Abstract

Carbon nanocomposites are essential supports in fuel cell catalysts, ensuring dispersion, anchoring, and reactant access. Here, we demonstrated an in situ synthesis of Pd nanoparticles using electrogenerated hydrophilic carbon (EHC) matrix that acts simultaneously as Pd support and reducing agent. To further enhance oxygen availability, a second EHC form with high oxygen storage capacity was integrated. The resulting material was characterized in terms of its electrochemical behaviour and long-term stability and compared with a nanocomposite without the O2-storing component. A time-dependent decline in electrolyte access to Pd sites was observed in both, but substantially mitigated at long-term by the oxygen-storing component.

1. Introduction

The use of a carbon nanocomposite in fuel cells is essential to ensure that electrocatalysts are well dispersed, anchored to a conductive matrix, and easily accessible to gaseous reactants [1,2]. In this work, a specific strategy was developed to ensure that the catalyst remains firmly attached to the carbon support while maintaining unobstructed access to O2: the metal catalyst was synthesized in situ, with the carbon matrix itself acting as both catalyst support and reducing agent. To test this approach, palladium nanoparticles were selected as a model electrocatalyst for potential use in the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Additionally, a carbon-based nanomaterial with a high oxygen storage capacity was incorporated to enhance O2 availability.

The carbon-based material used was the Electrogenerated Hydrophilic Carbon (EHC), synthesized from a graphite anode under strong polarization conditions [3,4,5]. Among the most noteworthy characteristics of EHC nanomaterials is their redox versatility, which can be modulated by the electrolyte in which they are electrogenerated. In tartaric buffer the EHC material (labelled EHC@T) exhibits strong electron-donating behaviour [1], while in phosphate buffer (labelled EHC@P) it displays weak electron-accepting ability and a high capacity to chemisorb and retain molecular oxygen [4,5].

Hence, to meet the first requirement (effective reducing of the palladium ions and anchoring of the metal catalyst), the EHC@T material was employed, whereas to ensure local O2 supply, the EHC@P was incorporated. This work aims to characterize the resulting Pd nanocomposite, denoted as Pd-EHC@T,P, and compare it with Pd-EHC@T (without EHC@P). Both materials were evaluated in terms of their electrochemical behaviour and long-term stability.

2. Materials and Methods

EHC nanomaterials were prepared according to the procedure that was previously described [3,4,5]. Briefly, the EHC nanomaterial was removed from the anodic compartment of a three-compartment cell containing graphite rods and either a tartaric buffer solution (0.11 M, pH = 4.51) or a phosphate buffer (0.20 M, pH = 5.99) as the electrolyte.

The nanocomposite solutions were prepared by mixing 2 mL of freshly prepared EHC@T (non-dialysed; 1.78 mg/mL) with 40 µL of metal precursor solution (9.45 mM PdCl2) and 2 mL of EHC@P (17.6 ± 2.6 μg C/mL, non-dialysed). For the control, a nanocomposite lacking EHC@P was prepared by replacing the EHC@P solution with deionized water. After preparation, the nanocomposites were immediately subjected to dialysis using membranes with a molecular weight cut-off of 3.5–5 kDa.

For the electrochemical characterization of the nanocomposites, a 0.1 M NaOH solution was used. For the anodic stripping voltammetry, the anodic scan was performed in a 1.0 M HCl solution. The electrochemical cell setup consisted of one-compartment cell with a modified glassy carbon working electrode (GCE) (3 mm in diameter), an Ag/AgCl (in KCl 3 M) reference electrode, and a platinum counter electrode. The GCE were modified by drop-casting with 4 µL of the nanocomposite solutions followed by drying at 30 °C for 40 min and cooling at room temperature under air convection.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anodic Stripping in 0.1 M HCl

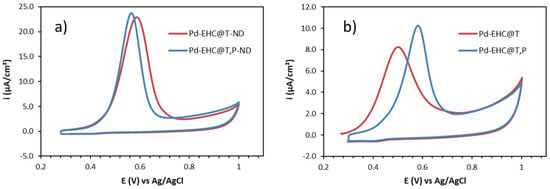

The appearance of an anodic peak during the anodic stripping process confirmed the successful formation of Pd nanoparticles, Figure 1a. By comparing the voltammograms of the nanocomposite solutions before and after the dialysis (Figure 1a and b, respectively), together with the corresponding anodic charges (Table 1), it becomes clear that a substantial amount of Pd is lost during the purification process, particularly in the sample without EHC@P. A noticeable difference is also evident in the stripping peak potentials. The peak potential of Pd-EHC@T is approximately 90 mV less positive than that of Pd-EHC@T,P. This shift indicates that Pd nanoparticles in the Pd-EHC@T,P are more stable than in Pd-EHC@T, displaying a reduced tendency to undergo oxidation.

Figure 1.

(a) Anodic stripping voltammograms in 0.1 M HCl of GCE modified with 4 μL of nanocomposite solutions of Pd-EHC@T-ND and Pd-EHC@T,P-ND (non–dialyzed); (b) Anodic stripping voltammograms in 0.1 M HCl of GCE modified with 4 μL of nanocomposite solutions of Pd-EHC@T and Pd-EHC@T,P (dialyzed). ν = 5 mV s−1.

Table 1.

Pd content in Pd-EHC@T,P and Pd-EHC@T solutions, estimated by anodic stripping.

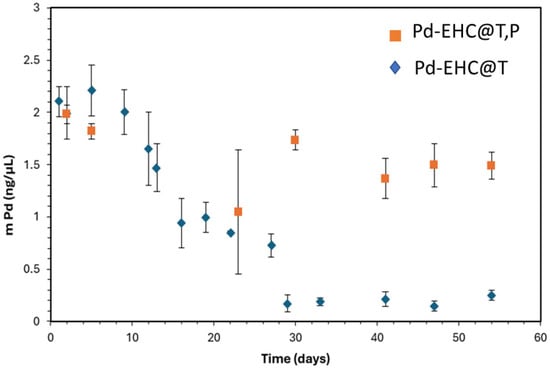

The anodic stripping on the dialysed samples was performed over a 54-day period. In all cases, the electrode was prepared using the same procedure: the EHC solution was first subjected to 30 s of sonication, followed by the drop-casting of 4 µL onto the surface of a glassy carbon electrode. Figure 2 shows the time-dependent evolution of the experimentally determined Pd loading on the GCE modified with Pd-EHC@T,P and Pd-EHC@T samples.

Figure 2.

Pd loading over time on Pd-EHC@T,P and Pd-EHC@T samples. Each measurement is the average of at least three independent measurements made on the same day. The error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean.

Interestingly, a decrease in the amount of Pd by anodic stripping is observed over time, indicating that neither Pd-EHC@T,P nor Pd-EHC@T remains stable in the long term. The decline is significantly greater in the Pd-EHC@T sample, suggesting that EHC@P matrix exerts a stabilizing effect on the Pd nanoparticles over prolonged periods. The apparent decrease in palladium content may not indicate a loss of metal from the nanocomposite, but rather a progressive reduction in the fraction that remains electrochemically accessible.

3.2. Cyclic Voltammetry in 0.1 M NaOH

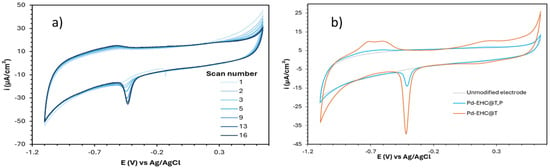

To evaluate the electrolyte accessibility to the Pd surface sites, the voltammograms of Pd-EHC@T,P and Pd-EHC@T having approximately the same metal loading, were recorded in 0.1 M NaOH after electrode activation (i.e., repeated cycling until characteristic peaks of Pd became stable), Figure 3a,b.

Figure 3.

(a) Electrode activation of the GCE modified with Pd-EHC@T,P; ν = 200 mV s−1. (b) Cyclic voltammograms of Pd-EHC@T,P and Pd-EHC@T after electrode activation; ν = 50 mV s−1.

The peaks corresponding to Pd oxide reduction (≅−0.41 V), Pd oxide formation (0–0.3 V), and hydrogen desorption (−0.8 to −0.5 V) are significantly more pronounced in Pd-EHC@T than in Pd-EHC@T,P, which seems to indicate that the presence of EHC@P in Pd-EHC@T,P hinders electrolyte access to the Pd active sites, thereby compromising its electroactive surface area (EASA).

In conclusion, these results suggest that EHC@P, on the one hand, helps stabilize Pd nanoparticles within the nanocomposite over time, but on the other hand, appears to obstruct electrolyte access to the metal sites. Future studies, including atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), are planned to gain deeper insight into the nanocomposite’s architecture.

Author Contributions

Investigation, I.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O.; writing—review and editing, M.C.O.; supervision, M.C.O.; funding acquisition, M.C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, grant number UIDB/00616/2025, UIDP/00616/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, T.-W.; Kalimuthu, P.; Veerakumar, P.; Lin, K.-C.; Chen, S.-M.; Ramachandran, R.; Mariyappan, V.; Chitra, S. Recent Developments in Carbon-Based Nanocomposites for Fuel Cell Applications: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Santandreau, A.; Kellogg, W.; Gupta, S.; Ogoke, O.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.-L.; Dai, L. Carbon nanocomposite catalysts for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions: From nitrogen doping to transition-metal addition. Nano Energy 2016, 29, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.D.; Ferraria, A.M.; Videira, R.A.; Oliveira, M.C. Advances in the Understanding of the Electron-Donating Properties of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials Electrogenerated from Graphite. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 525, 146071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.D.; Oliveira, M.C. Redox-active water-soluble carbon nanomaterial generated from graphite. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 895, 115505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.D.; Ferraria, A.M.; Botelho Do Rego, A.M.; Viana, A.S.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; Fielding, A.J.; Videira, R.A.; Oliveira, M.C. Structural Effects Induced by Dialysis-Based Purification of Carbon Nanomaterials. Nano Mater. Sci. 2024, 6, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).