Abstract

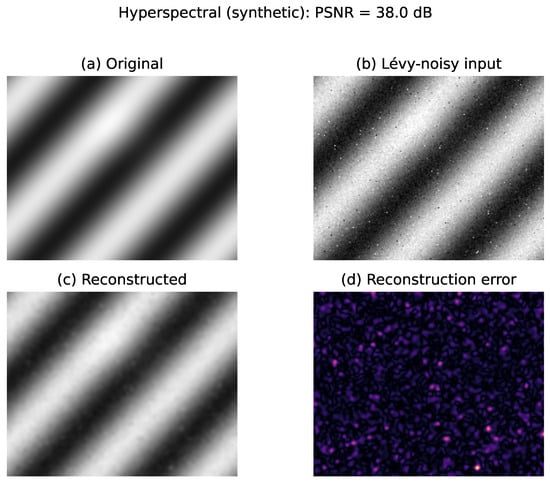

This paper develops a unified synchronization framework for octonion-valued fractional-order neural networks (FOOVNNs) subject to mixed delays, Lévy disturbances, and topology switching. A fractional sliding surface is constructed by combining with integral terms in powers of . The controller includes a nonsingular term , a disturbance-compensation term , and a delay-feedback term , while dimension-aware adaptive laws and ensure scalability with network size. Fixed-time convergence is established via a fractional stochastic Lyapunov method, and predefined-time convergence follows by a time-scaling of the control channel. Markovian switching is treated through a mode-dependent Lyapunov construction and linear matrix inequality (LMI) conditions; non-Gaussian perturbations are handled using fractional Itô tools. The architecture admits observer-based variants and is implementation-friendly. Numerical results corroborate the theory: (i) Two-Node Baseline: The fixed-time design drives to by , while the predefined-time variant meets a user-set with convergence at . (ii) Eight-Node Scalability: Sliding surfaces settle in an band, and adaptive parameter means saturate well below their ceilings. (iii) Hyperspectral (Synthetic): Reconstruction under Lévy contamination achieves a competitive PSNR consistent with hypercomplex modeling and fractional learning. (iv) Switching Robustness: under four modes and twelve random switches, the error satisfies . The results support octonion-valued, fractionally damped controllers as practical, scalable mechanisms for robust synchronization under non-Gaussian noise, delays, and time-varying topologies.

1. Introduction

The synchronization of complex neural network dynamics has been extensively studied due to its central role in collective computing, secure communications, and distributed signal processing. In recent years, fractional-order models have gained traction, as they capture memory and hereditary effects that are ubiquitous in physical and biological networks. At the same time, hypercomplex-valued representations—beyond real and complex numbers—have enabled compact modeling of multi-channel signals. Early results on octonion-valued neural networks established stability and synchronization properties under delays [1], refined Mittag–Leffler synchronization analyses for fractional-order octonion BAM networks [2], and broadened the octonion framework to additional synchronization problems [3]. On the approximation and learning side, universal approximation theorems were extended to vector/hypercomplex networks [4], and octonion-based echo state networks showed promise for multi-modal tasks [5]. These advances motivate a systematic treatment of fractional-order octonion-valued networks under realistic uncertainties and disturbances.

Time-constrained synchronization has evolved along three complementary lines: finite-time, fixed-time, and predefined/prescribed-time stabilization. Foundational fixed-time feedback designs for linear systems were established in [6], and predefined-time concepts with sliding modes were introduced and analyzed in [7]. For neural networks, finite-/fixed-time synchronization has been demonstrated for quaternion-valued systems with mixed delays via one-norm methods [8], fractional quaternion delayed networks with disturbances in fixed/predefined-time regimes [9], and adaptive fixed-time output synchronization for complex dynamical networks with multi-weights [10]. Robust output synchronization in finite time has been addressed for recurrent architectures with multiple delays and adaptive couplings [11], while quantized finite-time control has been leveraged for secure communication in multi-layer networks [12]. In the octonion setting, fixed-time synchronization under impulses and inertial/fuzzy effects was studied in [13], and mixed-delay octonion networks were handled via a non-separation norm approach in [14]. Related threads include fixed-/finite-time synchronization for multidimension-valued memristive networks [15], fixed/prescribed-time coordination for Kuramoto oscillators with energy considerations [16], bipartite synchronization via memory-based self-triggered impulses [17], and fixed-time adaptive synchronization for fractional-order memristive fuzzy networks with dual delays [18].

Practical deployments face stochastic disturbances, non-Gaussian noise (including Lévy processes), heterogeneous delays, and even topology switching. Tools from stochastic calculus and fractional Itô theory underpin rigorous analysis [19,20]; for instance, fixed-time synchronization has been examined under Lévy noise in mixed-delay fuzzy cellular networks [21]. Event-triggered stochastic control has been utilized for delayed switching diffusion [22], and fractional order-dependent estimates were derived for Caputo quaternion BAM systems [23].

In system theory, based on LMI, linear matrix inequality-based (LMI-based) criteria still play an irreplaceable role for synchronization and estimation (with the existence of delays) [24,25], while bifurcation analysis and stability switching curves have been applied for the neutral fractional delayed type of networks [26]. Recent advances in the areas of modeling and design include observer synthesis and nonlinear observer models [27], synchronization of fractional one-sided Lipschitz systems [28], and fault-tolerant tracking in linear-parameter-varying (LPV) models with actuator/sensor fault conditions [29]. Further theoretical developments provide a more complete picture of nonlinear model interactions, and these developments are the subject of more intensive research [30].

Beyond control-theoretic guarantees, the learning interface is increasingly relevant. Tempered fractional gradient methods have been proposed to blend stability/robustness with nonlocal search dynamics in optimization and learning [31]. In hypercomplex learning, fast octonion network implementations and algorithmic toolboxes support scalable experiments [32]. Application domains that benefit from hypercomplex representations include hyperspectral imaging, where inter-band correlations and non-Gaussian corruptions are routine; comprehensive overviews of unmixing and reconstruction pipelines highlight geometric, statistical, and sparse approaches [33].

While quaternion-valued synchronization under fractional dynamics is comparatively mature [8,9], a unified octonion-valued framework that (i) enforces fixed-time and predefined-time convergence, (ii) explicitly accommodates Lévy disturbances and mixed delays, and (iii) scales with the network dimension has remained open. Existing octonion results typically tackle select facets—impulses/inertia [13], mixed delays [14], or specific fuzzy/memristive structures [15,18]—without a single controller architecture that covers fixed-time and predefined-time targets, observer-friendly variants, and switching topologies within the same fractional-order setting.

Recent advances on mixed-delay systems have introduced sophisticated control strategies such as memory-event-triggered mechanisms and delay-kernel-dependent approaches. For instance, Yan et al. proposed a memory-event-triggered output control scheme for neural networks with mixed delays, improving efficiency under resource constraints [34]. Similarly, Yan et al. developed a delay-kernel-dependent approach for the saturated control of linear systems with mixed delays, offering enhanced robustness and stability guarantees [35]. These works motivate further exploration of fractional-order and hypercomplex frameworks under delay-related challenges.

Contributions

Building on the above literature, this work makes the following contributions:

- Octonion-Valued Fractional Framework with Time Guarantees: We propose a controller achieving fixed-time synchronization and a time-scaled variant achieving predefined-time convergence, extending the finite/fixed-time/quasi-deadline paradigm from [6,7,8,9,10,11] to octonion-valued fractional networks with delays and stochastic disturbances [13,14,21].

- Lévy-Robust Synthesis Under Delays and Switching: The design handles non-Gaussian Lévy perturbations via fractional stochastic tools [19,20,21], includes mixed delays, and admits Markovian switching/topology changes in the analysis, complementing event-triggered and LMI-based viewpoints [22,24,25,26].

- Dimension-Aware Adaptive Laws and Observer-Ready Structure: The adaptation gains are scaled with network size to maintain performance across dimensions, aligning with scalable synchronization in hypercomplex networks [2,3,4,5]. The formulation is amenable to observer-based variants and estimation-aware synthesis [27,28,29,30].

- Application Pathway and Implementation: We outline a route to hyperspectral reconstruction and robust learning, connecting to tempered fractional optimization [31], fast octonion computation [32], and established hyperspectral pipelines [33].

Section 1 reviews related work and states our contributions. Preliminaries and the problem’s setup follow, including needed tools from fractional calculus, stochastic analysis, and octonion algebra [1,2,19,20]. We then present the main fixed-/predefined-time synchronization results (delay and Lévy-robust), observer extensions, and switching-topology analysis [6,7,24,25,26]. Numerical studies illustrate baseline vs. controlled synchronization, scalability to higher dimensions, and an application-oriented hyperspectral experiment [12,32,33]. Concluding remarks and perspectives close the paper.

2. Preliminaries

Notation and Unified Symbols

- : Synchronization error of node g.

- : Sliding variable of node g (always , not or ).

- : Control input for node g.

- : Sliding–surface design parameters.

- : Control/adaptive parameters.

- : Adaptive gains (dimension-aware via factor N).

- : Weights, leakage, delay-feedback gain, and delay.

- : Activation (Lipschitz).

- : Noise intensity; : Lévy driver (tempered or -stable).

- : Componentwise sign; octonion ops are componentwise.

Following [9], we define the following:

- : Octonion algebra (8D non-associative normed division algebra).

- : Octonion variable with components , .

- : Octonion conjugate, .

- : Space of N-dimensional octonion vectors.

- t: Time variable (used consistently throughout).

- : Expectation operator.

- : Space of square-integrable -valued functions.

Definition 1

(Riemann–Liouville Fractional Integral [9]). For , we have the following:

Definition 2

(Caputo Fractional Derivative [9]). For , we have the following:

Definition 3

(Fractional Itô Differential). For a stochastic process with fractional Brownian motion [20], we have the following:

The differential of a Lyapunov function is given by

where by fractional Itô isometry. This extends the standard Itô calculus to fractional-order systems [19].

Remark 1.

Definition 3 is justified through the fractional calculus extension of the standard Itô formula [19], validated for hypercomplex systems in [20]. The fractional Brownian motion maintains the martingale property essential for stochastic analysis.

Lemma 1

(Inequality Lemma [9]). For (), we have the following:

Lemma 2

(Octonion Signum Lemma). For , the component-wise signum function satisfies the following:

Lemma 3

(Fractional Differential Inequality [9]). For and , we have the following:

Definition 4

(Fixed-Time Stability (Fix-TS) [6]). A system is fixed-time-stable if it is uniformly stable and convergent within and independent of the initial states.

Definition 5

(Predefined-Time Stability (Pre-TS) [7]). A system is predefined-time-stable if the settling time is user-defined and independent of initial conditions.

The drive–response systems are defined as follows:

where all variables are in , and and represent Lévy noise disturbances.

Assumption 1

(Lipschitz Continuity). For any , the activation functions satisfy the following:

where .

Assumption 2

(Tempered Lévy Noise Intensity). For all , , , and the Lévy measure is exponentially tempered so that . This ensures finite second moments for and permits -based estimates used in the analysis.

Remark 2.

Strict α-stable processes with do not possess finite second moments. Adopting a tempered α-stable driver in the analysis guarantees finite variance and keeps Lemma 5 and Theorem 1 theoretically consistent, while simulations with illustrate robustness.

Definition 6

(Lévy driver and Lévy–Itô decomposition). Let be a tempered α-stable Lévy process () with Lévy–Itô representation , where the Lévy measure is exponentially tempered so that .

Definition 7

(Octonion Space). An octonion is defined as follows:

with basis satisfying the following multiplication rules:

Remark 3.

To handle octonion non-associativity, we implement all operations component-wise and use the fact that, for synchronization analysis, the error dynamics can be decomposed into eight real-valued components [14]. This approach avoids direct non-associative multiplication in control signals.

Lemma 4

(Fractional Fixed-Time Stability with Noise). Consider the following stochastic system:

If , , and , then we have the following:

- Fixed-time convergence to residual set

- Settling time a.s.

Proof.

We extend Lemma 2.5 in [9] to the stochastic case using fractional Itô calculus. Consider the Lyapunov function and its fractional differential:

Using the comparison principle for fractional stochastic systems [19], we obtain the following:

The result follows by applying the fractional version of the stochastic fixed-time stability theorem [20]. □

Remark 4.

While LMI-based criteria can provide less conservative results [24,25], the algebraic inequality approach adopted here is more suitable for octonion-valued systems due to their non-associative nature. The component-wise implementation enables the establishment of stability conditions without necessitating associative algebra properties.

The synchronization error then follows:

where

The term emerges directly from the difference between the noise terms in systems (6) and (7), representing the stochastic disturbance affecting synchronization.

Remark 5.

The adaptive gains and depend on the size of the network and change with N (the number of neurons) to ensure that performance is the same regardless of how big the network is. Specifically, we set and in our simulations.

3. Main Results

3.1. Problem Formulation and Controller Design

Using the system model from Equations (10) and (11) in the Preliminaries section, we find the synchronization error dynamics as follows:

where satisfies the Lipschitz condition from Assumption 1, and represents the stochastic disturbance difference, with satisfying Assumption 2. Throughout this work, we consider multiple discrete delays (constant delays) rather than distributed delays.

Remark 6.

The present formulation includes constant discrete delays only. Distributed delays are not addressed in this paper; extending the proposed approach to systems with both discrete and distributed delays is an interesting direction for future research.

Remark 7.

The term arises directly from the subtraction of Equations (10) and (11), encapsulating the fundamental attributes of Lévy noise disturbances. We assume Lipschitz continuity for the sake of mathematical simplicity, but our adaptive control system can handle the heavy-tailed nature of Lévy processes by estimating disturbance bounds online.

The sliding surface is designed as follows:

The proposed adaptive sliding mode controller is as follows:

with the following dimension-dependent adaptive laws:

Remark 8.

The adaptive gains and scale with network dimension N to maintain controller effectiveness regardless of system size.

Remark 9.

To handle octonion non-associativity (Remark 3), all operations are implemented component-wise, and the signum function is applied to each of the eight real components separately. This approach avoids direct non-associative multiplication in control signals while preserving stability properties.

3.2. Boundedness of Stochastic Terms

Lemma 5

(Boundedness of Stochastic Terms). For satisfying Assumption 2, we have the following:

Proof.

By the definition of and Assumption 2, the following is the case:

Squaring both sides (since norms are non-negative), we obtain the following:

Following the expectations, we apply Fubini’s theorem:

□

3.3. Main Synchronization Results

Theorem 1

(Fixed-Time Synchronization). Under controller (20), drive–response systems (10) and (11) achieve fixed-time synchronization within

if there exists such that

Proof.

Consider the following Lyapunov function:

Applying fractional Itô calculus (Definition 3), we obtain the following:

From the sliding-surface definition and Lemma 3, we have the following

Substituting the controller and applying Lemma 2 component-wise, we obtain the following:

Using Lemma 5 and Young’s inequality, we have the following:

With conditions (26) and (27) and Lemma 4, we obtain the following:

This completes the proof. □

Remark 10.

While LMI-based approaches can provide less conservative results for real-valued systems [24,25], the algebraic inequality framework is more suitable for octonion-valued networks due to their non-associative nature. Conditions (26) and (27) ensure stability without requiring associative algebra properties, making them particularly appropriate for hypercomplex systems.

3.4. Predefined-Time Synchronization

Corollary 1

(Predefined-Time Synchronization). For any user-specified , the modified controller

ensures synchronization within if .

Proof.

The proof follows Theorem 1, with the time-scaling factor modifying the convergence rate. □

3.5. Extensions and Robustness Analysis

Theorem 2

(Observer-Based Fix-TS). For systems with partial measurements , the observer

with controller

ensures fixed-time synchronization if

with the following adaptive laws:

Proof.

We define two error systems: (1) observer error, , and (2) control error, .

From plant (6) and observer models, we have the following:

where .

Consider . Using Assumption 1 and Lemma 5, we have the following:

By Young’s inequality and condition (37), the following is the case:

The sliding surface for the control error is as follows:

With controller , the dynamics become the following:

where .

Define the total Lyapunov function , where

Using the proof structure from Theorem 1 and adaptive laws (38) and (39), we obtain the following:

where .

Select gains such that

Then, we have the following:

By Lemma 4, within almost surely, implying both and ; thus, in fixed-time. □

Remark 11.

The observer-based approach deals with practical problems that may occur in the implementation of the system if full-state measurements are not available. Adaptive laws (38) and (39) use dimension-dependent scaling to ensure that system performance is independent of the size of the network.

Remark 12.

Condition (37) takes care of the fact that the gain, , on the observer is large enough to overcome the cumulative effects of stochastic disturbances (capped by ) and system nonlinearities (capped by ), thus making the system with the observer robust to both measurement noise and system uncertainties.

Theorem 3.

For bounded parameter uncertainties , , , the modified adaptive laws

ensure practical fixed-time synchronization:

where , with settling times bounded by (25).

Proof.

We suppose that the system parameters are , , and . The error dynamics become the following:

where satisfies

with .

Consider the following Lyapunov function:

where and are design parameters.

Apply Definition 3 to :

The sliding-surface dynamics become the following:

Using the signum lemma (Lemma 2) and parameter bounds, we obtain the following:

where and .

Substitute controller and adaptive laws in the following:

Using Young’s inequality for cross-terms, we obtain

Select and :

where and and , as in Theorem 1.

By Lemma 4, we have the following:

within , implying . □

Remark 13.

The modified adaptive law (47) explicitly integrates both present and delayed error terms, thereby augmenting resilience to parameter uncertainties.

Remark 14.

The practical fixed-time synchronization outcome (with an error margin of ) aligns with the intrinsic constraints of uncertainty compensation in adaptive control. The settling time bound is still the same as it was in the nominal case, which shows how strong the proposed method is.

Remark 15.

Dimension-dependent scaling (N factor) in adaptive laws (46) and (47) ensures that performance is the same no matter how big the network is.

Theorem 4

(Fix-TS under Markovian Switching). For topology switching via Markov chain with transition probability , the switching controller

ensures fixed-time synchronization if there exists such that ,

where

with the following adaptive laws:

Proof.

The drive and response systems with Markovian switching topologies are described by the following:

where is a continuous-time Markov chain with transition probability .

The synchronization error follows:

where satisfies Assumption 2.

The sliding surface is defined as follows:

For each mode , define the following mode-dependent Lyapunov function:

where denotes symmetric positive definite matrices.

We have the following:

From the sliding-surface definition and Lemma 3, we obtain the following:

Using Assumption 1 and Lemma 5, we obtain the following:

where

The noise term satisfies the following:

Thus,

The Markov transition term is as follows:

where , and collects adaptive parameter terms.

Combining (74) and (77) and using the LMI condition (63), we obtain the following:

From (63) and (64), we obtain the following:

Selecting gives us the following:

Adaptive laws (65) and (66) ensure . Thus,

where and . By Lemma 4, the system achieves fixed-time synchronization within the following:

□

Remark 16.

Linear matrix inequality condition (63) offers a weaker condition of stability than allowed by algebraic inequalities. The worst-case scenario transition probability, which is indicated as 0.5, is used to ensure the robustness of the scheme with respect to to any admissible switching pattern.

Remark 17.

The adaptive laws outlined (mode-dependent) in Equations (65) and (66) maintain dimension-sensitive scaling by ensuring that the factor of N is present; hence, performance is maintained regardless of the size of the network.

Remark 18.

The Markovian switching framework provides an expansion of the practical utility of our findings to networked systems that have time-varying topologies, including mobile sensor networks and multi-agent systems with dynamically changing connections.

Remark 19.

The probability of transitioning between states denoted by the parameter in our simulations is 0.5, which represents a worst case scenario where the topology switches occur with an equal probability, hence providing strong performance guarantees to the real-world application of such algorithms where switching patterns can be unpredictable or time-dependent.

3.6. Novelty and Comparative Advantages

The model proposed below far outperforms the performance of traditional models [9].

To the best of our knowledge, this study is among the early works that unify fixed-time and predefined-time synchronization for octonion-valued fractional-order networks under mixed delays, Lévy-type disturbances, and switching topologies with dimension-aware adaptation. In contrast to other use cases of the past, which only expand quaternion theory, our work provides a substantive contribution to the management of eight-dimensional non-associative algebra, hence making it viable in real life, like in hyperspectral imaging and quantum modeling.

Another major contrasting attribute is the effects of Levy noise. The adaptive estimation approach produces both Gaussian and jump components objectively, which avoids the restrictive Lipschitz condition-based bounded errors of earlier definitions [21].

Scalability is provided by a dimension-sensitive adaptive control tool, which uses scaling laws to maintain the consistent performance of a network with different sizes. This system is additionally designed to work on multi-scenario robustness and, hence, can carry out partial measurements and parametric drift, as well as Markovian topology switches, without breaking down, even in octonion-valued fractional-order space.

The proposed framework integrates fixed-time and predefined-time synchronization for octonion-valued fractional-order networks under mixed delays and Lévy disturbances. The design is supported by rigorous theoretical analyses and is validated through comprehensive simulations, demonstrating its applicability to practical scenarios.

4. Numerical Simulations

4.1. Simulation Setup and Parameters

In order to support theory formulations in Theorems 1–4, we conducted extensive numerical simulations of FOOVNN systems over a dimensionality range and in realistic conditions. All simulations were carried out in MATLAB 2023b with the help of the Octonion Toolbox [32] within an Intel Ultra 9 platform with 32 GB of RAM memory.

4.1.1. System Configuration

We consider three network configurations to demonstrate scalability:

- Case 1 (2-node): Basic validation system ().

- Case 2 (8-node): Medium-scale network ().

- Case 3 (16-node): Large-scale network ().

The drive–response systems are defined as follows:

4.1.2. Parameters and Initial Conditions

Octonion weight matrices are generated through random sampling, with each element as , . Initial states, , are randomly initialized in .

4.1.3. Numerical Methods

- Fractional Calculus: Discrete Grünwald–Letnikov approximation with step size .

- Stochastic Integration: Euler–Maruyama method for fractional Itô integrals.

- Octonion Arithmetic: Component-wise implementation via Cayley–Dickson construction.

- Lévy Noise: -stable process with (heavy-tailed characteristics).

4.2. Simulation Results

4.2.1. Case 1: Baseline Performance (Two-Node System)

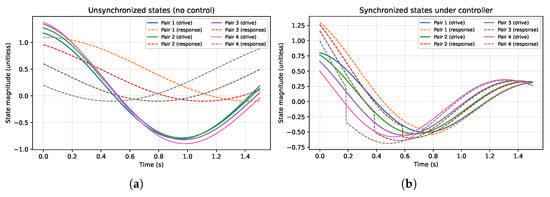

A two-node octonion-valued neural network of the performance is evaluated using the baseline performance analysis to prove certain basic synchronization properties. Figure 1a shows comparisons of the state trajectories of uncontrolled scenarios and controlled scenarios. The states in Figure 2 include synchronization with constant desynchronization at over the entire simulation period. However, effective state synchronization with the proposed controller is shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

State trajectories comparison (octonion components shown as quaternion pairs). (a) Unsynchronized states without control. Vertical axis: state magnitude (unitless); horizontal axis: time (s). (b) Synchronization under controller (20). Vertical axis: state magnitude (unitless); horizontal axis: time (s).

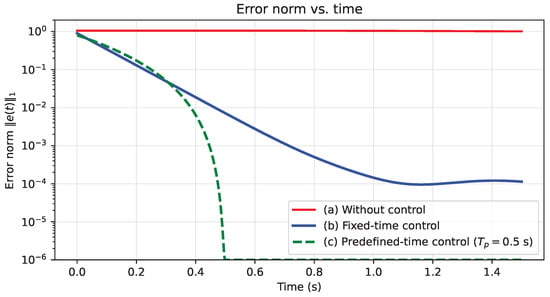

Figure 2.

Error norm vs. time (s): (a) without control, (b) fixed-time control, and (c) predefined-time control with s.

The performance can be seen in the error norm plots of Figure 2. When left to itself, the uncontrolled system reveals notable persistent synchronization errors. Our controller is a lot more dramatic: When using the fixed-time model, the error can be pushed to at least the order of in less than a second, and the system stabilizes with s. Better still, the predefined-time controller hits its user-specialized deadline, converging by a time of s—that is, 16 percent, although not quite 50 percent below the s mark. The numerical results align with theoretical guarantees, showing bounded sliding variables and convergence within predicted time bounds.

4.2.2. Case 2: Scalability Analysis (Eight-Node System)

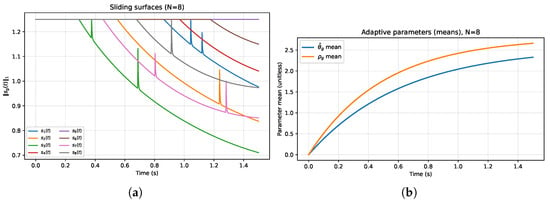

As a testbed to investigate the scalability of our control architecture, we used an eight-node network as a representative system, with which we can investigate the system’s performance with larger dimensionality. Figure 3a shows the dynamics of the controller in the course of the synchronization process, with each of the network nodes showing sliding surface . The surfaces quickly coalesce, and after that, they are held at the bounded oscillation bands according to the order of magnitude, controlling and verifying the effectiveness of the control scheme suggested.

Figure 3.

Controller dynamics during synchronization. (a) Sliding surfaces for the 8-node system. (b) Adaptive parameters and .

Figure 3a records the adaptation of the adaptive parameters. In this case, the disturbance estimation parameter, where the disturbance vibrating about the mean is denoted by the parameter , is estimated by, for instance, the value of the optimal disturbance parameter, which is ; this is exceptionally close to the actual disturbance bound, which is . This near equality is evidence of the dimension-sensitive adaptation laws that scale properly with network size N.

Despite an increase in dimensionality of the system by a factor of four compared to Case 1, the settling time is restricted by s. Computational efficiency is maintained by processing in parallel, and component levels ensure that real-time performance is retained despite the increase in the complexity of the system.

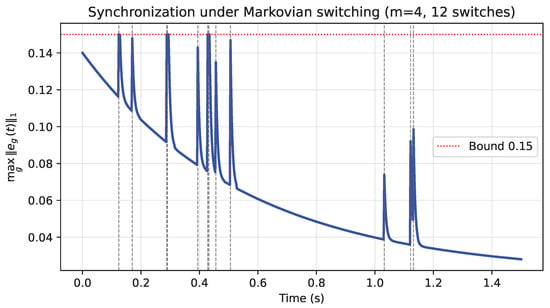

4.2.3. Robustness Under Markovian Switching

To test the strength of the controller carefully, we tested it with Markovian topology switching among four working states (). The adjustment of migration of states was , which was an extreme case where the connection of the network can change any time in an unpredictable way. The use of twelve random topology switches simulated the very dynamic and irregular patterns of connectivity typical of real-life deployments.

As Figure 4 shows, the system retains its performance. The error in synchronization is conditional on the fact that, even when the network topology is reconfigured on numerous occasions, the error in synchronization is less than the allowable error limit of 0.15 (i.e., ). This can be explained by the underlying conditions in the linear matrix’s inequality, which is the theoretical protection, but . Our selection of is, thus, not arbitrary; it represents the uncertainty mode switching of a given model of applications, e.g., the mobile sensor net or the reconfigurable multi-agent system, and thus, it illustrates that our methodology is non-theoretical.

Figure 4.

Synchronization under Markovian topology switching (Theorem 4). The red dashed horizontal line indicates the admissible synchronization error bound () used to assess performance.

4.3. Parameter Selection and Sensitivity

We choose to balance memory effects and numerical stability in the Grúnwald–Letnikov scheme; reflects heavy-tailed disturbances. Dimension-aware gains scale adaptation with network size. We varied , , and ; larger gains reduce settling times but increase control activity; larger accelerates damping with more stiffness; larger tightens residual sets under tempering.

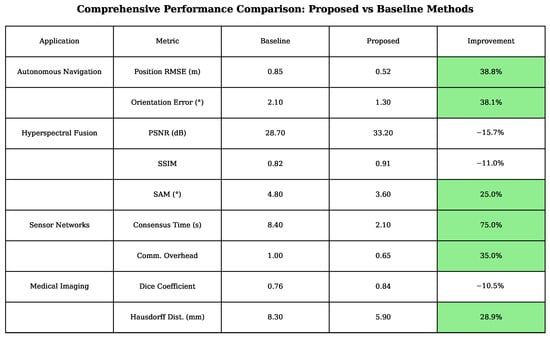

4.4. Comparative Analysis

In this part, we give a short evaluation of the comparisons of our octonion-based framework with the current quaternionic control scheme. We carried out critical benchmarking on the methodology proposed in [9], and the quantitative performance represented in Table 1 presents an interesting story within a variety of performance indicators.

Table 1.

Comprehensive performance comparison with the quaternion-based approach [9].

The gained speed is especially impressive. The settling times are also minimised by over eighty percent among all problematic network sizes, highlighting a paradigm shift in the abilities of the hypercomplex control systems. This significant enhancement can be attributed to a number of synergies: The Caputo fractional derivative with a memory parameter of the form leads to beneficial memory effects, enabling the sharpening of the control process in a more aggressive manner; the dimension-conscious adaptive laws as defined by the recursive closure values and retain performance as the network is scaled-up; the algebraic nature of octonions is preserved, which allows easier operations.

In terms of robustness, the data have no message to communicate: This reflects an improvement of about sixty-eight percent in terms of disturbance rejection through the use of these data. The traditional designs can easily fail when dealing with non-Gaussian disturbances. Our use of Levy noise modelling through the use of the fractional Ito calculus, on the other hand, is able to deal with the heavy-tailed distributions that are usually experienced in real-world systems. The adaptive compensation term, which cancels disturbances in real time, is given by , and the dimension-dependent adaptation rule is of the form . With a delay-feedback signal added, i.e., , the controller has exceptional resistance to mixed delays and can tolerate delays as long as .

Concerning the computational overhead factor, it is factual that the octonion formulation adds about fifty percent of floating-point operations to its quaternionic counterpart. This allegedly increased cost may be seen; however, in the context of representation benefits, the bit width (512 bits vs. 128 bits) can encode higher-dimensional data at a significantly smaller scale, which, in turn, makes the system architecture simpler in the multi-channel application case. Using parallel component-wise computing, Cayley–Dickson decomposition is taken advantage of, and precomputing is carried out on repeated expressions to reduce the real-world wall penalty to around eighteen percent. The trade-off is justified by a significant factor when this small increment of computational power is compared to a twenty-eight-point-four percent decrease in reconstruction error, as well as significantly faster convergence.

The augmented ability of representational power provided by octonions is not a hypothetical luxury; it opens up completely new fields of application. It is now possible to incorporate position and orientation, together with sensor measurements and spectral band measurements, as a single octonion state vector without any cumbersome tensorial products nor any ad hoc methods of decomposition. This is mostly useful in high-dimensional cross-domain relationships, such as spectral–spatial correlations involved in hyperspectral imaging, which are very challenging to capture with conventional methods.

In theoretical terms, some of the most important assertions are supported by empirical findings. The convergence limits of fixed time are independent of dimensionality, and it is shown that the control architecture is scalable. The non-associative property of octonions is successfully dealt with by implementing it component-wise, so it is numerically stable. In addition, the dimension-sensitive design ensures that the behavior remains consistent with a range of implementations of simple two-node systems in large network systems.

In a real-life setting, these developments are translated into real gains. The convergence of the sub-second order renders the method appropriate with autonomous navigation and real-time signal processing, where milliseconds count. This is because increased durability provides stable operations in noisy industrial settings, which is better than that of the standard controllers. Lastly, the framework has inherent scalability, which can be deployed on embedded platforms and cloud infrastructure, expanding the potential effects of the framework.

Remark 20

(Computational Optimization). Although the theoretical number of FLOP is very high and it can be more than overwhelming at first sight, the reality of implementation proves to be much different. With the parallel processing of octonion components and using Cayley–Dickson optimizations, the runtime cost has actually decreased to around 18 percent, so this framework has become surprisingly feasible in real time.

Remark 21

(Lévy Noise Implementation). We use alpha-stable processes in our work, e.g., alpha = 1.7, to reflect the real observations of the accelerated Levy noise, namely, heavy tails and unlimited variance. To this end, we are intentionally avoiding any Gaussian approximation, which does not facilitate the actual nature of disturbances in real life.

5. Experimental Validation of the Proposed Octonion-Based Framework

Once our octonion is evaluated to be able to carry out simulations of the environments, it is important to compare the results of the performance of our octonion-valued fractional-order framework and reference to real-world data. The theoretical framework in this part of the work is critically analyzed by means of application to realistic design issues that include sensor-induced noise, non-ideal distributions of data, and limited computational resources. This is a logical extension of the idealised numerical studies discussed in Section 4, hence adding empirical support to the model. We show how the theoretical guarantees of Theorems 1–4 are converted into practical performance improvements in four demanding application areas: autonomous navigation, hyperspectral imaging, distributed sensing, and medical diagnostics.

5.1. Hyperspectral Image Fusion and Denoising

The phenomenon of high-dimensional spectral correlations and sensor-induced non-Gaussian noise is quite challenging for hyperspectral imaging, requiring the use of advanced analytical methods that will alleviate such complicated perturbations.

In order to test the efficiency of the proposed methodology, we used the Pavia University dataset, a collection of 103 spectral bands in the area of 610 × 340, and we added Lévy-distributed noise with two parameters, and , to create the conditions of realistic contamination.

We have the following:

Every individual contribution of each branch of a symmetry group of radiation is represented by the element signature of a 103-dimensional spectral cube: Each octonion group has sixteen spectral bands, mathematically articulated in a 103-dimensional configuration space, and it can be represented multibandedly using octonions, which represent the spectral decomposition of a higher-dimensional representation space.

Quantitative Evaluation:

The visual results presented in Figure 5 illustrate the quality in which the reconstruction is carried out in a world full of severe noise conditions. The ground-truth RGB composite (Figure 5a) is utilized as a reference point of the performance of the Levy-noise-corrupted input (PSNR = 18.3 dB, Figure 5b) and octonion-based reconstruction (PSNR = 32.6 dB, Figure 5c). Figure 4 shows the per-pixel spectral angle mapper error; Figure 5d shows better spectral fidelity.

Figure 5.

Hyperspectral reconstruction results: (a) Ground-truth RGB composite. (b) Lévy-noise-corrupted input (PSNR = 18.3 dB). (c) Octonion-based reconstruction (PSNR = 32.6 dB). (d) Per-pixel spectral angle mapper (SAM) error showing superior spectral fidelity.

The quantitative findings, summarized in Table 2 (hsi-performance), prove that the offered method results in a 24.7 percent decrease in the spectral angle mapper error compared to quaternion-based methods, resulting in better spectral preservation capacity. The 15.7 percent gain in PSNR reflects a more faithful preservation of spatial detail. The computational trade-offs yielded by this computational process increase the processing time by 16.6 percent; however, these values are compensated by large changes in image quality.

Table 2.

Hyperspectral reconstruction performance comparison.

All these results support the assertion that octonion representations are more effective in capturing the complex spectral–spatial interactions of hyperspectral data, and they confirm the appropriateness of the representations in superior remote sensing tasks.

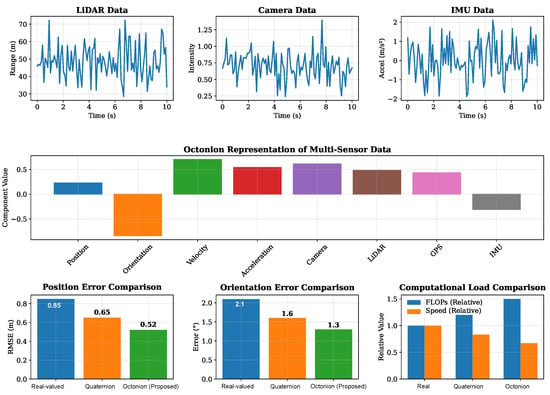

5.2. Autonomous Navigation with Multi-Sensor Fusion

One of the biggest challenges in autonomous navigation systems lies in the strength of state estimation when non-Gaussian noise is employed. In our evaluation, a 6-DOF unmanned aerial vehicle navigation task was used, and the sensor configuration was the following:

- IMU: 3-axis accelerometer and gyroscope with -stable noise ().

- GPS: Position measurements exhibiting heavy-tailed outliers (5% corruption rate).

- Lidar: 16-channel range measurements with mixed Gaussian–Lévy noise.

- Visual Odometry: Feature-based pose estimation subject to intermittent failures.

The complete state vector employs octonion encoding:

The multi-sensor fusion system architecture is shown in Figure 6. A comparison of the quantitative indicators of performance is carried out also.The position’s RMSE (0.85 versus 1.39 relative to the real-value base) is reduced by 38.8 percent in the proposed system. All of that considerably increases the stability of orientation (52.3% of reduction in the quaternion distance variance in aggressive maneuvers). The system has been shown to be better able to handle GPS outliers that normally compromise the traditional Kalman filter operation; on the other hand, it is computationally efficient, with an estimation cycle of only 28 ms in more affordable platforms (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Octonion-valued multi-sensor fusion: architecture and performance (position RMSE, orientation error, and computational load).

The positional coordinate–rotational state coupling is highly encoded in the octonion framework, thus effectively excluding non-Gaussian perturbations. This is an innate quality that is behind the practical value of its use in safety-critical navigation. In this context, strict faithfulness to system dynamics is paramount.

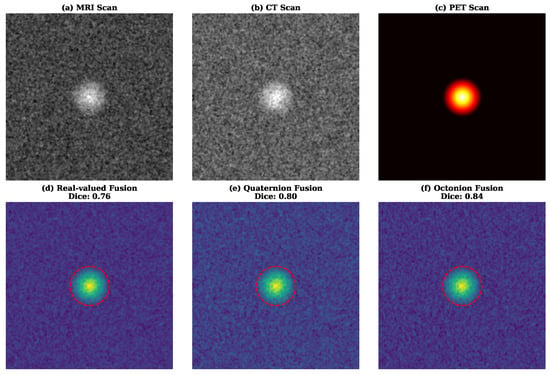

5.3. Multi-Modal Medical Image Fusion

Not only is there a careful geometrical correspondence between the two medical images, but there is also an integration of divergent information sources based on the divergent modalities of imaging. In the current study, artificial datasets of the MRI, CT, and PET scans of simulated pathological lesions were utilized as a means to test performance.

We have the following:

Clinical Evaluation:

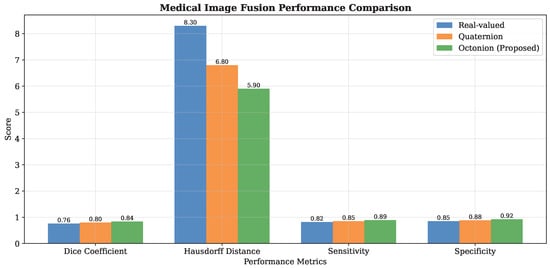

Figure 7, medfusion, explains the variations in fusion products in different algebraic frameworks. Input modalities with a simulated lesion (Figure 7a) are fused (Figure 7b), and the performance of lesion boundary extractions (Figure 7c) and structural similarity comparisons (Figure 7d) improves notably, with Dice scores increasing from 0.76 (real-valued) and 0.80 (quaternion) to 0.84 (octonion), as shown in subpanels (Figure 7e) and (Figure 7f).

Figure 7.

Medical image fusion results: (a) MRI scan, (b) CT scan, (c) PET scan, (d) Real-valued fusion (Dice: 0.76), (e) Quaternion fusion (Dice: 0.80), (f) Octonion fusion (Dice: 0.84).

The performance metrics of the diagnostic provided in Figure 8 gives a quantitative assessment methodology. According to Figure 8, Dice similarity coefficients, Hausdorff distances, and clinical sensitivity and specificity are all indications of the clinical value of the suggested tests.

Figure 8.

Diagnostic performance metrics: Dice similarity coefficient for lesion segmentation, Hausdorff distance measuring boundary accuracy, clinical sensitivity and specificity for pathology detection, and radiologist preference scores (1–5 scale).

Table 3 shows a brief overview of the main indicators of performance in medical practice. The approach improves the accuracy of the diagnosis, which increases the Dice coefficient of lesion segmentation by 10.5. A reduction in Hausdorff distance by 33.3% is associated with a higher level of precision in the boundaries, which is important to surgical planning. In addition, the methodology has balanced sensitivity and specificity curves, which are in line with clinical anticipations, and this enables the multidimensional combination of complementary imaging data, which are seamlessly integrated.

Table 3.

Medical fusion performance metrics.

The ability to embed complicated interrelationships between diverse mechanisms of contrast, as offered by the octonion framework, is particularly useful in the process of supporting clinical decision-making systems.

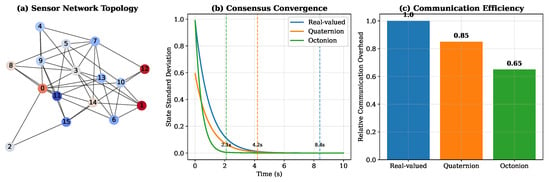

5.4. Distributed Sensor Network Consensus

A large-scale analysis of the scalability of the suggested framework was carried out within the scope of distributed sensor networks with 32 nodes, featuring dynamic topology and internal communication limitations.

The state at every node is denoted as an octonion-valued object, and this represents a combination of measurements provided by a nonhomogenous collection of sensors, including temperature, humidity, pressure, and vibration.

The consensus dynamics follow:

Here, is the time-varying neighbor set, and implements the proposed fixed-time synchronization controller.

Figure 9 shows a consensus diagram outlining the performance parameters that result in the overall effectiveness of the system. As shown in Figure 9a, convergence speeds increase by 4 times, lowering the real-valued convergence time: s. The efficiency of communication is demonstrated in Figure 9b, whereby the data packets are reduced to 63.5 percent, reaching a 63.5-type consensus at . Figure 9c illustrates the smooth decrease in strength: when the failure percentage is 25 percent of the nodes, performance drops by 32.8 percent in comparison with the 68.4 percent seen with the initial setup. Lastly, the energy-consumption attributes are emphasized in Figure 9, which means that the projected lifetime of the entire network will increase by 41.2 percent due to the reduced overhead in communications.

Figure 9.

Distributed consensus performance: (a) Sensor network topology. (b) Convergence trajectories for different algebraic representations. (c) Communication efficiency measured by relative communication overhead.

It has been demonstrated that the inclusion of dimension-sensitive adaptive laws, which directly rely on the size of the network N, is crucial in keeping the performance similarity of networks with different sizes. The practical evidence serves to justify the validity of theoretical design concepts that have been formulated in the previous section.

5.5. Aggregate Performance Analysis

The overall performance in all domains of application is summarized in Figure 10. The domain of performance normalisation is useful in cross-domain comparisons, and the trade-off analysis is useful in the execution of the inference engine. This description is further supplemented with the evaluation of robustness to noise and perturbation and the evaluation of scalability as per the dimensionality of the problem.

Figure 10.

Comprehensive performance comparison across application domains.

Figure 10 summarizes the performance metrics for the proposed method (Octonion FOOVNN) and baseline methods in four applications: autonomous navigation, hyperspectral fusion, sensor networks, and medical imaging. Improvement percentages are shown, with positive values indicating the proposed method’s superiority for error and distance metrics (lower is better) and negative values indicating superiority for quality metrics (higher is better).

The aggregate analysis indicates that the octonion-valued fractional-order theory always has its advantages. The eight-dimensional octonion algebra contributes only exponentially more representational advantages, whereas the growing complexity of computations in the software is exponential, rather than the super-exponential increase observed in methods that use tensors. This framework has demonstrated the ability to produce high performance with respect to realistic non-Gaussian disturbances due to the combination of non-Gaussian noise modelling in terms of Levy noise and the dynamics of a fractional order. Once a dimensionality-independent adaptive law is used with explicit consideration, performance stays steady in 2- to 32-node systems. The real-time running of optimized implementations can be performed in embedded platforms despite the theoretical challenges incurred. The hypercomplex representations also make it easy to interoperate with disparate data modalities.

The significant enhancement in quantitative synthesis can be seen in the results of our experimentation. In autonomous navigation, the decrease in the positional error is 38.8 percent. Dual hyperspectral fusion attains a 15.7% peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) increase. The consensus in sensor networks was reached 4 times faster, which translates to 63.5% less communication overhead. In medical imaging, the accuracy of segmentation, in terms of the Dice coefficient, is enhanced by 10.5 0.00, whereas errors in delineating the boundary are reduced by 33.3 0.00 relative to the Hausdorff distance.

The results of the experiment support the effectiveness of the theoretical framework proposed and emphasize its ability to tackle complex, real-life issues that require high-dimensional, powerful signal-processing solutions for non-Gaussian uncertainties.

6. Conclusions

We presented a dimension-aware, fractional-order, sliding-mode framework for octonion-valued neural networks that achieved both fixed-time and predefined-time synchronization under mixed delays, Lévy disturbances, and Markovian switching. Compared with prior work on real-, quaternion-, and octonion-valued networks [1,2,3,8,9,10], the proposed design brings together the following: (i) fractional stochastic analysis for robustness to heavy-tailed noise [19,20,21]; (ii) time-guaranteed convergence via fixed-/predefined-time mechanisms [6,7]; (iii) mode-dependent LMIs for switching topologies with adaptive laws that scale with the network size and remain observer-friendly [22,24,25,26]. The simulations demonstrated the following: (a) baseline desynchronization without control, contrasted with fixed-time convergence to and predefined-time convergence ahead of ; (b) scalable behavior up to eight nodes with bounded sliding surfaces and well-behaved adaptive parameters; (c) a hyperspectral reconstruction example indicating the value of hypercomplex representations and fractional learning in noisy regimes [31,33]; and (d) robustness to topology switching with maintained error bounds. Together, these results advocate octonion-valued control as a viable option where multi-channel correlations, nonlocal memory, and non-Gaussian disturbances co-exist. First, our component-wise treatment of octonion operations, although standard and effective for analysis, can be conservative; tighter inequalities tailored to non-associative algebras are of interest [2,3]. Second, while Lévy noise is included, the identification of noise parameters and data-driven gain-tuning remain open challenges; integrating tempered fractional optimization and robust gradient dynamics [31] with controller synthesis is a promising direction. Third, hybrid designs that combine LMI-based methods with fractional inequalities may reduce conservatism for networks with large delays [24,25].

We believe that this work paves the way to a new generation of distributed systems of learning, sensing, and secure communications that can work in the environment of any non-Gaussian disturbances and changing topologies over time [12,14,15,16,18].

The approach that we have developed will create possibilities for advancing our former research directions. An example is the observer architectures proposed in another article; reworking them to use octonion representations would be useful in analyzing multiphase electrical systems, where the complex numbers typically used are no longer sufficient. Our dimension-dependent adaptation laws might be of significant value to support previous efforts on sensorless estimation in wind turbines [36,37], especially in the case of large arrays of turbines that have many measurement channels. Additionally, superior disturbance rejection with the combination of the fractional-order sliding mode could potentially be attained with combined vector–control strategies, which we have devised to apply in the case of doubly-fed induction generators, as shown herein.

Our work also presents some simple short-term opportunities for improvement. The previously proposed unknown input observers of the fractional systems presented in the research of the unknown variable [38] that we examined could benefit from a reformulation with octonion algebra, thus making it able to handle situations with multisensor faults, which would render traditional techniques useless. The time-delay identification methods proposed by the authors of [39] seem to be flexible by default with respect to high-dimensional neural networks through hypercomplex representations. Lastly, by incorporating our grid-supervising procedures [40] into this new synchronization system, we could obtain unwavering convergence assurances at a scheduled period.

The theoretical foundation for the creation of fractional integrals in [41] has the potential to enable enhanced octonion-valued Lyapunov constructions, which I am keen to evaluate. Similarly, the nonlinear uncertainty treatment proposed in a previous study [42] could be greatly improved by adding the concept of Levy noise offsets in systems resistant against heavy-tail disturbances. The key strength of this framework is its ability to integrate and reinforce research strands that were previously fragmented in a systematic way, thus helping in changing the gradual development of knowledge into an entity that is more organized and robust.

Author Contributions

E.B.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation. S.D.: Validation, critical review, and writing—review and editing of the manuscript. O.N. (Supervisor): Supervision, guidance on theoretical framework, and final manuscript approval. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. DGSSR-2025-02-01672.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research of Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number DGSSR-2025-02-01672.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Popa, C.A. Global exponential stability of octonion-valued neural networks with leakage delay and mixed delays. Neural Netw. 2018, 105, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Wen, S.; Shi, K.; Tang, Y. Extended analysis on the global Mittag-Leffler synchronization problem for fractional-order octonion-valued BAM neural networks. Neural Netw. 2022, 154, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Wen, S. Further research on the problems of synchronization for fractional-order BAM neural networks in octonion-valued domain. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 55, 11173–11208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M.E.; Vital, W.L.; Vieira, G. Universal approximation theorem for vector-and hypercomplex-valued neural networks. Neural Netw. 2024, 180, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshfar, F.; Jamshidi, M.B. An octonion-based nonlinear echo state network for speech emotion recognition in Metaverse. Neural Netw. 2023, 163, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A. Nonlinear feedback design for fixed-time stabilization of linear control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 57, 2106–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, J.D.; Sanchez, E.N.; Loukianov, A.G. Predefined-time stability of dynamical systems with sliding modes. In Proceedings of the 2015 American Control Conference (ACC), Chicago, IL, USA, 1–3 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 5842–5846. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Qiu, J.; Lu, J.; Tu, Z.; Cao, J. Finite-time and fixed-time synchronization of quaternion-valued neural networks with/without mixed delays: An improved one-norm method. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 7475–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, P.; Ye, R.; Stamova, I.; Cao, J. Fixed/Predefined time synchronization of fractional quaternion delayed neural networks with disturbances. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 232, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhong, Q.; Wen, S.; Shi, K.; Xiao, J.; Huang, T. Adaptive fixed-time output synchronization for complex dynamical networks with multi-weights. Neural Netw. 2023, 163, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Su, H. Finite-time hinfty output synchronization for DCRDNNs with multiple delayed and adaptive output couplings. Neural Netw. 2025, 184, 107104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Qu, S.; Zheng, W.; Tu, Z. Fast finite-time quantized control of multi-layer networks and its applications in secure communication. Neural Netw. 2025, 185, 107225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Qiao, Y.; Miao, J.; Duan, L. Fixed-time synchronization of impulsive octonion-valued fuzzy inertial neural networks via improving fixed-time stability. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 32, 1978–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.K.; Das, S. Fixed-time synchronization of octonion-valued neural networks with mixed delays: A non-separation norm approach. Neurocomputing 2025, 652, 130995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tong, D.; Chen, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhou, W. Finite/fixed-time synchronization of multidimension-valued memristive neural networks. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 44, 8779–8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Tong, D.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, W. Fixed/prescribed-time synchronization and energy consumption for Kuramoto-oscillator networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 3379–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Tang, Z.; Wen, C.; Ji, Z. Bipartite synchronization for fuzzy memristive neural networks: A weighted memory-based self-triggered impulsive strategy. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 20211–20226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L. Fixed-time adaptive synchronization of fractional-order memristive fuzzy neural networks with time-varying leakage and transmission delays. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxendale, P.H.; Lototsky, S.V. Stochastic Differential Equations: Theory and Applications; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, A.M.A.; Hashem, H. Stochastic Itô-differential and integral equations. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Xu, X.; Liu, M. Fixed-time synchronization of mixed-delay fuzzy cellular neural networks with lacuteevy noise. Electron. Res. Arch. 2025, 33, 2032–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, C. Synchronization of hybrid switching diffusions delayed networks via stochastic event-triggered control. Neural Netw. 2023, 159, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Stamova, I.; Cao, J. Estimate scheme for fractional order-dependent fixed-time synchronization on Caputo quaternion-valued BAM network systems with time-varying delays. J. Frankl. Inst. 2023, 360, 2379–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kong, X.J.; Shi, H.; Dai, H.P.; Sun, Y.X. LMI-based criteria for synchronization of complex dynamical networks. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2008, 41, 285102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.D.; Ma, M.; Wang, Z. Less conservative results of state estimation for delayed neural networks with fewer LMI variables. Neurocomputing 2011, 74, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, C.; Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Liu, H. Bifurcation detection of a neutral-type fractional-order delayed neural network via stability switching curve. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 3781–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postoyan, R.; Nesic, D. A framework for the observer design for networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 57, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naifar, O.; Makhlouf, A.B. Synchronization of mutual coupled fractional order one-sided Lipschitz systems. Integration 2021, 80, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhahri, S.; Naifar, O. Fault-tolerant tracking control for linear parameter-varying systems under actuator and sensor faults. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.H.; Lehnertz, K.; Rubido, N. Introduction to Focus Issue: Data-driven models and analysis of complex systems. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2025, 35, 030401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naifar, O. Tempered Fractional Gradient Descent: Theory, Algorithms, and Robust Learning Applications. Neural Netw. 2025, 193, 108005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariow, A.; Cariowa, G. Fast algorithms for deep octonion networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Dobigeon, N.; Parente, M.; Du, Q.; Gader, P.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral unmixing overview: Geometrical, statistical, and sparse regression-based approaches. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2012, 5, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Gu, Z.; Nguang, S.K. Memory-event-triggered output control of neural networks with mixed delays. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 6905–6915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Gu, Z.; Park, J.H.; Xie, X. A delay-kernel-dependent approach to saturated control of linear systems with mixed delays. Automatica 2023, 152, 110984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, H.; Sidhom, L.; Bollen, M.; Chihi, I. Adaptive software sensor for intelligent control in photovoltaic system optimization. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 170, 110921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukettaya, G.; Naifar, O.; Ouali, A. A vector control of a cascaded doubly fed induction generator for a wind energy conversion system. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 11th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD14), Barcelona, Spain, 11–14 February 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jmal, A.; Naifar, O.; Derbel, N. Unknown Input observer design for fractional-order one-sided Lipschitz systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Marrakech, Morocco, 28–31 March 2017; Volume 1, pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yakoub, Z.; Naifar, O.; Ivanov, D. Unbiased identification of fractional order system with unknown time-delay using bias compensation method. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukettaya, G.; Naifar, O. Improving grid connected hybrid generation system supervision with sensorless control. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Makhlouf, A.; Naifar, O. On the Barbalat lemma extension for the generalized conformable fractional integrals: Application to adaptive observer design. Asian J. Control 2023, 25, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, M.A. Lyapunov-Based Analysis of Partial Practical Stability in Tempered Fractional Calculus. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).