Abstract

Despite extensive research, predicting ejection forces during the injection moulding process remains challenging due to the complex calculation of the coefficient of friction. This coefficient comprises various components that are difficult to isolate, complicating independent predictions. Consequently, using literature-documented coefficient of friction for different material contacts often leads to discrepancies between the experimental data and the predictive models of ejection forces. The adhesion component is a particularly problematic aspect, and is frequently excluded from analyses due to the difficulties associated with measuring it directly. This study aims to present the development of a tool designed to measure both the friction and adhesion forces under conditions that replicate those of the injection moulding process. The measured values were then used to calculate the corresponding coefficients: the static coefficient of friction (COF) and the coefficient of adhesion (COA). The conducted measurements identified the most influential factors in both coefficient values using a Design of Experiments (DoE), revealing that replication temperature was the factor promoting the highest variation across all the tested polymers.

1. Introduction

Injection moulding is regarded as one of the most widely used processing techniques for the fabrication of plastic components. The process is divided into multiple phases, including mould closing, mould filling, pack and hold, cooling, and demoulding of the produced component. The final stage of injection moulding, known as ejection or the demoulding phase, represents the most critical stage of the injection moulding process [1,2,3,4,5], as it involves the mechanical forced separation of the part from the mould. This stage is of particular importance, as issues arising during this phase have the potential to lead to a range of complications [1,2,3,4,6,7]. It is essential that the part reaches the optimal temperature for demoulding from the mould as soon as it has achieved the necessary structural stability, without incurring distortion or damage from the ejector pins [8]. The ejection force is influenced by several factors, especially those affecting parts with deep cores [9,10], such as shrinkage and the coefficient of friction. This includes mechanisms of deformation and adhesion.

As evidenced in the works of Pouzada et al. [3], Blau et al. [7], and Popova et al. [10], friction between two surfaces in contact was first studied by da Vinci. This was followed by the development of the coefficient of friction concept and the respective laws by Amontons and Coulomb centuries ago. These models have been successfully applied in several situations with good outcomes. However, discrepancies emerge between the analytical models and the experimental outcomes in the context of polymer moulding processes, such as injection moulding and thermoforming [3]. The coefficient of friction between steel and acrylonitrile butadiene (ABS) typically ranges from 0.3 to 0.5. However, experimental data from [3] shows that coefficient of friction can vary depending on the roughness of the interface. Similar differences have been found in a range of other polymers, while using different processing conditions. Correia et al. [1] studied the coefficient of friction behaviour between polypropylene (PP) and steel in replication conditions. The measured values ranged from 0.25 to 0.5, which differed from the typical values for these paired materials (0.3 and 0.4 for dry conditions). These differences may have implications for the values of friction force and, consequently, for the prediction of demoulding force. Rather than relying on standard values for the coefficient of friction, it is preferable to predict or measure that coefficient for each material pair and under the correct interface conditions.

Some authors claim that the coefficient of friction is the result of deformation, adhesion, and ploughing [1,11,12]. The ploughing and deformation are derived from the same contributions, corresponding to plastic and elastic deformation, respectively. These phenomena have been subject of extensive research and are recognised for their contribution to the coefficient of friction. The deformation mechanisms’ two surfaces in contact are influenced by several factors, including the surface roughness of the harder material [1,11,12,13,14], the properties of the materials, and the normal force that maintains the two surfaces in contact [13,14]. It occurs when relative movement is promoted between two surfaces in contact, due to the presence of asperities responsible for roughness [15,16]. The presence of asperities at the surfaces may contribute to elastic and plastic deformation, as evidenced by different studies [13,14,16]. In the case of elastic deformation, the material undergoes a recovery process whereby it reverts to its initial shape prior to the removal of the force that caused deformation. In the event of plastic deformation, the surface of the soft material will incur permanent damage and scratches are formed. Further research is required to determine the contributing factors in relation to the adhesion mechanism. According to several studies, adhesion is highly dependent on the mould and part material [5,12,17,18,19,20,21], as well as the surface tension of the mould surface [22,23,24,25]. The quantification of this mechanism is challenging, as it presents differences according to the scale of roughness, whether macro, micro, or nano. The difficulty of isolating the different friction mechanisms is a key issue in the estimation and prediction of the coefficient of friction. The tools available for measuring friction forces are unable to evaluate the different mechanisms, including the evaluation of adhesion forces under conditions similar to those used for the measurement of friction force.

To address these limitations, a new device was developed to measure both friction and adhesion forces under identical conditions. The present study details the tests conducted with the developed equipment and a Design of Experiments (DoE) using a factorial analysis, used to vary multiple parameters known to influence the static coefficient of friction (COF) and the coefficient of adhesion (COA).

2. Equipment for Friction and Adhesion Forces Measurement

The equipment developed in the presented study is based on the system previously described by Pouzada et al. [3], but incorporates several improvements that enable the measurement of friction and adhesion forces under identical test conditions without the need for auxiliary devices. This has been achieved through the development of autonomous equipment described in a patent application WO 2022/189923 A1 (Geneva, Switzerland) [26]. The developed apparatus meets the following functional requirements:

- Ease of sample and stamp change. The sample is produced using a polymer used in injection moulding, and the second is a component produced, in this case in steel, which is used to simulate the injection mould walls.

- Ability to heat the stamp to the required replication temperature and subsequently cool the system to the test temperature, which corresponds to the ejection temperature.

- Capability to change the test speed both vertically (for the adhesion force and contact force measurement) and horizontally (for the friction force measurement).

- Ability to modify the contact force and stabilisation time before cooling.

- Capability to measure the three essential forces used to determine COF and COA: the sliding force, the normal force (contact force), and the adhesion or pull-off force.

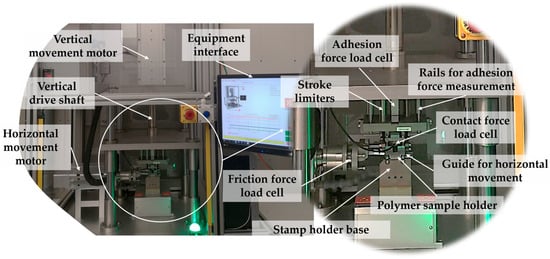

Figure 1 illustrates the developed equipment as along with its principal components.

Figure 1.

Described equipment and principal components.

The apparatus is equipped with two motors that independently control vertical and horizontal movement. It also contains three load cells dedicated to measure contact (normal), sliding and adhesion forces; a heating system placed beneath the stamp-holder base; a vortex-based cooling unit; and various other components. Additionally, it allows the modification of the test specimens without the necessity of disassembling other components of the prototype. This was a process that was required with the previous equipment. The measurement of contact and sliding forces is performed by two separate load cells, CDIT-1, which are manufactured by LCM Systems (Newport, United Kingdom). The load cells have a maximum capacity of 250 kg, with a measurement precision of 0.05% of FSO (Full-scale output). The load cell responsible for the adhesion force is also from LCM Systems (STA-1), with a capacity of 50 kg and 0.02% of FSO. DSCUSB strain gauge load cell condition modules were applied in each of the load cells to extract the performed measurements.

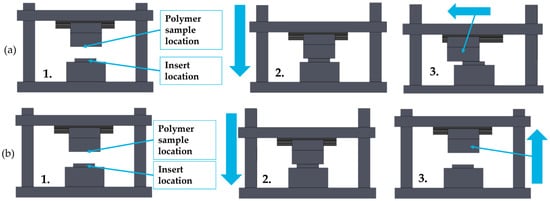

The methodology used for the test is outlined in Figure 2. The methodology involves heating the stamp up to the replication temperature, which is then followed by bringing the two surfaces into contact. The desired contact force is maintained by using a vertical motor. After a stabilisation period, the system undergoes a controlled cooling phase, after which the selected test is performed. The experimental procedure enables the measurement of either friction or adhesion force. The measurement of the friction force is achieved by moving the sample horizontally against the stamp using the horizontal drive motor. The motor applies a force on the polymer sample holder, inducing lateral sliding relative to the surface stamp placed in the stamp-holder base. To measure the adhesion force, the sample is moved in an upward direction from the stamp. In this case, the vertical movement motor actuates pulling the polymer sample upward via the stamp. Note that, the adhesion force is not measured in sliding conditions. Instead, the measurement is performed in a separate test of the friction force. The objective is to separate the measurement of the adhesion contribution from the coefficient of friction.

Figure 2.

Scheme of the test methodology. (a) Friction force measurement and (b) adhesion force measurement.

Comparing the developed equipment with that described by Pouzada et al. [3] reveals that the improved equipment also allows the measurement of the pull-off (adhesion force) between two surfaces in contact with prior replication of the hard surface in the surface of the softer material. This procedure is performed under the same conditions as those used in the measurement of friction force. The former equipment does not allow the execution of adhesion tests due to the actuation system (compressed air), which make it impossible to control the separation velocity and evaluate the pull-off force.

3. Materials and Methods

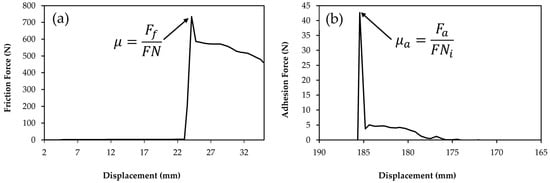

The apparatus previously described was used to measure friction and adhesion forces. COF and COA were calculated using the equations presented in Figure 3. The static COF was calculated using the static sliding force (Ff) and the normal force (FN), both of which were measured simultaneously, as described in the relevant literature on the subject, including [3]. The COA was calculated using the measured adhesion force (Fa) divided by the initial normal force (FNi), which is defined as the normal force at the start of the upward movement [27].

Figure 3.

Procedure to calculate both coefficients using the measured data. (a) COF and (b) COA.

The characterisation of the stamp surface was performed using the InfinitFocus SL (Bruker-Alicona, Graz, Austria). This optical device can evaluate surface topography, thus allowing the acquisition of various surface descriptors, both in profile and surface. In the present study, surface descriptors were used, as they seem to be the most accurate method of surface characterisation. Surface analysis was performed in accordance with the ISO 25178 standard [28] on both stamps at nine different points. For the purpose of this analysis, an optical objective of 50× was used, and ten analyses with a size of 410 × 410 µm were performed along the stamp length. For all the analysed surfaces, a cut-off filter (Lc) of 81.9623 µm was applied.

Two stamps with different surface roughness were produced using AISI H13 steel and different grades of sandpaper. For the higher roughness stamp, sandpaper with a grain size of 220 was used. For the lower roughness stamp, two different sandpapers with sizes of 220 and 320 were used. The polymer samples were produced using three different materials: polystyrene (PS) Styrolution PS 165 N from INEOS Styrolution (Frankfurt am Main, Germany), polypropylene (PP) Capilene E 50 E from Carmel Olefins (Haifa, Israel), and polycarbonate (PC) Lexan Resin 123 R from Sabic (Riade, Saudi Arabia). Table 1 presents the principal properties of the polymers used in the study. The presented information was drawn from the material datasheets.

Table 1.

Properties of the polymers employed in the study.

A Design of Experiments (DoE) was conducted using a regular four-level factorial design with a resolution of IV. The main objective of this analysis was firstly, to reduce of the number of experiments, and secondly, to evaluate the effect of each variable, as well as the potential interactions between the variables on the COF and COA. This was achieved through a screening analysis of the factors within two levels. This will allow the selection of the conditions to study in future tests. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed, using Design-Expert® software (version 10), to evaluate the significance of the observed effects. The applied statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05, and the analysis was performed for each material for both COF and COA. The study of two distinct levels of variation in the processing conditions has been established. The selected conditions are known to exert an influence on the friction and adhesion forces. The conditions included the replication temperature, the test temperature, the contact force, and the surface roughness. The present study was performed to validate the developed equipment, while the most influential parameters were identified to define future research on this subject.

The conditions used in the experiment are outlined in Table 2. In the case of roughness, only the test level is provided, as the surface characterisation was performed after the establishment of the test conditions. The replication temperature for each material was selected on the basis of the material datasheets, as well as from trials for replication at different temperatures. The selected temperatures had higher values than the vicat softening temperature for each material. PC test temperature was selected from the mould temperatures indicated by the material supplier, while the PS and PP temperatures were selected from preliminary tests. The roughness was the result of the surface preparation method, as described earlier. Contact force was derived from the literature and studies using other types of equipment.

Table 2.

Test conditions applied during the friction and adhesion force measurements.

4. Results

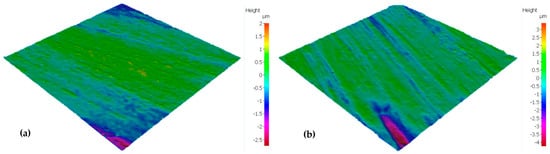

The roughness measurement device allowed the acquisition of surface topography, and this was presented in the form of a colour map of the two analysed surfaces. The standard ISO 25178 was followed to characterise the analysed surfaces. Figure 4 presents the surface of each analysed stamp without the application of any cut-off filter. As it is possible to observe, the method used for surface preparation results in a non-uniform topography along the sample surface.

Figure 4.

Surface topography of the analysed stamps. (a) Stamp with roughness Level “−” and (b) stamp with roughness Level “+”.

Surface analysis was conducted using surface descriptors, which included the average height of the selected area (Sa), the root-mean-square height (Sq), the maximum height of the selected area (Sz), the skewness (Ssk), and the kurtosis (Sku). The resulting measured values are presented in Table 3. Recently a large group of authors published a comprehensive study [29] in which samples with the same topography were evaluated using different equipment. The study proposes a series of recommendations for the effective characterisation of topography. It recommends that data which infringes the resolution criterion and deviates from the majority measurements at each length scale be removed, in the case of scale-dependent parameters. The study further recommends the use of scale-dependent metrics as an alternative to the exclusive use of Ra value. However, their methodology was not applied in the present study. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that it will be advantageous for the definition of surface topography in the future.

Table 3.

Surface roughness parameters of the stamps measured in area.

The results of the analysis indicate that the surface roughness of the two stamps under testing conditions differs due to the surface preparation method and the use of sandpaper with different grain sizes. Sa is an average roughness parameter representing the height of each point difference in relation to the arithmetic mean of the surface. It represents all values measured in the surface texture, while the Sz parameter represents the difference between the highest peak and the lower valley observed in the analysed surface. Regarding these the two measured surfaces, the stamp with “Level−” of roughness presents lower values for Sa and Sz. As two amplitude parameters, Sa and Sz represent the presence of higher asperities at the surface. These increase the COF value due to the increase in the deformation mechanism. Firstly, there is elastic deformation, and for higher values of Sa and Sz, there is also plastic deformation, also known as ploughing. Lower values usually decrease the COF at the interface between two surfaces. Regarding the adhesion mechanism, the contrary is observed. In the majority of engineering contact systems, lower values of Sa and Sz have been found to increase the real area of contact between two surfaces. This, in turn, leads to an increase in the adhesion mechanism. From the surface characterisation presented in Table 3, it is expected that the COF increases with Sa and SZ increase, while COA decreases. It is important to note that the stamps were produced using the same material and prepared by the same method. This analysis was performed to classify the samples and to evaluate the impact of the two topographies on the study responses [27].

Skewness (Ssk) and kurtosis (Sku) displayed analogous behaviour in the analysed surfaces. The Ssk parameter is associated with the asymmetry of the height distribution of the measured values, which is negative for both surfaces. This indicates that the distribution is uneven above the mean plane, suggesting the presence of more valleys than peaks at the surfaces. In the case of the Ssk, the values are near to zero. However, there are locals in the samples where Ssk value is positive (see Table 3 for the standard deviation values). The presence of locals with Ssk positive could lead to higher friction values due to the presence of more peaks, which might increase the deformation mechanisms of friction. Furthermore, negative values of Ssk could lead to higher values of adhesion in static friction accompanied with a reduction in deformation mechanisms. The Sku parameter has been demonstrated to be associated with the sharpness of the height distribution. In the case of the studied surfaces, Sku is greater than three, indicating a spiked height distribution. This suggests that surface has more extreme peaks and valleys than a normal distribution. In dry conditions, this distribution could result in a lower value of adhesion mechanism, due to the presence of extreme peaks and valleys instead of a more uniform surface. High Sku and negative Ssk values generally results in a reduction in friction at the interface between two surfaces [30]. Ssk and Sku are related to the surface preparation method, which involved the use of different sandpapers to achieve varying surface roughness, resulting in non-symmetrical distributions rather than a normal distribution. This results in a non-uniform distribution of peaks and valleys, contrary to other type of production techniques. These two parameters can be used to evaluate the surface texture, which can have a significant impact in properties of the studied application, such as wear resistance and adhesion, especially in surface coating for the moulding tools. Note that these two surface descriptors present a larger standard deviation, which may be associated with the type of surface preparation method used for the test surfaces.

The data from the measurement of friction and adhesion forces were used to perform a Design of Experiments (DoE), with the objective of evaluating the two required responses, namely the COF and the COA. The DoE was established in accordance with the outputs of the analysis software for a factorial study comprising four factors and two levels. The DoE and the results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Design of Experiments with input and output values (bold and underlined values indicate the higher COA values for each material).

From the data shown in Table 4, it can be observed that COA for all polymeric materials is more pronounced when compared to tests with a higher replication temperature. This observation indicates that this processing condition has a significant influence on COA. Additionally, PC exhibited a higher coefficient of friction at the interface between the tested surfaces when compared with the other polymers under study.

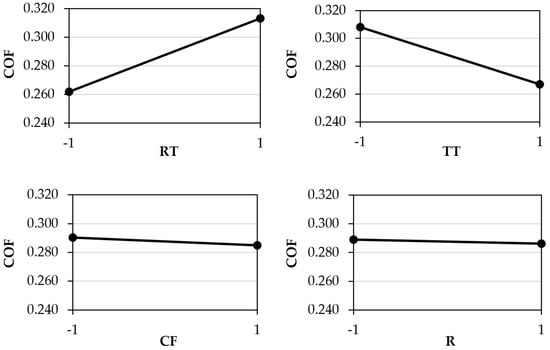

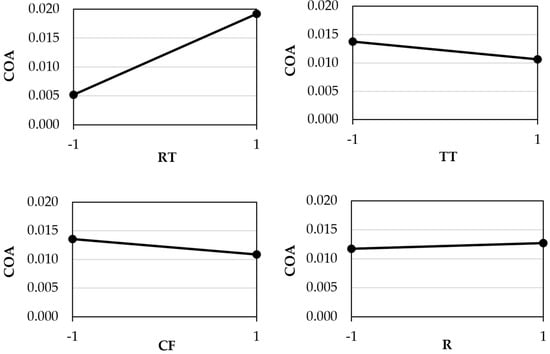

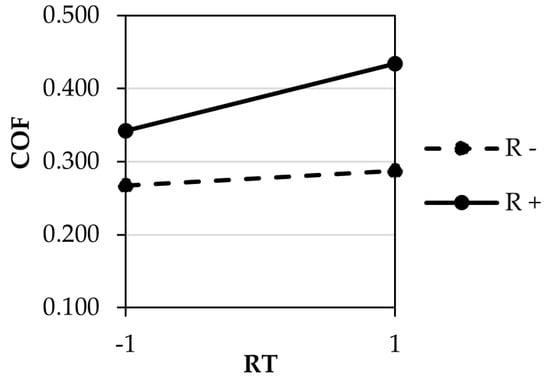

The effects of the variables for PP are illustrated in Figure 5. The results suggests that the replication temperature exerts a great influence in COF and COA responses for almost all the tested materials. Another variable that appears to play a significant role in the coefficient of friction for PP is the test temperature (TT). In the case of injection moulding processes, the replication temperature is associated with the melt temperature. The application of higher temperatures helps to enhance the replication of the mould onto the polymer’s surface due to the decrease in polymer viscosity and the increase in the molecular chains’ mobility. This replication tends to increase the real area of contact at the interface, thus increasing both adhesion and deformation mechanisms. The elevated COF at lower test temperatures can be related to the polymer’s properties, especially the material elastic modulus, which is higher at lower temperature. This can increase the deformation mechanism of friction related to the mechanical interlocking, which hinders the relative movement between the two surfaces and consequently increases the COF at lower temperatures. As for the other two variables, no noticeable effect on this phenomenon is observed.

Figure 5.

Variable-effect plots for the static COF of PP. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

The effects of the variables for PC are presented in Figure 6. The observed behaviour, due to changes in the levels of the tested variables, is like that identified for PP, with both replication and test temperatures being the most influential variables.

Figure 6.

Variable-effect plots for the static COF of PC. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

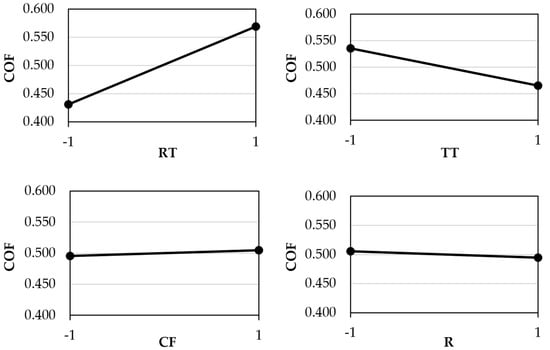

The impact of the variables for PS is demonstrated in Figure 7. This material exhibits different behaviour compared to PP and PC. In this case, the most influential variable appears to be the roughness, while the test temperature has a relatively minor influence.

Figure 7.

Variable-effect plots for the static COF of PS. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

Despite the data presented in the literature regarding contact force [31,32], this study found only a slight increase in the COF value was verified for PC (Figure 6). In contrast, a decrease was observed for PP (Figure 5) and PS (Figure 7) between the higher and lower levels of contact force. Regarding surface roughness, a significant discrepancy was observed between the lower and higher levels. For PS, this suggests that reducing the number of experiments may not be the optimal approach for investigating the influence of these factors on COF. Also, it could be possible that using higher test temperatures, near the vicat softening temperature, may induce different behaviour from that observed for PC and PP.

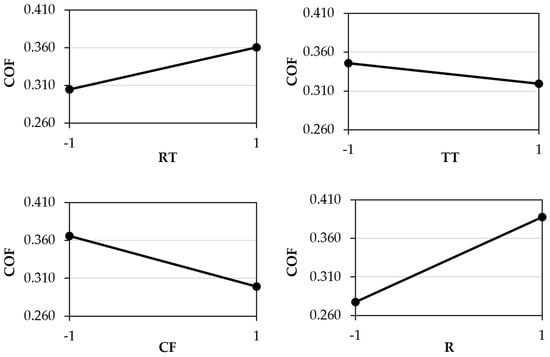

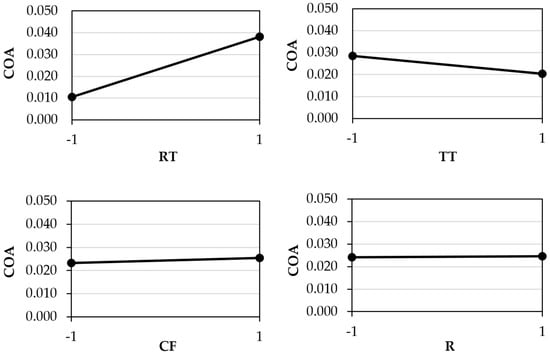

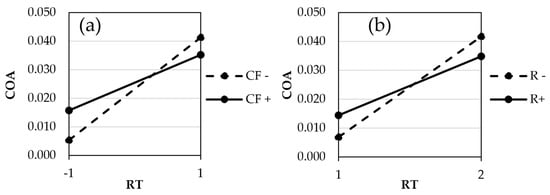

Figure 8 shows the effect plots for the coefficient of adhesion measured for PP. It can be observed that replication temperature has the greatest influence on this phenomenon, with an increase in temperature leading to a higher COA. This can be attributed to the decrease in the materials viscosity, which has the potential to enhance the replication of the stamp surface onto the polymer. This, in turn, results in the increase in the real area of contact at the interface between the two materials, consequently leading to a higher COA. It seems that the remaining variables have a comparatively lesser influence on COA.

Figure 8.

Variable-effect plots for the COA of PP. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

The effect plots for the COA measured for PC are presented in Figure 9. As with PP, for PC the data demonstrated a low influence of contact force, roughness and test temperature on this coefficient. Conversely, replication temperature shows a higher impact.

Figure 9.

Variable-effect plots for the COA of PC. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

For PS, the effect of the studied variables on COA is illustrated in Figure 10. As observed in the case of the other two tested materials, the replication temperature exerts the greatest influence on this coefficient.

Figure 10.

Variable-effect plots for the COA of PS. (Legend: RT—Replication Temperature; TT—Test Temperature; CF—Contact Force; R—Stamp Roughness).

Regarding adhesion between two surfaces under conditions like the injection moulding process, there is no significant data available in the existing literature. However, the test results of this study can be explained by the replication of the stamp surface onto the surface of the polymer samples.

At this stage, it is not possible to explain the interaction between the different variables, as this depends on the specific materials under consideration. The data presented suggests that these interactions do not significantly influence the COF value. However, further tests are required to accurately determine the extent to which the interaction between factors is important.

The analysis of the previous plots shows that replication temperature is the primary factor influencing both the COF and COA across all the materials. This phenomenon probably occurs due to a decrease in the polymer’s viscosity, thereby enabling more accuracy in the replication of the stamp surface. Although the existing literature acknowledges that contact force, test temperature, and surface roughness also affect friction and pull-off force. It is generally accepted that a higher initial value leads to an increase in COF, similar to the effect of increased temperatures. Surface roughness, however, always depends on the specific level. The literature indicates that there is an optimal value for roughness that results in a lower COF [33,34]. As the roughness value increases, the deformation mechanisms, including elastic and plastic deformation, also increase, resulting in a higher COF [1,12,35,36]. In these cases, a higher mechanical interlocking is verified at the asperities of both surfaces. If lower values of roughness are present, particularly in the case of polished surfaces, the COF values can increase due to an increase in the adhesion mechanism [12,35,37], which results in an increase in the real contact area at the interface between the two materials. However, in this study, the lower roughness may exceed the optimum value, preventing the confirmation of the information available in the literature. As demonstrated in earlier studies [12], the optimum value of roughness can be affected by test temperature and the applied contact/normal force. This results in differences in the behaviour of fiction force and consequently in the COF. These differences lead to varying values in the optimum roughness for reducing the COF value.

In addition to the performed DoE, an ANOVA analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of each factor on COF and COA for each of the tested polymers. The analysis was conducted with a significance level of 5%. This analysis is useful to understand the contribution of each variable (main factors) and some of the interactions for the responses. The interactions that were analysed were those related to the replication temperature, i.e., AB, AC, and AD. It is important to acknowledge that other interactions, which were not considered, are inherent within the alias chains. If all interactions are disregarded it could overestimate the contribution of the main factors, which is a consequence of the type of analysis that was performed. It seems that replication temperature is the most influencing factor in the performed analysis. Furthermore, statistical significance was evaluated among the groups, and whether there was evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The present hypothesis assumes that there would be no significant differences among the results. This supposition is verified for p-values higher than the level of significance used in the study.

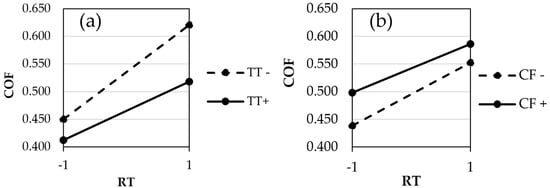

The PC analysis (Table 5) and the respective model for COF response, with the exclusion of variables exhibiting lower contribution, are deemed to be statistically significant, as evidenced by the model’s p-value falling below the applied level of significance. Furthermore, p-values greater than 0.1000 indicate that the model terms are not significant for the analysed response. In this case, the factors with highest contribution are the Replication Temperature (RT) with 73.59% and the Test Temperature (TT) with 19.00%. Despite the lower contribution of the contact force, the variable was maintained since it is a term that is required to support the model hierarchy with consideration of the interaction AC. As it is possible to observe, the interaction between A (RT) and B (TT) contributes 4.00% to the overall variance.

Table 5.

ANOVA analysis for PC static COF response, excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

The F-value of 58.57 for the model indicates that the model is significant. It is estimated that there is a 1.68% chance of an F-value of this value to occur due to noise. The model could be reduced, although this would mean excluding terms that are necessary for supporting the model hierarchy. Figure 11 presents the plots analysed in the ANOVA for interactions with a higher contribution. As it is possible to observe in the two analysed levels, there is no intersection between the two lines of the presented interactions. However, it is possible that there will eventually be intersection between them for both the interaction AB (Replication Temperature x Test Temperature) and interaction AC (Replication temperature x Contact Force). As the study design focused on screening main effects, potential interaction effects may not have been fully captured.

Figure 11.

Interaction plots for the static COF of PC. (a) Replication Temperature (RT) vs. Test Temperature (TT) and (b) Replication Temperature (RT) vs. Contact Force (CF).

Concerning the PP analysis (Table 6) and the corresponding model for COF response, the factors with the greatest influence are the Replication Temperature (RT) and the Test Temperature (TT). These factors account for 57.27% and 37.01% of the total contribution, respectively. The remaining factors exert a comparatively weaker influence in the coefficient of friction. As in the previous case, the p-value for the model, the Replication Temperature, and Test Temperature is lower than 0.05. This indicates that the null hypothesis can be rejected and that there are significant differences among the tested levels. The other presented variable in the ANOVA study was the interaction between the Replication Temperature and Test Temperature. The p-value indicated that no significant differences were observed among the tested levels.

Table 6.

ANOVA analysis for PP static COF response excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

Considering the terms presented in Table 6, it is possible to realise that the Model F-value of 39.17 means that the model is valid and there is a chance of 0.20% that an F-value this large occurs due to noise.

The interaction plot for the analysed data of the PP coefficient of friction is presented in Figure 12. As it is possible to observe, this interaction is significantly low, despite being the interaction with a higher contribution.

Figure 12.

Interaction plot for the static COF of PP, interaction between Replication Temperature (RT) and Test Temperature (TT).

Respecting the PS analysis (Table 7) and the corresponding model for the COF response, the analysis indicates that the model for PS is statistically significant, since the p-value is lower than 0.05, when Test Temperature is excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, the interaction between the replication temperature and roughness was included in the study to preserve the alias chain of the model. However, an analysis of the p-value for the factors indicated that it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis for RT and AD due to the p-value. In the PS case, the most contributing factors are Roughness (R) with a contribution of 54.18%, followed by Contact Force (CF) with a contribution of 19.86%, and Replication Temperature (RT) with a contribution of 13.85%. This is in contrast to the findings for the remaining materials, where the RT was identified as the most significant factor.

Table 7.

ANOVA analysis for PS static COF response, excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

The interaction plot for Replication Temperature and Roughness is presented in Figure 13. As observed, the COF variation between the lower level of roughness and the two levels of Replication Temperature do not demonstrate a significant difference. It has been demonstrated that a greater degree of variation is present at the higher roughness level.

Figure 13.

Interaction plots for the static COF of PS, showing the interaction between the Replication Temperature (RT) and Roughness (R).

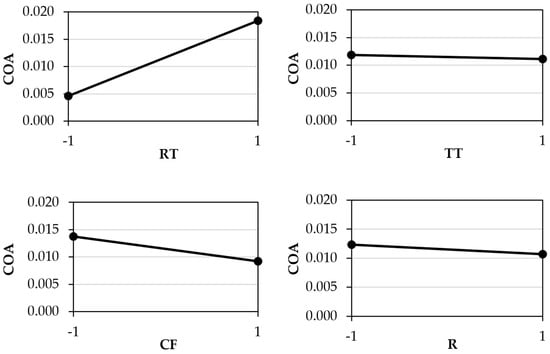

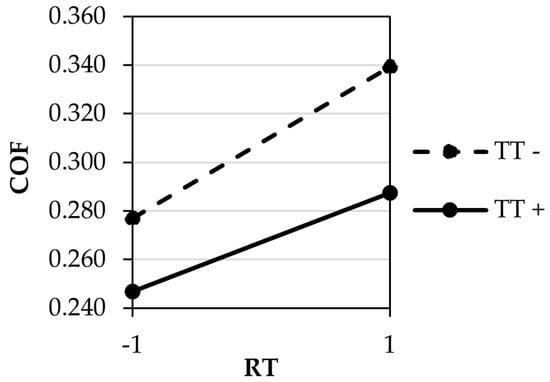

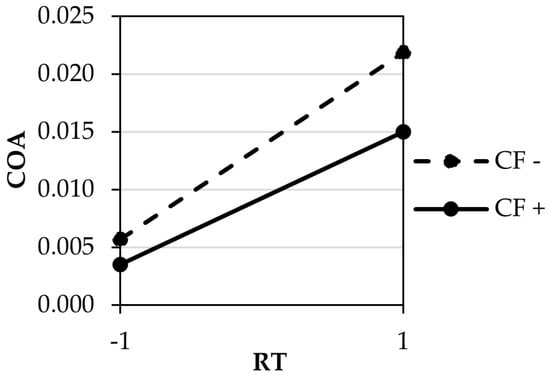

The response of the COA was also evaluated, and the data from the ANOVA analysis are presented in Table 8 for PC. In this case, despite the p-value being marginally higher than the level of significance, it remains below 0.100, indicating that the model is significant. In this case, the most influential factor is the Replication Temperature (RT), which contributes 79.45% to the COA. This is followed by the interaction between the Replication Temperature (TT) and the Contact Force (CF) which contributes 8.21%, while the Test Temperature has a contribution of 7.32%.

Table 8.

ANOVA analysis for PC COA, excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

The COA interaction plots for PC are shown in Figure 14. In this case, it is possible to observe that the interaction between the replication temperature and Contact Force is visible, as well as the interaction between the RT and the roughness of the stamp.

Figure 14.

Interaction plots for the COA of PC. (a) Replication Temperature (RT) vs. Contact Force (CF) and (b) Replication Temperature (RT) vs. Roughness (R).

The ANOVA analysis for PP (Table 9) also indicates that the model is significant. The Replication Temperature (RT) is the most significant factor with a contribution of almost 86%, followed by the Contact Force (10.26%) and the interaction AC (2.30%). In this case it is possible to reject the null hypothesis for most of the analysed factors and interactions. This indicates that there are significant differences between the analysed results.

Table 9.

ANOVA analysis for PP COA, excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

The Model F-value of 88.90 indicates that the model is valid and there is a probability of 0.04% that the F-value can be attributed to noise. The interaction with the higher contribution to the COA response of PP is presented in Figure 15. As it is possible to observe, the interaction’s contribution is significantly lower when compared with the contribution of RT and CF. In this case, the intersection between the two tested levels is not observed.

Figure 15.

Interaction plot for the COA of PP, showing the interaction between the Replication Temperature (RT) and Contact Force (CF).

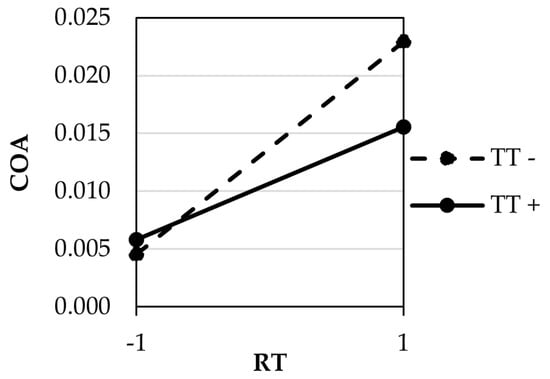

Regarding the ANOVA analysis for PS, presented in Table 10, it can be concluded that the analysed model is also significant. Regarding the factors under study, the p-value is indicative of the rejection of the null hypothesis for most of the factors, with values lower than 0.05. This indicates the presence of statistically significant differences among the group means. As was observed in the case of PC, in this case the factor with the greatest contribution to the development of adhesion is the Replication Temperature (RT), which accounts for 83.14% of the variance. The Test Temperature and Contact Force, with a contribution of 3.82%, and the interaction AB, with 8.59% were also considered.

Table 10.

ANOVA analysis for PS COA, excluding the lower contribution factors and interactions.

Regarding the interaction between the Replication Temperature and Test Temperature for PS (Figure 16) in relation to the COA response, it is possible to observe the intersection between the two lines that represent the lower and higher level of TT when analysed with two RT levels.

Figure 16.

Interaction plots for the COA of PS, showing the interaction between Replication Temperature (RT) and Test Temperature (TT).

At this stage, it is not possible to explain the interaction between the different variables, as this depends on the specific materials under consideration. Table 11 presents a summary of the findings for the influence of the tested factors in COF and COA.

Table 11.

Summary of the influence of the tested factors in COA and COF values. (4 indicates de most influencing factor and 1, the least influencing factor).

The data presented suggests that these interactions do not exert a significant influence on the COF and COA for most of the analysed data. Furthermore, some of the main factors also demonstrated a lower contribution. Also, it is important to mention that this analysis was conducted for the materials under study. It is well established that different materials present distinct behaviour in terms of responses, which will likely result in different responses. This implies that a new set of tests and analysis should be performed on other materials to develop a model for COF and COA considering the ANOVA analysis. The results will always be dependent on the equipment used to perform the measurement of friction and adhesion forces. The presented study highlights that Replication Temperature is the most influencing factor and it could hide the real contribution of the other factors and interactions. Further tests are required to accurately determine the extent to which the interaction between factors is important. Some of the analysed interactions appear to not be statistically significant, presenting a p-value higher than 0.05%. Given the nature of the performed analysis (screening), we decided to maintain the interactions in the models to maintain the integrity of the alias chain (variables that are linearly dependent on others). The exclusion of these interactions could potentially lead to an overestimation of the main effects, leading to possible errors. It seems that the using a statistical analysis with a reduced number of runs may lead to a loss of information concerning the contribution of some factors and their interactions in the COF and COA. This, in turn, could lead to incorrect conclusions. In future tests, a semi-crystalline and an amorphous polymer will be tested and the number of tested stamp surfaces will be increased to three, adding a new material for the stamp production. A higher replication temperature due to the adhesion force results will be established, with three different levels for test temperature, and contact force where a lower level will be tested. All the combinations of conditions will be tested for each pair of polymer/metal.

The presented equipment can be used to help in the development of the ejection system of injection moulds. Furthermore, it is a great asset in the testing of different coatings and mould finishing, with the objective of reducing COF during the ejection stage. In addition, it could be used to test different processing conditions, especially test temperature for mould temperature during the injection moulding process. It could also be used to mould material selection.

Despite the analysis and presented results, it is crucial to determine the correct influence of processing conditions on COA due to the lack of information on this subject. Additionally, it is essential to measure both friction and adhesion force under the same conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to present newly developed equipment capable of measuring both friction and adhesion forces under conditions similar to those found in injection moulds. In addition, it investigates the key factors influencing these forces through a Design of Experiments approach. The newly developed equipment enabled simultaneous measurement of friction and adhesion force under controlled conditions, with adjustable parameters such as temperature, velocity, and contact force. This type of test could assist in the correct development of the ejection system of injection moulds. Furthermore, it could be employed to test and select the most appropriate coatings for injection mould surfaces, when such coatings are required to facilitate the demoulding process.

The study revealed distinct behaviours among the tested materials with respect to their COF and COA. Adhesion measurements indicated that replication temperature had a more pronounced effect at higher levels, likely due to the increased replication of the stamp into the polymer sample, enhancing the contact area and thus adhesion. A higher replication temperature enhanced the patterning of the stamp’s features onto the polymer, resulting in stronger adhesion. The study also suggests that surface roughness may not play a major role in the frictional behaviour of these materials under the tested conditions, although the effect of surface roughness may be masked in the results due to the replication influence. The present study enabled the establishment of the conditions that will be applied in future studies.

This study underscores the need to understand the correct influence on the coefficient of adhesion due to the lack of comprehensive information on this subject. Additionally, it is essential to measure friction force under the same conditions as adhesion force to ensure consistency and comparability of results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Â.R.R., M.S.C. and A.J.P.; methodology, Â.R.R., M.S.C. and A.J.P.; validation, M.S.C. and A.J.P.; formal analysis, Â.R.R.; investigation, Â.R.R.; resources, A.J.P.; data curation, Â.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Â.R.R.; writing—review and editing, M.S.C. and A.J.P.; visualisation, Â.R.R.; supervision, M.S.C. and A.J.P.; project administration, A.J.P.; funding acquisition, A.J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Funds through FCT-Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, Reference UID/05256: Institute for Polymers and Composites (IPC/UM) and financial support via the project CDRSP Funding (DOI: 10.54499/UID/04044/2025) and ARISE funding (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0112/2020).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CF | Contact Force |

| COA | Coefficient of Adhesion |

| COF | Coefficient of friction |

| FSO | Full-scale output |

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| R | Roughness |

| RT | Replication Temperature |

| TT | Test Temperature |

References

- Correia, M.S.; Miranda, A.S.; Oliveira, M.C.; Capela, C.A.; Pouzada, A.S. Analysis of Friction in the Ejection of Thermoplastic Mouldings. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 59, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.C.; Neves, N.M.; Muschalle, R.; Pouzada, A.S. Friction Properties of Thermoplastics in Injection Molding. In Proceedings of the Society of Plastic Engineers’ ANTEC 2002 Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–9 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pouzada, A.S.; Ferreira, E.C.; Pontes, A.J. Friction Properties of Moulding Thermoplastics. Polym. Test. 2006, 25, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Â.R.; Correia, M.S.; Pontes, A.J. Coefficient of Friction in the Demoulding Forces of the Injection Moulding Process—A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, A.J.; Brito, A.M.; Pouzada, A.S. Assessment of the Ejection Force in Tubular Injection Moldings. 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291289799 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Kinsella, M.E.; Lilly, B.; Gardner, B.E.; Jacobs, N.J. Experimental Determination of Friction Coefficients between Thermoplastics and Rapid Tooled Injection Mold Materials. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2005, 11, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.J. The Significance and Use of the Friction Coefficient. Tribol. Int. 2001, 34, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, K.; Bissacco, G.; Kennedy, D. A Study of Demoulding Force Prediction Applied to Periodic Mould Surface Profiles. In Proceedings of the Society of Plastic Engineers’ ANTEC 2010 Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 May 2010; pp. 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, A.J.; Pouzada, A.S.; Pantani, R.; Titomanlio, G. Ejection Force of Tubular Injection Moldings. Part II: A Prediction Model. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2005, 45, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.; Popov, V.L. The Research Works of Coulomb and Amontons and Generalized Laws of Friction. Friction 2015, 3, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.E.; Suh, N.P. Frictional Behavior of Extremely Smooth and Hard Solids. Wear 1993, 162–164, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.S. Modelling the Ejection Friction in Injection Moulding. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, S.; Wei, D.; Song, H.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, H.; Song, S.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; et al. Frictional Strength Regulated by Roughness Alignment. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.I. Rough Surface Contact Modelling—A Review. Lubricants 2022, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, K.; Kennedy, D.; Bissacco, G. A Study of Friction Testing Methods Applicable to Demoulding Force Prediction for Micro Replicated Parts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Materials, Tribology, and Recycling Matrib 2010, Vela Luka, Croatia, 23–27 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ciavarella, M. A New Plasticity Index Including Size-Effects in the Contact of Rough Surfaces. Lubricants 2024, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Hwang, S.-J. Design and Fabrication of an Adhesion Force Tester for the Injection Moulding Process. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Hwang, S.J. Investigation of Adhesion Phenomena in Thermoplastic Polyurethane Injection Molding Process. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2012, 52, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, K.; Kennedy, D.; Bissacco, G. Investigating Polymer-Tool Steel Interfaces to Predict the Work of Adhesion for Demoulding Force Optimisation. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Mechanical Technologies and Structural Materials MTSM 2011, Split, Croatia, 29–30 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, M.W.; Salmoria, G.V.; Ahrens, C.H.; Pouzada, A.S. Study of Tribological Properties of Moulds Obtained by Stereolithography. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2007, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.C.R.; Netto, A.C.S.; Pontes, A.J. Experimental Study of Shrinkage and Ejection Forces of Reinforced Polypropylene Based on Nanoclays and Short Glass Fibers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2018, 58, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B. Principles and Applications of Tribology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eustathopoulos, N.; Sobczak, N.; Passerone, A.; Nogi, K. Measurement of Contact Angle and Work of Adhesion at High Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Chughtai, A.; Ahmad, J.; Ahmad, R.; Majeed, U.; Khan, I.H. Theory of Adhesion and Its Practical Implications. A Critical Review. J. Fac. Eng. Technol. 2010, 15, 21–45. Available online: https://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/jfet/previous-pdf/JFET_03_2007%20Theory%20of%20Adhesion%20A%20Critical%20Review%20f.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Berger, G.R.; Steffel, C.; Friesenbichler, W. A Study on the Role of Wetting Parameters on Friction in Injection Moulding. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2016, 52, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, A.J.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Correia, M.S. Device and Method for Measuring Friction and Adhesion Forces Between Two Surfaces in Contact for Polymer Replication Processes. WO 2022/189923 A1, 15 September 2022. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/WO2022189923 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bhushan, B. Introduction to Tribology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 25178-2:2021; Geometrical Produsct Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal—Part 2: Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Pradhan, A.; Müser, M.H.; Miller, N.; Abdelnabe, J.P.; Afferrante, L.; Albertini, D.; Aldave, D.A.; Algieri, L.; Ali, N.; Almqvist, A.; et al. The Surface-Topography Challenge: A Multi-Laboratory Benchmark Study to Advance the Characterization of Topography. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlaček, M.; Podgornik, B.; Vižintin, J. Correlation between Standard Roughness Parameters Skewness and Kurtosis and Tribological Behaviour of Contact Surfaces. Tribol. Int. 2012, 48, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorin, R.; Capitanu, L.; Badita, L. A qualitative correlation between friction coefficient and steel surface wear in linear dry sliding contact to polymers with SGF. Friction 2014, 2, 47–57. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40544-014-0038-2 (accessed on 17 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Unal, H.; Mimaroglu, A. Friction and Wear Behaviour of Unfilled Engineering Thermoplastics. Mater. Des. 2003, 24, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, A.J.; Ferreira, E.C.; Pouzada, A.S. The Effect of Temperature and Surface Roughness on Coefficient of Friction between Thermoplastics and Molding Surfaces. In Proceedings of the Regional Meeting of the Polymer Processing Society, Florianopolis, Brazil, 7–10 November 2004; pp. 193–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T.; Koga, N.; Shirai, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Toyoshima, A. An Experimental Study on Ejection Forces of Injection Molding. Precis. Eng. 2000, 24, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meine, K.; Schneider, T.; Spaltmann, D.; Santner, E. The Influence of Roughness on Friction Part II. The Influence of Multiple Steps. Wear 2002, 253, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Browning, R.; Fincher, J.; Gasbarro, A.; Jones, S.; Sue, H.-J. Influence of Surface Roughness and Contact Load on Friction Coefficient and Scratch Behavior of Thermoplastic Olefins. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 4494–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.R.; Friesenbichler, W.; Freudenschuss, G. A New Practical Measurement Apparatus for Demolding Forces and Coefficients of Friction in Injection Molding. In Proceedings of the Polymer Processing Society, Salerno, Italy, 15–19 June 2008; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.