Abstract

Magnetic soft manganese–zinc ferrite in a concentration scale ranging from 100 to 500 phr was incorporated into acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber. The work was focused on the investigation of manganese–zinc ferrite content on electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness and mechanical properties of composites. The rubber-based products used in industrial practice should not only provide good utility and functional properties but should also exhibit good stability towards degradation factors, like oxygen and ozone. Therefore, the samples were exposed to the thermo-oxidative and ozone ageing conditions, and the influence of both factors on the composites’ properties was evaluated. The results demonstrated that the incorporation of ferrite into the rubber matrix resulted in the fabrication of composites with absorption-shielding performance. It was demonstrated that the higher the ferrite content, the lower the absorption-shielding ability. Electrical and thermal conductivity showed an increasing trend with increasing content of ferrite. On the other hand, the study of mechanical properties implied that ferrite acts as a non-reinforcing filler, leading to a decrease in tensile characteristics. Thermo-oxidative ageing tests revealed that ferrite, mainly in high amounts, could accelerate the degradation processes in composites. Though the absorption-shielding performance of composites after ageing corresponded to that of their equivalents before ageing, it can also be concluded that the higher the amount of ferrite in the rubber matrix, the lower the composites’ stability against ozone ageing.

1. Introduction

Contemporary societal developments demonstrate a pronounced trajectory toward the proliferation of advanced electrical and electronic technologies, which substantially improve human life standards. Nevertheless, the exponential increase in electronic device deployment correspondingly elevates the magnitude of electromagnetic radiation emissions from these systems, resulting in environmental accumulation. This accumulation precipitates electromagnetic radiation phenomena, wherein radiation from discrete sources creates mutual disruption, commonly referred to as electromagnetic interference (EMI). Such interference can detrimentally compromise electronic devices’ functionality, diminish operational efficiency, and potentially cause system failures [1,2,3]. Additionally, empirical evidence has established the adverse physiological impacts of EMI exposure on biological systems and human populations [4,5,6,7]. Contemporary research investigations have elucidated EMI influence across multiple health domains, encompassing reproductive health, developmental processes, and neurological function. This evidence base has generated escalating requirements for materials capable of delivering robust electromagnetic interference mitigation solutions.

For the mitigation of electromagnetic interference to be accomplished efficiently, electromagnetic wave-absorbing barriers demonstrate greater importance compared to materials designed for EMI reflection, since reflected electromagnetic radiation may continue to cause detrimental effects. Rubber matrices function as electrical insulators and consequently lack inherent shielding capabilities. The achievement of shielding effectiveness requires the incorporation of suitable filler inclusions. Conventionally, carbon-derived fillers, including carbon black, carbon fibres, carbon nanotubes, graphite, and graphene, have been integrated into rubber composite systems [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Carbon-based fillers exhibit favourable electrical conductivity, distinctive dielectric characteristics, and elevated dielectric loss tangent values, rendering them proficient in absorbing radiation at high frequencies and elevated temperatures [16]. Nevertheless, the impedance discontinuity existing between carbon-based materials and incident electromagnetic waves results in substantial reflection of radiation from the shield’s surface, particularly at lower frequency ranges [17,18,19].

On the other hand, materials characterised by elevated permeability values and substantial magnetic loss tangent properties, including specific metallic oxides and soft ferrimagnetic materials, help to reduce impedance discontinuities at the interface between the radiation and the shield. This phenomenon leads to enhanced absorption of electromagnetic energy within the shielding material [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Ferrites constitute a class of ferromagnetic compounds characterised by elevated magnetic permeability and intermediate electrical resistivity. The fundamental composition of ferrites comprises iron oxide combined with one or more additional metallic elements in stoichiometric proportions. Typically, these compounds exist as binary structures of general formula M2+Fe3+O2−, where M2+ denotes a bivalent metallic cation or a mixture of bivalent metallic species (A + B), such as manganese–zinc (MnZn). The general compositional formula of manganese–zinc ferrites is MnxZn1−xFe2O4 [27]. Their distinctive characteristics, including minimal dielectric losses, reduced eddy current formation, substantial magnetization capacity, thermal stability, cost-effectiveness, and enhanced resistance to corrosion, make them extensively employed in radiofrequency transformers, inductive components, power supply core applications, electronic circuit constituents, inductive choke elements, memory storage apparatus, and EMI suppression components [28,29,30].

Rubbers and rubber-based materials, particularly those characterised by elevated levels of unsaturation, exhibit pronounced susceptibility to ageing and degradation processes. Rubber degradation constitutes an inherent phenomenon whereby materials’ characteristics undergo modification due to environmental factors [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The kinetics of ageing throughout both manufacturing processes and operational periods are contingent upon molecular architecture, the incorporation of diverse additives including stabilising agents, fillers, or residual polymerization catalysts, and the environmental conditions. Primary environmental parameters influencing rubber stability encompass oxygen exposure, thermal stress, ozone presence, and various forms of irradiation. Thermal conditions and oxygen availability have been established to be the predominant degradation factors, culminating in thermo-oxidative ageing. Within industrial applications, thermo-oxidative ageing represents a critical challenge, as it causes detrimental alterations in the aesthetic properties, chemical and mechanical characteristics of rubber systems.

Another factor contributing to the degradation of rubber is ozone, which reacts with the double bonds of unsaturated rubbers more quickly than oxygen. However, its molecule is larger than the oxygen molecule, so it cannot diffuse throughout the entire mass of the product; therefore, it reacts only with the double bonds in a thin surface layer (a few nm). It can penetrate deeper only through cracks that form on the surface due to the degradation effects. An accompanying feature of ozonization is the formation of hydroperoxides, which participate in oxidation reactions just like the hydroperoxides formed during reactions between rubber chains and oxygen. The products of ozonization include oxygen-containing functional groups bound to rubber macromolecules, as well as various low-molecular oxygen-based compounds [38,39,40,41,42].

As outlined, ferrites are complex metallic oxide compounds, and thus their incorporation into rubber compounds results in the introduction of substantial quantities of oxygen and iron ions. Transition metal ions, specifically iron, manganese, or copper ions, are classified as “rubber toxicants” due to their detrimental effects on rubbers’ performance. The adverse influence of these metallic species on rubbers is attributed to their catalytic activity in promoting the decomposition of hydroperoxide intermediates, which are generated within the rubber matrix through oxidative reactions between the rubber chains and atmospheric oxygen or ozone [43,44,45]. Furthermore, ferrite particles, functioning as metallic fillers, contribute to enhanced thermal conductivity within the composites, thereby facilitating increased heat transfer throughout the material system. These combined factors collectively contribute to an elevated propensity to degradation factors in rubber-based composites, such as thermo-oxidative or ozone ageing processes.

Extensive research has examined the addition of various magnetic and carbon-based fillers to polymer matrices to develop composites with EMI shielding functionality. These studies consistently demonstrate that polymer composites can achieve effective shielding performance. However, most investigations have focused on higher-frequency regions, especially the X-band (8.2–12.4 GHz) and above. In contrast, everyday electronic devices—including mobile phones, radios, televisions, and microwave appliances—emit electromagnetic radiation primarily within lower-frequency ranges (approximately 0.5–3–4 GHz). Consequently, assessing the shielding effectiveness of composites within these lower-frequency bands is equally important. The work aimed to investigate manganese–zinc ferrite loading on EMI absorption-shielding performance of composites within the low-frequency region ranging from 10 MHz to 3 GHz, covering the operational frequencies of generally used electronics, and mechanical properties of composites. Then, the materials were exposed to the conditions of thermo-oxidative and ozone ageing, and the influence of these factors on the composites’ properties was investigated. There is no known literature available describing the influence of thermo-oxidative ageing on the EMI shielding efficiency of rubber composites.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Commercially available manganese–zinc ferrite (MnZn) was supplied by Epcos Company, Šumperk, Czech Republic. It was incorporated into rubber compounds at a concentration scale ranging from 100 to 500 phr. Phr stands for parts per hundred parts of rubber. Acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber (SKN 3345, containing 31–35% acrylonitrile content) served as the matrix for composite fabrication and was procured from Sibur International, located in Russia. A sulphur vulcanization system, which included stearic acid and zinc oxide as activators, N-cyclohexyl-2-benzothiazole sulfenamide as an accelerator, and sulphur as a curing agent, was employed for the cross-linking of the composites. The chemical components comprising the vulcanization system were obtained from Vegum a.s., situated in Dolné Vestenice, Slovak.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Characterisation of the Filler

Particle size distribution analysis was conducted using the Bettersizer ST instrument (Bettersize Instruments Ltd., Dandong, China). The analytical methodology employs the Fraunhofer approximation and Mie theory through laser diffraction techniques to determine particle dimensions. The measurement principle is based on laser-beam diffraction phenomena. The optical configuration comprises a light source consisting of thermally regulated laser diodes operating at 830 nm wavelength and a detection system utilising silicon photodiode arrays. Experimental measurements were performed within a laser beam attenuation range of 5 to 28 percent over a measurement duration of 20 s.

The surface morphology and elemental analysis of ferrite were examined using a JEOL JSM-7500F (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) under varying acceleration voltages. EDS is a proficient methodology that facilitates the rapid execution of both qualitative and quantitative analyses regarding the elemental constituents present in specimen materials. Due to the magnetic characteristics of the filler, the powder was embedded in polymeric resin prior to the investigation of particle morphology, dimensions, and surface structure. The acceleration voltage ranged from 0.1 kV to 30 kV, achieving a resolution of 1.0 nm at 15 kV and 1.4 nm at 1 kV, respectively.

2.2.2. Fabrication and Curing of Composites

The composites were prepared utilising a Brabender laboratory internal mixer (Brabender GmbH & Co. KG, Duisburg, Germany) through a two-stage mixing procedure. The rotor speed was maintained at 55 rpm while the mixing chamber was heated to 90 °C. The total mixing duration for the rubber compounds was 13 min. First, the rubber was put into the chamber and plasticated for 2.5 min, followed by the incorporation of activating agents (zinc oxide and stearic acid). After an additional 2 min interval, the magnetic filler was introduced into the compound. The first-stage mixing process required a total duration of 9 min under conditions of 90 °C and 55 rpm. After that, the compounds were additionally homogenised and sheeted on a two-roll mill. In the second stage (4 min, 90 °C, 55 rpm), accelerator and sulphur were added. Finally, the compounds were homogenised on the two-roll mill after being discharged from the mixer.

The curing procedure was conducted using a hydraulic press from Fontijne (Fontijne Presses, Turbineweg, The Netherlands), adhering to the optimum curing time for each rubber compound. The curing temperature was set at 160 °C, and the pressure applied was 15 MPa. Upon completion of the curing process, thin sheets measuring 15 × 15 cm with a thickness of 2 mm were obtained.

2.2.3. Cross-Link Density

The determination of cross-link density ν relies on the equilibrium swelling of composites in an appropriate solvent. Samples were immersed in xylene until equilibrium swelling was achieved. The experiments were conducted at a room temperature, with a swelling time equaling 30 h. The Krause modified Flory-Rehner equation [46] for filled rubber compounds was utilised to calculate the cross-link density based on the equilibrium swelling degree previously obtained.

2.2.4. Mechanical Properties

The tensile tests were conducted in accordance with technical standards ISO 37:2024, utilising a universal testing apparatus, Zwick Roell/Z 2.5 (Zwick GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany). The cross-head speed was configured to 500 mm·min−1, with a gauge length of 25 mm. The dumbbell-shaped specimens, measuring 6.4 mm in width and 80 mm in length, were precisely cut from a 2 mm thick cured rubber plate using a specialised knife. The hardness was assessed in IRHD units using a durometer.

2.2.5. Absorption Shielding Characteristics

The frequency-dependent complex (relative) permeability µ = µ′ − jµ″ of toroidal samples was measured using a combined impedance and network analysis technique with a vector analyser (Agilent E5071C) over a frequency range from 1 MHz to 6 GHz. For the measurements, each toroidal sample was placed inside a magnetic holder (Agilent 16454A), and the complex permeability was determined based on the measured impedances (1):

where Z and Zair represent the input complex impedances of the 16454A holder with and without the toroidal sample, respectively. The variable h denotes the sample’s height, μ0 = 4π·10−7 H/m is the permeability of free space, f is the frequency, and b and c correspond to the sample’s outer and inner diameters.

μ = μ′ − jμ″ = 1 + (Z − Zair)/(jhμ0 f ln(b/c))

The frequency-dependent complex relative permittivity ε = ε′ − jε″ of disc samples was determined using a combined impedance and network analysis technique with a vector analyser (Agilent E5071C) over the frequency range from 1 MHz to 6 GHz. During the measurements, the disc sample was placed inside a dielectric holder (Agilent 16453A), and the complex permittivity was calculated from the measured admittance according to Equation (2):

where Y represents the input complex admittance of the 16453A holder containing a disc sample, h denotes the sample’s height, ε0 = 8.854·10−12 F/m is the permittivity of free space, and S is the area of the lower electrode. For electrically conductive materials with a dc electrical conductivity σdc, the imaginary component of ε should be replaced by ε″ − σdc/2πε0.

ε = ε′ − jε″ = (Y·h)/(jωε0S)

High-frequency single-layer electromagnetic wave absorption properties (return loss RL, matching thickness dm, matching frequency fm, bandwidth ∆f for RL at −10 dB and RL at −20 dB, and the minimum of return loss RLmin) of composite materials were obtained by calculations of return loss (3):

where Zin = (μ/ε)1/2tanh[(jω·d/c)(μ·ε)] is the normalised value of input complex impedance of the absorber, d is the thickness of the single-layer absorber (backed by a metal sheet), and c is the velocity of light in a vacuum. The composite absorbs the maximum of the electromagnetic plane-wave energy when the normalised value of impedance Zin ≈ 1. The maximum absorption is then reached at a matching frequency f = fm, matching thickness d = dm, and minimum return loss RLmin.

RL = 20·log/(Zin − 1)/(Zin + 1)

2.2.6. Electrical Conductivity

The measurement of volume resistivity was conducted using two distinct methodologies. The first approach employed a two-electrode configuration, wherein the specimen of the test material was positioned between two parallel and coaxial electrodes, and the electrical resistance was measured using a digital ohmmeter, from which the resistivity value was subsequently calculated. The second methodology utilised a three-electrode system for comparative analysis, where the test material specimen was placed within a configuration consisting of three coaxial electrodes. In this arrangement, a precision digital DC voltage source and picoammeter were employed to measure the current flowing through the specimen at a predetermined voltage setting, with the resistivity value being calculated from the applied voltage and measured current parameters. The electrical conductivity σdc values (specific electrical conductance) were determined as the reciprocal values of resistivity (specific electrical resistance).

2.2.7. Thermal Conductivity

The thermal conductivity of materials was measured using an Isomet 2114 applied precision device (Applied Precision s.r.o., Bratislava, Slovakia). The measurement is based on the analysis of the time dependence of the temperature response to pulses of heat flow into the analysed material. The heat flow is generated by the dissipated electric power in the resistor of the probe, which is thermally conductively connected to the analysed material. The temperature of the resistor is recorded by a semiconductor sensor.

2.2.8. Microscopic Analysis

The surface morphology and microstructural characteristics of the composites were examined utilising a JEOL JSM-7500F scanning electron microscope (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Prior to analysis, specimens were subjected to cryogenic cooling in liquid nitrogen below their glass transition temperature subsequently fractured to produce fragments measuring 3 × 2 mm in surface area. The fractured surfaces underwent sputter coating with a thin gold layer before microscopic examination.

2.2.9. Thermo-Oxidative Ageing

The thermo-oxidative ageing test was conducted in accordance with ISO 188:2011 specifications. Throughout this procedure, composite materials were maintained within a thermal oxygen ageing apparatus as standardised test specimens. The ageing protocol was executed under circulated atmospheric conditions at temperatures of 70 °C and 100 °C, with specimens subjected to 168 h of exposure utilising a forced convection heating chamber (BINDER FD115, BINDER GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany). Following the ageing process, specimens underwent conditioning at an ambient laboratory temperature for a minimum duration of 24 h prior to conducting cross-link density measurement and properties evaluation.

2.2.10. Ozone Ageing

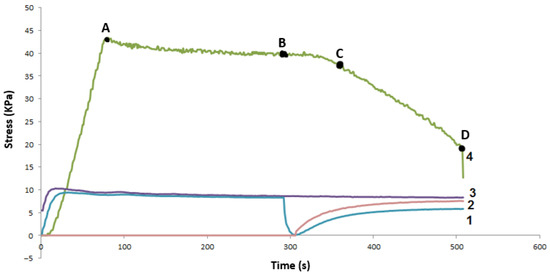

To evaluate the influence of ozone on composites, the TOM method (technical ozone resistance of material), based on mounting the flat sample along the ring contour in the joining sealing device, was used. The test procedure is illustrated in Figure 1. The sample is stressed by air into “start stress” (40 KPa, curve 4, point A), and “stress in the sample” was assessed. The sample is relaxed to a constant pressure (curve 4, point B), and subsequently ozone is supplied in the test chamber (curve 1, ozone output, curve 4, point B) with a concentration of 17 mg/L and an ozone-air flow rate of 9 L/h. “Time of cracking start” is an assessment of the time it takes to lose 5% of the samples’ strength from the ozone starting time (curve 4, points B–C), and it indicates the initiation of crack formation on the samples’ surface. “Time of cracking” is estimated from the time to lose 5% strength to the time to destroy the samples (curve 4, points C–D). “Rupture time” is the sum of “Time of cracking start” and “Time of cracking.”

Figure 1.

Graphical visualisation of ozone test conditions: ozone output of chamber with sample (1), ozone output of chamber without sample (2), ozone input (3), time-stress curve of materials’ behaviour (4).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Ferrite

Manganese–zinc ferrite is a class of magnetic soft ferrites with a spinel-type structure. The evaluation of particle size distribution revealed that the size of particles ranged from 0.7 to 50 μm with parameters D10~4.7 µm and D50~16.3 µm. The parameters D10 and D50 indicate the percentage of particles that have diameters smaller than the specified value. D50 is defined as the median, meaning that 50% of the particles are smaller than approximately 16 μm.

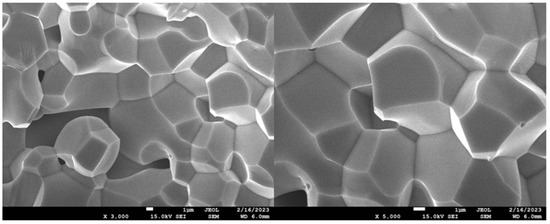

The surface morphology and the shape of particles were examined using scanning electron microscopy. Though the observation of the shape and surface was somewhat problematic, because, due to its magnetic nature, ferrite had to be embedded in a polymer resin before the analysis. However, from Figure 2, it can be concluded that the particles of manganese–zinc ferrite exhibit a hexagonal or cubic shapes of various sizes.

Figure 2.

SEM images of ferrite showing the granular microstructure.

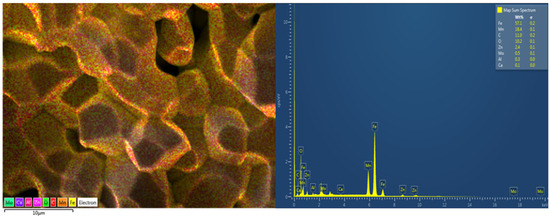

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis, an efficient and precise analytical methodology employed for elemental determination and chemical characterisation of specimens, elucidates the chemical composition of ferrite following the implementation of quantitative correction protocols, as demonstrated in Figure 3. It becomes apparent that iron is the most abundant element (57.1 wt.%), followed by magnesium (18.4%). The elemental carbon (11 wt.%) originates from polymeric resin. Oxygen was detected in the amount of 10.2 wt.%.

Figure 3.

EDS analysis of ferrite reveals its chemical elemental composition.

3.2. Influence of Ferrite and Ageing on Absorption Shielding Characteristics

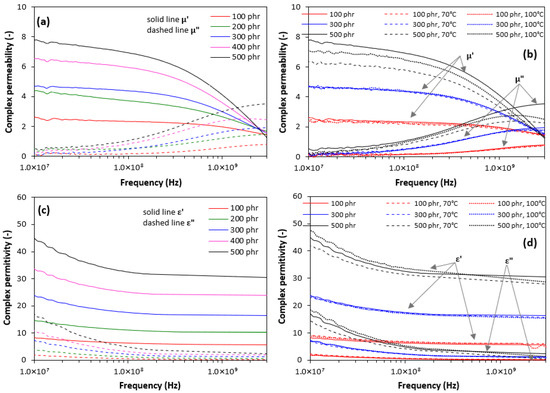

Common electronic devices utilised in daily activities, including mobiles, telecommunications equipment, computing systems, radio apparatus, television receivers, and microwave cooking appliances, generate electromagnetic emissions within lower-frequency spectra. Consequently, the mitigation of EMI in these frequency ranges has emerged as a critical concern. Previous research has established that reflection-based shielding approaches are counterproductive, since reflected electromagnetic energy continues to propagate throughout the environment, frequently resulting in adverse effects associated with secondary electromagnetic radiation phenomena. Therefore, this investigation concentrates on absorption-based shielding effectiveness, which characterises the capacity of composite materials to attenuate EMI through absorption mechanisms. The absorbed radiation undergoes conversion into benign energy forms, such as thermal energy. The absorption shielding performance of composite materials was examined across a frequency spectrum extending from 10 MHz to 3 GHz, encompassing the operational frequency range of most conventional electronic devices. Initially, the electromagnetic parameters, specifically complex permittivity and complex permeability, were assessed to gain a better understanding of the absorption shielding capabilities. Complex permeability comprises real µ′ and imaginary µ″ components (µ = µ′ − jµ″). The real permeability component signifies magnetic energy storage capability, whereas the imaginary component represents magnetic dissipation. Analogously, complex permittivity encompasses two constituents (ε = ε′ − jε″). The real component ε′ corresponds to electric charge accumulation capacity, while the imaginary component ε″ denotes dielectric dissipation or energy losses, respectively.

The frequency dependences of complex permeability for composites with various concentrations of ferrite are depicted in Figure 4a. As shown, the lowest real part µ′ exhibited the composite with the minimum ferrite content. The higher the ferrite content, the higher the real permeability. The highest µ′ was demonstrated by the composite with maximum ferrite loading. This statement is specifically valid at low frequencies. With an increase in frequency, the differences in µ′ become lower and reach similar values at higher tested frequencies. In general, the real part µ′ exhibits minimal variation with frequency up to approximately 200 MHz, after which it decreases to a value of around 1. It can also be stated that the higher the ferrite content, the higher the real permeability’s dependence on frequency. The real part of the composite with 500 phr of ferrite decreased from 7.8 at 10 MHz down to 1.25 at the maximum tested frequency. On the other hand, the lowest frequency-dependent behaviour was observed for the composite containing 100 phr of ferrite (µ′ = 2.6 at 10 MHz and µ′ = 1.44 at 3 GHz). The imaginary permeability demonstrates frequency-independent behaviour up to approximately 100 MHz, whereupon it exhibits an increase culminating in a peak at the resonance frequency (approximately 2–3 GHz). This peak in the frequency-dependent behaviour of imaginary permeability corresponds to the point of maximum magnetic dissipation or optimal permeability loss characteristics. The highest imaginary permeability was demonstrated by the composite with maximum ferrite content, while the composite containing 100 phr of ferrite was found to have the lowest µ″, demonstrating the lowest frequency dependence, too. The higher the frequency, the greater the differences in imaginary permeability among the composites.

Figure 4.

Influence of ferrite and thermo-oxidative ageing on frequency dependences of complex permeability (a,b), and complex permittivity (c,d).

The frequency dependences of the composites’ real and imaginary permeability after thermo-oxidative ageing are graphically illustrated in Figure 4b. To assess the influence of thermo-oxidative ageing on EMI shielding characteristics, composites filled with 100 phr, 300 phr, and 500 phr of ferrites were aged, and the values were compared with the original non-aged composites’ values. It becomes apparent that frequency dependences of real as well as imaginary permeability for composites loaded with 100 phr and 300 phr of ferrites after ageing were almost in perfect alignment with those of original non-aged composites. Some differences in frequency dependences of µ′ and µ″ after ageing were observed for the composite with maximum ferrite loading, though their dependences seem to be independent of ageing temperature.

Figure 4c presents a graphical representation of the frequency-dependent behaviour of both the real ε′ and imaginary ε″ components of the complex permittivity. The data reveal that the real part ε′ exhibits a decrease at frequencies extending to approximately 100 MHz, subsequently stabilising at a plateau value. This initial reduction in real permittivity may be ascribed to the semiconducting nature of manganese–zinc ferrite. Furthermore, as the ferrite content increases, the real permittivity shifts towards higher values. Specifically, when the magnetic filler loading increased from 100 to 500 phr, the real permittivity exhibited a corresponding increase from 8.4 to 44.8 at the initial frequency. As the electromagnetic radiation frequency increases, the disparities in real permittivity values become progressively less pronounced. The ε’ of the composite with minimum ferrite content decreased to 5.8, while the real part of the composite filled with 500 phr dropped to 30.6 at 3 GHz. The frequency-dependent characteristics of the imaginary permittivity display a comparable declining pattern. The real permittivity of the composite systems consistently exceeds the imaginary permittivity, with the differences between ε″ values becoming less significant at frequencies over 1 GHz.

Looking at Figure 4d it can be stated that no significant influence of thermo-oxidative ageing on the real as well as imaginary permittivity was recorded, as the frequency dependences of both characteristics for aged composites were in good correlation with those for the corresponding composites before ageing.

The obtained permittivity and permeability measurements were employed to calculate the return loss (RL), thereby providing qualitative assessments of the absorption-based EMI shielding composites’ performance. Empirical studies have demonstrated that materials exhibiting return loss values of −10 dB possess the capacity to absorb approximately 90–95% of incident electromagnetic plane waves. When shielding materials demonstrate return loss values of −20 dB, they can attenuate nearly 99% of EMI through absorption mechanisms [22,47,48,49]. The broader the frequency bandwidths across which the shielding materials sustain return loss values of −10 and −20 dB, the greater their efficacy as EMI-absorbing materials.

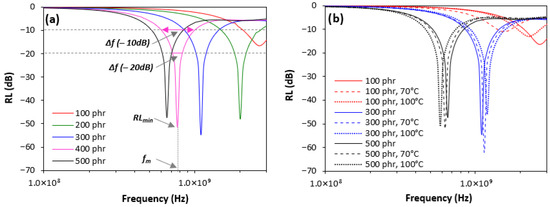

Figure 5a depicts the return loss of composites within the tested frequency range, while the examined electromagnetic absorption characteristics are presented in Table 1. RLmin (dB) denotes the lowest return loss value, indicating the highest absorption shielding performance, occurring at the matching frequency fm (MHz); Δf (MHz) is the effective frequency bandwidth for absorption shielding at RL = −10 and −20 dB. It can be stated that all composites demonstrated absorption shielding efficiency within the tested frequency range. However, as shown, the composite filled with 100 phr of ferrite did not reach return loss at −20 dB. The effective frequency bandwidth for absorption shielding at −10 dB, meaning the absorption of 95% incident EMI, ranged from 2.2 GHz up to the maximum tested frequency of 3 GHz (Δf = 900 MHz). This composite exhibited the highest matching frequency (fm = 2661 MHz) and the highest peak representing the maximum absorption shielding effectiveness (RLmin = −16.5 dB). It becomes apparent that with increasing content of ferrite, the absorption maxima and absorption shielding effectiveness shift to lower frequencies. The composite containing 200 phr of ferrite can be considered as the best absorption shield, as evidenced by the widest effective frequency bandwidths reached at −10 and −20 dB, specifically from 1.5 GHz to 2.71 GHz at −10 dB (Δf = 1210 MHz) and from 1.86 GHz to 2.2 GHz at −20 dB (Δf = 340 MHz). The absorption maximum of this composite was −48.2 dB at roughly 2 GHz. The composite containing 300 phr of ferrite exhibited a lower absorption maximum (the lowest one among all tested composites, −54.7 dB), but also lower frequency ranges for effective absorption shielding, spanning from 0.86 GHz to 1.44 GHz at –10 dB and from 1.03 GHz to 1.19 GHz at –20 dB. The maximally filled composite demonstrated the lowest matching frequency (fm = 655 MHz) and narrowest absorption peak (the effective absorption frequency bandwidths ranged within 530–850 MHz at −10 dB and within 620–700 MHz at −20 dB). Based upon the achieved results, it can be stated that the higher the ferrite content, the lower the absorption shielding performance. Simultaneously, the composites were able to absorb EMI at lower frequencies.

Figure 5.

Influence of ferrite (a) and thermo-oxidative ageing (b) on frequency dependences of return loss RL.

Table 1.

Electromagnetic absorption parameters of composites.

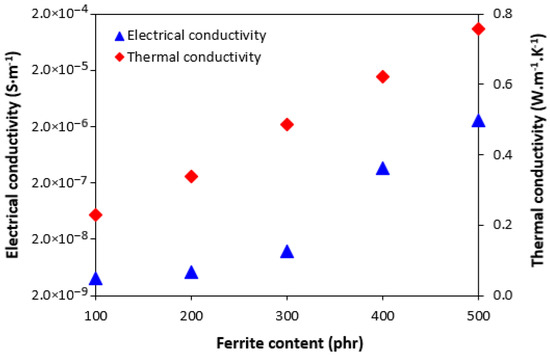

The results revealed that the absorption shielding performance of composites and the frequency for absorption shielding decreased with increasing content of ferrite. To gain closer insight into the composites’ absorption shielding effectiveness, the electrical conductivity of the composites was evaluated. It becomes apparent from Figure 6 that the higher the content of ferrite, the higher the composites’ conductivity, even though ferrites, as complex compositions of oxides, in general, are classified as dielectric materials. By increasing the ferrite content from a minimum up to a maximum content, the composites’ conductivity increased by three orders, from 4.02 × 10−9 S·m−1 up to 2.6 × 10−6 S·m−1. As shown, the differences in electrical conductivity were more pronounced at higher ferrite loadings. Higher conductivity was reflected in the higher complex permittivity of the corresponding composites. The real component of permittivity reflects a material’s ability to store electric charge, which is closely related to its polarisation [50,51,52]. Ferrite particles act as micro-capacitors that retain localised electric charges and form networks of micro-capacitors surrounded by a non-electric rubber matrix. With increasing content of ferrite, local electric fields intensify within the rubber matrix gaps as charge carriers move and accumulate at the interface between the rubber and the filler [53]. Increasing the amount of the filler reduces the spacing between ferrite particles in the rubber matrix, resulting in enhanced charge polarisation at the rubber-filler interface. Moreover, dipoles develop on semi-conductive ferrite particles, influenced by frequency [54,55]. The imaginary part of permittivity relates to dielectric losses or energy dissipation. As the content of ferrite increases, higher interfacial polarisation between the rubber and filler on their interface occurs due to the reduced distance between particles. As a result, composites with higher conductivity can dissipate more electrical energy [56].

Figure 6.

Influence of ferrite on electrical and thermal conductivity.

The real and imaginary permeability correspond to magnetic energy storage and energy loss, respectively. In general, materials with high permeability have been demonstrated to offer effective shielding performance through absorption [22,57]. The addition of manganese–zinc ferrite-containing magnetic dipoles led to an increase in the complex permeability of composites, though both permeability components were found to be frequency dependent. As the composites exhibited frequency-dependent complex permeability, the permittivity in line with electrical conductivity is an important characteristics that determine the absorption shielding performance of composites at low frequencies. The absorption shielding efficiency decreases as conductivity and permittivity increase. The obtained results further showed that the higher the conductivity, the lower the frequency for absorption shielding. Following this, the lowest absorption shielding effectiveness was manifested by the composite with maximum ferrite loading, with the highest conductivity (and permittivity). Concurrently, this composite demonstrated the lowest matching frequency. It has been reported in scientific studies that materials exhibiting increased electrical conductivity are more prone to shield EMI via reflection mechanisms, particularly within lower frequency ranges [58,59,60,61].

The effect of thermo-oxidative ageing on frequency dependences of composites’ return loss is depicted in Figure 5b, while their electromagnetic absorption parameters after ageing at 70 °C and 100 °C are given in Table 2 and Table 3. It becomes apparent that the return loss of composites after ageing increased or decreased with no clear pattern in ferrite content or ageing temperature. In addition, it is evident that magnetic composites retained the absorption shielding efficiency below −10 dB even after thermo-oxidative ageing. Composites containing 300 and 500 phr of ferrite achieved absorption shielding efficiency below −20 dB after ageing, which represents absorption of approximately 99% EMI. In the case of aged samples loaded with 100 and 500 phr ferrite, there is a shift in absorption maxima and overall absorption efficiency towards lower frequency regions, in contrast to composites with 300 phr, where the opposite trend was recorded. However, in general, it can be stated that no significant influence of thermo-oxidative ageing on absorption shielding efficiency of the tested composites was observed, and the measured deviations can be attributed to experimental measurement error.

Table 2.

Electromagnetic absorption parameters of composites after ageing at 70 °C.

Table 3.

Electromagnetic absorption parameters of composites after ageing at 100 °C.

3.3. Influence of Ferrite and Thermo-Oxidative Ageing on Cross-Link Density and Mechanical Characteristics

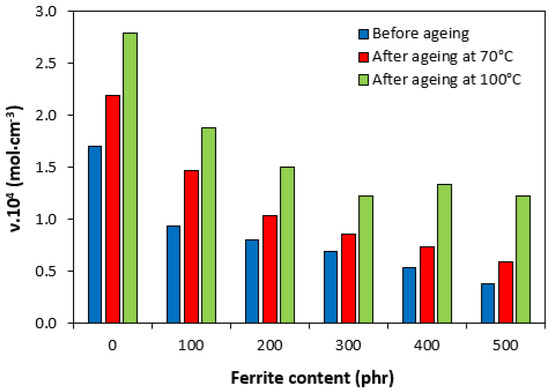

As shown in Figure 7, the highest cross-link density was exhibited by the reference sample without ferrite. The higher the content of ferrite, the lower the cross-link density. The decrease in cross-linking degree with an increase in ferrite loading can be attributed to the fact that ferrite particles can act as steric hindrances against the cross-links’ formation between the chain segments.

Figure 7.

Influence of ferrite on cross-link density υ.

Throughout the thermo-oxidative ageing process, chemical reactions induce permanent alterations in rubber molecular structures, resulting in the degradation of mechanical and functional characteristics. The oxidative process exhibits autocatalytic behaviour and operates through radical-mediated pathways. During the initiation phase, hydrogen abstraction from polymer chains takes place, generating macromolecular radical species. Subsequently, oxygen molecules readily react with these macroradicals to form peroxide radicals, which further generate polymer hydroperoxides and peroxides. Polymer hydroperoxides and peroxides undergo scission reactions, yielding polymer segments of reduced molecular weight. Throughout the ageing process, numerous isomerization, cyclization, and fragmentation reactions of rubber chains take place, too. This phenomenon leads to the generation of low molecular weight chain segments incorporating oxygen-containing functional groups, including aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, or esters [43,62]. Additionally, the degradation of chemical cross-links established between chain segments occurs during the ageing process [63]. Through the implementation of sulphur vulcanization systems, sulfidic crosslinks of varying lengths (monosulfidic, disulfidic, and polysulfidic) are formed between the chain segments. The bond dissociation energy associated with sulfidic cross-links is considerably lower relative to carbon–carbon bonds, rendering them significantly more susceptible to rupture. The ageing mechanisms governing polymer and rubber materials have been extensively documented in numerous scholarly investigations, including references [31,64,65,66,67,68,69].

During ageing, the degradation of previously generated chemical cross-links between chain segments and the breakdown of macromolecular chains occur simultaneously with potential additional cross-linking within the rubber matrix. This secondary cross-linking phenomenon results from the presence of unreacted sulphur and residual curing system components, which were not consumed during the curing process [70,71,72]. The experimental findings demonstrate that the formation of additional cross-links within the rubber matrix exceeded the degradation of existing cross-links and macromolecular chain scission, consequently resulting in enhanced cross-link density. The increase in cross-linking degree was more pronounced at 100 °C, indicating that elevated temperatures facilitate more effective reactions between previously unreacted curing system additives and rubber functional groups. It is also evident that the relationship between the cross-link density and the amount of filler remained unchanged with ageing, meaning the highest cross-linking degree was exhibited by the reference sample. In contrast, the lowest cross-link density was determined in the composite loaded with maximum ferrite content.

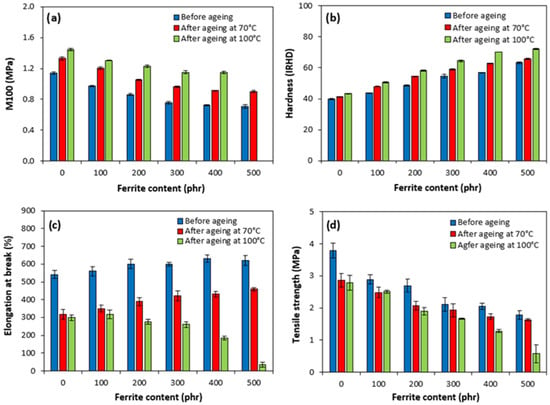

The impact of ferrite and thermo-oxidative ageing on the mechanical properties of composites is visually presented in Figure 8a–d. It becomes apparent that modulus M100 shows a decreasing trend with increasing amounts of the filler (Figure 8a). The decrease in modulus is caused by the reduction in the cross-link density of composites with increasing filler content, on the one hand. On the other hand, the modulus is also influenced by the type and content of filler and the filler’s reinforcing effect. In this respect, it is evident that the negative impact on the modulus is also due to the nature of the magnetic filler, which acts as an inactive filler from the perspective of mechanical properties. This effect was reflected in the decrease in tensile strength with increasing filler loading as well (Figure 8d). The rigid crystalline structure of ferrite causes it to function as a focal point for stress accumulation at the interface between the filler and the rubber matrix. This configuration prevents the activation of micro-crack inhibition mechanisms within the composite system. Consequently, micro-crack propagation occurs upon applied deformation strains, resulting in premature material failure [73]. This phenomenon establishes an inverse relationship between ferrite concentration and tensile performance. On the other hand, the higher the ferrite content, the higher the hardness of composites (Figure 8b). The hardness of the ferrite particles significantly exceeds that of the rubber matrix. Small filler inclusions can effectively occupy various voids and free spaces within the composites, contributing to the increase in hardness as well. The decrease in cross-link density with an increase in filler loading is reflected in the increase in composites’ elongation at break (Figure 8c). In general, the lower the cross-link density, the higher the mobility and elasticity of the chain segments, resulting in an increase in elongation at break.

Figure 8.

Influence of ferrite on modulus M100 (a), hardness (b), elongation at break (c), tensile strength (d).

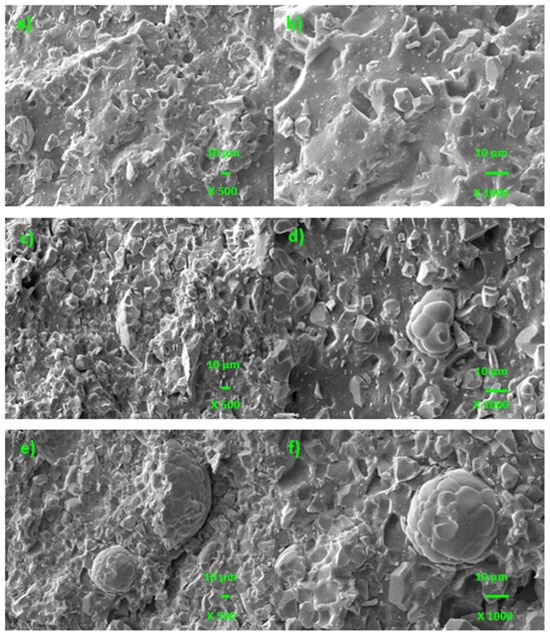

To monitor the degree of distribution and dispersion of the filler, the morphology of the composites’ fracture surfaces was examined using scanning electron microscopy. Selected SEM images of the composites containing 100 phr, 300 phr, and 500 phr of the filler are presented in Figure 9. SEM images at 500× magnification show the distribution of the filler within the matrix, and at 1000× magnification, it is possible to observe a more detailed view of ferrite particles, while individual phases of the composites can also be distinctly recognised. In addition, there are noticeable defects that likely arose from freezing the samples below the glass transition temperature and subsequently fracturing them to obtain surfaces for microscopic analysis. These defects indicate weak adhesion between the filler and the rubber on their interface. The formation of aggregates or agglomerates of filler particles can be observed from SEM images, which were found not to be homogeneously dispersed within the rubber formulations. SEM images revealed the presence of particles with various shapes and sizes, which essentially correlate with the results obtained from measuring the particle size distribution. The results of microscopic analysis confirmed the assumptions outlined during the evaluation of the mechanical properties and highlighted the weak homogeneity and compatibility between the filler and the rubber matrix.

Figure 9.

SEM images of composites filled with 100 phr of ferrite (a,b), 300 phr of ferrite (c,d), 500 phr of ferrite (e,f).

Thermo-oxidative ageing influenced the mechanical properties in different ways (Figure 8a–d). The modulus M100 (Figure 8a) and hardness (Figure 8b) increased after ageing at 70 °C. The rise in ageing temperature to 100 °C was connected with a higher increase in both characteristics. The increase in both modulus and hardness after ageing can be attributed to an increase in the stiffness of the rubber matrix due to the additional cross-linking (Figure 7) as outlined above. The character of the modulus and hardness dependence on ferrite content after ageing remained unchanged. The modulus of the maximally filled composite was not detected after ageing at 100 °C, because the test specimen was ruptured before reaching 100% elongation.

On the other hand, thermo-oxidative degradation adversely affected the elongation at break and tensile strength (Figure 8c,d). As shown in Figure 8d, after exposing the composite samples to ageing conditions at 70 °C and 100 °C, the tensile strength decreased across all filler concentration range by 8% to 37% compared to the equivalent non-aged composites. The most significant decrease was recorded for the composite with the maximum ferrite content, i.e., from 1.8 MPa before ageing to 0.6 MPa after ageing at 100 °C, which represents a 67% decrease. Based on the results obtained, it is evident that the effect of accelerated ageing was the most pronounced in the elongation at break (Figure 8c). After exposing the test specimens to thermo-oxidative ageing conditions, similarly to the tensile strength, a decrease in the property was recorded. After ageing at 70 °C, the elongation at break decreased by 26–41%, while the decrease after 100 °C presented a change of 45–94% compared to corresponding non-aged composites. The most significant decrease in the characteristics was recorded for the composite with the maximum ferrite loading. After ageing at 100 °C, the elongation of the composite with 500 phr of the filler decreased from 620% to 35%. The decrease in elongation at break during thermo-oxidative degradation can be ascribed to the additional cross-linking of the rubber matrix [74]. In general, the higher the cross-link density, the more the elasticity and mobility of the rubber chain segments are restricted, which is associated with lower material ultimate elongation. Another reason for the decrease in elongation at break may be the transformation of elastic polysulfidic cross-links into bonds with a lower number of sulfur atoms in the sulfur bridges [70,75,76]. This mainly concerns monosulfidic and disulfidic cross-links, which have lower flexibility and mobility compared to polysulfidic linkages. Interestingly, in this context, while the elongation at break increased with increasing content of the filler before ageing and after ageing at 70 °C, the composites subjected to the thermo-oxidative ageing test at 100 °C demonstrated a decrease in the property as ferrite content increased. Table 4 provides the percentage change in cross-link density and mechanical properties of composites after ageing at the tested temperatures. One can see that the most significant changes in the mechanical properties, mainly in the case of tensile strength and elongation at break, occurred in composites with high ferrite loading aged at 100 °C.

Table 4.

Percentual change in cross-link density and mechanical properties of composites after ageing.

The decrease in composites’ tensile strength and elongation at break after ageing indicates that not only does additional cross-linking of the rubber matrix take place during this process, but also that the cleavage and degradation of rubber chains, along with the previously established cross-links, occur simultaneously, resulting in irreversible alterations to the rubber structure. Furthermore, side-chain vinyl groups present in 1,2-butadiene structural units within butadiene-based elastomers demonstrate considerable susceptibility to radical addition reactions. The polymer radicals generated during thermo-oxidative ageing processes readily interact with the double bonds present in vinyl substituents, consequently promoting chain branching or even additional crosslinking within the rubber [75,77,78]. It may be concluded that the extent of branching, cyclization, and supplementary cross-linking within the rubber matrix through radical addition mechanisms and sulphur cross-linking formation exceeds that of polymer degradation processes, thereby increasing the cross-link density. Nevertheless, degradation and main-chain scission reactions occurring simultaneously with cross-linking during the ageing process compromise the uniformity, regularity, and molecular weight of rubber chains, ultimately resulting in diminished tensile properties of the composite materials. A significant deterioration in elongation at break and tensile strength of composites with high ferrite loadings (mostly 400 phr and 500 phr) suggests that, in addition to ageing conditions, the amount of manganese–zinc ferrite may also influence the thermo-oxidative degradation of rubber composites. Based on the results obtained, it can be assumed that mainly a high amount of ferrite present in the rubber matrix negatively affects the thermo-oxidative stability of composite systems. The negative impact of ferrite may be primarily related to its catalytic effect on the decomposition of hydroperoxides, which are generated in rubber formulations due to oxidation of macromolecular chains [43,45,79,80,81]. This effect can be attributed to the presence of iron and manganese ions, as well as oxygen species in the structure of ferrite, as demonstrated by SEM EDS analysis. The decomposition of hydroperoxides subsequently accelerates the scission and degradation of rubber chains. Another factor possibly contributing to the worsening of composites’ thermo-oxidative stability is their high thermal conductivity. As depicted in Figure 6, thermal conductivity demonstrated a linear increase as the ferrite content increased. The conductivity of the maximally filled composite reached 0.76 W·m−1·K−1, which was more than three times higher in comparison with that of the reference (0.23 W·m−1·K−1) and more than two times higher in comparison with the composite filled with 100 phr of ferrite (0.34 W·m−1·K−1). With higher thermal conductivity, greater heat can be accumulated within the rubber matrix and thus promotes thermo-oxidative ageing reactions.

3.4. Influence of Ferrite on Ozone Ageing

In addition to the fact that rubber products are prone to thermo-oxidative ageing as evaluated in the previous chapter, they are also sensitive to the influence of ozone. Therefore, testing of the composites’ resistance to ozone was also carried out. Ozone molecules are larger compared to oxygen molecules, and therefore ozone acts on rubber primarily in the narrow surface layers (a few nm), where it causes the formation and growth of surface cracks. Through these cracks, ozone can penetrate deeper into the bulk of the product.

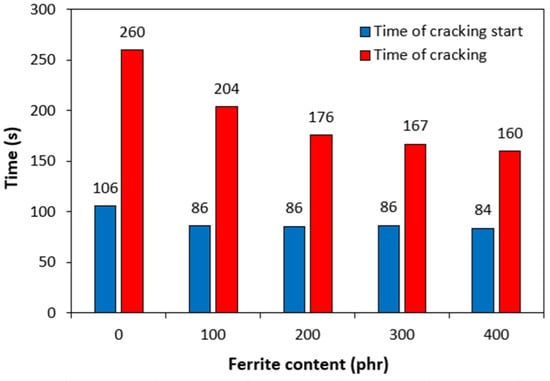

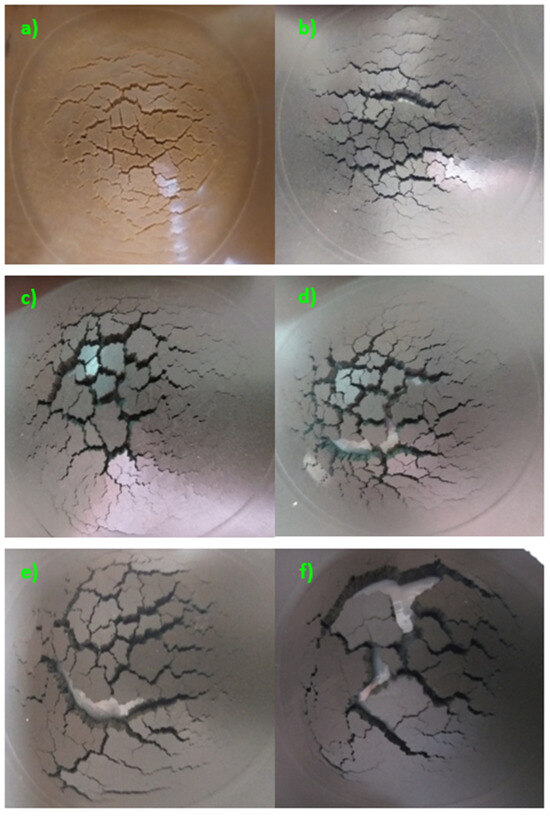

The resistance of the material to ozone implies two components. The first component indicates “Time of cracking start,” and it depends on the surface structure of the rubber (e.g., active centres, especially double bonds) and stress (applied stress was constant). Ozone reacts preferentially with double bonds and, therefore, in general, the decisive factor for the resistance to ozone is the chemical structure of rubber and the presence of double bonds. “Time of cracking start” correlates with a loss of 5% of the tested sample’s strength and indicates the formation of cracks on the composite’s surface. The second component characterises “Time of cracking,” and it is dependent on the mechanical properties of the material (structural strength, tensile strength). “Time of cracking” indicates how the composite withstands the growth of any cracks under the applied stress or deformation or indicates the time for cracks’ growth under the applied stress, respectively. From Figure 10 and Table 5, it is shown that the application of 100 phr filler leads to a decrease in the initiation time of crack formation compared to the reference sample. With the next increase in ferrite content, almost no change in the induction period for crack formation was observed. On the other hand, “Time of cracking” shortened as the filler content increased, which suggests that the resistance of composites to ozone decreases with increasing ferrite content. Similarly, rupture time showed a decreasing trend with filler content. Figure 11 provides an overview of the composites’ surfaces after ozone ageing. It becomes clearly obvious the higher the ferrite content, the bigger the cracks and the greater the surface damage, clearly pointing to the negative effect of ferrite content on composites’ stability against ozone ageing.

Figure 10.

Influence of ferrite on the formation and growth of cracks during ozone ageing.

Table 5.

Parameters of ozone test.

Figure 11.

Surface structure of composites after ozone ageing: reference sample (a), composites filled with 100 phr of ferrite (b), 200 phr of ferrite (c), 300 phr of ferrite (d), 400 phr of ferrite (e), 500 phr of ferrite (f).

4. Conclusions

The results of the study revealed that manganese–zinc ferrite grants the rubber composites the EMI absorption shielding characteristics within low-frequency spectra, which cover the operational frequency of commonly used electronics. The biggest advantage is the composites’ ability to absorb the radiation without a negative impact on the functionality of the electronics or the surrounding environment. It was shown that the absorption shielding efficiency diminished with increasing content of ferrite due to the increase in the composites’ conductivity and permittivity. Also, the higher the conductivity and permittivity, the lower the frequency for absorption shielding. The application of ferrite resulted in a decrease in cross-link density of composites, which was reflected in the decrease in modulus and increase in elongation at break. The hardness of the composite increased as the hardness of the ferrite is much higher than that of the rubber matrix. The decrease in tensile strength and modulus with increasing ferrite content points to the fact that ferrite behaves as an inactive filler in terms of mechanical properties. The additional cross-linking of the rubber matrix, scission, branching, cyclization, and restructuring of the cross-links and rubber chain segments during thermo-oxidative ageing resulted in an increase in modulus and hardness and a decrease in elongation at break. The tensile strength also decreased after ageing. The most pronounced decrease in elongation at break and tensile strength was recorded for composites with high filler loading, suggesting that the amount of manganese–zinc ferrite negatively influences the composites’ thermo-oxidative stability. The negative impact may be primarily related to its catalytic effect on the decomposition of hydroperoxides, generated in the rubber matrix during ageing processes. On the other hand, almost no influence of ageing on the composites’ absorption shielding effectiveness was recorded. The experimental outputs also demonstrated that the ferrite present in the rubber matrix accelerated ozone ageing of the tested composites. The deterioration of composites’ mechanical properties over time would reduce their service life; thus, efficient antidegradants must be added to rubber formulations. On the other hand, no negative influence of ageing on absorption shielding parameters provides a promising prospect regarding the functional EMI shielding effectiveness over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; Methodology, J.K.; Software, R.D.; Validation, L.B.; Formal analysis, L.B. and R.D.; Investigation, M.D. and R.D.; Resources, M.D. and L.B.; Data curation, M.D.; Writing—review & editing, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant agency VEGA under the contract No. 1/0056/24 and the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-22-0011.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors declare no relevant ethical issues to be approved.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Duan, Z.; Li, Y. Electromagnetic interference effect of portable electronic device with satellite communication to GPS antenna. Sensors 2025, 25, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, S.A.; Amneenah, N.S. Electromagnetic interference impacts on electronic systems and regulations. Int. J. Adv. Multidisc. Res. Stud. 2024, 4, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Deutschmann, B.; Winkler, O.V.E.G.; Kastner, P. Impact of electromagnetic interference on the functional safety of smart power devices for automotive applications. Elektrotechnik Informationstechnik 2018, 135, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.C.; Chiang, J.C.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Cheng, T.J.; Huang, C.Y.; Chuang, Y.T.; Hsu, T.; Guo, H.R. Physiological changes and symptoms associated with short-term exposure to electromagnetic fields: A randomized crossover provocation study. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, J.A.; Alsahlany, A.M. Review: Electromagnetic radiation effects on the human tissues. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 8130–8146. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.C. Health and safety practices and policies concerning human exposure to RF/microwave radiation. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1619781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokpinar, A.; Altuntaş, E.; Değermenci, M.; Yilmaz, H.; Baş, O. The Impact of electromagnetic fields on human health: A review. Middle Black Sea J. Health Sci. 2024, 10, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Xia, H. Constructing a segregated magnetic graphene network in rubber composites for integrating electromagnetic interference shielding stability and multi-sensing performance. Polymer 2021, 13, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; Ma, S.; Lin, G.; Zhang, X.; Huang, B.; Qian, Q.; Wu, C. Achieving acceptable electromagnetic interference shielding in UHMWPE/ground tire rubber composites by building a segregated network of hybrid conductive carbon black. Nanocomposites 2023, 9, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, J.; Katbab, A.A.; Mehranvari, M. Investigation of microstructure, electrical behavior, and EMI shielding effectiveness of silicone rubber/carbon black/nanographite hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 4056–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.C.; Yan, D.X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Cui, C.H.; Bianco, E.; Lou, J.; Vajtai, R.; Li, B.; Ajayan, P.M.; et al. High Strain tolerant EMI shielding using carbon nanotube network stabilized rubber composite. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2, 1700078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Fan, Y.; Shi, A. Bidirectionally oriented carbon fiber/silicone rubber composites with a high thermal conductivity and enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. Materials 2023, 16, 6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringayil Joseph, T.; Mariya, H.J.; Haponiuk, J.T.; Thomas, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Sajadi, S.M. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of natural and chlorobutyl rubber blend nanocomposite. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansala, T.; Joshi, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Doong, R.; Chaudhary, M. Electrically conducting graphene-based polyurethane nanocomposites for microwave shielding applications in the Ku band. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 1546–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarian, A.; Naderi-Samani, H.; Razavi, R.S.; Jabbari, M.N.; Naderi-Samani, E.; Jahromi, M.G. Study of nickel-coated graphite/silicone rubber composites for the application of electromagnetic interference shielding gaskets. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Y.; Gao, M.Y.; Miao, Y.; Wang, X.M. Recent progress in increasing the electromagnetic wave absorption of carbon-based materials. New Carbon Mater. 2023, 38, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, M.; Xie, A.; Xu, X. Recent advances in design and fabrication of nanocomposites for electromagnetic wave shielding and absorbing. Materials 2021, 14, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Z. Microwave absorption and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of Li-Zn ferrite-carbon nanotubes composite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 528, 167808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yin, X.; Zhu, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Wei, H.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, L. Constructing hollow graphene nano-spheres confined in porous amorphous carbon particles for achieving full X band microwave absorption. Carbon 2019, 142, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, J.; Lather, S.; Gupta, A.; Dahiya, S.; Maan, A.S.; Singh, K.; Dhawan, S.K.; Ohlan, A. EMI shielding properties of laminated graphene and PbTiO3 reinforced poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 165, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hema, S.N.; Jayakumar, O.D.; Sreedha, S. Advanced and sustainable EMI shielding composites: Natural rubber-nitrile rubber blends enhanced with hydrothermally synthesized polyaniline nanofibers and spinel strontium ferrites. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 54, 105211. [Google Scholar]

- Kruželák, J.; Kvasničáková, A.; Hložeková, K.; Hudec, I. Progress in polymers and polymer composites used as efficient materials for EMI shielding. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.N.; Wang, Y.; Yue, T.N.; Wang, M. Achieving absorption-type electromagnetic shielding performance in silver micro-tubes/barium ferrites/poly(lactic acid) composites via enhancing impedance matching and electric-magnetic synergism. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 249, 110402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.P.; Dobbidi, P. Development of spinel ferrite-based composites for efficient EMI shielding. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 301, 127581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Muniyappan, S.; Racik, K.M.; Manikandan, A.; Mani, D.; Nandhini, S.; Karuppasamy, P.; Pandian, M.S.; Ramasamy, P.; Chander, N.K. Fabrication of binary to quaternary PVDF based flexible composite films and ultrathin sandwich structured quaternary PVDF/CB/g-C3N4/BaFe11.5Al0.5O19 composite films for efficient EMI shielding performance. Synth. Met. 2022, 291, 117199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N.; Shati, K.; Rehman, U.U.; Nedeen, M. Polyaniline-encapsulated carbon-coated nickel zinc ferrite: A hybrid composite for enhanced absorption-dominant EMI shielding. Synth. Met. 2025, 312, 117883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, L.G.; Petrescu, M.C.; Ionită, V.; Cazacu, E.; Constantinescu, C.D. Magnetic properties of manganese-zinc soft ferrite ceramic for high frequency applications. Materials 2019, 12, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Chahar, D.; Taneja, S.; Bhalla, N.; Thakur, A. A review on Mn-Zn ferrites: Synthesis, characterization and application. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 15740–15763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dippong, T.; Levei, E.A.; Cadar, O. Recent advances in synthesis and applications of MFe2O4 (M=Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, Zn) nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Aggarwal, N.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, A. A review paper: Synthesis techniques and advance application of Mn-Zn nano-ferrites. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkova, O.; Gagani, A.I.; Karl, C.W.; Rocha, L.B.C.M.; Burlakovs, J.; Krauklis, A.E. Modelling of environmental ageing of polymers and polymer composites—Durability prediction methods. Polymers 2022, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y. Predictive modeling and degradation mechanisms of rubber sealing materials under stress-thermal oxidative aging for long-term sealing performance. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čubrić, I.S.; Čubrić, G.; Križmančić, I.K.; Kovačević, M. Evaluation of changes in polymer material properties due to ageing in different environments. Polymers 2022, 14, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ke, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment. e-Polymers 2023, 23, 20228089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tri, P.; Triki, E.; Nguyen, T.A. Butyl rubber-based composite: Thermal degradation and prediction of service lifetime. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Dou, Z.F.; Li, H.S.; Li, N.; Liu, X.R.; Zhang, W.F. Degradation behavior and aging mechanisms of silicone rubber under ultraviolet–thermal–humidity coupling in simulated tropical marine atmospheric environment. Polymer 2025, 328, 128398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Tang, D.; Ma, B.; Tian, W.; et al. Aging behavior, mechanism and lifetime prediction of liquid crystal polymer films under thermal and oxidative conditions for 5G communication applications. Polymer 2025, 334, 128772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, Y.; Shindo, T.; Kondo, H.; Ohtake, Y.; Kawahara, S. Ozone degradation of vulcanized isoprene rubber as a function of humidity. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 142, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, W.; Huang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yin, B. Effect of thermo-oxidative, ultraviolet and ozone aging on mechanical property degradation of carbon black-filled rubber materials. Buildings 2025, 15, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Zheng, X.; Zhan, S.; Zhou, J.; Liao, S. Study on the ozone aging mechanism of Natural Rubber. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 186, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, F. Protection mechanism of rubbers from ozone attack. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Cho, Y. Estimation of synthetic rubber lifespan based on ozone accelerated aging tests. Polymers 2025, 17, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyselá, G.; Hudec, I.; Alexy, P. Manufacturing and Processing of Rubber, 1st ed.; Slovak University of Technology Press: Bratislava, Slovak, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Mandot, S.K.; Agrawal, S.L.; Ameta, R.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Das Gupta, S.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Deuri, A.S. Study of metal poisoning in natural rubber–based tire tread compound. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 98, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsman, P. Review on the thermo-oxidative degradation of polymers during processing and in service. e-Polymers 2008, 8, 727–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, G. Swelling of filler-reinforced vulcanizates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1963, 7, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Yang, Z.H. The studies of high-frequency magnetic properties and absorption characteristics for amorphous-filler composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 391, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegaonkar, A.P.; Baskey, H.B.; Alegaonkar, P.S. Microwave scattering parameters of ferro–nanocarbon composites for tracking range countermeasures. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hao, L.; Zhang, X.; Tan, S.; Li, H.; Zheng, J.; Ji, G. A novel strategy in electromagnetic wave absorbing and shielding materials design: Multi-responsive field effect. Small Sci. 2022, 2, 2100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.P.; Arjmand, M.; Pötschke, P.; Krause, B.; Fisher, D.; Bose, S.; Sundararaj, U. Tuneable dielectric properties derived from nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes in PVDF-based nanocomposites. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 9966–9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Fan, R. The simultaneously achieved high permittivity and low loss in tri-layer composites via introducing negative permittivity layer. Compos. Part A 2024, 177, 107921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Ke, X.; Zhong, L.; He, Y.; Ren, X. Enhancing dielectric permittivity for energy-storage devices through tricritical phenomenon. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Randall, C.A.; Manias, E. Polarization mechanism underlying strongly enhanced dielectric permittivity in polymer composites with conductive fillers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 7596–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Datar, S. Wideband (8–18 GHz) microwave absorption dominated electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding composite using copper aluminum ferrite and reduced graphene oxide in polymer matrix. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruželák, J.; Kvasničáková, A.; Hložeková, K.; Džuganová, M.; Gregorová, J.; Vilčáková, J.; Gořalík, M.; Hronkovič, J.; Preťo, J.; Hudec, I. The study of electromagnetic absorption characteristics of manganese-zinc ferrite and MWCNT filled composites based on NBR. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2022, 95, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.S.; Kuřitka, I.; Vilcakova, J.; Machovsky, M.; Skoda, D.; Urbánek, P.; Masař, M.; Jurča, M.; Urbánek, M.; Kalina, L.; et al. NiFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by dextrin from corn-mediated sol gel combustion method and its polypropylene nanocomposites engineered with reduced graphene oxide for the reduction of electromagnetic pollution. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 22069–22081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hareesh, M.S.; Joseph, P.; George, S. Electromagnetic interference shielding: A comprehensive review of materials, mechanisms, and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 4510–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Herrera, C.A.; Gonzalez, H.; de la Torre, F.; Benitez, L.; Cabañas-Moreno, J.G.; Lozano, K. Electrical properties and electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of interlayered systems composed by carbon nanotube filled carbon nanofiber mats and polymer composites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaran, S.; Deshmukh, K.; Basheer Ahamed, M.; Khadheer Pasha, S.K. Recent advances in electromagnetic interference shielding properties of metal and carbon filler reinforced flexible polymer composites: A review. Compos. Part A 2018, 114, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neruda, M.; Vojtech, L. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of woven fabrics with high electrical conductivity: Complete derivation and verification of analytical model. Materials 2018, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruželák, J.; Kvasničáková, A.; Hložeková, K.; Plavec, R.; Dosoudil, R.; Gořalík, M.; Vilčáková, J.; Hudec, I. Mechanical, thermal, electrical characteristics and EMI absorption shielding effectiveness of rubber composites based on ferrite and carbon fillers. Polymers 2021, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.Z.; Wang, H.R.; Guo, X.; Wei, Y.C.; Liao, S. Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber. e-Polymers 2023, 23, 20230016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Huang, Y. Evolution of crosslinking structure in vulcanized natural rubber during thermal aging in the presence of a constant compressive stress. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 217, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, R.; Lu, D. Investigation of polymer aging mechanisms using molecular simulations: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezig, N.; Bellahcene, T.; Aberkane, M.; Abdelaziz, M.N. Thermo-oxidative ageing of a SBR rubber: Effects on mechanical and chemical properties. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Huang, G.; Lan, J.; Fu, J.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Ke, Z.; Guo, X.; et al. A study on the aging mechanism and anti-aging properties of nitrile butadiene rubber: Experimental characterization and molecular simulation. Polymers 2025, 17, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayefi, M.; Eesaee, M.; Hassanipour, M.; Elkoun, S.; David, E.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Thermal aging behavior and lifetime prediction of industrial elastomeric compounds based on styrene–butadiene rubber. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 3226–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, C.; He, A. Accelerated aging behavior and degradation mechanism of nitrile rubber in thermal air and hydraulic oil environments. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 2218–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, I.; Tayefi, M.; Eesaee, M.; Hassanipour, M.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Kinetic analysis of thermal degradation of styrene–butadiene rubber compounds under different aging conditions. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasland, F.; Chazeau, L.; Chenal, J.M.; Schach, R. About thermo-oxidative ageing at moderate temperature of conventionally vulcanized natural rubber. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 161, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruželák, J.; Kvasničáková, A.; Dosoudil, R. Thermo-oxidative stability of rubber magnetic composites cured with sulfur, peroxide and mixed curing systems. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2018, 47, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, M.; Kömmling, A.; Jaunich, M.; Wolff, D. Scission, cross-linking, and physical relaxation during thermal degradation of elastomers. Polymers 2019, 11, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Prabhahar, M.; Julyes Jaisingh, S.; Arun Prakash, V.R. Role of Magnetite (Fe3O4)-Titania (TiO2) hybrid particle on mechanical, thermal and microwave attenuation behaviour of flexible natural rubber composite in X and Ku band frequencies. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 016106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakošová, A.; Bakošová, D.; Dubcová, P.; Klimek, L.; Dedinský, M.; Lokšíková, S. Effect of thermal aging on the mechanical properties of rubber composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Polymers 2025, 17, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karekar, A.; Oßwald, K.; Reincke, K.; Langer, B.; Saalwächter, K. NMR Studies on the phase-resolved evolution of cross-link densities in thermo-oxidatively aged elastomer blends. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 11166–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Kong, Y.R.; Chen, X.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Lv, Y.D.; Li, G.X. High-temperature thermo-oxidative aging of vulcanized natural rubber nanocomposites: Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 41, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, J.; Horák, J.; Pilař, J.; Billingham, N.C.; Zweifel, H.; Nešpůrek, S. Influence of testing conditions on the performance and durability of polymer stabilisers in thermal oxidation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2003, 82, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Wang, X.; Huang, G.; Zheng, J.; Huang, J.; Li, G. Thermal ageing behavior of styrene-butadiene random copolymer: A study on the ageing mechanism and relaxation properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1704−1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Wan, C.; Song, P.; Xinyan, Y.; Wang, S. Efficient degradation of vulcanized natural rubber into liquid rubber by catalytic oxidation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 225, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guan, J.; Bai, W.; Gu, T.; Liu, H.; Liao, S. Role of divalent metal ions on the basic properties and molecular chains of natural rubber. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 452, 022057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lu, M.; Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. The effect of different forms of iron substances on the aging properties of carbon-black filled natural rubber. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 4214–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).