Abstract

The electronic stability and global reactivity of CuxScγ (x + y = 4) bimetallic nanoclusters were investigated within the framework of rational design of functional materials and active catalytic phases. M06-2X/def2-TZVP DFT was used for geometric optimization and electronic characterization, and global descriptors were calculated, including ΔEgap, chemical toughness, chemical potential, and electrophilicity. The orbital contribution was analyzed using DOS/PDOS with Multiwfn; PCA and ANOVA were applied to quantify descriptor–structure relationships. The results show that adding Sc changes the cluster’s electron density and stiffness in a consistent manner, enabling distinction between more stable and more reactive configurations. In particular, Cu3Sc is the most electronically stable, exhibiting the highest ΔEgap, while Cu2Sc2 shows a more tunable electronic response, consistent with scenarios requiring greater reactivity. Multivariate analysis shows that ΔEgap accounts for most of the electronic variability in the dataset, making it the primary descriptor for selection and design. Taken together, these results open a descriptor-guided path to designing active Cu–Sc phases for supported catalysis and to their assembly into tunable metal nanocomposites.

1. Introduction

Metallic nanoclusters are a new class of advanced materials whose electronic, magnetic, and structural properties can be manipulated with atomic precision. Their scientific and technological importance lies in their ability to exhibit quantum size effects, discrete electronic arrangements, and reactivity patterns not found in bulk phases, making them candidates for applications in heterogeneous catalysis, energy conversion, nanoelectronics, and spintronics [1,2]. Among these, Cu-Sc bimetallic clusters are versatile platforms, as the combination of a d10 transition metal (Cu) and a group 3 transition metal with partially filled 3d orbitals (Sc) can fine-tune electron density, structural rigidity, and chemical activation pathways [3,4,5].

These results have led to conflicting hypotheses regarding the mechanisms controlling electronic stability in metallic nanoclusters. While some studies point to orbital symmetry and electronic hardness as predictive factors of spin preference, others indicate that electronic correlation effects and second-neighbor repulsions are crucial for the energy-minimum topology [6]. Therefore, the accurate evaluation of global reactivity descriptors, such as chemical hardness, chemical potential, electronegativity, and electrophilicity index, has emerged as a tool for rationalizing the relative stability and redox susceptibility, as well as bond-breaking/formation, in these complex systems [7].

Although the present study focuses on gas-phase Cu-Sc nanoclusters, this approach is intentionally adopted to isolate intrinsic electronic effects without perturbations arising from specific supports, matrices, or interfacial environments [8]. Gas-phase clusters are widely employed as idealized electronic models to establish stability trends and descriptor-based criteria that are transferable to supported catalysts, metal–polymer nanocomposites, and functional interfaces, where the cluster constitutes the electronically active unit. In this context, gas-phase calculations provide fundamental insights into electronic stability and reactivity that guide the rational design of Cu-Sc active phases in composite and supported systems [9,10].

In this study, the electronic properties, stability, and global reactivity descriptors of Cu-Sc nanoclusters are analyzed using a multiscale approach combining density functional theory (DFT) with PCA analysis. This methodology reveals the most stable configurations and the correlation between the main electronic variables in chemical space. Unlike previous work, this study demonstrates that ΔEgap alone can explain more than 85% of the electronic variance, offering a novel single-descriptor strategy for the rational design of Cu-Sc nanoclusters. This strategy is statistically verified using PCA and ANOVA, creating a framework for predicting stability and reactivity in Cu-Sc Sc systems, a poorly understood family of bimetallic clusters. While conventional approaches employ multiple descriptors, here, ΔEgap emerges as the primary determinant of electronic stability, simplifying the analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction and Pre-Optimization of Cu-Sc Nano Clusters

CuxScy nanoclusters (x + y = 4) were initially constructed manually in GaussView 6.0.16 to explore representative geometries and possible alternative topological forms that can arise from symmetric and asymmetric arrangements of metal atoms. Cartesian coordinates (xyz) were obtained from these initial geometries to create the input files for the ORCA 6.1.0 program. In the first step of structural refinement, geometry optimizations were performed using the M06-2X functional and the def2-TZVP basis set, given their effectiveness for metal-containing systems and for describing valence d-orbital contributions. Specifically, M06-2X (a meta-hybrid GGA functional) has been broadly benchmarked for thermochemistry and electronic-structure trends in main-group and transition-metal chemistry, while the def2-TZVP basis provides a balanced triple-ζ description widely adopted for reliable geometry/energy predictions in molecular systems, including transition-metal compounds [11,12]. All optimizations were carried out without symmetry constraints, employing Berny’s algorithm and strict convergence criteria for energy and gradient. Spin state stability was verified through spin contamination analysis (⟨S2⟩) [13,14,15]. Frequency calculations were subsequently performed for all optimized nanoclusters at the same level of theory to confirm that the obtained structures correspond to true minima on the potential energy surface. All reported clusters exhibit zero imaginary frequencies, confirming their vibrational stability.

The structures that converged at this stage were used as a starting point for the complete analysis of electronic stability and reactivity descriptors.

2.2. Electronic Structure Calculations Oriented Towards Stability

The electronic stability of the nanoclusters was determined using various descriptors: total electronic energy (ET), HOMO–LUMO gap (ΔE), qualitative analysis of the density of states (DOS/PDOS), and energy curvature, an indicator of the structural rigidity of the minima. Calculations were performed using DFT with the M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory, which ensures consistency in geometric optimization and electronic characterization. Furthermore, additional analyses of natural orbitals and charge densities were conducted to evaluate the electronic stabilization resulting from Cu-Sc hybridization. Additionally, projected density of states (PDOS) were calculated using Multiwfn 3.8 to identify the participation of the Sc 3d and Cu 3d/4s orbitals at the boundary level and their effect on the overall stability and reactivity of the nanoclusters.

No separate electronic-structure calculations were performed at finite electronic temperatures, nor were electronic smearing parameters applied. All DFT calculations were carried out at the ground-state electronic structure (0 K). Temperature effects in the range 298–400 K were introduced exclusively through thermochemical corrections derived from vibrational analysis and statistical averaging, and therefore do not imply a physical thermal reordering of the HOMO and LUMO energy levels.

2.3. Extraction of Orbital Energies and Definition of Global Descriptors

The values of the frontier orbitals EHomo and ELumo were taken directly from the ORCA output files for each converged nanocluster. Using conceptual DFT theory and the Janak, Perdew, and Koopmans approximations, the global reactivity descriptors were calculated: chemical potential (μ), global hardness (η), electrophilicity (ω), maximum charge transfer (ΔNmax), and electron back-donation parameter (ΔEdonation). These descriptors define the global reactivity, charge-donor/acceptor capacity, and electronic stability of the CuxScγ nanoclusters [16]. For clarity and reproducibility, a worked numerical example illustrating the complete calculation chain of global reactivity descriptors (EHOMO, ELUMO, IE, EA, ΔEgap, μ, η, and ω) for a representative Cu-Sc nanocluster, including unit handling, is provided in the Supporting Information (Tables S1–S3).

2.4. Data Organization and Multivariate Analysis (PCA)

All electronic parameters (ET, ΔE, EHOMO, ELUMO, μ, η, ω, ΔNmax, ΔEdonation, and EA) were organized into normalized matrices using z-scaling. A multilevel statistical DFT–PCA was then performed to identify correlations between electronic properties, group clusters according to stability and reactivity, determine the descriptors that contribute most to system variability, and reveal compositional and structural trends associated with Cu and Sc incorporation. It is explicitly acknowledged that several global reactivity descriptors (e.g., μ, η, and ω) are algebraically derived from IE and EA and therefore are not strictly independent variables. However, PCA is used here as an exploratory, variance-based tool to capture collective electronic trends rather than to infer statistical independence among descriptors. The prior standardization of all variables ensures comparable weighting and prevents dominance by absolute magnitudes or built-in algebraic relationships, thereby highlighting relative variations across the Cu-Sc cluster dataset. PCA was performed using Originpro2025b, applying the Kaiser criterion (λ > 1). Varimax rotation was applied exclusively as an interpretative tool to enhance the physical readability of the loading patterns by maximizing the separation between descriptor contributions. Both unrotated and rotated PCA solutions were examined: the unrotated PCA was used to evaluate explained variance and identify the dominant descriptors controlling system variability, while the rotated solution was employed only to facilitate chemical interpretation. Importantly, the dominance of ΔEgap in the first principal component and the overall variance distribution remain unchanged upon rotation.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the comprehensive analysis of electronic stability and global reactivity of CuxScγ nanoclusters (x + y = 4) using descriptors derived from conceptual DFT, advanced statistical analyses (ANOVA, PCA), and structure–property relationships supported by multiscale calculations.

3.1. Global Reactivity Descriptors

Global reactivity descriptors for CuxScγ (x + y = 4) nanoclusters at different temperatures (298, 350, and 400 K) show how these change in magnitude depending on composition and temperature, giving quantitative information on the electronic stability, chemical toughness, and donor–acceptor capacity of the clusters.

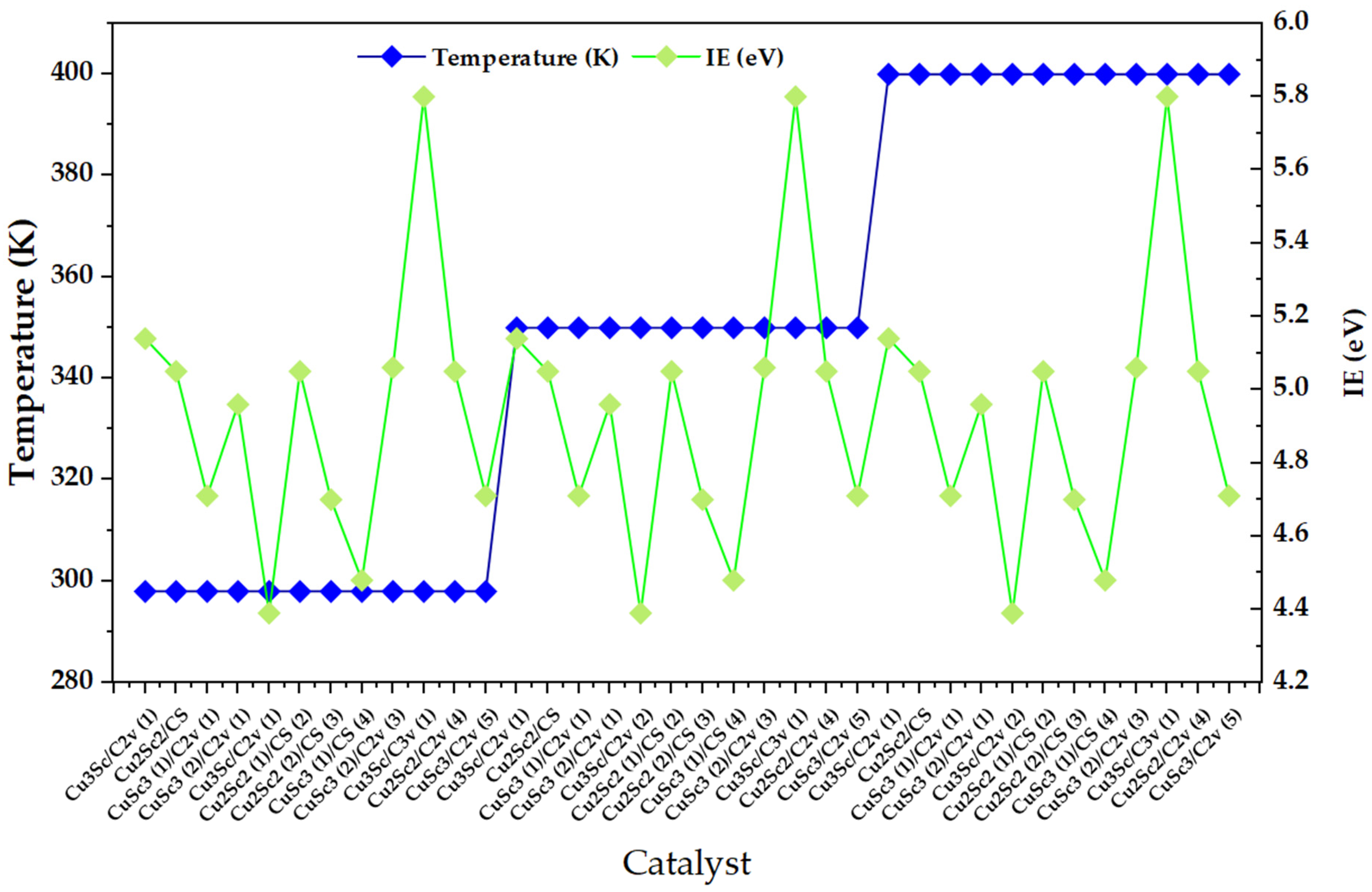

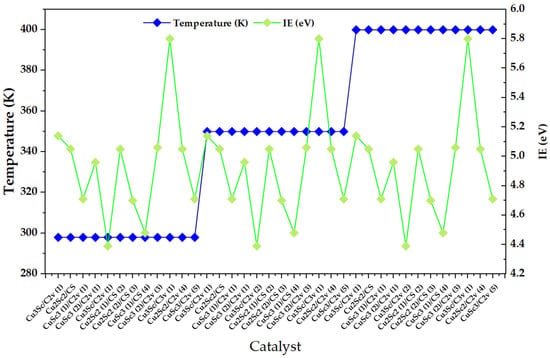

The most obvious feature is that the dispersion of IE within each thermal block (4.4–5.9 eV, with well-defined maxima and minima) is much greater than the net change in IE when moving from 298 to 350 and then to 400 K for the same pattern of configurations, which remains qualitatively similar at all three temperature levels (Figure 1). This suggests that, in the 298–400 K window, IE is mainly controlled by configuration-dependent factors (composition, symmetry, and multiplicity/spin state) and that temperature acts as a secondary modulator.

Figure 1.

Ionization energy (IE) distribution across Cu–Sc nanoclusters under discrete temperature conditions (298, 350, and 400 K).

This reading is consistent with experimental studies on metal nanoclusters where IE shows an intrinsic but subtle thermal dependence, typically an average decrease with temperature, attributed to the interaction between the ionic framework and electronic states, while variations between clusters remain dominated by their discrete electronic structure and isomeric “landscape.” In particular, Halder and Kresin report that the ionization energies of clusters show a predominant decrease with temperature and that the thermal effect, although measurable, is small compared to the variability between clusters, with a more pronounced response in small clusters [16]. In parallel, recent work on Cu clusters under finite temperature conditions emphasizes that configurational dynamics and the sampling of metastable isomers can alter trends with respect to static approximations, and that temperature can couple with structural rearrangements (including adsorption/charging-induced solid–liquid transitions), affecting thermodynamic properties and reactivity [17].

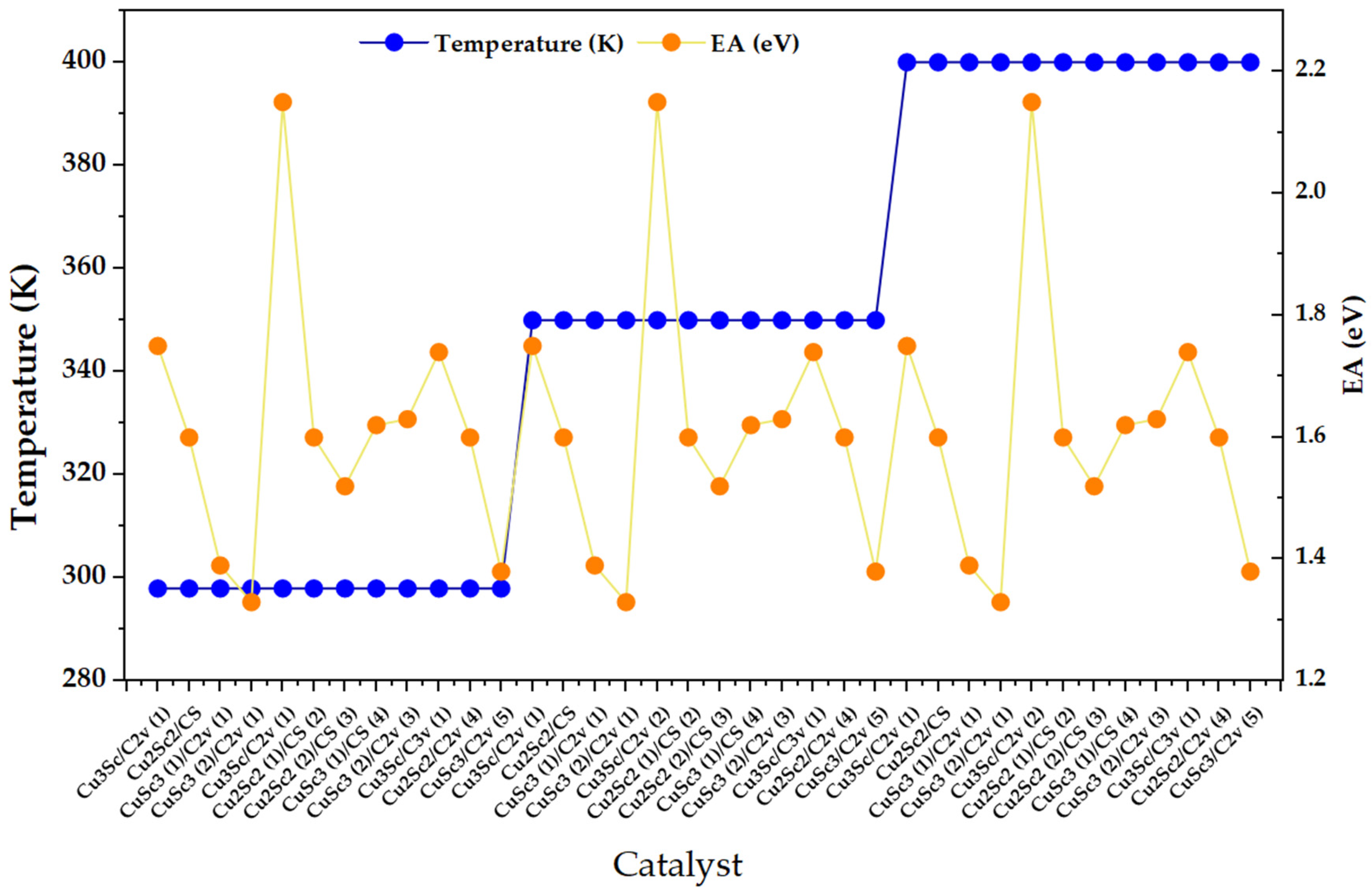

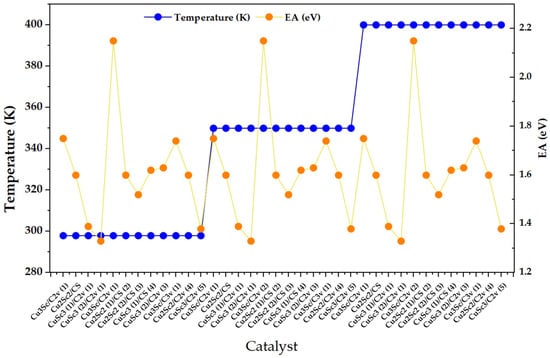

The Figure 2 clearly shows three temperature plateaus (298, 350, and 400 K), indicating that the set of catalysts is presented in three consecutive blocks. Within each block, the EA (right axis) exhibits a marked oscillatory variation between configurations, with maxima close to 2.2 eV and minima around 1.3–1.4 eV, without an obvious monotonic shift when moving from 298 to 350 and then to 400 K. This pattern suggests that, in the range evaluated, the EA is dominated by the structural/electronic identity of the nanocluster rather than by temperature, consistent with reports where the electronic thresholds of metal clusters show intrinsically small thermal changes in the absence of major structural transformations, as they are governed by effects such as thermal expansion [18].

Figure 2.

Electron affinity (EA) distribution across Cu-Sc nanoclusters under discrete temperature conditions (298, 350, and 400 K).

In parallel, EA peaks can be interpreted as configurations with particularly high acceptor capacity, consistent with reports where high electronic affinity units/ligands act as effective acceptors and generate charge transfer transitions (donor-acceptor) when donors and acceptors are orbitally/sectionally differentiated [19].

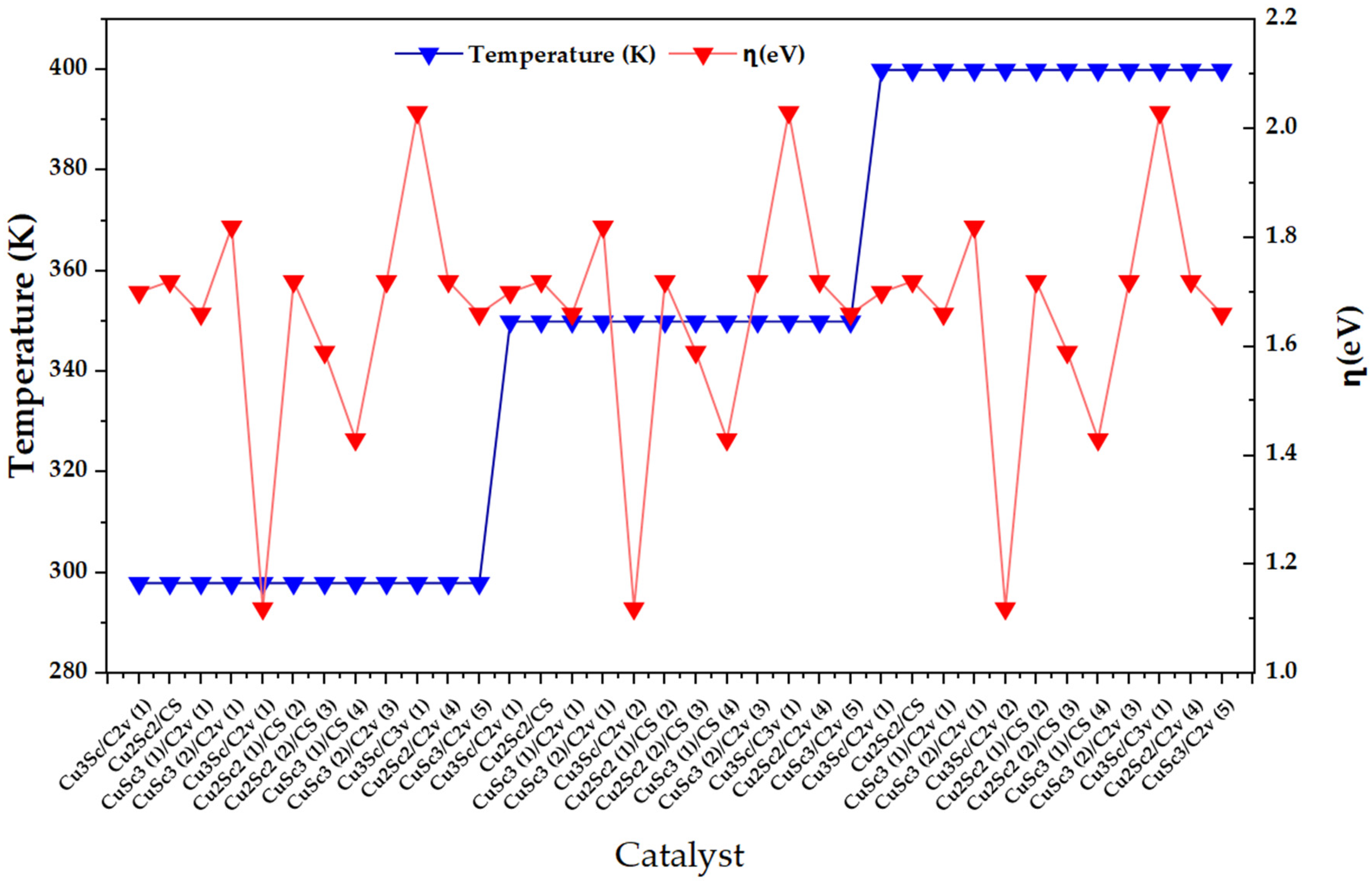

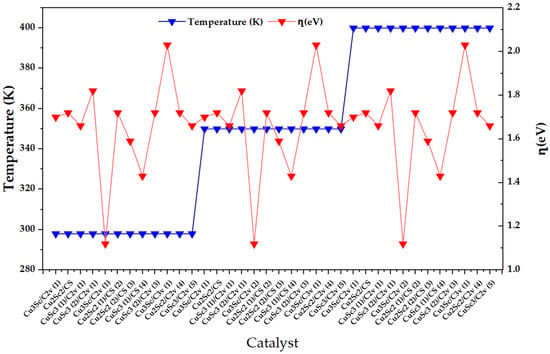

In Figure 3, η shows a wide dispersion (1.1–2.0 eV) between configurations, with point maxima and abrupt drops that reveal marked changes in electronic rigidity as composition/symmetry/multiplicity vary. In contrast, the temperature appears as three plateaus (≈298, 350, and 400 K), and within each block, no clear monotonic trend of η emerges; This suggests that, in this set, the electronic identity of each configuration dominates over the direct thermal effect, and that the main signal is configuration-dependent (structural/spin selectivity) rather than purely thermal.

Figure 3.

Global chemical hardness (η) of CuxScγ (x + y = 4) nanoclusters across catalyst configurations at 298, 350, and 400 K.

This interpretation is consistent with experimental evidence that, in metal nanoclusters, ionization (and, by extension, descriptors derived from IE/EA) tends to decrease with temperature, but with intrinsically small shifts and greater sensitivity in smaller clusters due to thermal expansion and structure–electronic coupling. Therefore, when the calculation design is “locked” by discrete sets of configurations, it is expected that the variability between isomers/states will partially mask the fine thermal shift [16]. From a reactivity perspective, the minima of η are consistent with scenarios where electron density is localized and regions with greater ease of charge redistribution appear: in nanoclusters, it has been argued that quantum confinement can concentrate charge at specific sites and that metrics such as electrostatic potential and dual descriptor allow rationalizing the preference for electrophilic events at sites of greater electronic activation. In this context, configurations with abnormally low η in the series are natural candidates for exhibiting greater donor/acceptor response and, therefore, greater electronic lability in the face of perturbations, while high η values point to more rigid electronic frameworks [20].

Finally, this interpretation is consistent with the contemporary framework according to which metallic nanoclusters exhibit discrete molecular electronic structures, where properties emerge in a highly sensitive manner to size, shape, composition, charge distribution, and electronic state (including spin), making it essential to adopt a rational design approach based on the targeted selection of target configurations and synthetic routes capable of isolating them. In this vein, it has been pointed out that progress in this area depends on methodologies that allow structural and compositional engineering at the subnanometer scale to modulate the structure and, therefore, the reactivity descriptors in a controlled manner. Additionally, under operating conditions, cluster fluxionality and entropic contributions can become decisive, so that relationships such as η vs. configuration constitute an initial quantitative criterion for prioritizing structural families that warrant more realistic treatments, such as assembly averages, isomeric sampling, or finite-temperature dynamics [21].

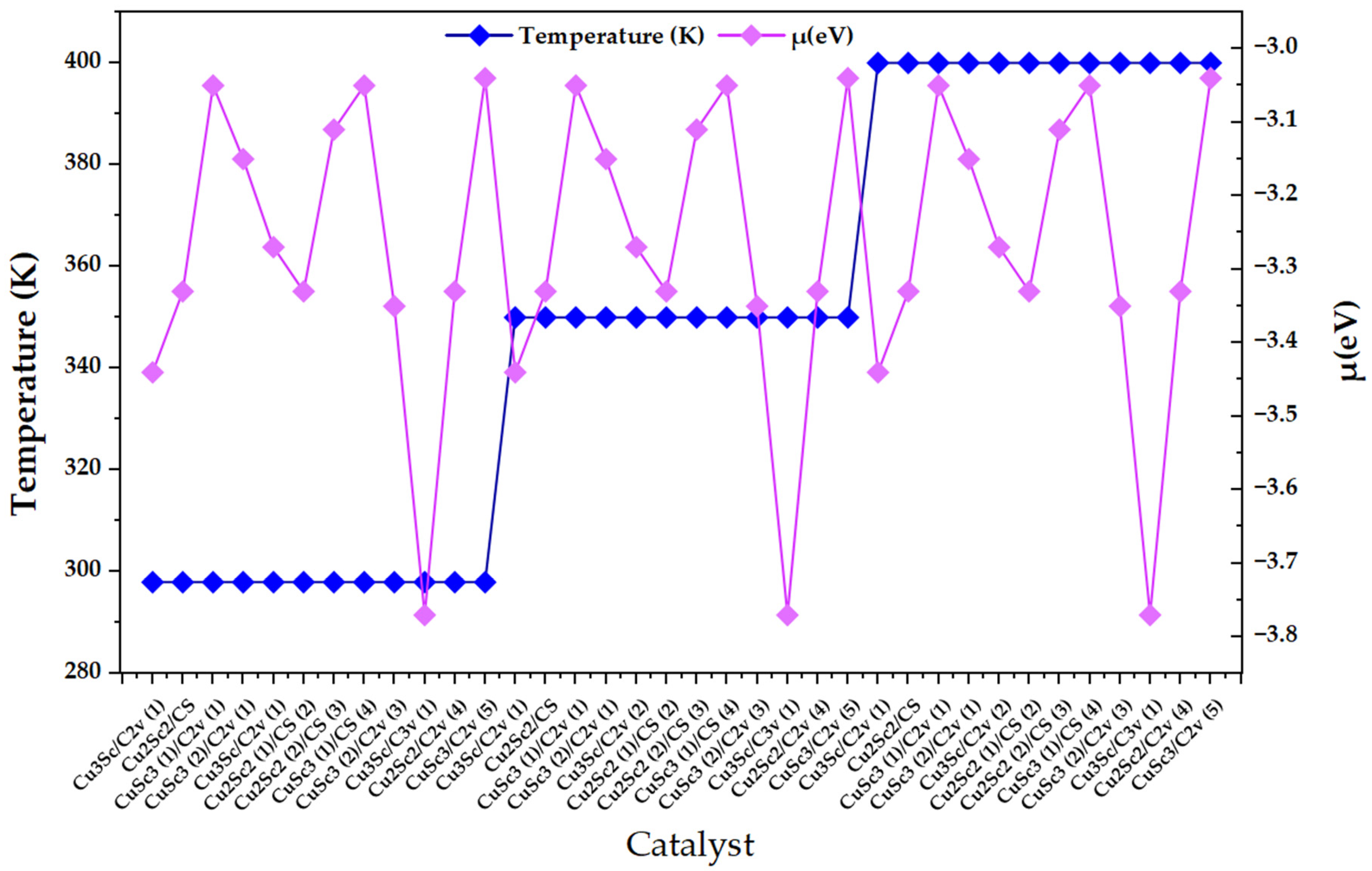

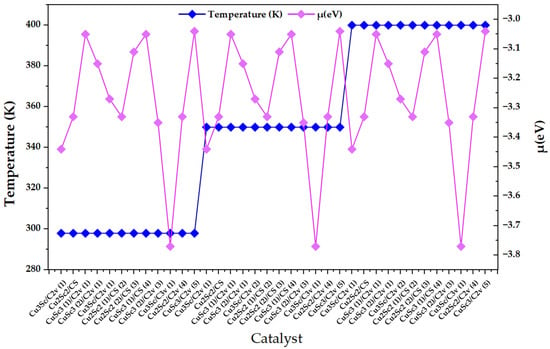

Figure 4 clearly shows three thermal plateaus (298, 350, and 400 K), confirming that the set of nanoclusters was ordered by discrete temperature blocks within the design. However, within each block, the chemical potential (μ) does not follow a monotonic trend with temperature; rather, it exhibits pronounced oscillations when moving from one configuration to the next (changes in composition/symmetry/multiplicity). This behavior is consistent with the physicochemical view of nanoclusters as “quasi-molecular systems” where the chemical potential is not a smooth macroscopic parameter, but a descriptor highly sensitive to the electronic identity of the cluster. In particular, in metallic nanoclusters, the chemical potential is the difference in free energy when the number of electrons changes, so it depends on the electronic state and, in finite systems, can vary discretely with excess electron charge and with electrostatic terms that scale with total capacitance. Along the same lines, experimental work on Au nanoclusters shows that the chemical potential is distributed around the Fermi level of the substrate and that its dispersion depends on size, reinforcing that the variability of μ mainly reflects finiteness/structure effects and not necessarily simple thermal control [22].

Figure 4.

Variation in the chemical potential (μ) as a function of the catalyst index for CuxScγ (x + y = 4) nanoclusters evaluated at 298, 350, and 400 K. Temperature is displayed on the left axis to indicate the block-wise computational design, while μ values are reported on the right axis.

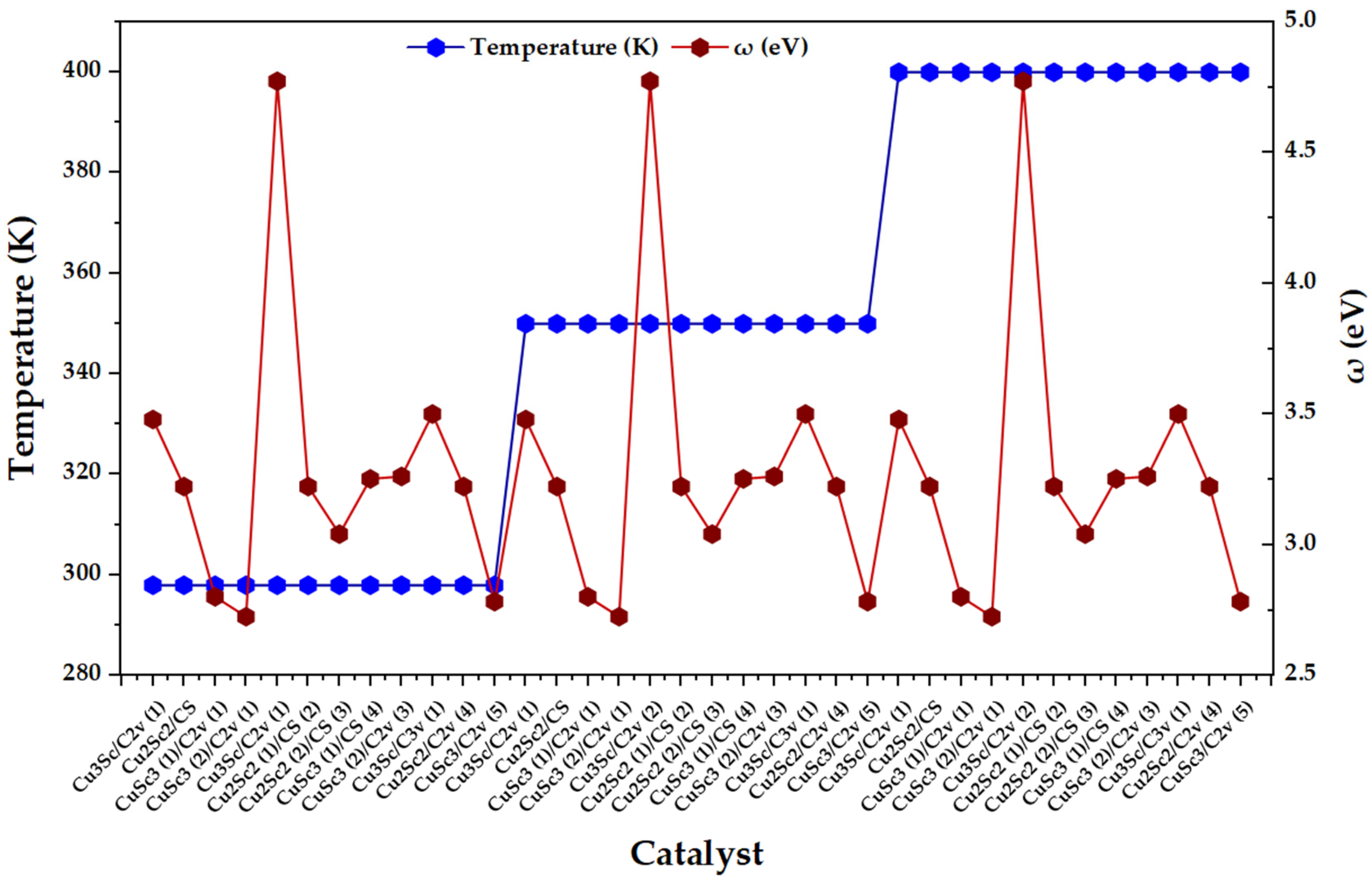

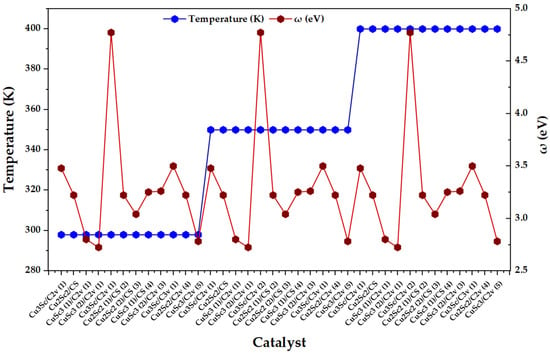

Figure 5 shows that ω does not exhibit a monotonic thermal dependence between 298 and 400 K, but rather a dominant intra-block dispersion throughout the catalyst index. This response is consistent with the derived nature of ω: moderate variations in μ or η between configurations can be amplified in ω, especially in regions of lower η, generating local maxima that reflect electronic states with greater overall acceptor capacity. Complementarily, when η increases without a proportional increase in μ2, ω attenuates, which is consistent with the dampening character of overall hardness on electrophilicity. In operational terms, the observed behavior suggests that the electronic heterogeneity imposed by composition, symmetry, and multiplicity dominates the hierarchy of ω within each temperature block of the factorial design [23].

Figure 5.

Temperature (K) and overall electrophilicity index, ω (eV), for the set of CuxScγ nanoclusters (x + y = 4) evaluated at 298, 350, and 400 K.

Additionally, the presence of specific maxima of ω is consistent with the literature on open-shell metal clusters, where electrophilicity and maximum charge acceptance capacity can exhibit local increases associated with the fine electronic structure. In particular, it has been reported that open-shell species can exhibit high values of ω and that the inclusion of spin–orbit coupling can increase ω, emphasizing that the electronic state is a first-order determinant of overall electrophilicity. Translated to the Cu-Sc series, the ω maxima identify configurations with a high μ2/η ratio, with a greater overall propensity to stabilize accepted charge, which positions them as priority candidates for charge transfer-controlled processes [24].

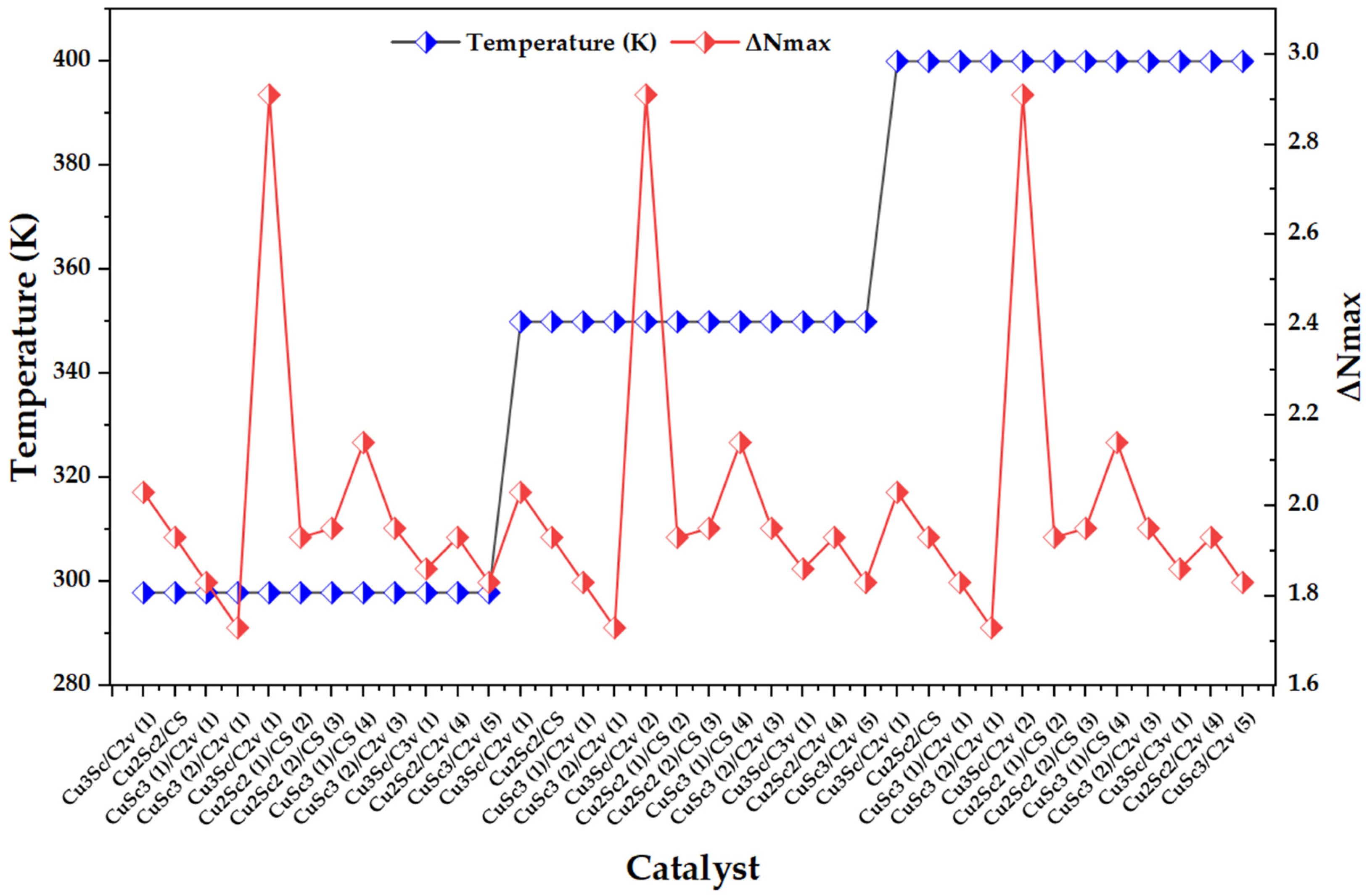

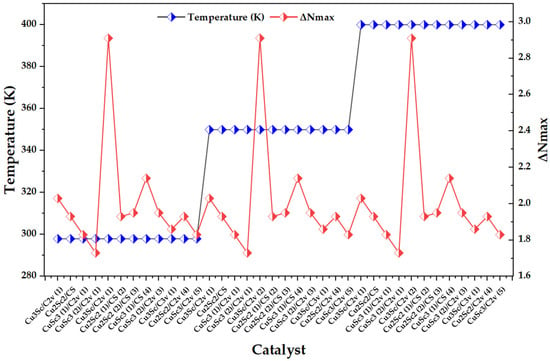

Figure 6 shows a thermal block design (298, 350, and 400 K) and, superimposed, the behavior of ΔNmax across the catalysts. Visually, ΔNmax remains within a narrow range for most configurations (1.7–2.1), while isolated peaks appear near 2.9–3.0, repeating in all three temperature blocks. This suggests that the dominant variability does not follow a continuous thermal gradient, but is governed by specific electronic cases associated with specific compositions/symmetries/multiplicities within the set [23].

Figure 6.

Variation in the maximum charge transfer (ΔNmax) across CuxScy (x + y = 4) nanoclusters as a function of the temperature block (298, 350, and 400 K).

The comparison with literature on metal nanoclusters shows a direct parallel: in Au clusters, it is reported that ΔNmax quantifies the maximum electron flow between donor and acceptor and that high values correlate with a greater tendency to accept charge, particularly in open-shell species, while low values are associated with greater stability and less propensity to acquire additional charge. The fact that, in your Cu-Sc series, ΔNmax exhibits well-isolated and repetitive maxima is consistent with this same framework: the descriptor is capturing configurations with a greater acceptor character driven by their electronic structure, rather than a continuous thermal effect [24]. In terms of temperature dependence, it is key to note that ΔNmax and ω do not introduce additional thermal sensitivity with respect to μ and η: by definition, ΔNmax depends functionally on μ and η, and ω depends on μ and η. Consequently, within the conceptual DFT scheme, temperature does not explicitly enter into these expressions; any variation when passing from temperature K can only emerge indirectly if the protocol changes the underlying electronic structure and, with it, modifies μ and/or η. Therefore, descriptors constructed from μ inherit their behavior: they co-vary with μ and η, but do not exhibit independent thermal dependence [23].

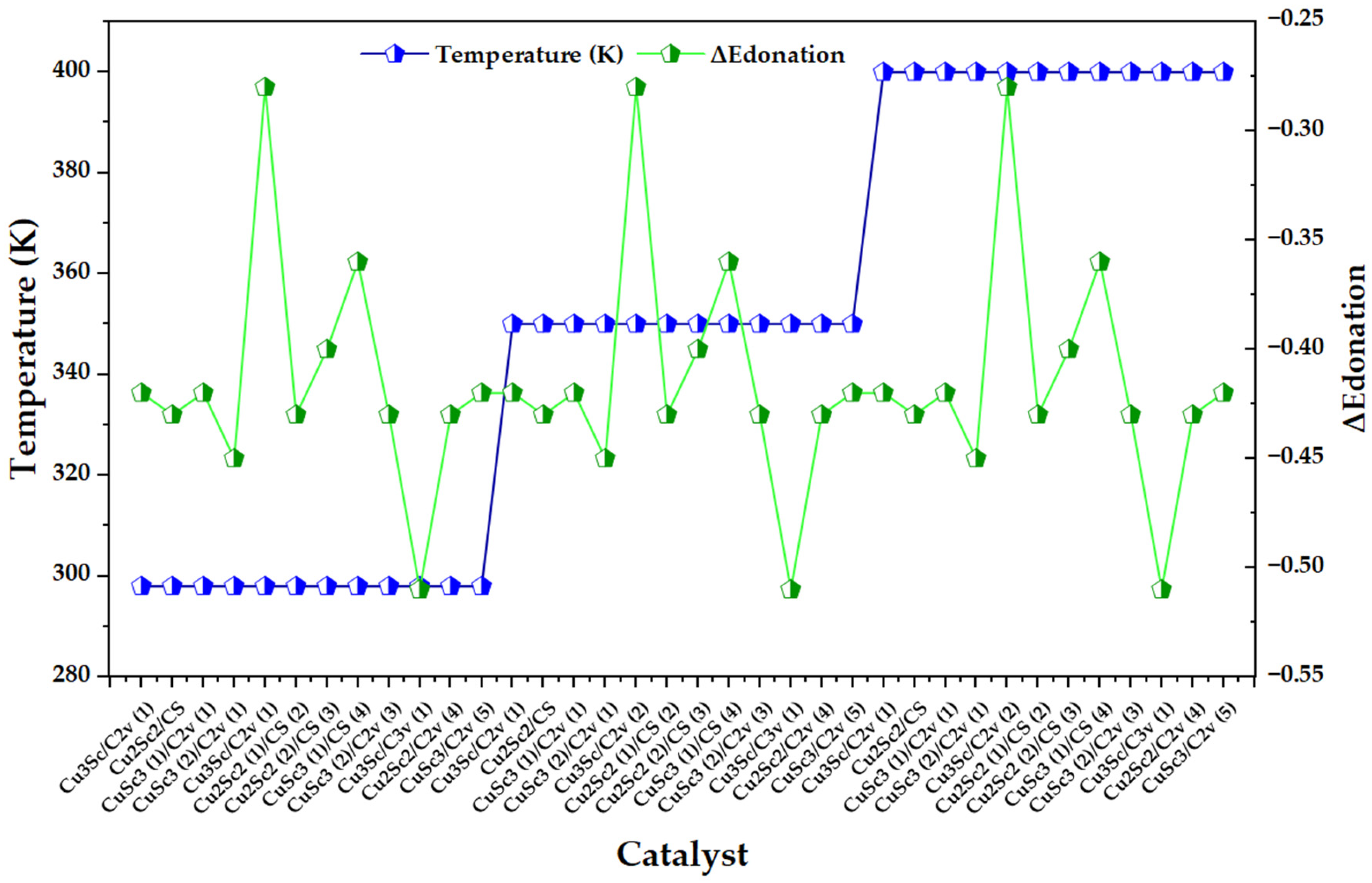

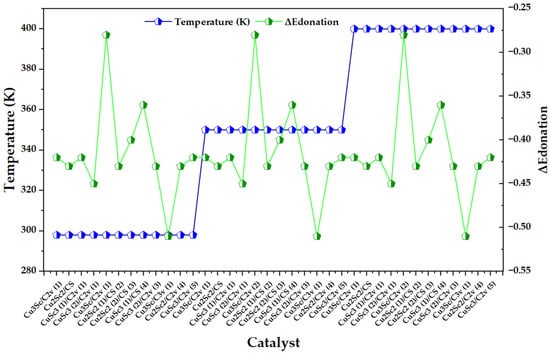

In Figure 7, the electronic back-donation parameter (ΔEdonation) exhibits pronounced oscillations between catalysts within each thermal block (298, 350, and 400 K), without a monotonic shift attributable to temperature; consequently, the signal is dominated by the electronic identity of each configuration (composition/symmetry/state) rather than by the imposed thermal scaling. This reading is consistent with a donor–acceptor type description: the intensity of the backdonation is mainly controlled by the energy alignment between occupied orbitals and vacant acceptors, as well as by the coupling between them, as formalized in the second-order perturbative term of NBO (dependent on the donor occupation, the Fock element, and the energy denominator) [25].

Figure 7.

Variation in the electronic back-donation energy parameter (ΔEdonation) across Cu-Sc configurations, superimposed with temperature blocks (298, 350, and 400 K).

When compared with the framework proposed by Gutsev et al., the most pronounced excursions in the series can be interpreted as cases where the energy denominator and/or Fij coupling change abruptly due to electronic structure effects, which amplify or attenuate backdonation stabilization. That work shows that back-donation emerges when the donor and acceptor are close in energy, and that the increase in density available for transfer increases Fij due to its relationship with overlap; by analogy, the configurations in Figure 7 that have a higher effective magnitude of ΔEdonation are the candidates for sustaining more intense donor–acceptor interactions within the Cu-Sc electronic configurational space. The same article warns that retrodonation effects can be highly sensitive to the flexibility of the basis (in this case, the inclusion of diffuse functions), to the point of qualitatively altering structural stability hierarchies (even reversing phase preference when capturing or not capturing retrodonation). Therefore, if ΔEdonation is used as a fine comparative descriptor between Cu-Sc isomers, it is advisable to treat its differences between configurations as electronically significant information only to the extent that the theoretical level guarantees a robust description of the donor-acceptor channels; otherwise, part of the observed dispersion could reflect limitations of description (not of the phenomenon) and bias the electronic classification [25].

Table 1 shows that the descriptors have well-defined ranges for each cluster and temperature. Some configurations have larger ΔEgap values, while others have smaller ΔEgap values. Furthermore, there are clear differences in IE and ω between the conditions. This simplified structure makes it easy to recognize electronic patterns, which will be statistically analyzed later. In this context, the Cu3Sc cluster is the most electronically hard, as it has the largest ΔEgap among the clusters. This large energy difference between the LUMO and HOMO translates into high electronic stability. A system with a large ΔEgap is less susceptible to electronic rearrangement and ionization, and therefore less reactive and more resistant to electronic changes. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies, which reported that Sc doping in Cu clusters widens the LUMO-HOMO gap, improving stability and decreasing reactivity [3]. Furthermore, chemical hardness (η) and electron affinity (A) are important descriptors for characterizing the reactivity of these systems. For Cu3Sc, greater chemical hardness translates into greater resistance to chemical alteration, as has been observed in other Cu-Sc clusters, such as Cu5Sc [3,21].

Table 1.

Average of global reactivity descriptors by cluster and temperature (298, 350, and 400 K).

3.2. Statistical Evaluation of Global Descriptors

To estimate the robustness and variability of the global descriptors, a descriptive statistical analysis was performed, including means, standard deviations, and functional ranges (Table 2). The descriptors IE, η, and ΔEgap exhibit the smallest relative variations, suggesting that electronic stability is well-defined across the metal alloys, whereas EA and ω are more variable, reflecting sensitivity to local charge density and the presence of Sc. Furthermore, the inclusion of temperatures of 298, 350, and 400 K allows for the study of the thermal smoothing of the descriptors and their influence on electronic hardness.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the global reactivity descriptors calculated for the CuxScγ nano-clusters.

Comparative temperature analysis reveals a systematic trend of decreasing η and a gradual increase in ω with increasing temperature, consistent with greater electron accessibility and decreased cluster rigidity. This thermal behavior suggests that overall reactivity increases slightly at 400 K, especially in Sc-rich nanoclusters, with implications for catalysis at this temperature. The electron affinity energy (EA) values obtained for Cux-Scy nanoclusters (x + y = 4) are 1.51, with a maximum of 2.28 and a minimum of 0.946. These values are comparable to those reported in article [26], where CuS nanoclusters show an EA range of approximately 1.25–3.53 eV, with a trend similar to that of the values obtained in this study. Furthermore, the analysis of the most stable structures also reveals an inverse relationship between the number of copper atoms and the electron affinity energy, reinforcing the observation that smaller nanoclusters are more reactive. The effects of spin–orbit coupling on similar properties for gold nanoclusters are analyzed [27]. Although the electron affinity energies for the Au clusters in this study (EA approximately 2.2–3.3 eV) are higher than those of the Cux-Scy systems, the correlation trend with reactivity and overall hardness observed in both articles is remarkably similar. In particular, the effects of spin–orbit coupling on reactivity, evidenced by changes in cluster hardness and softness, are also relevant for interpreting the results obtained for the Cux-Scy systems.

Regarding the chemical potential (μ), the values of −3.22 with a standard deviation of 0.22, and the minimum and maximum values of −3.80 and −2.77, respectively, for the Cux-Scy nanoclusters, also align with the trends observed in article [24], where the chemical potential of the CuS clusters shows a value in the range of −4.0 to −5.5 eV, suggesting a greater charge transfer capacity in these systems. This indicates that the Cux-Scy systems may have high reactivity, consistent with the values obtained in both studies.

3.3. ANOVA of the Electronic Descriptors ΔEgap, IE and ω

To verify whether the differences found between clusters were due to real structural changes or random fluctuations, a one-way ANOVA was performed using ΔEgap, IE, and ω as discriminant descriptors (Table 3). These parameters were selected because they represent the main electronic triad identified by PCA. The statistical analysis indicates significant differences among Cu3Sc, Cu2Sc2, and CuSc3, suggesting that each metallic composition belongs to a distinct electronic population and that stability and reactivity are not interchangeable.

Table 3.

ANOVA of the electronic descriptors ΔEgap, IE, and ω in the Cu-Sc nanoclusters.

For the three descriptors studied, the cluster terms exhibit F-values significantly larger than the error term, with very small p-values, indicating that the observed differences between the groups are not attributable to chance. Numerically, this suggests that the descriptors ΔEgap, IE, and ω vary consistently with changes in the system’s composition and design conditions. In particular, the magnitude of ΔEgap confirms its role as a primary descriptor of electronic stability, while IE and ω provide adequate sensitivity for differentiating between electronically more rigid or flexible clusters. The consistency between these results and the PCA analysis validates the electronic model and demonstrates that the system’s reactivity is determined by the Cu-Sc alloy. Clusters with a smaller ΔEgap, such as CuSc3, are more reactive because electrons can move more easily between orbitals, making them more susceptible to chemical reactions or structural changes.

Thus, ΔEgap not only predicts stability but also provides a measure of the clusters’ electronic reactivity at different temperatures. The results for Cu-Sc nanoclusters, based on variations in the descriptors ΔEgap, IE, and ω, are consistent with trends observed in the literature on metal clusters [28,29].

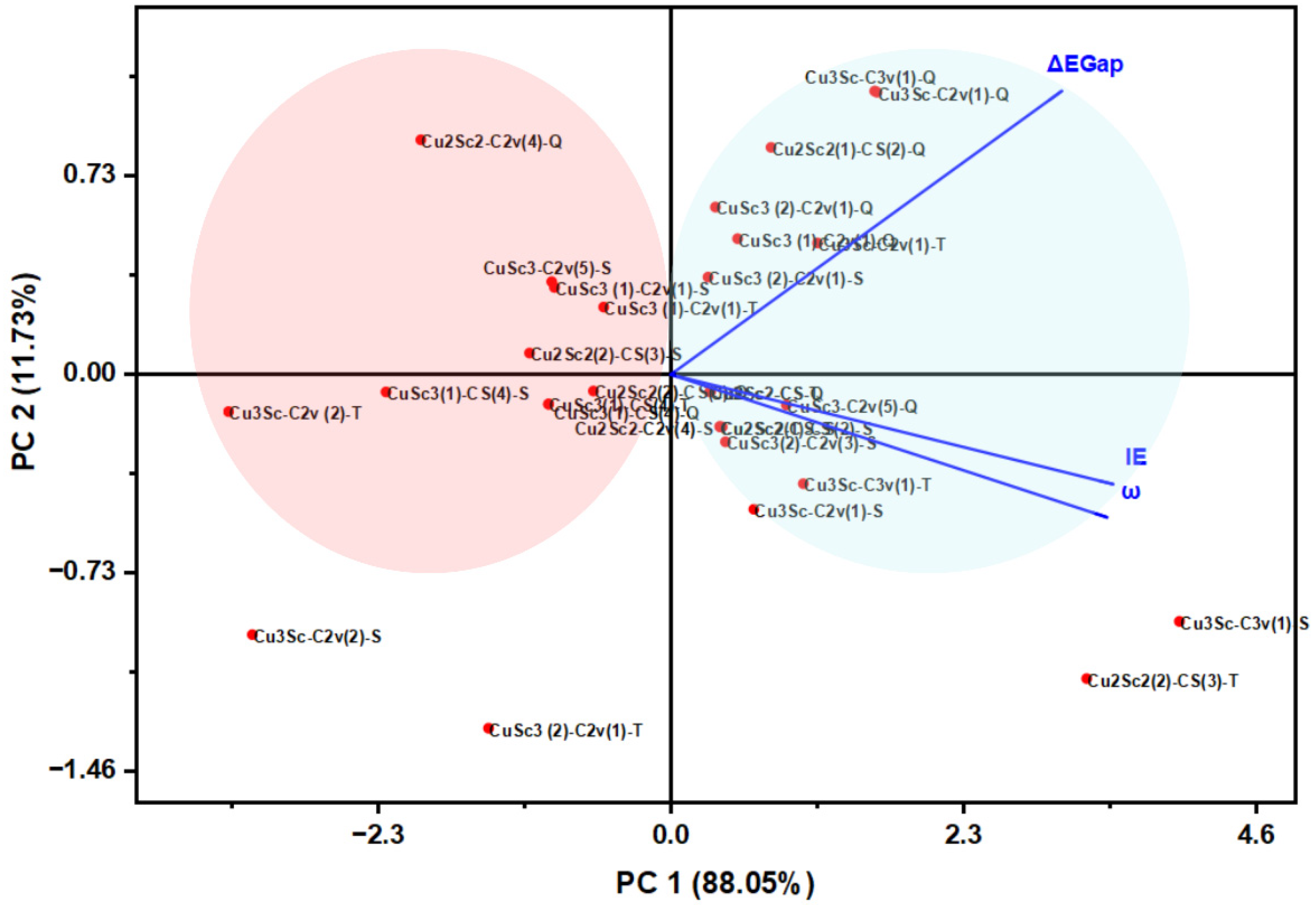

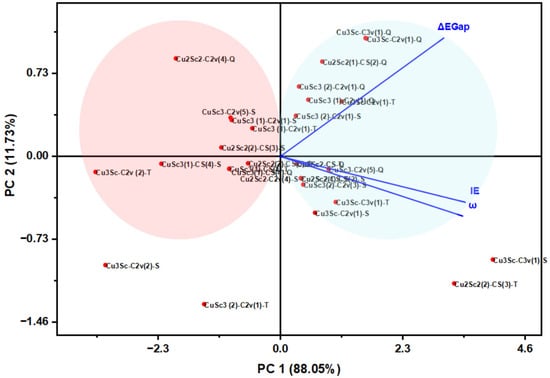

3.4. PCA Analysis of the Descriptors Associated with Electronic Hardness

PCA allowed visualization of the wind descriptors in the reduced space, revealing patterns of variability and natural groupings among the clusters (Figure 8). The first principal component (PC1) already explains 88% of the total variance and is saturated by ΔEgap, IE, and η, an axis of electronic stability and global hardness. The second component (PC2) groups the EA and μ information, associated with donor–acceptor capacity. This structure is able to reveal well-defined, rigid, and wide-range groups, as well as softer groups susceptible to reorganization.

Figure 8.

Biplot of the PCA showing the distribution of Cu-Sc nanoclusters and the charge vectors of ΔEgap, IE and ω.

Although some descriptors are mathematically related, the PCA results are not dominated by trivial algebraic correlations but rather reflect physically meaningful electronic trends. The leading principal component captures the collective response of descriptors associated with electronic hardness and charge acceptance, while the second component differentiates configurations with similar energetic gaps but distinct charge redistribution behavior. Consequently, the PCA axes are interpreted as electronic behavior modes rather than independent variables, allowing meaningful classification of Cu-Sc nanoclusters.

The two-dimensional map shows that Cu3Sc is located in the region of greatest electronic stability, while CuSc3 is located in the quadrant of high reactivity and electrophilicity. Cu2Sc2 is in the middle, demonstrating its amphoteric nature. The high correlation between ΔEgap and IE in PC1 indicates that a single electronic variable controls the behavior of the entire system, opening the door to design strategies based on descriptor-driven materials discovery. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that PC1 is mainly dominated by ΔEgap, suggesting that the HOMO-LUMO gap is the main determinant of electronic variability in the CuxScγ clusters. PC1 appears to be largely influenced by the Cu 3d and Sc 3d orbitals, indicating that these orbitals make the greatest contribution to the system’s electronic stability. Therefore, the orbital that actually controls PC1 is the one involving the 3d orbitals of Cu and Sc, which modulate the system’s reactivity and stability.

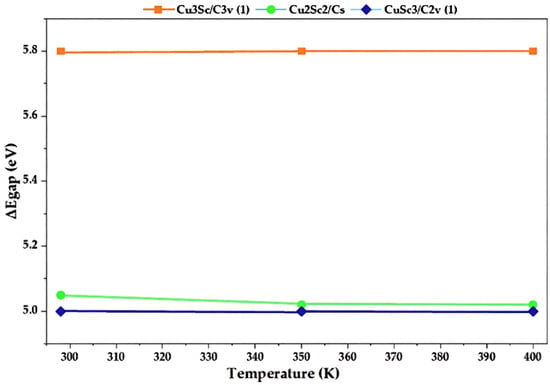

3.5. Effect of Temperature on Global ELECTRONIC Descriptors

In this section, temperature effects are primarily discussed in terms of thermodynamic stability and relative free energies of Cu-Sc isomers. The HOMO–LUMO gap (ΔEgap) is analyzed as a complementary electronic descriptor to rationalize the stability trends of the most favorable configurations, rather than as a direct thermodynamic observable.

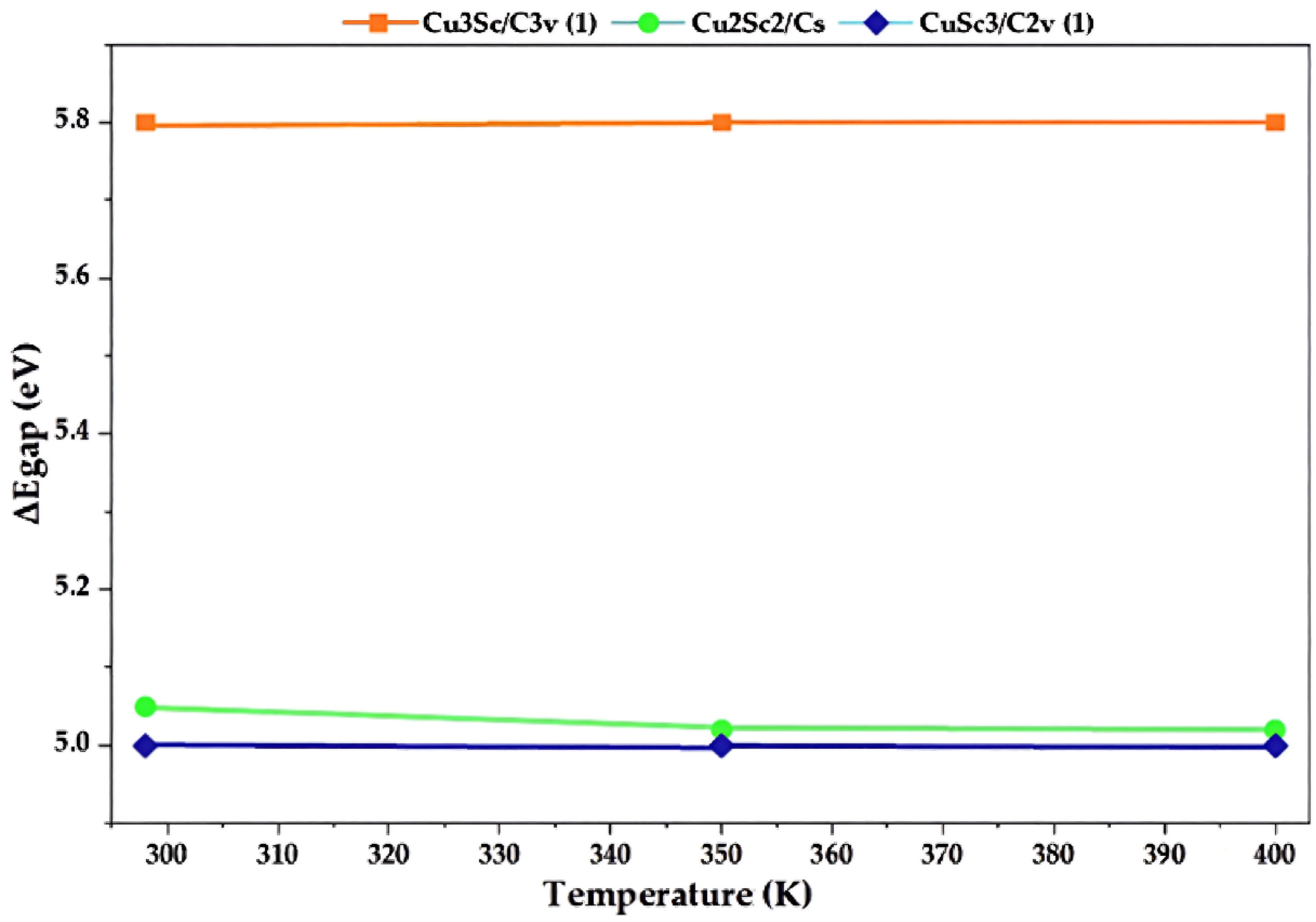

To directly illustrate the effect of temperature on the electron gap, Figure 9 shows the variation in ΔEgap as a function of temperature for the different CuxScγ nanoclusters considered. The graph shows, using curves or points, how the gap changes between 298, 350, and 400 K in each case. The symmetry values that presented the best ΔEgap value for each catalyst were selected (Table 1), allowing for a clear representation of the variability of the HOMO-LUMO gap at different temperatures.

Figure 9.

Variation in the HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔEgap) with temperature for the CuxScγ nanoclusters: Cu3Sc/C3v (1), Cu2Sc2/Cs and CuSc3/C2v (1).

Before discussing the physical implications of the temperature-dependent trends, it is important to clarify that no separate electronic-structure calculations were performed at finite electronic temperatures, nor were electronic smearing schemes applied. All HOMO and LUMO energies were obtained from ground-state DFT calculations (0 K). The temperature range of 298–400 K was introduced exclusively through thermochemical corrections and statistical averaging. Consequently, the variations observed in ΔEgap do not correspond to a physical thermal reordering of electronic orbitals, but rather to statistical adjustments derived from temperature-dependent free-energy corrections. In this context, references to Fermi–Dirac statistics describe the statistical framework underlying thermodynamic population effects, not explicit finite-temperature electronic structure calculations.

The values of ΔEgap remain constant between 5.0 eV and 5.8 eV across the studied temperature range, suggesting high electronic stability. This constant stability could reflect that the electronic interactions in this configuration are relatively independent of thermal effects, making it a thermodynamically stable structure at high temperatures. The energies of temperature-dependent descriptors (such as ΔEgap) are derived from thermodynamically corrected electronic energies, not from explicit calculations at T > 0. This implies that the observed changes in ΔEgap at 298 K, 350 K, and 400 K are not actual physical changes in the electronic structure, but rather statistical adjustments due to temperature effects on electronic-state populations. In other words, temperature changes the energies of the states according to Fermi-Dirac statistics, but does not physically rearrange the electronic orbitals [30]. Therefore, ΔEgap is a statistical fluctuation, not a physical alteration of the electronic structure. Based on the relative energy calculations, the most energetically favorable clusters were identified as those with values close to zero. This indicates considerable relative stability under the evaluated conditions, which allowed for the specific selection of the Cu3Sc-C2v(1)-S-298K, Cu2Sc2-CS-S-400K, Cu3Sc-C2v(2)-S-400K, and Cu2Sc2(2)-CS(3)-400K clusters, as they exhibited the lowest relative energies and, therefore, ensured greater thermodynamic stability. This approach, based on relative energy, was fundamental for selecting configurations that not only meet stability requirements but also correspond to the most favorable equilibrium points within the system, depending on the temperature and molecular structure considered. By selecting these clusters, an accurate representation of the most stable structural models is ensured, which are essential for evaluating thermodynamic processes such as pyrolysis and polymer fragmentation.

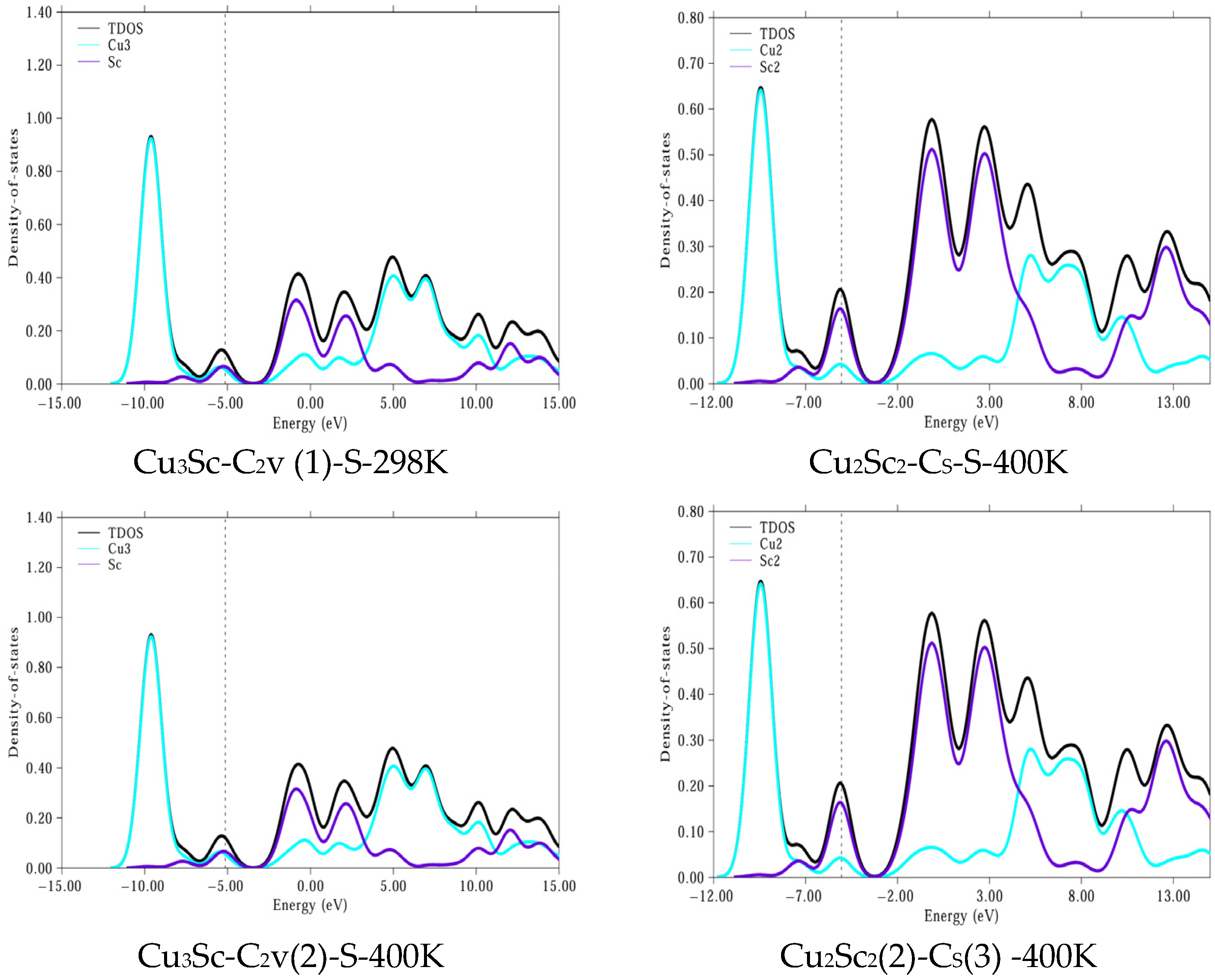

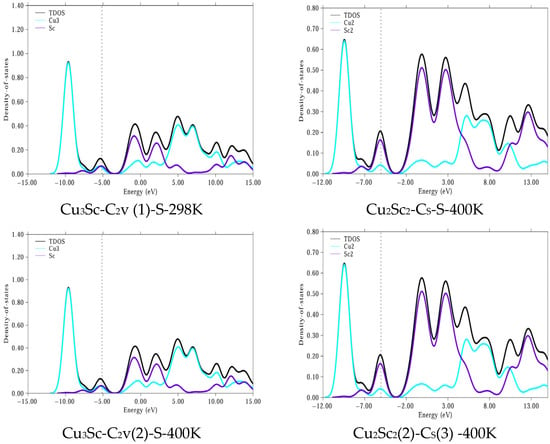

Analysis of the PDOS results for the CuxScγ configurations (Cu3Sc-C2v(1), Cu2Sc2-Cs, Cu3Sc-C2v(2)) shows that the electronic stability of these configurations is relatively constant at temperatures of 298 K and 400 K (Figure 10). In particular, the Cu3Sc-C2v(1) and Cu2Sc2-Cs configurations maintain a constant or nearly constant ΔEgap, indicating high electronic stability against thermal fluctuations. This behavior is characteristic of systems with strong electronic interactions between the Cu 3d and Sc 3d orbitals, which allow for greater resistance to thermal reactivity. In contrast, Cu3Sc-C2v(2) shows a slight decrease in ΔEgap at 400 K, suggesting greater susceptibility to thermal variations.

Figure 10.

PDOS for more stable clusters. The dashed vertical line corresponds to the Fermi energy (EF). All DOS curves are plotted using the same energy refer-ence (with energies aligned with EF [set to 0 eV/indicated at its calculated value]) to clearly separate occupied and un-occupied states.

Comparing these results with those of Liu et al. [31], a similar temperature dependence of the energy gap (ΔEgap) is observed. In their study, they found that electronic doping altered the energy gap without causing a significant structural reorganization, which agrees with our results. In both cases, electronic stability remains constant at high temperatures, without any physical transformations occurring in the orbitals.

Furthermore, the article by Fang et al. [32] analyzes how the electronic metal-support interaction (EMSI) between Ru nanoclusters and Fe atoms enhances O2 activation and facilitates HMF oxidation. This behavior highlights the importance of electronic interactions not only for electronic stability but also for catalytic reactivity, as shown in Ru/Fe1-NC catalysts. The formation of electronically enriched Ru species at the active sites enhances O2 activation, facilitating the conversion of HMF to FDCA. This is also related to the improved catalytic activity observed in Ru catalysts and their ability to perform free-base oxidation reactions, as demonstrated in the study.

Accordingly, temperature-dependent stability in the present study is governed by relative energetics and free-energy considerations, while ΔEgap serves as an auxiliary electronic indicator that helps interpret why certain isomers remain stable across the explored temperature range.

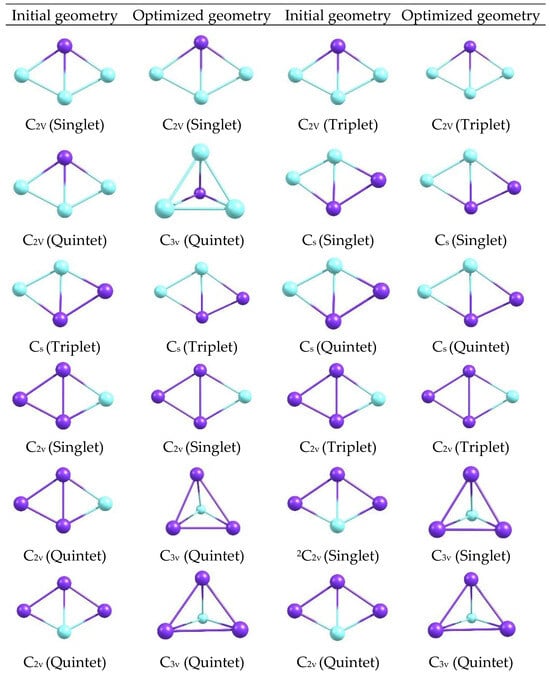

3.6. Structure–Property Relationships

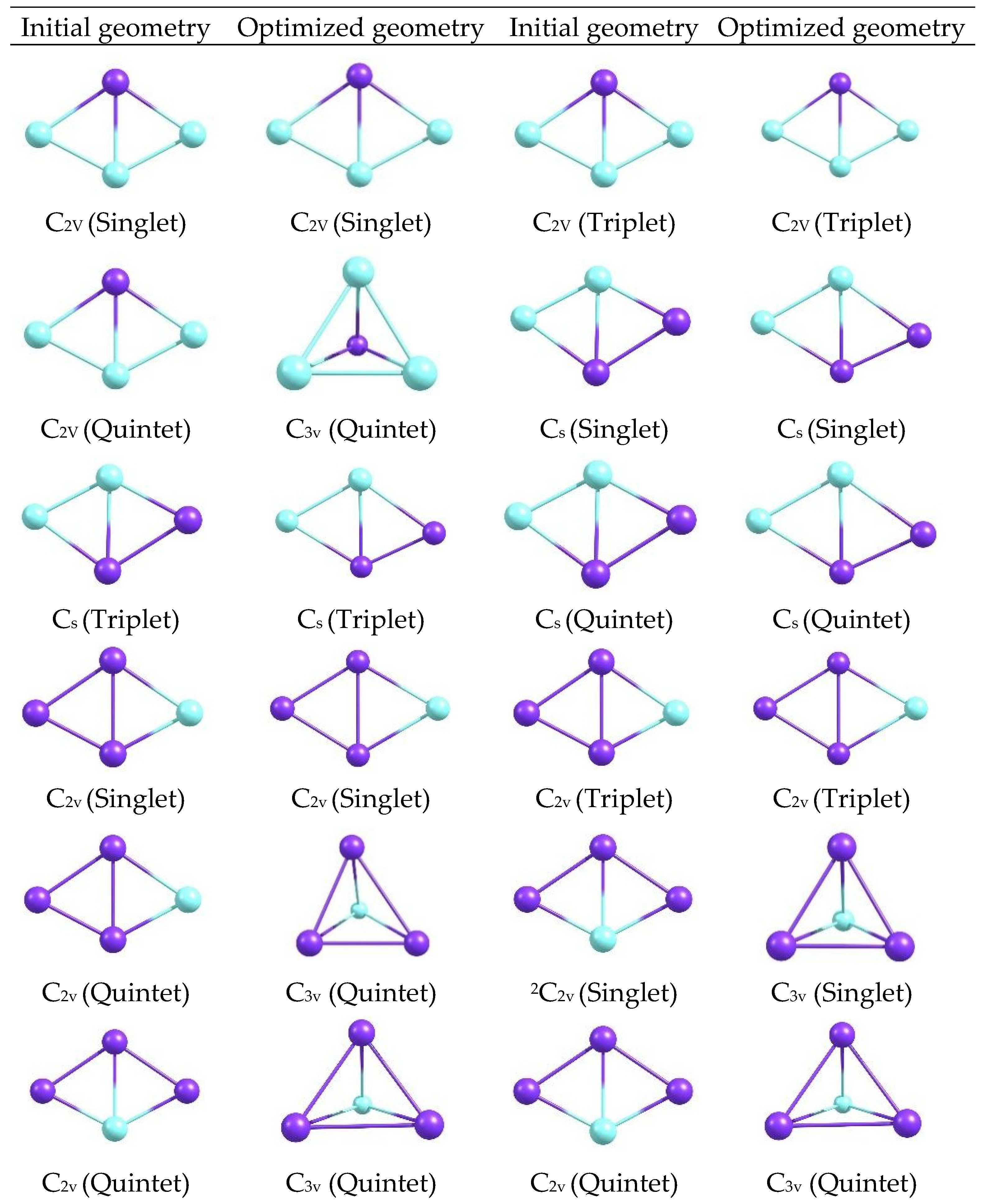

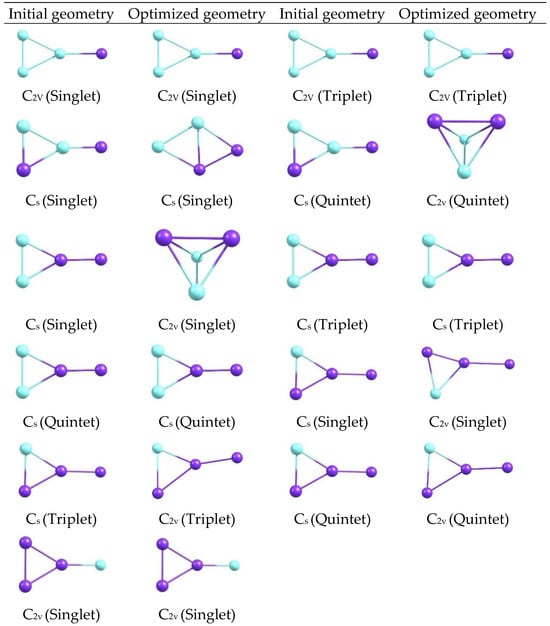

The optimized geometries of the CuxScγ (x + y = 4) catalysts with C2v and Cs symmetries (Figure 11), obtained with the M06-2X functional and the def2-TZVP basis in the Orca 6.1.0 software at different multiplicities at 298 K. In each panel, the relative positions of the Cu and Sc atoms are shown, clearly distinguishing the general architecture of the clusters and the arrangement of the metal centers.

Figure 11.

Initial and optimized geometries of CuxScγ clusters (x + y = 4) with C2v and Cs symmetries at 298 K. (The atoms represented in purple correspond to Sc, while the atoms in light blue correspond to Cu.).

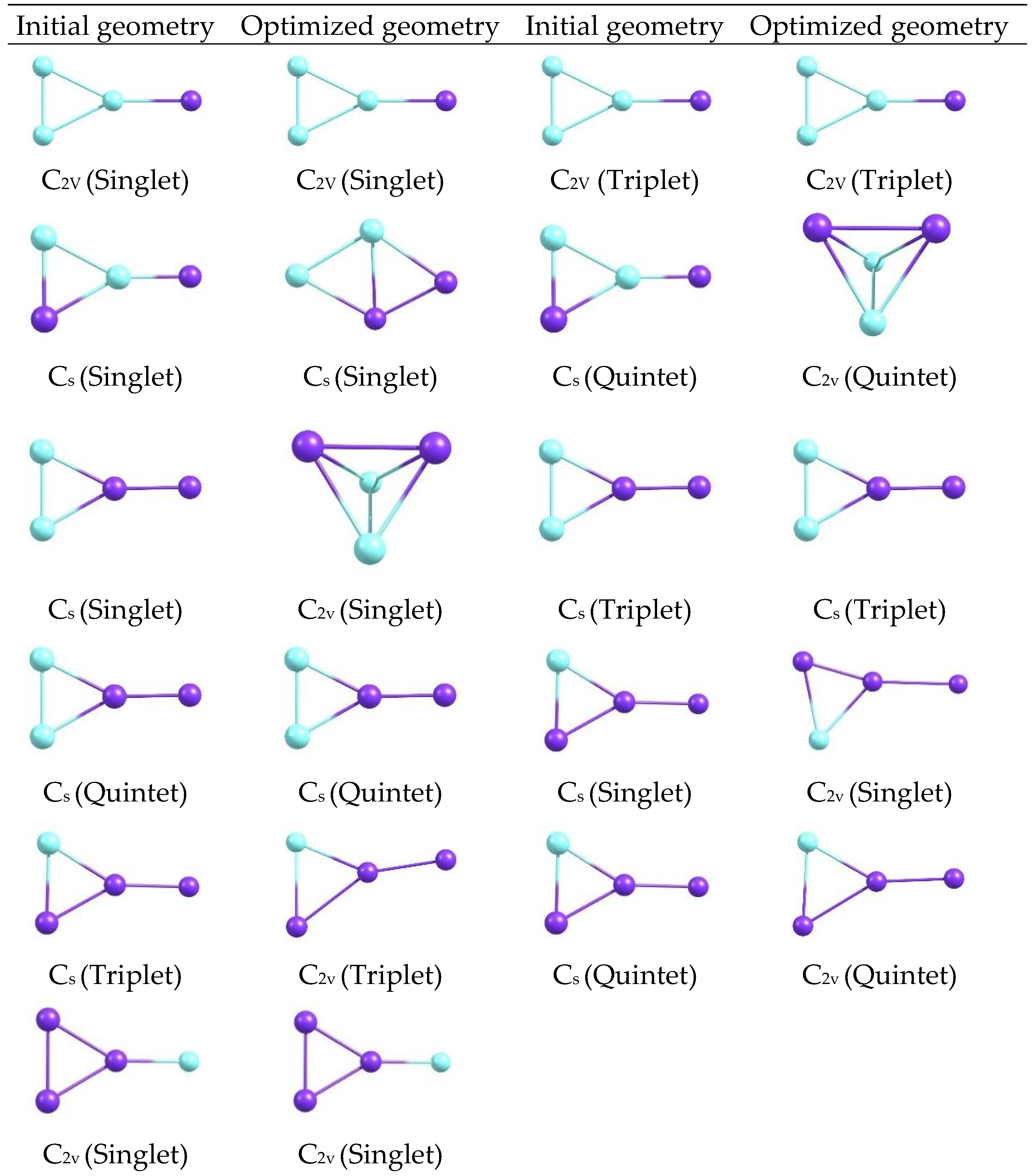

The optimized structures reveal compact configurations in which the metal atoms form well-defined arrangements, with visible differences between the C2v and Cs motifs. Changes in the orientation and length of the metal-metal and metal-ligand bonds are distinguished by symmetry, as are subtle variations in the overall shape of each cluster, providing a visual basis for relating these geometries to electronic descriptors. Additional optimized geometries are shown for CuxScγ (x + y = 4) catalysts with 2C2v, 2Cs, 3C2v, 4Cs, and 5C2v symmetries at 298, 350, and 400 K at the same level of theory (Figure 11 and Figure 12). A gallery of structures, classified by symmetry and state, is shown to visually compare how shapes change when different geometric and thermal arrangements are manipulated.

Figure 12.

Initial and optimized geometries of CuxScγ (x + y = 4) clusters with multiple symmetries at 298–400 K.

Comparing the panels in Figure 11 and Figure 12 reveals a diversity of shapes, ranging from the most symmetrical to the slightly deformed. Changes in symmetry and temperature modify the orientation of the metal atoms and the density of the cluster core. While only the visible shapes are described here, these morphological differences already suggest a correlation between the systems’ geometry and electronic behavior. When comparing the clusters, Cu3Sc is more electronically stable. Furthermore, the element Sc not only stabilizes the system but also participates in redistributing electronic charge between Cu and Sc. This interaction affects the electronic reactivity of the clusters, indicating that Sc further stabilizes the system, rather than merely modulating it. Analysis of the optimized structures of CuxScγ nanoclusters reveals compact configurations in which the metal atoms form well-defined arrangements, with significant differences between the C2v and Cs motifs. These configurations show variations in the orientation and length of the metal–metal and metal–ligand bonds, which directly affect the structural stability of the clusters. In particular, C2v symmetry configurations exhibit greater structural rigidity, with less bond-length dispersion and a more uniform distribution of metal atoms [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. This translates into superior electronic stability compared to the Cs configurations, which show greater structural flexibility and a more variable bond distribution, potentially leading to distortions and, ultimately, lower thermodynamic stability. This behavior is consistent with the results obtained by Taylor et al. [34], which demonstrate that compact configurations with high structural symmetry in gold nanoclusters contribute to greater electronic stability and thermal resistance. According to their research, a compact, well-packed structure reduces sensitivity to thermal fluctuations, thereby improving the overall stability of the system. Similarly, in CuxScγ nanoclusters, configurations with C2v offer a more stable structure that better withstands thermal changes, reflecting greater structural stability.

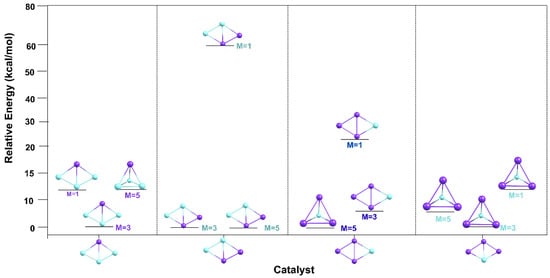

3.7. Influence of Spin State on Stability

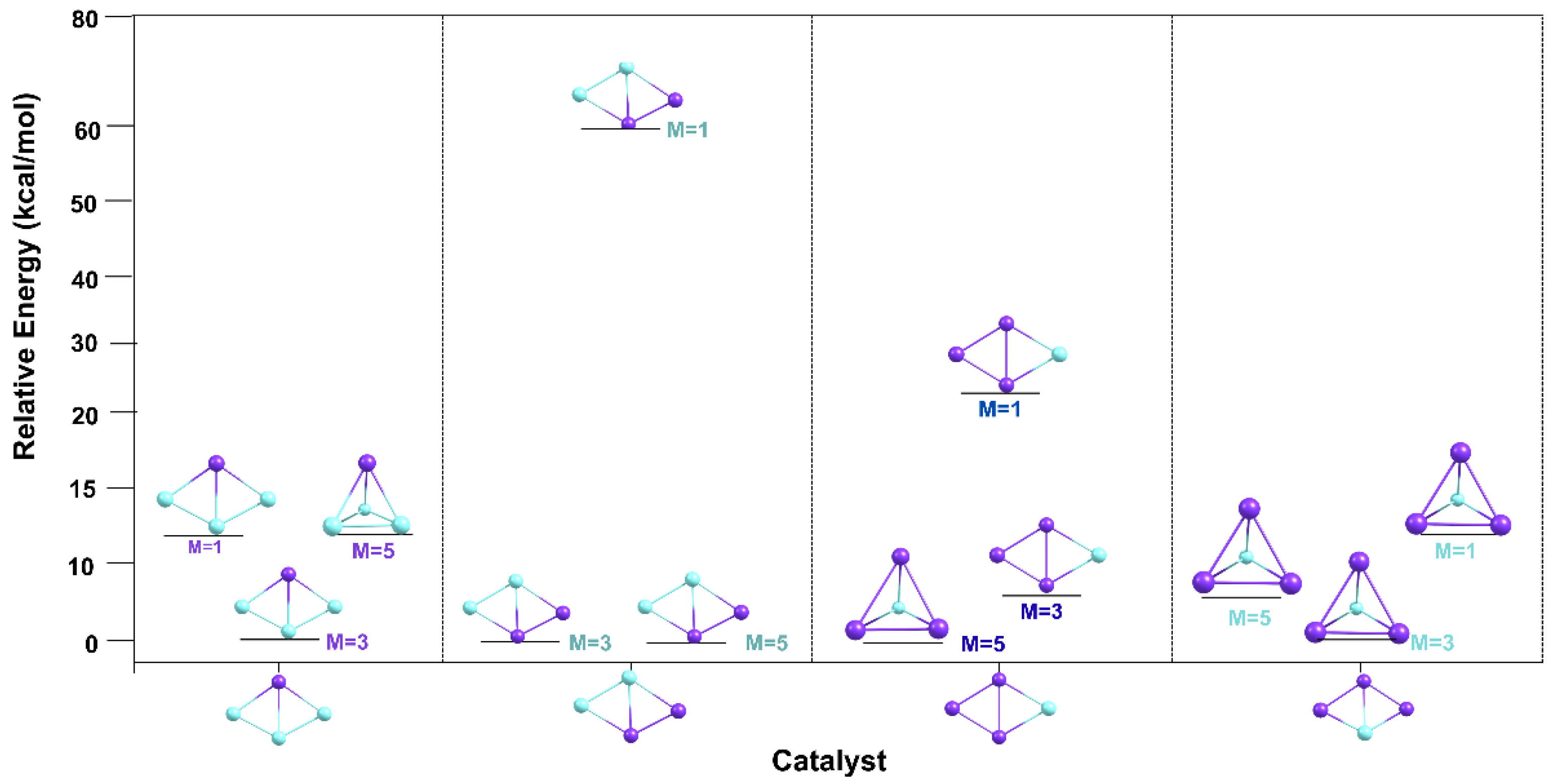

The relative stability of Cu3Sc and Cu2Sc2/CuSc3 clusters with C2v–Cs symmetries at 298 K as a function of spin multiplicity. The graph typically displays bars or points representing the relative energy for each cluster-spin state combination (singlet, triplet, and quintet), allowing a visual comparison of which multiplicity is most stable for each system, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the relative stability of the Cu3Sc and Cu2Sc2/CuSc3 (C2v–Cs) clusters at 298 K for different spin multiplicities.

The relative energies of the different catalysts vary with spin multiplicity (M = 1, 3, and 5), allowing a clear assessment of the impact of spin on the stability of the studied systems. In several cases, a specific spin state is found at a lower energy than others, indicating that this state is the most stable for that particular system. However, situations are also observed in which competition between two spin states is closer, suggesting that the stability of these systems could depend on additional factors beyond spin that influence the preference for a particular state.

Spin has a significant impact on the binding energy between the metal core and the ligand shell, which directly affects the overall stability of the nanocluster. In several studied systems, a specific spin state is consistently observed at a lower energy than others, suggesting that this state is the most stable for those clusters. This behavior is particularly evident in lower-spin states, such as M = 1, which are typically associated with greater energetic stability. This is because these spin states tend to have a more favorable electron distribution, minimizing electronic repulsions and optimizing atomic interactions between the metal core and ligands, thus improving system stability. Within the thermodynamic stability model, the stability of metallic nanoclusters, such as Au and Ag systems, depends on a delicate balance between the cohesive energy of the metal core (CE) and the binding energy of the shell to the core (BE). This balance can be disrupted by spin, which affects the electron distribution of atoms and thereby modifies interactions between the core and the shell. In some cases, however, a closer competition between two spin states is observed, as in clusters with M = 3 and M = 5. This competition suggests that, in these systems, spin is not the only determining factor of stability; other aspects, such as cluster structure and ligand arrangement, also play a crucial role [25].

Thus, spin can alter how metal clusters stabilize thermodynamically, depending on the amount of metal in the core and the organization of ligands in the shell. Different spin states alter the electronic configuration of atoms, which, in turn, affects atomic interactions and the overall stability of the system. This variability underscores the importance of considering spin as a key parameter for predicting nanocluster stability and for designing new materials with specific properties, such as stability and reactivity.

4. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates how the intelligent design of Cu-Sc nanoclusters can fine-tune their electronic properties and enhance the stability and reactivity of these mixed metal systems. The ability to modulate electronic stability by mixing Cu and Sc opens the door to functional materials with tunable properties for cutting-edge applications. In particular, the correlation between ΔEgap and global reactivity descriptors has proven to be a good predictor of the stability and reactivity of these systems, providing a simple and efficient approach to the rational design of Cu-Sc nanoclusters. The practical implications of these findings are relevant in areas such as supported catalysis, where Cu-Sc nanoclusters can serve as effective catalysts thanks to their ability to modulate electronic stability and optimize interactions with substrates. Furthermore, the ability of these nanoclusters to disperse in metallic nanocomposites opens the possibility of improving the mechanical and thermal properties of materials, making them useful for advanced structural materials in electronic devices and energy storage applications. Finally, Cu–Sc nanoclusters show promise for designing active phases for electrocatalysis and photocatalysis, especially in redox reactions and the decomposition of organic matter. The possibility of manipulating the reactivity of these active phases by modulating their electronic stability opens the door to new fuel cells and fuel arrays that are stable at high temperatures and have controlled reactivity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcs10020013/s1. Section S1 Worked numerical example of global descriptor calculation; Section S2 Complete PCA/ANOVA Dataset; Table S1: PCA score coordinates (PC1 and PC2) and cluster membership assignments for the Cu–Sc nanocluster dataset.; Section S3 Spin Contamination Analysis (<S2>) for Representative Cu–Sc Nanoclusters; Table S2: Representative ⟨S2⟩ values used to assess spin contamination for Cu–Sc nanoclusters (by composition, symmetry, multiplicity, and temperature). Section S4 PCA Loadings and Explained Variance; Table S3: PCA loading matrix (PC1–PC2) and explained variance ratios (eigenvalues, % variance, and cumulative variance) for the Cu–Sc descriptor dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.-F., R.G.-C. and R.O.-T.; Methodology, J.H.-F.; Software, J.H.-F.; Validation, J.H.-F.; Formal analysis, J.H.-F., R.G.-C. and R.O.-T.; Investigation, J.H.-F., R.G.-C. and R.O.-T.; Resources, J.H.-F.; Data curation, J.H.-F.; Writing—original draft, J.H.-F. and R.O.-T.; Writing—review & editing, J.H.-F., R.G.-C. and R.O.-T.; Visualization, J.H.-F., R.G.-C. and R.O.-T.; Supervision, J.H.-F.; Project administration, J.H.-F.; Funding acquisition, J.H.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maity, S.; Kolay, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Devi, A.; Rashi, N.; Patra, A. A comprehensive review of atomically precise metal nanoclusters with emergent photophysical properties towards diverse applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 54, 1785–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoine, R.; Broyer, M.; Dugourd, P. Metal nanoclusters: From fundamental aspects to electronic properties and optical applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2023, 24, 2222546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Q. Structures, stability and electronic properties of bimetallic Cun−1Sc and Cun−2Sc2 (n = 2–7) clusters. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 026524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, N.; Uğur, Ş. Electronic and phonon properties of Sc-TM (TM=Ag, Cu, Pd, Rh, Ru) compounds. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 47, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Lv, L. Quantum chemical calculations of thermodynamic and mechanical properties of the intermetallic phases in copper–scandium alloy. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2017, 16, 1750056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduner, E. Symmetry and Electronic Properties of Metallic Nanoclusters. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulla, H. The Effect of Global and Local Chemical Reactivity Descriptors in the Determination of Properties of Transition Metal Clusters. SINET Ethiop. J. Sci. 2024, 46, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.M.; Bernhardt, T.M. Gas phase metal cluster model systems for heterogeneous catalysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 9255–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Curtiss, L.A.; Fortunelli, A.; Vajda, S. Perspective: Size selected clusters for catalysis and electrochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 110901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Ji, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Synthetic strategies of supported atomic clusters for heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, A.J.; Sarmah, K.; Yashmin, F.; Borah, R.R.; Baruah, I.; Deka, R.P.; Guha, A.K. σ-Aromaticity in planar pentacoordinate aluminium and gallium clusters. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Habibzadeh, M. Theoretical study of geometry, stability and properties of Al and AlSi nanoclusters. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2016, 6, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcomson, T.; Repiščák, P.; Erhardt, S.; Paterson, M.J. Protocols for Understanding the Redox Behavior of Copper-Containing Systems. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45057–45066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Chattaraj, P.K. Chemical reactivity from a conceptual density functional theory perspective. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Kresin, V.V. Nanocluster ionization energies and work function of aluminum, and their temperature dependence. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 164313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.-Y.; Shi, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J. Charge State Dependence of Phase Transition Catalysis of Dynamic Cu Clusters in CO2 Dissociation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 27615–27623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.R.; Wang, Z.; Han, B.L.; Zhang, C.K.; Zhang, S.S.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Yu, J.H.; Li, T.D.; Li, Y.Z.; Tung, C.H.; et al. Ag22 Nanoclusters with Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Protected by Ag/Cyanurate/Phosphine Metallamacrocyclic Monolayers Through In-Situ Ligand Transesterification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiong, L.; Sun, G.; Tang, L.; Zhang, J.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, M. The mechanism of metal exchange in non-metallic nanoclusters. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Kang, X.; Zhu, M. Preparation Methods of Metal Nanoclusters. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202404528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Bhatt, A.; Dash, D.; Sharma, N. DFT calculations on molecular structures, HOMO–LUMO study, reactivity descriptors and spectral analyses of newly synthesized diorganotin(IV) 2-chloridophenylacetohydroxamate complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.H.; Palomo, J.P.; Ortega-Toro, R. Application of DFT and Experimental Tests for the Study of Compost Formation Between Chitosan-1,3-dichloroketone with Uses for the Removal of Heavy Metals in Wastewater. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Chattaraj, P.K. Electrophilicity index revisited. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 44, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, M.J. Spin-Orbit Coupling Effect on the Electrophilicity Index, Chemical Potential, Hardness and Softness of Neutral Gold Clusters: A Relativistic Ab-initio Study. HighTech Innov. J. 2020, 2, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsev, L.G.; Aldoshin, S.M.; Gutsev, G.L. Influence of back donation effects on the structure of ZnO nanoclusters. J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41, 2583–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohgi, T.; Sakotsubo, Y.; Fujita, D.; Ootuka, Y. Measurement of Au nanocluster chemical potential by the analysis of Coulomb staircase. Hyomen Kagaku (Surf. Sci.) 2005, 26, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Chakraborty, T. Density Functional Approach: To study Copper sulfide nanoalloy clusters. Acta Chim. Slov. 2019, 66, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-G.; Shen, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.-F.; Tang, Y.-N.; Chen, W.-G.; Ren, B.-Z. Insights into the structures and electronic properties of Cun+1 μ and CunS μ (n = 1–12; μ = 0, ±1) clusters. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, A.; Mohammadnejad, S. A DFT-Based Investigation of the properties of gold nanoclusters up to Au20. Res. Sq. 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, T.; Hines, W.; Alraddadi, S.; Budnick, J.I.; Sinkovic, B. Origin of the temperature dependence of the energy gap in Cr-doped Bi2Se3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 8624–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Jia, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Peng, L. Strong electronic metal-support interaction between Ru nanoclusters and Fe single atoms enables efficient base-free oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 365, 124994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xiong, L. Core packing-dependent metallic transition in thiolate-protected gold nanoclusters: Twinned-FCC vs. pure-FCC configurations. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 10383–10386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S.S.; Babu, M.H.; Imame, S.M.; Hossain, M.K.; Chowdhury, F.I. Combined DFT and experimental study of CuO and Ni–CuO nanoparticles: Structural characterization, photocatalytic degradation, and antimicrobial activities. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 41479–41496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.G.; Mpourmpakis, G. Thermodynamic stability of ligand-protected metal nanoclusters. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, J.; Lambis, H.; Reyes, R.V. Application of Pyrolysis for the Evaluation of Organic Compounds in Medical Plastic Waste Generated in the City of Cartagena-Colombia Applying TG-GC/MS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, J.; Prieto Palomo, J.; Ortega-Toro, R. Application of Computational Studies Using Density Functional Theory (DFT) to Evaluate the Catalytic Degradation of Polystyrene. Polymers 2025, 17, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, J.; Gomez, J.; Marquez, E. Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater. Molecules 2025, 30, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, J.A.; Prieto Palomo, J.A.; Toloza, C.A.T. Theoretical/Experimental Study of the Heavy Metals in Poly(vinylalcohol)/Carboxymethyl Starch-g-Poly(vinyl imidazole)-Based Magnetic Hydrogel Microspheres. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, J.; Prieto Palomo, J. Synthesis and Characterization of MAPTAC-Modified Cationic Corn Starch: An Integrated DFT-Based Experimental and Theoretical Approach for Wastewater Treatment Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.