Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed adjunctive folding-wing range extender enables the host small multirotor UAV to achieve a 20% reduction in total power consumption and a 25% improvement in endurance/range at a 20 m/s cruise speed.

- With the wings deployed, the host small multirotor UAV exhibits a 52% higher equivalent lift-to-drag ratio and a 34% lower specific power, indicating significantly enhanced aerodynamic efficiency.

What is the implication of the main findings?

- This device provides a modular solution to substantially extend the mission capabilities of the host small multirotor UAV, effectively addressing its endurance limitations while preserving its inherent portability and high maneuverability.

- The design allows the host small multirotor UAV to rapidly switch between multirotor and fixed-wing modes during flight, greatly improving its adaptability and operational flexibility in complex mission scenarios.

Abstract

Small multi-rotor UAVs face endurance limitations during long-range missions due to high rotor energy consumption and limited battery capacity. This paper proposes a folding-wing range extender integrating a sliding-rotating two-degree-of-freedom folding wing—which, when deployed, quadruples the fuselage length yet folds within its profile—and a tail-thrust propeller. The device can be rapidly installed on host small multi-rotor UAVs. During cruise, it utilizes wing unloading and incoming horizontal airflow to reduce rotor power consumption, significantly extending range while minimally impacting portability, operational convenience, and maneuverability. To evaluate its performance, a 1-kg-class quadrotor test platform and matching folding-wing extender were developed. An energy consumption model was established using Blade Element Momentum Theory, followed by simulation analysis of three flight conditions. Results show that after installation, the required rotor power decreases substantially with increasing speed, while total system power growth slows noticeably. Although the added weight and drag increase low-speed power consumption, net range extension emerges near 15 m/s and intensifies with speed. Subsequent parametric sensitivity analysis and mission profile analysis indicate that weight reduction and aerodynamic optimization can effectively enhance the device’s performance. Furthermore, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis confirms the effectiveness of the dihedral wing design in mitigating mutual interference between the rotor and the wing. Flight tests covering five conditions validated the extender’s effectiveness, demonstrating at 20 m/s cruise: 20% reduction in total power, 25% improvement in endurance/range, 34% lower specific power, and 52% higher equivalent lift-to-drag ratio compared to the baseline UAV.

1. Introduction

Small multirotor UAVs have gained extensive and in-depth application across numerous fields, including power line inspection, emergency response, logistics transportation, mapping, and aerial photography [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], owing to their compact size, high maneuverability, and the foldable airframe inherent to some configurations [9,10,11,12]. These prominent advantages enable them to adapt to complex and variable operational environments, thereby enhancing the efficiency of various missions. However, constrained by the limited energy density of batteries and the low aerodynamic efficiency of rotors, the endurance of small multirotor UAVs remains generally poor, leading to unsatisfactory performance in long-range missions such as power line inspection [13]. In practical long-range missions, multiple flights or additional devices are often required to complete the task in a relay manner [14], which significantly reduces operational efficiency and substantially increases costs. For instance, the DJI M4T achieves a flight endurance of up to 40 minutes and a range of less than 35 km under no-load, ideal conditions. However, when operating in complex environments with payload, its range and endurance experience a further reduction [15].

Compared to multirotor UAVs, fixed-wing aircraft exhibit significantly higher aerodynamic efficiency during the cruise phase. Consequently, to address the challenges encountered in long-range missions, researchers have developed various configurations of vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) fixed-wing UAVs by integrating the respective advantages of both platforms [16]. These include configurations equipped with dual propulsion systems [17,18], those utilizing tilting propulsion units or wing for flight mode transition [19,20], and tail-sitter configurations [21], among others. It is important to note that the aforementioned hybrid configurations primarily target medium to large-scale aircraft. For small-scale UAVs, research efforts have also been undertaken in recent years. Kun Xiao et al. integrated a lift-generating wing mounted at a specific angle onto a small quadrotor, achieving approximately 50% power savings at a certain forward flight speed [22]. However, the performance of this fixed-angle wing is highly susceptible to variations in flight attitude and significantly compromises other flight capabilities, such as roll maneuverability. Michal et al. designed the arms of a small quadrotor into fixed wings and incorporated a tail-thrust propeller for efficient cruise [23,24]. However, this design suffers from significant mutual aerodynamic interference due to the insufficient distance between the rotors and the wings. Furthermore, the non-collapsible fixed-wing structure severely compromises the vehicle’s maneuverability. In addition, in contrast to the compact size small multirotor UAVs possess in folded state and their rapid-deployment capability, most of the aforementioned winged aircraft lack direct foldability. Even when disassembled, they still require considerable storage space. Moreover, the assembly process involves multiple steps, such as connecting the wings to the fuselage and calibrating the control surfaces, which imposes practical limitations on their real-world application.

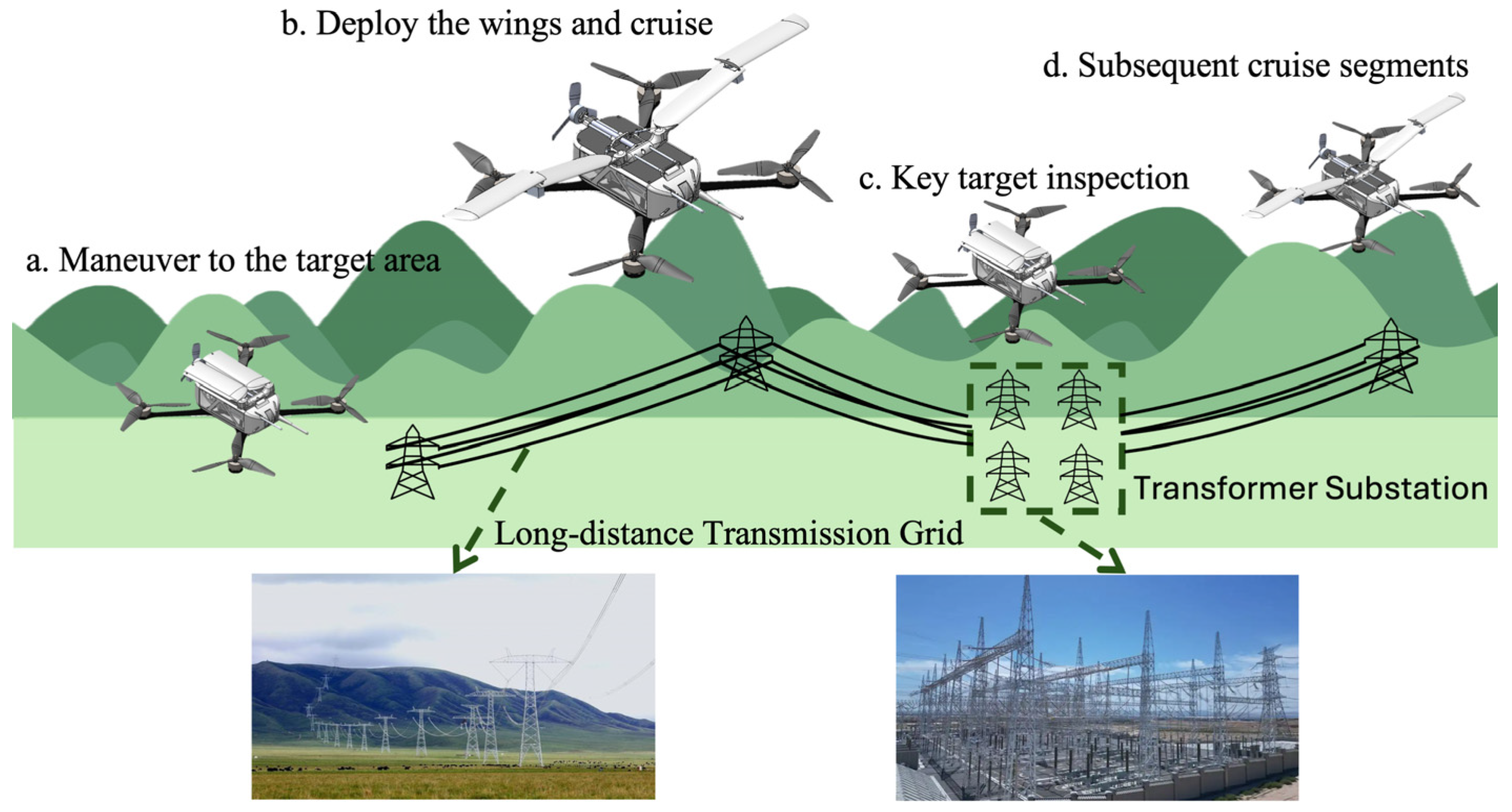

To this end, this paper proposes a adjunctive Folding-Wing Range Extender (FWRE) for small multirotor UAVs. During long-range missions, the device in its folded state can be rapidly installed onto the host UAV via connection methods such as bolts, quick-release buckles, or straps. Prior to entering the cruise phase, the wings deploy while the UAV is in a hover. Following this, the integrated tail-thrust propeller engages to drive it forward horizontally forward. This configuration offers dual aerodynamic benefits: first, it subjects the rotors to oncoming horizontal airflow, thereby enhancing their lift-generating capability [25,26]; second, the deployed wings provide lift support, offloading the rotors which then primarily function for attitude control. Consequently, the overall power consumption is significantly reduced. This approach provides a novel solution to the endurance shortcoming of small multirotor UAVs, while maintaining their inherent portability and operational flexibility.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed description of the structural design of the adjunctive range extender and outlines the operational modes for small multirotor UAVs when integrated with this device during long-range missions. Section 3 introduces the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) numerical methods employed in this study. Section 4 establishes an energy consumption model for the vehicle based on the Blade Element Momentum Theory, analyzing the range-extension mechanism resulting from the combined effects of wing lift offloading and oncoming horizontal airflow. Section 5 conducts simulation studies on a 1-kg-class small quadrotor and its FWRE counterpart across three typical flight conditions, analyzing power consumption trends at different forward speeds; parameter influence analyses regarding extender mass, lift loss coefficient, and overall drag coefficient are also performed, along with mission profile analysis under given scenarios. Section 6 presents the results and analysis of the CFD simulations, investigating the interference mechanisms between the wing and rotors as well as between the rotors and the rear-mounted propeller. Section 7 covers the experimental work. A 1-kg-class small quadrotor test platform and its range extender counterpart are developed. Their performance is evaluated through flight tests under five conditions, systematically assessing endurance, range, and energy efficiency to validate the extender’s effectiveness.

2. Design and Operational Modes

2.1. Folding-Wing Range Extender Design

Targeting small multirotor UAVs. A Folding-Wing Range Extender is designed as a functional accessory. Its design adheres to key principles: in the folded state, the wing assembly must achieve high compactness, positioned proximate to the vehicle’s center of gravity while minimizing the addition to the original fuselage’s projected area. This configuration effectively mitigates the resultant increases in aerodynamic drag and moment of inertia, thereby minimizing adverse effects on the inherent maneuverability. Simultaneously, when deployed for lift generation, the longitudinal position of the wing must be located as close as possible to the center of gravity to minimize the additional moment disturbance imposed on the flight control system. However, the requirements for controlling the projected area increment and maintaining proximity to the center of gravity constrain the geometric dimensions of the foldable wing, thereby limiting its lift-generating capability at typical small multirotor UAV cruising speeds. This paper innovatively proposes a sliding-rotating, two-degree-of-freedom two-segment folding wing scheme. With a chord length equal to half the fuselage width and a wingspan reaching four times the fuselage length when deployed, this design substantially increases the folded wing area and aspect ratio, thereby significantly enhancing wing performance.

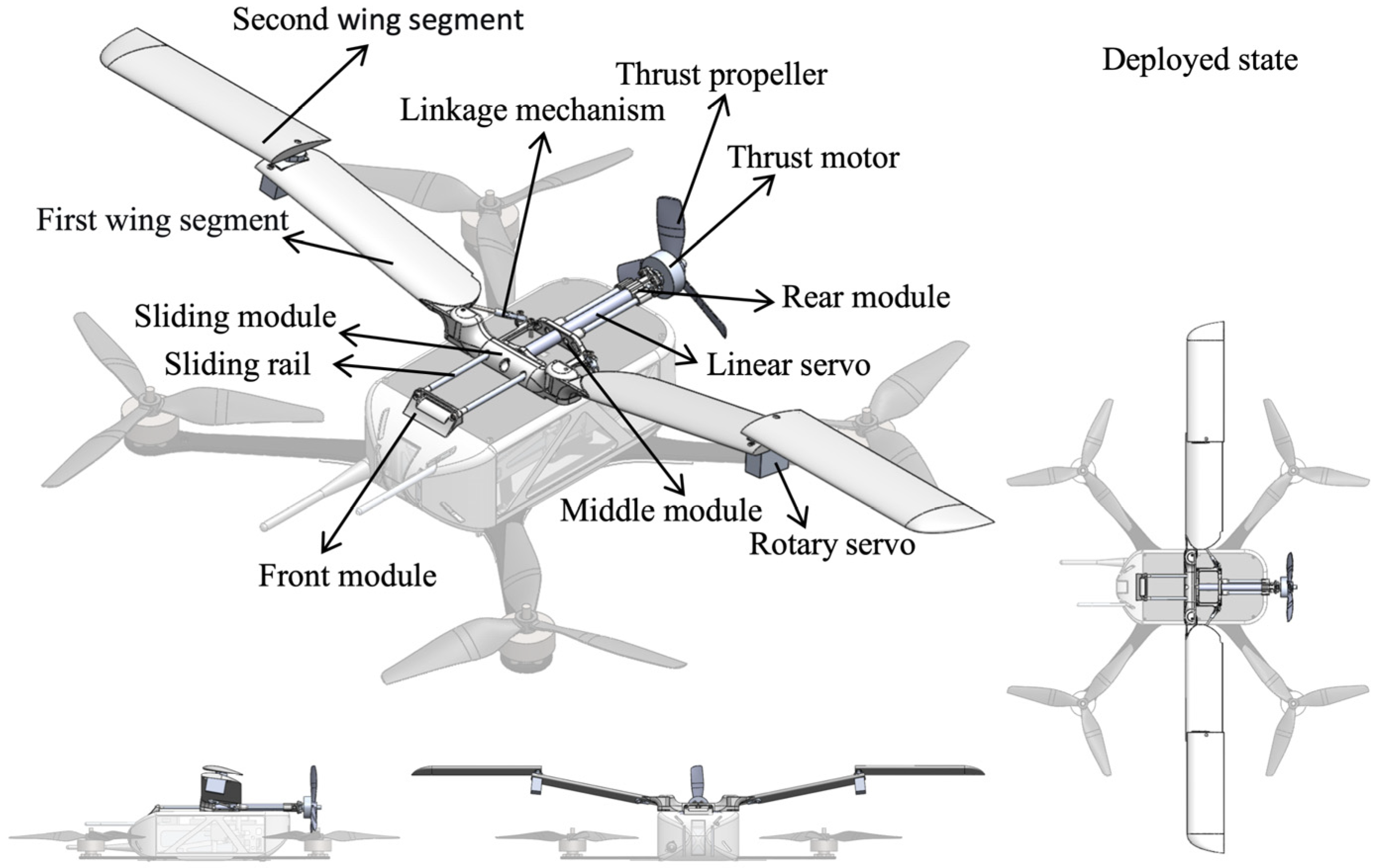

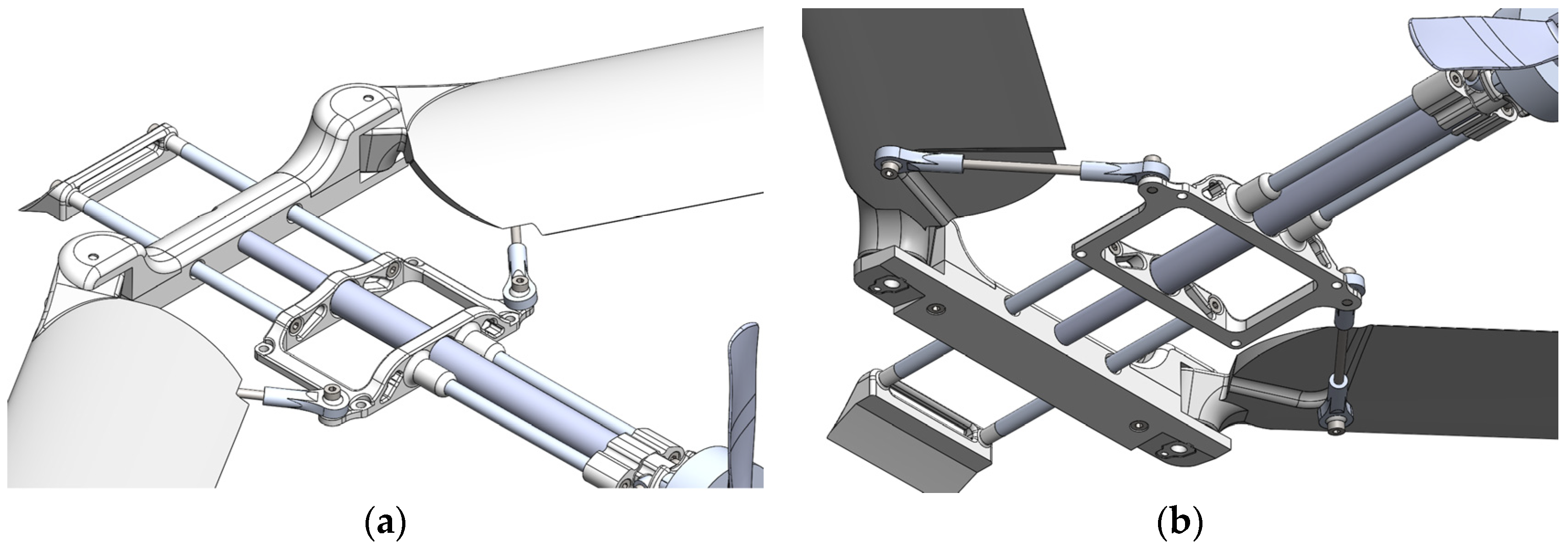

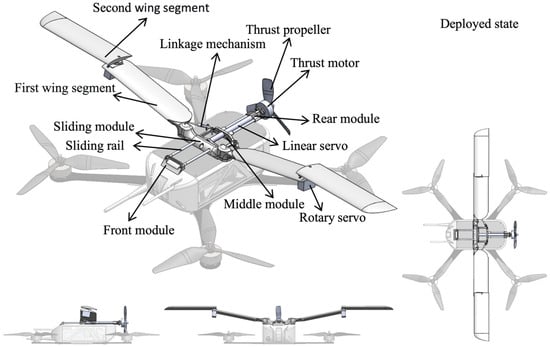

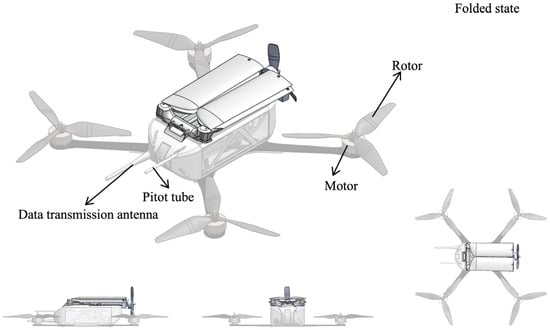

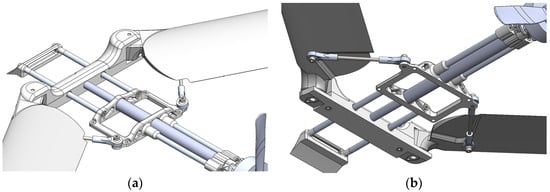

Based on this folding wing concept, the specific Folding-Wing Range Extender and the small quadrotor UAV integrated with it are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively, with detailed views of the extender provided in Figure 3. The core components of the range extender comprise a linear servo, a linkage mechanism, a rotary servo, key structural components (front module, sliding module, middle module, and rear module), and a sliding rail. In the deployed state, the two-segment wing provides the primary lift for rotor offloading. The first wing segment features a dihedral angle, which elevates its own surface as well as that of the subsequent second straight wing segment away from the rotor plane. This configuration thereby reduces aerodynamic interference between the fixed wing and the rotor flow field, preventing degradation in the efficiency of both systems. The linear servo actuates the sliding module, driving it to translate along the sliding rail fixed between the front and middle modules. This motion is transmitted via the linkage mechanism to fold or deploy the first wing segment. A rotary servo, mounted at the trailing edge of the first wing segment, drives the rotation of the subsequent second straight wing segment, enabling its rotational folding and deployment. To accommodate different host small multirotor UAVs, the corresponding range extender is rapidly connected to the main body of the host vehicle via the middle module using bolts, quick-release buckles, or straps. The rear module serves to house the tail-thrust motor and propeller, providing the necessary thrust for the UAV during the cruise phase.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the Folding-Wing Range Extender in the deployed state.

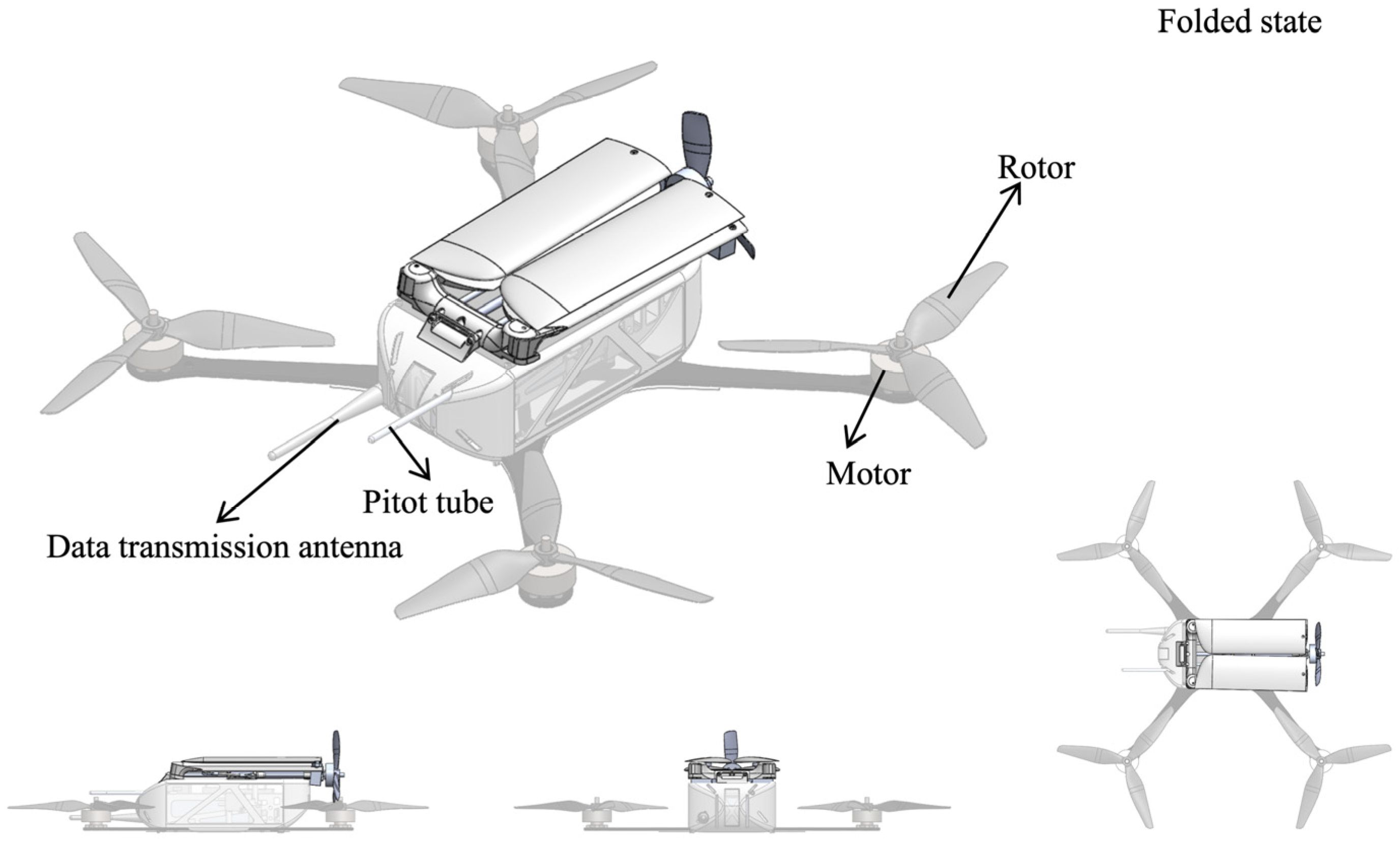

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the Folding-Wing Range Extender in the Folded state.

Figure 3.

Detailed schematic diagram of the Folding-Wing Range Extender: (a) Top view; (b) Bottom view.

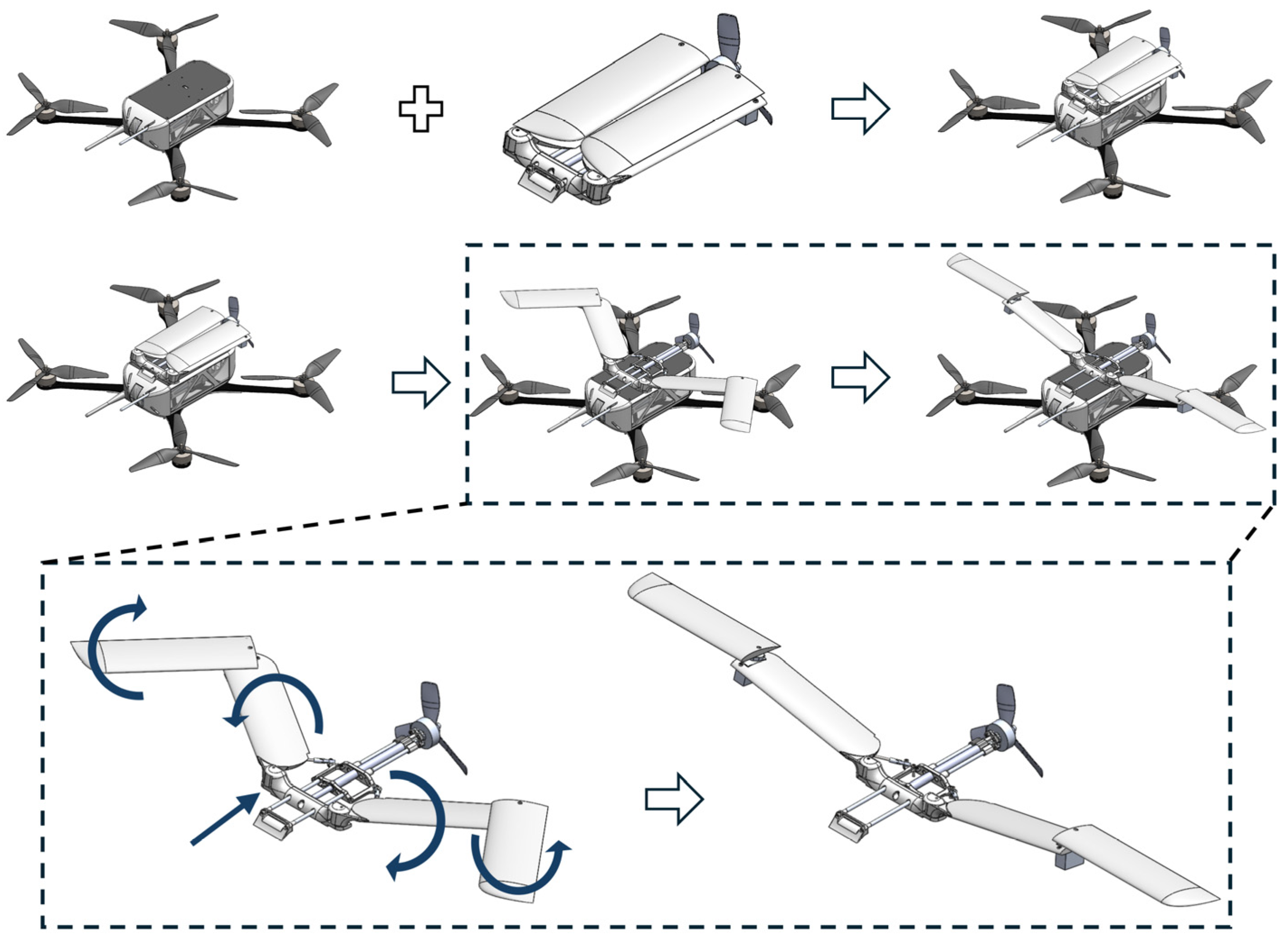

The assembly process of the FWRE with the host small multirotor UAV and its deployment process are illustrated in Figure 4. The first wing segment employs a coupled sliding-rotating folding mechanism, with its rotation shaft fixed to a sliding module that translates along the sliding rail. When the sliding module is positioned at the foremost end of the sliding rail, the wing assembly attains a compact folded state, where both the projected area and the moment of inertia increment are minimized. The deployment process is initiated by the linear servo, which drives the sliding module rearward along the sliding rail to a central region of the fuselage, proximate to the center of gravity. Concurrently, the linkage mechanism converts this sliding displacement into an outward deployment motion of the wing. This specific positioning helps mitigate adverse interference of the wing’s lift and aerodynamic moments on vehicle control. The second wing segment, with a wingspan comparable to the first, is connected via the rotary servo to the trailing edge of the first segment. Upon full deployment of the first wing segment, the rotary servo drives the second segment to undergo outward rotational deployment, thereby further extending the total wingspan.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the Folding-Wing Range Extender integrated with a small quadrotor UAV and its deployment process.

2.2. Operational Modes

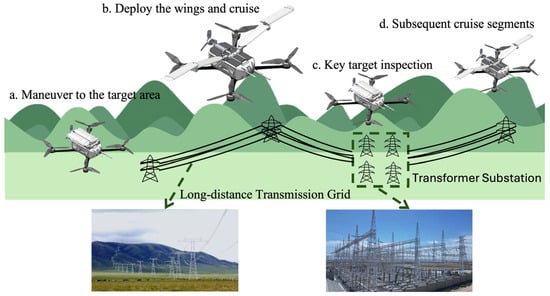

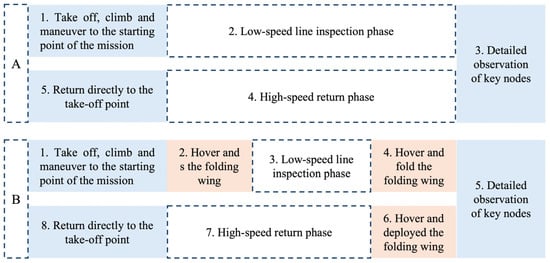

As can be readily inferred, the proposed FWRE achieves flexible and efficient integration with the host small multirotor UAV and enables seamless mode switching, thereby significantly enhancing the mission adaptability of the UAV. Correspondence between typical operational modes and mission profiles for the small multirotor UAV with the installed FWRE is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Correspondence between typical operational modes and mission profiles for the small multirotor UAV with the installed Folding-Wing Range Extender.

During the preparation phase, to execute composite missions involving long-range cruise, the FWRE can be installed onto the small multirotor UAV via quick-release mechanisms (bolts, quick-release buckles or straps). This results in a compact, folded integrated system (Figure 5a), which facilitates easy transportation and field deployment.

During the take-off and landing phase, the integrated system retains the vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capability and high maneuverability inherent in the host multirotor UAV. This enables reliable operations in complex environments and allows the system to proceed to the designated mission airspace.

Prior to entering the cruise phase, the folding wings deploy while in a hover and then the tail-thrust motor provides forward propulsion, driving the UAV to maintain level-attitude cruise (Figure 5b). In this configuration, the fixed wings generate lift to support the majority of the vehicle’s weight, significantly reducing the load on the rotors. The rotors now provide only a small portion of the total lift and primarily focus on attitude control. Simultaneously, the oncoming horizontal airflow enhances the aerodynamic efficiency of the rotors, leading to a further reduction in power consumption. In this operational state, both the rotors and the fixed wing operate within their respective high-efficiency regimes, resulting in substantially lower cruise energy consumption and corresponding increases in range and endurance.

When the mission requires detailed observation of critical infrastructure targets (e.g., transmission towers, bridge structural nodes), the wings rapidly fold, and the system reverts to multirotor mode (Figure 5c). In this mode, the system regains stable hovering and high precision positioning capabilities, making it suitable for precision inspection and data acquisition tasks. Upon task completion, the wings can be redeployed to restore the range-extension mode (Figure 5d) for subsequent cruise segments.

In summary, through rapid assembly/disassembly and flexible multi-mode switching, the proposed range extender synergistically combines the advantages of both multirotor and fixed-wing aircraft. This integration effectively expands the adaptability of small multirotor UAVs in complex mission scenarios.

3. Numerical Method

This study employs the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) method to mainly analyze the following three types of issues: the performance changes of the rotor under horizontal incoming flow, the influence of the dihedral angle of the wing on the aerodynamic characteristics of the wing and the rotor, and the aerodynamic interference between the rotor and the tail propeller. This section will provide a brief description of the CFD method adopted and the specific settings in ANSYS Fluent (2024 R2).

All CFD calculations in this study were conducted under three-dimensional, steady-state conditions. The air medium was modeled as an ideal gas. The rotational effects of the rotor and propeller were simulated using the steady-state Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) approach. The governing equations employed were the three-dimensional, steady-state, Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations for compressible flow. The continuity equation is expressed as:

where is the density and are the velocity components. The momentum conservation equation is:

where is the static pressure, are the components of the viscous stress tensor, and represents the component of the Coriolis and centrifugal forces introduced by the MRF method. The complete set of governing equations also includes the energy conservation equation and the ideal gas equation of state. The turbulence was modeled using the model. Spatial discretization was performed using a second-order upwind scheme to ensure computational accuracy.

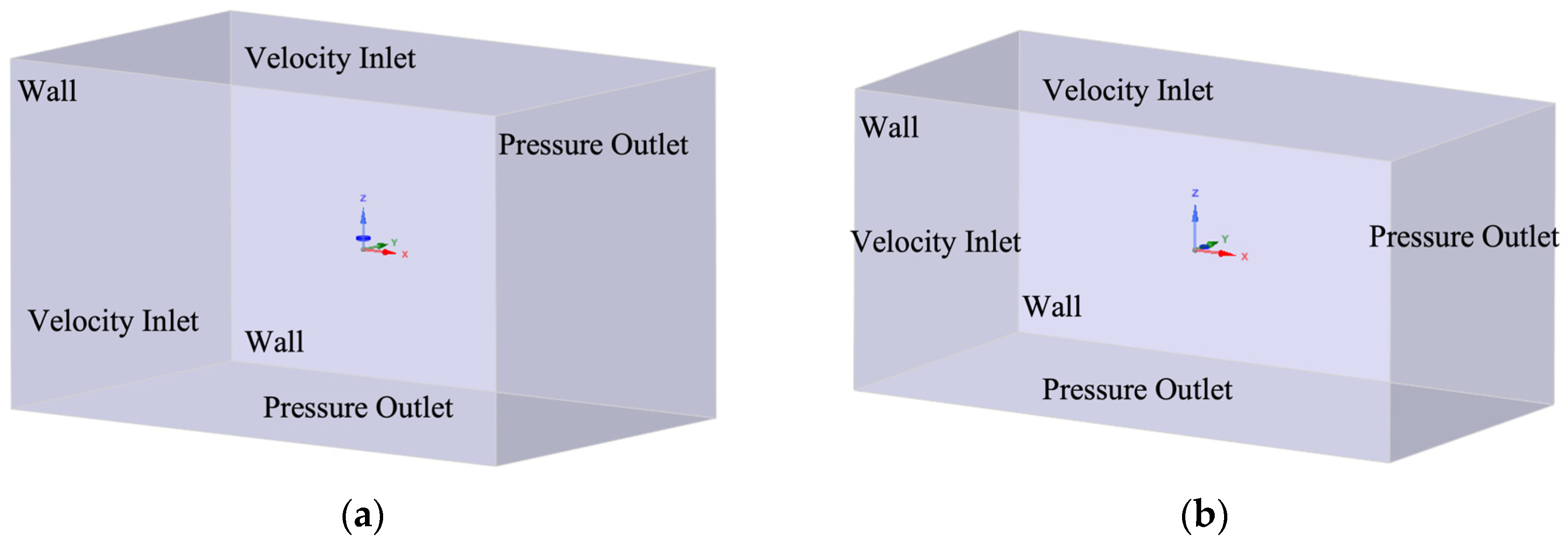

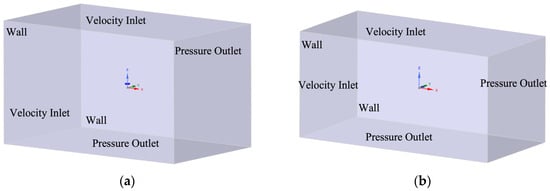

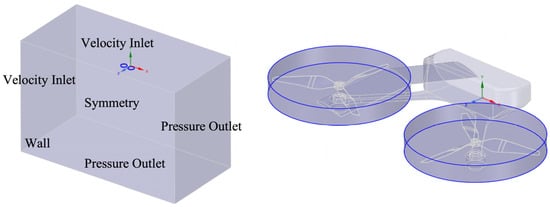

The rotor model used was 8045-3, and the propeller model was 4045-3. The computational domain for an isolated rotor or propeller is illustrated in Figure 6. To accurately simulate the rotational effects, a combined stationary and rotating domain approach was adopted: a rotating region was defined immediately surrounding the blades, enclosed by an outer stationary region.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the mesh domain for an isolated rotor or propeller: (a) Rotor; (b) Propeller.

For the rotor (corresponding to Figure 1), its rotating region was a cylinder with a diameter of 212 mm and a height of 28 mm, with a gap equivalent to 5% of the rotor diameter between the cylindrical surface and the blade tip. The external stationary region was a rectangular box measuring 10212 mm in length, 6212 mm in width, and 6028 mm in height. The boundary conditions were set as follows: the top and front surfaces were velocity inlets, the bottom and rear surfaces were pressure outlets, and all other external surfaces as well as the rotor surface were modeled as no-slip walls. A grid independence study was conducted for the hover condition at 4000 rpm, with the results summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of simulation results for the rotor in hover at 4000 rpm using different mesh densities.

Considering both accuracy and computational efficiency, the medium-density mesh scheme was selected for the final simulations. This scheme featured refinement in the rotating region and on the rotor surface, with a surface mesh size of 0.3 mm for the rotor and a cell size of 1 mm in the rotating region.

For the propeller (corresponding to Figure 1), its rotating region was a cylinder with a diameter of 110 mm and a height of 20 mm, maintaining a gap of 5% of the propeller diameter between the cylindrical surface and the blade tip. The external stationary region was a rectangular box with dimensions of 8110 mm in length, 4110 mm in width, and 4020 mm in height. The boundary conditions were consistent: the top and front surfaces were velocity inlets, the bottom and rear surfaces were pressure outlets, and all other external surfaces along with the propeller surface were set as no-slip walls. A grid independence study was performed for the hover condition at 20,000 rpm, with the results presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of simulation results for the propeller in hover at 20,000 rpm using different mesh densities.

Balancing accuracy and computational cost, the medium-density mesh scheme was ultimately selected. This scheme incorporated refinement in both the rotating region and on the propeller surface, utilizing a surface mesh size of 0.3 mm for the propeller and a cell size of 0.8 mm within the rotating region.

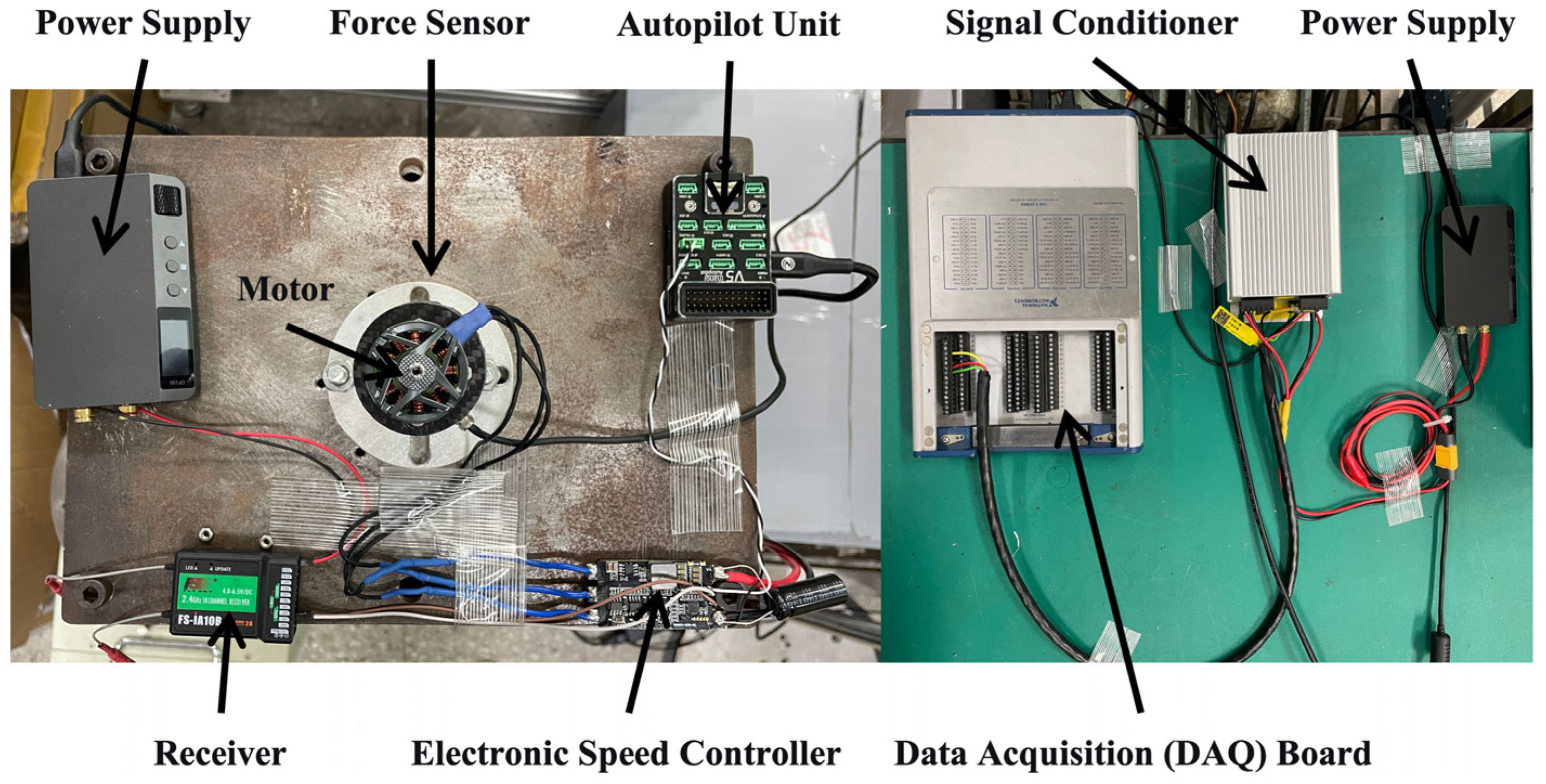

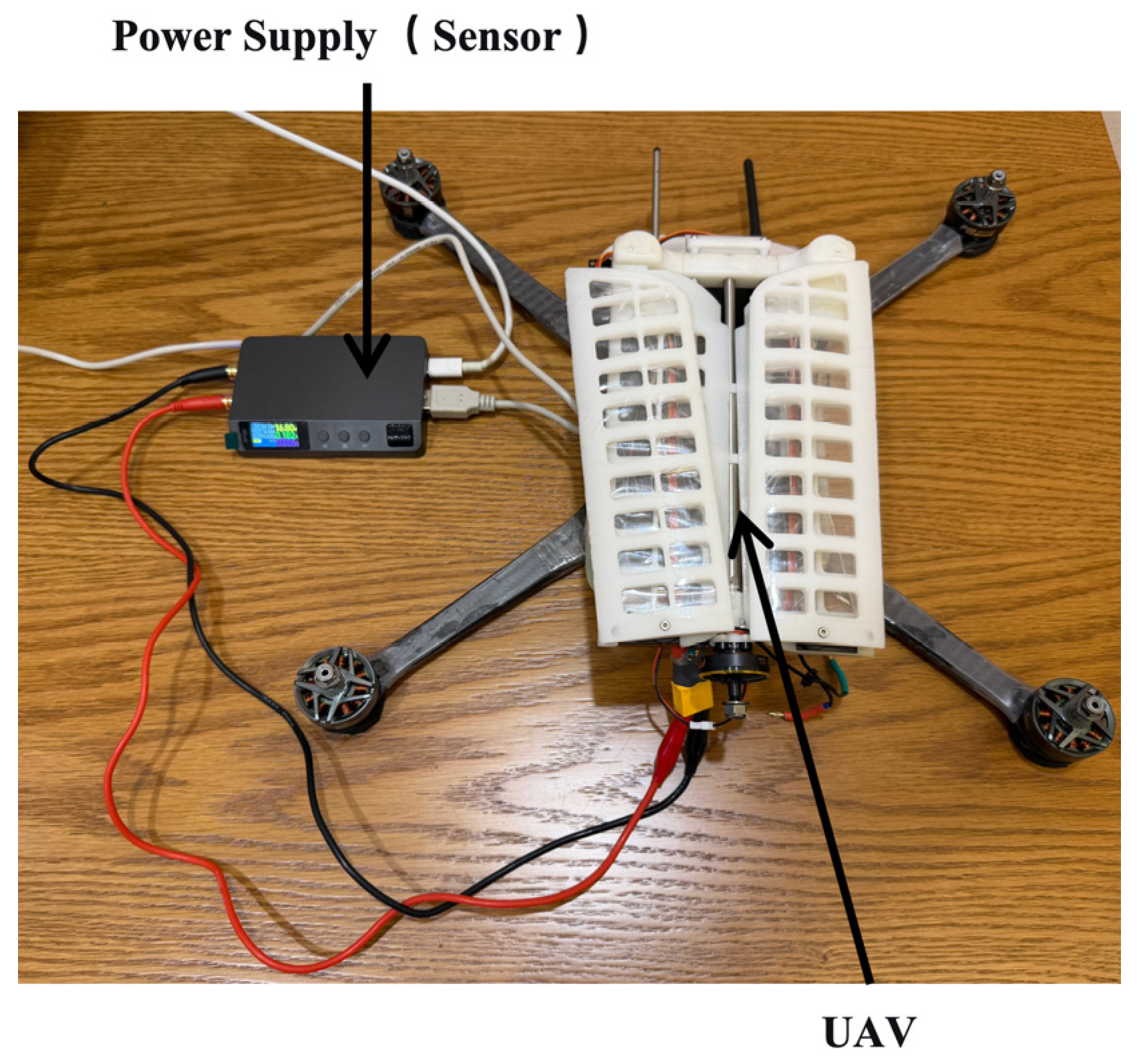

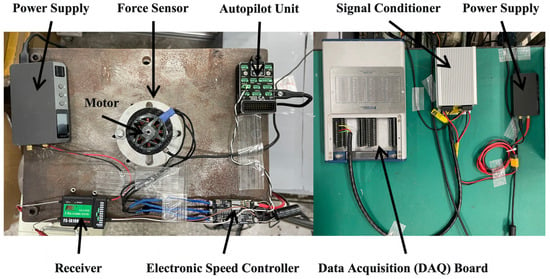

To validate the accuracy of the CFD methodology, experimental tests were conducted on both the rotor and the propeller in hover. The experimental data at various rotational speeds were compared with the numerical simulation results. The layout of the experimental system is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for rotor/propeller thrust measure.

The rotor and propeller were installed in an inverted configuration, directing their wake towards the ceiling. This arrangement eliminated ground effect interference, ensuring the measured aerodynamic performance reflected their true characteristics. Rotational speed control and monitoring were implemented via the following system: An Autopilot V5 nano flight controller (Guangzhou CUAV Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), paired with an Electronic Speed Controller (ESC) (Shenzhen Flycolor Electronic Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) capable of real-time RPM feedback, transmitted the instantaneous rotational speed to the flight controller. The rotational speed, motor current, and supply voltage were then monitored wirelessly using the Mission Planner (1.3.82) ground station software. Commands to start, stop, and adjust the speed were conveniently sent to the flight controller via an RC transmitter (Shenzhen Flysky Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China).

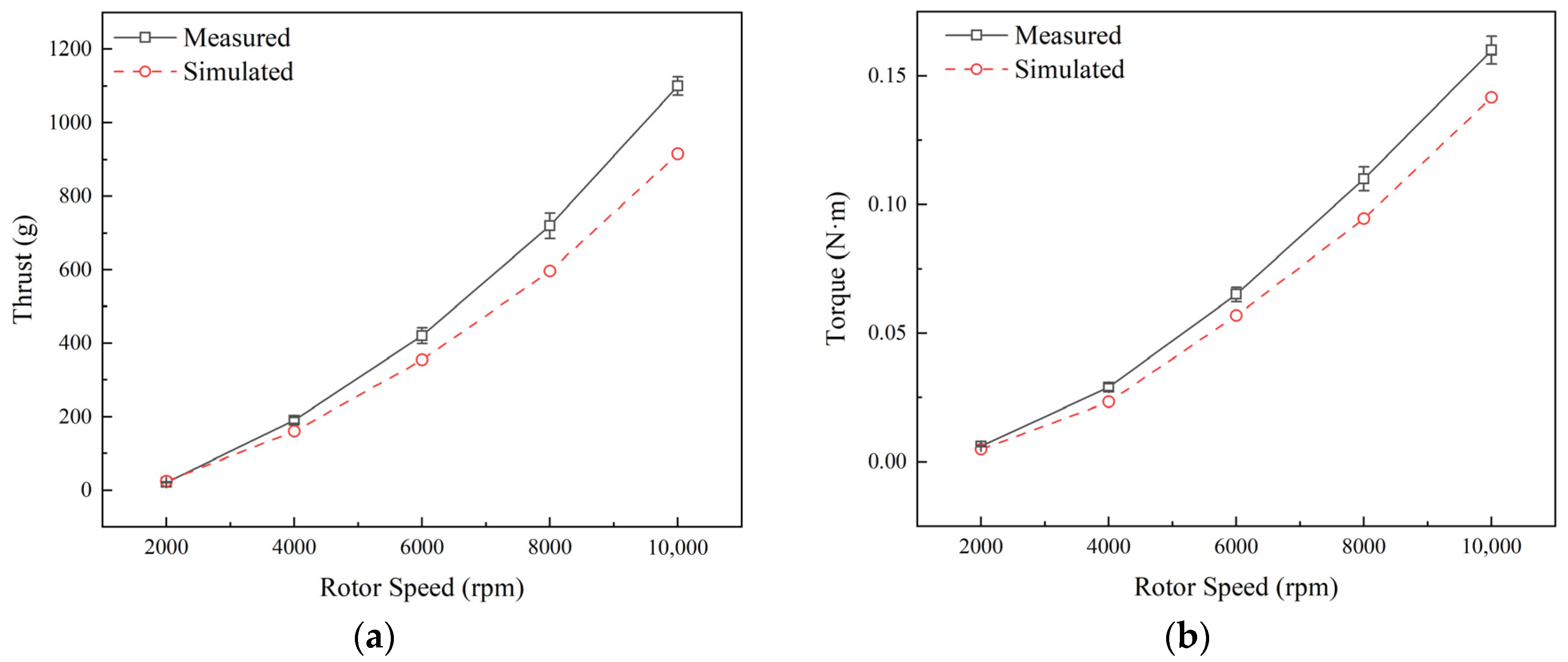

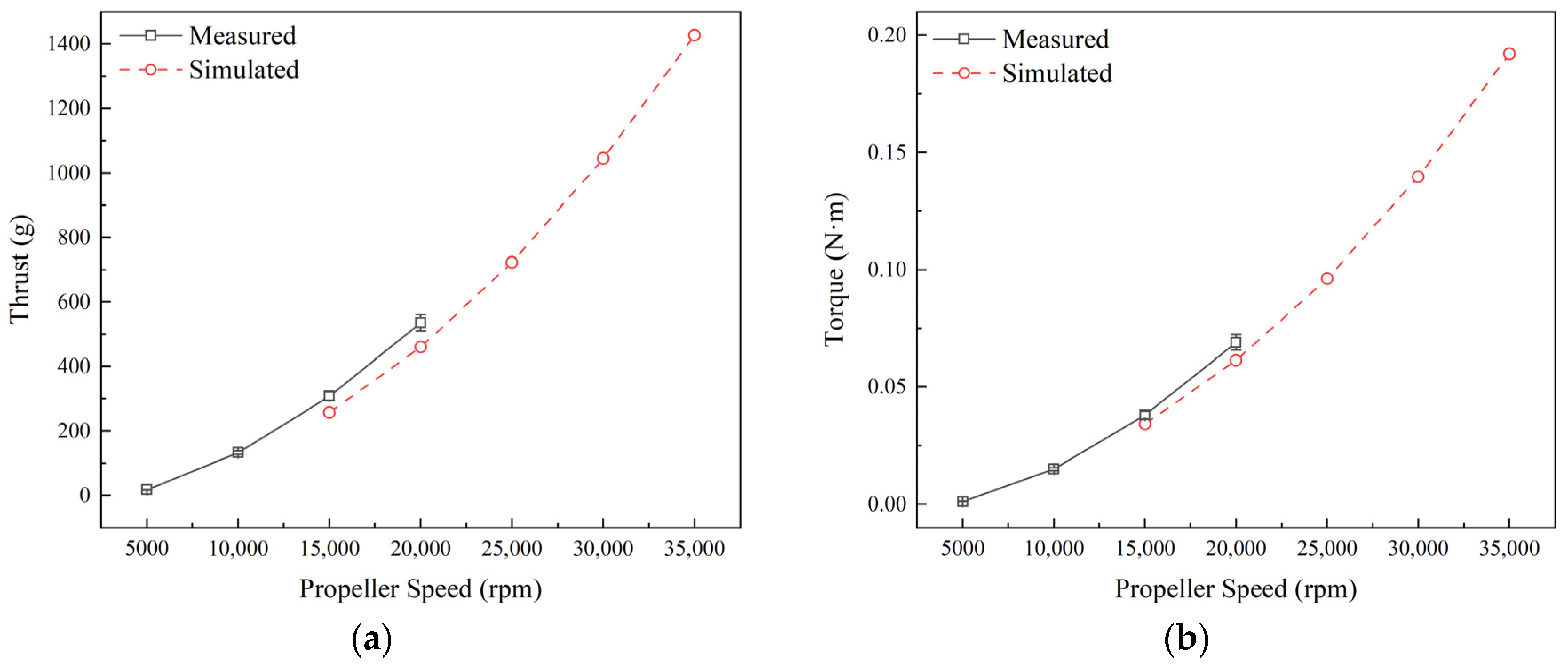

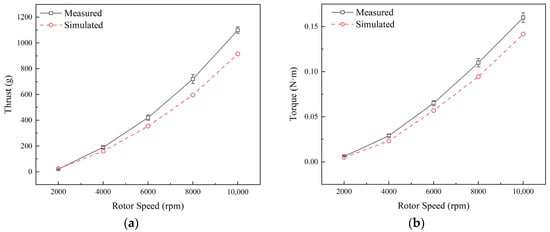

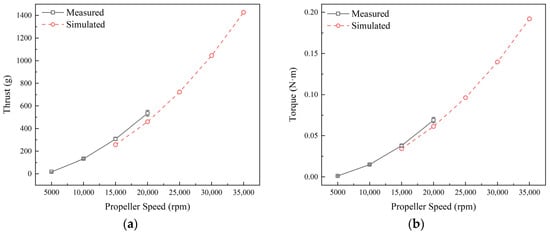

Thrust and torque measurements were acquired using a high-precision system. The core sensors were a two-component force/torque balance (Shenzhen HUATRAN Test Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) with ranges of 100 N and 2 N·m, offering a measurement accuracy of 0.3% of full scale (FS). The weak analog signals from the balance were conditioned through amplifiers (Shenzhen HUATRAN Test Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) for filtering and amplification to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, and subsequently recorded by a data acquisition system (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The acquisition software supported multi-channel synchronous sampling at a rate of 1000 Hz, enabling real-time monitoring and complete recording of the thrust and torque over time. Following data processing, thrust and torque curves for the rotor and propeller across different speeds were obtained, as presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively.

Figure 8.

Rotor thrust and torque at different rotational speeds: (a) Thrust; (b) Torque.

Figure 9.

Propeller thrust and torque at different rotational speeds: (a) Thrust; (b) Torque.

The overall trends of the simulation results were in good agreement with the experimental data. However, the absolute discrepancy between them gradually increased with higher rotational speeds. For the rotor, the experimentally measured thrust values were slightly higher than the simulated ones, with a maximum relative error of approximately 17%. The experimental torque values were also higher than the simulations, with a maximum relative error of about 19%. For the propeller, both the experimental thrust and torque values exceeded the simulated ones, with maximum relative errors of approximately 16% and 11%, respectively. Despite these deviations, the simulation and experiment showed satisfactory agreement in trend. The error margins remain within an acceptable range for engineering purposes. This validates the feasibility of the adopted CFD method and setup, confirming its suitability for subsequent aerodynamic characteristic analysis and evaluation.

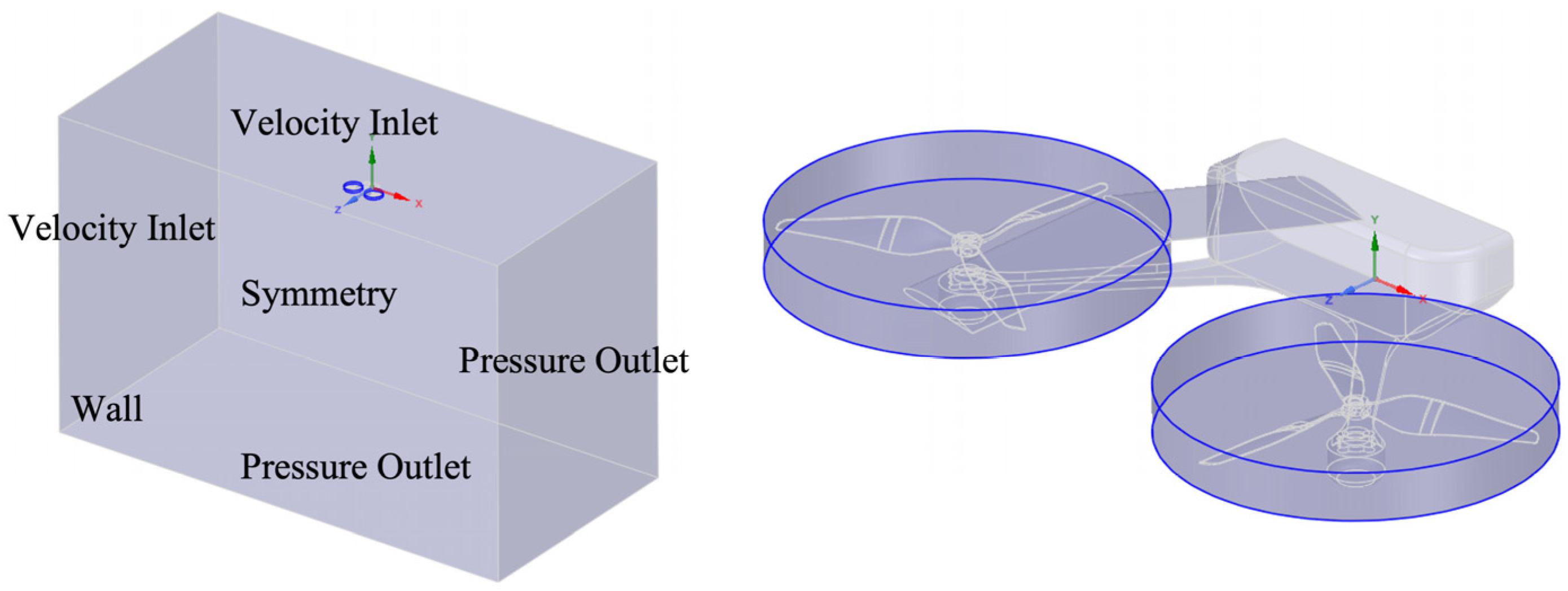

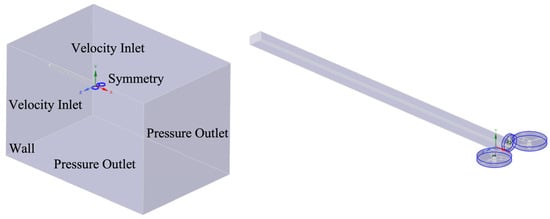

For the case study investigating the effect of the first wing segment’s dihedral angle on both wing and rotor performance, the computational domain and mesh layout are shown in Figure 10. To improve computational efficiency, only the left half of the aircraft was modeled. The meshing strategy for the rotor’s rotating region was consistent with the setup described earlier for the isolated rotor simulation. The external stationary domain was a rectangular box with dimensions of 6000 mm in length, 3000 mm in width, and 4000 mm in height. The boundary conditions were set as follows: the top and front surfaces were defined as velocity inlets; the rear and bottom surfaces were pressure outlets; the lateral surface furthest from the aircraft was set as a no-slip wall; and the lateral surface closest to the aircraft’s centerline was defined as a symmetry plane. The surfaces of the fuselage, wings, and rotor were all modeled as no-slip walls.

Figure 10.

Schematic of the mesh domain for studying the effect of wing dihedral angle.

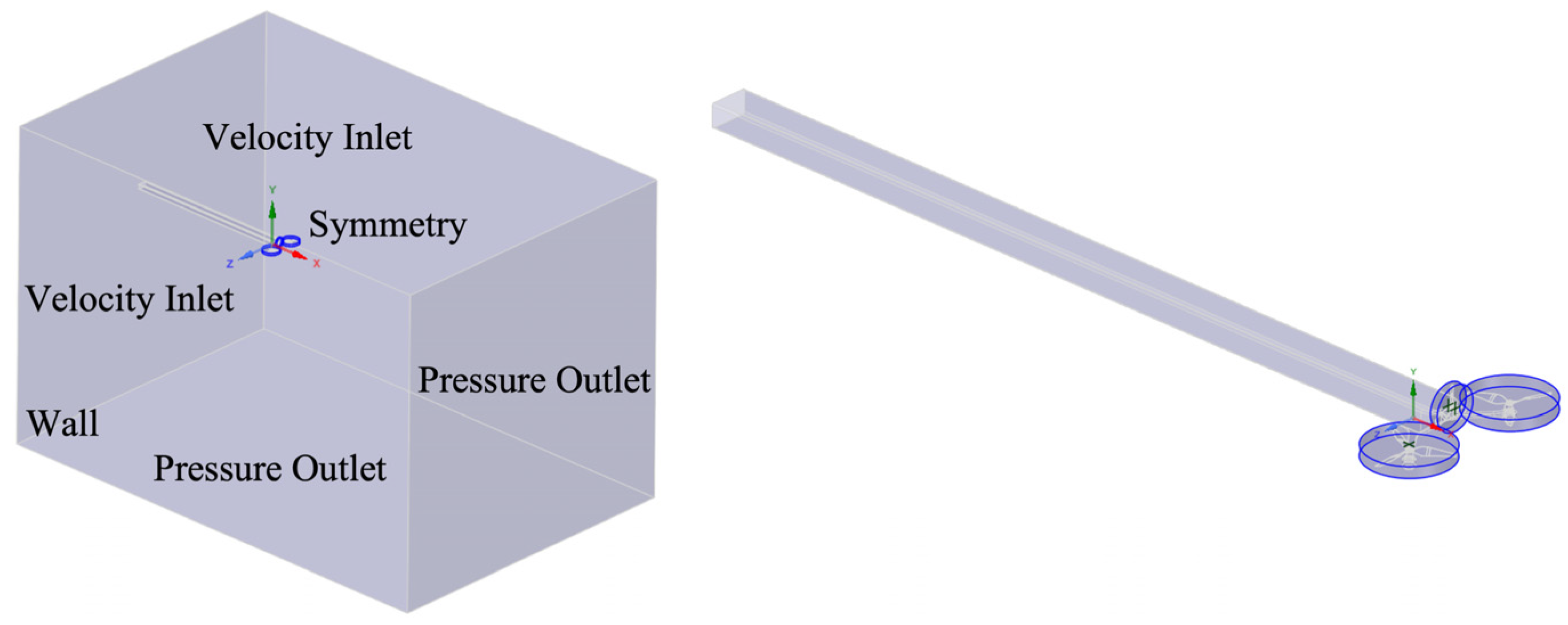

To investigate the aerodynamic interaction between the rotor and the tail-thrust propeller, the mesh configuration shown in Figure 11 was employed. The meshing strategy for the individual rotating regions of both the rotor and the propeller followed the same specifications used for their respective isolated component simulations. To enhance computational efficiency, only the rear half of the aircraft was modeled, and the fuselage was extended from its cross-section to the inlet boundary. The external stationary domain was a rectangular box measuring 6000 mm in length, 4000 mm in width, and 4000 mm in height. The boundary conditions were set as: the top and front surfaces as velocity inlets; the rear and bottom surfaces as pressure outlets; and all other external surfaces as no-slip walls. The surfaces of the fuselage, rotor, and propeller were also defined as no-slip walls.

Figure 11.

Schematic of the mesh domain for studying rotor-propeller interaction.

4. Forward-Flight Power Consumption Model

4.1. Traditional Multirotor Aircraft

The power consumption of a traditional multirotor aircraft is primarily composed of propulsion power and non-propulsion power (e.g., communication-related power) [27]. Propulsion power, which constitutes the major portion, is required for maintaining aerial attitude and overcoming aerodynamic drag. It mainly includes rotor induced power, profile power, and parasitic power of the rotor.

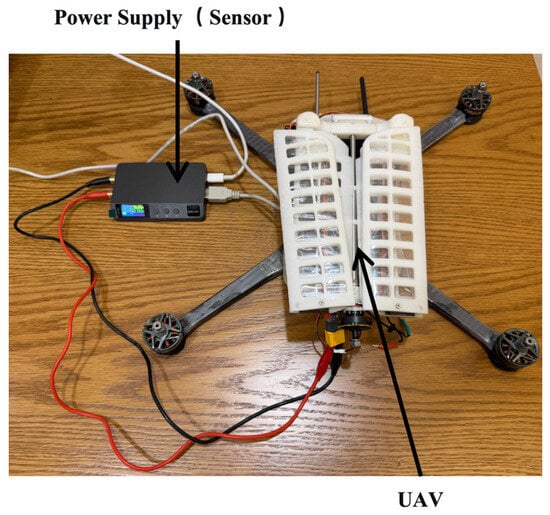

To quantify the proportion of non-propulsive power in total consumption, a regulated power supply (Guangzhou Xingyi Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. (punctime atom), Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) with real-time voltage and current monitoring and logging capabilities (Figure 12) was used to power the small quadrotor UAV employed in subsequent experiments. The measured non-propulsive power was approximately 3 W, which is significantly lower than the typical propulsive power of conventional multi-rotor aircraft. Additionally, the power consumption during the wing deployment process was recorded, showing a peak power of about 5 W over a duration of 15 seconds. The total energy consumed in this process is also far less than the propulsive energy expenditure of conventional multi-rotors.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for non-propulsive power measurement.

Taking a quadrotor as an example, the force equilibrium in forward flight satisfies the following relationship:

In these equations, represents the total weight of the aircraft, denotes the drag force experienced by the aircraft at the current velocity and attitude, represents the thrust of a single rotor and signifies the pitch angle (defined as negative when the nose is pitched downward in forward flight). Based on momentum theory, the rotor thrust can be expressed as:

In the equation, represents the air density, denotes the rotor disk area, is the aircraft’s forward airspeed, and signifies the rotor induced velocity. Consequently, the analytical expression for the induced velocity in forward flight is derived as:

In the equation, represents the rotor induced velocity in the hover state of the aircraft. Thus, the induced power of the rotor in forward flight can be calculated as:

Additionally, the rotor consumes power to overcome profile drag, termed the profile power:

In the equation, is the rotor solidity, is the profile drag coefficient, is the rotor rotational speed, and is the rotor radius. Meanwhile, during high-speed forward flight, the rotor expends considerable parasitic power to overcome the fuselage drag:

Since the non-propulsion power is negligible compared to the propulsion power (i.e., the power consumed by the rotors), the total power consumption of the aircraft can be reasonably approximated as being entirely sourced from the rotors. This total power can be expressed as the sum of the induced power, profile power, and parasitic power:

In traditional multirotor forward flight, the airframe must pitch downward to generate horizontal thrust. In this attitude, the total rotor thrust required to balance gravity and drag exceeds that of the hover state, leading to an increase in rotational speed. Furthermore, the enlarged frontal area of the fuselage results in a significant rise in parasitic power. The combined effect of these factors causes the power consumption in forward flight to substantially exceed that of hovering. A further increase in speed typically requires a greater pitch angle, thereby initiating a cycle of increasing drag and thrust demand, which consequently exacerbates the power consumption.

For the most extreme condition encountered subsequently in this study—a forward speed of , a rotor speed of 8000 rpm, and a fuselage pitch angle of —analysis confirms the applicability of the momentum theory model. First, the effective inflow velocity component parallel to the rotor disk is approximately . The resulting effective advance ratio is approximately 0.193 (based on a tip speed of ), which is well below 0.3, indicating weak inflow asymmetry across the rotor disk. Second, although the rotor tip Mach number is approximately 0.25, the maximum local Mach number occurring at the tip of the advancing blade () is about 0.298—still below the commonly used critical value of 0.3—suggesting that compressibility effects are negligible. Therefore, under this effective advance ratio, the rotor flow field satisfies the fundamental assumptions of momentum theory, justifying its use as a valid and effective baseline for performance comparison.

4.2. Multirotor Aircraft with Folding-Wing Range Extender

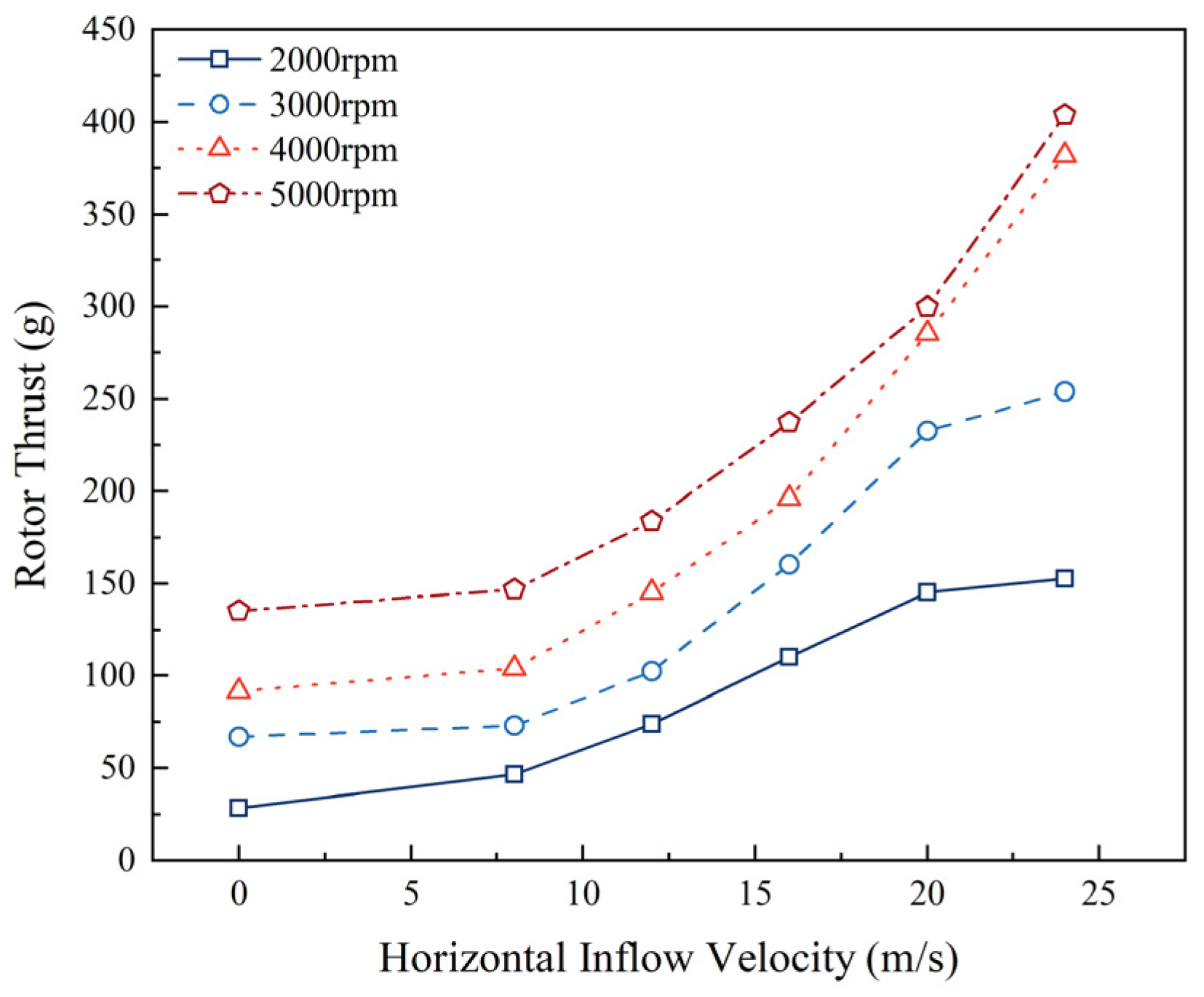

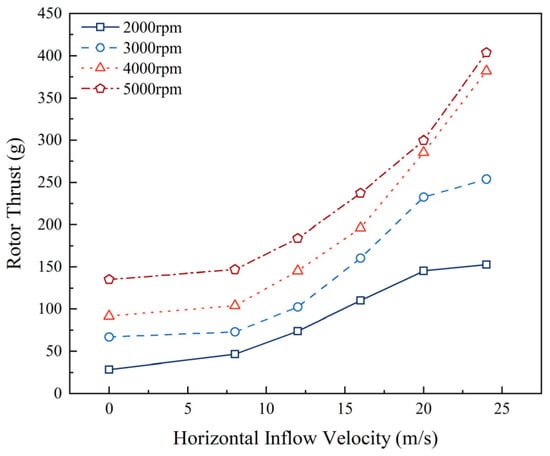

For a small multirotor UAV equipped with the Folding-Wing Range Extender, when the wings are deployed for the cruise state, the tail-thrust propeller drives the aircraft forward in a level attitude. In this configuration, the rotors operate in an oncoming horizontal airflow environment, resulting in a variation in thrust. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations were conducted on an isolated rotor across different rotational speeds (2000 rpm to 5000 rpm) and varying inflow velocities (8 m/s to 24 m/s). The resulting thrust variation is presented in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Rotor thrust versus oncoming horizontal airflow velocity at different rotational speeds (2000 to 5000 rpm).

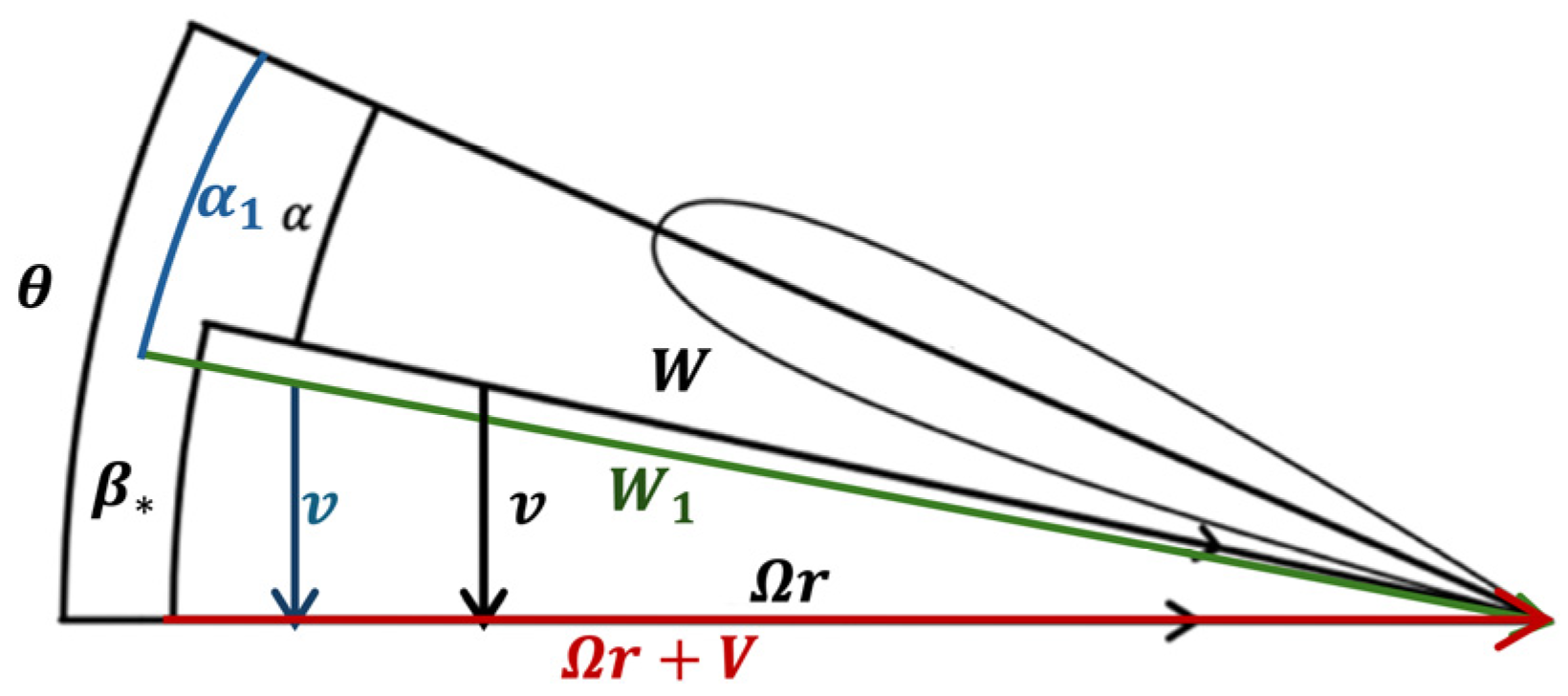

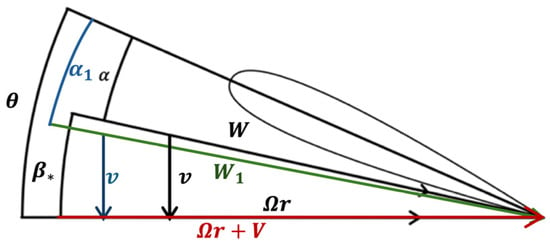

Within the computed range of rotational and inflow velocities, the oncoming horizontal airflow significantly enhances rotor thrust. This enhancement effect increases nonlinearly with the inflow velocity. Consequently, the rotor’s capability to generate thrust under the influence of the horizontal airflow is improved, leading to reduced power consumption for delivering the same level of thrust. Due to the significant aerodynamic asymmetry between the advancing and retreating sides of the rotor under oncoming horizontal airflow, the rate of lift increase diminishes for rotors operating at lower rotational speeds when subjected to higher inflow velocities. An aerodynamic analysis was conducted on a blade element from the advancing side to elucidate the underlying mechanism, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Variation in the Angle of Attack of a Rotor Blade Element on the Advancing Side under Oncoming Horizontal Airflow.

The superposition of the rotor blade element’s linear velocity and the oncoming airflow velocity increases the resultant horizontal airspeed. Consequently, the angle of incidence decreases, resulting in an increase in the effective angle of attack () of the advancing-side blade element. This relationship can be quantitatively described by:

In the equations, is the radial position of the blade element, is the rotor azimuth angle, is the installation angle at the blade element, is the induced velocity, and is the oncoming airflow velocity. Prior to stall, the lift coefficient increases proportionally with the angle of attack. Meanwhile, the increased airspeed on the advancing side raises the Reynolds number, resulting in a more stable boundary layer and a further increase in the lift coefficient. The modified model is given by:

where is the lift-curve slope under hover conditions at the reference Reynolds number. , and is the dimensionless Reynolds number correction factor quantifying the sensitivity of the lift-curve slope to . Equation (9) clarifies that the instantaneous lift coefficient is co-determined by the local angle of attack and the local lift-curve slope , the latter being modulated by the Reynolds number. Furthermore, the increased airspeed leads to a rise in dynamic pressure, thereby directly augmenting the lift. Consequently, the lift of the blade element can be expressed as:

In the equations, is the resultant airspeed and is the blade element chord length. Therefore, the total rotor lift under oncoming horizontal airflow can be obtained through integration:

where is the number of blades.

When deployed, the wings of the FWRE provide additional lift to the aircraft. This lift collaborates with the rotor system in supporting the aircraft’s weight, thereby achieving lift redistribution. As a result, the thrust required from the rotors is reduced, thus decreasing rotor power consumption. The lift generated by the wing can be expressed as:

where is the wing area, is the wing lift coefficient, and is the lift loss coefficient accounting for factors such as structural interference.

For a rotor operating in an oncoming horizontal airflow, the induced power can also be determined using momentum theory. In addition to the induced power, the total power consumed by the rotor includes the profile power. It is important to note that in this flight condition, the parasitic power is borne by the tail-thrust propeller. When the wings are deployed, the tail-thrust propeller provides the propulsive force for horizontal forward flight. In this configuration, the propeller operates under a vertical inflow condition, and its total power consumption comprises induced power, profile power, and a substantial portion of parasitic power. Similarly, the total power consumption of the aircraft can be reasonably approximated as being entirely sourced from the rotors and the tail-thrust propeller. This total power can be expressed as the sum of their respective induced power, profile power, and parasitic power:

In summary, the deployment of the FWRE significantly enhances the energy consumption efficiency of the multirotor UAV by fundamentally improving its aerodynamic characteristics. First, the lift generated by the wings offloads a portion of the aircraft’s weight, thereby reducing the lift required from the rotors. This aerodynamic unloading effect directly decreases rotor power consumption. Second, in level forward flight, the oncoming airflow further enhances the rotor’s thrust-generating capability, consequently reducing its power demand. Additionally, in this state, the rotors incur no parasitic power. Although the tail-thrust propeller consumes a certain amount of power during propulsion, the overall aerodynamic drag of the aircraft in level-attitude forward flight is significantly lower than that of a traditional multirotor operating at a pronounced pitch angle. Consequently, while the traditional multirotor incur substantial power increments due to attitude adjustments and heightened drag during forward flight, the range-extender equipped UAV achieves lower net power consumption at the same airspeed, resulting in effectively enhanced overall propulsion efficiency.

Under the extreme condition considered in subsequent research—a forward speed of and a rotor speed of approximately 3500 rpm—the model developed in this work incorporates the azimuth angle to accurately capture the aerodynamic asymmetry at this advance ratio. Furthermore, the inclusion of a Reynolds number correction enhances the model’s accuracy. Under this configuration, the rotor tip speed is about , yielding an advance ratio of approximately 0.55. The maximum local Mach number is around 0.166, which is well below the threshold of 0.3, indicating that compressibility effects are entirely negligible. Therefore, the accuracy of the model is sufficient to support a reliable evaluation of the energy performance under this operating condition.

5. Simulation Study on Forward Flight Power of Aircraft

5.1. Simulation Parameters and Operating Conditions

This section presents a simulation study based on the established theoretical framework. The subjects include a self-designed 1-kg-class quadrotor UAV and its matching folding-wing range extender. This weight class represents the mainstream configuration of current lightweight commercial drones (e.g., DJI Mavic 4T) [15], which are widely employed in inspection, surveying, mapping, and similar fields, thereby ensuring clear relevance to real-world applications. Schematic diagrams of the UAV and the range extender are provided in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively, with their key design parameters detailed in Table 3. The initial selection of the angle of incidence was based on the typical cruise speed range of small multirotor UAVs, aiming to operate the wing at its maximum lift-to-drag ratio within this regime, thereby optimizing cruise efficiency.

Table 3.

Parameters of the Simulation Objects.

It is noteworthy that the drag coefficient only increased slightly after wing deployment. This reflects the unique aerodynamic mode shift introduced by the range-extender installation: the deployed, efficient wings assume the primary lift, substantially offloading the rotors and significantly reducing their induced drag. This reduction largely offsets the additional drag contributed by the wings themselves, resulting in a relatively small change in the overall drag coefficient.

To directly compare the power consumption of the baseline UAV in forward flight with that of the same UAV equipped with the FWRE, and to separately quantify the contributions of the oncoming horizontal airflow and the wing unloading effect to the reduction in power consumption, the following three flight conditions are established in the simulation:

Baseline Multirotor flight condition, abbreviated Baseline MR: The host quadrotor UAV operates without the range extender, flying in traditional multirotor mode, and serves as the performance baseline;

Folded Range-Extension (Propulsive Mode) flight condition, abbreviated F-RE (P Mode): The host quadrotor UAV is equipped with the FWRE. With wings in the folded state, the tail-thrust propeller drives the aircraft in level-attitude forward flight. The rotors provide the entire lift and maintain attitude control. This condition serves to validate and quantify the performance optimization effect of the oncoming horizontal airflow on the rotors;

Deployed Range-Extension flight condition, abbreviated D-RE: The host quadrotor UAV is equipped with the FWRE. With wings deployed, the tail-thrust propeller drives the aircraft in level-attitude forward flight. This condition represents the typical operational state of the UAV with the extender and is used to evaluate the overall performance improvement. By comparing it with the F-RE P Mode, the contribution of the wings to the reduction in vehicle energy consumption can be quantified.

The power consumption of an aircraft is a key performance metric determining its range, endurance, mission economy, and operational capability, reflecting the output state of the motors. To evaluate the performance of the range extender, this study calculates the power consumption of the aircraft in the aforementioned three flight conditions under trimmed states at forward flight speeds of 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20 m/s. The overall benefit of the device is quantified by comparative analysis of the total power consumption and the respective power consumption of the rotors and the tail-thrust propeller.

5.2. Simulation Results and Analysis

5.2.1. Power Consumption Analysis Under Different Flight Conditions

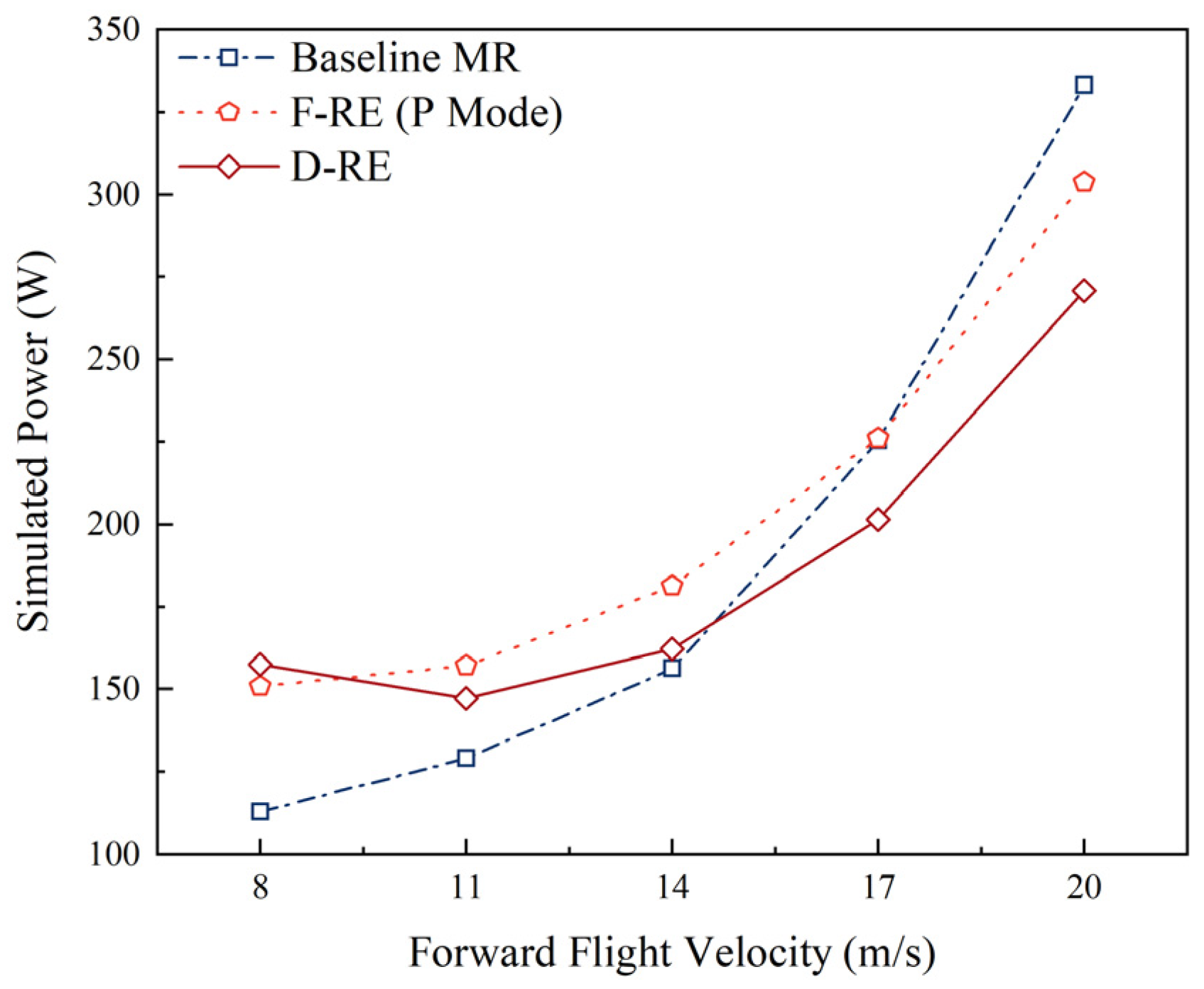

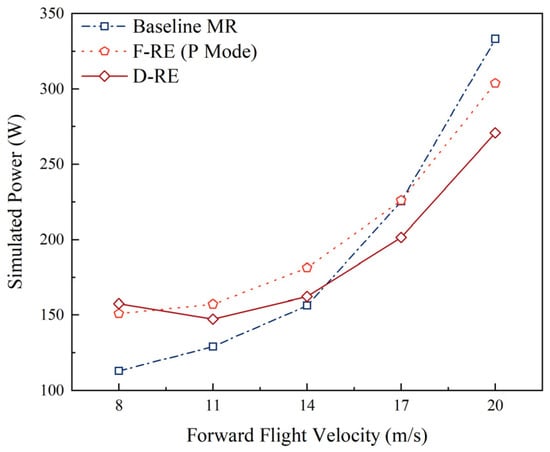

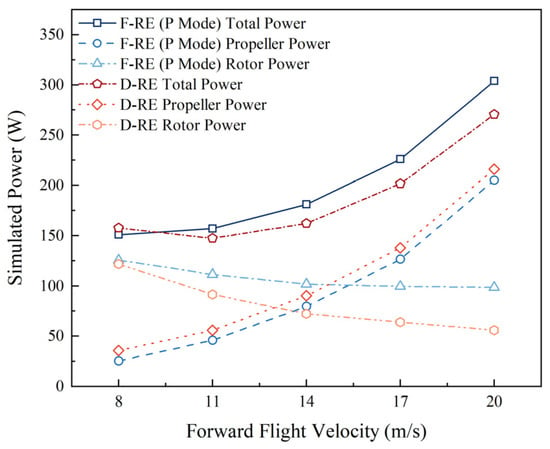

Figure 15 presents the simulated total power consumption of the aircraft across forward flight speeds ranging from 8 to 20 m/s under different flight conditions. As the airspeed increases, the total power of the aircraft under both the Baseline MR and F-RE (P Mode) conditions exhibits a nonlinear growth trend. In contrast, the total power under the D-RE condition initially shows a slight decrease, followed by a gradual increase. The underlying mechanisms are as detailed below: For the Baseline MR condition, the aircraft requires an increased pitch angle and higher rotor speed to generate sufficient thrust for overcoming aerodynamic drag and providing adequate lift, resulting in the highest rate of power increase. Although the F-RE (P Mode) incurs additional power consumption from the tail-thrust propeller, it demonstrates a lower power increase rate than the Baseline MR due to the beneficial effect of oncoming horizontal airflow on rotor efficiency. The D-RE condition, benefiting from both wing unloading and oncoming airflow mechanisms, exhibits the mildest power increase. Furthermore, at forward speeds below 11 m/s, the power saved from the rotors exceeds the consumption of the tail-thrust propeller, leading to a slight decrease in total power.

Figure 15.

Simulation results showing the variation characteristics of total aircraft power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different flight conditions.

In addition, the relative magnitude of power consumption across different flight conditions exhibits speed dependence. Due to the absence of the added weight and drag from the FWRE, the Baseline MR flight condition demonstrates the lowest power consumption at low speeds. Additionally, since the benefits of wing unloading and oncoming horizontal airflow optimization are not yet fully realized, the D-RE flight condition, with its deployed wings introducing additional drag, requires higher rotational speed of the tail-thrust propeller to generate compensatory thrust, resulting in a power consumption slightly higher than that of the F-RE (P Mode), flight condition. When the speed approaches 15 m/s, Baseline MR flight condition power consumption becomes comparable to that of the D-RE flight condition. The speed at which the Baseline MR flight condition matches the power consumption of the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition, devoid of wing unloading effects, is delayed until approximately 17 m/s. This phenomenon clearly demonstrates the critical role of wing unloading in reducing power consumption. At 20 m/s, the total power consumption of the F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions is reduced by approximately 8.5% and 18.7%, respectively, compared to the Baseline MR flight condition, fully demonstrating the energy-saving and range-extending effects of the device.

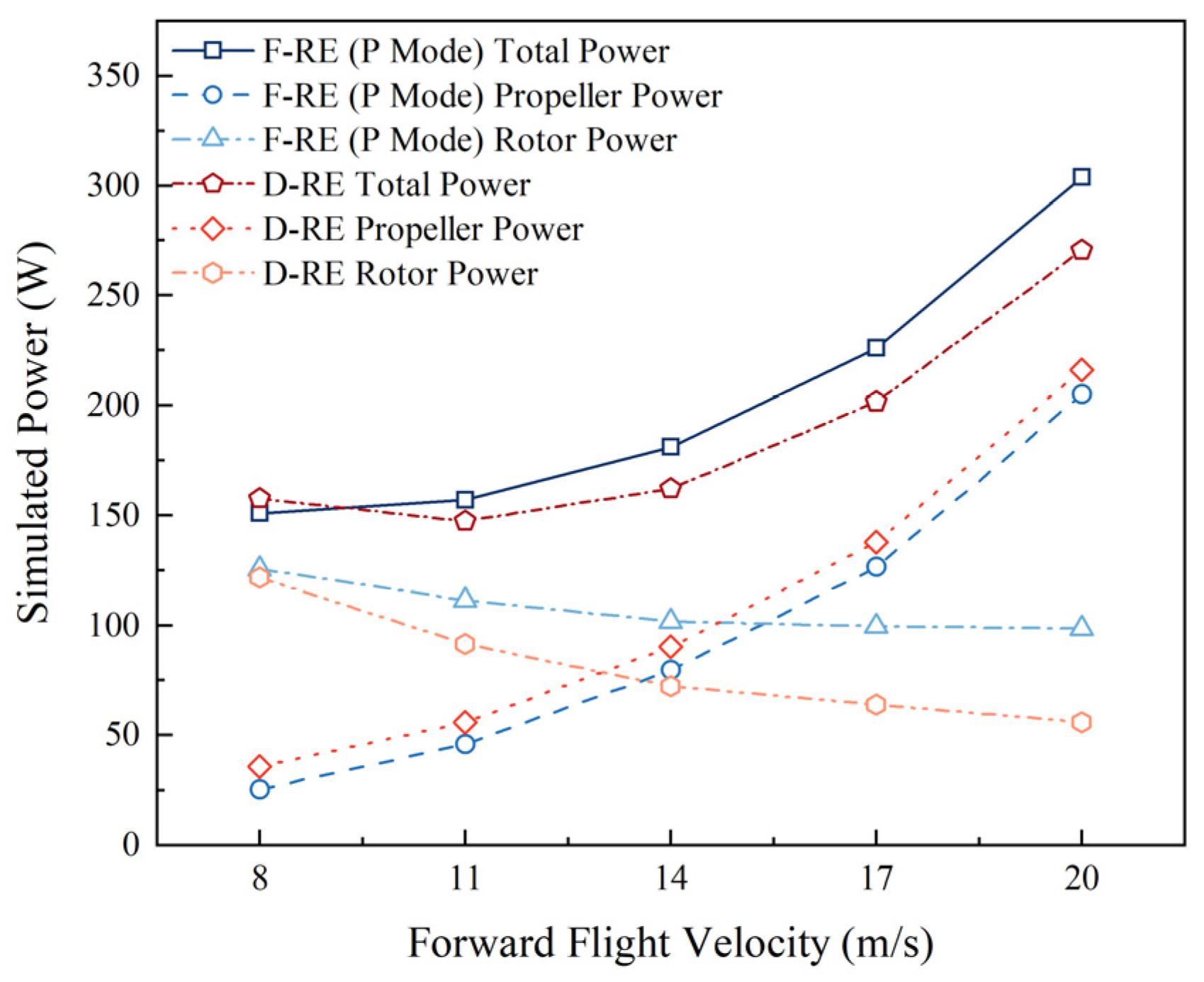

Figure 16 presents the simulated total power, rotor power, and tail-thrust propeller power for the F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions across the forward speed range of 8 to 20 m/s. With increasing speed, the power distribution under these two flight conditions exhibits the following trends: In both flight conditions, the rotor power demonstrates a gradual decreasing trend with increasing forward speed. However, the D-RE flight condition exhibits a significantly more pronounced reduction in rotor power compared to the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition, due to the coupled effects of aerodynamic optimization from the oncoming horizontal airflow and the wing unloading mechanism. It is noteworthy that when the forward speed exceeds 17 m/s, the rotor power of the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition enters a plateau phase, showing almost no further reduction. This is because the asymmetric effects induced by the oncoming horizontal airflow on the rotor become more pronounced at higher speeds, counteracting the potential for further power optimization. In contrast, the rotor power of the D-RE flight condition continues to decrease at a measurable rate, clearly demonstrating the enhanced effectiveness of wing unloading as speed increases. Meanwhile, the propeller power in both flight conditions increases continuously with speed. However, the propeller power under the D-RE flight condition remains consistently higher than that of the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition across the entire speed range. The primary reason is that the deployed wings in the D-RE configuration significantly increase the overall drag, requiring the propeller to output more power to overcome the additional aerodynamic resistance.

Figure 16.

Simulation results showing the variation and distribution characteristics of total aircraft power, rotor power, and propeller power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions.

5.2.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

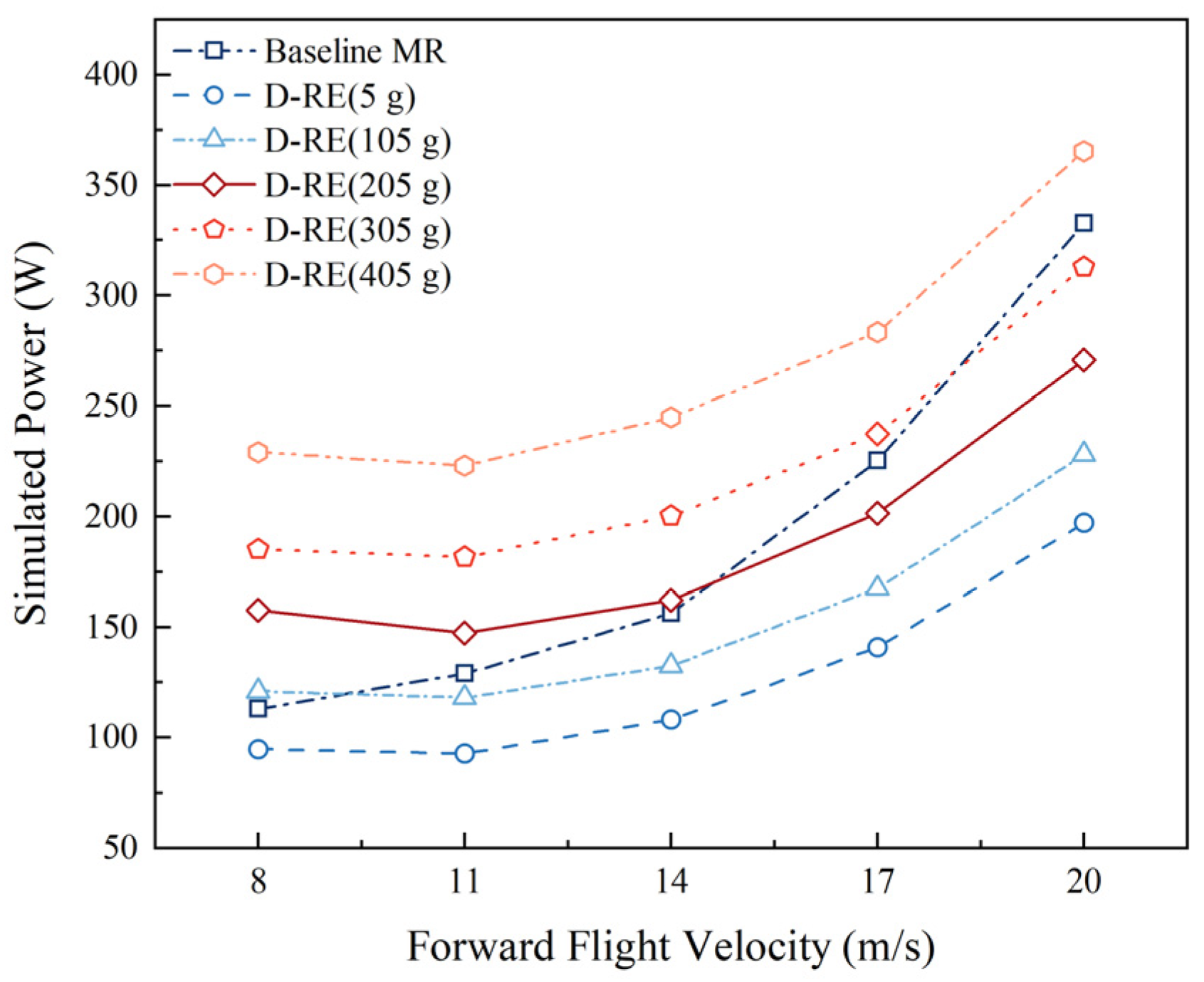

The mass of the folding wing range extender without weight reduction is 205 g, resulting in an increase of approximately 21.35% in the weight of the host aircraft. This increase significantly raised the benchmark energy consumption of the aircraft, thereby severely restricting the range-extending effect of the device. To systematically evaluate the influence of the device mass on its range-extending performance and clarify the upper and lower limits of the theoretical range-extending capacity after the installation of the device, this study conducted a sensitivity analysis of the device mass within the range of 5 g to 405 g. The results are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Simulation results showing the variation characteristics of total aircraft power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different FWRE masses.

The added mass of the device shifts the entire energy consumption curve of the D-RE flight condition upward, while weight reduction correspondingly lowers it. With a reduction of 200 g (i.e., eliminating the device’s mass effect), the D-RE condition exhibits lower energy consumption than the Baseline MR condition across the entire simulated speed range, achieving a reduction of approximately 40.80% at 20 m/s. Conversely, if the device weight were increased by 200 g (increasing the host UAV mass by about 42.19%), the D-RE condition would consume more energy than the Baseline MR condition at all speeds, exceeding it by about 9.65% at 20 m/s. When the device weight is reduced by 100 g (corresponding to a host mass increase of about 10.94%), the speed at which the D-RE and Baseline MR conditions have equal energy consumption advances to approximately 9 m/s. Furthermore, the energy-saving effect becomes more pronounced with increasing speed, nearly covering the typical speed range for small multi-rotor inspection missions, and achieves a consumption reduction of about 31.5% at 20 m/s. On the other hand, if the device weight were increased by 100 g (host mass increase of about 31.77%), the speed of equal energy consumption would be delayed to approximately 18 m/s, and the D-RE condition would only achieve a reduction of about 6% at 20 m/s. This further underscores the critical role of weight reduction in enhancing the device’s energy-saving and range-extending effects.

It should be noted that the current prototype has not undergone dedicated lightweight design, resulting in a relatively large mass (205 g). This is primarily attributed to the use of solid SLA 3D-printed resin structural parts, the wings, and a considerable number of metal connectors (such as bolts, nuts, and sliding rails). The mass distribution of the range extender components is listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mass Distribution of the Range Extender Components.

Preliminary assessment calculations indicate that by adopting an injection molding process, employing lightweight structural designs such as skin-and-rib configurations, and replacing some metal standard parts with lightweight materials, it is possible to achieve a mass reduction of approximately two-thirds for the components other than the servos and motor, without compromising functionality or structural integrity. Estimates suggest that the mass of the optimized device could be reduced to approximately 108.3 g. It is noteworthy that injection molding is a mature technology within the small multi-rotor UAV sector, rendering the proposed lightweighting scheme feasible under current industrial manufacturing and design conditions.

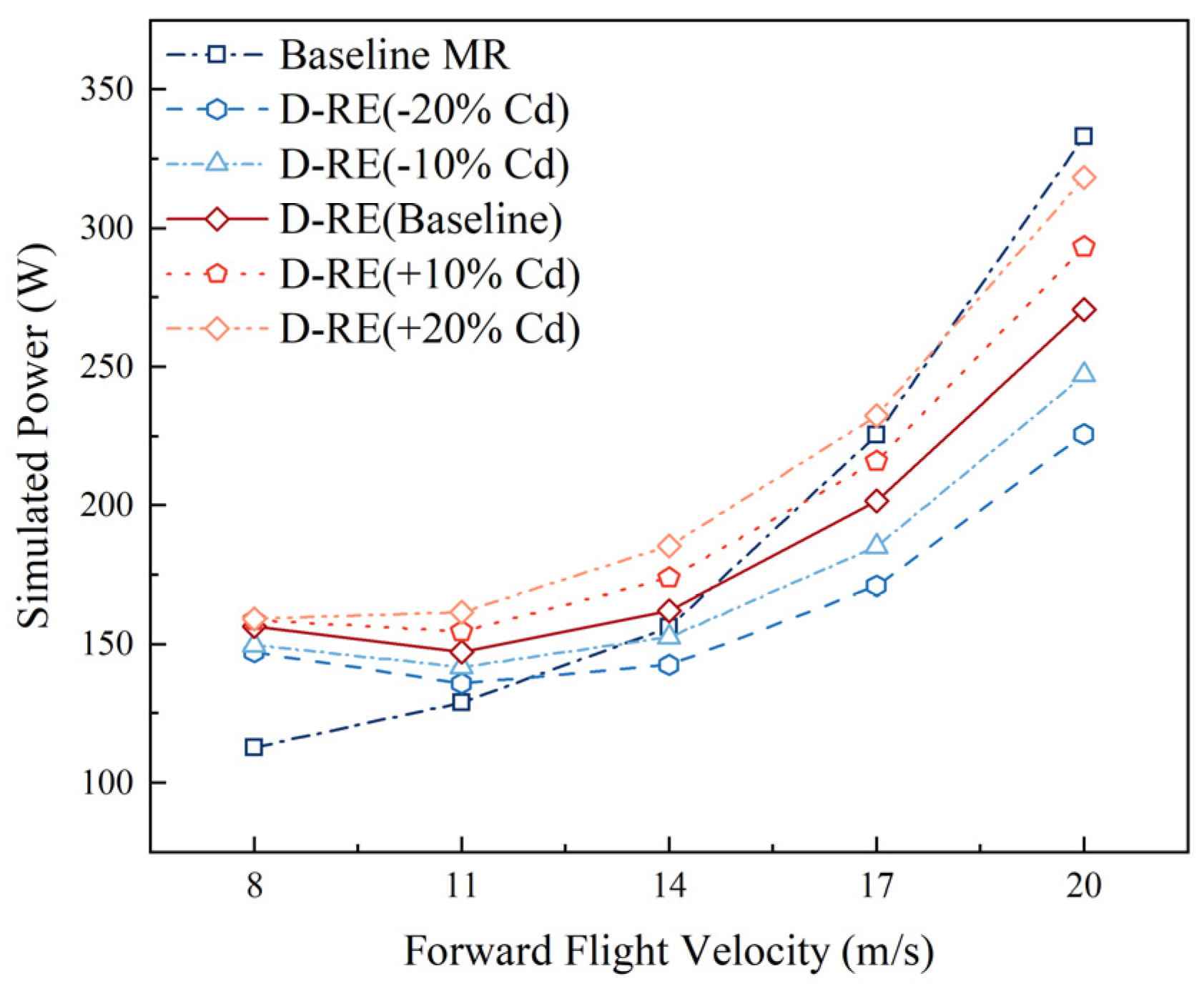

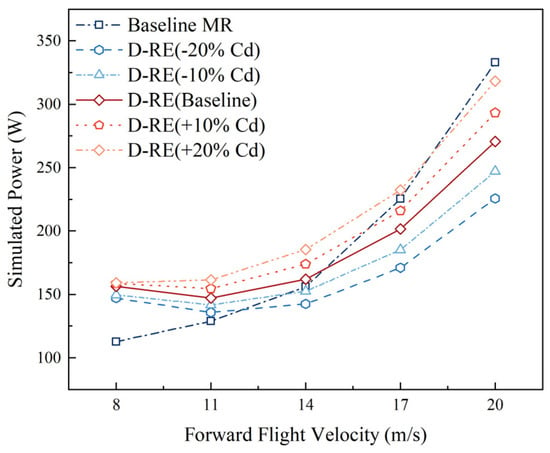

The installation of the Folding-Wing Range Extender introduces additional aerodynamic drag, which subsequently affects its range-extending and energy-saving performance. To quantitatively assess the impact of drag on system performance, a parametric sensitivity analysis was conducted by adjusting the overall vehicle drag coefficient by ±10% and ±20%, with the results presented in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Simulation results showing the variation characteristics of total aircraft power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different overall vehicle drag coefficient.

The analysis indicates that an increase in the drag coefficient elevates the energy consumption curve of the D-RE flight condition, while a decrease lowers it. Due to the nonlinear relationship between drag and flight speed, the impact of drag variation on energy consumption becomes more significant at higher speeds. Specifically, if the drag coefficient is reduced by 10%, the speed at which the energy consumption of the D-RE and Baseline MR conditions become equal advances to approximately 13.5 m/s, and the energy reduction at 20 m/s expands to 25.78%. If the drag coefficient is reduced by 20%, this equal-consumption speed further advances to about 12 m/s, and the energy reduction at 20 m/s can reach 32.20%.

These results demonstrate that, alongside device lightweighting, aerodynamic drag reduction through shape optimization and fairing design also offers considerable potential for improving energy consumption performance. This represents an effective direction for further enhancing the overall benefit of the Folding-Wing Range Extender.

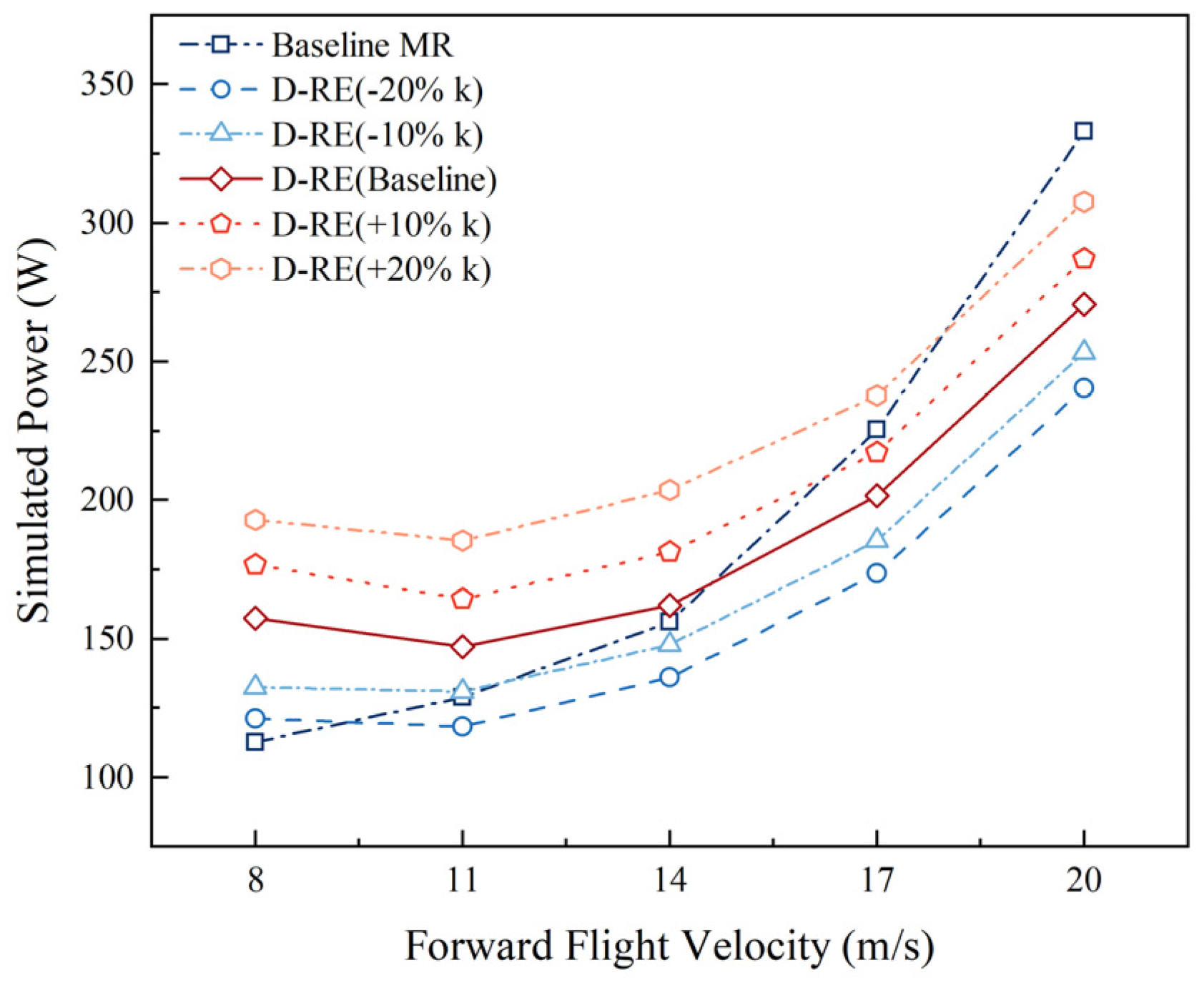

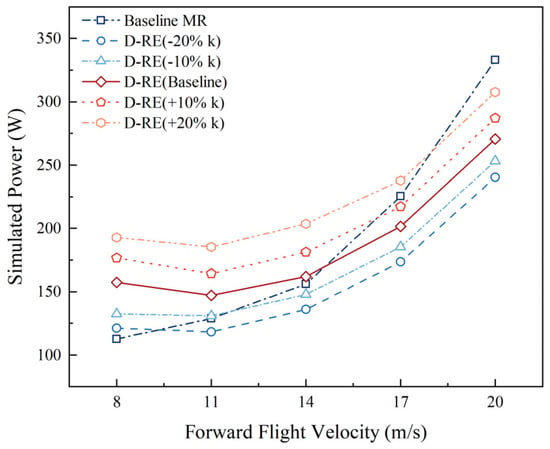

The wing reduces rotor energy consumption primarily by generating lift for rotor offloading. Therefore, the wing’s lift characteristics and aerodynamic efficiency directly influence the device’s energy-saving and range-extending effects. To quantitatively evaluate the impact of wing lift on system performance, a parametric sensitivity analysis was conducted by adjusting the lift loss coefficient by ±10% and ±20%, with the results shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Simulation results showing the variation characteristics of total aircraft power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different lift loss coefficient.

The analysis shows that an increase in the lift loss coefficient (i.e., a degradation in wing lift performance) elevates the energy consumption curve of the D-RE flight condition, while a decrease lowers it. Specifically, if the lift loss coefficient is reduced by 10%, the speed of equal energy consumption between the D-RE and Baseline MR conditions advances to approximately 11.5 m/s, and the energy reduction at 20 m/s expands to 23.93%. If the lift loss coefficient is reduced by 20%, this equal-consumption speed further advances to about 9 m/s, and the energy reduction at 20 m/s can reach 27.80%.

These findings indicate that reducing the flow interference from the rotors and surrounding structures on the wing can significantly enhance the device’s energy-saving benefit. A specific measure implemented in this work is the incorporation of a dihedral angle for the first wing segment, the detailed effects of which will be discussed in the next section. Furthermore, comparing the effects of drag coefficient and lift loss coefficient optimization reveals that wing lift performance is more critical for influencing the energy consumption balance point at low speeds, while drag reduction plays a more pronounced role in enhancing energy savings at high speeds.

5.2.3. Energy Consumption Analysis Under Different Task Profiles

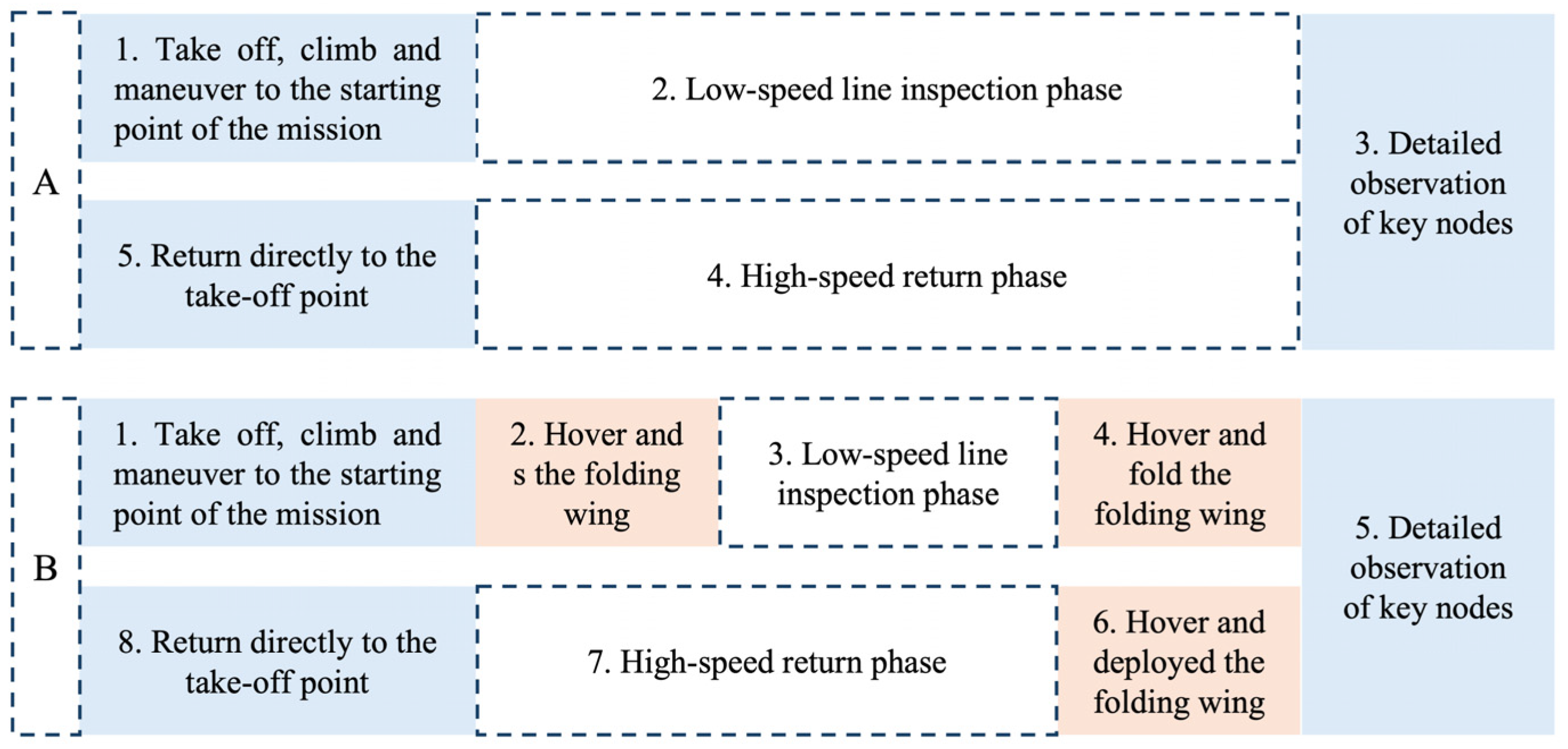

Based on the energy consumption analysis under steady-state cruise conditions, in order to further evaluate the energy consumption benefits and range-extending effects of the range-extending device in actual inspection tasks, this section takes the inspection of typical transmission lines and the exploration of key nodes as the task background and constructs the aircraft mission process as shown in Figure 20. Among them, A corresponds to the process of the Baseline MR Flight state aircraft performing tasks, and B corresponds to the task process of the D-RE flight state aircraft.

Figure 20.

Mission flowcharts corresponding to different flight conditions.

In Flow A, the stages are sequentially as follows: 1. The aircraft takes off near the mission starting point, climbs, and maneuvers to the mission start; 2. Performs line inspection at a typical cruise speed of approximately 12 m/s; 3. Conducts detailed inspection of key points such as pylons and substations; 4. Returns to base at a high speed of about 20 m/s upon mission completion and finally lands at the takeoff point. Flow B builds upon Flow A by incorporating additional stages for wing deployment and retraction.

For quantitative comparison, the aircraft was equipped with a standardized battery with a nominal capacity , voltage , and total energy . Assuming the energy consumed in each stage is , and under the condition of full battery utilization (depletion), the system satisfies energy conservation:

Based on this, the endurance enhancement effect of the range extender was objectively evaluated by calculating the maximum achievable mission radius (i.e., mission range) for each profile. The Baseline MR flight condition executes the mission according to Flow A, with parameters such as stage duration, flight speed, power consumption, distance covered, and energy consumption summarized in Table 5. The D-RE flight condition executes the mission according to Flow B, with its relevant parameters summarized in Table 6 Evaluations were performed for both the installation of the non-lightweighted extender and the theoretically lightweighted extender (approximately 100 g weight reduction).

Table 5.

Parameters for each stage of Mission Flow A.

Table 6.

Parameters for each stage of Mission Flow B.

Data analysis reveals that the energy consumption during the wing deployment and retraction stages of the Folding-Wing Range Extender constitutes a relatively low proportion of the total energy consumption, and this proportion is not highly sensitive to changes in the device’s mass. Specifically, the energy share for the non-lightweighted device is about 2.57%, and for the lightweighted device about 2.44%. Therefore, the energy cost of the deployment/retraction process does not significantly compromise the range-extending effectiveness of the device. Further reducing the device mass and moderately increasing the wing deployment speed in subsequent iterations could potentially lower the energy loss associated with this process.

Within the described mission profile, equipping the non-lightweighted Folding-Wing Range Extender increased the mission radius by approximately 4%, which is a relatively limited improvement. This is primarily because conventional small multi-rotor UAVs typically maintain a cruise speed around 12 m/s during power line inspection tasks. At this speed, the device cannot fully realize its range-extension potential, while the added weight leads to increased energy consumption for the aircraft. In contrast, installing the theoretically lightweighted Folding-Wing Range Extender increased the mission radius by approximately 27%, which fully demonstrates the significant benefits achievable through practical lightweight design of the device.

6. CFD Results and Analysis

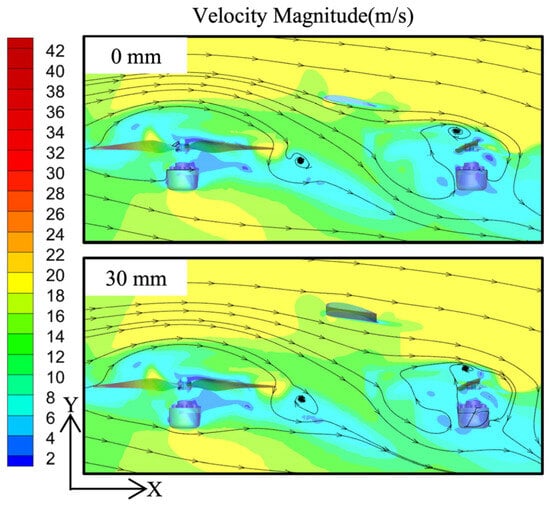

6.1. The Influence of the Dihedral Angle on the Wing on the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Wing and Rotor

To mitigate the aerodynamic interference between the wing and the rotors, the Folding-Wing Range Extender incorporates a dihedral angle in its first wing segment to elevate the wing surface and increase the vertical separation distance. This section presents a systematic analysis of the effect of varying the vertical distance (from 0 to 40 mm) between the tip and root of the first wing segment on rotor performance, wing characteristics, and the overall flow field. The analysis was conducted under a constant rotor speed of 4000 rpm and an oncoming flow velocity of 15 m/s.

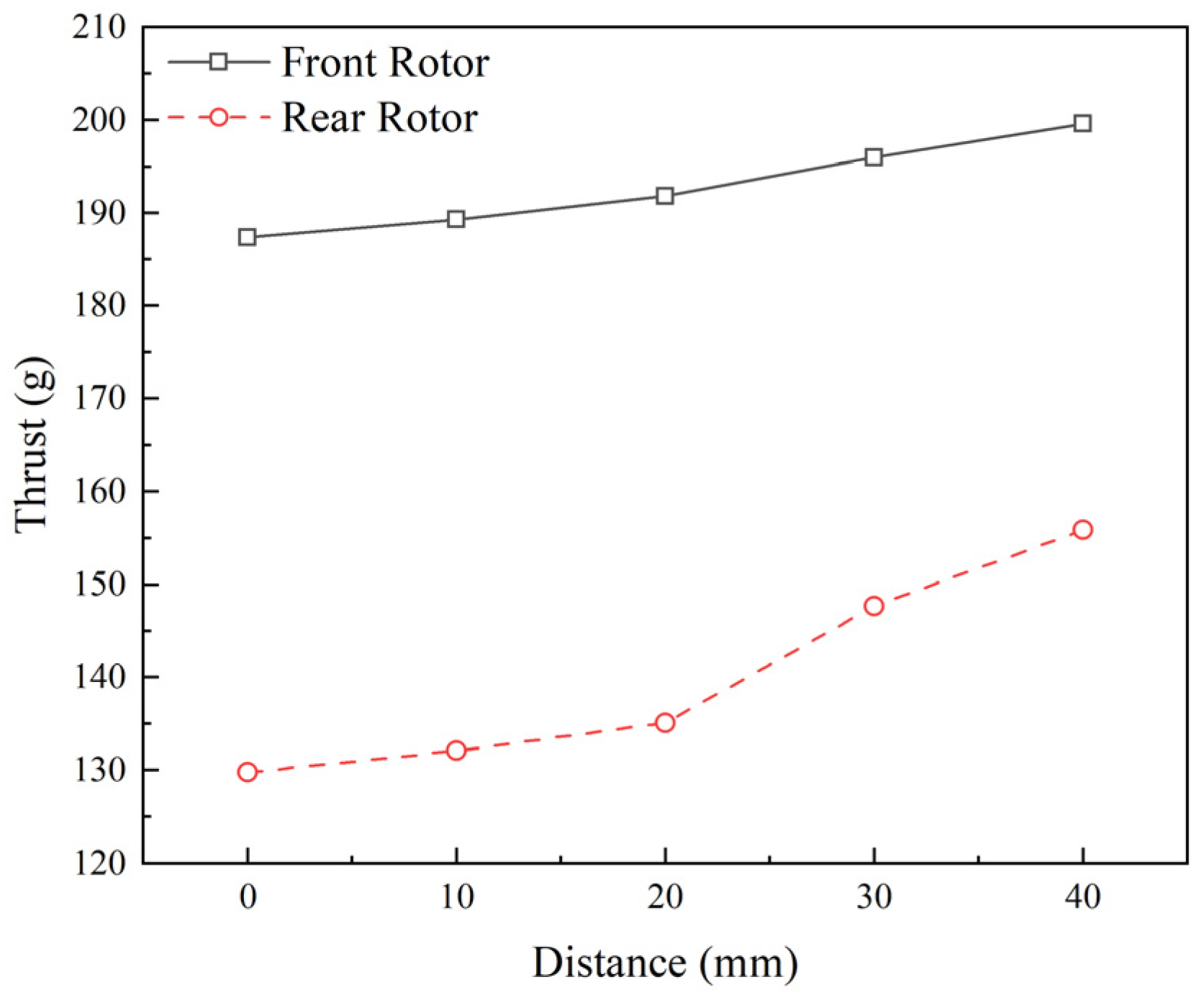

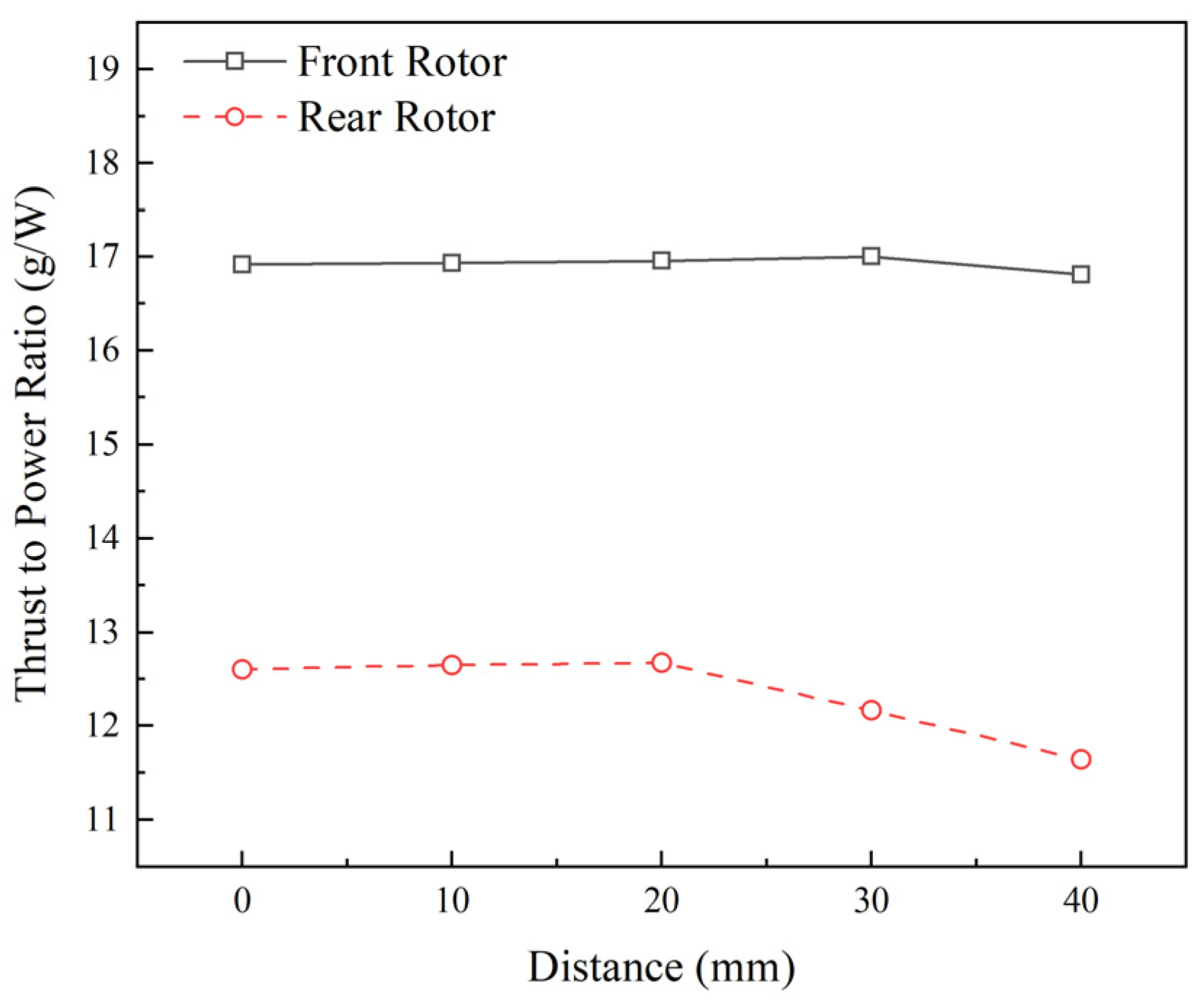

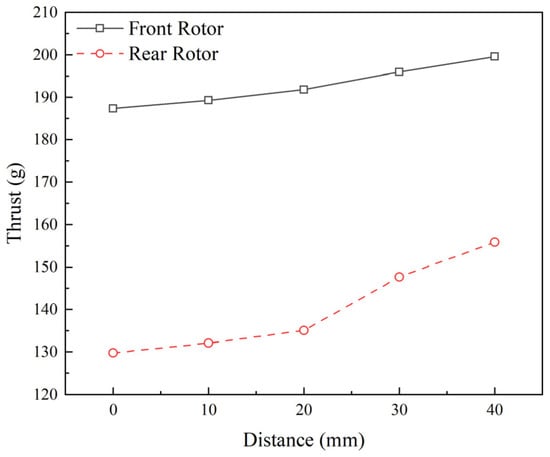

The aerodynamic performance of the rotors directly reflects the intensity of wing interference. As shown in Figure 21, when the vertical distance between the rotors and the wing increases from 0 mm to 30 mm, the thrust of the front rotor increases from 187.37 g to 195.95 g, and the thrust of the rear rotor increases from 129.78 g to 147.64 g, indicating a significant reduction in interference. Concurrently, the variation in the rotor thrust-to-power ratio is relatively moderate (Figure 22). At a smaller distance (0 mm), the wing causes blockage and disturbance to the rotor flow field, suppressing thrust output. As the distance increases, the flow field coupling weakens, allowing the rotor flow to develop in a manner more akin to its isolated state, thereby recovering thrust.

Figure 21.

Variation of front and rear rotor thrust with the vertical distance between the tip and root of the first wing segment (4000 rpm, 15 m/s oncoming flow).

Figure 22.

Variation of rotor thrust-to-power ratio with the vertical distance between the tip and root of the first wing segment (4000 rpm, 15 m/s oncoming flow).

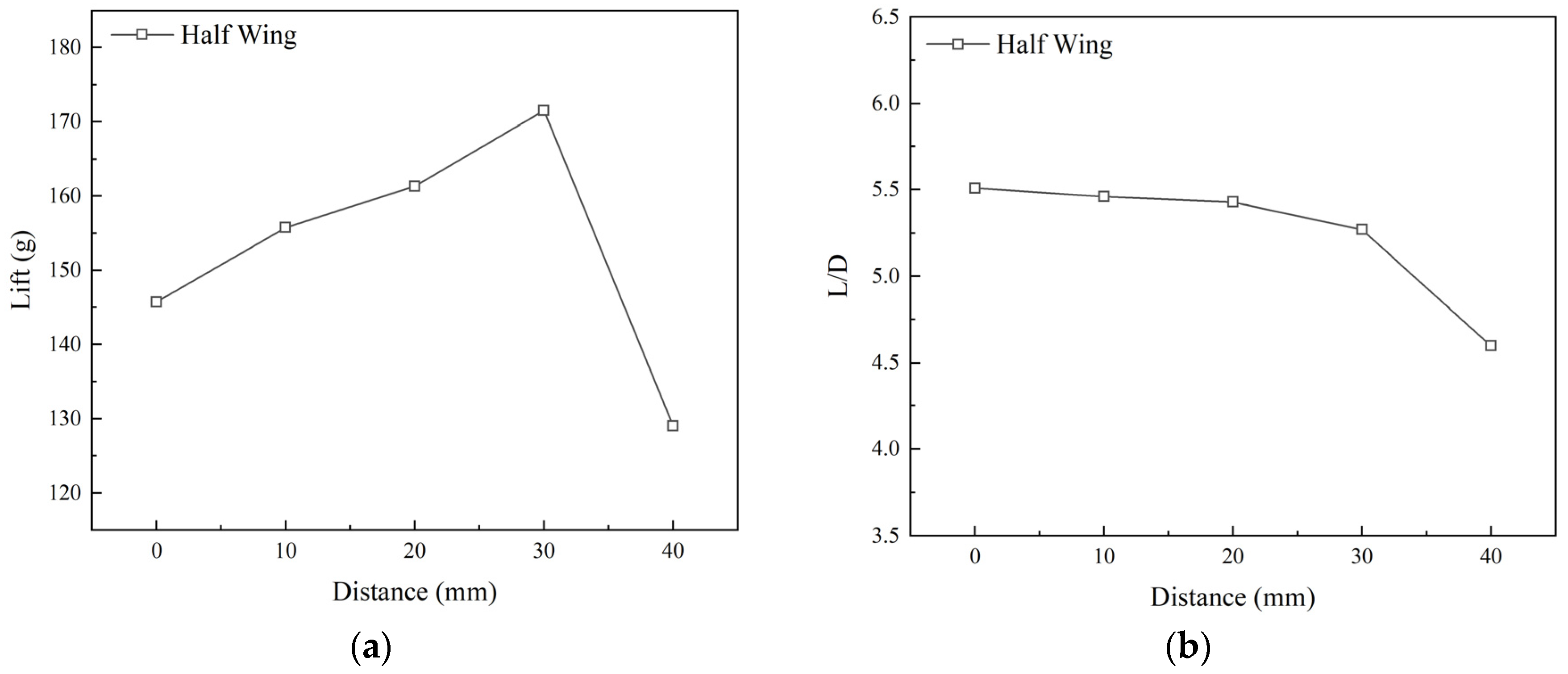

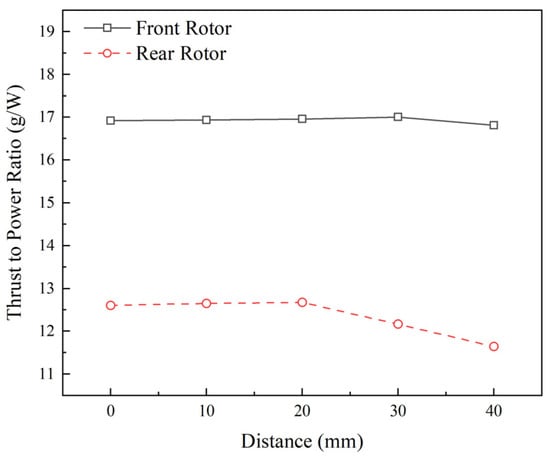

The lift and lift-to-drag ratio of the wing exhibit non-monotonic characteristics with variations in the vertical distance (Figure 23). Typically, a dihedral angle reduces the wing’s effective projected area, leading to a theoretical decrease in lift. However, within the 0 to 30 mm range, the wing lift continuously increased from 182.21 g to 214.43 g. This is because, in this phase, the aerodynamic benefit from reduced interference dominates the performance change. At a distance of 0 mm, the downward velocity component induced by the rotor decreases the wing’s effective angle of attack and disrupts the boundary layer, causing significant aerodynamic losses. As the distance increases to 30 mm, the wing surface gradually moves out of the strong interference zone, improving inflow quality and enhancing aerodynamic performance. When the distance is further increased to 40 mm, the wing gradually moves beyond the favorable region of the rotor flow field. The loss in projected area due to the dihedral angle then becomes the dominant factor, causing the lift to drop to 161.24 g and the lift-to-drag ratio to decrease from 5.51 to 4.60. This indicates the existence of an optimal distance range that maximizes overall aerodynamic benefit.

Figure 23.

Effect of the vertical distance between the tip and root of the first wing segment on the aerodynamic characteristics of the wing at 15 m/s inflow velocity and 4000 rpm rotor speed: (a) Lift; (b) Lift-to-drag ratio.

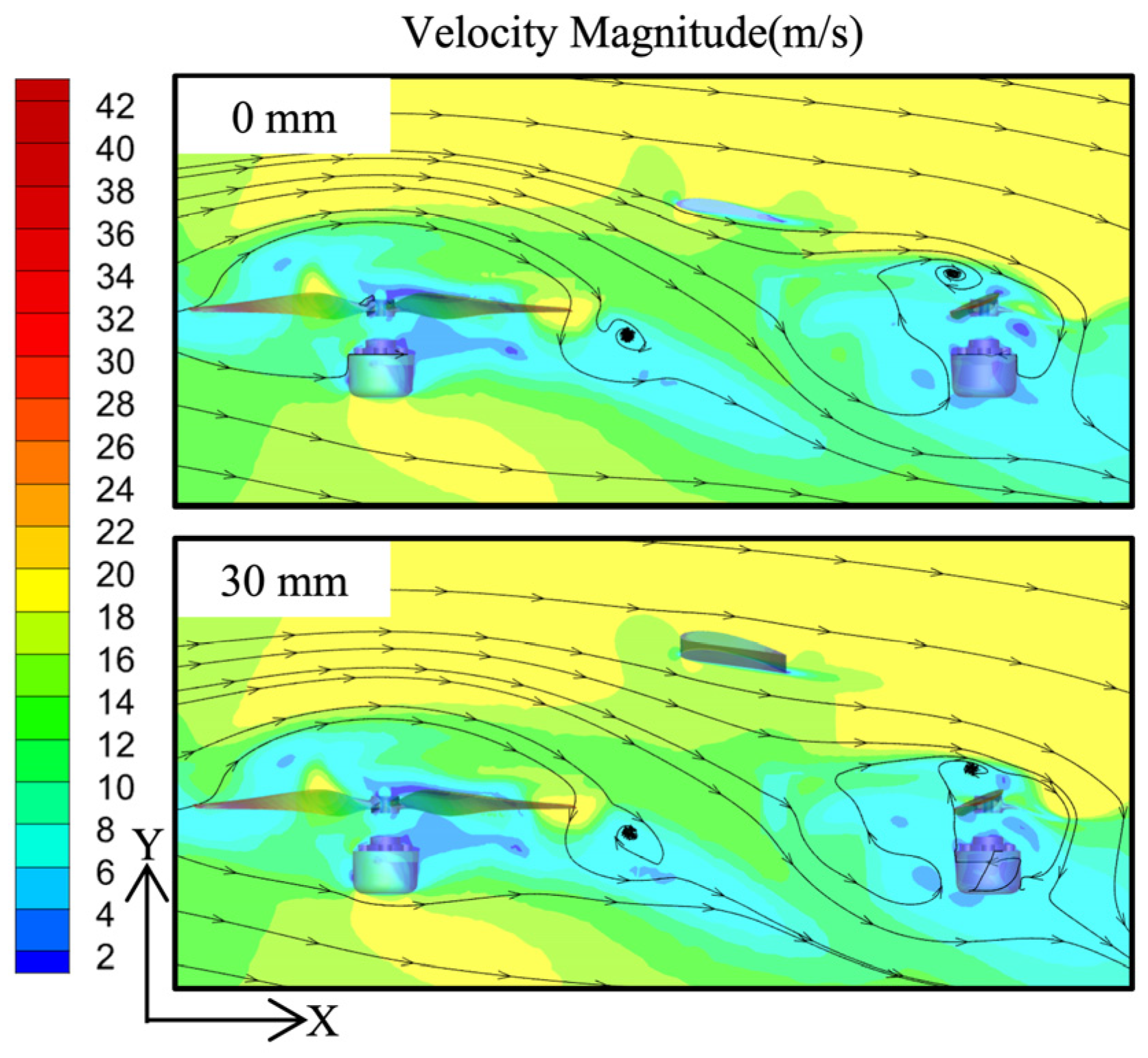

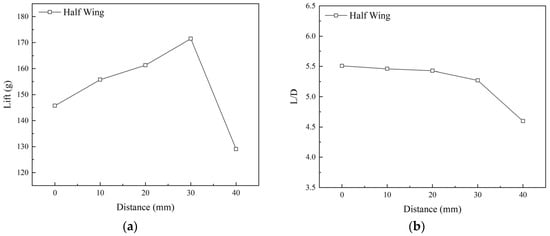

Flow field velocity contours are presented in Figure 24, visually revealing the flow mechanism of the interference between the wing and the rotor. At a distance of 0 mm, the streamlines between the rotor and the wing are interlaced and disordered, with a slightly lower flow velocity in the wing region. At a distance of 30 mm, the separation between the streamlines of the rotor and the wing is significantly enhanced, accompanied by synchronized improvements in flow uniformity and velocity levels. This phenomenon directly corroborates that the segmented dihedral configuration effectively weakens the aerodynamic coupling interference between the rotor and the wing by increasing their vertical separation.

Figure 24.

Flow field velocity contours illustrating rotor-wing interaction at different vertical distances (0 mm and 30 mm) for the first wing segment (15 m/s inflow, 4000 rpm).

6.2. The Aerodynamic Interference Situation Between the Rotor and the Propeller

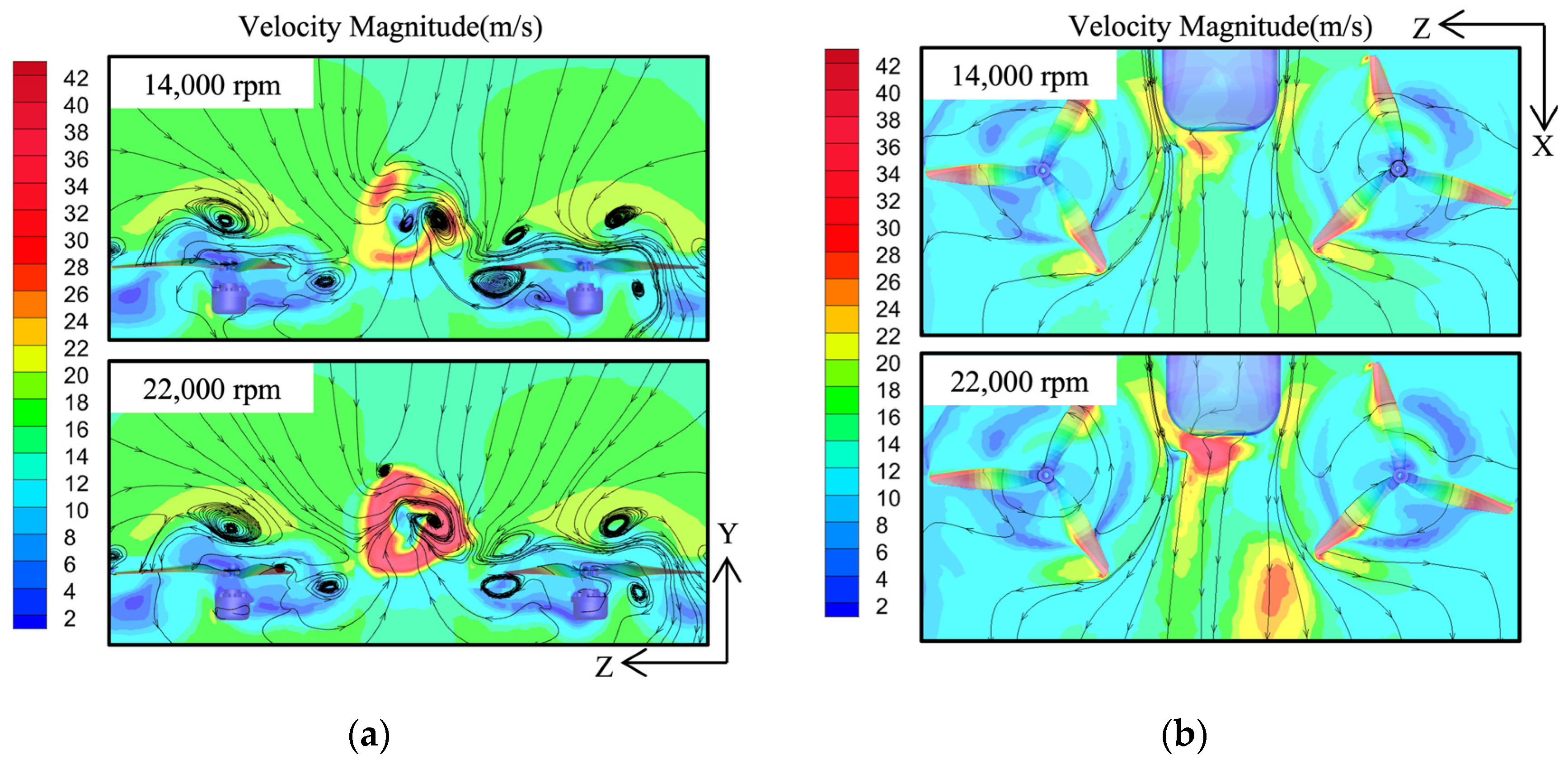

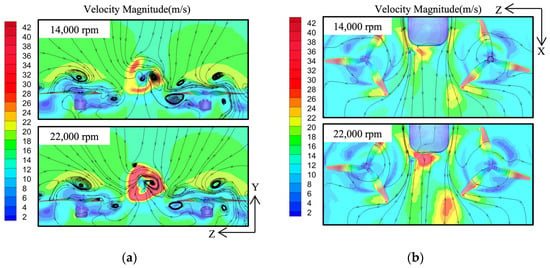

The tail-thrust propeller, mounted above and between the two rear rotors, generates a high-speed jet that interacts with the downstream rotor flow. To assess this effect, simulations were conducted with the propeller speed varying from 14,000 to 22,000 rpm, while the rotors operated at a constant 4000 rpm in a 15 m/s freestream.

Figure 25 shows velocity contours and streamlines in the Y–Z and X–Z planes behind the UAV at propeller speeds of 14,000 rpm and 22,000 rpm. At 14,000 rpm, vortex structures form in the jet wake, with flow differences already visible between the left and right rotors. Increasing the speed to 22,000 rpm enlarges the high-speed jet region and amplifies the flow asymmetry. The left and right rotors exhibit distinct flow patterns, confirming that the jet influences each side differently.

Figure 25.

Velocity contours and streamline distributions in the aft section of the UAV under different tail-thrust propeller speeds (14,000 rpm and 22,000 rpm) with 15 m/s oncoming flow and 4000 rpm rotor speed: (a) Y–Z plane; (b) X–Z plane.

7. Experimental Study on Forward Flight Power of Aircraft

7.1. Experimental Scheme and Platform

To further validate the performance improvement of the Folding-Wing Range Extender for small multirotor UAVs, this paper designed and fabricated a host quadrotor test platform and its matching Folding-Wing Range Extender prototype. Flight tests were conducted with this platform and prototype under different flight conditions to establish the correlation between forward flight speed (8 to 20 m/s) and the aircraft’s power consumption, and to evaluate the endurance, range, and flight efficiency.

To ensure accurate data acquisition, the designed and fabricated host quadrotor test platform integrates an airspeed sensor for real-time measurement of the airspeed during level-attitude forward flight when equipped with the FWRE. It is equipped with a power module and electronic speed controllers capable of precise voltage and current monitoring, enabling accurate recording of the total aircraft power and the rotor system power (calculated as the product of voltage and current). Furthermore, the platform provides dedicated electrical interfaces for the tail-thrust motor and the folding mechanism of the FWRE, facilitating its flexible and rapid integration. Furthermore, on the control level, this study utilized the open-source Ardupilot flight control platform. Through a series of empirical parameter tunings—primarily including increasing the damping in the attitude control loop and relaxing controller output limits—the robustness of the flight control system was enhanced to accommodate the added range-extension module and to cope with the aerodynamic parameter variations and disturbances introduced by wing deployment. Flight test results demonstrated that the system maintained satisfactory flight stability under these conditions. The core components and key design parameters of the host quadrotor test platform are detailed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Parameters of the Host Quadrotor Test Platform.

Based on the parameter constraints of the aforementioned host quadrotor test platform, a matching prototype of the FWRE was designed and fabricated. This prototype can be rapidly connected to the host quadrotor via bolts, and its structural components snugly conform to the airframe, thereby effectively reducing aerodynamic drag during flight. Notably, this height increment poses almost no operational constraints during typical long-range missions. The core components and key parameters of the FWRE prototype are detailed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Parameters of the Folding-Wing Range Extender.

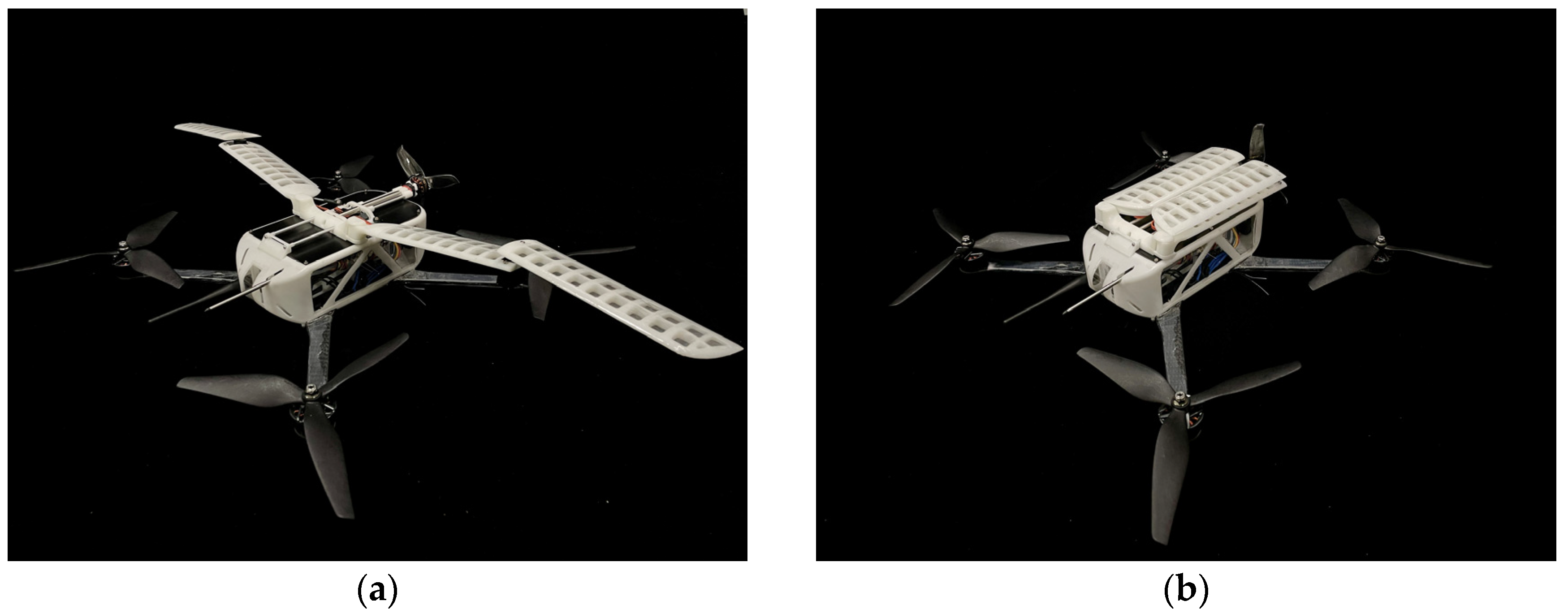

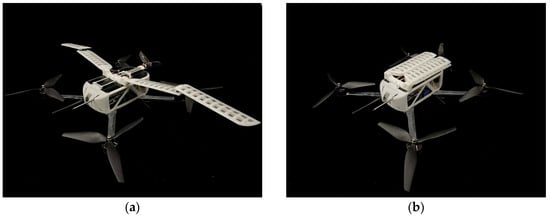

The physical integration of the host quadrotor test platform with the FWRE is shown in Figure 26, where (a) depicts the device in the deployed state and (b) shows the folded configuration. The structural components and wings of the FWRE were manufactured using stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing technology. The wings feature a hollow internal structure to reduce weight while maintaining their aerodynamic profile through an external skin covering.

Figure 26.

Physical prototype of the UAV equipped with the Folding-Wing Range Extender: (a) Deployed state; (b) Folded state.

Based on the aforementioned host quadrotor test platform and its matching FWRE, flight tests were systematically conducted to quantitatively validate the performance improvement achieved by the device. The flight test design was guided by both experimental rationality and practical mission requirements. On one hand, the additional mass of the FWRE increases the power consumption of the host quadrotor’s rotors. This factor could interfere with the accurate assessment of the device’s maximum range-extension potential. Therefore, the test must be designed to isolate this effect, thereby directly reflecting the device’s inherent performance and the potential performance gains achievable through weight reduction in engineering applications. On the other hand, considering real-world operational scenarios, a small quadrotor equipped with the extender might need to fold its wings mid-flight during a long-range cruise mission to inspect key points, thus regaining and utilizing the host UAV’s inherent high maneuverability for close-range observation. Based on these two core requirements, two additional flight conditions were incorporated into the comparative tests, supplementing the three conditions used in the earlier simulations:

Ballast-Loaded Multirotor flight condition, abbreviated Ballast MR: The host quadrotor test platform carries a ballast mass equivalent to the weight of the FWRE (ensuring minimal change in the center of gravity after loading) and flies in traditional multirotor mode, thereby isolating the additional mass effect;

Folded Range-Extension (Multirotor Mode) flight condition, abbreviated F-RE (MR Mode): The host quadrotor test platform equipped the FWRE in its folded state and operates in traditional multirotor mode, serving to evaluate the performance impact of the FWRE’s additional mass and aerodynamic interference on the host UAV.

In summary, for all five flight conditions in the experiment, the flight strategy involved performing at least three back-and-forth cycles along the same linear route at a constant altitude, resulting in six stable flight legs. This approach provided a robust basis for subsequently eliminating interference factors such as wind speed and direction during data processing, thereby obtaining accurate measurements. During the tests, utilizing the hardware system of the host quadrotor test platform and the FWRE, full-parameter real-time monitoring and recording were implemented via the Mission Planner (1.3.82) ground control station software. For flight conditions where the tail-thrust propeller was active, both the rotor system power and the total aircraft power were quantitatively recorded. For other conditions where the tail-thrust propeller was inactive, only the total aircraft power was recorded. Considering that the avionics system power consumption is relatively small, essentially constant, and significantly lower than the power consumption of the rotors and propeller, it can be reasonably approximated that: when the propeller is inactive, the total aircraft power equals the rotor system power; when the propeller is active, its power can be calculated as the difference between the total aircraft power and the rotor system power. A real-flight scenario under the D-RE flight condition is shown in Figure 27. All flight tests were conducted with the battery’s initial State of Charge (SOC) within the range of 95% to 100% to eliminate the influence of initial capacity variation on performance evaluation. Prior to flight, all sensors were calibrated following the standard procedure.

Figure 27.

Actual flight scenario under the D-RE flight condition.

7.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

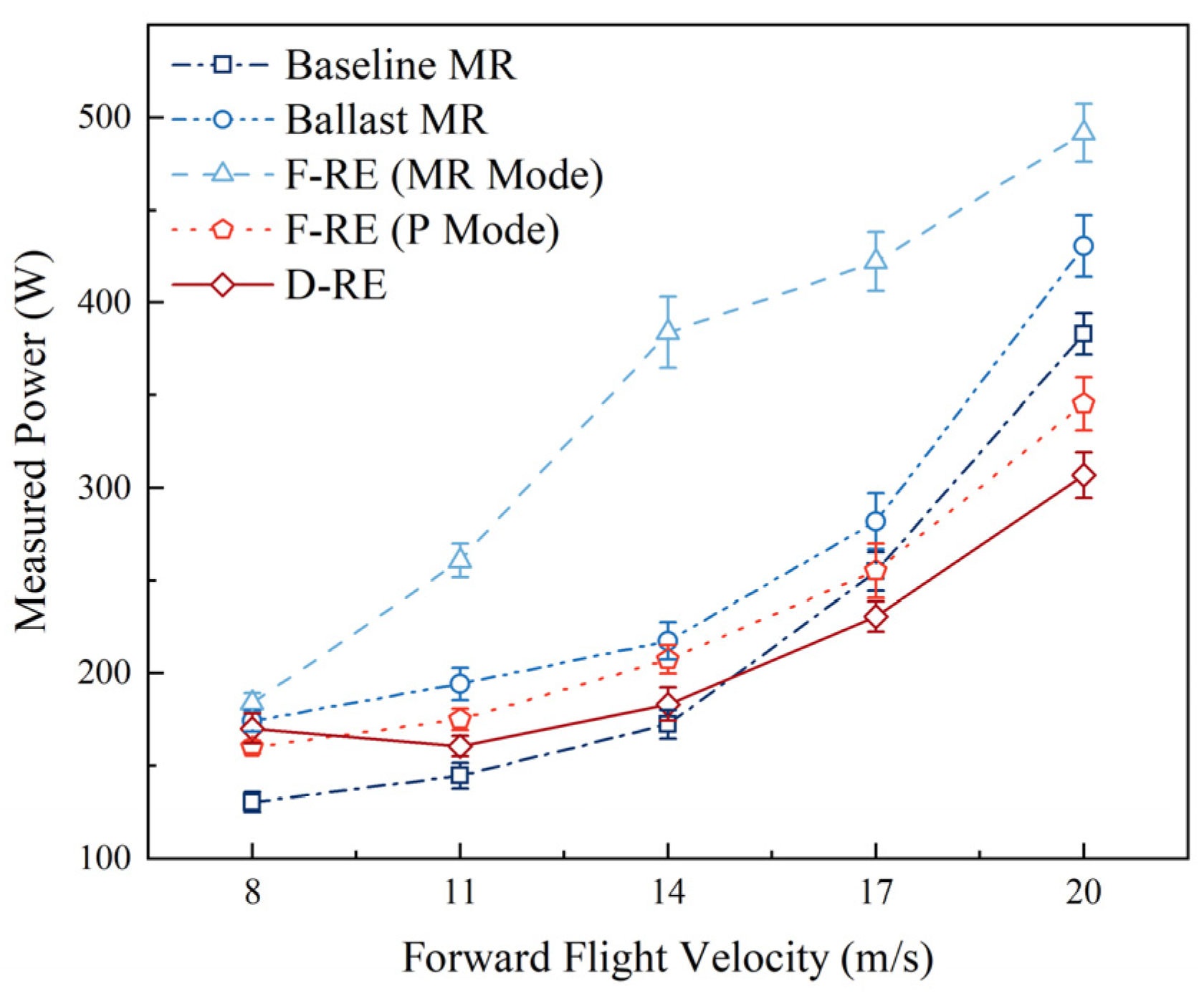

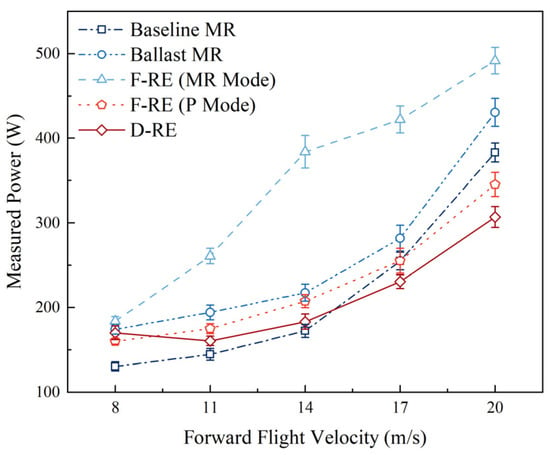

Figure 28 presents the experimental results, with error bars representing the standard deviation, for the total power consumption of the aircraft under different flight conditions across the forward speed range of 8 to 20 m/s. It can be observed from the figure that, except for the D-RE flight condition which exhibits a slight decrease in power consumption at forward speeds below 11 m/s, the total power for all other configurations increases with speed, and the rate of increase accelerates. It is noteworthy that within the forward speed range of 11 to 17 m/s, the power increase rate of the F-RE (MR Mode) flight condition exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing. This is attributed to the varying levels of aerodynamic interference caused by the installed extender on the host UAV at different forward speeds (corresponding pitch angles). Therefore, high-speed flight in this specific condition should be minimized whenever possible.

Figure 28.

Experimental results showing the variation characteristics in total aircraft power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different flight conditions.

It was observed during testing that as the forward speed increased, the wing lift rose accordingly, while the rotor speed decreased further, leading to a degradation in attitude control capability and a tendency towards instability. Nevertheless, the currently validated speed range of up to 20 m/s fully covers the typical operating conditions for such missions.

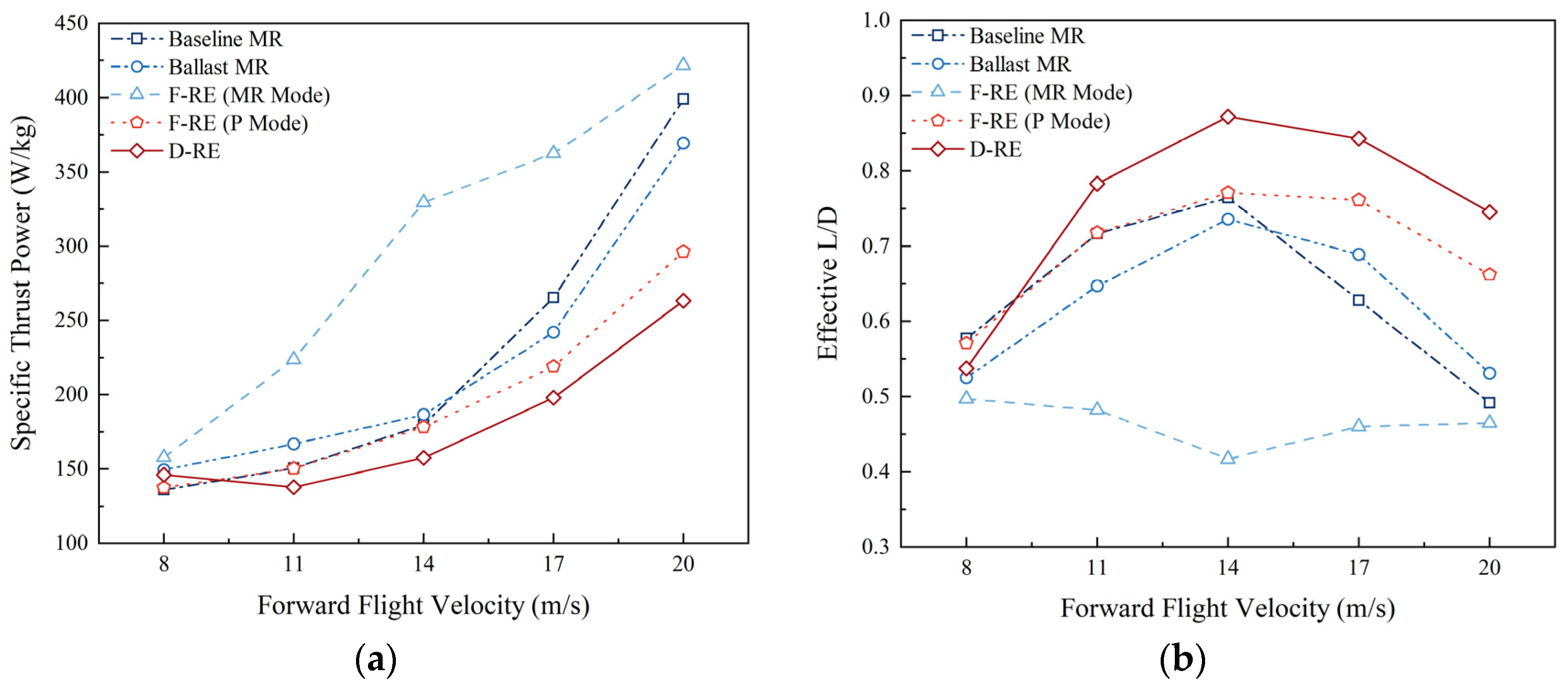

A comparison between the Baseline MR and D-RE flight conditions reveals the change in energy consumption of the small multirotor UAV after installing the FWRE. When the forward speed is below 15 m/s, the additional mass and aerodynamic drag of the extender result in approximately 10% to 30% higher power consumption for the latter configuration. When the forward speed reaches approximately 15 m/s, the power consumption of the two flight conditions becomes comparable. As the speed increases further, the power advantage of the D-RE flight condition continues to grow, achieving approximately 20% (95% CI: [16.03%, 23.79%]) lower power consumption at a forward speed of 20 m/s. Within the tested forward speed range, the power of the Baseline MR flight condition increased by 194%, primarily due to the surged aerodynamic drag. In contrast, the power of the D-RE flight condition, equipped with the FWRE, increased by only 80%, owing to the dual energy-saving mechanisms of oncoming horizontal airflow and wing lift unloading, thereby confirming the device’s effectiveness.

The comparison between the Ballast MR and D-RE flight conditions, which eliminates the variable of the FWRE’s mass, reveals that the Ballast MR condition exhibits higher power consumption across the entire speed range due to the added mass. This confirms that weight reduction can significantly enhance the device’s effectiveness. At 20 m/s forward speed, the D-RE condition achieves a 30% reduction in power consumption, highlighting the engineering potential of systematic lightweight design. Although the ballast condition alters the vehicle’s moment of inertia, the required pitch angle to maintain the same cruise speed differs only minimally (by approximately ) from that of the Baseline MR flight conditions. This demonstrates that the design effectively isolates the effect of added mass on baseline power consumption, thereby validating its use for comparison with the D-RE flight conditions.

The difference between the D-RE and F-RE (P Mode) flight conditions quantifies the benefit of wing unloading. Experimental data indicate that at forward speeds below 9 m/s, the reduction in rotor power due to wing unloading is relatively small, while the increased drag from the deployed wings results in a higher rotational speed of the tail-thrust propeller at the same airspeed, leading to a significant power increment. Consequently, the D-RE flight condition exhibits slightly higher power consumption, approximately 6% higher at 8 m/s. However, as the forward speed increases, the wing unloading effect becomes increasingly dominant, resulting in approximately 11% lower power consumption at 20 m/s.

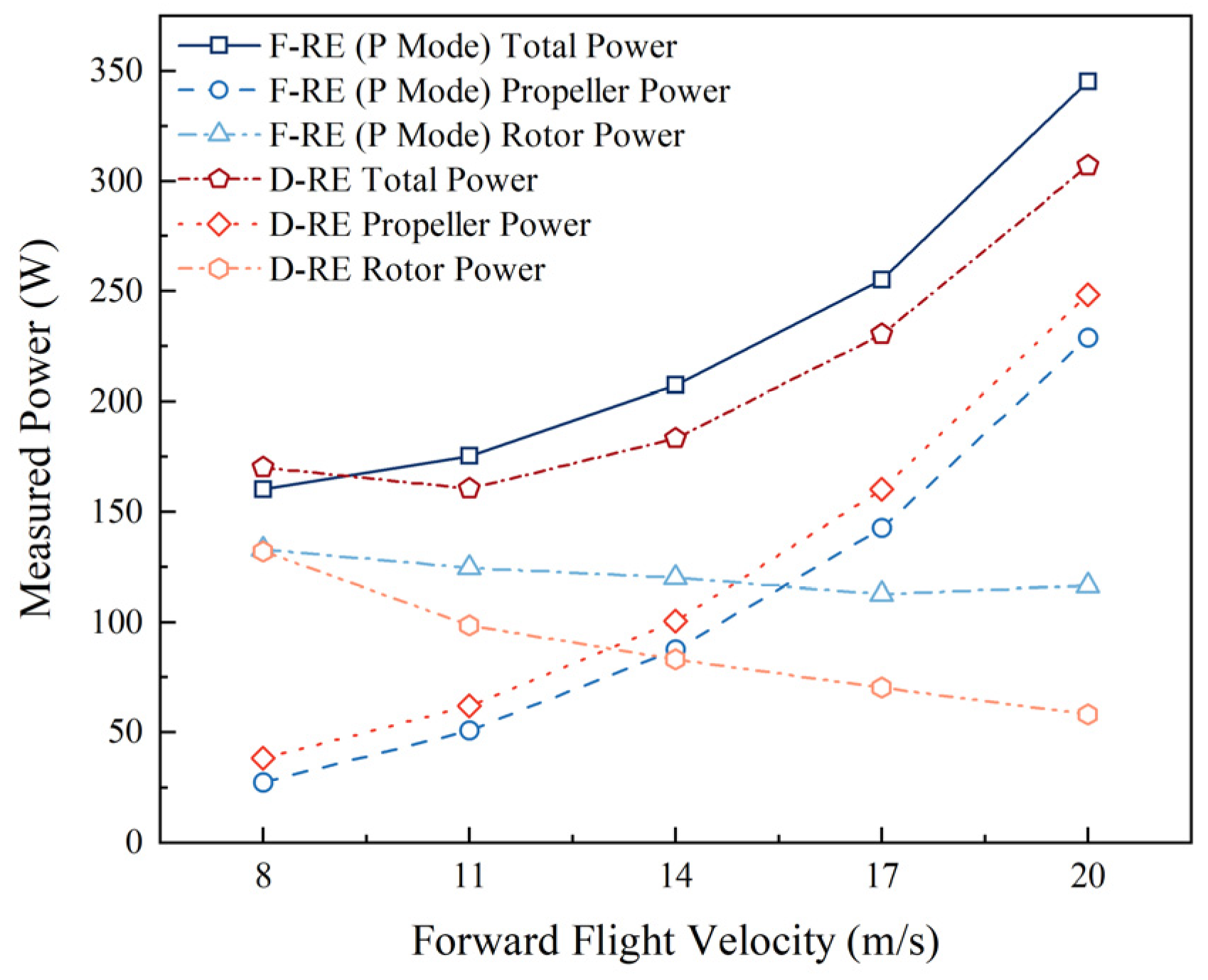

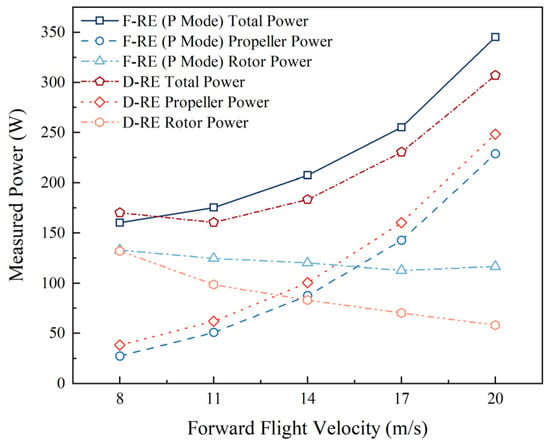

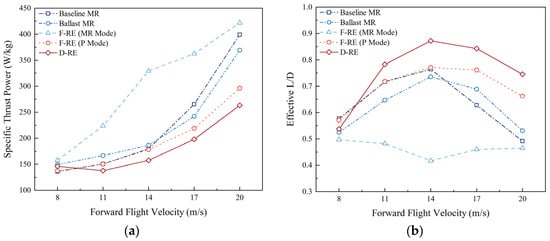

Figure 29 further presents the experimental results of the total power, rotor power, and tail-thrust propeller power for the F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions across the forward speed range of 8 to 20 m/s after installing the FWRE, revealing the influence mechanisms of oncoming horizontal airflow and wing unloading on energy distribution. The trends align with the simulation results. Experimental data show that at 20 m/s forward speed, the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition achieves a 12% reduction in rotor power, which plateaus after the speed exceeds 17 m/s. In contrast, the D-RE flight condition, benefiting from the wing unloading effect, attains a 56% reduction in rotor power. Meanwhile, the tail-thrust propeller power increases by 552% in the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition, while that of the D-RE flight condition increases by 742% due to the higher drag from the deployed wings.

Figure 29.

Experimental results showing the variation and distribution characteristics of total aircraft power, rotor power, and propeller power with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions.

Furthermore, a comparison of the rotor power consumption between the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition at different forward speeds and the hover condition validates the optimization mechanism of the oncoming horizontal airflow on rotor power consumption. The experimental data demonstrate that as the forward speed increases, the rotor’s thrust-generating capability is enhanced, resulting in a decrease in power consumption, a trend consistent with theoretical analysis and simulation results. At a forward speed of 20 m/s, the rotor power consumption is reduced by approximately 35% compared to the hover state.

The preceding sections have, through both simulation and experiment, clearly established the power consumption patterns of the aircraft under different flight conditions across various forward speeds. To further comprehensively evaluate the practical effectiveness of the FWRE, the following analysis integrates parameters such as the vehicle’s energy reserve and flight speed to perform quantitative calculations and assessment of the endurance, range, and energy efficiency. This approach aims to systematically verify the overall performance improvement achieved by the device.

Endurance and range are critical performance metrics for the aircraft, primarily determined by its onboard battery capacity and the power consumption during cruise. The endurance is calculated by the following formula:

where is the endurance, is the battery capacity (here, for the carried battery), and is the average current during cruise. Based on this, the range of the aircraft can be expressed as the product of cruise speed and endurance:

where is the aircraft range, and is the forward airspeed during stable cruise.

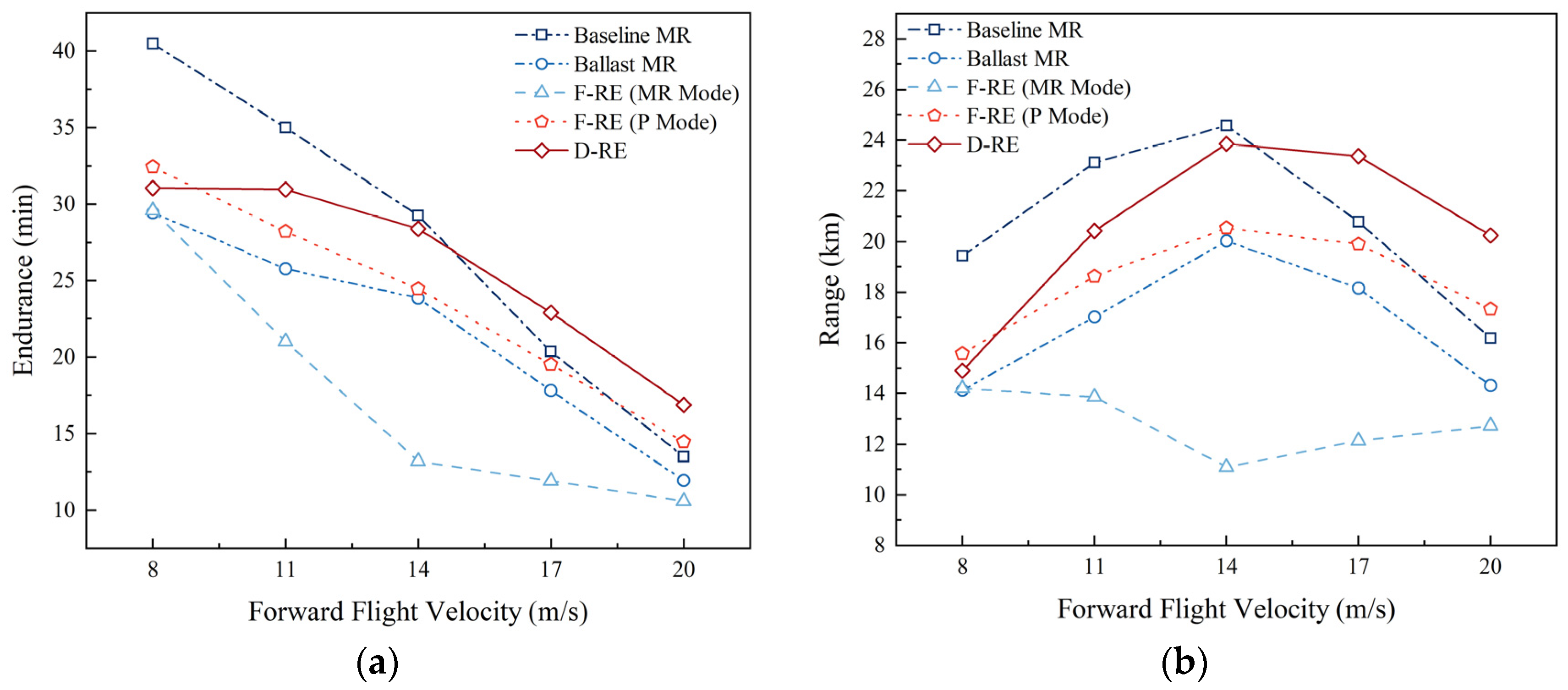

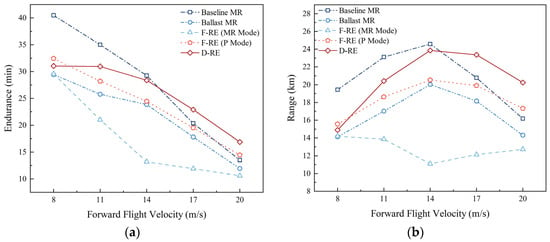

Figure 30 presents the experimental results of the endurance and range variations with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different flight conditions. As shown in Figure 30a, within the tested speed range, except for the D-RE flight condition which exhibits a slight increase in endurance at forward speeds below 11 m/s, the endurance of all other conditions decreases monotonically with increasing airspeed. This is primarily attributed to the significant increase in flight power consumption. in contrast, the range data in Figure 30b exhibits a pronounced nonlinear variation, a pattern resulting from the coupling effect between forward speed and endurance. Furthermore, the gap in range and endurance between the F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions and the Baseline MR condition gradually narrows with increasing speed, eventually being completely surpassed, highlighting the high-speed advantage of the proposed extender.

Figure 30.

Experimental results showing the variation in aircraft endurance and range with increasing forward speed (8 to 20 m/s) under different flight conditions: (a) Endurance; (b) Range.

A further analysis of the data in Figure 30 reveals that both the F-RE (P Mode) and D-RE flight conditions exhibit longer endurance and range across the entire speed spectrum compared to the Ballast MR condition, further demonstrating the necessity of the weight reduction design in practical applications. When the forward speed reaches 14 m/s, all flight conditions except the F-RE (MR Mode) reach their maximum range. At this speed, compared to the Ballast MR condition, the F-RE (P Mode) achieves an approximately 3% increase in range, while the D-RE condition achieves an approximately 19% increase, highlighting the significant performance gain from the wing deployment.

Furthermore, after installing the range extender, the D-RE flight condition exhibits lower range and endurance compared to the Baseline MR flight condition at low speeds. This is due to the combined effects of the device’s additional mass and increased aerodynamic drag, while the benefits of rotor aerodynamic optimization and wing unloading are not yet fully realized in this speed regime; as the forward speed increases, the aerodynamic benefits become progressively more pronounced. When the speed reaches 15 m/s, the range and endurance of the D-RE flight condition become comparable to those of the Baseline MR flight condition. At 20 m/s, the D-RE flight condition achieves approximately 25% improvement in both range and endurance. In contrast, the F-RE (P Mode) flight condition, which retains only the benefit of oncoming horizontal airflow optimization, sees its performance turning point delayed until approximately 18 m/s. Furthermore, its range improvement is limited to about 7%, thereby validating the critical contribution of wing unloading to both range and endurance.