Abstract

Background: Narrow duplicated internal auditory canal (IAC) is a rare congenital malformation frequently associated with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss. Case Presentation: We present a one-year-old girl with bilateral narrow duplicated IAC and profound hearing loss evaluated through CT/MRI and electrically evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR). Methods: We conducted a systematic review (1990–2023), identifying 59 published cases of which 24 were bilateral. The mean age at diagnosis was 10.34 years, and 25 cases presented additional inner ear malformations. Only seven patients underwent cochlear implantation, and EABR was performed in four cases. Outcomes of cochlear implantation were heterogeneous. Discussion: In our case, EABR showed a reproducible wave V on the right side, supporting candidacy for cochlear implantation which led to positive early auditory responses. Conclusions: This case and review highlight the role of EABR in identifying residual cochlear nerve functionality and guiding candidacy for cochlear implantation in narrow duplicated IAC.

1. Introduction

Congenital hearing loss affects approximately one in every thousand live births, with inner ear malformations present in up to 20% of sensorineural cases and internal auditory canal (IAC) abnormalities accounting for about 12% of congenital temporal bone anomalies [1,2,3].

The IAC is considered narrow when its diameter is <2 mm on high-resolution CT (HRCT); this compares to a typical diameter of around 4 mm (range 2–8 mm) [2,3,4,5].

Narrow duplication of the IAC (DIAC) is a particularly rare variant, defined by two bony canals separated by a complete or incomplete septum, typically with the facial nerve in the anterosuperior canal and a common vestibulocochlear trunk in the posteroinferior canal; in addition, the cochlear nerve is often hypoplastic or aplastic [2,3,5,6]. The condition may be unilateral or bilateral, can co-occur with other inner ear anomalies or systemic syndromes, has an estimated occurrence rate of ~0.019% in radiologic series, and was first described by Weissman et al. in 1991 [2,4,7].

Historically, narrow IAC (or DIAC) has been viewed as a relative contraindication to cochlear implantation (CI) due to uncertain cochlear nerve integrity and variable speech outcomes, though successful cases have been documented [8,9,10,11]. Complementary testing such as electrically evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR) can help determine residual cochlear nerve functionality and guide candidacy when imaging is inconclusive [10,11].

Despite scattered case reports and small series, clinicians face limited, heterogeneous evidence to guide CI candidacy and prognostication in DIAC—particularly in bilateral cases—and imaging alone may under-detect residual nerve fibers [2,4,8,10,11].

We present here a rare bilateral DIAC case evaluated with CT/MRI and EABR. We synthesize published evidence (1990–2023) to clarify candidacy criteria and expected outcomes, emphasizing the decision pathway from functional testing to implantation.

2. Case Presentation

A one-year-old girl was referred to our tertiary referral center for further evaluation of bilateral congenital hearing loss previously diagnosed at another hospital. None of the risk factors for hearing loss specified in the JCHI 2019 guidelines were reported [12]. At birth, the child failed the neonatal hearing screening and subsequently underwent a complete audiological evaluation, including auditory brainstem response (ABR), play audiometry, and tympanometry, which confirmed bilateral profound hearing loss. Otoscopic examination was normal, growth parameters were within normal limits, facial nerve function was intact, and no additional clinical abnormalities were observed.

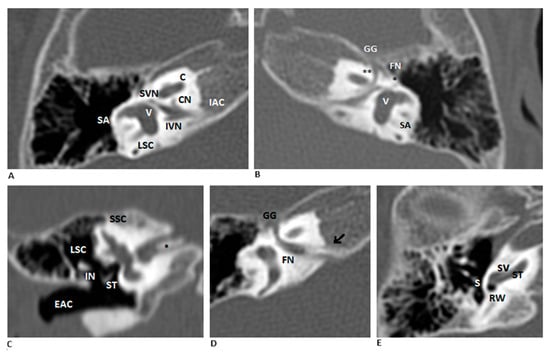

High-resolution CT and MRI revealed a duplicated appearance of the internal auditory canal (IAC) with normal cochlear and vestibular structures. The two canals were separated by a bony septum, delineating an anterosuperior facial nerve canal and a posteroinferior vestibulocochlear nerve canal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bilateral DIAC in CT scan. (A,B) Coronal HRCT images of the right and left ears show a bony septum dividing the IAC into an anterosuperior facial nerve canal and a posteroinferior vestibulocochlear nerve canal. Relevant structures include the facial nerve (FN, ** labyrinthine segment, * tympanic segment), cochlear nerve (CN), inferior vestibular nerve (IVN), and superior vestibular nerve (SVN). (C–E) Right ear details show the bony septum (* in figure C, arrow in figure D), a normal middle ear and external auditory canal (EAC), and a cochlea with normal morphology. Abbreviations: SA—subarcuate artery; V—vestibule; LSC—lateral semicircular canal; GG—geniculate ganglion; SSC—superior semicircular canal; ST—stapes; IN—incus; RW—round window; SV—scala vestibuli; ST—scala tympani.

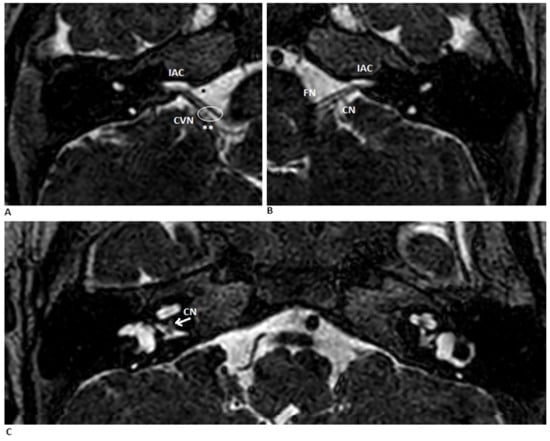

MRI demonstrated a normal facial nerve in the anterosuperior compartment and a common vestibulocochlear trunk dividing into three branches—one toward the cochlea and two toward the vestibule. The cochlear branch appeared markedly thin, consistent with cochlear nerve hypoplasia (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MR scan of the cerebellopontine angle. (A,B) Coronal T2-weighted MRIs of the right and left ears show a normal porus acousticus (**), the FN (*) and bilaterally narrow internal auditory canals (IAC). (C) Axial view shows bilateral hypoplastic vestibulocochlear nerves (CVN). The arrow the point where the cochlear portion of the CN branches off from the vestibular portion. Abbreviations: FN—facial nerve; CN—cochlear nerve.

The cochlear nerve measured 0.6 mm on the right side and 1 mm on the left. Inner ear structures were otherwise normal. Despite adequate hearing-aid fitting, auditory and speech perception remained poor, preventing age-appropriate language development. Therefore, an electrically evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR) was performed to guide further auditory rehabilitation and assess candidacy for cochlear implantation.

EABR testing was performed under general anesthesia without neuromuscular blockade. A tympanomeatal flap was created via an endoscopic approach, and a “hockey-stick’’ electrode was positioned in the round window niche (©MED-EL, Innsbruck, Austria). Biphasic electrical stimuli (100 µs) were delivered at current levels ranging from 200 to 1000 CU. Based on a pre-operative OTOPLAN® analysis (3D reconstruction of the patient’s CT/MRI data provided by MED-EL), a FLEX 28 electrode array was selected as the most suitable option for cochlear anatomy and predicted insertion depth. The electrode was inserted through the round window without any technical difficulties.

On the left side, no reproducible waves were detected even at maximal stimulation, although facial nerve activation and stapedius reflex were observed. On the right side, a clear and reproducible wave V was identified at 600 CU and at 800 CU, with increasing amplitude and decreasing latency at higher stimulation levels, indicating the presence of residual and stimulable cochlear nerve fibers.

Although narrow and duplicated IAC has traditionally been considered a relative contraindication to cochlear implantation [8,9,10,11], the combination of (1) MRI evidence of a hypoplastic but present cochlear nerve and (2) a positive, reproducible EABR response on the right side provided strong functional confirmation of neural viability. Thus, cochlear implantation was considered appropriate on the right side despite the anatomic abnormality.

The patient subsequently underwent right-sided cochlear implantation through a transmastoid approach to the round window. No postoperative complications occurred. At activation, she exhibited no facial nerve stimulation, tolerated the device well, and demonstrated good early auditory responses. She was enrolled in routine audiological follow-up and a structured speech therapy rehabilitation program.

Following activation, the patient showed an initial auditory improvement consistent with appropriate device function and preserved cochlear nerve responsiveness. Clinically, this was reflected by clearer behavioral reactions to environmental acoustic stimuli and an emerging ability to detect simple vocal cues. Although long-term outcomes will require continued follow-up, these early observations support the functional relevance of the residual cochlear nerve activity demonstrated by the EABR.

3. Literature Synthesis and Comparative Analysis

3.1. Methodology

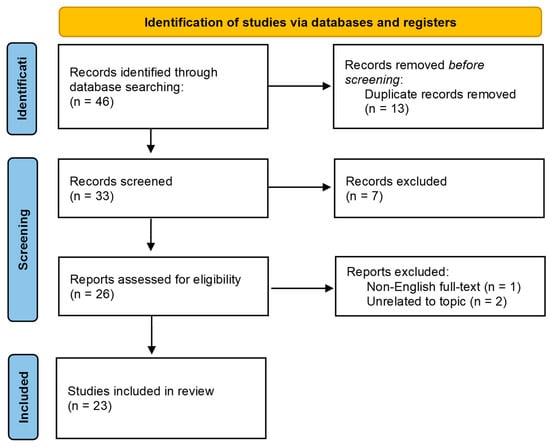

A systematic review (PubMed; 1990–2023) was carried out following PRISMA guidelines using the queries: “internal auditory canal duplication” AND “cochlear implants”/“radiology”/“syndromes”. Inclusion: English-language reports of unilateral/bilateral narrow DIAC with or without CI. Exclusion: non-English, unavailable abstract/full-text, narrow IAC without duplication. Screening progressed from abstracts to full texts [13] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

3.2. Results

A total of 46 articles were initially identified. Thirteen duplicate records were removed. Of the remaining thirty-three abstracts screened, seven were excluded (one without an abstract, and six unrelated to the topic). Full-text analysis was performed for the remaining twenty-six papers, resulting in the exclusion of three articles (one non-English and two unrelated). Ultimately, 23 articles met the inclusion criteria.

In a second screening, we analyzed the full texts of the remaining twenty-six papers, excluding one article written in a language other than English and two articles unrelated to our topic. Finally, a total of 23 articles were included in our study. An overview of the results is shown in Table 1; the complete study-level data are available in Appendix A, Table A1.

Table 1.

Results of the literature review—summary.

Across the 59 reported cases, 24 presented with bilateral and 34 with unilateral IAC duplication. The mean age at diagnosis was 10.34 years (range: 2 months–80 years). Only four cases of facial palsy associated with DIAC have been reported in the literature [2,14,15,16].

Most patients exhibited profound sensorineural hearing loss. Additional inner ear malformations were present in twenty-five patients, and five had associated syndromes such as Goldenhar [17] or Klippel–Feil [5], while six were diagnosed with pontine tegmental cap dysplasia (PTCD) [15,18,19,20].

EABR was performed in only four cases to assess residual cochlear nerve function [9,10,19]. Cochlear implantation was performed in seven patients, including three who underwent bilateral implantation [10,11,17,20,21,22].

Two patients were managed with hearing aids [1,23], two did not use hearing aids or other devices [1,14], one was treated with a bone-conductive device [5], and two were considered candidates for either cochlear implantation or bone-conductive devices [4]. No rehabilitation data were available for 45 patients, and none underwent auditory brainstem implantation (ABI).

Across DIAC cases, the cochlear nerve is frequently hypoplastic or aplastic, and ABR/OAE testing is typically absent in cases of profound hearing loss [1,2,10]. Imaging plays a crucial role—CT for assessing bony anatomy, and MRI for nerve visualization; however, residual nerve fibers may remain uncertain on MRI alone, particularly in rare DIAC cases where misclassification as “narrow IAC” is possible [1,2,4,8,23,24].

4. Discussion

The incidence of congenital hearing loss is estimated to be one per thousand live births. Genetic causes could be associated in up to 50% of cases and in 20% of SNHL cases. Duplicated internal auditory canal (DIAC) is an uncommon congenital anomaly, and its true prevalence remains uncertain. The first description of a narrow duplicated IAC was provided by Weissman et al. in 1991 [7]. Since then, both isolated forms and cases associated with additional inner ear malformations or syndromes have been reported. [1,2,3,10,11,15,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Conditions such as Goldenhar syndrome [17], Klippel–Feil [5], and pontine tegmental cap dysplasia (PTCD) [15,18,19,28] have been described in association with DIAC, reflecting the heterogeneity of its developmental spectrum. In our systematic review, 59 cases of duplicated IAC were identified [2,4], with an occurrence rate previously estimated at approximately 0.019% [2]. Most cases are unilateral [1,2,3,5,26,28,32] whereas bilateral DIAC, such as in our patient, remains relatively rare.

Radiological evaluation plays an essential role in the diagnosis of congenital hearing loss and in identifying the presence and caliber of the cochlear nerve. CT provides crucial information on bony anatomy, while MRI allows assessment of the cochlear nerve and its degree of hypoplasia or aplasia [1,2,4,8,23,24]. However, nerve fibers may be difficult to visualize when extremely thin, and DIAC itself can be misinterpreted radiologically as a simple narrow IAC [2], underscoring the limitations of imaging alone. The cochlear nerve is frequently hypoplastic or aplastic in DIAC [1,2,10], and this explains why many affected patients present with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss and absent ABR and OAE responses.

Historically, narrow IAC has been considered a relative contraindication to cochlear implantation due to the uncertain presence of a functional cochlear nerve and the associated risk of poor speech-perception outcomes [8,9,10,32]. Earlier reports described several implantation failures in patients with narrow or duplicated IAC [30]. However, growing evidence demonstrates that meaningful auditory improvement is possible in selected candidates. Positive outcomes—including improved CAP scores, enhanced Ling sound detection, and development of spontaneous verbalization—have been documented in children undergoing CI, particularly when functional testing confirms residual nerve activity [10,11,21,22,28,33]. Binnetoglu et al. [18], for example, described improvements in speech perception following unilateral CI, supported by transtympanic EABR demonstrating neural responsiveness.

These heterogeneous outcomes reflect the wide variability in neural anatomy, associated malformations, and functional nerve integrity seen in DIAC. When the cochlear nerve is aplastic, auditory outcomes after CI are predictably poor; conversely, hypoplastic but present nerve fibers can support transmission of electrically evoked responses, enabling functional benefit [1,2,10]. Variability is further amplified by the presence of additional inner ear malformations, syndromic diagnoses, or central nervous system anomalies, all of which may compromise the auditory pathway [1,2,3,10,11,15,20,22,23,24,30]. Differences in age at implantation and timing of habilitation also contribute to diverse outcomes across the literature [10,11].

Among the available tools, EABR emerges as a key predictor of outcome, as it provides direct physiological confirmation of cochlear nerve stimulability. A reproducible wave V with increased current-dependent amplitude and decreased latency indicates the presence of functional fibers capable of responding to electrical stimulation [10,11]. When MRI shows a very thin nerve—as frequently occurs in DIAC—EABR can differentiate between nonfunctional aplasia and stimulable hypoplasia. Advanced MRI sequences with <1 mm resolution, such as MP-RAGE, B-FFE, FT-CISS, and 3D DRIVE, can further enhance visualization of the nerve, but still cannot replace the functional information provided by EABR [4,5,10,11,26].

Our case illustrates how this integrated approach improves clinical decision-making. The patient had bilateral DIAC with profound SNHL, but cochlear and vestibular morphology was preserved. Although MRI revealed marked cochlear nerve hypoplasia, residual nerve presence could not be reliably assessed. The right-sided positive EABR response—showing a clear, reproducible wave V—provided crucial confirmation of neural viability, and this justified cochlear implantation despite the traditionally unfavorable anatomy. The successful early auditory responses observed postoperatively align with the subset of DIAC cases in the literature where functional testing predicted good outcomes [10,11,18,28,33]. This connection underscores the clinical relevance and novelty of our case, demonstrating that DIAC should not be considered an absolute contraindication for CI when functional nerve integrity is demonstrated.

Overall, the literature and our findings highlight the necessity of combining radiologic and functional assessment to optimize candidacy decisions in DIAC. Reliance on imaging alone risks underestimating the presence of stimulable nerve fibers, whereas EABR offers objective confirmation when nerve morphology is ambiguous. As the number of reported DIAC cases remains limited, further long-term studies and multicenter datasets are needed to better characterize auditory outcomes and refine candidacy criteria for this rare malformation.

5. Conclusions

Narrow duplicated internal auditory canal (DIAC) is a rare congenital malformation typically associated with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss. It occurs more often unilaterally than bilaterally, and it may present either as an isolated anomaly or in association with additional inner ear malformations or syndromic conditions. In most cases, the cochlear nerve is either hypoplastic or aplastic, making accurate assessment of neural integrity essential for determining auditory rehabilitation options.

High-resolution CT and MRI remain fundamental for anatomical evaluation; however, imaging alone may be insufficient to determine the functional viability of the cochlear nerve. In this context, electrically evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR) provides crucial complementary information by identifying the presence of stimulable neural fibers—an essential predictor of potential benefit from cochlear implantation. When imaging findings are ambiguous, EABR can help distinguish between nerve aplasia and severe hypoplasia, thereby refining patient selection.

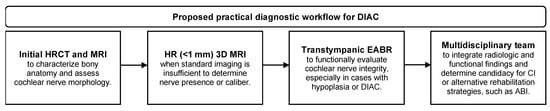

Based on the available evidence and clinical experience, the following practical diagnostic workflow can be recommended: (1) initial assessment with HRCT to define bony anatomy and MRI to evaluate the cochlear nerve; (2) advanced 3D MRI sequences (<1 mm) to enhance nerve visualization when standard imaging is inconclusive; (3) transtympanic EABR to functionally assess cochlear nerve integrity, particularly in cases with radiologic hypoplasia or duplicated IAC; (4) shared decision-making within a multidisciplinary team, including otologic surgeons, radiologists, pediatricians, and audiologists, to interpret findings and determine candidacy for cochlear implantation or alternative options such as auditory brainstem implantation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed practical diagnostic workflow.

Despite the expanding number of reported cases, the total population of DIAC patients remains small, and long-term auditory outcomes after cochlear implantation are still heterogeneous. Continued follow-up is essential to evaluate speech perception development and functional benefit over time.

Future efforts should focus on creating multi-center registries and prospectively designed studies to systematically collect data on diagnostic findings, EABR parameters, surgical outcomes, and long-term auditory development in DIAC. Standardized reporting of imaging features, nerve measurements, functional testing, and rehabilitation outcomes would help refine prognostic indicators and support the development of evidence-based guidelines for CI candidacy in this rare anatomical condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L. and D.S.; methodology, E.L. and D.S.; software, M.P.; validation, D.S., E.G. and D.M.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, E.L. and D.S.; resources, E.L. and D.S.; data curation, D.S. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, M.P. and D.S.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, D.S., E.G. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was not required for the case report because it was retrospective and based exclusively on anonymized data obtained from routine clinical practice, with no additional procedures or interactions performed for research purposes. Ethical approval was not required for the systematic review, as it involved only analysis of previously published studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Complete Dataset of Included Studies (Table A1).

Table A1.

Results of the literature review.

Table A1.

Results of the literature review.

| Study | Sex | Age | Side of the Malformation | VIII Nerve | VII Nerve | Cochlea | Hearing | Associated Anomalies | Implantation | Facial Palsy | EABR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takanashi et al. [1] | M | 7 yr | Left | Absent | Present | Only basal turn of the cochlea | Bilateral severe SNHL | Vestibule enlargement, absence of superior and lateral SCCs | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| F | 10 mo | Bilateral | Hypoplastic | Present | Cochlear hypoplasia | Bilateral profound SNHL | Altered SCCs | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Wang et al. [2] | M | 23 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| F | 80 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| M | 4 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 6 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 6 yr | Left | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 4 m | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | Microtia, EAC atresia | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 8 yr | Left | Dysplastic | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Moderate SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 15 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Severe SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 5 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| M | 11 y | Left | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 2 yr | Left | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Severe SNHL | Microtia, EAC atresia | n.s. | + | n.s. | |

| M | 13 yr | Left | Absent | Present | Inner ear malformation associated | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Ferreira et al. [3] | F | 50 yr | Right | Hypoplastic | Present | Bilateral, dysplastic cochlea | Profound SNHL | Bilateral vestibule and lateral SCC enlargement, bilateral microtia | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| AlEnazi et al. [4] | M | 6 yr | Left | Present | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| F | 10 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Demir et al. [5] | M | 7 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral severe CHL | Klippel–Feil syndrome | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Weissman et al. [7] | M | 45 yr | Left | Absent | Present | Normal | Severe SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Lee et al. [8] | F | 2 mo | Right | no MRI | No MRI | Normal | Severe SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| M | 9 yr | Right | no MRI | No MRI | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| M | 7 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Severe SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Thompson et al. [10] | F | 6 mo | Bilateral | Right hypoplastic, left absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Dysplastic lateral SCCs, motor delay | Bilateral IC | - | Present |

| M | 8 mo | Bilateral | Right absent, left present | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Motor and developmental delay, horseshoe kidney, dysplastic SCCs | Bilateral IC | - | Present | |

| Kishimoto et al. [11] | F | 11 mo | Bilateral | Present | Present | Modiolar deficiency, absence of interscalar septum, cochlea with cystic apex | Bilateral profound SNHL | Dysplastic SCCs, mental retardation, vesicoureteral reflux | Right IC | - | Present |

| Gishing et al. [14] | F | 26 yr | Right | Present | Absent | Normal | Mild SNHL | - | n.s. | + | n.s. |

| Vinceti et al. [15] | F | 9 yr | Right | Hypoplastic | Present | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| F | 1 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 6 mo | Bilateral | Absent | Absent | Bilateral, dysplastic cochlea with modiolar deficiency and cystic apex | Bilateral profound SNHL | Ectasic vestibule, EVA, PTCD | n.s. | + | n.s. | |

| Kew et al. [16] | M | 34 yr | Right | Absent | Absent | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | + | n.s. |

| Gupta et al. [17] | F | 2 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Goldenhar syndrome, right microtia, right emifacial microsomia, right torticollis, stenotic right EAC | Left IC | - | n.s. |

| Chan et al. [18] | M | 9 mo | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Profound SNHL | PTCD | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Nixon et al. [19] | F | 2 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | PTCD | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| M | 6 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 2 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 2 mo | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 2 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | IP-2 | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| M | 10 mo | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 6 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Bilateral | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Right | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Left | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| n.s. | n.s. | Left | Absent | Present | n.s. | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Desai et al. [20] | M | 6 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | PTCD, developmental delay | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| F | 4 mo | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Dysplastic cochlea | Bilateral profound SNHL | PTCD, developmental delay, microcephaly | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| F | 13 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Dysplastic cochlea | Bilateral profound SNHL | PTCD, microcephaly | Bilateral IC | - | Right dubious response | |

| Binnetoglu [21] | F | 13 mo | Bilateral | Right hypoplastic, left absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | Right IC | - | Right present |

| Manchanda et al. [22] | M | 4 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | IP1 | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| M | 6 yr | Bilateral | Left hypoplastic, right absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Aplastic lateral SCCs | Left IC | - | n.s. | |

| M | 14 mo | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Left microphthalmos | n.s. | - | n.s. | |

| Coelho et al. [23] | M | 14 yr | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Cochlear dysplasia | Bilateral profound SNHL | Vestibular dysplasia | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Kesser et al. [25] | F | 5 mo | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Baik et al. [26] | F | 6 yr | Right | Absent | Present | Normal | Profound SNHL | - | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Weon et al. [27] | M | 2 y | Bilateral | Absent | Present | Normal | Bilateral profound SNHL | Right microtia, slightly stenotic EAC | n.s. | - | n.s. |

| Gotkas Bakar et al. [30] | F | 9 yr | Bilateral | No MRI | No MRI | Mondini dysplasia | Bilateral profound SNHL | EVA, cystic vestibule, hypoplasia of lateral SCCs | n.s. | - | n.s. |

Abbreviations: n.s.—not specified; SNHL—sensorineural hearing loss; PTCD—pontine tegmental cap dysplasia; EAC—external auditory canal; SCC—semicircular canal; EVA—enlarged vestibular aqueduct; IP1—incomplete partition type 1; CI—cochlear implantation.

References

- Takanashi, Y.; Kawase, T.; Tatewaki, Y.; Suzuki, J.; Yahata, I.; Nomura, Y.; Oda, K.; Miyazaki, H.; Katori, Y. Duplicated internal auditory canal with inner ear malformation: Case report and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx 2018, 45, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, X. Duplicated Internal Auditory Canal: High-Resolution CT and MRI Findings. Korean J. Radiol. 2019, 20, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Shayestehfar, B.; Lufkin, R. Narrow, duplicated internal auditory canal. Neuroradiology 2003, 45, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlEnazi, A.S.; Alshaiji, A.; Alenezi, M.; Al-Sharydah, A.; Alsuhibani, S.; Alhaidey, A.; Samarah, A.; AlQahtani, M. De novo sensorineural hearing loss sequelae of narrow, duplicated internal auditory canal: Case series and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 95, 107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, O.I.; Cakmakci, H.; Erdag, T.K.; Men, S. Narrow duplicated internal auditory canal: Radiological findings and review of the literature. Pediatr. Radiol. 2005, 35, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Israrahmed, A.; Akhter, J.; Lal, H. Duplicated internal auditory canal with dysplastic ossicles and microtia: Role of high-resolution CT and MRI. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e243825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, J.L.; Arriaga, M.; Curtin, H.D.; Hirsch, B. Duplication anomaly of the internal auditory canal. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1991, 12, 867–869. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Cha, S.H.; Jeon, M.H.; Bae, I.H.; Han, G.S.; Kim, S.J.; Park, K.S. Narrow duplicated or triplicated internal auditory canal (3 cases and review of literature): Can we regard the separated narrow internal auditory canal as the presence of vestibulocochlear nerve fibers? J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2009, 33, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, T.; Mathur, N.N.; Savy, L.; Graham, J.M. Is there a functioning vestibulocochlear nerve? Cochlear implantation in a child with symmetrical auditory findings but asymmetric imaging. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2001, 57, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.R.; Birman, C.S. Bilateral duplication of the internal auditory canals and bilateral cochlear implant outcomes and review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 119, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, I.; Moroto, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Harada, H.; Kikuchi, M.; Suehiro, A.; Shinohara, S.; Naito, Y. Bilateral duplication of the internal auditory canal: A case with successful cochlear implantation. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics; Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. J. Early Hear. Detect. Interv. 2019, 4, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghising, R.; Dongol, K.; Suwal, S. Internal auditory canal duplication with facial and cochlear nerve dysfunction: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2023, 11, 2050313X231220812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenti, V.; Ormitti, F.; Ventura, E. Partitioned versus duplicated internal auditory canal: When appropriate terminology matters. Otol. Neurotol. 2014, 35, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, T.Y.; Abdullah, A. Duplicate internal auditory canals with facial and vestibulocochlear nerve dysfunction. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2012, 126, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Samdani, S.; Vaishnav, J.K.; Singh, Y.; Grover, M. Cochlear Implantation in Goldenhar Syndrome. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 74, 4159–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.; Veltkamp, D.L.; Desai, N.K.; Pfeifer, C.M. Pontine tegmental cap dysplasia with a duplicated internal auditory canal. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.N.; Dempsey, J.C.; Doherty, D.; Ishak, G.E. Temporal bone and cranial nerve findings in pontine tegmental cap dysplasia. Neuroradiology 2016, 58, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.K.; Young, L.; Miranda, M.A.; Kutz, J.W., Jr.; Roland, P.S.; Booth, T.N. Pontine tegmental cap dysplasia: The neurotologic perspective. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnetoğlu, A.; Bağlam, T.; Sarı, M.; Gündoğdu, Y.; Batman, Ç. A Challenge for Cochlear Implantation: Duplicated Internal Auditory Canal. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2016, 12, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, S.; Bhalla, A.S.; Kumar, R.; Kairo, A.K. Duplication Anomalies of the Internal Auditory Canal: Varied Spectrum. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 71, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, L.O.; Ono, S.E.; Neto, A.C.; Polanski, J.F.; Buschle, M. Bilateral narrow duplication of the internal auditory canal. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2010, 124, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, T.; Kuwashima, S.; Arakawa, H.; Yamazaki, E.; Kitajima, K.; Ejima, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Kaji, Y. Narrow duplicated internal auditory canal: A rare inner ear malformation with sensorineural hearing loss. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009, 135, 1048–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesser, B.W.; Raghavan, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Carfrae, M.; Essig, G.; Hashisaki, G.T. Duplication of the internal auditory canal: Radiographic imaging case of the month. Otol. Neurotol. 2010, 31, 1352–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baik, H.W.; Yu, H.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, G.H. A narrow internal auditory canal with duplication in a patient with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Korean J. Radiol. 2008, 9, S22–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weon, Y.C.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.K.; Koo, J.W. Bilateral duplication of the internal auditory canal. Pediatr. Radiol. 2007, 37, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, J.W.; Offeciers, F.E.; Govaerts, P.J.; Kuhweide, R.; Geldof, H.; Somers, T.; D’Hont, G. Aplasia and hypoplasia of the vestibulocochlear nerve: Diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 1997, 202, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilain, J.; Pigeolet, Y.; Casselman, J.W. Narrow and vacant internal auditory canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Belg. 1999, 53, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Goktas Bakar, T.; Karadag, D.; Calisir, C.; Adapinar, B. Bilateral narrow duplicated internal auditory canal. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 265, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennaroğlu, L.; Tahir, E. A Novel Classification: Anomalous Routes of the Facial Nerve in Relation to Inner Ear Malformations. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E696–E703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.S.; Na, D.G.; Jung, J.Y.; Hong, S.H. Narrow internal auditory canal syndrome: Parasaggital reconstruction. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2000, 114, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, A.P.; Mason, S.M.; O’Donoghue, G.M. Cochlear nerve aplasia: Its importance in cochlear implantation. Am. J. Otol. 1999, 20, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.