Abstract

This research focuses on the investigation of microstructure, deformation, and superplastic behavior in wide range of strain rates of novel crossover Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy with Y/Er. The precipitation and superplastic behavior of the Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr-Cr-Ti with Er/Y and Fe/Si impurities alloys have been studied. The microstructure of the alloys with nano-sized precipitates and micron-sized particles allows obtaining a micrograin stable microstructure. The spherical D023-Al3(Er,Zr) precipitates with a diameter of about 20 nm and rod-like crystalline and qusicrystalline E (Al18Mg3Cr2) precipitates with a thickness of about 20 nm and length of about 150–200 nm were identified by transmission electron microscopy. The superplastic deformation behaviors were investigated under different temperatures of 460–520 °C and different strain rates of 3 × 10−4 to 3 × 10−3 s−1. The microstructure observation shows that uniform and equiaxed grains can be obtained by dynamic recrystallization before superplastic deformation. The alloy with Y exhibits inferior superplastic properties, while the alloy with Er has an elongation of more than 350% at a rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 and a temperature of 510 °C.

Keywords:

crossover alloy; yttrium; erbium; precipitation; grain structure; superplacticity; energy activation 1. Introduction

The lightweight aluminum-based alloys have a wide commercial application due to possibility of achieving of a good combination of properties [1,2,3,4,5]. The aluminum-based alloys are conventionally divided in the different groups based on the specific properties [1,2]. The Al-Si alloys have excellent casting properties and wear resistance with medium strength; the Al-Zn-Mg-(Cu) alloys are the high strength alloys with lacks in casting, corrosion, and high temperature properties; and the Al-Cu-(Mg) alloys have the good ambient and high temperature strength but low castability and corrosion resistance [1,2]. One of the ways of improving the castability and high temperature performance of Al-Si [6,7,8], Al-Zn-Mg-(Cu) [9,10,11,12,13,14], and Al-Cu-(Mg) [15,16,17,18] is alloying by eutectic forming and rare earth elements [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. From the other hand the approach of crossover alloys development was proposed in [19]. The crossover alloys composition was developed based on using the scrap of different groups of Al alloys [19]. The crossover alloys combine the best properties from different Al alloys [8,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The developing of the Al-Zn-Mg-(Cu) crossover alloys based on the principle of Zn/Mg ratio near 1 [6,32,33,34] allowed the good combination of castability, deformation behavior, strength, heat, and corrosion resistance [21,23,25,26,28,29,30]. The high-performance Al-2.5Zn-2.5Mg-2.5Cu-Er(Y)-Zr-Cr-Ti-Fe-Si alloy [29] was developed based on the discussed principles. The Zn/Mg/Cu ratio and eutectic Al8Cu4Y(Er) phase provide good castability; the Zn/Mg/Cu ratio provide strength at room and elevated temperature, and corrosion resistance due to the T’ aging precipitates. The second role of Y(Er) is the formation of the Al3(Y,Zr) or Al3(Er,Zr) precipitates under solution treatment. The E (Al18Mg3Cr2) precipitates should be additionally formed on the same stage based on the thermodynamic calculations [29]. One of the most important discoveries in the effect of Y(Er) is increasing the solidus temperature of the alloys with Zn/Mg/Cu content less than 3% of each [28,29]. The micron-sized solidification origin phases supersaturated (Al) with nano-sized precipitates is favorable for grain refinement that contributes to superplastic behavior of Al alloys.

Superplasticity is the capacity of alloys to undergo significant quasi-uniform plastic deformation, which is realized due to the high strain rate sensitivity index m (≥0.5) in alloys with a grain size of less than 10 μm [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Under certain temperature and strain rate conditions, the material demonstrates low flow stress, which allows using gas pressure of several atmospheres to produce a product using the superplastic forming method. The smaller the grain size, the lower the stress values and temperatures of the effect manifestation, the higher the deformation rates and plasticity characteristics [47,48]. The production of details with complex geometry under conditions of superplasticity is a promising technology for forming alloys that have reduced processability during traditional stamping.

High-strength alloys have high superplastic properties if alloyed with zirconium and scandium. Small amounts of elements such as Sc and Zr stabilize the microstructure [49,50,51], since fine dispersion particles of Al3Sc and/or Al3Zr formed during casting inhibit grain growth at high temperatures. However, Sc and Zr are very expensive and would considerably increases costs. Known superplastic alloys are either non-heat-treatable (such as AA5083) and do not achieve the required properties [52,53] or are heat-treatable (such as AA7475) but are subjected to possible warping of thin-walled parts when cooled in water [54]. Therefore, for the use of the superplastic forming, the development of new alloys with advanced superplastic behavior is relevant.

The task of creating superplastic sheets with increased properties is based on development of a heterogeneous structure that allows refining grain due to the particle stimulated nucleation effect (PSN) and Zener pinning effect. The novel crossover alloys combine the improved casting properties, good strength, and improved heat resistance and can exhibit superplasticity due to their heterogeneous structure with bimodal particle size distribution. However, the ability to deform at elevated temperatures of this group of alloys has been practically not studied [55].

This research focuses on the investigation of microstructure, deformation, and superplastic behavior in wide range of strain rates of the novel crossover Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy with Y/Er. The microstructure of the alloy after mechanical treatment and superplastic behavior in the strain rates range of 10−4–10 s−1 and temperature were analyzed in depth and discussed in the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

The detailed methodology of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuY(Er)Cr alloy composition, melting, solution treatment, and rolling is described in [29]. The composition of the alloys is presented in Table 1. The copper water cooling mold with internal sizes of 120 × 40 × 20 mm3 was used for obtaining ingots. The cooling rate under solidification was about 15 K/s. The ingots before rolling were solution treated at 480 °C for 3 h and 520 °C for 6 h with water quenching. The hot rolling was processed at 500 °C to the thickness of 5 mm and at room temperature to 1 mm. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) TESCAN VEGA 3LMH (Tescan, Brno, Kohoutovice, Czech Republic) was used to demonstrate the size and distribution of the solidification origin phases in the sheets after rolling. The rolled samples of sheet Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr were annealed at 510 °C before transmission electron microscopy (TEM) investigation. The JEOL–2100 TEM (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used for precipitates investigation. The fast Fourier transformation (FFT) method was used for identification of the precipitates.

Table 1.

Composition of the investigated alloys in wt.%. (SEM EDX).

The grain structure after annealing before superplastic deformation was studied by optical microscopy (OM) (Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany)) in polarized light. The samples were prepared by mechanical grinding and polishing using a colloidal silica suspension by Struers OP-U (Struers APS, Ballerup, Denmark). Samples after polishing were subjected to anodic oxidation in Barker’s reagent. The grain size was measured by secant method based on three images for each state. The hardness was measured using by tester DuraScan 20 G5 Emco-Test (EMCO-TEST Prümaschinen, Kuchl, Austria).

Elevated temperature tensile testing was performed using a Walter-Bai LFM 100 testing machine with Dion-Pro software (Walter + Bai AG, Löhningen, Switzerland) over the temperature range of 460–520 °C. The specimens had dimensions of gauge part 14 × 6 × 1 mm3 and were cut along the rolling direction; three specimens were used for each test condition. Tests were carried out with a step-by-step changes strain rate and then the strain rate sensitivity index m was calculated. The superplasticity tests were performed in the resistance furnace with three controlling thermocouples. The strain rate sensitivity index m was calculated as the first derivative of the log-transformed Backofen equation [56,57]. At a high value of the m-index, tests were carried out with constant strain rates of 3 × 10−4–3 × 10−3 s−1 in the temperature range 460–520 °C. The thermocouple was welded to the sample under compression tests. The heating was provided by current.

The processing maps were constructed using hydraulic-type thermomechanical simulator Gleeble 3800 (Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA). The cylindrical samples were 10 mm in diameter and 15 mm in height and were compressed at different temperatures and strain rates. The heating rate to the target temperature was 5 °C/s. The sample was held at the compression temperature for 30 s distribution before deformation to provide uniform heating. The overall strain was about 1. The compression curves at temperatures of 350, 400, 450, and 500 °C and strain rates of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 s−1 were obtained. The correction of the compression curves considering the friction and adiabatic heating were performed based on [58].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Precipitation Behavior

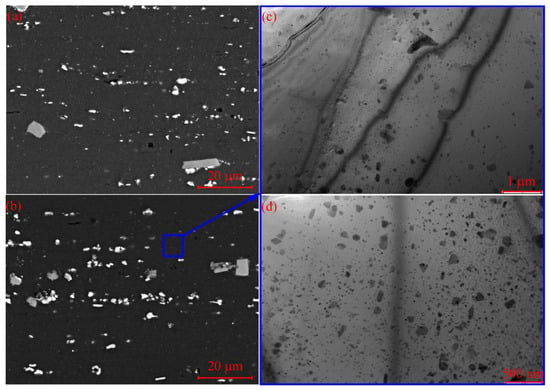

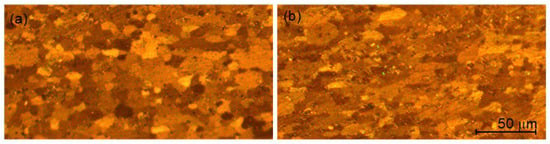

The detailed investigation of the as-cast and solution-treated microstructure of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuY(Er)Cr alloys is presented in [29]. The main structure parts before rolling were the Al solid solution and near spherical Al8Cu4Y(Er) and Mg2Si phases with a size of about 1 µm. The primary crystals containing Al, Cr, Ti, and Er(Y) did not change morphology under solution treatment and subsequent thermo-mechanical treatment (Figure 1a,b). The solidification origin Al8Cu4Y(Er) and Mg2Si phases were homogenously distributed in the rolling direction (Figure 1a,b). The fine white precipitates are clearly seen in the SEM images (Figure 1a,b) in the Al solid solution. The Al3(Zr,Ti) and E (Al18Mg3Cr2) precipitates must be formed in the alloy without Y(Er) based on the thermodynamic calculation during solution treatment at 480 + 520 °C [29]. The Y and Er substitute the Zr atoms in the lattice of the Al3Zr precipitates. The types of the precipitates were investigated in detail in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYErCr alloy. The two types of precipitates are clearly visible in the Al solid solution based on the TEM images (Figure 1c,d).

Figure 1.

The as-rolled SEM (a,b) and annealed at 510 °C for 20 min TEM (c,d) microstructure of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr (a) and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr (b–d) alloys sheets.

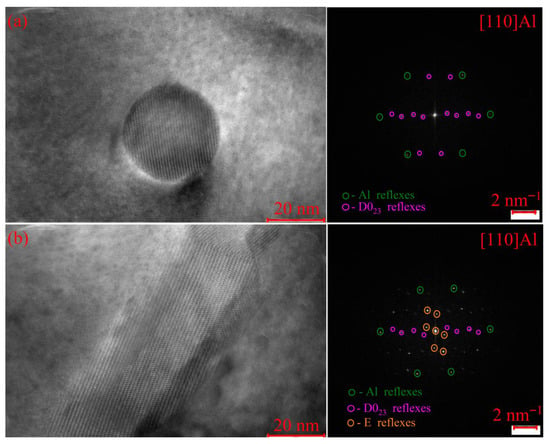

The types and crystal structure of the precipitates were investigated in the Al axes [110] (Figure 2). The near spherical precipitates with diameter about 20 nm were identified as D023-Al3(Er,Zr) (Figure 2a,b). The reflexes from D023 precipitates were labeled purple in FFT in Figure 2. The L12-Al3(Y,Zr) precipitates with same diameter of 20 ± 3 nm were found in the similar Al-3.7Zn-3.6Mg-3.8Cu-1.1Y-0.2Zr-0.2Cr-0.1Fe-0.1Si-0.1Ti alloy but solution-treated at a lower temperature of 480 °C for 10 h [111]. Obtained results demonstrated that the increasing the solution treatment temperature from 480 to 520 °C provides transformation of L12-structured precipitates to D023-structured precipitates. The addition of Y or Er increased the thermal stability of the precipitates. The L12-D023 transformation processed completely with Al3Zr precipitates after 1000 h of annealing at 400 °C [59]. A similar temperature of the L12-D023 transformation was obtained in the Al-Zr and Al-Zr-Ti alloys [60].

Figure 2.

Annealed at 510 °C for 20 min TEM microstructure of the rolled Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy sheet: (a)—D023 precipitate, (b)—D023 and E precipitates, (c,d)—E precipitate with different orientation, (e)—E precipitate with crystalline and QC structure, (f)—E precipitate with QC structure.

The second type of the precipitates is the rod-like E (Al18Mg3Cr2) phase (Figure 2b–d). The image in Figure 2b represented both D023-Al3(Er,Zr) and E precipitates. The additional reflexes from E precipitate are labeled orange. The separate E precipitates and FFT from precipitates with two different orientations are presented in images of Figure 2c,d. The obtained images and FFT are well correlated with deep atomic-scale investigation of the heterogeneous precipitation in the E dispersoid of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu aluminum alloy [61]. The E precipitates in our study have a thickness of about 20 nm and length of about 150–200 nm (Figure 2b–d).

Additionally found in the sample were a few precipitates with partially and completely non-crystalline structure (Figure 2d,e). D. Shechtman and colleagues discovered this phase type with long-range orientation order and without translation symmetry in the Al-Mn-Fe-(Cr) alloy [62]. The FFT constructed from the precipitate area in Figure 2e is much closer with the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) obtained from icosahedral phase or quasicrystal (QC) [62]. The unlabeled reflexes in FFT from the precipitate with partially crystalline structure (Figure 2d) repeated the reflexes from QC (Figure 2e). The reflexes from E phase are presented in FFT of the partially crystalline structure (Figure 2d). Obtained results allow concluding that E precipitates are presented in crystalline and QC states.

3.2. Deformation Behavior and Processing Maps

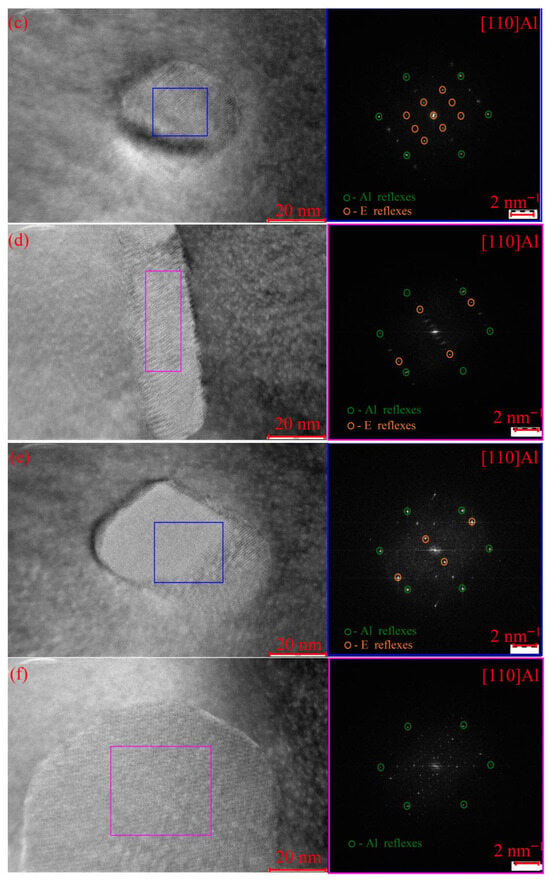

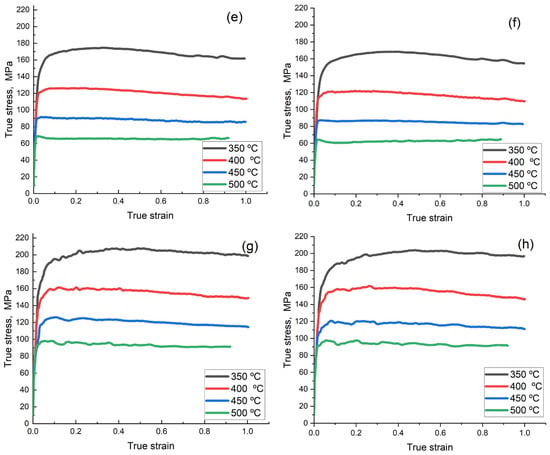

The Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys demonstrated typical hot deformation behavior (Figure 3). True stress decreased from 100–200 MPa to 20–100 MPa, while strain rate increased from 0.01 to 10 s−1. The increase in the temperature accelerates the non-conservative movement of the dislocations and facilitates the deformation process. The dislocations have more time for sliding and creeping to other planes at low strain rates, which leads to decreases in the stress. True stress–strain dependencies have similar shapes with a peak in stress. The strain hardening and dynamic recovery processed before the reaching of the peak stress, and the dynamic recrystallization is the main process after.

Figure 3.

Compression stress–strain dependencies of (a,c,e,g) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and (b,d,f,h) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys at different strain rates of 0.01 s−1 (a,b), 0.1 s−1 (c,d), 1 s−1 (e,f), and 10 s−1 (g,h).

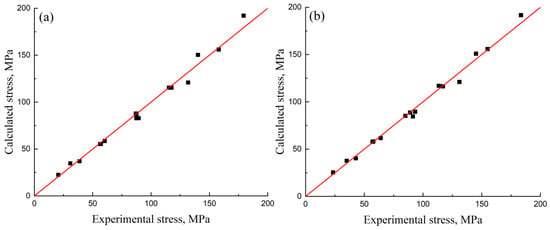

The effective activation energy (Q) is used to compare the hot deformation behavior of the alloys. Zener–Hollomon parameter (Z) is dependent on the Q-value and temperature (Equation (1) in Table 2). From the other hand Z can be calculated as a hyperbolic sine of stress (S) (Equation (2)) at steady state. The determination of the α-constant in Equation (2) needs the construction of particular dependences between stress and Z-parameter as laws for high stresses (Equation (3)) and low stresses (Equation (4)). As a result, the α-constant may be calculated by Equation (5). The Q-value is determined by the least square method by the logarithmization of Equations (2)–(4). The stress values at the steady state are used to find the material constants. Calculated by Equation (3), the true stress in dependence with experimental values and constants of the constitutive equation are presented in Figure 4. The Q value equals 173 kJ/mol and 172 kJ/mol for the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys, respectively. The effective activation energy for the investigated alloys is equal or less than in the Al3Zn3Mg3CuEr alloy without Cr and with higher content of Zn/Mg/Cu/Er [30]. The lower content of Zn/Mg/Cu in the Al solid solution and volume fraction of intermetallic particles in the investigated alloy provide the same deformation behavior as the Al3Zn3Mg3CuEr alloy.

Table 2.

Equations for effective activation energy (Q) and Zener–Hollomon parameter (Z) [63].

Figure 4.

Comparison of calculated and experimental steady state true stress of (a) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and (b) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys.

The important parameter for hot deformation behavior analysis is the strain rate sensitivity coefficient (m). The m-coefficient was calculated based on Equation (6) (Table 3). The m-value for the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys is 0.176 ± 0.002 and 0.163 ± 0.002, respectively. A larger sensitivity to the increasing of strain rate and localization of deformation determines by a larger m-value.

Table 3.

Equations for hot processing maps construction [64].

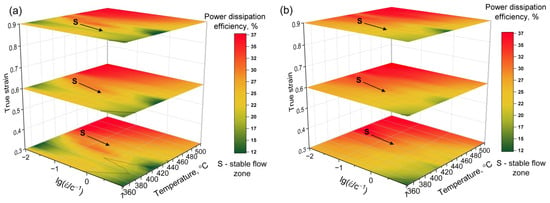

The hot formability of the alloys was investigated by the processing maps construction [64]. This approach involves the calculation of two criteria of the efficiency of power dissipation (η) (Equation (7)) and flow instability (ξ) (Equation (8)). The η-criterion demonstrates the part of energy that dissipates in the material due to microstructural softening (dynamic recovery and dynamic recrystallization). The typical value η-criterion in Al alloys is about 10–40% in dependence of deformation parameters. The ξ-criterion describes instability of flow under the deformation. Positive value ξ-criteria mean the uniform deformation proceeds. The negative ξ-criteria predicted flow localization as potential positions for local stress concentration and crack formation.

Constructed 3D-processing maps of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys are demonstrated in Figure 5. The η-criterion with value more than 30% was obtained in wide temperature and strain rates range. The temperatures of 440–500 °C at all strain rates are mostly effective for deformation. However, the flow stability in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloy is different. The deformation of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloy at strain rates higher than 1 s−1 and temperatures of 360–410 °C may lead to the flow localization (Figure 5a). At the same time, the flow instability criterion for the Er-doped alloy has a value lower than zero only at high strain rates and temperatures of about 360 °C. The Er-containing alloy has a better forming ability than Y-containing alloy. However, both alloys demonstrated better deformation behavior than similar alloys with 3% of Zn/Mg/Cu and without Cr [30].

Figure 5.

3D-processing maps of (a) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and (b) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys (dotted lines close areas with the flow localization).

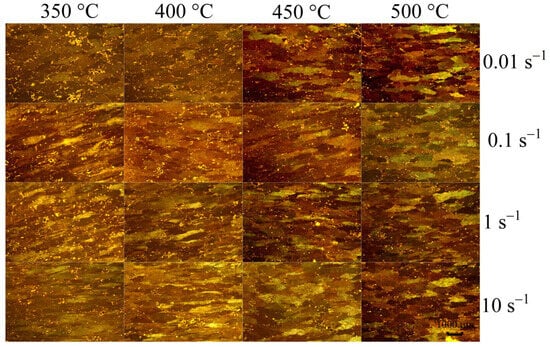

The grain structure after compression tests at temperatures of 350–500 °C and strain rates of 0.01–10 s−1 of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy is summarized in Figure 6. The deformed non-recrystallized grain structure is presented in all states. The grain structure confirms that the main softening mechanism under hot deformation is dynamic recovery.

Figure 6.

Grain structure after compression tests at temperatures of 350–500 °C and strain rates of 0.01–10 s−1 of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy (OM).

3.3. Superplastic Behavior

The presence of nano-sized Al3(Er,Y) or Al3(Er,Zr), E precipitates, and micron-sized particles of the solidification origin allows obtaining a micrograin stable microstructure in the alloys; therefore, these alloys can potentially exhibit superplasticity. The Y/Er with Cu plays the role of eutectic forming elements in new alloys; at the same time, the Y/Er with Zr are the precipitate-forming elements. As a result, the Y/Er has a major role in the superplasticity of the new alloys: it provides dynamic recovery and pinning grain growth through the formation of fine eutectic phases and fine precipitates. The alloys have an initial non-recrystallized structure. However, at temperatures above 460 °C, even with short-term annealing, recrystallization occurs in the alloys. After annealing at 460–500 °C for 20 min, the grain size in both alloys is approximately the same and equals 8.5 ± 0.8 µm (Figure 7). At subsolidus temperatures (~520 °C), the average grain size is about 10 μm [29]; therefore, the alloys can exhibit superplastic properties in the temperature range of 460–520 °C.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of (a) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and (b) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys after annealing at 460 °C for 20 min.

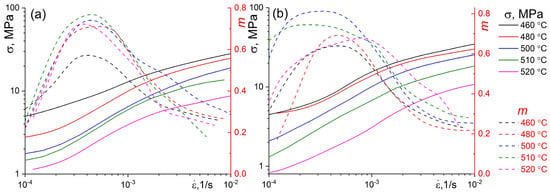

The tests were carried out using step-by-step increasing of the strain rate, and graphs of stress versus strain rate were plotted (Figure 8). Uniaxial tensile tests at elevated temperatures were performed in the range of 0.91–0.98 Tmelt. The stress–strain rate graphs have a sigmoidal shape, typical of superplastic alloys. The curves have a narrow interval belonging to region II [65]. The alloys have a strain rate sensitivity index m above 0.5, which indicates possible superplastic properties. In the alloy with erbium, the maximum value of m is ~0.83, while in the alloy with yttrium, the maximum value is ~0.79. The deformation temperature of 460 °C provides a reduced value of the m-index and cannot provide superplastic properties. The optimum temperatures are 500–510 °C for both alloys. The optimum deformation rates are 2 × 10−4–5 × 10−4 s−1, but such strain rates are not promising for industry, since they are too low. However, it is worth noting a sufficiently high value of the index m (about 0.5) at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1, which is chosen as optimal for both alloys.

Figure 8.

The stress–strain rate behavior and the strain rate sensitivity m-coefficient vs. strain rate for alloys (a) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and (b) Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr (solid lines refer to the flow stress σ, dashed lines—to the coefficient m).

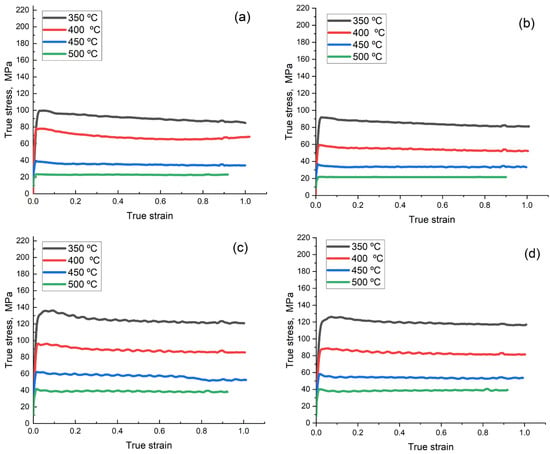

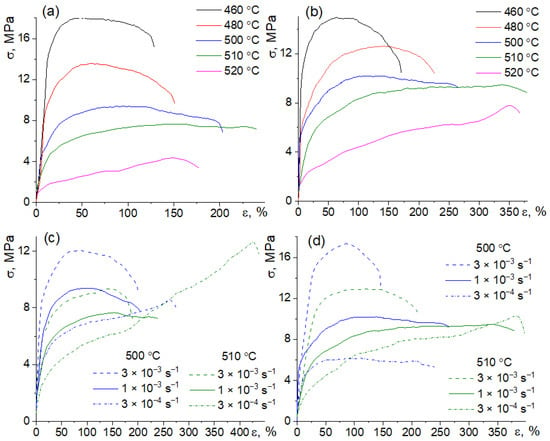

Both alloys were deformed at a constant strain rate in the temperature range of 460–520 °C (Figure 9a,b). The alloy with Y practically does not exhibit superplastic properties, since the elongation is less than 200% at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1, whereas the alloy with Er exhibits large elongations in the entire temperature range at a rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1, except for 460 °C. The maximum elongation is achieved at a temperature of 510 °C and exceeds 350% (Figure 9b). It is worth noting the increase in stress in both alloys at a subsolidus temperature of 520 °C, which is most likely associated with grain growth.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Stress–elongation curves at constant strain rate 1 × 10−3 s−1 and temperatures range 460–520 °C and (c,d) stress–elongation curves at constant strain rate range of 3 × 10−4–3 × 10−3 s−1 and temperature range of 500–510 °C for the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr (a,c) and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr (b,d) alloys.

The maximum of the strain rate sensitivity index m for alloys is observed at a strain rate of 3 × 10−4 s−1 (Figure 9c,d). To determine the limiting properties of alloys at optimal temperatures of 500–510 °C, the alloys are deformed at a low strain rate of 3 × 10−4 s−1 and an order of magnitude higher 3 × 10−3 s−1.

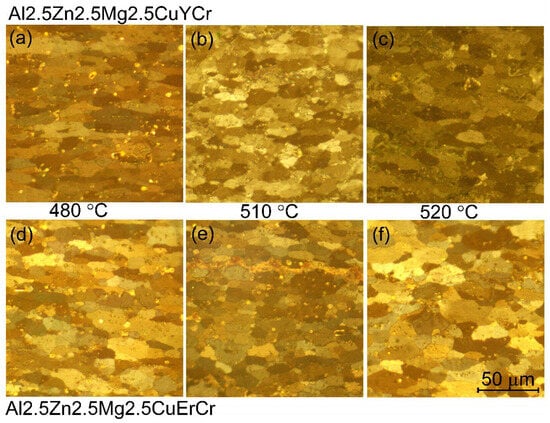

The alloy with yttrium exhibits weak superplasticity in the entire temperature-strain rate range. The best properties (450%) are achieved at 510 °C and a low speed of 3 × 10−4 s−1; however, due to the long deformation time, a large grain growth is possible according to the increase in stress on the deformation curve. The alloy with erbium is not superplastic at deformation rates above 1 × 10−3 s−1, but at lower strain rates it exhibits elongations of about 350%, with the same flow stress as the alloy with yttrium. The presence of dispersoids in the alloy structure slows down grain growth, but the initial nonequilibrium grains in the alloy with yttrium do not allow obtaining good superplastic properties that are present in the alloy with erbium. The grain structure of alloys after superplastic deformation at a rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 in the temperature range of 480–520 °C was studied (Figure 10). The grain size in the alloy with Y is 15.3 ± 1.6 μm (Figure 10a), while in the alloy with Er it is 12.0 ± 1.2 μm (Figure 10d) after deformation at low temperatures of 480 °C. The grain size increases after deformation at 500–510 °C to 12.7 ± 1.4 μm and 11.3 ± 1.5 μm in the alloys with Y and Er, respectively (Figure 10b,e). The grain size is 15.6 ± 2.4 µm and 12.7 ± 1.3 µm in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys at subsolidus temperature of 520 °C, respectively. However, it is worth noting the high proportion of residual porosity in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloy. After superplastic deformation, the grain size in the alloys increases, but equiaxed grains are preserved, indicating the significant role of the Zener pinning effect of the precipitates. The grain size in the alloy with Y is slightly larger than in the alloy with Er across the entire temperature range at a deformation rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1. However, the residual porosity is significantly different, amounting to 5.5% and 1.4% in the Y and Er containing alloys, respectively, after deformation at the highest temperature of 520 °C. The hardness of the Y- and Er-rich alloys before superplasticity tests is 158 and 163 HV, respectively. The hardness decreases to 142 and 148 HV after deformation at 510 °C, confirming lower porosity and grain size in the Er-containing alloy.

Figure 10.

Grain structure after superplastic deformation (failure) at temperatures of 480–520 °C and strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 of the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr (a–c) and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr (d–f) alloys (OM).

Obvious differences in the superplastic behavior of alloys are possible due to differences in the dominant mechanism during superplastic deformation. One indirect method for determining the main mechanism of superplastic deformation is the analysis of effective activation energy. The data of the linear region II (Figure 8) were used not only to estimate the stress exponent but also the effective activation energy of superplastic deformation. The strain rate-sensitivity index m is an indirect method for assessing the mechanisms of superplastic deformation. The main contributions are believed to come from grain boundary sliding m = 0.5, dislocation climb m = 0.2–0.3, and diffusion creep m = 1. The combination of these independent mechanisms also provides a value of m close to 0.5. In both alloys, m-values are 0.6–0.8, indicating a low contribution from the dislocation component. However, it is difficult to determine which mechanism is dominant based on the m-values. Therefore, calculation of the effective activation energy is preferred, which allows one to determine the contribution of the main mechanism of superplastic deformation. It is known that during superplastic deformation, the values of the main mechanism and Q can be changed. For the calculation, a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 was chosen, which corresponds to region II of deformation. At the initial strain, it is difficult to determine the main deformation mechanism, as there is a strong increase in stress due to microstructural changes. Accordingly, the effective activation energy was calculated at a strain greater than 100% (the steady deformation stage), when there is no change in stress for both alloys. Effective activation energy is calculated using Equation (1). It is known from the literature that the most informative and least error-prone method is the calculation of the activation energy using Equation (2) using the hyperbolic sine. The effective activation energy determined by Equation (2) is a critical parameter for determining the level of complexity for possible superplastic deformation of materials at high temperatures. In the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy, the activation energy is ~128 ± 10 kJ/mol, while in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloy, it is ~220 ± 17 kJ/mol. During superplastic deformation of aluminum alloys, if the Q value is 84 kJ/mol [65,66,67], the process is controlled by grain boundary diffusion, i.e., grain boundary sliding. If the Q value is near lattice diffusion ~142 kJ/mol [65,66,67], then the deformation is controlled by self-diffusion of pure aluminum. The Q in alloy with Er lies between the grain boundary and lattice self-diffusion activation energy of pure Al [67,68]. The results show that there are both grain boundary self-diffusion and lattice self-diffusion during deformation in Er-doped alloy, whereas in the Y-doped alloy the value of Q is high and the predominant mechanism that controlled the superplastic flow is diffusion creep. High values can be explained by the influence of alloying elements and second-phase particles on the diffusion characteristics of the alloy. Diffusion creep is a slow process, which limits the strain rate and possibility of superplastic deformation. After annealing, equiaxed grains were observed in both alloys due to the PSN effect of the coarse particles, which facilitate dynamic recrystallization. However, a comparison of the behavior during superplastic deformation and the effective activation energy suggests that the second-phase particles and/or the excessively dissolved element Y had a strong influence on the recrystallization behavior, slowing grain boundary sliding. Diffusion creep occurs simultaneously with grain boundary sliding in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy. The deformation process is accompanied by sliding of the adjacent grains along grain boundaries, grain rotation, and grain neighbor switching. Due to better accommodation and the action of two deformation mechanisms, the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy has lower residual porosity and lower stress during deformation, which is also associated with a smaller grain size. The elongation of the grains along the tensile axis, usually associated with Lifshitz sliding, occurs due to the diffusion creep mechanism, which is consistent with the grain size; in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloy, it is larger.

Activation energy values for industrial alloys vary depending on their composition. For example, for AA5083, it is around 200 kJ/mol [69], while in high-strength alloys (AA7475), it is around 112 kJ/mol [70], indicating the presence of different deformation mechanisms. Presumably, the AA5083 alloy and AA7475 exhibit high values relative to the self-diffusion of pure aluminum due to the distortion of the crystal lattice during the formation of the solid solution and the presence of dispersed particles with a size of approximately 40 nm. Low Q values are not found in industrial alloys but are possible in alloys with a non-recrystallized microstructure prior to fracture.

The Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy has properties close to [59] but has two times less the amount of main alloying elements (which reduces the cost of the alloy) and less energy-intensive technology for obtaining a micrograin structure in the sheet with good properties, including superplastic ones. The unusual Al-4.91Mg-3.46Zn-0.46Cu-0.33Mn-Cr-Fe-Si crossover alloy was investigated in [59]. The typical structure for achieving good superplasticity was provided by micron-sized T phase and E(Al18Mg3Cr2) precipitates. Similar elongation was achieved in the Al-4.91Mg-3.46Zn-0.46Cu-0.33Mn-Cr-Fe-Si crossover alloy in the wide range of strain rates of 10−2 s−1 or 5·10−5 s−1.

The developed and studied Er-doped alloy is promising for industrial use in superplastic forming, as it exhibits sufficient elongations (>350%) at 510 °C and a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1. For industrial applications, deformation at lower temperatures and higher strain rates is preferable. The AA5083 and AA7475 alloys used in industry are deformed at subsolidus temperatures (500–550 °C) and at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1, but the maximum elongation is near 300% with same thermomechanical treatment [69,70]. Increasing the strain rate is preferable to decreasing the temperature. Therefore, grain size reduction in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr alloys can be achieved using multi-directional isothermal forging as a promising method for grain refinement and increasing superplastic properties (with a smaller grain size, it is possible to change the temperature-strain rate regime).

4. Conclusions

The aim of the work was achieved: the systematic investigation of the precipitation behavior in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuYCr and Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloys and effect of strain on microstructure evolution and superplastic properties were performed. The microstructure of the alloys is presented by nano-sized precipitates and micron-sized particles of the solidification origin. The superplastic deformation behaviors were investigated under different temperatures and different strain rates under uniaxial tension. Despite the insignificant difference in the mechanical properties and similar initial microstructure, the superplastic properties in the alloys differ significantly. The alloy with yttrium practically does not exhibit superplastic properties, while the alloy with the addition of erbium exhibits good superplastic properties. The main scientific results can be written as follows:

Two types of precipitates were identified in the Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy after two-step solution treatment at 480 + 520 °C. The near-spherical precipitates with a diameter of about 20 nm were identified as D023-Al3(Er,Zr). The rod-like E (Al18Mg3Cr2) precipitates with thickness about 20 nm and a length of about 150–200 nm were also found. E precipitates are presented in crystalline and quasicrystalline states.

The investigated alloys demonstrated excellent deformation behavior at strain rates of 10−2–10 s−1 at temperatures of 440–500 °C based on the analyzes of stress–strain dependencies and 3D-processing maps construction. The grain structure investigation after compression tests confirms that the main softening mechanism under hot deformation is dynamic recovery.

The peak stress in both alloys decreased with strain rate decreasing and with deformation temperature increasing. However, only Al2.5Zn2.5Mg2.5CuErCr alloy has micrograin structure with elongation of more than 350% during superplastic deformation at a rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 and temperature of 510 °C. Furthermore, the calculation of m-values and deformation activation energy indicates that grain boundary sliding is the predominant deformation mechanism, which allows obtaining high superplastic properties. The age-hardened alloy with Er have mechanical and deformation properties at the level of the 7xxx series aluminum alloys with a high volume fraction of fine second phase particles, which are widely used in the aerospace industry but have a wider application and lower cost.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.P., M.G.K. and O.A.Y.; methodology, M.G.K., M.V.G. and R.Y.B.; software, M.G.K. and R.Y.B.; validation, A.V.P., M.G.K., M.V.G., R.Y.B. and O.A.Y.; formal analysis, M.G.K., M.V.G. and R.Y.B.; investigation, M.V.G., R.Y.B. and A.V.P.; resources, M.G.K. and R.Y.B.; data curation, M.G.K., R.Y.B., A.V.P. and M.V.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.P., M.G.K., M.V.G., R.Y.B. and O.A.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.V.P., R.Y.B. and O.A.Y.; visualization, A.V.P., M.G.K. and O.A.Y.; supervision, A.V.P.; project administration, R.Y.B.; funding acquisition, M.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by Russian Science Foundation project N° 22-79-10142-П, https://rscf.ru/project/22-79-10142-П (accessed on 2 December 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University Program of Development in part of hardness measurements (hardness tester DuraScan 20 G5 Emco-Test).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ASM International Handbook Committee. Properties and selection–nonferrous alloys and special-purpose materials. In ASM Handbook; ASM International: Metals Park, OH, USA, 2001; Volume 2, ISBN 0871700077. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotorevsky, V.S.; Belov, N.A.; Glazoff, M.V. Casting Aluminum Alloys; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 9780080453705. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Hu, A.; Liu, S.; Hu, H. Al-Mn alloys for electrical applications: A review. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2023, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, W.; Kooi, B.J.; Pei, Y. Eutectic aluminum alloys fabricated by additive manufacturing: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 250, 123–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-G. Recent advances in cost-effective aluminum alloys with enhanced mechanical performance for high-temperature applications: A review. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Hu, P. A new synergy to overcome the strength-ductility dilemma in Al-Si-Cu alloy by adding AlZrNiTi master alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 915, 147213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Guo, D.; Zhang, K.; Tzanakis, I.; Leung, C.L.A.; Lee, P.D.; Eskin, D. A New Approach to the Design of Al Alloys with Low Cracking Susceptibility and High-Temperature Strength for Cast and Additive Manufacturing. In Light Metals 2025; TMS 2025. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.M.; Glavatskikh, M.V.; Barkov, R.Y.; Khomutov, M.G.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Phase composition and mechanical properties of Al-Si based alloys with Yb or Gd addition. Mater. Lett. 2022, 320, 132320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopyan, T.K.; Belov, N.A.; Alabin, A.N.; Zlobin, G.S. Calculation-experimental study of the aging of casting high-strength Al-Zn-Mg-(Cu)-Ni-Fe aluminum alloys. Russ. Metall. 2014, 2014, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodova, I.G.; Shirinkina, I.G.; Rasposienko, D.Y.; Akopyan, T.K. Structural Evolution in the Quenched Al–Zn–Mg–Fe–Ni Alloy during Severe Plastic Deformation and Annealing. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2020, 121, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatskikh, M.V.; Konovalova, S.M.; Chubov, D.G.; Khomutov, M.G.; Barkov, R.Y.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Novel cast heat resistant crossover Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Y-Zr-Cr alloy with improved corrosion and wear behavior, and low thermal expansion. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1033, 181286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdniakov, A.V.; Zolotorevskiy, V.S.; Mamzurina, O.I. Determining hot cracking index of Al–Mg–Zn casting alloys calculated using effective solidification range. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2015, 28, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, B.; Shen, G.; Liu, M.; Jiang, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Chao, Z.; Chen, G. Hot deformation behavior and microstructural evolution of a new type of 7xxx Al alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.D.; Foley, R.D.; Griffin, J.A.; Monroe, C.A. Microstructural Characterization and Thermodynamic Simulation of Cast Al–Zn–Mg–Cu Alloys. Int. J. Met. 2016, 10, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopyan, T.K.; Belov, N.A.; Letyagin, N.V.; Sviridova, T.A.; Cherkasov, S.O. New quaternary eutectic Al-Cu-Ca-Si system for designing precipitation hardening alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 993, 174695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, P.; Xue, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Review of Sc microalloying effects in Al–Cu alloys. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopyan, T.K.; Belov, N.A.; Sviridova, T.A.; Letyagin, N.V.; Solovev, I.S.; Cherkasov, S.O. New quaternary Al-Cu-Ca-Fe system utilizing iron for designing precipitation hardening alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.M.; Barkov, R.Y.; Prosviryakov, A.S.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Structure and Properties of New Wrought Al–Cu–Y- and Al–Cu–Er-Based Alloys. Phys. Metals Metallogr. 2021, 122, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C.; Olivetti, E.A. Strategies for improving the sustainability of structural metals. Nature 2019, 575, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemper, L.; Tunes, M.A.; Tosone, R.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Pogatscher, S. On the potential of aluminum crossover alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 124, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. Effect of high Cu concentration on the mechanical property and precipitation behavior of Al–Mg–Zn-(Cu) crossover alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4585–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, G.; Gu, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, J. Composition optimization and mechanical properties of Al–Zn–Mg–Si–Mn crossover alloys by orthogonal design. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 307, 128216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. A novel Al-Mg-Zn(-Cu) crossover alloy with ultra-high strength. Mater. Lett. 2023, 347, 134640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Meng, L.; Chen, Z.; Gong, W.; Sun, B.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D. The influence of precipitation on plastic deformation in a high Mg-containing AlMgZn-based crossover alloy: Slip localization and strain hardening. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 173, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trink, B.; Weißensteiner, I.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Strobel, K.; Hofer-Roblyek, A.; Pogatscher, S. Processing and microstructure–property relations of Al-Mg-Si-Fe crossover alloys. Acta Mater. 2023, 257, 119160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hao, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. Modifying the microstructure and stress distribution of crossover Al-Mg-Zn alloy for regulating stress corrosion cracking via retrogression and re-aging treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 884, 145564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Liu, Z.; Qin, J.; Wei, Q.; Wang, B.; Yi, D. Enhanced corrosion performance by controlling grain boundary precipitates in a novel crossover Al-Cu-Zn-Mg alloy by optimizing Zn content. Mater. Charact. 2024, 208, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatskikh, M.V.; Barkov, R.Y.; Gorlov, L.E.; Khomutov, M.G.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Novel Cast and Wrought Al-3Zn-3Mg-3Cu-Zr-Y(Er) Alloys with Improved Heat Resistance. Metals 2023, 13, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatskikh, M.V.; Barkov, R.Y.; Gorlov, L.E.; Khomutov, M.G.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Microstructure and Phase Composition of Novel Crossover Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr-Y(Er) Alloys with Equal Zn/Mg/Cu Ratio and Cr Addition. Metals 2024, 14, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatskikh, M.V.; Gorlov, L.E.; Loginova, I.S.; Barkov, R.Y.; Khomutov, M.G.; Churyumov, A.Y.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Effect of Er on the Hot Deformation Behavior of the Crossover Al3Zn3Mg3Cu0.2Zr Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.-S.; Zhao, P.-Y.; Gu, Y.-C.; Zhang, L.; Shi, X.-B.; Chen, L.-L. Aging temperature regulating the precipitation-hardening behavior of new crossover Al-8Zn-5Mg-0.3Si alloys. Vacuum 2025, 233, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerchikova, N.S.; Fridlyander, I.N.; Zaitseva, N.I.; Kirkina, N.N. Change in the structure and properties of Al-Zn-Mg alloys. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 1972, 14, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wu, X.; Tang, S.; Zhu, Q.; Song, H.; Guo, M.; Cao, L. Investigation on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys with various Zn/Mg ratios. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 85, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, J. Precipitation hardening and intergranular corrosion behavior of novel Al–Mg–Zn(-Cu) alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 853, 157199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.-T.; Chen, S.-J.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Shen, B.-K.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Ye, L.-Y. Microstructural evolution and deformation mechanisms of superplastic aluminium alloys: A review. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 3069–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylovskaya, A.V.; Kishchik, A.A.; Kotov, A.D.; Rofman, O.V.; Tabachkova, N.Y. Precipitation behavior and high strain rate superplasticity in a novel fine-grained aluminum based alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 760, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Ding, L.; Xiang, K.; Zhuang, L. Achieving equiaxial fine grains and high superplasticity of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy by an improved thermo-mechanical treatment. Mater. Charact. 2025, 230 Part B, 115806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ye, L.; Tang, J.; Ke, B.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Gu, Y. Superplastic deformation mechanisms of a fine-grained Al–Cu–Li alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 848, 143403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zou, G.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Duan, T.; Liu, Y.; Ye, L. Effect of Rolling Schedule on Grain Refinement and Superplasticity of 7475 Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy Sheet. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 9465–9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhar, N.; Fereshteh-Saniee, F.; Mahmudi, R. High strain-rate superplasticity of fine- and ultrafine-grained AA5083 aluminum alloy at intermediate temperatures. Mater. Des. 2015, 85, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.G.; Shin, D.H.; Park, K.-T.; Lee, C.S. Superplastic deformation behavior of ultra-fine-grained 5083 Al alloy using load-relaxation tests. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 449–451, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Badheka, V. Engineering Applications of Superplasticity of Metals: Review. In Advances in Materials Engineering. ICFAMMT 2024; Bhingole, P., Joshi, K., Yadav, S.D., Sharma, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvil’dEev, V.N.; Gryaznov, M.Y.; Shotin, S.V.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Likhnitskii, K.V.; Shadrina, Y.S.; Kopylov, V.I.; Bobrov, A.A.; Chegurov, M.K. Superplasticity of Ultrafine-Grained Al–6% Mg–0.12% Sc–0.10% Zr Alloys with 0.10% Yb, Er, and Hf Additions. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2025, 16, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochugovskiy, A.G.; Chukwuma, E.U.; Mikhaylovskaya, A.V. The Effect of Multidirectional Forging on the Microstructure and Superplasticity of the Al–Mg–Si–Cu System Alloys with Different Contents of Mg and Si. Phys. Metals Metallogr. 2024, 125, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobruk, E.V.; Ramazanov, I.A.; Astanin, V.V.; Zaripov, N.G.; Kazykhanov, V.U.; Drits, A.M.; Murashkin, M.Y.; Enikeev, N.A. Low-Temperature Superplasticity of the 1565ch Al–Mg Alloy in Ultrafine-Grained and Nanostructured States. Phys. Metals Metallogr. 2023, 124, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, L.; Pesin, A.; Zhilyaev, A.P.; Tandon, P.; Kong, C.; Yu, H. Recent Development of Superplasticity in Aluminum Alloys: A Review. Metals 2020, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieh, T.G.; Wadsworth, J.; Sherby, O.D. Superplasticity in Metals and Ceramics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Langdon, T.G. Developing Superplasticity in Ultrafine-Grained Metals. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2015, 128, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Infanta, J.M.; Zhilyaev, A.P.; Sharafutdinov, A.; Ruano, O.A.; Carreño, F. An evidence of high strain rate superplasticity at intermediate homologous temperatures in an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy processed by high-pressure torsion. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 473, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, Z.; Furukawa, M.; Nemoto, M.; Barnes, A.J.; Langdon, T.G. Superplastic forming at high strain rates after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Utsunomiya, A.; Akamatsu, H.; Neishi, K.; Furukawa, M.; Horita, Z.; Langdon, T.G. Influence of scandium and zirconium on grain stability and superplastic ductilities in ultrafine-grained Al–Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolej, A.; Skaza, B.; Markoli, B.; Klobčar, D.; Dragojević, V.; Slaček, E. Superplastic Behaviour of AA5083 Aluminium Alloy with Scandium and Zirconium. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2012, 709, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chentouf, S.M.; Belhadj, T.; Bombardier, N.; Brodusch, N.; Gauvin, R.; Jahazi, M. Influence of predeformation on microstructure evolution of superplastically formed Al 5083 alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 2929–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Li, Q.S.; Wu, R.R.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ma, L. A Review on Superplastic Formation Behavior of Al Alloys. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samberger, S.; Weißensteiner, I.; Stemper, L.; Kainz, C.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Pogatscher, S. Fine-grained aluminium crossover alloy for high-temperature sheet forming. Acta Mater. 2023, 253, 118952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backofen, W.A. Turner, I.R.; Avery, D.H. Superplasticity in an Al-Zn alloy. Trans. Am. Soc. Met. 1964, 57, 980–990. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Wan, M.; Li, W.; Shao, J.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J. Superplastic deformation mechanical behavior and constitutive modelling of a near-α titanium alloy TNW700 sheet. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 817, 141419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, H.; He, W.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Volodymyr, S.; Shcheretskyi, O. Study on the microstructure and mechanical properties of hot rolled nano-ZrB2/AA6016 aluminum matrix composites by friction stir processing. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Li, C.; Qian, F.; Hao, L.; Li, Y. Diffusion controlled early-stage L12-D023 transitions within Al3Zr. Scr. Mater. 2023, 231, 115460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhao, M.; Ehlers, F.J.H.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, Y.; Schryvers, D.; Liu, Q.; Idrissi, H. “Branched” structural transformation of the L12-Al3Zr phase manipulated by Cu substitution/segregation in the Al-Cu-Zr alloy system. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 185, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhao, L.; Weng, Y.; Schryvers, D.; Liu, Q.; Idrissi, H. Atomic-scale investigation of the heterogeneous precipitation in the E (Al18Mg3Cr2) dispersoid of 7075 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 851, 156890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J.W. Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zener, C.; Hollomon, J.H. Effect of strain rate upon plastic flow of steel. J. Appl. Phys. 1944, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Y.V.R.K.; Gegel, H.L.; Doraivelu, S.M.; Malas, J.C.; Morgan, J.T.; Lark, K.A.; Barker, D.R. Modeling of dynamic material behavior in hot deformation: Forging of Ti-6242. Metall. Trans. A 1984, 15, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.A.; Todd, R.I. Surface studies of Region II superplasticity of AA5083 in shear: Confirmation of diffusion creep, grain neighbour switching and absence of dislocation activity. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 5159–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, E.A.; Brook, G.B. Smithells Metals Reference Book; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1992; p. 1794. [Google Scholar]

- Ruano, O.A.; Sherby, O.D. On constitutive equations for various diffusion-controlled creep mechanisms. Rev. Phys. Appl. 1988, 23, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ye, L.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y. Achieving high strain rate superplasticity in an Al-Cu-Li alloy processed by thermo-mechanical processing. Mater. Lett. 2023, 340, 134142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovtseva, O.A.; Mikhaylovskaya, A.V.; Levchenko, V.S.; Irzhak, A.V.; Portnoy, V.K. Study of the mechanisms of superplastic deformation in Al–Mg–Mn-based alloys. Phys. Metals Metallogr. 2015, 116, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylovskaya, A.V.; Yakovtseva, O.A.; Sitkina, M.N.; Kotov, A.D.; Irzhak, A.V.; Krymskiy, S.V.; Portnoy, V.K. Comparison between superplastic deformation mechanisms at primary and steady stages of the fine grain AA7475 aluminium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 718, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).