An Online Human-Aware Behavior Planning Method for Nondeterministic UAV System Under Probabilistic Model Checking

Highlights

- The Markov decision process is used to construct the global probabilistic behavior model of the UAV offline, but a finite state automaton in finite horizon is dynamically constructed online.

- A value iterative algorithm is introduced to solve the optimal behavior plan online within the finite horizon, then an infinite horizon planning and execution algorithm is formed.

- This paper proposes an online human-aware behavior planning method to enable a UAV dynamically satisfy the high-level LTL task description from the human collaborators, which has the potential to be applied to human–UAV collaboration.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Contribution

2. Preliminaries

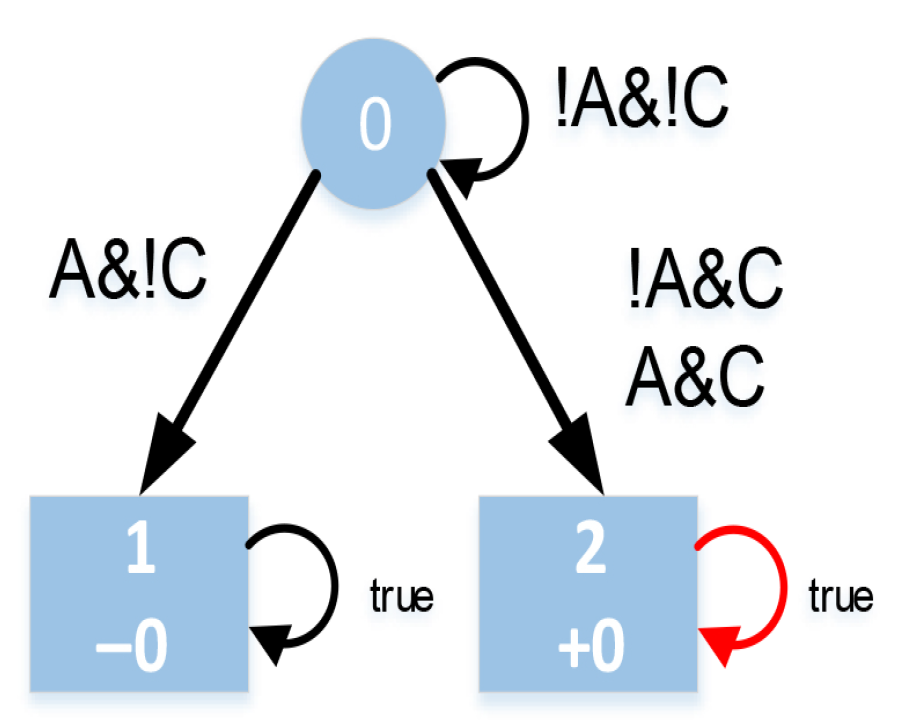

2.1. Linear Temporal Logic

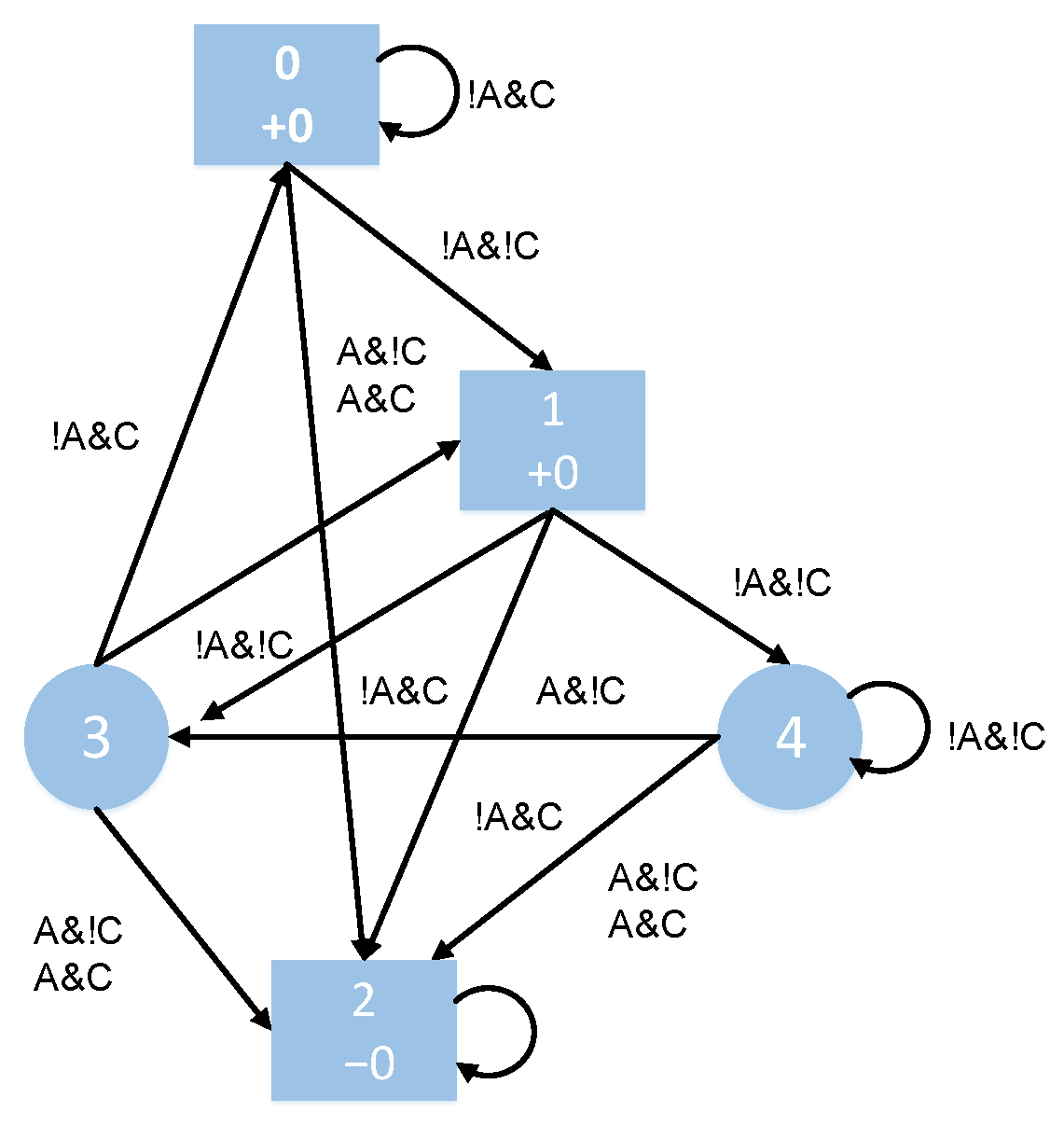

2.2. Probabilistic Behavior Model

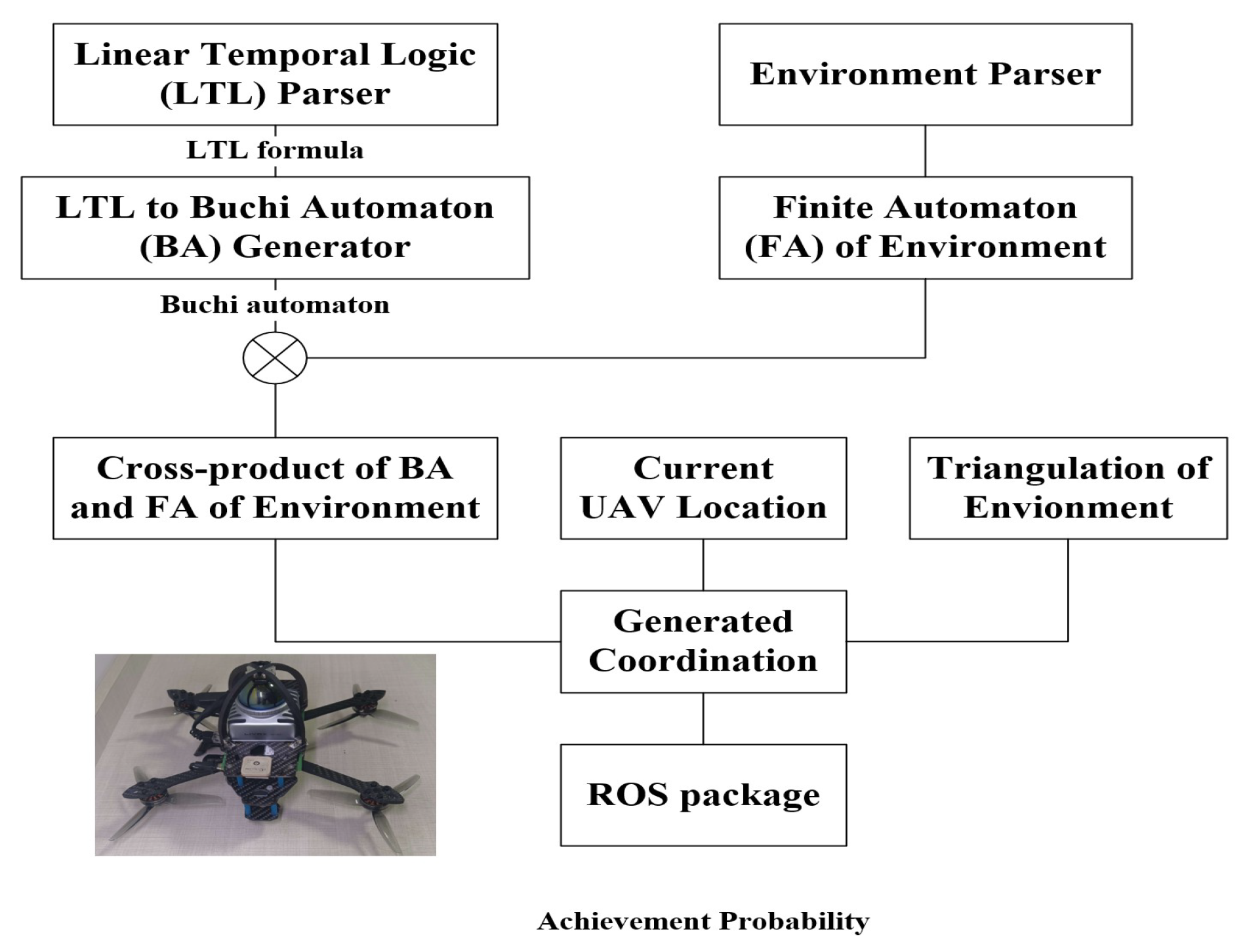

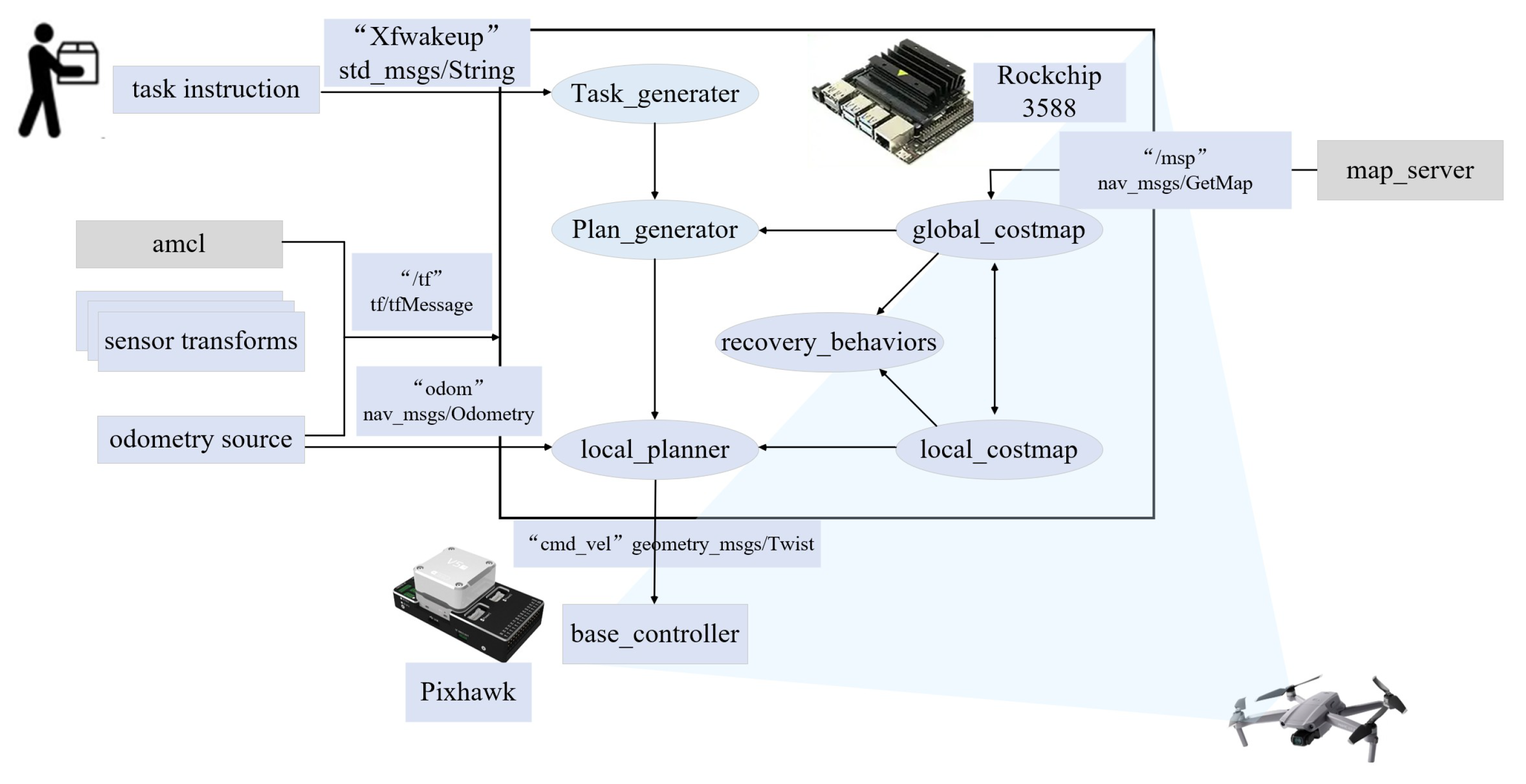

3. Proposed Framework

- (1)

- Task description aims to describe the high-level task instructions input by human in natural language as the LTL formula.

- (2)

- Task interpretation is responsible for converting the LTL formula into an automaton, which can be understood by the UAV.

- (3)

- Probabilistic behavior modeling is used to model the probabilistic behavior of the UAV.

- (4)

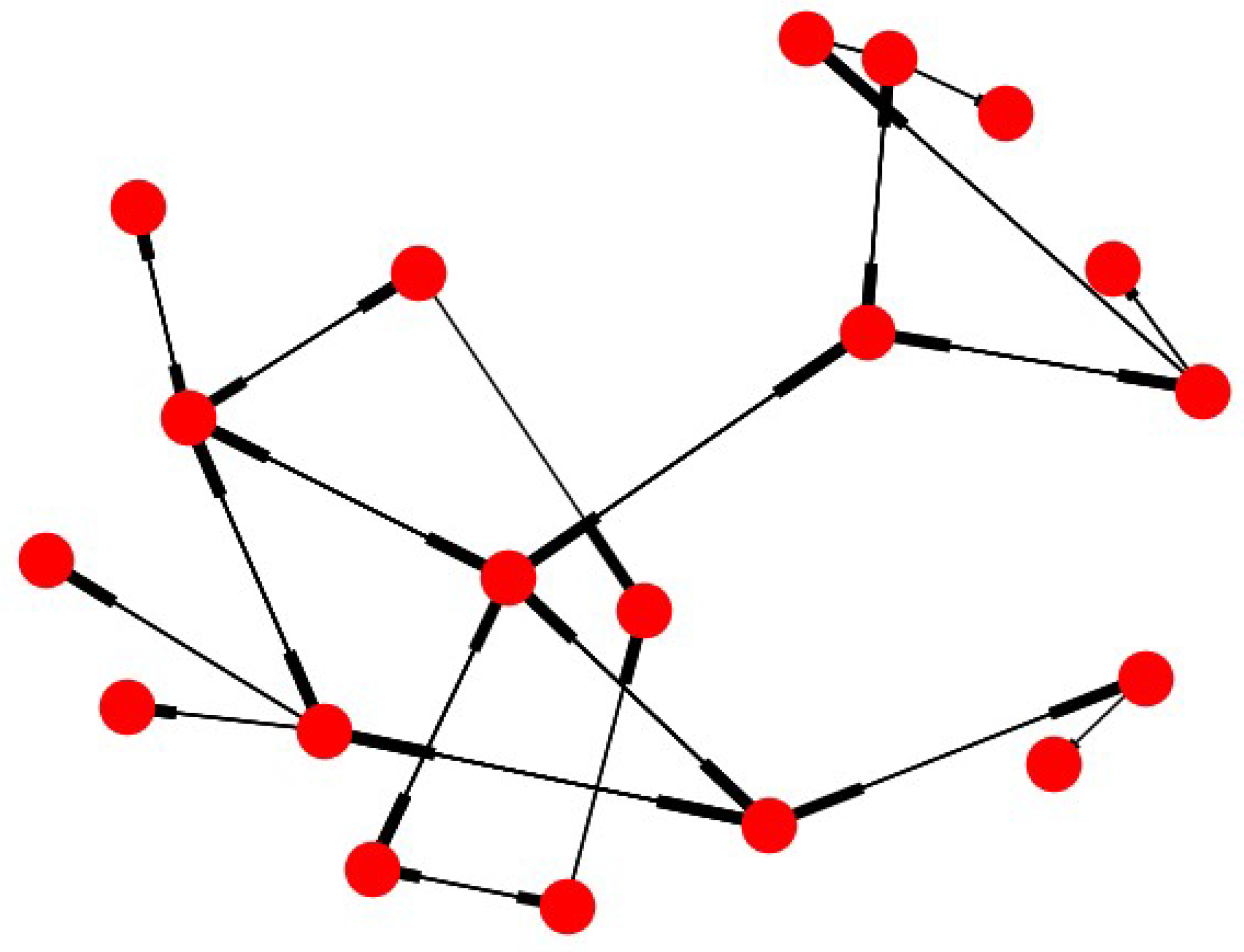

- The probabilistic behavior model is synthesized with a task automaton in the form of a Cartesian product system.

- (5)

- In the plan generation, the behavior plan is generated with a specific strategy generation algorithm.

- (6)

- The corresponding task achievement probability is given to the task monitor.

4. Methodology

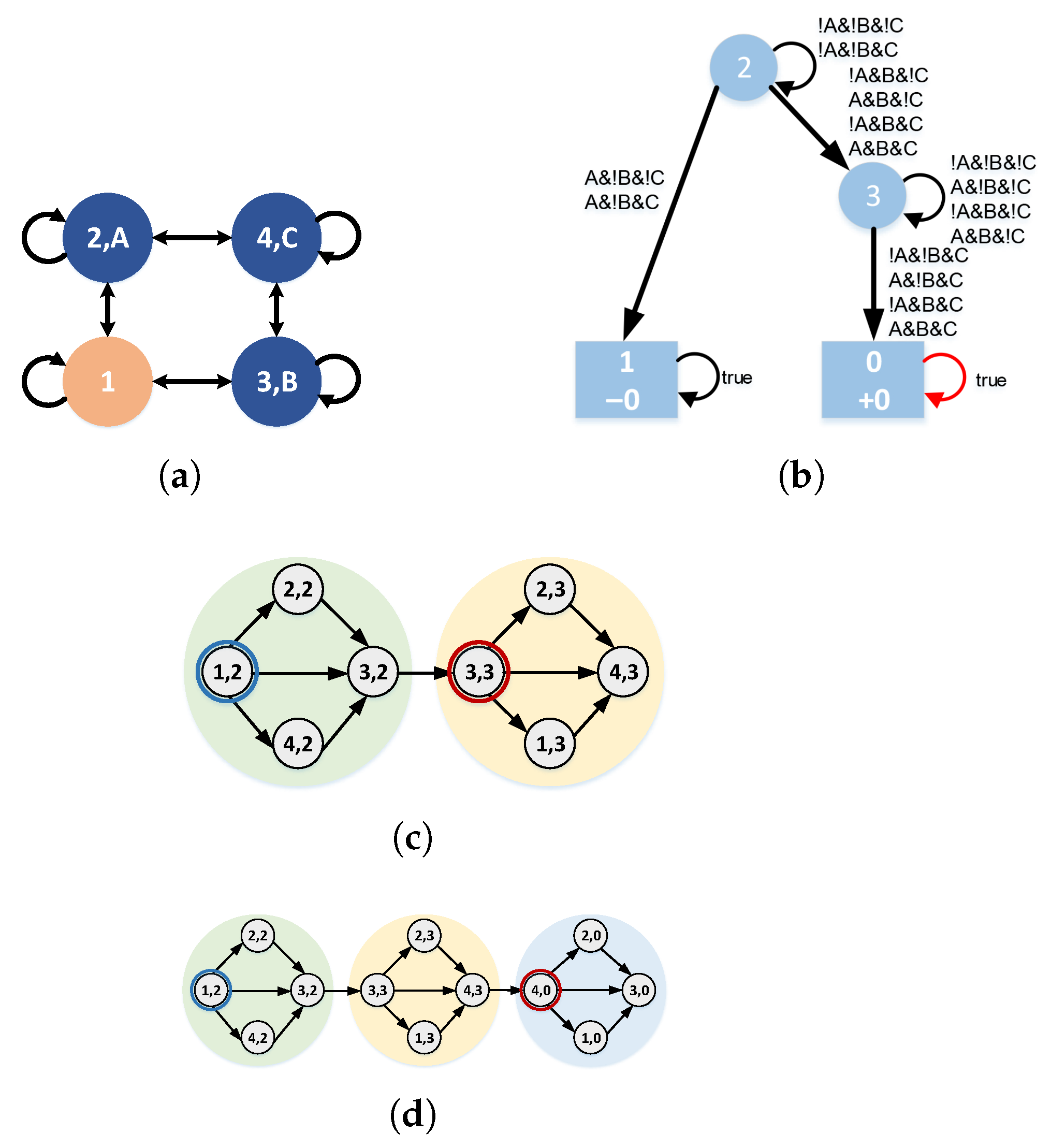

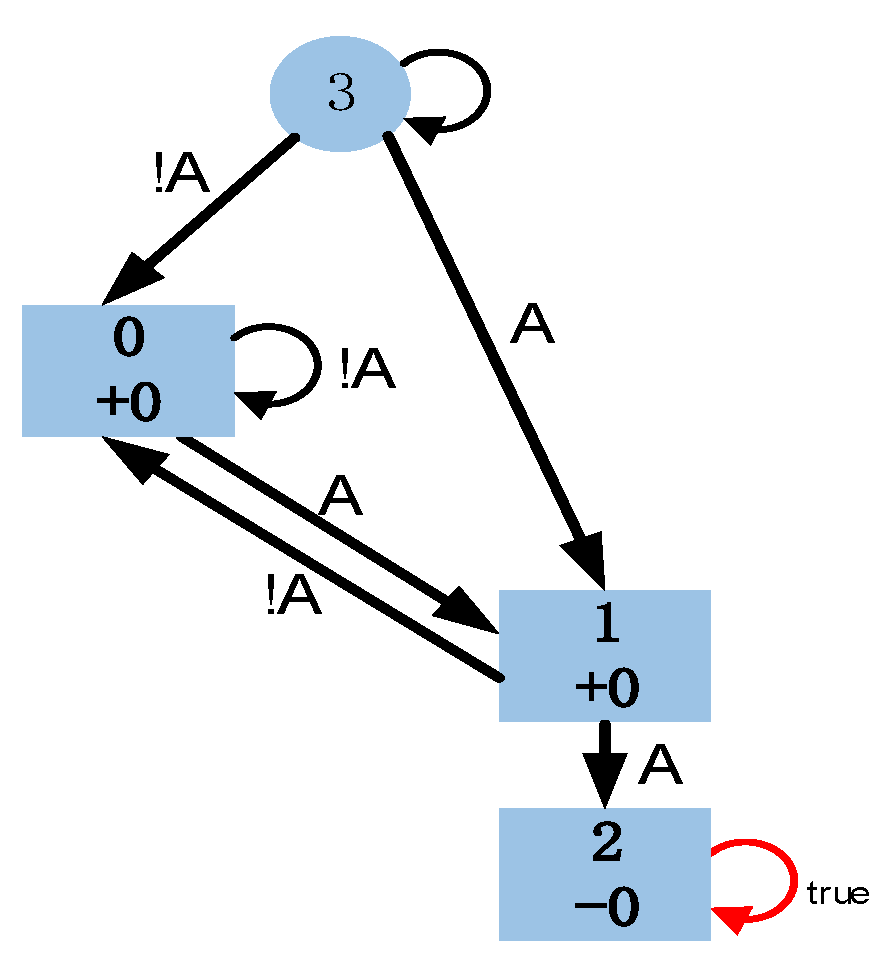

4.1. Product System Based on Finite State Automaton

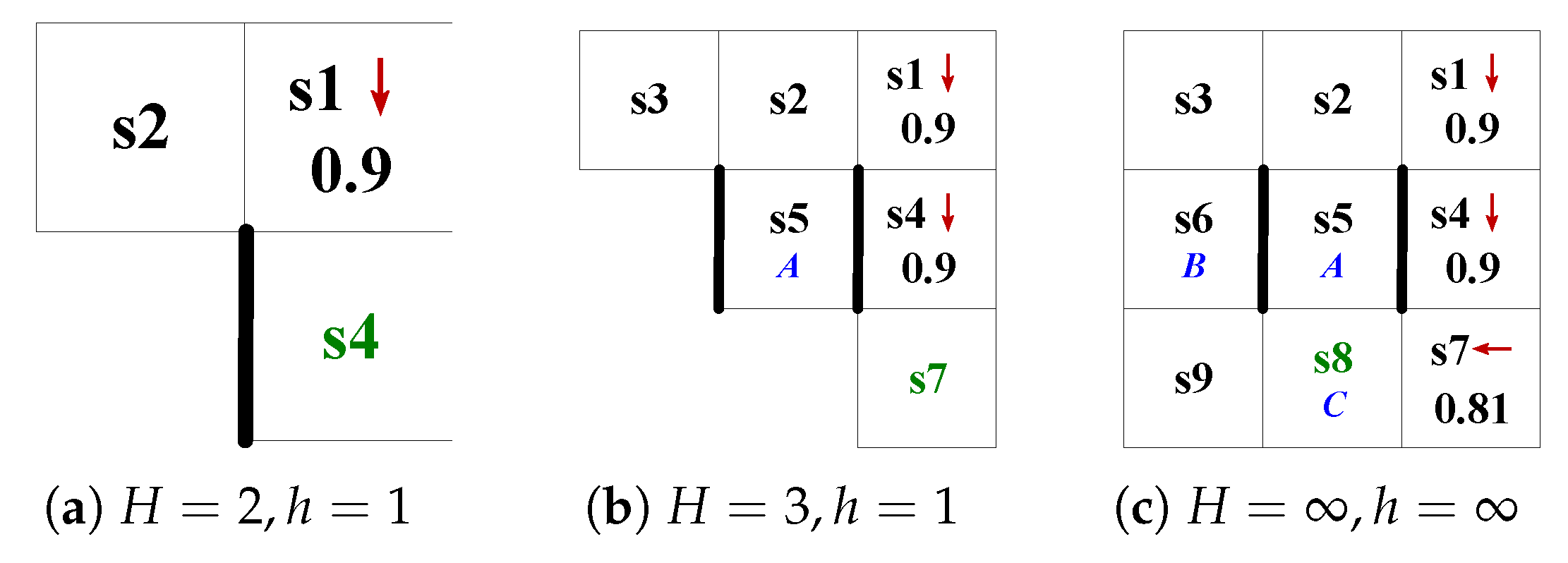

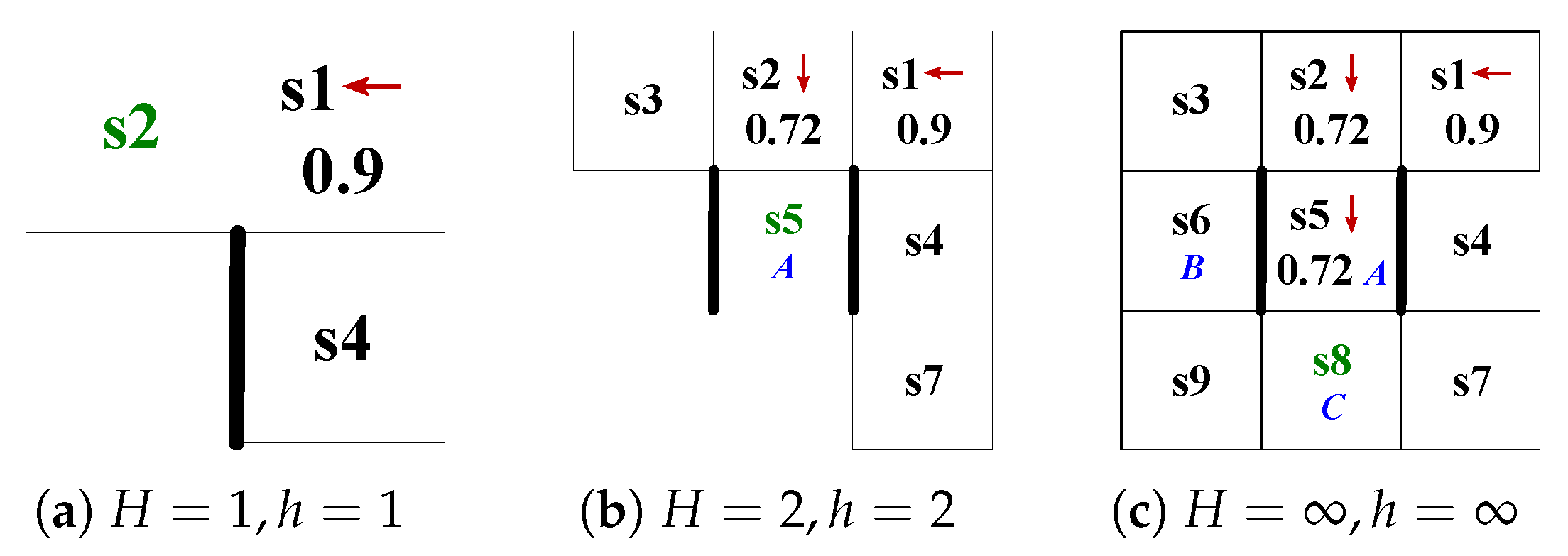

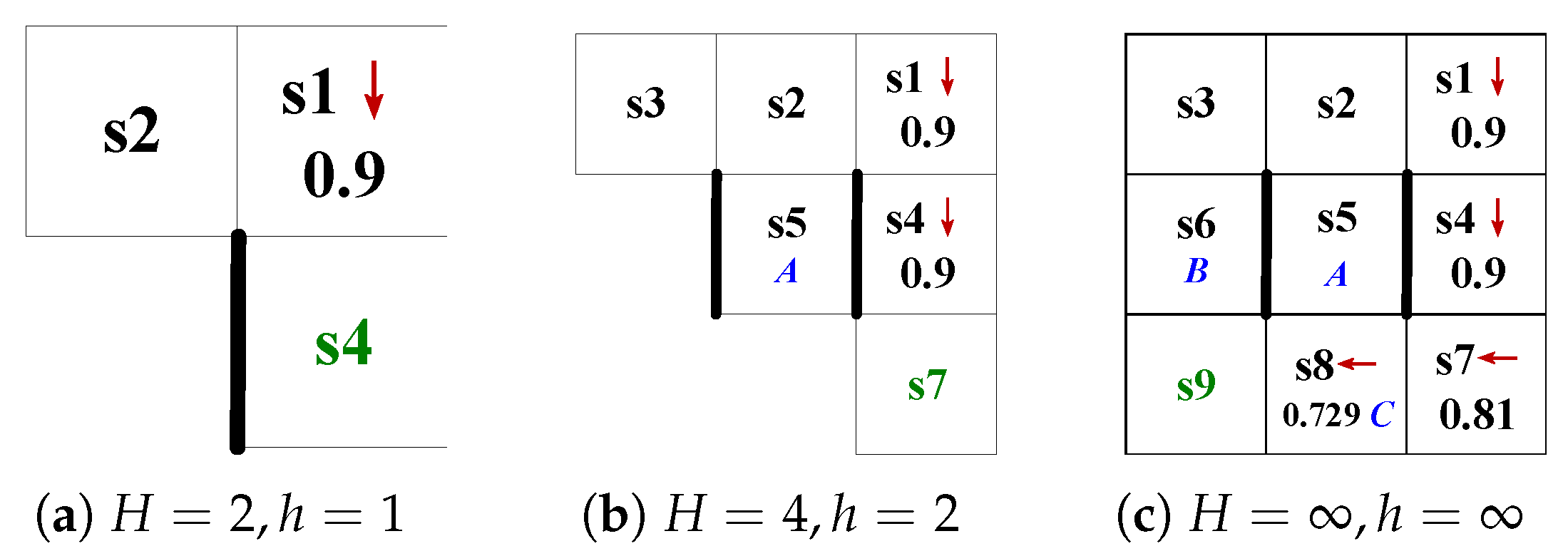

4.1.1. Finite State Automaton Within h

- is a finite set of states;

- is the initial state within the time domain;

- ;

- ;

- For all , if and only if , and ;

- Finally, and ;

- , , and is the minimum.

4.1.2. Product System Within H

- is a finite set of states;

- , is the initial state of the MDP within H;

- ;

- ;

- For all , if and only if , and , , ;

- Finally, and .

4.1.3. Determining the Target State Within H

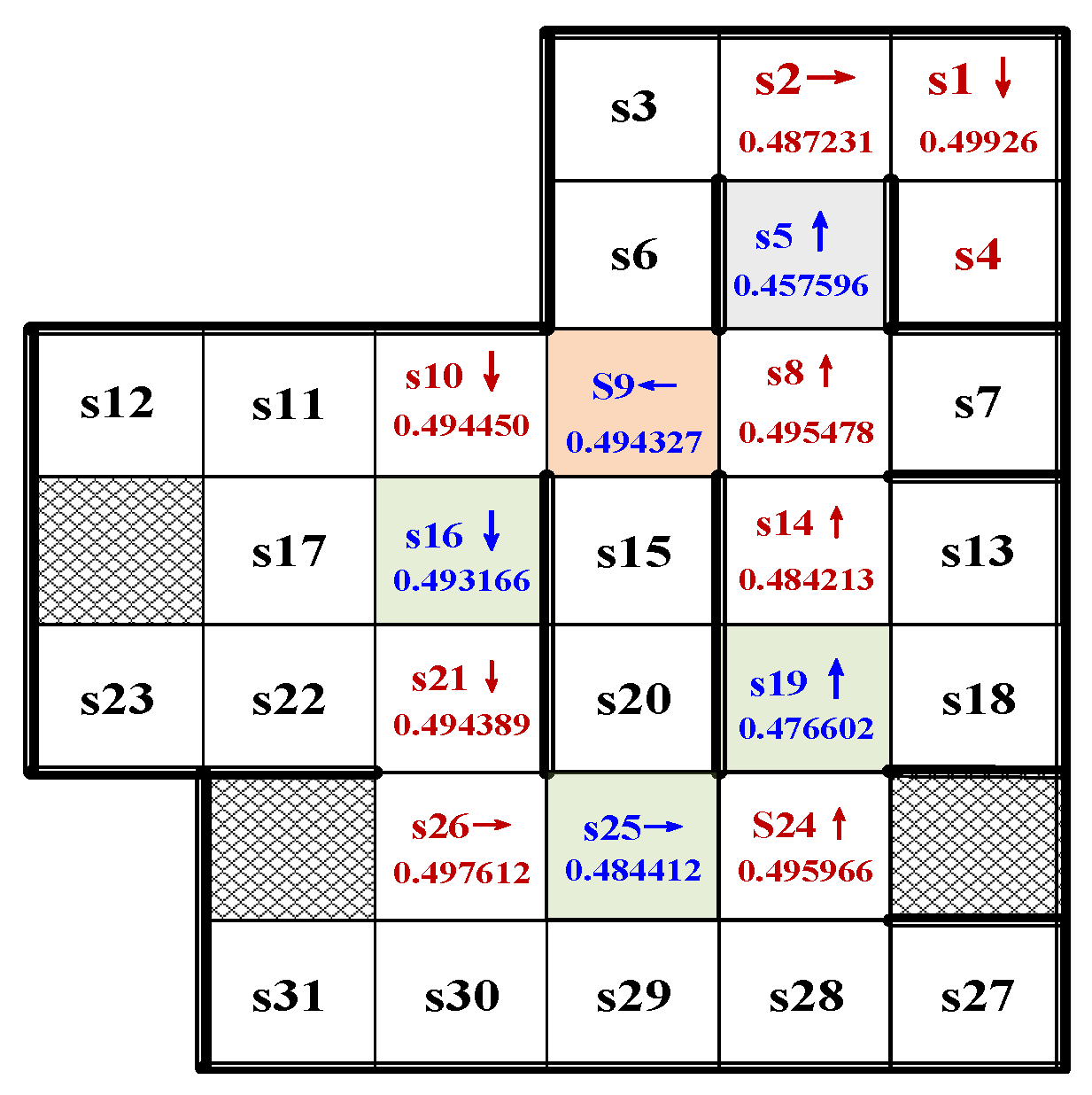

4.2. Behavior Planning Within the Time Domain H

| Algorithm 1 Procedure of . |

|

4.3. Tasks Execution Across Infinite Time

| Algorithm 2 Infinite horizon planning and execution. |

|

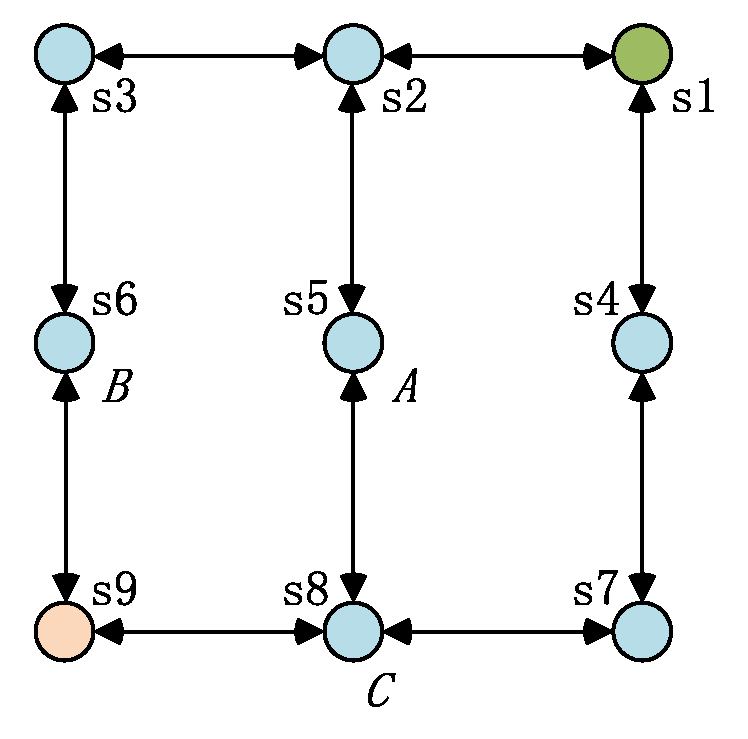

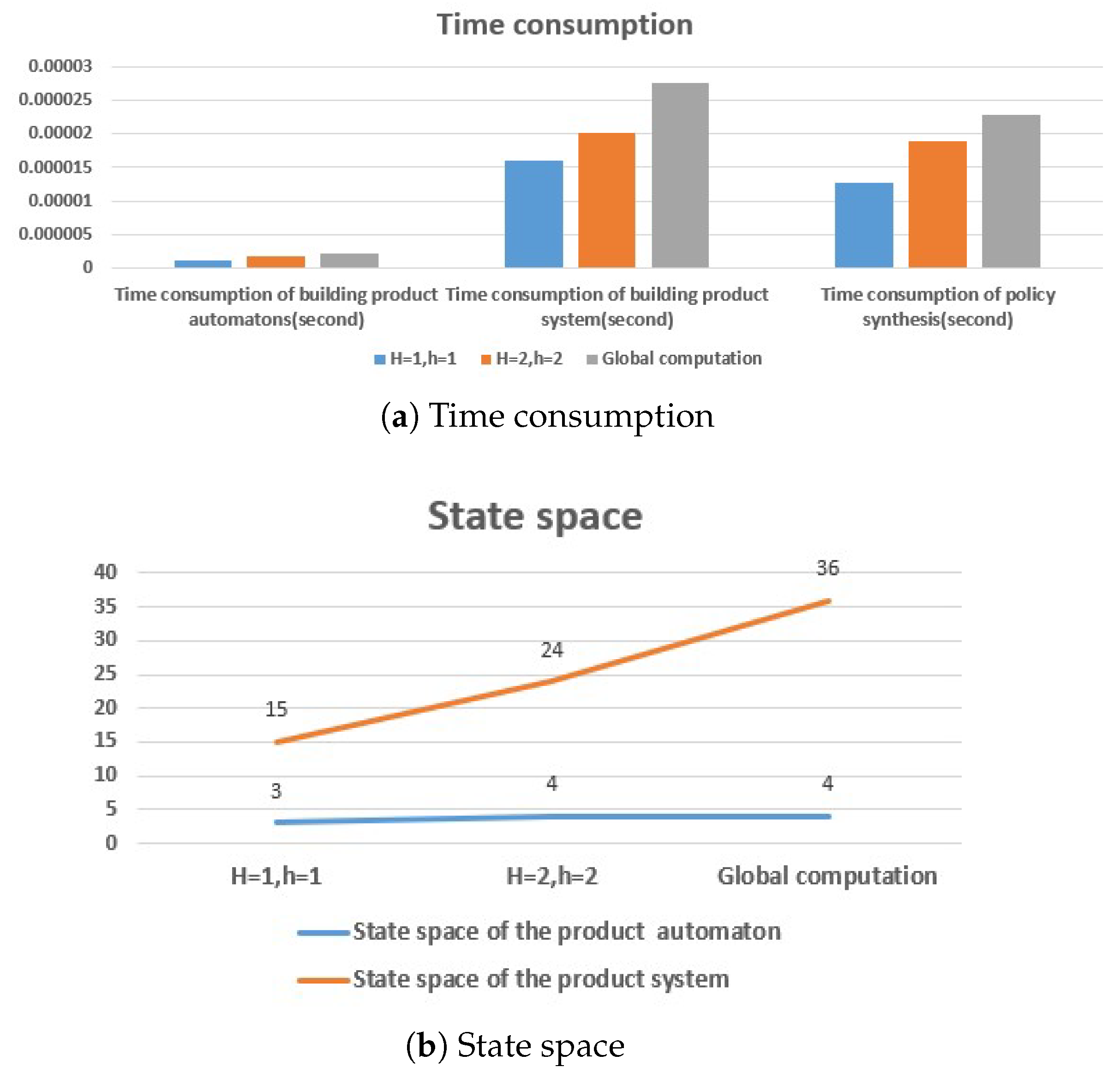

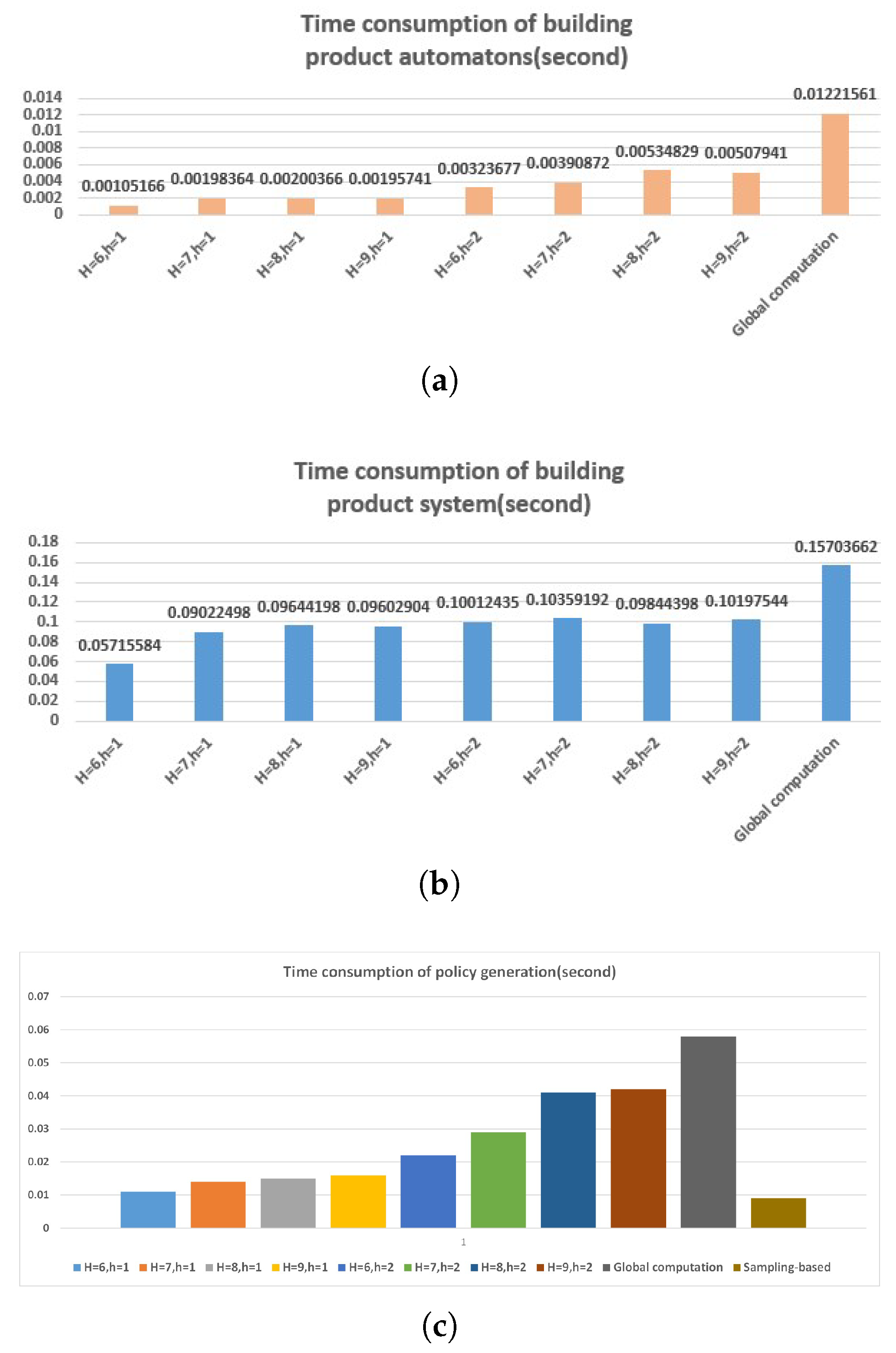

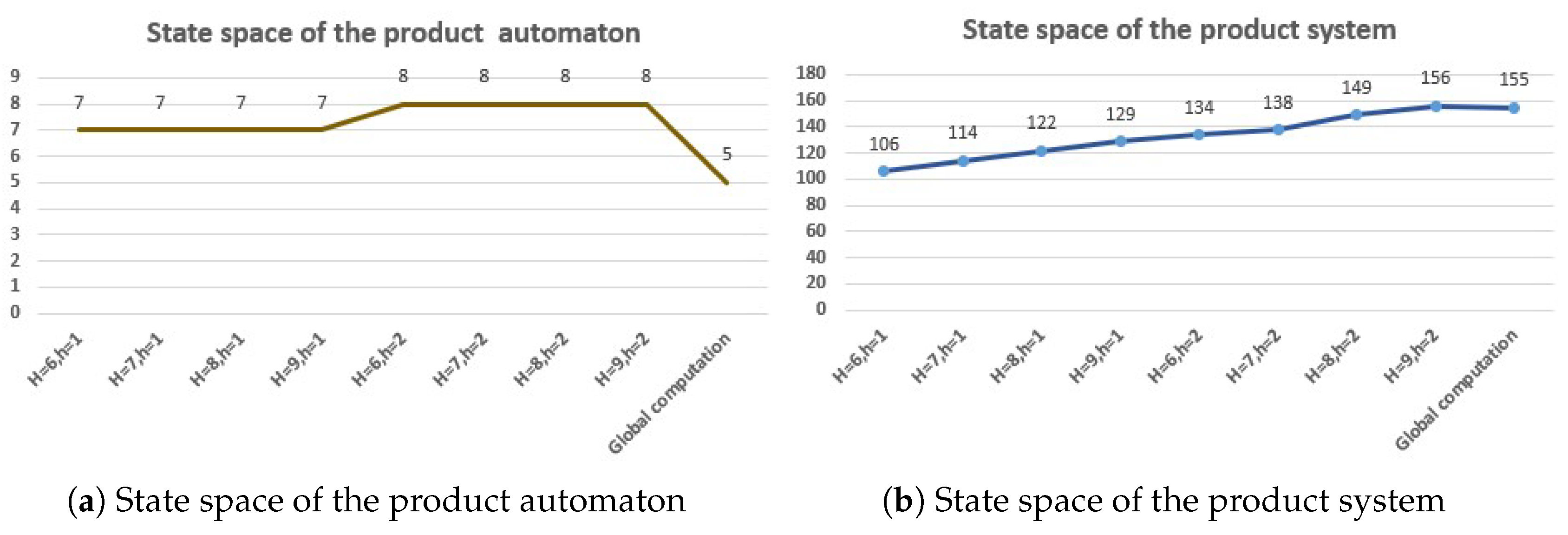

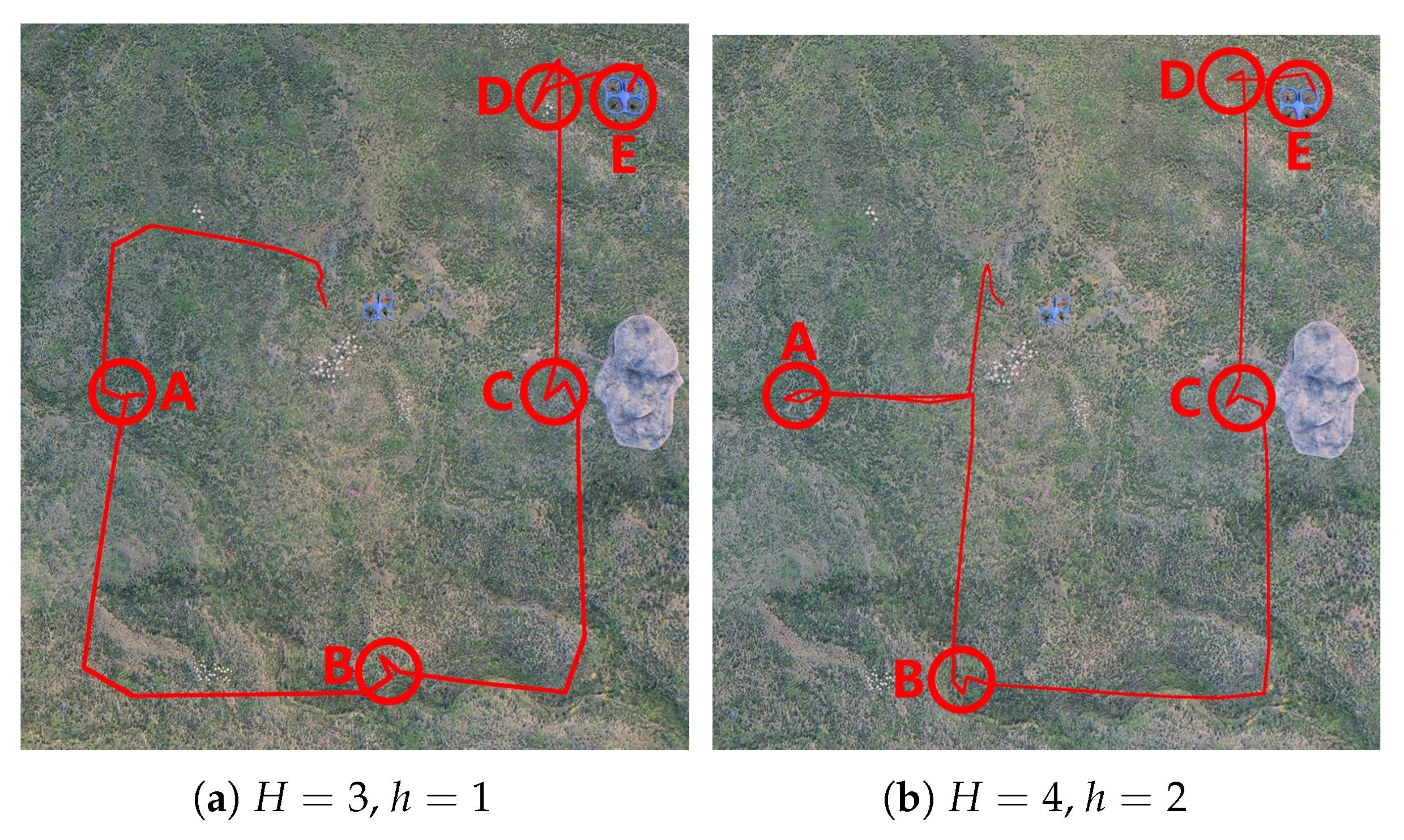

5. Simulation and Analysis

5.1. Settings

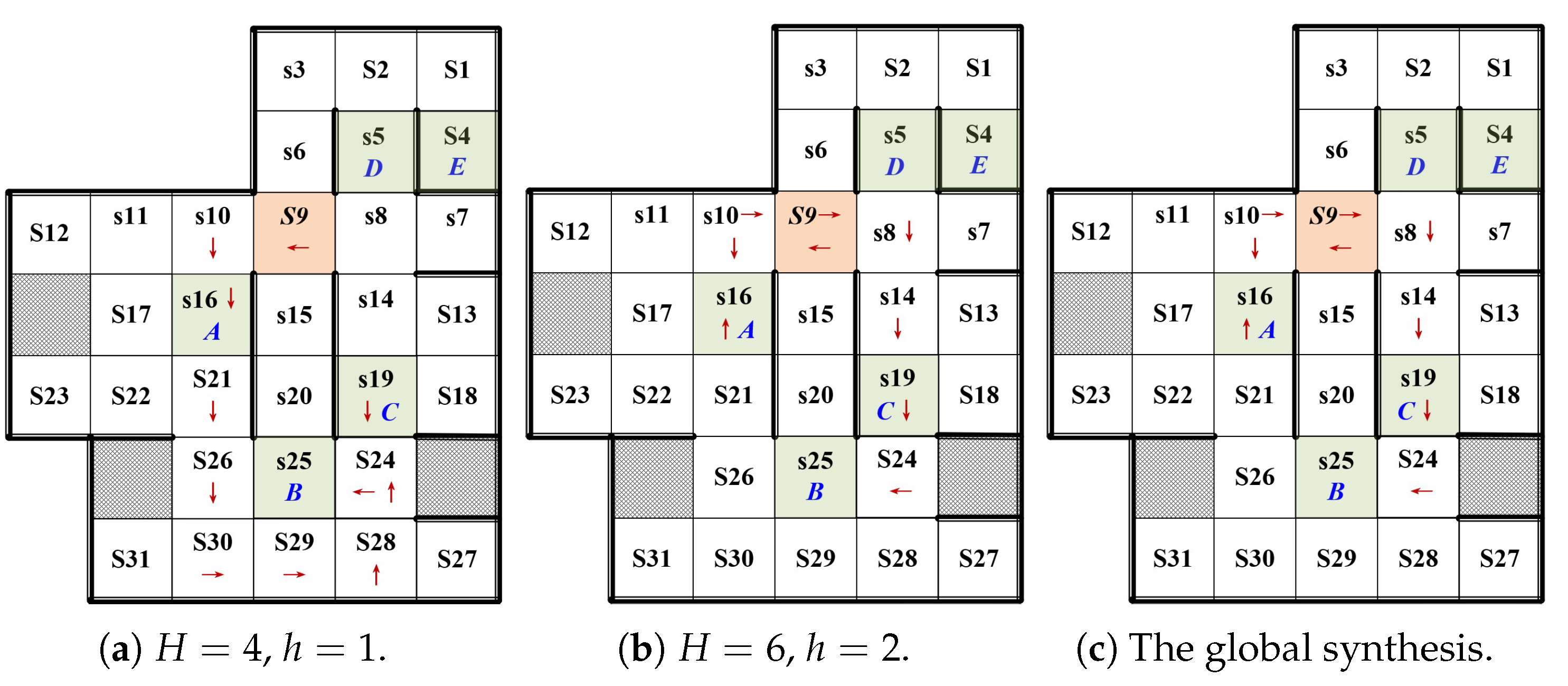

5.2. Correctness and Effectiveness

5.3. Result Analysis

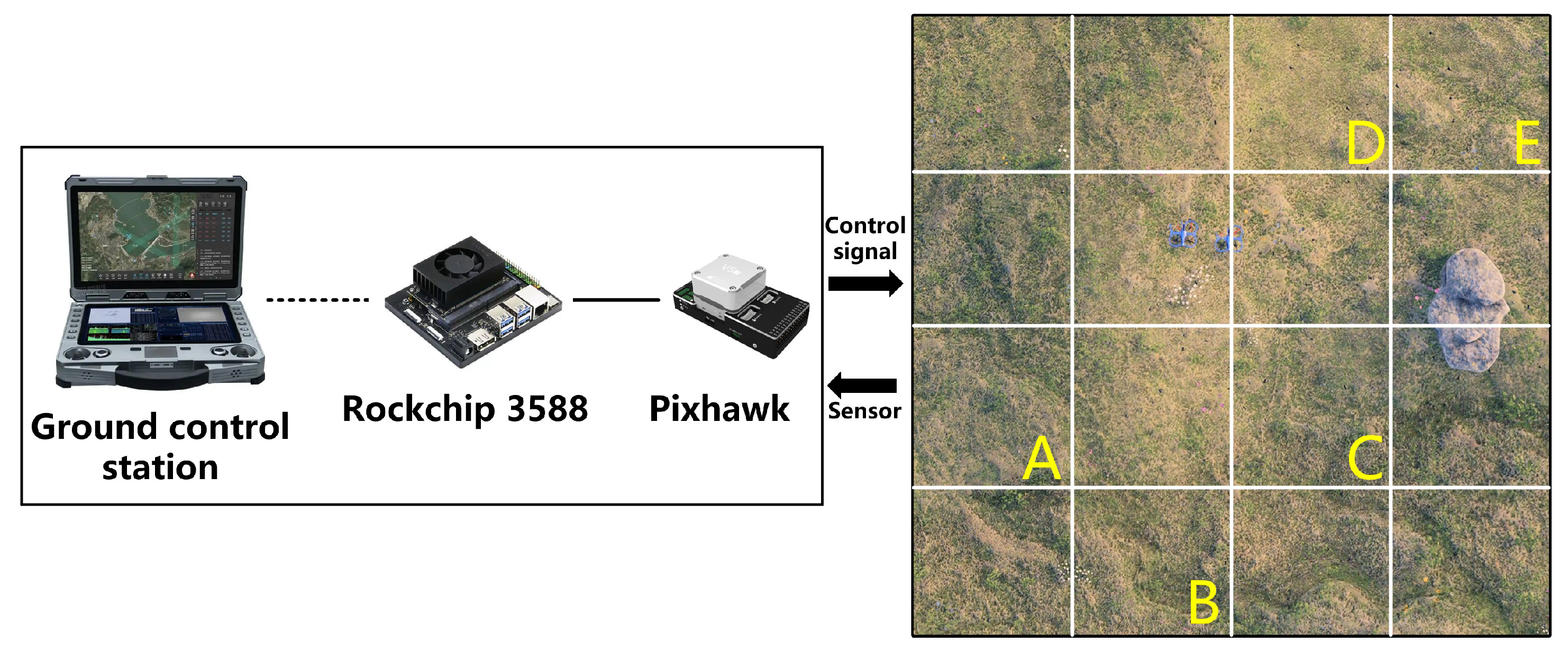

6. Experiments

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, Y.; Huang, L.; LiWang, M. Joint Power Control and Time Allocation for UAV-Assisted IoV Networks Over Licensed and Unlicensed Spectrum. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, F.; Wang, D.; Chen, B.; Li, T.; Zhang, R. Performance Analysis and Optimization Design of AAV-Assisted Vehicle Platooning in NOMA-Enhanced Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 8810–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Yao, B.; Xiong, B.; Zhou, Z. Towards Shared Autonomy Framework for Human-Aware Motion Planning in Industrial Human-Robot Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Hong Kong, China, 20–21 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R. Integrated Optimization of Ground Support Systems and UAV Task Planning for Efficient Forest Fire Inspection. Drones 2025, 9, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, R.; Chatila, R.; Clodic, A.; Fleury, S.; Herrb, M.; Montreuil, V.; Sisbot, E.A. Towards human-aware cognitive robots. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Cognitive Robotics Workshop, Washington, DC, USA, 17–19 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Chang, T.; Li, X.; Yin, Q.; Hu, Y. Vision-Language Navigation: A Survey and Taxonomy. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2108.11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, P.A.; Shah, J.A. Analyzing the effects of human-aware motion planning on close-proximity human–robot collaboration. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigner, P.; McCarragher, B. Human integration into robot control utilising potential fields. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 25 April 1997; Volume 1, pp. 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall, J.W.; Goodrich, M.A. Characterizing efficiency of human robot interbehavior: A case study of shared-control teleoperation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; Volume 2, pp. 1290–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, C.; Katoen, J.-P. Principles of Model Checking; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pronk, C. Model Checking, the technology and the tools. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on System Engineering and Technology (ICSET), Bandung, Indonesia, 11–12 September 2012; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forejt, V.; Kwiatkowska, M.; Norman, G.; Parker, D. Automated Verification Techniques for Probabilistic Systems. In Formal Methods for Eternal Networked Software Systems: 11th International School on Formal Methods for the Design of Computer, Communication and Software Systems, SFM 2011, Bertinoro, Italy, 13–18 June 2011; Advanced Lectures; Bernardo, M., Issarny, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6659, pp. 53–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kantaros, Y.; Zavlanos, M.M. A Temporal Logic Optimal Control Synthesis Algorithm for Large-Scale Multi-Robot Systems. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2020, 39, 812–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloetzer, M.; Belta, C. A Fully Automated Framework for Control of Linear Systems from Temporal Logic Specifications. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Maly, M.R.; Kavraki, L.E.; Vardi, M.Y. Behavior planning with Complex Goals. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress-Gazit, H.; Fainekos, G.E.; Pappas, G.J. Temporal-Logic-Based Reactive Mission and Behavior planning. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, R.; Cowlagi, R.V. Randomized Sampling-Based Trajectory Optimization for UAVs to Satisfy Linear Temporal Logic Specifications. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lazar, M.; Belta, C. LTL receding horizon control for finite deterministic systems. Automatica 2014, 50, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.C.; Belta, C.; Cassandras, C.G. Receding horizon surveillance with temporal logic specifications. In Proceedings of the 49th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Atlanta, GA, USA, 15–17 December 2010; pp. 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M.; Peng, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, H.; Kan, Z. Receding Horizon Control Based Online Behavior planning with Partially Infeasible LTL Specifications. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2007.12123. [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy, A.; Belta, C. Receding horizon temporal logic control in dynamic environments. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2014, 33, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumova, J.; Dimarogonas, D.V. A Receding Horizon Approach to Multi-Robot Planning from Local LTL Specifications. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1403.4174. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpiromsarn, T.; Topcu, U.; Murray, R.M. Receding horizon control for temporal logic specifications. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM International Conference on Hybrid Systems: Computation and Control—HSCC’10, Stockholm, Sweden, 12–15 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nenchev, V.; Belta, C. Receding horizon robot control in partially unknown environments with temporal logic constraints. In Proceedings of the 2016 European Control Conference (ECC), Aalborg, Denmark, 29 June–1 July 2016; pp. 2614–2619. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpiromsarn, T.; Topcu, U.; Ozay, N.; Xu, H.; Murray, R.M. TuLiP: A software toolbox for receding horizon temporal logic planning. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Hybrid Systems: Computation and Control—HSCC’11, Chicago, IL, USA, 12–14 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, J.A.; Carrillo, E.; Xu, H. Hierarchal Application of Receding Horizon Synthesis and Dynamic Allocation for UAVs Fighting Fires. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78868–78880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.; Carrillo, E.; Xu, H. Receding Horizon Synthesis and Dynamic Allocation of UAVs to Fight Fires. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Advanced Robotics and its Social Impacts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 21–24 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.; Fitch, R.; Sukkarieh, S. Online Task Planning and Control for Fuel-Constrained Aerial Robots in Wind Fields. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, M.; Kan, Z.; Xiao, S. Model-Free Reinforcement Learning for Motion Planning of Autonomous Agents with Complex Tasks in Partially Observable Environments. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2024, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumova, J.; Dimarogonas, D.V. Multi-robot planning under local LTL specifications and event-based synchronization. Automatica 2016, 70, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Er, M.J.; Guo, C. Online time-optimal path and trajectory planning for robotic multipoint assembly. Assem. Autom. 2021, 41, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhou, Z.; Li, L.; Xiao, S.; Kan, Z. Reinforcement learning with soft temporal logic constraints using limit-deterministic generalized Büchi automaton. J. Autom. Intell. 2025, 4, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, T.; Blahoudek, F.; Křetínský, M.; Strejček, J. Effective Translation of LTL to Deterministic Rabin Automata: Beyond the (F,G)-Fragment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boker, U.; Lehtinen, K.; Sickert, S. On the Translation of Automata to Linear Temporal Logic; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, J.; Wang, P.; Peng, Y.; Yin, Q. An Online Human-Aware Behavior Planning Method for Nondeterministic UAV System Under Probabilistic Model Checking. Drones 2025, 9, 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120832

Zhu J, Wang P, Peng Y, Yin Q. An Online Human-Aware Behavior Planning Method for Nondeterministic UAV System Under Probabilistic Model Checking. Drones. 2025; 9(12):832. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120832

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Jiancheng, Peng Wang, Yong Peng, and Quanjun Yin. 2025. "An Online Human-Aware Behavior Planning Method for Nondeterministic UAV System Under Probabilistic Model Checking" Drones 9, no. 12: 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120832

APA StyleZhu, J., Wang, P., Peng, Y., & Yin, Q. (2025). An Online Human-Aware Behavior Planning Method for Nondeterministic UAV System Under Probabilistic Model Checking. Drones, 9(12), 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120832