Abstract

This work deals with the optimization of crucial process parameters related to the abrasive flow machining applications at micro/nano-levels. The optimal combination of abrasive flow machining parameters for nano-finishing has been determined by applying a modified virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm. This algorithm implements two populations: One comprising the hosts and one comprising the viruses. Viruses act as information carriers and thus they contribute to the algorithm by boosting efficient schemata in binary coding to facilitate both the arrival at global optimal solutions and rapid convergence speed. Three cases related to abrasive flow machining have been selected from the literature to implement the algorithm, and the results corresponding to them have been compared to those available by the selected contributions. It has been verified that the results obtained by the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm are not only practically viable, but far more promising compared to others as well. The three cases selected are the traditional “abrasive flow finishing,” the “rotating workpiece” abrasive flow finishing, and the “rotational-magnetorheological” abrasive flow finishing.

1. Introduction

The modern manufacturing industry faces the continuous challenge of delivering high-quality products with special properties, achieving high productivity rates as well as stringent tolerance requirements. The research question on how to deliver these elements when it comes to miniature products is of special interest. Even though new machining equipment has come to improve production lines, process performance is still on the able hands and expertise of engineers who are to judge the influence of related process parameters and examine the most advantageous settings to meet the requirements.

Abrasive flow machining (AFM) is a nonconventional machining process mainly applied to finishing operations. Its applications span a number of processes such as the finishing of inaccessible surface areas and free-form profiles, as well as deburring and polishing radii, existing in parts’ corners [1]. Surface roughness after applying AFM is reduced by 70% to 90% when it comes to cast and machined parts. In addition, it can simultaneously process a large number of inner holes found in products by achieving a uniform surface finish. The material used for finishing parts is a semi-solid, self-deformable stone in the form of an abrasive medium. This material is applied in small quantities to remove the excess material forming the part’s surface through back and forth motions of the two cylinders that constitute the main tooling devices in the AFM apparatus. The parameters responsible of controlling the AFM process are the medium’s flow speed, the percentage concentration of the medium, its mesh size, and the number of cycles executed to achieve the final surface finish. In addition, the piston velocity is also a factor that can be controlled depending on the experiment and application. Noticeable contributions dedicated to AFM and its related optimization research efforts are the work of Jain and Jain (2000) [2], Sankar et al., (2009) [3], and Das et al., (2012) [4]. In these contributions, a number of selected process parameters are treated in the form of independent variables to optimize responses not only related to surface finish, but to productivity as well (i.e., material removal rate—MRR). It should be noted that AFM is found under a variety of process-assisted alternatives such as ultrasonic-assisted AFM [5], magnetic abrasives-assisted AFM [6], and electrochemical-aided abrasive flow finishing (ECA2FM) [7] to name a few. Other important advances in abrasive machining techniques forming a research perspective are presented in references [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Researchers have tried to study and optimize the variants of the AFM process by adopting different methodologies. Some of them are based on the application of neural networks [2,17,18], optimization algorithms [2,19], and fuzzy logic [20]. Undoubtedly, genetic, evolutionary, and swarm-based intelligent algorithms constitute the most often-implemented elements for optimizing an engineering process. These algorithms follow either the standard operational principles of genetic/evolutionary algorithms, or the principles of swarm intelligence. Each of these algorithmic variants implements a number of algorithm-specific parameters to be set to achieve the optimal outputs. The genetic algorithm implements crossover and mutation operators to produce new candidate solutions and facilitate their spread. Differential evolution implements the scaling factor to arrive at the same optimization goal as genetic algorithms do; particle swarm optimization embodies inertia weight, social cognitive variables, as well as maximum velocity of particles, and so on.

This paper differentiates its research content from previous similar studies, by proposing a virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm to optimize the control parameters of a selected group of nano-finishing operations related to the abrasive flow machining (AFM) process. The novelty of the research lies mainly in the optimization concept using a nonconventional artificial intelligence system based on the viral intelligence. In addition, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, intelligent optimization proposals for optimizing crucial parameters when it comes to abrasive flow nano-finishing operations are yet to be presented. The proposed algorithm adheres to the “virus theory of evolution” [21], which is an entirely different evolution theory form proposed by Darwin. According to this theory, physical/natural viruses can not only exchange their genetic information by adopting genetic material from their hosts but also be transferred from phylum to phylum both vertically (vertical inheritance) and horizontally (horizontal propagation) [22]. The improved virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm presented in the paper can be applied to both single (VEGA) and multi-objective (MOVEGA) optimization problems related to engineering and manufacturing. In this work, the first and the second AFM cases selected for parameter optimization are of a single-objective optimization nature, whilst the third one is of a two-objective optimization nature. The results obtained by this improved and novel algorithmic variant not only have been found reasonable to control all selected AFM processes, but also seem to be optimal ones by taking into account the original experimental results from the contributions adopted, as well as their trends in terms of main effects among influential parameters, as well as their interactions. In addition, the results obtained have been compared to the available ones according to the selected AFM case. From the three AFM cases selected, the regression equations have been adopted to be incorporated with the proposed algorithm’s functions and routines to be evaluated as objective functions with the same constraints (where applicable), the same operational ranges, and the same evaluation perspectives (i.e., number of iterations, population size, etc.).

2. The Virus-Evolutionary Genetic Algorithm (VEGA)

As pure stochastic search systems, evolutionary algorithms are inevitably based on the concept of natural selection, thus inheriting the benefits but also the drawbacks characterizing it. Other evolutionary theories such as the “virus theory of evolution” [21] suggest that natural selection may not always be responsible for the evolution of species. The virus theory of evolution lies thoroughly on the concept suggesting that viral transduction is a major mechanism for transferring DNA segments across species. Viral transduction represents the mechanism of the genetic modification that occurs to bacteria by genomes taken from other bacteria through a bacteriophage. Most viruses can cross species’ bounds whilst they can straightforwardly be transmitted from phylum to phylum among individuals. This means that viruses can pass over their genome to a population as horizontal propagation. In addition, a viral genome may exist in germ cells; thus, it can be transferred from generation to generation as vertical inheritance. For simulation experiments related to engineering problems, viral individuals might as well act as intelligent, sophisticated information carriers (“hill climbers”) capable of providing the necessary local information to contribute to the optimization problem. The functions integrating the infrastructure of the proposed single/multi-objective virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm (VEGA/MOVEGA) for addressing the problems related to AFM processes are undertaken to execute the following steps:

- Initialization of candidate solutions

- Objective function computation

- Ranking

- Fitness function computation

- Selection

- Crossover

- Mutation

- Viral infection

As the above steps up to mutation operator can be found in almost any algorithmic variant, only viral infection is presented here as the intelligent operation under interest.

Viral Infection

Artificial viral intelligence simulates the sophisticated mechanism of physical viruses to handle DNA information for their own benefit. Viral infection is based on transduction and reverse transcription operators where the former is used for producing a virus individual from a selected host (either targeted as an “elite” or randomly), whereas the latter is applied for infecting a population of hosts. The rationale behind this implementation is the direct handling of schemata to distinguish those being effective to the process, while deteriorating those judged as ineffective. Increasing a schema means increasing local information in a population. In addition, proportional selection operators increase all schemata including ineffective ones, as well. This in turn leads to local trapping and therefore premature convergence of the algorithm. On the contrary, viral infection handles schemata directly, thus eliminating this occurrence, and creates virus individuals as substrings of the strings that represent the hosts. Both viruses and hosts coevolve throughout the entire timespan during the evolution process. Coevolution between the populations of viruses and hosts allows one to rapidly solve optimization problems.

The strength of viral infection is represented by the parameter and is the difference in the fitness values after and before the infection of a selected host. Let be the fitness after viral infection and be the fitness before viral infection. The strength of viral infection is computed using the relation given in Equation (1).

The value obtained by Equation (1) is the difference between the two fitness values of individual before and after its infection by . Given that might infect more than a single individual (let be the set of infected individuals), then reveals the improvement in fitness values of all infected individuals, and it is as Equation (2) determines:

Every virus is also accompanied with its corresponding life force, indicating its contribution through successful infections to the main population. The life force of a virus is presented as , where is the index of the virus and is the current generation. is also dependent on the fitness of a virus and is compared to the one obtained by the virus in the previous generation. If its value is negative, then a new transduction operation is applied by to change its scheme by randomly selecting an individual. Otherwise, cuts a partially new substring from one of the successfully infected individuals for its own benefit from the evolutionary viewpoint. The magnitude of the parameter is computed in each generation with regard to an important indicator, which is the virus life reduction rate satisfying . Hence, maximum viral infection rate and virus life reduction rate are related through the relation presented in Equation (3).

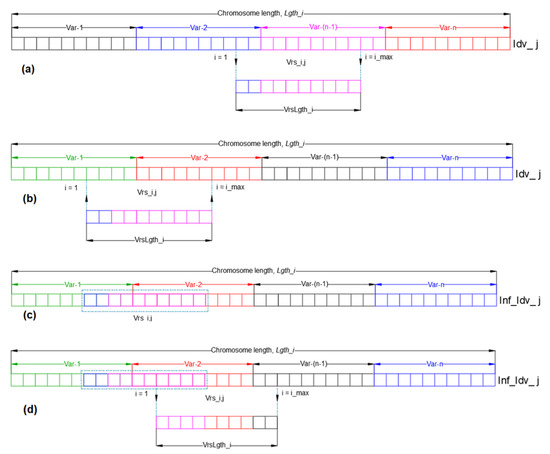

and parameters are initialized in VEGA as ,. Figure 1a illustrates the transduction operation to generate a virus individual. Figure 1b illustrates the reverse transcription to infect a selected individual. Figure 1c shows an infected host, and finally Figure 1d depicts the operation of partial transduction in the case where . The procedure of viral infection is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

(a) Transduction operation for the creation of a virus individual, (b) reverse transcription operation for infecting an individual with a virus, (c) infected individual after the reverse transcription operation performed by the virus, and (d) partial transduction operation for changing the virus scheme.

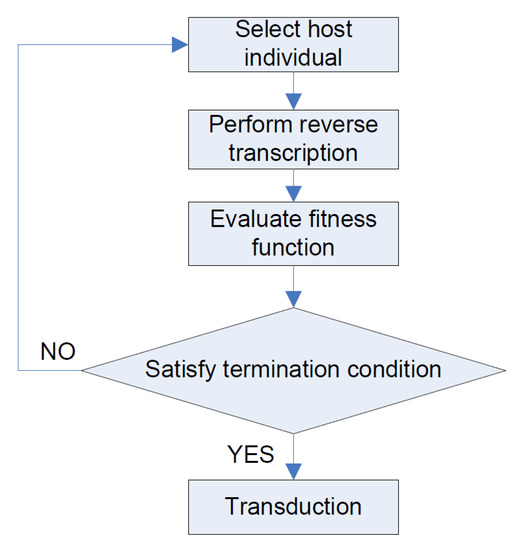

Figure 2.

The procedure of viral infection in the virus−evolutionary genetic algorithm.

3. Optimization Problems Related to Abrasive Flow Nano-Finishing Processes

The study focuses on the optimization of process parameters related to the three independent nano-finish machining processes, namely conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing, “rotating workpiece” abrasive flow nano-finishing, and rotational-magnetorheological abrasive flow nano-finishing. Parameter optimization for these nano-finish machining processes has been achieved by implementing the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm, and the results were compared to those available in the literature by other algorithms applied for solving the same optimization problems.

3.1. Conventional Abrasive Flow Nano-Finishing Process

Abrasive flow machining for nano-finishing operation is comparable to lapping or grinding and removes small material quantities by flowing semisolid abrasive medium in the form of self-deformable stone. The equipment comprises two vertically opposed cylinders to extrude the medium back and forth through sequential passes of tooling and workpiece. The process is implemented for finishing inaccessible or difficult-to-reach part surfaces. The optimization problem for optimizing the parameters for conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing has been formulated by considering the experimental results available in [2]. Maximum material removal rate, MRR (mg/min), and minimum surface roughness, Ra (μm), have been set as the two objectives for simultaneous evaluations, whilst surface roughness, Ra (μm), has been constrained to four different values, 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, and 0.4 (μm), in the form of an inequality constraint, i.e., g(x) = Ra ≤ Ramax, to better examine the convergence behavior in the case of the contradicted objective of material removal rate, MRR, when subjected to these discrete Ra values. The independent variables and their operational ranges are exactly those examined in [2], and are the piston velocity U (cm/min), percentage concentration for abrasives C, abrasive mesh size D, and number of cycles, N. Percentage concentration C has been defined as the weight ratio of abrasives and total weight of abrasive medium (abrasives and carrier) × 100. Table 1 gives the main process parameters and their experimental levels as examined in [2].

Table 1.

Parameter design for the experiments [2].

The exponential regression models for maximizing MRR and minimizing Ra given by Jain and Adsul (2000) [23] were considered the objective functions, as it is recommended in Jain and Jain (2000) [2]. The models are given in Equations (4) and (5) for maxMRR and minRa, respectively. Note that a constraint requirement was defined for minRa, as: minRa ≤ Ra_max for Ra_max = 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, and 0.4 (μm).

maxMRR = −(5.285 × 10−7 × U1.6469 × C3.0776 × D−0.9371 × N−0.1893)

minRa = 282,751 × U−1.8221 × C−1.3222 × D0.1368 × N−0.2258

Jain and Jain (2000) [2] optimized the process parameters of conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing by implementing a genetic algorithm (GA). The settings for their GA involved a population size equal to 50, and maximum number of generations equal to 200, thus 10,000 function evaluations. The selected algorithms were tested under equal parameters, i.e., 50 agents and 200 generations. Note that various values were simulated in terms of population size and other algorithm-specific parameters during the preliminary simulations using the algorithms selected for optimization. Algorithms were simulated using MATLAB® 2014b in Dell® Precision 7510 workstation. The results obtained by implementing the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm are summarized in Table 2. The results take into account the various constraints for surface roughness, i.e., 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, and 0.4 μm. Table 3 summarizes the comparative results between those obtained by the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm and the GA applied by Jain and Jain (2000) [2] for solving the same problem.

Table 2.

Optimal pairs of conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing process parameters obtained using the single-objective virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm (VEGA).

Table 3.

Optimal pairs of conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing process parameters obtained using VEGA.

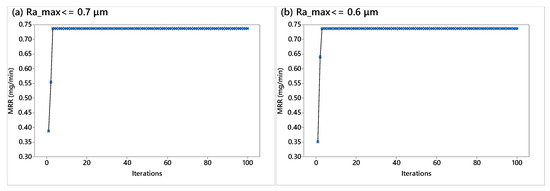

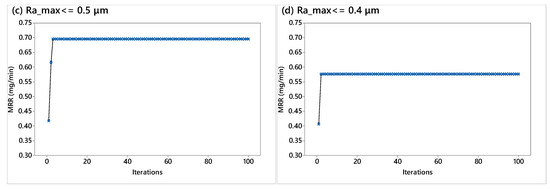

According to the results presented n Table 2 and Table 3, it is evident that VEGA has exhibited superiority against the GA in terms of maximizing MRR while minimizing Ra, according to the operation range of process parameters and the constrained values suggested for Ra_max. The maxMRR gain by implementing the proposed algorithm has been found equal to approximately 5.56%, 5.83%, 3.74%, and 0.52% compared to the values corresponding to GA results for maxMRR for the constrained values of Ra_max equal to 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, and 0.4 μm, respectively. The VEGA obtained its optimal recommended results for MRR in the 3rd generation for the constrained values of Ra_max equal to 0.7, 0.6, and 0.5 μm, whilst for Ra_max ≤ 0.4 μm, the algorithm obtains its maximum MRR value in the 2nd generation. This implies that the VEGA can find the optimal result for MRR with significantly fewer candidates, as well as less generations. Note that this behavior has been extensively examined after running a series of simulation runs to examine the stochastic nature of the VEGA. Figure 3 illustrates the convergence diagrams for the VEGA in the four cases of constrained surface roughness values.

Figure 3.

Convergence graphs for optimizing the conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing process [2] using VEGA, under the constraint of: (a) Ra_max ≤ 0.7 μm, (b) Ra_max ≤ 0.6 μm, (c) Ra_max ≤ 0.5 μm, and (d) Ra_max ≤ 0.4 μm.

It can be observed that in all four cases, the algorithms exhibit a stable increase without giving the impression of local trapping. In all four diagrams, the algorithm reaches its best value and then remains stable until the algorithms stop their evaluations. Despite the fact that 200 iterations have been simulated, only 100 have been plotted in the diagrams owing to the fast algorithmic convergence and better visualization. The results have been plotted in same scale for the maxMRR increase and number of iterations for clear and rigorous comparisons.

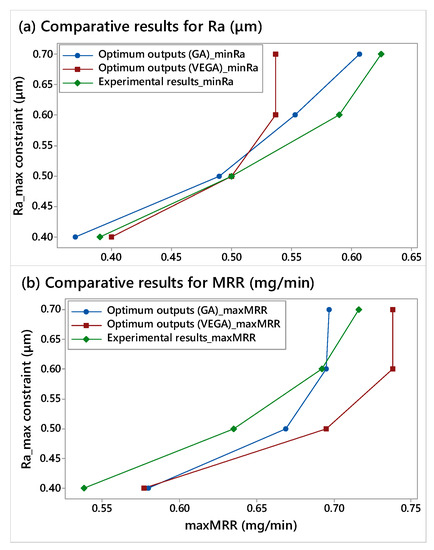

Table 4 summarizes the results obtained by GA [2], VEGA, and actual experimental results retrieved by confirmation experiments conducted and presented in [2]. Figure 4 presents a graphical depiction of the optimization trends among minRa and maxMRR objectives by considering the different constrained values for maxRa.

Table 4.

Comparison of minRa and maxMRR among genetic algorithm (GA), multi-objective virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm (MOVEGA), and actual experimental results for the conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing process examined in [2].

Figure 4.

Comparative results between the optimization objectives of minRa and maxMRR corresponding to GA, VEGA, and actual experimental results of conventional abrasive flow nano-finishing process [2]: (a) minRa, (b) maxMRR.

By examining the results presented in Figure 4a,b with reference to Table 4 for minRa and maxMRR, respectively, it can be observed that VEGA exhibits a better adaptation in the trends of actual experimental data. In addition, VEGA favors minRa results, especially under larger constraints for the same objective, as Figure 4a depicts. At the same time, when the Ra_max objective is not restricted to low values (i.e., 0.4 and 0.5 μm), maxMRR is greatly increased beyond the results recommended by GA. This supports the overall conclusion that VEGA is capable of obtaining maximum results for MRR while keeping Ra as low as possible for the same experimental solution domain.

3.2. Rotating Workpiece Abrasive Flow Nano-Finishing Process

Providing rotary motion to the work piece during the abrasive flow machining assists in reducing the time of finishing, especially when it comes to nano levels. The experimental results provided by Sankar et al. (2009) in [3] have been examined in this case in order to formulate an optimization problem referring to the rotating work piece abrasive flow nano-finishing. The optimization objective of this problem is to maximize the improvement in surface finish ΔRa (μm) in the rotating workpiece abrasive flow nano-finishing process. The independent process parameters have been identified as the processing oil wt% in medium M, the extrusion pressure P (MPa), the number of cycles N, and the rotational speed n (rpm). The parameters were subjected to the following ranges: 7.0 ≤ M ≤ 13.0, 5.35 ≤ P ≤ 7.15, 372 ≤ N ≤ 728, and 2 ≤ n ≤ 10. Sankar et al. (2009) [3] did not try to optimize the process using an intelligent system; yet, they thoroughly examined the experimental results, as well as their corresponding statistical outputs. This variant of abrasive flow nano-finishing [3] was applied to three aluminum-based alloys for which a regression model was generated to correlate the independent parameters to the objective of improvement in surface finish maxΔRa (μm). The three alloys were the pure aluminum alloy, the aluminum alloy/SiC10%, and the aluminum alloy/SiC15%. The models for maxΔRa corresponding to each of the three materials are given in Equations (6)–(8), respectively.

maxΔRaAluminum =

−(0.098 × M + 0.875 × P + 0.002 × N + 0.05 × R − 0.006 × M2 − 0.068 × P2 − 9.6 × 10−7 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

−(0.098 × M + 0.875 × P + 0.002 × N + 0.05 × R − 0.006 × M2 − 0.068 × P2 − 9.6 × 10−7 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

maxΔRaAluminum/SiC10% =

−(0.118 × M + 0.831 × P + 0.001 × N + 0.031 × R − 0.006 × M2 − 0.067 × P2 − 1.2 × 10−6 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

−(0.118 × M + 0.831 × P + 0.001 × N + 0.031 × R − 0.006 × M2 − 0.067 × P2 − 1.2 × 10−6 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

maxΔRaAluminum/SiC15% =

−(0.101 × M + 0.767 × P + 0.002 × N + 0.043 × R − 0.0046 × M2 − 0.0571 × P2 − 8.28 × 10−7 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

−(0.101 × M + 0.767 × P + 0.002 × N + 0.043 × R − 0.0046 × M2 − 0.0571 × P2 − 8.28 × 10−7 × N2 − 0.002 × n2)

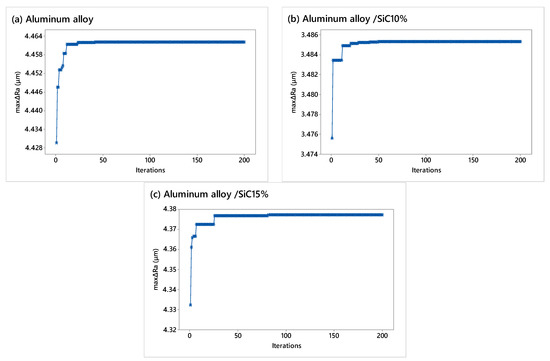

According to Figure 5, the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm has achieved its optimal value in the 195th iteration where maxΔRa equals 4.46218 μm for the model corresponding to pure aluminum alloy. This result is obtained for M = 8.1577, P = 6.4337 MPa, N = 728, and n = 10 rpm. For the second model referring to Al/SiC10% material, the algorithm reached its maximum value for maxΔRa, equal to 3.48535 μm. This result is obtained for M = 9.8426, P = 6.2056 MPa, N = 417.2663, and n = 7.7451 rpm (n = 8 rpm). The optimum result for maxΔRa in this case was reached in the 88th iteration. For the third model referring to the Al/SiC15% material, the algorithm reached its maximum value for maxΔRa, equal to 4.37727 μm. This result is obtained for M = 10.9965, P = 6.7168 MPa, N = 728, and n = 10 rpm. The optimum result for maxΔRa in this case was reached in iteration 192.

Figure 5.

Convergence graphs for optimizing the rotating workpiece abrasive flow nano-finishing process [3] using VEGA for the cases of: (a) Aluminum alloy, (b) aluminum alloy/SiC10%, and (c) aluminum alloy/SiC15%.

3.3. Rotational-Magnetorheological Abrasive Flow Nano-Finishing Process

This abrasive flow nano-finishing process involves a rotary cam reciprocating motion applied to the polishing medium by a rotary magnetic field and hydraulic apparatus. Through the proper control of these two motions, a uniform and smooth mirror-like finish-machined surface is produced with enhanced material removal rates (nm/cycle). What is responsible for the finish-machining of parts is the magnetic flux density measured at the fixture’s adjacent inner surface. The brush formulated by the magnetorheological polishing fluid at the inner surface is in contact with the workpiece. The optimization problem formulated in this case is a multi-objective one, and takes advantage of the experimental results provided by Das et al., (2012) in [4]. In their work, four process parameters were examined, hydraulic extrusion pressure P (Bar), number of finishing cycles N, magnet’s rotational speed n (rpm), and mesh size of abrasive, M. The four independent parameters were studied under the central composite design approach having 30 experimental runs. The optimization objectives were to minimize surface roughness minRa, or equivalently, to maximize the percentage improvement in surface roughness, max%ΔRa = maxΔRa × 100/Rainitial, while simultaneously maximizing material removal maxMR (mg). Regression models and parameter bounds were the same as those examined by Das et al., (2012). Equations (9) and (10) represent the models developed by Das et al. (2010) referring to max%ΔRa (%) and maxMR (mg), respectively, while the parameter bounds were subjected to the following ranges: 32.5 ≤ P ≤ 42.5, 600 ≤ N ≤ 1400, 50 ≤ S ≤ 250, and 90 ≤ M ≤ 210.

max%ΔRa = −(−52.61 + 10.49 × P − 0.08 × N − 0.56 × S + 0.11 × M + 2.77 × 10−3 × P × N + 0.02 × P × S − 1.33 × 10−3 × P × M +

0.60 × 10−4 × N × S + 1.75 × 10−4 × N × M − 9.22 × 10−5 × S × M − 0.19 × P2 − 3.16 × 10−5 × N2 − 8.61 × 10−4 × S2

− 8.2 × 10−4 × M2)

0.60 × 10−4 × N × S + 1.75 × 10−4 × N × M − 9.22 × 10−5 × S × M − 0.19 × P2 − 3.16 × 10−5 × N2 − 8.61 × 10−4 × S2

− 8.2 × 10−4 × M2)

maxMR = −(−687.55 + 30.39 × P − 0.04 × N − 0.76 × S + 0.69 × M + 2.04 × 10−3 × P × N + 1.56 × P × S + 4.60 × 10−3 × P × M − 1.33 × 10−4

× N × S + 3.33 × 10−6 × N × M − 3.00 × 10−3 × S × M − 0.44 × P2 − 3.85 × 10−5 × N2 − 6.05 × 10−4 × S2 − 1.75 × 10−3 × M2)

× N × S + 3.33 × 10−6 × N × M − 3.00 × 10−3 × S × M − 0.44 × P2 − 3.85 × 10−5 × N2 − 6.05 × 10−4 × S2 − 1.75 × 10−3 × M2)

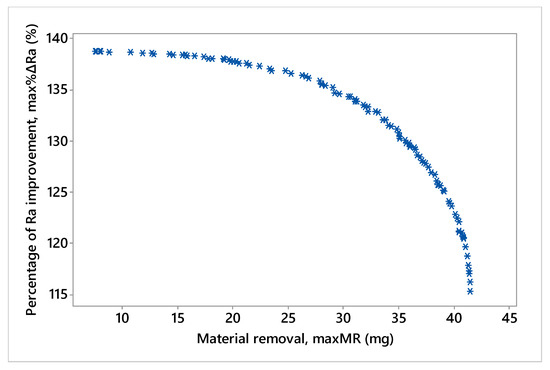

Das et al. (2012) [4] optimized max%ΔRa using the desirability function embedded in the response surface methodology. The same problem has been handled in this work as a multi-objective optimization problem, by applying the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm with its multi-objective modules (MOVEGA) with a population size equal to 10 and a maximum number of generations equal to 100. The resulting nondominated optimal solutions in the form of the Pareto front are illustrated in Figure 6. It is observed that the algorithm has successfully solved the two-objective problem by obtaining solutions that satisfy several optimization concepts in terms of the two conflicting objectives. The nondominated solutions are uniformly distributed all along the resulting solution path while the spacing and coverage of solutions are dense and almost equidistant. It can also be observed that the majority of nondominated optimal solutions are located in the central region of the Pareto front, suggesting that the algorithm has managed to cope with the trade-off between the two conflicting optimization objectives and provide more solutions for simultaneously satisfying both objectives rather than favoring one objective at the expense of the other. Unfortunately, the solutions obtained as nondominated optimal ones have not been compared to any results found in [4], as the problem was not examined under such assumptions. For this particular optimization problem, a comparison with results yet to be obtained by other heuristics will be conducted as a future work.

Figure 6.

Nondominated Pareto optimal solutions obtained by VEGA for optimizing the rotational-magnetorheological abrasive flow nano-finishing process [4].

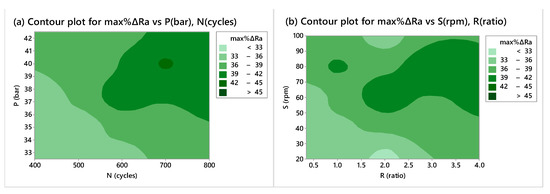

In order to provide an experimental validation at least when it comes to the work of Das et al. (2012) [4] concerning the single-objective optimization of the max%ΔRa objective, contour plots that have not been presented in the original work of Das et al. (2012) [4] were created to examine whether the experimental results agree with the model employed for optimizing the max%ΔRa objective, for validation purposes. The same for the maxMR objective was not examined, as it is not analytically provided in the work of Das et al. (2012) [4]. The experimental observations appearing in Figure 7a,b, are in total agreement with the original experimental results presented in [4].

Figure 7.

Contour plots for examining the effects of independent variables for controlling the rotational-magnetorheological abrasive flow nano-finishing process, with reference to experimental results presented in [4], (a) for max%ΔRa vs. P (bar), N (cyles); (b) for max%ΔRa vs. S (rpm), R (ratio).

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In the present study, three cases related to the nonconventional machining process known as “abrasive flow machining-AFM” have been examined for their parameter optimization potentials. A modified virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm has been applied to find the optimal solutions for the objective determined per case study, whilst the results obtained have been compared to those available in the contributions where the AFM cases have been found. In all cases examined, the results have been found to be superior to those obtained by other optimization systems such as soft computing (neural networks), genetic algorithm, and desirability function. In the work, the same regression equations as original outputs from actual experiments have been adopted as objective functions to evaluate them with the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm under the same conditions (i.e., constraints, upper and lower parameter bounds, algorithmic parameter settings, etc.). Looking further ahead, the authors are to implement this algorithm to optimization problems either selected from the broader literature or formulated by their original experimental results mainly referred to the milling and tuning of several engineering materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.F. and N.M.V.; methodology, N.A.F. and N.M.V.; software, N.A.F.; validation, N.A.F. and N.M.V.; formal analysis, N.A.F. and N.M.V.; investigation, N.A.F.; resources, N.M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.F.; review and editing, N.M.V., supervision, N.M.V.; project administration, N.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data for public archival is reported in this study. The study does not report any data of this kind.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rhoades, L.J. Abrasive flow machining. Manuf. Eng. 1988, 1, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.K.; Jain, V.K. Optimum selection of machining conditions in abrasive flow machining using neural network. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2000, 108, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, M.R.; Zain, V.K.; Ramkumar, J. Experimental investigations into rotating workpiece abrasive flow finishing. Wear 2009, 267, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Jain, V.K.; Ghoshdastidar, P.S. Nanofinishing of flat workpieces using rotational–magnetorheological abrasive flow finishing (R-MRAFF) process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 62, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Venkatesh, G.; Rajesha, S.; Kumar, P. Experimental investigations into ultrasonic-assisted abrasive flow machining (UAAFM) process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 80, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, B.; Joshi, S.S.; Raghuram, M.V.G.S.; Balasubramaniam, R. An experimental analysis of magnetic abrasives finishing of plane surfaces. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2006, 10, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, B.S.; Walia, R.S.; Singh, V.P. Electrochemical-aided abrasive flow machining (ECA2FM) process: A hybrid machining process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 79, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petare, A.C.; Jain, N.K. A critical review of past research and advances in abrasive flow finishing process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 741–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambharia, J.; Mali, H.S. Recent developments in abrasive flow finishing process: A review of current research and future prospects. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2019, 233, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiresan, S.; Mohan, B. Experimental Analysis of Magneto Rheological Abrasive Flow Finishing Process on AISI Stainless steel 316L. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2018, 33, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.; Petare, A.C.; Jain, N.K. Advances in abrasive flow finishing. In Advances in Abrasive Based Machining and Finishing Processes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 147–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghanghadikolaei, A.; Mohammadian, B.; Namdari, N.; Fotovvati, B. Abrasive machining techniques for biomedical device applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, S.M.; Basha, M.M.; Venkaiah, N.; Sankar, M.R. A review on abrasive flow finishing of metal matrix composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singari, R.M.; Mishra, R. Modelling and optimisation of magnetic abrasive finishing process based on a non-orthogonal array with ANN-GA approach. Trans. IMF 2020, 98, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gupta, V.; Sankar, M.R. Magnetic Abrasive Finishing Process. In Advances in Abrasive Based Machining and Finishing Processes. Materials Forming, Machining and Tribology; Das, S., Kibria, G., Doloi, B., Bhattacharyya, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paswan, S.K.; Singh, A.K. Theoretical and experimental investigations on nano-finishing of internal cylindrical surfaces with a newly developed rotational magnetorheological honing process. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2020, 234, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, H.S.; Manna, A. Simulation of surface generated during abrasive flow finishing of Al/SiCp-MMC using neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 61, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, K.L.; Billo, R.E.; Bopaya, B. A Neural Network Process Model for Abrasive Flow Machining Operations. J. Manuf. Sys. 1998, 17, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Rai, D.P.; Balic, J. A new optimization algorithm for parameter optimization of nano-finishing processes. Sci. Iran. E Ind. Eng. 2017, 24, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanisha, T.C.; Kuppan, P.; Narayanan, S.; Denis Ashok, S. A Fuzzy Logic based Model to Predict the Improvement in Surface Roughness in Magnetic Field Assisted Abrasive Finishing. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 1948–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. Evolutionary Significance of Virus Infection. Nature 1970, 227, 1346–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, N.; Fukuda, T.; Shimojima, K. Virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm for a self-organizing manufacturing system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 1996, 30, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K.; Adsul, S.G. Experimental investigations into abrasive flow machining (AFM). Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2000, 40, 1003–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).