Abstract

This paper focuses on the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)-aided mobile networks, where multiple ground mobile users (GMUs) desire to upload data to a UAV. In order to maximize the total amount of data that can be uploaded, we formulate an optimization problem to maximize the uplink throughput by optimizing the UAV’s trajectory, under the constraints of the available energy of the UAV and the quality of service (QoS) of GMUs. To solve the non-convex problem, we propose a deep Q-network (DQN)-based method, in which we employ the iterative updating process and the Experience Relay (ER) method to reduce the negative effects sequence correlation on the training results, and the -greedy method is applied to balance the exploration and exploitation, for achieving the better estimations of the environment and also taking better actions. Different from previous works, the mobility of the GMUs is taken into account in this work, which is more general and closer to practice. Simulation results show that the proposed DQN-based method outperforms a traditional Q-Learning-based one in terms of both convergence and network throughput. Moreover, the larger battery capacity the UAV has, the higher uplink throughput can be achieved.

1. Introduction

Recently, due to their cost-effectiveness, mobility, and operational flexibility, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been applied in a variety of areas such as surveillance, surveying, commodities delivery, searching and rescuing, as well as emergency wireless coverage. By serving as airborne relays, data collectors, and aerial base stations (ABSs), UAVs can be deployed in wireless networks to assist the wireless information transmissions. Compared to ground base stations, UAV is more flexible, which is capable of establishing a good Line of Sight (LoS) link to construct stronger communication channels for the ground mobile users (GMUs) [1]. Consequently, the data rate of the wireless network can be greatly increased by the help of UAVs. Actually, when a UAV acts as an ABS, it can fly to and fro to provide flexible coverage services. However, due to the limited resources, including available energy and time, the UAV’s trajectory should be carefully planned to meet different goals, such as maximizing the sum data rate, minimizing the total energy consumption or minimizing the communication delay [2,3].

It is noticed that the most existing works have only considered the scenarios with static users. That is, in their works, the users’ mobility was not taken into account. When GMUs move, the channels between GMUs and the UAV may change quickly over time. In this case, the existing methods cannot capture the channel varying features cause by users’ mobility, which may be inefficient when they are applied to the scenarios with mobile users. To fill the gap, this paper studies the trajectory planning for the UAV-assisted networks with multiple mobile users, where a set of GMUs randomly move and desire to offload data to a UAV. The GMUs access the UAV in a time division multiple access manner to avoid inter-user interference. Due to the random mobility of GMUs, the state space is quite large. We present a DQN-based method to train the agent acted by the UAV. The contributions are summarized as follows:

- We formulate an optimization problem to maximize the uplink throughput by optimizing the UAV’s trajectory, under the constraints of the UAV’s available energy and the QoS requirements of GMUs. To efficiently characterize GMU’s mobility, the Gauss–Markov mobility model (GM) is employed;

- To solve the formulated problem, we propose a DQN-based UAV trajectory optimization method in which the reward function is designed based on the GMU offload gain and the energy consumption penalty, and the -greedy method is employed to balance the exploration and exploitation;

- Simulation results show that the proposed DQN-based method outperforms traditional Q-Learning-based one in terms of convergence and network throughput, and the larger battery capacity the UAV has, the higher uplink throughput that can be achieved. In addition, compared with other specific trajectories, the DQN-based method can increase the total offload data amount of the system by more than about 19%.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of related previous work. Section 3 presents the system model and the optimization objectives of the considered UAV-assisted network. Section 4 presents the deep reinforcement learning nomenclature and theory and applies this theory to the current delivery problem, presenting the DQN-based solution. In Section 5, final simulation results are reported and discussed. Finally, Section 1 concludes the article.

The following Table 1 describes the significance of various abbreviations and acronyms used throughout the thesis. The page on which each one is defined or first used is also given.

Table 1.

Abbreviation table.

2. Related Work

Thus far, different optimization methods have been applied to plan the UAVs’ trajectories. In [4], a UAV trajectory planning algorithm was proposed by employing the block coordinate descent and successive convex optimization techniques to maximize the minimum data rate of all ground users. In [5], graph theory and convex optimization were applied to find the approximate trajectory solution to minimize the UAV’s mission completion time. In [6], a sub-gradient method was applied to optimize the power consumption of a UAV system while ensuring the minimum data rate of IoT. In [7], particle swarm optimization and genetics algorithm were applied to minimize the transmit power required by the UAV subject to the users’ minimum data rate. In [8], graph theory and kernel K-means as well as the convex optimization method were applied to minimize the the sensor nodes’ maximal age of information (AoI) subject to the limited energy capacity.

However, in aforementioned works, only conventional optimization methods were employed and iterative algorithms were designed, which may be with high computational complexity, especially in the large-scale network scenarios or in a fast time-varying environment. Recently, with the remarkable results shown by reinforcement learning in decision-making tasks, scholars have started to employ reinforcement learning to plan the UAV trajectory.

Compared to traditional methods, the reinforcement learning method has many advantages, such as high adaptability to the environment and real-time interaction with environment. Therefore, the deepQ-network (DQN) has attracted increasing attention in UAV’s trajectory planning [9,10,11,12,13]. In [10], a DQN-based method was proposed to minimize the average data buffer length and maximize the residual battery level of the system, by planning the UAV’s trajectory. In [11], the DQN was employed to solve a priority-oriented trajectory planning problem to satisfy the latency tolerance of the network. In [12], a DQN-based method was proposed to maximize the quality of service based on the freshness of data. In [13], a DQN-based scheme was designed to maximize the uplink throughput of the UAV-assisted emergency communication networks.

The following Table 2 summarizes aforementioned existing works by methods used and optimization objectives.

Table 2.

Related work table.

3. System Model

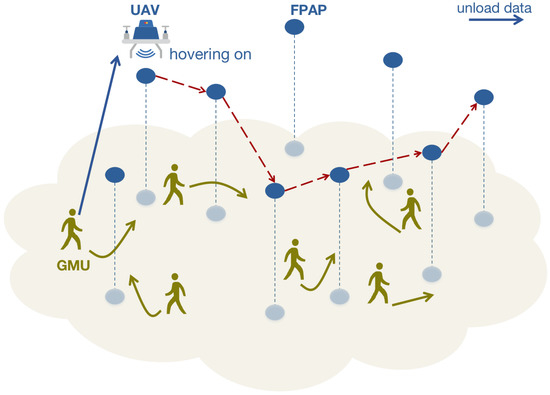

The system model of the considered UAV-assisted network is shown in Figure 1, which consists of an energy-limited UAV, K GMUs and M fixed perceptual access points (FPAPs). The UAV works as an ABS and provides computing services to the GMUs, communicating with the served GMU, computing the data uploaded by GMUs, and also returning calculation results to GMUs. Within the UAV’s coverage, all of the GMUs can be served, but due to the limited processing capacity, it is assumed that the UAV can only serve one GMU at a time. The total available energy of the UAV is denoted by . Let the operational period of the UAV be N seconds. Within N, all energy can be used.

Figure 1.

UAV service model for ground mobile user equipment.

To operate the system, the time is discretized and N is split into T time slots, so the slot with the time duration of

When T is sufficiently large, is very small. Compared to the UAV that can move at high speed, GMUs are moving relatively slowly. Thus, in each , the location of the GMU can be roughly regarded as static, and the UAV is able to fly as well as hover to serve the selected GMU by taking the FPAPs as moving references. We also assume that, in time slot t, the UAV hovers above the m-th FPAP, it is able to receive as well as complete the offloaded task of the k-th GMU, which is associated with the FPAP. The UAV’s location at time slot t is denoted by

where , and H is hovering height of the UAV. The K GMUs are distributed randomly, and the k-th GMU is denoted by . The UAV’s remaining energy at time slot t is .

3.1. User Mobile Model

As mentioned previously, the locations of all GMUs can be roughly regarded as static in each time slot t. Based on the Gauss–Markov mobile model [15], the update for the velocity and the angle of the k-th GMU at the time slot t can be expressed by

where denote the weights of the previous state, and indicates the average velocity of all GMUs. is the average angle of the k-th GMU. and of the k-th GMU characterize the randomness of GMU’s mobility, both obeying independent Gaussian distribution, but having separate numerical characteristics and . The location of the k-th GMU at time slot t is denoted as

Following (3), one has that

3.2. UAV Energy Consumption Model

The energy consumed by the UAV consists of communication energy consumption and propulsion energy consumption. Due to the communication energy consumption being relatively small, we mainly consider propulsion energy consumption of the UAV. According to [16], for a rotary-wing UAV flying with speed V, the propulsion power consumption can be calculated by

where and represent the blade profile power and induced power in hovering status, respectively, is the tip speed of the rotor blade of the UAV, is the mean rotor induced velocity of the UAV in hovering, is the fuselage drag ratio, is the density of air, s is the rotor solidity, and A denotes rotor disc area. All the relevant parameters are explained in details in Table 3. In particular, when UAV is hovering, the speed of UAV is 0, the hover power is . Conversely, when the UAV is flying, the flight power is . In each slot, the UAV will fly to the m-th FPAP and hover over it until the offloaded task of the k-th GMU is completed. Thus, the energy consumption generated of the t-th time slot can be calculated by

where is the flying time and is the hovering time. Suppose at time slot t that the UAV is hovering over the m-th FPAP. The channel power gain of the line of sight (LoS) link between the UAV and the k-th GMU is given by

where denotes the path loss per meter, and H is hovering height of the UAV. Following (8), the uplink data rate from the k-th GMU to the UAV at t is given by

where B is channel bandwidth, is the transmit power of the GMU, and is the Gaussian noise power received by the UAV. The hovering time of the UAV at the t-th time slot can be calculated by

where is the amount of data that can be offloaded by the k-th GMU in the t-th time slot.

Table 3.

Simulation parameter setting.

The remaining energy of the UAV at time slot is given by

3.3. Problem Formulation

The GMU employs a full offload mode. That is, all data of the associated GMU are offloaded to the UAV and then calculated. The binary variable is defined to indicate whether the UAV receives offloading data from the k-th GMU during the t-th time slot. If , the UAV receives offloaded data from the k-th GMU; otherwise, there is no offloaded data from the k-th GMU to the UAV. Because, in each time slot, the UAV is only allowed to serve one GMU, it therefore satisfies that

Thus, the number of data bits offloaded from the k-th GMU to the UAV in t time slots is given by

In order to meet the quality of service (QoS) requirements for GMU k, should satisfy

where the constant is the minimum number of offloading data bits to guarantee the QoS of the GMU.The total number of data bits offloaded by all GMUs to the UAV is given by

The total energy consumption of the UAV must be limited by during T time slots, which is expressed by

Let be the location vector of the UAV, and let denote the GMU schedule indication. In order to maximize the total amount of the data that can be uploaded, under the constraints of the available energy of the UAV and the QoS of GMUs by planning the UAV’s trajectory, we formulate the optimization problem as

4. The DQN-Based Method for UAV Trajectory Planning

4.1. Reinforcement Learning and DQN

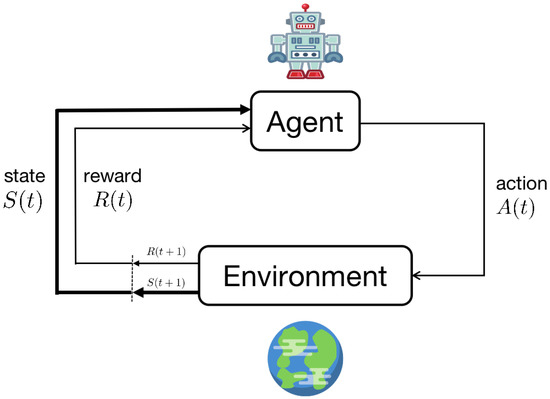

Reinforcement Learning is the science of decision-making. It is about learning the optimal behavior from interactions in order to achieve a goal. The learner and decision maker is called agent, while the things it interacts with is called environment.

Figure 2 illustrates the agent–environment interaction. The interaction occurs at each of t discrete time steps. At each time step, the agent observes the environment, receives a state from the state space S and chooses an action from the action space . Through action , the agent and the environment interact once, which makes the agent obtain a numerical reward from the environment as a result of the previous action. In addition, then the agent comes into a new step .

Figure 2.

The agent–environment interaction in reinforcement learning.

Reinforcement Learning methods achieve a goal usually by choosing a policy that can maximize the total amount of reward, called return :

where is the discount factor. The discount factor determine the impact of future returns. A factor of 0 causes the agent to only consider current rewards, whereas factor approaching 1 causes it to strive for high returns in the long term. The fundamental ideas behind reinforcement learning are well-introduced in surveys of reinforcement learning and optimal control [17].

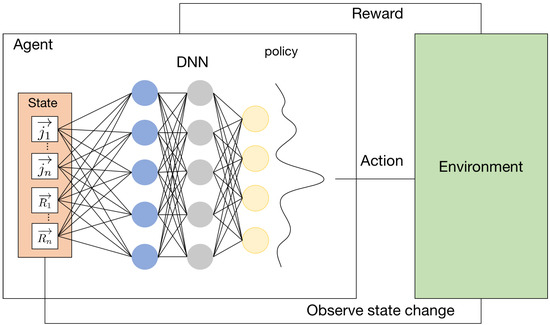

Q-learning is one of the well-known reinforcement learning methods that can be employed with no knowledge of the environment. However, this method cannot be applied to an infinite continuous state space due to the limitation of Q-table. In 2015, DeepMind [18] was successful in combining Q-learning with neural networks and named the method DQN. The structure of DQN is shown in Figure 3. The authors applied a deep neural network to approximate the optimal action-value function, which represents the maximum of the total of rewards, and then to choose the policy.

Figure 3.

DQN structure.

Furthermore, there were two key ideas in the DQN method. The first idea was to match the action-values to target values that were only periodically updated, thereby reducing correlations with the target. The second one applied a mechanism named experience replay in which random batch selection of samples can remove correlation in the observations of states and improve data distribution.

As is known, due to GMUs’ mobility, the channels between GMUs and the UAV may change quickly over time. In this case, the UAV has to select a suitable GMU to serve based on the changing channels. If the traditional Q-Learning method is adopted, it may fail to plan the UAV’s trajectory because of an oversized Q-table or excessive runtime. To accommodate the larger state space, the DQN that employs deep neural networks to estimate the optimal action value function is adopted.

4.2. The DQN-Based Method for UAV Trajectory Planning

In order to improve the convergence rate and training effect, the DQN-based method we proposed applies the iterative updating process and the experience relay (ER) method to reduce the negative effects sequence correlation on the training results. In addition, it also applies the -greedy method to balance the exploration and exploitation, for achieving the better estimations of the environment and also taking better actions. To plan trajectories of the UAV, the agent, action space, state space and reward function in the DQN-based method are defined as follows, where the UAV is regarded as an agent in the DQN, and its chosen strategy can be denoted as .

4.3. Action Space

The UAV chooses a GMU at each time slot and flies to hover over the FPAP associated with that GMU to serve it. The action space contains two kinds of actions, given by

where indicates that the UAV chooses the k-th GMU in the t-th time slot, and indicates that the UAV flies to the m-th FPAP at the t-th time slot. In the DQN-based method, action selection by an agent is accompanied by exploration and exploitation. In this paper, during choosing actions, we employ the -greedy method to find a balance between exploration and exploitation, which introduces a parameter with a small value. The agent chooses the action with the largest value of action value function with probability , and explores the environment with probability . Thus, the agent has an probability of stepping out of the local optimum and finding a global optimum that is closer to the actual one. The method is given by

where is the total number of the agent actions in state s. When the action a maximizes the action value function, the probability of choosing action a is , and the probability of exploring is instead.

4.4. State

4.5. Reward

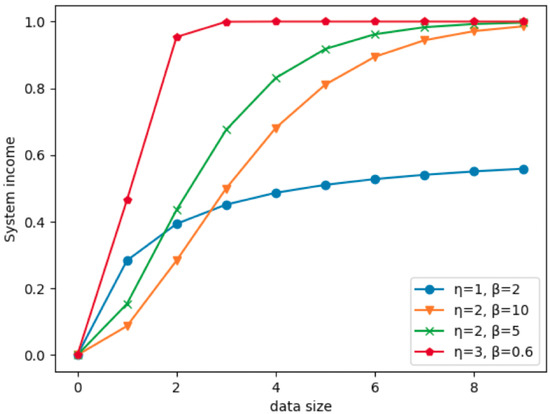

The UAV works as an ABS to communicate with the GMU to fulfill its computational tasks. When the GMU offloads the data, the system needs to provide some reward to encourage the UAV to serve this GMU, referring to [19]. Thus, the relationship between the offloading data and the gain is expressed in terms of sigmoid function, i.e.,

where the constant is the scaling factor of , and and are used to adjust the efficiencies of . The comparison of the is shown in Figure 4. The system gain first increases rapidly as rises and then becomes stable when is large enough. According to Figure 4, in order to improve the training, we choose and as the best parameter pairs. Because, compared with other parameter pairs, it has a smoother curve and better numerical features. In addition, in terms of (12), the UAV is prevented from serving any single GMU for a long time and then ignoring other GMUs, thus ensuring the QoS of GMUs.

Figure 4.

System income versus the data size with different and .

The UAV is rewarded when it receives and processes offloading data transmitted by the GMU. However, at the same time, it also consumes energy due to flying and hovering. The system reward in time slot t can be obtained at the beginning of the next time slot , so we design the system reward as

where is used to normalize and unify the units of and .

This reward function employs energy consumption as the penalty term and as the reward term. It allows the UAV to maximize the amount of data that can be offloaded by GMUs via learning to complete more offloading computational tasks at relatively low energy consumption. The trajectory planning of the UAV is achieved based on the optimal GMU node selected by the reward function.

To correctly enhance system performance, the average gain g per training epoch is applied to demonstrate the average network throughput, which is given by

To improve the QoS of GMUs, the average network reward is maximized. We aim to finding the optimal strategy based on the maximum average reward in each epoch. Thus, we maximize the average long-term network reward and increase the probability that the strategy in learning chooses an action depending on the current state instead.

The state-action value function is given by

where is the discount factor, and is immediate reward based on the state-action pair at the t-th time slot. This value function is employed to evaluate the actions chosen by the UAV according to the state at time slot t. The DQN approximates the Q value by using two DNNs with different parameters, respectively, and . One of the DNNs is a prediction network that takes the current state–action pair as input, and the output is the predicted value . The other is the target network that takes the next state as input, and the output is the maximum Q value of the next state–action pair, so the target value of is given by

where the parameter is candidate action for the next state.

4.6. Algorithm Framework

For clarity, the overall training framework of the proposed DQN-based algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: The DQN-based trajectory planning algorithm. |

| Input: Markov decision process , replay storage M, number of cycles N, explore probability , deep learning networks Q, number of steps to update the target network , and learning rate . Output: The optimal strategy . for to Ndo According to , choose any action in action space with the probability , and choose with probability . Execute action and observe reward from the environment to obtain the next state . Store from the environmental transfer process into replay storage M. Sample from a small batch of individual samples in replay storage M. Calculate the target value in each conversion process . Updates parameters of the Q-network. Execute gradient descent algorithm. Updates to the target network: after steps, updates. end return The optimal strategy ; |

5. Numerical Results and Discussion

We simulate an uplink UAV-assisted wireless network with a 500 m × 500 m region, with 5 GMUs and 25 FPAPs randomly distributed in the region. The simulation parameters are summarized in Table 3.

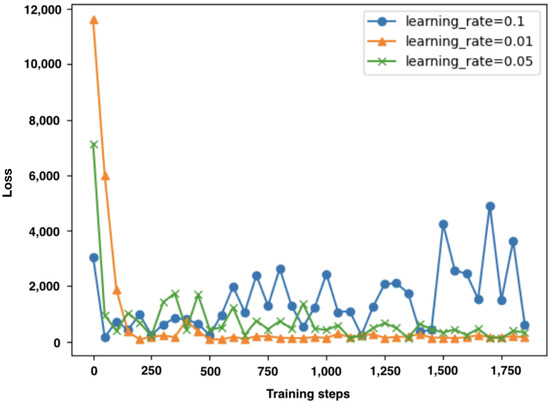

We first simulate loss function with different learning rates as shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that, when the learning rate , the loss function converges to near zero. Moreover, with , it converges with about 100 epochs, and the loss function curve becomes smooth. Thus, we select as the learning rate in the subsequent simulations.

Figure 5.

The loss functions with different learning rates.

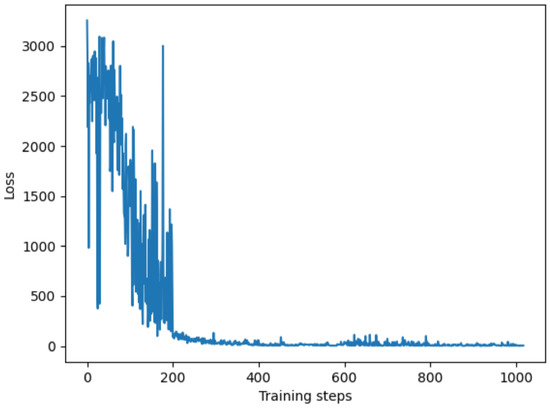

Figure 6 shows the variation of the loss value versus the training steps. It is observed that the loss value decreases with oscillating before 200 epochs and converges to near zero with about 250 epochs. This indicates that the proposed method is able to converge well.

Figure 6.

The loss versus the training steps.

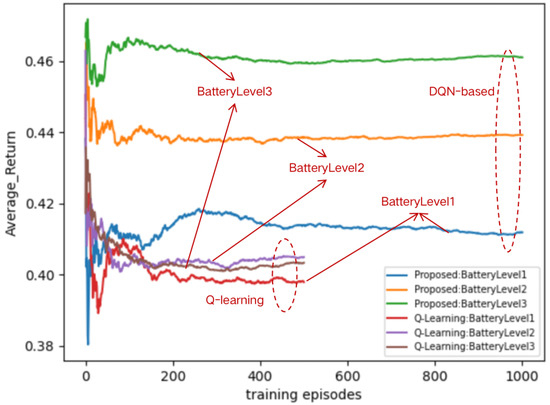

Figure 7 compares the proposed DQN-based method with the traditional Q-learning based one. It shows that the proposed DQN-based method achieves much better performance in terms of average return. Moreover, it is seen that the traditional Q-Learning method stops running when the number of episodes is more than 500 while our proposed method can continue to run after 500 episodes, with a stable average return. This is because the Q-learning method stores a large amount of states and actions in the Q-table, which consumes a lot of memory, and the limited memory capacity terminates its running. In Figure 7, the average returns with different battery levels are also presented. Battery level means the available energy of the UAV, where battery level 1 is 100 KJ, battery level 2 is 200 KJ and battery level 3 is 300 KJ. It is seen that the higher the battery level, the more average return gain that is achieved by our presented DQN-based method, compared to the Q-learning based one.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the proposed DQN based method with a traditional Q-learning method.

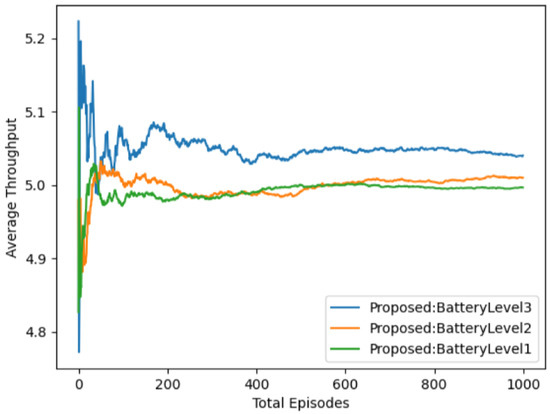

Figure 8 discusses the average throughput achieved by our presented method with different battery levels. Consistent with Figure 7, it is seen that the higher the battery level that UAV has, the longer the UAV runs, the larger number of GMUs that can be served, and the larger the average system throughput that can be achieved. Moreover, with battery level 1 and level 2, the average system converges at about 250 episodes, and, with battery level 3, the average system converges at about 500 episodes.

Figure 8.

Average throughput versus Episodes.

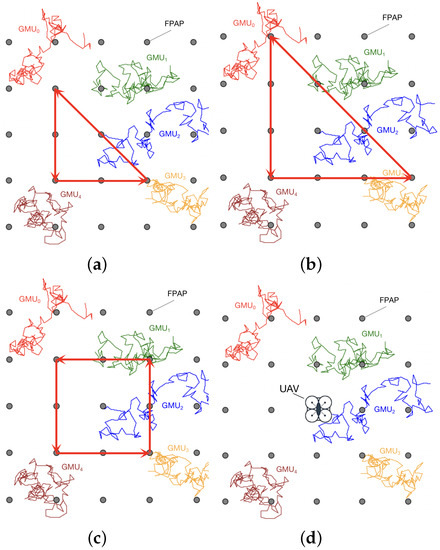

In addition, we demonstrate the performance of the proposed method by comparing it with other UAV trajectories. Figure 9 plots some different UAV trajectories. In the figure, the red, green, blue, brown and orange curves portray the movement trajectories of five GMUs over a period of time, respectively, and 25 grey points denote the locations of 25 FPAPs. Different UAV trajectories are drawn in red straight lines. It is worth noting that, in the final subfigure, the trajectory of the UAV is hovering over the central FPAPs providing services to GMUs until the battery runs out.

Figure 9.

Different UAV trajectories; (a) triangle trajectory 1; (b) triangle trajectory 2; (c) rectangle trajectory; (d) constant hovering.

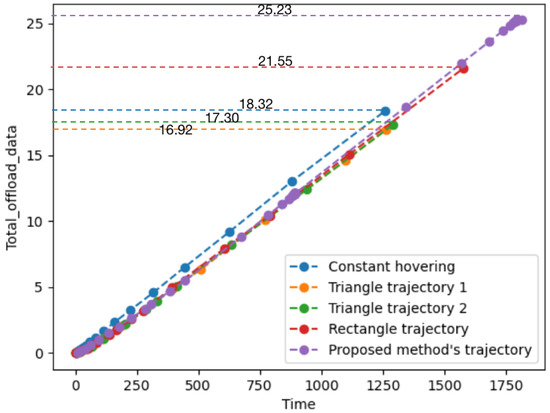

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the performance comparison versus different trajectories. Figure 10 shows the total run time and the total amount of offloaded data of the limited power UAV under different trajectories. We can see that the UAV running on the trajectory planned by the proposed method can not only run longer than other trajectories, but can also obtain a larger amount of offload data.

Figure 10.

Total offload data versus time.

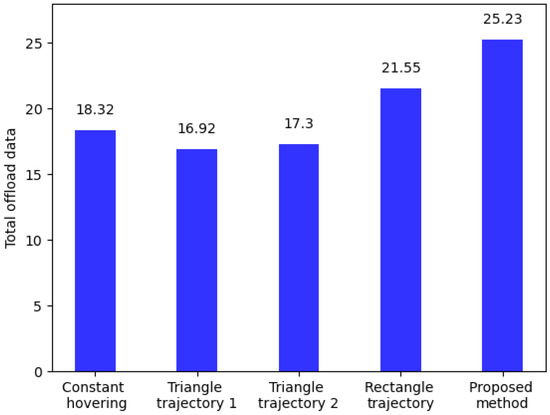

Figure 11.

Total offload data versus different trajectories.

Figure 11 visualizes the total offload data amount of different trajectories, and the proposed method plans the trajectory with a larger offload data amount. Compared with other trajectories, the proposed method can increase the total offload data amount of the system by more than about 19%.

6. Conclusions

This paper studied the trajectory planning in the UAV-assisted mobile networks. Due to the mobility of the GMUs, the state space was quite large, and we proposed a DQN-based method. The simulation results show that the proposed DQN-based method outperforms a traditional Q-Learning-based one in terms of convergence and network throughput, and is able to maximize the system uplink throughput. According to our work, it can help power-limited UAV to make better decisions in real-time varying scenarios to achieve greater system throughput. In future work, further improvements can be made, such as using the hierarchical DQN or the deep deterministic policy gradient to make strategies and also attempt to research trajectory planning of multi-assisted UAV. Moreover, in our work, the flight height of the UAV is fixed, but in some high-low scenarios, it is also an interesting direction to research the 3D trajectory planning of the UAV.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L., G.X. and T.J.; validation, Y.L., X.Z. and K.X.; investigation, Y.L. and X.Z.; resources, K.X., Z.Z. and G.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and K.X.; visualization, Y.L.; funding acquisition, K.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CAAI-Huawei MindSpore Open Fund Grant No. CAAIXSJLJJ-2021-055A, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grant No. 62071033, in part by the National Key R&D Program of China Grant No. 2020YFB1806903, and also in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Grant Nos. 2022JBXT001 and 2022JBGP003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mignardi, S.; Marini, R.; Verdone, R.; Buratti, C. On the Performance of a UAV-Aided Wireless Network Based on NB-IoT. Drones 2021, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xiong, K.; Cao, J.; Lu, Y.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. Average AoI minimization in UAV-assisted data collection with RF wireless power transfer: A deep reinforcement learning scheme. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 5216–5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Ni, Q.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. UAV-assisted wireless powered cooperative mobile edge computing: Joint offloading, CPU control, and trajectory optimization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 2777–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R. Joint trajectory and communication design for multi-UAV enabled wireless networks. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2018, 17, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R. Cellular-enabled UAV communication: A connectivity-constrained trajectory optimization perspective. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2019, 67, 2580–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJubayrin, S.; Al-Wesabi, F.N.; Alsolai, H.; Duhayyim, M.A.; Nour, M.K.; Khan, W.U.; Mahmood, A.; Rabie, K.; Shongwe, T. Energy Efficient Transmission Design for NOMA Backscatter-Aided UAV Networks with Imperfect CSI. Drones 2022, 6, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, B.; Cao, J.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. Joint optimization of trajectory, task offloading and CPU control in UAV-assisted wireless powered fog computing networks. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2022, 6, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Liu, J.; Xie, L. Multi-UAV Aided Data Collection for Age Minimization in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP), Nanjing, China, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M.-C.; Deng, D.-J.; Wu, C.-L. Optimum aerial base station deployment for UAV networks: A reinforcement learning approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Workshops), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, V.; Jalden, J.; Klessig, H. Optimal UAV base station trajectories using flow-level models for reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2019, 5, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Lu, Y.; Ni, Q.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. UAV-aided wireless power transfer and data collection in Rician fading. IEEE J. Select. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 3097–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, B.; Liu, Z.; Guo, L. The UAV Trajectory Optimization for Data Collection from Time-Constrained IoT Devices: A Hierarchical Deep Q-Network Approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Nallanathan, A. Trajectory optimization for UAV emergency communication with limited user equipment energy: A safe-DQN approach. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2021, 5, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y.-I. Deep Reinforcement Learning for UAV Trajectory Design Considering Mobile Ground Users. Sensors 2021, 21, 8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batabyal, S.; Bhaumik, P. Mobility models, traces and impact of mobility on opportunistic routing algorithms: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 1679–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R. Energy Minimization for Wireless Communication With Rotary-Wing UAV. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2019, 18, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiumarsi, B.; Vamvoudakis, K.G.; Modares, H.; Lewis, F.L. Optimal and autonomous control using reinforcement learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 2042–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Hossain, M.J.; Cheng, J. Performance of wireless powered amplify and forward relaying over nakagami-m fading channels with nonlinear energy harvester. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2016, 20, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).