Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A UAV-mounted lightweight topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensor captured high density point clouds with low mean vertical error.

- Vertical errors are higher for wet areas with concave three-dimensional shapes.

What are the implication of the main findings?

- A new generation of lightweight topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensors that can increase the efficiency of topographic surveys.

- Targeted ground-based surveys of deep areas are necessary to minimise spatial bias in error.

Abstract

Quantifying riverscape topography is challenging because riverscapes comprise of both wet and dry surfaces. Advances have been made in demonstrating the capability of mounting topo-bathymetric LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensors on crewed, occupied aircraft to quantify riverscape topography. However, only recently has miniaturisation of electronic components enabled topo-bathymetric LiDAR to be mounted on consumer-grade Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). We evaluate the capability of a demonstration YellowScan Navigator topo-bathymetric, full waveform LiDAR sensor, mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 UAV, to survey a 1 km long reach of the braided River Feshie, Scotland. Ground-truth data, with centimetre accuracy, were collected across wet areas using an echo-sounder, and in wet and dry areas using RTK-GNSS (Real-Time Kinematic Global Navigation Satellite System). The processed point cloud had a density of 62 points/m2. Ground-truth mean errors (and standard deviation) across dry gravel bars were 0.06 ± 0.04 m, along shallow channel beds were −0.03 ± 0.12 m and for deep channels were −0.08 m ± 0.23 m. Geomorphic units with a concave three-dimensional shape (pools, troughs), associated with deeper water, had larger negative errors and wider ranges of residuals than planar or convex units. The case study demonstrates the potential of using UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR to enhance survey efficiency but a need to evaluate spatial error distribution.

1. Introduction

1.1. General Background

Quantifying riverscape topography is challenging because riverscapes comprise of both wet and dry surfaces and often include vegetation canopies [1]. Despite these challenges, producing three-dimensional models that accurately represent the topography of riverscapes is essential for a range of river science and management applications [2] including flood risk modelling [3,4,5], river restoration [6], physical habitat and geomorphic change assessment [7,8] and surface sediment characterisation [9]. A variety of satellite, airborne and ground-based remote sensing approaches [10] have been used to create spatially continuous riverscape Digital Elevation Models (DEMs). These approaches typically use different techniques to quantify the topography of wet and dry areas, and then fuse these topographic models together [1,11,12]. Over the last several decades, topo-bathymetric Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) sensors mounted on human occupied aircraft have been applied to quantify riverscape topography [13,14]. Whilst data acquired in wet areas are subjected to additional data processing, algorithms enable the automatic classification of wet areas [15] and subsequent correction of survey returns for their refraction through water, resulting in a seamless point cloud of wet and dry points. Occupied, airborne topo-bathymetric surveys are thus facilitating wet–dry riverscape surveys at the catchment scale but for smaller spatial scales (e.g., 100–101 km river valley length), the costs are typically prohibitive. However, a new generation of topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensors that are lighter, miniaturised and have lower power requirements now present an opportunity for topo-bathymetric LiDAR to be mounted on consumer-grade Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (UAVs; [16,17]) and substantially improve the efficiency of riverscape surveys.

1.2. Related Works: State of the Art

Other direct or near-direct [18] methods of surveying river bathymetry, which can be deployed by wading or from boats, include single [19] and multi-beam [20] echo-sounding and rod-based sampling using total station or Real-Time Kinematic Global Navigation Satellite Systems (RTK-GNSS) [21]. An alternative approach, which offers more even spatial coverage, is indirect measurement of fluvial bathymetric [18], typically through the correction of terrestrial focused remote sensing data. Spectral-depth approaches [22,23,24] have been widely applied in clear-flowing and shallow river environments, with errors typically 0.10 m for water depths less than 1 m [25]. However, calibrations have been shown to be site specific and scene illumination, substrate type, turbidity, overhanging vegetation and water surface roughness can complicate bathymetric reconstruction [12,26,27,28]. Techniques have also been developed to adjust Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetric [29] reconstructions of river bathymetry by correcting for refraction through water, both on a pixel-by-pixel basis across a DEM [30] and by correcting points in a point cloud that have been generated from images acquired from different positions and angles [31]. Both of these correction techniques require additional processing beyond standard SfM photogrammetry workflows and are heavily reliant on a good estimation the position of the air–water medium transition [32]. Further indirect techniques that are based upon heuristic estimation [33] and artificial intelligence [34] are also emerging.

The greatest advantage of airborne topo-bathymetric LiDAR surveys in riverscape environments is that they enable the generation of spatially continuous DEMs of both dry and wet surfaces, so long as water is sufficiently shallow to allow LiDAR returns to be acquired from the riverbed. Recent reviews of topo-bathymetric LiDAR have focused upon LiDAR principles and technological advances [35], and environmental and technical conditions that influence vertical errors in river environments [4]. An error evaluation meta-analysis in the latter review, drawing upon technical report and academic papers, indicates depth measurement accuracy (median value) of 0.16 m (sample size, n = 57), root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.15 m (n = 53) and a precision (standard deviation) of 0.20 m (n = 48). The meta-analysis drew upon investigations across a variety of geographic areas, representing a diversity of river types [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Uncertainty arises from a variety of different sources, including environmental context (including water turbidity, riparian vegetation, riverbed morphology, streambed reflectance, depth, bubbles and beam attenuation), measurement techniques, processing and sensor hardware [4]. Despite these uncertainties, if airborne topo-bathymetric LiDAR is applied to riverscapes where the LiDAR signal can reach and be returned from the river bed and water column then it provides a suitable source of topographic data for a range of applications across riverscapes with scales > 1 km.

UAVs have enabled a variety of sensors [42], to acquire observations of riverscapes at the reach spatial scale. To generate riverscape topographic models, UAVs have been extensively used to acquire RGB imagery for SfM photogrammetry and to mount LiDAR [43], including both mirror-based [44] and solid-state sensors [45] that can acquire returns from dry topography. In a review of trends in topo-bathymetric LiDAR, Pricope and Bashit [46] observe that examples are emerging of topo-bathymetric sensors that are mounted on UAVs. In a fluvial context, three pertinent investigations have assessed UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR with ground truth observations of wet area topography. Kinzel et al. [17] used an EDGETM topo-bathymetric LiDAR, mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 Pro UAV, to survey four sand- and gravel-bed rivers, with contrasting optical water characteristics. Ground truth observations of seven cross-sections through wet areas of the four rivers were acquired using an RTK-GNSS receiver mounted on a survey rod and a multi-beam echo sounder (MBES). Comparisons yielded regression R2 values of 0.60 to 0.97 for shallow cross-sections and 0.72 for the deep cross-section. Mandlburger et al. [16] used a Riegl VQ-840-G topo-bathymetric LiDAR mounted on a RiCOPTER-M UAV to survey a gravel-bed reach. The UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR dataset was compared to an airborne bathymetric-LiDAR cross-section survey acquired with an occupied fixed wing aircraft, and 19 black-and-white checkerboard discs that were anchored to the river bed and positioned using a total station. A comparison between the position of these discs and the LiDAR dataset produced a maximum deviation of 0.08 m. Islam et al. [47] used a TDOT GREEN sensor to survey a 1.2 km long reach of a multi-thread gravel-bed river. A total of 150 ground truth observations were acquired in wet areas during each survey, using a total station. Comparisons yielded regression R2 values of 0.98 and 0.91, and RMSE of 0.07 m and 0.09 m for the winter and autumn surveys respectively. In a coastal environment, near Dazhou Island, China, Wang et al. [48] demonstrated bed-level absolute accuracies of 0.13 m for the application of a Mapper4000U LiDAR mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 Pro UAV. Together, these examples demonstrate the feasibility of mounting topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensors on UAVs, but there is a need for further error assessment and analysis to evaluate patterns in relationships between vertical error and different physical topographic characteristics of fluvial environments to minimise systematic errors in riverscape DEMs.

1.3. Aim, Methodological Overview and Methodology

Our aim is to assess the accuracy of a demonstration YellowScan Navigator topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensor, mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 UAV, to survey a 1 km long braided riverscape that features both wet and dry areas. The application of this sensor to survey riverscapes is novel because the senor is lightweight (3 kg); this payload on a small size UAV enables riverscape surveys at the 1 km scale to be acquired over a few hours. We assess accuracy using a set of observations from RTK-GNSS mounted on a pole, to measure dry and shallow water surfaces, and an echo-sounder to measure deep water surfaces. We statistically assess these observations to the processed topo-bathymetric point cloud. We further assess the errors by classifying the comparison into different geomorphic units, to enable evaluation of differences in errors based on the different forms that create a river’s wet topography. Subsequently, we identify and discuss a number of areas of interest that are characterised by comparably lower accuracies, to guide future surveys. We also compare the accuracies obtained in this investigation to those obtained using other approaches. This paper adds a further investigation to a few existing UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR fluvial case studies; we assess a LiDAR sensor that has not previously been evaluated and undertake a novel approach to error analysis that is framed around geomorphic units and based on a large number of spatially distributed ground truth observations.

2. Study Area

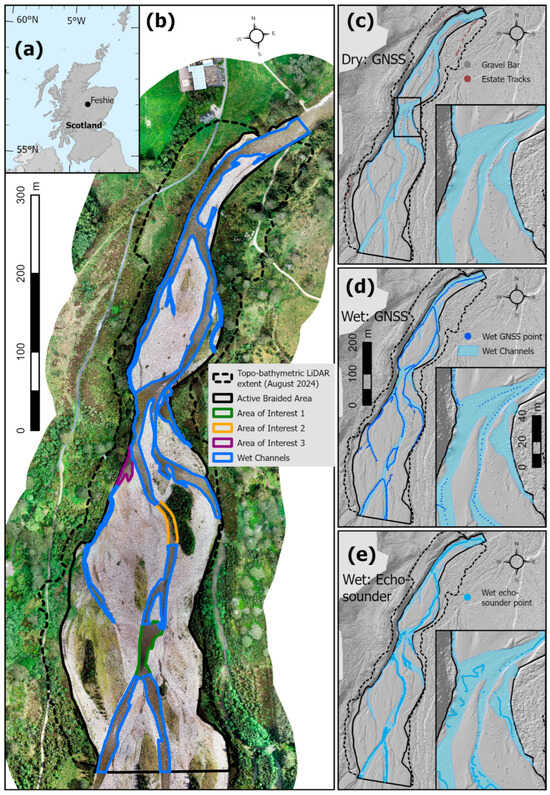

A braided reach of the River Feshie, Cairngorm Mountains, Scotland, was chosen as the study site to assess the capability of UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR (Figure 1). This braided reach upstream from Coire Domhain (57.022129° N, 3.9017601° W) has been widely used, over several decades, to assess the capabilities of different survey platforms to quantify riverscape topography due to its topographic and bathymetric complexity. Previous geomatics technologies that have been assessed include RTK-GNSS [49,50], spectral depth correction from aerial photogrammetry [51] and a variety of ground-based and airborne techniques to quantify dry topography [8,45,52,53,54]. One single thread length of the reach has also been instrumented with seismic and hydroacoustic instrumentation to monitor bedload transport [55].

Figure 1.

Overview of study site in the River Feshie, Scotland and ground-truth data collected. (a) Location of River Feshie site in Scotland. (b) Overview of 1 km reach surveyed using UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR including channel positions from June 2024 and three identified Areas of Interest (AoI). (c–e) Overviews and zoomed in insets of the three ground-truth data types to show spatial sampling pattern including (c) RTK-GNSS on dry topographic surfaces, (d) RTK-GNSS in shallow wetted channels and (e) echo-sounder in deeper parts of the wetted channels.

The study reach has varying sediment sizes, from sand through to cobbles, and is characterised by a D50 surface grain size of 50–110 mm [53]. Woody vegetation densities across the valley bottom are increasing, including on islands within the active river channel. This is due to an active and ongoing approach to manage deer numbers which is enabling vegetation regrowth [56,57]. In the active channel, islands are typically colonised with grasses, sedges and heather, and as a result of deer management, woody species such as Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris), silver birch (Betula pendula) and common/grey alder (Alnus glutinosa/Alnus incana) are becoming established on both islands within the active channel and more widely across the River Feshie’s floodplains and terraces. At the time of survey, in August 2024, wet anabranches occupied 21% of the active width. The river was at a low flow (3.1 m3/s at Feshiebridge), with minimal morphological change since the full annual survey conducted earlier in the summer in June 2024. A Secchi disc was placed at the bottom of the deepest pool, visible at a depth of 1.3 m.

3. Methods

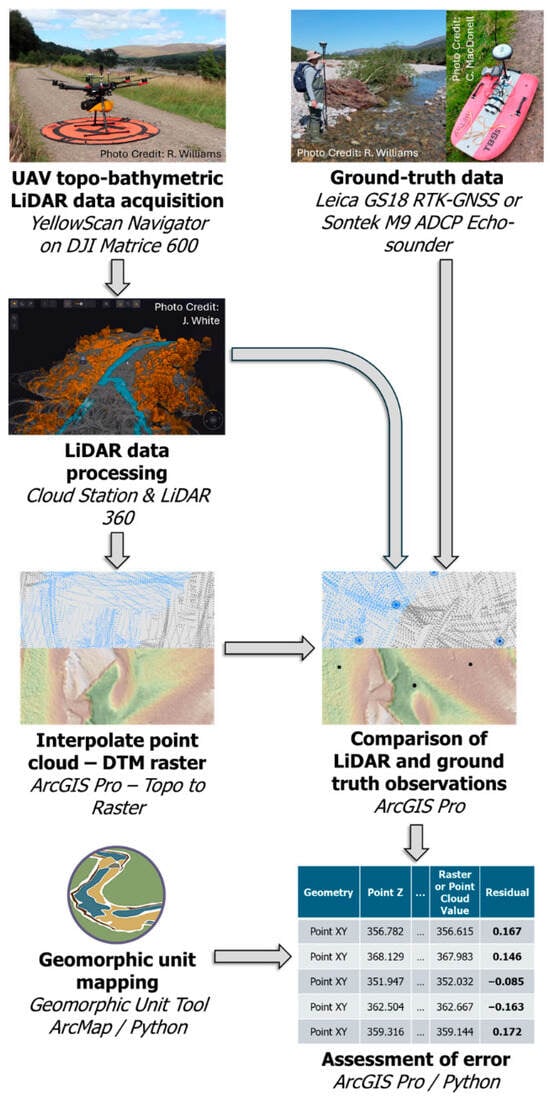

Figure 2 illustrates the overall methodological workflow; each methodological step is then explained in the sub-sections below. In brief, we acquired topo-bathymetric LiDAR using a YellowScan Navigator sensor (Montpellier, France) and DJI Matric 600 UAV (Shenzhen, China). We also acquired ground-truth data of wet and dry areas using a Leica GS18 RTK-GNSS (Balgach, Switzerland) and Sontek M9 Acoustic Doppelar Current Profiler (ADCP; San Diego, CA, USA used in echo-sounder mode. We processed the LiDAR data using Cloud Station and LiDAR 360 software, produced a DEM using interpolation, and then compared the LiDAR point cloud and DEM product to the ground truth data. Finally, we used consistent geomorphic unit mapping to assess whether there were spatial trends in the in-channel errors.

Figure 2.

Method flow diagram showing overall scope of data collection, processing and analysis undertaken as part of this study. Bold text indicates main methodological stages. Italic text indicates hardware or software used. See also Figure 3 for more detail on point cloud processing.

3.1. UAV Topo-Bathymetric LiDAR Data Acquisition

A pre-production demonstration prototype of the YellowScan Navigator system (Table 1) was used, mounted on the DJI Matrice 600 UAV. The Universal Ground Control System (UGCS) Mission Planner was used to pre-populate an Area of Interest (AoI) KML file with survey lines of specified mission parameters and used to execute the flights from multiple Take-Off and Landing sites (TOLS). The sensor was positioned and oriented using onboard GNSS recording on the aircraft, in additional to Inertial Navigation System (INS) and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) data collected at 200 Hz. Calibration patterns for the INS and IMU were flown before and after each data collection period to enable forward and backward IMU drift calibration to be performed later. The LiDAR scan side overlap was set to 50%, a full waveform was recorded at a sampling rate of 160 kHz with a conical scanning pattern. The flying height was 80 m above the valley bottom. Survey lines utilise DEM data from the National LiDAR Program to maintain constant separation between the scanner and the valley bottom to ensure uniform point-density across the variable topography of the valley. The flight path pattern was aligned to remain within UK CAA Visual Line-of-Sight recommendations for flying UAVs. Due to flight time limitations (12 min maximum) associated with the DJI Matrice 600 UAV battery duration and the weight of the Navigator system payload, the reach was split into five flight blocks, which were spaced longitudinally along the valley bottom. Flight lines were orientated in a transverse direction across the valley bottom. These separate flights were subsequently merged at data processing stages. LiDAR data were stored on an SD card within the sensor.

Table 1.

Technical specifications of YellowScan Navigator pre-production demonstration prototype.

3.2. LiDAR Data Processing

The LiDAR data processing followed the method workflow outlined in Figure 3. The first stage was to refine the position and orientation of the aircraft and LIDAR sensor. Using YellowScan CloudStation software and SBG Qinertia software, the raw GNSS observations and aircraft trajectory data were loaded, including the IMU calibration observations that were acquired before and after each flight. The positional data was post-processed against raw GNSS observations data collected over a known benchmark, which itself was correlated to the nearest Ordnance Survey (OS) Net continuously observing GNSS station (BRAE; Braemar). Once completed, this processing resulted in acceptable position and orientation accuracies. At this stage the lever-arm offset between the GNSS antenna phase centre and the laser recording location was applied to synchronise the laser positions.

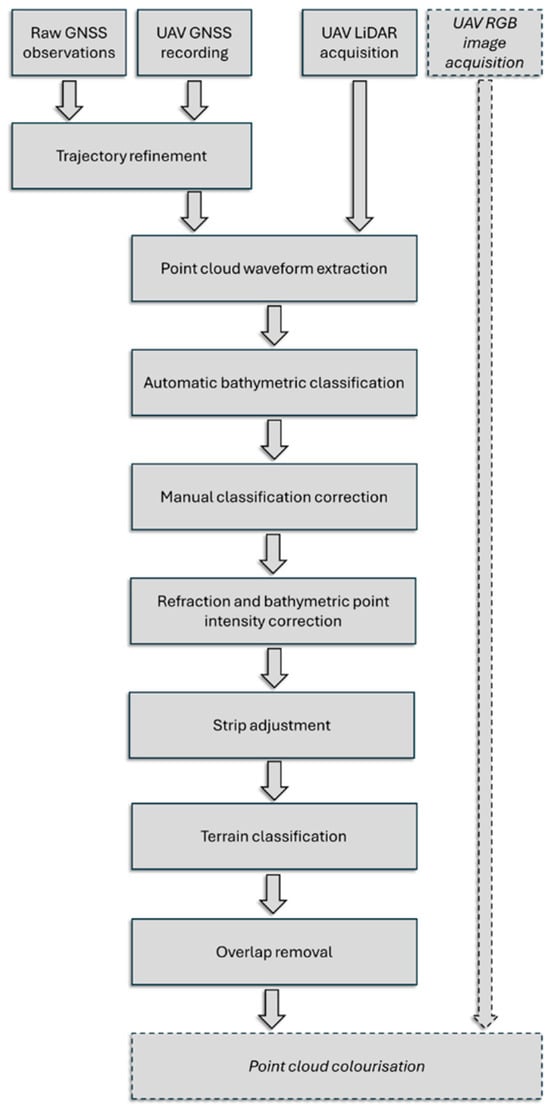

Figure 3.

Workflow diagram for point cloud data processing. Note that the sensor used was a pre-production demonstration prototype that did not have an RGB camera unit installed, so this part of the workflow is shown with dotted lines.

The next step was full waveform point cloud extraction. For the 1 km river reach, the raw waveform file was approximately 80 GB. Extraction was performed using CloudStation software, with low, medium and high sensitivity options. The wave extraction algorithm assessed each waveform for strong return peaks, with up to 10 points per waveform being assessed. The algorithm also applied a neighbourhood operation to ensure consistency in the signal around neighbouring points. Medium sensitivity provided the best results in terms of noise above and below the point cloud. Next, the initial point cloud was classified to separate terrain and bathymetric points. An automated process that assessed the full waveform of returns was first conducted to assess whether a point was terrain, water surface or riverbed. The extent of the river channel was then manually refined before subsurface points were corrected for intensity and refraction, using a refractive index value of 1.33. These steps produced completed the geometric derivation of the point cloud from the raw laser waveform.

To refine the point cloud, the first stage was strip adjustment to identify and correct misalignment between adjacent flight lines. This was conducted with a closest point cloud iteration algorithm, which found common points between overlapping strips and made minor adjustments to the roll angle of a position along a flight line to iterate towards a single uniform surface. The second stage was further terrain classification, identifying and classifying non-terrain objects, such as trees, buildings, people and vehicles, and removing the water surface points. Third, the point cloud was thinned in areas of flight overlap to produce a more uniform point cloud density across the study area. Next, outlier points were manually cleaned using a cross-sectional view of the point cloud. Finally, the point cloud was exported in .las format.

3.3. Ground Truth Data

Ground-truth data points with horizontal and vertical positioning were acquired. In the wetted channels, two techniques were used for shallow (<0.2 m) and deep (>0.2 m) areas. In shallow areas, Leica GS18 survey-grade RTK-GNSS antennas mounted on survey poles were used to collect topographic points (1 s occupation with tilt compensation) of the bed level (n = 556). These RTK-GNSS units were connected to a Leica GNSS base station setup on a tripod over a stable ground mark that has previously been observed [8] in GNSS static mode for 8 h and post-processed with RINEX (Receiver INdependent Exchange) data from the nearest Ordnance Survey (OS) Net station to calculate the base station’s coordinates. In areas of greater than 0.2 m depth, a Sontek M9 ADCP was used as an echo-sounder to collect high frequency (1 Hz) points using the angle-corrected average Bottom Track measurement (n = 2673). This unit was mounted on a hydro-board and towed by rope throughout the channels. The unit was positioned using a Leica GS16, connected to same base station as the RTK-GNSS units. The ADCP data collected were processed in Sontek RiverSurveyor software and also using a custom MATLAB script to account for antenna-sensor offset and filter points with inaccurate GNSS positioning or depths, such as when the unit was picked up out of a shallow channel area and moved.

Points across dry surfaces were observed using the aforementioned RTK-GNSS units on exposed gravel bars (n = 237) and the estate tracks (n = 48). The average quality of the RTK-GNSS measurements across all wet and dry points was 0.019 m.

3.4. Comparison of LiDAR and Ground Truth Observations

The comparison between the LiDAR point cloud and ground truth observations focused upon assessing vertical accuracy. A proximity analysis was undertaken, using the same approach as [45], to compare ground truth point observations to the LiDAR point cloud. For each ground-truth observation (except ground control point targets), a 0.1 m buffer was created from the horizontal position of the given ground-truth observation. Then all LiDAR points with a given buffer were extracted and the measured elevation averaged to provide an average LiDAR elevation with the buffered area. This averaged LiDAR elevation was then compared against the measured elevation for the ground-truth data to give an individual residual. Some ground-truth points were excluded at this stage after considering their proximity to overhanging vegetation. These residuals were then summarised for four ground-truth observation types based on the equipment and surface type: RTK-GNSS on gravel bars, estate tracks and in the wetted channel, and the ADCP echo-sounder in the wetted channel.

Following the initial comparison, three AoIs were defined (Figure 1b) for local error analysis, based upon the clustering of high residuals. These areas were characterised by a deep pool (AoI 1), overhanging vegetation (AoI 2) and a sand, rather than gravel, river bed (AoI 3).

3.5. Interpolation to Produce Digital Terrain Model

A wet–dry Digital Terrain Model (DTM) was interpolated from the classified point cloud using Classes 2 (Ground), 40, 41 and 45 (Reserved—wet channel bathymetry), whilst excluding Class 1 (unclassified) to remove vegetation and Class 7 (low point noise) to minimise point cloud noise. An ESRI ArcGIS Topo to Raster interpolation, without drainage enforcement, was used, as recommended for point-based datasets by [58,59]. The same ground truth data was also used to perform quality checks on modelled elevation in the final DTM surface. This was achieved by extracting the DTM raster elevation value at the XY location and comparing it to the measured ground-truth value to provide a residual. These residual values were summarised into the same four ground-truth observation types based on the equipment and surface type as the point cloud residuals.

3.6. Assessment of Error and Geomorphic Unit Form

To investigate whether there was a relationship between geomorphic unit type and vertical error, geomorphic units were mapped using the Geomorphic Unit Toolbox (GUT; [60]). GUT is freely downloadable online and runs using Python 2.7 code. The tool leverages high-resolution topography to delineate geomorphic units in a consistent, objective manner in a three-tiered hierarchical framework, and has been previously applied by [8,61]. For this analysis, the default settings were used, as defined in comment text throughout the Python code script files available online. Tier 2 unit form products from GUT were used to classify the DEM into the following units: bowl, trough, plane, wall, saddle, bowl transition and mound transition. These unit forms are analogous to geomorphic units, for example a bowl corresponds to a pool, a trough to a glide-run, a wall to a bank, and a saddle to a riffle. However, focusing the analysis upon geometric shape (i.e., unit form) rather than geomorphic unit allows the analysis to compare errors to the different three-dimensional shapes of the topography.

To provide independent topography for GUT, a DEM from a previous survey acquired several months earlier in June 2024 was used. The river was geomorphologically stable between these two surveys, with the network of channels being in similar alignment. There was minor variation in water level between the surveys. Dry topography in the June 2024 DEM was generated from a DJI L1 Zemuse LiDAR sensor, mounted on a DJI M300 RTK UAV and processed using the methods of [45]. Wet topography was generated by processing the images acquired using the same L1 sensor using SfM photogrammetry implemented in Pix4D software (v4.5.6), using the method described in [54], and then correcting for refraction using the method of [30]. Once geomorphic units were delineated, the final classification was reviewed against the orthomosaic imagery from the June 2024 to identify any noticeable errors. No manual corrections or re-runs with adjust input datasets were required. An error analysis was then undertaken that classified the ground truth observations by geomorphic unit type.

4. Results

4.1. Vertical Error Assessment

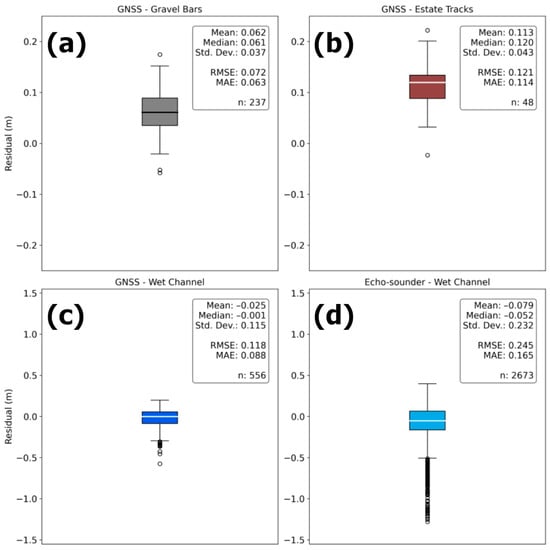

Figure 4 shows the residuals, and a set of associated error metrics, for a comparison between the LiDAR point cloud and ground-truth observations. The residuals are classified based upon the ground surface type: gravel bars, estate tracks and wet channels surveyed by GNSS or echo-sounding. On dry gravel bar areas, the residual between the ground-truth and LiDAR points varied between 0.061 m and 0.072 m across the mean, median, RMSE and mean absolute error (MAE) metrics, with a tight standard deviation of 0.037 m (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1). Comparison points along the dry tracks were characterised by a higher mean of 0.113 m, but were characterised by a similar standard deviation of 0.043 m to the gravel bars. In the wet channel, mean and median average residuals were closer to zero; however, the standard deviation of these residuals was higher, with values of 0.115 m for shallow water measured with RTK-GNSS and 0.232 m for deep water measured with the echo-sounder.

Figure 4.

Boxplots showing residuals between ground-truth data and UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR points within 0.1 m of each ground truth point, for different surface types and ground-truth data collection methods: (a) RTK-GNSS surveyed dry gravel-bars; (b) RTK-GNSS surveyed dry tracks; (c) RTK-GNSS surveyed wet channels; and (d) echo-sounder surveyed wet channels. The colours of the boxplots match the colours of the different ground-truth data types shown in Figure 1c–e and Figure 7. Dots in the box plots that are beyond the whiskers represent outliers; these data points have values that are greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box edges.

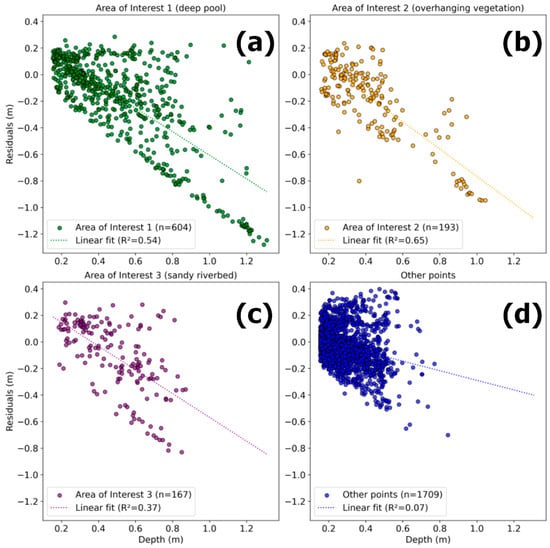

To further evaluate the source of higher residuals, the bed level residuals between the ground-truth and bathymetric LiDAR were compared to water depth (Figure 4). The mean average water depth of points collected by the ADCP was 0.36 m. About 82.7% of residuals ranged between −0.25 m and +0.25 m. Overall, there was a weak linear correlation between depth and residual, with an overall R2 of 0.40 for all points combined (Supplementary Table S2).

4.2. Areas of Interest Segmented Residuals

The distribution of residuals shown in Figure 4 was examined further by spatially mapping the residuals. This showed that high negative residuals were clustered into three areas, whose extents were digitised into three Areas of Interest (Figure 1b). When the AoIs are removed from the rest of the ground-truth and bathymetric LiDAR comparison points (Figure 5d—“Other points”), there is no linear correlation (R2 = 0.07; full regression data in Supplementary Table S2) between depth and the point cloud vs. ground-truth residuals. AoIs 1, 2 and 3 contained 604 (22.6%), 193 (7.2%) and 167 (6.2%) of the measured echo-sounding points (n = 2673), respectively. These three AoIs account for 96.7% of the residuals that had a magnitude of less than −0.5 m, noting that a negative error indicates that the UAV bathymetric LiDAR point cloud bed level is higher than the measured riverbed level, indicating an underestimation of depth. Echo-sounding points within AoI 1 (deep pool) had a mean average depth of 0.51 m, and a maximum depth of 1.309 m; mean average and maximum depths in AoI 2 were 0.42 m and 1.046 m, respectively; and in AoI 3 were 0.48 m and 0.87 m, respectively. Each of the AoIs was also analysed for linear trends, with the following R2 results: AoI 1 = 0.54; AoI 2 = 0.65; AoI 3 = 0.37.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot showing relationship between LiDAR residuals and water depth (measured by echo-sounder), segmented for (a–c) three identified Areas of Interest (AoIs) and (d) all other echo-sounder points within study area that weren’t within the user-defined AoIs. The three AoIs account for 96.7% of residuals that had a magnitude of less than −0.5 m. The colours of the points above match the colours of the AoIs as shown in Figure 1b.

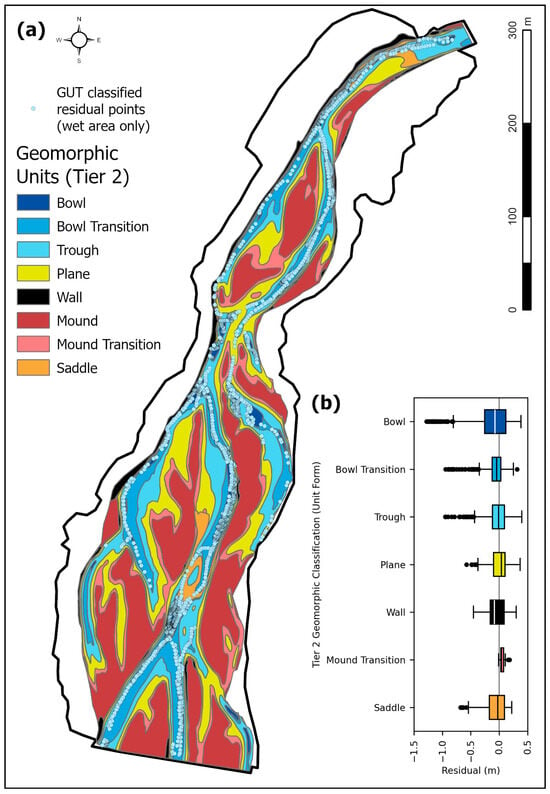

4.3. GUT Segmented Residuals

Ground-truth data from both the echo-sounder and RTK-GNSS were combined and classified based on the Geomorphic Unit (GU) they were located within. For this analysis, all GUs were thus part of the wet channel. Points that were within bowl GUs were characterised by the largest standard deviation of residuals (0.327 m) and a median of −0.074 m (Supplementary Table S3). Troughs had the second greatest standard deviation (0.198 m), with a median of −0.037 m. All the concave units (Bowl, Bowl Transition and Trough) were characterised by negative medians (depth underestimated) and exhibited a generally larger range of residuals compared to the plane, wall, mound and saddle unit forms. There were comparably few points (n = 11) classified as mound transitions; this is not surprising since this is a convex unit form that corresponds to bars that are typically aerially exposed. Planes and walls, corresponding to flatter, horizontal and vertical surfaces, had similar ranges (0.179 m and 0.191 m, respectively) but with medians of 0.037 m and −0.086 m, respectively. Saddles had a median of −0.027 m, and a comparable standard deviation to planar areas (0.179 m).

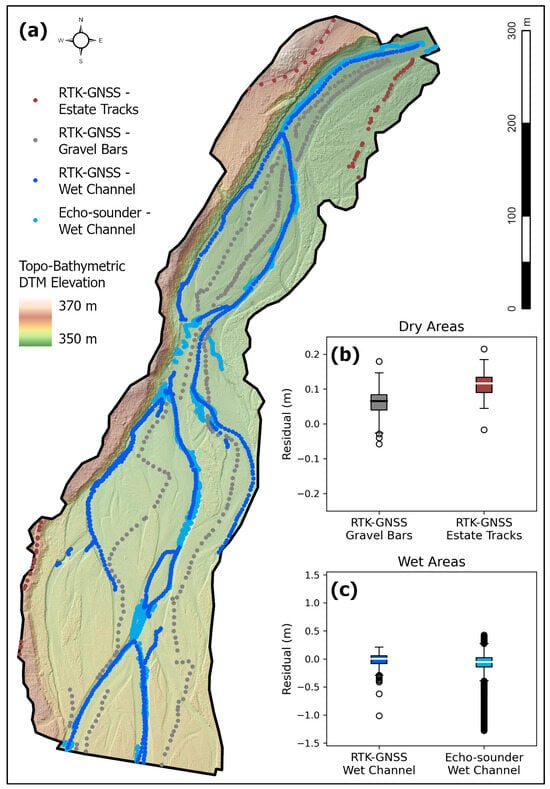

4.4. DEM Residuals to Ground-Truth Data

The ground-truth data was also used to evaluate the error associated with the point cloud to raster interpolation to produce the DEM. Figure 6 shows the distribution of errors for comparisons between the DEM and the four different types of ground truth data. Median errors for the RTK-GNSS observations of gravel bars, estate tracks and wet channel were 0.065, 0.116 and 0.002 m, respectively (Figure 7). This can be compared to the median errors for the same types of ground truth data with the point cloud comparison (Figure 3) of 0.061, 0.120 and −0.001 m. The differences between the standard deviations for the point cloud and DEM residuals are also similar and small in magnitude, with the differences between all RTK-GNSS ground truth data standard deviations being <0.01 m. For the echo-sounder observations, the median and standard deviation for the DEM residuals were −0.054 and 0.219 m, respectively. These correspond to median and standard deviations of −0.052 and 0.232 m, respectively, for the point cloud residuals. Overall, the calculated residuals were very similar between the point cloud and DEM comparisons, indicating that the interpolation is faithful to the original data with minimal additional distortions added (Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 6.

Point cloud residuals segmented by geomorphic units. (a) Spatial distribution of geomorphic units from independent June 2024 topographic survey with bathymetric corrections and (b) elevation residuals for points within wetted channel (August 2024) classified by corresponding geomorphic unit. Colours used in (b) use the same colour palette as (a).

Figure 7.

(a) Topo-bathymetric Digital Terrain Model (DTM) of the River Feshie (August 2024) and location of RTK-GNSS and echo-sounder ground-truth data points. (b,c) Elevation residuals for dry and wet areas, respectively, after interpolation to create DTM. Colours used in (b) and (c) use the same colour palette as the points in (a).

5. Discussion

This investigation assessed the YellowScan Navigator topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensor to survey a reach of the braided River Feshie, Scotland. In Section 5.1 we summarise the results and discuss the trends in the error analysis. In Section 5.2 we contextualise the results by comparing them to other remote sensing approaches to quantify riverscape topography and discuss the current limitations of this topo-bathymetric UAV LiDAR approach.

5.1. UAV Topo-Bathymetric LiDAR Errors

Overall, the vertical error analysis shows that there is a positive bias in the survey of dry topography and a negative bias in the survey of wet bathymetry (Figure 4). These differences in the direction of bias are consistent between error analysis that consider comparing the check data to the LiDAR point cloud (Figure 4) and the DEM derived from the point cloud (Figure 7). Positive bias in the comparison to dry topography is likely caused by one or more of three systematic errors in the sampling of the topography, both from check point and LiDAR point cloud survey. First, placement of the RTK-GNSS pole has a tendency to sample between gravel clasts rather than represent the average height of the topography [62]. Second, the LiDAR returns and associated point cloud processing is more likely to represent the top upper surface of gravel clasts, with less point representing the lower topography in between clasts. Third, the majority of the estate track RTK-GNSS points were along one side of the study area and may show a minor systematic error, However, the overall positive bias in dry topography is minimal and, as examined below, comparable to other topographic remote sensing techniques. It is acknowledged that this investigation focused upon vertical error assessment and not vertical and horizontal error assessment. The later could be achieved through the placement and positioning of ground control targets, with reflectance characteristics that enable their centroid to be identified in the LiDAR point cloud intensity attribute.

The assessment of wet topography errors indicated that deeper water was associated with higher residual errors (Figure 5). Area of Interest 3, which featured a deep pool, was associated with higher standard error (Supplementary Table S2). A spatially extensive assessment of all wet areas showed that channels that were characterised by bowls or bowl transitions, analogous to pool geomorphic units, had greater negative error residuals than other unit forms. The greater errors in deeper water, typically pools in the River Feshie, occur despite the relatively clear water; a Secchi disc was visible at the bottom of the deepest pool. The critical depth for signal loss from bathymetric LiDAR has been reported to occur around the measured Secchi depth [17,41], up to twice the Secchi depth [16] and even up to 4 metres [63]. However, it was less than this for our investigation. This is likely either an attribute of the demonstrator YellowScan Navigator system, with insufficient power to give deep water penetration, or it is associated with the river characteristics including surface water turbidity as water plunges down relatively steep riffles into pools or dark riverbeds in the deep pools.

The analysis of errors at Area of Interest 2, which was characterised by overhanging vegetation (Figure 1b and Figure 5, Supplementary Table S2), is important since it demonstrates another factor, in addition to deep water, which may cause a correlation between errors and physical attributes of the riverscape. The River Feshie study area is only sparsely vegetated and the majority of trees are <10 m in height and do not have canopies that overhang channels. There are, however, some areas where bank erosion has undercut vegetated banks and trees have collapsed into the channel, such as at Area of Interest 2. Vegetation complicates LiDAR from entering, and being returned from, the bed of the channel. It also likely contributes to difficulties reconstructing the water surface from water edge points [1,32], further contributing to greater error. Whilst areas of the study site that are characterised by deep water or overhanging vegetation are associated with greater error their spatial extent is limited and they could be surveyed with echo-sounding and then fused into the DEM if the higher vertical errors in these areas were deemed to be unacceptable.

5.2. Remote Sensing of Riverscape Topography

To assess how the vertical errors reported in this case study investigation compare to other techniques and instruments that have been used to quantify fluvial topography, Table 2 summarises the errors reported here and in a number of other investigations. The investigations that are summarised are intended to be representative of the different remote sensing equipment and techniques that are available to quantify fluvial topography. It is apparent that the residual errors that are reported for the application of the demonstration YellowScan Navigator for the River Feshie study area are comparable to other approaches; overall the sensor worked within the range of decimetre tolerances that are reported for surveying fluvial environments. However, the upper value for the RMSE for the wet bathymetry (Figure 4) is higher than that reported in other UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR investigations. This is because a large number of outliers with relatively large negative residuals are included in the error metric calculation. Frizzle et al. [4] compiled error assessment data from 57 topo-bathymetric LiDAR investigations and reported a median RMSE of 0.15 m, with lower and upper quartiles of approximately 0.10 m and 0.29 m respectively. Thus, within this broader assessment the RMSEs that we report fall within the interquartile range of other investigations.

Table 2.

Summary of a sample of investigations that have used remote sensing to quantify fluvial topography and assess associated vertical errors.

Although this investigation is limited to a single sensor applied to a single river, it is intended to add further evidence to assist those who wish to assess whether this sensor is suitable for application to the riverscape environment that they are interested in surveying. This investigation used a demonstration YellowScan Navigator unit. The current commercial production unit has a field-of-view that is twice as wide (40°) as the demonstration unit which will double that data acquisition rate. The production unit also includes an RGB camera, and there have been several other improvements notably the scanning pattern and data processing software. The current mass of the topo-bathymetric payloads, YellowScan Navigator being one of the lightest at 3.7 kg excluding battery, is still restricted by UAV payload mass limitations and flight endurance trade-offs. Enlarged survey extents and more efficient field logistics will be made possible with improving UAV options, including emerging solutions such as hydrogen powered UAVs that are capable of carrying these moderately heavy payloads for several hours at a time.

6. Conclusions

This investigation evaluated the application of the YellowScan Navigator topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensor to survey a braided riverscape that featured both wet and dry areas. The wet areas were inundated with water that was sufficiently clear for a Secchi disc to be visible when placed on the bed of the river in the deepest pools. The dry areas were predominantly composed of gravel. We assessed vertical errors using a variety of ground truth data, including RTK-GNSS observations of wet and dry areas, and an RTK-GNSS positioned echo-sounding survey of wet areas. We found:

- The sensor is capable of producing high density (62 points/m2) point clouds at the reach scale.

- Mean vertical errors, with associated standard deviations, were acceptable for dry gravel bars (0.06 ± 0.04 m, n = 237), shallow wet channels (−0.03 ± 0.12 m, n = 556) and deeper wet channels (−0.08 m ± 0.23 m, n = 2673).

- The spatial distribution of vertical errors in wet areas corresponds to geomorphic unit distribution, with units with a concave three-dimensional shape (bowls and troughs, which are associated with deeper water) having larger negative errors and wider ranges of residuals than units with planar or convex shapes.

Our investigation used a demonstration unit of the YellowScan Navigator that had a limited swath width and point density compared to the product that is now commercially available. Nevertheless, we were able to survey a 1 km length of the River Feshie’s braidplain during 4–5 h of field survey. Compared to alternative survey techniques that enable bathymetric reconstruction, such as the correction of SfM photogrammetry-derived point clouds or DEMs, or optical-empirical bathymetric mapping, UAV-based topo-bathymetric surveying requires considerably less time for post-processing. It remains important, however, to scrutinise the spatial distribution of vertical errors with ground truth data.

We optimised our survey by ensuring that data were acquired at low flow conditions. It is important that river characteristics and conditions are carefully considered during survey planning to minimise a bias in the spatial distribution of vertical elevation errors that is likely when inundated channels are deep or covered with overhanging vegetation. In our braided river application, however, these areas that are potentially associated with higher errors typically only account for a small proportion of aerial extent of the study area. Overall, the YellowScan Navigator LiDAR sensor is representative of a new generation of relatively lightweight sensors that are becoming commercially available and can be deployed on UAVs for reach-scale surveys of riverscape topography.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/drones9120872/s1. Table S1. Summary statistics for analysis of residuals between the ground-truth data subsets and UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR points within 0.1m of each ground truth point. Table S2. Linear regression parameter results from comparing echo-sounder depths versus LiDAR residuals, segmented for the three identified Areas of Interest. Table S3. Summary statistics for analysis of point cloud residuals, classified into geomorphic unit subsets. Table S4. Summary statistics for analysis of residuals between the ground-truth data and DTM interpolated from the UAV topo-bathymetric LiDAR point cloud.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.W. and C.J.M.; Data curation, C.J.M.; Funding acquisition, R.D.W.; Investigation, C.J.M., J.W., K.R. and R.D.W.; Visualization, C.J.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, C.J.M. and R.D.W.; Writing—review and editing, J.W. and K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by United Kingdom’s Research and Innovation—Natural Environment Research Council (UKRI-NERC), project NE/W006871/1.

Data Availability Statement

The processed point cloud, Digital Terrain Model, geomorphic unit classification and ground truth data are available in the University of Glasgow’s Enlighten data repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5525/gla.researchdata.2106.

Acknowledgments

Wildland are thanked for enabling access to the Glen Feshie estate.

Conflicts of Interest

J.W. works for Aetha, a commercial company that distributes the YellowScan Navigator in the United Kingdom. For this investigation, Aetha were contracted by the University of Glasgow to acquire and process the LiDAR point cloud dataset. The University of Glasgow independently acquired all ground truth data and undertook all other analyses.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| UAV | Unoccupied Aerial Vehicle |

| RTK-GNSS | Real-Time Kinematic Global Navigation Satellite System |

| SfM | Structure from Motion—photogrammetry |

| n | Sample size |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue (“true colour” imagery) |

| MBES | Multi-Beam Echo-Sounder |

| ADCP | Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler |

| UGCS | Universal Ground Control System |

| AoI | Area of Interest |

| KML | Keyhole Markup Language (file type) |

| TOLS | Take-Off and Landing Site |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| CAA | Civil Aviation Authority (United Kingdom) |

| OS | Ordnance Survey—national mapping agency for Great Britain |

| RINEX | Receiver INdependent Exchange—GNSS data format |

| DTM | Digital Terrain Model |

| GUT | Geomorphic Unit Tool |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| GU | Geomorphic Unit |

References

- Williams, R.; Brasington, J.; Vericat, D.; Hicks, D.M. Hyperscale terrain modelling of braided rivers: Fusing mobile terrestrial laser scanning and optical bathymetric mapping. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2014, 39, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, S.; Cui, X.; Feng, W. Remote sensing for shallow bathymetry: A systematic review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 258, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chone, G.; Biron, P.M. Assessing the relationship between river mobility and habitat. River Res. Appl. 2016, 32, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzle, C.; Trudel, M.; Daniel, S.; Noman, J. LiDAR topo-bathymetry for riverbed elevation assessment: A review of approaches and performance for hydrodynamic modelling of flood plains. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 2585–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, L.; Williams, R.; Boothroyd, R.J.; Hoey, T.B.; Tolentino, P.L.M.; MacDonell, C.; Guardian, E.; Reyes, J.; Sabillo, C.; Perez, J.; et al. Confined and mined, anthropogenic river modification as a driver of flood risk change. Npj Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassic, H.C.; McGwire, K.C.; Macfarlane, W.W.; Rasmussen, C.; Bouwes, N.; Wheaton, J.M.; Al-Chokhachy, R. From pixels to riverscapes: How remote sensing and geospatial tools can prioritize riverscape restoration at multiple scales. WIREs Water 2024, 11, e1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G.; Hauer, C.; Wieser, M.; Pfeifer, N. Topo-bathymetric LiDAR for monitoring river morphodynamics and instream habitats—A case study at the Pielach River. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 6160–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.D.; Lamy, M.-L.; Maniatis, G.; Stott, E. Three-dimensional reconstruction of fluvial surface sedimentology and topography using personal mobile laser scanning. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer, P.; Guerit, L.; Lague, D.; Crave, A.; Gourdon, A. Size, shape and orientation matter: Fast and semi-automatic measurement of grain geometries from 3D point clouds. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2022, 10, 1211–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Mudd, S.M. (Eds.) Developments in Earth Surface Processes. In Remote Sensing of Geomorphology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 23, ISBN 978-0-444-64177-9. [Google Scholar]

- Westaway, R.M.; Lane, S.N.; Hicks, D.M. Remote survey of large-scale braided, gravel-bed rivers using digital photogrammetry and image analysis. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleiter, C.J. Remote measurement of river morphology via fusion of LiDAR topography and spectrally based bathymetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, C.; Carter, W.; Shrestha, R.; Dietrich, W. Geodetic imaging with airborne LiDAR: The Earth’s surface revealed. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 086801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G.; Pfennigbauer, M.; Schwarz, R.; Pöppel, F. A decade of progress in topo-bathymetric laser scanning exemplified by the Pielach River dataset. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1/W1-2023, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Glennie, C.; Fernandez-Diaz, J.C.; Carter, W.E. Performance assessment of high-resolution airborne full-waveform LiDAR for shallow river bathymetry. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 5133–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G.; Pfennigbauer, M.; Schwarz, R.; Flener, C.; Wimmer, A.; Pfeifer, N. Concept and performance evaluation of a novel UAV-borne topo-bathymetric LiDAR sensor. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzel, P.J.; Legleiter, C.J.; Grams, P.E. Field evaluation of a compact, polarizing topo-bathymetric lidar across a range of river conditions. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G. A review of active and passive optical methods in hydrography. Int. Hydrogr. Rev. 2022, 28, 8–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.D.; Measures, R.; Hicks, D.M.; Brasington, J. Linking the spatial distribution of bed load transport to morphological change during high-flow events in a shallow braided river. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2015, 120, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinski, M.; Hazel, J.E., Jr.; Grams, P.E.; Kohl, K.; Buscombe, D.D.; Tusso, R.B. Channel Mapping River Miles 29–62 of the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, May 2009; Open-File Report, 2017-1030; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017; 35p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangen, S.G.; Wheaton, J.M.; Bouwes, N.; Bouwes, B.; Jordan, C.E. A methodological intercomparison of topographic survey techniques for characterizing wadeable streams and rivers. Geomorphology 2014, 206, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyzenga, D.R. Passive remote sensing techniques for mapping water depth and bottom features. Appl. Opt. 1978, 17, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flener, C.; Kos, A.; Pfeifer, N.; Briese, C. Seamless mapping of river channels at high resolution using mobile LiDAR and UAV-photography. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6382–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleiter, C.J. The optical river bathymetry toolkit. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejot, J.; Delacourt, C.; Piégay, H.; Fournier, T.; Trémélo, M.-L.; Allemand, P. Very high spatial resolution imagery for channel bathymetry and topography from an unmanned mapping controlled platform. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2007, 32, 1705–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleiter, C.J.; Roberts, D.A.; Marcus, W.A.; Fonstad, M.A. Passive optical remote sensing of river channel morphology and in-stream habitat: Physical basis and feasibility. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleiter, C.J.; Roberts, D.A.; Lawrence, R.L. Spectrally based remote sensing of river bathymetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2009, 34, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, P.E.; Lane, S.N.; Bergeron, N. Feature-based image processing methods applied to bathymetric measurements from airborne remote sensing in fluvial environments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2006, 31, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W.; Carrivick, J.L.; Quincey, D.J. Structure from motion photogrammetry in physical geography. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 40, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodget, A.S.; Carbonneau, P.E.; Visser, F.; Maddock, I.P. Quantifying submerged fluvial topography using hyperspatial resolution UAS imagery and Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, J.T. Bathymetric Structure-from-Motion: Extracting shallow stream bathymetry from multi-view stereo photogrammetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodget, A.S.; Dietrich, J.T.; Wilson, R.T. Quantifying below-water fluvial geomorphic change: The implications of refraction correction, water surface elevations, and spatially variable error. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, D.; Antoniazza, G.; Roncoroni, M.; Métra, F.; Lane, S.N. Heuristic estimation of river bathymetry in braided streams using digital image processing. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 3889–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.O.; Zhang, S.; Xia, L.; Luo, M.; Wu, J.; Awange, J. A novel reflectance transformation and convolutional neural network framework for generating bathymetric data for long rivers: A case study on the Bei River in South China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 127, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafarczyk, A.; Tos, C. The use of green laser in LiDAR bathymetry: State of the art and recent advancements. Sensors 2023, 23, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilldale, R.C.; Raff, D. Assessing the ability of airborne LiDAR to map river bathymetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, J.-S.; Le Coarer, Y.; Languille, P.; Stigermark, C.; Allouis, T. Geostatistical estimations of bathymetric LiDAR errors on rivers. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2010, 35, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzel, P.J.; Legleiter, C.J.; Nelson, J.M. Mapping river bathymetry with a small footprint green LiDAR: Applications and challenges. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonina, D.; McKean, J.; Benjankar, R.; Wright, C.W.; Goode, J.R.; Chen, Q.; Reeder, W.J.; Carmichael, R.A.; Edmondson, M.R. Mapping river bathymetries: Evaluating topobathymetric LiDAR survey. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2019, 44, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, M.O.M.; Malmquist, C.; Sticker, M.; Alfredsen, K. Quantitative evaluation of bathymetric LiDAR sensors and acquisition approaches in Lærdal River in Norway. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastdalen, L.; Stickler, M.; Malmquist, C.; Heggenes, J. Evaluating methods for measuring in-river bathymetry: Remote sensing green LiDAR provides high-resolution channel bed topography limited by water penetration capability. River Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez-Nicolas, M.; García-López, S.; Barbero, L.; Ruiz-Ortiz, V.; Sánchez-Bellón, Á. Applications of unmanned aerial systems (UASs) in hydrology: A review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, M.; Wiśniewska, M.; Stateczny, A.; Specht, C.; Szostak, B.; Lewicka, O.; Stateczny, M.; Widźgowski, S.; Halicki, A. Analysis of methods for determining shallow waterbody depths based on images taken by unmanned aerial vehicles. Sensors 2022, 22, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, G.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C.; Zhao, D.; Lin, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; et al. Adaptive model for the water depth bias correction of bathymetric LiDAR point cloud data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonell, C.J.; Williams, R.D.; Maniatis, G.; Roberts, K.; Naylor, M. Consumer-grade UAV solid-state LiDAR accurately quantifies topography in a vegetated fluvial environment. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2023, 48, 2211–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricope, N.G.; Bashit, M.S. Emerging trends in topobathymetric LiDAR technology and mapping. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 7706–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Yoshida, K.; Nishiyama, S.; Sakai, K.; Tsuda, T. Characterizing vegetated rivers using novel unmanned aerial vehicle-borne topo-bathymetric green LiDAR: Seasonal applications and challenges. River Res. Appl. 2022, 38, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xing, S.; He, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, Q.; Li, P. Evaluation of a new lightweight UAV-borne topo-bathymetric LiDAR for shallow water bathymetry and object detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, J.; Rumsby, B.; McVey, R. Monitoring and modelling morphological change in a braided gravel-bed river using high resolution GPS-based survey. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2000, 25, 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsby, B.; McVey, R.; Brasington, J. The potential for high resolution fluvial archives in braided rivers: Quantifying historic reach-scale channel and floodplain development in the River Feshie, Scotland. In River Basin Sediment Systems: Archives of Environmental Change; Maddy, D., Macklin, M.G., Woodward, J.C., Eds.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, J.; Langham, J.; Rumsby, B. Methodological sensitivity of morphometric estimates of coarse fluvial sediment transport. Geomorphology 2003, 53, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vericat, D.; Brasington, J.; Wheaton, J.; Cowie, M. Accuracy assessment of aerial photographs acquired using lighter-than-air blimps: Low-cost tools for mapping river corridors. River Res. Appl. 2008, 25, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, J.; Vericat, D.; Rychkov, I. Modeling river bed morphology, roughness, and surface sedimentology using high-resolution terrestrial laser scanning. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, E.; Williams, R.D.; Hoey, T.B. Ground control point distribution for accurate kilometre-scale topographic mapping using an RTK-GNSS unmanned aerial vehicle and SfM photogrammetry. Drones 2020, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.; Naylor, M.; Sinclair, H.; Black, A.; Williams, R.D.; Cuthill, C.; Gervais, M.; Dietze, M.; Smith, A. Sounding out the river: Seismic and hydroacoustic monitoring of bedload transport. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 3840–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, C.K.; Gordon, J.E. (Eds.) Scotland’s changing landscape. In Landscapes and Landforms of Scotland; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullett, P.R.; Leslie, C.; Mason, R.; Ratcliffe, P.; Sargent, I.; Beck, A.; Cameron, T.; Cowie, N.R.; Hetherington, D.; MacDonell, T.; et al. Woodland expansion in the presence of deer: 30 years of evidence from the Cairngorms Connect landscape restoration partnership. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 2298–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.F. A new procedure for gridding elevation and stream line data with automatic removal of spurious pits. J. Hydrol. 1989, 106, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Holland, D.A.; Longley, P.A. Investigating the spatial structure of error in digital surface models derived from laser scanning. In Proceedings of the ISPRS XXXIV, Commission 3/WG 3/W13, Dresden, Germany, 8–10 October 2003; pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.isprs.org/proceedings/XXXIV/3-W13/papers/Smith_ALSDD2003.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Wheaton, J.M.; Fryirs, K.A.; Brierley, G.J.; Bangen, S.G.; Bouwes, N.; O’Brien, G. Geomorphic mapping and taxonomy of fluvial landforms. Geomorphology 2015, 248, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llena, M.; Batalla, R.J.; Vericat, D. Inferring on fluvial resilience from multi-temporal high-resolution topography and geomorphic unit diversity. Geomorphology 2024, 465, 109412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, J.M. Uncertainty in Morphological Sediment Budgeting of Rivers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2008; 412p. [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot, J.; Gintz, A.; Kennel, P.; Doukkali, N.; Allouis, T. Advanced Bathymetric Survey Using the YellowScan Navigator: Applications in Erosion and Soil Movement Tracking. In International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Proceedings of the 3D Underwater Mapping from Above and Below—3rd International Workshop, TU Wien, Vienna, Austria, 8–11 July 2025; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2025; Volume XLVIII-2/W10-2025, pp. 13–18. Available online: https://isprs-archives.copernicus.org/articles/XLVIII-2-W10-2025/13/2025/isprs-archives-XLVIII-2-W10-2025-13-2025.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).