Abstract

The extensive use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers has sustained global food production for more than a century but at high environmental and energetic costs. Improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) has therefore become a key objective to maintain productivity while reducing the ecological footprint of agriculture. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the biological foundations of NUE enhancement, focusing on the role of microbial biofertilizers and biostimulants. The main mechanisms through which plant-associated microorganisms contribute to nitrogen acquisition and assimilation are analyzed. In parallel, advances in genomics, biotechnology, and formulation science are highlighted as major drivers for the development of next-generation microbial consortia and bio-based products. Particular attention is given to the current landscape of commercial biofertilizers and biostimulants, summarizing the principal nitrogen-fixing and plant growth-promoting products available on the market and their agronomic performance. Moreover, major implementation challenges are discussed, including formulation stability and variability in field results. Overall, this review provides an integrated perspective on how biological innovations, market evolution, and agronomic optimization can jointly contribute to more sustainable nitrogen management and reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers in modern agriculture.

1. Introduction

The extensive use of synthetic nitrogen (N) fertilizers has been the driving force behind the global agricultural intensification of the last century. To secure crop yields and sustain a rapidly expanding population, the Haber–Bosch process, which was commercialized in the early 20th century, allowed for the large-scale industrial fixation of atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, revolutionizing food production. Approximately half (around 40–50%) of the current world population is sustained by food whose production depends on synthetic nitrogen [1].

Nitrogen is the most common nutrient limiting crop productivity and, after water, represents the second most critical input for plant growth [2]. Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE; the ratio of nitrogen absorbed by plants to the nitrogen applied to crops) remains notably low in most agricultural systems. Cereal crops such as rice, wheat, and maize, which collectively supply the majority of global caloric intake, require high nitrogen inputs to achieve optimal yields [3]. Yet, these systems typically recover less than 50% of applied nitrogen, with the remainder lost through gaseous emissions, leaching, and runoff [4]. There is an urgent need for innovation because such inefficiency has far-reaching consequences, contributing to climate change via nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, to eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems through nitrate leaching, and to soil acidification [5].

The environmental and energetic costs associated with synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are increasingly recognized as unsustainable. A large proportion of applied nitrogen is lost as nitrate, contaminating groundwater and promoting eutrophication of rivers, lakes, and coastal zones [6]. Such nutrient overloads contribute to algal blooms, hypoxic zones, and biodiversity loss in aquatic systems. In parallel, nitrogen fertilizers are a major anthropogenic source of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential nearly 300 times that of carbon dioxide and a significant contributor to stratospheric ozone depletion [7]. Agricultural soils, particularly those managed with intensive fertilizer regimes, account for approximately 60% of global anthropogenic N2O emissions [8]. Moreover, the Haber–Bosch process itself consumes about 2% of global energy output and emits approximately 450 Mt of CO2 annually, further linking fertilizer use to the climate crisis [9]. In addition to its environmental footprint, the production and use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are tightly coupled with the global energy market. Because the Haber–Bosch process depends heavily on natural gas as both a feedstock and an energy source, fluctuations in energy prices directly affect the cost of nitrogen fertilizers. Recent geopolitical tensions and energy crises have caused unprecedented increases in natural gas prices, which in turn have driven fertilizer prices to record highs worldwide [10]. This volatility has placed considerable economic pressure on farmers, particularly in developing regions, and has highlighted the vulnerability of modern food systems to external energy shocks. As a result, the high energy intensity and price dependency of nitrogen fertilizer production further reinforce the need for alternative, low-input biological strategies such as biofertilizers and microbial inoculants, which can provide a more resilient and sustainable basis for nitrogen management in agriculture. These impacts underscore the urgent need for a transition toward more sustainable nitrogen management strategies.

Improving NUE is one of the most promising approaches to reduce fertilizer dependency while maintaining high agricultural productivity. Efforts to achieve this goal include breeding crops with enhanced nitrogen uptake and assimilation capacities, optimizing agronomic practices such as precision fertilization, and developing biological alternatives that harness plant–microbe interactions [11]. In this context, microbial inoculants and biofertilizers have emerged as compelling candidates to complement or partially replace synthetic inputs. These biological approaches offer multiple mechanisms to improve NUE: enhancing root architecture, promoting symbiotic or associative nitrogen fixation, modulating phytohormone signalling, and facilitating nutrient mobilization in the rhizosphere [12,13].

The rise in microbial inoculants and biofertilizer innovations has been accelerated by advances in microbiome research, genomics, and synthetic biology. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), diazotrophic bacteria, and engineered microbial consortia are increasingly investigated not only for their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen but also for their roles in regulating stress tolerance and improving nutrient uptake efficiency [14]. Furthermore, mycorrhizal fungi and endophytes contribute to enhanced plant performance under low-input conditions, underscoring the potential of microbial solutions to mitigate dependence on synthetic fertilizers [15]. The commercialization of microbial inoculants has expanded rapidly in recent years, with several biofertilizer products already available in agricultural markets worldwide [16]. Nevertheless, key challenges persist in ensuring consistent field performance, optimizing carrier formulations, and effectively integrating biological solutions into existing fertilization systems.

In parallel with microbial inoculants, biostimulants have gained increasing attention as complementary tools to enhance NUE and overall nutrient performance in crops. Biostimulants comprise a diverse group of substances and microorganisms (including humic and fulvic acids, protein hydrolysates, seaweed and algal extracts, microbial metabolites, and signaling molecules) that act on plant physiology through non-nutritional pathways [17]. Their application can improve nitrogen uptake, assimilation, and remobilization by modulating root growth, enhancing nitrate reductase activity, and stimulating the expression of genes related to nitrogen metabolism. Recent studies have demonstrated that combining biostimulants with reduced nitrogen fertilization regimes can maintain or even improve yields while lowering N losses [18]. Furthermore, biostimulants often exhibit synergistic effects with microbial biofertilizers, creating integrated formulations that promote both microbial activity and plant responsiveness to nitrogen. This integrated biotechnological approach offers a promising strategy to increase NUE in sustainable cropping systems, particularly under conditions of abiotic stress or limited fertilizer availability [19].

The aim of this review is to synthesize current understanding of the mechanisms underlying NUE enhancement, with particular focus on microbial inoculants and biofertilizer-based strategies. We highlight key field applications, evaluate their agronomic and ecological impacts, and identify critical knowledge gaps that limit large-scale adoption. In addition, we present an overview of current market trends and industrial developments in microbial technologies aimed at improving nutrient use efficiency, emphasizing the rapid expansion of nitrogen-fixing and plant growth-promoting microbial products within the global biofertilizer sector. Finally, we outline future research priorities required to translate microbial innovations into scalable, sustainable solutions capable of reshaping nitrogen management in modern agriculture.

2. Agrotechnical Methods for Increasing the Efficiency of Fertilizer Nitrogen Use

Different agronomic practices can be adopted to optimize fertilizer use and, consequently, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). These practices combine soil, crop and nutrient management to reduce N losses and improve plant N uptake. Key strategies include:

- Adoption of precision agriculture tools. Remote sensing, soil and crop sensors, and variable-rate technology allow site-specific adjustment of N rates according to spatial variability and temporal changes in crop N status. Proximal and remote sensing of canopy reflectance or chlorophyll (e.g., SPAD readings, multispectral indices) can be used to detect N deficiencies early and refine in-season N recommendations [20]. This reduces the common tendency to apply uniform and often excessive N rates as yield “insurance” and thus contributes to higher NUE and lower environmental losses [21].

- Optimization of application timing. Splitting N applications and targeting critical phenological stages improves synchrony between N supply and crop demand [22]. By postponing part of the N dose to periods of rapid biomass accumulation, the residence time of mineral N in the soil is reduced, lowering the risk of leaching, volatilization and denitrification. In many cropping systems, such temporal optimization allows total N inputs to be decreased without penalizing yield, and may even improve grain or fruit quality [23].

- Nitrogen rate calculation based on crop demand and nutrient removal. Accurate nitrogen fertilizer rates should be calculated from crop-specific N uptake curves, expected yield, and nutrient removal coefficients, rather than from conventional fixed rates or farmer intuition. Evidence shows that N is often applied in excess due to “insurance” practices rather than actual crop requirements, leading to low recovery efficiency and higher losses. Rigorous N budgeting; including soil residual N, mineralization estimates, and realistic yield goals; is essential for aligning supply with plant demand [24,25].

- Smart fertilizers (controlled-release and inhibitor-enhanced) to reduce volatilization and leaching. Smart N fertilizers, including controlled-release products and urea treated with urease or nitrification inhibitors, improve nitrogen use efficiency by synchronizing N release with crop uptake and reducing loss pathways such as ammonia volatilization and nitrate leaching. Meta-analyses show significant reductions in NH3 losses and NO3− leaching compared with conventional urea, demonstrating their value as an agrotechnical method for efficient N management [26,27].

- Improved fertilizer placement. Incorporating N into the soil or applying it in bands close to the seed or root zone enhances contact between fertilizer granules and active roots [28]. Compared with surface broadcasting, these strategies reduce ammonia volatilization, limit immobilization in surface residues and create localized zones of high N availability that stimulate root proliferation. The integration of banded placement with localized irrigation (e.g., drip lines near N bands) can further improve N recovery by crops [29].

- Enhancement of soil health. Practices such as diversified crop rotations, the use of cover crops and the addition of organic amendments (manure, compost, crop residues) increase soil organic matter and improve soil structure, porosity and water-holding capacity [30]. A more biologically active soil supports microbial processes that regulate N cycling, including mineralization, immobilization and nitrification, thereby enhancing N retention within the system. Over the medium term, these improvements in soil health contribute to more stable yields with lower external N inputs [31].

- Improved water management and fertigation. Precise irrigation scheduling and technologies such as drip irrigation or subsurface drip systems help maintain soil water content within an optimal range, minimizing N leaching and runoff [32]. When combined with fertigation, water and dissolved N fertilizers can be applied frequently in small doses, closely matching crop water and N requirements in space and time. This approach has shown substantial potential to increase NUE, while simultaneously reducing N losses and mitigating environmental impacts. Controlled drainage or deficit-irrigation strategies can also be used to further limit N transport to groundwater and surface waters [33].

- Use of high-efficiency crop varieties. Cultivars selected for improved root architecture, higher N uptake capacity, or enhanced N assimilation and remobilization efficiency can achieve similar or higher yields at reduced N rates. Such genotypes often display greater resilience under sub-optimal N supply and may be particularly effective when combined with precision N management and improved soil and water practices. Integrating genetic and management approaches thus offers a promising pathway to further increase NUE at the cropping-system scale [34].

3. Mechanism for Nitrogen Use Efficient Improvement

Nitrogen use efficiency depends on a complex network of interactions among plant physiology, soil chemistry, and microbial activity. Biofertilizers and microbial inoculants can affect several processes that improve nitrogen uptake and retention, helping boost productivity while reducing environmental losses. Key mechanisms include enhanced nutrient mobilization, regulation of nitrogen cycling, stimulation of root development, and the alleviation of abiotic stress effects on nitrogen metabolism.

3.1. Nutrient Mobilization: Enhanced Solubilization of Bound Nutrients Improves Nitrogen Uptake Synergy

Microbial inoculants enhance nutrient mobilization in the rhizosphere by secreting organic acids, phosphatases, and siderophores that help solubilize nutrients otherwise unavailable to plants, such as phosphorus, potassium, and various micronutrients [35]. Increasing the availability of these co-limiting nutrients creates a synergistic effect that improves nitrogen uptake and assimilation within plant tissues. Phosphorus, for example, is essential for ATP synthesis and nitrate reduction, and its adequate supply supports more efficient nitrogen assimilation pathways [36]. Iron and molybdenum are also critical micronutrients for biological nitrogen reduction, as iron is a structural component of nitrate reductase and nitrogenase, while molybdenum forms part of the nitrogenase active site [37,38]. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, Azospirillum brasilense or Bradyrhizobium japonicum, are known to enhance plant nitrogen uptake by upregulating nitrate reductase activity and improving nitrate reduction pathways, thereby facilitating more efficient nitrogen assimilation in plant tissues [39] (Table 1). By optimizing nutrient stoichiometry within the rhizosphere, these microorganisms indirectly promote greater nitrogen uptake and more efficient utilization for plant growth and yield.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of Action, Key Processes, and Microbial Agents Used to Enhance Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) in Crops. The table summarizes the principal processes, representative microbial groups, and the resulting beneficial effects on plant nitrogen uptake and assimilation.

3.2. Nutrient-Cycling Regulation: Suppressing Nitrification or Denitrification Reduces Nitrogen Losses

Regulation of the nitrogen cycle is paramount for enhancing NUE in agricultural systems and mitigating environmental pollution. Nitrification and denitrification are major loss pathways that convert plant-available nitrogen forms (NH4+, NO3−) into gaseous emissions (N2O, N2). Strategies focused on suppressing these pathways, using synthetic nitrification inhibitors (e.g., DCD) or exploiting Biological Nitrification Inhibition (BNI), are crucial for maintaining N in its less mobile ammonium form (NH4+) within the root zone [40]. For example, biological nitrification inhibition (BNI) is a plant-mediated mechanism, observed in species like Brachiaria humidicola and sorghum, where root exudates inhibit Nitrosomonas spp. activity, thus reducing nitrate leaching and N2O emissions [41]. Inoculants that promote ammonium retention or facilitate its gradual conversion to nitrate help synchronize nitrogen availability with plant demand, minimizing losses through gaseous emissions or runoff [42]. Moreover, microbial consortia that favour anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) or partial nitrification–denitrification pathways have been proposed as innovative bioengineering solutions for sustainable nitrogen management [43].

3.3. Root Growth Stimulation: Larger and Healthier Roots Improve Nutrient Absorption

A strong root system improves the plant’s ability to explore a larger soil volume and access water and nutrients, directly enhancing nitrogen use efficiency. Biofertilizers containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) can stimulate root development via modulation of host hormonal balance, particularly via auxin, cytokinin, and gibberellin pathways [44]. A clear example is Azospirillum brasilense, known for synthesizing indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a hormone that promotes lateral root formation and root hair elongation, thereby increasing the nutrient absorption surface area [45]. Meanwhile, mycorrhizal symbioses expand the root’s reach to immobile nutrients and water, indirectly improving nitrogen uptake efficiency under limiting conditions [46]. A more vigorous root system also strengthens the plant’s resilience to fluctuations in nitrogen availability, supporting steady assimilation and translocation processes during critical growth stages.

3.4. Stress Mitigation: Biofertilizers Help Plants Cope with Abiotic Stress (Salinity, Drought), Maintaining Nitrogen Metabolism Efficiency

Environmental stresses like salinity, drought, and extreme temperatures often interfere with how plants absorb and process nitrogen, mainly by disrupting enzyme activity and transport functions [47]. Biofertilizers help counter these effects by triggering tolerance mechanisms that allow nitrogen metabolism to continue even under stress. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria can boost the activity of antioxidant enzymes, increase the buildup of cell osmolytes (like proline), maintain photosynthetic performance, which keeps key enzymes such as nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase functioning properly and consistent up-regulation of stress-responsive genes [48]. For example, inoculation with PGPR consortia including Bacillus and Pseudomonas species has been shown to mitigate drought-induced declines in photosynthetic rate and biomass, and increase nitrogen accumulation in shoots, relative to uninoculated controls [49]. Likewise, mycorrhizal fungi help plants cope with salinity stress by improving ion balance and water absorption [50]. Altogether, these microbial inoculants act as biostimulants that help plants withstand environmental fluctuations, maintaining nitrogen use efficiency even under challenging conditions.

4. Biological Nitrogen Fixation

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is a fundamental biogeochemical process by which diazotrophic prokaryotes reduce atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3), thereby supplying bioavailable nitrogen to plants [51,52]. The reaction is catalysed by the nitrogenase complex, composed of Fe and MoFe proteins, which mediate the energetically demanding six-electron reduction of N2 [53]. However, the reaction is strongly inhibited by oxygen and requires substantial ATP investment, making BNF both biologically costly and physiologically constrained [54]. Despite these limitations, BNF remains ecologically indispensable, continuously replenishing soil nitrogen pools and supporting the productivity of both natural ecosystems and agricultural systems.

From an agronomic standpoint, BNF reduces reliance on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, lowering input costs and mitigating environmental risks such as nitrate leaching and greenhouse gas emissions [55]. Yet, terrestrial BNF estimates across spatial and temporal scales remain highly uncertain due to methodological constraints and environmental variability [56]. Recent global analyses suggest that BNF in croplands and cultivated pastures accounts for approximately 56 Tg N annually, representing a 64% increase in terrestrial BNF and a 60% increase in total nitrogen inputs compared to pre-industrial levels [57]. Importantly, its benefits extend beyond legumes: fixed nitrogen can support companion species in intercrops (e.g., soybean–wheat) and contribute residual fertility to subsequent rotations [11,58,59].

BNF occurs across three ecological modes [25]. Symbiotic fixation is the most efficient, involving specialized bacteria such as Rhizobium or Bradyrhizobium that form root nodules on legumes and channel fixed nitrogen directly to the host [60] (Table 2). Associative fixation involves diazotrophs like Azospirillum or Herbaspirillum that colonize root surfaces or intercellular spaces of cereals, fixing nitrogen while utilizing host-derived carbon [61]. Free-living fixation occurs in the rhizosphere or bulk soil under microaerobic or anaerobic conditions, where diazotrophs such as Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Burkholderia contribute modest but ecologically significant nitrogen inputs. N-fixing bacteria can be found on the surface of plant leaves (epiphytic), in the rhizosphere (close to the plant roots), or as endophytes inside of the plant tissues [62]. In the following sections, we examine recent advances in BNF research and identify key limitations that constrain its agronomic potential mainly focus on symbiotic and associative nitrogen fixation.

Table 2.

Representative genera for biological nitrogen fixation, ecological adaptations, and agricultural relevance.

4.1. Symbiotic: Rhizobium–Legume Interactions, Bradyrhizobium, Sinorhizobium and Cyanobacteria

4.1.1. Rhizobium–Legume System

Symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) represents a central model for mutualistic plant–microbe interactions and stands as a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture [82,83,84]. In this system, the legume host must tightly regulate nodule development and activity, since nitrogen fixation is highly energy intensive. It consumes large amounts of photosynthate and must therefore be carefully balanced against the plant’s overall carbon and energy budget [85]. The interaction is governed by a sophisticated molecular dialogue. Flavonoids secreted by roots activate rhizobial nod genes via the regulator NodD, triggering the production of Nod factors that initiate root hair curling, infection thread formation, and cortical cell divisions to form the nodule primordium. In some legumes, additional host signalling is modulated by effectors delivered through a type III secretion system [86,87]. In terms of agronomic contribution, faba bean cultivation can introduce approximately 80–200 kg N ha−1 to the soil within a single growing season [88,89,90]. However, the magnitude of fixed nitrogen is strongly influenced by environmental conditions and crop management practices [90].

A defining feature of the rhizobium–legume symbiosis is its specificity [91,92]. Typically, each rhizobial strain is compatible with a narrow set of legumes, and conversely, each legume species selectively recruits rhizobial partners [92,93]. Promiscuous strains such as Sinorhizobium sp. NGR234 can nodulate more than 230 legume species, whereas others, like Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae, are compatible with only a limited subset of pea cultivars. When incompatibility arises, it often results in aborted nodules or structures incapable of fixing nitrogen [94,95].

This specificity carries important agronomic implications. Farmers often inoculate crops such as soybean or peanut with elite rhizobial strains to ensure effective nodulation, particularly in soils where compatible symbionts are absent. Crop rotations with legumes further enrich soil nitrogen for subsequent cereals, frequently contributing tens of kilograms of fixed nitrogen per hectare. However, the success of these practices depends on the precise alignment of host genotype, inoculant strain, and environmental conditions. Soil pH, salinity, temperature, and nutrient availability all influence infection, nodule development, and symbiotic efficiency [96,97,98]. Because legumes satisfy most of their nitrogen needs through SNF, fertilization is generally restricted to small starter doses applied before sowing, which support seedlings until nodulation is established [99]. Taken together, the rhizobium–legume symbiosis exemplifies a highly coordinated and evolutionarily refined mutualism while simultaneously serves as a practical model for sustainable agriculture, thanks to its ability to naturally enhance soil fertility.

4.1.2. Bradyrhizobium–Soybean System

Within the diversity of rhizobia, the genus Bradyrhizobium is notable for its physiological resilience and prominent symbiotic role [100]. A classic example is Bradyrhizobium japonicum (and the closely related B. diazoefficiens), which are the principal symbionts of soybean (Glycine max), one of the world’s most important legume crops [100]. In agricultural practice, soybean seeds are routinely inoculated with Bradyrhizobium strains to ensure effective nodulation and high nitrogen fixation [101,102]. The soybean–Bradyrhizobium symbiosis can fix approximately 300 kg N ha−1 under favourable field conditions [103]. The amount of nitrogen fixed is influenced by several factors, including soil mineral N levels, the genetic compatibility of the symbiotic partners, and the absence of other yield-limiting stresses. The effectiveness of inoculation is further determined by the density and competitiveness of indigenous Bradyrhizobium populations, the nitrogen demand and yield potential of the host plant, and the overall availability of nitrogen in the soil [103]. In addition to soybean, different Bradyrhizobium strains nodulate groundnut (peanut), cowpea, and various tree and shrub [102,104,105,106,107,108].

These bacteria thrive under environmental stresses that limit other rhizobia [109,110]. For instance, in acidic tropical soils (low pH, high aluminum), indigenous Bradyrhizobium outperform introduced rhizobia, nodulating legumes like groundnut more effectively [67,111]. Moreover, inoculation with stress-tolerant Bradyrhizobium can help legume crops withstand drought, as seen in pot experiments where inoculated soybeans had higher nodule function and antioxidant enzyme activity during drought stress [112]. Their adaptations include production of extracellular polysaccharides that protect cells under drought or acidity and the presence of hopanoid lipids that stabilize membra nes [113]. Bradyrhizobium stands out among rhizobia for its versatility, it associates with a wide range of legumes (including major crops), withstands harsh soil conditions (acid, drought, heat) making it a reliable inoculant in challenging environments, and even challenges the canonical rules of nodulation through Nod-independent mechanisms. As climate change and soil degradation intensify, the resilience of Bradyrhizobium symbioses will be increasingly valuable, and lessons learned from their adaptability could inform future efforts to enhance symbiotic efficiency in agriculture.

4.1.3. Sinorhizobium–Medicago System

Sinorhizobium (also known as Ensifer) is another major lineage, best represented by S. meliloti in alfalfa. Sinorhizobium meliloti associated with alfalfa roots can fix between 150 and 350 kg N ha−1 under typical field conditions [114]. In trials combining constant mineral fertilization with NPK and diversified supplementation with Fe and Mo micronutrients, nitrogen fixation levels were reported to reach up to 618 kg N ha−1 [115]. One striking feature of Sinorhizobium is its broad range of compatible hosts across different species [116]. While S. meliloti is relatively specific (effectively nodulating Medicago and a few related genera), other Sinorhizobium species like S. fredii are far more promiscuous [117]. From a comparative genomics viewpoint, Sinorhizobium meliloti has one of the best-characterized pangenomes among rhizobia [82]. Compared with other rhizobia, Sinorhizobium exhibits extensive genetic plasticity. Its genome is multipartite, consisting of a chromosome and large plasmids carrying many symbiotic genes. Core functions are conserved, but accessory plasmid genes vary widely among strains, shaping ecological fitness, stress responses, and host compatibility [118]. This genomic mosaic explains why strains of the same species may differ in nodulation efficiency or competitiveness. For example, some S. meliloti strains possess enhanced systems for iron acquisition or microaerobic respiration, conferring advantages during nodule colonization [82]. Another strain might fix nitrogen more efficiently because it has an enhanced system for microaerobic respiration inside the nodule (like an extra high-affinity cytochrome oxidase). These differences matter for agriculture, as there are variations in symbiotic performance of different rhizobial strains associated with the same host [119]. From an agronomic standpoint, identifying and deploying the most effective strains can significantly enhance yields in forage and grain legumes.

4.1.4. Cyanobacterial Nitrogen Fixation in Rice Systems

Symbiotic nitrogen fixation is not confined to legume roots; certain non-leguminous plants have forged mutualisms with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (often of the genus Nostoc or closely related genera). Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic, often multicellular (filamentous) bacteria capable of fixing N2, and they represent some of Earth’s oldest and most self-reliant organisms [120]. These cyanobacteria frequently differentiate heterocysts-specialized, thick-walled cells that create a micro-oxic environment for nitrogenase activity-allowing N2 fixation to occur alongside oxygenic photosynthesis [121]. In paddy-field systems, cyanobacteria are reported to fix about 20–30 kg N ha−1 yr−1 as part of the biological nitrogen fixation pool [122,123]. Molecular and phylogenomic studies further show that Nostoc lineages display broad host competence across bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, suggesting conserved symbiotic programs among distant plant taxa [124,125]. Unlike legume–rhizobium nodules, plant–cyanobacteria symbioses do not typically involve the formation of a new organ analogous to a nodule (with one notable exception in Gunnera). In Gunnera, Nostoc colonizes stem glands and intracellular channels forming a highly integrated association; in cycads, cyanobacteria inhabit specialized coralloid roots; and in bryophytes such as Anthoceros, colonization occurs in mucilage cavities [126,127]. These associations often take place in pre-existing plant structures (like specialized cavities or glands), and the symbiont often remains less integrated than rhizobia in nodules. Nonetheless, they are true symbioses, the cyanobacteria provide fixed nitrogen to the plant, and the plant offers habitat and nutrients to the cyanobacteria. Three well-known examples of such symbioses are those involving Azolla (water fern), Gunnera (tropical herbaceous plant), and certain bryophytes (primitive plants like hornworts and mosses), as well as the symbiosis in cycads (ancient gymnosperm trees) [128]. Recent reviews reaffirm these systems: (i) Azolla-Anabaena azollae fixes nitrogen at high rates and contributes to sustainable rice systems; (ii) Gunnera-Nostoc punctiforme is a rare angiosperm intracellular symbiosis; (iii) bryophytes and (iv) cycads harbor cyanobionts with a conserved Nostocales core that coevolved with their hosts [124,126,129]. Metagenomic surveys also reveal that coralloid roots of cycads host additional microbial partners that influence cyanobacterial performance and nitrogen fixation efficiency [129].

Cyanobacteria contribute fixed nitrogen while often continuing photosynthesis, providing both carbon and nitrogen benefits to their hosts. Thus, they have even been proposed as biofertilizer strategies in modern agriculture, inoculating crop fields or orchards with free-living cyanobacteria that could colonize soil or plant surfaces and fix nitrogen in situ [120]. Cyanobacteria-based biofertilization provides a promising sustainable alternative for low-input farming, especially in flooded crops where cyanobacteria naturally thrive. From an agronomic point of view, free-living or associative cyanobacteria such as Nostoc, Anabaena, Tolypothrix, Calothrix, and even Arthrospira are being developed as biofertilizers. In rice fields, cyanobacterial inoculation or Azolla co-cultivation enhances soil nitrogen availability and improves yields (up to 20% in some trials); in wheat, Anabaena cylindrica-based formulations increased biomass and soil fertility under open-field conditions [130,131]. Beyond flooded systems, cyanobacteria are being applied for soil restoration and carbon sequestration in degraded drylands [120].

Recent advances in formulation technology including alginate-based carriers, polymer encapsulation, and biofilm matrices have improved cell viability, stress tolerance (UV, desiccation), and persistence in the rhizosphere. For instance, alginate composites can act as water-retaining carriers that prolong cyanobacterial survival during establishment in soil [132,133].

Cyanobacteria-based biofertilization provides a promising sustainable alternative for low-input farming, especially in flooded crops where cyanobacteria naturally thrive. However, challenges remain in open-field applications, such as competition with other microbes and maintaining cyanobacterial activity in target areas. Current research highlights that the main bottlenecks are carrier shelf-life, production cost, photodamage, and strain specific adaptation issues that can be addressed using omics-based selection and synthetic biology approaches to design next generation cyanobacterial inoculants [132,134]. Despite these limitations, the potential is considerable: cyanobacterial biofertilizers can enhance soil organic carbon and nitrogen levels while reducing reliance on chemical nitrogen fertilizers.

4.2. Associative: Azospirillum, Herbaspirillum, Methylobacterium, Bacillus

Unlike symbiotic nitrogen fixers or strictly free-living soil diazotrophs, associative nitrogen-fixing bacteria establish loose, non-nodulating relationships with plants [135]. These microorganisms colonize the rhizosphere or internal plant tissues (endosphere) of various crops, particularly grasses and non-legumes, without forming specialized nodules. Although their contributions to plant nitrogen supply are generally smaller and less direct than those of rhizobial symbioses, associative diazotrophs can nevertheless provide meaningful nitrogen inputs under low-fertility conditions, offering a distinct ecological advantage [135]. Among these, Azospirillum spp. are the most extensively studied, typically contributing 20–40 kg N ha−1 in under favourable conditions [136], with values decreasing to 2–3 kg N ha−1 in suboptimal environments [137]. Comparable contributions (≈40 kg N ha−1) have been reported for Herbaspirillum in sugarcane [138]. Other diazotrophic genera, such as Methylobacterium and Bacillus, generally contribute more modest nitrogen inputs, although it remains difficult to accurately estimate their field-level fixation rates due to the limited number of agronomic studies and the predominance of laboratory-based evaluations. Although the fixed nitrogen supplied by these associative microorganisms is lower than that produced in classical symbioses, their agronomic importance extends well beyond N2 fixation. Many associative diazotrophs enhance nitrogen uptake efficiency, stimulate root system development, and improve plant tolerance to abiotic stress. Indeed, numerous studies indicate that their plant growth-promoting effects are often mediated by mechanisms other than atmospheric nitrogen fixation—such as phytohormone production or nutrient solubilization—as discussed in Section 1 of this review [139,140]. Recent evaluations indicate that evidence for substantial atmospheric N2 fixation by most free-living or endophytic diazotrophs remains limited [141]. To rigorously confirm associative N2 fixation, several criteria must be met: (i) the inoculant bacterium carries a complete set of nif genes required for nitrogenase synthesis; (ii) nitrogenase activity is protected from oxygen inactivation; (iii) the bacterium successfully colonizes plant tissues; (iv) increased respiration linked to N2 fixation is detectable in colonized tissues; (v) plants inoculated and grown under nitrogen-free conditions exhibit enhanced growth and nitrogen accumulation; and (vi) multiple independent methods confirm significant inputs of fixed N2 under field conditions [141].

4.2.1. Azospirillum: A Model Associative Diazotroph

Azospirillum spp. are Gram-negative, motile bacteria that serve as well-established associative nitrogen fixers in the rhizosphere of cereals and grasses. Although they carry functional nitrogenase enzymes and activate nif gene expression during root colonization, their direct nitrogen contribution to host plants is generally modest compared with that of symbiotic partners. Long-term inoculation studies in maize, wheat, rice, and sorghum consistently report growth and yield enhancement, but these effects are largely attributed to additional plant growth-promoting mechanisms in addition to nitrogen transfer [142]. A defining feature of Azospirillum–plant interactions is the stimulation of root system development through phytohormone production [78]. Some strains also generate nitric oxide signals that enhance root branching or produce ACC deaminase, which lowers stress-induced ethylene levels and further encourages root elongation [78]. Collectively, these responses increase root surface area and thereby improve nutrient and water uptake, indirectly enhancing nitrogen nutrition. Recent evidence shows that seed inoculation with A. brasilense Ab-V5 improves maize growth under nitrogen-limiting conditions by modulating biochemical and physiological pathways linked to nutrient assimilation [143]. Similarly, potato inoculation with nitrogen-fixing Azospirillum strains has been associated with increased plant nitrogen content, reflecting enhanced nitrogen uptake and utilization efficiency [144]. These effects are consistent with the modulation of transcriptional responses associated with the uptake, assimilation, and efficient use of nitrogen [145].

From an agronomic perspective, Azospirillum has been successfully developed as a commercial inoculant in multiple countries. Field trials demonstrate that seed or soil inoculation can boost yields of cereals, particularly under low-nitrogen input systems [146,147]. However, outcomes are variable: responses depend on soil fertility, crop genotype, and environmental conditions. To enhance reliability and consistency, current strategies include co-inoculation with other PGPR or mycorrhizal fungi to synergize growth promotion and nitrogen delivery in the field.

4.2.2. Herbaspirillum: Endophytic Diazotrophs in Grasses

Herbaspirillum spp. are another important group of associative nitrogen fixers, best known for their endophytic colonization of tropical grasses. First identified in sugarcane, Herbaspirillum (e.g., H. seropedicae, H. rubrisubalbicans) colonizes roots, stems, and leaves of crops such as sugarcane, rice, maize, and sorghum [148]. Entry into the plant occurs through cracks at emerging lateral roots or other openings, after which the bacteria spread intercellularly within the cortex and vascular tissues [148]. Carrying nif genes, Herbaspirillum actively fixes nitrogen inside host plants. Along with Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus, it has been implicated as a major contributor to the high levels of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) observed in certain Brazilian sugarcane varieties that require little or no fertilizer [79]. In maize field trials, inoculation with H. seropedicae has provided substantial nitrogen inputs. For instance, experimental evaluations have shown that a peat-based inoculant supplied approximately 30% of the nitrogen requirement in inoculated maize [149]. Similarly, inoculation of the rice rhizosphere at the seedling stage with a Herbaspirillum strain significantly increased nitrate nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen, and available phosphorus in the rhizosphere compared with control [150]. These results demonstrate tangible nitrogen savings and yield maintenance through endophytic BNF. Beyond nitrogen fixation, Herbaspirillum promotes plant growth through multiple mechanisms. It produces phytohormones that stimulate root elongation and enhance nutrient uptake, like Azospirillum [151,152]. One challenge for its use as a biofertilizer lies in formulation and shelf life: as a non-spore-forming Gram-negative bacterium, Herbaspirillum is typically delivered fresh, and maintaining viability during storage and under field conditions remains a focus of ongoing research. Nevertheless, field evaluations with Herbaspirillum inoculants have shown promising results [149], underscoring their potential role in sustainable agriculture.

4.2.3. Methylobacterium: Pink Phyllospheric Partners

Methylobacterium spp., often recognized by their pink pigmentation, are ubiquitous facultative methylotrophs that live on plant surfaces and as endophytes. While known mostly for consuming methanol from plant exudates, certain Methylobacterium are also diazotrophic and plant-growth-promoting [153]. They colonize a broad range of hosts (from cereals to trees) and are especially common in the phyllosphere and seeds [154]. Notably, Methylobacterium is capable of fixing nitrogen in the aerial tissues of plants. Studies of strains isolated from Jatropha leaves have revealed that approximately 30% of the leaf endophytic community consists of nifH-positive diazotrophs. One such strain, Methylobacterium L2-4, has been shown to actively fix N2 both on the leaf surface and within leaf tissues, resulting in improved Jatropha growth and seed yield under low-nitrogen conditions [154]. This was the first report of significant bacterial N-fixation in the phyllosphere, suggesting these microbes may help plants in nutrient-poor environments by providing a small but critical trickle of nitrogen. In addition to N-fixation, Methylobacterium spp. exert various plant growth-promoting effects. They are known to produce cytokinins and auxins, and to modulate ethylene levels via ACC deaminase, thereby influencing plant development [155]. In field applications, Methylobacterium has gained attention in recent years: foliar sprays of N-fixing Methylobacterium are being tested to enhance crop nitrogen use efficiency [156]. Furthermore, a strain Methylobacterium sp. 2A was found to alleviate salt stress and even suppress fungal disease in potato, demonstrating bioprotective roles beyond nutrition [157]. While not yet as common in commercial biofertilizers, Methylobacterium represents a versatile genus whose multi-faceted plant interactions (from nitrogen fixation to stress mitigation) could be harnessed in future crop inoculant formulations.

4.2.4. Bacillus: Versatile PGPR with Nitrogen-Fixing Ability

Species of Bacillus (including related genera such as Paenibacillus) are among the most widely used PGPR in agriculture, valued for their durable spores and broad-spectrum benefits. Traditionally, Bacillus spp. have been recognized for traits such as phosphate solubilization, antibiotic production against pathogens, and the induction of systemic resistance in plants [158]. However, many Bacillus and Paenibacillus strains also carry nitrogenase genes (nif) and are capable of associative nitrogen fixation [81,159]. In addition to nitrogen fixation, Bacillus species promote plant growth through the production of phytohormones [160,161]. Moreover, numerous Bacillus spp. produce ACC deaminase, which helps plants tolerate drought and salinity by reducing stress-related ethylene levels [162]. From an agronomic perspective, Bacillus-based biofertilizers and biopesticides are already widely used. Their ability to form stress-resistant spores gives them an advantage in formulation and storage compared with non-sporulating PGPR. Field trials often report improved root and shoot growth, particularly under stress; for example, B. amyloliquefaciens strain EB2003A enhanced corn and soybean germination under salinity stress [163,164]. Key challenges include ensuring effective root colonization and selecting strains suited to specific crops and soils. Nonetheless, thanks to their combined benefits (modest N2 fixation, hormone production, nutrient solubilization, and stress protection) Bacillus and Paenibacillus remain central to the development of next-generation biofertilizers.

5. Recent Advances in Biofertilizer Development

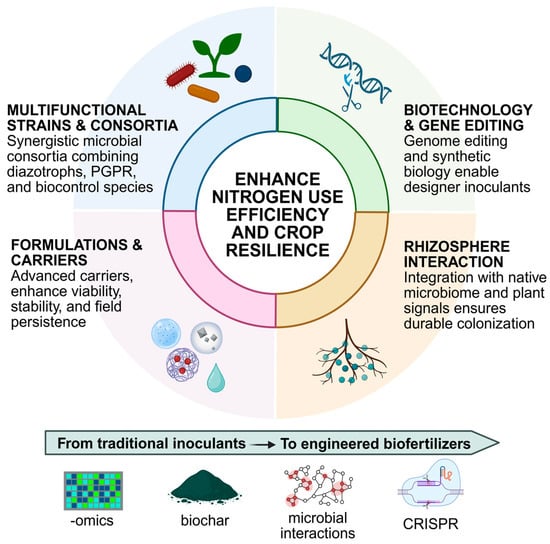

The last decade has witnessed substantial progress in the design and application of biofertilizers aimed at improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). Traditional inoculants based on single microbial strains are progressively being complemented, or even replaced, by more sophisticated approaches that combine microbial diversity, innovative carriers, and biotechnology-driven improvements (Figure 1). These innovations respond to the urgent need for biofertilizers that remain effective across diverse soils, climates, and crop systems.

Figure 1.

Overview of principal biostimulant trends for improving nutrient use efficiency. Current biostimulant strategies aim to enhance nitrogen nutrition in agriculture through multiple complementary approaches. These include the design of microbial consortia or strain “cocktails” with diverse modes of action, specifically tailored to target crops to improve colonization and effectiveness. Significant efforts are also directed toward the optimization of product formulations to extend shelf life and ensure accurate delivery of active ingredients to plants. In addition, advances in rhizosphere ecology, biotechnology, and gene editing are being leveraged to increase the efficiency and consistency of biostimulant performance under field conditions (Created in BioRender. Diaz Santos, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/3fnfod6).

The successful integration of microbial biofertilizers to enhance Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) hinges entirely on the precise understanding of their underlying mechanisms of action. Without clear mechanistic knowledge, the efficacy of biofertilizer application becomes highly variable, failing to account for critical environmental factors like native soil microbial competition or specific crop physiological needs [17]. Therefore, elucidating the specific pathways involved is crucial for moving away from generic inoculation practices towards a targeted, strain-specific strategy that ensures consistent field results and optimizes the contribution of microbial inputs to sustainable nitrogen management.

5.1. Multifunctional Strains and Microbial Consortia

Beyond individual strains, there is a clear shift from single-strain inoculants to multi-strain consortia. Research shows that microbial consortia (combinations of complementary bacteria) often outperform single strains in promoting plant growth [164,165,166]. Recent efforts have focused on the identification of strains capable of performing multiple functions beyond nitrogen fixation. Certain Azospirillum, Burkholderia, and Pseudomonas isolates not only fix nitrogen but also produce phytohormones, solubilize phosphorus, and confer tolerance to abiotic stress. The integration of such strains into microbial consortia allows synergistic effects, where complementary species sustain more stable colonization and broaden the range of beneficial functions [164,166]. Co-inoculation strategies, for example, combining Rhizobium with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), have shown to enhance nodulation efficiency and nutrient uptake simultaneously [166]. These findings align with the emerging consensus that multispecies biofertilizers are often more robust and effective under field conditions than single-strain products [165]. However, designing optimal consortia is complex, strains must be compatible and not antagonistic. Recent reviews emphasize the importance of understanding intermicrobial interactions to intentionally design synthetic communities with predictable functions [166]. Advanced strategies are being explored to model and intentionally assemble consortia that deliver multiple plant benefits in tandem. Overall, harnessing multifunctional PGPB and well-coordinated consortia represents a major advance in biofertilizer development, enabling more comprehensive improvements in soil fertility and crop resilience.

5.2. Formulation and Carriers

Innovations in biofertilizer formulation technology are improving the viability, shelf stability, and field performance of bacterial inoculants. Traditional carrier-based formulations used peat as a solid carrier for inoculant microbes due to its large surface area, high water-holding capacity, and nutrient content [167]. While peat-based powder inoculants can effectively deliver bacteria (e.g., coated onto seeds), they typically have limited shelf life (6–12 months) and variable quality [168]. Recent efforts focus on alternative carriers and formulation types that prolong microbial survival. Liquid biofertilizers have gained popularity by suspending bacteria in nutrient-rich broth or oil-based solutions with added protective agents [168]. Unlike dried peat powders, liquid formulations allow inclusion of growth stimulants and osmoprotectants (glycerol, sugars, etc.) to maintain high cell viability. Understanding the complex interactions between carrier materials and microbial communities is essential for optimizing nutrient cycling in agricultural systems. With proper storage (cool, dark conditions), commercial liquid inoculants can achieve shelf lives of 9–13 months [169].

Another major advance is the use of polymeric and novel carriers to protect bacteria from desiccation and stress. Encapsulation of plant growth promoter in natural polymers like alginate, starch, or chitosan can create gel beads that shelter cells and release them slowly into soil [170]. Alginate is a biocompatible, non-toxic matrix that maintains moisture around the microbes and buffers against harsh soil conditions, thereby increasing desiccation resistance and longevity [171]. Additives like skim milk powder, trehalose, and glycerol are often incorporated into capsules to further improve stability by serving as nutrients or stress protectants [172]. Such nanocarrier-enhanced formulations illustrate how coupling beneficial microbes with nanomaterials can improve inoculant efficacy. Biochar-based carriers have also emerged as a promising solid matrix; biochar’s porous structure provides microsites for microbial attachment and shields cells from predators and drying [173]. Studies indicate biochar inoculant formulations can extend bacterial survival in soil and even contribute additional soil benefits (e.g., improving nutrient retention).

Furthermore, advanced drying techniques are used to prepare dry biofertilizer formulations without compromising viability. Technologies like air-drying, freeze-drying and spray-drying produce powdered inoculants that are easier to handle and apply. To counter viability losses during drying, cryo- or lyoprotectants (e.g., sucrose, mannitol, milk powder) are added to preserve cell membranes [174,175]. Taken together, these formulation advances—whether through optimized liquids, polymer encapsulation, nanoparticle additives, or improved drying methods—have greatly increased the shelf life and field reliability of bacterial biofertilizers. By providing a protective microenvironment, modern carriers ensure more bacteria survive storage and reach plant roots alive, ultimately translating to more consistent plant growth responses in the field.

5.3. Interaction with the Soil and Rhizosphere Microbiota

Understanding the dynamics between introduced inoculants and native microbial communities is central to the success of biofertilizers. Recent research has shown that biofertilizers can modulate rhizosphere microbial networks, either by stimulating beneficial groups or by altering competitive relationships that determine nutrient cycling [176,177]. Some formulations include prebiotic components (such as organic acids or polysaccharides) that selectively enhance the growth of diazotrophs and other beneficial microbes, thereby reinforcing the long-term effectiveness of the inoculant [178]. Biofilm-producing bacteria can anchor to roots and survive fluctuations in moisture or nutrients, thereby outcompeting less resilient microbes [179,180]. Formulation approaches described earlier (e.g., encapsulation in protective polymers or biochar) also enhance persistence by shielding inoculants from desiccation.

The dynamic with the plant itself is equally critical. Plants actively shape their rhizosphere microbiome through root exudation of sugars, amino acids, and other metabolites that selectively recruit beneficial microorganisms [181]. Introduced biofertilizer bacteria must be capable of utilizing these exudates and responding to plant signals to effectively colonize the root zone. Strains that are well-adapted to a crop’s exudate profile (sometimes achieved by isolating PGPB from the same crop’s rhizosphere) tend to establish more successfully. In turn, a successful inoculant can modulate the native community: studies show that adding beneficial Bacillus or Trichoderma via biofertilizer can enrich those genera in the soil and even increase the abundance of other advantageous taxa while suppressing some pathogens [176]. Biofertilizer application tends to enhance soil microbial network complexity and stability, meaning beneficial organisms form more robust communities that resist pathogen invasion [176]. In essence, a well-designed bacterial inoculant does not act in isolation but triggers a cascade of shifts in the soil microbiome that improve overall soil health (e.g., boosting nutrient-cycling microbes or antagonists of plant diseases).

Nevertheless, ensuring that inoculated strains persist long enough to exert their effects remains a challenge. Approaches to improve persistence include repeated or high-dose applications, co-inoculating supportive companion microbes, and even breeding plants (or engineering root exudates) that favor the introduced bacteria (“rhizosphere engineering”) [168,182]. Some biofertilizer strategies now consider native microbiome compatibility, choosing inoculant strains that complement rather than disrupt indigenous communities [168]. There is also interest in monitoring introduced strains after application using molecular tools to understand their colonization patterns and interactions. Overall, current research recognizes that a biofertilizer’s performance hinges on the complex soil–microbe–plant interplay. By accounting for factors like competition with native biota, root signaling, and soil physico-chemical conditions, scientists are developing methods to improve colonization (for example, seed coatings that adhere bacteria to roots, or inoculating at a plant growth stage when niches are available). A successful bacterial biofertilizer will integrate into the resident soil microbiome in a way that reinforces beneficial processes without upsetting the ecological balance. The goal is a persistent, self-sustaining population of the introduced microbes that continues to promote plant growth long after initial inoculation.

5.4. Biotechnology and Gene Editing

Recent advances in biotechnology are revolutionizing bacterial biofertilizer development by enabling precise manipulation of plant growth-promoting bacteria. Omics-guided approaches allow researchers to identify genetic determinants of nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and stress tolerance, while CRISPR-Cas tools can enhance or delete specific traits such as ACC deaminase production or competing metabolic pathways. Recent studies have successfully applied CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) systems in the model diazotroph Azotobacter vinelandii, enabling targeted modulation of regulatory genes controlling nitrogenase expression and demonstrating precise control of nitrogen fixation under variable environmental conditions [183]. At the same time, omics-driven analyses of PGPR have revealed key gene clusters related to nitrogen fixation, siderophore production, phytohormone biosynthesis, and oxidative stress protection, which are now being used to guide genome editing and synthetic pathway reconstruction for enhanced field performance [184,185]. Synthetic biology complements this by introducing modular toolkits for constructing or refactoring biosynthetic pathways, as demonstrated in nitrogen-fixing genera like Azotobacter, Pseudomonas stutzeri, and Klebsiella, where inducible nitrogenase circuits and heterologous metabolite pathways have been engineered [185]. In a recent example, a synthetic biology toolkit was established for nitrogen-fixing bacteria (Azotobacter, Pseudomonas stutzeri, Klebsiella), enabling the introduction of regulatory circuits for inducible nitrogenase activity [185]. These innovations illustrate the potential to create “designer” strains optimized for nitrogen fixation, stress resilience, and compatibility with diverse crops. Although regulatory, environmental and safety challenges remain, the integration of multi-omics data, genome editing, and synthetic circuits provides a powerful toolkit for tailoring next-generation biofertilizers with enhanced agronomic performance.

6. Bottlenecks and Challenges

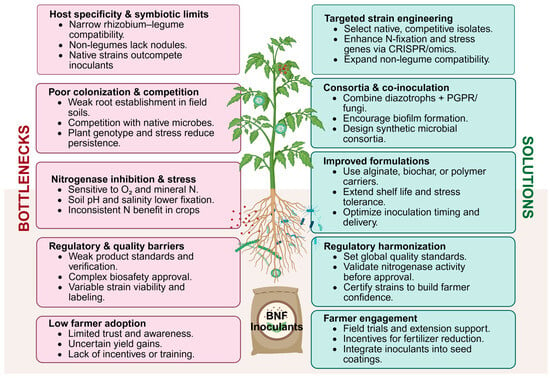

Biological nitrogen fixation offers a sustainable alternative by supplying crops with bioavailable nitrogen naturally. In theory, effective inoculants could reduce fertilizer needs, lowering input costs and mitigating pollution. In practice, however, translating BNF potential into consistent field gains has proven challenging. It is important then, to analyse the major biological, environmental, technological, and regulatory bottlenecks limiting the success of N-fixing bacterial inoculants and biostimulants under field conditions and discusses evidence-based solutions to overcome these hurdles. By addressing these challenges, from strain-host compatibility to formulation and farmer adoption, we can enhance the contribution of microbial BNF to crop NUE and sustainable agriculture (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main gaps and practical solutions for the development of biostimulants focused on improving nitrogen use efficiency in agriculture. The left panel highlights current limitations in large-scale development, including host specificity, regulatory and quality barriers, and low farmer adoption. The right panel presents practical guidelines for product selection and deployment, emphasizing targeted strain development, regulatory harmonization, and farmer engagement. Together, these perspectives illustrate the key challenges and practical considerations required for effective strain selection and successful product implementation (Created in BioRender. Diaz Santos, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/04ldavn).

Host Specificity and Symbiotic Compatibility: Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing systems are often highly specific. Classical rhizobia form nodules only on compatible legume hosts, with many bacteria and legumes restricted to one another in near one-to-one partnerships [92]. This specificity means an inoculant strain highly effective on one crop may be useless on another. Even with the right pairing, competitive interactions in soil can interfere indigenous rhizobia, if present, often outcompete introduced strains for nodule occupancy, sometimes leading to suboptimal symbiosis despite inoculation. For non-legume crops, the challenge is greater, most cannot form nodules at all, and must rely on looser associations with endophytic or rhizosphere bacteria. Achieving tight integration of N-fixers with non-legume roots remains an unresolved biological hurdle.

Colonization Efficiency and Competition: Associative diazotrophs like Azospirillum and Herbaspirillum can colonize cereals and grasses, but establishing a robust population in the field is inconsistent. These bacteria often provide only a modest fraction of the plant’s N needs under real-world conditions. One reason is competition from the native microbiome: the soil and root habitat is crowded with microbes adapted to local conditions. An introduced inoculant may struggle to compete for root attachment sites and nutrients. Crop genotype and exudates also influence colonization; certain cultivars simply recruit inoculants better than others. Moreover, environmental stresses limit colonization. Cyanobacterial biofertilizers (e.g., Nostoc or Anabaena species used in flooded rice fields) face similar issues: they must remain active against competition from other microbes and not be displaced in open-field conditions.

Nitrogenase Regulation and Environmental Inhibition: A further limitation is that nitrogenase, the enzyme complex for N2 fixation, is exquisitely sensitive to environmental factors. Oxygen inactivates nitrogenase, so even associative bacteria must find or create micro-anaerobic niches (e.g., inside root tissues or biofilms) to fix N—conditions that may not consistently occur in field soil [141]. Additionally, the presence of mineral nitrogen (ammonium or nitrate) strongly represses nitrogenase gene expression in most diazotrophs, as the microbes downregulate BNF when external N is available. In practical, these bacteria tend to benefit crops more via other plant growth-promoting mechanisms (phytohormone production, etc.) than through N provision [141]. The result is often inconsistent yield response. Finally, many symbiotic systems are sensitive to soil conditions: acidity, salinity, or temperature extremes can impair infection and nodulation. These environmental stressors frequently limit the field performance of inoculants by disrupting either the microbial partner or the plant’s receptivity.

Inoculant Formulation and Viability: Technological challenges begin with formulating microbial inoculants that remain viable and effective from factory to field. Seed-applied inoculants face additional insults: desiccation on the seed surface and exposure to seed-applied chemicals (e.g., fungicide or insecticide treatments) can kill the bacteria. Consequently, a significant bottleneck is ensuring a sufficient live dose of the inoculant reaches the soil and root at planting time.

Biosafety and Regulatory Approval: Bacterial biofertilizers inhabit a gray area between fertilizers and live biological agents, which poses regulatory complexities. In many jurisdictions, standard rhizobial inoculants are lightly regulated (treated as soil amendments), but newer products, especially those with novel strains or genetic modifications, face stricter oversight. Biosafety approval is a barrier for regulation. Native strains may require evidence that they are safe (non-pathogenic to plants, animals, and ecosystems) and not invasive. Currently, regulatory frameworks often lag behind the biofertilizer industry’s growth. This can either allow dubious products on the market or, conversely, hinder the introduction of genuinely beneficial innovations.

Quality control is a related issue: absent stringent standards, some commercial inoculants have been found to contain fewer viable bacteria or different strains than claimed. Regulatory frameworks should mandate rigorous evidence of nitrogen-fixing efficacy prior to commercialization to ensure product reliability and avoid unfounded claims [143]. They suggest criteria such as demonstrating the strain possesses nitrogenase genes and remains present in sufficient numbers throughout the crop life. Implementing such standards would raise product reliability but also increase development costs and time to market.

Farmer Awareness and Adoption: Lastly, socio-economic factors influence the uptake of microbial inoculants. Farmers are understandably cautious about replacing a portion of synthetic N fertilizer with a biological product whose effects may be less predictable. The benefits of inoculation, often a moderate yield increase or fertilizer saving under specific conditions, can be hard to see year-to-year, especially if weather or soil variability masks their impact. In contrast, the cost of failure (yield loss from N deficiency) is high. Therefore, many growers stick to conventional fertilization unless given strong evidence and guidance to adopt biofertilizers. Building farmer trust will require not only better products but also extension efforts, demonstration trials, decision-support tools, and possibly economic incentives (e.g., credits for reducing fertilizer use). In addition, the convenience of application matters: inoculants that integrate seamlessly into farming operations (such as pre-coated seeds or easily applied liquids) are more likely to be adopted. In short, overcoming the human and regulatory hurdles is as important as the biological ones for the success of BNF inoculants.

Despite the persistent challenges that limit the widespread success of bacterial inoculants, interdisciplinary research across microbiology, agronomy, biotechnology, and policy is driving important advances that could transform their role in agriculture and NUE.

One central approach involves the careful selection and genetic improvement in strains, where native isolates adapted to local soil and climate conditions are prioritized because of their competitive advantage and greater resilience, while modern biotechnology, is enabling targeted enhancement of nitrogen fixation capacity, stress tolerance, and host compatibility. Complementary to strain development, there is growing recognition that single-strain inoculants rarely perform optimally in the complex soil–plant–microbe continuum; thus, microbial consortia combining diazotrophs with other plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria or fungi are increasingly being developed to provide synergistic benefits ranging from improved nodulation and nutrient uptake to enhanced stress resilience, although these multi-component formulations also raise additional challenges for regulatory approval, product quality assurance, and ecological predictability.

At the same time, the role of regulatory frameworks and farmer engagement cannot be overstated: implementing minimum quality standards such as viable cell counts and proof of nitrogen-fixing efficacy, streamlining the approval of well-characterized and non-genetically modified strains, and enforcing measures against spurious or ineffective products will build confidence in biofertilizer markets, while farmer-oriented outreach through on-farm trials, demonstration plots, decision-making guidelines, and integration into certification or subsidy programs will be crucial for mainstream adoption. Evidence from soybean production, where rhizobial inoculation has become routine and highly profitable, shows that when economic, agronomic, and environmental incentives align, farmers readily embrace microbial technologies, and similar success could be replicated in cereals and other non-leguminous crops once consistency and reliability are improved.

Importantly, microbial inoculants need not operate in isolation; integration with non-microbial biostimulants such as humic and fulvic acids, seaweed extracts, and amino acid hydrolysates can generate additional synergies by enhancing soil structure and water retention, stimulating beneficial microbial activity, prolonging the availability of mineral nitrogen in the rhizosphere, chelating micronutrients essential for nitrogenase activity, and directly modulating plant metabolism and stress tolerance. Indeed, humic substances have been shown since the 1970s to improve the growth and nitrogen-fixation efficiency of free-living diazotrophs, while more recent studies highlight their capacity to act as fertilizer synergists by slowing nitrogen losses and improving uptake efficiency. When used together, microbial inoculants can supply nitrogen and phytohormones, while biostimulants enhance root development, microbial colonization, and nutrient assimilation, creating a multilayered system that maximizes NUE. Taken together, these developments illustrate that scaling up the impact of BNF inoculants on global agriculture requires not only scientific innovation in strain engineering, formulation, and consortia design, but also supportive policies, farmer-centered extension, and integration with complementary inputs, offering a realistic pathway toward reducing synthetic nitrogen fertilizer dependence by 20–30% in major cropping systems while safeguarding productivity, profitability, and environmental sustainability.

7. Market Landscape and Future Perspectives

The positive impact of diazotrophic microorganisms on agriculture has driven rapid growth that has opened the biofertilizer market. Over the past decade, the global biofertilizer market has expanded considerably, reflecting increasing demand for sustainable alternatives to chemical fertilizers. Numerous nitrogen-fixing microorganisms, such as Rhizobium, Azospirillum, and Azotobacter are now commercialized as biofertilizer products (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of commercial biofertilizer products designed to enhance nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). The table summarizes representative formulations, their declared microorganisms, concentration, target crops, and manufacturing companies.

Several formulations have demonstrated strong potential to improve crop growth, yield, and soil health while reducing reliance on synthetic nitrogen inputs and, most importantly, lowering farmers’ fertilizer costs In few years, the biofertilizer market has grown, and, at present, many nitrogen-fixing microorganisms are marketed as biofertilizers. Different products are available and some of them have shown great potential by improving crop growth and yield and could significantly reduce a farmer’s fertilizer bill [53].

Industry analyses estimate that the nitrogen-fixing biofertilizer segment reached approximately USD 1.03 billion in 2024, with projected annual growth rates of 12–13% through 2030, reflecting the rapid maturation of this niche within the broader biofertilizer market (GrandViewResearch (San Francisco, CA, USA), 2024; https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/biofertilizers-industry; accessed on 27 October 2025). Economically, Brazil represents a benchmark case: the partial substitution of urea by biological nitrogen fixation in soybean cultivation generated an estimated USD 15.2 billion in savings during the 2019–2020 season, underscoring the macroeconomic potential of large-scale adoption [186]. India is also emerging as a key growth market, supported by government incentives and public programs, with double-digit expansion expected over the next decade (IMARC Group (Noida, India), 2024; https://www.imarcgroup.com/india-biofertilizer-market, accessed on 27 October 2025). In the European Union, nitrogen-fixing biofertilizers represent one of the fastest-growing product categories within the biologicals sector, driven by environmental policies promoting the reduction in synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and the transition toward regenerative agricultural practices. The European market for biofertilizers was valued at approximately USD 679 million in 2024, with projections reaching USD 1.1–2.1 billion by 2030–2033, and nitrogen-fixation products accounting for the largest revenue share (Mordor Intelligence (Hyderabad, India), 2024; https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/europe-biofertilizers-market; accessed on 27 October 2025; IMARC Group (Noida, India), 2024; https://www.imarcgroup.com/europe-biofertilizer-market; accessed on 27 October 2025; Grand View Research (San Francisco, CA, USA), 2024; https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/biofertilizers-market/europ; accessed on 27 October 2025).

Current commercial formulations encompass symbiotic rhizobia, free-living diazotrophs that colonize plants endophytically or epiphytically within the rhizosphere or phyllosphere, and co-inoculants combining multiple microbial functional groups. These products appear in both solid and liquid formulations, typically maintaining viable counts above 106 CFU g−1 or mL−1 and ensuring high microbial viability. Many formulations now include bioactive compounds that enhance propagule activation and rapid plant–microbe interaction after application.

On the symbiotic side, companies such as Rizobacter (Pergamino, Buenos Aires, Argentina) continue to lead with traditional rhizobial inoculants for legumes, where Rhizobium or Bradyrhizobium species are applied at planting or as seed treatments to induce nodulation and supply biologically fixed nitrogen.

On the associative and free-living side, both microbial diversity and crop scope are significantly broader. Unlike conventional rhizobial inoculants limited to legumes, these products target cereals, oilseeds, and horticultural crops by exploiting microorganisms capable of colonizing roots, rhizosphere, or internal plant tissues without nodule formation. Among established commercial examples, Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus is employed in Envita® (Azotic Technologies, York, UK), an endophytic inoculant applied as foliar or in-furrow treatment that supplies biologically fixed nitrogen throughout the crop cycle (Azotic Technologies, 2024). Similarly, BlueN™ (also marketed as Utrisha N by Corteva Agriscience) contains Methylobacterium symbioticum SB23, a phyllosphere endophyte that converts atmospheric N2 into ammonium directly within leaf tissues, designed to replace a fraction of mineral fertilization in high-input systems (Corteva Agriscience, 2023). Nutribion® N (marketed as Vixeran® in some European regions) by Syngenta Biologicals (Basel, Switzerland) is based on Azotobacter salinestris CECT 9690, a versatile diazotroph capable of both epiphytic and rhizospheric colonization, enhancing nitrogen assimilation and stress tolerance in cereals and vegetables (Syngenta Biologicals, 2023). The most innovative frontier within this segment is represented by Pivot Bio’s PROVEN® 40, which integrates proprietary engineered diazotrophs—Kosakonia sacchari 6-5687 (Ks6-5687) and Klebsiella variicola 137-2253 (Kv137-2253)—designed to stably colonize maize roots and deliver consistent, measurable nitrogen through biological fixation. Company field data indicate that microbial N delivery via PROVEN® 40 can replace up to 40 lb N acre−1 while maintaining yields (Pivot Bio, 2024). Beyond its agronomic function, this product embodies the shift toward strain engineering, on-seed delivery, and digital traceability, illustrating the convergence of biotechnology and precision nutrient management.

Despite these encouraging outcomes, independent assessments consistently show that the performance of associative and free-living nitrogen-fixing inoculants remains highly variable across environments. Yield responses depend strongly on soil nutrient status, existing microbial communities, and climatic conditions [187]. According to the field study by Arrobas, Correia, and Rodrigues [188] conducted on lettuce, the commercial product BlueN™ (based on Methylobacterium symbioticum) showed limited or non-significant effects on nitrogen fixation and plant biomass accumulation under open-field conditions, indicating a strong dependence on environmental and management factors. Similarly, reviews of Azotobacter spp. emphasize that agronomic responses are highly context-specific and influenced by strain compatibility, soil fertility, and stress tolerance [189].

As Giller et al. [141] critically argue in Science Losing Its Way: Examples from the Realm of Microbial N2-Fixation in Cereals and Other Non-Legumes, there is no unequivocal evidence that current microbial inoculants enable non-leguminous crops to fix agriculturally meaningful quantities of atmospheric nitrogen. The authors emphasize that much of the existing literature is based on weak experimental design, non-replicated studies, or indirect proxies of nitrogen fixation, making it difficult to quantify true N contributions at field scale. Moving forward, progress in associative and free-living diazotroph technologies will depend on reconciling scientific rigor, regulatory oversight, and industrial credibility. Establishing a unified evidence framework—integrating isotopic tracing, multi-environment field trials, and nutrient-balance modeling—is essential to distinguish truly nitrogen-fixing inoculants from general plant-growth-promoting formulations. Only through transparent, science-based evaluation can the industry move beyond anecdotal claims and deliver microbial nitrogen solutions that are both agronomically relevant and scientifically defensible.

8. Summary and Conclusions