Highlights

What are the main fundings?

- A novel cross-view matching and localization (CVML) framework aligns UGV images with UAV-stitched maps in GNSS-denied environments.

- The proposed VSCM-Net introduces two attention modules—the VLM-guided positional correction module and the shape-aware attention module—to preserve semantic and topological consistency across aerial and ground views, and the UGV-UAV matching is conducted accordingly.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The method enables accurate and robust localization of UGVs on UAV-stitched maps, achieving reliable trajectory estimation and navigation without GPS, which offers significant advantages for applications such as disaster response and emergency rescue.

Abstract

In Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)-denied urban environments, unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) face significant difficulties in maintaining reliable localization due to occlusion and structural complexity. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), with their global perspective, provide complementary information for cross-view matching and localization of UGVs. However, robust cross-view matching and localization are hindered by geometric distortions, semantic inconsistencies, and the lack of stable spatial anchors, limiting the effectiveness of conventional methods. To overcome these challenges, we proposed a cross-view matching and localization (CVML) framework that contains two components. The first component is the Vision-Language Model (VLM)-guided and spatially consistent cross-view matching network (VSCM-Net), which integrates two novel attention modules. One is the VLM-guided positional correction module that leverages semantic cues to refine the projected UGV image within the UAV map, and the other is the shape-aware attention module that enforces topological consistency across ground and aerial views. The second component is a ground-to-aerial mapping module that projects cross-view correspondences from the UGV image onto the UAV-stitched map, thereby localizing the capture position of the UGV image and enabling accurate trajectory-level localization and navigation. Extensive experiments on public and self-collected datasets demonstrate that the proposed method achieves superior accuracy, robustness, and real-world applicability compared with state-of-the-art methods in both cross-view image matching and localization.

1. Introduction

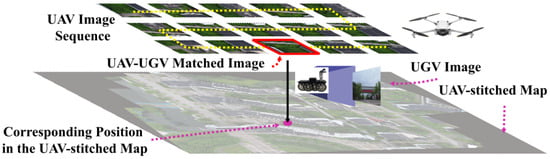

Unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) play a critical role in disaster response, performing perception, navigation, and task execution in highly complex and dynamic environments. However, achieving reliable localization remains a persistent challenge, as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals are frequently degraded or completely denied due to building occlusion, electromagnetic interference, or infrastructure damage [1]. In such environments, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), with their overhead perspective, wide-area coverage, and rapid deployment, can complement UGVs by providing global situational awareness. Specifically, by stitching UAV-captured images of disaster regions, a comprehensive representation of the target area can be constructed. Integrating this aerial perspective with the ground-level observations of UGVs enables aerial–ground collaborative localization, thereby facilitating reliable task execution in complex environments, as shown in Figure 1. This paradigm has garnered significant attention and emerged as a promising strategy for ensuring autonomy in GNSS-denied scenarios [2,3].

Figure 1.

The illustration of UGV matching and localization in the UAV-stitched map.

However, achieving robust cross-view image matching (CVIM) between UAV overhead imagery and UGV ground-level observations remains a fundamental challenge. UAV images, characterized by their consistent top-down geometry, provide a global but abstracted representation of the scene, which compresses the spatial structural features of objects. In contrast, UGV imagery is inherently local, constrained by a limited field of view, frequent occlusions, and perspective distortions introduced by complex urban structures. This geometric discrepancy is profound: objects that appear compact, spatially coherent, and topologically structured from the aerial viewpoint often become fragmented, distorted, and partially occluded at the ground level, invalidating classical homography- or Bird’s-Eye-View (BEV)-based alignment models [4,5]. Semantic inconsistency further exacerbates the difficulty, as identical objects exhibit drastic variations in scale, orientation, and visual appearance across different viewpoints [6]. These challenges underscore the limitations of conventional approaches when faced with the extreme viewpoint disparity and structural complexity inherent in UAV-UGV matching and localization.

Recent research has sought to alleviate these challenges through a variety of strategies. Geometry-driven methods provide interpretability and physically grounded reasoning, yet they typically break down under the large viewpoint disparities characteristic of cross-view localization. Date-driven alternatives, such as CNN-based retrieval and contrastive learning frameworks, have shown greater resilience to variations in texture and illumination but remain highly sensitive to domain shifts between aerial and ground perspectives [7,8]. Transformer-based models extend this line of work by introducing long-range modeling, which strengthens spatial consistency across views [9,10]. Nevertheless, the absence of explicit geometric priors often leads to degraded stability when facing severe perspective distortions. More recently, vision–language models (VLMs) have achieved remarkable progress in semantic alignment by embedding visual and textual modalities into a unified feature space [11,12,13]. Despite their semantic strength, these models largely overlook explicit spatial reasoning, thereby constraining their ability to deliver accurate localization. Additionally, current approaches are usually studied in satellite-street-view setting, where the altitude difference reaches kilometers, and the task is typically formulated as large-scale image retrieval. However, these assumptions do not hold in low-altitude UAV-UGV localization, a fundamentally different scenario where the ground robot need to be localized within a UAV-stitched map for navigation in GNSS-denied environments. In this setting, the geometric distortions between UAV and UGV views are local yet topologically complex, and the desired output is the localization trajectory rather than a one-shot image match.

To bridge this gap, we proposed a Cross-View Matching and Localization (CVML) framework tailored for UGV matching and localization in UAV-stitched maps. The framework consists of a VLM-Guided and Spatially Consistent Cross-View Matching Network (VSCM-Net) to identify the matching similarities among UGV and UAV images. VSCM-Net integrates a VLM-guided attention mechanism with Transformer-driven global alignment, reinforced by explicit spatial consistency constraints. By embedding high-level semantic cues into spatial tokens, VSCM-Net enables robust matching among UGV and UAV images. Building on the above, we further extract the precise coordinates of the UGV’s position within the UAV imagery at the moment the UGV imagery is captured. By leveraging the transformation relationships established during the UAV stitching process, the positional correspondence of UGVs can be projected into the global UAV-stitched map, thereby constructing the continuous trajectory of the UGV. The contributions of this work are given as follows:

- We propose the VSCM-Net, which incorporates a VLM-guided positional correction attention module and a shape-aware correction attention module that enforces spatial topological consistency, both built upon a Transformer architecture. These modules provide a dual-branch correction mechanism that jointly enforces semantic relationships and geometric structure.

- We propose a framework, named CVML, for UGV localization within the UVA-stitched map, built upon cross-view aerial–ground matching, which establishes a closed-loop integration between cross-view matching and UGV localization.

- We construct a low-altitude cross-view dataset comprising sequential ground imagery paired with corresponding UAV imagery, and released the dataset publicly at the link https://github.com/YoungRainy/LACV-Dataset (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- The experimental results in public and self-built datasets demonstrate that the proposed framework consistently outperforms existing methods in accuracy, robustness, and real-world applicability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on cross-view matching and localization. The details of the proposed CVML framework are introduced in Section 3. Section 4 reports and analyzes the experimental results on both public and self-built datasets. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Related Works

Cross-view matching aims to establish reliable correspondences between images captured from ground and aerial viewpoints. Generally, cross-view matching methods can be categorized into geometry-based methods and deep learning-based methods. More recently, with the rapid advancement of VLM, several studies have begun to integrate such models into the cross-view matching framework to further enhance performance.

Geometry-based approaches. Traditional methods typically leverage geometric similarities to align aerial and ground views. For instance, Wang et al. [4] introduced a correlation-aware homograph estimator that achieves sub-pixel alignment and meter-level accuracy. However, the underlying assumption of geometric consistency often breaks down in cluttered urban scenes. To address large viewpoint variations, Wang et al. [14] proposed hybrid spherical transformations, which simplify alignment but remain highly sensitive to camera pose errors. Ye et al. [5] further transformed panoramic street-view imagery into BEV representations to enable efficient retrieval, though their reliance on high-quality panoramas restricts applicability in UAV-UGV disaster scenarios. Overall, despite their interpretability, geometry-based approaches remain limited in handling occlusion, scale variations, and incomplete structural information that are inherent to UAV-UGV scenarios.

Deep learning-based approaches. Besides geometry-based approaches, a growing body of research has turned to deep learning-based cross-view strategies, which aim to learn more robust and discriminative representations for UAV-UGV matching. For example, building on contrastive learning, Deuser et al. [8] sought to improve feature discriminability through hard negative sampling; however, the method’s stability was still closely tied to sampling quality. Vyas et al. [15] incorporated temporal dynamics into cross-view matching by employing 3D convolution networks with an image-video contrastive loss, thereby extending beyond static correspondence. The VIGOR benchmark, introduced by Zhu et al. [7], was accompanied by a coarse-to-fine hierarchical matching and localization framework that markedly improved accuracy, although its effectiveness diminished in the large-scale environment. Lingyun Tian et al. [16] proposed a Mamba-based method called the Cross-Mamba interaction network for UAV geolocalization.

With the advancement of attention mechanisms, Transformers have emerged as a powerful paradigm for modeling cross-view relations. As presented by Chengjie Ju et al. [17], which introduced a lightweight value reduction pyramid transformer for efficient feature extraction and matching among UAV imagery and satellite imagery. Zhu et al. [9] introduced a Transformer-based framework that incorporated attention-guided cropping, thereby reducing computational cost while enhancing multi-source alignment. Jin et al. [10] developed BEVRender, which employs Vision Transformers with deformable attention to aggregate multi-frame features into a high-resolution BEV space, followed by template-based matching for precise localization, while this design delivered notable accuracy, it was heavily reliant on GPS priors and geometric consistency during BEV generation, thus limiting robustness in the GNSS-denied environment. Recent studies have investigated VLM to bridge the gap between aerial and ground views. Such as the AddressVLM proposed by Xu et al. [12], which outputs a predicted geographic address by aligning a street-view image with textual address descriptions using the VLM. Unlike traditional street-view and satellite-view matching, AddressVLM could determine the geographical localization of a ground-view image, such as the specific street it is on.

Overall, geometry-based, deep learning-based, and VLM-based CVIM strategies each exhibit distinct strengths and limitations, with VLM-based approaches demonstrating strong potential in capturing the spatial relationships between aerial and ground imagery. However, the majority of these methods are developed for sattlite-street-view retrieval, where the viewpoint gap spans kilometers in altitude and the objective is to retrieve a matching ground image from a large candidate set, as shown in Table 1. These assumptions differ fundamentally from the low-altitude UAV-UGV localization problem addressed in this work. To address these gaps, the proposed CVML framework is specifically designed for the low-altitude UAV-UGV domain.

Table 1.

The comparison between several classic cross-view frameworks.

3. Methodology

3.1. CVML Framework

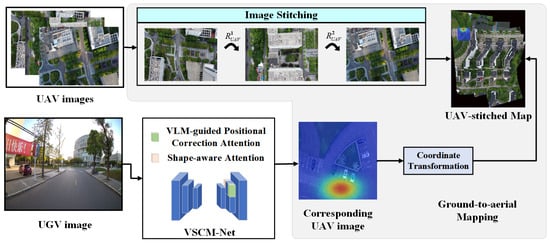

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the proposed CVML framework, which consists of two components. The first is VSCM-Net, designed to measure cross-view similarity between UGV and UAV imagery. Specifically, it identifies the UAV image that exhibits the highest similarity with the UGV observation and determines the corresponding location of maximum similarity within the UAV image. The second component, ground-to-aerial mapping, establishes the localization of the UGV within the globally stitched UAV map by leveraging both the estimated position of the UGV in the UAV image and the geometric transformation that relates the UAV image to the stitched UAV map.

Figure 2.

The structure of the proposed CVML framework, which consists of two components. One is the VSCM-Net module, that used to calculate the similarity between UGV and UAV images. The other one is the Ground-to-aerial module that is used to identify the capturing location of the UGV image in the UAV-stitched map. and represents the transformation relationship among during UAV-stitching process.

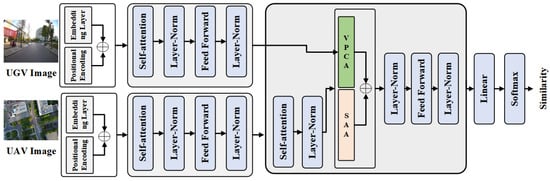

3.2. VLM-Guided and Spatially Consistent Cross-View Matching Network

The proposed VSCM-Net adopts a Transformer-based architecture composed of an encoder-decoder structure, as illustrated in Figure 3. Compared with the conventional Transformer, this work introduces two attention modules in the decoder to explicitly model relationships between UAV and UGV images, the VLM-guided Positional Correction Attention (VPCA) module and the Shape-Aware Attention (SAA) module. These two attention modules are applied where encoder outputs enter the decoder, and the resulting features are aggregated and processed through normalization and feed-forward networks to compute UAV and UGV similarity.

Figure 3.

The structure of the proposed VSCM Network.

3.2.1. VLM-Guided Positional Correction Attention Module

The VPCA is designed to correct the spatial layout deviations of objects in the UAV image when observed from the UGV perspective. The formula of the VPCA module is defined as follows:

The query matrix is derived from encoded UGV image tokens, while the key matrix is constructed from encoded UAV image tokens, thereby capturing the cross-view association between UGV and UAV representations. The value matrix is also taken from UAV tokens, such that the attention weights computed from UAV-UGV correlations are applied to UAV features. This design ensures that the resulting representations encode how UAV information aligns with the UGV perspective, which is essential for cross-view matching. The is the VPCA bias and is adopted to mitigate the mapping error that arises when projecting the spatial structure observed in the UGV frontal-view image onto the UAV top-down perspective. Specifically, is implemented as a learnable lookup embedding that encodes the layout between UAV and UGV tokens. Formally, for the UGV token and the UAV token, the bias term is defined as:

where denotes the relative displacement between the spatial coordinates of the two tokens in the UGV and UAV views. is a learnable embedding table. Here, and represent the maximum allowable relative displacement along the x-axis and y-axis. The clipping operation constrains the displacement within a bounded range , ensuring stable indexing while preserving the discriminative power of the spatial layout.

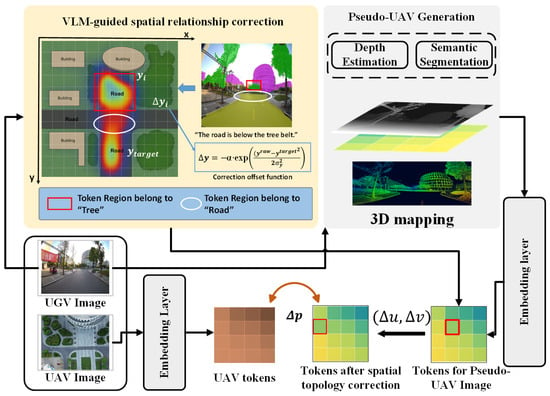

Figure 4 illustrates the procedure for computing . The key idea is to first construct a pseudo-UAV view based on the spatial layout of objects in the UGV image. Subsequently, a VLM-guided positional correction strategy is applied to refine the alignment between the encoded pseudo-UAV representation and the actual UAV tokens. Finally, the relative positional displacement between tokens from the corrected pseudo-UAV and UAV representations is computed, which serves as the input for the VPCA bias.

Figure 4.

The procedure of calculating . A VLM-guided spatial relationship correction module is adopted to correct the layout of UGV perspectives, which is converted to a pseudo-UAV representation.

3.2.2. Pseudo-UAV Image Generation

In the construction of the pseudo-UAV image, the UGV image is first processed by a depth estimation network [20] and a semantic segmentation network [21] to obtain its corresponding depth map and semantic map . Each pixel in the depth map is then back-projected into the camera coordinate system to generate its 3D coordinates . In parallel, a pose estimation module such as ORB-SLAM3 [22] is employed to estimate the current pose of the UGV image. Based on , these 3D points in the camera coordinate system can be transformed into the world coordinate system accordingly, denoted as .

Since the stitching process (in Section 3.3.1) provides the transformation matrices for each UAV image, the global 3D points corresponding to the UGV image can be further projected onto the UAV image plane using the UAV camera projection model. The resulting pixel coordinates are then normalized into the range of , yielding the pseudo-UAV image derived from the UGV view. It is worth noting that, due to the inherent limitations of the UGV viewpoint and occlusions, the pseudo-UAV image typically exhibits partial missing regions. Therefore, it can be regarded as an approximate projection of the objects observed within the UGV’s local field of view onto the UAV image plane. After generating the pseudo-UAV image , an embedding layer is applied to embed its features, resulting in the encoded pseudo-UAV representation .

3.2.3. VLM-Guided Spatial Relation Correction

In practice, the encoded pseudo-UAV image may suffer from spatial deviations of semantic objects caused by uncertainties in depth prediction and inaccuracies in pose estimation. In this work, we propose a VLM-guided spatial positional correction strategy. The core idea is to leverage semantic information extracted from the UGV image together with high-level language priors to refine the positional encodings of tokens that may be spatially misaligned due to depth prediction uncertainty or pose estimation errors.

Specifically, this strategy incorporates the BLIP-2 vision–language model [23] to analyze typical semantic entities within the UGV image, extracting objects’ spatial distribution and generating natural language descriptions of the relative spatial relations among objects. Subsequently, syntactic parsing is conducted using the SpaCy toolkit [24] to derive spatial relation triples of the form “Object A–Relative Spatial Relation–Object B”. To enhance the structural regularity and semantic consistency of the generated text, we design a set of structured language prompt templates to guide the language model in producing standardized descriptions that explicitly encode the expected spatial relations. Some language prompts are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of Language prompt templates for the given UGV image.

We construct a keyword set consisting of typical spatial relational phrases such as “in front of”, “to the left of”, and “to the right of”, as shown in Table 3. These keywords are matched within the textual descriptions generated by BLIP-2. Subsequently, based on the subject–predicate–object dependency structure in the syntactic tree, the subjects and objects associated with each spatial relational phrase are identified, thereby forming structured triples of the form

Table 3.

Examples of Language Descriptions and Corresponding Spatial Relationship Triplets.

For example, if the image is given by the natural language sentence “The road is on the left of the trees.”, dependency parsing yields the triple . For the semantic relation tripe , we first identify the tokens in that correspond to the subject and object entities. Let and denote the positional encodings of the subject and object tokens, respectively. Based on the semantic type of the spatial relation, a correction vector is generated to adjust the subject’s positional encoding. Specifically, if the spatial relation describes a front/back relation, the correction is applied along the y-axis. if it describes a left/right relation, the correction is applied along the x-axis. We defined a general Gaussian-shaped offset function to perform VLM-guided spatial refinement, which is formulated as follows:

Here, denotes the initial coordinates in the encoded and denotes the target token position where the subject entity is expected to appear. This target position is obtained from annotated supervision during training, serving as the ground-truth reference for positional correction. is a scaling coefficient controlling the magnitude of correction, and are parameters that determine the spatial range of influence along the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.

Based on the correction vectors defined in Equations (4) and (5), is adjusted to obtain the topology-corrected positional encoding, denoted as . By computing the relative displacement between and the encoded UAV representation according to Equation (2), can be derived accordingly. This bias explicitly incorporates both semantic relational constraints and spatial layout corrections into the cross-attention computation, thereby enhancing the consistency of UGV–UAV alignment.

It’s important to note that the ground-truth target positions serve only as supervisory signals during training to guide the network in learning an appropriate spatial correction relationship. During inference, the VPCA module operates fully automatically based on the pseudo-UAV tokens and VLM-derived spatial relations, without requiring any manual annotation or additional supervision.

3.2.4. Shape-Aware Attention Module

In addition to the VPCA module, we further design a shape-aware attention mechanism. Here, “shape” primarily refers to regions with distinctive structural layout configurations that are critical in UAV–UGV collaborative tasks. By explicitly encoding such layout patterns, the SAA module enhances the model’s ability to capture local structural correspondences between UAV and UGV views, thereby complementing the global relational modeling of the shape-aware module. The proposed SAA module is formulated as follows:

The SAA module follows the same setting as in the VPCA module, where the query is derived from UGV tokens, and both the key and value are taken from UAV tokens. is the shape-aware spatial bias term and is calculated as:

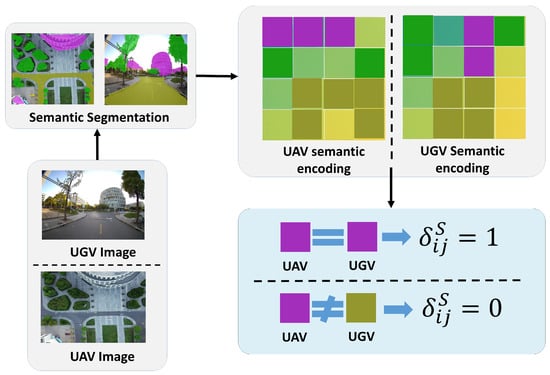

where is the attention amplification coefficient for structural regions, which can be set as a hyperparameter or learned during training. is the shape-aware bias matrix, and means the binary indicator that measures whether the token in position belongs to the same semantic type. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 5, both the UGV and UAV images are processed by the semantic segmentation network to generate semantic masks, and is calculated as:

Figure 5.

The calculation procedure of shape-aware bias .

3.2.5. Combined Loss Function

To improve the accuracy of cross-view image matching and ensure spatial structural consistency, we adopt a joint loss function composed of the binary cross-entropy loss [25] and the NE-Xent loss [26]. The combined loss encourages maximization of feature similarity for positive pairs while minimizing similarity for negative pairs, thereby improving the discriminative power of the network.

3.3. Ground-to-Aerial Mapping

This section builds upon the matching results obtained by VSCM-Net to further estimate the capture position of the UGV image within the UAV-stitched map. The proposed ground-to-aerial mapping module is composed of two main components: (i) UAV-stitched map generation, and (ii) cross-view localization. In both components, the intrinsic calibration of UAV and UGV images are conducted to eliminate the lens distortion of images.

3.3.1. UAV-Stitched Map Generation

To obtain a holistic aerial view of the environment, we employ an image stitching process to align and merge consecutive UAV images into a single panoramic representation . In particular, we adopt the Depth-Aided Incremental Image Stitching (DAIIS) method [20], which is specifically developed for low-altitude UAV imagery, to generate . Benefiting from its ability to compute precise transformation matrices among adjacent UAV images, DAIIS significantly reduces stitching errors caused by large depth variations. By effectively mitigating misalignment and artifacts, it produces seamless and geometrically accurate stitched images that closely resemble the real sense. In this work, the DAIIS module is used as an off-the-shelf stitching component to provide the aerial map. Based on DAIIS, the associated transformation matrix for each UAV image, which maps the image onto the stitched map , is obtained in this step. Note that the translation component is represented in pixel units rather than real-world metric units. To obtain a physical pixel-to-meter ratio , the UAV-stitched map is metrically calibrated using a ground reference baseline of the known size. By measuring the length of this baseline in pixels within the UAV-stitched map, can be obtained and the translation component in meter metric can be calculated accordingly. These transformations are subsequently employed for coordinate conversion between UGV and UAV during the cross-view localization process. More details about how to generate the UAV-stitched map and the corresponding quantitative evaluation of DAIIS can refer to our previous work [20].

3.3.2. Cross-View Localization

The proposed CVML framework takes the UGV image as input together with a sequence of UAV frames , and these UAV images are stitched as a combined panormic image . Based on the proposed VSCM-Net, the confidence heatmap can be produced between and each frames in . The most probable matching location for capturing is selected as the area in UAV images with the highest confidence.

where M denotes the index of where the highest similarity appears. represents the similarity that is calculated with the proposed VSCM-Net. is the local pixel coordinate corresponding to the maximum response in .

Since the transformation matrix between each local UAV image and the stitched global map is known from the stitching procedure, the position localized in the can be further mapped into the global stitched coordinate system, thereby yielding the global localization in .

Furthermore, to obtain the UGV’s location in the UAV-stitched map , we first manually annotate the UGV’s initial position in the corresponding UAV frame, which serves as an anchor for aligning the ORB-SLAM3 trajectory with the stitched map. The metric ORB-SLAM3 trajectory is then projected into by converting its meter-level displacements into pixel coordinates using the pixel-to-meter ratio, thereby generating the ground-truth pixel positions of the UGV. Since both the predicted matching location and the mapped ground-truth position reside in the same metrically calibrated stitched-map coordinate system, the Euclidean distance between two positions can directly yield the localization error in meters.

3.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

The overall computational cost of the proposed CVML framework is primarily dominated by the VSCM-Net, whose core architecture is Transformer. Let n denote the number of image tokens, d the feature dimension, and L the number of Transformer layers. The computational complexity of the Transformer backbone is approximately . In additional to this backbone, the two attention modules introduced in this work, VPC and SAA, require auxiliary semantic and geometric cues, thereby introducing additional computations from semantic segmentation, depth estimation, and BLIP-2 vision–language reasoning. The semantic segmentation module [21] follows a convolutional encoder-decoder structure with complexity , where is the input image resolution. The depth estimation module (U-Net based structure [20]) has a similar computational form, also scaling as . The BLIP-2 module [23] employs a Query Transformer, given t query tokens and hidden dimension , its complexity is , where is the number of layers in the query Transformer. All things considered, the overall computational of VSCM-Net is the sum of the compulexities of all the above modules.

4. Experiment Results and Analysis

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed CVML framework, focusing on two aspects: the accuracy of cross-view ground–aerial image matching using VSCM-Net, and the cross-view localization performance of CVML in real-world environments. To validate the proposed algorithm, two datasets were employed, one is the publicly available CVIAN dataset [27], and another one is a self-constructed low-altitude cross-view (LACV) dataset. All experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

4.1. Implementation Details

This section presents a detailed description of the training strategy employed for the proposed VSCM-Net, outlining the network configuration, optimization settings, and the two-stage learning paradigm designed to ensure stable and effective cross-view matching. In the first stage, the VSCM-Net equipped with a ConvNeXt-Base backbone is pretrained without the VPCA and SAA components. In the second stage, the full framework, incorporating both VPCA and SAA, is fine-tuned to capture geometry-corrected and shape-aware alignment cues. The Transformer layer adopts a 512-dimensional embedding space, an eight-head multi-head attention mechanism, and a 2048-dimensional feed-forward network. Additionally, 2D sinusoidal positional encoding with a dimensionality of 512 is applied to both the UAV and UGV tokens to preserve spatial structure within the Transformer. For both stages, training is performed for 100 epochs with a batch size of 16 using the AdamW optimizer. The initial learning rate is set to with a weight decay of . To stabilize early optimization, a linear warm-up is applied during the first of the training process, after which a cosine decay strategy is employed to gradually anneal the learning rate. Regularization is achieved through a dropout rate of within the Transformer layers.

4.2. Dataset

4.2.1. LACV Dataset

The LACV dataset was collected on the Baoshan Campus of Shanghai University using a DJI Mini 3 Pro UAV (DJI, Shenzhen, China) and a custom-built UGV equipped with a RealSense D455 camera (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The dataset comprises about 600 UAV images and 2000 UGV images, collected along three consecutive trajectories, for which the UGV ground-truth poses are available from the ORB-SLAM3. The UAV images are captured at an altitude of approximately 90 m. The resolution of the UGV image is , and the resolution of the UAV image is . The dataset covers diverse and complex campus scenes. UAV and UGV pairs are aligned manually to provide a high-quality benchmark for cross-view matching. Additionally, to support the training of the VPCA module, we provide additional semantic supervision on the LACV dataset. For each paired UAV-UGV image, the UAV image is annotated using the LabelMe tool to obtain semantic masks, and the ground-truth target positions of each semantic object can be obtained accordingly. The BILP-2 and SpaCy are used to extract semantic relational triples from the corresponding UGV image, providing semantic topology. Combined with the pseudo-UAV projection generated from UGV depth estimation, these components form supervision tuples that enable VPCA to learn spatial correction vectors. Importantly, these semantic annotations are required only during training. During inference, VPCA relies solely on pseudo-UAV imagery and VLM-derived relations. The dataset is publicly available at https://github.com/YoungRainy/LACV-Dataset (accessed on 1 November 2025).

4.2.2. CVIAN Dataset

The CVIAN dataset [27], collected in Florida, USA, in 2022, was designed for geolocalization and disaster mapping. It comprises 4121 cross-view pairs of street-view images (sourced from Mapillary via Site Tour 360) and very high-resolution satellite imagery, enabling fine-grained cross-view matching research. Each sample is annotated with accurate pose information, semantic labels, and cross-view correspondences. Spanning diverse urban and natural environments and incorporating challenging conditions such as occlusion, illumination variation, and dynamic objects, CVIAN provides a robust benchmark for cross-view geolocalization and post-disaster assessment. However, unlike the proposed LACV dataset, CVIAN consists of non-continuous street-view images that cover only a small portion of their corresponding satellite imagery. This makes it impossible to establish pixel-level semantic correspondences between the ground and aerial views. Consequently, CVIAN cannot provide the semantic target coordinates required to train the VPCA module, and the branch of VPCA is therefore disabled on this dataset. For this reason, in the subsequent matching experiments on CVIAN, only the SAA component of the proposed VSCM-Net framework is employed.

4.3. Comparative Methods and Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we compare it against four representative baselines, including GeoDTR [19], VIGOR [7], SemGEO [18], Sample4Geo [8] and EP-BEV [5]. To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, three commonly used metrics were employed: Top-K Recall (R@K), Average Precision (AP), and localization error (LE). R@K and AP are used to assess the accuracy of cross-view similarity matching, while localization error evaluates the positional discrepancy of the UGV image within the UAG image. To present the experimental results more intuitively, all localization errors are converted into metric units (meters) using the calibrated pixel-to-meter ratio.

4.4. Cross-View Matching Experiments

4.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

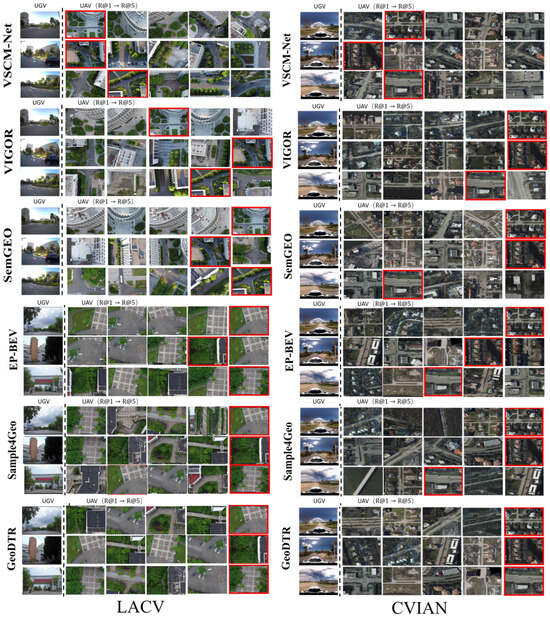

We first evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm on the cross-view similarity matching task. Figure 6 illustrates some typical similarity recognition results of the five methods on the two datasets. For each group, the left column shows the UGV query image, while the right column presents five UAV candidate images ranked from R@1 to R@5. The red bounding box highlights the first correct match, with its column position indicating the corresponding Top-K rank.

Figure 6.

Some cross-view similarity matching result examples of different algorithms in the LACV and CVIAN datasets.

Across the qualitative evaluations on the LACV dataset, it’s obvious that the proposed VSCM-Net consistently achieves high Top-1 accuracy. Its advantage derives from the dual-branch architectures: The VLM-guided positional correction leverages semantic and spatial topology priors to enhance cross-view semantic alignment, while the shape-aware attention module explicitly captures the geometric relationships between aerial and ground perspectives. The synergy of these two components enables robust matching under severe viewpoint variations, repetitive structural patterns, and occlusions, allowing the network to consistently locate the correct UAV candidate image within the top two ranks. In contrast, SemGEO demonstrates partial effectiveness. Even though SemGEO utilizes semantic segmentation to improve localization in low-texture regions (e.g., open grounds, road boundaries, lawns), the method lacks joint modeling of spatial geometry across aerial and ground perspectives, relying primarily on semantic category consistency. As a result, it struggles with challenges such as cross-scale discrepancies, repetitive structures, and occlusions. For instance, in Rows 1, visually similar but spatially incorrect regions are mistakenly identified as matches, highlighting the limitations of its semantic generalization ability. VIGOR and EP-BEV shows weaker adaptability on the LACV dataset due to their sensitivity to occlusions, scale variations, and asymmetric urban layouts. As a consequence, they often confuse highly textured but irrelevant regions (e.g., building facades or parking lots) with the correct match.

On the CVIAN dataset, the evaluation reveals notable performance degradation across all five methods compared with their results on the LACV dataset. SemGEO exhibits a marked performance decline on the CVIAN dataset. This decline may be attributed to the low resolution of satellite imagery and the sparse distribution of recognizable semantic objects such as roads, which weakens the performance of SemGEO, which heavily relies on semantic information. Among all algorithms, VIGOR performs the worst, with only a few correct matches appearing within the Top-5. This weakness mainly arises from VIGOR’s reliance on feature-based coarse-to-fine retrieval under the assumption of local appearance consistency between the ground and aerial views.

4.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

Table 4 and Table 5 present the Top-K Recall and AP results for five methods on the LSCV and CVIAN datasets separately. The results show that VSCM-Net consistently outperforms representative approaches VIGOR, SemGEO, Sample4Geo and EP-BEV in terms of R@1, validating the robustness and generalization of the proposed cross-view matching framework in diverse scales and semantic distributions.

Table 4.

Experimental results of Top-K Recall and Mean Average Precision on the LACV Dataset.

Table 5.

Experimental results of Top-K Recall and Mean Average Precision on the CVIAN Dataset.

On the LACV dataset, our method achieves the best performance across all three key metrics. In particular, the Top-1 recall reaches , markedly higher than GeoDTR , VIGOR , SemGEO (), Sample4Geo () and EP-BEV(), highlighting the model’s strong capability in producing highly accurate top-rank matches and ensuring robust localization reliability. The Top-5 recall attains , exceeding SemGEO by 12.61 percentage points and VIGOR by 34.77 percentage points, which indicates stable retrieval of the correct region within a compact candidate set. Furthermore, the AP of the proposed VSCM-Net reaches , substantially outperforming GeoDTR , VIGOR (), SemGEO (), Sample4Geo () and EP-BEV(), respectively, demonstrating that our approach yields more consistent and well-structured ranking distributions, thereby facilitating multi-candidate fusion and confidence-based decision-making.

Table 5 presents the comparative results on the CVIAN dataset. Overall, the proposed VSCM-Net achieves the best performance in R@1() and competitive results in both R@5() and AP(), demonstrating its superior discriminative capability under challenging cross-view conditions. Compared with GeoDTR, VIGOR and SemGEO, our method yields a significant improvement of , and in R@1, respectively, indicating more accurate top-ranked retrieval. With methods such as Sample4Geo and EP-BEV exhibiting higher R@5 values ( and , respectively), their R@1 scores remain notably lower, suggesting that these models tend to retrieve the correct matches within the top-5 candidates but lack fine-grained discriminability for precise top-1 localization. In contrast, the proposed VSCM-Net achieves a more balanced trade-off between retrieval accuracy and ranking precision, reflecting its ability to maintain stable correspondence across significant viewpoint and appearance variations.

Compared with the LACV dataset, the performance degradation observed on CVIAN can be attributed to its fundamentally different sensing configuration. In the LACV dataset, UGV images are front-view observations captured using a standard pinhole camera, which provides an undistorted perspective aligned with a common robotic perception system. In contrast, the CVIAN dataset employs panoramic ground images acquired by a camera. These panoramic observations need to be projected into equirectangular representations during preprocessing, introducing strong nonlinear geometric distortions in object shapes, scales, and spatial boundaries. Such distortions produce image structures that differ substantially from those of perspective pinhole images and violate the spatial assumptions required by the VPCA and SAA modules. As a result, the geometry-aware corrections designed for undistorted front-view inputs become less effective when applied to these panoramic representations, leading to reduced matching accuracy.

Another potential cause of the performance drop lies in the disparity of aerial viewpoints. The proposed VSCM-Net is tailored for matching between low-altitude UAV imagery and ground-level UGV view, which share a higher degree of spatial overlap and structural correspondence. In contrast, the CVIAN dataset pairs ground-level panoramas with high-altitude satellite images whose extremely large field-of-view results in severe scale inconsistencies. Under such conditions, the UGV-visible area occupies only a small portion of the satellite image, making spatial layout correction highly challenging and further degrading registration performance.

It is important to note that these limitations reflect the characteristics of the CVIAN sensing setup rather than the generalizability of the proposed framework in real-world deployments. In practical disaster-response scenarios, up-to-date satellite imagery is rarely available due to sudden environmental changes, and panoramic ground cameras are not commonly used on rescue robots. Instead, low-altitude UAV scanning is typically employed to obtain real-time post-disaster aerial imagery, and most UGVs are equipped with standard pinhole RGB cameras due to their robustness and simplicity. The sensing configuration assumed by the proposed CVML framework, front-view UGV images paired with the low-altitude stitched-UAV map, therefore directly corresponds to practical field conditions and ensures strong applicability in real-world environments.

4.4.3. Ablation Experimental Results on VPCA and SAA Modules

To further investigate the impact of the proposed VPCA and SAA modules on cross-view matching performance, we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the LACV dataset. Specifically, we first adopt the network without VPCA or SAA biases as the baseline. On this basis, we then introduce VPCA and SAA attention modules individually, followed by their joint integration, which corresponds to the proposed VSCM-Net. All experiments are conducted on the LACV dataset, with Top-1 recall, Top-5 recall, and AP employed as the primary evaluation metrics. The experimental results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of Ablation Study Results.

The baseline network achieves R@1, R@5, and AP of , , and , respectively, demonstrating limited matching capability and indicating that relying solely on appearance texture features is insufficient for stable and accurate matching in complex cross-view scenarios. When the VPCA module is integrated into the baseline network, the R@1, R@5, and AP increase to , , and , respectively. This clearly demonstrates that the proposed VPCA module effectively compensates for the limitations of the Transformer in modeling spatial consistency under significant cross-view variations.

The performance also improves when the SAA module is incorporated into the baseline network. Specifically, the associated R@1, r@5, and AP reach , , and , respectively, indicating that the shape-aware attention module positively contributes to cross-view matching performance.

Finally, when both VPCA and SAA are integrated, i.e., in the proposed VSCM-Net, the model achieves the best results across all three metrics, with R@1 of , R@5 of , and AP of . These results confirm the complementary roles of the two modules: VPCA facilitates global geometric layout modeling, while SAA enhances local structural alignment, and their joint effect leads to significant improvements in matching accuracy and robustness under complex cross-view conditions. Overall, the ablation study provides clear evidence of the critical contribution of our design. Compared with the baseline Transformer, the complete model achieves a remarkable improvement of percentage points in Top-1 recall, demonstrating that incorporating spatial topology modeling and shape-aware attention substantially enhances cross-view matching accuracy, ranking stability, and generalization capability, thereby providing solid technical support and design insights for real-world applications.

4.4.4. Ablation Experimental Results on Depth Estimation Noises

In this section, we analyze how depth estimation errors propagate to the pseudo-UAV projection in the VPCA module and influence the UAG-UGV cross-view matching accuracy. In the LACV dataset, we inject zero-mean Gaussian noise with standard deviations of , , and into the outputs of the depth estimation network . The experimental results, summarized in Table 7, show that the proposed VSCM-Net remains stable under low and moderate noise conditions. With , the impact is negligible, and R@1 decreases only slightly from to . When , R@1 declines to , demonstrating that the proposed VPCA and SAA modules can effectively compensate for moderate depth-induced spatial deviations. However, at , the pseudo-UAV projection becomes substantially distorted, causing R@1 to drop to . These results indicate that the proposed modules exhibit strong robustness to realistic depth uncertainties, and significant performance degradation occurs only under extreme noise levels that are unlikely to arise in practice.

Table 7.

The Experimental Results on Depth Estimation Noises.

4.4.5. Ablation Experiments on Semantic Segmentation Noises

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed VSCM-Net framework against uncertainties in semantic segmentation in the VPCA and SAA modules, we conduct an ablation study by perturbing the predicted semantic masks. Specifically, we introduce controlled segmentation noise by applying morphological dilation to the semantic masks using structuring elements of increasing size. The dilation kernel size K serves as the noise level, where large kernels expand semantic boundaries more aggressively and thus simulate stronger boundary ambiguity and segmentation errors. The experimental results are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

The Experimental Results on Semantic Segmentation Noises.

The results indicate that VSCM-Net remains stable under mild and moderate segmentation noise (), with only a slight degration in matching performance. This demonstrates that the proposed VPCA and SAA modules can effectively tolerate boundary-level inconsistencies in the semantic masks. However, when the dilation kernel is increased to , the masks become substantially distorted, merging or oversmoothing adjacent semantic regions. This serves to perturbation leads to a more noticeable performance drop, suggesting that cross-view matching begins to deteriorate when semantic structures deviate significantly from their true topology. Overall, the results confirm that the proposed VSCM-Net exhibits strong robustness to realistic semantic segmentation noise while revealing the limits under extreme perturbations.

4.4.6. Ablation Experiments on BLIP-2 in VPCA Module

In this section, we quantify the contribution of the VLM-guided spatial relationship correction module in the VPCA by conducting an ablation study comparing VSCM-Net with and without the BLIP-2 module on the LACV dataset. As shown in Table 9, removing BLIP-2 leads to substantial performance degradation; the R@1 score drops from to , which shows a reduction of . Additionally, the R@5 and AP exhibit similar declines. This phenomenon can be attributed to the limitations of pseudo-UAV images generated from the UGV viewpoint, which relay on depth estimation. In real-world environments, depth predictions are susceptible to discontinuities near object boundaries, often resulting in distorted relative positions and misaligned or deformed semantic regions in the pseudo-UAV projection. The VLM-guided spatial correction module incorporates high-level relationship priors derived from language-based semantic reasoning, enabling the model to infer plausible spatial locations. These findings underscore that VLM-derived relational information is not merely auxiliary but constitutes an essential component for achieving robust and semantically consistent cross-view matching in complex environments.

Table 9.

The Ablation Experimental Results on BLIP-2 in VPCA Module.

4.4.7. Ablation Experiments on Illumination

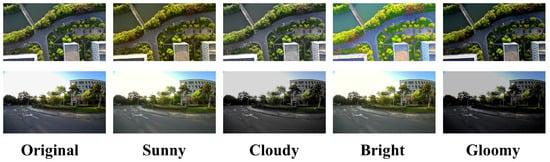

Seasonal changes in outdoor environments typically introduce significant variations in illumination, atmospheric conditions, and appearance characteristics. To systematically evaluate the robustness of the proposed framework under different seasonal conditions, we simulate diverse appearance variations on the LACV dataset through controlled photometric augmentation. Although the LACV dataset does not contain multi-season real-world captures, season-like variations can be approximated using image-level transformations that alter contrast and global brightness. As shown in Figure 7, four representative scene conditions are generated, including sunny, cloudy, bright, and gloomy, corresponding, respectively, to high-saturation summer scenes, low-contrast overcast conditions, high-luminance morning scenes, and low-light winter-like environments. The augmented datasets are than used for evaluation of the proposed method.

Figure 7.

The example of data augmentation results for different illuminations, including the simulations for sunny, cloudy, bright, and gloomy situations.

As shown in Table 10, the experimental results indicate that the proposed framework maintains strong localization performance under moderate illumination shifts. The sunny and cloudy conditions produce only minor decreases in R@1, R@5, and AP. In both cases, the illumination change does not substantially modify the structural edges or semantic boundaries of the scene. The dominant geometric features are largely preserved, enabling the network to extract consistent spatial cues. Therefore, semantic recognition and geometric structure estimation are not adversely affected, and the overall localization accuracy remained nearly unchanged. Performance degradation becomes more pronounced in the Bright condition, where excessive luminance reduces edge saliency and suppresses semantic segmentation cues. The diminished contrast also weakens the extraction of geometric structures, which together result in a noticeable drop in localization accuracy. The gloomy condition yields the largest performance reduction across all metrics, primarily due to substantial loss of texture, reduced semantic discriminability, and diminished contrast between built structures and surrounding terrain. Overall, this study demonstrates that the proposed VSCM-Net exhibits strong resilience under a wide range of illumination variations, while highlighting the challenges posed by extreme low-light conditions.

Table 10.

The Ablation Experimental Results on Different Illuminations.

4.5. Cross-View Localization in Real-World Experiments

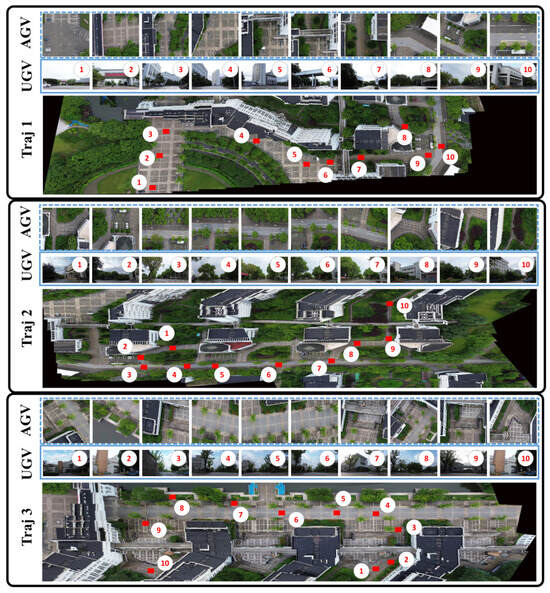

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed CVML framework, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of global localization accuracy using three representative trajectories (Traj 1, Traj 2, and Traj 3) from the LACV dataset. The evaluation includes two complementary components. First, for each trajectory, ten representative target points (a1–a10) with distinct scene characteristics—such as road intersections, turning points, and regions with significant viewpoint variation—were selected to assess the ground-truth localization error at these positions. Second, we analyzed the localization accuracy throughout the entire motion sequence of each trajectory. Note that the reported localization error in the proposed CVML framework combines both matching and stitching effects. In our experiments, visual checks of seam alignment and trajectory overlay did not reveal apparent stitching artifacts, suggesting that the majority of the error is induced by the matching component.

4.5.1. Landmark Point Localization Experiment and Analysis

Figure 8 illustrates the ground-truth positions of the testing landmark points on the stitched global map, together with their corresponding UGV and UAV image pairs. The selected landmarks encompass diverse geographic scenes, including open areas, narrow passages, branch intersections, main roads, and greenbelts. Such diversity enables a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed algorithm’s robustness and stability across various environmental conditions. The corresponding landmark point localization errors are summarized in Table 11.

Figure 8.

Illustration of representative landmark positions with distinct scene characteristics (e.g., intersections and turning points) for each trajectory. The corresponding UGV and UAV image pairs are shown to demonstrate cross-view visual differences.

Table 11.

The summary of the landmark point localization errors (m).

It can be observed that CVML consistently achieves the lowest localization error across all landmark points of the evaluated trajectories, with average errors of 4.8 m, 8.6 m, and 12.4 m in the three scenarios, respectively. In contrast, VIGOR reports errors of 28.4 m, 25.9 m, and 29.3 m, indicating that CVML improves localization accuracy by , , and , respectively.

Taking Traj 1 as an example, its ten landmarks can be grouped into four representative scene types: open areas (a1–a2), shape-transition segments covering straight-to-curve transitions and urban facades (a3–a5), occluded passages (a6–a7), and complex intersections involving multiple turns (a8–a10). The segmented statistics reveal that CVML achieves an average error of m in open areas (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), m in shape-transition segments (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), m in occluded passages (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), and m at complex intersections (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO).

These results clearly demonstrate that, regardless of continuous shape variation, severe occlusion, or complex intersection topology, the proposed CVML framework maintains low mean errors with reduced variance, underscoring its robustness and stability across diverse environments.

4.5.2. Trajectory Following Experiment and Analysis

Beyond the analysis of individual landmark points, we further carried out a comprehensive evaluation on the trajectory following performance of the proposed method. The full-trajectory following experiments not only provide an overall assessment of error distribution and stability during continuous motion but also demonstrate the practical applicability and deployment potential of the proposed framework in real-world scenarios.

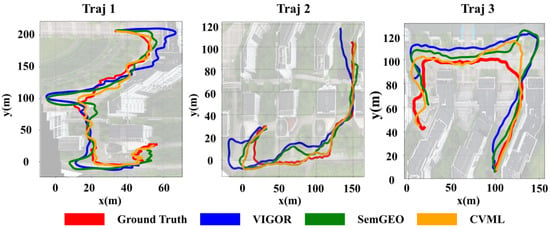

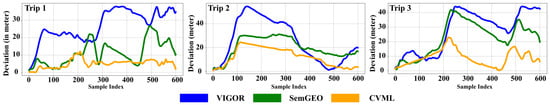

Figure 9 illustrates the comparison between the ground truth and the trajectories generated by VIGOR, SemGEO, and the proposed CVML, separately. The associated error distribution relative to the ground truth of each algorithm is shown in Figure 10. Overall, the trajectories generated by the proposed CVML align most closely with the ground truth, followed by SemGEO, while VIGOR exhibits the largest deviations. The most significant discrepancies are usually observed at turning regions, as shown in Traj 1 and Traj 3. The turning regions typically correspond to complex environments containing buildings, roads, trees, and other structures. Moreover, the UGV’s limited field of view may result in incomplete visual information, which degrades the matching performance of compared algorithms. This limitation is particularly detrimental to VIGOR, as its framework relies heavily on panoramic street-view imagery for accurate matching. Table 12 summarizes the trajectory localization errors of the three methods, and the proposed CVML consistently achieves the lowest average localization error across all trajectories, reducing the error by up to compared with VIGOR and by more than compared with SemGEO. Additionally, the proposed CVML exhibits the smallest standard deviation in all trajectories as well, indicating superior robustness and stability.

Figure 9.

The trajectory comparison between the ground truth and the trajectories generated by VIGOR, SemGEO, and the proposed CVML algorithms.

Figure 10.

The error distribution for the generated trajectories of VIGOR, SemGEO, and the proposed CVML algorithms in three trajectories.

Table 12.

The trajectory localization error and standard deviation for three methods.

Tanking Traj 3 as an example, the path includes two turns along the route. In the main road segment between two buildings (the lower-right part of the Traj 3), all algorithms achieve satisfactory matching and localization performance. This may be attributed to the relatively simple road structure in this segment, where the salient feature on the road’s sides are well-defined and can be effectively observed from the aerial viewport. However, a noticeable offset occurs for all three methods at the first turn. The proposed CVML promptly corrects its trajectory and converges back to the ground-truth path, whereas both VIGOR and SemGEO exhibit substantial errors in this region. For VIGOR and SemGEO, these deviations likely stem from their insufficient modeling of topological dependencies among complex semantic objects in UGV images captured at the turn, which hinders effective matching with the UAV image.

The intended use of the proposed CVML framework is GNSS-denied emergency response, where satellite imagery is often outdated, and ground conditions may have changed. In such scenarios, UAVs can generate a fresh stitched map, and localizing the UGV on this map supports rapid reconnaissance, route planning, and search tasks. Typical urban roads are 4–6 m wide, and our best results are sufficient for navigation and turning at road-scale resolutions.

5. Conclusions

This work proposed a VLM-guided and spatially consistent cross-view matching and localization framework for UGVs operating within UAV-stitched maps in GNSS-denied environments. Specifically, by embedding the VLM-guided positional correction attention module and shape-aware attention into a Transformer-based architecture, the VSCM-Net is designed to align semantic and structural correspondence between ground-level and aerial perspectives. The ground-to-aerial mapping module further projects the cross-view matching from the UGV image onto the UAV-stitched map, thereby determining the UGV’s capture position within the UAV-stitched map. Extensive experiments conducted on both public and self-collected datasets demonstrate that the proposed CVML framework achieves substantial improvements in cross-view matching accuracy and trajectory-level localization performance; although limitations remain, the results show practical potential for GNSS-denied emergency scenarios and provide a useful direction for futher research.

In future work, we will further extend the CVML framework to incorporate panoramic cameras to exploit its capability of capturing environmental information. This includes exploring distortion-free panoramic encoding strategies and geometry-consistent representation methods. Such extensions are expected to improve UGV localization accuracy within the UAV-stitched map and better meet the practical demands of disaster response applications. Beyond senor modalities, we plan to construct large and more diverse datasets covering different seasons, cities, and scene types. Another research direction is to develop illumination-invariant feature encoder to address performance degradation in extreme lighting conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, Y.Y. and Y.X.; software, X.M. and Z.J.; validation, X.M., W.Q., Z.J., P.S. and X.Z.; formal analysis, X.M.; investigation, X.M., P.S. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and W.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., X.M. and Y.X.; visualization, Y.Y., P.S., X.Z. and W.Q.; supervision, Y.X.; project administration, W.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), No. 62303294.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/YoungRainy/LACV-Dataset (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Wei Qian was employed by the company China Construction Eighth Engineering Division Bureau Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mahyar, A.; Motamednia, H.; Rahmati, D. Deep Perspective Transformation Based Vehicle Localization on Bird’s Eye View. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.06796. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z.; Booij, O.; Kooij, J.F.P. Convolutional Cross-View Pose Estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 3813–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, H. Beyond Cross-view Image Retrieval: Highly Accurate Vehicle Localization Using Satellite Image. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 16989–16999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, R.; Cui, Z.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Y. Fine-grained cross-view geo-localization using a correlation-aware homography estimator. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 5301–5319. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Lv, Z.; Li, W.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.; Zhong, H.; He, C. Cross-View Image Geo-Localization with Panorama-BEV Co-retrieval Network. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Shah, M. Cross-View Image Matching for Geo-Localization in Urban Environments. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1998–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, T.; Chen, C. VIGOR: Cross-View Image Geo-localization beyond One-to-one Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual Conference, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 5316–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuser, F.; Habel, K.; Oswald, N. Sample4Geo: Hard Negative Sampling For Cross-View Geo-Localisation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 16801–16810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Shah, M.; Chen, C. TransGeo: Transformer Is All You Need for Cross-view Image Geo-localization. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Dong, W.; Wang, W.; Kaess, M. BEVRender: Vision-based Cross-view Vehicle Registration in Off-road GNSS-denied Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 11032–11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, C.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Xia, G.S. Learning Cross-View Visual Geo-Localization Without Ground Truth. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5632017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, B.; Xiang, S.; Meng, G.; Ye, J. AddressVLM: Cross-view Alignment Tuning for Image Address Localization using Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10667. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, X. Semantic Concept Perception Network With Interactive Prompting for Cross-View Image Geo-Localization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 5343–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Pan, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, M.; Fu, M. Hybrid Perspective Mapping: Align Method for Cross-View Image-Based Geo-Localization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Chen, C.; Shah, M. GAMa: Cross-View Video Geo-Localization. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; pp. 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Shen, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z. A Cross-Mamba Interaction Network for UAV-to-Satallite Geolocalization. Drones 2025, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Xu, W.; Chen, N.; Zheng, E. An Efficient Pyramid Transformer Network for Cross-View Geo-Localization in Complex Terrains. Drones 2025, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Tani, M. SemGeo: Semantic Keywords for Cross-View Image Geo-Localization. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Sultani, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wshah, S. Cross-view geo-localization via learning disentangled geometric layout correspondence. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-Fifth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Thirteenth Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. AAAI’23/IAAI’23/EAAI’23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, K.; Xie, S.; Xie, Y. Enhanced Incremental Image Stitching for Low-Altitude UAV Imagery With Depth Estimation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 3992–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual–Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S.C.H. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, X.; Kubler, S.; Robert, J.; Papadakis, M.; LeTraon, Y. A Replicable Comparison Study of NER Software: StanfordNLP, NLTK, OpenNLP, SpaCy, Gate. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; pp. 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.H.; Schmitt, M.; Mou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.X. Identifying Corresponding Patches in SAR and Optical Images With a Pseudo-Siamese CNN. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020. ICML’20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Deuser, F.; Yin, W.; Luo, X.; Walther, P.; Mai, G.; Huang, W.; Werner, M. Cross-view geolocalization and disaster mapping with street-view and VHR satellite imagery: A case study of Hurricane IAN. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 220, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).