Abstract

Reliable bearing fault diagnosis across diverse operating conditions remains a fundamental challenge in intelligent maintenance. Traditional data-driven models often struggle to generalize due to the limited ability to represent complex and heterogeneous feature relationships. To address this issue, this paper presents an Adaptive Multi-view Hypergraph Learning (AMH) framework for cross-condition bearing fault diagnosis. The proposed approach first constructs multiple feature views from time-domain, frequency-domain, and time–frequency representations to capture complementary diagnostic information. Within each view, an adaptive hyperedge generation strategy is introduced to dynamically model high-order correlations by jointly considering feature similarity and operating condition relevance. The resulting hypergraph embeddings are then integrated through an attention-based fusion module that adaptively emphasizes the most informative views for fault classification. Extensive experiments on the Case Western Reserve University and Ottawa bearing datasets demonstrate that AMH consistently outperforms conventional graph-based and deep learning baselines in terms of classification precision, recall, and F1-score under cross-condition settings. The ablation studies further confirm the importance of adaptive hyperedge construction and attention-guided multi-view fusion in improving robustness and generalization. These results highlight the strong potential of the proposed framework for practical intelligent fault diagnosis in complex industrial environments.

1. Introduction

Reliable fault diagnosis plays a crucial role in ensuring the safe and stable operation of rotating machinery, as bearings represent one of the most failure-prone elements in industrial transmission systems [1,2,3]. With the rapid advancement of intelligent monitoring and predictive maintenance technologies, there has been an increasing opportunity to employ advanced data-driven diagnostic models to interpret vibration signals obtained from bearing sensors. Recent progress in deep learning has substantially improved automated feature extraction from raw vibration signals. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly effective in learning discriminative representations by capturing local spatial and temporal features directly from waveform inputs, enabling accurate fault classification. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), on the other hand, are adept at modeling sequential dependencies in time-series data, allowing them to capture the temporal evolution of bearing faults more effectively [4,5]. Compared with conventional manual diagnosis, these deep models significantly improve both performance and automation efficiency. Nevertheless, CNNs and RNNs are inherently designed for Euclidean and grid-structured data, limiting their capacity to represent the non-Euclidean dependencies and heterogeneous interactions frequently encountered in multi-sensor bearing monitoring [6,7]. Consequently, they fall short in fully exploiting the spatio-temporal correlations and cross-condition variability embedded in vibration measurements.

To address the aforementioned limitations, graph-based learning frameworks have recently emerged as powerful tools for modeling non-Euclidean dependencies among multi-sensor vibration signals [8,9,10,11]. Specifically, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have shown strong effectiveness by modeling each sensor signal or feature segment as a graph node, while the dependencies among them are represented through connecting edges [12]. Extending this paradigm, several studies have proposed spatio-temporal graph learning architectures capable of simultaneously capturing both inter-sensor spatial correlations and their temporal dynamics [13,14]. Experimental findings have shown that such graph-based representations can surpass traditional CNN and RNN models in bearing fault identification tasks [15,16]. Nevertheless, most existing graph learning techniques still depend on manually defined similarity metrics or attention-based pairwise links, which constrain their ability to express high-order structural relationships. Consequently, they struggle to model the intricate dependencies among multiple fault-related signals under diverse operating conditions, leading to reduced robustness and limited generalization capability.

To overcome the above challenges, this work introduces an Adaptive Multi-view Hypergraph Learning (AMH) framework for cross-condition bearing fault diagnosis. In contrast to traditional graph models that capture only pairwise connections, AMH employs a hypergraph structure to encode high-order dependencies among multiple feature perspectives. In this framework, vibration data are converted into multi-view feature representations derived from the time, frequency, and time–frequency domains, thereby enabling a richer and more comprehensive description of fault characteristics. For each feature view, an adaptive hyperedge construction mechanism dynamically determines relevant node associations by integrating both feature similarity and operating condition cues, which allows the model to better characterize heterogeneous relationships. Subsequently, an attention-driven fusion module aggregates the embeddings from all views into a unified representation for final classification. Through the synergy of adaptive hyperedge learning and multi-view fusion, AMH achieves enhanced robustness against noise, superior cross-condition generalization, and strong potential for deployment in practical intelligent fault diagnosis systems. The major contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We propose an adaptive hyperedge construction mechanism that learns condition-aware, high-order relations via reconstruction-driven selection and weighting, enabling the hypergraph to capture stable cross-condition structure beyond pairwise links.

- We develop a view-level attention fusion module that aggregates time-, frequency-, and time–frequency-domain embeddings into a unified representation, assigning data-driven importance to each view to improve cross-condition generalization.

- Comprehensive experiments on the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) and Ottawa bearing datasets validate the proposed framework, with results indicating that AMH delivers superior diagnostic performance, robustness, and cross-condition generalization compared with current state-of-the-art baseline.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Methods

Traditional bearing fault diagnosis techniques have long relied on signal processing analysis in the time, frequency, and time–frequency domains [16,17]. Common approaches involve extracting manual features such as time-domain statistical indices (e.g., root-mean-square, kurtosis) and frequency-domain spectral components at characteristic fault frequencies [18]. Time–frequency methods like the wavelet transform are also employed to capture localized transient features from non-stationary vibration signals [19]. While these hand-crafted feature methods can diagnose simple faults effectively, they demand considerable domain expertise and often struggle with complex scenarios involving multiple faults or varying operating conditions. Indeed, traditional vibration analysis techniques show significant limitations when applied to large-scale, multi-fault systems, where non-linear and non-stationary signal patterns are difficult to capture with fixed features [14].

In the past decade, data-driven machine learning methods have been introduced to improve upon purely signal-based diagnostics. Early approaches using algorithms like principal component analysis, support vector machines, and k-nearest neighbors achieved higher fault diagnostic performance than basic signal processing by leveraging statistical feature inputs [20,21]. Recent advances also explore zero-fault-shot learning and simulation-driven training to improve generalization under limited data [22,23]. However, these shallow learning models still face challenges with high-dimensional vibration data and complex non-linear relationships. Classical machine learning methods cannot easily model the intricate non-linear interactions between time-domain and frequency-domain features and fault labels [24]. As a result, their performance deteriorates under noisy environments or changing operating conditions, highlighting the need for more powerful feature learning techniques.

Deep learning has become a transformative approach for bearing fault diagnosis, as it enables models to automatically extract informative features from raw vibration sensor data [25]. Both CNNs and RNNs have shown strong capability in identifying fault patterns without the need for handcrafted features [26]. CNN-based architectures utilize stacked convolutional layers to learn discriminative time–frequency representations directly from waveform inputs, achieving remarkable diagnostic performance in numerous studies [27]. For instance, Janssens et al. applied CNNs to bearing fault detection, effectively capturing frequency-decomposition characteristics from acceleration signals and significantly outperforming traditional approaches [28]. Later research further improved CNN-based frameworks by introducing multi-scale convolutional kernels, residual learning mechanisms, and multi-sensor fusion strategies to better exploit vibration information [29,30]. Meanwhile, RNN models have been employed to represent the temporal evolution of vibration sequences, often combined with CNN-based feature extractors to strengthen temporal dependency modeling [31]. Overall, these deep learning methods have substantially enhanced diagnostic performance and demonstrated superior robustness compared with conventional signal processing techniques, especially under complex working conditions.

Despite their success, conventional deep neural networks have certain limitations. For example, CNNs are effective at capturing local signal features but struggle to represent long-term dependencies because of their restricted receptive fields [14]. This makes pure CNN models less effective for capturing global fault signatures over long time-series, especially in noisy or non-smooth signals [9]. To address this gap, researchers have turned to Transformer architectures, which use attention mechanisms to capture global contextual relationships in the data [32]. Transformer-based models offer powerful sequence modeling capabilities, enabling them to extract both local and long-term features from vibration signals by attending to relevant signal components across time [33]. In recent years, several works have successfully applied Transformers in bearing fault diagnosis under varying conditions [34]. For example, Transformer networks have been designed to handle variable operating speeds, showing improved robustness compared to CNNs [35]. Hybrid models combining CNNs and Transformers have also been proposed to leverage the strengths of both local feature extraction and global sequence modeling [32]. Nonetheless, Transformer models typically require large labeled datasets and are computationally intensive, especially when two-dimensional time–frequency transforms (e.g., spectrograms) are used as input [36]. This has motivated ongoing research into more efficient, end-to-end Transformer frameworks that can learn directly from one-dimensional signals without incurring excessive complexity.

2.2. Graph-Based Methods

In parallel with the above developments, graph-based learning methods have recently gained traction in bearing fault diagnosis as a means to exploit dependencies that traditional approaches might overlook. A key insight is that standard deep learning models often assume each input sample or sensor channel is independent, thus failing to account for the correlations or interactions among multiple signals [6]. In a complex rotating machine, different sensor readings (or different segments of a signal) can have inherent relationships—for example, vibrations measured at adjacent locations or across axes are not independent. Conventional models (including CNNs and RNNs) do not explicitly capture such inter-signal connectivity, which can limit their ability to detect incipient or subtle faults that manifest as cross-signal patterns [37]. Graph-based methods address this limitation by representing the bearing monitoring data in the form of a graph, where nodes might correspond to signal segments or sensor channels and edges encode similarities or physical relationships. By doing so, GNNs can be applied to learn fault patterns while preserving the relational structure between signals.

Recent works have highlighted the effectiveness of GNNs in intelligent fault diagnosis. For instance, Xiao et al. [38] developed a GNN-based approach that models sample relationships through feature similarity graphs. In this approach, each vibration sample is a node, and edges connect samples with high similarity (e.g., in feature space or time–frequency characteristics). A GNN is then used to perform feature propagation over the graph, so that each sample’s node embedding is enriched by information from its neighbors. This graph-based feature fusion was shown to help identify faint fault patterns that individual samples may not reveal alone. In fact, the Graph Neural Network-Based Bearing Fault Detection (GNNBFD) method achieved about a 6.4% AUC improvement over the next best algorithm in experiments, validating that incorporating inter-sample relationships can enhance detection of weak fault signatures. The motivation behind such gains is clear: most traditional methods ignore correlations between signals, whereas the GNNBFD explicitly leverages those correlations to better distinguish normal versus faulty conditions [39,40].

Another notable graph-based strategy is the Granger Causality Test GNN (GCT-GNN) introduced by Zhang and Wu [41]. This method constructs a graph by organizing multi-domain features (time-domain and frequency-domain indicators) of bearing signals into a structured matrix, and then uses Granger causality principles to define edges indicating influence between features. By inputting this feature-graph into a GNN, the model learns fault-relevant patterns that account for causal relationships among different signal features, leading to more robust fault classification. The incorporation of both time and frequency information in a graph form allows GCT-GNN to effectively capture the underlying cause–effect structure of fault symptoms, which can improve diagnostic performance, especially in complex scenarios [42].

Beyond static graph approaches, researchers have also explored spatio-temporal graph modeling for bearing diagnostics. One recent approach combines a Graph Attention Network (GAT) with an Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to capture spatial–temporal dependencies in bearing vibration data [43]. In this framework, the raw time-series sensor signals are converted into a graph (for example, by segmenting the time series and connecting similar segments), and the GAT module learns the spatial (or cross-segment) relationships while the LSTM captures the temporal evolution of each segment’s features. This GAT+LSTM hybrid was shown to outperform traditional models by effectively modeling how fault features spread across different sensor locations and over time simultaneously. Such spatial–temporal graph techniques can achieve very high precision and recall. In one study, the GAT-LSTM model attained high fault detection performance across various test conditions, generalizing well to different loads and fault types. The success of this approach underscores the benefit of graph representations: by overcoming the limitations of treating sensor signals in isolation, the model can detect complex fault signatures that manifest as patterns across multiple signals and time steps [44]. Unlike previous graph-based methods, this work introduces an AMH framework tailored for cross-condition bearing fault diagnosis. Instead of relying solely on pairwise connections as in traditional GCN or GAT models, the proposed AMH framework utilizes hypergraph structures to capture high-order dependencies among signal samples across multiple perspectives, including time, frequency, and time–frequency domains. For each view, an adaptive hyperedge construction strategy selects related nodes by jointly considering feature relevance and operating conditions, thereby capturing heterogeneous and condition-aware correlations. An attention-based multi-view fusion module then integrates the view-specific hypergraphs into unified embeddings, enhancing robustness to noise and distribution shifts. This design enables AMH to better exploit multi-sensor structure and cross-condition dependencies, yielding more discriminative representations for reliable bearing fault classification.

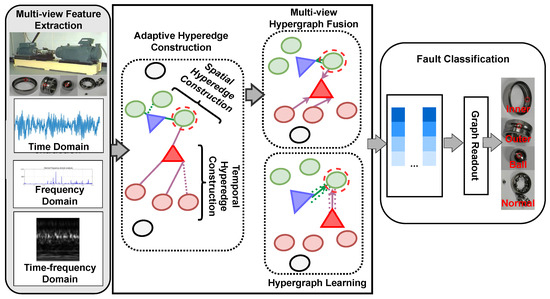

3. Methodology

In this section, we present the proposed Adaptive Multi-view Hypergraph framework for bearing cross-condition fault diagnosis. The framework is designed to capture high-order dependencies and heterogeneous correlations among multi-view signal features under varying operating conditions. Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture. Unlike prior graph or hypergraph approaches that rely on fixed neighborhood rules or heuristic hyperedge weights, we introduce an adaptive hyperedge construction scheme that learns condition-aware, high-order relations via reconstruction-driven selection and weighting. Moreover, in place of feature concatenation or equal-weight fusion across views, we design a view-level attention module that assigns data-driven importance to time-, frequency-, and time–frequency-domain embeddings, yielding a unified representation tailored to the operating condition. Together, these components provide a principled, multi-view hypergraph formulation for robust cross-condition fault classification.

3.1. Problem Definition

Let denote a set of vibration signal segments collected from bearings under multiple operating conditions, where each segment is a time-series of length T. Each segment is associated with a label , representing fault categories:

that assigns each sample to its fault category, while maintaining robustness across conditions. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on pairwise graphs, AMH introduces adaptive multi-view hypergraphs to model high-order relationships.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the proposed Adaptive Multi-view Hypergraph.

3.2. Multi-View Feature Extraction

To capture complementary information, each vibration segment is transformed into three feature views:

- Time-domain view (): statistical features such as Root Mean Square (RMS);

- Frequency-domain view (): Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) spectral energy;

- Time–frequency view (): short-time Fourier transform (STFT).

Thus, each sample is represented as:

For each view , a feature matrix is constructed as:

where is the feature dimension of view v.

3.3. Adaptive Hyperedge Construction

For each view , we construct a heterogeneous hypergraph , . Let the feature matrix be , where each is a vector. For a “master” node i, a candidate set is selected by jointly considering feature similarity and operating conditions. Denote as the submatrix of candidates and as the reconstruction coefficients. The reconstruction reads

The reconstruction-oriented objective is

Shapes: , , , , .

3.4. Multi-View Hypergraph Fusion

Let denote the node embeddings learned on (the i-th row is ). We employ a view-level attention to obtain learnable weights

and the fused embedding is

Shapes: (e.g., global readout or statistics), ; . It is worth noting that the view-level attention mechanism introduced in Equations (6) and (7) is primarily designed to achieve adaptive multi-view fusion rather than interpretability. Each attention coefficient quantifies the relative contribution of a specific view (time-, frequency-, or time–frequency-domain) based on its discriminative capacity under the current operating condition. By dynamically adjusting these weights during training, the proposed fusion strategy automatically balances heterogeneous information sources and enhances cross-condition robustness, thereby providing a unified and learnable framework for condition-aware feature integration.

To provide a more intuitive understanding, the adaptive hyperedge weight in Equation (7) is designed to capture high-order, condition-aware feature affinity. The reconstruction-driven coefficients measure feature similarity under varying operating conditions and are normalized to represent the hyperedge strengths, so that nodes exhibiting coherent vibration patterns within similar conditions receive higher connection weights. In this way, the learned topology adaptively emphasizes informative fault relations while suppressing spurious associations.

3.5. Hypergraph Learning with Attention

Let be the incidence matrix. For any hyperedge with node set , its embedding is

where is the (row-wise) node embedding from . Using multi-head attention, node updates are computed as

where the node–hyperedge attention coefficient for head h is

Shapes: , ; (scalar); . The concatenation yields a vector in , which is mapped to by Multilayer Perceptron ().

3.6. Loss Function

The overall loss combines a classification term and reconstruction regularization:

The classification loss is the cross-entropy

Shapes: (one-hot labels), with row-wise sums equal to 1; (scalar); .

4. Experiments

- RQ1: How effectively does the proposed AMH framework perform in comparison with baseline approaches regarding diagnostic performance, model robustness, and generalization across different operating conditions?

- RQ2: How well can various models differentiate among distinct fault types, and what typical patterns of misclassifications can be observed?

- RQ3: What is the specific impact of each major component of AMH, including adaptive hyperedge construction, multi-view feature integration, and attention-guided hypergraph learning, on the overall diagnostic performance?

4.1. Benchmarks

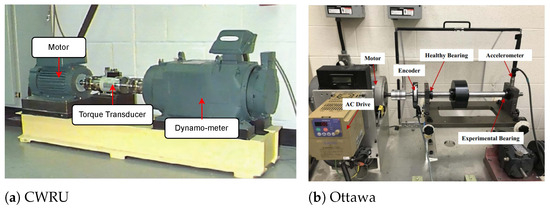

To address the research questions, we employed different datasets for distinct evaluation purposes. Specifically, the experiments for RQ1 and RQ2 were conducted on the CWRU bearing dataset [5], which is widely used for validating fault diagnosis performance under controlled laboratory conditions. The experiments for RQ3 were performed on the Ottawa bearing dataset [45] to further evaluate the model’s generalization capability under cross-condition scenarios.

4.1.1. CWRU Bearing Dataset

We adopt the CWRU bearing dataset in its standard configuration, described by operating speeds, fault types, and fault diameters rather than by a fixed number of bearings. Specifically, we use the drive-end accelerometer channel sampled at 12 kHz, under four motor speeds. Localized defects are introduced at three fault locations—inner race (IRF), outer race (ORF), and rolling element/ball (BLF)—with defect diameters of 0.007, 0.014, and 0.021 in, together with a healthy (NOR) condition. In this study, the varying operating conditions are defined by both motor speed and load levels (0–3 HP), which jointly determine the domain differences for cross-condition evaluation. Following [14], we adopt a leave-one-condition-out cross-condition protocol: in each run, one condition is held out as the target (test-only) domain while the remaining conditions form the source domain for training, with all preprocessing statistics fitted on source-training only and then applied to source-validation and target-test.

4.1.2. Ottawa Bearing Dataset

The Ottawa dataset provides vibration signal recordings sampled at 20 kHz under dynamically changing operating conditions. It consists of four categories of variable speed profiles: decreasing speed (DS), increasing speed (IS), a pattern with decreasing followed by increasing speed (DIS), and another with increasing followed by decreasing speed (IDS). Each profile includes three distinct dynamic speed modes, resulting in a comprehensive and diverse experimental setting to evaluate the diagnostic robustness of the model under varying operating conditions. The collected data cover three bearing health states—NOR, IRF, and ORF—obtained from ER16K bearings operating under multiple speed transitions. The experimental configuration of the Ottawa test platform is shown in Figure 2b, while Table 1 summaries the detailed operating parameters for both benchmark datasets.

Figure 2.

Experimental setups of the two benchmark datasets: (a) CWRU bearing test rig [5]; (b) Ottawa bearing test platform [45].

Table 1.

Description of the working conditions and operating parameters.

4.2. Model Configuration

The experimental implementation was executed on a dedicated workstation comprising an i7-12900K processor, 64 GB of DDR4 memory, and a GeForce RTX 4070 with 12 GB of memory. To guarantee runtime stability and compatibility, the software setup included Python 3.10, and PyTorch 2.1.2. Additionally, PyTorch was configured to operate in deterministic mode, ensuring that every training and evaluation procedure was repeated under identical computational settings.

4.3. Baseline Models

The effectiveness of the proposed AMH framework is evaluated by conducting comparative experiments with five well-established baseline methods. These reference models, which include both sequential deep learning networks and graph-based learning approaches, are chosen to provide a broad assessment across different architectural paradigms.

- (1) CNN [28]: A convolutional neural network that learns localized temporal and spectral representations directly from raw vibration inputs.

- (2) LSTM [46]: A recurrent network based on Long Short-Term Memory units, designed to capture long-range temporal correlations and dynamic behaviors in sequential vibration data.

- (3) GRU [47]: A Gated Recurrent Unit model that simplifies the gating mechanism of LSTM while maintaining the ability to capture temporal dependencies with reduced computational complexity.

- (4) GCN [48]: A Graph Convolutional Network that learns spatial relationships among nodes based on pairwise graph structures, effectively capturing inter-sample or inter-sensor correlations.

- (5) HGCN [49]: A Hypergraph Convolutional Network that extends GCNs by introducing hyperedges to represent high-order relationships among multiple nodes simultaneously.

The baseline models were selected to represent the commonly used methods in recent fault diagnosis research [3,49,50]. Most existing studies focus on modeling the temporal and spatial characteristics of vibration signals through convolutional, sequential, or graph-based networks. Our method follows this direction and further introduces an adaptive multi-view hypergraph framework to learn the relationships among different feature views, aiming to enhance cross-condition robustness and generalization. Hence, the comparison with these representative baselines provides a fair and effective evaluation of the proposed AMH model. All baseline models follow the preprocessing procedures, architectural setups, and training configurations reported in their original papers. The learning rate is selected from the range 0.1 to 0.0001 based on the optimal validation outcome. Hyperparameters is selected via a bounded grid search on the source validation split under the cross-condition protocol. No target data is used for tuning. We used an 80/10/10 train/validation/test split with early stopping on validation loss. The searched ranges are: learning rate , , , , , embedding dimension , heads , and dropout . For the proposed AMH framework, the hyperparameters within the adaptive hyperedge reconstruction module are empirically configured as: the reconstruction weight is set to 0.02, the regularization parameter is assigned a value of 0.3 to balance sparsity and smoothness, and the global trade-off coefficient in the overall loss function is fixed at 0.1. All experiments are conducted five independent times under different random seeds, and the average values of these runs are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of evaluation metrics across different bearing fault types for all methods.

4.4. Computational Cost

To estimate the computational cost of the proposed AMH framework, we analyze the main operations involved in each stage. (1) During adaptive hyperedge construction, each node is reconstructed from its candidate set, leading to a complexity of , where N is the number of nodes, d is the feature dimension, and represents the number of feature views. (2) In the subsequent hypergraph learning process, the update of node–hyperedge relationships through the incidence matrix H has a complexity of , with M being proportional to . (3) The attention-based node embedding refinement adds an additional cost of . Hence, the overall complexity can be approximated by , which is comparable to that of existing hypergraph models [14,51]. In practice, AMH was implemented in PyTorch and trained on a single RTX 4070 GPU, requiring approximately 0.8 s per epoch on the CWRU dataset. This demonstrates that the model achieves an effective trade-off between computational efficiency and diagnostic performance.

4.5. Metrics for Evaluation

To comprehensively assess the diagnostic capability of the proposed AMH framework, three widely recognized evaluation metrics in fault diagnosis—namely Precision, Recall, and F1-score—are employed. These indicators collectively demonstrate the model’s capacity to accurately identify fault categories, reduce incorrect predictions, and sustain consistent performance across different operating conditions. Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted fault cases among all fault predictions, reflecting the reliability of the diagnostic process and the model’s ability to avoid false alarms. Recall indicates the percentage of actual fault samples that are correctly detected, describing the sensitivity of the framework and its effectiveness in preventing missed detections. F1-score is calculated as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing an overall assessment that captures the balance between excessive and insufficient fault identification. This metric is particularly suitable for evaluating diagnostic models in the presence of uneven data distribution or varying operational scenarios.

Formally, given true positives (), false positives (), and false negatives (), these metrics are defined as:

These three metrics have been widely employed in recent bearing fault diagnosis literature as comprehensive indicators of a model’s diagnostic performance and robustness under varying operating conditions.

4.6. Main Results

4.6.1. Performance Comparison (RQ1)

Table 2 summarizes the precision, recall, and F1-scores obtained under the leave-one-condition-out cross-condition protocol, in which each operating condition is alternately treated as the target domain while the remaining conditions serve as the source domain for training. The results demonstrate clear performance disparities among the baseline models and the proposed AMH framework. Sequence-based models (CNN, LSTM, and GRU) exhibit inconsistent diagnostic capability across operating conditions, suggesting their limited ability to generalize under varying environments. In contrast, graph-based methods (GCN and HGCN) produce more stable and balanced results by leveraging inter-sample relationships, with HGCN achieving near-perfect accuracy across most target domains. The proposed AMH framework consistently achieves the highest precision, recall, and F1-scores across all evaluated conditions, attaining perfect recognition in two target domains and nearly perfect scores in the others. Compared with HGCN, AMH yields noticeable improvements in both precision and recall across several conditions, confirming that adaptive hyperedge construction and multi-view fusion enhance cross-domain robustness and generalization.

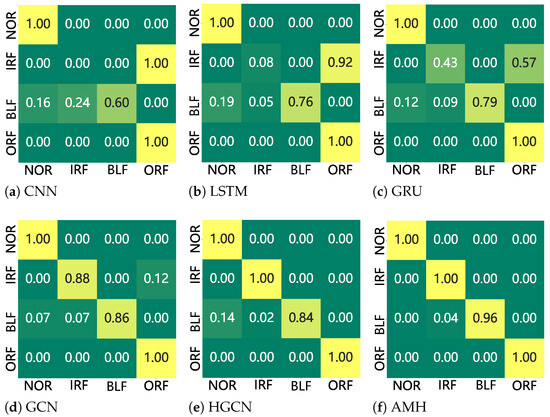

4.6.2. Confusion Pattern Analysis (RQ2)

The confusion matrices of all models provide further insight into their classification behaviors and misclassifications tendencies. As shown in Figure 3a, CNN exhibits substantial confusion between inner race faults and the ball category. Many IRF and BLF samples are incorrectly classified as ORF, whereas NOR and ORF classes are recognized reliably. This outcome indicates that CNN primarily captures prominent global patterns but fails to separate fine-grained inner race fault variations, leading to high false negatives in these categories. As illustrated in Figure 3b, LSTM alleviates this issue by incorporating temporal dependencies, but it still misclassified a portion of IRF instances as ORF and confuses BLF with both NOR and ORF, reflecting a limited capacity to distinguish subtle variations in fault severity. The GRU model (Figure 3c) improves recall for BLF compared with LSTM; however, similar confusion persists, with IRF samples frequently misidentified as ORF, demonstrating that gating mechanisms alone are insufficient to achieve robust separation. Graph-based methods significantly reduce these ambiguities by leveraging structural information. GCN (Figure 3d) achieves more balanced recognition across classes, though IRF still exhibits partial confusion with ORF. HGCN (Figure 3e) further enhances class separation, with IRF recognized almost perfectly and only minor misclassifications occurring in BLF, underscoring the advantage of modeling high-order dependencies among samples. The proposed AMH framework (Figure 3f) demonstrates the strongest discriminative capability, achieving nearly perfect separation across all fault categories. NOR and ORF are recognized with complete performance, IRF achieves flawless classification, and BLF is almost entirely separated from the other categories with only negligible confusion. These results confirm that adaptive hyperedge construction and multi-view feature integration effectively exploits complementary fault characteristics and minimize overlap among closely related fault types. Overall, confusion pattern analysis reveals that while conventional models struggle with inner race fault differentiation, AMH establishes clear decision boundaries, thereby reducing misclassifications and achieving superior fault separability.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrices of all investigated baselines.

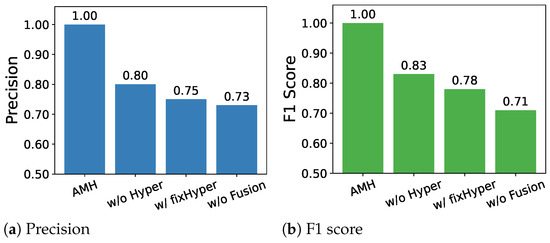

4.6.3. Ablation Study (RQ3)

To gain deeper insight into the contribution of each module within the AMH framework, an ablation analysis is performed, which also introduces a variant employing fixed hyperedges to evaluate the impact of the adaptive design. The comparative outcomes, illustrated in Figure 4, report performance for four model variants. The full AMH configuration achieves the best results, with precision and F1-score values approaching 1.00, indicating its superior capability in distinguishing various fault categories. When the adaptive hyperedge construction is removed (w/o Hyper), the performance declines noticeably (precision = 0.80, F1-score = 0.83), emphasizing the importance of modeling high-order correlations beyond pairwise connections. When replacing the adaptive module with fixed hyperedges (w/fixHyper), the performance further decreases (precision = 0.75, F1-score = 0.78), confirming that adaptivity is critical for learning condition-aware and data-driven relationships. The largest performance drop is observed when the multi-view fusion module is excluded (w/o Fusion), where precision decreases to 0.73 and F1-score to 0.71, indicating that combining complementary time, frequency, and time–frequency information is essential for robust and accurate fault classification under varying operating conditions.

Figure 4.

Ablation of AMH components under the cross-condition setting.

5. Conclusions

This study presented an Adaptive Multi-view Hypergraph (AMH) framework designed to address the challenges of cross-condition bearing fault diagnosis. In contrast to existing CNN-, RNN-, and graph-based methods that primarily model pairwise dependencies, the proposed AMH framework employs an adaptive hyperedge construction mechanism to learn high-order, condition-aware relationships, and a multi-view fusion scheme to combine complementary temporal, spectral, and time–frequency representations. Extensive experiments conducted on two widely used benchmark datasets, namely the CWRU and Ottawa bearing datasets, demonstrated that AMH achieves superior diagnostic performance, robustness, and cross-condition adaptability compared with state-of-the-art techniques. The confusion analysis further verified that AMH significantly alleviates the misclassification of similar fault categories, while the ablation results emphasize the critical contributions of adaptive hyperedge modeling and multi-view integration. Overall, AMH provides an efficient and interpretable framework for intelligent fault diagnosis and condition monitoring. Future research will focus on extending this approach to remaining useful life estimation, multi-sensor data integration, and large-scale industrial implementations to further enhance its generalization and practical applicability.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Writing—original draft, conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation. K.H.B.: Writing—review & editing, methodology, validation. R.C.: Writing—review & editing, investigation, supervision. K.M.T.: Writing—review & editing, validation, investigation. B.X.C.: Writing—review & editing, conceptualization, visualization, investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The CWRU dataset can be accessed at https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter accessed on 26 September 2025, reference number [5], and the Ottawa database is available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/y2px5tg92h/5 accessed on 26 September 2025, reference number [45].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruan, D.; Wang, J.; Yan, J.; Gühmann, C. CNN parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 55, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.; Eisenbart, B.; Nikzad, M.; Fox, B.; Blythe, A.; Bwar, K.H.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Shevtsov, S. Application of KNN and ANN Metamodeling for RTM filling process prediction. Materials 2023, 16, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Yi, W.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chai, B.X. STHFD: Spatial–Temporal Hypergraph-Based Model for Aero-Engine Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Aerospace 2025, 12, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X. A novel fault diagnosis method based on CNN and LSTM and its application in fault diagnosis for complex systems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 1289–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, T.; Chai, B.X.; Di Pietro, A.; Georgakopoulos, D. Leveraging auxiliary task relevance for enhanced bearing fault diagnosis through curriculum meta-learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 22467–22478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Deng, C. An improved GNN using dynamic graph embedding mechanism: A novel end-to-end framework for rolling bearing fault diagnosis under variable working conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 200, 110534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Deng, K. The footprint of factorization models and their applications in collaborative filtering. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2021, 40, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Shi, P. Improved GNN based on Graph-Transformer: A new framework for rolling mill bearing fault diagnosis. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2024, 46, 2804–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, J. HyperMAN: Hypergraph-enhanced Meta-learning Adaptive Network for Next POI Recommendation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22049. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Bwar, K.; Eisenbart, B.; Lu, G.; Belaadi, A.; Fox, B.; Chai, B. Application of machine learning for composite moulding process modelling. Compos. Commun. 2024, 48, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.X.; Gunaratne, M.; Ravandi, M.; Wang, J.; Dharmawickrema, T.; Di Pietro, A.; Jin, J.; Georgakopoulos, D. Smart industrial internet of things framework for composites manufacturing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tong, H.; Xu, J.; Maciejewski, R. Graph convolutional networks: A comprehensive review. Comput. Soc. Netw. 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Shi, H.; Tan, S.; Song, B.; Tao, Y. A knowledge-driven spatial-temporal graph neural network for quality-related fault detection. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 1512–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, L.; Dai, H.N.; Di-Pietro, A.; Zhang, T. Towards spatial-temporal meta-hypergraph learning for multimodal few-shot fault diagnosis. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 48, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, K.; Liu, J. SuperGraph: Spatial-temporal graph-based feature extraction for rotating machinery diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 4167–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xie, F.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Huang, B. Spatial-temporal graph feature learning driven by time–frequency similarity assessment for robust fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shao, D.; Cui, L. CTNet: A data-driven time-frequency technique for wind turbines fault diagnosis under time-varying speeds. ISA Trans. 2024, 154, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, S. Maximum L-Kurtosis deconvolution and frequency-domain filtering algorithm for bearing fault diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 223, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tian, J.; Liang, P.; Xu, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Single and simultaneous fault diagnosis of gearbox via wavelet transform and improved deep residual network under imbalanced data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleshtori, A.E.; Aghaie, A. A novel bearing fault diagnosis approach using the Gaussian mixture model and the weighted principal component analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Anand, R. Bearing fault diagnosis using multiple feature selection algorithms with SVM. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2024, 13, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matania, O.; Cohen, R.; Bechhoefer, E.; Bortman, J. Zero-fault-shot learning for bearing spall type classification by hybrid approach. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobie, C.; Freitas, C.; Nicolai, M. Simulation-driven machine learning: Bearing fault classification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 99, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, H. A novel adaptive generalized domain data fusion-driven kernel sparse representation classification method for intelligent bearing fault diagnosis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 247, 123225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, M.S.R.M.; Isham, M.F.; Talib, M.H.A.; Zain, M.Z.M. Extremely low-speed bearing fault diagnosis based on raw signal fusion and DE-1D-CNN network. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 5935–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhong, M.; Liu, X. An optimized CNN-BiLSTM network for bearing fault diagnosis under multiple working conditions with limited training samples. Neurocomputing 2024, 574, 127284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shi, C.; Sheng, H.; Li, X.; Yang, T. Lightweight CNN architecture design for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 126142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, O.; Slavkovikj, V.; Vervisch, B.; Stockman, K.; Loccufier, M.; Verstockt, S.; Van de Walle, R.; Van Hoecke, S. Convolutional neural network based fault detection for rotating machinery. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 377, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, D. Bearing fault diagnosis base on multi-scale CNN and LSTM model. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Chen, D.; He, D.; Sun, Y.; Yin, X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on VMD and improved CNN. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; Chai, Y.; Huang, X. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis method base on periodic sparse attention and LSTM. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 12044–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Lai, P.; Li, T.; Teng, F.; Jin, Z. Mt-ConvFormer: A multi-task bearing fault diagnosis method using a combination of CNN and transformer. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 74, 3501816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaeibonehkhater, M.; Labbaf-Khaniki, M.A.; Manthouri, M. Transformer-based bearing fault detection using temporal decomposition attention mechanism. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.11245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Q. Gaussian mixture variational-based transformer domain adaptation fault diagnosis method and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; An, J.; Liu, H.; Xiang, J.; Zhao, B.; Dunkin, F. A lightweight transformer with strong robustness application in portable bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 9649–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Cai, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Shi, K.; Zhong, X.; Liao, Z.; Li, Q. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis method using time-frequency information integration and multi-scale TransFusion network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Tang, C.; Sun, J.; Shi, Z.; Xu, J.; Ji, X.; Yu, J. LSTM-based node-gated graph neural network for cross-condition few-shot bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 3445–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, X. A graph neural network-based bearing fault detection method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.; Andrade, E.; Rativa, D.; Maciel, A.M. Fault detection and diagnosis in industry 4.0: A review on challenges and opportunities. Sensors 2024, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Jiu, S.; Huang, H.; Yang, G.; Yu, J. Prototype-oriented hypergraph representation learning for anomaly detection in tabular data. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, L. Graph neural network-based bearing fault diagnosis using Granger causality test. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Bai, J.; Yang, J.; Lee, J.J. Crash risk prediction using sparse collision data: Granger causal inference and graph convolutional network approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 259, 125315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.T.; Prasad, R.K.; Michael, G.R.; Singh, N.H.; Kaphungkui, N. Spatial-Temporal Bearing Fault Detection Using Graph Attention Networks and LSTM. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.11923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Cao, S.; Li, P.; Xu, C. Bearing fault diagnosis under multisensor fusion based on modal analysis and graph attention network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3526510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Baddour, N. Bearing vibration data collected under time-varying rotational speed conditions. Data Brief 2018, 21, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, P.; Hou, B.; Lei, J.; Zhang, Z. Bearing fault diagnosis method based on EEMD and LSTM. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T.; Lei, N. An improved MSCNN and GRU model for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 69, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Mo, L.; Yan, R. Fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on WHVG and GCN. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3519811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, P.; Huang, X. Residual-hypergraph convolution network: A model-based and data-driven integrated approach for fault diagnosis in complex equipment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 72, 3501811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Yin, A.; He, Q.; Lu, S.; Wei, Y. A feature cross-fusion HGCN based on feature distillation denoising for fault diagnosis of helicopter tail drive system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 270, 126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Ma, X.; Qi, P.; Ding, Z.; Jin, J. Learning from heterogeneity: A dynamic learning framework for hypergraphs. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 6, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).