Abstract

In this study, TiB2/AlSi10Mg, 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg, and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite powders were prepared via high-energy ball milling. For the first time, TiB2 and SiC hybrid particle-reinforced aluminum matrix composites (AMCs) were fabricated using the Laser-Directed Energy Deposition (LDED) technique. The effects of processing parameters on the microstructure evolution and mechanical properties were systematically investigated. Using areal energy density as the main variable, the experiments combined microstructural characterization and mechanical testing to elucidate the underlying strengthening and failure mechanisms. The results indicate that both 2 wt.% and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites exhibit excellent formability, achieving a relative density of 98.9%. However, the addition of 5 wt.% SiC leads to the formation of brittle Al4C3 and TiC phases within the matrix. Compared with the LDED-fabricated AlSi10Mg alloy, the tensile strength of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite increased by 21.4%. In contrast, the tensile strengths of the 2 wt.% and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites decreased by 3.7% and 2.6%, respectively, mainly due to SiC particle agglomeration and the consumption of TiB2 particles caused by TiC formation. Nevertheless, their elastic moduli were enhanced by 9% and 16.3%, respectively. Fracture analysis revealed that the composites predominantly exhibited ductile fracture characteristics. However, pores larger than 10 μm and SiC/TiB2 clusters acted as crack initiation sites, inducing stress concentration and promoting the propagation of secondary cracks.

1. Introduction

As a revolutionary processing technology, Additive Manufacturing (AM) has attracted extensive attention in recent years. Among its various techniques, Laser-Directed Energy Deposition has demonstrated great potential in the fabrication of metal matrix composites (MMCs) due to its advantages of producing large-scale components and enabling flexible forming [1,2,3]. Through the layer-by-layer deposition process and precise control of processing parameters, researchers are able not only to fabricate complex structures but also to endow materials with superior mechanical and functional properties, thereby meeting the urgent demand for lightweight and high-strength materials in aerospace, automotive, and other advanced engineering fields [4,5,6].

MMCs and AMCs have garnered significant attention owing to their low density, high specific strength, and good plasticity [7,8]. In particular, AlSi10Mg is frequently used as a matrix material for AMCs fabricated via additive manufacturing because of its excellent thermal conductivity, which helps to reduce thermal stresses during processing [9]. However, it remains challenging for AlSi10Mg to simultaneously achieve high strength, ductility, and stiffness. Specifically, its low elastic modulus (~70 GPa) limits its further engineering applications. To address this issue, researchers commonly introduce ceramic particles (such as SiC, TiC, or TiB2) into the AlSi10Mg matrix as reinforcing phases to enhance its overall properties. Previous studies have demonstrated that a moderate amount of single-particle reinforcement can effectively improve the strength, hardness, and wear resistance of the composite [10,11,12,13]. Nevertheless, when the particle content exceeds a certain threshold (typically around 20 wt.%), the densification and property stability of the material deteriorate significantly [14,15]. Therefore, the strengthening effect of single-particle reinforcement remains inherently limited.

To overcome this limitation, hybrid particle reinforcement has emerged as an effective solution. By introducing two or more types of reinforcing particles into the AlSi10Mg matrix, a synergistic strengthening effect can be achieved, leading to superior overall performance [16,17]. For instance, a study [18] reported that the (1.5 wt.% TiB2 + 1.5 wt.% TiC)/AlSi10Mg composite powder prepared via ball milling exhibited a tensile strength of 552.4 MPa and an elongation of 12.0%, which were markedly higher than those of 3.4 wt.% TiB2/AlSi10Mg [19] and 5.0 wt.% TiC/AlSi10Mg [18] composites. Furthermore, another work [20] utilized 6.5 wt.% TiB2/AlSi10Mg pre-alloyed powder as the base material and mechanically mixed it with varying contents of SiC particles (5 vol.% and 10 vol.%). The resulting dual-phase aluminum matrix composites, fabricated via Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF), exhibited significant improvements in ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, and elastic modulus, demonstrating the remarkable potential of hybrid particle reinforcement in tailoring the mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg-based composites.

Compared with the LPBF process, LDED exhibits fundamental differences in powder feeding, solidification behavior, and particle redistribution mechanisms, all of which significantly influence the microstructural evolution and mechanical performance of the resulting composites. LPBF is characterized by extremely high cooling rates (105–106 K/s) and a small melt-pool volume, which readily promotes the formation of ultrafine cellular/dendritic structures and enables rapid solid-solution of alloying elements. However, because the powders are pre-mixed, the type and content of reinforcement particles cannot be dynamically adjusted during processing. In contrast, LDED operates at lower cooling rates (103–104 K/s) and features intense melt-pool convection, with the thermal gradient generally aligned with the deposition direction, which facilitates particle transport, heterogeneous nucleation, and compositional redistribution [1,2,3]. Moreover, unlike “real-time powder mixing,” which mixes multiple reinforcements within a single feeding channel, LDED enables independent multi-channel powder feeding and on-the-fly adjustment of particle ratios, allowing the fabrication of functionally graded structures and tailoring of local material properties.

Although previous studies have reported the strengthening effects of TiB2- or SiC-reinforced AlSi10Mg composites fabricated by LPBF [21], no work to date has systematically evaluated the synergistic–competitive interfacial reactions (e.g., TiC and Al4C3 formation) between the two reinforcements under LDED conditions or their influence on microstructural and mechanical evolution. Based on this objective, TiB2/AlSi10Mg, 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg, and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite powders were selected as feedstock materials for LDED fabrication experiments. By adjusting the areal energy density, this study systematically investigates the forming behavior of particle-reinforced AlSi10Mg composites under LDED conditions. At the macro- and microstructural levels, particular attention is given to the melt pool morphology, dual-particle distribution characteristics, reaction-induced precipitates, and grain evolution behavior. From the mechanical perspective, the synergistic effects of dual-particle reinforcement and the influence of grain morphology on the mechanical performance are analyzed, and the corresponding fracture and failure mechanisms are elucidated. The findings of this work provide valuable insights for optimizing LDED process parameters and enhancing the performance of composite materials, thereby laying a solid foundation for the efficient fabrication of functional structural components.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The powders used in this study include TiB2/AlSi10Mg pre-alloyed powder and β-SiC powder. The TiB2/AlSi10Mg pre-alloyed powder was prepared using a mixed-salt reaction method combined with vacuum gas atomization, and its chemical composition is listed in Table 1, with a TiB2 particle content of approximately 6.5 wt.%. The β-SiC powder was synthesized by mixing high-purity silicon and carbon powders in a specific ratio, followed by a chemical reaction at temperatures above 2000 °C, producing β-SiC particles with a defined crystal structure and particle size distribution. The corresponding chemical composition is also provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical Compositions of TiB2/AlSi10Mg and β-SiC Powders (wt.%).

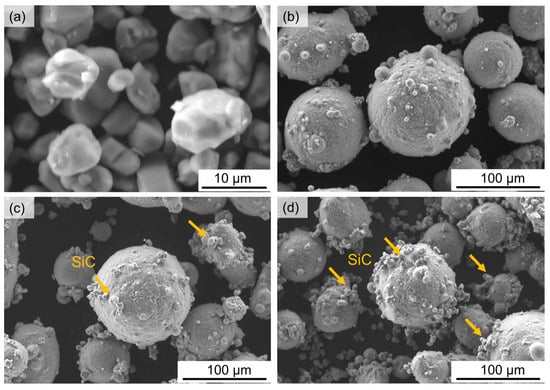

SiC and pre-alloyed TiB2/AlSi10Mg powders were mixed using an ND8 omnidirectional planetary ball mill at a rotation speed of 100 rpm, with a ball-to-powder weight ratio of 1:3. The milling jar and milling balls were made of agate, and the ball milling was conducted for 4 h without atmosphere protection and without any intermittent pauses. To avoid contamination, the jar and milling media were ultrasonically cleaned with ethanol prior to use and kept sealed throughout the milling process to prevent oxidation and the introduction of external impurities. Before mixing, both powders were dried in a vacuum oven at 120 °C for 4 h. The morphology of the mixed SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg powders was characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, ZEISS Sigma 300, Oberkochen, Germany), as shown in Figure 1. The results indicate that the powder surface is clean in the absence of SiC addition (Figure 1b); at a low SiC content (2 wt.%), the SiC particles are discretely distributed on the TiB2/AlSi10Mg powder surface (Figure 1c); and with increasing SiC content (5 wt.%), SiC particles become more uniformly distributed across the powder surface (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

(a) Morphology of β-SiC powder; (b) Morphology of TiB2/AlSi10Mg powder; (c) Morphology of 2 wt.% β-SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg powder; (d) Morphology of 5 wt.% β-SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg powder.

2.2. Experimental System

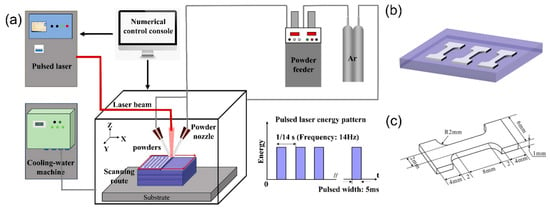

A 300 W Nd3+: YAG solid-state pulsed laser system was employed in this study to conduct deposition experiments on TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with varying SiC contents, as illustrated in Figure 2a. The substrate dimensions were 105 mm × 105 mm. The laser system had a maximum power output of 300 W, a wavelength of 1064 nm, a spot diameter of 1.2 mm, and an oxygen content ≤ 50 ppm within the chamber. Before performing the LDED experiments, the powders were loaded into a powder feeder, and an appropriate powder feeding rate was set. Subsequently, the laser spot and powder flow spot were precisely aligned (Table 2 and Table 3).

Figure 2.

(a) 300 W Nd3+:YAG solid-state pulsed laser forming system; (b) preparation of tensile specimens; (c) schematic diagram of the plate-type tensile specimen at room temperature.

Table 2.

Process parameters of LDED.

Table 3.

Laser power correspondence for LDED process parameters.

2.3. Material Characterization and Performance Testing

2.3.1. Powder Particle Size Analysis

A laser particle size analyzer (Winner2308B, Winner Particle Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to analyze the particle size distribution of powders with different compositions. The testing conditions were as follows: the wet method was employed, with water as the dispersion medium (refractive index of 1.33) and a circulation speed of 2400 rpm. The final particle size distribution results were obtained using the laser diffraction method in accordance with the GB/T 19077-2016 standard.

2.3.2. Metallurgical Quality Characterization

Based on the Archimedes drainage method, an electronic balance was used to measure the actual density of homogenized samples with different parameters and compositions. The theoretical density of TiB2/AlSi10Mg is 2.71 g/cm3, while that of SiC is 3.21 g/cm3 [20]. To quantitatively evaluate the metallurgical quality of the samples, the relative density (ρRD) was used as the evaluation metric. The relative density is defined as the ratio of the measured density to the theoretical density (ρTD). The calculation formula for the theoretical density of the SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite material is expressed as follows:

Here, ρ, ρRD and ρTD represent the actual density, relative density, and theoretical density, respectively. ρTiB2/AlSi10Mg and ρSiC denote the theoretical densities of TiB2/AlSi10Mg and SiC, while mTiB2/AlSi10Mg, mSiC correspond to their theoretical mass fractions.

2.3.3. Microstructural Characterization

An OLYMPUS GX71 (Tokyo, Japan) optical microscope was employed to observe the macroscopic morphology and metallurgical quality of the samples on cross-sections along the deposition direction. In addition, the surface microstructure and elemental distribution along the deposition direction were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The crystallographic information of the samples was analyzed through electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD).

The phase composition of the composites was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). During testing, a Cu target with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å was used, with an accelerating voltage of 50 kV and a current of 50 mA. The scanning range was set from 20° to 90°, and the scanning rate was 5°/min.

Furthermore, a transmission electron microscope (TEM) was employed to conduct detailed analyses of the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, utilizing bright-field (BF) imaging, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging, and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) modules.

2.3.4. Mechanical Property Testing

The microhardness of the SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites along the deposition surface was measured using a LECO microhardness tester (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MO, USA) under a load of 300 g and a dwell time of 13 s, with an indentation spacing of 700 μm. After process optimization, SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg hybrid specimens with dimensions of 30 mm × 15 mm × 6 mm were fabricated using the LDED technique for tensile testing.

Microhardness tests of the SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite were performed along the build direction using a LECO microhardness tester under a load of 300 g and a dwell time of 13 s, with a spacing of 700 μm between adjacent indents. After process optimization, SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg samples with dimensions of 30 mm × 15 mm × 6 mm were fabricated by LDED for tensile testing. Specimens were extracted from the locations indicated in Figure 2b. The samples were sectioned horizontally using wire cutting and then polished according to the tensile specimen geometry. The final tensile specimens were machined following the dimensions shown in Figure 2c. Tensile tests were conducted using a Shimadzu AGSX-10 kN universal testing machine (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an RVX-112B video extensometer (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA), with a strain rate of 1.0 × 10−4 s−1.

3. Results

3.1. Process Characteristics of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

Since porosity promotes the initiation and propagation of cracks and significantly reduces the mechanical properties of materials, densification is regarded as one of the key indicators for evaluating the quality of DED-fabricated parts [22].

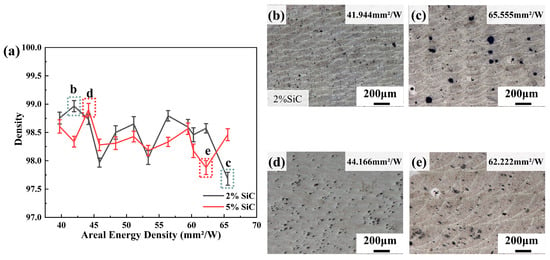

Figure 3a shows the variation in relative density of the two composite materials under different areal energy densities. The results indicate a nonlinear relationship between density and energy density, with an optimal energy density range observed for both composites. For the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, the maximum relative density (98.9%) was achieved at an areal energy density of 41.944 mm2/W. Similarly, the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite reached its highest relative density (98.9%) at 44.166 mm2/W. Based on these findings, subsequent fabrication experiments were conducted using these optimized energy density parameters.

Figure 3.

Variation in material density and optical micrographs under different areal energy densities. (a) Density variation curves under different areal energy densities; (b,c) 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite; (d,e) 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite.

Figure 3b presents the optical micrograph of the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite at an areal energy density of 41.944 mm2/W. Clearly visible irregular pores and well-defined melt pool boundaries can be observed, suggesting that the melt pool was stable under this energy input. In contrast, Figure 3c shows the same composite at a higher areal energy density of 65.555 mm2/W, where numerous large, nearly spherical pores appear densely distributed, and the melt pool boundaries become blurred. This indicates a significant enlargement of the heat-affected zone, likely caused by excessive energy input leading to over-melting, pore coalescence, or evaporation–solidification defects.

Figure 3d shows the optical micrograph of the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite at an areal energy density of 44.166 mm2/W, where noticeable pores are observed. As shown in Figure 3e, at a higher areal energy density of 62.222 mm2/W, both the number and size of pores increase significantly.

Overall, at low energy density, a larger number of pores is observed; as the energy density increases, the pore population decreases, and when the energy density becomes excessively high, the number of pores increases again.

3.2. Microstructural Evolution of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

3.2.1. Grain Morphology and Orientation Relationship of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

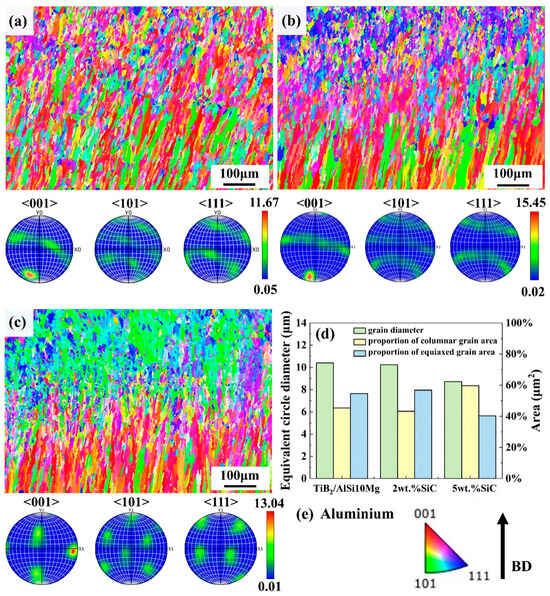

To further investigate the influence of different SiC particle contents on the grain morphology and grain size evolution of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites fabricated by LDED, EBSD characterization was conducted.

Figure 4 presents the microstructures of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with varying SiC contents on cross-sections perpendicular to the deposition direction. During the LDED process, since the temperature gradient is parallel to the deposition direction [23], columnar grains with an average size of 10.4 μm are formed, as shown in Figure 4a. A mixed structure of coarse columnar grains with minor equiaxed grains is observed, attributed to the heterogeneous nucleation sites provided by SiC particles during laser deposition. Additionally, particle agglomeration and thermal conductivity disturbance suppress the continuous growth of columnar grains. Further analysis reveals a pronounced <001> texture, with a maximum pole density of 11.67, indicating a strong fiber texture in the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite.

Figure 4.

EBSD IPF maps, pole figures, and grain size distributions of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents: (a) TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (b) 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (c) 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (d) grain size distribution; (e) aluminum.

With the addition of 2 wt.% SiC particles, as shown in Figure 4b, the microstructure of the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite remains dominated by coarse columnar grains accompanied by a small fraction of fine equiaxed grains, with grain sizes ranging from 4 to 101 μm. The grains exhibit a strong <001> preferred orientation, and the texture intensity in the <001> direction increases significantly, with the maximum pole density rising to 15.45.

When the SiC content increases to 5 wt.%, as shown in Figure 4c, the grain size ranges from 4 to 98 μm. According to the pole figure in Figure 4c, the columnar grain region maintains the <001> orientation, while regions dominated by equiaxed grains also appear. The coexistence of these two regions results in the overall pole figure shown in Figure 4c, with the maximum pole density decreasing to 13.04. This suggests that when the SiC content increases to 5 wt.%, particle agglomeration, excessive heterogeneous nucleation sites, and enhanced thermal disturbances interrupt the continuous orientation development of columnar grains, thereby reducing the texture intensity and promoting the formation of numerous equiaxed grains.

3.2.2. Solidification Microstructure and Particle Distribution Behavior of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

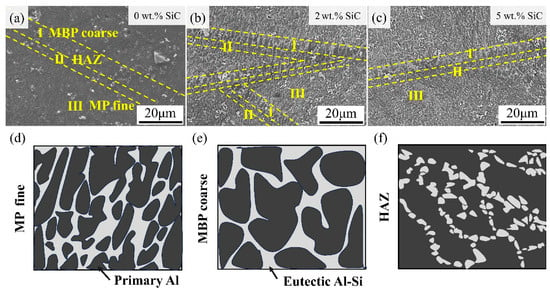

Figure 5 presents the SEM micrographs of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents. By comparing Figure 5a–c, it can be observed that the addition of SiC particles does not alter the inherent melt pool morphology of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite. The center region of the melt pool still exhibits a bright white fibrous network-like Al–Si eutectic structure, while the melt pool boundary contains partially coarse-grained regions and a heat-affected zone (HAZ). Within the HAZ, due to heat accumulation, the tightly bonded Al–Si eutectic structure is disrupted, transforming into discrete Si particles.

Figure 5.

SEM images of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents: (a) TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (b) 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (c) 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (d) schematic of MP fine; (e) schematic of MBP coarse; (f) schematic of HAZ.

The microstructure can generally be divided into three distinct regions: the fine-grained zone inside the melt pool (MP fine), the coarse-grained zone at the melt pool boundary (MP coarse), and the heat-affected zone (HAZ) [24]. The schematic illustrations of these three regions are shown in Figure 5d–f. In the melt pool center, fine grains are observed, whereas the melt pool boundary (MPB) consists of both coarse-grained and HAZ regions [25].

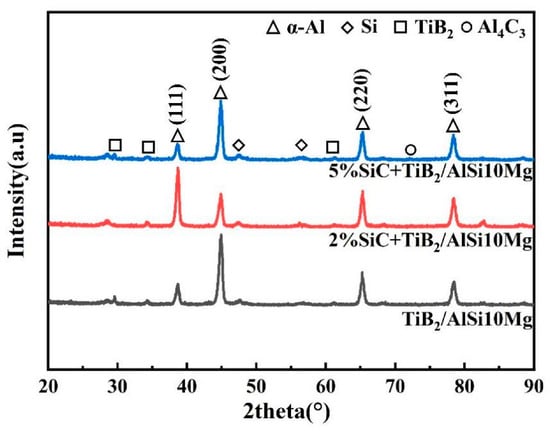

To identify the phase constituents of the composites and to analyze the influence of SiC content on interfacial reactions, XRD measurements were performed on samples fabricated with different SiC contents. The XRD patterns of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites containing various SiC additions are shown in Figure 6. All three samples exhibit diffraction peaks corresponding to face-centered cubic (FCC) α-Al, Si, and TiB2, indicating that the incorporation of reinforcement particles does not alter the primary crystal structure. Notably, in the sample containing 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg, additional diffraction peaks corresponding to Al4C3 are detected, suggesting that a reaction occurs between SiC particles and the Al matrix, leading to the formation of the brittle Al4C3 phase. Given that the melt pool temperature lies within the range of 923–1620 K during processing, the following reaction between Al and SiC is thermodynamically plausible:

4Al + 3SiC(s)→Al4C3(s) + 3Si

Figure 6.

XRD analyses of printed specimens of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents.

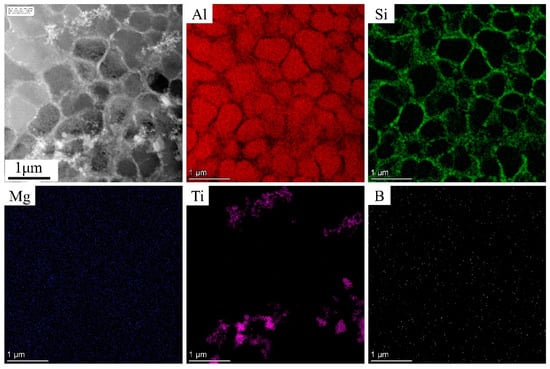

Figure 7 shows the elemental distribution of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite microstructure. The composite is primarily composed of a honeycomb-like α-Al phase (less than 1 μm) and a dendritic network of Al–Si eutectic structures. Analysis of the Si element clearly reveals that the Al–Si eutectic phase precipitates along the α-Al grain boundaries. The high cooling rate characteristic of the LDED process increases the solubility of Si in Al; however, during solidification, the excess Si is expelled into the liquid phase. As the remaining liquid continues to cool, additional Si is rejected toward the solidification front. Consequently, Si-rich eutectic regions form along the cellular boundaries, promoting the development of eutectic phases [26].

Figure 7.

Microstructural element distribution of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites.

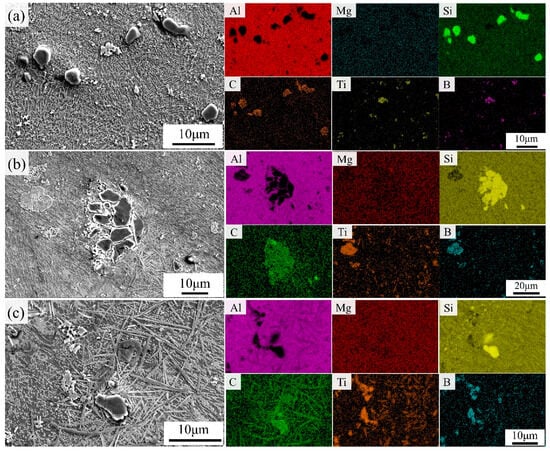

The morphology and distribution characteristics of SiC particles in SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different compositions were further investigated. Due to the similarity in distribution features, the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite was selected as a representative sample for analysis, and its EDS mapping results are presented in Figure 8. The SiC particles are relatively uniformly distributed within the composite (Figure 8a), although localized SiC-rich regions are observed (Figure 8b). This phenomenon is likely attributed to the long-term storage of the mixed powder in the powder feeder, which causes SiC particles to float on the surface of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg powder and subsequently agglomerate. When the agglomerated SiC powder interacts with the laser beam during deposition, Marangoni convection in the melt pool fails to adequately disperse the particles, ultimately leading to SiC particle agglomeration within the composite.

Figure 8.

5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg SEM and EDS images: (a) SiC dispersion; (b) SiC agglomerates; (c) needle-like phase.

Moreover, in the vicinity of agglomerated SiC particles, dark-contrast C-rich needle-like phases and bright-contrast Ti-rich needle-like phases were observed, interwoven in a cross-linked configuration, as shown in Figure 8c. It is preliminarily inferred that the formation of these two needle-like phases is related to the added SiC particles and the in situ formed TiB2 particles, with partial dissolution reactions occurring between the SiC/TiB2 particles and the Al matrix. The dark-contrast C-rich needle-like phase is presumed to be the Al4C3 phase, formed by the reaction between Al and SiC particles. As a brittle compound, Al4C3 can significantly reduce the service life of the material, promote early failure, and initiate cracks, thereby deteriorating the mechanical performance. According to literature reports, the bright-contrast Ti-rich needle-like phase is likely the TiC phase. However, the exact phase compositions still require further analytical and characterization confirmation [20].

3.3. Mechanical Properties of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

3.3.1. Microhardness and Elastic Modulus of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

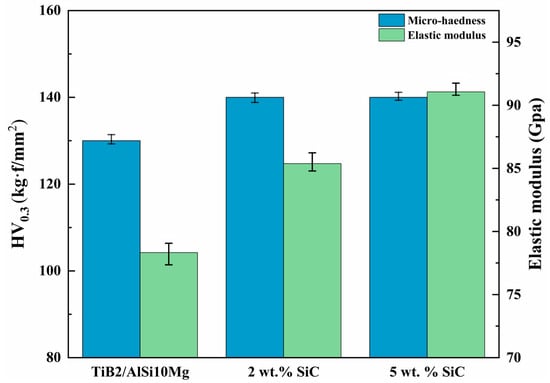

Figure 9 shows the microhardness and elastic modulus of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC particle contents. The microhardness of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite is 130 HV0.3. After adding 2 wt.% SiC particles, the hardness increases to 140 HV0.3, representing a 7.7% improvement. For the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, the microhardness remains at 140 HV0.3, showing no further increase compared with the 2 wt.% sample.

Figure 9.

Microhardness and elastic modulus of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC particle contents.

As shown in Figure 9, the elastic modulus of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite is 78.33 GPa. With the addition of 2 wt.% SiC, the modulus increases to 85.38 GPa, a 9% enhancement over the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite. When the SiC content increases to 5 wt.%, the modulus further rises to 91.06 GPa, corresponding to a 16.3% improvement relative to TiB2/AlSi10Mg. The high modulus of SiC (≈450 GPa), when combined with TiB2/AlSi10Mg, contributes to the enhanced stiffness of the composite material.

3.3.2. Room-Temperature Tensile Properties of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

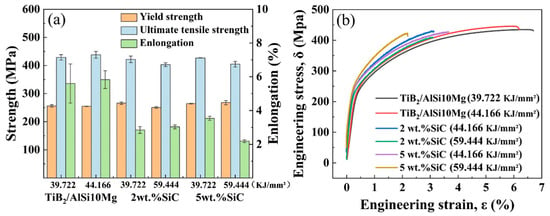

TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites containing 0 wt.%, 2 wt.% and 5 wt.% SiC were fabricated using the respective optimal processing parameters, and room-temperature tensile tests were carried out on these samples. A total of 18 tensile specimens were tested, covering different combinations of composition and energy-density conditions. For each composite system (TiB2/AlSi10Mg, 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg, and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg) and for each corresponding energy-density level, three parallel specimens were prepared and tested (n = 3), meaning that each energy-density condition included three independent tensile samples. Figure 10a and Table 4 present the room-temperature tensile properties of the SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites under different conditions, while Figure 10b shows the corresponding tensile stress–strain curves for composites with varying SiC contents.

Figure 10.

Tensile properties of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents: (a) yield strength, tensile strength and elongation; (b) stress–strain curves.

Table 4.

Mechanical properties of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents.

Compared with the AlSi10Mg alloy, the addition of dual reinforcement particles (SiC and TiB2) does not alter the general shape of the tensile curves of Al–Si alloys. However, both tensile strength and yield strength exhibit significant differences, indicating that the composites maintain excellent work-hardening capability.

It was observed that, under identical processing parameters, the ultimate tensile strengths of the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites decreased by 3.7% and 2.6%, respectively, compared with the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite. This trend is inconsistent with the strengthening behavior reported for LPBF-fabricated SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites [20]. The deviation arises because the addition of SiC particles induces a reaction between SiC and TiB2, leading to the formation of TiC phases, which weakens the nucleation-promoting effect of TiB2 particles. Consequently, the grain refinement capability is reduced, resulting in a potential decrease in mechanical performance.

However, the tensile strength of the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite is slightly higher than that of the 2 wt.% system, which can be attributed to the reinforcing effect of SiC particles. In general, the addition of high-modulus ceramic particles enhances the strength and stiffness of aluminum matrix composites. Nevertheless, this strengthening effect is often accompanied by a reduction in ductility [10,11,12], primarily due to the plastic incompatibility between the reinforcement particles and the aluminum matrix. This mismatch generates geometrically necessary dislocations and strain gradients at the interfaces, causing localized stress concentrations [27] and, consequently, lower ductility.

3.3.3. Fracture and Failure Behavior of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg Composites

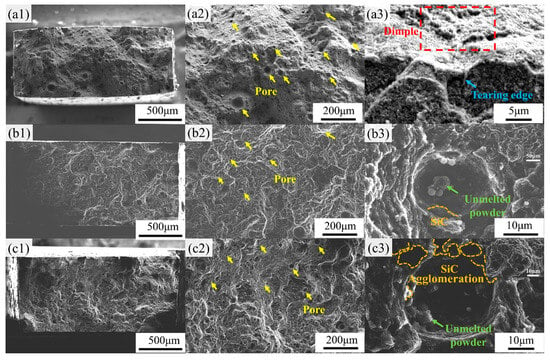

Figure 11 illustrates the tensile fracture morphologies of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC contents. The macroscopic fracture surfaces of the composites exhibit irregular and uneven ravine-like features (Figure 11(a1–c1)). At higher magnification, numerous spherical pore defects can be observed on the fracture surfaces (Figure 11(a2–c2)), accompanied by typical dimple structures and tear ridges (Figure 11(a3)). As shown in Figure 11(b3,c3), agglomerated SiC particles are visible both at the centers and edges of the pores, indicating localized particle clustering during solidification and deformation.

Figure 11.

Tensile fracture surfaces of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC particle contents: (a1,a2,a3) TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (b1,b2,b3) 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (c1,c2,c3) 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg.

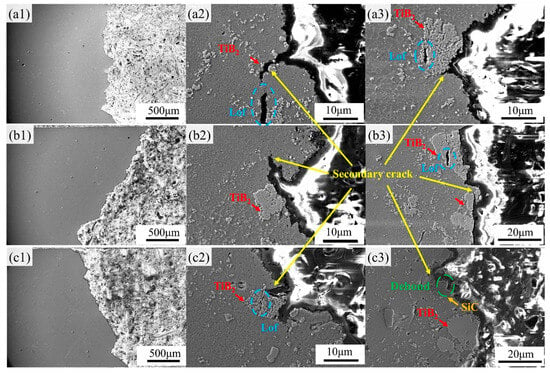

Figure 12 presents the fracture cross-sectional morphologies of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC particle contents. It can be observed that in both the LDED-fabricated TiB2/AlSi10Mg (Figure 12(a2,a3)) and 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg (Figure 12(b2,b3)) composites, the secondary cracks primarily originate from the TiB2 particles. In contrast, in the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite (Figure 12(c2,c3)), the secondary cracks mainly initiate from both TiB2 and SiC particles, exhibiting radial propagation with sharp and pointed edges.

Figure 12.

Tensile fracture longitudinal section of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites with different SiC particle contents: (a1,a2,a3) TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (b1,b2,b3) 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg; (c1,c2,c3) 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg.

In addition, debonding between SiC particles and the Al matrix is observed, as well as lack of fusion (LoF) defects near TiB2 particle clusters at the fracture sites. These LoF defects are closed in morphology and smooth internally, typically located adjacent to TiB2 particle interfaces. Such defects are attributed to insufficient melt pool energy input during the LDED process.

Overall, with the addition of 5 wt.% SiC, the elastic modulus of the composite increases by 16.3% (from 78.33 GPa to 91.06 GPa), while the ultimate tensile strength remains above 420 MPa. This combination of high stiffness and moderate strength makes the material particularly suitable for stiffness-dominated structural applications in which elastic deformation control is critical—such as lightweight support components, vibration-sensitive parts, high-speed equipment frames, and heat-dissipation structures requiring dimensional stability. In these scenarios, stiffness and vibration resistance are generally more important than uniform ductility. Furthermore, the high melting point and high rigidity of TiB2 and SiC are expected to enhance the dimensional stability of the composite under thermal cycling, offering potential advantages in aerospace, transportation, and thermal-management systems. We also clarify that the fracture and fatigue behavior of this system is primarily governed by defect-sensitive mechanisms, especially porosity and particle agglomeration. This indicates that future improvements in fatigue performance can be achieved by reducing pore formation and suppressing SiC/TiB2 clustering, without the need to alter the fundamental reinforcement design. From a manufacturing standpoint, compared with conventional casting or forging followed by machining, LDED provides notable benefits such as near-net-shape fabrication, high material utilization, adjustable reinforcement content, and the ability to construct functionally graded structures. These advantages make LDED particularly economical and practical for complex components and repair-oriented applications, especially in stiffness-dominated structural systems.

4. Discussion

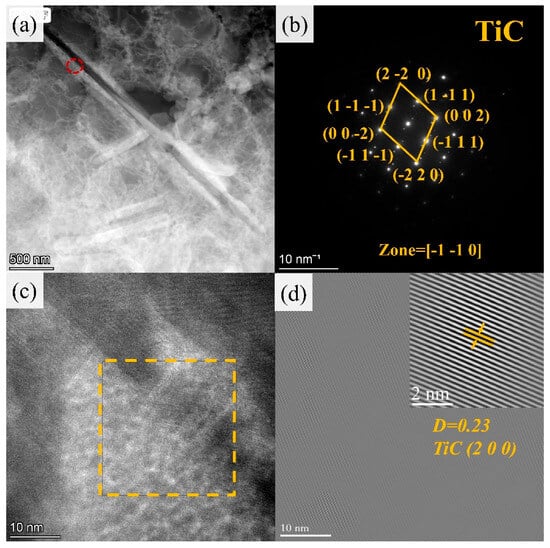

4.1. Interaction Between Different Reinforcement Phases

Previous XRD and EDS analyses provided preliminary characterization of the reaction products; however, due to the limited detection accuracy of these techniques and the low phase content, the identification of certain unknown phases could not be fully confirmed. To further verify and analyze the phase composition of the composites, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was employed for an in-depth investigation. Using the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite as an example, TEM analysis was conducted to examine and confirm the characteristics of the reaction-induced precipitates. Figure 13 presents the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image and electron diffraction pattern of the bright needle-like precipitate identified as TiC. Based on the calibration of the diffraction spots in Figure 13b, the needle-like phase was confirmed to be TiC, with a zone axis of [−1, −1, 0]. Therefore, the bright Ti-rich needle-like phase detected by EDS in Figure 8 can be identified as TiC. The high-resolution image further reveals that the interplanar spacing of the (200) crystal planes is 0.23 nm. The Ti element originates from TiB2 particles, while the C element is introduced by SiC particles, indicating that the formation of the TiC phase is closely associated with the interaction between SiC and TiB2 particles. During the LDED process, the low-melting-point AlSi10Mg alloy melts first under laser irradiation, while the SiC and TiB2 particles are embedded in the molten matrix. Owing to their high melting points—TiB2 (3230 °C) and SiC (2730 °C) [28]—these particles do not melt completely but remain partially dissolved within the melt pool. This partial dissolution provides favorable conditions for TiC formation. According to reaction (4), under high-temperature conditions, Ti from TiB2 and C from SiC are released into the molten pool, where they react and promote the nucleation and growth of the TiC phase.

Ti + C→TiC

Figure 13.

TEM characteristics of TiC phase of 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites: (a) HAADF image; (b) FFT image; (c) HRTEM image; (d) IFFT image.

The probability and priority of chemical reactions are determined by the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of each reaction, which dictates whether the reaction can occur spontaneously. The change in Gibbs free energy is expressed by the following equation:

where ΔH, ΔS, and T represent the standard enthalpy change, standard entropy change, and thermodynamic temperature, respectively.

According to Yi et al. [29], based on known thermodynamic data, the Gibbs free energy change per mole of reactant for reaction (5) was calculated to be ΔH = −184,096 J·mol−1, ΔS = −12.134 J·mol−1·K−1, and ΔG = −184,096 + T × 12.314 (J·mol−1). Within the temperature range of 1100–2000 K, the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of reaction (5) remains negative, indicating that the chemical reaction can occur spontaneously within this temperature interval. Similarly, Wang et al. [30] analyzed the thermodynamic and kinetic behavior of the Ti–C system and found that the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) for reaction (4) is negative at all investigated temperatures, demonstrating that the reaction is thermodynamically favorable and can proceed spontaneously. Further analysis revealed that the enthalpy change (ΔH) of the reaction is also negative across the temperature range, indicating that heat is released during the reaction and the system temperature increases. This temperature rise further promotes the reaction between Ti and C, thereby facilitating the formation of the TiC phase. Consequently, these thermodynamic and kinetic characteristics provide favorable conditions for the synthesis of TiC, confirming that the reaction can readily proceed under high-temperature environments, leading to the successful formation of the TiC phase.

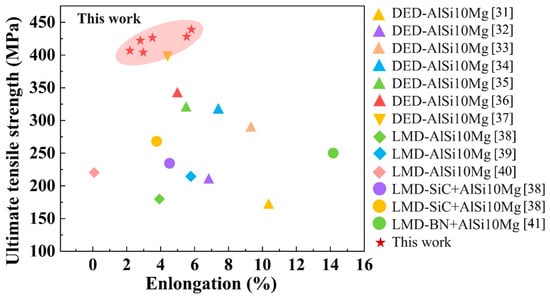

4.2. Exploration of Strengthening Mechanisms

To investigate the effect of TiB2 and SiC particles on the mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg alloys, the tensile strength and elongation of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites from various references and the present work were compared. As shown in Figure 14, all samples in this study exhibited ultimate tensile strengths (UTS) above 400 MPa, and those fabricated under optimized processing parameters achieved UTS values exceeding 420 MPa. Among them, the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite exhibited the highest UTS of 438.00 MPa. Compared with Al–Si alloys fabricated by DED and LMD reported in previous studies [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], the mechanical performance of the composites in this work shows a significant improvement. For example, relative to the 344 MPa reported by Kiani et al. [36], the UTS increased by approximately 94 MPa, corresponding to an improvement of about 21.4%. This result demonstrates that the introduction of TiB2 particles markedly enhances the mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg alloys, playing a crucial role particularly in grain refinement and strength enhancement. By incorporating TiB2 particles, Al–Si alloys with superior strength characteristics can be obtained. In the following discussion, the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite fabricated by LDED is selected to elucidate its dominant strengthening mechanisms, which can be quantitatively analyzed using Equation (6).

Figure 14.

The tensile strength and elongation of SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg alloy from different references and current work [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

For grain boundary strengthening (grain refinement strengthening), according to the Hall–Petch equation [42], the contribution of this mechanism to the increase in tensile strength can be calculated using Equation (7):

Here, k is the Hall–Petch coefficient (50 MPa·μm1ᐟ2) [43]; d1 and d2 represent the average grain sizes of the LDED-fabricated AlSi10Mg alloy and the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, which are 48 μm [34] and 10.4 μm, respectively. Therefore, the grain boundary strengthening contribution is approximately 8.29 MPa.

For the Orowan strengthening induced by TiB2 particles [25], the corresponding calculation is expressed by Equation (8):

Here, M is a material constant with an approximate value of 2; G and b represent the shear modulus of Al (~26.5 GPa) and the Burgers vector (0.286 nm), respectively; r and f denote the average particle size of TiB2 (~120 nm) and its volume fraction (~4 vol.%), respectively. Consequently, the Orowan strengthening contributes an increment in tensile strength of approximately 53.60 MPa.

In the composite, the strong interfacial bonding between TiB2 particles and the α-Al matrix facilitates efficient load transfer from the ductile matrix to the hard ceramic particles. Therefore, the load transfer strengthening [44] can be calculated using Equation (9):

Here, f represents the volume fraction of TiB2 (4 vol.%), and σₘ denotes the tensile strength of the AlSi10Mg matrix (314 MPa [34]). The load transfer strengthening contribution is therefore approximately 18.84 MPa.

For the dislocation strengthening mechanism [42], the corresponding calculation is expressed by Equation (10):

Here, α is the dislocation interaction constant (~0.16), M is the Taylor factor (~3.06), G and b represent the shear modulus of aluminum (~26.5 GPa) and the Burgers vector (0.286 nm), respectively. ρ1 and ρ2 denote the dislocation densities of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite (1.81 × 1014 m−2) and AlSi10Mg alloy (1.21 × 1014 m−2), respectively [42]. Accordingly, the dislocation strengthening of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite is approximately 9.1 MPa. By combining all the strengthening mechanisms discussed above, the theoretical increase in tensile strength of the composite relative to the AlSi10Mg alloy is approximately 89.83 MPa, which is in good agreement with the experimental results.

In the dual-particle-reinforced system, the introduction of SiC further alters the contribution pattern of the strengthening mechanisms. On one hand, the high modulus of SiC significantly enhances the stiffness of the composite, increasing the elastic modulus by more than 16%. On the other hand, the reaction between SiC and TiB2 forms TiC, consuming part of the TiB2 particles and thereby weakening the contributions from grain refinement and load transfer. Meanwhile, the precipitation of brittle Al4C3 acts as a crack initiation site during tensile deformation, offsetting part of the strengthening effect. Consequently, the strength enhancement in the dual-particle system is limited, while the elastic modulus is markedly improved. This “synergistic–competitive” interaction represents a key characteristic of the LDED-fabricated hybrid particle-reinforced composites, governing the balance between strength and stiffness in such materials.

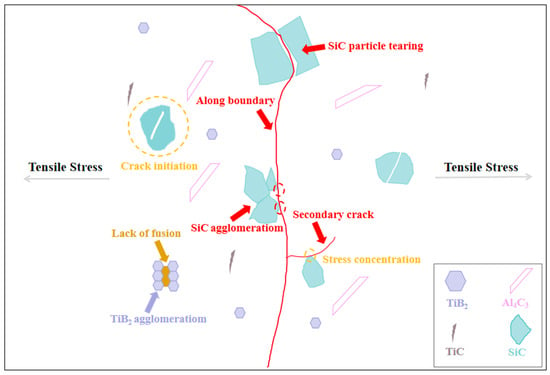

4.3. Failure Behavior Analysis

In Figure 11(a3), the presence of dimples and tear ridges indicates that the fracture mode of the composite primarily exhibits a mixed ductile–brittle fracture. As observed in Figure 11(a2–c2), a large number of spherical pores appear on the fracture surfaces, which are attributed to the growth and coalescence of porosity defects during tensile deformation. During the stretching process, these small pores elongate under external stress and eventually evolve into spherical cavities. The applied stress tends to concentrate near these pores, where crack initiation occurs. Consequently, porosity defects not only deteriorate the mechanical properties of the composites but also act as weak points that can lead to failure. In addition, after the incorporation of SiC particles, the composites exhibited a marked reduction in elongation. This can be attributed to the brittle nature of SiC ceramics and the strong interfacial mismatch between SiC and the metallic matrix. Under high loads, these interfaces serve as preferential crack propagation paths, resulting in a more brittle overall fracture behavior characterized by rapid crack propagation and limited plastic deformation. Furthermore, SiC agglomeration causes localized stress concentration zones at the reinforcement–matrix interfaces, promoting microcrack initiation under external loading, thereby reducing the failure resistance and ductility of the composites.

Figure 12 shows the initiation behavior of secondary cracks during fracture for TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites containing different reinforcement particle contents. The results indicate that the agglomeration of TiB2 and SiC particles induces local stress concentration, acting as crack initiation sites that promote crack nucleation and propagation. Additionally, interfacial debonding between SiC particles and the α-Al matrix was observed, providing an easy path for crack growth and significantly reducing the plasticity and toughness of the material. Further examination of the fracture region revealed frequent lack of fusion (LoF) defects near TiB2 particle clusters, suggesting that TiB2 particles may disturb the melt pool dynamics during the LDED process, leading to localized unmelted regions. Generally, large and irregular LoF defects cause severe stress concentration, accelerating crack initiation and reducing the fatigue life of the material [22]. The agglomeration of TiB2 particles not only increases the risk of local stress concentration but also promotes preferential crack growth. During crack propagation, the presence of numerous columnar grains in the matrix limits plastic accommodation, resulting in rapid microcrack expansion and the formation of secondary cracks, further compromising the overall mechanical performance of the composite.

Based on these observations, the fracture mechanism of the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite is illustrated in Figure 15. When the applied stress reaches a critical level, cracks first initiate from pre-existing defects, followed by tearing of SiC particles, and subsequently the formation of microcracks in the matrix and TiB2 regions. Once the number of cracks reaches a critical threshold, the specimen undergoes instantaneous fracture. It is noteworthy that in the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, fracture is predominantly governed by the brittle behavior of SiC particles, while the ductility-enhancing effect of TiB2 is relatively minor. Moreover, the partial agglomeration of TiB2 particles further exacerbates the tendency toward brittle fracture of the matrix.

Figure 15.

Fracture mechanism of 5 vol% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite fabricated by LDED.

5. Conclusions

In this study, hybrid particle-reinforced aluminum matrix composites (AMCs) were fabricated for the first time using the Laser-Directed Energy Deposition (LDED) technique, and the effects of different SiC particle contents on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites were systematically investigated. The influence of areal energy density on the metallurgical quality of composites with varying SiC contents was first analyzed, followed by an examination of the solidification microstructure, precipitated phases, and grain morphology. Furthermore, the effects of SiC content and processing parameters on tensile properties were explored, and fracture behavior was analyzed to evaluate the failure mechanisms. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- The addition of SiC particles slightly reduced the metallurgical quality of the LDED-fabricated TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites. Within the tested process parameter range, the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites both achieved a maximum relative density of 98.9%.

- The incorporation of SiC did not alter the solidification morphology or particle distribution of the LDED-fabricated composites. The melt pool center still exhibited a bright, fibrous Al–Si eutectic network. Additionally, in the 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite, needle-like phases were observed around SiC agglomerations, where the dark-contrast phase was identified as Al4C3, and the bright-contrast phase as TiC.

- Compared with the LDED-fabricated AlSi10Mg alloy, the tensile strength of the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite reached 438.00 MPa, representing an increase of 39.5%. In contrast, the 2 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg and 5 wt.% SiC + TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites exhibited lower tensile strengths of 421.71 MPa and 426.74 MPa, respectively. The decrease in tensile strength after adding SiC is primarily attributed to SiC particle agglomeration and the consumption of TiB2 particles due to TiC formation.

- The addition of SiC particles significantly enhanced the elastic modulus of the composites. With 2 wt.% SiC, the elastic modulus increased to 85.38 GPa, representing a 9% improvement over the TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite. When 5 wt.% SiC was added, the elastic modulus further increased to 91.06 GPa, corresponding to a 16.3% improvement.

- The composites primarily exhibited a mixed ductile–brittle fracture mode. However, pore defects (>10 μm) and SiC/TiB2 clusters acted as crack initiation sites, causing stress concentration and promoting the propagation of secondary cracks. Significant interfacial debonding between SiC particles and the matrix was observed, and in the 5 wt.% SiC composite, cracks were more likely to initiate along particle cluster interfaces, leading to further degradation of ductility.

Author Contributions

X.Z.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Data curation. S.Z.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation. Y.P.: Methodology, Investigation. L.G.: Writing—review and editing, Investigation. C.K.: Validation. Z.F.: Methodology, Investigation. W.F.: Formal analysis. H.T.: Resources, Supervision. X.L.: Resources, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Svetlizky, D.; Zheng, B.; Vyatskikh, A.; Das, M.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Schoenung, J.M.; Lavernia, E.J.; Eliaz, N. Laser-based directed energy deposition (DED-LB) of advanced materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.-G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2021, 8, 703–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kapil, S.; Das, M. A comprehensive review of the methods and mechanisms for powder feedstock handling in directed energy deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Parvez, M.M.; Liou, F. A Review on Metallic Alloys Fabrication Using Elemental Powder Blends by Laser Powder Directed Energy Deposition Process. Materials 2020, 13, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, A.; Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Biamino, S.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P. Application of Directed Energy Deposition-Based Additive Manufacturing in Repair. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Su, Y.; Pi, X.; Xin, S.; Li, K.; Liu, D.; Lin, Y.C. Achieving high strength 316L stainless steel by laser directed energy deposition-ultrasonic rolling hybrid process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 903, 146665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, T.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, D. Impact of alumina content and morphology on the mechanical properties of bulk nanolaminated Al2O3-Al composites. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Feng, K.; Li, Z.; Kokawa, H. Effects of rare earth elements on the microstructure and wear properties of TiB2 reinforced aluminum matrix composite coatings: Experiments and first principles calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 530, 147051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Muñiz-Lerma, J.A.; Trask, M.; Chou, S.; Walker, A.; Brochu, M. Microstructure and mechanical property considerations in additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys. MRS Bull. 2016, 41, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Cao, Y.; Nie, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; An, X.; Liao, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Unique defect evolution during the plastic deformation of a metal matrix composite. Scr. Mater. 2019, 162, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Lu, F.; Huang, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Improving the high-temperature ductility of Al composites by tailoring the nanoparticle network. Materialia 2020, 9, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q. Enhanced elevated-temperature mechanical properties of Al-Mn-Mg containing TiC nano-particles by pre-strain and concurrent precipitation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 718, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Hao, D.; Al-Hamdani, K.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Z.; Clare, A.T. Direct metal deposition of TiB2/AlSi10Mg composites using satellited powders. Mater. Lett. 2018, 214, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Eckert, J.; Prashanth, K.-G.; Wu, M.-W.; Kaban, I.; Xi, L.-X.; Scudino, S. A review of particulate-reinforced aluminum matrix composites fabricated by selective laser melting. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2001–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Gu, D.; Guo, S.; Wang, R.; Ding, K.; Prashanth, K.G. Grain refinement in laser manufactured Al-based composites with TiB2 ceramic. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Huang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a novel (TiB2 + TiC)/AlSi10Mg composite prepared by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 834, 142435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, B.; Lv, Z.; Yan, X. Microstructures and mechanical behaviors of reinforced aluminum matrix composites with modified nano-sized TiB2/SiC fabricated by selective laser melting. Compos. Commun. 2023, 37, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Yan, X.; Fu, Z.; Niu, B.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Chang, C.; Yi, J. In situ formation of D022-Al3Ti during selective laser melting of nano-TiC/AlSi10Mg alloy prepared by electrostatic self-assembly. Vacuum 2021, 188, 110179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Peng, C.; Cai, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, X. Microstructural evolution and mechanical performance of in-situ TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite manufactured by selective laser melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 853, 157287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Wu, F.; Dang, M.; Feng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Kang, C.; Fan, W.; Wang, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, F.; et al. Laser powder bed fusion of SiC particle-reinforced pre-alloyed TiB2/AlSi10Mg composite with high-strength and high-stiffness. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 334, 118635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-S.; Chen, P.; Qiu, F.; Yang, H.-Y.; Jin, N.T.Y.; Chew, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, R.; Jiang, Q.-C.; Tan, C. Review on laser directed energy deposited aluminum alloys. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlizky, D.; Das, M.; Zheng, B.; Vyatskikh, A.L.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Schoenung, J.M.; Lavernia, E.J.; Eliaz, N. Directed energy deposition (DED) additive manufacturing: Physical characteristics, defects, challenges and applications. Mater. Today 2021, 49, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xi, X.; Gu, T.; Tan, C.; Song, X. Influence of heat treatment on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of TiB2/Al 2024 composites fabricated by directed energy deposition. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14223–14236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, J.; Tchuindjang, J.T.; Lecomte-Beckers, J.; Rigo, O.; Habraken, A.M.; Mertens, A. Influence of Si precipitates on fracture mechanisms of AlSi10Mg parts processed by Selective Laser Melting. Acta Mater. 2019, 175, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jian, Z.; Ren, Y.; Li, K.; Dang, B.; Guo, L. Influence of TiB2 volume fraction on SiCp/AlSi10Mg composites by LPBF: Microstructure, mechanical, and physical properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 3697–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Bi, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Tian, Z.; Qin, X. Effect of TiB2 content on microstructural features and hardness of TiB2/AA7075 composites manufactured by LMD. J. Manuf. Processes 2020, 53, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y. Stiff, strong and ductile heterostructured aluminum composites reinforced with oriented nanoplatelets. Scr. Mater. 2020, 189, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Sen, B.; Beemkumar, N.; Singh Chohan, J.; Bains, P.S.; Singh, G.; Kumar, A.V.; A, J.S. Development and wear resistivity performance of SiC and TiB2 particles reinforced novel aluminium matrix composites. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Rao, J.H.; Liu, H. Microstructure and dynamic microhardness of additively manufactured (TiB2 + TiC)/AlSi10Mg composites with AlSi10Mg and B4C coated Ti powder. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 939, 168718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, H.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shang, W.; Clare, A.T.; Lin, X. Enhanced mechanical properties of in situ synthesized TiC/Ti composites by pulsed laser directed energy deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 855, 143935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, H.; Gao, M. Effect of processing parameters on solidification defects behavior of laser deposited AlSi10Mg alloy. Vacuum 2019, 167, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, G.; de Menezes, J.T.O.; Belelli, F.; Bruzzo, F.; López, E.; Volpp, J.; Castrodeza, E.M.; Casati, R. Fracture toughness of AlSi10Mg alloy produced by direct energy deposition with different crack plane orientations. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wei, K.; Liu, M.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Zeng, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg alloy built by laser powder bed fusion/direct energy deposition hybrid laser additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wei, L.; Yang, H.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W. Investigations of the processing–structure–performance relationships of an additively manufactured AlSi10Mg alloy via directed energy deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 944, 169050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Han, X.; Liu, S. In-situ laser shock peening for improved surface quality and mechanical properties of laser-directed energy-deposited AlSi10Mg alloy. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, P.; Dupuy, A.D.; Ma, K.; Schoenung, J.M. Directed energy deposition of AlSi10Mg: Single track nonscalability and bulk properties. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wei, Q.; Tang, Z.; Oliveira, J.P.; Leung, C.L.A.; Ren, P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Effects of hatch spacing on pore segregation and mechanical properties during blue laser directed energy deposition of AlSi10Mg. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Chen, B.; Tan, C.; Song, X.; Dong, Z. Influence of micron and nano SiCp on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of laser metal deposition AlSi10Mg alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 306, 117609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, E.; Chang, T.; Zhao, L.; Xing, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Lu, J.; Cheng, J. Laser metal deposition of AlSi10Mg for aeroengine casing repair: Microhardness, wear and corrosion behavior. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, F.; Vogt, S.; Göbel, M.; Möller, M.; Frey, K. Laser Metal Deposition of AlSi10Mg with high build rates. Procedia CIRP 2022, 111, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, C.; Araby, S.; Cai, R.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Wang, W. Highly ductile and mechanically strong Al-alloy/boron nitride nanosheet composites manufactured by laser additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Processes 2023, 89, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.K.; Chen, H.; Bian, Z.Y.; Sun, T.T.; Ding, H.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Lian, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.W. Enhancing strength and ductility of AlSi10Mg fabricated by selective laser melting by TiB2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 109, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Ji, G.; Chen, Z.; Addad, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.W.; Vleugels, J.; Van Humbeeck, J.; Kruth, J.P. Selective laser melting of nano-TiB2 decorated AlSi10Mg alloy with high fracture strength and ductility. Acta Mater. 2017, 129, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Xu, J.-Q.; Choi, H.; Pozuelo, M.; Ma, X.; Bhowmick, S.; Yang, J.-M.; Mathaudhu, S.; Li, X.-C. Processing and properties of magnesium containing a dense uniform dispersion of nanoparticles. Nature 2015, 528, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).