Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed triple-platform framework using UAV-based block kriging significantly improves radiometric validation accuracy, effectively capturing intra-pixel heterogeneity in complex urban environments.

- Quantitative spatial analysis identifies artificial grass as a highly stable “Urban PICS” candidate, whereas asphalt exhibits excessive spectral noise due to surface aging.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The physics-informed upscaling technique provides operational flexibility by mitigating validation errors from temporal mismatches (up to 1 day), establishing UAVs as a robust “spatial bridge.”

- This framework sets a rigorous and scalable standard for validating microsatellite constellations, essential for producing reliable analysis-ready data for smart city monitoring.

Abstract

The exponential rise in microsatellite constellations offers unprecedented temporal resolution for urban monitoring. However, ensuring the radiometric integrity of these sensors over heterogeneous built environments remains a critical challenge due to low signal-to-noise ratios and spectral uncertainties. Traditional vicarious calibration relies on homogeneous pseudo-invariant calibration sites (PICS) in deserts, which fail to represent the spectral complexity and adjacency effects of urban landscapes. This study presents a novel triple-platform validation framework integrating ground (Hyperspectral), UAV (Multispectral), and satellite (Sentinel-2) data to bridge the “Point-to-Pixel” scale gap. We introduce a physics-informed “Double Calibration” protocol—combining the empirical line method with spectral response function convolution—and a block kriging spatial upscaling technique to mathematically model intra-pixel heterogeneity. Results from a 2025 campaign in a complex urban environment (Cheongju, Republic of Korea) demonstrate that simple point-averaging introduces significant representation errors ( with time lag). In contrast, our UAV-based block kriging approach recovered high correlations even with a 1-day time lag and dramatically improved the coefficient of determination (R2) under simultaneous acquisition conditions: from 0.68 to 0.92 in the blue band and to 0.96 in the NIR band. Furthermore, quantitative spatial analysis identified artificial grass as the most stable “Urban PICS” (), whereas asphalt exhibited unexpected high spatial heterogeneity () due to surface aging and challenging conventional assumptions. This framework establishes a rigorous, scalable standard for validating “New Space” data products in complex urban domains.

1. Introduction

The paradigm shift towards “New Space” has fundamentally democratized Earth observation, transitioning the field from relying on a few large, government-funded satellites to agile constellations of microsatellites. This explosion in orbital sensors provides the high-frequency revisit times—often daily or sub-daily—that are essential for operational smart city monitoring, disaster response, and rapid environmental assessment [1,2]. However, the utility of this data is frequently compromised by the physical limitations of the platforms themselves. Unlike flagship missions such as Landsat-9 or Sentinel-2, which carry large, strictly calibrated instruments, microsatellites often suffer from radiometric inconsistencies due to severe size, weight, and power constraints [3,4]. These hardware limitations result in lower signal-to-noise ratios and spectral instability, making the direct usage of raw data risky for scientific analysis. Consequently, establishing rigorous post-launch calibration and validation protocols is not merely a technical formality but a mandatory step to ensure these data products meet analysis-ready data standards [5]. While cross-calibration techniques are well-established for large, stable satellites [6], applying them to microsatellite constellations is complicated by distinct spectral bandwidth differences and orbital variability [7].

Historically, the remote sensing community has relied on pseudo-invariant calibration sites (PICS) located in vast, homogeneous deserts to monitor sensor degradation [8]. These sites offer spectral stability and minimal atmospheric interference. However, desert PICS fail to represent the spectral characteristics of urban environments, where the landscape is a complex mosaic of diverse materials [9]. This disconnect creates a critical validation challenge known as the “Scale Gap.” Attempting to validate a 10 m satellite pixel (100 m2) using a ground spectroradiometer with a footprint of less than 1 cm2 introduces significant representation errors [10,11]. In a heterogeneous urban scene, a single ground point measurement cannot account for the spectral mixing of asphalt, concrete, vegetation, and varying shadow depths that exist within the satellite’s instantaneous field of view [12]. Furthermore, simple arithmetic aggregation neglects adjacency effects—physical phenomena where photons from bright surfaces scatter into adjacent dark pixels—which are prevalent in built environments [13]. This representation error is widely recognized as the dominant source of uncertainty in urban remote sensing, necessitating the development of advanced scaling methods that go beyond simple linear averaging.

To address this spatial disconnect, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as a potential “spatial bridge” capable of linking discrete ground points with broad satellite pixels [14,15]. Operating at low altitudes, UAVs can capture intra-pixel heterogeneity at centimeter-level resolution, revealing the fine-scale texture of the urban surface [16]. Despite this potential, current validation methodologies often underutilize UAVs, treating them merely as high-resolution cameras rather than scientific radiometers. Researchers frequently apply simple linear averaging to upscale UAV data to satellite resolution [17], a method that is mathematically flawed for complex surfaces as it ignores spatial covariance and the adjacency effects [18]. Recent reviews emphasize that for UAVs to serve as reliable validation tools, they must be operated under rigorous radiometric protocols comparable to those used for satellite sensors [19,20].

Moreover, the remote sensing field is increasingly moving towards physics-informed deep learning to handle tasks such as spectral super-resolution and multi-source data fusion [21,22]. While deep learning offers immense promise for cross-calibration and data enhancement [23], these “black box” models rely heavily on high-quality, physically consistent training data that accurately represents surface heterogeneity [24]. As the requirement for such data becomes paramount, data containing representation errors due to improper upscaling can fundamentally flaw these artificial intelligence (AI) models. Therefore, establishing a robust, physics-based physical validation framework is a critical prerequisite for training the next generation of AI models for Earth observation [25].

This study proposes a comprehensive, physics-informed multi-scale validation framework specifically designed to overcome the challenges of urban environments. First, we aim to operationalize the concept of “Urban PICS” by statistically identifying stable urban surfaces—such as artificial grass—that can replace traditional desert sites for operational calibration in built environments. Second, to rigorously bridge the scale gap, we apply block kriging rather than simple averaging to upscale UAV data. This geostatistical approach mathematically models intra-pixel heterogeneity, preserving the spatial variance that is often lost in linear aggregation. Finally, we implement a “Double Calibration” protocol that integrates spectral response function (SRF) convolution and linear radiometric correction. This step transforms commercial UAV sensors into precision transfer radiometers, ensuring that the bridge between ground truth and satellite observations is physically consistent and traceable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Experimental Design

The research was conducted at the Chungbuk National University campus in Cheongju, Republic of Korea (36°37′ N, 127°27′ E). This site acts as a “Digital Twin” of a complex city [26], characterized by an intricate mixture of artificial structures and diverse natural vegetation. Such spatial complexity makes it an optimal testbed for evaluating the impact of spatial heterogeneity on satellite radiometric validation.

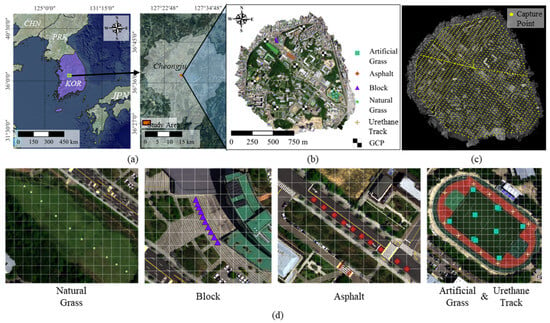

To comprehensively evaluate the framework, five distinct surface targets were selected to represent a gradient of spatial homogeneity: asphalt (Roads), urethane tracks (Sports facilities), artificial grass (Urban PICS candidate), natural grass (Dynamic target), and permeable concrete blocks (Sidewalks). These targets were chosen to represent a broad range of spatial complexity, allowing for the rigorous testing of spectral unmixing and scaling effects [27]. The experimental design, detailed in Figure 1, employs a multi-scale spatial hierarchy to ensure the representativeness of each platform. By nesting high-resolution UAV flight parameters and discrete ground measurement points within the satellite’s fixed grid, the framework facilitates precise pixel-to-pixel alignment and accounts for intra-pixel variance across the heterogeneous urban landscape.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area and multi-scale experimental layout. (a) Regional and local geographic context. (b) High-resolution orthomosaic showing the mosaic of urban surface materials. (c) Operational UAV flight plan including automated single-grid paths and image trigger points. (d) Spatial registration scheme overlaying the 10 m Sentinel-2 pixel grid with synchronized in situ hyperspectral sampling locations.

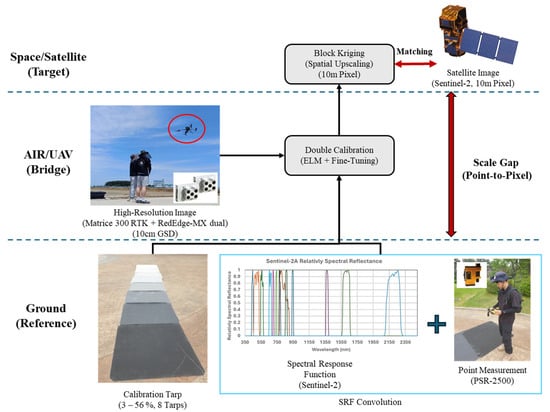

2.2. The Triple-Platform Data Acquisition

Data collection was executed through two distinct campaigns on 23 June 2025, and 10 July 2025. This dual-campaign approach allowed for the assessment of both temporal mismatch effects (23 June, one-day lag) and synchronized radiometric baselines (10 July, fully concurrent). As illustrated in the schematic of Figure 2, the triple-platform validation framework integrates three distinct tiers—ground (Reference), UAV (Spatial Bridge), and satellite (Target)—to bridge the point-to-pixel scale gap through a systematic workflow including spectral matching, radiometric correction, and geostatistical upscaling.

Figure 2.

The triple-platform validation framework. This schematic illustrates the data acquisition and processing workflow integrating three tiers: ground (Reference), UAV (Spatial Bridge), and satellite (Target). Key processing steps include spectral response function (SRF) convolution to ensure physical comparability, “Double Calibration” of UAV imagery, and spatial upscaling via block kriging to bridge the point-to-pixel scale gap.

Ground-based reference data were acquired using a PSR-2500 Spectroradiometer (Spectral Evolution, Haverhill, MA, USA), covering 350–2500 nm with 1 nm resolution. This instrument served as the absolute radiometric standard traceable to physical units [28]. Measurements were taken at 10 randomly selected points per target class, with a calibrated 99% white reference panel utilized immediately prior to each measurement to ensure absolute radiometric traceability.

For the UAV-based “spatial bridge”, a Matrice 300 RTK (DJI, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a RedEdge-MX Dual camera (MicaSense, Seattle, WA, USA) was deployed. The flights were conducted at an altitude of 150 m AGL, yielding a ground sampling distance of approximately 10 cm. This ultra-high spatial resolution was essential for capturing the spatial variance required for upscaling [29]. To ensure internal geometric rigidity and minimize bidirectional reflectance distribution function effects, the UAV was operated with a 75% front-overlap and 75% side-overlap configuration. Satellite target data consisted of Sentinel-2 Level-2A products, which serve as the reference standard due to their well-documented radiometric performance [30]. These data were atmospherically corrected using the Sen2Cor algorithm to generate Bottom-of-Atmosphere (BOA) reflectance. The validation analysis focused on the 10 m (Blue, Green, Red, NIR) and 20 m (Red Edge) bands.

2.3. Physics-Based Preprocessing: SRF Convolution

To resolve the spectral mismatch between narrow-band sensors and broad-band satellite sensors, we calculated the weighted average of the ground hyperspectral data according to the SRF of Sentinel-2 [31,32]. This step is critical because direct comparison of band-center reflectance leads to significant errors in broad-band sensors [33,34]. The simulated satellite reflectance () was calculated using Equation (1):

where represents the ground-measured hyperspectral reflectance and is the relative spectral response of the Sentinel-2 sensor. This integration ensures that the ground truth physically replicates the integrated energy response of the satellite sensor. Table 1 details the spectral matching parameters.

Table 1.

Comparison of spectral band characteristics (Center wavelength and bandwidth) between the Sentinel-2 (Satellite) and RedEdge-MX Dual (UAV) sensors used for spectral matching.

2.4. The “Double Calibration” Protocol

The “Double Calibration” protocol integrates two sequential stages to transform the UAV into a precision radiometer. Commercial UAV sensors, despite their high spatial resolution, often suffer from inherent radiometric instabilities [35]. First, the Empirical Line Method (ELM) was applied using eight standardized calibration tarps (3% to 56% reflectance) to linearize the sensor’s response across the full dynamic range of the urban scene [36] (R2 > 0.99). Second, a spectral fine-tuning process was implemented by comparing the ELM-corrected UAV reflectance with the SRF-convolved ground reflectance. This secondary bias correction removes residual systematic offsets and ensures optimal alignment between the airborne bridge and the satellite target, adhering to established best practices for high-fidelity remote sensing [37,38].

2.5. Geostatistical Spatial Upscaling: Block Kriging

To rigorously address the “support effect,” this study applied block kriging to upscale UAV data to the satellite’s resolution [39]. Unlike simple averaging, block kriging explicitly models the spatial covariance of the UAV sub-pixels [40,41].

A Spherical variogram model was fitted to the high-resolution UAV data to capture the unique spatial autocorrelation structure and texture of each urban surface type. The estimation block size was strictly set to 10 m × 10 m, perfectly aligned with the Sentinel-2 pixel grid to minimize geometric registration errors. In this implementation, the nugget effect was fixed to zero, justified by the ultra-high sampling density (10 cm GSD), which is sufficient to capture the intra-pixel spatial structure without significant sub-sample variance, and the effectiveness of the “Double Calibration” protocol in minimizing sensor-induced random noise. This configuration ensures that the upscaled reflectance maintains the spatial continuity of the surface while providing a physically consistent integration of the sub-pixel variance.

2.6. Uncertainty Quantification and Statistical Analysis

To provide an objective assessment of the suitability of each surface as an “Urban PICS” candidate, a rigorous spatial homogeneity analysis was conducted. A total of N = 10,000 random pixels were extracted per target class from the UAV imagery to ensure statistical significance. For each surface type, the standard deviation (σ) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to quantify intra-pixel heterogeneity and assess temporal stability across the two campaigns. Furthermore, validation performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE), allowing for a direct numerical comparison between the proposed block kriging framework and traditional point-averaging methods.

3. Results

3.1. Verification of UAV Radiometry

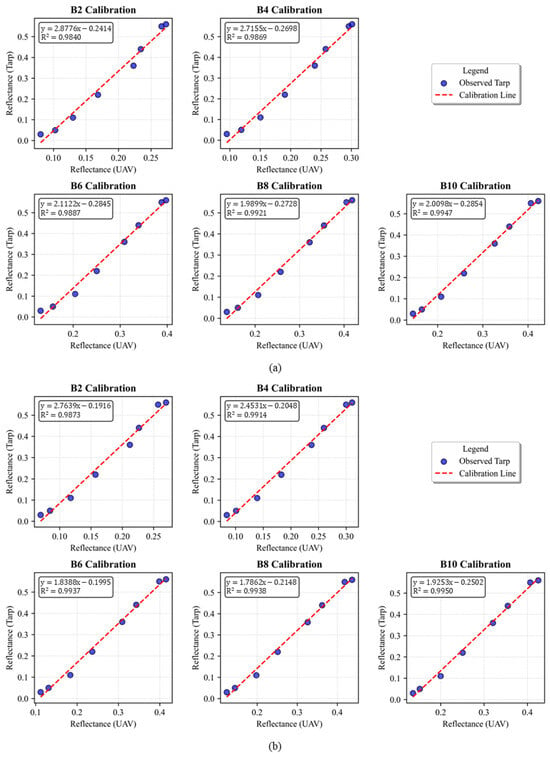

To ensure the UAV sensor functions as a scientific transfer radiometer, its response was strictly linearized using the “Double Calibration” protocol. As illustrated in Figure 3, the relationship between the UAV’s raw digital numbers and the reflectance of the eight standardized calibration tarps exhibited excellent linearity (R2 > 0.99) for both campaign dates across all spectral bands.

Figure 3.

Linearity between UAV raw digital numbers and eight calibration tarps for (a) 23 June and (b) 10 July. The results show high radiometric stability (R2 > 0.99) after applying the first stage of the Double Calibration protocol.

The statistical performance of the protocol was further quantified by comparing the UAV-derived reflectance with the standardized tarps. Table 2 summarizes the regression parameters and accuracy metrics for each band. The results demonstrate that the first stage (ELM) achieved near-perfect linearity and effectively minimized sensor bias. The secondary spectral fine-tuning step significantly minimized residuals, reducing the RMSE in the Blue band from 0.052 to 0.015.

Table 2.

Statistical performance of the UAV “Double Calibration” protocol, summarizing linearity (Slope, Intercept, R2) and error metrics (RMSE) for each spectral band.

3.2. Identification of “Urban PICS”

A novel contribution of this study is the quantitative re-evaluation of urban surfaces as potential pseudo-invariant calibration sites (PICS) based on both statistical homogeneity and spatial autocorrelation structure.

To ensure statistical robustness, we conducted a rigorous spatial homogeneity analysis using a sample size of N = 10,000 random pixels per surface class extracted from the 10 cm resolution UAV imagery. σ and 95% CI were calculated to evaluate the suitability of each candidate (Table 3). The analysis reveals that artificial grass emerged as the superior “Urban PICS” candidate. It maintained a consistently low standard deviation () with a tight 95% confidence interval (), demonstrating exceptional spatial homogeneity and temporal stability across both campaigns. In contrast, asphalt exhibited significant spatial heterogeneity (). This variability exceeded that of artificial grass by over 350%, confirming that surface aging effects, such as micro-cracking and aggregate exposure, introduce unpredictable spectral noise at the decimeter scale, rendering asphalt unsuitable for single-pixel validation.

Table 3.

Quantitative evaluation of spatial homogeneity for urban surfaces based on standard deviation () derived from 10 cm resolution UAV imagery.

Furthermore, the spatial autocorrelation structure of these urban surfaces was verified by fitting spherical variogram models to the high-resolution UAV data. The optimized range and sill parameters, summarized in Table 4, characterize the intra-pixel heterogeneity required for the geostatistical upscaling. By fixing the nugget effect to zero, the model effectively preserves the high-fidelity signal captured through the double calibration protocol, ensuring that the spatial variance is accurately integrated into the satellite-scale blocks.

Table 4.

Variogram parameters for the spherical model applied to each spectral band.

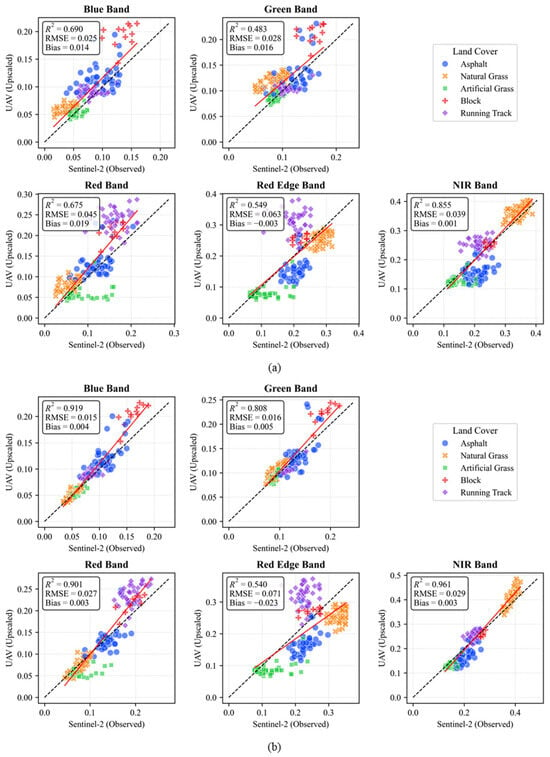

3.3. Validation Accuracy Assessment

The accuracy of the triple-platform framework was quantitatively evaluated by comparing Sentinel-2 satellite imagery with ground/UAV-based observation values. In particular, we compared and analyzed the results of the June campaign, where a 1-day lag occurred between satellite (6/22) and UAV (6/23) acquisition, and the July campaign, where all data was acquired on the same day (7/10), to verify the importance of temporal synchronization and the utility of the upscaling technique (Table 5 and Table 6). The analysis results showed that in the June campaign, the accuracy of the ‘Raw Ground Points’ method was very low () due to changes in atmospheric and illumination conditions caused by the time lag. Specifically, the red edge band showed the lowest correlation with an R2 of 0.35. However, when block kriging was applied, despite the presence of the time lag, R2 improved significantly to the level of 0.55 (Red Edge)–0.85 (NIR), demonstrating that the UAV’s spatial correction can partially offset errors caused by the time lag (Figure 4). In the July campaign, where data was acquired on the same day, the performance of block kriging was maximized. R2 exceeded 0.90 in most bands, and in particular, the NIR band showed the highest agreement with R2 = 0.96. While the red edge band showed a slightly lower raw correlation (R2 = 0.40), the application of block kriging recovered this to 0.54, reducing the RMSE from 0.096 to 0.071. This suggests that while block kriging improves data consistency, certain bands like red edge band may remain sensitive to spectral mixing or bidirectional reflectance distribution function effects in complex urban scenes.

Table 5.

Comparison of validation metrics (R2, RMSE) between traditional raw ground point methods and the proposed block kriging framework across different campaign dates.

Table 6.

Consolidated validation performance of block kriging across campaign dates and spectral bands.

Figure 4.

Accuracy validation of upscaled UAV reflectance against Sentinel-2 imagery. Scatter plots compare the correlation for (a) the 23 June dataset, which includes a 1-day time lag, and (b) the 10 July dataset, acquired simultaneously. The application of block kriging (colored points) significantly improves correlation (R2) and reduces RMSE compared to raw point-based validation, particularly in the near-infrared (NIR) band.

Analysis of the 23 June campaign (1-day lag) revealed that traditional point averaging resulted in low correlations () due to changes in atmospheric and illumination conditions. However, block kriging acted as a robust spatial buffer, effectively mitigating these errors by modeling intra-pixel covariance. In the NIR band, block kriging recovered the correlation from 0.46 to 0.85 and reduced the RMSE by 51%. This confirms that rigorous spatial integration can partially compensate for the lack of strict temporal synchronization. Under simultaneous acquisition (10 July), the framework achieved its maximum potential, with the NIR band reaching and the Blue band reaching . Figure 4 visually confirms the tight alignment along the 1:1 line for the block kriging data, establishing it as a necessary protocol for validating high-resolution microsatellite data in heterogeneous built environments.

4. Discussion

4.1. UAVs as Time-Lag Mitigators and Spatial Integrators

This study fundamentally reassesses the sources of error in urban radiometric validation, demonstrating that the primary challenge is not merely the scale difference, but the compounding effect of spatial representation errors and temporal mismatches. Traditional validation methods, which rely on point-based ground measurements, fail to account for the “spectral cocktail” inherent in a 10 m urban pixel. Our results quantitatively confirm that this limitation is severe: even a one-day time lag between ground and satellite acquisition causes the R2 to drop sharply below 0.5 when using simple point averaging.

However, the application of UAV-based block kriging offers a robust solution. By mathematically modeling the spatial covariance of the surface, this technique effectively integrates the heterogeneous contributions of shadows, interstitial gaps, and texture to match the satellite sensor’s integrated energy response. As requested during the peer review, we quantified this mitigation: the block kriging approach reduced the RMSE in the NIR band by approximately 51% (from 0.080 to 0.039) under 1-day lag conditions. This process creates a “buffer effect” that stabilizes validation metrics, recovering high correlations even when strict temporal synchronization is impossible.

Furthermore, a critical issue often overlooked in multi-platform validation is the spatial alignment of pixels. While relative correction between different satellite platforms (e.g., Sentinel-2 and PRISMA) is a major challenge, the distinct scale ratio of 100:1 between our UAV data (10 cm) and Sentinel-2 (10 m) significantly mitigates this problem. Because block kriging integrates sub-pixel variance over the entire 10 m footprint, minor geometric registration errors that would be fatal in 1:1 satellite comparisons effectively fade, enhancing the overall reproducibility and robustness of the validation framework.

4.2. Operational Efficiency and Processing Costs

A critical consideration for operationalizing this framework is the trade-off between metrological rigor and computational cost. To address concerns regarding time-effectiveness, we evaluated the processing requirements for our 1.54 km2 study area. The initial photogrammetric stage, including UAV image matching and orthomosaic generation, required approximately 6 h of processing time. However, the core radiometric processing—comprising the physics-informed “Double Calibration” protocol and the block kriging upscaling—was completed in only 20 min.

This breakdown demonstrates that while the geometric reconstruction of the urban scene is time-intensive, the specific validation and analysis workflow is highly efficient. Once the initial orthomosaic is generated, the transition from raw UAV data to satellite-comparable reflectance products is rapid, making the proposed framework operationally viable for generating high-frequency analysis-ready data in smart city environments.

4.3. The Necessity of Physics-Informed Approaches

The successful implementation of SRF convolution and the “Double Calibration” protocol highlights that reliance on simple statistical correlation is inadequate for traceable metrology. Commercial UAV sensors often exhibit non-linear biases that cannot be corrected through simple regression alone. To achieve the stringent < 5% uncertainty targets required for modern constellation validation, it is mandatory to physically model both the sensor’s specific spectral response [31] and the surface’s spatial structure [14]. Our framework ensures physical consistency by convolving high-resolution ground spectra with satellite band passes before upscaling, thereby removing spectral mismatches. This rigorous, physics-informed approach enables the clear differentiation of spectrally similar surface types [42,43], establishing a validation standard that supports the training of highly accurate, physics-aware AI models for future remote sensing applications.

4.4. Re-Evaluation of Urban PICS: Asphalt vs. Artificial Grass

A critical finding of this study is the quantitative re-evaluation of potential “Urban PICS”. While asphalt has traditionally been viewed as a stable calibration target in urban remote sensing [44], our ultra-high-resolution analysis with a robust sample size of N = 10,000 pixels reveals significant limitations. Asphalt exhibited high spatial heterogeneity () driven by surface aging effects, such as micro-cracking and exposed aggregates, which introduce unpredictable spectral noise at the pixel scale. In stark contrast, artificial grass demonstrated superior stability, maintaining a consistently low standard deviation () across both temporal campaigns. This identifies artificial grass as an optimal Urban PICS candidate, offering both the spatial homogeneity of a desert site and the temporal durability required for frequent monitoring.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the strong physical foundation of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the current validation relies on a limited temporal sampling, specifically two acquisition dates during the summer season. Extending this framework to cover different seasons and climates is necessary to fully characterize the seasonal stability of Urban PICS and the potential impact of varying solar geometry.

Second, while the framework is designed with a sensor-agnostic logic, its direct application to satellite sensors with significantly different point spread functions or lower signal-to-noise ratios may require specific adjustments to the convolution kernel or geostatistical weights. Finally, future research will aim to extend this work by automating the full processing workflow and incorporating hyperspectral UAV sensors to further minimize spectral mismatch errors, ultimately facilitating the creation of high-quality, AI-ready datasets for smart city monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully established and demonstrated a robust, physics-informed UAV upscaling framework designed to bridge the persistent “Scale Gap” between ground observations and satellite measurements in complex urban environments. By integrating SRF convolution, a rigorous “Double Calibration” protocol, and geostatistical block kriging into a unified workflow, we achieved a high-precision radiometric validation of Sentinel-2 imagery using 10 cm ultra-high-resolution UAV data.

The specific findings under the tested conditions in Cheongju, Republic of Korea, are summarized as follows:

- Methodological Superiority: Block kriging significantly outperformed traditional point-averaging methods, achieving an R2 of 0.96 in the NIR band and reducing RMSE by over 60% under synchronized conditions. This proves that modeling intra-pixel spatial structure is a necessity for accurate upscaling in built environments.

- Urban PICS Identification: Artificial grass () was identified as a superior radiometric target compared to asphalt (), which suffers from unpredictable spectral noise due to surface aging and heterogeneity.

- Temporal Resilience: The framework acts as a spatial buffer, quantifiably mitigating errors caused by temporal mismatches (e.g., recovering R2 from 0.46 to 0.85 with a 1-day lag), thereby operationalizing validation for cases where strict temporal synchronization is unfeasible.

In summary, the framework provides a scalable and objectively verified standard for ensuring the radiometric integrity of “New Space” data products. This facilitates reliable and consistent environmental monitoring and the generation of high-quality analysis-ready data in heterogeneous urban landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-H.L., J.-H.P. and S.-H.G.; methodology, S.-H.G.; software, S.-H.G. and W.-K.J.; validation D.-H.L., J.-H.P., S.-H.G. and W.-K.J.; formal analysis, S.-H.G.; investigation, S.-H.G. and W.-K.J.; resources, S.-H.G. and J.-H.P.; data curation, S.-H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.G.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.P.; visualization, S.-H.G.; supervision, J.-H.P.; project administration, J.-H.P.; funding acquisition, J.-H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-014-03); and by the Korean government (KASA, Korea AeroSpace Administration) (grant number RS-2020-NR055937).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions of the university campus testbed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belward, A.S.; Skøien, J.O. Who launched what, when and why; trends in global land-cover observation capacity from civilian earth observation satellites. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 103, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuccio, S.; Ullo, S.; Carminati, M.; Kanoun, O. Smaller Satellites, Larger Constellations: Trends and Design Issues for Earth Observation Systems. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2019, 34, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapla-Myers, J.; McCorkel, J.; Anderson, N.; Thome, K.; Biggar, S.; Helder, D.; Aaron, D.; Leigh, L.; Mishra, N. The Ground-Based Absolute Radiometric Calibration of Landsat 8 OLI. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 600–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-H.; Johansen, K.; Aragon, B.; El Hajj, M.M.; McCabe, M.F. The radiometric accuracy of the 8-band multi-spectral surface reflectance from the planet SuperDove constellation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 114, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, J.; Aksoy, M.; Apudo, L.; Vukolov, V.; Ashley, H.; VanAllen, D. ACCURACy: A Novel Calibration Framework for CubeSat Radiometer Constellations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, G.; Hewison, T.J.; Fox, N.; Wu, X.; Xiong, X.; Blackwell, W.J. Overview of Intercalibration of Satellite Instruments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 1056–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, M.T.; Gunar, F.; Kurtis, J.T. Spectral band difference effects on radiometric cross-calibration between multiple satellite sensors in the Landsat solar-reflective spectral domain. In Proceedings of the Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites VIII, Maspalomas, Canary Islands, Spain, 13–16 September 2004; pp. 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Chen, L.; Xu, N.; Tao, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Lu, N. Preliminary Selection and Characterization of Pseudo-Invariant Calibration Sites in Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C. A global analysis of urban reflectance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 26, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z.L. Scale issues in remote sensing: A review on analysis, processing and modeling. Sensors 2009, 9, 1768–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Ge, Y.; Jin, R.; Ma, M.; Liu, Q.; Wen, J.; Liu, S. Validation of Regional-Scale Remote Sensing Products in China: From Site to Network. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotthaus, S.; Smith, T.E.L.; Wooster, M.J.; Grimmond, C.S.B. Derivation of an urban materials spectral library through emittance and reflectance spectroscopy. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 94, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirlewagen, D.; von Wilpert, K. Upscaling of environmental information: Support of land-use management decisions by spatio-temporal regionalization approaches. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 878–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.K.; Chiang, T.H.A.; Happonen, A.; Chang, M.M.L. From Satellite to UAV-Based Remote Sensing: A Review on Precision Agriculture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127057–127076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Remote Sensing Applications—A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Mora, J.; Kalacska, M.; Inamdar, D.; Soffer, R.; Lucanus, O.; Gorman, J.; Naprstek, T.; Schaaf, E.; Ifimov, G.; Elmer, K.; et al. Implementation of a UAV–Hyperspectral Pushbroom Imager for Ecological Monitoring. Drones 2019, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, K.; Frazier, A.E.; Singh, K.K.; Madden, M. A review of methods for scaling remotely sensed data for spatial pattern analysis. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ren, H.; Ye, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, Y. Geometry and adjacency effects in urban land surface temperature retrieval from high-spatial-resolution thermal infrared images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 262, 112518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Corpetti, T.; Houet, T. UAV & satellite synergies for optical remote sensing applications: A literature review. Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Anderson, J. Review on unmanned aerial vehicles, remote sensors, imagery processing, and their applications in agriculture. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Du, Q. Spatial and Spectral Joint Super-Resolution Using Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 4590–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, W.; Tang, H.; Lu, B.; Yang, L.; Qian, Y. A Novel Interband Calibration Method for the FY3D MERSI-II Sensor Based on a Combination of Physical Mechanisms and a DNN Regression Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4203616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.-S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep Learning in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review and List of Resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helder, D.L.; Basnet, B.; Morstad, D.L. Optimized identification of worldwide radiometric pseudo-invariant calibration sites. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 36, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, L. Incorporating spatial information in spectral unmixing: A review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 149, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, K.J. Absolute radiometric calibration of Landsat 7 ETM+ using the reflectance-based method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Yi, H.; Fu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Jing, Z. Prediction of canopy mean traits in herbaceous plants by the UAV multispectral data: The quest for a better leaf-to-canopy upscaling method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 141, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, F.; Bouzinac, C.; Thépaut, O.; Jung, M.; Francesconi, B.; Louis, J.; Lonjou, V.; Lafrance, B.; Massera, S.; Gaudel-Vacaresse, A.; et al. Copernicus Sentinel-2A Calibration and Products Validation Status. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishchenko, A.P.; Cihlar, J.; Li, Z. Effects of spectral response function on surface reflectance and NDVI measured with moderate resolution satellite sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.-C.; Montes, M.J.; Davis, C.O.; Goetz, A.F.H. Atmospheric correction algorithms for hyperspectral remote sensing data of land and ocean. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teillet, P.M.; Fedosejevs, G.; Thome, K.J.; Barker, J.L. Impacts of spectral band difference effects on radiometric cross-calibration between satellite sensors in the solar-reflective spectral domain. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 110, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teillet, P.M.; Barker, J.L.; Markham, B.L.; Irish, R.R.; Fedosejevs, G.; Storey, J.C. Radiometric cross-calibration of the Landsat-7 ETM+ and Landsat-5 TM sensors based on tandem data sets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzonio, R.; Di Mauro, B.; Colombo, R.; Cogliati, S. Surface Reflectance and Sun-Induced Fluorescence Spectroscopy Measurements Using a Small Hyperspectral UAS. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.M.; Milton, E.J. The use of the empirical line method to calibrate remotely sensed data to reflectance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 20, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, C.; Jóźków, G. Remote sensing platforms and sensors: A survey. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, B.L.; Helder, D.L. Forty-year calibrated record of earth-reflected radiance from Landsat: A review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, F. Remote-sensing image analysis and geostatistics. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 5644–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Webster, R. A tutorial guide to geostatistics: Computing and modelling variograms and kriging. CATENA 2014, 113, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Jin, R.; Li, X. Regression Kriging-Based Upscaling of Soil Moisture Measurements From a Wireless Sensor Network and Multiresource Remote Sensing Information Over Heterogeneous Cropland. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q. Remote sensing of impervious surfaces in the urban areas: Requirements, methods, and trends. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Wu, C. A spatially adaptive spectral mixture analysis for mapping subpixel urban impervious surface distribution. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 133, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessner, S.; Segl, K.; Heiden, U.; Kaufmann, H. Automated differentiation of urban surfaces based on airborne hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.