Highlights

What are the main findings?

- First empirical assessment of depth-perception improvement from an official RPAS training program.

- Demonstrates measurable perceptual-skill gains despite no explicit syllabus objective for depth perception.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Conducted in authentic operational settings under regulated conditions, ensuring strong external validity.

- Establishes a validated baseline for future comparative and longitudinal studies on perceptual training effectiveness.

Abstract

Flying remotely requires accurate perception of the environment to ensure safe operation. While remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) bring unique opportunities, they also present new challenges for the pilot, including exercising accurate depth perception. The impact of a structured training program on the improvement of depth perception skills of ab initio RPA pilots was measured. Importantly, it should be noted that such training programs are not specifically designed or intended to improve depth perception skills. Students were pre-tested prior to undergoing a training program by flying a drone away from themselves. They were required to stop and hover when they estimated the drone was over markers at three distances of 20 m, 40 m, and 60 m. After completing the 2 days of flight training, they were re-tested with the same exercise. While there was no significant improvement in distance estimation at the 20 m marker, there was significant improvement at the 40 and 60 m markers. These findings indicate that a standard, syllabus-constrained ab initio training course yields measurable gains in egocentric distance estimation beyond the action space, supporting the sufficiency of current training to transfer non-technical perceptual skills to longer VLOS ranges.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Accident Cases

In March 2000, a helicopter conducting a charter flight in the Fiordland region of the South Island of New Zealand flew into power lines whilst conducting an approach to land. It fell to the ground, killing the pilot and all four passengers. The pilot was aware of the position of power lines and the potential hazard they posed to the flight. The pilot had previous experience flying to the planned destination, and the day before the accident flight had cycled through the area, further confirming their awareness of the position of the lines. Before departing, the company’s senior pilot had also mentioned the power lines to the pilot [1]. Despite this knowledge and the warning about the power lines’ position, a decline in depth perception led the pilot to misjudge the distance between the aircraft and the power lines. Pilots conducting helicopter flights the following day to examine the condition of the powerlines after the collision reported that the lines were easily visible, but they had difficulty judging the distance to them and on several occasions had to break away from the lines [1].

In September 2015, whilst on a cross-country navigation training exercise, a Cessna 172 collided with rising terrain. Unfortunately, the student pilot was killed in this fatal accident [2]. The accident site, when viewed from the cruising altitude, appeared to be relatively flat and level with the surrounding countryside. It was, however, the rising remnants of an ancient volcano that were higher than the surrounding countryside. While there were other issues at play in the causation of the accident, perceptual errors may have played a part in the pilot’s misjudgment of the aircraft’s height (i.e., measurement above ground level), leading to the fatal impact with the terrain.

In 2019, a Phantom 4 drone, while being used to film a rocky geological feature protruding from the sea, flew into the rocks while moving sideways, and the drone was lost. Neither the pilot nor the observer detected how close the drone was to the obstacle. The technical safeguards to protect the drone against obstacle collision did not detect the obstacle [3].

1.1.2. Depth Perception

The preceding cases demonstrate that navigating safely through an environment requires depth perception ability to determine the distance to objects in the physical environment and to be able to judge the relationship between objects at different distances, establishing a three-dimensional view of the world [4]. Navigators are thus required to exercise spatial and temporal reasoning along with depth perception skills to help develop awareness of the situation in which the flight is taking place. As well as protecting the aircraft and obstacles, safety in populated areas is of paramount importance. The last example of an accident occurring when depth perception failed was in an isolated location, and there were no people at risk of being struck by the drone after the collision. Increasing roles for drones in populated areas such as power line inspections and parcel delivery increase the risk of people being struck by a drone and highlight the need for accurate depth perception and distance estimation for future remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) operators.

1.1.3. Situational Awareness

Situational awareness (SA) has three levels of development [5]. The first level is perceptual awareness of all the elements within the current flying locality, including terrain and other objects that the aircraft could collide with. The ability to understand the spatial relationship between identified objects within the flying environment is required for SA. A further factor in the development of SA for pilots is successfully making accurate distance measurements between objects that are located at differing distances within the flying environment. This is even more so for RPA pilots as they are often located at a distance from both the drone and the obstacles that pose collision hazards; that is, they are not co-located with the aircraft, further increasing the difficulty of depth perception for RPA pilots. Lyle and Johnson [6] noted the number of incidents of drones flying into buildings and other obstacles during drone training for forensic photographers. These occurrences were diagnosed as being almost solely due to pilot error and the lack of depth perception, rather than technical issues with the link between the ground control station and the aircraft. These difficulties were seen to increase as the drone moved further away from the pilot. Murray et al. [7] identified depth perception as a leading cause of RPA accidents in Australia. For RPA operations, it is a greater cause of accidents than all powered flight in Australia. Even when conducting automated and autonomous flight, Zollman et al. [8] note the difficulty of establishing depth perception and ensuring obstacle avoidance as the pilot moves from the 2D representation of the environment on the screen to the actual live physical environment. And in the future, as RPA operators are given greater regulatory permissions to conduct beyond Visual Line Of Sight (VLOS) operations and operate more than one drone simultaneously, the challenge of maintaining a clear visual field and establishing depth perception will only increase.

1.2. Significance

Understanding depth perception has attracted much research, which is described as “voluminous and dense” ([9], p. 131), and in the nearly twenty years since this statement, the research has not abated. Although humans appear to have an innate ability to perceive depth [10], it is a difficult skill to exercise. It has been a cause of accidents in all sectors of aviation, as illustrated in the examples above. Recognition of this difficulty is noted in accident causation models. An example is the ubiquitous Human Factors Accident Classification System (HFACS) [11]. Within this model, perceptual errors are designated as one of the subcategories of Unsafe Acts.

While depth perception is a pressing requirement for drone pilots to be able to conduct safe operations now and even into the future with automated and BVLOS flights [8], it is not something that can be easily demonstrated by the pilot. Despite its operational significance in terms of safety, depth perception is not explicitly targeted in existing RPA training curricula. Instead, current programs focus on technical handling skills and regulatory knowledge, with no systematic attention to perceptual or cognitive competencies such as distance estimation and spatial awareness [12]. Yet, empirical aviation research has demonstrated that non-technical skills, including “spatial orientation”, are essential to safety performance [13]. The accident examples described above illustrate that failures of depth perception continue to be causal factors in both crewed and remotely piloted operations. Since training programs do not inherently train depth perception, the effect of basic training must first be objectively assessed to determine whether additional focused training is required. That is, safety-critical competencies require measurement and objective assessment, not assumption [14].

A partial requirement of depth perception is the determination of distance to objects in the physical environment, and to be able to judge relationships between objects at different distances [4]. The inaccuracy of observers in estimating distance has long been observed in both indoor and outdoor settings [15,16]. In both real and virtual environments, studies have shown there is a tendency to underestimate distance estimations [17]. Being consistently short or compressed has been found in multiple studies for both indoor and outdoor settings [18]. Being able to accurately estimate both egocentric and exocentric distances is difficult.

Wolbers and Hegarty [19] noted the wide range of abilities in estimating both exocentric and egocentric distances. Different variables have been identified as affecting distance estimation. Under or overestimation of distance can be influenced by the distance the viewer is from the object [20]. Daum and Hecht [20] use the term “action space” to denote the near-field region, typically within approximately 30 m of the observer, in which egocentric distance estimation is naturally most accurate due to the availability of strong visual cues. Proffitt [9] identified observer positioning and the height of their eyes relative to the placement of the observed object as having an effect on the accuracy of distance estimation. Gajewski et al. [21] identified the angle between the level of the gaze and the view downwards to the object on the ground being used by observers for the estimation of distance to objects on the ground. The nature of the task has been found to affect distance estimation [22]. Sideways movement of the observer in the viewing environment produces a change in the visual angle to the object, which affects the perception of distance [9]. The number of cues available to the observer is another variable affecting distance estimation. Loomis et al. [23] found that when observers had access to a full range of cues, their directional estimation of where objects were located was accurate. However, when viewing cues for egocentric distance estimation were reduced, the accuracy of distance estimation decreased. Distance perception is also affected by the physiology of the observer and the amount of energy that is expended in actions that require the estimation of distance, e.g., throwing a ball towards an object. The wearing of a heavy backpack leads to an object being estimated further away compared to when no backpack is worn [9]. Emotional and other social factors have also been found to influence distance estimations. One example was having people look down to the ground from balconies and estimate the distance to the ground. The distance was greatly overestimated, which was attributed to a fear of heights [9]. Another identified factor is gender. Wolbers and Hegarty [19] note there have been studies showing better male performance in “virtual maze tasks and in spatial learning from navigational experience” (p. 140). Nazareth et al.’s [24] meta-analysis of navigational abilities further identified gender differences at a “small to moderate size” (p. 1516) for different factors in navigation abilities, although the measure of distance did not produce a gender difference. A final possible variable, the age of the observer, has been found to have no effect on distance estimation [16].

With depth perception being an important skill for RPA pilots and there being many variables affecting the skill, it would be thought that ab initio training programs would introduce the trainees to depth perception estimation. Unfortunately, training programs for transport workers most often focus on technical skills and teaching the operation of machinery [25]. While these technical skills should never be ignored, it has been recognized that non-technical skills (no-techs) such as depth perception are just as important for safe operations [26]. These no-techs should be part of the initial and recurrent training received by pilots. While the proliferation of recent drone activity has been technologically driven, the human element remains a large part of the operation [27]. There is still a need to have knowledgeable and skilled operators of RPA who are adequately trained in both technical and non-technical skills.

For the training of depth perception, different methods and processes have been suggested to enhance the ability of people to safely navigate within an environment. As an example, Rauscher [28] found that college students listening to Mozart’s sonata for two pianos in D major (K488) improved their spatial reasoning abilities. Despite the success of training methods and the seeming need for RPA pilots to have depth perception skills, overt training of depth perception in RPA training programs has not been fully explored. Previous research has been conducted into students using aids for gaining depth perception [29]. In this study, the participants were undergraduate students who had to complete a tutorial session on flying a drone. They were able to use the camera image to estimate the exocentric distance between the drone and an obstacle. The current research will explore the efficacy of a mandated training program on egocentric distance estimation for students who want to gain a Remote Pilot License (RePL) as they seek to operate a drone in a professional capacity.

Although training is expected to improve technical handling, it is not established whether the standard ab initio course mandated for Remote Pilot License candidates transfers to non-technical perceptual skills, such as egocentric distance estimation. Depth perception is not explicitly targeted in the Australian syllabus. The present study, therefore, evaluates whether the existing, time-bounded training program produces measurable improvement in distance-estimation accuracy at specified ranges for VLOS flying.

1.3. Research Question and Hypothesis

While there are different technical solutions available for drone pilots to be able to accurately perceive depth and distance of the aircraft from objects, these can be expensive, not always workable or suitable for the level of operation, and not always helpful for the drone pilot. This study was conducted to assess the impact of training on the development of depth perception skills of VLOS ab initio drone pilots as measured by the estimation of egocentric distance. The null hypothesis (H0) is that completion of a standard two-day ab initio RPA flight training course will produce no statistically significant improvement in egocentric distance-estimation accuracy at specified distances within visual line of sight. The alternative hypothesis (H1) is that such structured training will produce measurable improvement, particularly beyond the action space (≈30 m).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the literature exploring RPA training is reviewed. A description of the research examining the impact of training on the development of depth perception skills is provided, followed by results and a concluding discussion.

2. Literature Review

Due to drones being affordable and easily available for purchase, people have been able to obtain a drone and then teach themselves how to fly it. As the public observes more drones in action and concerns about their activity increase, there is a reluctance to accept drones [30,31,32]. The forefront of these concerns has been privacy issues [33], but safety is also a prime issue [32,34]. The ease of accessibility allied with societal concerns has led to a growing awareness of the need for comprehensive and structured training programs and associated licensing of RPA operators [35,36]. The ever-increasing use of RPA across a range of industries and professions has been driven by technology. The technology can provide vision for navigation and obstacle avoidance [37,38,39]. Technology can be used to interpret human gestures, making it suitable for ab initio drone pilots [40]. Despite the advances in technology, the human within RPA operations remains an important component who is required to exercise depth perception skills for safe navigation and obstacle avoidance reasons [27]. Human operators require training [41]. Implementing training programs produces skilled and competent pilots who are willing to follow operating rules and do so in the safest manner [31], as well as making improvements in RPA pilot standards [42]. While the technology that drives the use of drones is ever advancing, there is a growing awareness that “drone operator skill development seems to lag far behind” ([43], p. 3). Low and Yang [44] describe training as one of the cornerstones of safety (p. 603) and noted the importance of the training of aviation staff to provide for safe outcomes of aviation operations. There is an increasing recognition that individual or in-house training no longer suffices and should be supplanted by planned, systematic training programs [45].

As a developing sector of aviation, the training curriculum and associated syllabi for RPA are in an emergent stage with varied requirements of what should be taught [46]. For conventionally crewed aviation, there has been, through the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) Annex 1 and associated Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs), the promulgation of the minimum standards required for personal licensing. They have been foundational to safety and aligning practices around the world, leading to the standardization of training across international jurisdictions. With the upsurge in RPA activity across the world, there has not been a corresponding harmonization of rules for RPA [41], with a resulting lack of standardization in training RPA pilots. This has resulted in different jurisdictions implementing different training systems and licensing standards, including subject matter [43]. In some instances, no formal or documented training is required. In New Zealand, operators are permitted to fly a drone under 25 kg outside 4 km of an aerodrome without a license, subject to the following operating rules contained in Part 101. And there can be differences in training requirements according to the level of drone usage. In the USA, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has two different certificates. One certificate is for those wanting to use RPA for commercial purposes (FAA Part 107), and the second is the Recreational UAS Safety Test (TRUST) for recreational users [42]. In the EU, there is a risk-based approach resulting in not distinguishing between commercial and non-commercial operations [47]. In Australia, a RePL is required for commercial use of drones weighing more than 2 kg, but if operating a commercial drone weighing less than 2 kg, a RePL or any official license is not required. A prescriptive competency-based syllabus for both the theory and practical training has been introduced in Australia for the issuance of a RePL (see Appendix A).

ICAO [48] has issued a Manual of RPA with guidance on licensing and RPA observer competencies. The ground theory subjects for a remote pilot license encompass a suite of subjects taken from an extant conventional crewed flight syllabus. They do not always target specific RPA applications. The Manual also describes the requirement for a practical demonstration of competent handling of the drone. There is a reference to the need to demonstrate threat and error management, sound decision making, airmanship, and the ability to apply aviation knowledge to the flying situation [48].

There appears to be a need for theoretical knowledge and practical skills in flying the aircraft to be part of the comprehensive training program. Requiring only theoretical knowledge can lead to an unwarranted assumption of drone operating skills [35,49]. The UK A2 Certificate of Competency, used for recreation or commercial purposes, is described as very theoretical with students self-teaching flying skills [43].

With only guidance material, there is currently a lack of SARPs forming cohesion amongst RPA training programs across different jurisdictions [7]. This vacuum has led to different suggestions for what should form part of the training regime for RPA pilots. Examples of differing syllabus suggestions have included using buckets attached to stands with the open end pointing upwards as targets for the drone pilot to fly to and hover over so the pilots can be assessed on maneuvering and payload functionality skills [50]. An outcome of this lack of coordination is that existing training programs are inadequate to meet the needs of students [43,51].

The array of tasks for which drones are being used is a challenge for RPA training. One generic form of training may not be sufficient [43]. Foundational training in common skills may be needed, followed by specific training aimed at a particular task the pilot is going to undertake [52]. Safety training is also recognized as an important goal of aviation training programs [43], and RPA should not be excluded from this goal.

The problem of what material to teach ab initio RPA pilots can, in part, be answered through the gathering of empirical data from actual operations and training sessions, along with discussions with experienced pilots [45,53]. Retrospectively exploring accident databases can identify gaps in the knowledge and skills of RPA pilots that lead to unsafe outcomes [7,54]. A comprehensive analysis of training needs for professional drone pilots identified technical skills, theoretical knowledge, and non-technical skills as requirements for drone pilots [45]. The latter included personality traits, communication skills, and cognitive skills. The cognitive skills required for drone pilots encompassed three-dimensional perception, spatial awareness, distance estimation, monitoring, and reaction time [45,55]. Adams and Hagl [13] identified the required specific human performance for RPA pilots, confirming the need for both technical and non-technical skills, including situational awareness.

RPA training can be influenced and enhanced by gaming [56]. Suggested benefits of using gaming as part of the training process include learner motivation and engagement. For a younger demographic raised with the ubiquity of gaming, familiarity makes training more enjoyable and produces more successful outcomes. These include enhanced engagement and retention of operational knowledge and hands-on flying skills, and non-technical skills [36].

Ab initio pilots are the most visible target of training programs, but consideration also needs to be given to recurrent training programs for experienced drone pilots [45]. Flying skills are perishable, and constant practice is required to maintain them to the highest standards [57]. As the RPA sector matures, this form of training will also need to be implemented. It will need to address skill retention but also exposure to technological advancements that arise. Continual learning and training over the course of their career will be required of RPA pilots [45], given that formal licensing does not always translate into operational discipline [58].

Training is one of the cornerstones of safety [57]. Its importance in providing safe outcomes of aviation operations is understood [41]. Training of drone pilots has been found to produce positive improvements in flight performance [59]. The review of the literature suggests that self-teaching to fly a drone is not a safe option. Formalized training of future RPA pilots is required to produce skilled operators who can fly safely [42]. Training of RPA pilots who are required to accurately estimate distances can lead to better outcomes. Nadeau and Conway [60] suggested that better training in distance estimation was an easy way to improve these skills.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology utilized in the study was a one-group pre-test–post-test design to measure the impact of the training course on the depth perception abilities of the ab initio pilots. This design constitutes a pre-experimental design, as it lacks random assignment and a control group [61]. This design was selected to preserve the ecological validity of a commercially delivered, regulator-approved course that could not be altered for experimental randomization. A between-groups or repeated-trial structure would have required modifications to the delivery sequence and assessment procedures, which are standardized under Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) authorization. The one-group pre/posttest, therefore, provides a practical means of measuring within-participant change while maintaining the legally required operational authenticity.

While the design detects a change in response to an intervention, it has inherent limitations. Leedy and Ormrod [61] note that it “provides a measure of change but yields no conclusive results about the cause of the change.” Without a control group or randomization, the observed effects cannot be definitively attributed to the training intervention alone. Nonetheless, this approach is appropriate given the operational constraints and the study’s aim to evaluate performance within the authentic training environment.

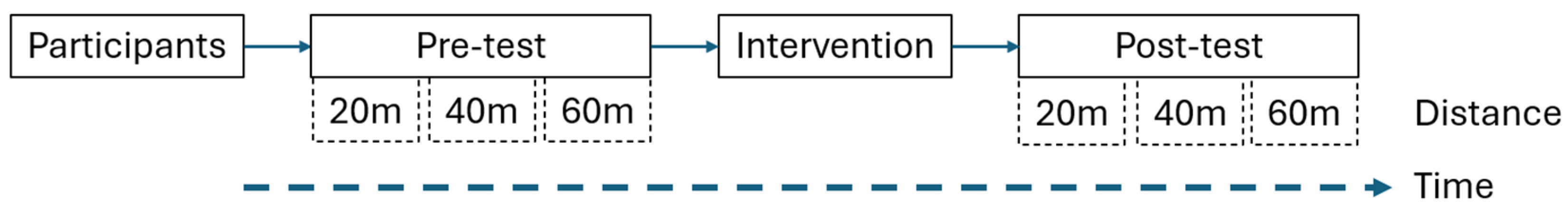

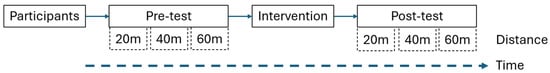

Although the use of a single estimation trial at each distance introduces greater variability than multiple-trial averaging, it avoids participant learning effects within a session and mirrors the real-time perceptual judgements made by remote pilots in live operations [62]. Environmental conditions, aircraft type, instructors, and measurement procedures were held constant to minimize the potential confounding variables. The basic research design is illustrated in Figure 1. The study was approved by the Human Research Advisory Panel of the University of New South Wales (iRECS 4677). As a condition of this minimal-risk ethics approval, no demographic or experiential information was collected from participants. The approved protocol prohibited the recording of any identifiable or quasi-identifiable details, including age, gender, gaming experience, technical background, or dominant eye. Data collection was therefore limited to performance-based measures obtained during the training activities.

Figure 1.

Experimental design showing the one-group pre-test/post-test structure used to measure changes in distance estimation accuracy at 20 m, 40 m, and 60 m before and after the training intervention.

The training course used in this study followed the syllabus of CASA [63], the national regulator, and involved both theoretical subjects and practical training in handling the drone. The teaching of the course was performed by a private organization specializing in RPA training at different venues across Australia. The students enrolled in the training course were seeking to gain a RePL. The program for the five-day course was the first two days spent in the classroom devoted to the teaching of the theory subjects. Days 3 and 4 were conducted at the flying field, where the students learned to fly the drone. Passing this component of the course required completing at least 5 h of flying, passing the competencies, and passing a flight test. The competencies involved handling skills performed in a 20 m by 20 m square as indicated by cones on the ground and distance work with the drone at a distance of more than 100 m from the student while remaining in visual line of sight. The aircraft used for training were the DJI (Shenzhen, China) Phantom 4 and the DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise. Day 5 was in the classroom where the students had to sit an examination covering the theory learnt in the first two days. Successful completion of the flying syllabus and passing the theory examination earned the student a RePL.

Participants in the study were students undertaking the training course. At the end of day 2, they were approached to take part in the study. Students with prior experience flying a drone were excluded. This is necessary to remove the confounding or confusion variable of pre-existing perceptual calibration that might come with prior drone experience, which ensures a homogenous ab initio sample. The number of participants who agreed to take part was 30. On the morning of day 3, before formal flight training commenced, those students who had agreed to take part were pre-tested and asked to fly a DJI Phantom 4 away from them in a straight line. They had to stop and hover the drone when they estimated it was directly above a cone on the ground located 20 m away from them. During the hover, the distance of the drone was measured using a range finder. Continuing to fly in a straight line, the student flew the drone to a cone placed at 40 m and stopped and hovered when they estimated the drone was above the cone. The actual distance was measured. This was repeated flying to a cone 60 m from the student. Beyond 60 m, the DJI Phantom 4 falls below the ergonomic 0.25° discriminability threshold [64].

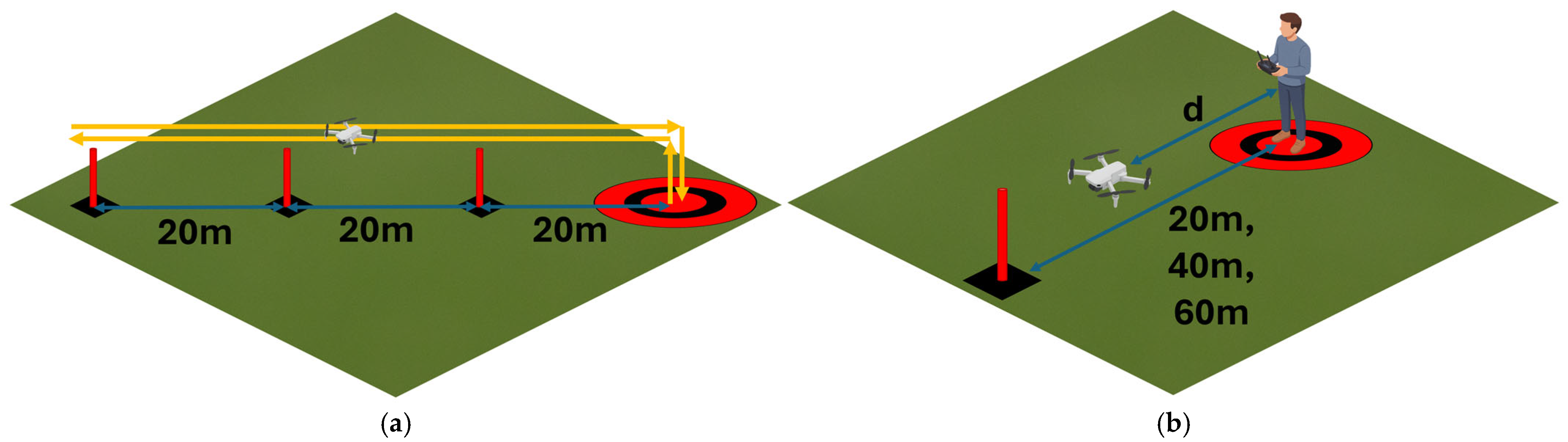

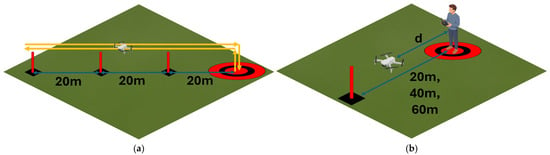

The flight took off from a flat, grassy Australian Rules Football field. Although Australian Rules Football playing fields have minimal line markings, the flying was conducted across the width of the field so that the shape of the field and the markings could not aid the participants. As required by CASA to ensure VLOS for RePL operations, the weather conditions were CAVOK (ceiling and visibility okay), which means visibility was greater than 10 km, and there were no clouds below 5000 ft. On all days for data collection, the temperature ranged from 20 °C to 35 °C, and the sky was actually clear with a blue sky as the background. The setup is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup: (a) flight path, from the take-off and landing point (round bullseye) to the three upright targets at 20 m increments (20 m, 40 m, and 60 m), and (b) showing the distance measured to the drone from the operator (egocentric distance), d.

The students then completed the practical training course over days 3 and 4, with a minimum of 5 h flying and successfully meeting performance competencies. On day 4, after successfully completing the flying training, the students were post-tested and measured following the same procedure of flying out to and hovering above cones at 20 m, 40 m, and 60 m from them. Data was collected during the months of August to November 2024, and flights occurred consistently around 8 am.

4. Results

4.1. Data

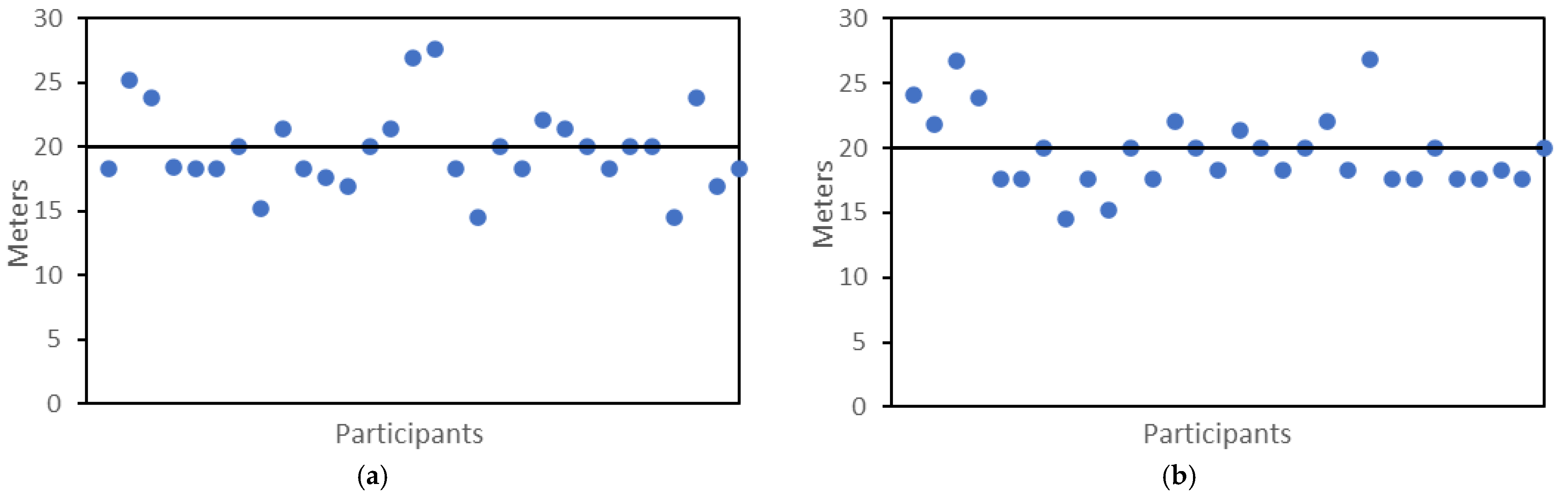

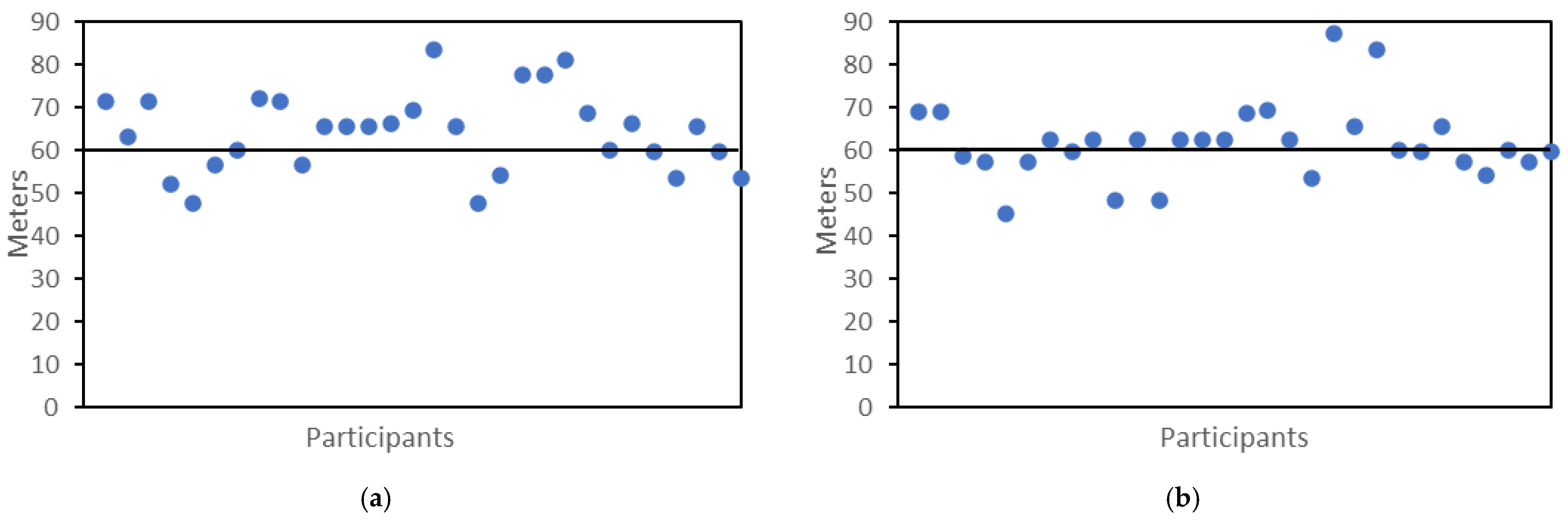

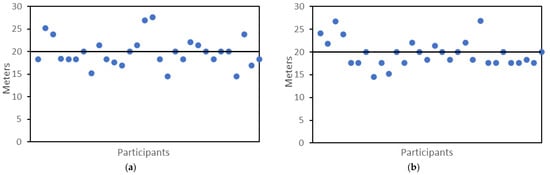

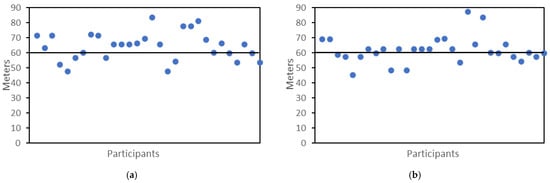

The range of distance estimations during pre-testing at the 20 m marker cone was 14.5 m to 27.6 m (Figure 3a) with an average estimation of 19.8 m (Table 1). The range of distance estimations during post-testing at the 20-meter marker cone was 14.5 m to 26.9 m (Figure 3b) with an average estimation of 19.68 m (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Measurement of pre-test and post-test student distance estimations at the 20 m cone; (a) Pre-test measurements at 20 m, and (b) Post-test measurements at 20 m.

Table 1.

Mean hover distance estimations and S.D. for pre- and post-test at 20, 40, and 60 m distances.

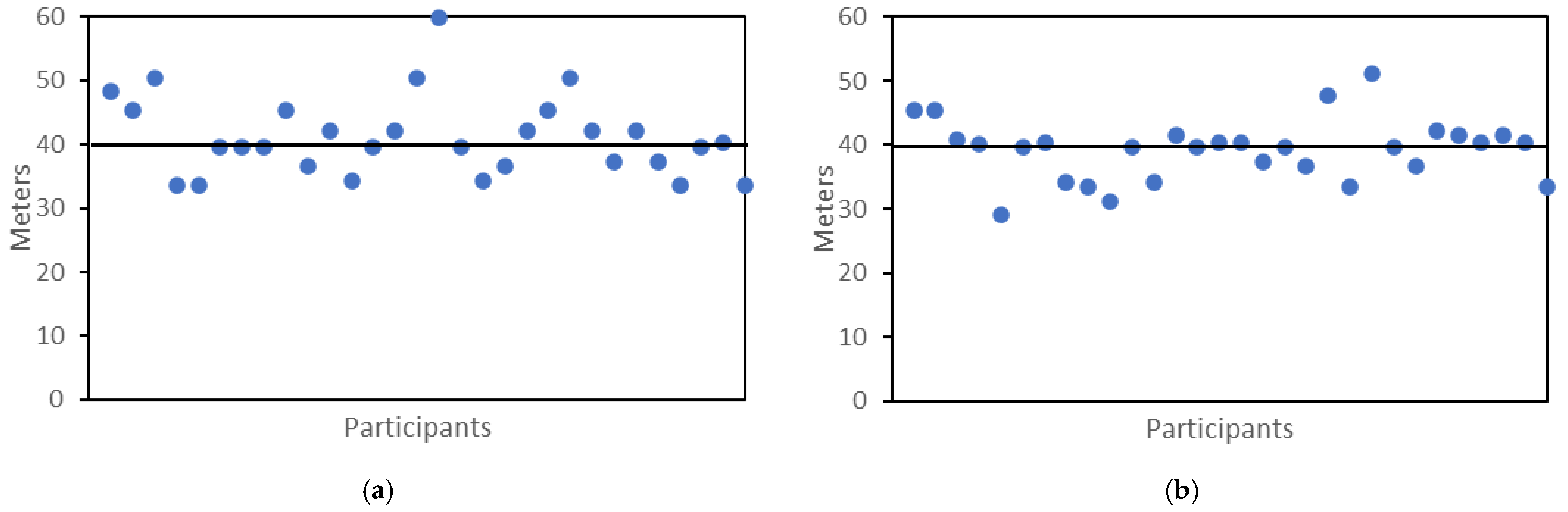

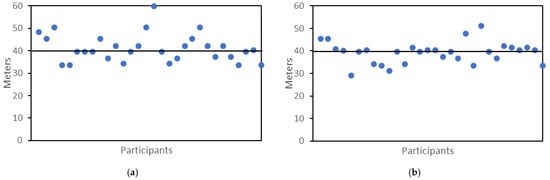

The range of distance estimations during pre-testing at the 40 m marker cone was 33.5 m to 59.8 m (Figure 4a), with an average estimation of 41.18 m (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Measurement of pre-test and post-test student distance estimations at the 40 m cone; (a) pre-test measurements at 40 m; (b) post-test measurements at 40 m.

The range of distance estimations during post-testing at the 40 m marker cone was 29.0 m to 51.2 m (Figure 4b), with an average estimation of 39.23 m (Table 1).

The range of distance estimations during pre-testing at the 60 m marker cone was 47.7 m to 83.7 m (Figure 5a), with an average estimation of 64.43 m (Table 1). The range of distance estimations during post-testing at the 60 m marker cone was 45.3 m to 87.5 m (Figure 5b), with an average estimation of 61.84 m (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Measurement of pre-test and post-test student distance estimations at the 60 m cone; (a) pre-test measurements at 60 m; (b) post-test measurements at 60 m.

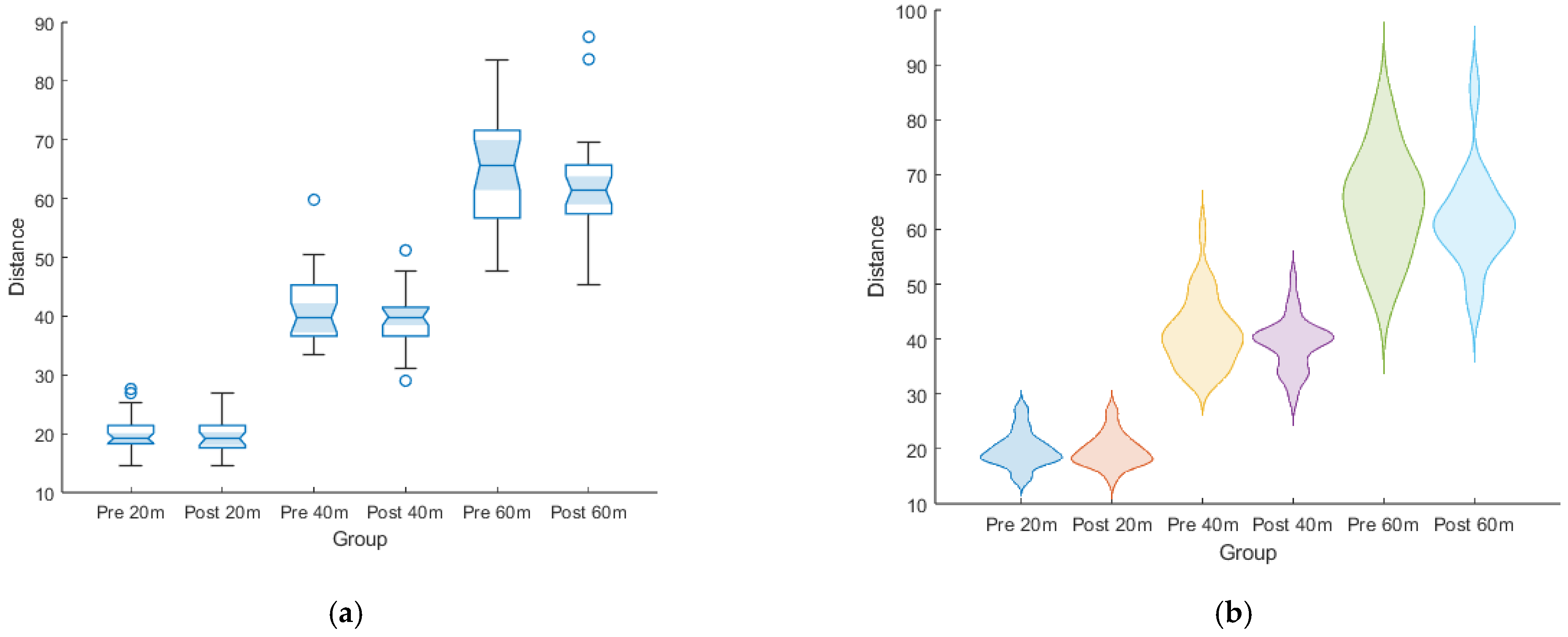

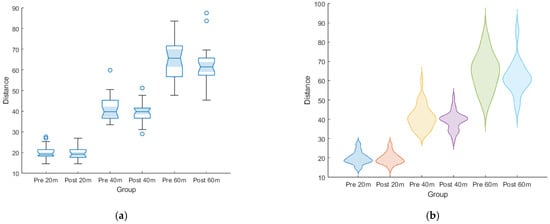

During the post-testing, 13 of the 30 students improved their distance estimation when attempting to hover over the 20 m cone. When flying to the 40-metre cone, 11 of the 30 students improved their distance estimation, but at the 60-metre cone, 18 of the 30 students improved their distance estimation. The distance estimations of the drone from the participants at each of the three measured distances are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Plots showing the differences between student estimation and actual distance to the respective cones; (a) notched box plots and (b) violin plots, highlighting the equivalence of the variance.

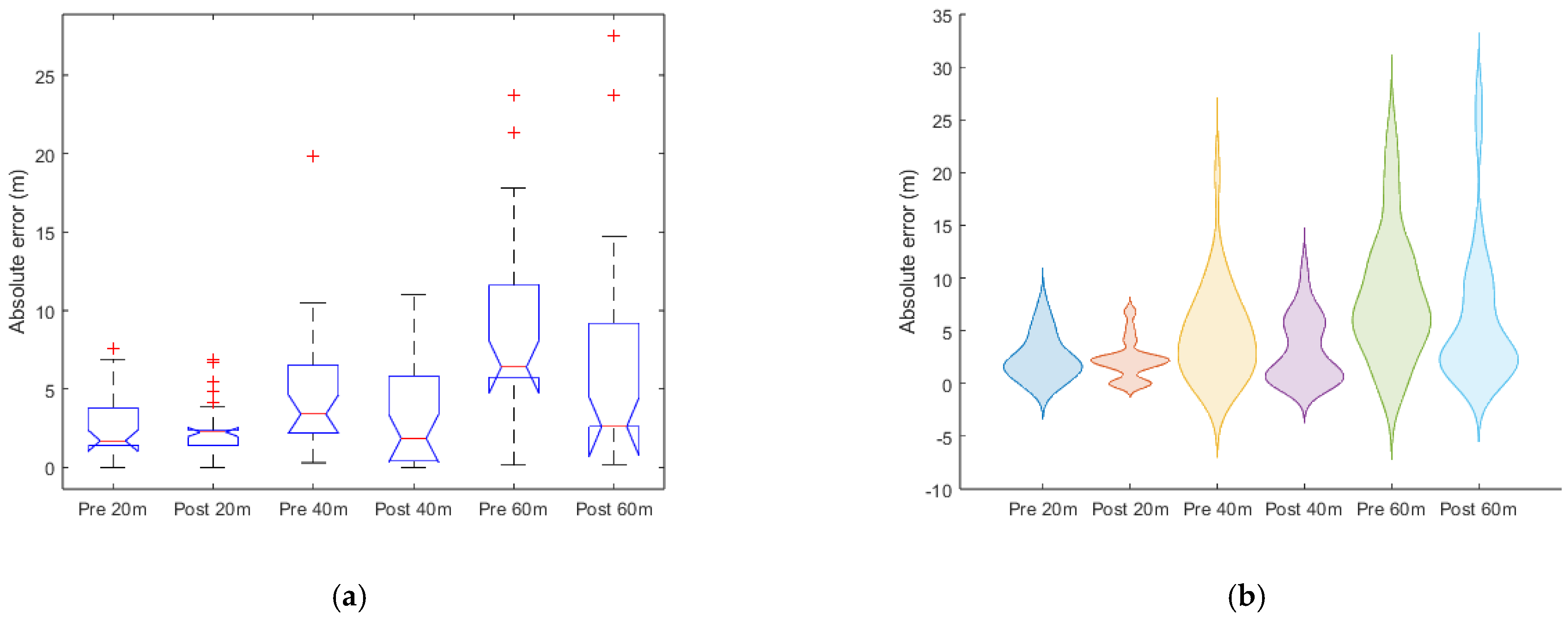

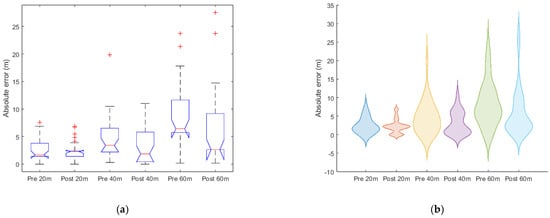

In addition to the actual distance measurement, we can consider the absolute error in the distance measurement. These results are shown in Figure 7. The reiterate what is shown by the spread of the data in Figure 6, that the absolute error grows with distance, and it reduces after training.

Figure 7.

Plots showing the absolute error of the distance estimation, (a) notched box plots and (b) violin plots. Note: the negative inferred value for the violin plot is one of the reasons some do not like their use.

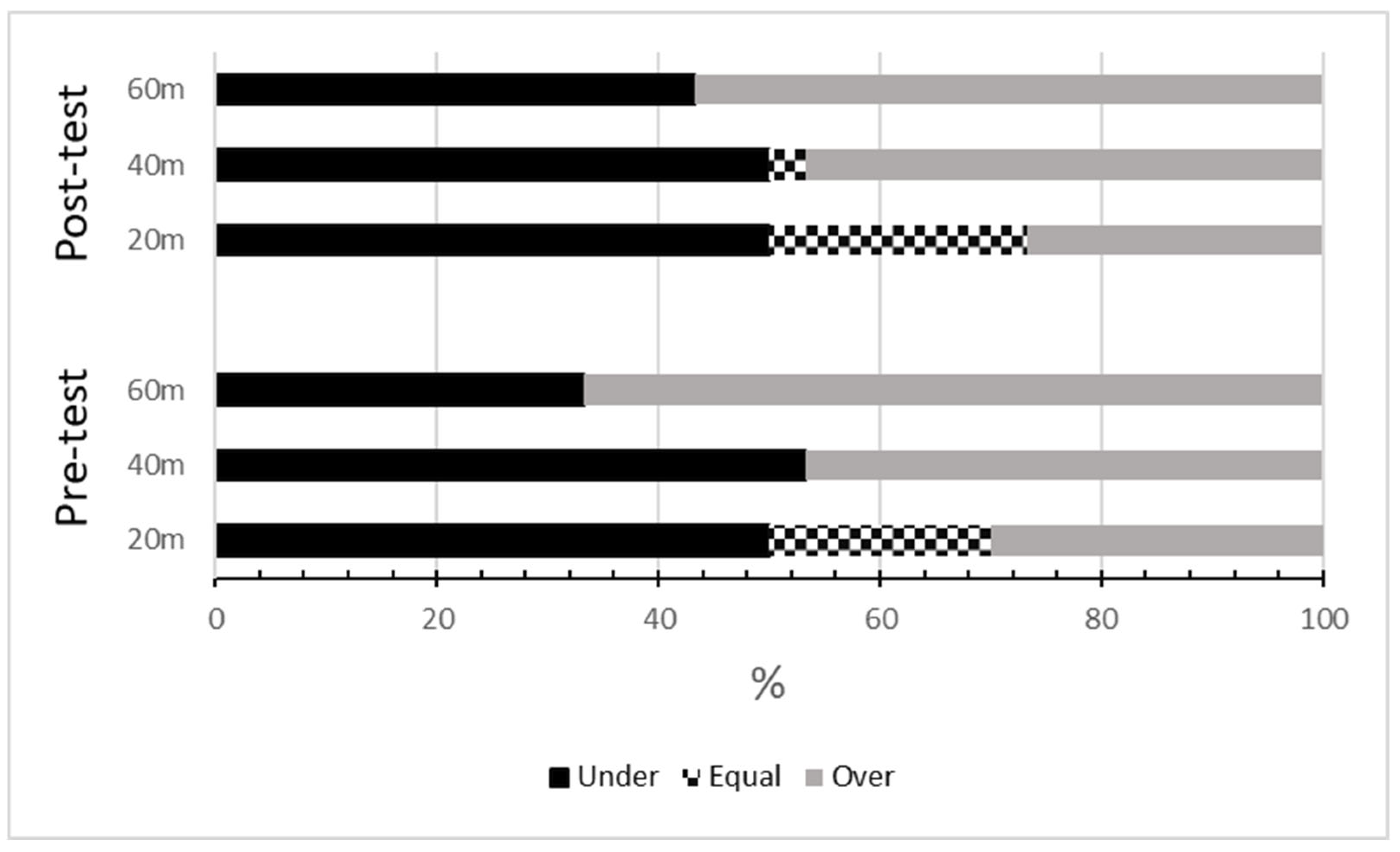

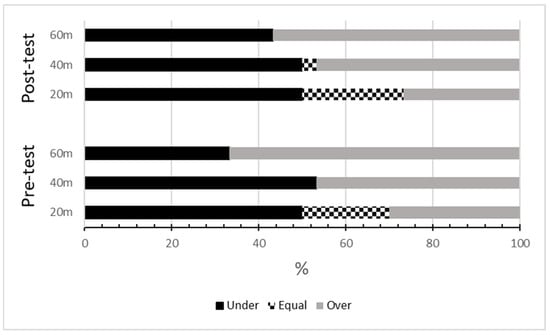

During the post-test, 26.6% of the students overestimated the drone’s distance from the 20 m cone. The overestimation of the drone at the 40 m cone remained constant at 46.6%. At the 60 m cone, there was an improvement in the number of students overestimating the distance of the drone, with 56.6% of students overestimating the distance of the drone, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Percentage of under- and overestimation of distance between the drone and cones at 20 m, 40 m, and 60 m.

4.2. Accuracy (Central Tendency)

From Table 1, the change in two metrics is of interest when looking at operators’ distance estimation. The first is the mean score, which is representative of accuracy, and the second is the deviation, which is representative of the precision. Hence, accuracy is defined as the degree to which the mean measured distance corresponds to the true physical distance. The purpose of the data analysis is to then fit a general linear model (GLM) to the accuracy performance over the 3 distances, comparing before and after. This accuracy model examines whether training improves the calibration between true distance and perceived stopping distance. The chosen model is, therefore, as follows:

where y is the measured distance, x1 is the target distance, x2 is the training (0 for pre-training and 1 for post-training), and the β’s are the three associated coefficients to be fit to the model.

This model is based on the idea that prior to training, we would expect the following relationship:

That is, there will be a simple correlation between the distance measure and the target distance; the expected slope here would be 1 with perfect perception, then assuming an intercept of zero, a slope greater than 1 corresponds to an overestimate, while a slope less than 1 corresponds to an underestimate. Then, to determine if the training had an effect, this will be present in the post-training data, in the following form:

That is, the measurable effect of the experiment will be a statistically significant β2, which is the improvement to the measured distance from the target distance, after training, so the same original values of β1 and β0. The combination of (2) and (3) is then literally (1), via the use of x2.

Table 2 shows the summary of the parameters obtained from the multiple linear regression for the accuracy model. The overall F-score was 704.7, with 2 predictors, and 177 degrees of freedom, giving a p-value of the model of 5.1 × 10−85, with an associated R2 of 0.89. In terms of the coefficients, we note that clearly the distance is very significant, which is not surprising, given that it is the correlation of the distance measure to the distance targeted. Importantly, the associated statistically significant coefficient is 1.107. That is, on average, the drone operators overestimated their distance by 10 percent prior to training. For the effect of training, the coefficient is again statistically significant, with a value of −0.0436. That is, after training, the 10 percent overestimate was reduced to a 6 percent overestimate. Interestingly, the intercept is almost statistically significant, suggesting a systematic offset for all drone operators of 2.4 m. This appears to moderate the 10 percent overestimate at shorter distances, noting that in Figure 6, improvement increases with increasing distance. Hence, at 24 m, this model suggests that the estimated distance is equal to the target distance; below 24 m, there is a potential underestimation, and over 24 m, there is an overestimation. Critically, the p-value is not statistically significant (at the 95 percent confidence level), hence the “suggestion”.

Table 2.

Summary of model parameters for accuracy.

4.3. Precision (Spread)

Noting precision is the ability to reproduce the same result, unlike accuracy, which is the ability to reproduce the true value. Hence, precision is defined as the magnitude and consistency of estimation error across participants, quantified here by absolute error and its distribution. Given the same analytical intent, exactly the same model is used as above (1). The only difference is that y is now the measured absolute deviation. Again, the intent is to see if this absolute deviation changes (increases) with distance, and if it improves (reduces) with training.

Table 3 shows the summary of the parameters obtained from the multiple linear regression for the precision model. The overall F-score was 20.77, with 2 predictors, and 177 degrees of freedom, giving a p-value for the model of 7.9 × 10−9, with an associated R2 of 0.19. The distance coefficient is once again highly statistically significant, with a value of 0.138, indicating that the absolute deviation (spread) of the data increases by 1.4 m for every 10 m the drone is away. For the effect of training, the coefficient is now more statistically significant than in the accuracy model, with a value of −0.0356. That is, after training, the 1.4 m spread every 10 m was reduced to 1 m. The intercept is not significant, which is expected for absolute data with a minimum of zero.

Table 3.

Summary of model parameters for precision.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

Depth perception is an important ability for drone pilots and is a greater requirement for RPA pilots than for conventionally crewed aviation [7]. Asking participants to estimate egocentric distances prior to completing training to earn a RePL and post testing at the completion of the course, the impact of a training course on the development of depth perception of ab initio RPA pilots was evaluated

The analysis showed that ab initio pilots have a propensity to overestimate their distance by approximately 10 percent. The intervention with the CASA-approved training syllabus appears to have improved the accuracy of the group by reducing the overestimation to approximately 6 percent. When looking at the data in Figure 6 and Table 1, this appears more important at 40 and 60 m distances, but this is where the GLM with the intercept adds insight. Although not significant at the 95 percent confidence level, with a value of 94.4 percent confidence, the intercept suggests a range where the implied systematic offset of 2.4 m, cancels out the overestimation, which is at 24 m prior to training, and increases to 40 m after training.

The training course devoted a large amount of time to handling the drone within a 20 m by 20 m grid, which could lead to an expectation that there would be an improvement at this distance. The lack of significant improvement in the depth perception of the participants at the 20 m marker can be explained by their operating within a vista described as the “action space”, of up to 30 m from the participant [20]. Within this action space, distance estimation is very accurate [20], which was observed in the results. For the participants, being asked to fly the drone at 40 and 60 m may have been the first time they had to operate outside this action space. The training program undertaken by the participants exposed them to working at greater distances. This provided the opportunity to gain experience in distance flight and learn the skills of egocentric distance estimation.

In addition to the grid work, the training course also required participants to fly the drone out to 100 m and to fly around the perimeter of the training location. It has been found that greater distances present more challenges for the depth perception skills of RPA pilots [6]. The impact of the training program on improvements was most pronounced at 60 m. The provision of training exercises in operating a drone at greater distances provides participants with the opportunity to enhance distance estimation and build depth-perception experience for the greater distances that can be expected to be faced in RPA operations. The results suggest that a structured training program is beneficial for developing this skill. The noted improvement in distance estimation supports Schmidt et al.’s [45] suggestion for the training of future RPA pilots to include spatial awareness and distance estimation.

The literature notes the constancy of egocentric distance estimation to be short or underestimated [17,18]. This was partially borne out in this study. Most students accurately or underestimated the distance to both the 20-meter and 40 m cones (Figure 8). This was for both pre-testing and post-testing. At the 60-meter cone, however, the percentage of students underestimating the distance of the drone was less than half during pre-testing. There was an improvement in post-testing, but the percentage of students underestimating was still less than 50%. Daum and Hecht [20] identified distance underestimation up to 75 m. They note there is a crossover point where the underestimation of the distance becomes an overestimation, which they suggest is around the 100 m mark. The results indicate there was a crossover point between under- and over-estimation for the participants when asked to fly a drone, but it was well before the suggested 100 m. As implied by the almost statistically significant intercept in the accuracy model, this was about the 24 m mark.

The tendency towards under- and overestimation of distance has implications for increased collisions with obstacles in the flying field. A review of an RPA accident database found many pilot reports of drones flying into objects [7]. When the drone is further away from the operator than is perceived, there are greater opportunities for the drone to collide with objects such as trees and buildings in the flying environment. The lack of accurate estimation of distance can provide an explanation for the frequency of these collisions found in the accident database.

5.2. Recommendations and Further Implementations

For national regulators devising a training syllabus for ab initio RPA pilots, the results support the inclusion of requirements to have students fly the drone away from the training grid and operate the drone at a distance. Greater emphasis and exposure to flying the drone at greater distances may reap safer outcomes. Regulators may also consider the efficacy of training over two days and whether it is worthwhile to increase the amount of training that is required to gain a RePL. If there are improvements made over two days would a third day of flight practice produce further improvements? There are two avenues to answer this question. The first is for researchers in a different context with a more substantial training requirement to determine if they observe a greater effect size with a longer training duration. The second would be to fund a research project that would require CASA approval to have a modified training program that has a longer duration. As the syllabus matures in response to continued understanding of what is required for the safe operation of drones, these results, along with those from future studies, can inform and shape the training provided to future RPA pilots.

Taken together, the findings allow several training implications to be articulated more explicitly. First, the evidence indicates that the current two-day practical component yields measurable improvement, mostly beyond the near-field action space, suggesting that training programs would benefit from structured exposure to distances greater than 30 m. Second, while standard square and figure-eight maneuvers develop handling skills, they offer limited opportunity to practice egocentric distance estimation at operationally meaningful ranges. Supplementary exercises that require deliberate perception-based judgment, such as repeated outward-and-return flights to varied distances or structured hovering tasks at non-grid locations, may therefore enhance the transfer of perceptual skill. Third, the plateau observed at 20 m implies that additional hours alone are unlikely to change near-field accuracy; increased duration should instead be paired with targeted tasks designed to challenge depth perception at greater distances. These recommendations build directly on the pattern of results and remain compatible with existing regulatory requirements, while providing clear directions for refining future training programs.

In addition to longer training programs or looking at the influence of accumulated flight experience, there could be potential benefits from simulator time. The use of flight simulators is central to conventional crewed aviation training [65]. Recent work has also demonstrated that simulators improve RePL training performance in terms of the simple flight maneuvers conducted as part of the CASA syllabus [60]. As such, simulator time may improve depth perception, although a virtual reality approach would likely be of more interest.

5.3. Limitations and Potential Improvements

The testing task was intentionally simplified to isolate the perceptual component of distance estimation. By using a single aircraft type, uniform weather, and minimal background clutter, the design reduced variability that could obscure changes attributable to training. While such control limits direct generalization to operational contexts that include variable lighting, terrain texture, or atmospheric conditions, the simplicity strengthens internal validity and allows clearer inference about perceptual learning itself. Hence, as noted previously, the study consequently adopted a quasi-experimental, one-group pre-test/post-test design, an approach appropriate for applied educational and behavioral research where randomization is impractical, and the intervention cannot be modified [66]. Although this limits the capacity for definitive causal attribution, the consistency of the observed results provides credible evidence that perceptual improvement occurred.

Recognizing these methodological constraints, the present study provides a foundation for future confirmatory work. Subsequent studies should employ comparative groups, repeated measures, or longitudinal tracking to validate and extend the observed effects under more operationally realistic conditions. For example, different meteorological conditions, including variable wind levels and different cloud conditions. Another important variable to investigate is environmental complexity; while the majority of training may occur in open green spaces, practical operations occur around structures and other objects and obstacles, where the complexity of these could help or hinder performance. Other future areas of research can be identified. The aircraft used for the testing was the Phantom 4 drone, which was colored white and is in the weight category of sub 2 kg. Future testing of variables affecting depth perception amongst RPA pilots could include small (2–25 kg), medium (25–50 kg), and larger drones, as well as differently colored drones.

Another area is the distances that are examined. This study only explored distance estimation out to 60 m, but the RPA pilots may well face having to fly the drone at greater distances than this. Testing at distances of 100 m or more would indicate whether there are special considerations for larger distances. Another is examining the depth perception skills of experienced RPA pilots. This study utilized ab initio students who, at the end of their training, had 5 h of flight experience. When pilots leave the training program and move into operations, the question arises whether more operational hours improve these skills. Understanding the effect of experience can help regulators set the number of hours students should fly in a training program to ensure skilled pilots enter the RPA operational realm. In conjunction with flight experience, the age of the students can also be a variable that can be measured for differences in drone flying and estimating distances.

As has been alluded to, a true experimental design is recommended for future work. This was not possible in the present study, as such a design would require a control group in which participants did not receive the required CASA-approved training and, consequently, would be unable to obtain the RePL for which they were explicitly training. Cahit [62] also suggests a time-series quasi-experimental design; however, this would require research ethics approval beyond negligible risk, as depth perception would need to be measured repeatedly both prior to and following training over an extended period. In addition to being outside the scope of the existing ethics approval, such an approach was not acceptable to the flight training organization from which the data were collected, given the extended interaction it would require with students.

Further work could address these limitations through purpose-designed studies conducted outside regulatory training pathways, enabling the use of control groups or longitudinal designs without constraining participant certification outcomes.

5.4. Future Work

A further avenue for future work concerns training architectures that differ from the CASA-mandated RePL model examined here. The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) Training Standard [50], used in the United States for small UAS operations, incorporates repeatable maneuvering tasks and standardized obstacle interactions that may also affect egocentric distance estimation. Because this protocol is not part of the Australian licensing syllabus, its influence on perceptual skill development could not be evaluated in this study. Comparative research in jurisdictions where NIST-aligned training is implemented would therefore be valuable to determine whether its scenario-based structure yields improvements in distance-estimation accuracy comparable to or greater than those observed in the present work.

With the aim of expanding the current implemented pre-experimental design, moving to a true-experimental design will require randomization, hence a larger sample size, and a control group. This will likely involve no structured training, flying for the same number of hours per day over three days, and supervised, to match some but not all of the conditions of the structured training. This scale of investigation will require suitable funding, which, based on the initial correlations noted within this study, is a viable direction.

6. Conclusions

Flying a drone presents challenges because the RPA pilot is not co-located with the drone. One of the challenges has been depth perception and distance estimation, with accident databases recording many instances of drones colliding with obstacles [6]. Training of RPA pilots to overcome these challenges has not always happened. At the beginning of the RPA upswing, pilots were left to self-train. While some national regulators have introduced formal training programs for those seeking to obtain a license or certificate to operate an RPA, others do not require formal qualifications.

The null hypothesis can be rejected: the GLM shows measurable improvements occurred beyond 24 m, with reliable distance estimates extending to 40 m post-training, expanding the near-field action space past the initial 20 m, where baseline accuracy was already high. The observed statistically significant reduction in the overestimate from 10 percent down to 6 percent demonstrates that the existing two-day RePL practical course produces tangible, transferable gains in egocentric distance estimation without explicit perceptual training. These findings suggest that current syllabus design is broadly sufficient for basic perceptual skill transfer, while further dedicated modules or extended flight practice may yield additional benefit at greater ranges. Future work is required, using a true experimental design to confirm these hypotheses and demonstrate a true causal relationship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and G.W.; methodology, J.M. and G.W.; validation, J.M., S.R., K.J. and G.W.; formal analysis, J.M., G.W. and S.R.; investigation, J.M. and G.W.; resources, J.M. and G.W.; data curation, J.M., S.R. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M., S.R., K.J. and G.W.; visualization, J.M. and G.W.; supervision S.R., K.J. and G.W.; project administration, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Human Research Advisory Panel of the University of New South Wales (Approval iRECS4677).

Data Availability Statement

The data sets presented in this article are not readily available due to restrictions on their distribution to parties external to the original research, in accordance with ethics approval. Requests to access the datasets should be directed in the first instance to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eve Slavich, statistical consultant at the Mark Wainwright Analytical Center at UNSW Sydney, for advice on the statistical models for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Licensing of low-risk, commercial operations.

Table A1.

Licensing of low-risk, commercial operations.

| Jurisdiction | License/Certificate | Requirements | Weight Restrictions |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA [66] | Yes, Part 107 Remote Pilot Certificate | Written knowledge exam Read and speak English | Up to 25 kg |

| New Zealand [67] | No | Comply with Part 101 operating rules | Up to 25 kg |

| Yes, Part 102 Unmanned Aircraft Operator Certificate (UAOC) | Safety case Operations manual Possible flight assessments Or further training | Above 25 kg | |

| Australia [68] | No | Operator accreditation Comply with part 101 Standard operating conditions | Below 2 kg |

| Yes, Remote Pilot License | Written knowledge exam Practical flight training (min. 5 hrs) Flight test | 2–25 kg | |

| Europe [69] | No | Familiarity with the user manual | C0 below 250 g |

| Yes, A1 (fly over people but not over assemblies of people) | Corresponding online training course Corresponding theory examination Familiarity with the user manual | C1 below 900 g | |

| Yes, A3 (fly far away from people) | C2 below 4 kg C3 below 25 kg C4 below 25 kg | ||

| Yes, A2 (fly close to people) | C2 below 4 kg |

References

- Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Hughes 369FF ZK-HJN, Wire Strike, West Arm, Lake Manapouri, 28 March 2000. AO-2000-005. Author Wellington, NZ. 2000. Available online: https://taic.org.nz/inquiry/ao-2000-005 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Collision with Terrain Involving Cessna Aircraft Company 172S, VH-ZEW. Aviation Occurrence Investigation AO-2015-105. Author, Canberra, ACT, Australia. 2018. Available online: https://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/investigation_reports/2015/aair/ao-2015-105 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch. DJI Phantom 4 PRO, (UAS Registration n/a) 150919 03-20 AAIB Bulletin: 3/2020 2020. Author, United Kingdom. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/aaib-reports/aaib-investigation-to-dji-phantom-4-pro-uas-registration-n-a-150919 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Bartsch, R.; Coyne, J.; Gray, K. Drones in Society. Exploring the Strange New World of Unmanned Aircraft; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Endersley, M.R. Situation awareness in aviation systems. In Handbook of Aviation Human Factors; Garland, D.J., Wise, J.A., Hopkin, V.D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Lyle, A.L.; Johnson, M. Drone photography. In Handbook of Forensic Photography; Weiss, S.L., Ed.; CRC Press: Bocca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.; Richardson, S.; Joiner, K.; Wild, G. Identifying Human Factor Causes of Remotely Piloted Aircraft System Safety Occurrences in Australia. Aerospace 2025, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollmann, S.; Hoppe, C.; Langlotz, T.; Reitmayr, G. FlyAR: Augmented Reality Supported Micro Aerial Vehicle Navigation. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2014, 20, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, D.R. Distance perception. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, S.B. Behavioral and developmental studies of visual depth perception. Am. J. Optom. Arch. Am. Acad. Optom. 1971, 48, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Shappell, S.A. A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis: The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, N. Pass the FAA Drone Pilot Test: Remote Pilot Exam Preparation 2020; Geospatial Institute: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, F.; Hagl, M. RPAS Over the Blue: Investigating Key Human Factors in Successful UAV Operations. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P.; Campbell, J.; Newon, J.; Melton, J.; Salas, E.; Wilson, K.A. Crew Resource Management Training Effectiveness: A Meta-Analysis and Some Critical Needs. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 2008, 18, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Phillips, J.; Durgin, F.H. The underestimation of egocentric distance: Evidence from frontal matching tasks. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.F.; Adkins, O.C.; Pedersen, L.E.; Reyes, C.M.; Wulff, R.A.; Tungate, A. The visual perception of exocentric distance in outdoor settings. Vis. Res. 2015, 117, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, I.T.; Kölsch, F.M.; Konrad, R. Egocentric distance perception: A comparative study investigating differences between real and virtual environments. Perception 2020, 49, 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.F.; Lewis, J.L.; Ramirez, A.B.; Bryant, E.N.; Adcock, P.; Peterson, R.D. The visual perception of long outdoor distances. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbers, T.; Hegarty, M. What determines our navigational abilities? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, S.O.; Hecht, H. Distance estimation in vista space. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2009, 71, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, D.A.; Wallin, C.P.; Philbeck, J.W. Gaze direction and the extraction of egocentric distance. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2014, 76, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Norman, J.F.; Crabtree, C.E.; Clayton, A.M.; Norman, H.F. The perception of distances and spatial relationships in natural outdoor environments. Perception 2005, 34, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Da Silva, J.A.; Philbeck, J.W.; Fukusima, S.S. Visual Perception of Location and Distance. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1996, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, A.; Huang, X.; Voyer, D.; Newcombe, N. A meta-analysis of sex differences in human navigation skills. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2019, 26, 1503–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Click, S.M.; Mohebbi, M.; Steiner, R.; Sisopiku, V.P.; Hadi, M.; Michalaka, D.; Sherif, M.; Martin, J.B.; Griffith, J. Framework for the Development of a Diverse Transportation Workforce in the Southeast Region. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flin, R.; O’Connor, P.; Crichton, M. Safety at the Sharp End: A Guide to Non-Technical Skills; Ashgate: North East Derbyshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Cummings, M.L.; Welton, B. Assessing the impact of autonomy and overconfidence in UAV first-person view training. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 98, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauscher, F.; Shaw, G.; Ky, C. Music and spatial task performance. Nature 1993, 365, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Richardson, S.; Joiner, K.; Wild, G. Aiding Depth Perception in Initial Drone Training: Evidence from Camera-Assisted Distance Estimation. Technologies 2025, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhothali, G.T.; Mavondo, F.T.; Alyoubi, B.A.; Algethami, H. Consumer Acceptance of Drones for Last-Mile Delivery in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, E.; Cano, A.; Deransy, R.; Tres, S.; Barrado, C. Implementing mitigations for improving societal acceptance of urban air mobility. Drones 2022, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, G. Urban Aviation: The Future Aerospace Transportation System for Intercity and Intracity Mobility. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavoukian, A. Privacy and Drones: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tubis, A.A.; Poturaj, H.; Dereń, K.; Żurek, A. Risks of drone use in light of literature studies. Sensors 2024, 24, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.; Dwivedi, S.; Karthikeyan, R.; Abujelala, M.; Kang, J.; Ye, Y.; Du, E.; Mehta, R.K. Identifying Early Predictors of Learning in VR-based Drone Training. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2022, 66, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koritarov, T. Advancing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Pilots Training: Interactive Technologies and Gamified Learning for Enhanced Skills Acquisition. Nor. J. Dev. Int. Sci. 2024, 144, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Fernando, X. Simultaneous localization and mapping (slam) and data fusion in unmanned aerial vehicles: Recent advances and challenges. Drones 2022, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Vazquez, J.; Prieto-Centeno, I.; Fernandez-Cortizas, M.; Perez-Saura, D.; Molina, M.; Campoy, P. Real-time object detection for autonomous solar farm inspection via UAVs. Sensors 2024, 24, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Vision-based navigation techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: Review and challenges. Drones 2023, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Allen, M.; Henson, P.; Gao, X.; Malik, H.; Zhu, P. Enhancing Drone Navigation and Control: Gesture-Based Piloting, Obstacle Avoidance, and 3D Trajectory Mapping. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroftei, D.; De Cubber, G.; Lo Bue, S.; De Smet, H. Quantitative Assessment of Drone Pilot Performance. Drones 2024, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hubbard, S. An Examination of UAS Incidents: Characteristics and Safety Considerations. Drones 2025, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Wang, X. Enhancing drone operator competency within the construction industry: Assessing training needs and roadmap for skill development. Buildings 2024, 14, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.M.W.; Yang, K.K. An exploratory study on the effects of human, technical and operating factors on aviation safety. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2018, 11, 595–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Schadow, J.; Eißfeldt, H.; Pecena, Y. Insights on remote pilot competences and training needs of civil drone pilots. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.; Loffi, J.M.; Ison, A.G.; Courtney, R.M. Evaluating Methods of FAA Regulatory Compliance for Educational Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS). Coll. Aviat. Rev. Int. 2018, 35, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, M.T. Safety and Security of Unmanned Aircraft Systems: Legislating Sociotechnical Change in Civil Aviation; University of Lapland: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2020; Available online: https://research.ulapland.fi/en/publications/safety-and-security-of-unmanned-aircraft-systems-legislating-soci/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- ICAO. Doc 10019 Manual on Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS); ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kunde, S.; Duncan, B. Building User Proficiency in Piloting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (sUAV). In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 7946–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoff, A.; Mattson, P. Standard Test Methods for sUAS—Maneuvering and Payload Functionality. 2019. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2019/08/21/nist-astm-nfpa_standard_test_methods_for_suas_-_maneuvering_and_payload_functionality_overiew_v2019-08-20v2.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wei, X.; Xu, F.; Wu, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, X. Training System and Career Development Plan for UAV Flight Control Talents. Int. J. New Dev. Educ. 2025, 7, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Joiner, K.; Wild, G. Micro-Credentialing and Digital Badges in Developing RPAS Knowledge, Skills, and Other Attributes. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. Important issues in unmanned aerial vehicle user education and training. J. Aviat. 2022, 6, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindley, B.; Phillips, K.; Parnell, K.J.; Cherrett, T.; Scanlan, J.; Plant, K.L. Over a decade of UAV incidents: A human factors analysis of causal factors. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 121, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalilian, F.; Nembhard, D. Biometrically Measured Affect for Screen-Based Drone Pilot Skill Acquisition. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4071–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, D.; Seçkin, A.Ç.; Satı, Z.E. Evaluation of Participant Success in Gamified Drone Training Simulator Using Brain Signals and Key Logs. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, A.; Lynar, T.; Wild, G. The nature and costs of civil aviation flight training safety occurrences. Transp. Eng. 2023, 12, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.; Rice, S.; Lee, S.-A.; Winter, S.R. Unveiling Potential Industry Analytics Provided by Unmanned Aircraft System Remote Identification: A Case Study Using Aeroscope. Drones 2024, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, A.; Lynar, T.; Joiner, K.; Wild, G. Use of Simulation for Pre-Training of Drone Pilots. Drones 2024, 8, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, C.P.; Conway, C.J. Field evaluation of distance-estimation error during wetland-dependent bird surveys. Wildl. Res. 2012, 39, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 10th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cahit, K. Internal validity: A must in research designs. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998 (CASR), Part 101 (Unmanned Aircraft and Rockets) Manual of Standards; Civil Aviation Safety Authority: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlke, G. Ergonomic criterion in the design of roadside information: Letters size methodology. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, A.; Joiner, K.; Lynar, T.; Wild, G. Applications of extended reality in pilot flight simulator training: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2025, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Becoming a Drone Pilot (Part 107). Available online: https://www.faa.gov/uas/commercial_operators/become_a_drone_pilot (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand (CAA). Regulations, Drones (Part 101 and Part 102). Available online: https://www.aviation.govt.nz/drones/regulations/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA). Drone Weight Categories and Requirements (Including Micro and Excluded Category, Accreditation, Remote Pilot Licence and Applicable Operating Conditions). Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/operator-accreditation-certificate/drone-weight-categories-and-requirements (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Open Category, Low Risk, Civil Drones (A1, A2, A3 and Requirements). Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/domains/drones-air-mobility/operating-drone/open-category-low-risk-civil-drones (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.