Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose CE-Bi-RRT*, an enhanced bidirectional RRT* algorithm that integrates a cooperative expansion strategy—dynamic direct connection, intelligent deflection, and improved artificial potential field—to significantly accelerate convergence and improve path quality for UAVs.

- In comprehensive 2D simulations, CE-Bi-RRT* outperforms five state-of-the-art planners, achieving 15.2–16.0% shorter paths, 58.9–84.6% faster computation, and 50.8–69.3% reduced turning angles.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The algorithm explicitly accounts for UAV-specific constraints, such as minimum turning radius and limited onboard computation, making it well-suited for real-world fixed-altitude missions like infrastructure inspection and precision agriculture.

- The improvements in path smoothness and computational efficiency enhance the practical feasibility of deploying advanced sampling-based planners in real UAV missions with limited resources.

Abstract

Path planning is a critical capability for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) operating in complex 2D environments such as agricultural fields or indoor facilities—scenarios where flight altitude is often constrained and safe, smooth trajectories are essential. While the sampling-based Bidirectional RRT* (BI-RRT*) algorithm offers asymptotic optimality and improved computational efficiency, it frequently generates paths that lack the curvature continuity, obstacle clearance, and low turning angles required for stable drone flight. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a bi-directional rapid exploration random tree algorithm based on cooperative expansion strategy (CE-BI-RRT*) specifically designed for UAVs path planning in cluttered 2D settings. In terms of expansion, for different environments, the algorithm successively tests the direct expansion strategy, the intelligent deflection strategy and the improved artificial potential field method, as these strategies can quickly guide the two trees to the target while avoiding obstacles. In terms of ChooseParent and Rewire, the path length, path smoothness and safety distance are comprehensively considered in the path cost function, and a rotation strategy is applied to make the path away from obstacles after rewiring, so as to realize the gradual optimization of the path. The final path is further refined using a cubic Bezier curve optimization technique to ensure smooth transitions and continuous curvature. Evaluation results confirm its search performance when benchmarked against mainstream randomized motion planning algorithms.

1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly referred to as drones, are increasingly deployed across diverse domains, including agriculture [1,2], industrial inspection [3,4], and military operations [5,6], due to their agility, adaptability, and cost-effectiveness. However, the growing complexity and diversity of drone missions, especially in multi-domain operational environments, impose stringent demands on their autonomy and decision-making capabilities. Among these, path planning serves as a fundamental enabling technology, responsible for generating safe, efficient, and dynamically adaptable trajectories in complex environments [7]. Consequently, advancing path planning algorithms is critical not only for improving mission performance but also for expanding the practical applicability and operational boundaries of drone systems. For UAVs, safe and efficient path planning is not only a navigation necessity but also a prerequisite for mission success under real-world flight dynamics and operational constraints.

Various path planning approaches can be distinguished by the principles they rely on, including graph search algorithms [8,9], learning-based systems [10,11], interpolation-based trajectory design [12,13,14], and sampling-based planning methods [15,16]. Sampling-based algorithms in the configuration space, followed by collision detection and connection verification between neighboring points. These methods are probabilistically complete—meaning they will asymptotically find a solution if one exists as the number of samples increases. This makes them well-suited for complex environments. Although the Rapidly exploring Random Tree (RRT) approach typically offers better computational performance than Probabilistic Roadmap method (PRM), it tends to converge slowly and frequently yields non-optimal trajectories, primarily due to its stochastic sampling mechanism and basic node expansion strategy.

To improve the planning performance of the RRT framework in terms of exploration speed and trajectory optimality within complex environments, researchers have invested numerous efforts.

Improvements in sampling methods: Li et al. [17] introduced a Fast-RRT* algorithm that incorporates a hybrid sampling approach combining goal-biased and constraint-based strategies. In this method, if the randomly generated value () falls below the bias threshold (), the sampling process selects the goal as the target point. Otherwise, it performs random sampling until the predefined constraints are met. This integration effectively mitigates the randomness inherent in traditional RRT*, thereby enhancing the overall sampling effectiveness. This hybrid sampling strategy reduces the sampling blindness of RRT* algorithm and improves sampling efficiency. Similarly, an improved RRT* based on goal-biased sampling strategy and goal-biased extension strategy is introduced by Zhang et al. [18] Within a certain probability range, the target point is regarded as a sampling point. When it exceeds this range, the sampling range is limited to reduce the sampling randomness. Similar to the above-mentioned methods are [19,20]. Informed RRT* [21] defines an elliptical sampling area with initial and target points as the focus, and continuously modifies the ellipse parameters based on environmental information. The advantage of this method is that it guides the sampling range through environmental information, greatly improving sampling efficiency. In SOF-RRT* (Spatial Offset Fast-RRT*) [22], a spatially weighted probabilistic sampling approach was introduced, in which the likelihood of selecting a sample is determined based on its spatial distribution. This strategy improves the sampling probability of open areas and reduces redundant sampling. Sheng et al. [23] introduced an AB-APF-RRT* (Adaptive-Bias Artificial Potential Field RRT*) algorithm integrating adaptive sampling and artificial potential field guidance to improve path quality and planning efficiency in complex environments.

Ganesan et al. [24] proposed a hybrid-sampling RRT* algorithm that combines the advantages of both uniform and non-uniform sampling. This hybrid approach significantly reduces the number of nodes explored during path planning. The above algorithm improves the node sampling strategy to varying degrees based on different environmental information, making sampling more efficient. However, the author believes that the dynamic direct connection method proposed in this paper can be formed by combining the target bias sampling method with the extension method to accelerate search efficiency. Furthermore, when the effectiveness of this method is not ideal, the intelligent deflection strategy will provide additional assistance and improve the overall efficiency of the extended algorithm.

Improvements in extension methods: Wang et al. [25] introduced an improved BI-RRT* algorithm, which initializes two random trees at the same time from the initial point and the goal point. Through the alternating expansion strategy, it explores feasible paths in the state space to avoid falling into local optimum in the single-direction search. Subsequently, Sun et al. [26] proposed a Multi-Tree-RRT* algorithm, whose core principle lies in enhancing path planning efficiency and quality in complex environments through multi-tree parallel expansion and cross-tree optimization strategies. The core idea of the artificial potential field method is to construct the gravitational field of the target point and the repulsive field of the obstacle by simulating the electromagnetic field in physics, so as to guide the UAVs to avoid the dangerous area and reach the target position safely. Zhao et al. [27] combined the APF method with the random tree algorithm to plan the path of the UAVs and improve the convergence speed. Yang et al. [28] proposed a RRT* path planning method based on improved APF, which limits the expansion area of RRT* through APF repulsion field, guides the tree structure to grow in the target direction, and reduces invalid expansion. However, the artificial potential field (APF) method exhibits inherent limitations, including susceptibility to local minima traps, chattering phenomena near target points, and potential goal unreachability under specific obstacle configurations. Xiao et al. [29] introduced the particle swarm optimization algorithm into the path planning process of the artificial potential field method and proposed the equipotential line method to handle the minimum problem, which overcame the jitter problem of the artificial potential field method and greatly reduced the probability of becoming trapped in local minima. Feng et al. [30] addressed the issues of local optima and goal unreachability by enhancing the obstacle repulsive potential field function. Li et al. [31] introduced an Iterative Safe Dispatch Corridor (iSDC) framework. Their algorithm integrates bidirectional tree expansion, goal-biased elliptical sampling, and artificial potential field guidance to minimize unnecessary exploration near concave obstacles. To improve path smoothness, this paper modifies the repulsive force field function again and incorporates an additional directional force from grandparent node to parent node, which limits the path turning angle.

Most existing RRT*-based algorithms focus primarily on sampling strategy refinement, which is insufficient to meet the practical demands of UAV navigation in fixed-altitude 2D missions where computational efficiency, path smoothness, and flight feasibility must be jointly optimized. It is worth noting that UAV path planning must take into account its inherent flight constraints, such as minimum turning radius and limited onboard computational resources. Therefore, this paper proposes a bidirectional RRT* algorithm incorporating a cooperative expansion strategy (CE-Bi-RRT*). The key enhancements can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Enhanced expansion mechanism: Firstly, to enhance the orientation towards the target, the algorithm probabilistically expands directly toward the target. This approach is referred to as the dynamic direct connection strategy. If this expansion method is unsatisfactory, the algorithm transitions into an intelligent deflection phase. During this phase, the algorithm adjusts the deflection angle dynamically based on the size of the obstacle ahead, enabling rapid bypassing of obstacles. When neither the dynamic direct connection strategy nor the intelligent deflection phase yields satisfactory results, the algorithm integrates a modified artificial potential field approach to dynamically evaluate environmental conditions, thereby facilitating more efficient progression toward the target. Additionally, we have refined the repulsion function. On the original basis, an additional repulsive force directed from the grandparent node to the parent node of the new node is introduced. This modification effectively constrains the path turning angle, contributing to improved path quality.

- (2)

- Improvements in ChooseParent and Rewire methods: During the ChooseParent phase, the algorithm modified the path cost function to comprehensively consider path length, path turning angle and safe distance. In the Rewire stage, the algorithm performs rotation optimization on the reconnection line segments that are too close to obstacles. These improvements also contribute to improving path quality.

The main content of this work is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the fundamental theories and key advancements in the Rapidly exploring Random Tree family, with a focus on variants such as BI-Goal-Bias-RRT*, Goal-Bias-RRT*, BI-RRT*, BI-APF-RRT*, and APF-RRT*. Section 3 elaborates on the core mechanisms of the proposed CE-BI-RRT* algorithm. Section 4 conducts a comparative simulation experiment evaluating CE-BI-RRT* against five benchmark algorithms. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings of this study and outlines possible directions for future research.

2. Related Works

2.1. Overview

The CE-BI-RRT* algorithm is developed by integrating and enhancing the core strategies of RRT*, Goal-Biased RRT* and BI-RRT*, aiming to improve planning efficiency and path quality. This section describes these algorithm frameworks in detail to prepare for the introduction of CE-BI-RRT* algorithm.

2.1.1. RRT

RRT is the basis for all the algorithms [32]. As shown in Algorithm 1, it begins with a tree initialized at the initial node xinitial. During each iteration, a random sample is generated in the configuration space. Once the nearest node xn is determined, the algorithm proceeds by extending it toward the sampled point by a step of λ, thereby obtaining a new node xnew. If the path to xnew is collision-free, it is added to the tree. This process continues until xnew is within a specified distance of the target xtarget, at which point a feasible path from start to goal is obtained.

| Algorithm 1 RRT |

| 1: V ← {xinitial} # Node set with initial configuration |

| 2: E ← ∅ |

| 3: T ← (V, E) |

| 4: for iter = 1 to Max_Iter do |

| 5: xrand ← SampleFree(C) |

| 6: xn ← GetNearest (T, xrand) |

| 7: xnew ← Steer(xn, xrand, ) |

| 8: if NoCollision (xn, xnew) then |

| 9: V ← V ∪ { xnew} |

| 10: E ← E ∪ {(xn, xnew)} |

| 11: end if |

| 12: if Distance(xnew, xtarget) < Threshold then |

| 13: Path ← ExtractPath(T) |

| 14: return Path |

| 15: end if |

| 16: end for |

| 17: return Failure |

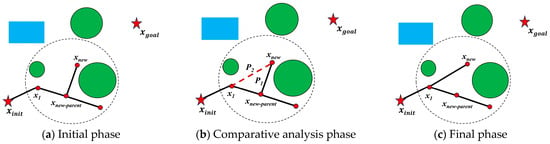

2.1.2. RRT*

To improve the quality of the path, Karaman et al. [16] proposed an RRT* algorithm, which added the ChooseParent strategy, as shown in Algorithm 2 and Rewire strategy as shown in Algorithm 3 to the RRT algorithm. As shown in Figure 1, during the comparative analysis phase, the algorithm calculates the cost of path P1 and path P2. If the cost of P2 is less than that of P1, the connection from xnew to its current parent node (xnew_parent) will be removed, and a new path from xnew to x1 will be established. Similarly, the Rewire strategy is illustrated in Figure 2: xnew is used as the parent node to connect with each nearby node and determine whether the resulting path cost is lower than the current one. If the resulting path cost is lower, the parent node is updated to xnew.

| Algorithm 2 ChooseParent |

| Input: Xnear, xn, xnew |

| Output: xparent |

| 1: xparent ←xn |

| 2: Cmin ← Cost(xn)+ Distance(xn, xnew) |

| 3: for each xnear Xnear do |

| 4: C ← Cost(xnear) + Distance(xnew, xn) |

| 5: if NoCollision (xnew, xnear) then |

| 6: if Cmin > C then |

| 7: Cmin ← C |

| 8: xparent ← xnear |

| 9: end if |

| 10: end if |

| 11: end for |

| 12: return xparent |

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the ChooseParent process (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles. Red dashed lines: candidate parent connections. The new node selects the parent that minimizes its total path cost.).

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of the Rewire process (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles. Red dashed lines: candidate rewiring links from the new node to its neighbors. Existing nodes switch parents if a lower cost-to-come is achieved via the new node.).

| Algorithm 3 Rewire |

| Input: Xnear, xnew |

| Output: T = (V, E) |

| 1: for each xnear Xnear do |

| 2: if Cost(xnew) + Distance(xnear, xnew) < Cost(xnear) then |

| 5: end if |

| 6: end for |

| 7: return T = (V, E) |

2.1.3. APF-RRT*

To enhance the local exploration ability of the algorithm, Qureshi et al. [33] improved the RRT* framework by integrating an artificial potential field (APF) strategy to influence the tree expansion. Obstacles exert repulsive forces on xn, and target points exert attractive forces on xn. The growth of the exploration tree is guided by the resultant force. The pseudocode of APF-RRT* is shown in Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4 APF-RRT* |

| 1: V ← {xinitial}, E ← ∅, T ← (V, E) |

| 2: for iter = 1 to Max_Iter do |

| 3: xrand ← SampleFree(C) |

| 4: xn ← GetNearest (T, xrand) |

| 5: Fatt ← AttractionForce(xn, xgoal) |

| 6: Freq ← RepulsionForce(xn, xobstacle) |

| 7: Ftotal ←Fatt + Freq |

| 8: xrand ← SampleFree© |

| 9: xnew ← Steer(xn, Ftotal, ) |

| 10: xparent ←ChooseParent (xnear-parent, xnew) |

| 11: if NoCollision (xparent, xnew) then |

| 13: E ← E ∪ {(xparent, xnew)} |

| 14: Rewire(T, xnew, V, E)) |

| 15: end if |

| 16: if NoCollision (xnew, xgoal) and Distance(xnew, xgoal) < Threshold then |

| 18: E ← E ∪ {(xnew, xgoal)} |

| 19: return Path(T) |

| 20: end if |

| 21: end for |

| 22: return Path |

2.1.4. BI-RRT*

To enhance expansion efficiency, Rybus et al. [34] introduced the BI-RRT* algorithm, which builds two trees simultaneously. One tree grows from xinitial toward xgoal, while the other extends from xgoal toward xinitial. The two trees keep expanding toward each other during the planning process. When a pair of nodes is found within the defined distance threshold and the direct path between them is collision-free, the trees are connected.

2.2. Assessment of Current Research Gaps

Compared with the original RRT algorithm, its variants such as RRT*, BI-RRT*, BI-Goal-Biased RRT*, APF-RRT*, and Goal-Biased RRT* have demonstrated significant improvements. However, further enhancements remain possible. The path cost function of RRT* only considers the path length. In the subsequent research, we incorporate turning angle and safety distances into the cost function to improve the path quality. BI-RRT* improves the convergence speed through bidirectional alternating expansion, but the expansion direction lacks directionality and there is still room for improvement in the exploration speed. APF-RRT* utilizes an artificial potential field to guide node expansion toward goal regions and enhance obstacle avoidance performance. But excessive turning angle will reduce the path quality. To address this limitation, this study proposes CE-BI-RRT*, which integrates bidirectional search with potential field-based guidance to enhance both planning efficiency and path smoothness in complex environments.

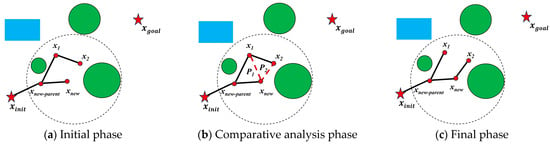

3. The CE-BI-RRT* Framework

3.1. Problem Analysis and Solution Framework

The performance of RRT* is significantly affected in complex and densely cluttered environments, where it often suffers from slow convergence and limited utilization of environmental information. Existing research highlights issues such as excessive exploration of irrelevant regions and poor trajectory smoothness. To address these drawbacks, we propose CE-BI-RRT*, which incorporates the bidirectional search mechanism of BI-RRT* and enhances the extension, ChooseParent, and Rewire method of the original RRT* framework.

The main improvements of CE-BI-RRT* algorithm concern the following three main aspects:

1. High efficiency expansion strategy: In the expansion process of the algorithm, according to the location of goal, three expansion methods are sequentially applied until a suitable direction for expansion is found, thereby guaranteeing a more efficient path search.

2. High quality ChooseParent and Rewire strategy: Upon successful insertion of a new node into the search tree, the algorithm recalculates the cost of adjacent nodes to determine opportunities for path refinement and optimization. This path cost function includes the total length of the path, the turning angle and the safe distance, thereby obtaining the approximately optimal path. The Rewire strategy can effectively reduce redundant paths. However, the reconnected path may collide with obstacles. To address this issue, the algorithm introduces a rotation optimization module to improve the success rate of reconnection and ensure path quality.

3. Path smoothing method: After the path is generated, it is optimized using cubic Bezier curves to make the path smoother.

Figure 3 shows the CE-BI-RRT* algorithm process flowchart.

Figure 3.

CE-BI-RRT* algorithm process flowchart.

3.2. The Combination Extension Methods of CE-BI-RRT*

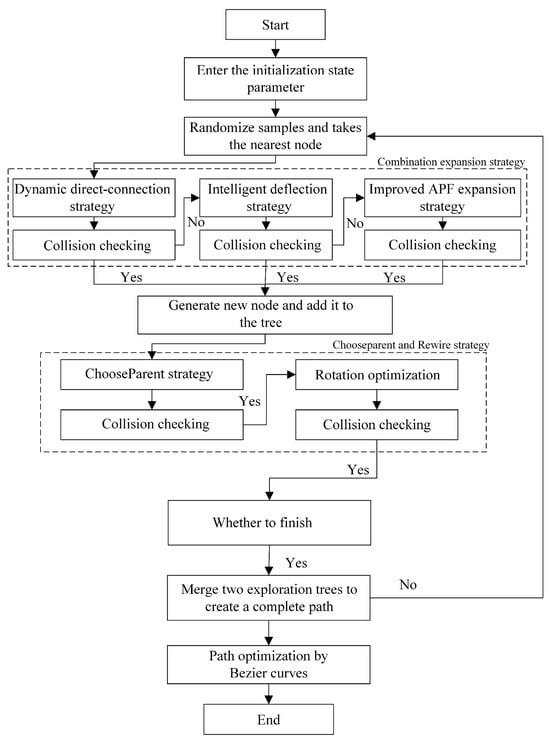

3.2.1. Dynamic Direct-Connection Strategy

For unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) operating in constrained environments, the traditional RRT* algorithm’s reliance on probabilistic sampling often leads to inefficient exploration and trajectories that violate practical flight constraints such as minimum turning radius or limited onboard computation. Therefore, this paper proposes a dynamic direct-connection strategy. An illustration of this strategy is provided in Figure 4a. The proposed strategy retains the core idea of RRT*’s random exploration, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the search space. At the same time, it addresses the inefficiency of RRT* during the expansion stage by introducing a dynamic direct-connection mechanism. Specifically, with a certain probability p, the algorithm attempts to directly connect xn to xgoal. This encourages the algorithm to prioritize direct expansions toward the target, thereby mitigating inefficiencies caused by random search.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of dynamic direct-connection strategy. (a) If collision-free → trigger direct connection. (b) If path is not collision-free → trigger next strategy. (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles.).

The dynamic nature of the algorithm is realized through an adaptive probability modulation mechanism. Specifically, when the cumulative number of expansion failures ftotal exceeds a predefined threshold, the system dynamically attenuates p. This mechanism significantly mitigates redundant iterations resulting from blind repetitive attempts in challenging areas, thereby enabling adaptive responses to dynamically changing environments. The calculation formula for the probability p is presented in Equation (1).

In these, ffail represents the failure count threshold, and ftotal denotes the current cumulative failure count. As an adjustable parameter, the probability p decreases with the increase in failure times, which encourages the algorithm to give priority to subsequent exploration strategies. When the random probability prand < p, xnew is generated by expanding from xn toward xgoal. The xnew calculation follows Equation (2),

where xn is the node closest to the sampling point xrand, is the expansion step size, and xgoal − xn is the direction vector pointing from xn to the xgoal. After xnew is generated, collision checking needs to be carried out to ensure that xnew maintains a minimum safe distance of dmin from the obstacles, and the line from xn to xnew does not collide with the obstacles. If xnew collides with the obstacles, xnew will not be added to the random tree in this extension. The algorithm will enter the extension phase of intelligent deflection strategy.

The dynamic direct-connection strategy leverages global sampling to ensure comprehensive coverage of the search space, accelerates expansion through a dynamic parameter adjustment mechanism, and effectively addresses the inefficiency issues inherent in the original RRT* algorithm. However, in complex environments, as expansion failure counts accumulate, the probability p decays progressively, leading to prand > p. Consequently, an intelligent deflection strategy is required to guarantee effective node expansion. Similarly, if collision checking fails, the algorithm transitions into the intelligent deflection strategy phase.

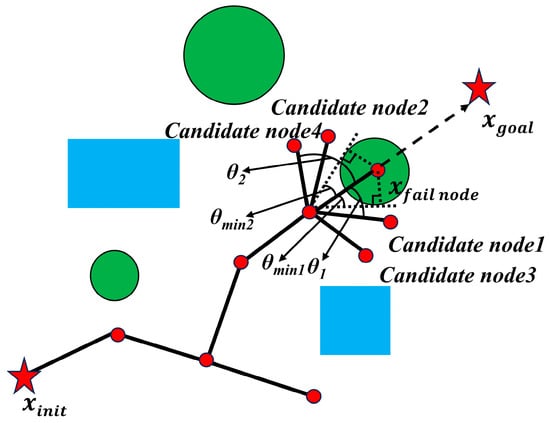

3.2.2. Intelligent Deflection Strategy

When expanding into area occupied by obstacles, the collision detection in the dynamic direct connection strategy informs the algorithm that the direct connection path will collide with the obstacles, thereby halting exploration. Aiming to improve both local sampling effectiveness and planning efficiency, we propose an intelligent deflection approach that enhances the node expansion behavior of RRT*. The key concepts and procedural details of this strategy are presented in the following section.

Step1. Trigger condition: during algorithm execution, if a collision detection failure occurs, ftotal increased by 1.

Step2. Enable intelligent deflection strategy: select xn as the focus, calculate the direction vector v from xn to xgoal, calculate tangent vector k1 and k2 from xn to obstacle, and calculate the angle min1 and min2 between vector v and vector k1 as well as vector v and vector k2.

Step3. Generate candidate nodes: In order to enable nodes to bypass obstacles, four candidate points are obtained by rotating the direction vector v by an angle of min + 15° or min + 30°. The generation of candidate nodes is shown in Equations (3)–(6).

where xn is the node closest to the sampling point xrand, is the expansion step size, and xgoal − xn is the direction vector pointing from xn to the goal.

Step4. Path validity assessment: The algorithm evaluates whether a collision-free connection exists between the node xn and each candidate point. A candidate point is classified as valid if no obstacles obstruct the direct path to xn.

Step5. Select the candidate point: Sort the feasible candidate points and select the candidate point with the one with the smallest angle relative to the direction vector or the one closest to xn.

Step6. Strategy switch mechanism: In cases where all candidate points fail validation, the algorithm dynamically transitions to an improved artificial potential field expansion approach to continue exploration.

This approach enables the algorithm to navigate around obstacles in the direction of motion v, while guiding the trajectory toward the goal through a more direct and obstacle-free route. A schematic illustration of the intelligent deflection strategy is provided in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of intelligent deflection strategy (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles.).

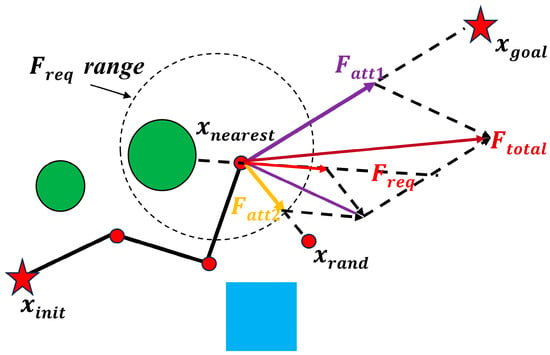

3.2.3. Improved Artificial Potential Field Expansion Strategy

In UAV applications, maintaining a safe clearance from obstacles is critical for mission safety, especially in low-altitude environments. The artificial potential field method is a motion planning technique that model navigation as an interaction of virtual attractive and repulsive forces. Its core idea is to treat the goal as an attractive source and obstacles as repulsive sources, and guide the UAV’s motion by calculating the resultant force. Therefore, the artificial potential field method can effectively utilize environmental information to guide new nodes towards the goal. When both previous extension methods fail, it indicates that the obstacle between the nearest node xn and the goal xn is large and close to the xn. At this point, the artificial potential field method can perceive this information and effectively utilize it to guide expansion based on the current environment, thereby enhancing its obstacle avoidance capability. The above three expansion strategies can be applied alternately or in combination, allowing the algorithm to maintain global random search while also effectively avoiding local obstacles and accelerating convergence.

In the APF framework, the potential field is composed of an attractive potential field Uatt(xn) (Equation (7)), a repulsive potential field Urep(xn) (Equation (8)), and the total potential field Utotal, as shown in Equation (9). The APF method demonstrates the following key characteristics.

In this context, xn, xgoal and xobs denote the spatial location of the nearest node, target and obstacle center, respectively. The parameters and serve as scaling factors for the attractive and repulsive potentials, while ρ0 defines the effective range of the obstacle’s repulsion. The Euclidean distances from xn to xgoal and from xn to xobs are denoted by and , respectively. The attractive and repulsive forces are defined as the negative gradients of their corresponding potential functions. More specifically, the attractive force Fatt is formulated in Equation (10), the repulsive force Frep is described in Equation (11), and the total resultant force Ftotal is expressed in Equation (12).

With the integration of the improved artificial potential field method into the RRT* framework, node generation is influenced by the artificial potential method. In this process, xgoal and xrand exert attractive forces on xn, while obstacles exert repulsive forces on xn. The orientation of the resultant force Ftotal determines the generation orientation of xnew. The force diagram for xn is illustrated in Figure 6, where Fatt1 and Fatt2 represent the attractive forces from xgoal and xrand, respectively, and Freq denotes the repulsive force from the obstacle. The resultant force direction, determined using the parallelogram rule, defines the expansion direction of xnew.

Figure 6.

A schematic of the improved APF method (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles.).

However, the APF method has two notable limitations. First, when the goal is too close to an obstacle, the repulsive force Freq may exceed the attractive force Fatt as iterations progress. In such cases, xnew tends to oscillate near the target. Second, if the repulsive forces Freq from multiple obstacles are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction to Fatt, the resultant force becomes zero, causing xnew to lose its expansion direction. Therefore, this paper uses an improved APF method, described as follows:

where xn, xgoal, xobs and xn-parent correspond to the positions of the nearest node, the goal, the center of the obstacle and the parent node of the nearest node, respectively. is the Euclidean distance between xn and xobs and is the distance between xn and xgoal. The Euclidean distance between xn and xn-parent is integrated into the potential field function. When encountering the issue of unreachable goal, the modified repulsive force is formulated as follows:

where non, nng and nnp are three-unit vectors, which are the direction vectors from xobs to xn, the direction vectors from xn to xgoal and the direction vectors from xn to xn-parent, respectively. As the new node moves closer to the goal, the repulsive force decreases, ensuring that the path can reach the goal. Additionally, to enhance path smoothness, the algorithm incorporates Frep3 into the expansion direction of each node. A new node xnew is then created by moving from xn along the resultant force vector with a predefined step length. This candidate node is only accepted if the path to it is confirmed collision-free.

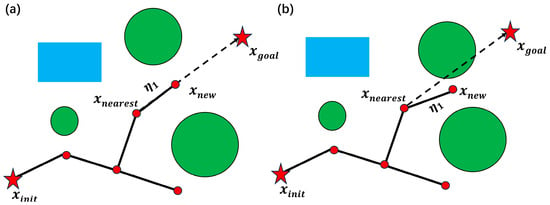

3.3. ChooseParent and Rewire in CE-Bi-RRT*

In real-world UAV operations, path quality is not only about length but also about flyability. Sharp turns or proximity to obstacles can trigger emergency maneuvers or even crashes. To this end, this paper defines the path cost function to jointly consider path length, turning angle, and safety distance—three key factors that directly impact trajectory tracking performance in standard flight controllers.

When the expansion strategy adds a new node to the exploration tree, it searches for a candidate parent node among all neighboring nodes within a given radius around the new node xnew. The chosen parent node must be connectable to the new node and have the minimum path cost. The traditional ChooseParent strategy often focused solely on path length, neglecting path smoothness and the safe distance between the new path and obstacles. To elevate the overall performance and usability of the planned route, this paper defines the path cost function as shown in Equation (23).

where is the cumulative path length from xinitial to xn, is the angular change in each segment in the path and is the distance between the path and the nearest obstacle. Additionally, are the weight coefficients of the three indicators, respectively, which are used to balance the importance of different cost components. For example, in complex environments, the value of can be increased to prioritize safety.

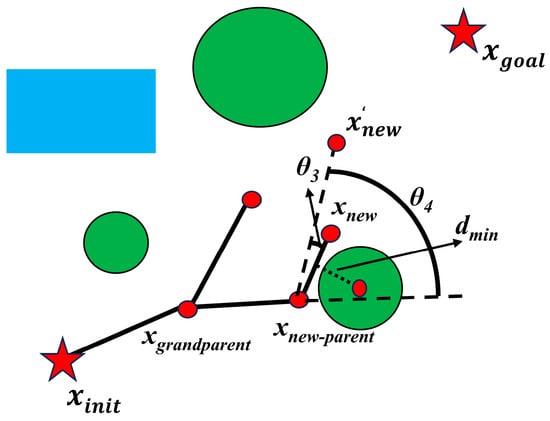

The reconnection path may pass collision checking but it can still be close to obstacles, which does not satisfy the requirements of a high-quality path. To address this issue, we incorporated a rotation optimization method into the Rewire method. During the Rewire operation, a minimum distance detection is performed for the new path. If the new path is excessively close to an obstacle, the vector from xnew to xnew-parent is rotated by a small angle away from the obstacle to minimize the risk of collision. The basic logic and steps of the rotation optimization strategy are as follows:

Step1. Calculate the distance dmin from the reconnection path to the obstacle.

Step2. Check whether dmin is less than the minimum given distance dgiven.

Step3. If dmin < dgiven, rotate a given angle 3 = 15° away from obstacles to obtain .

Step4. Smoothness limitation: If the xnew-parent also has its parent node, we call it a grandparent node xgrandparent, and we need to ensure that the angle 4 between the vector from to xnew-parent and the vector from xnew-parent to xgrandparent is less than 90°. If the angle is too large, the path will experience a turn back phenomenon, which does not meet the path cost function.

Step5. Path validity verification: The algorithm evaluates whether a collision-free connection exists between xnew-parent and .

If the segment is obstacle-free and the angle 4 is less than 90°, the new configuration is considered valid. The schematic diagram of the rotation optimization strategy is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

A schematic of the rotation optimization strategy (Red dots: tree nodes. Green circles and blue rectangles: obstacles.).

The algorithm proposed in this article enhances the cost function of the ChooseParent method and applies rotation optimization to the rewire strategy, enabling the path to gradually converge toward an approximate optimum. These two processes complement each other: the ChooseParent method minimizes the path cost, while the Rewire strategy eliminates redundant paths. Through iterative refinement, a high-quality path is ultimately achieved.

3.4. Connecting Bidirectional Search Trees for Full Path Construction

Throughout the iterative procedure, new nodes are continuously integrated into each exploration tree. Termination occurs when a pair of nodes—one from each tree—exhibits a Euclidean distance smaller than the threshold f, under the condition that the connecting path is free of obstacles. Subsequently, a continuous path is established from the initial position xinit to the target destination xgoal.

3.5. Cubic Bezier Curves Smoothing Processing

Discontinuous curvature demands infinite angular acceleration from drones, a scenario that is physically unachievable in real-world UAVs and may destabilize the flight controller. This paper utilizes cubic Bezier curves to smooth paths, which constructs continuous and smooth curves through parameterized control points. Compared to traditional interpolation methods, cubic Bezier curves offer significant advantages in path smoothing.

3.5.1. Path Boundary Extension

When directly using the endpoints of the original path as control points for a Bezier curve, the lack of intermediate control points introduces insufficient geometric constraints. This may result in unintended curvature discontinuities or deviations from the actual path boundaries at the terminal regions. Therefore, the path boundary needs to be extended.

where x2 and xn−1 are the second and penultimate points of the original path, respectively. The extended path contains n + 2 points to ensure that the Bezier curve is tangent to the original path at the beginning and end. The extended path sequence is

3.5.2. Piecewise Cubic Bezier Curve Construction

The extended path is divided into n − 1 segments of cubic Bezier curves. Each curve segment is defined by four consecutive points {x1, x2, x3, x4} on the original path, which are then mapped to control vertices B0, B1, B2, B3 to ensure smooth transitions.

3.5.3. Parametric Equation of Cubic Bezier Curve

For each curve segment, by letting t ∈ [0, 1], the curve equation can be expressed parametrically as

The smoothed Bezier curve requires collision checking to ensure that the path does not intersect with obstacles. To achieve this, the Bezier curve is discretized into multiple points, and each point is checked to determine whether it falls within obstacle regions. If the smoothed path intersects obstacles, the parameter t is adjusted, and the path length L is recalculated iteratively until a collision-free path with minimal L is obtained. The complete path is constructed by concatenating the n − 1 discrete curve segments end-to-end.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

In this section, we compare the proposed CE-BI-RRT* algorithm with five benchmark algorithms: Goal-Bias-RRT*, BI-RRT*, BI-Goal-Bias-RRT*, BI-APF-RRT*, and APF-RRT*. All simulations were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i9-12700H CPU, 32 GB RAM, running Windows 11, using MATLAB R2021b.

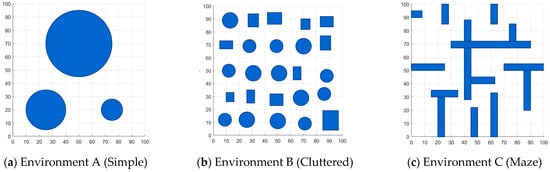

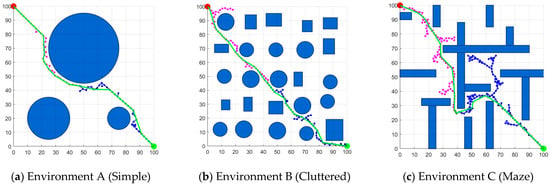

As shown in Figure 8, a continuous 100 × 100 map is selected as the two-dimensional workspace. Circular or rectangular obstacles are placed within the map, and the level of congestion is adjusted by varying their sizes. In total, two simulation environments with different congestion levels are designed. Additionally, to evaluate the algorithm’s performance in more complex scenarios, a maze-like map is introduced as the third simulation environment. These environments are named Environment A, B and C. In the simulation, we selected (0, 100) and (100, 0) as the initial node xinitial and the goal node xgoal for Environments A, B, and C, respectively. In this paper, the weight coefficient of the path length is set to 0.6, the weight coefficient of the turning angle is set to 0.3, and the weight coefficient of the safety distance is set to 0.1 at the same time. In the CE-BI-RRT* algorithm, the initial dynamic direct connection probability is set to 0.8, and in the comparison algorithm Goal-Bias-RRT*, the goal-bias probability is also set to 0.8.

Figure 8.

Three simulation environments.

Each algorithm was independently run 50 times with an upper iteration limit of 1000 to assess result consistency and repeatability. Final performance metrics were obtained by averaging outcomes across all trials. Evaluated indicators included the average path length, average running time, average number of iterations and average path turning angle. Within the bidirectional search framework, the tree originating from the start node xinitial is visualized using a pink line connecting to the goal node xgoal. Meanwhile, the other tree initiated from xgoal is depicted in blue, illustrating its growth toward xinitial.

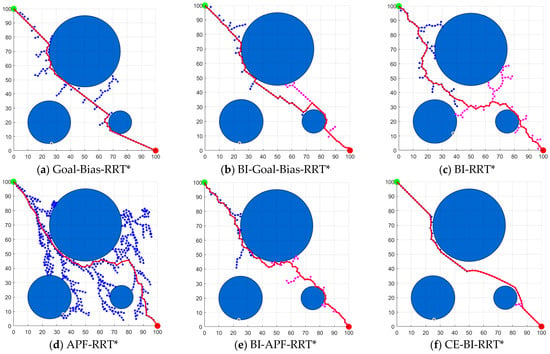

4.1. Environment A

Figure 9 shows the simulation results obtained in Environment A, and Table 1 reports the corresponding data. Compared with other algorithms, the proposed algorithm produces paths with fewer redundant nodes, leading to improved straightness and smoothness. As shown in Table 1, the proposed CE-BI-RRT* algorithm achieves reductions in average path length of 12.10%, 8.84%, 14.36%, 7.23%, and 12.04%, compared to BI-Goal-Bias-RRT*, Goal-Bias-RRT*, BI-RRT*, APF-RRT* and BI-APF-RRT*, respectively. The proposed CE-BI-RRT* algorithm has an average running time of 0.1 s in a simple environment. A feasible path can be found within 38 iterations, with the average path turning angle reduced to 8.11°. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm exhibits notable advantages in simple environments.

Figure 9.

Algorithm performance results in environment A.

Table 1.

Simulation data of six algorithms in different environments.

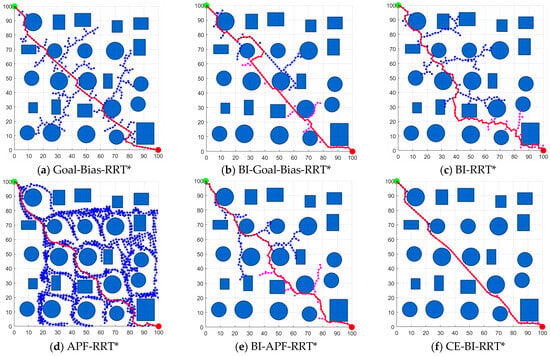

4.2. Environment B

The results for Environment B are visualized in Figure 10, while the corresponding numerical data are tabulated in Table 1. In Environment B, although BI-RRT* is capable of finding a feasible path with relatively fast speed and fewer iterations, its path generation quality is significantly affected by the high randomness in both sampling and expansion processes. As a result, the algorithm produces an average path length of 178.87 and an average turning angle of 32.18°, both of which are considerably higher than those achieved by other comparison algorithms. With an increased number of obstacles in Environment B, the APF-RRT* algorithm experiences more complex force field interactions during path expansion, making it difficult to move directly toward the goal in each iteration. This leads to higher computational costs. BI-APF-RRT* improves exploration efficiency through the use of a bidirectional tree strategy; however, its average running time remains as high as 4.69 s. Moreover, the inconsistent expansion directions between the two trees further increase the average turning angle of the generated paths. Goal-Bias-RRT* and BI-Goal-Bias-RRT* utilize goal node information to guide the search direction, effectively reducing redundant nodes and accelerating the overall search process. However, when obstacles block the direct path to the goal, Goal-Bias-RRT* encounters significant difficulty in expanding the search tree, thereby degrading its performance. In contrast, the proposed CE-BI-RRT* algorithm adopts a combination expansion strategy. This approach significantly enhances the expansion efficiency of the search tree. As shown in Figure 10 and Table 1, CE-BI-RRT* can efficiently avoid obstacles even in complex environments. The algorithm achieves an average runtime of only 0.17 s, an average path length of 147.09, and an average path turning angle of 9.15°. Furthermore, the improved path cost function effectively reduces both the path turning angle and path length, resulting in smoother and higher-quality paths.

Figure 10.

Algorithm performance results in environment B.

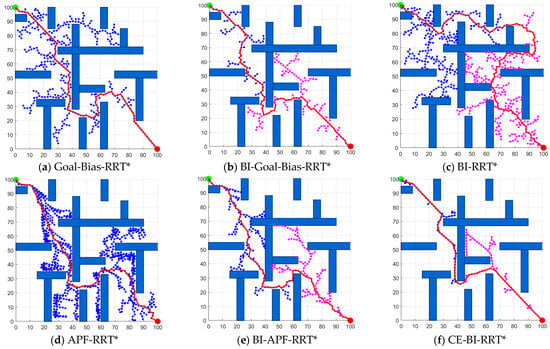

4.3. Environment C

In the more challenging Environment C, the benefits of the proposed algorithm are more clearly demonstrated. Simulation results are shown in Figure 11, with supporting data reported in Table 1. The simulation results clearly show that BI-RRT*, APF-RRT*, and BI-APF-RRT* exhibit similar issues in Environment C, leading to slower exploration speeds and poorer path quality. Goal-Bias-RRT* and BI-Goal-Bias-RRT*, which rely solely on the positional information of the goal, demonstrate slightly improved convergence performance in complex environments compared to APF-RRT* and BI-APF-RRT*. However, they still fail to effectively ensure the overall quality of the generated paths. As shown in Figure 11, the CE-BI-RRT* algorithm flexibly employs different exploration strategies based on the map environment, effectively reducing the generation of redundant nodes. In spacious areas, the algorithm prioritizes rapid expansion toward the goal. When the direct connection attempt fails, the algorithm enters an intelligent deflection phase, where it performs small-angle detours based on obstacle size, enabling quick obstacle avoidance while effectively controlling the turning angles of the path. If neither of the above two expansion strategies can find a suitable direction, CE-BI-RRT* incorporates an improved artificial potential field method. By introducing a constraint force from the grandparent node to the parent node into the repulsive field function, the algorithm guides the direction of new node generation, thereby reducing path turning angles and enhancing overall path smoothness. Furthermore, the path cost function has been improved to comprehensively consider multiple factors, including path length, turning angle, and safety distance from obstacles. During the Rewire phase, a rotation optimization strategy is introduced to significantly improve both the success rate and quality of rewire. Comparative results across all evaluation metrics demonstrate that CE-BI-RRT* significantly outperforms other algorithms, highlighting its efficiency and reliability in path planning tasks within complex environments.

Figure 11.

Algorithm performance results in environment C.

4.4. Path Optimization

While the algorithm produced valid paths in all three simulation environments, the resulting trajectories were characterized by frequent directional changes and insufficient curvature smoothness, which did not fully satisfy the UAV’s motion constraints. To overcome this limitation, path optimization was performed using a cubic Bezier curve method. The results of this refinement are illustrated in Figure 12. As shown, the optimized paths exhibit significantly reduced redundancy and improved smoothness.

Figure 12.

Optimized path simulation.

4.5. Discussion

Desirable motion paths are typically associated with attributes such as shorter path lengths, reduced running time, fewer iterations, and smoother paths. BI-RRT* improves planning efficiency by employing a dual-tree search mechanism, replacing the traditional single-direction expansion and thereby achieving a significant reduction in computational cost. Furthermore, the proposed cooperative expansion strategy generates higher-quality new nodes, thereby improving the convergence speed of the algorithm to some extent. The ChooseParent strategy and Rewire strategy comprehensively consider path length, path turning angle, and safety distances, ensuring path quality.

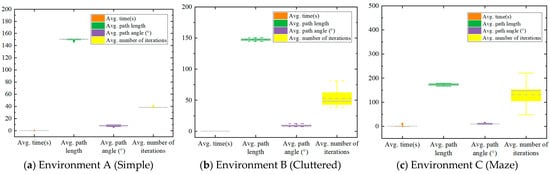

Figure 13 presents box plots of the performance metrics of CE-BI-RRT* over 50 runs in each of the three simulation environments. Observing Figure 13, it is evident that the algorithm exhibits consistent and robust performance across diverse scenarios. In Environment A, the algorithm completes path planning with the lowest path cost, minimal computation time, and fewer iterations. For Environment B, all performance metrics of the algorithm remain stable, despite a noticeable fluctuation in number of iterations. This fluctuation precisely reflects the impact of environmental changes on algorithm behavior, while also demonstrating the algorithm’s adaptability to handle increased environmental complexity. For Environment C, all metrics show a moderate increase. The relatively compact box plots corresponding to the three environments indicate low variance in algorithm performance, highlighting its reliability. Furthermore, the absence of significant outliers demonstrates that the CE-Bi-RRT* algorithm possesses strong resilience against random initialization and environmental variations across all scenarios.

Figure 13.

Box plots of the performance metrics of CE-BI-RRT* over 50 runs in each of the three simulation environments. (In the box plot, the solid line within each box denotes the median, and the dashed line indicates the mean).

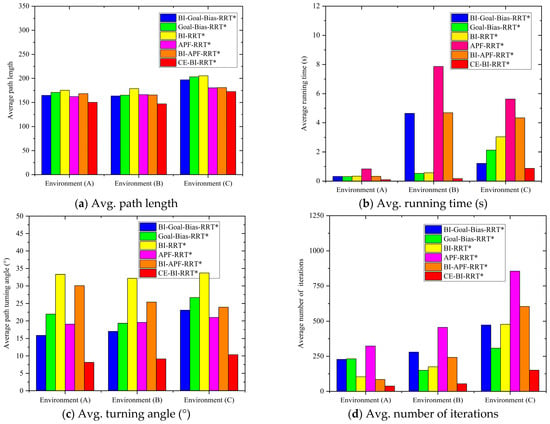

Figure 14 presents a comparison of average path length, average running time, average path turning angle and average number of iterations among all algorithms in three different environments. It can be clearly observed that the proposed algorithm significantly outperforms the other five algorithms in terms of all evaluation metrics, especially in the complex Environment C. In the maze environment, CE-BI-RRT* demonstrated improvements over five popular sampling-based path planning frameworks in multiple performance metrics. Specifically, it reduced average path lengths by 15.19%, 12.33%, 15.97%, 4.25%, and 4.48%, respectively, decreased computation time by 58.96%, 28.09%, 71.38%, 84.55%, and 79.95%, and lowered the average number of turning angles by 61.31%, 55.24%, 69.34%, 50.83%, and 56.87% across the compared algorithms.

Figure 14.

Simulation data comparison graph in three environments.

The simulation results highlight that CE-BI-RRT* offers an efficient navigation solution, capable of planning high-quality paths in environments densely populated with obstacles.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents CE-Bi-RRT*, an enhanced bidirectional RRT* algorithm tailored for autonomous drone navigation in constrained 2D environments. Building upon Bi-RRT*, the algorithm introduces a cooperative expansion strategy that enables the exploration trees to grow more effectively toward the goal by adaptively switching among direct expansion, intelligent deflection, and an improved artificial potential field method. Furthermore, the ChooseParent and Rewire mechanisms are enhanced by incorporating a unified cost function that jointly considers path length, turning angle (as a proxy for smoothness), and safety distance, complemented by a rotation-based optimization to increase clearance from obstacles after rewiring. The final trajectory is refined using cubic Bezier curves to ensure continuous curvature, a critical requirement for stable and flyable drone paths.

In a complex maze environment—a representative of challenging 2D scenarios—simulation results demonstrate that the proposed CE-Bi-RRT* algorithm significantly outperforms APF-RRT*, Goal-Bias-RRT*, Bi-RRT*, Bi-Goal-Bias-RRT*, and Bi-APF-RRT*. Specifically, CE-Bi-RRT* achieves 15.19–15.97% shorter path lengths, 58.96–84.55% faster computation times, and 50.83–69.34% smaller average turning angles. These improvements highlight its superior efficiency, smoothness, and real-time capability, making it particularly well-suited for time-sensitive and safety-critical UAV missions under fixed-altitude flight constraints.

This work is not without limitations. From an implementation perspective, the proposed algorithm has been designed in a modular fashion, making it theoretically compatible with common UAV autonomy frameworks such as PX4 + ROS2. Its core components—the cooperative expansion strategy, multi-objective cost function, and Bezier smoothing—are computationally lightweight and could, in principle, be deployed on onboard computers such as the NVIDIA Jetson series. The resulting trajectories are curvature-continuous and generally meet the input requirements of standard trajectory trackers in flight controllers. However, we acknowledge that actual integration and real-flight validation remain beyond the scope of this simulation-based study and are planned as key directions for future work.

While this study focuses on static 2D environments, several natural extensions could be explored in the future:

(1) Extension to 3D: The cooperative expansion strategy could be generalized to three-dimensional space, potentially incorporating altitude gradients for urban or forest navigation;

(2) Dynamic Obstacle Handling: Integrating velocity-aware collision checking could enable operation in environments with moving agents;

(3) Real-World Validation: Implementing CE-Bi-RRT* on a physical UAV platform would provide essential insights into its real-time performance and robustness under sensor noise and actuator delays.

Author Contributions

G.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. J.L.: Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Software, Data Curation. W.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number 2024JJ6519.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-4.0 to improve the language clarity and academic style of the abstract and introduction sections. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Key Parameters of the CE-Bi-RRT* Algorithm

| Parameter | The full name and symbol of this parameter | Value |

| p | The initial dynamic direct connection probability | 0.8 |

| ffail | The failure count threshold | 100 |

| The expansion step size 1 | 2.0 | |

| The expansion step size 2 | 2.0 | |

| dmin | The safe distance | 1.0 |

| \ | Maximum number of iterations | 1000 |

| R | Rewiring neighborhood radius | 5.0 |

| The scaling factors for the attractive | 1.0 | |

| The scaling factors for the repulsive | 5.0 | |

| The effective range of the obstacle’s repulsion | 10.0 | |

| β | The weight coefficients of the | 0.6 |

| γ | The weight coefficients of the | 0.3 |

| δ | The weight coefficients of the | 0.1 |

Abbreviations

| UAVs | Unmanned aerial vehicles |

| RRT* | Rapidly exploring random tree star algorithm |

| BI-RRT* | Bi-directional RRT* algorithm |

| APF-RRT* | Artificial potential field-based RRT* algorithm |

| BI-APF-RRT* | Bi-directional artificial potential field-based RRT* algorithm |

| Goal-Bias-RRT* | Goal-biased RRT* algorithm |

| BI-Goal-Bias-RRT* | Bi-directional goal-biased RRT* algorithm |

| CE-BI-RRT* | Bi-directional rapid exploration random tree algorithm based on cooperative expansion strategy |

References

- Nakao, N.; Suzuki, H.; Kitajima, T.; Kuwahara, A.; Yasuno, T. Path Planning and Traveling Control for Pesticide-Spraying Robot in Greenhouse. J. Signal Process. 2017, 21, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, P.; Kotte, D.; Srinath, A.; Kalyan, K.B. Development of Smart Pesticide Spraying Robot. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 8, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundar, A.V.S.S.; Yedukondalu, G. Robotic path planning and simulation by jacobian inverse for industrial applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, P.; Qiu, B.; Han, Y. SDA-RRT*Connect: A Path Planning and Trajectory Optimization Method for Robotic Manipulators in Industrial Scenes with Frame Obstacles. Symmtry 2025, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Huang, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, C. Route Planning for Military Ground Vehicles in Road Networks under Uncertain Battlefield Environment. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 2865149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsav, A.; Abhishek, A.; Suraj, P.; Badhai, R.K. An IoT Based UAV Network for Military Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 Sixth International Conference on Wireless Communications, Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), Chennai, India, 25–27 March 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; Volume 12, pp. 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chua, S.E.; Su, E.L.M.; Yeong, C.F. Investigation of Effects of Path Planning Algorithms on Mobile Robot’s Performance. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, Bristol, UK, 25–27 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.D.; Sun, J.Q. A New Algorithm Based on Dijkstra for Vehicle Path Planning Considering Intersection Attribute. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19761–19775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.; Howard, T.M.; Likhachev, M. Motion planning in urban environments: Part I. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; Volume 25, pp. 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastelli, J.; Lattarulo, R.; Nashashibi, F. Dynamic trajectory generation using continuous-curvature algorithms for door-to-door assistance vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Dearborn, MI, USA, 8–11 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, T.; Lange, A.; Cramer, S. Adaptive and efficient lane change path planning for automated vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 19th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1–4 November 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Li, W. A path planning method based on deep reinforcement learning for crowd evacuation. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2024, 15, 2925–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, J.; Kuang, L.; Han, X.; Xue, H. Improved robot path planning method based on deep reinforcement learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Luo, X.; Luo, Q. An Optimized Probabilistic Roadmap Algorithm for Path Planning of Mobile Robots in Complex Environments with Narrow Channels. Sensors 2022, 22, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, O.; Berntorp, K.; Tsiotras, P. Sampling-based Algorithms for Optimal Motion Planning Using Closed-loop Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May 2017–3 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Feng, C. Fast-RRT*: An Improved Motion Planner for Mobile Robot in Two-Dimensional Space. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 17, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fu, S. Path planning of mobile robot based on improved RRT* algorithm. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 49, 31–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, R.; Han, Y.; Tan, H.; Meng, J. Path planning of mobile robot based on Improved RRT Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Hangzhou, China, 22–24 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 4741–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chen, X.; Liang, X. UAV trajectory planning based on bi-directional APF-RRT algorithm with goal-biased. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213 Pt C, 119137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammell, J.D.; Srinivasa, S.S.; Barfoot, T.D. Informed RRT*: Optimal Sampling-based Path Planning Focused via Direct Sampling of an Admissible Ellipsoidal Heuristic. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 4297–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, G.; Tong, X.; Sun, Y. SOF-RRT*: An improved path planning algorithm using spatial offset sampling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. Int. J. Intell. Real-Time Autom. 2023, 126 Pt B, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Song, T.; Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Ren, P. Bidirectional rapidly exploring random tree path planning algorithm based on adaptive strategies and artificial potential fields. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 148, 110393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Ramalingam, B.; Mohan, R.E. A hybrid sampling-based RRT* path planning algorithm for autonomous mobile robot navigation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ju, D.; Xu, F.; Feng, C. Bi-RRT*: An Improved Bi-directional RRT* Path Planner for Robot in Two-Dimensional Space. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2023, 18, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, J.; Meng, M.Q.-H. Multi-tree guided efficient robot motion planning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 209, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, K.; Lu, G.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, S. Path Planning of UAV Delivery Based on Improved APF-RRT* Algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1624, 042004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Dong, L.; Dai, J.K. Collision avoidance trajectory planning for a dual-robot system: Using a modified APF method. Robot. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Res. Robot. Artif. Intell. 2024, 42, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, X.; Wang, W.; Cheng, Q.; Shen, Y. A Simplified Car-following Model Based on the Artificial Potential Field. Procedia Eng. 2016, 137, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Qi, J.; Hong, S. DBVS-APF-RRT: A global path planning algorithm with ultra-high-speed generation of initial paths and high optimal path quality. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249 Pt A, 123571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, B.; Su, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Autonomous dispatch trajectory planning of carrier-based vehicles: An iterative safe dispatch corridor framework. Def. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavalle, S.M. Rapidly-Exploring Random Trees: A New Tool for Path Planning; Technical Report; Department of Computer Science, Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, A.H.; Ayaz, Y. Intelligent bidirectional rapidly-exploring random trees for optimal motion planning in complex cluttered environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybus, T.; Prokopczuk, J.; Wojtunik, M.; Aleksiejuk, K.; Musiał, J. Application of bidirectional rapidly exploring random trees (BiRRT) algorithm for collision-free trajectory planning of free-floating space manipulator. Robotica 2022, 40, 4326–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).