Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A finite element analysis method for vibration fatigue under multi-source dynamic loads is proposed, which has been validated through physical experiments: a finite element model has been established to quantify the vibration and impact loads on the special structure of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) wing pylon. The model has been validated through physical experiments, and the conditions of the physical experiments are completely consistent with the analysis model.

- The UAV structure fatigue life assessment method based on vibration fatigue analysis and damage accumulation theory considering model and load uncertainty is proposed: the comprehensive effects of vibration and impact loads on structural fatigue damage were taken into account to obtain the vibration fatigue characteristics of the connection area of the UAV wing pylon structure. Based on the theory of linear damage accumulation and considering model and load uncertainties, a correction coefficient was introduced to determine the converted fatigue life of the wing pylon, achieving conservative and reliable life prediction of the UAV wing pylon structure under the combined action of vibration and impact loads.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This work provides a novel solution for finite element analysis of UAV pylon connection structures under combined vibration and impact loading conditions.

- This approach enables efficient and precise determination of the fatigue life of UAV pylons subjected to multiple loading environments.

Abstract

(1) Background: The structural integrity of key components in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) mission systems is crucial for achieving performance goals. The installation environment of military and civilian UAV wing pylons is very complex, as they are subject to various complex vibration excitations. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct vibration fatigue analysis on the wing pylons of UAVs to ensure structural integrity and safe operation. (2) Method: This study is based on the experience of vibration fatigue design for military and civilian aircraft, and flight test data of HH-100 UAV, a specific wing pylon for UAV, was taken as the research object, and the vibration evaluation modeling method was studied. A vibration fatigue assessment model for wing pylons was established, and relevant fatigue failure and strain data were collected through experimental data to validate the vibration fatigue analysis model. A fatigue analysis model was used to conduct fatigue analysis on the design details of the wing pylon structure under multi-source dynamic loads and to determine the structural vibration fatigue characteristics. (3) Result: Based on the finite element method and using the power spectral density (PSD) of the load spectrum, analyses and calculations were carried out to obtain the stress distribution of the connecting structure under vibration and impact loads. Based on this, the fatigue weaknesses of the structure have been clearly identified. Subsequently, dynamic fatigue analysis was conducted to calculate the fatigue life of the structure. Using Miner’s damage accumulation theory and considering the uncertainty of calculations or the sensitivity of results to geometric simplification and PSD spectra, the nominal fatigue life of the pylon structure was obtained through conversion. (4) Conclusions: Using a fatigue analysis model validated through experiments, a comprehensive damage accumulation evaluation was conducted on the fatigue life of the wing pylon under external multi-source dynamic loads, and the vibration fatigue life of the wing pylon was obtained, which meets the design requirements of UAVs.

1. Introduction

The structural integrity of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) mission system mounting structure constitutes a critical component of the overall UAV structural integrity. The wing pylons of unmanned aerial vehicles endure multiple complex loads, including aerodynamic forces, random vibration loads, and takeoff/landing impact loads. Under these dynamic loads, cracks gradually develop at the joint interfaces until failure occurs, leading to fatigue failure that severely compromises mission completion and flight safety. A comprehensive fatigue failure analysis incorporating both random vibration loads and landing impact loads provides a more rational explanation and analysis of the fatigue failure mechanism in joint structures.

For vibration fatigue issues in military and civil aircraft structures, extensive and in-depth research has been conducted by numerous scholars on fundamental principles of aircraft structural vibration fatigue [1], estimation and prediction of vibration fatigue life for aircraft components [2,3,4], and vibration fatigue testing and monitoring [5,6,7]. Fatigue life under vibration environments has been determined for various structural elements such as wings, pylons, and landing gear [8,9,10,11,12]. Additionally, specialized studies have addressed vibration fatigue across multiple scales considering environmental factors like corrosion and temperature for composite materials [13,14] and alloys [15,16]. In contrast, current research on structural vibration fatigue in UAVs remains relatively limited [17]. Only a small number of scholars have conducted vibration fatigue analyses on specific UAV structures. These analyses have typically focused on identifying the critical vibration modes and fatigue-prone areas in UAV components, such as wings and pylons [18,19,20]. However, with the increasing importance and widespread use of UAVs in various applications, there are still many challenges and opportunities for further exploration, and more comprehensive research in this area is urgently needed.

In this paper, a finite element model of a wing pylon was established, taking the vibration and impact loads of the UAV as inputs. Based on the Dirlik model method and finite element analysis, the stress distribution and fatigue life of the wing pylon under vibration and impact loads were calculated. Meanwhile, the fatigue failure and strain values were obtained through vibration fatigue tests, further validating the finite element model and method. Based on the above work, the Miner damage accumulation theory was used to obtain the calculated fatigue life. Considering the dispersion and uncertainty of the analysis model and load, the vibration fatigue life of the wing pylon structure was converted, providing a data basis for evaluating the fatigue and structural integrity of the wing pylon. The data proves that the vibration fatigue life of the wing pylon structure meets the design requirements of the UAV.

2. Requirements and Methods

UAV wing pylons are mounted in a complex environment and must withstand multiple dynamic loads such as aerodynamic forces, random vibration, and takeoff and landing impacts in service. Conventional static fatigue analysis methods, based on the linear cumulative damage theory, assume that the amplitude of the load is independent of the number of cycles, making it difficult to capture the frequency domain coupling effects of random vibration loads and the transient energy concentration characteristics of landing impacts, resulting in inadequate explanations of the failure mechanisms for crack initiation and propagation in the multiaxial stress regime at the joint.

MIL-HDBK-516C [21], a United States Department of Defense military aircraft airworthiness standard, does not directly define the quantitative indicators of vibration fatigue, but through a collaborative framework of structural dynamics (Environment design-vibration) and load analysis (Repeated loads), a vibration fatigue management and control system covering the full life cycle is constructed. For the cruise phase, a random vibration load boundary based on power spectral density needs to be defined, with equivalent static loads computed. For landing impact, the stress response of the joint is analyzed by time-domain simulation. Based on this, a basic fatigue life analysis is carried out to verify design reliability. Combining fatigue failure analysis of random vibration loads and landing impact loads, the failure mechanism of the pylon joint structure can be revealed more scientifically.

Because the actual vibration environment is difficult to obtain, the vibration fatigue life assessment uses the analytical calculation method. Analytical methods can generally be divided into time-domain-based methods and frequency-domain-based methods. Time-domain analysis follows a specific counting criterion, performing cyclic statistical operations directly on the structural stress-time history or strain-time history. According to the results of cyclic statistics, combined with the selected damage model, S-N curve, and cumulative damage theory, the calculation of damage value is carried out, and then the fatigue life of the structure can be deduced from the S-N curve. The frequency domain analysis method uses spectral parameters to characterize the amplitude information of the response in the frequency domain and combines the S-N curve with cumulative damage theory to calculate fatigue life.

For the wing pylons, the fatigue analysis method based on the combination of time domain and frequency domain was adopted, and the fatigue life was calculated by the amplitude distribution method under random loading conditions. The commonly used model for the amplitude distribution method is the Dirlik model [22], whose core is to estimate the probability density function of rain flow cyclic stress amplitude by empirical formula, which estimates the probability density function of rain flow cyclic amplitude by empirical formula, and by combining the S-N curve, the number of cycles that the material can withstand at a specific stress amplitude can be determined, and then the cumulative damage of the structure under random vibration loads can be calculated by the Miner linear cumulative damage theory. When the cumulative damage reaches a certain extent, the structure will suffer from fatigue failure.

The Dirlik model stress spectrum probability density function expression is

where p(s) means the probability density function of the stress spectrum, s is the amplitude of the stress spectrum, m0 is the zero moment of the power spectral density function, Z is called the normalized amplitude, , and parameters d1, d2, d3, Q, R, and χm are coefficients related to the power spectral density moment of inertia, and they can be calculated as

where m1, m2, and m4 are the first, second, and fourth moments of the power spectral density function, respectively, and α2 is called the irregularity factor.

According to the linear damage accumulation theory, the fatigue damage degree of the dangerous part of the structure under multi-stage cyclic stress is

where D is the fatigue damage, ns is the actual number of cycles at the stress spectrum amplitude s, and Ns is the cycle life at the corresponding stress spectrum amplitude s.

When the stress spectrum is continuous, the number of cycles within the stress amplitude range (si, si + ds) in time t is

where vp is the number of stress cycles per unit time, .

Substituting Equation (2) into Equation (3), the cumulative fatigue damage over time t is

When the material of the structure is selected, assuming a power function model in the form of a double logarithm according to the S-N curve of the material, the fatigue damage of the dangerous part of the structure under multi-stage cyclic stress is

where k and C are both constant coefficients related to the fatigue properties of the material.

According to the fatigue damage definition in Equation (5), the fatigue life N is the time when the fatigue damage reaches 1, i.e., D = 1, and then the fatigue life is

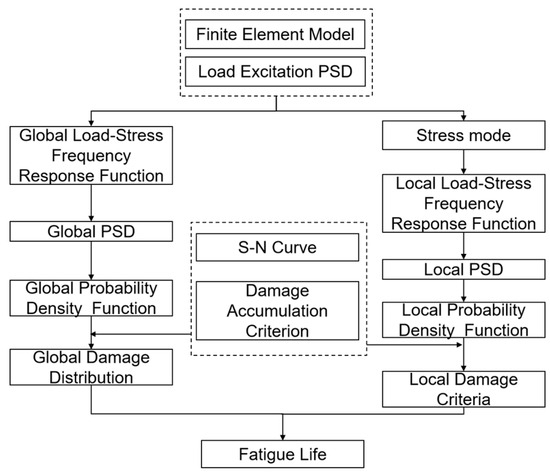

According to Equation (6), if the probability density function of the stress spectrum acting on the structure is known, the vibration fatigue life at that stress spectrum can be calculated from the material S-N curve, and the process of using the Dirlik model for vibration fatigue analysis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of the Dirlik model for vibration fatigue analysis.

3. Vibration and Impact Response Analysis

3.1. Establishment of a Finite Element Model

Due to the complex surface structure of the wing pylons, the vibration analysis of the entire wing pylons and their joint structures was carried out in order to facilitate the calculation. To simplify the joint surface, the complex and numerous tiny surfaces were removed, which were merged into larger curved surfaces without changing their shapes, facilitating the finite element mesh generation, and it was easier to more realistically mimic their load transfer processes by applying loads to pylons. For external pylons, unnecessary filets and round holes of non-stress concentration areas have been moved.

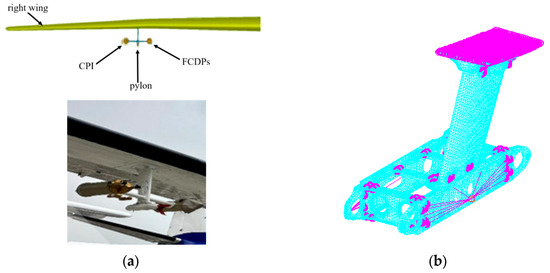

The wing pylons were divided into a grid and nodes, with 306,385 10-node tetrahedral solid elements (Tet10) and 539,699 nodes, and a convergence test was performed for the finite element model. The mesh of details, such as bolt hole edges, has been refined. The reinforced skin on the upper part of the tower is constrained by multiple points to simulate the connection between rivets and bolts on the lower wing surface of the aircraft wing. Multi-point constraints simulated bolted connections between the vertical transition beams and joints, bolted connections between vertical transition beams and horizontal box sections, and bolted connections between components within the horizontal box sections. Mass points were added at both ends and the bottom of the transition beam, with multi-point constraints establishing a connection to the horizontal box section to simulate the actual mounting conditions at both ends and the lower center of the transition beam, and applied inertial loads caused by a concentrated mass including two Fast Cloud Droplet Probes (FCDPs) with a mass of 2.5 kg and 9.5 kg mounted at the end of the left transition beam, and a Cloud Particle Imager (CPI) with a mass of 28.0 kg mounted at the end of the right transition beam. The resulting finite element model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Wing pylon with FCDPs and CPI. (a) Structure of wing pylon; (b) finite element model.

3.2. Vibration Response Analysis

Prior to conducting a vibration response analysis, it was first required to determine the vibration loads of the wing pylons. The UAV is propeller-driven, and because the UAV currently lacks relevant load provisions, the vibration loads are shown in Table 1 based on flight measurements by HH-100 (a civilian cargo fixed-wing UAV, and the prototype of the UAV in this paper), the implementation of flight measurement is achieved by installing sensors on the wing section to obtain the vibration response of the wing area. The flight measurement was carried out according to the cruise flight mission profile of the HH-100, and the data was statistically processed.

Table 1.

Vibration load spectrum parameters.

Equipment mounted on UAVs whose vibration environment is mainly induced by the operation of the propeller. Propellers generate complex vibration excitation during high-speed rotation, which acts on the equipment in different forms and intensities, posing challenges to the structural integrity and reliability of the equipment. In order to evaluate the mechanical properties of the equipment in such a complex vibration environment, a series of analysis work has been carried out with the aid of the advanced finite element analysis software MSC. Patran (v2019).

The load spectrum shown in Table 1 is converted into a power spectrum density curve, loaded in three directions: the x axis (heading), the y axis (vertical), and the z axis (lateral). The input power spectral density curve used for this study is shown in Figure 3, which combines various vibration regimes that the UAV may encounter during actual flight, providing accurate input conditions for subsequent frequency response analysis.

Figure 3.

Vibration power spectral density curve.

The setting of the structural damping ratio is a key parameter in frequency response analysis. Structural damping reflects the properties of energy dissipation of materials and structures in the process of vibration and has an important influence on the vibration response of structures. By detailed theoretical analysis and practical experience reference, the structural damping ratio is set to 0.02 according to the damping characteristics of the material itself to ensure that the analysis results can reflect the dynamic characteristics of the structure in the actual vibration environment. By conducting modal analysis on the structure, the natural frequencies of the first, second, third, and fourth order modes were extracted, which are 10.33 Hz, 17.94 Hz, 25.019 Hz, and 83.029 Hz, respectively.

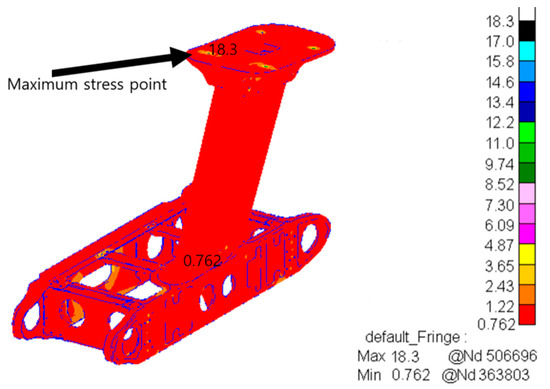

When an acceleration field was applied along the heading (X direction), in order to simulate the free vibration state of the structure in that direction, the X direction displacement constraint was released at the same time. The setting of such boundary conditions can more realistically reflect the actual forces on the equipment under heading vibration excitation. After completing the frequency response analysis, further random response analysis of the results was performed to obtain the root mean square stress distribution of the structure under random vibration loads, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Root mean square stress distribution diagram (heading).

A detailed analysis of these stress distributions shows that the maximum heading root mean square stress is 18.3 MPa, which occurs at the right forward bolted joint. The results show that the bolt joint is the weak point of the structure under the heading vibration excitation.

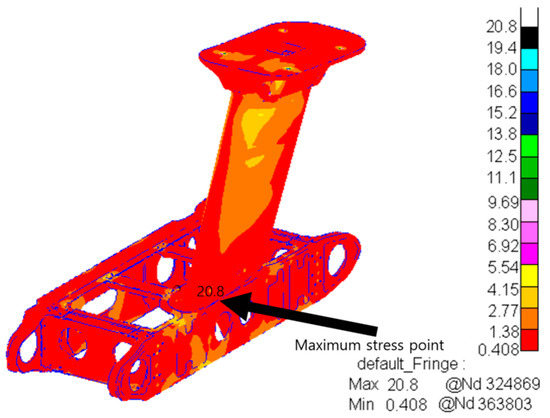

When an acceleration field was applied along the vertical (Y direction), the Y direction displacement constraint was similarly released to model the dynamic response of the structure to vertical vibration. A random response analysis was performed after completing the frequency response analysis, with the results shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Root mean square stress distribution diagram (vertical).

Analyses of these stress cloud charts show that the maximum vertical root mean square stress is 20.8 MPa, which occurs at bolted joints of the horizontal box. This indicates that the bolted joint may affect the structural connection reliability and overall stability, requiring further evaluation of its fatigue life and safety.

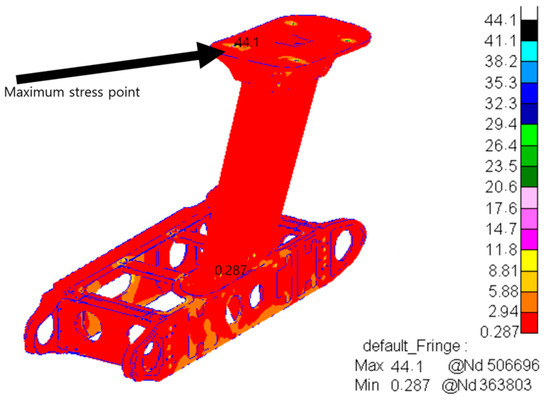

Applying an acceleration field along the lateral (Z-direction) direction and releasing the Z-direction displacement constraint simulates the free vibration state of the structure under lateral vibration. After completing the frequency response analysis and random response analysis, the results obtained are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Root mean square stress distribution diagram (lateral).

Through the analysis of these stress cloud charts, it can be found that the maximum lateral root mean square stress is 44.1 MPa, which occurred at the bolt hole on the right front of the joint. This value is significantly higher than the maximum root mean square stress of the heading and vertical directions, indicating that the bolt hole region is subjected to extremely large stresses under lateral vibration excitation and is the critical part of the structure for fatigue failure. In practical engineering applications, it is necessary to optimize the design or take effective vibration reduction measures to ensure safe and reliable operation of the equipment.

Through the vibration analysis and stress response analysis of the pylon structure in three directions, the stress distribution and weak points of the pylon structure under vibration excitation in different directions were found. Under the excitation of three directions, the weak parts of the structure are not completely the same. These results provide an important theoretical basis and technical support for structural optimization design, fatigue life assessment, and reliability analysis of pylons and help to improve the performance and safety of pylons in a complex vibration environment.

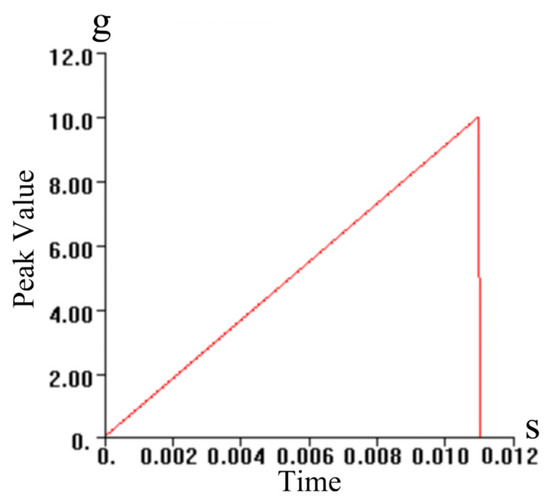

3.3. Impact Response Analysis

Precise determination of the impact loads on the wing pylons is the first step before conducting impact response analyses on the wing pylons. The accurate definition of impact loads is directly related to the reliability and effectiveness of subsequent impact response analysis results, which affects the accuracy of the performance assessment of pylon structures in impact environments. Peak sawtooth pulses were selected as the appropriate form of impact loading for functional impact and crash safety tests against the wing pylons. The rear peak sawtooth pulse has unique waveform characteristics and is able to more realistically simulate the impact conditions that the pylons may encounter during actual flight, providing representative and practical input conditions for subsequent analysis.

In order to make subsequent research and analysis on pylons and related structures more realistic and reflect their mechanical behavior and life characteristics under real impact loads, the impact load peak was eventually set to 10 g with a life analysis conclusion for similar models of pylons. The specific impact load peak is shown in Table 2, which provides clear and accurate data references for subsequent research efforts from a technical specification MIL-STD-810H “Environmental Engineering Considerations and Laboratory Tests” [23] issued by the US Department of Defense for the design and evaluation of aircraft structures.

Table 2.

Impact load spectrum parameters.

In order to simulate the impact loads on the structure in the actual environment, the impact load spectra in Table 2 are converted into power spectral density curves, loaded in the x (heading), y (vertical), and z (lateral) directions, respectively. The power spectral density curve serves as an important tool for characterizing impact loading characteristics, and its output data refers to the impact loading spectral curve shown in Figure 7. This curve reflects the distribution of power spectral density at different frequencies in detail, providing key inputs for subsequent frequency response analysis.

Figure 7.

Impact load spectrum curve.

At the same time, the structural damping ratio was set to 0.02, taking into account the energy loss of the structure during vibration. The reasonable selection of this parameter is essential to simulate the dynamic response of the structure. It can effectively reflect the energy dissipation caused by friction, material damping, and other factors inside the structure, thus making the analysis results closer to the actual situation. Through the above settings, frequency response analysis is conducted to obtain the response characteristics of the structure at different frequencies, laying the foundation for subsequent transient response analysis.

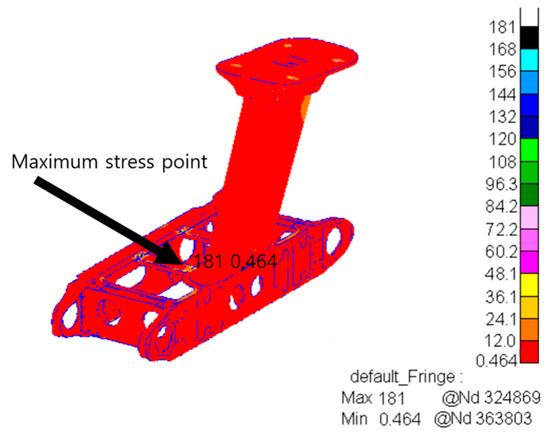

To simulate the free vibration state of the structure in that direction, the displacement constraint in the X direction was released when an acceleration field was applied along the heading (X direction). This means that the structure was free to change its displacement in the X direction without additional restraints. The transient response analysis of the finite element model was carried out to capture the dynamic stress variation process of the structure under impact loads. The stress distribution results obtained from the analysis are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Stress distribution diagram under heading impact.

From Figure 8, the maximum heading impact stress is 181 MPa and occurs at the horizontal box bolted joints. The results show that the bolted joints of the horizontal box are subjected to a large load under heading impact and are weak points of the structure in that direction. In the actual project, it is necessary to pay attention to the position, take strengthening measures to improve its impact resistance and ensure the safe operation of the structure.

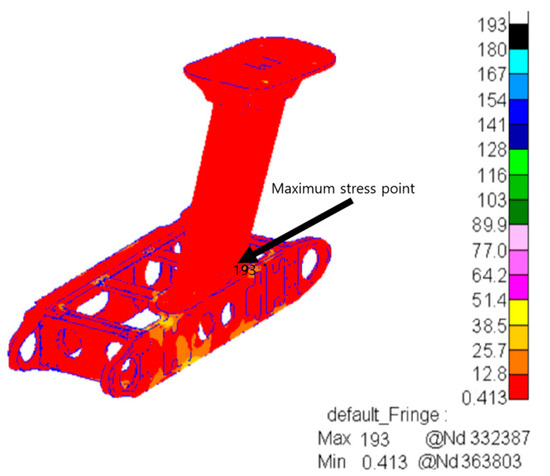

When an acceleration field was applied along the vertical (Y direction), the displacement constraint in the Y direction was similarly released, allowing the structure to vibrate freely in the Y direction. The transient response analysis of the finite element model was carried out to study the dynamic response characteristics of the structure under vertical impact loads. The result of the analysis is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Stress distribution diagram under vertical impact.

From the analysis of Figure 9, the maximum vertical impact stress is 193 MPa, which occurs at the bolted connection of the vertical transition beam to the horizontal box. These finding states that the bolted connection is prone to high stress concentrations under vertical impact loads and is a critical zone for the structure in the vertical direction. During design and maintenance, detailed structural optimization and strength checks shall be conducted for the area to prevent structural failure due to vertical impact.

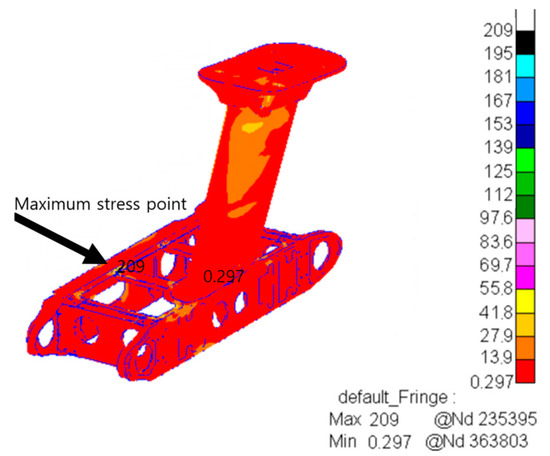

After applying an acceleration field along the lateral (Z direction) and releasing the Z direction displacement constraint, a transient response analysis of the finite element model was performed to study the dynamic behavior of the structure under lateral impact loads. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Stress distribution diagram under lateral impact.

From the analysis of Figure 10, the maximum lateral impact stress is 209 MPa, which occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box. This indicates that the horizontal box bolted joints also face higher loads under lateral impact loads and are important concerns for the structure in the lateral direction. In practical applications, it is necessary to further optimize the connection method and structural strength of the part to improve the fatigue damage resistance of the structure under lateral impact.

Through the analysis of the transient response of the structure in heading, vertical, and lateral directions, the maximum values of impact stress in each direction and their locations were identified. The maximum heading impact stress occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box, the maximum vertical impact stress occurs at the bolted junction of the vertical transition beam and the horizontal box, and the maximum lateral impact stress occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box, and they are the weak points of the vibration fatigue of the structure.

4. Vibration Fatigue Assessment

4.1. Fatigue Analysis Under Vibration Loads

In this paper, the fatigue life of the wing pylon was analyzed by the software MSC. Fatigue.

Setting the fatigue load spectrum is a key step in fatigue life analysis. Vibration loads were used as a fatigue load spectrum, with specific data referring to the vibration fatigue analysis PSD spectrum shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. The spectral diagram describes the variation in power spectral density of vibration loads with frequency in detail. Through the analysis of the PSD spectrum, the strength information of vibration loads at different frequencies can be obtained, which can provide accurate inputs for subsequent fatigue analysis to reflect the random vibration characteristics of the structure.

The properties of materials have a decisive influence on fatigue life. The material involved in this paper is 7050 aluminum alloy, which has high strength, good toughness, and corrosion resistance, and is widely used in aerospace fields. Its S-N curve describes the relationship between the stress and fatigue life of a material under cyclic loading, as shown in Table 3 [24]. By setting the S-N curve for the material, the MSC. Fatigue software was able to predict the fatigue life of the structure based on different stress levels.

Table 3.

The 7050 aluminum alloy mechanical properties.

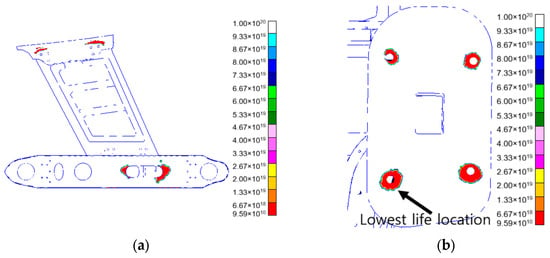

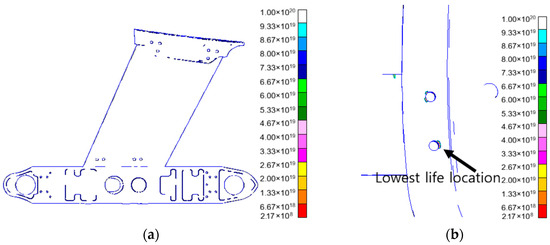

The life distribution under heading vibration was obtained by calculations from the MSC. Fatigue software, as shown in Figure 11. Figure 11a shows the life distribution of the structure under heading vibration from the left side view, and Figure 11b clearly indicates the location with the lowest life.

Figure 11.

Distribution diagram of vibration life (heading). (a) Distribution of vibration life; (b) minimum point of vibration life.

The results show that the minimum vibration life is 9.59 × 1010 s (2.66 × 107 h) and occurs at the bolted joints of the joint. The results show that the bolted joints in the joint section are prone to fatigue damage under heading vibration loads and are weak points of the structure in that direction. In practical engineering, it is necessary to focus on the part and take effective measures to improve its fatigue resistance, such as optimizing bolt connection design and increasing local structural strength.

The distribution of life under vertical vibration is shown in Figure 12. Figure 12a shows the life distribution characteristics of the structure under vertical vibration, and Figure 12b indicates the location with the lowest life.

Figure 12.

Distribution diagram of vibration life (vertical). (a) Distribution of vibration life; (b) minimum point of vibration life.

According to the results of the analysis, the minimum vertical vibration life was 4.28 × 1010 s (1.19 × 107 h), which occurred at the bolted joints of the horizontal box. This indicates that the bolted joints in the horizontal box are subjected to heavy load cycles under vertical vibration loads, which are prone to fatigue failure. During design and maintenance, detailed structural optimization and fatigue life assessment shall be conducted for the area to ensure the safety of the structure under vertical vibration.

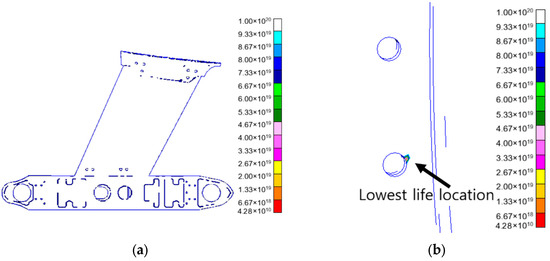

The life distribution under lateral vibration is shown in Figure 13. Figure 13a shows the life distribution of the structure, and Figure 13b identifies the lowest point of life.

Figure 13.

Distribution diagram of vibration life (lateral). (a) Distribution of vibration life; (b) minimum point of vibration life.

Analysis shows that the shortest lateral vibration life is 4.26 × 108 s (1.17 × 105 h), which occurs at the bolted joints of the joint sections. This further highlights the fatigue susceptibility of bolted joints in the joint section under lateral vibration loads. In practical applications, it is necessary to improve the connection method and structure of the part to improve its ability to resist lateral vibration fatigue.

In order to more visually assess the service life of the structure in actual flight, the number of flights under vibration loads in all directions was calculated with 2 h per one flight according to the flight profile of the UAV. The minimum lifetime under heading vibration load is 2.66 × 107 h, which can reach 1.33 × 107 flights; the minimum vertical vibration life is 1.19 × 107 h, and 5.95 × 106 flights can be made; the minimum lateral vibration life is 1.17 × 105 h, and 5.87 × 104 flights can be reached.

From these data, it can be seen that there are significant differences in the effects of vibration loads in different directions on the fatigue life of the structure. The minimum number of flights of a structure under lateral vibration loads means that in actual flight, lateral vibration may be one of the main factors leading to structural fatigue failure. Therefore, in the process of structural design and maintenance, the effect of lateral vibration on structural fatigue life should be given priority, and corresponding measures should be taken to improve and optimize it.

Through the application of MSC. Fatigue, fatigue life analysis software, to the fatigue life analysis of joints and transition beams, the fatigue life distribution of the structure under various directions of vibration and the location where the minimum life occurs are made clear. The minimum heading vibration life occurs at the bolted joints of the joint section, the minimum vertical vibration life at the bolted joints of the horizontal box, and the shortest lateral vibration life also occurs at the bolted joints of the joint section. These points are the weak points of the structure under vibration loads, which need to be focused on in the fatigue assessment analysis under impact loads.

4.2. Fatigue Analysis Under Impact Loads

When using MSC. Fatigue for fatigue life analysis, setting the fatigue load spectrum is a key prerequisite for accurate results. Impact loads were selected for this analysis as a fatigue load spectrum, which, due to its short acting time and large strength variations, can realistically reflect the sudden impacts encountered by the structure in practice, such as bird strikes, discrete source damage, etc. The load spectrum for impact fatigue is shown in Figure 7. Material properties of 7050 aluminum alloy are described as in Table 3. By setting the S-N curve of the material in the software, the fatigue life of the structure can be calculated based on the curve and the input impact load data, providing strong technical support for ensuring the safety and reliability of the structure.

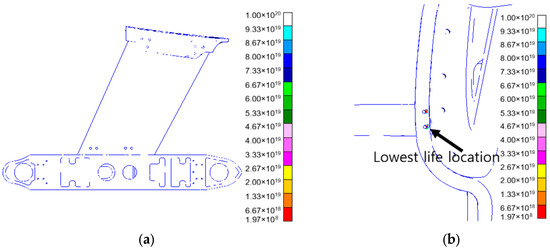

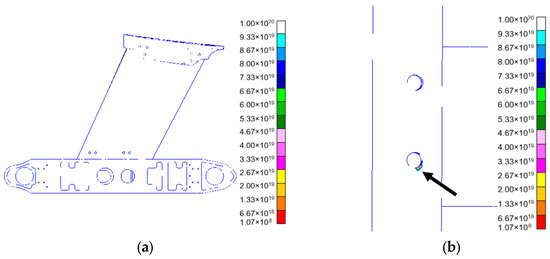

The life distribution under heading impact is calculated by MSC. Fatigue software, as shown in Figure 14. Figure 14a shows the life distribution characteristics of the structure under heading impact, enabling a visual view of the difference in length of life in different areas; Figure 14b identifies the location of the lowest life.

Figure 14.

Distribution diagram of impact life (heading). (a) Distribution of impact life; (b) minimum point of impact life.

The results show that the minimum heading impact life is 2.17 × 108 times, which occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box. The results show that the bolted joints of the horizontal box section are prone to fatigue damage under heading impact loads and are weak points of the structure in that direction. In practical engineering, it is necessary to focus on the part and take effective measures to improve its impact fatigue resistance, such as optimizing bolt connection design and increasing local structural strength.

The distribution of life under vertical impact is shown in Figure 15. Figure 15a shows the life distribution of the structure under vertical impact; Figure 15b’s vertical impact life minimum point diagram clearly shows where the life is lowest.

Figure 15.

Distribution diagram of impact life (vertical). (a) Distribution of impact life; (b) minimum point of impact life.

Based on the results of the analysis, the minimum vertical impact life is 1.97 × 108 times, also occurring at the horizontal box bolted joints. This indicates that the bolted joints of the horizontal box segment also suffer from large loads under vertical impact loads, which tend to cause fatigue failure. During design and maintenance, detailed structural optimization and fatigue life assessment shall be conducted for the area to ensure the safety of the structure under vertical impact.

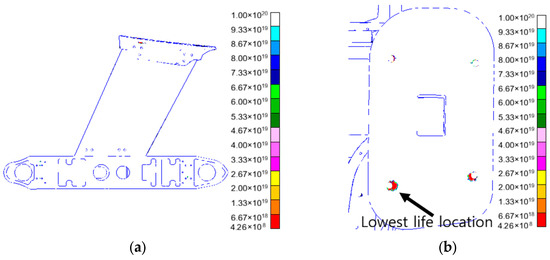

The life distribution under lateral impact is shown in Figure 16. Figure 16a shows the life distribution of the structure under lateral impact. Figure 16b defines the location of the lowest life.

Figure 16.

Distribution diagram of impact life (lateral). (a) Distribution of impact life; (b) minimum point of impact life.

Analysis showed that the minimum lateral impact life is 1.07 × 108 times, which occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box segment. This further highlights the fatigue susceptibility of bolted joints in the horizontal box under lateral impact loads. In practical applications, it is necessary to improve the connection method and structure of the part to improve its ability to resist lateral impact fatigue.

Based on the above analysis results, the minimum fatigue life under heading impact loading is 2.17 × 108 times, which occurs at the bolt joint on the right front of the joint section; the minimum fatigue life under vertical impact loading is 1.97 × 108 times, which occurs at the bolted junction of the horizontal box. The minimum fatigue life under lateral impact loading is 1.07 × 108 times, which occurs at the horizontal box bolted joints. It can be seen that there are some differences in the effect of impact loads in different directions on the fatigue life of the structure, but the bolt joints of the horizontal box section are common weak points under impact in multiple directions, requiring emphasis on strengthening.

In order to more visually assess the service life of the structure in actual flight, the fatigue life calculated here can be converted to the corresponding number of flights. Assuming one impact caused by landing per one flight according to the flight profile of the UAV, the course impact life can be reduced to 2.17 × 108 flights, the vertical impact life to 1.97 × 108 flights, and the lateral impact life to 1.07 × 108 flights. This conversion method provides an important reference for evaluating the durability of the structure in actual flight, helps to reasonably arrange the maintenance and replacement cycle of the structure, and ensures flight safety.

By using the MSC. Fatigue to analyze the impact fatigue life of the joints and transition beams, the distribution of the structural life under impact in all directions and the location where the minimum life occurs are identified. The minimum values of heading, vertical, and lateral impact life all occur at the bolted joints of the horizontal box section, which indicates that the position is a key weak point of the structure under impact loads and needs to be focused on and improved.

4.3. Vibration Fatigue Test Validation

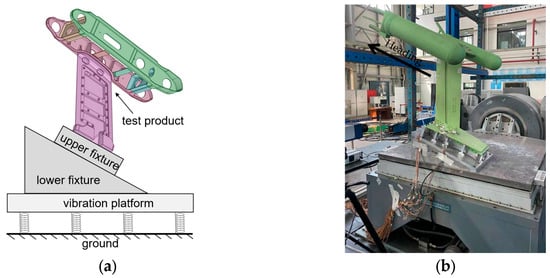

In order to verify the effectiveness of fatigue analysis methods, a vibration fatigue test was designed and implemented.

The installation of the vibration fatigue test is shown in Figure 17, where Figure 17a shows the schematic diagram of the test; the vibration fatigue test is conducted on a vibration platform. Considering the actual installation angle of the wing pylon, the upper and lower fixtures were fixed by bolts on the vibration platform. The lower fixture simulated the installation angle, while the upper fixture simulated the connection relationship and stiffness of the pylon installed on the wing, and Figure 17b shows the actual experimental installation. The size and structure of the test product is the same as the actual structure. There is a total of three test products, numbered # 1 to # 3.

Figure 17.

Vibration fatigue test. (a) Schematic diagram; (b) actual experimental installation.

The purpose of the test is to verify the analysis method and finite element model; therefore, the vibration load condition was selected for verification. The load spectrum applied in the test is the vibration load spectrum used for analysis, as shown in Figure 3. The sine sweep frequency test was carried out before the test, and then the vibration load spectrum was applied. Similarly to fatigue analysis, in the vibration fatigue test, vibration loads in three directions were applied separately. According to the results of fatigue analysis, strain gauges are attached to areas with high fatigue stress values, including edges for the bolt hole of the test product and upper fixture and edges for the bolt hole of the horizontal box.

During the test, the fatigue failure of the test product was recorded, as shown in Table 4. It can be seen that the relevant bolts are prone to vibration fatigue failure, which means that the fatigue stress values of the bolts are relatively high. At the same time, it also indicates that the corresponding bolt holes are also high-stress areas. However, under the combined effect of stress concentration on the threads, bolt fatigue failure occurs earlier.

Table 4.

Fatigue failure of the test product.

In order to effectively compare the test with the analysis, the highest strain value in the test was also recorded, as shown in Table 5. From Table 5, it can be concluded that when applying heading load, the maximum root mean square stress values of the three test products are close, indicating that the stress distribution of the three test products is relatively consistent. When vertical and lateral loads are applied separately, a similar situation also exists. However, due to the variability in fatigue testing, high stress values do not mean that the test product will fail first, and low stress values do not mean that the fatigue life of the test product is longer.

Table 5.

Highest strain values in the test.

Comparing the stress values obtained from the test with the analytical calculations, for the heading load condition, the error between the average stress obtained and the analytical value is 4.66%. For the vertical load condition, the error between the average stress obtained and the analytical value is 5.36%. For the lateral load condition, the error between the average stress obtained and the analytical value is 3.28%. It can be seen that the consistency between stress distribution and analysis calculation is good, and the stress values from analyses are higher than those from the test, indicating that the finite element analysis method is reasonable and conservative.

5. Discussion

For the vibration life and impact life obtained from the above analysis, the Miner fatigue damage accumulation theory may be used to integrate the effects of impact loads and random vibration loads. The Miner fatigue damage accumulation theory states that complete damage (also known as failure) occurs when the cumulative number of cycles of a part reaches N. Then when the number of stress cycles experienced by the part is n, some damage will occur. At the same time, assuming that the degree of damage caused by each cycle is consistent during this process, its damage rate can be expressed as n/N.

When a part is operating in an environment with multiple stress levels, each stress level causes the part to produce a damage rate ni/Ni, which can be predicted to occur if the sum of the damage rates is 1, i.e., when

failure is expected. Here, k denotes the number of stress levels.

According to the analysis results of the previous analysis, the number of cycles required to cause complete damage to parts at different stress levels were obtained, with N1 = 1.33 × 107 flights, N2 = 5.95 × 106 flights, N3 = 5.87 × 104 flights, N4 = 2.17 × 108 flights, N5 = 1.97 × 108 flights, and N6 = 1.07 × 108 flights, respectively.

Substituting this data into the Miner theoretical formula, when

failure will occur.

Ni is expressed as the number of landings and landings of the UAV. Because the structure experiences an impact and vibration load during each UAV takeoff and landing, the number of landings can be approximated as the number of stress cycles, i.e.,

Substituting the above equation into Equation (8),

Substituting the values of N1, N2, N3, N4, N5, and N6 into Equation (10) for calculation gives ni ≈ 5.8 × 104 flights.

Considering the uncertainty of calculations or the sensitivity of results to geometric simplification and PSD spectra, combined with experimental verification of vibration fatigue analysis, a coefficient K is applied to process the calculated fatigue life ni

where nc is the nominal fatigue life by considering the uncertainty of calculations or the sensitivity of results to geometric simplification and PSD spectra, ni is the calculated fatigue life, and K is a coefficient related to factors such as load, test piece, and test verification.

According to MIL-HDBK-516C [21], a United States Department of Defense military aircraft airworthiness standard, the value of coefficient K can be chosen as 8.0, which is the most conservative condition. According to Equation (11), nc can be obtained as 7.25 × 103 flights, meaning that UAV can perform 7.25 × 103 flights, the fatigue life of which meets the expected design target value, which is 103 flights. When the number of operations reaches this value, the structure is expected to fail according to the Miner fatigue damage accumulation theory.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the vibration fatigue of UAV wing pylons under the coupling of vibration loads and transient impact loads is studied, and the accurate prediction of the vibration fatigue life of pylons under complex dynamic loads is achieved by constructing an integrated analysis framework of “multi-source dynamic loading finite element model dynamic and nonlinear damage accumulation”, which provides a basis for the vibration life assessment of wing pylon for UAV.

In view of the complex mechanical environment of UAV wing pylons under the coupling of vibration loads and transient impact loads, a multi-source dynamic loading finite element model was constructed, and the finite element model was validated through actual physical experiments. Through the transient dynamic analysis, the superimposed effect of vibration loads and impact loads was quantified, and the critical areas were analyzed for local stress to determine the fatigue dangerous points under the multiaxial stress state.

Based on the dynamic load spectrum and damage accumulation theory, the vibration impact composite fatigue analysis model of UAV wing pylons was established. Using damage accumulation theory, the vibration fatigue life of UAV wing store pylons was calculated, and the high-precision life prediction of pylons under variable amplitude loads was achieved; the UAV can perform 7.25 × 103 flights. When the number of operations reaches this value, the structure is expected to fail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and Y.S.; methodology, L.S. and Y.S.; software, L.S.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, L.S.; investigation, L.S.; resources, L.S. and H.S.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and H.S.; visualization, L.S.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number No.52172387.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given by the College of Civil Aviation, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| FCDPs | Fast Cloud Droplet Probes |

| CPI | Cloud Particle Imager |

References

- Zorman, A.; Slavič, J.; Boltežar, M. Vibration fatigue by spectral methods—A review with open-source support. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 190, 110149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Xie, R.; Li, M. Fatigue Life Estimation Method for Random Vibration Based on Power Spectral Density Segmentation. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2024, 45, 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Baktheer, A.; Pan, Y.; Aldakheel, F. Fatigue life prediction under random vibrations: An acceleration framework combining scale factor analysis and critical distance theory. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 140, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dang, H.; Li, B. Prediction of Aircraft Surface Noise in Supersonic Cruise State. Aerospace 2023, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhu, S.; He, Y.; Xu, W. Notch fatigue behavior of a titanium alloy in the VHCF regime based on a vibration fatigue test. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 172, 107608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffa, A.; Palmieri, M.; Morettini, G.; Zucca, G.; Crocetti, F.; Cianetti, F. Development and validation of a low-cost device for real-time detection of fatigue damage of structures subjected to vibrations. Sensors 2023, 23, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Lu, S.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, W.; Ma, C.; Wang, X. Tensile and vibration fatigue monitoring of composite laminate bolted joints with local enhancement using buckypaper sensors. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, S.; Shu, P.; Lv, R.; Kong, L. Identification of excitation and modal frequencies of wing rib beams using fiber bragg grating sensors: Experimental characterization and comparative simulation analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3126, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Gao, W.; Ankay, B.; Li, F.; Zhang, C. Aeroelastic analysis and flutter control of wings and panels: A review. Int. J. Mech. Syst. Dyn. 2021, 1, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyungi, K. Fatigue Analysis of External Fuel Tank and Pylon for Fixed Wing Aircraft. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D.; Li, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, L.; Qiao, J.; Zhao, J. Structural optimization and fatigue life analysis of landing gear upper lock. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2403, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Q.B.; Wang, X. Fatigue Life Prediction of Flap Safety Pins for Civil Aircraft. In Proceedings of the Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers(SPIE), San Francisco, CA, USA, 31 January–2 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Sun, G.; Hou, J.; Li, H. Prediction of Vibration Fatigue Life of Fiber Reinforced Composite Thin Plates with Functionally Graded Coating under Base Random Excitation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 200, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Chen, M.; Sha, Z.; Cai, D.; Jiang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, G.; Wang, X. High-cycle Random Vibration Fatigue Behavior of CFRP Composite Thin Plates. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, H. Experimental Study on Vibration Fatigue Behavior of Aircraft Aluminum Alloy 7050. Materials 2022, 15, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, C.; Lv, J.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, N.; Li, L. Experimental study on the influence of welding structure details of TC4 titanium alloy under thermo-vibration coupling environment on vibration fatigue life. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2730, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Park, H.S.; Seo, S.W.; Kwag, D.-G. Design and Experiment of a Passive Vibration Isolator for Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.R.; Balasubramanian, E.; Arunkumar, P.; Sajal, C.B. Optimization of UAV Structure and Evaluation of Vibrational and Fatigue Characteristics Through Simulation Studies. Int. J. Simul. Multidiscip. Des. Optim. 2021, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Yan, H.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Random Vibration Fatigue Analysis of Rotor UAV Folding Propeller Hub. Intern. Combust. Engine Part 2024, 07, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Random Vibration Fatigue Analysis of UAV Engine Support Based on Steinberg Method. Mach. Build. Autom. 2021, 50, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Clothier, R.A.; Palmer, J.L.; Walker, R.A.; Fulton, N.L. Definition of an Airworthiness Certification Framework for Civil Unmanned Aircraft Systems. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, G.; Kayran, A. Implementation of Dirlik’s Damage Model for the Vibration Fatigue Analysis. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 21, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Defense. Environmental Engineering Considerations and Laboratory Tests, MIL-STD-810H; US Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 576–578.

- YS/T 1629.1-2023; Wrought Aluminium Alloy Plates and Sheets for Aviation Products-Part 1:7050T7451 Plates. Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).