A Quality Evaluation Method for Drone Swarm Command and Control Networks Based on Complex Network

Highlights

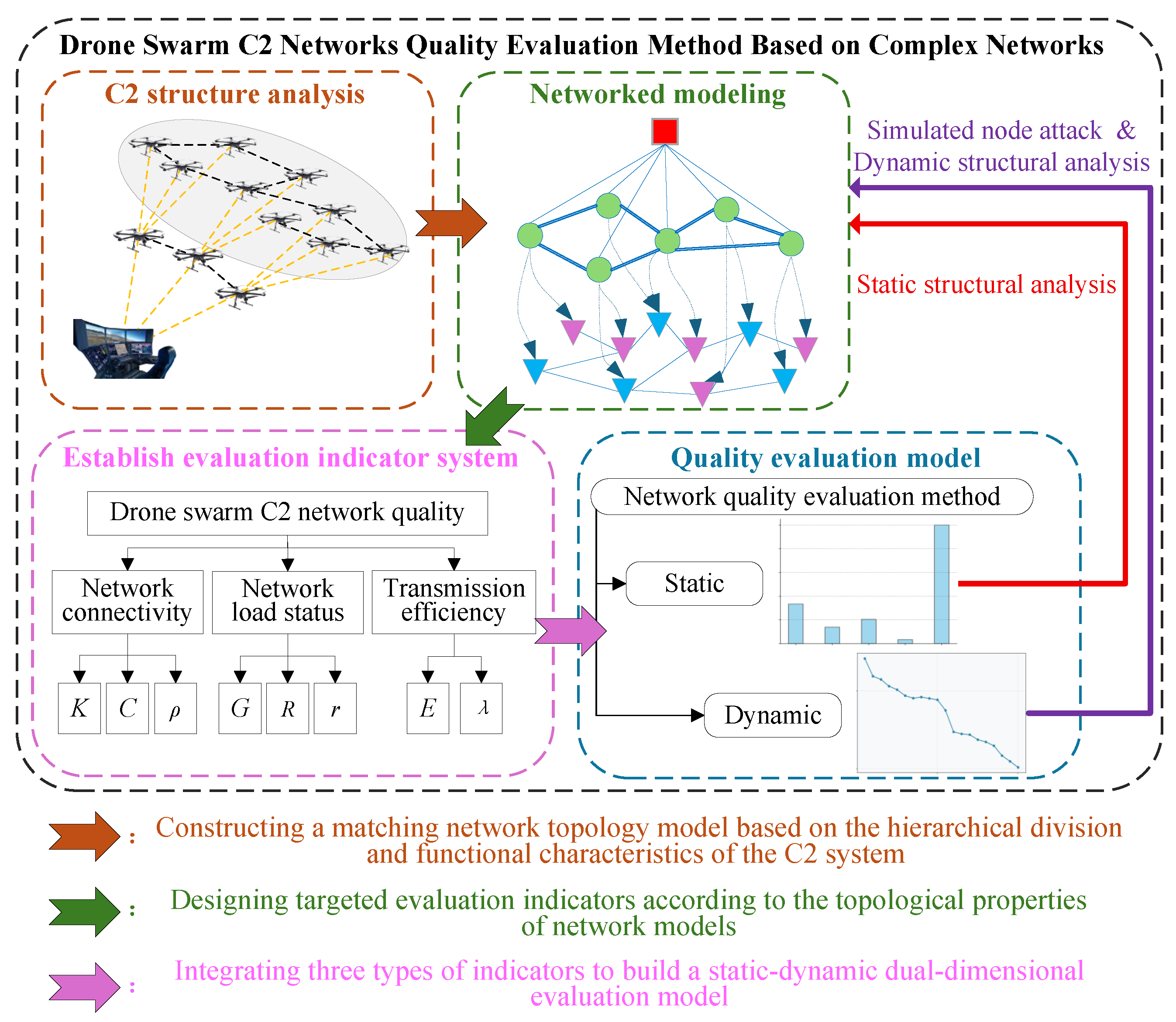

- A network modeling and quality assessment method for drone swarm command and control (C2) systems based on complex networks has been proposed. This method effectively evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of drone swarm C2 structures as well as their mission adaptability from a topological perspective. The evaluation framework can serve as a reference for analyzing and evaluating other combat systems.

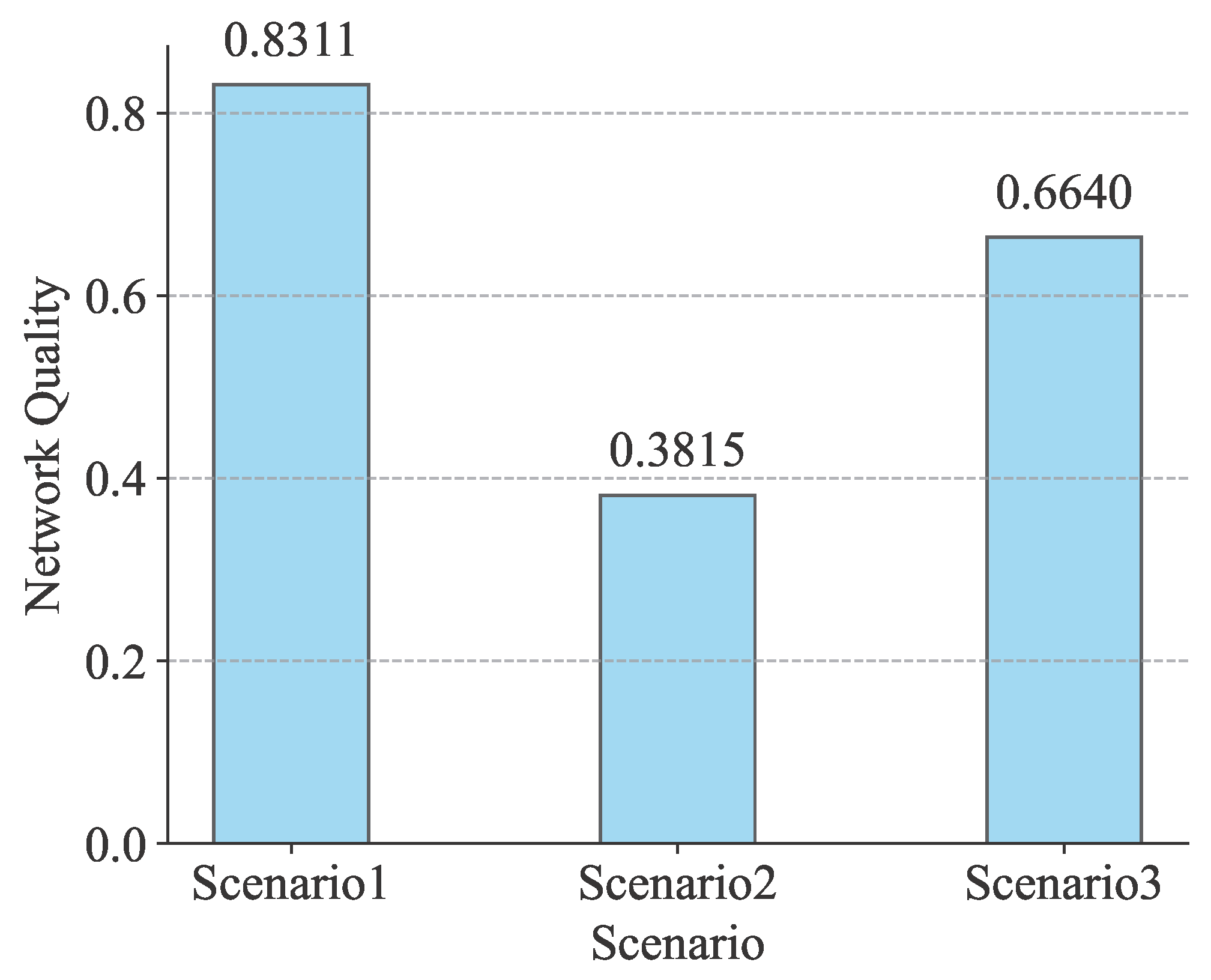

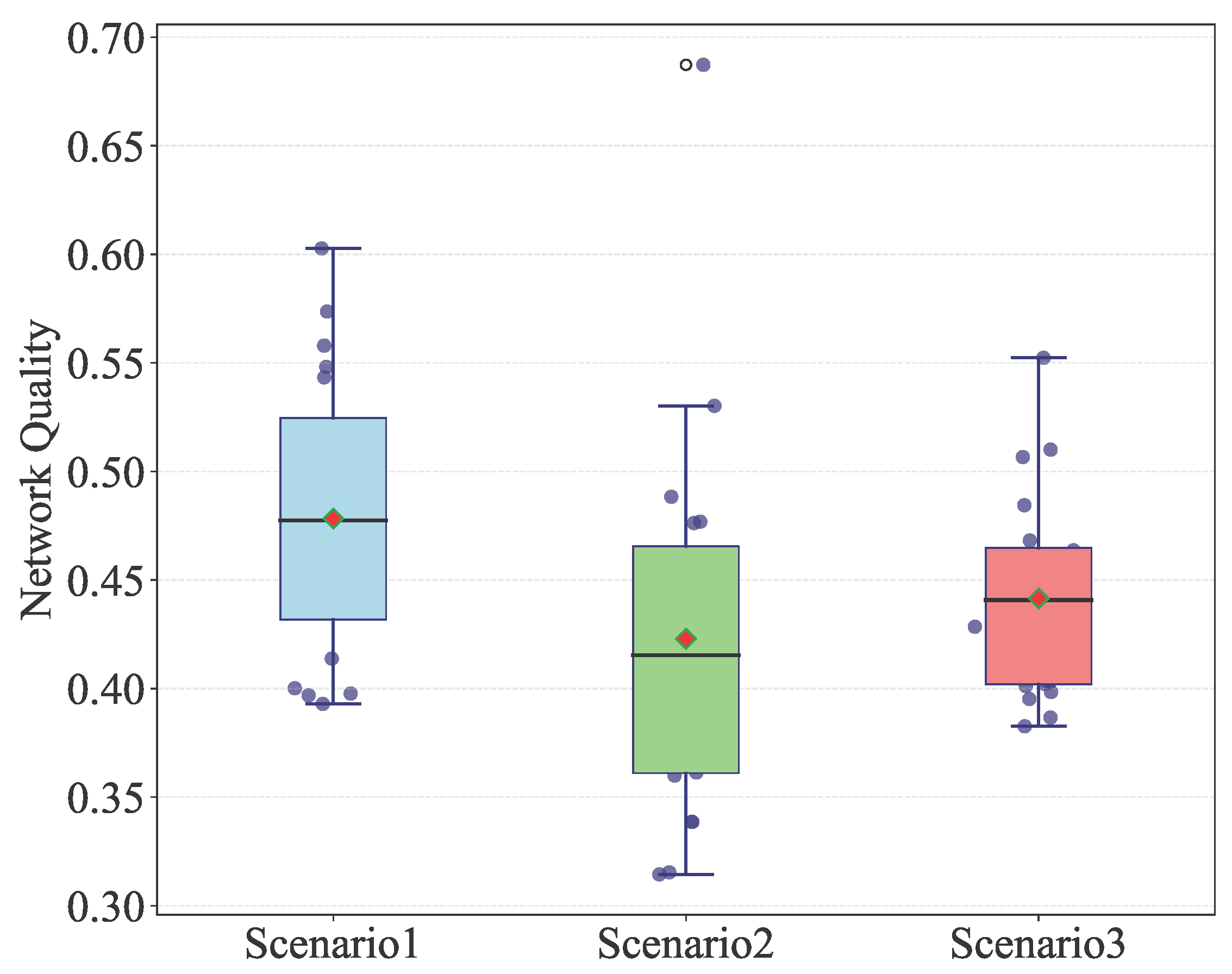

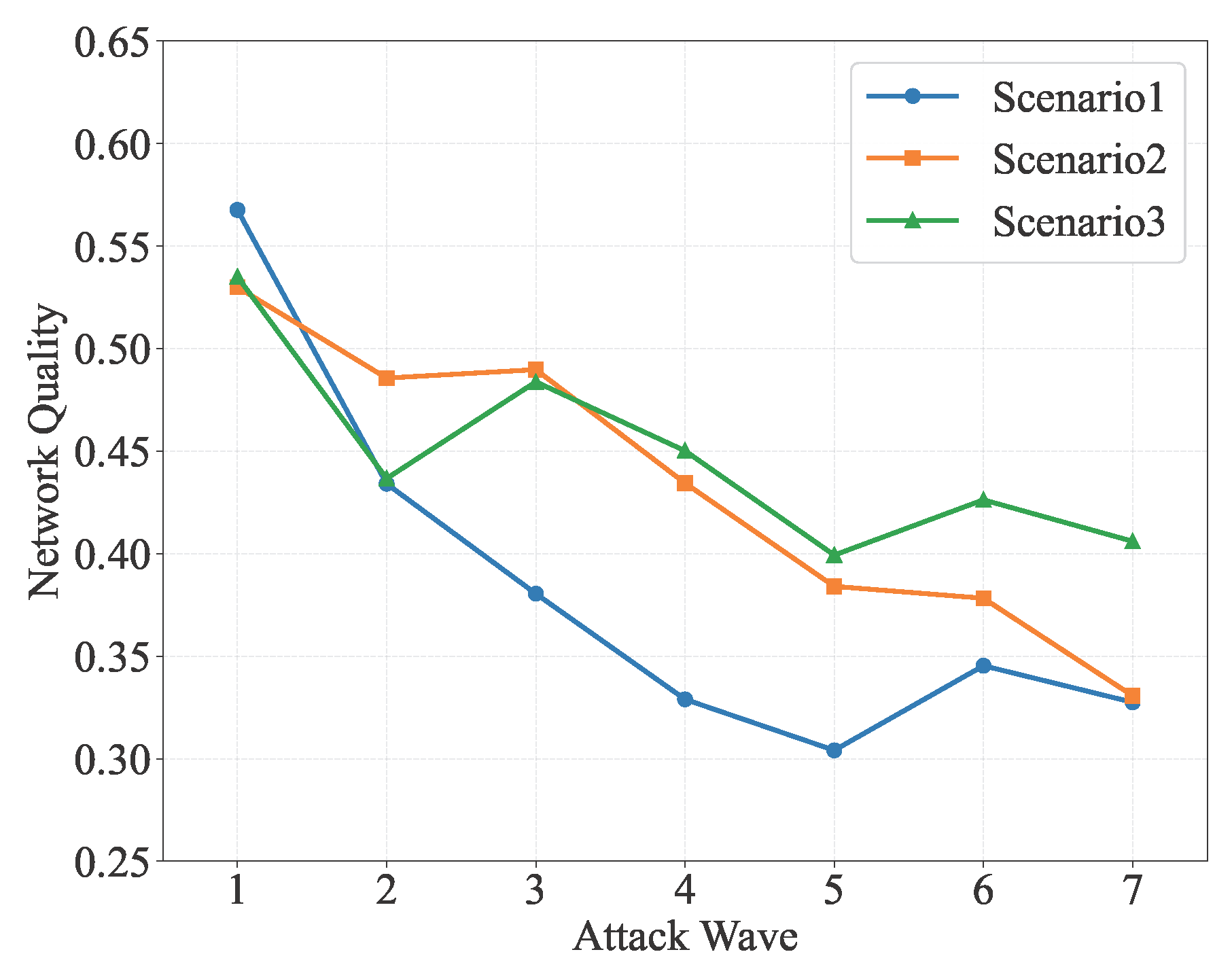

- Taking same-scale networks with different C2 structures as the basis for case analysis, this study demonstrates that the three types of distributed C2 structures each have their own advantages and disadvantages under different scenarios, such as static scenarios, random attacks, and targeted attacks. The dynamic network evaluation further demonstrates the universality of the evaluation method for networks with different structures, which can be used to guide the design of C2 system architectures.

- Complex networks can accurately characterise the structure of the drone swarm C2 system. Through network modeling of the drone swarm C2 system, complex network theory can be used to effectively analyze the system. The method can be applied to research on other complex combat systems.

- The Leader–Follower-based network exhibits good performance in terms of static structure and under random attacks, but has the worst performance under targeted attacks. It is suitable for long-endurance, long-range tasks such as security patrols and reconnaissance surveillance, as well as large-scale deployment scenarios, but not for combat missions involving high confrontation. Although the BA network and ER network have relatively poor performance in terms of static structure and under random attacks, they perform better under targeted attacks; in particular, the ER network structure is most suitable for high-confrontation tasks.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Motivations

1.3. Contributions

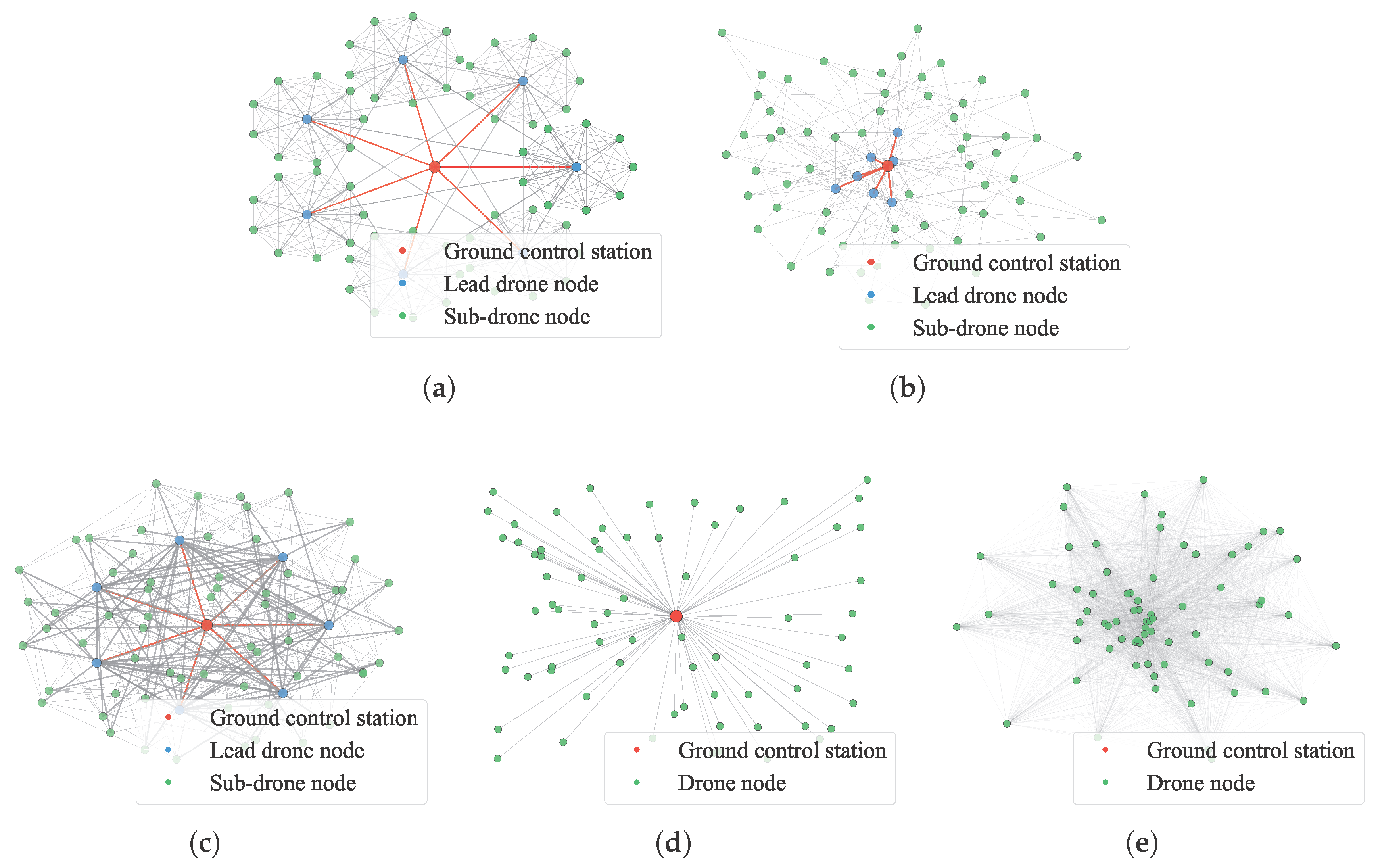

- Corresponding network models are constructed respectively for the centralized, distributed, and hierarchical drone swarm C2 structures. For the hierarchical C2 structure, three network models—based on leader–follower, BA scale-free network, and ER random network—are proposed, which accurately characterize the structural features of the drone swarm C2 system.

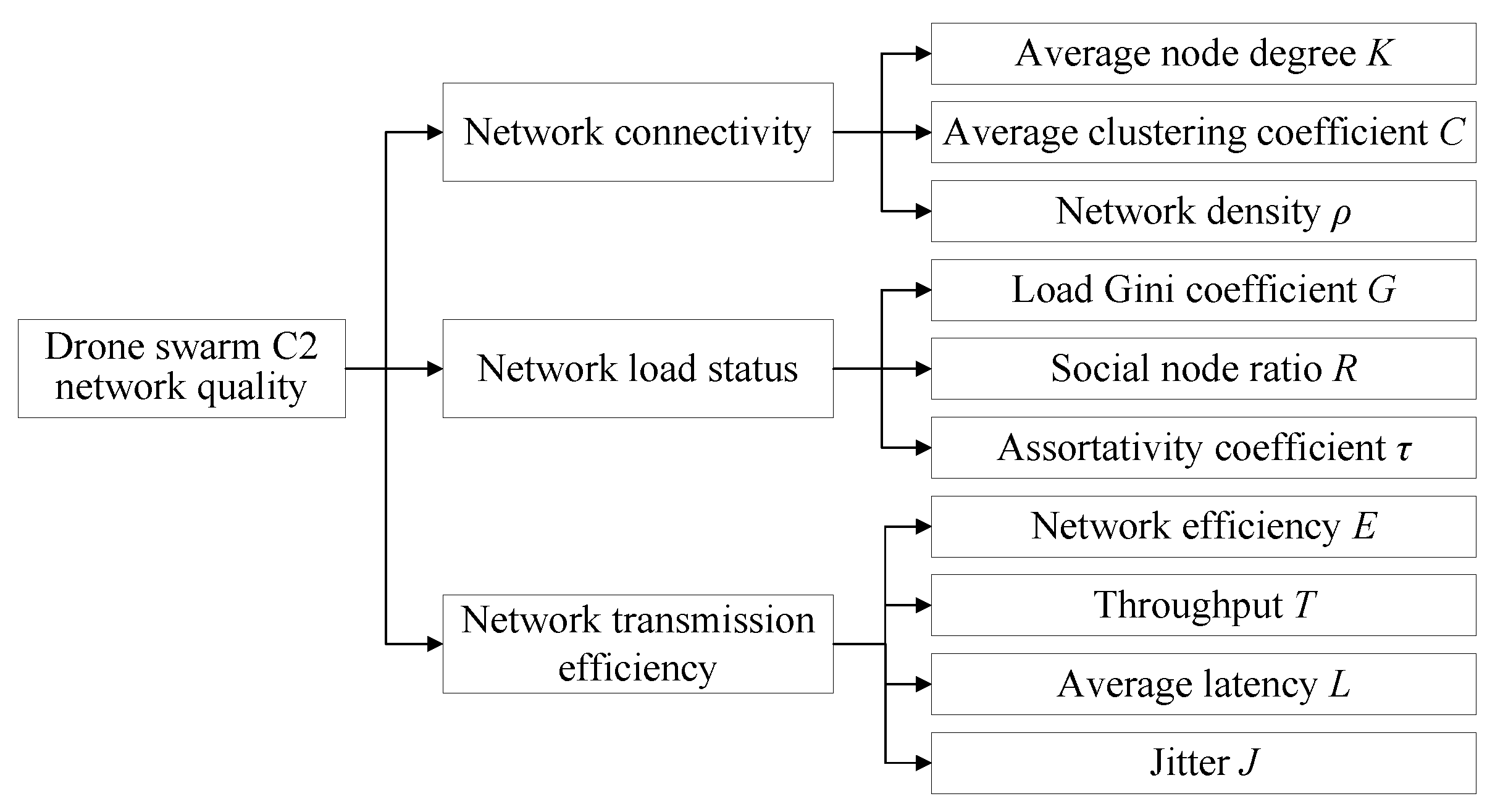

- Combining the characteristics of the drone swarm C2 system, an evaluation indicator system for drone swarm network quality is established, which comprehensively reflects the network topological structure of the drone swarm C2 system.

- A drone swarm C2 network quality evaluation model based on complex networks is constructed, and an evaluation method that considers both the static and dynamic aspects of the C2 system is proposed. This enables a comprehensive evaluation of the structural performance of the drone swarm C2 system.

- Through evaluation experiments on the quality of drone swarm C2 networks with different structures under the same scale, the feasibility and effectiveness of the evaluation method are verified, and the mission adaptability of different C2 structures is analyzed.

2. Network Modeling Method

2.1. Structure of the Drone Swarm C2 System

2.2. Drone Swarm C2 Network Modeling

3. Evaluation Model

3.1. Network Quality Evaluation Indicator System Based on Topological Structure

3.1.1. Network Connectivity

3.1.2. Network Load Status

3.1.3. Network Transmission Efficiency

3.2. Drone Swarm C2 Network Quality Evaluation Method

3.2.1. Static Evaluation Method

| Algorithm 1 Evaluation for Drone Swarm C2 Network Quality |

| Require: Evaluation scenarios Ensure: Static evaluation value

|

3.2.2. Dynamic Evaluation Method

| Algorithm 2 Dynamic Evaluation for Drone Swarm C2 Network Quality |

| Require: Evaluation scenarios, Attack types = {Random, Malicious} Ensure: Comprehensive dynamic evaluation value |

4. Case Verification and Analysis

4.1. Case Network Modeling

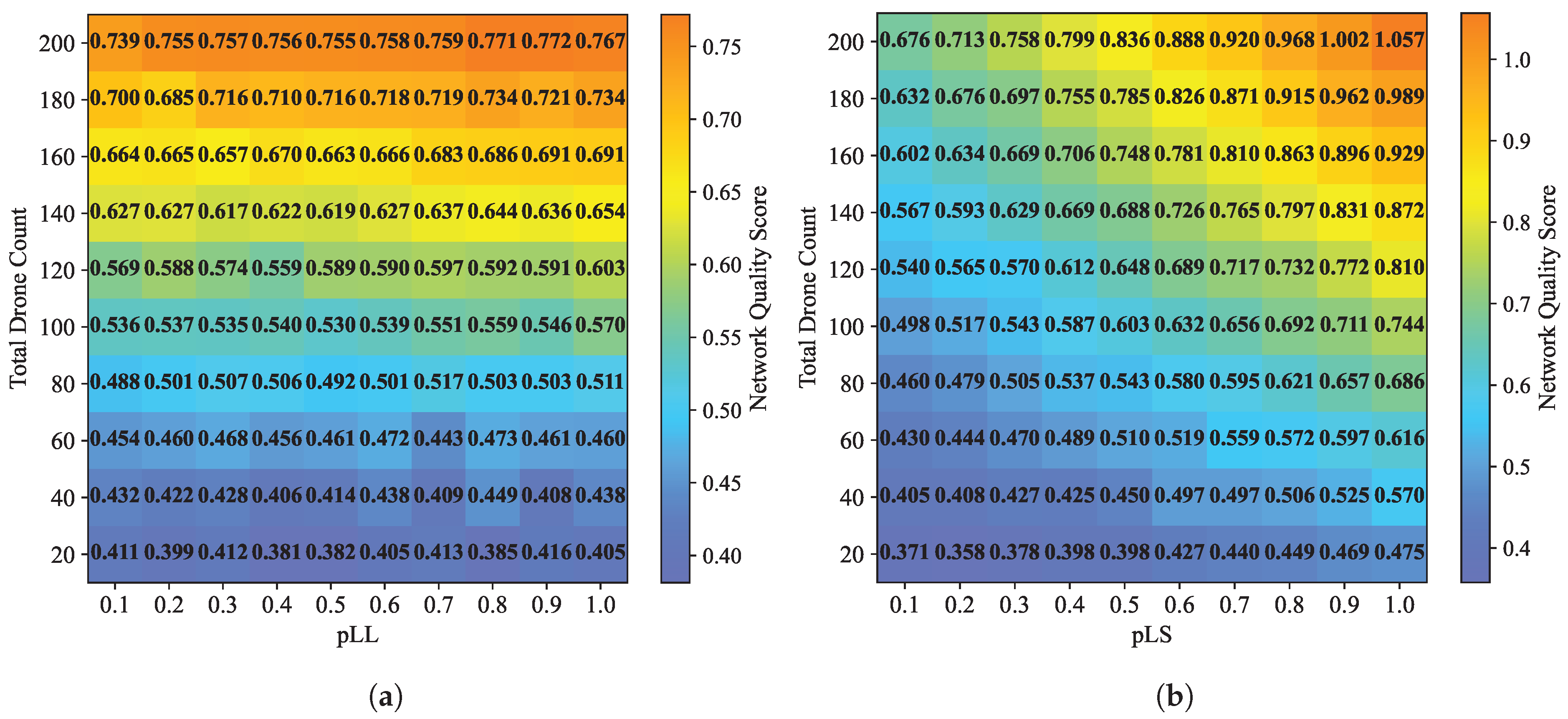

4.2. Static Evaluation

4.3. Dynamic Evaluation

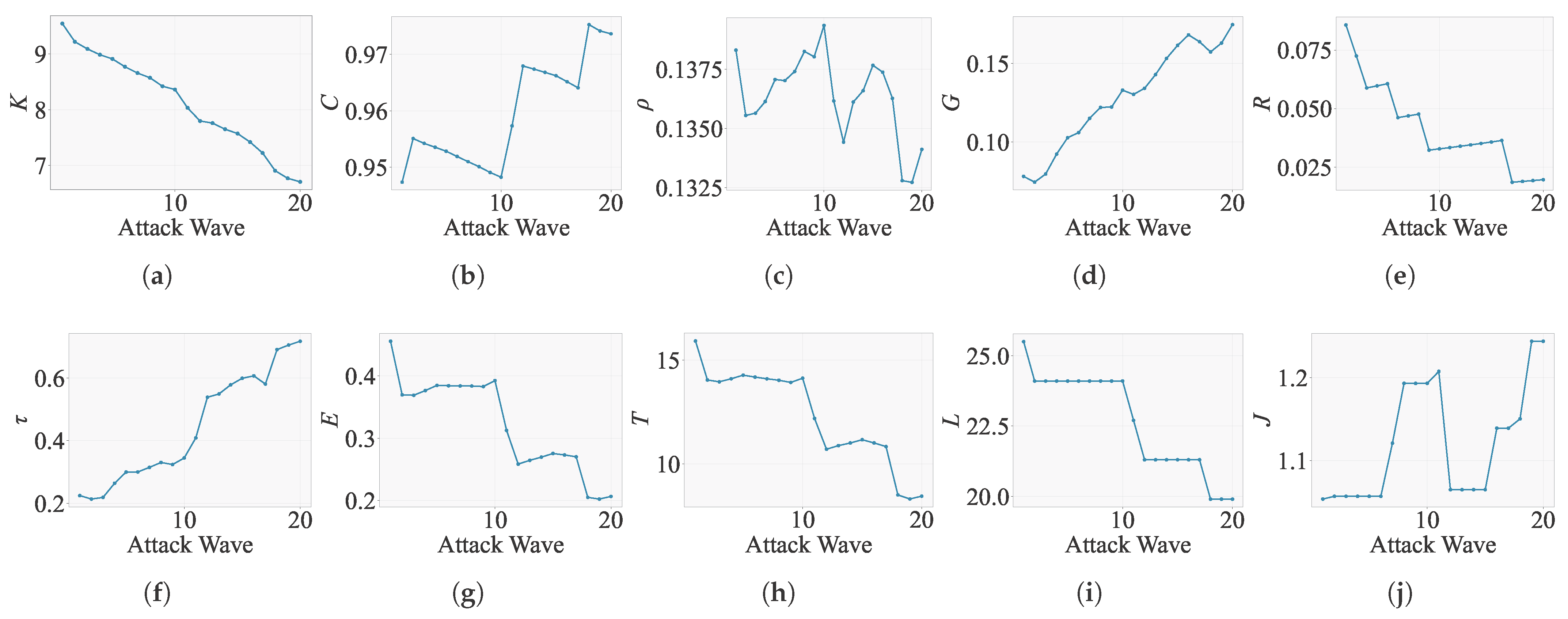

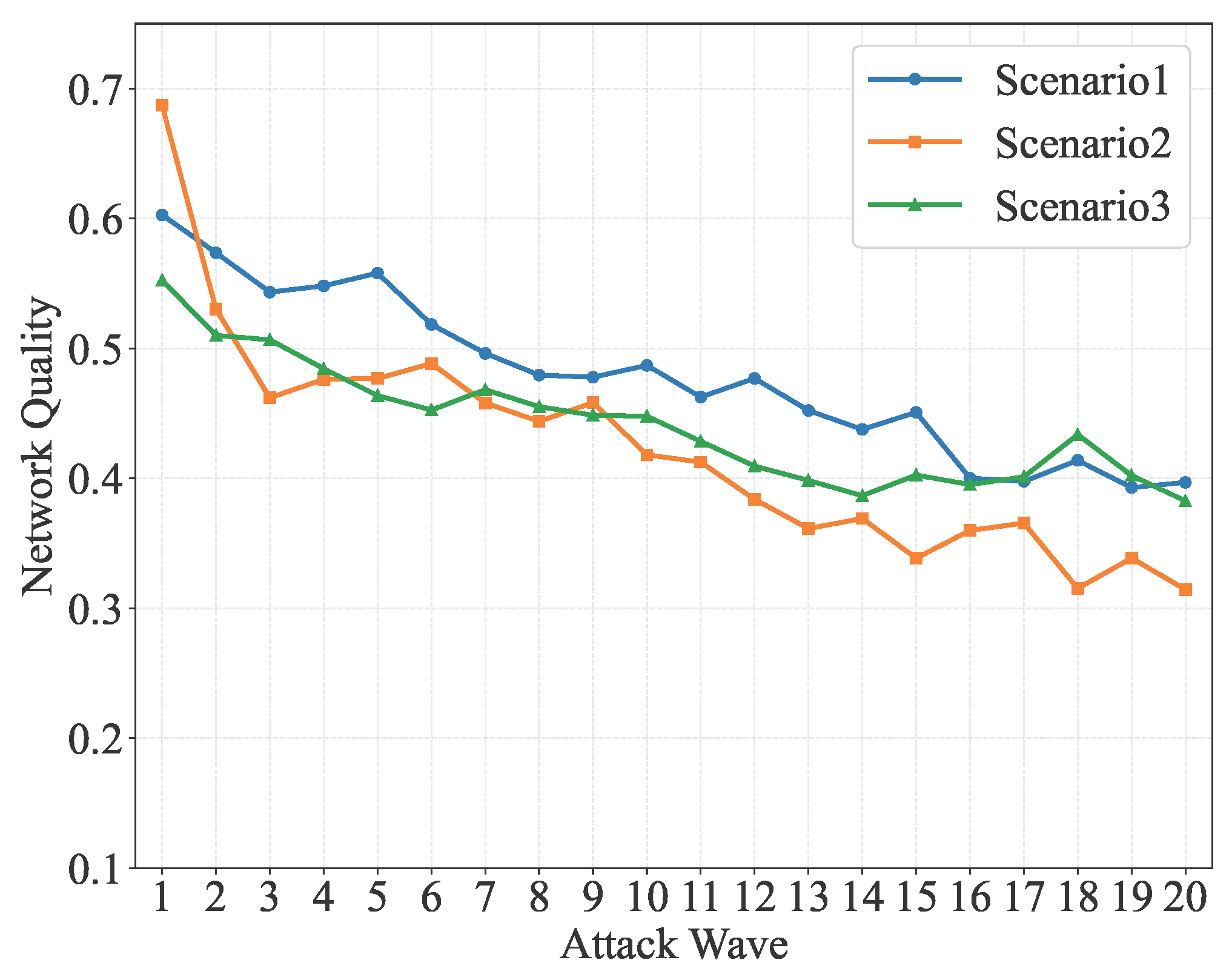

4.3.1. Evaluation Results of Random Attacks

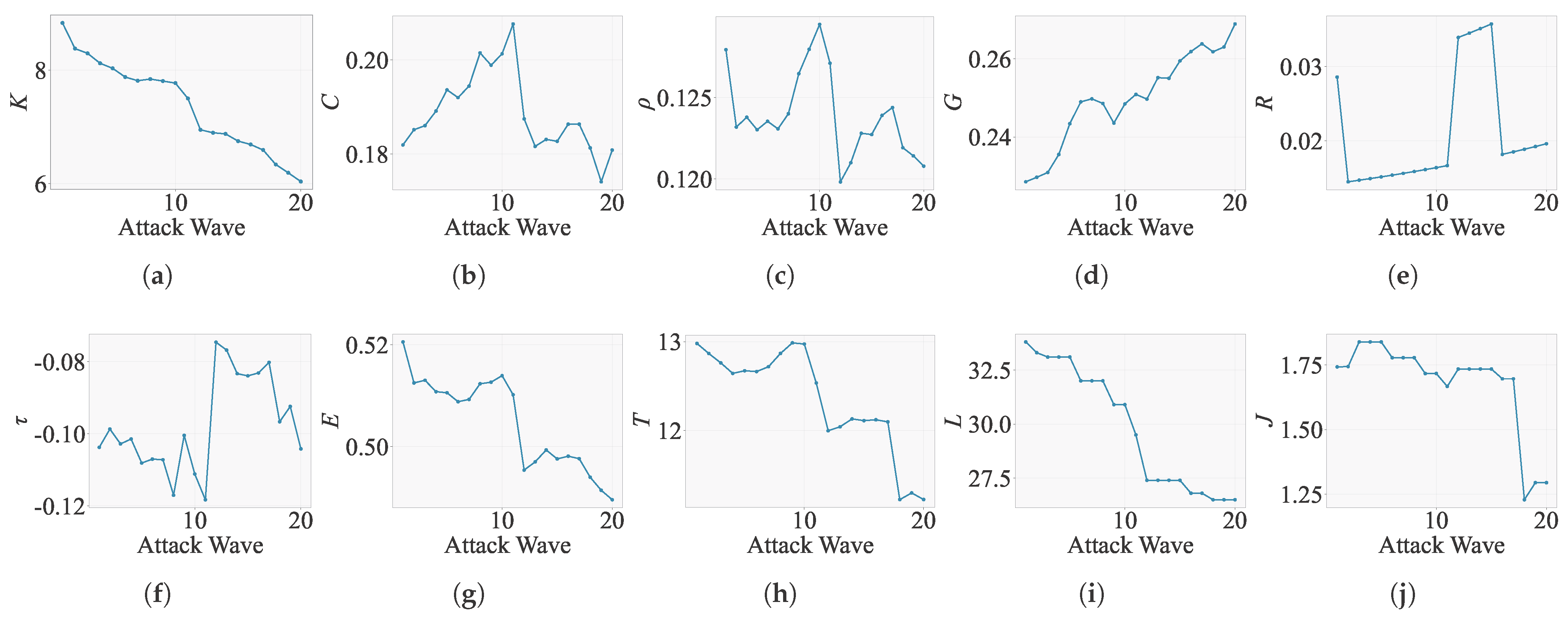

4.3.2. Evaluation Results of Targeted Attacks

5. Conclusions

- Complex networks can accurately characterise the structure of the drone swarm C2 system. By modeling the drone swarm C2 system as a network, complex network theory can be used to effectively analyse it.

- The network quality evaluation indicator system comprehensively considers three aspects: network connectivity, network load status, and network transmission efficiency. The method considers both static and dynamic characteristics, and the evaluation framework provides a reference for analyzing and evaluating other operational systems.

- The case analysis results indicate that hierarchical C2 networks with different structures have their own advantages and disadvantages under different scenarios (static conditions, random attacks, and targeted attacks). The effectiveness of the method is verified by comparing distributed and centralized networks. The dynamic network evaluation further demonstrates the universality of the evaluation method across networks with different structures, enabling it to guide the design of C2 system architectures.

- Current research focuses on single-function drone swarm C2 networks, whereas actual combat operations often involve the coordination of heterogeneous drones performing diverse tasks such as reconnaissance, strike, and communication relay. Future work should leverage the functional differences among heterogeneous nodes and integrate task performance metrics to build a hybrid evaluation framework that combines structural characteristics with actual task outcomes, making the evaluation results more directly serve the optimization of UAV swarm C2 system design for specific tasks.

- Current evaluations rely on predefined metric systems and optimization algorithms, lacking adaptability to unknown scenarios. Future approaches should incorporate machine learning or deep learning methods to enable models to autonomously learn optimal structural characteristics of C2 networks across diverse battlefield conditions. This would establish an integrated “evaluation–decision” intelligent framework, enhancing the drone swarm C2 system’s dynamic adjustment and autonomous operational capabilities.

- Current research on the drone swarm C2 network remains primarily focused on theoretical modeling and simulation analysis, with physical verification facing multiple practical obstacles. This paper primarily provides theoretical support at the modeling and simulation level for the advantages, disadvantages, and mission adaptability of swarm systems employing different command and control methods, though it lacks sufficient practical validation. Subsequent work will involve the development and utilization of a semi-physical simulation platform for drone swarms to collect real communication data and control response logs for verifying the experimental results presented herein. By comparing the measured data with the simulation results of the proposed evaluation model, we will verify the accuracy and practical applicability of the model, and gradually promote the transformation from theoretical simulation to engineering application-oriented validation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Han, K.; Zhang, P.; Hou, Z.; Ye, L. A survey on joint-operation application for unmanned swarm formations under a complex confrontation environment. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2023, 34, 1432–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T. Reliability analysis of command and control network system based on generalized continuous time Bayesian network. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2022, 44, 3880–3886. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Lin, C.; Chen, S.; Lu, C. Development of Adaptive Drone Swarm Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 131582–131599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, M. More is different in real-world multilayer networks. Nat. Phys. 2023, 19, 1247–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, M.; Buldú, J.M. Identifiability of complex networks. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1290647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Modelling and algorithms of highway transportation network in urban agglomerations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandelt, S.; Shi, X.; Sun, X. Estimation and improvement of transportation network robustness by exploiting communities. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 206, 107307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickdoost, N.; Shooshtari, M.J.; Choi, J.; Smith, D.; Abdelrazig, Y. A composite indicator framework for quantitative resilience assessment of road infrastructure systems. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2024, 131, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, M. Ecospatial network of forest carbon stocks in three parallel rivers region based on complex network theory. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 586, 122694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhou, W.; Qian, M.; Cao, A.; Zha, E.; Shi, X. Mechanisms of ecosystem function enhancement under land ecosystem restoration patterns and responses to multiple scenarios: A complex network approach. Land Use Policy 2025, 158, 107764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, H.; Huang, Y. The complex ecological network’s resilience of the Wuhan metropolitan area. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, J. Vulnerability analysis of cyber-physical power systems based on failure propagation probability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Wang, C.; Zhang, K. Identifying critical weak points of power-gas integrated energy system based on complex network theory. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 246, 110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ge, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhu, M.; He, Z. Controllability evaluation of complex networks in cyber–physical power systems via critical nodes and edges. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 155, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zong, Y.; Lu, N.; Jiang, B. Toward the resilience of UAV swarms with percolation theory under attacks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 254, 110608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liu, L. Analysis of Regional Air Defense Combat System Based on Supernetwork with Two Layers and Three Modes. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2025, 47, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Hai, X.; Feng, Q.; Sun, B.; Wang, Z. Modeling and vulnerability analysis of UAV swarm based on two-layer multi-edge complex network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 256, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, C. A baseline-resilience assessment method for UAV swarms under heterogeneous communication networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 6107–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfils, P. Information transmission in a drone swarm: A temporal network analysis. Drones 2024, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, D.; Li, R.; Wang, Y. Analysis on MAV/UAV cooperative combat based on complex network. Def. Technol. 2020, 16, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Research on UAV swarm network modeling and resilience assessment methods. Sensors 2023, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hou, Z.; Chen, H. Evaluation of vulnerability of MAV/UAV collaborative combat network based on complex network. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2023, 172, 113500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, T. Research on autonomous reconstruction method for dependent combat networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 6104–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Lu, D.; Zeng, G. Robustness evaluation method for unmanned aerial vehicle swarms based on complex network theory. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C. Research on resilience model of UAV swarm based on complex network dynamics. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2023, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, T.; Cao, R.; Li, Z.; Xu, J. UAV swarm resilience assessment considering load balancing. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 821321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C. A Co-Adaptation Method for Resilience Rebound in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Swarms in Surveillance Missions. Drones 2023, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, O.; Codrean, A. Networked Control of a Small Drone Resilient to Cyber Attacks. Drones 2024, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Guo, H.; Kato, N. Toward robust and intelligent drone swarm: Challenges and future directions. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shi, D. Stability of the BA network: A new approach to rigorous proof. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2009, 26, 038901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Ding, G.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Han, Z. Spectrum sharing planning for full-duplex UAV relaying systems with underlaid D2D communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2018, 36, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, H.; Ding, G.; Xu, Y.; Xue, Z.; Zhou, H. Energy-constrained completion time minimization in UAV-enabled Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things 2020, 7, 5491–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, G.; Dui, H. Cascading failure analysis of an interdependent network with power-combat coupling. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2024, 36, 405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, Y.; He, K. On countermeasures against cooperative fly of UAV swarms. Drones 2023, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Xia, R. Node importance evaluation in multi-platform avionics architecture based on TOPSIS and PageRank. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2023, 2023, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Song, M.; Tian, J.; Xue, R. Evaluation of air combat control ability based on eye movement indicators and combination weighting GRA-TOPSIS. Aerospace 2023, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Type | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | + | 7.5600 | 5.8600 | 8.9859 | 1.9700 | 69.0000 |

| C | + | 0.9353 | 0.2214 | 0.1774 | 0 | 1 |

| + | 0.1890 | 0.0837 | 0.1284 | 0.0282 | 1 | |

| G | − | 0.0771 | 0.3697 | 0.2276 | 0.4859 | 0 |

| R | + | 0.1220 | 0.0143 | 0.0282 | 0.0141 | 1 |

| + | 0.1031 | −0.2872 | −0.0971 | −1.0000 | 1 | |

| E | + | 0.4949 | 0.4667 | 0.5090 | 0.5141 | 1 |

| T | + | 15.3616 | 9.9129 | 13.0874 | 0.1786 | 28.4682 |

| L | − | 26.9000 | 29.6122 | 29.5434 | 29.1500 | 26.5000 |

| T | − | 1 | 1.6290 | 1.7526 | 1 | 1.0395 |

| Indicator | Type | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | + | 0.0934 | 0.0680 | 0.1147 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| C | + | 0.9453 | 0.2314 | 0.1874 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| + | 0.1755 | 0.0671 | 0.1131 | 0.01 | 1.01 | |

| G | − | 0.8513 | 0.2491 | 0.5416 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| R | + | 0.1194 | 0.0102 | 0.0243 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| + | 0.5616 | 0.3664 | 0.4616 | 0.01 | 1.01 | |

| E | + | 0.0629 | 0.01 | 0.0893 | 0.0989 | 1.01 |

| T | + | 0.5467 | 0.3541 | 0.4663 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| L | − | 0.9004 | 0.1573 | 0.1762 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| T | − | 1.01 | 0.8386 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.9575 |

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static evaluation | 0.4350 | 0.2248 | 0.2405 |

| Random attacks | 0.8311 | 0.3815 | 0.6640 |

| Targeted attacks | 0.4473 | 0.6382 | 0.7445 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Ru, L.; Hu, G.; Wang, W. A Quality Evaluation Method for Drone Swarm Command and Control Networks Based on Complex Network. Drones 2025, 9, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120839

Zhao Z, Chen S, Ru L, Hu G, Wang W. A Quality Evaluation Method for Drone Swarm Command and Control Networks Based on Complex Network. Drones. 2025; 9(12):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120839

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zijun, Shitao Chen, Le Ru, Gang Hu, and Wenfei Wang. 2025. "A Quality Evaluation Method for Drone Swarm Command and Control Networks Based on Complex Network" Drones 9, no. 12: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120839

APA StyleZhao, Z., Chen, S., Ru, L., Hu, G., & Wang, W. (2025). A Quality Evaluation Method for Drone Swarm Command and Control Networks Based on Complex Network. Drones, 9(12), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120839