Abstract

Digital twin and artificial intelligence (DT-AI) technologies present hitherto unheard-of possibilities for dynamic production scheduling in smart manufacturing. Nevertheless, a careful examination of several studies reveals significant gaps in the current state of the discipline. This paper attempts to review advancements, gaps, and opportunities in the areas of DT-AI-based production scheduling. Articles chosen for this literature analysis were mostly published within the last eight years. Based on the literature, five enabling challenges that are consistently considered in the literature include Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions, High System Complexity, Real-Time Data Management, Integration and Interoperability, and Adaptability and Generalizability. This review not only identifies these enabling challenges but also provides tailored outlines of progress and future directions. The findings pave the way for resilient, scalable, and interpretable DT-AI systems for production scheduling that can handle uncertainty and optimize output in real time. DTs and AI can benefit manufacturing with data-driven intelligent planning and decision-making as well as model-based systems engineering principles. This review examines these advancements and trending research directions in production scheduling.

1. Introduction

The theoretical foundation for dynamic rescheduling has been evolved from original scheduling ideas and algorithms to a vital concept of manufacturing with complexity and disruptions [1]. Monitoring, control, optimization, and planning are made possible by a digital twin (DT), which functions as a virtual equivalent of a physical system or process. DTs facilitate real-time monitoring, control, planning, simulation, and optimization as virtual counterparts of physical systems and entities. Physical systems and entities are interfaced with digital systems, through which we can track, analyze, and manage their operation. An ability to capture a virtual representation of the constituent parts and manufacturing systems is becoming more and more complicated, customized, and uncertain in a highly dynamic market. A production system is challenged at every step to deliver a product of better quality and lower prices. Predetermined production schedules can be seriously disrupted by variables including unanticipated material shortages, machine failures, urgent new orders, quality issues, and shifting demand trends. Understanding demand versus capacity is crucial for sales and revenue since a misunderstanding may lead to production delays, higher operating costs, lower customer satisfaction, etc. Reviews on dynamic scheduling [2,3] have pointed out how important it is to minimize these interruptions.

DT models virtually emulate actual (physical) production lines with the Internet of Things (IoT) [2,3]. Traditional static scheduling in a dynamic context is limited by the lack of flexibility and relational adaptation. Heuristic rules frequently fail to adequately handle dynamic and stochastic situations, and more advanced tools are needed to address such dynamics in the context of digital manufacturing [4]. Production scheduling needs to adapt to interruptions like material shortages, quality issues, machine failures, workorder changes, and resource limitations with the use of DTs and artificial intelligence (AI) for proactive and closed-loop rescheduling [5,6].

Rescheduling is a response to disruptions like inventory shortages, equipment breakdown, unscheduled downtimes, and workorder changes caused by machine or material issues. This could occur due to a system versus a physical inventory mismatch or an issue in the bill of material (BOM). Production rescheduling is crucial for preserving throughput and reducing downtime to utilize the equipment to achieve the maximum efficiency. Manufacturers can collect all sorts of data from products as well as processes with the use of sensors [7], which will eventually help them improve production efficiency and throughput.

Conventional scheduling techniques, such as mathematical programming, rule-based heuristics, and metaheuristics, can have large processing costs and little flexibility. Traditional techniques find it difficult to handle dynamic situations with potential flaws, where there is a lot of variations that cannot be controlled immediately. Data-driven models are able to predict future disruptions, such as resource outages. Also, any issues related to BOM can be identified proactively, and then the best course of action can be taken to solve the issue based on past data using DT-AI-based production scheduling [8]. Nevertheless, despite the growth of DT-based frameworks, most research focuses on predictive maintenance, such as preventive maintenance (PM) or total productive maintenance (TPM), instead of rescheduling the entire production [9,10]. Full-scale production rescheduling under uncertainty is rarely addressed by static optimization techniques. In an uncertain shop floor environment, AI-driven rescheduling performs better than static scheduling, according to recent reviews [11,12]. Specifically, multi-agent Reinforcement Learning (RL) reduces tardiness by 10–18% during machine downtimes caused by failures, while Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) reduces the makespan by 8–10% for random arrivals of workorders.

Many product performances are considered in the design and testing stages, which is where the DT is utilized. Scalable computation and data storages are made possible by cloud systems and the Internet of Things (IoT). Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs) offer digital control of physical processes. Recent research has looked at the scheduling and optimization with Big Data Analytics (BDA), AI, and cloud systems [13]. Industry 4.0 has ushered in a new era of digital manufacturing for equipment data monitoring in real time. The data is examined in order to enhance the design parameters, identify adjustments during operation, and raise the overall efficiency of equipment [5,6]. AI and DTs are revolutionizing production through creating a realistic virtual replica of a system, process, asset, or function. DT modeling and analysis benefit digital manufacturing through simulation to validate new production plans before deployment. Digital engineering can be utilized to give feedback and identify or forecast anticipated failures or errors that may occur. DTs offer real-time monitoring, simulation, prediction, and optimization throughout their existence, which will enable effortless design modifications, preventative maintenance, and predictive maintenance [14,15].

In the era of digitalization, CPSs allow real-time synchronization between physical and digital twins to facilitate an unprecedented level of visibility and control over manufacturing operations. AI methods like Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Reinforcement Learning (RL) advance manufacturing, but future manufacturing relies heavily on a number of other novel technologies besides AI. Predictive insights are supported by BDA, and connectivity across devices is made possible by IoT, cloud computing, CPSs, and DTs. AI offers powerful capabilities for intelligent decision-making, pattern recognition, and autonomous learning from complex data, which reduces costs associated with efforts like redesigning production, handling uncertain events, preventing failures, etc. Industry 4.0 enables advanced manufacturing and smart supply chain networks along with digitalization, integration, and automation [16,17]. However, scheduling challenges still remain unaddressed since DT-AI-based dynamic production rescheduling is in its early infancy. Despite significant promise and expanding knowledge in this interdisciplinary field, it is still challenging to integrate DT modeling and AI into production scheduling in a way that is adaptive, flexible, scalable, and smooth for real-time, autonomous rescheduling, even though each technology has made progress on its own. Manufacturing enterprises are integrating such advanced technologies into their businesses in an effort to stay competitive [18]. Additionally, a rising number of businesses are integrating generative AI and service-oriented reasoning into their operations to improve decision-making and transparency and maintain competitiveness on markets that are becoming more and more dynamic [19].

The goal of this literature review is to present a comprehensive overview of recent research findings in the areas of DT-AI-assisted production scheduling. The research findings are assessed in terms of key technical challenges, such as Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions, High System Complexity, Real-time Data Management, Integration and Interoperability, and Adaptability and Generalizability. These technical challenges were chosen based on the popularity among the subject-matter literature.

The remaining sections are organized in the following way. Section 2 introduces key technical challenges to production scheduling. Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 present the literature review analysis of the selected articles by highlighting advancements and future research opportunities in the areas of production scheduling with emphases on AI and DTs. Section 9 provides a summary.

2. Methodology

Digital manufacturing involves online monitoring, tracking, and coordination of overall production using digitalization that offers numerous benefits as well as vulnerabilities like cybersecurity threats. Nowadays, digital manufacturing often depend on Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems and AI, which enable intelligent production rescheduling based on real-time collection of information from various sources like interconnected digital devices, machineries, and production systems. For instance, Schedulenet [20] and other AI-based scheduling techniques offer efficiency and productivity in rapidly evolving circumstances through intelligent data-driven planning that efficiently arranges product deliveries from suppliers to customers.

In this study, a multi-database search strategy was employed to identify a large number of publications in the areas of advanced production scheduling. The Scopus and the Web of Science were the main databases used along with digital libraries of IEEE Xplore and ScienceDirect. To guarantee transparency and reproducibility, the review adhered to the criteria of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The search queries were first carefully crafted utilizing a range of keywords related to the primary concepts of this review. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were deliberately applied to refine the search results. Search terms include “Digital Twin”, “DT”, “Big Data “, “Artificial Intelligence”, “AI”, “Machine Learning”, “ML”, “Deep Learning”, “DL”, “Reinforcement Learning”, “RL”, “production scheduling”, “manufacturing scheduling”, “job shop scheduling”, “flexible manufacturing system scheduling”, “rescheduling”, “dynamic scheduling”, “real-time scheduling”, “adaptive scheduling”, “disruption management”, and “smart manufacturing”. The increasing complexity of modern production environments, which are characterized by real-time disruptions, machine downtime, material shortages, resource limitations, dynamic demand, and quality issues, needs more research and adaptive solutions.

An exclusion table was used to describe the literature selection procedure in order to guarantee transparency and reproducibility. The excluded sources, which include maintenance-only DT applications, non-manufacturing domains, AI scheduling without DT integration, and broad DT principles without scheduling consequences, non-peer-reviewed publications, and duplicates, are clearly summarized in Table 1 along with the reasoning for their exclusion.

Table 1.

An overview of the sources and justifications for exclusion.

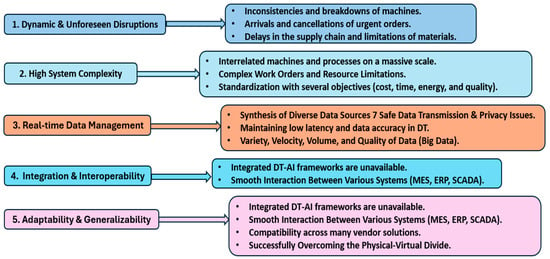

AI methods, particularly ML and RL, have grown in popularity as a means of addressing production scheduling problems. To improve scheduling effectiveness, machine uptime, operating costs, changeovers, and overall productivity, researchers and practitioners are looking into novel and data-driven decision-making methodologies. To reflect recent developments in production scheduling, we mainly chose articles published between 2018 and 2025. The main technical challenges outlined in Figure 1 include High System Complexity, Real-time Data Management, Integration and Interoperability, Adaptability and Generalizability, and Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions. These challenges were selected in accordance with their popularity among the subject-matter literature. Through extensive research, we identified a sizable number of papers, which were then assessed in terms of these technical challenges.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates production scheduling challenges.

Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions: Production may experience unforeseen real-time disturbances, such as unexpected machine slowdowns, malfunctions, and downtimes, sudden workorder arrivals, cancelations, and modifications, supply chain delays, and raw material limitations.

High System Complexity: The inherent complexity of contemporary manufacturing is the subject of this challenge, which involves complex production lines with various machines and processes on a massive scale, complex workorders and tasks with constraints on resources and standardization, and multiple optimization goals. These operational and system complexities require advanced planning methods to deal with [21].

Realtime Data Management: Real-time data management plays an essential role in monitoring, control, and data-driven decision making. It consists of various information processing aspects including data acquisition, formatting, pre/post-processing, synthesis, communication, distribution, data analytics, privacy, security, and storage.

Integration and Interoperability: Smooth integration of multiple components is essential to the successful deployment of manufacturing systems, which necessitate interoperability between various hardware, software, and diverse platforms. Making sure that every component of the system can function as a whole is an essential challenge to overcome.

Adaptability and Generalizability: Achieving production scheduling that is adaptive and generalizable is an essential challenge to address in manufacturing. Manufacturing and the supply chain may experience various unexpected disruptions and dynamic conditions to deal with, which necessitate production rescheduling that is adaptive and generalizable.

Production scheduling plays an essential role in manufacturing and supply chain management. This literature review focuses on production scheduling with novel DT-AI-based frameworks for complex, dynamic production settings. However, research articles on production scheduling without integration of AI and DTs were excluded. Preliminary works, such as preprints or workshop papers that have not been peer-reviewed, were usually eliminated unless peer-reviewed sources specifically cited them. Furthermore, studies that used DT-AI frameworks for scheduling in non-manufacturing domains, such as logistics [22] and healthcare, were excluded unless they proposed highly transferable methodologies that are directly applicable to production scheduling. Because of their immediate significance, studies like the work done by Chen et al. [23] on dynamic scheduling with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and cloud manufacturing were kept. Duplicate sources in different databases were meticulously removed.

The initial screening procedure involved a thorough review of abstracts and titles followed by a full-text review to confirm their suitability based on established criteria. More than 50 pertinent papers were accurately selected for in-depth analysis in an iterative manner with refined search strategies in every iteration. The selected papers were grouped into specific categories including job shops [19,24,25,26,27] with emphases on reducing tiredness and makespan; flexible manufacturing systems [24,25,27,28,29] with emphases on flexibility and resource allocation; assembly lines [14,15,17,30,31,32,33] with emphases on sequencing and throughput. These studies discuss how DT-AI-based scheduling frameworks help improve throughput, sequencing efficiency, flexibility, optimal resource allocation, and makespan. To maintain transparency, complete bibliographic information was methodically documented [34].

High-fidelity twins and strong synchronization with ERP and sensor data are crucial for dependable rescheduling according to studies on DT integration [4,7,8,16,18,25,26,32,35,36]. These studies demonstrated how real-time synchronization lowers latency and state drift, allowing for precise shop floor condition modeling. On the AI side, DRL methods [23,27] regularly reduce makespan by 8–15% and tardiness by 10–18% in flexible job shops when compared to static heuristics, while RL approaches [19,25,36] show increased reactivity to interruptions. Other AI algorithms [14,15,29] balance throughput, cost, and energy consumption in multi-objective optimization. These studies suggest that AI-based solutions can offer adaptive scheduling policies under uncertainty, but they necessitate DTs with fidelity and synchronous data streams. Makespan minimization [7,8,19,24,25,26,27,28,29], tardiness reduction [19,37], and energy efficiency [22,24] were among the top challenges in the literature, where machine breakdown [27] and the arrival of urgent orders [19,28] were examples of disruption scenarios. When taken as a whole, these studies show how DT-AI-based frameworks are used in practical shop floor settings based on the type of scheduling/rescheduling problems.

A crucial component of this literature review encompasses the stated limitations and future research in DT-AI-based production scheduling since they often offer lucid insights into existing research gaps. The retrieved data were then synthesized using a comprehensive theme analysis in conjunction with production scheduling challenges in Figure 1 as well as research gaps associated with DT scalability, synchronization, and fidelity [4,7,8,16,18,25,26,29,32,35,36]. The analysis also considered unresolved issues like latency in real-time data flows, restricted generalizability of AI policies, and difficulties integrating DT designs across heterogeneous systems.

In order to identify highly relevant technologies or concepts, such as explainable AI, Federated Learning, Blockchain, Quantum Computing, and Human DT, that have not yet been sufficiently integrated into DT-AI-based production rescheduling, an interdisciplinary lens was used for drawing insights from broader technological trends into this study. Implicit industrial needs, such as the demand for human oversight, data privacy, and the ability to handle intractable practical problems, also informed the identification of areas where current research might not yet meet industrial demands. This comprehensive analysis ultimately led to the formulation of this literature review with production scheduling challenges, advancements, and concrete suggestions for future research directions. This systematic and analytical methodology ensured that the identified research gaps and future opportunities are well-justified and relevant.

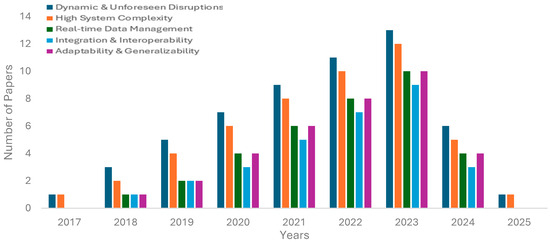

Figure 2 presents yearly distributions of published studies on five major topics of DT—AI-based production scheduling, which include Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruption, High System Complexity, Realtime Data Management, Integration and Interoperability, and Adaptability and Generalizability. According to the chart, publications increased steadily starting in 2017 and peaking in 2023. Despite advancements in IoT and cloud infrastructure, there is comparatively steady development in “Realtime Data Management” perhaps due to ongoing difficulties with data fusion and latency.

Figure 2.

This figure presents trends in the selected articles.

Significant progress has been made in tackling the dynamic and inherently complicated nature of contemporary production scheduling and rescheduling perhaps thanks to the convergence of DTs and AI. The main developments in the literature are discussed in detail in the remaining sections along with the prospects they present for improving manufacturing autonomy, efficiency, and resilience.

3. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins for Production Scheduling

3.1. Introduction to DT-AI-Based Production Scheduling

An artificial neural network is a fundamental cornerstone of AI. Artificial neural networks can learn from data and make intelligent predictions for production scheduling to enhance its performances. They can efficiently predict complex dynamics of manufacturing because of their capacity to learn subtle, non-linear relationships from large datasets. Neural networks can be used in production scheduling to anticipate changes in demand, allocate resources optimally, and adjust to interruptions in real-time. High-dimensional input data, including inventory levels, job priorities, and machine conditions, can be processed by neural networks to produce precise forecasts and guide wise scheduling choices.

Depending on DT application areas, researchers differently define a DT. The majority of researchers characterize a DT by three primary components: a virtual twin, a physical twin, and a data link that inextricably connect the physical and digital twins [14]. One essential and vital instrument that makes it possible to closely integrate digital data and physical resources is the DT technology. A DT is a term for the digital representation of a physical product, asset, process, or system that is used to describe and model its digital counterpart. It can precisely depict the behavior and current condition of its physical twin, enabling analysis, prediction, and optimization of production and manufacturing processes. A digital model is a representation of a physical thing, either planned or existing, that is created digitally without the use of automatic data interchange between the two. A more thorough description of an actual object may be included in its digital depiction. Such descriptions could be mathematical models of new products, simulation models of planned factories, or any other representation of a physical entity that does not take advantage of automatic data integration. For the creation of such models, digital data from physical systems that are already in place may still be used, but all data transmission is performed manually [17].

DTs are a new generation of modeling, simulation, and optimization technologies that not only highlight the value of virtual space simulation prior to production but also enable intelligent operations and interaction between virtual and physical twins during production [15]. The growing implementation of real-time measurements and operational data makes it possible to produce increasingly detailed live DTs for production. In this manner, deviations and defects can be promptly addressed, or the systems themselves can start countermeasures in cyber-physical production systems [16]. More robustness and stricter quality standards and specifications are made economically feasible by organizational strategies and planning [14].

DT fidelity is quantitatively defined across three dimensions: (i) Model Granularity—the first dimension that represents the levels of physical and behavioral details; (ii) Synchronization Rate—the second dimension that represents the synchronization time interval between physical and virtual twins; and (iii) Semantic Completeness—the third dimension that represents the extent of standardized data and ontology integration. Fidelity is classified into low, medium, and high levels with clear thresholds based on these dimensions. Higher fidelity often increases dispatch accuracy and decreases rescheduling under disruptions at the cost of increased data and processing needs. Table 2 presents these levels and their effects on scheduling performances.

Table 2.

Quantifiable DT fidelity levels and their consequences for scheduling performance.

Real-time data management is further substantiated here using explicit quantitative thresholds determined from the studies studied. To ensure reproducibility and clarity, we describe operational ranges for latency, synchronization skew, allowable error margins, and packet loss tolerance. These numbers illustrate the trade-offs between computational overhead and responsiveness and mirror real-world needs observed in DT-AI-based scheduling situations. Table 3 presents these levels and their effects on the performances of production rescheduling.

Table 3.

Quantifiable criteria for real-time management of data in DT-AI-based rescheduling.

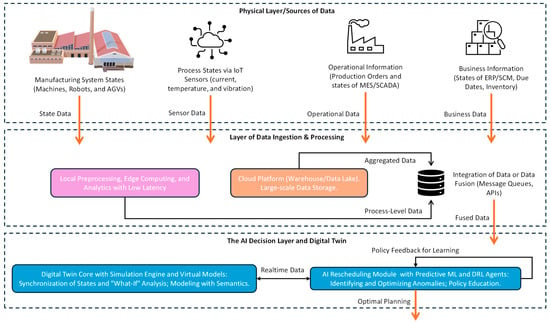

Researchers [38,39,40] have been proposing the integration of DTs and AI into dynamic production rescheduling to bring together DT modeling and orchestration with real-time data as well as AI-based decision-making and planning. The integrated structure of dynamic production scheduling consists of the following layers:

- Physical-Virtual Synchronization Layer: Sensors and data logging provide real-time data for shopfloor control, MES, ERP, Supply Chain Management (SCM), and data clouds. Data clouds store curated info in a data lake, while edge nodes filter and preprocess.

- DT Core Layer: High-fidelity models facilitate the creation of “what-if” scenarios, maintain semantic context (e.g., asset administration shells), and synchronize with the physical system. For each asset class (machine, process, or flow), fidelity can be adjusted.

- AI Decision Layer: Hybrid planners include metaheuristics for local optimization, supervised ML for estimated-time-of-arrival prediction or anomaly detection, and DRL for dispatching policies. Under resource limitations, including setup times, transportation delays, and personnel availability, policies are updated online.

- Integration and Orchestration Layer: Protocol compatibility is guaranteed via middleware like OPC UA. Plug-and-play modules are made possible by common data models and standardized Application Program Interfaces (APIs). Transparency is enforced by explainable AI gateways.

- Human-in-the-Loop Governance Layer: Humans are involved at some point in the AI workflow to ensure accuracy, safety, accountability, and ethical decision-making during each rescheduling cycle.

Table 4 presents some studies on DT-AI-based production scheduling with medium-or-high-level fidelity, wherein DRL-based AI methods consistently produced solid performances.

Table 4.

DT-AI-Based Production Rescheduling Studies.

3.2. Industrial Applications of DT-AI-Based Production Scheduling

The integration of AI and DTs into production scheduling has started to transition from theoretical frameworks to practical applications. DT-AI systems have been tested by a number of businesses to increase the effectiveness of scheduling and rescheduling. For instance, worker allocation was optimized in real time to minimize bottlenecks and increase throughput of an assembly workshop via DT-driven dynamic scheduling as demonstrated by Ref. [37]. DRL-based dynamic scheduling of random workorder arrivals in cloud manufacturing [23] showed that DT-AI can manage random workorder arrivals with enhanced makespan performances. In a similar vein, researchers [44] described the application of DT for anomaly detection in job shops, allowing for proactive rescheduling in the event of disruptions. These studies indicate that integration of DT and AI into production scheduling in industrial settings has the potential with quantifiable advantages.

Given these accomplishments, businesses nevertheless encounter a number of implementation-related difficulties. Because disparate MES, ERP, and SCADA frequently lack semantic alignments, which cause integration delays and data governance issues, when DT models are implemented over large production networks, latency and scalability problems occur, particularly when cloud-based solutions add communication costs. The requirements for explainable AI overlays are highlighted by the fact that opaque AI-based scheduling decisions reduce acceptability and trust of the operator. Another issue is return on investment (ROI), since businesses have to weigh the expense of developing sensors and training AI against observable increases in productivity. In addition to technological innovation, organizational tactics, e.g., staggered rollouts, personnel training, and adherence to safety and regulatory standards, are necessary to address these problems.

While the merging of DTs and AI holds great potential for dynamic production rescheduling, there are still a number of research obstacles. These flaws point to areas that need to be optimized and improved before DT-AI-based systems reach full industrial maturity. First, maintaining the DT integrity is a recurring problem. Building and updating high-fidelity twins require substantial resources, and accuracy is decreased over time due to parameter drift. Reliability is really limited by inadequate data and model degradation, despite the fact that much research assumes perfect synchronization between physical and virtual systems [14,37]. Second, problems with data governance and data quality limit the overall performance. Noise, missing numbers, and incompatibility between MES, ERP, and SCADA are common in real shopfloor data. Scheduling decisions have the danger of being erroneous or delayed in the absence of thorough cleansing and semantic alignments [23,44]. Third, AI models’ capacity for generalization and adaptation is still restricted. When product mixtures or routing rules change, DRL policies sometimes overfit particular shop configurations and deteriorate. Models are brittle during distribution shifts because transfer learning and meta-learning techniques are currently understudied in manufacturing environments [23]. Fourth, trust and explainability are not enough. The majority of AI scheduling algorithms function as “black boxes,” which undermines operator trust and makes regulatory compliance more difficult. To increase acceptance and transparency, explainable AI overlays and human-in-the-loop techniques are required [46]. Fifth, there are still issues with integration and scalability. Current DT-AI systems frequently rely on centralized structures and proprietary interfaces, which restrict interoperability and raise latency in large-scale deployments. Industrial rollouts are still hampered by vendor lock-in and protocol fragmentation [14,37].

These drawbacks demonstrate that, despite the potential of DT-AI-based rescheduling, more work is necessary for production scheduling to enhance fidelity, data governance, adaptability, explainability, and scalability. In order to transition from laboratory prototypes to reliable industrial practice, several issues must be addressed.

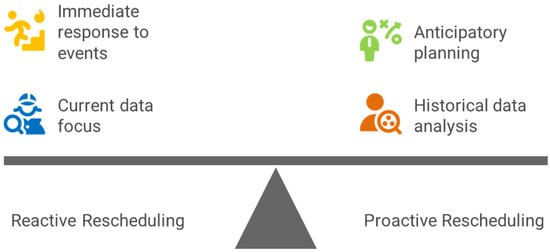

4. Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions

4.1. Advancements

Machine failures, urgent order arrivals, material shortages, and quality deviations are examples of real-time disruptions that are unpredictable and difficult for traditional scheduling approaches to handle [2,3,47,48]. Significant progress has been achieved in enabling quick, clever, and flexible reactions to these unanticipated situations thanks to DT-AI integration. By continuously gathering data from sensors and current systems, DTs give vital real-time visibility into the state of the shop floor. This enables prompt disruption identification and precise evaluation of the impact of interruptions on the present schedule [4,18]. This real-time data allows the system to adopt adaptive rescheduling policies, especially when paired with sophisticated AI algorithms, like DRL. To reduce the impact of disruptions on important performance metrics like makespan, tardiness, and resource utilization [43,49,50]. The DRL agents can be trained to dynamically choose the best dispatching rules (e.g., Shortest Processing Time, Earliest Due Date) or create completely new schedules in milliseconds [19,29,37,49]. Research indicates that when disruptions arise in robotic assembly lines and flexible job shops, DT-AI frameworks perform better than static and heuristic approaches. For instance, multi-agent RL reduces tardiness by 10–18% during machine failures [36], while DRL reduces makespan by 8–15% under random urgent orders [23]. Shorter lead times and increased robustness in DT-AI scheduling are confirmed by several comparative evaluations. When taken as a whole, this data shows that DT-AI integration offers a quantifiable increase in efficiency and resilience in the face of upheaval, by demonstrating better overall system performance, shorter lead times, and more robustness when compared to static or heuristic methods. Before committing to a physical change, the DT’s real-time “what-if” scenario simulation enables the evaluation of several rescheduling possibilities and the prediction of their results, greatly reducing the risk of the decision-making process and facilitating informed human oversight [4,18,51]. Additionally, when anomaly detection methods are combined with DTs, they can automatically spot operations that deviate from the plan, prompting AI-driven reactions right away [43]. Significant progress has been made in managing unpredictable and dynamic disruptions in production scheduling as a result of the combination of DT and AI. DT-AI frameworks are made for both proactive and reactive adaptation, in contrast to standard static scheduling techniques, which are fragile and fall short when confronted with real-world complexity. The main factor behind these developments is DT’s capacity to deliver a high-fidelity, real-time model of the physical system, serving as a dynamic data source for clever scheduling algorithms. DT’s ability to monitor and detect anomalies in real time is a major improvement. The DT can quickly spot schedule violations like machine failures, shifts in job priorities, or unexpected shortages of raw materials by continuously gathering data from sensors on the actual factory floor. This immediate awareness represents a significant shift from manual reporting-based previous systems, which frequently result in delays and cascading interruptions. The DT supplies the information required to start an AI-driven rescheduling mechanism as soon as an abnormality is identified. The AI’s capacity to process real-time DT data and produce new schedules is the fundamental component of this development. Research in this area is trending towards a hybrid approach that combines reactive and proactive strategies, as shown in Figure 3. The integration between proactive and reactive rescheduling is seen in Figure 3. Proactive techniques use past patterns to predict problems, whereas reactive tactics use current data to respond to disruptions. The DT-AI system can decrease delays and increase responsiveness by combining the two. The most popular method is reactive rescheduling, in which an unexpected event sets off the AI to “repair” the current plan right away. For example, the AI can minimize the impact on the overall production timeline by rerouting the affected jobs to an available machine in the event of a machine failure.

Figure 3.

Rescheduling for finding a balance between reactive and proactive planning.

In order to swiftly identify new workable solutions after a disruption, hybrid genetic algorithms and tabu search have been investigated in papers. Proactive Rescheduling: This more sophisticated tactic makes use of DT’s capacity for prediction. The AI can foresee such disturbances before they happen by examining past data and the state of the system today. The ability to rapidly generate and evaluate a wide range of scheduling scenarios within the DT’s virtual environment is a crucial step in this process, ensuring that the updated schedule is dependable and optimal.

The stochastic nature of manufacturing environments, where machine failures, urgent order arrivals, and supply chain delays happen at random, is the primary cause of dynamic disruptions. Due to their lack of real-time adaptive capabilities, traditional static scheduling techniques might cause bottlenecks when related operations are disrupted. Inadequate downtime prediction models, restricted anomaly detection, and the lack of closed-loop feedback between DT and AI systems are examples of technical impediments. While RL can adjust to random arrivals, scalability and latency still remain as issues according to studies conducted by Chen et al. [23] and Li et al. [44].

4.2. Opportunities

Developing extremely resilient, self-healing, and proactive manufacturing systems is made possible by the capacity to react quickly to interruptions. Going beyond merely reactive rescheduling to proactive mitigation, future research can concentrate on developing AI models that can foresee possible disruptions using complex predictive analytics drawn on historical and real-time DT data. In the last-mile logistics, for instance, Fadda et al. [51] showed how ML and optimization may be coupled to predict next-day delivery demand, allowing tactical capacity planning under uncertainty. This involves using ML models in the DT to estimate demand changes [51], identify possible supply chain bottlenecks, or predict equipment breakdowns. This enables proactive schedule adjustments before disruptions fully manifest. Additionally, there is a great chance to develop hierarchical, multi-level rescheduling strategies in which AI manages localized, immediate disruptions on the shop floor. These higher-level planning systems use aggregated DT data to inform more comprehensive strategic changes for the entire supply chain or the enterprise [14]. Additionally, DT-AI integration can enable “lights-out” or highly autonomous rescheduling, which minimizes human intervention and is mainly saved for exceptional, extremely complex, or safety-critical scenarios [24,25]. This allows human operators to focus on higher-value tasks like innovation, process improvement, and strategic decision-making [14,24]. Another important research opportunity is the creation of reliable measurements and simulation environments for measuring system adaptability and resilience in the face of various and complex disruption patterns [24,25].

5. High System Complexity

5.1. Advancements

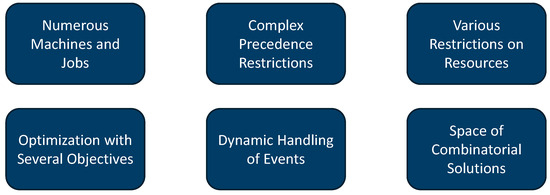

Manufacturing systems are intrinsically complex, with many interconnected machines, complex job precedence constraints, a variety of resource limitations (such as tools, fixtures, energy, and operators), and several competing goals (such as maximizing quality and machine utilization while minimizing makespan, cost, and energy) [48,52,53,54]. By offering a thorough and integrated perspective of the entire production ecosystem, DT-AI has shown great potential in controlling this inherent complexity. High-fidelity virtual models that faithfully depict complex interdependencies, dynamic behaviors, and real-time states of physical assets and processes are hard to depict with conventional static math models but can be emulated by DTs [4,35,36]. The enormous and combinatorial growth of the solution space that comes with complicated scheduling issues can be successfully navigated by AI, particularly DRL. The ability of AI to learn efficient policies for highly constrained and dynamic environments has been demonstrated by researchers via a successful application of DRL to Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSSP) with dynamic resource constraints [28], sequence-dependent setup times [19], and multi-objective optimization [19,26,37,51,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. By utilizing their individual strengths in exploration and exploitation, hybrid approaches that combine the advantages of AI techniques (such as genetic algorithms or tabu search) can be developed. The conventional optimization methods have also demonstrated superior effectiveness in addressing complex and large-scale problems [44,63]. Modern manufacturing’s high system complexity, which is typified by a large number of machines, a variety of task kinds, and complicated dependencies, presents a major obstacle for conventional scheduling techniques. Because of these systems’ immense size and non-linear interactions, traditional optimization approaches are computationally unfeasible. AI and DT frameworks are being developed in response to increasing complexity, shifting from centralized, monolithic control to a decentralized, distributed, and scalable approach. The application of multi-agent systems (MASs) is a crucial complexity management tactic. This method represents every resource, job, or machine as an intelligent agent inside the DT.

To make local scheduling decisions that advance the global goal, these agents work independently, interacting and negotiating with one another. The computational bottleneck caused by a single central scheduler trying to address the entire problem at once is avoided by this distributed control design. Because an agent can respond to local changes without waiting for a comprehensive system-wide re-evaluation, this approach enables increased adaptability and resilience. The application of a DT-based method for job shop anomaly detection and dynamic scheduling is examined in a paper by Li et al., emphasizing the function of distributed systems in managing complicated situations [44]. Cloud-edge architectures that are scalable are being used by DT-AI frameworks to handle the massive volumes of real-time data produced by intricate industrial processes. For time-sensitive operations, edge computing allows for low-latency control and instantaneous decision-making by processing data locally at the machine level. At the same time, the cloud offers the storage and processing capacity required for training advanced AI models, analyzing historical data, and performing intricate, long-term predictive analytics. The system is guaranteed to be responsive and able to manage a large data load thanks to this hybrid architecture. Figure 4 presents AI and digital twinning for complex production scheduling. Complexity of production scheduling, such as multi-machine coordination to handle multiple jobs, complex job precedence constraints, various restrictions on resources, multi-objective optimization, dynamic handling of events, and limits of combinatorial solutions, are shown in Figure 4. These interdependencies can be modeled, and vast solution spaces can be effectively explored by AI, DTs, and metaheuristics.

Figure 4.

Complexity of production scheduling.

The architectural specification for intelligent manufacturing systems is described by Tao et al. [45]. One potent AI paradigm that works well in high-complexity settings is RL. Through direct interaction with the DT’s virtual world, an RL agent discovers the best scheduling strategies through trial and error rather than depending on a predetermined set of rules. When the RL agent makes wise choices, it is rewarded; when it makes bad choices, it is penalized. This makes it possible for the machine to find extremely efficient, counterintuitive scheduling techniques that would be challenging for a human to create. We can see this with optimization techniques using hybrid models, which can maintain very complex issues which will be related to the floor production scheduling and the mode of moving the materials.

Hundreds of machines, intricate routing rules, and multi-objective optimization goals (Cost, quality, energy, and time) are all part of modern manufacturing systems. The combinatorial explosion of scheduling states, which increases exponentially with system scale, is the primary source of complexity. The high computing cost of optimization techniques, the challenge of modeling heterogeneous resources, and the absence of standardized DT structures are examples of technical constraints. The necessity for hierarchical and modular DT frameworks was highlighted by Gao et al. [37], who showed that even DT-driven assembly scheduling struggles with worker allocation when objectives conflict.

5.2. Opportunities

Rather than focusing only on particular lines or shops, the improvements in managing complexity open the door to improving entire manufacturing networks and supply chains. The development of hierarchical DT-AI systems presents opportunities for distributed and coordinated rescheduling throughout an extended supply chain or entire enterprise, where various DT levels (e.g., machine-level, shop-floor level, factory-level, and enterprise-level) feed into a multi-agent AI system. Li et al. [64] show how DRL can be used in high-complexity contexts and show that it can learn from extensive simulation data, even if this methodological approach is just getting started in manufacturing. AI’s capacity to learn from enormous volumes of DT-generated simulation data offers a previously unheard-of chance to find new dispatching rules.

The scheduling heuristics outperform human-designed rules for particular complex scenarios, possibly producing counterintuitive but incredibly effective solutions. More balanced and sustainable rescheduling decisions consider not only efficiency but also energy consumption, environmental impact, and worker well-being. These can result from the direct integration of multi-objective optimization within AI frameworks, continuously guided and validated by DT simulations [24], and enable dynamic, data-driven decision making in supply chain environments [22], guided by BDA. Beyond deterministic assumptions, research into resilient optimization approaches within AI for managing stochastic aspects and deep uncertainty in complex systems continues to be a fruitful area.

6. Real-Time Data Management

6.1. Advancement

The availability of precise, timely, and thorough real-time data is essential for efficient production rescheduling in dynamic contexts. By creating a constant, two-way data flow between the actual and virtual worlds, DT technology has completely transformed real-time data management in manufacturing [4,18,25,36,41]. The development of reliable data acquisition mechanisms from a variety of IoT sensors (such as machine status, product tracking, environmental conditions, and operator performance) and smooth integration with current SCM platforms, ERP systems, and MES are creating improved solutions. Advanced data fusion techniques to produce an accurate and comprehensive digital representation of the physical system are some examples of advancements [32,35,54,65,66,67]. These integrations enable sophisticated data fusion methods that produce real-time, high-fidelity digital representations of physical systems, which serve as the basis for intelligent decision-making in smart manufacturing [31,33,65]. This comprehensive, real-time data stream gives AI models the precise, up-to-the-minute information they need to recognize abnormalities in the production system’s present condition and make context-aware, well-informed rescheduling decisions [18,25,43]. This real-time synchronization requires the ability to manage the high velocity, volume, and variety of data (Big Data features), which allows for a complete operating picture [68]. When taken as a whole, these advancements highlight how crucial DT-enabled synchronization is to attain robust, adaptable, and intelligent production control.

The effective management of real-time data, which is essential for the virtual model to accurately replicate the physical system, is a major challenge in developing a successful DT. A robust data management system is required due to the vast amount, velocity, and variety of data collected by multiple sensors located throughout a production facility. Real-time sensor fusion, a technique that combines data from multiple sensor types to create a more comprehensive and reliable depiction of the system’s condition, is one noteworthy advancement.

Additionally, DT-AI systems are using edge computing more and more for data pre-processing and filtering in order to handle the enormous velocity of this data. In order to minimize network latency and eliminate unnecessary data before it is transmitted to the cloud, this entails analyzing data right on the production floor, near the source. Last but not least, real-time data streams must be secure and intact. The risk of cyberattacks rises with the interconnectedness of production systems. To counter this, sophisticated frameworks include strong security features, like decentralized ledgers and encryption, to guarantee the data’s integrity and immutability. In this physical layer and source of data, we can see that we have 4 different states of data. The first one is state data, sensor data, operation data, and business data. Then, we have a second layer, which is a layer of data processing. We receive data from physical layers, like manufacturing plants. In this layer, edge computing and cloud platforms will be built to store the data at the processing level and integrate the data. Figure 5 depicts real-time technical data flow rescheduling with DT-AI methods.

Figure 5.

Realtime Technical Data Flow Rescheduling with DT-AI methods.

Data flows of DT-AI-based production scheduling are shown in Figure 5. It demonstrates how data is gathered from the physical layer, analyzed via cloud and edge platforms, and then used to make planning and decisions. The shopfloor data speed, amount, and diversity are the main causes of data management issues. DT fidelity is decreased by inadequate data, sensor noises, and transmission latency between physical and virtual systems. Inadequate semantic alignments between MES, ERP, and SCADA as well as restricted edge computing capability for low-latency decision making are examples of major technical constraints. According to Tao et al. [14] and Shi et al. [46], AI models exhibit the risk of making incorrect or delayed decisions in the absence of strong data governance and preprocessing procedures.

6.2. Opportunities

Advanced predictive and prescriptive analytics in rescheduling are made possible by the strong real-time data management capabilities made possible by DTs. AI models may anticipate possible bottlenecks, equipment problems, or material shortages before they happen by continuously gathering and evaluating data. It is feasible to proactively allocate resources and minimize operational inefficiency in last-mile delivery scenarios by forecasting delivery demand using models like LSTM, ARIMA, and neural networks, and combining them with optimization frameworks like the bin packing problem [54]. By continuously learning from system feedback, schedulers based on RL may adjust to changing production conditions. A multi-agent double DQN architecture for online hybrid flow shop scheduling is used by Wang et al. [43] for responsive decision-making in the face of uncertainty. Within the DT framework, there is a chance to create sophisticated anomaly detection systems that can quickly identify minute departures from scheduled activities or unforeseen occurrences, prompting either human alerts or AI-driven reactions.

By learning from operational and historical data, advanced AI models can improve scheduling and resource allocation. This is illustrated by Fadda et al. [51] using an ML optimization framework for last-mile delivery in which tactical fleet planning is guided by demand projections. In a similar vein, Yildiz [67] demonstrates how complicated combinatorial problems like the knapsack can be solved by RL models using transformer structures and attention, allowing for adaptive decision-making. Although these methods provide the foundation for intelligent scheduling, more investigation is required to incorporate them into DT environments with strong data governance and lifecycle management.

7. Integration and Interoperability

7.1. Advancements

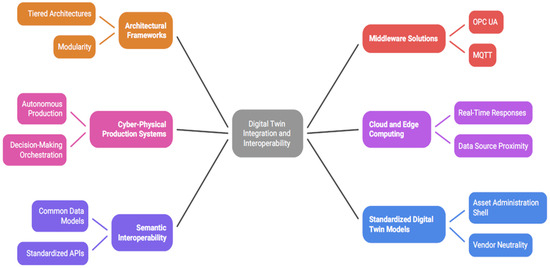

Seamless communication between several systems includes SCADA, ERP, and MES. The DT platforms and AI algorithms are essential for the effective implementation of DT-AI for production rescheduling. The development of architectural frameworks that support this integration has advanced significantly [4,16,24,25,26,35]. These studies show advancement in developing modular designs that enhance adaptability and generalizability [34], scalable reinforcement learning scheduling frameworks [23,24,25], and layered DT-AI architectures with an emphasis on interoperability between ERP and sensor systems [4,16]. In order to handle the intricacy of data flow and decision-making while guaranteeing modularity, scalability, and maintainability, these frameworks frequently suggest tiered architectures (such as physical, virtual, connection, and service layers) [4]. To close the gap between heterogeneous systems and facilitate reliable data transmission across many platforms and suppliers, research has looked into the usage of middleware solutions, standardized communication protocols (such as OPC UA, MQTT, and ROS), and API-driven interfaces [32,35]. Concurrently, DRL techniques have demonstrated significant promise for real-time decision-making and dynamic scheduling in adaptable and reconfigurable manufacturing contexts [25,41], making them useful parts of DT-AI integrated systems. An excellent illustration of attaining more integration between the digital and physical realms for autonomous production is the creation of CPPS with DT capabilities, in which the DT serves as the primary information center and orchestrator of real-time decision-making [24]. Heterogeneous systems and data sources must be seamlessly integrated for DTs to be successfully deployed for production scheduling. Simultaneously, distributed scheduling techniques, including multi-agent systems, have been investigated to improve coordination and responsiveness in flexible manufacturing environments [69], providing complementary means to decentralize control and increase adaptability. The smooth integration of several systems and data sources is essential to the successful deployment of a DT for production scheduling. This calls for DT to interact with a wide variety of platforms in a contemporary manufacturing setting, including ERP, MES, and numerous IoT sensors. It is difficult to make these different systems understand what is mentioned as an identical terminology [70]. Improvements in semantic interoperability and data-driven integration are essential to addressing this. Modern DT frameworks are shifting toward flexible, data-centric designs in place of strict, one-to-one data relationships. This entails utilizing standardized APIs and common data models to enable information sharing between systems without the need for an intricate web of unique interfaces. The necessity for universal data models to enable integration is emphasized in Tao et al. [68]. Lee et al. [71] proposed a mathematical model of Bernoulli production lines to evaluate yield and its properties with respect to time constraints, buffer capacity, and machine reliability.

The usage of integration platforms and middleware is another significant development. By controlling data flows and system translations, these solutions serve as a central center. The DT can pull and push data in real-time from any connected source because of its ability to support a wide range of protocols (such as MQTT and OPC UA) and data formats. This offers a single point of control for the whole data environment and simplifies the management of numerous connections. Additionally, the need for interoperability has increased due to the growth of CPS. DT needs to be capable of both monitoring and operating physical equipment. This necessitates a low-latency, secure communication link that guarantees precise and timely execution of directives transmitted from the DT. He et al. [72] demonstrated the integration of real-time scheduling with physical systems and emphasized the significance of synchronized communication and system responsiveness in enabling a flexible and effective production environment. Real-time sensor fusion, a technique that combines data from multiple sensor types to create a more comprehensive and reliable depiction of the system’s condition, is one noteworthy advancement. This method creates a more accurate foundation for scheduling and operational decisions while avoiding the limitations of individual sensors. Scholars such as Huang et al. [73] have examined the use of hybrid optimization algorithms for the flexible job-shop scheduling problem, specifically the transportation constraint, which are highly data-dependent and can be enhanced by advanced data management and fusion techniques [73]. Figure 6 presents DT integration and interoperability of various hardware and software frameworks. The essential elements for integrating a DT across production systems are outlined in Figure 6. It emphasized middleware protocols, architectural frameworks, semantic interoperability, and standardized models such as the asset administration shell. These components facilitate real-time orchestration across CPS and enable vendor-neutral, plug-and-play DT deployment.

Figure 6.

DT Integration and Interoperability.

Overcoming the problem of semantic interoperability is essential to the advancement of DT applications. In order to adopt flexible, data-centric architectures, current frameworks must transcend inflexible, point-to-point data links. To allow systems to exchange data and share a common understanding of their context and meaning, standardized protocols, APIs, and common data models must be established. Scaling DTs from isolated instances to a complex, linked system of DT (SoDT), a concept described by David et al. [70] that essentially depends on interoperability for its success, requires this move towards an ontology-driven approach. Physical machinery must be under DT’s control in addition to being monitored to guarantee that commands transmitted from the DT are carried out precisely and promptly. Flexible manufacturing systems, synchronous scheduling and execution between the machines, and automated guided vehicles require a secure, low-latency communication link. According to research by He et al. [72], creating a responsive and agile production environment requires integrated scheduling frameworks that are backed by dependable communication across physical and digital layers. One significant trend is the growing use of standardized DT models, like Asset Administration Shell (AAS), which offers a common, vendor-neutral method of describing and interacting with the digital version of a physical asset.

Diverse vendor solutions and proprietary protocols that impede smooth communication between DT, AI, and legacy systems are the root cause of integration issues. High integration costs, protocol incompatibility, and a lack of defined AZPIs are examples of technical impediments. Scalability across organizations is limited by the current DT-AI systems, which frequently stay siloed. According to Gao et al. [37] and Tao et al. [14], most industrial installations rely on ad hoc interfaces rather than unified standards, making interoperability a crucial obstacle.

7.2. Opportunities

The development of standardized, plug-and-play DT-AI modules that are simple to deploy, configure, and scale across many production environments and industries is made possible by the continuous effort in integration and interoperability. This would speed up adoption, drastically cut down on implementation barriers, and save manufacturers’ development expenses. A more cohesive ecosystem can be fostered by creating open-source DT-AI platforms, reference architectures, and standard data models (such as ontologies and semantic models) that encourage cooperation and information exchange between the industry and research community [25,74]. More complex, cross-domain rescheduling solutions can reason for complex relationships between various manufacturing entities, even across different domains or companies. Wang and Zhu [74] show how FJSSP with sequence-dependent setup times and task lag limits may be successfully handled by hybrid genetic algorithms that combine global search with local refinement. Their research demonstrates how integrating evolutionary and tabu search techniques improves robustness and adaptability, laying the groundwork for DT-AI systems to handle challenging scheduling situations in diverse production settings. Moving toward a comprehensive, networked manufacturing ecosystem demands a dynamic scheduling technique that can adjust to new job arrivals and real-time disruptions. By applying DRL to flexible job shop scheduling with new work insertion, Luo [41] showed how a production system can adapt swiftly to uncertainty while maintaining efficiency. These methods emphasize how crucial resilience and adaptability are to DT-AI for production scheduling. The remaining shortcomings found in this analysis should be the main focus of development efforts in DT-AI for production scheduling. The creation of a completely autonomous and decentralized framework presents one important potential. Although multi-agent systems offer a foundation, federated learning is necessary for a genuinely strong system to enable robots to jointly enhance their scheduling rules without exchanging private or proprietary information, protecting confidentiality and privacy. The incorporation of sophisticated generative AI models is another crucial area. Although current DTs are effective at simulating, by incorporating generative models, the system may be able to independently suggest new production scenarios, resource configurations, or even product designs, going beyond simple optimization to actual creativity. This might result in a system that finds new ways to be efficient in addition to finding solutions to issues.

8. Adaptability and Generalizability

8.1. Advancements

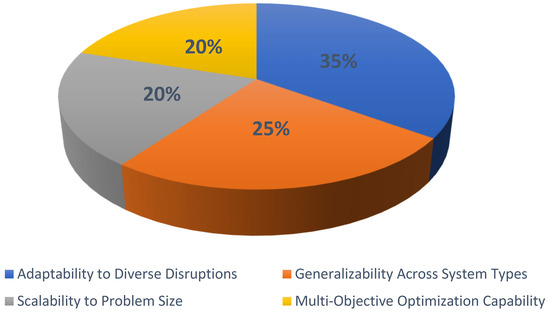

One of the biggest challenges in dynamic scheduling is ensuring that AI models can adapt to new, unforeseen events and generalize their learnt policies beyond particular training data. RL agents can create rules that are inherently adaptive to shifting shop floor conditions and are able to handle unforeseen events after being taught through trial and error in a simulated or actual environment [17,37,75]. Surveys on explainable AI have highlighted the significance of transparency in such adaptive models [19]. Complementary research demonstrates how incorporating a DT framework into manufacturing systems [26,27,29] and combining AI with simulation [28] can improve interoperability and resilience, laying the groundwork for reliable DT-AI scheduling solutions in challenging production environments. In terms of flexible job scheduling, RL has demonstrated exceptional potential in this field. Sophisticated design, including an attention mechanism [50,58] and transformer-style and Graph Neural Network (GNN) architectures [42,56], which are ideally adapted to capture relational structures and long-range interdependence inherent in complex job shops, are incorporated into recent breakthroughs in DRL. These methods describe complex operations of machine links to produce scheduling policies that are generalized across many contexts. The importance of simulation based on frameworks [57] in enhancing robustness and adaptability is highlighted by complementary studies. Multi-agent and multi-action RL frameworks have been investigated to further improve system resilience and decentralized decision making, allowing agents to coordinate and adjust to local perturbations in dynamic contexts [50,56,64,76]. These models’ power to generalize to real-world unpredictability and novel scenarios is improved by their ability to learn from a variety of training data, such as simulated disturbances and different system configurations. The pie chart in Figure 7 emphasizes many elements that contribute to the adaptability and generalizability of production scheduling. Figure 7 illustrates how a number of interconnected factors affect both generalizability and adaptability. This includes algorithm resilience, illustrating how effectively the system handles disturbances and variability; system scalability, which impacts performance across various production contexts; and data heterogeneity, which hampers model training and transferability. These factors are essential for creating robust DT-AI-based scheduling systems that can function well in a variety of scenarios [77].

Figure 7.

Elements that contribute to adaptability and generalizability of production scheduling.

AI models are frequently trained on small datasets connected to particular store settings, which is the main reason for their restricted adaptability. Models perform worse when production settings frequently change. Inadequate meta-learning techniques, a lack of transfer learning mechanisms, and overfitting RL policies are examples of technical impediments. Han and Yang [50] showed that DRL can maximize flexible job shop scheduling but may struggle to generalize across multiple situations. In a similar vein, Li et al. [44] noted that as new disruption kinds appear, anomaly detection algorithms need to be retrained.

8.2. Opportunities

The quest for generalizability and adaptation creates the possibility of extremely robust and adaptable production systems that may prosper even in extremely unstable and unpredictable conditions. Reinforcement-learning-enhanced metaheuristics can learn and make policies in an adaptive manner in dynamic, human-centric shopfloors. Additionally, through transfer learning, policies trained for one disruption or context can be quickly repurposed to similar settings with minimal retraining, reducing deployment time and cost [55]. Furthermore, hybrid ant colony optimization frameworks, which jointly optimize machine assignment and operation sequencing, can demonstrate promising performances based on established benchmarks [72].

DT-AI frameworks can handle new interruptions or product mixes with less manual reprogramming because they can adjust to changing shopfloor situations. In a flexible job shop, DT-AI frameworks promote quick adaptation and operational resilience [8,29]. By guaranteeing consistent fixture flows and enhancing responsiveness in dynamic situations, integrated DT-AI simulation techniques significantly improve decision-making [28]. The viability of integrating AI models into industrial environments is further demonstrated by practical investigation on micro-production units, which show how DT objects may be produced using common engineering software [26]. Additionally, by studying meta-learning for production scheduling, AI models may be able to “learn how to learn” new rescheduling techniques faster, so that they become flexible and able to continuously improve themselves in dynamic settings.

Because AI models can generalize, they can also handle new kinds of disruptions or product mixes that they have not encountered during training. This results in previously unheard-of levels of operational resilience and less re-programming for each new scenario [8,26,28,29]. A cycle of constant optimization and adaptation is also fostered by AI that opens the door for creating “learning factories,” where AI models continuously improve their scheduling strategies in response to fresh operational data and user feedback.

Table 5 presents connections between potential technologies and research gaps in DT-AI-based production scheduling. The lack of transparency in adaptive scheduling can be addressed by explainable AI (XAI). Federated learning immediately solves the gap of inadequate generalization across various contexts. Blockchain may be able to bridge the gap of unsafe and fragmented data sharing in real-time data management for integration and interoperability. In order to solve large-scale, dynamic scheduling problems, quantum computing may be able to help overcome computational bottlenecks. Finally, the human DT technology may be able to bridge the gaps of insufficient human-in-the-loop monitoring and trust. These potential technologies are conceptual and may help with unmet needs of production scheduling as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Linking potential technologies to gaps in DT-AI-based production scheduling.

9. Summary

The past, present, and future of implementing DT and AI technologies in dynamic production scheduling are thoroughly assessed in this literature review. There are many developments in related areas, but production rescheduling based on DT-AI-driven frameworks is examined in depth to understand the current state of the field and future trends. Especially, this assessment aims to pinpoint the key areas of unmet research and technology that are preventing DTs and AI from reaching their full potential in manufacturing. For instance, cutting-edge concepts like explainable AI, federated learning, blockchain, quantum computing, and human DTs that have not yet been incorporated into production rescheduling need more research [78,79,80,81].

Production scheduling plays an essential role in shaping manufacturing lead times, cost reduction, and resource allocation. In light of growing system complexity like unforeseen machine issues, unexpected or urgent workorders, material shortages, etc., conventional static scheduling techniques often fail to meet the demands of highly dynamic markets. The integration of AI and DTs into production scheduling shows promise to revolutionize manufacturing by providing cutting-edge capabilities like real-time monitoring, modeling, simulation, prediction, optimization and so on. Articles chosen for this literature review were mostly published within the last eight years. This study emphasizes five technical challenges that are consistently considered in the literature, which encompass Dynamic and Unforeseen Disruptions, High System Complexity, Real-Time Data Management, Integration and Interoperability, and Adaptability and Generalizability. This review not only identifies these technical challenges but also provides tailored syntheses of progress and future directions. Industrial practices and implementation issues are also covered. This evaluation functions as both an industrial reference and a scholarly roadmap by fusing technical depths with practical insights. It provides researchers and practitioners with practical guidance in the areas of DT-AI-based production scheduling.

New research directions may focus on edge-enabled rescheduling loops in the near-term future (one to two years) to reduce decision-making latency. To boost human operator trust, explainable AI overlays ought to be studied for production scheduling. To integrate MES, ERP, and SCADA, data governance frameworks must be created. Hierarchical DT orchestration may be put into place in the medium-term future (two to three years). Scalability and coordination between machines, stores, and plants will be enhanced by this. To cut down on retraining time, meta-learning and transfer learning should be used. To balance robustness, energy, and throughput, multi-objective optimization techniques should be developed.

Federated learning should be investigated for cross-enterprise scheduling in the long-term future (three to five years). This will make it possible for plants to collaborate while maintaining privacy. Scheduling choices should be secured using blockchain-based provenance. The development of human-DT integration must consider ergonomic limitations and operator skills. Maintaining DT fidelity by automated calibration is one of the strategic opportunities. AI regulations need to be adaptable to changes in distribution. It is important to make sure that industrial safety regulations are followed. Future research should be in line with quantifiable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), such as efficiency, tardiness, latency, etc., which may facilitate the transition of DT-AI-based production scheduling from prototypes to reliable industrial practice.

It is essential to make sure AI models can generalize policies outside of training data and address novel situations. Advanced DRL architectures, such as GNNs, Attention, and Transformers, allow intelligent agents to learn and make adaptive, generalizable policies. Possibilities include “meta-learning” for quicker strategy acquisition and “transfer learning” for quicker adaptation to new environments and managing new disturbances, all of which help create intelligent factories. The assessment concludes that although DTs and AI present previously unheard-of opportunities for dynamic production rescheduling, there is still more research to conduct in order to mature these advanced manufacturing concepts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., K.K. and E.B.; methodology, P.S.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, K.K. and E.B.; visualization, P.S. and E.B.; supervision, K.K. and E.B.; project administration, K.K. and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to the Department of Industrial Systems and Manufacturing Engineering, Wichita State University, for the administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| BDA | Big Data Analytics |

| CPS | Cyber-Physical Systems |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| MES | Manufacturing Execution System |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| FJSSP | Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| BOM | Bill of Materials |

| OPC UA | Open Platform Communication Unified Architecture |

References

- Pinedo, M.; Hadavi, K. Scheduling: Theory, Algorithms and Systems Development. In Operations Research Proceedings 1991; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Priore, P.; Fuente, D.; Gomez, A.; Puente, J. A review of machine learning in dynamic scheduling of flexible manufacturing systems. AI EDAM 2001, 15, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouelhadj, D.; Petrovic, S. A survey of dynamic scheduling in manufacturing systems. J. Sched. 2009, 12, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, P.; Jinsong, B. Digital Twin-based manufacturing system: A survey based on a novel reference model. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 2517–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besigomwe, K. Closed-Loop Manufacturing with AI-Enabled Digital Twin Systems. Cogniz. J. Multidiscip. Studies 2025, 5, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Viquez, D.; Zamora-Hernandez, M.; Fernandez-Vega, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.; Azorin-Lopez, J. A Comprehensive Review of AI-Based Digital Twin Applications in Manufacturing: Integration Across Operator, Product, and Process Dimensions. Electronics 2025, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Peng, C.; Lou, P.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, J.; Yan, J. Digital-Twin-Based Job Shop Scheduling Toward Smart Manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 6425–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, K.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, J. Digital Twin-Driven Adaptive Scheduling for Flexible Job Shops. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, A.H. Digital Twins for Improving Proactive Maintenance Management. Eng. Sci. 2024, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Flanigan, K.A.; Bergés, M. State-of-the-art review: The use of digital twins to support artificial intelligence-guided predictive maintenance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.13117. [Google Scholar]

- Holguin Jimenez, S.; Trabelsi, W.; Sauvey, C. Multi-Objective Production Rescheduling: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Carabelli, S.; Fadda, E.; Manerba, D.; Tadei, R.; Terzo, O. Machine learning and optimization for production rescheduling in Industry 4.0. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 2445–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, M.; Singh, S. A review of metaheuristic scheduling techniques in cloud computing. Egypt. Inform. J. 2015, 16, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L. Cyber-physical Production Systems: Roots, Expectations and R&D Challenges. Procedia CIRP 2014, 17, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Chan, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, F. Defining a Digital Twin-based Cyber-Physical Production System for Autonomous Manufacturing in Smart Shop Floors. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 6315–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Pan, W.; Huang, G.Q. Digital twin-enabled real-time synchronization for planning, scheduling, and execution in precast on-site assembly. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bakhtiyar, S.; Park, J. Schedulenet: Learn to solve multi-agent scheduling problems with reinforcement learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.03051. [Google Scholar]

- Zemskov, A.D.; Fu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Karkaria, V.; Tsai, Y.-K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Gao, R.; Cao, J. Security and privacy of digital twins for advanced manufacturing: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.13939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Mangalaraj, G. Big Data Analytics in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Directions. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, M.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Song, W.; Lu, Z.; Li, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Dynamic Scheduling of Random Arrival Tasks in Cloud Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Universal Village (UV), Boston, MA, USA, 21–23 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yan, J.; Guo, S. Real-time workshop digital twin scheduling platform for discrete manufacturing. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1884, 012006. [Google Scholar]