elements may have four values. In the respective four-valued logic the elements may be true (m = 1 and M = 1), false (m = 0 and M = 0), uncertain (m = 0 and M = 1), and unknown (m = 1 and M = 0). The completeness of valuated lattice (9) can be seen from the facts that special elements and are ‘uncertain’ and ‘unknown’, respectively.

According to Equation (11), the maximal elements (complete combinations) are characterized by an unambiguous evaluation that can be normalized into the [0, 1] interval. The lower-order combinations, and finally, the minimal (binary) elements, have increasingly uncertain evaluations. It is to be noted that in a more sophisticated interpretation, the less-order elements can be associated with a changing evaluation distribution that represents the distribution of the value of maximal elements they participated in. Considering the difficulties of algorithmizing these distributions, we use a simplified approach and characterize the uncertainty with the domain of these distributions that can be defined by the [m, M] sub-intervals of the whole [0, 1] interval. Accordingly, the uncertainty (U) of minimal (binary) elements () can be calculated as follows:

where

and

while uncertainty U can be normalized (resulting u) by dividing with the number N of binary elements:

In the case of lack of knowledge, the uncertainty (U) is negative; that is why the uncertainty of lack of knowledge and of the evaluation-based uncertain knowledge have to be distinguished. Nevertheless, their absolute values may be summarized.

2.3. Reevaluable Possibility Space for Generation of Problem-Solving Methods

Considering the huge number of possible combinations on the one hand, as well as the heuristic knowledge of collaborating experts on the other, it is an effective way to generate the possible tendentiously better combinations in the above outlined RPS framework. In this methodology, the features (characteristics, properties, etc.) of analyzed solutions are described by a compatibility lattice (Equations (1)–(6)), consisting of feature equivalence classes (Equation (7)) and binary compatibility relations (Equation (8)) between the elements of the various classes.

In equivalence classification, each feature belongs to one class exclusively, while the compatible maximal combinations (), built from binary relations (), contain one and only one feature from each class. For example, the various tasks and levels of manufacturing systems, the various computational methods, etc., determine the feature equivalence classes, while compatibility of properties is declared by the binary relations between them (e.g., between a given task or level and a given AI-based computational method, etc.).

The essential features of the evaluation feedback-based learning algorithm are the following:

- According to Equation (10), the complete combinations () can be evaluated by one or more experts or objective functions, unambiguously, while

- The set of partial property combinations and ultimately the set of smallest binary relations () can take place in multiple solutions of different values, so their evaluation is uncertain.

However, the appropriately described uncertain values [m, M] of minimal (binary) combinations contain an uncertain knowledge that can be used for the suggestions of new complete combinations.

The complete combinations () can be evaluated by a single real value (V in Equation (11)), normalized by the temporarily achieved best values to the [0, 1] interval. The partial combination of features (and finally the binary compatibility relations, ) inherits an uncertain knowledge, expressing the evaluation of maximal combinations they participated in. This knowledge can be utilized for the selection of new candidates for the next maximal combinations to be tried. Optionally, the method can be extended for the consideration of multiple evaluating objectives, while an automatic consent can be derived from time to time, and each objective follows the evaluations, according to the consensus-related knowledge base.

A considerable amount of ‘a priori’ knowledge of field experts can be embedded into the possibility space by the appropriate selection of feature classes (), features, and compatibility relations (). Accordingly, the method can utilize this ‘a priori‘-given heuristic knowledge, while the continuous reevaluation of this knowledge base by the newly suggested and evaluated maximal combinations can also result in the supervision of originally applied equivalence classes, properties, and binary relations.

Optional simulations-based evaluations can be realized automatically, making it easier to increase the number of the tested combinations and of the learning steps. However, in case of manual evaluation by experts, the workload limits the extensive investigations.

The functioning of RPS-based algorithm can be summarized as follows:

- At the beginning, based on experts’ knowledge, an initial RPS structure (i.e., the equivalence classes, the features within these classes, and the binary compatibility relations between these features) is determined.

- In the most sophisticated general case, the uncertain knowledge, associated with the minimal (binary) relations, is described by the evaluation distribution of the formerly tested complete (maximal) combinations, containing the given two features. In the actually used simplified solution, the uncertain knowledge is described by the domain of this distribution function, represented by a sub-interval [m, M] within the [0, 1] interval.

- At the beginning, all binary relations are evaluated with ‘lack of knowledge’, as a special description of ‘unknown’ case (m = 1 and M = 0).

- While learning from experts and/or from simulations, these intervals are characterized by the values of the formerly tested worst (m) and best (M) evaluations of the given binary relations.

- An increasing number of evaluations results in widening intervals, moreover, in a marginal case; these sub-intervals may cover the whole [0, 1] interval. Nevertheless, the narrower sub-intervals contain usable uncertain knowledge about the applicability of the given binary relations.

- The selection of the subsequent features from the equivalence classes to the next complete combinations is algorithmically controlled by various selection strategies, as follows:

- maxmax: maximize the upper bound M, i.e., the best value;

- maxmin: maximize the lower bound m, i.e., the worst value;

- maxave: maximize the average value;

- unknown: prefer the still unknown binary relations (where m = 1 and M = 0);

- minunc: minimize the uncertainty, i.e., prefer the shorter sub-intervals;

- mintry: prefer the less frequently used elements;

- random: prefer random choice from a subset of the above options.

- In a multi-objective (or multi-expert) evaluation, the Reevaluable Possibility Space can be multiplied for each objective (or expert). In this case, the intersections of the sub-intervals [m, M] for the various objectives (or experts) express a consensus evaluation, while the conflict of objectives can be algorithmically determined by subtracting the consensus from the aggregation. Next, the parallel evaluations will start with the consensus-containing knowledge base, stepwise.

- To decrease the experts’ workload, consensus evaluation of multiple experts can be replaced by aggregation of their evaluations in the same knowledge base as we applied it in our work. However, it is worth mentioning that aggregation increases uncertainty.

3. Results

3.1. Equivalence-Classified Properties of the Investigated Set of Computer-Supported Problem Solving for Sustainable Manufacturing

Equivalence classifications are complete and disjunct classifications of the properties, describing the underlying entities. This means that each entity must be characterized by one and only one property from each class. This feature needs the conscious and appropriate selection of the classes and the classified properties. This is a heuristic but systemic way to declare one part of the ‘a priori’ initial knowledge.

3.1.1. Property Classes and Properties of Manufacturing Tasks

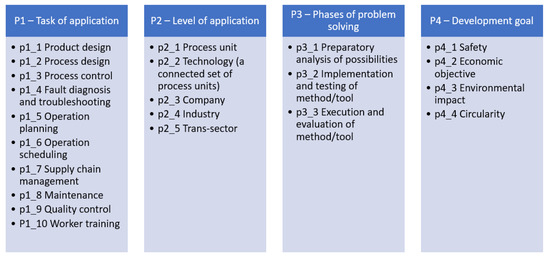

The manufacturing tasks to be solved can be characterized by the property classes and properties presented in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Property classes and properties of manufacturing tasks.

The characterization of manufacturing tasks by equivalence-classified categories comprises four classes, namely the task of application, the level of application, the phase of problem solving, and the evaluating objective of the given task. This creates a systematic approach allowing for a clear and comprehensive understanding of manufacturing operations and related management objectives that need support from conventional and/or AI/ML computational methods.

Property class 1, ‘Task of application,’ groups manufacturing tasks according to their functional role within the manufacturing process. By organizing tasks in this manner, companies can effectively allocate resources, streamline workflows, and ensure that each aspect of the manufacturing process is handled by specialized teams or systems designed to maximize performance in that specific area.

The main benefits of specialization are increased efficiency and improved quality through more streamlined workflows, with each team focusing on a specific set of activities. Reduced task-switching and downtime enhances overall output, technology is specifically designed for each task, and specialized teams are more likely to identify inefficiencies and opportunities for improvement, driving continuous optimization of the manufacturing process. Implementing a task-specific manufacturing organization requires thoughtful resource allocation, special attention to cross-functional coordination, investing in training and development, and proper technology selection and integration [74,75].

Property class 2, ‘Level of application,’ structures manufacturing tasks based on the scale at which they operate, from the granularity of individual process units to the broad scope of trans-sector influences. This distinction allows for tailored strategies that address the unique challenges and opportunities at each level, ensuring that solutions are both effective and appropriately scaled.

The process unit level encompasses the basic building blocks of manufacturing, where specific tasks are performed, such as mixing, heating, or assembling. The goal at this level is the optimization of individual operations for efficiency, safety, and quality. For best results, the unit must maintain operational excellence, minimize downtime, and integrate with upstream and downstream units.

The technology level integrates process units to accomplish a broader manufacturing goal, such as a production line. The strategic focus is to ensure seamless integration and coordination between process units to optimize the flow of materials, information, and energy. This involves systems thinking and cross-functional collaboration. At this level, the challenges are to balance flexibility and efficiency, adapt to new production technologies, and manage technology lifecycles [20].

The company level comprises all of the manufacturing operations within a single organization. It aligns the manufacturing strategy with overall business objectives, such as market responsiveness, sustainability, and innovation. Resource allocation, talent management, and corporate culture are key considerations. This level is challenged by market dynamics, ensuring a skilled workforce, and fostering innovation while maintaining operational excellence [76].

The industry level is defined as the collective of companies operating within the same manufacturing sector, sharing common markets, technologies, and regulatory environments. This level focuses on industry-wide innovation, standardization, and cooperation to address shared challenges and opportunities, such as sustainability and global competition. This level is challenged to anticipate and adapt to industry trends, regulatory changes, and global market shifts [74].

The trans-sector level encompasses the interaction of the manufacturing industry with other sectors of the economy and society, including cross-industry collaborations and impacts on communities and the environment. This level involves engaging with stakeholders across sectors to create value that extends beyond the industry. Focused examples are sustainability, circular economy principles, and societal contributions. The challenges of this level are the following: balancing economic, environmental, and social objectives, navigating complex stakeholder landscapes, and fostering innovation that benefits multiple sectors [77].

Understanding the ‘Level of application’ offers a comprehensive lens through which to view manufacturing tasks, enabling strategies that are finely tuned to the specific challenges and opportunities at each level. This approach encourages a holistic view of manufacturing, where decisions made at the process unit level are informed by and contribute to objectives at the company, industry, and even trans-sector levels. By appreciating the interconnectedness of these levels, manufacturers can create more resilient, efficient, and sustainable operations.

Property class 3, ‘Phases of problem solving,’ clusters tasks into chronological stages. This approach ensures a systematic progression through problem-solving phases, facilitating thorough analysis, careful planning, and effective execution.

The preparatory analysis of possibilities aims to thoroughly explore and analyze potential solutions before committing resources to implementation. This phase involves identifying the problem, researching existing solutions, brainstorming new possibilities, and assessing the feasibility of various options.

The implementation and testing of the method/tool focus on translating chosen solutions into practical applications within the manufacturing process. This phase includes the development or adaptation of tools and methods, followed by rigorous testing to ensure they meet the desired criteria.

The execution and evaluation of the method/tool deploy the tested solution within the operational environment and assess its impact. This stage involves monitoring the implementation, collecting performance data, and evaluating outcomes against objectives.

The ‘Phases of problem solving’ classification promotes a structured approach to tackling manufacturing challenges, from initial analysis through to execution and evaluation. By systematically progressing through these phases, manufacturers can enhance the precision and effectiveness of their problem-solving efforts. This approach not only ensures that resources are allocated wisely but also fosters a culture of continuous improvement and innovation within the manufacturing process. Implementing this framework requires a commitment to disciplined project management, effective communication, and a willingness to adapt based on evidence and feedback [78].

Property class 4, ‘Development goals, organizes manufacturing tasks according to primary objectives, ensuring that operational activities are aligned with overarching goals. This classification acknowledges the multifaceted nature of manufacturing priorities, which extend beyond mere economic outcomes to include safety, environmental sustainability, and circularity.

The safety objective prioritizes the health and safety of employees, customers, and communities. This includes implementing robust safety protocols, hazard analysis, and emergency preparedness while balancing cost and efficiency.

The economic objective is to optimize financial performance through cost reduction, revenue growth, and resource efficiency. This encompasses improving productivity, minimizing waste, and leveraging economies of scale. The challenges are navigating economic fluctuations, managing supply chain complexities, and investing in innovation without compromising short-term financial goals.

Environmental impact is a multi-dimensional objective. The main aim is to minimize the ecological footprint of manufacturing activities. This involves reducing emissions, conserving resources, and implementing sustainable practices. In addition to that, awareness of your handprint—what your products and services enable downstream partners to do to reduce their footprint—is crucial for decision-making. Environmental impact optimization is achieved by embedding environmental sustainability into the core of manufacturing operations and aligning environmental initiatives with economic objectives [77].

Circularity embraces the principles of the circular economy, aiming for a zero-waste lifecycle by designing products for reuse, recycling, and recovery. An advanced level of sustainability, circularity prioritizes resource efficiency in process and product development and aims to extend product lifecycles and to regenerate natural systems. Its barriers are market demand for circular products and the integration of circular principles into the supply chain [79].

By classifying manufacturing tasks according to ‘Development goals’, companies are encouraged to adopt a holistic view of manufacturing, where economic performance is pursued alongside safety, environmental stewardship, and circularity. Implementing this framework requires a strategic alignment of tasks with these diverse objectives, necessitating cross-functional collaboration, innovative thinking, and a commitment to continuous improvement.

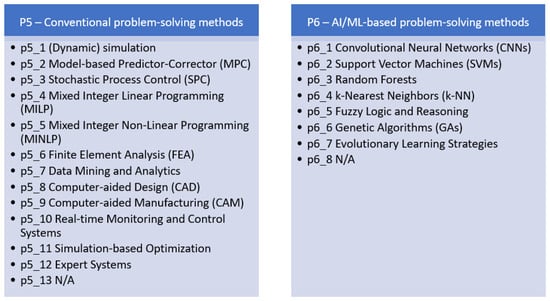

3.1.2. Property Classes and Properties of Computational Problem-Solving Methods

The problem-solving methods can be characterized by the property classes and properties, presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Property classes and properties of computational problem-solving methods.

In the expansive landscape of computational problem-solving, two primary clusters of methods stand out, each embodying distinct philosophies and applications: conventional computational methods and AI/ML-based techniques. These paradigms not only represent different approaches to solving problems but also reflect the evolution of the field from rule-based processing to data-driven learning.

Property class 5 (conventional problem-solving methods) is grounded in established algorithmic principles and has been instrumental in optimizing manufacturing processes. These methods include optimization algorithms for resource allocation, scheduling algorithms to maximize production efficiency, and simulation models to assess the environmental impact of manufacturing activities. By applying these deterministic and rule-based approaches, manufacturers can significantly reduce waste, improve energy efficiency, and optimize the use of raw materials. For example, linear programming can be employed to streamline supply chains, ensuring that materials are sourced and used in the most efficient way possible, minimizing transportation emissions and resource depletion [80].

Property class 6, ‘AI/ML-based problem-solving methods,’ on the other hand, introduces dynamic, data-driven capabilities to sustainable manufacturing. By analyzing large datasets, Machine Learning models can predict maintenance needs, thereby reducing downtime and extending the lifespan of equipment. Neural networks analyze patterns in production data to identify inefficiencies and suggest improvements, while reinforcement learning algorithms optimize complex, multi-variable operations in real-time for maximum outcome and sustainability. AI-driven anomaly detection systems monitor environmental conditions, ensuring compliance with environmental regulations and standards. The adaptive nature of AI/ML methods enables them to tackle complex sustainability challenges, such as adapting to variable renewable energy sources in manufacturing processes or optimizing product designs for circularity [81,82].

Both classes of computational problem-solving methods are invaluable to sustainable manufacturing, offering complementary approaches. While conventional methods provide a solid, reliable foundation for optimization and efficiency, AI/ML-based techniques bring the adaptability and foresight needed to navigate the complexities of both productivity and sustainability. Together, they empower manufacturers to not only achieve operational excellence but also advance toward a more sustainable and environmentally friendly future. A detailed interpretation of method- and tool-related notions and concepts is found in Supplementary Material S1.

3.2. Initial Compatibility Structure of the Binary Relations Between the Property Classes

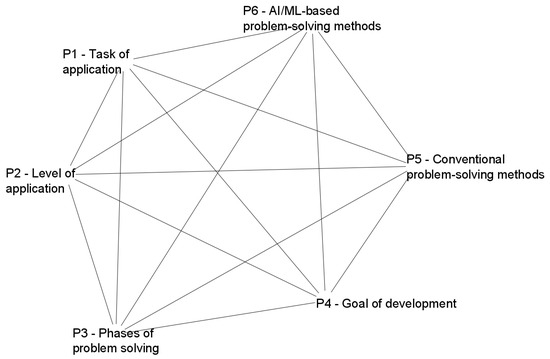

First, the existing compatibility relations between the property classes must be determined. By default, it may be a full network, as can be seen in Figure 3. Nevertheless, some relations between two equivalence classes may not contain additional restrictions because the other binary relations determine the whole ‘design space.’ This can be taken into consideration according to the literature analysis, as well as by the heuristic knowledge of experts.

Figure 3.

Relations among the property classes P1–P6.

Figure 3 shows the binary relations among the property classes P1 through P6. The six nodes are connected by all possible 15 edges to begin with. Feasibility of property pairs is investigated in Section 4.

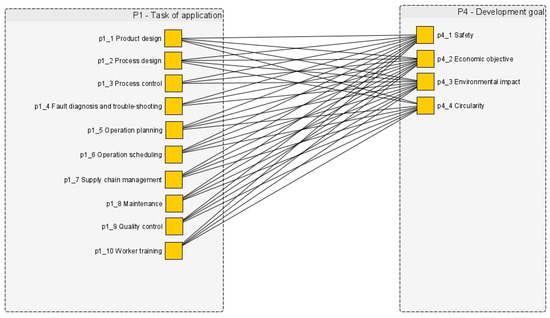

Exemplary for all possible binary relations, Figure 4 shows binary relations among properties of the property classes P1 and P4. At this level of granularity, irrelevant combinations have been removed, i.e., the relations between process control (p1_3) and circularity (p4_4).

Figure 4.

Exemplary graphic representation of the binary combinations (edges between yellow squares) of properties (represented by yellow squares) between the property classes P1 and P4.

Initially, the binary combinations can be evaluated by the ’lack of knowledge’ value in the sense of the four-valued logic. This includes the apparent paradox of the [1, 0] case, where m = 1 and M = 0. Accordingly, the given binary combination may also be evaluated by 1 in the worst case and by 0 in the best case. Consequently, any evaluation of a newly studied combination can initiate the first realistic evaluation for the given binary combination. An experienced expert can modify the zero knowledge by adding other initial evaluations in form of heuristically declared [m, M] intervals, of course. Nevertheless, automatic learning from the evaluated complete combinations may be more convenient.

3.3. Description of the Complete Combinations

According to the applied methodology, the complete combinations, describing an actual task and the applied conventional and/or AI/ML-based methods, are described by sets of properties, containing one and only one element from each property class. In line with the SWI-Prolog representation of applied algorithms, the complete combinations are described by rmax() predicates, according to the following syntax:

where

rmax(XY, ID, Nu, Plist, Evallist)

- XY = identifier of expert evaluator;

- ID = identifier integer;

- Nu = number of occurrences;

- Plist = list of properties, participating in the given combination;

- Evallist = contains evaluation of the given complete combinations.

As an example, an actual rmax() predicate is shown as follows:

rmax(dw, 11, 1, [p1_10, p2_3, p3_3, p4_2, p5_11, p6_6], [0.7])

In this complete combination example, the expert with the initials ‘dw’ evaluated the 11th complete combination of a set of complete combinations which previously has not been evaluated. Its description is as follows:

- Task of application: worker training (p1_10);

- Level of application: company (p2_3);

- Phase of problem solving: execution and evaluation of method/tool (p3_3);

- Evaluation objective: economic objective (p4_2);

- Conventional problem-solving method: Simulation-based Optimization (p5_11);

- AI/ML-based problem-solving method: Genetic Algorithms (p6_6).

Listing one property of each property class, this complete combination describes an application of executing and evaluating a tool for a case of worker training on the company level. An economic objective is pursued, and the combined problem-solving methods to be evaluated are Simulation-based Optimization and Genetic Algorithms.

In this example, the expert with the initials ‘dw’ evaluates the given complete combination with a 0.7 on a scale from 0 to 1.0.

3.4. Description of the Binary Relations Between the Classified Properties

Binary relations represent the relevance and the uncertain evaluation of the actual pair of properties, belonging to two equivalence classes. Again, in line with the SWI-Prolog representation of applied algorithms, the binary relations are described by rmin() predicates according to the following syntax:

where

rmin(XY, ID, YN, Freq, Classes, Properties, Vmin, Vmax, Unc, Vav, Forget)

- XY = identifier of Expert evaluator;

- ID = identifier integer;

- YN = to be considered by default y (it means that it is considered during the evaluation);

- Freq = number of reevaluations (by default 0 at the very beginning, and will be overwritten during the evaluations);

- Vmin = minimal value (initial lack of knowledge considered by 1);

- Vmax = maximal value (initial lack of knowledge considered by 0);

- Unc = uncertainty, Unc = Vmax-Vmin;

- Vav = average value, Vav = sign (Unc) ∗ average (Vmax, Vmin);

- Forgetting = the status of the optional forgetting steps, by default 0.

As an example, an actual rmin() predicate is shown as follows:

rmin(dw, 456, y, 13, [p2,p6], [p2_4, p6_2], 0.1, 0.8, 0.7, 0.45, 0)

In this example, the expert with the initials ‘dw’ evaluated the relation #456 which has been evaluated 13 times. The property classes P2 Level of application and P6 AI/ML-based problem-solving methods are included, specifically the binary relation between the two properties p2_4 Industry and p6_2 Support Vector Machines. For this binary relation, the pessimistic value Vmin is 0.1 and the optimistic value Vmax is 0.8; the uncertainty Vmax-Vmin is therefore 0.7. The average value is 0.45.

At the beginning, all binary relations are considered to be ‘unknown.’ It corresponds to the apparently paradoxical evaluation of m = 1 and M = 0, while in this case the given binary combination is evaluated by 1 also in the worst case and by 0 also in the best case. Accordingly, if the first evaluation for a binary relation appears, then the ‘unknown’ case will change for the case of m = M = first value. The same binary relation may occur in other combinations of various values later on, so this will outline a [m, M] interval for the evaluation of the given binary relation. Furthermore, in the initial ‘unknown’ case, Freq is 0, Unc is −1, and Vav is −0.5. A complete initial knowledge base, containing 733 binary relations between the 15 property classes, can be found in the file of Rmin_0.pl in the respective repository [83].

3.5. Overview of the Algorithm in the Sense of Reevaluable Possibility Space

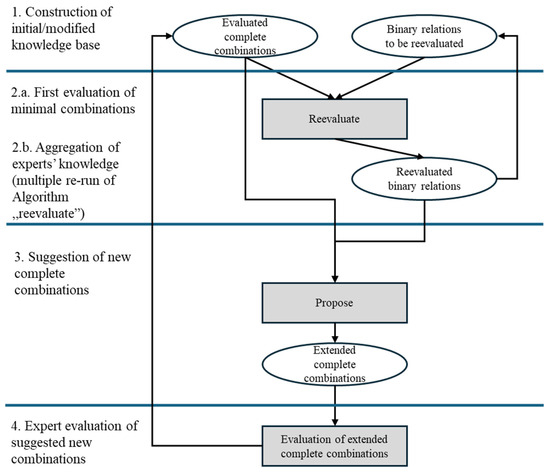

The simplified scheme of the evolving knowledge base (in form of reevaluated binary relations) can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Simplified scheme of the evolving knowledge base of evaluated binary relations.

Ellipses symbolize Rmax files, containing an actual set of possible alternative solutions (scenarios) in the form of rmax() complete combinations, as well as Rmin files, containing rmin() binary relations, corresponding to the actual state of the evolving knowledge base. Rectangles symbolize computational algorithms or a human expert’s activity. More detailed interpretations of these elements are the following:

Evaluated complete combination: First input file of Algorithm ‘reevaluate’ that contains previously evaluated rmax() combinations only. At the very beginning it was filled by 300 complete combinations, evaluated preliminarily. Also, it serves as an input file of Algorithm ‘propose’.

Binary relations (knowledge base) to be reevaluated: Second input file of Algorithm ‘reevaluate’ that contains an actual state of rmin() relations. At the very beginning it was filled with lack of knowledge (with ‘unknown’ m = 1 and M = 0) evaluations according to file Rmin_0.pl.

Reevaluate: Reevaluates the above binary relations by the above evaluated combinations, resulting in a reevaluated knowledge base. Essentially, the algorithm takes all the possible property pairs in each complete combination and modifies the respective m and M values, as well as the other attributes in the knowledge base.

Reevaluated binary relations (knowledge base): The result of Algorithm ‘reevaluate’ (that incorporates the upgraded knowledge) and the first input file of Algorithm ‘propose’.

Propose: Extends the available complete combinations with new ones in the knowledge of the reevaluated binary relations of the last knowledge base. The configuration and parameterization of the algorithm will be discussed in Section 3.6.

Extended complete combinations: The result of Algorithm ‘propose’ and the input for expert’s evaluation.

Evaluation of suggested new combinations: Made by (optionally multiple) experts, while the new combinations will obtain a normalized value, heuristically.

The evaluated complete combinations can be used to reevaluate the knowledge base (see the arrow, representing the respective feedback on the left-hand side of Figure 5). The last version of reevaluated binary relations can be applied for further reevaluation of the knowledge base (see the respective feedback on the right-hand side of the Figure 5).

In this work, three experts were involved in a single workflow of the above procedure, and their specific knowledge was aggregated (resulting in higher uncertainty, of course).

It is to be noted that in possible other applications of the methodology (especially if the evaluation of complete combination can be automatized by, e.g., simulations), the evaluations, according to optionally multiple objectives, can run in parallel (by parallel running of the above scheme), while from time to time, consent (and conflict) evaluations can be generated for the following in-parallel execution.

3.6. Computational Representation of the Algorithm

The above discussed algorithm was implemented in SWI-Prolog language (https://www.swi-prolog.org/). The program code has been developed as a special application of the theoretical framework of RPS, described in Section 3.2. The developed source code is presented in Supplementary Material S2. The source code and the executable program together with the applied data files can be found in the respective repository [83].

The actual run of the program is controlled by a defined task() predicate, according to the following syntax:

where

task(Program, From1, From2, To, Input_parameters)

- Program = the algorithm to be executed;

- From1, From2 = the names of input files in the necessary syntax (i.e. within ‘’);

- To = the name of output file in the necessary syntax (i.e. within ‘’);

- Log = the name of the respective log file in the necessary syntax (i.e. within ‘’);

- Input_parameters = the list of algorithm-dependent input parameters in the necessary syntax (i.e. within []).

Essentially, we use parameters only for the ‘propose’ algorithm.

The file containing the actually used task() predicates can be found in the respective repository ([83] in Task.pl).

Two kinds of tasks are used, as follows:

- Algorithm = ‘reevaluate’, which modifies the knowledge base of minimal binary relations by the evaluations, coming from an actual set of evaluated complete combinations; and

- Algorithm = ‘propose’, which suggests new complete combinations, determined by the applied techniques:

- Selection strategies of binary relation classes (random order or normal order), and

- Selection strategies from the individual classes (random, maxmin, maxmax, maxave, unknown, minunc, mintry).

Program ‘reevaluate’ results in an updated knowledge base of binary relations, as well as some automatically calculated features, as follows:

- The number of binary relations;

- The number of unknown binary relations;

- The number of reevaluated binary relations;

- The absolute value of uncertainty for the unknown binary relations;

- The uncertainty of reevaluated binary relations.

Program ’propose’ suggests a prescribed number of new complete combinations to be evaluated, as well as some automatically calculated features, as follows:

- The number of maximal relations;

- The number of suggested new maximal relations;

- The sum of maximal relations with repetition;

- The sum of suggested new maximal relations without repetition.

Running ‘propose’ depends on the respective [Actual_rmax_number, Suggested_new rmax_number, Selected_ordering, Selected_strategy] parameters representing the following modes of the run:

- Actual_rmax_number: the number of the already existing evaluated combinations;

- Suggested_new rmax_number: number of new combinations to be proposed;

- Selected_ordering of pairs of property classes: actual order or random order;

- Selected_strategy: maxmax or maxmin or maxave or unknown or minunc or mintry or random. Essentially, random is limited to maxmax or maxmin or maxave or unknown.

Reproducibility of randomization can be solved by tracking the run in an automatically generated log file.

3.7. Workflow of Case Studies

The overall workflow of the case studies is summarized as follows. Corresponding files can be found in the respective database to ensure reproducibility of the work.

- Construction of initial empty knowledge base and the initial set of evaluated complete combinations

The workflow started from zero initial knowledge about the evaluation of complete combinations and minimal binary elements. Accordingly, all binary relations were characterized by the lack of knowledge (m = 1, M = 0). After having finalized the structure of the knowledge base and having evaluated a preliminary set of complete combinations, we started from 300 complete combinations (Rmax_full1.pl in the repository of [83], evaluated by DW, initially). Furthermore, we selected a subset of 50 (good and bad performing) solutions; additionally, involved experts were asked to evaluate this set of initial complete combinations blindly (so the experts did not know of each other’s evaluation results) with a real number from the [0, 1] interval, as well as the new complete combinations later on, generated by the algorithm. Experts were informed about the criteria of the evaluation to ensure reasonable comparability. They were tasked to combine the following three aspects into a single scoring:

- Feasibility—Experts should consider whether the complete combinations can realistically be implemented, both technically and operationally.

- Possibility of success—Experts should consider the likelihood whether the specific complete combination will solve the problem, if implemented.

- Value added—Experts should consider the expected contribution or the complete combination toward the defined development goal.

In this way, this value had to express their general opinion about the given combination, i.e., the solution of a given class with a given conventional or AI/ML-based method (i.e., V = 1 if the expert agrees that it is a well-applicable solution, and V = 0 if expert considers solution inapplicable).

Involved experts included the following:

- Thomas Hohnloser, Chief Information Officer, Infraserv Wiesbaden Gmbh & Co. KG. InfraServ Wiesbaden is the operating company of an industrial park in Wiesbaden Germany.

- Steffen Robus, IT project leader, Deka Bank Deutsche Girozentralehttps://www.linkedin.com/in/steffen-robus-b94011163/ (accessed on 6 October 2025). Before the current occupation, Steffen Robus was General Manager, S-Servicepartner Consulting GmbH, the inhouse IT consultancy of the German Sparkassen.

- Dennis Weber, PhD candidate, first author of this paper, and Sustainability Communications Manager at Corning Incorporated. Corning Incorporated is a global manufacturing company in the material science space.

Because the evaluated combinations are both numerous and complex, expert assessments may inevitably incorporate subjectivity. Nonetheless, these evaluations remain highly valuable, as they synthesize domain-specific knowledge and enable informed judgments across a wide array of multifaceted configurations. Although the model relies strongly on these assessments, the consideration of multiple experts’ opinions can decrease the effects of subjectivity.

Involvement started with online one-to-one meetings, focusing on the presentation of the task, the introduction of the defined property classes and the properties within them, as well as the utilized method for evaluation. Experts were involved based on a convenience sampling, considering particularly their expertise, proven by many years of practical experience. Experts agreed to share their identity regarding this article with their written consent.

Accordingly, the algorithm started to run with the following information, structured in the respective files, as follows:

- Rmin_0.pl: The set of minimal combinations, containing 733 binary relations between the properties of the 15 property classes. Initially, it was filled with zero knowledge.

- Rmax_full1.pl, Rmax_DW1.pl, Rmax_TH1.pl, and Rmax_SR1.pl files (DW, TH, and SR refer to the initials of involved experts), which contain the 300 as well as the 50–50 maximal combinations, evaluated by the involved experts.

- 2.

- First reevaluation of minimal combinations

Based on the previously mentioned files, the ‘reevaluate’ task of the algorithm results in the reevaluated knowledge bases Rmin_full1.pl, Rmin_DW1.pl, Rmin_TH1.pl, and Rmin_SR1.pl. These files started to be filled with reevaluations of the minimal relations that have obtained calculated values, based on their performance in the maximal combinations.

- 3.

- Aggregation of experts’ knowledge

In these steps, the opinions of various experts are aggregated in the knowledge base, with execution of the respective ‘reevaluate’ tasks. During this procedure, the ‘reevaluation’ is repeated in three consecutive steps, using the following files:

- Rmax_TH1.pl and Rmin_DW1.pl: The 50 maximal combinations, evaluated by expert TH, reevaluate the knowledge base of minimal combinations, coming from the former step, based on expert DW’s evaluation. This run results in the Rmin_DW1TH1.pl.

- Next, Rmax_SR1.pl reevaluates the formerly obtained Rmin_DW1TH1.pl, resulting in the Rmin_DW1TH1SR1.pl file that considers and aggregates the opinion of the third expert, represented in the (possibly) widening intervals in the binary combinations in the new Rmin_DW1TH1SR1.pl.

- Finally, the Rmax_full1.pl complete combinations reevaluate the former Rmin_DW1TH1SR1.pl, considering all the uncertain knowledge of the intervals of the binary relations in Rmin_DW1TH1SR1full1.pl.

It is to be noted that the aggregation process is commutative, associative, and idempotent, so the result is invariant for the order of aggregating steps.

- 4.

- Suggestion of new complete combinations

In the knowledge of a Rmin set of aggregated binary relations and a Rmax file of former set of rmax() maximal combinations, the ‘propose’ algorithm suggests new possible maximal combinations, resulting in an extended Rmax file to be evaluated by the experts.

- 5.

- Expert evaluation of suggested new combinations

The experts evaluated these new suggested combinations. In the actual case study, blind expert evaluation of the 50 complete combinations was conducted, so the experts did not know of each other’s evaluation results.

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolution of the Binary Knowledge Base

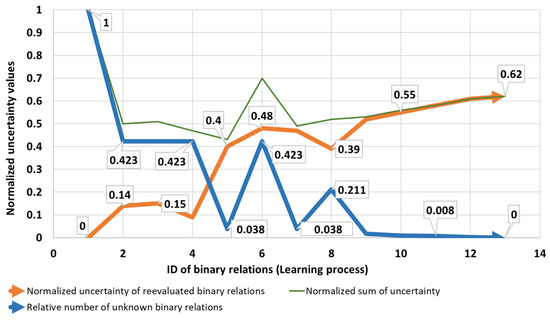

Table 1 summarizes the case studies. Accordingly, it contains the name of the actual Rmin knowledge base, the name of the respective Rmax file (from which Rmin was reevaluated lastly), the acronym of the evaluating expert, the new Rmax files, containing the newly proposed rmax() combinations, as well as the assessment of the actual state of the Rmin file. This assessment considers the following:

Table 1.

Quantitative report on the evolution of the binary knowledge base.

- The number of binary relations;

- The number of unknown binary relations (expressing the temporary lack of knowledge);

- The number of reevaluated binary relations;

- The absolute value of the uncertainty of unknown binary relations;

- The uncertainty of reevaluated binary relations; and

- The sum of uncertainty, which is the sum of uncertainty for the unknown and reevaluated binary relations.

- Uncertainty values were calculated according to Equations (18)–(21). Table 1 and Figure 6 illustrate the average uncertainty of lack of knowledge (unknown binary relations), the average uncertainty of reevaluated binary relations, as well as the sum of two kinds of uncertainty. It is to be noted that negative uncertainty of lack of knowledge was replaced by its absolute value for the proper representation.

Figure 6. Development of uncertainty of binary relations.

Figure 6. Development of uncertainty of binary relations.

The uncertainties of the binary relations in the knowledge base are developing with each reevaluation cycle, as Table 1 shows. Accordingly, the uncertainty from the ‘lack of knowledge’ is decreasing from 1 to 0, while the uncertainty of the reevaluated binary relations slowly increases from 0 to 0.62. Nevertheless, the sum of these two kinds of uncertainties first decreases, then slowly increases, as shown in Figure 6 below. It expresses that the uncertainty from the lack of knowledge turns into uncertainty of accumulating knowledge. Meanwhile, it results in a continuous accumulation of useful information in the Rmin knowledge base.

Figure 6 shows clearly that the lack of knowledge was eliminated during the learning process completely (normalized uncertainty decreased from 1 to 0), while relative uncertainty of knowledge increased from 0 to 0.62.

4.2. Evaluation of the Suggested Complete Combinations (Rmax)

With each round of evaluation, new complete combinations were suggested by the algorithm. Rarely repeating a suggestion, the algorithm grows its knowledge base.

In line with the accumulated knowledge in binary relations, the consecutive runs suggest continuously good and bad solutions, while the good solutions may contain advantageous combinations. Analyzing the 50 newly suggested and evaluated combinations of Rmax_DW1TH1SR1full1_650, 10 combinations (20%) are evaluated ≥0.8, and 20 combinations (40%) ≥ 0.7. Those are high percentages of good combinations compared to the initially suggested combinations, underlining the conclusion.

Listed in Table 2 are the top ten and the lowest ten combinations of the 50 newly suggested combinations in Rmax_DW1TH1SR1full1_650, while these example combinations illustrate the actual state of the knowledge base to be developed further.

Table 2.

The ten highest and ten lowest evaluated newly suggested combinations of Rmax_DW1TH1SR1full1_650.

A disproportionate occurrence of properties indicates above-average advantage for the development of the knowledge base, as it highlights good and bad relations. To identify disproportionate occurrences and allow qualitative interpretation at the same time, two groups of the 50 newly suggested combinations of Rmax_DW1TH1SR1full1_650 are focused on: the top ten evaluated complete combinations and the lowest ten evaluated complete combinations.

Disproportionate occurrences of properties among the top ten evaluated complete combinations:

- p1_6 Operation scheduling (four out of ten combinations);

- p3_1 Preparatory analysis of possibilities (6 out of 10 combinations);

- p4_1 Safety (four out of ten combinations);

- p6_8 N/A (four out of ten combinations; that means in these cases no AI/ML methods are combined with conventional methods).

Disproportionate occurrences of properties among the lowest-ten evaluated complete combinations:

- p2_1 Process unit (five out of ten combinations);

- p3_1 Preparatory analysis of possibilities (7 out of 10 combinations);

- p4_1 Safety (four out of ten combinations);

- p6_1 Convolutional Neural Networks (five out of ten combinations).

Four of the top ten combinations (evaluated ≥0.8) do not feature an AI/ML-based method (p6_8 N/A). Of the 50 newly suggested combinations, 12 feature p6_8 N/A, representing a high percentage of combinations without AI/ML-based problem solving. This indicates that AI/ML-based problem-solving methods are not deemed advantageous in the knowledge base at this stage. The same 50 newly suggested combinations do not show a disproportionate occurrence of the p5_13 N/A, combinations where no conventional problem-solving method is applied. Beyond the high occurrence of p6_8 N/A, the currently most hyped AI method Convolutional Neural Networks is only found once in the top ten combinations (evaluated ≥0.8) but five times in the lowest ten combinations (evaluated ≤0.3). The low evaluation of AI/ML problem-solving methods, especially CNNs, is remarkable but could be rooted in the opinions of the three experts. To find out whether this result is a representation of the expert opinions or an actual lack of solving power of AI/ML methods applied in manufacturing, the base of experts would need to be extended.

Operation scheduling (p1_6) is deemed an extraordinarily advantageous task to be solved, while the process unit (p2_1) is the least advantageous level within the focused complete combinations.

A significantly disproportionate occurrence of p3_1 Preparatory analysis of possibilities and p4_1 Safety among both the top ten and lowest ten evaluated complete combinations is remarkable, indicating that those two properties have a high probability of being solved with computational problem-solving methods. Yet again, this finding could be rooted in the opinions of the three experts. To find out whether this result is a representation of the expert opinions or an actual peak of solving power of computational methods applied in manufacturing, the base of experts would need to be extended.

4.3. Evaluation of the Final State of the Binary Knowledge Base

To evaluate the binary knowledge base, the 733 binary relations are ordered by the 15 class pairs, considering the Uncertainty, the Frequency, and the Average values of the respective binary relations (regarding the final state of the knowledge base, the Rmin/Rmin_DW1TH1SR1full1_7.pl in the repository of [83]).

Analyzing the averages of the paired classes (average Frequency, average Uncertainty, and average Av. value), the average Av. values appear trending around the middle value 0.5, independent of the Frequency and the Uncertainty. This is in accordance with the last column of Table 2, underlying that in this phase of knowledge gathering, the elimination of lack of knowledge by the ‘minimize unknown’ selection strategy introduces new relations participating in both good and bad combinations. In future applications, more iterative steps are recommended after having eliminated the lack of knowledge.

In the case of the average Frequency and the average Uncertainty, a strong correlation can be identified (correlation coefficient r = 0.86). Low average frequencies correlate with low uncertainty averages and vice versa; see Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Correlation between average Frequency and average Uncertainty in paired classes.

The correlation indicates that an increased Frequency of binary relations among property classes leads to an increased Uncertainty. This is a consequence of aggregation, instead of reaching a consensus between the experts, explicitly. Nevertheless, the involvement of multiple experts helps to decrease the bias of expert evaluations against the improper influence on the outcomes. Unfortunately, the underlying possibilistic (fuzzy-like) uncertainty does not allow the statistical analysis of significance, which is a good solution in the case of probabilistic uncertainty.

This can be solved by the independent parallel knowledge base development by the experts, followed by an algorithmic generation of a consensus expressing the Rmin knowledge base. In the next period, the experts follow their parallel (or aggregated) work, based on this consensus file. It needs considerably more expert evaluations, but the accumulating uncertainty can be decreased.

Another possible solution to decrease the accumulated uncertainty may be forgetting the very uncertain binary relations. Accordingly, beyond a certain number of evaluating cycles, the binary relations with high uncertainty can be forgotten temporarily or permanently. It can be solved by changing the ‘forget’ flag at the end of rmin() relations, signing that the actual relation is not taken into consideration in the ‘propose’ algorithm.

Assuming that frequently used relations with high average value and low uncertainty are part of highly feasible solutions; the dataset was filtered accordingly. A total of 48 binary relations have a high Average value ≥ 0.7, 25 of which have a low uncertainty ≤ 0.3. Potentially, those 25 pairs are part of highly feasible solutions. Yet, the frequency of occurrence of those 25 binary relations ranges between 2 and 46; only eight relations occur 30 or more times.

Vice versa, it is assumed that frequently used relations with low average value and low uncertainty are part of low-performing solutions. A total of 54 binary relations has a low average value ≤ 0.35, 14 of which have a low uncertainty ≤ 0.3. Potentially, those 14 pairs are part of low-performing solutions. Yet, the frequency of occurrence of those 14 binary relations ranges between 1 and 60; only four relations occur 30 or more times.

Indicating a functioning algorithm, the strongest average value of 0.9 and a low uncertainty of 0.2 is attributed to the pair p5_7 Data Mining and Analytics and p6_1 Convolutional Neural Networks. The second strongest average value of 0.75 and an uncertainty of 0.1 is attributed to the pair p1_3 Process control and p5_9 Computer-Aided Manufacturing. Both these pairs are naturally fitting partners. Additional pairs with high average values and low uncertainty underline the conclusion of a functioning algorithm: p1_8 Maintenance and p5_10 Real-time Monitoring and Control Systems, p1_9 Quality Control and p5_7 Data Mining and Analysis, and p1_6 Operation Scheduling and p5_11 Simulation-based Optimization.

Analyzing the latest knowledge base, Rmin_DW1TH1SR1full1_7.pl reveals additional interesting findings. As listed in Table 4, filtering property class P1 Task of application, 330 pairs remain out of the total 733 binary relations. A total of 130 of the 330 (39%) are paired with P5 Conventional problem-solving methods. A total of 80 of 330 (24%) are paired with P6 AI/ML-based problem-solving methods. Further analyzing the 25 P1 pairs that reached an Avg. value ≥ 0.7, 23 of them are paired with P5 properties; only one pair features a P6 property. This low presence of AI/ML problem-solving methods among the high Avg. value combinations is remarkable. To find out whether this result is a representation of the expert opinions or an actual lack of solving power of AI/ML methods applied in manufacturing, this needs further investigation.

Table 4.

Analyzing P1 Task of application in the latest knowledge base.

The majority of binaries apply computational problem solving; the conventional problem-solving methods make up two thirds. Task orientation, computational problem solving, and the dominance of conventional problem-solving methods result from the expert input. It would be interesting to seek proof of the hypothesis that is representative for problem solving in manufacturing industries.

A total of 280 pairs feature P6 AI/ML-based problem-solving methods; 390 pairs feature P5 Conventional problem-solving methods. Again, we see a dominance of conventional problem solving. The P5 pairs’ average Uncertainty is 0.51 (Avg. value 0.50). The P6 pairs average a higher uncertainty average of 0.6 at a comparable average Avg. value. The lower Uncertainty average indicates that the P5 pairs provide more impactful new knowledge to the knowledge base. Interestingly, the 84 pairs featuring P5 and P6 properties (excluding pairs with N/A properties) have an even lower average Uncertainty of 0.45, indicating impactful knowledge. Supporting that conclusion, those 84 pairs feature nine pairs ≥ 0.7 Avg. value, equaling 10% of binary relations. The complete database with its 733 binaries counts 48 pairs with ≥0.7 Avg value, equaling 6.5%. Combining P5 and P6 properties leads to binary combinations providing the knowledge base with impactful new knowledge.

Assumptions for qualitative conclusions are the following:

- High uncertainty values indicate potentially trivial relations that do not specify new knowledge for the selection of elements while serving as important lessons for the construction of the evolving knowledge base.

- Low uncertainty values with feasible frequency specify new knowledge for the selection of elements.

- RPS offers unique knowledge representation and fast learning capabilities, resulting from the following features:

- Constructive, equivalence-based classification of the underlying manufacturing tasks, properties, and of the corresponding methodologies or methodological combinations.

- Characterization of the relations between properties—including their commutative and associative features—within these methodological combinations; in graph-theoretic terms, these relations are represented by undirected edges.

- Primarily possibilistic rather than probabilistic formulation of uncertainty, reflecting the nature of the information involved.

- Coherent representation of incomplete or missing knowledge, ensuring internal consistency.

- Formal expressions of key characteristics of evaluation distributions, especially those derived from heuristic values proposed by experts.

- Algorithmic construction of aggregation procedures, with optional computation of consensus evaluations across multiple experts.

- Considering the comparison with other existing methods summarized in Section 1.4, the available alternative approaches (e.g., Bayesian updating or Active Learning) are not exactly tailored to the demands of the investigated method discovery task.

- In contrast to the probabilistic Bayesian approach, evaluation distribution can be interpreted as a possibilistic uncertainty in our case. Furthermore, as an important difference, the underlying problem can be formulated with compatibility relations (i.e., in form of non-directed graphs), where all the maximal combinations form complete cycles (unlike directed acyclic graph representation in case of the referred Bayesian methods).

- Active Learning applies a causality-driven selection according to associative but not commutative relations. In comparison, RPS is based on commutative relation-based, compatibility-driven problem solving.

- Genetic Algorithms (or their variant, genetic programming) do not know about the explicit structure (property classes, properties, relations) of the possibility space. Accordingly, the number of trials with GA is considerably higher than in the case of RPS, where the structure of the possibility space is fully pre-defined. GAs would impose an infeasible workload on experts tasked with the evaluation.

- The main limitation of the implemented methodology is the necessary manpower of experts’ evaluation. This obviously limits the number of iterative feedback cycles, also in the context of using an automatic consensus, instead of the uncertainty-increasing aggregation. However, this limitation can be avoided if we use the method for another class of problems, when evaluation of complete combinations can be generated based on some simulation-like calculations, automatically. Regardless, in future work it would be straightforward to apply a stepwise consensus, followed by the in-parallel evaluation, based on this consensus by multiple experts. A consensus can be generated as the intersection of the uncertainty intervals, coming from the evaluation of in-parallel working experts. Also, a conflict of opinions can be generated by calculation of aggregation minus consensus. This can essentially decrease uncertainty and helps to develop better, new solutions faster. To decrease manpower, in the knowledge of first evaluations, the combinatorial complexity can be decreased by revision of necessary relations between the property classes and the properties, as it was indicated above.

5. Conclusions

The learning knowledge representation, using a reevaluating algorithm over the lattice of equivalence-classified properties, proved to be applicable for the systemic overview of conventional and AI/ML applications in manufacturing in a way that also supports the algorithmic generation of new solutions from a continuously evolving knowledge base. The proposed algorithms are based on the evaluation feedback between the maximal and minimal elements of a compatibility lattice of the underlying properties.

The practical objective of this work was to systematize the available conventional and AI/ML methods that can be applied to solve various tasks in manufacturing industries. Based on the heuristic evaluation of the related literature, we concluded that the combinatorial complexity of the available methods and tools in context of the tasks to be solved needs a theoretically established systematic approach.

As a first step, we determined six equivalence classes of the properties, describing the combinations of the methods with tasks. Moreover, we determined the binary compatibility relations between these classes, resulting in 15 binary relations between them.

Next, the relations between the elements in the 15 pairs of equivalence classes were examined one after the other, and the possible binary compatibility relations between the underlying properties were determined heuristically, resulting in 733 binary relations.

Accordingly, the possibility space, outlined by the binary relations between the classified properties, was generated. This qualitative knowledge base made it possible to apply an underrepresented intelligent learning methodology for uncertain quantitative determination of the compatibility relations between the conventional and intelligent methods for the solution of various tasks in the manufacturing industry. Accordingly, we applied the theoretically established learning feedback between the complete combinations and the binary relations, determining these complete combinations. The essence of the applied feedback is that a normalized, real valued (within [0, 1] interval) evaluation of complete combinations can generate increasing [m, M] sub-intervals (where 0 ≤ m ≤ M ≤ 1) for the binary relations. The structured set of these sub-intervals contains an uncertain knowledge that, by means of the appropriately developed algorithms, can generate tendentiously better new complete combinations.